Abstract

The present work describes the construction of a novel molecular tool for luciferase-based bioluminescence (BL) tagging of Enterococcus faecalis. To this end, a vector (pSL101) and its derivatives conferring a genetically encoded bioluminescent phenotype on all tested strains of E. faecalis were constructed. pSL101 harbors the luxABCDE operon from pPL2lux and the pREG696 broad-host-range replicon and axe-txe toxin-antitoxin cassette, providing segregational stability for long-term plasmid persistence in the absence of antibiotic selection. The bioluminescent signals obtained from three highly expressed promoters correlated linearly (R2 > 0.98) with the viable-cell count. We employed lux-tagged E. faecalis strains to monitor growth in real time in milk and urine in vitro. Furthermore, bioluminescence imaging (BLI) was used to visualize the magnitude of the bacterial burden during infection in the Galleria mellonella model system. To our knowledge, pSL101 is the first substrate addition-independent reporter system developed for BLI of E. faecalis and an efficient tool for spatiotemporal tracking of bacterial growth and quantitative determination of promoter activity in real time, noninvasively, in infection model systems.

INTRODUCTION

During the last few decades, increasing interest in Enterococcus faecalis has been prompted by the emergence of the organism among the most frequent isolates in association with hospital-related infection. Although E. faecalis is a natural inhabitant of the gastrointestinal tract in healthy humans and some strains are used as probiotics, E. faecalis has been reported to cause a variety of clinical syndromes associated with high mortality rates (26), particularly in patients with a weakened immune system or severe underlying disease (39). The role of factors associated with the virulence of E. faecalis has been described in several animal models (27, 49, 50). Although reports have shown that a significant number of putative virulence traits are widespread among E. faecalis isolates from diverse origins, gelatinase (20), cytolysin (8, 9), the enterococcal surface protein Esp (50), and aggregation substance (8) are known to be enriched among nosocomial E. faecalis strains and increase the severity of infections caused by the organism.

Traditional ex vivo methods employed to study the effect and the expression of virulence-associated genes of E. faecalis during infection have been performed by organ extraction, requiring the sacrifice of a large number of experimental animals and resulting in time-consuming sample preparation for assessing cell numbers (21, 25, 50). Moreover, none of the endpoint studies have included in vivo time course surveillance of the expression of these genes during infection. The use of noninvasive methods in intact animals to quantify the magnitude and to monitor spatiotemporal gene expression repetitively in the same infected host is recommended for efficient functional studies of potential pathogenicity traits with high reproducibility (16).

Fluorescence and bioluminescence are rapid and cost-effective optical imaging methods that offer the possibility of studying biological processes in vivo. Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-based fluorescence has been used for assessing intra- and interspecies plasmid mobilization in E. faecalis (2, 22) and to determine the roles of extracellular enterococcal proteases during biofilm development (53). On the other hand, Foucault and coworkers (14) have employed for the first time the luciferase gene lucR inserted in the integrase gene of the transposon Tn1549 to bioluminescently tag E. faecalis and to quantify the enterococcal intestinal colonization of gnotobiotic mice by light emission levels. However, a lucR-encoded firefly luciferase variant emits red light at 612 nm after exogenous addition of d-luciferin (4), thus requiring laborious sample preparation procedures.

luxABCDE-based bioluminescence imaging (BLI) technology has been successfully employed to monitor the expression of certain genes and the development of disease in real time in both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, including Escherichia coli (11, 15, 30), Listeria monocytogenes (6), Salmonella enterica (10, 35), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (44, 45), Cronobacter sakazakii (38), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (1), Staphylococcus aureus (16, 29), and Streptococcus pneumoniae (17, 34, 36). The main advantage of the luxABCDE system lies in the lack of a requirement for exogenous substrate addition. In contrast to the extended half-life of the GFP reporter, the luxABCDE-emitted signal is real time and reflects the active transcription of selected promoters fused with the bioluminescence operon. Also, bioluminescence monitoring positively contributes to the implementation of two of the three “Rs” (replacement, reduction, and refinement) of ethical principles in animal experimentation (47). Refinement and reduction are promoted by the noninvasive nature of the technology, allowing in vivo surveillance of infection progression by simply imaging the light detected from a single animal over time. Furthermore, the correlation between photon emission levels and bacterial numbers can be used as a measure to quantify the bacterial burden within an animal infection model (15).

In this report, we describe the construction of a novel vector for conferring a genetically encoded bioluminescent phenotype on different strains of E. faecalis. This plasmid-based system provides high-level bioluminescence, does not require the use of antibiotics for stable maintenance, and, although it was primarily designed for E. faecalis, is applicable to a number of other Gram-positive species. Its functionality in E. faecalis is demonstrated during growth in laboratory medium, milk, and urine and in the Galleria mellonella infection model. To our knowledge, this is the first substrate addition-independent reporter system developed for BLI of E. faecalis enabling the tracking of bacterial growth and the quantitative determination of specific gene expression over time during the development of disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. faecalis strains were routinely cultured at 37°C in M17 (Oxoid Ltd., United Kingdom) supplemented with 0.4% (vol/vol) glucose (GM17). E. coli GeneHogs was grown at 37°C in Luria Bertani (LB) medium. When required for selective growth, spectinomycin (Spc) was added at 250 μg/ml for E. coli and 500 μg/ml for E. faecalis. Erythromycin was added at a concentration of 100 μg/ml for E. coli and 15 μg/ml for E. faecalis.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain | Geographical origin | Source | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||||

| GeneHogs | Invitrogen | |||

| E. faecalis | ||||

| E1Sol | Solomon Islands | 18 | ||

| V583 | U.S. | Blood | 48 | |

| T2 | Japan | Urine | 33 | |

| EF62 | Norway | Feces | 5 | |

| MMH594 | U.S. | Blood | 24 | |

| OG1RF | U.S. | Oral | 40 | |

| Symbioflor 1 | Germany | Feces | 12 | |

| SL01 | MMH594::pSL101 | This study | ||

| SL02 | MMH594::pIL252luxPhelp | This study | ||

| SL03 | MMH594::pSL101P32 | This study | ||

| SL04 | MMH594::pSL101P16S | This study | ||

| SL05 | MMH594::pSL101Phelp | This study | ||

| SL06 | Symbioflor 1::pSL101P16S | This study | ||

| SL07 | OG1RF::pSL101P16S | This study | ||

| SL08 | EF62::pSL101P16S | This study | ||

| SL09 | T2::pSL101P16S | This study | ||

DNA techniques.

