Abstract

At Schizosaccharomyces pombe centromeres, heterochromatin formation is required for de novo incorporation of the histone H3 variant CENP-ACnp1, which in turn directs kinetochore assembly and ultimately chromosome segregation during mitosis. Noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) transcribed by RNA polymerase II (Pol II) directs heterochromatin formation through not only the RNA interference (RNAi) machinery but also RNAi-independent RNA processing factors. Control of centromeric ncRNA transcription is therefore a key factor for proper centromere function. We here demonstrate that Mediator directs ncRNA transcription and regulates centromeric heterochromatin formation in fission yeast. Mediator colocalizes with Pol II at centromeres, and loss of the Mediator subunit Med20 causes a dramatic increase in pericentromeric transcription and desilencing of the core centromere. As a consequence, heterochromatin formation is impaired via both the RNAi-dependent and -independent pathways, resulting in loss of CENP-ACnp1 from the core centromere, a defect in kinetochore function, and a severe chromosome segregation defect. Interestingly, the increased centromeric transcription observed in med20Δ cells appears to directly block CENP-ACnp1 incorporation since inhibition of Pol II transcription can suppress the observed phenotypes. Our data thus identify Mediator as a crucial regulator of ncRNA transcription at fission yeast centromeres and add another crucial layer of regulation to centromere function.

INTRODUCTION

The kinetochore serves as the attachment point for spindle microtubules during mitotic and meiotic cell divisions. It is assembled on a specialized chromatin domain called the centromere, which is subject to epigenetic control (16). In Schizosaccharomyces pombe the centromere contains a central core region that is flanked by two types of repeat regions; the innermost region (imr) contains several tRNA genes, whereas the outermost region (otr) harbors the dh and dg elements. These flanking pericentromeric repeat regions are organized into heterochromatin and are transcriptionally silent (45). The central core region functions as a platform for formation of the kinetochore structure, and it contains the unique histone H3 variant CENP-ACnp1 (6). CENP-ACnp1 incorporation is critical for centromere function, and depletion of it leads to loss of other kinetochore proteins and to chromosome segregation defects (43).

Heterochromatin organization and transcription silencing at the centromere are regulated processes, which involve transcription of the centromeric repeat regions by polymerase II (Pol II) to produce noncoding RNA (ncRNA) (9, 13). Mutations in genes encoding the Pol II subunit can impair production of small interfering RNA (siRNA) and heterochromatin formation (14, 26). The ncRNA is complemented to double-strand RNA by the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (Rdp1) (37, 52). The RNase III helicase, Dcr1, cleaves the double-strand RNA into siRNA, which interferes with the transcription of the centromeric repeat regions themselves (12). The siRNAs are bound by the RNA-induced transcription-silencing (RITS) complex, which is recruited to heterochromatin by interactions with H3–lysine-9 methylation (H3K9me) (40, 50, 54). RITS, in turn, stimulates recruitment of Clr4, which methylates H3K9, thus creating a positive feedback loop with increasing levels of H3K9me (62). The H3K9me mark is recognized and bound by Swi6, which is critical for heterochromatin formation and spreading in fission yeast (3, 39, 57). Furthermore, RNA interference (RNAi) also promotes termination of Pol II transcription in the pericentromeric regions and thereby prevents stalling of replication forks due to collisions of RNA and DNA polymerase (61). Recent data have also suggested a novel regulatory pathway in which the exosome RNA degradation machinery acts in parallel to the RNAi pathway to mediate heterochromatin formation (49).

