Abstract

The persistence of Listeria monocytogenes in food processing plants and other ecosystems reflects its ability to adapt to numerous stresses. In this study, we investigated 138 isolates from foods and food processing plants for resistance to the quaternary ammonium disinfectant benzalkonium chloride (BC) and to heavy metals (cadmium and arsenic). We also determined the prevalence of distinct cadmium resistance determinants (cadA1, cadA2, and cadA3) among cadmium-resistant isolates. Most BC-resistant isolates were resistant to cadmium as well. Arsenic resistance was encountered primarily in serotype 4b and was an attribute of most isolates of the serotype 4b epidemic clonal group ECIa. Prevalence of the known cadmium resistance determinants was serotype associated: cadA1 was more common in isolates of serotypes 1/2a and 1/2b than 4b, while cadA2 was more common in those of serotype 4b. A subset (15/77 [19%]) of the cadmium-resistant isolates lacked the known cadmium resistance determinants. Most of these isolates were of serotype 4b and were also resistant to arsenic, suggesting novel determinants that may confer resistance to both cadmium and arsenic in these serotype 4b strains. The findings may reflect previously unrecognized components of the ecological history of different serotypes and clonal groups of L. monocytogenes, including exposures to heavy metals and disinfectants.

INTRODUCTION

Listeriosis is a rare but severe food-borne disease caused by Listeria monocytogenes, a Gram-positive facultative intracellular bacterium ubiquitous in the environment. The illness has a fatality rate of 16% and affects primarily the elderly, pregnant women, and their fetuses as well as individuals with compromised immune systems (27, 28). Processed, ready-to-eat foods such as deli meats, soft cheeses, and produce have been implicated in major outbreaks of listeriosis. The ability of L. monocytogenes to colonize the food processing plant environment is considered to be a major contributor to contamination of such foods (2, 8, 17).

Environmental persistence of L. monocytogenes is complex and mediated by a number of mechanisms, including the ability to grow in the cold, biofilm formation, resistance to disinfectants and to Listeria-specific phage (2, 8, 16, 17). Certain major outbreaks (including the 1998–1999 hot dog outbreak and the 2001 turkey deli meat outbreak) involved strains resistant to the quaternary ammonium disinfectant benzalkonium chloride (BC) (7, 18, 26). Strains of epidemic clone II (ECII) (including those from the 1998–1999 hot dog outbreak) also exhibit temperature-dependent resistance to phage (16).

Some of the longest known environmental adaptations of L. monocytogenes include those associated with resistance to heavy metals, specifically cadmium and arsenic. Such resistance occurs with sufficient frequency to allow its use in subtyping applications (1, 23, 31). It is currently not clear whether or how such resistance may contribute to overall fitness of L. monocytogenes in the processing plant environment and in foods. However, it is worthy of note that several major outbreaks of listeriosis have involved cadmium-resistant strains (7, 9, 14, 18, 26). Furthermore, analysis of L. monocytogenes from the environment of turkey processing plants revealed that, without exception, BC-resistant isolates were also resistant to cadmium (24). Another study showed that cadmium resistance was more common among strains repeatedly isolated from foods than among those recovered sporadically (12). The prevalence of resistance to these heavy metals varies among different serotypes of L. monocytogenes (19, 23, 24).

Arsenic resistance in L. monocytogenes appears to be chromosomally encoded (23), but the specific genes have not yet been identified. Significantly more information is available about resistance to cadmium, for which three distinct cadAC energy-dependent efflux systems have been identified. These cadAC cassettes are related (68 to 71% identity at the level of the deduced polypeptide sequences), and their relative prevalence can be monitored by PCR and DNA-DNA hybridizations (25). The first to be identified and characterized, cadA1, is associated with a transposon (Tn5422) harbored on plasmids (18, 20, 21). The second, cadA2, was identified from the genome sequencing of strain H7858, implicated in the 1998–1999 hot dog outbreak, and is harbored on pLM80, a large (ca. 80-kb) plasmid. This pLM80-associated cadAC (cadA2) is part of a putative composite transposon that also harbors genes for resistance to BC (7, 18, 26). The third determinant, cadA3, is a component of an integrative conjugative element (ICE) on the chromosome of L. monocytogenes EGDe (10).

Characterization of cadmium-resistant isolates from turkey processing plants revealed the presence of cadA1 and cadA2 (alone or together), while cadA3 was not identified among any of the isolates (25). However, L. monocytogenes strains from other processing plant environments or foods have not been characterized with regard to the prevalence of these different cadmium resistance determinants.

In this study, we characterized a panel of L. monocytogenes strains from foods and food processing plants in terms of their resistance to cadmium, arsenic, and BC. We also investigated the prevalence of the three known cadmium resistance determinants among cadmium-resistant isolates from these sources.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, culture conditions, and resistance determinations.