Genomic DNA was isolated from E. faecalis using ≤106 μm acid-washed glass beads (Sigma-Aldrich) and an FP120 FastPrep bead beater (Bio101/Savent) with the QiaPrep MiniPrep kit (Qiagen) as previously described (52). Plasmid DNAs were isolated from E. coli using the E.Z.N.A. Plasmid Mini Kit I (Omega Bio-tek). PCR products required for cloning were obtained with Phusion DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs, United Kingdom) using 100 ng DNA as the template. Primers were purchased from Invitrogen (Table 2). DNA fragments were purified by the use of agarose gel electrophoresis and Qiaquick PCR purification columns (Qiagen, United Kingdom). Restriction endonucleases (New England BioLabs, United Kingdom) and T4 DNA ligase (New England BioLabs, United Kingdom) were used according to the manufacturers' recommendations. DNA was sequenced using the ABI Prism BigDye Terminator Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit v3.1 (Applied Biosystems) and analyzed with the ABI Prism 3100 genetic analyzer according to the supplier's procedures.

Table 2.

Plasmid and primers used in this study

| Name | Descriptiona | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pPL2lux | Cmr; contains the lux operon with SwaI restriction site overlapping the start codon of luxA | 6 |

| pREG696 | Spcr; low-copy-number plasmid containing the axe-txe cassette derived from E. faecium | 19 |

| pIL252 | Ermr; low-copy-number plasmid | 51 |

| pMG36e | Ermr; expression vector for L. lactis | 54 |

| pPL2luxPhelp | Cmr; pPL2lux derivative containing the highly expressed Listeria promoter Phelp | 46 |

| pSL101 | Spcr; containing luxABCDE operon and axe-txe cassette | This study |

| pPL2luxP32 | Cmr; pPL2lux derivative containing the constitutive lactococcal promoter P32 | This study |

| pSL101P32 | Spcr; pPL2luxP32 derivative containing the axe-txe cassette | This study |

| pPL2luxP16S | Cmr; pPL2lux derivative containing the synthetic promoter P16S | This study |

| pSL101P16S | Spcr; pPL2luxP16S derivative containing the axe-txe cassette | This study |

| pSL101Phelp | Spcr; pPL2luxPhelp derivative containing the axe-txe cassette | This study |

| pIL252luxPhelp | Ermr; pIL252 derivative containing the luxABCDE operon driven by the Phelp promoter | This study |

| Primers | ||

| P32F | GCGCGCCTCGAGCGGTCCTCGGGATATGATAAG | This study |

| P32R | CATTTCAAAATTCCTCCGAATATTTTTTTACC | This study |

| P1F | TCGAGGTTCTTGACATTCAAATGAAAGTTTGTTAAGATATAAAGTAGAAGGAGAGTGAAACCCATG | This study |

| P1R | CATGGGTTTCACTCTCCTTCTACTTTATATCTTAACAAACTTTCATTTGAATGTCAAGAACC | This study |

Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance; Spcr, spectinomycin resistance; Ermr, erythromycin resistance.

Plasmid construction.

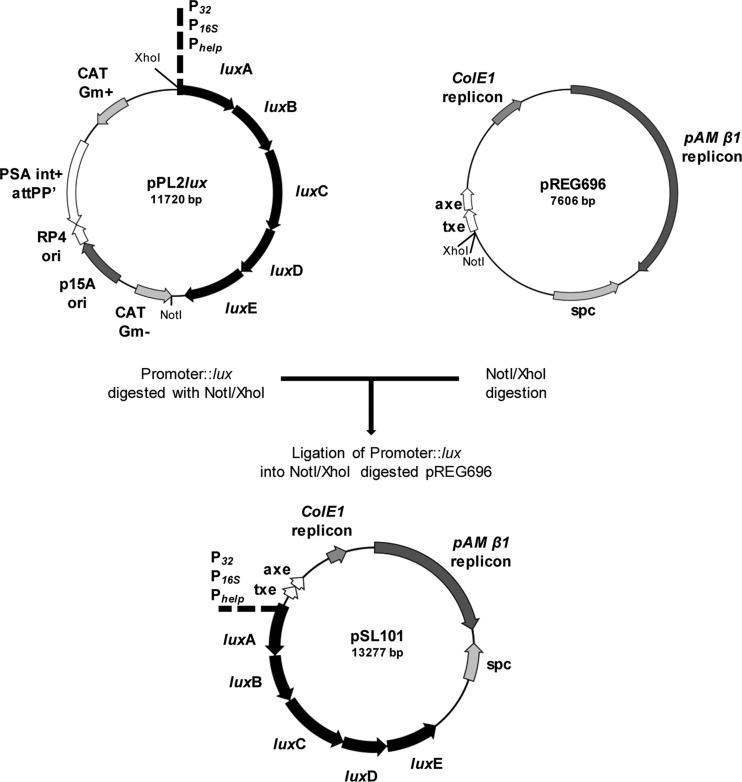

Stable bioluminescent reporter constructs were obtained by combining the vectors pPL2lux (6) and pREG696 (19) in a two-step procedure. pPL2lux contains a unique SwaI restriction site that overlaps the start codon of luxA, allowing translational fusions between enterococcal promoters to the luxABCDE operon. pSL101 was created by cutting the luxABCDE operon from pPL2lux with the restriction enzymes NotI and XhoI and cloning the resulting 5.6-kb fragment into similarly digested pREG696. For the construction of pSL101P32, the P32 promoter from pMG36e (54) was amplified by PCR using primers P32F and P32R, and the 175-bp product was digested with XhoI and SwaI before ligation into the complementary sites in pPL2lux. The construct, named pPL2luxP32, was subsequently digested with NotI and XhoI to excise the 5.8-kb luxABCDE P32 fragment prior to ligation into similarly digested plasmid pREG696 to give a 13.3-kb construct named pSL101P32. To construct the vector pSL101P16S, two short single-stranded oligonucleotides were synthesized (Table 2). A synthetic E. faecalis 16SRNA P1 promoter fused with the ribosome binding site (RBS) of the promoter Phelp and an ATG translational start codon was constructed by annealing of complementary single-stranded oligonucleotides P1F and P1R. Equal amounts of the two oligonucleotides (1 pmol) were heated to 95°C for 5 min and annealed by gradual cooling to 25°C over 2 h, yielding a 66-bp double-stranded DNA with XhoI- and SwaI-compatible cohesive ends. The synthetic 16S RNA P1 promoter was ligated into complementary sites in pPL2lux (6), giving pPL2luxP16S. The construct was subsequently digested using the XhoI and NotI cloning sites to excise the P16SluxABCDE fragment prior to ligation into similarly digested plasmid pREG696 (19). The resulting vector was named pSL101P16S. To generate pSL101Phelp, a 5.9-kb PhelpluxABCDE NotI and XhoI fragment from pPL2luxPhelp (46) containing the highly expressed constitutive Listeria promoter Phelp was cloned in pREG696.