Pol II also transcribes the central core region of centromeres, but the resulting ncRNA transcripts do not contribute to siRNA production but are instead rapidly degraded by the exosome (11). The functional importance and the control of central core region transcription are not yet known, and whereas RNAi-dependent regulation of pericentromeric transcription has been studied in detail, it is not known how core centromere transcription is regulated. An important coregulator of Pol II-dependent transcription at many other genomic locations is the evolutionarily conserved Mediator complex (7). This multiprotein complex serves as a bridge between gene specific regulatory proteins bound to upstream elements and the general transcription machinery (53). There is a wealth of genetic data connecting Mediator to gene regulation in eukaryotic cells, and a temperature-sensitive mutation in the essential Mediator component MED17 (SRB4) abolishes nearly all Pol II-dependent transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (55). Not only is Mediator required for gene activation, but genetic data have also connected Mediator to gene repression. The repressive effect of Mediator has primarily been linked to a subgroup of Mediator proteins, Med12, Med13, Cdk8 (cyclin-dependent kinase 8), and CycC (cyclin C), which form a specific module (the Cdk8 module) in the Mediator complex and block interactions with Pol II (18, 31). However, it is not correct to divide the Mediator into activating and repressive modules since most Mediator subunits, including the Cdk8 module, display both positive and negative effects on gene transcription (15, 21). The Med8, Med18, and Med20 proteins constitute another Mediator submodule that can affect transcription in both positive and negative directions (36). The MED18 (SRB5) and MED20 (SRB2) genes were originally identified in budding yeast as suppressors of a cold-sensitive phenotype associated with a truncation of the C-terminal domain in Rpb1, the largest subunit of Pol II (41). Structural studies have demonstrated that Med18-Med20 forms a stable heterodimer that is tethered to the Mediator complex via the C terminus of Med8 (34). The TATA box binding protein (TBP) interacts directly with the Med18-Med20 heterodimer causing structural changes in the Mediator complex that could regulate interactions with Pol II (8, 34). The Med18-Med20 heterodimer also interacts directly with Pol II via the Rpb4 and Rpb7 subunits (8). The multifaceted interactions described between Med18-Med20 and the basal transcription machinery may explain why loss of these two Mediator components leads to both positive and negative effects on global gene regulation in fission yeast (36). Even if most of the focus has been on the role for Mediator in the regulation of mRNA-encoding genes, there are recent reports that link Mediator to the control of Pol II-dependent transcription of ncRNA. In mouse embryonic stem cells, Mediator interacts with an Ada-Two-A-containing histone acetyltransferase and regulates a set of ncRNA genes (32), and in Arabidopsis thaliana, Mediator recruits Pol II to ncRNA gene promoters (30).

Here, we demonstrate that Mediator is a regulator of ncRNA transcription at fission yeast centromeres and is required for heterochromatin formation via an RNAi-independent pathway. Loss of the Mediator component Med20 impairs transcription silencing and heterochromatin formation. As a consequence, CENP-ACnp1 is lost from the centromere, which disturbs kinetochore function and causes chromosome segregation defects. Based on our studies, we suggest a model in which strict transcriptional control of the core centromeric region is required for proper CENP-ACnp1 chromatin assembly.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and growth conditions.

Spot tests were performed on complete medium (yeast extract agar [YEA]) with either 10 μg/ml thiabendazole (TBZ) or 1 g/liter 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) using 10-fold dilution steps. The cells were incubated at 25°C for 3 to 5 days. Liquid cultures were grown in complete medium (yeast extract-lactate [YEL]) at 25°C, 30°C, or 36°C. Strains were sporulated on SPAS plates. Overexpression was performed using pREP81x-vector (4) in Edinburgh minimal medium without leucine (EMM-Leu) with and without thiamine (5 μg/ml). A list of yeast strains used in this study is available upon request.

Cell cycle synchronization.

Cell cultures containing the cdc25-22 mutation were prepared at 25°C (optical density [OD] of ∼0.2). The cells were blocked at 36°C for 4 h and then released by cooling to 25°C and incubated at 25°C. At each time point ∼109 cells were collected for chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), RNA analysis, immunostaining, and septation index counting (n = 100).

Fluorescence microscopy.