The 138 L. monocytogenes isolates used in this study are grouped by serotype and listed in Tables 1, 2, and 3. They were isolated from a wide range of processed foods and from processing plant environments between 1986 and 2006 (Tables 1 to 3). Of the 138 isolates, 46 were serotype 1/2a (or 3a), 7 were 1/2c (or 3c), 37 were 1/2b (or 3b), and 48 were of serotype 4b. Bacteria were routinely grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) (Becton, Dickinson & Co, Sparks, MD) at 37°C. Serotype designations were determined by multiplex PCR as described previously (5). Resistance to cadmium, arsenic, and BC was assessed as described previously (23, 24). Isolates were considered resistant to cadmium and arsenic if they yielded confluent growth on Iso-Sensitest agar (ISA) (Oxoid, Hampshire, England) supplemented with 70 μg/ml cadmium chloride anhydrous (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) or 500 μg/ml sodium arsenite (Fluka, Steinheim, Germany), respectively, following incubation at 37°C for 48 h. BC resistance was assessed on Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) (Mueller-Hinton broth with 1.2% Bacto agar [Becton, Dickinson and Co.]) supplemented with 10 μg/ml of benzalkonium chloride (Acros, Morris Plains, NJ) and 2% sheep blood (BBL, Sparks, MD). The plates were incubated at 37°C for 48 h.

Table 1.

Serotype 1/2a and 1/2c L. monocytogenes strains used in this study

| Strain | Isolation date (mo-yr) | Source | Serotype | Resistancea |

cadA determinantb |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd | BC | As | cadA1 | cadA2 | cadA3 | ||||

| LW-A11 | 10-01 | Avocado | 1/2a | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A19 | 03-02 | Avocado | 1/2a | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A29 | 08-02 | Avocado | 1/2a | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A3 | 02-01 | Avocado | 1/2a | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A30 | 10-02 | Avocado | 1/2a | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A33 | 02-03 | Avocado | 1/2a | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A36 | 03-03 | Guacamole | 1/2a | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A37 | 04-03 | Guacamole | 1/2a | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A43 | 10-01 | Avocado, paste | 1/2a | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A48 | 09-01 | Frozen avocado halves | 1/2a | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A5 | 02-01 | Avocado | 1/2a | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A57 | 09-01 | Avocado, pulp | 1/2a | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A76 | NKc | NK | 1/2a | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A95 | 07-04 | Avocado, pulp | 1/2a | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A52 | 05-01 | Frozen avocado pulps | 1/2a | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A7 | 12-00 | Guacamole | 1/2a | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A8 | 11-00 | Avocado | 1/2a | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A108 | 03-06 | Environmental swab | 1/2a | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A118 | 05-05 | Halibut fillet | 1/2a | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A120 | 05-05 | Environmental swab | 1/2a | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A121 | 05-05 | Albacore tuna | 1/2a | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A122 | 05-05 | Environmental swab | 1/2a | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A123 | 05-05 | Environmental swab | 1/2a | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A132 | 08-06 | Cooked crawfish tail meat | 1/2a | □ | □ | □ | |||

| AT-01 | 01-86 | Cheese, Brie | 1/2a | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A14 | 01-02 | Environmental swab | 1/2a | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A38 | 04-03 | Frozen snow crab clusters | 1/2a | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A62 | 03-02 | Environmental swab | 1/2a | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A63 | 03-02 | Seasoned flying fish roe | 1/2a | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A66 | 07-02 | Environmental swab | 1/2a | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A67 | 09-01 | Frozen capelin roe | 1/2a | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A78 | 11-03 | Soft Mexican style cheese | 1/2a | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A81 | 08-03 | Soft Mexican style cheese | 1/2a | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A96 | 11-04 | Breaded catfish | 1/2a | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A75 | 03-03 | Cold-smoked salmon | 1/2a | ■ | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A97 | 11-04 | Avocado, puree | 1/2a | ■ | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A107 | 07-06 | Cooked king crab legs | 1/2a | ■ | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A113 | 01-06 | Smoked salmon fillet | 1/2a | ■ | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A114 | 01-06 | Smoked salmon fillet | 1/2a | ■ | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A116 | 11-05 | Smoked salmon fillet | 1/2a | ■ | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A117 | 09-05 | Sliced smoked salmon | 1/2a | ■ | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A131 | 07-06 | Soft ripened cheese | 1/2a | ■ | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A10 | 10-00 | Frozen roasted eel | 1/2a | ■ | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ |

| LW-A18 | 03-02 | Biscuit for sandwich | 1/2a | ■ | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ |

| LW-A115 | 01-06 | Frozen scallops | 1/2a | ■ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| LW-A119 | 05-05 | Cooked shrimp | 1/2a | ■ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| AT-22 | 06-05 | Flounder, stuffed | 1/2c | □ | □ | □ | |||

| FDA 87 | 05-86 | Cheese, soft | 1/2c | □ | □ | □ | |||

| FDA 88 | 05-87 | Milk, low fat, pasteurized | 1/2c | □ | □ | □ | |||

| BS-09 | NK | Cheese, soft | 1/2c | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LS-025 | NK | Cheese, soft | 1/2c | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A15 | 03-02 | Sandwich | 1/2c | ■ | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ |

| LW-A124 | 04-05 | Guacamole | 1/2c | ■ | ■ | ■ | □ | ■ | □ |

White and black boxes represent susceptibility and resistance, respectively, for cadmium (Cd), benzalkonium chloride (BC), and arsenic (As), determined as described in Materials and Methods.

White and black boxes represent negative and positive PCR results, respectively, for cadA1, cadA2, and cadA3, as described in Materials and Methods. Blank spaces represent isolates that were cadmium susceptible and not tested.

NK, not known.

Table 2.