For construction of pIL252luxPhelp, a 10-kb SnaBI and NaeI fragment from pPL2luxPhelp was inserted into the SmaI site of vector pIL252 (51). The vectors were propagated in E. coli GeneHogs, and the integrity of the inserted sequence was confirmed by DNA sequencing prior to transfer into E. faecalis strains by electroporation (23). Transformants were grown on GM17 plates supplemented with spectinomycin or erythromycin at 37°C, and the bioluminescence was checked using an IVIS 100 imaging system (Caliper Corporation, CA).

In vitro plasmid stability.

The stabilities of the different bioluminescent plasmids in E. faecalis MMH594, an isolate of clinical origin (24), were assessed in the absence of antibiotic selection by consecutive transfers of 1,000-fold dilutions to fresh GM17 broth every 24 h for 7 days. At every transfer, the dilutions were plated on selective and nonselective media and incubated at 37°C overnight. Bioluminescence was measured using an IVIS 100 imaging system (Caliper Corporation, CA). The retention of the spectinomycin- or erythromycin-resistant phenotype was expressed as a percentage.

Monitoring growth in liquid laboratory medium and luminescence quantification.

Overnight cultures of the constructed strains were diluted 1,000-fold in fresh GM17 medium and grown until they reached an optical density at 620 nm (OD620) of 0.2. The cells were diluted 100-fold in GM17, and growth and bioluminescence were monitored over time. Growth of the different strains was assessed by monitoring the absorbance at 620 nm with a Spectrostar Nano microplate reader (BMG Labtech). A total volume of 300 μl of bacterial inoculum in fresh GM17 medium was added to each well in a 96-well plate (Nunc, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Denmark). The cultures were incubated at 37°C under static conditions, and absorbance at 620 nm was measured at 15-min intervals for 7 h. For bioluminescence measurement, 300 μl of the same culture was also added to a black 96-well plate (Nunc, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Denmark) and incubated at 37°C under static conditions in the chamber of a Xenogen IVIS 100 imaging system (Calipers Corp., CA). Luminescence was measured with a binning of 16 and an exposure time of 1 min. For data analysis, regions of interest (ROI) were defined on the microtiter plates, and the intensity of the bioluminescent signal was expressed as photons per second and quantified using Living Image 3.0 software. The experiments were performed as independent triplicates.

Monitoring growth and bioluminescence in urine and milk.

Overnight cultures of E. faecalis strains were washed with sterile 20 mM phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 6.8) and diluted 1,000-fold in preheated urine at 37°C. To assess growth in milk, NAN Infant Milk Formula (Nestle) preheated to 37°C was inoculated (1% [vol/vol]) with E. faecalis and incubated at 37°C as described above. Bioluminescence was monitored over time every hour, as described above. Cell densities were measured at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h by plating dilutions on GM17 Spc, and CFU were counted after overnight incubation at 37°C. The number of CFU/ml expresses the mean of the colony count from duplicate experiments.

In vivo monitoring of E. faecalis infection in G. mellonella.

Overnight cultures of E. faecalis were centrifuged for 10 min at 7,000 × g to collect bacteria, washed twice with sterile 0.9% saline solution, and then resuspended in sterile 0.9% saline solution to an optical density at 620 nm of 1.0. Ten G. mellonella 5th-instar larvae (Urdahl Consult, Vestby, Norway) were injected with 10 μl of the E. faecalis suspension through the left hindmost proleg into the hemocoel using a Hamilton 710SNR 100-μl syringe (Hamilton Company) fitted with a 30G needle (BD Microlance 3). Infected larvae were kept in a 90-mm petri dish at 37°C. As a control, 10 larvae were injected with sterile 0.9% saline solution. For survival studies, the insects were examined every 2 h after the infection. To determine the bacterial number during infection, a cohort of 30 larvae were infected as described above. At each time point, 3 insects were surface sterilized with 70% ethanol and then dissected and transferred into individual 15-ml Eppendorf tubes containing 2 ml of 0.9% saline solution. Samples were vortexed for 3 min, and the resulting insect-bacterium homogenates were serially diluted, plated onto GM17 agar plates supplemented with spectinomycin, and incubated overnight at 37°C. Before dissection, the bioluminescence of individual insects placed in 4.0-cm petri dishes was recorded for 1 min using a Xenogen IVIS 100 imaging system.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Construction of a substrate addition-independent lux bioluminescence reporter system in E. faecalis.

This study aimed to develop a luciferase-based reporter system in E. faecalis that could be used to monitor gene expression in vitro and during infection in animal models. The luxABCDE cassette derived from Photorhabdus luminescens has previously been optimized for expression in Gram-positive bacteria by reorganization of the genes and introduction of enhanced translational signals (43). In order to assess the functionality of luxABCDE bioluminescence in E. faecalis, a series of experiments were devised. We intended to capitalize on the system developed for L. monocytogenes (6); however, the pPL2luxABCDE listerial chromosomal integration vector did not work in E. faecalis, presumably due to the absence of the required listeriophage PSA tRNAArg-attBB′ sequence. Therefore, the PhelpluxABCDE cassette was cloned in pIL252 (51). The resulting pIL252luxABCDEPhelp was transferred to E. faecalis MMH594 and conferred high-level bioluminescence, thereby confirming the functional expression of the whole lux operon and substrate-independent emission of light. However, the pIL252 vector system suffered from several drawbacks. In particular, the number of restriction enzyme sites remaining available for cloning of promoters was limited, and more importantly, the plasmid was rapidly lost in the absence of antibiotic selection (see Fig. 2a).

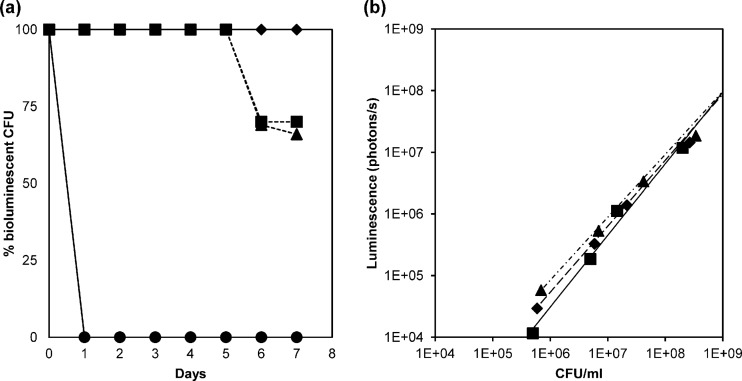

Fig 2.

(a) In vitro plasmid stability of pSL101 derivative constructs in E. faecalis. ◆, SL03 (MMH594::pSL101P32); ■, SL04 (MMH594::pSL101P16S); ▲, SL05 (MMH594::pSL101Phelp); and ●, SL02 (MMH594::pIL252luxPhelp). The strains were subcultured over 7 days without selective pressure at 37°C in GM17, and dilutions were plated on the appropriate antibiotic. The stability of the plasmid is expressed as a percentage of bioluminescent colonies on a nonselective plate compared to that on a selective plate. (b) Correlation between bioluminescence emission and viable-cell counts (CFU) in E. faecalis. ◆, SL03 (MMH594::pSL101P32) (R2 = 0.993); ■, SL04 (MMH594::pSL101P16S) (R2 = 0.995); ▲, SL05 (MMH594::pSL101Phelp) (R2 = 0.990). Samples from the mid-logarithmic phase were serially diluted, and bioluminescence was determined. The last two dilutions were plated on selective media to determine viable bacterial counts. The linear regression coefficient (R2) shows a linear relationship between luminescence emission and the number of CFU per ml. Bioluminescence values are expressed as photons per second. The values represent the averages of two biological replicates.

Enterococci frequently maintain plasmids in a stable fashion in their environments. The most stable plasmids have been shown to carry toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems (37). TA systems consist of a long-lived proteic toxin and a short-lived antitoxin that can be a protein or antisense RNA, and they act as a segregational stability module securing stable inheritance of the plasmid through the killing of cells that are plasmid free upon division. pREG696 is a derivative of pREG45 that harbors an identified proteic toxin-antitoxin cassette in the multidrug resistance plasmid pRUM of Enterococcus faecium (19). Another important feature is the fact that pREG696 contains a low-copy-number derivative of the broad-host-range pAMβ1 replicon (31). Thus, pSL101 (Fig. 1) was constructed from pREG696, in combination with the synthetic lux operon from plasmid pPL2lux. The strong promoters for high luminescence expression, P32 (54), P16S (see Materials and Methods), and Phelp (46), were cloned in front of the lux operon, and the constructs were introduced into E. faecalis MMH594. The stability of the three pSL101 derivatives under nonselective growth conditions was tested in vitro by subcultures in GM17 broth over 7 days (Fig. 2a). SL03 (MMH594::pSL101P32), SL04 (MMH594::pSL101P16S), and SL05 (MMH594::pSL101Phelp) were grown overnight, and every day, dilutions were plated on medium containing the appropriate antibiotic. The presence of the plasmid in the resulting colonies was assessed by scoring for the spectinomycin resistance phenotype and the bioluminescent signal. The pIL252luxPhelp vector carrying the pAMβ1 replicon without the axe-txe module was used for comparison. Complete segregational stability was observed for pSL101P32 with no plasmid loss for the entire duration of the experiment (7 days). Plasmid pSL101P16S was 100% stable for the first 5 days, followed by 30% loss in the last 2 days. The level of stability of pSL101Phelp was similar to that of pSL101P16S, and gradual loss of spectinomycin resistance was observed after 5 days, with 66% of the cells harboring the resistance phenotype at day 7. In contrast, plasmid pIL252luxPhelp was unstable in SL02, with >99% loss after overnight culture without erythromycin selection. These data show that the presence of the segregational stability cassette encoded by the pREG696 backbone in the pSL101 derivatives allows stable maintenance of the bioluminescent plasmid in the absence of antibiotic selection and makes this reporter system a good candidate for bioluminescence tagging of E. faecalis for long-lasting in vitro and in vivo studies. Moreover, pSL101 derivatives were stable vectors to efficiently introduce the luxABCDE cassette in a broad range of gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria, such as E. coli, Lactococcus lactis, Lactobacillus plantarum and Staphylococcus aureus (unpublished results).

Fig 1.

Strategy for the construction of vector pSL101. The promoter of interest was cloned in pPL2lux, and subsequently, the promoter::lux NotI/XhoI cassettes were subcloned in pREG696, producing pSL101 and derivatives. See Materials and Methods for details.

To assess whether light emission can be expressed as a function of cell growth, samples from the mid-logarithmic phase of SL03 (MMH594::pSL101P32), SL04 (MMH594::pSL101P16S), and SL05 (MMH594::pSL101Phelp) were serially diluted, and the bioluminescence and viable-cell counts were determined. The linear relationship found between the number of CFU and the bioluminescent signal in photons per second (Fig. 2b) (R2 > 0.99) shows that the level of bioluminescence is proportional to the number of bacterial cells, and pSL101 can therefore be employed as a quantitative reporter system to predict viable bacteria for real-time growth assessment.