Serotype 1/2b L. monocytogenes strains used in this study

| Strain | Isolation date (mo-yr) | Source | Serotype | Resistancea |

cadA determinantb |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd | BC | As | cadA1 | cadA2 | cadA3 | ||||

| LW-A2 | 11-00 | Avocado | 1/2b | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A39 | 06-03 | Baby clam meat | 1/2b | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A44 | 04-01 | Frozen avocado pulps | 1/2b | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A51 | 05-01 | Frozen avocado pulps | 1/2b | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A55 | 06-01 | Environmental swab | 1/2b | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A56 | 02-01 | Avocado, chunky | 1/2b | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A59 | 02-01 | Avocado, chunky | 1/2b | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A9 | 12-00 | Avocado, pulp | 1/2b | □ | □ | □ | |||

| BA-11 | NKc | Ice cream, bar | 1/2b | □ | □ | □ | |||

| BS-018 | NK | Lobster meat | 1/2b | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A22 | 06-01 | Sliced turkey | 1/2b | □ | ■ | □ | |||

| BA-36 | 01-87 | Crabmeat | 1/2b | ■ | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ |

| LW-A12 | 10-01 | Frozen prepared eel | 1/2b | ■ | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ |

| LW-A50 | 06-01 | Sandwich | 1/2b | ■ | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ |

| LW-A53 | 06-01 | Sliced cheddar cheese | 1/2b | ■ | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ |

| LW-A54 | 06-01 | Sliced provolone cheese | 1/2b | ■ | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ |

| LW-A60 | 06-01 | Sandwich | 1/2b | ■ | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ |

| FDA 101 | 12-86 | Ice cream plant | 1/2b | ■ | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ |

| AT-05 | 06-05 | Milk raw | 1/2b | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| AT-06 | 06-05 | Environment | 1/2b | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| AT-26 | 06-05 | Shrimp, cooked peeled | 1/2b | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| BA-05 | 06-05 | Environment | 1/2b | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A34 | 02-03 | Cuttlefish | 1/2b | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A42 | 07-01 | Whole milk mozzarella | 1/2b | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A49 | 07-01 | Mozzarella cheese | 1/2b | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A79 | 04-02 | Environmental swab | 1/2b | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A80 | 04-02 | Environmental swab | 1/2b | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A82 | 08-03 | Soft Mexican style cheese | 1/2b | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A83 | 03-04 | Imitation crab ball | 1/2b | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LS-085 | NK | Cheese, ricotta | 1/2b | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A68 | 12-01 | Environmental swab | 1/2b | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A127 | 03-06 | Cheese | 1/2b | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| AT-24 | 06-05 | Crabmeat | 1/2b | ■ | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A41 | 05-01 | Grilled eel | 1/2b | ■ | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A94 | 07-04 | Cheese, chile relleno | 1/2b | ■ | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A106 | 07-06 | Cold-smoked salmon | 1/2b | ■ | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A111 | 02-06 | Cuttlefish | 1/2b | ■ | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

White and black boxes represent susceptibility and resistance, respectively, for cadmium (Cd), benzalkonium chloride (BC), and arsenic (As), determined as described in Materials and Methods.

White and black boxes represent negative and positive PCR results, respectively, for cadA1, cadA2, and cadA3, as described in Materials and Methods. Blank spaces represent isolates that were cadmium susceptible and not tested.

NK, not known.

Table 3.

Serotype 4b L. monocytogenes strains used in this study

| Strain | Isolation date (mo-yr) | Source | Serotype | MLGTa | Clonal group | Resistanceb |

cadA determinantc |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd | BC | As | cadA1 | cadA2 | cadA3 | ||||||

| LW-A4 | 02-01 | Avocado | 4b | ECI | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| SK-1343 | 01-92 | Frankfurters (beef) | 4b | ECII | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| LW-A32 | 01-03 | Guacamole | 4b | ECI | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| LW-A6 | 02-01 | Avocado | 4b | ECI | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| LW-A110 | 02-06 | Frozen seafood mix | 4b | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | ECI | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A125 | 03-06 | Cheese | 4b | 1.59_4b | NDe | □ | □ | □ | |||

| LW-A130 | 03-06 | Cheese | 4b | ECIa | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| LW-A77 | NKd | NK | 4b | ECI | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| LW-A85 | 04-04 | Cheese mix | 4b | ECIa | □ | □ | ■ | ||||

| LW-A87 | 04-04 | Environmental swab | 4b | ECIa | □ | □ | ■ | ||||

| LW-A88 | 04-04 | Environmental swab | 4b | ECIa | □ | □ | ■ | ||||

| LW-A89 | 04-04 | Sliced turkey | 4b | ECIa | □ | □ | ■ | ||||

| LW-A90 | 04-04 | Sliced turkey | 4b | ECIa | □ | □ | ■ | ||||

| LW-A91 | 04-04 | Environmental swab | 4b | ECIa | □ | □ | ■ | ||||

| LW-A92 | 04-04 | Environmental swab | 4b | ECIa | □ | □ | ■ | ||||

| LW-A98 | 01-05 | Environmental swab | 4b | ECIa | □ | □ | ■ | ||||

| LW-A99 | 01-05 | Environmental swab | 4b | ECIa | □ | □ | ■ | ||||

| FDA 34 | 07-88 | Shrimp fresh cooked | 4b | ECI | □ | □ | ■ | ||||

| FDA 35 | 08-88 | Environmental swab | 4b | ECIa | □ | □ | ■ | ||||

| FDA 96 | 10-88 | Lobster meat, frozen | 4b | ECI | □ | □ | ■ | ||||

| FDA 10 | 02-88 | Cheese | 4b | ECIa | □ | □ | ■ | ||||

| LW-A112 | 02-06 | Seasoned cuttlefish | 4b | ECIa | □ | ■ | □ | ||||

| LW-A58 | 06-01 | Virginia ham | 4b | 1.2_4b_UK88_EC1a | ECIa | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | □ | □ |