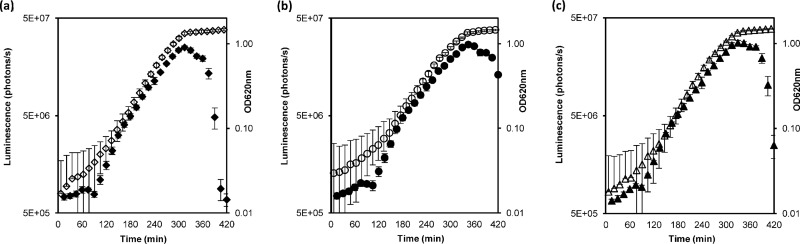

The growth and bioluminescence of E. faecalis MMH594::pSL101 derivatives were monitored over time in GM17 medium (Fig. 3). SL03 (MMH594::pSL101P32), SL04 (MMH594::pSL101P16S), and SL05 (MMH594::pSL101Phelp), grew at rates similar to that of the bioluminescence-negative control strain, SL01 (MMH594::pSL101) (data not shown). No bioluminescence was observed at any time for the negative control, confirming no background. The three constitutive promoters tested were highly expressed, and they gave rise to an increase of 2 orders of magnitude in bioluminescence during growth in GM17 broth (Fig. 3), from 6.9 × 105 ± 0.06 × 105 photons per second to 2.67 × 107 ± 0.15 ×107 photons per second. Bioluminescence increased the most from the mid-exponential phase, when bacteria are metabolically active and thus synthesizing both luciferase and its substrate (29). The highest levels of bioluminescence were detected at the end of the exponential growth phase, when it reached a peak, followed by a rapid decline during the stationary phase. The decrease of the signal is consistent with cessation of the cellular activity in the plateau phase and the concomitant reduction in the availability of the flavin mononucleotide needed by the luciferase (3).

Fig 3.

Bioluminescence during growth in GM17 at 37°C. The closed symbols indicate the bioluminescent signal in photons per second, while growth is represented by open symbols. (a) SL03 (MMH594::pSL101P32). (b) SL04 (MMH594::pSL101P16S). (c) SL05 (MMH594::pSL101Phelp). Growth was measured as the optical density at 620 nm. The values represent the averages of three independent experiments ± standard deviations (SD).

Expression of the lux operon driven by the P16S promoter in relation to growth was investigated in GM17 for four E. faecalis strains differing in their origins, namely, the clinical isolate E. faecalis MMH594 (24), the probiotic strain E. faecalis Symbioflor 1 (12), the laboratory strain E. faecalis OG1RF, and the commensal strain E. faecalis 62 (5). The specific bioluminescence activity, calculated by normalizing the photon per second emission for cell density (OD620), revealed a good correlation between luminescence and bacterial growth for the four strains (R2 > 0.94), with constant lux operon expression during the exponential phase followed by a rapid decline during the stationary phase (R2 > 0.78) (data not shown).

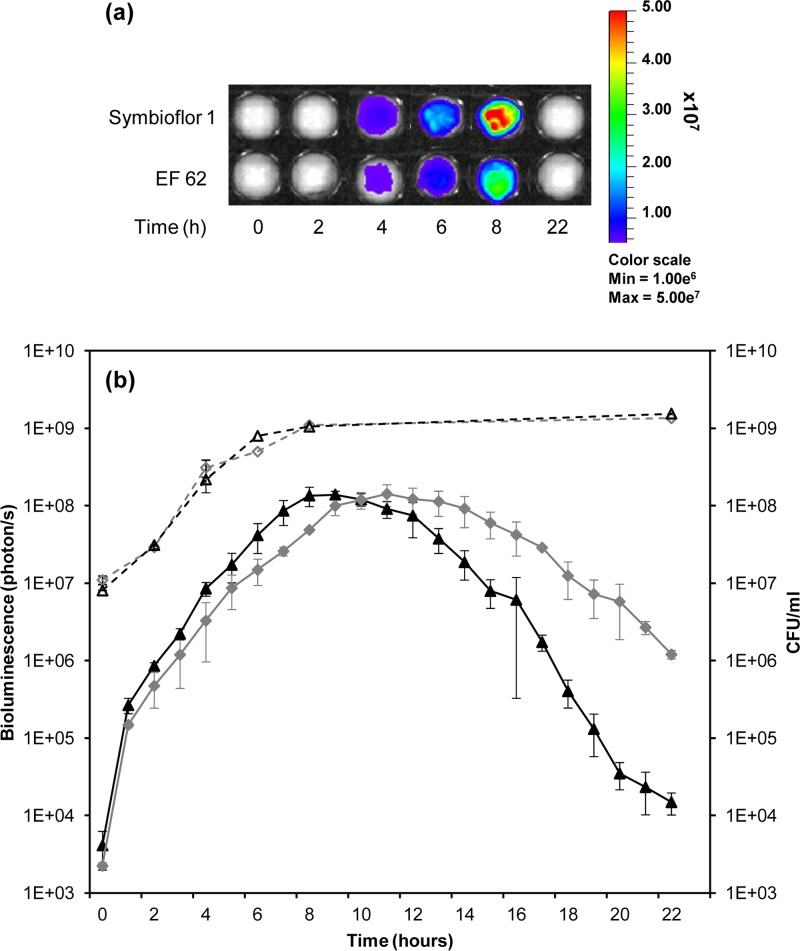

Bioluminescence signals driven by P16S were also used to follow the bacterial growth in urine and milk, two growth environments known to be associated with E. faecalis colonization. Determination of the fermentation abilities of the lux-tagged probiotic strain Symbioflor 1 (SL06) and the commensal isolate E. faecalis 62 (SL08) was followed by monitoring bioluminescence and viable bacteria in Nestle NAN Infant Milk Formula (Fig. 4). No bioluminescence was detected at any time in the wells containing milk, confirming the absence of background signals. Both strains grew well in milk, and during the exponential phase, the viable-cell counts correlated linearly with the intensity of the bioluminescence in photons per second (R2 = 0.95). Light emission achieved an increase of 5 orders of magnitude during growth.

Fig 4.

(a) In vitro bioluminescence monitoring during growth at 37°C in Nestle NAN Infant Milk Formula. The color scale indicates bioluminescence signal intensity in photons per second (minimum, 1.0e6; maximum, 5.0e7). (b) Comparison between bioluminescence emission (photons per second) and number of CFU during growth in milk. Bioluminescence is indicated by black closed triangles for SL06 (Symbioflor 1::pSL101P16S) and gray closed diamonds for SL08 (EF62::pSL101P16S). Growth is indicated by open symbols and expressed as CFU per milliliter. The values represent averages of two independent experiments ± SD.

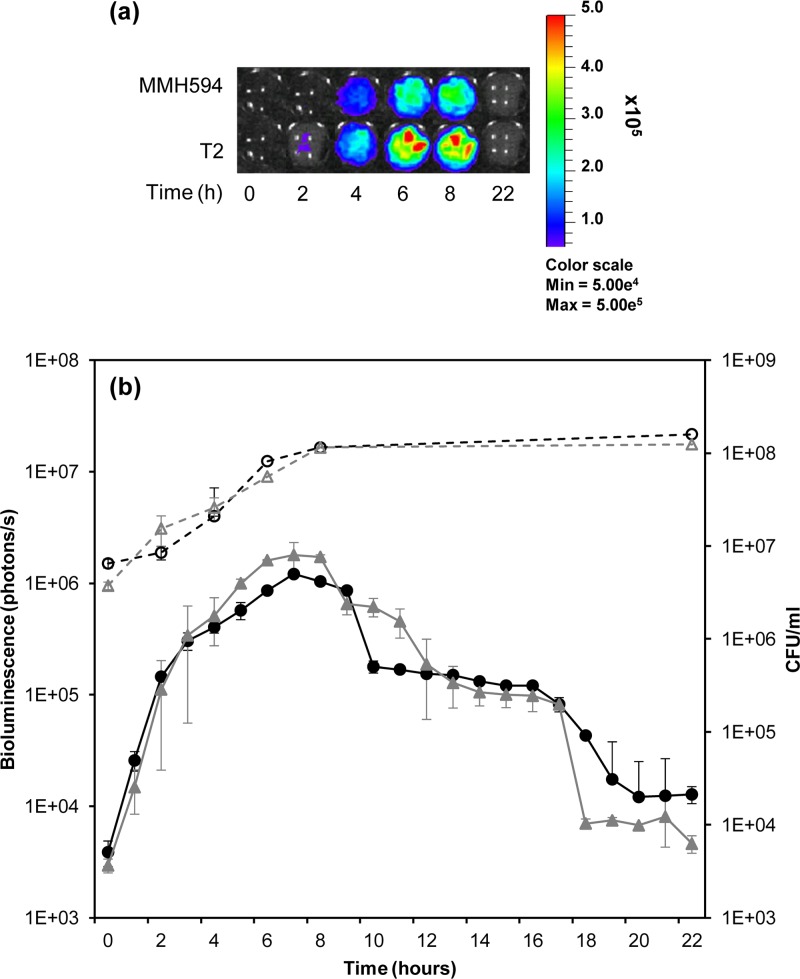

Similarly, P16S-driven bioluminescence was used to trace the growth in urine of SL04 (MMH594::pSL101P16S) and SL09 (T2::pSL101P16S), lux-tagged variants of two strains originally isolated from blood and urinary tract infections, respectively. Consistent with previous findings (7, 55), bacterial cell counts at diverse time points showed negligible differences between the strains in the viable bacterial densities, indicating similar growth rates (Fig. 5). Low levels of light emission were observed in urine, with a 5.1 × 102 ± 1.7 × 102-fold increase during growth. No statistically significant difference between the bioluminescence levels and growth rates of the two strains was found (Student t test; rejection level, P > 0.1) (Fig. 5).

Fig 5.

(a) In vitro bioluminescence monitoring during growth at 37°C in urine. The color scale indicates bioluminescence signal intensity in photons per second (minimum, 5.0e4; maximum, 5.0e5). (b) Comparison between photon emission and number of CFU during growth in urine. Bioluminescence is indicated by black closed circles for E. faecalis SL04 (MMH594::pSL101P16S) and gray closed triangles for SL09 (T2::pSL101P16S). Growth is indicated by open symbols and expressed as CFU per milliliter. Bioluminescence was measured as photons per second. The values represent averages of the data from two independent experiments ± SD.

Real-time monitoring of the growth of E. faecalis in a surrogate infection model of G. mellonella.