| LW-A84 | 04-04 | Diced ham | 4b | 1.2_4b_UK88_EC1a | ECIa | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | □ | □ |

| BS-26 | NK | Environment | 4b | 1.16_4b | ND | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | □ | □ |

| FDA 100 | 12-86 | Environmental swab | 4b | 1.2_4b_UK88_EC1a | ECIa | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | □ | □ |

| FDA 11 | 02-87 | Ice cream | 4b | 1.4_4b_EC1a | ECIa | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | □ | □ |

| LW-A1 | 11-00 | Avocado | 4b | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | ECI | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | □ | □ |

| LW-A100 | 01-05 | Environmental swab | 4b | 1.2_4b_UK88_EC1a | ECIa | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | □ | □ |

| LW-A101 | 01-05 | Vegetable food plate | 4b | 1.2_4b_UK88_EC1a | ECIa | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | □ | □ |

| LW-A102 | 01-05 | Cut ham | 4b | 1.2_4b_UK88_EC1a | ECIa | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | □ | □ |

| LW-A103 | 01-05 | Environmental swab | 4b | 1.2_4b_UK88_EC1a | ECIa | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | □ | □ |

| LW-A104 | 01-05 | Environmental swab | 4b | 1.2_4b_UK88_EC1a | ECIa | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | □ | □ |

| LW-A45 | 04-01 | Frozen avocado pulps | 4b | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | ECI | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | □ | □ |

| LW-A46 | 08-01 | Smoked salmon | 4b | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | ECI | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | □ | □ |

| AT-16 | 01-88 | Fish, red snapper | 4b | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | ECI | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | ■ | □ |

| LW-A69 | 12-01 | Environmental swab | 4b | ECI | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | ■ | □ | |

| LW-A61 | 02-03 | Cooked crab | 4b | ECII | ■ | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | |

| LW-A105 | 04-04 | Environmental swab | 4b | ECII | ■ | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | |

| LW-A86 | 04-04 | Environmental swab | 4b | ECII | ■ | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | |

| FDA 5 | 08-86 | Ice cream, bar | 4b | ECI | ■ | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | |

| FDA 97 | 07-86 | Ice cream, bar | 4b | ECI | ■ | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | |

| LW-A109 | 02-06 | Seasoned octopus | 4b | ND | ■ | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | |

| FDA 93 | 07-86 | Environmental, dairy | 4b | ECI | ■ | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | |

| LW-A13 | 12-01 | Frozen raw shrimp | 4b | 1.46_4b | ND | ■ | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ |

| LW-A126 | 03-06 | Cheese | 4b | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | ECI | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A128 | 03-06 | Cheese | 4b | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | ECI | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

| LW-A129 | 03-06 | Cheese | 4b | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | ECI | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | □ |

MLGT haplotypes for selected isolates were determined as described in reference 6.

White and black boxes represent susceptibility and resistance, respectively, for cadmium (Cd), benzalkonium chloride (BC), and arsenic (As), determined as described in Materials and Methods.

White and black boxes represent negative and positive PCR results, respectively, for cadA1, cadA2, and cadA3, as described in Materials and Methods. Blank spaces represent isolates that were cadmium susceptible and not tested.

NK, not known.

ND, not determined (isolates were not ECI, ECIa, or ECII).

DNA-based characterizations.

DNA extractions and PCR-based detection of the cadmium resistance determinants (cadA1, cadA2, and cadA3) were done as described previously (25). Epidemic clonal groups for serotype 4b isolates were determined using DNA-DNA hybridizations as described previously (3). Specifically, isolates were identified as ECI based on serotype 4b status, hybridization with the ECI-specific probe 85M, and resistance of genomic DNA to digestion by Sau3AI, as described previously (32) while ECII status was determined by hybridization with probe 1, specific to LMOh7858_1168 (3). ECIa isolates were identified based on hybridization with probe LMSG, constructed using primers LMSG_01573F (5′-TACAATTGGTCGGACACGTG-3′) and LMSG_01573R (5′-AGAATCCGCTCATAAACAGC-3′) and by PCR for mcrB using primers H7858_0337F (5′-ATATCCATGCCCATCACCAC-3′) and H7858_0337R (5′-CGGGAGGAATCTCGTTATAC-3′). Hybridization with probe LMSG and absence of an amplicon with the mcrB primers were indicative of ECIa status (S. Lee and S. Kathariou, unpublished data). ECIa status was confirmed for randomly selected isolates by multilocus genotyping as described below.

PFGE and MLGT.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was conducted with AscI (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) and ApaI (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) as described previously (11). BioNumerics (Applied Maths, Austin, TX) was employed for analysis and clustering of PFGE profiles. Multilocus genotyping (MLGT) for selected serotype 4b isolates was conducted as described previously (6).

Statistical analysis.