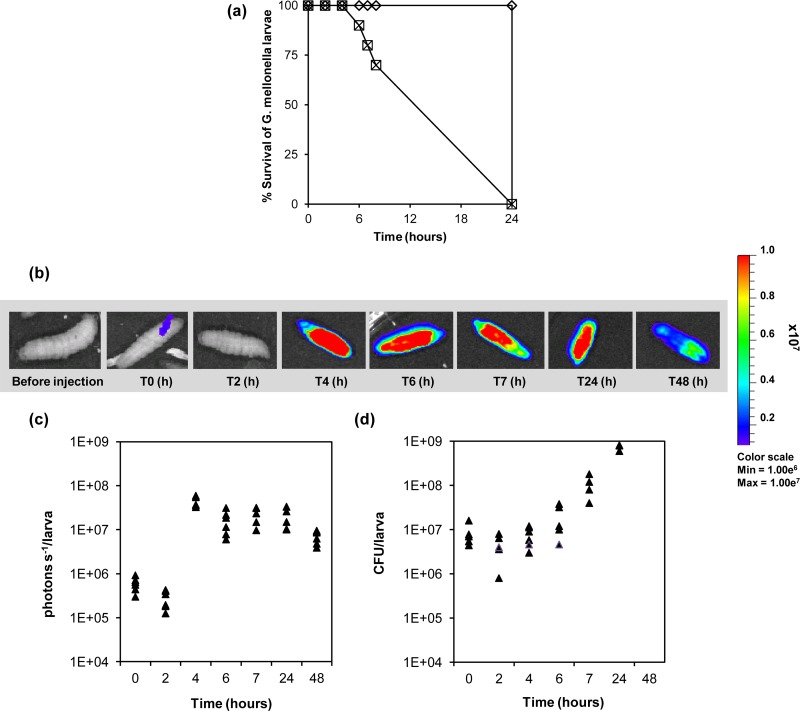

Larvae of G. mellonella are a suitable nonmammalian infection model for studying host-pathogen interaction in E. faecalis (42, 32). The caterpillar body cavity, or hemocoel, comprises a digestive tract, a primitive muscular system, a biosynthetic fat body, and a fluid functionally comparable to blood called hemolymph (41). A significant feature of these caterpillars is a relatively advanced immune system mediated by the activity of phagocytic cells within the hemolymph. Moreover, G. mellonella can be maintained at 37°C, permitting the study of pathogen virulence factors preferentially expressed at human physiological temperature. To determine whether the presence of the luxABCDE cassette affects the virulence of E. faecalis, we compared the abilities of E. faecalis MMH594 and its bioluminescence-tagged derivative SL04 (MMH594::pSL101P16S) to kill G. mellonella larvae. The larvae were infected by injection of a bacterial suspension into the hemocoel, and insect mortality was evaluated every 2 h. All the larvae were dead after 24 h. The progression of the infection was accompanied by increased insect melanization, indicating that E. faecalis triggers the host innate immune response and the activation of a prophenoloxidase cascade (28). As shown in Fig. 6a, no difference could be observed between the killing rates of wild-type and lux-tagged E. faecalis MMH594. SL04 was therefore employed to visualize the spatiotemporal bacterial growth during the progression of infection (Fig. 6b). Bioluminescence was detectable immediately after injection of SL04 into the hemocoel. In the first 2 h, a decrease in the signal was seen. Increase of light emission was observed at 4 h postinfection, when it reached a peak, followed by expression at constant levels until death of the larvae occurred. All larvae were dead 24 h postinfection, and subsequently, bioluminescence steadily declined after 48 h postinfection and finally subsided. To confirm that the bioluminescent signal reflected the growth progression of E. faecalis when infecting G. mellonella, three insects per time point were dissected, and the resulting insect-bacterium homogenates were serially diluted to determine the bacterial burden. Figure 6c shows a drop in E. faecalis cell numbers after 2 h, concomitant with the reduction in light emission (Fig. 6d), followed by rapid bacterial growth until larval death. Taken together, these results show that expression of the bioluminescent reporter was consistent with the progression of G. mellonella infection and concomitant with E. faecalis growth in the hemocoel.

Fig 6.

(a) Killing of G. mellonella larvae by E. faecalis MMH594 (□) and SL04 (MMH594::pSL101P16S) (×). The larvae were infected with approximately 4 × 106 bacteria. As a control, 10 larvae were injected with 10 μl 0.9% saline solution (♢). The data were obtained from two independent experiments. (b) Monitoring of E. faecalis SL04 colonization in G. mellonella by bioluminescence imaging of the intact insects. T, time. (c) Light emission detected over 48 h corresponding to the growth of E. faecalis SL04. (d) CFU of E. faecalis SL04 (MMH594::pSL101P16S) from homogenized G. mellonella larvae.

In conclusion, we have developed a simple and rapid method for noninvasive monitoring of the infection of E. faecalis in vivo in intact animals, with the potential to assess gene expression patterns, including virulence-related genes. The linear correlation between the intensity of the bioluminescence emission in photons per second and the number of CFU facilitates the determination of bacterial growth and alleviates the need for performing time-consuming colony counting. Therefore, this system represents a powerful tool for assessing the spatiotemporal dynamic of E. faecalis infection in living organisms, and it will contribute to improving insights into the expression of potentially new and known virulence-related traits in future studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to Finbarr Hayes (University of Manchester), who provided pREG696, and Colin Hill (University of Cork) for the gift of pPL2luxPhelp and pPL2lux. E. faecalis E1Sol and T2 were kindly provided by Kelli L. Palmer (Schepens Eye Research Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). We gratefully acknowledge Zhian Salehian for technical assistance and Mats Urdahl for valuable discussions on G. mellonella.

This work was supported by project number 191452 from the Research Council of Norway.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 27 July 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Andreu N, et al. 2010. Optimisation of bioluminescent reporters for use with mycobacteria. PLoS One 5:e10777 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arends K, Schiwon K, Sakinc T, Hubner J, Grohmann E. 2012. Green fluorescent protein-labeled monitoring tool to quantify conjugative plasmid transfer between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:895–899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bachmann H, Santos F, Kleerebezem M, van Hylckama Vlieg JE. 2007. Luciferase detection during stationary phase in Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:4704–4706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Branchini BR, et al. 2007. Thermostable red and green light-producing firefly luciferase mutants for bioluminescent reporter applications. Anal. Biochem. 361:253–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brede DA, Snipen LG, Ussery DW, Nederbragt AJ, Nes IF. 2011. Complete genome sequence of the commensal Enterococcus faecalis 62, isolated from a healthy Norwegian infant. J. Bacteriol. 193:2377–2378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bron PA, Monk IR, Corr SC, Hill C, Gahan CG. 2006. Novel luciferase reporter system for in vitro and organ-specific monitoring of differential gene expression in Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:2876–2884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carlos AR, Santos J, Semedo-Lemsaddek T, Barreto-Crespo MT, Tenreiro R. 2009. Enterococci from artisanal dairy products show high levels of adaptability. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 129:194–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chow JW, et al. 1993. Plasmid-associated hemolysin and aggregation substance production contribute to virulence in experimental enterococcal endocarditis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:2474–2477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Coburn PS, Gilmore MS. 2003. The Enterococcus faecalis cytolysin: a novel toxin active against eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells. Cell. Microbiol. 5:661–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Contag CH, et al. 1995. Photonic detection of bacterial pathogens in living hosts. Mol. Microbiol. 18:593–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Demidova TN, Gad F, Zahra T, Francis KP, Hamblin MR. 2005. Monitoring photodynamic therapy of localized infections by bioluminescence imaging of genetically engineered bacteria. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 81:15–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Domann E, et al. 2007. Comparative genomic analysis for the presence of potential enterococcal virulence factors in the probiotic Enterococcus faecalis strain Symbioflor 1. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 297:533–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Reference deleted.

- 14. Foucault ML, Depardieu F, Courvalin P, Grillot-Courvalin C. 2010. Inducible expression eliminates the fitness cost of vancomycin resistance in enterococci. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:16964–16969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Foucault ML, Thomas L, Goussard S, Branchini BR, Grillot-Courvalin C. 2010. In vivo bioluminescence imaging for the study of intestinal colonization by Escherichia coli in mice. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:264–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Francis KP, et al. 2000. Monitoring bioluminescent Staphylococcus aureus infections in living mice using a novel luxABCDE construct. Infect. Immun. 68:3594–3600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Francis KP, et al. 2001. Visualizing pneumococcal infections in the lungs of live mice using bioluminescent Streptococcus pneumoniae transformed with a novel gram-positive lux transposon. Infect. Immun. 69:3350–3358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gardner P, Smith DH, Beer H, Moellering RC., Jr 1969. Recovery of resistance (R) factors from a drug-free community. Lancet ii:774–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grady R, Hayes F. 2003. Axe-Txe, a broad-spectrum proteic toxin-antitoxin system specified by a multidrug-resistant, clinical isolate of Enterococcus faecium. Mol. Microbiol. 47:1419–1432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gutschik E, Moller S, Christensen N. 1979. Experimental endocarditis in rabbits. 3. Significance of the proteolytic capacity of the infecting strains of Streptococcus faecalis. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Immunol. Scand. B 87:353–362 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hanin A, et al. 2010. Screening of in vivo activated genes in Enterococcus faecalis during insect and mouse infections and growth in urine. PLoS One 5:e11879 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Haug MC, Tanner SA, Lacroix C, Meile L, Stevens MJ. 2010. Construction and characterization of Enterococcus faecalis CG110/gfp/pRE25*, a tool for monitoring horizontal gene transfer in complex microbial ecosystems. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 313:111–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Holo H, Nes IF. 1989. High-frequency transformation, by electroporation, of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris grown with glycine in osmotically stabilized media. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 55:3119–3123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Huycke MM, Spiegel CA, Gilmore MS. 1991. Bacteremia caused by hemolytic, high-level gentamicin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:1626–1634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ike Y, Hashimoto H, Clewell DB. 1984. Hemolysin of Streptococcus faecalis subspecies zymogenes contributes to virulence in mice. Infect. Immun. 45:528–530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jett BD, Huycke MM, Gilmore MS. 1994. Virulence of enterococci. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 7:462–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jett BD, Jensen HG, Nordquist RE, Gilmore MS. 1992. Contribution of the pAD1-encoded cytolysin to the severity of experimental Enterococcus faecalis endophthalmitis. Infect. Immun. 60:2445–2452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Joyce SA, Gahan CG. 2010. Molecular pathogenesis of Listeria monocytogenes in the alternative model host Galleria mellonella. Microbiology 156:3456–3468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kuklin NA, et al. 2003. Real-time monitoring of bacterial infection in vivo: development of bioluminescent staphylococcal foreign-body and deep-thigh-wound mouse infection models. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2740–2748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lane MC, Alteri CJ, Smith SN, Mobley HL. 2007. Expression of flagella is coincident with uropathogenic Escherichia coli ascension to the upper urinary tract. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:16669–16674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Leblanc DJ, Lee LN. 1984. Physical and genetic analyses of streptococcal plasmid pAM beta 1 and cloning of its replication region. J. Bacteriol. 157:445–453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lebreton F, et al. 2011. Galleria mellonella as a model for studying Enterococcus faecium host persistence. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 21:191–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Maekawa S, Yoshioka M, Kumamoto Y. 1992. Proposal of a new scheme for the serological typing of Enterococcus faecalis strains. Microbiol. Immunol. 36:671–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McCullers JA, Karlstrom A, Iverson AR, Loeffler JM, Fischetti VA. 2007. Novel strategy to prevent otitis media caused by colonizing Streptococcus pneumoniae. PLoS Pathog. 3:e28 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0030028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Monack DM, Bouley DM, Falkow S. 2004. Salmonella typhimurium persists within macrophages in the mesenteric lymph nodes of chronically infected Nramp1#x002B;/#x002B; mice and can be reactivated by IFNgamma neutralization. J. Exp. Med. 199:231–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mook-Kanamori BB, et al. 2009. Daptomycin in experimental murine pneumococcal meningitis. BMC Infect. Dis. 9:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Moritz EM, Hergenrother PJ. 2007. Toxin-antitoxin systems are ubiquitous and plasmid-encoded in vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:311–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Morrissey R, et al. 2011. Real-time monitoring of luciferase-tagged Cronobacter sakazakii in reconstituted infant milk formula. J. Food Prot. 74:573–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mundy LM, Sahm DF, Gilmore M. 2000. Relationships between enterococcal virulence and antimicrobial resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:513–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Murray BE, et al. 1993. Generation of restriction map of Enterococcus faecalis OG1 and investigation of growth requirements and regions encoding biosynthetic function. J. Bacteriol. 175:5216–5223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Olsen RJ, Watkins ME, Cantu CC, Beres SB, Musser JM. 2011. Virulence of serotype M3 Group A Streptococcus strains in wax worms (Galleria mellonella larvae). Virulence 2:111–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Park SY, Kim KM, Lee JH, Seo SJ, Lee IH. 2007. Extracellular gelatinase of Enterococcus faecalis destroys a defense system in insect hemolymph and human serum. Infect. Immun. 75:1861–1869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Qazi SN, et al. 2001. agr expression precedes escape of internalized Staphylococcus aureus from the host endosome. Infect. Immun. 69:7074–7082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ramphal R, et al. 2008. Control of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the lung requires the recognition of either lipopolysaccharide or flagellin. J. Immunol. 181:586–592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Riedel CU, et al. 2007. Construction of p16Slux, a novel vector for improved bioluminescent labeling of gram-negative bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:7092–7095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Riedel CU, et al. 2007. Improved luciferase tagging system for Listeria monocytogenes allows real-time monitoring in vivo and in vitro. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:3091–3094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Russel WMS, Burch RL. 1959. The principles of humane experimental technique. Methuen, London, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sahm DF, et al. 1989. In vitro susceptibility studies of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 33:1588–1591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schlievert PM, et al. 1998. Aggregation and binding substances enhance pathogenicity in rabbit models of Enterococcus faecalis endocarditis. Infect. Immun. 66:218–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shankar N, et al. 2001. Role of Enterococcus faecalis surface protein Esp in the pathogenesis of ascending urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 69:4366–4372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Simon D, Chopin A. 1988. Construction of a vector plasmid family and its use for molecular cloning in Streptococcus lactis. Biochimie 70:559–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Solheim M, et al. 2011. Comparative genomic analysis reveals significant enrichment of mobile genetic elements and genes encoding surface structure-proteins in hospital-associated clonal complex 2 Enterococcus faecalis. BMC Microbiol. 11:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Thomas VC, et al. 2009. A fratricidal mechanism is responsible for eDNA release and contributes to biofilm development of Enterococcus faecalis. Mol. Microbiol. 72:1022–1036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. van der Vossen JM, van der Lelie D, Venema G. 1987. Isolation and characterization of Streptococcus cremoris Wg2-specific promoters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 53:2452–2457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Vebø HC, Solheim M, Snipen L, Nes IF, Brede DA. 2010. Comparative genomic analysis of pathogenic and probiotic Enterococcus faecalis isolates, and their transcriptional responses to growth in human urine. PLoS One 5:e12489 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]