Fisher's exact test was used to make pairwise comparisons among strains for their resistance to arsenic, cadmium, or BC. Summary statistics and P values for these comparisons were obtained using the FREQ procedure of the statistical software package SAS (version 9.1.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Serotype-associated trends in prevalence of resistance to BC, cadmium, and arsenic.

BC resistance ranged from approximately 6% in serotype 4b to 20% among isolates of serogroup 1/2 (Fig. 1). With the exception of two strains (LW-A22 and LW-A112, of serotypes 1/2b and 4b, respectively), all BC-resistant isolates were also resistant to cadmium (Tables 1 to 3). This strong association between BC resistance and resistance to cadmium was also noted in a study of isolates from the environment of turkey processing plants, where, as mentioned earlier, all BC-resistant isolates were also resistant to cadmium (24).

Fig 1.

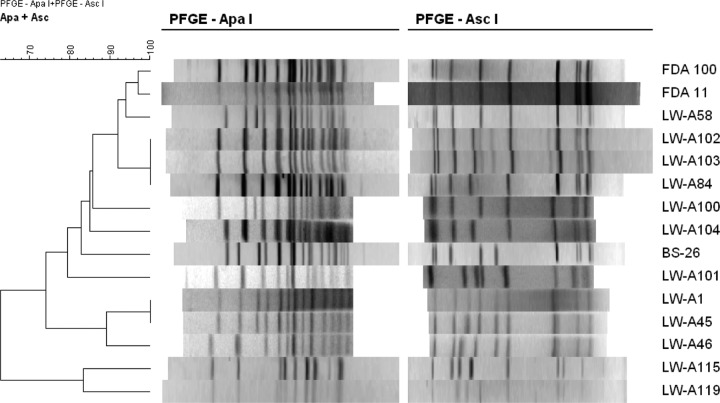

Prevalence of resistance to cadmium (Cd), arsenic (As), and benzalkonium chloride (BC) in L. monocytogenes isolates of different serotypes from food and environmental sources. Those that were resistant to both cadmium and arsenic are indicated by horizontal lines. Different letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences between serotypes (P < 0.05). The total includes seven strains of serotype 1/2c (or 3c) listed in Table 1.

Resistance to cadmium was common among isolates of all serotypes, ranging from 48% (serotype 1/2a) to approximately 70% (serotype 1/2b) (Fig. 1). In a previous study of food and clinical isolates, 77 to 80% of those of serotypes 1/2a and 1/2b were resistant to cadmium, in contrast to 34% of serotype 4b isolates (23). In the present study, the prevalence of resistance to cadmium among serotype 4b isolates was higher (54%), and it was also higher than observed earlier in our survey of serotype 4b isolates from the environment of turkey processing plants (19%) (24).

In contrast to the findings with cadmium resistance, arsenic resistance was markedly more prevalent among isolates of serotype 4b (60%) than among those of serogroup 1/2 (P < 0.0001). In fact, all but one of the arsenic-resistant isolates were of serotype 4b (with the single remaining isolate being of serotype 1/2c); resistance to arsenic was not encountered among any of the isolates of serotype 1/2a or 1/2b. Of the 28 serotype 4b isolates that were arsenic resistant, 15 (54%) were also resistant to cadmium (Fig. 1). Significantly higher prevalence of resistance to arsenic among serotype 4b than among serogroup 1/2 isolates was also noted among isolates from the turkey processing plant environment (24) as well as in an earlier study of food-derived isolates (31% of serotype 4b versus only 1.6% among those of serogroup 1/2) (23).

Serotype-associated differences in prevalence of different cadmium resistance determinants.

PCR-based analysis of the cadmium-resistant isolates in the present study (n = 78) revealed that overall cadA1 was more prevalent than cadA2 (53 versus 27%), while cadA3 was not detected in any of the isolates. A noticeable fraction (15/78 [19%]) of the cadmium-resistant isolates were negative for all three determinants (Fig. 2). No isolates harbored both cadA1 and cadA2. Our earlier study of environmental isolates also failed to identify cadmium-resistant isolates harboring cadA3. However, in that study a significant fraction (30%) of the cadmium-resistant isolates harbored both cadA1 and cadA2, while only 5% of the cadmium-resistant isolates were devoid of any of the three determinants (25). The findings may reflect differences in strain composition in the two studies. They may also reflect outcomes of different selective pressures operating in turkey processing plants in comparison to the food processing plants and foods that were the sources of the isolates in the present study.

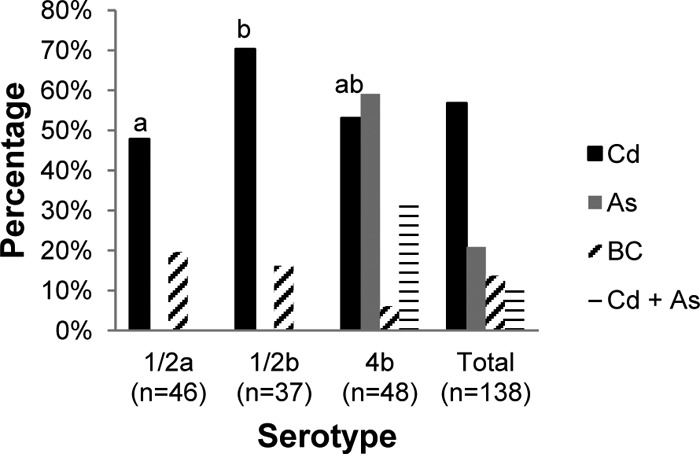

Fig 2.

Prevalence of the cadmium resistance determinants cadA1 and cadA2 in L. monocytogenes isolates of different serotypes from food and environmental sources. Isolates lacking any of the three known determinants (cadA1, cadA2, or cadA3) are indicated with black and white diagonals. Different letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences between serotypes (P < 0.05). The determinants were detected by PCR, as described in Materials and Methods. The total includes four isolates of serotype 1/2c (or 3c).

Noticeable differences were observed in the prevalence of cadA1 versus cadA2 among isolates of different serotypes. The prevalence of cadA1 was higher among isolates of serotypes 1/2a (82%) and 1/2b (73%) than those of serotype 4b (12%) (P < 0.0001). In contrast, cadA2 prevalence was markedly more common among isolates of serotypes 1/2b (27%) and 4b (38%) than those of serotype 1/2a (9%) (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2). The distribution of cadA1 differed from that observed in the earlier study of turkey processing plant environmental isolates, where cadA1 was noticeably more common among those of serotype 1/2a than among those of serotype 1/2b (25). However, in both studies cadA2 was found to be more common among isolates of serotypes 1/2b and 4b than among those of serotype 1/2a. Such findings suggest a general predilection of this determinant for serotypes 1/2b and 4b, which belong to the same major genomic division of L. monocytogenes, designated lineage I (13, 30). The underlying mechanisms remain uncharacterized but may involve differences in the ecology and microbial community associations of L. monocytogenes of different serotypes; it is possible, for instance, that lineage I strains are more likely to inhabit environments populated with bacteria (including other Listeria spp.) that may serve as donors of cadA2 (e.g., via conjugative plasmids).

Cadmium-resistant isolates with putative novel resistance determinants are primarily of serotype 4b and are also resistant to arsenic.

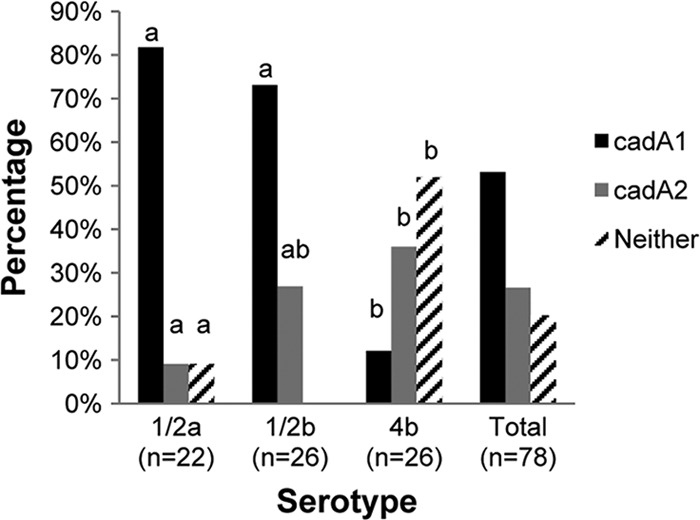

As mentioned, an estimated 19% of the cadmium-resistant isolates lacked any of the three known cadmium resistance determinants. Surprisingly, these were found to be noticeably more prevalent among isolates of serotype 4b than among those of other serotypes (P < 0.0001): of the 15 isolates in this category, 13 were of serotype 4b, while the remaining two were of serotype 1/2a (Fig. 2 and Tables 1 to 3). All 13 of these serotype 4b isolates were resistant to both cadmium and arsenic. PFGE analysis of these isolates revealed that they represented several different strain types (Fig. 3). The prevalence of such isolates was noticeably higher than that observed in the earlier study of turkey processing plant environmental isolates, where 5% of the cadmium-resistant isolates lacked any of the three known cadmium resistance determinants. However, it is noteworthy that those previously identified isolates without the known determinants were also of serotype 4b and resistant to arsenic (25).

Fig 3.

PFGE dendrogram of cadmium-resistant isolates negative for known resistance determinants. Isolates were of serotype 4b, except for LW-A115 and LWA119 (serotype 1/2a). PFGE and cluster analysis were done as described in Materials and Methods.

Relative prevalence of cadmium resistance determinants and arsenic resistance varies among different epidemic clones of serotype 4b L. monocytogenes.

Numerous outbreaks of listeriosis have involved strains of three major serotype 4b clonal groups, designated epidemic clones (ECs) such as ECI, ECII, and ECIa (also referred to as ECIV) (3, 4, 13). Analysis of the serotype 4b isolates in the present study revealed that ECI, ECII, and ECIa were all represented among the isolates, accounting for ca. 92% of the total serotype 4b population. MLGT analysis of randomly selected ECI and ECIa isolates confirmed that they belonged to these clonal groups. All tested ECI isolates had haplotype 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1, while haplotypes 1.4_4b_EC1a and 1.2_4b_UK88_EC1a were encountered among the ECIa isolates that were analyzed by MLGT (Table 3). Haplotype 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 has been found to be ECI specific, while 1.4_4b_EC1a and 1.2_4b_UK88_EC1a are specific for ECIa (6). Each of the four serotype 4b strains outside ECI, ECII, or ECIa (LW-A125, LW-A13, BS-26, and LW-A109) had unique genotypes: three strains had MLGT haplotypes 1.59_4b, 1.46_4b, and 1.16_4b, and strain LW-A109 had the PCR-based serogrouping profile IVb-v1, as previously described (22) (Table 3).

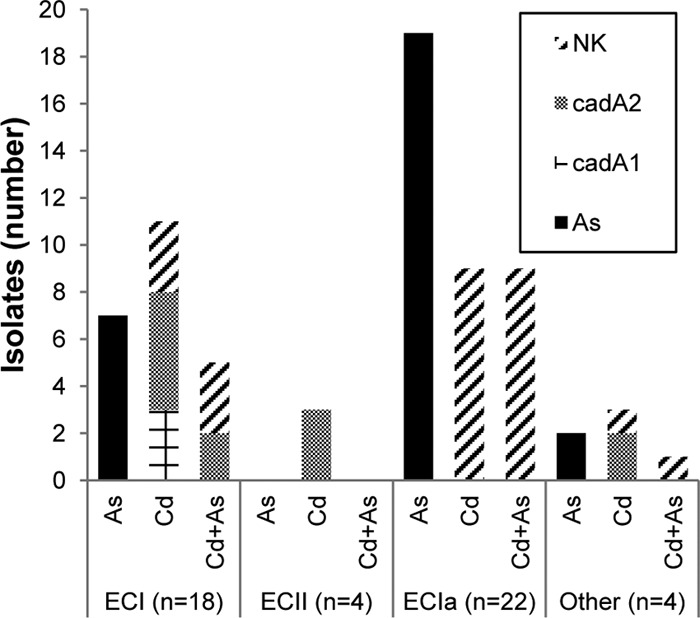

Several of the isolates belonging to ECI, ECII, and ECIa were resistant to cadmium. It was noteworthy that cadmium-resistant isolates lacking any of the three known resistance determinants were especially common in one clonal group, ECIa: none of the nine cadmium-resistant isolates of ECIa harbored cadA1, cadA2, or cadA3. As mentioned above, such isolates were also resistant to arsenic (Fig. 4).

Fig 4.

Heavy metal resistance and cadmium resistance determinants in different clonal groups of serotype 4b strains. Columns are as indicated in the inset. Epidemic clones (ECs) ECI, ECII, and ECIa, resistance, and cadA types were determined as described in Materials and Methods. “Other,” serotype 4b isolates not belonging to ECI, ECII, or ECIa; NK, not known (cadmium-resistant isolates that did not harbor cadA1, cadA2, or cadA3).

It was earlier noted that arsenic resistance was primarily encountered among serotype 4b isolates (Fig. 1). However, within serotype 4b the prevalence of resistance was disproportionally high (20/22 [91%]) among ECIa isolates, followed by ECI (7/18 [39%]) (Fig. 4). The findings suggest that ECIa isolates, followed by ECI isolates, are the primary contributors of arsenic resistance in L. monocytogenes from foods and food processing plants. Further studies are needed to determine whether arsenic resistance prevalence follows similar trends in serotype 4b strains from other sources.

One can only speculate as to the reasons for the observed tendency of arsenic resistance to be associated with these two epidemic-associated clonal groups. It is possible, for instance, that ancestral ECIa and ECI strains evolved in natural environments with high concentrations of arsenic, as hypothesized for other bacteria (15, 29). Further studies are needed to determine whether ECIa and ECI isolates may indeed be overrepresented in habitats with high levels of arsenic of natural or anthropogenic origin. The finding that most cadmium-resistant serotype 4b isolates that lacked the known cadmium resistance cassettes were also resistant to arsenic suggests that they may harbor heavy metal detoxification systems that mediate efflux of both cadmium and arsenic (and possibly other heavy metals). Genetic analysis (e.g., mutagenesis) will be needed to characterize the molecular mechanisms mediating cadmium and arsenic resistance in these strains.

The association between arsenic resistance and serotype 4b is especially intriguing, as strains of this serotype, including ECI and ECIa, contribute not only to numerous outbreaks but also to a significant fraction of sporadic human listeriosis (4, 13). The predilection of serotype 4b strains to exhibit resistance to arsenic appears to be an intrinsic feature of this serotype and is not limited to isolates from foods or the environment. Characterization of L. monocytogenes from human cases of disease in Belgium and Portugal revealed that approximately 28% of the isolates were resistant to arsenic and that in all cases these isolates were of serotype 4b (1, 31).

It is intriguing that serotype 1/2b strains rarely, if ever, exhibit resistance to arsenic in the present study and in others (1, 23, 24, 31), even though they are members of the same major genomic division (lineage I) as serotype 4b (13, 30). Further studies are needed to elucidate the evolution of arsenic and cadmium resistance in L. monocytogenes, especially in serotype 4b strains, and to assess their possible impact on other adaptations, including virulence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partially supported by a grant from the American Meat Institute Foundation and USDA grant 2006-35201-17377.

We are thankful to all members of our laboratories for their support and encouragement.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 27 July 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Almeida G, et al. 2010. Distribution and characterization of Listeria monocytogenes clinical isolates in Portugal, 1994–2007. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 29: 1219– 1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carpentier B, Cerf O. 2011. Review—persistence of Listeria monocytogenes in food industry equipment and premises. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 145: 1– 8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cheng Y, Kim JW, Lee S, Siletzky RM, Kathariou S. 2010. DNA probes for unambiguous identification of Listeria monocytogenes epidemic clone II strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76: 3061– 3068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. den Bakker HC, Fortes ED, Wiedmann M. 2010. Multilocus sequence typing of outbreak-associated Listeria monocytogenes isolates to identify epidemic clones. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 7: 257– 265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Doumith M, Buchrieser C, Glaser P, Jacquet C, Martin P. 2004. Differentiation of the major Listeria monocytogenes serovars by multiplex PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42: 3819– 3822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ducey TF, et al. 2007. A single-nucleotide-polymorphism-based multilocus genotyping assay for subtyping lineage I isolates of Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73: 133– 147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Elhanafi D, Dutta V, Kathariou S. 2010. Genetic characterization of plasmid-associated benzalkonium chloride resistance determinants in a Listeria monocytogenes strain from the 1998–1999 outbreak. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76: 8231– 8238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gandhi M, Chikindas ML. 2007. Listeria: a foodborne pathogen that knows how to survive. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 113: 1– 15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gilmour MW, et al. 2010. High-throughput genome sequencing of two Listeria monocytogenes clinical isolates during a large foodborne outbreak. BMC Genomics 11: 120 doi:10.1186/1471-2164-11-120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Glaser P, et al. 2001. Comparative genomics of Listeria species. Science 294:849– 852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Graves LM, Swaminathan B. 2001. PulseNet standardized protocol for subtyping Listeria monocytogenes by macrorestriction and pulsed-field gel elecrophoresis. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 65: 55– 62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harvey J, Gilmour A. 2001. Characterization of recurrent and sporadic Listeria monocytogenes isolates from raw milk and nondairy foods by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, monocin typing, plasmid profiling, and cadmium and antibiotic resistance determination. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67: 840– 847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kathariou S. 2002. Listeria monocytogenes virulence and pathogenicity, a food safety perspective. J. Food Prot. 65: 1811– 1829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kathariou S, et al. 2006. Involvement of closely related strains of a new clonal group of Listeria monocytogenes in the 1998–99 and 2002 multistate outbreaks of foodborne listeriosis in the United States. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 3: 292– 302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kaur S, Kamli MR, Ali A. 2011. Role of arsenic and its resistance in nature. Can. J. Microbiol. 57: 769– 774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim JW, Kathariou S. 2009. Temperature-dependent phage resistance of Listeria monocytogenes epidemic clone II. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75: 2433– 2438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kornacki JL, Gurtler JB. 2007. Incidence and control of Listeria in food processing facilities, p 681–766 In Ryser ET, Marth EH. (ed), Listeria, listeriosis and food safety, 3rd ed. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL: [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kuenne C, et al. 2010. Comparative analysis of plasmids in the genus Listeria. PLoS One 5: e12511 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lebrun M, Loulergue J, Chaslus-Dancla E, Audurier A. 1992. Plasmids in Listeria monocytogenes in relation to cadmium resistance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:3183– 3186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lebrun M, Audurier A, Cossart P. 1994. Plasmid-borne cadmium resistance genes in Listeria monocytogenes are similar to cadA and cadC of Staphylococcus aureus and are induced by cadmium. J. Bacteriol. 176: 3040– 3048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lebrun M, Audurier A, Cossart P. 1994. Plasmid-borne cadmium resistance genes in Listeria monocytogenes are present on Tn5422, a novel transposon closely related to Tn917. J. Bacteriol. 176: 3049– 3061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Leclercq A, et al. 2011. Characterization of the novel Listeria monocytogenes PCR serogrouping profile IVb-v1. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 147: 74– 77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McLauchlin J, et al. 1997. Subtyping of Listeria monocytogenes on the basis of plasmid profiles and arsenic and cadmium susceptibility. J. Appl. Microbiol. 83: 381– 388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mullapudi S, Siletzky RM, Kathariou S. 2008. Heavy-metal and benzalkonium chloride resistance of Listeria monocytogenes isolates from the environment of turkey processing plants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74: 1464– 1468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mullapudi S, Siletzky RM, Kathariou S. 2010. Diverse cadmium resistance determinants in Listeria monocytogenes isolates from the turkey processing plant environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76: 627– 630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nelson KE, et al. 2004. Whole genome comparisons of serotype 4b and 1/2a strains of the food-borne pathogen Listeria monocytogenes reveal new insights into the core genome components of this species. Nucleic Acids Res. 32: 2386– 2395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Painter J, Slutsker L. 2007. Listeriosis in humans, p 85–109 In Ryser ET, Marth EH. (ed), Listeria, listeriosis and food safety, 3rd ed. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 28. Scallan E, et al. 2011. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States—major pathogens. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 17: 7– 15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Silver S, Phung LT. 1996. Bacterial heavy metal resistance: new surprises. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 50: 753– 789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wiedmann M, et al. 1997. Ribotypes and virulence gene polymorphisms suggest three distinct Listeria monocytogenes lineages with differences in pathogenic potential. Infect. Immun. 65: 2707– 2716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yde M, Genicot A. 2004. Use of PFGE to characterize clonal relationships among Belgian clinical isolates of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Med. Microbiol. 53: 399– 402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yildirim S, et al. 2004. Epidemic clone I-specific genetic markers in strains of Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b from foods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70: 4158– 4164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]