Immunofluorescent staining was carried out following a procedure previously described (17). Antibodies used were anti-green fluorescent protein (anti-GFP; ab290; Abcam), anti-α-tubulin (T5168; Sigma-Aldrich), Alexa Fluor 488–goat anti-mouse IgG (A11001; Invitrogen), and Alexa Fluor 594–chicken anti-rabbit IgG (A21442; Invitrogen). Chromosome segregation defects counted as chromosome lagging follow a previously described classification (46). Cells expressing a CENP-A–cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) fusion protein were grown to an OD of 0.5. When indicated, actinomycin D (Sigma) was added to a final concentration of 10 μg/ml, and cells were incubated for another 60 min at 30°C. GFP and CFP fluorescence microscopy were performed using a Carl Zeiss Axiovert 200 M fluorescence microscope. CENP-ACnp1 signals were counted blindly. The statistical significance level was calculated using a two-sample z test.

Tiling array transcriptome, Chip-seq, and ChIP analysis.

Tiling array analysis was performed as previously described (63) using the S. pombe Tiling 1.0FR Array (900647; Affymetrix). Expression profiles for med8-598, med18Δ, med20Δ, and med12Δ were obtained from Linder et al. (36). A list of segregation-associated factors was obtained from Gene Ontology (GO) terms (GO:0007059, GO:0000775, and GO:0031497) in S. pombe (taxon 4896) from the European Bioinformatics Institute website (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/QuickGO/). ChIP assays were performed as described previously (64). ChIP with high-throughput sequencing (ChIP-seq) was performed using an Illumina Genome Analyzer according to the manufacturer's instructions. The quality check (QC) of the short reads was done by generating QC statistics with FastQC (http://www.bioinformatics.bbsrc.ac.uk/projects/fastqc). Read alignments to the NCBI assembly of the S. pombe genome were performed using Bowtie (version 0.12.7) (33), allowing up to two mismatches. Primer sequences are available on request. Antibodies used were anti-α-tubulin (T5168; Sigma-Aldrich), anti-histone H3 (ab1791; abcam), anti-H3K9me (ab1220; abcam), anti-swi6 (BAM-63-101; Cosmo Bio), anti-GFP (for immunoblotting, A10260 [Invitrogen]; for ChIP, ab290 [Abcam]), anti-RNA Pol II C-terminal domain (CTD) (ab5408; abcam), and anti-myc (M4439; Sigma-Aldrich). Ratios of IP/input are depicted in the figures after ratios obtained with no-antibody controls were subtracted.

RNA extraction and detection.

Total RNA was extracted by a standard hot phenol method (60). Small RNA molecules were isolated from total RNA using a mirVana miRNA isolation kit (Ambion) and analyzed as previously described (13). Probe sequences are available on request. The results were normalized to a U6 RNA control and calculated based on two biological repeats. Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) was performed with SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (18064-022; Invitrogen) using random primers according to the manufacturer's recommendation. RT reactions without reverse transcriptase were used as controls to monitor possible DNA contaminations. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) experiments and analysis of the results were performed as stated in ChIP methods but normalized to act+ levels. The ura4+ transcript levels were visualized on a 1% agarose gel. Primer sequences are available on request.

Microarray data accession numbers.

Raw data and signal files have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus database under accession numbers GSE32310 and GSE35527.

RESULTS

Mediator is required for centromere function.

We tested if Mediator affects centromere function in fission yeast by monitoring growth of Mediator mutant strains in the presence of the antimicrotubule drug thiabendazole (TBZ). For comparison, we used a dcr1+ deletion mutant, which impairs centromere function and displays TBZ sensitivity (47). We found three Mediator mutants, med8-598, med18Δ, and med20Δ, that were sensitive to TBZ even if the effects were milder than those seen with a dcr1Δ mutant. Some of the Mediator components investigated, e.g., Med1, Med12, Med13, and Med27, had no apparent effect on TBZ sensitivity, whereas other components, e.g., Med15 and Med31, had only a modest effect (Fig. 1A; also data not shown). Interestingly, the three TBZ-sensitive mutants are functionally related and encode proteins (Med8, Med18, and Med20) that form a submodule in the Mediator complex (34, 36). Of these three proteins, loss of Med20 has the mildest general effects on Mediator function. Furthermore, the med8-598 and med18Δ mutations both lead to concomitant loss of the Med20 protein from the Mediator complex, and we therefore decided to focus on Med20 for our further studies (36).

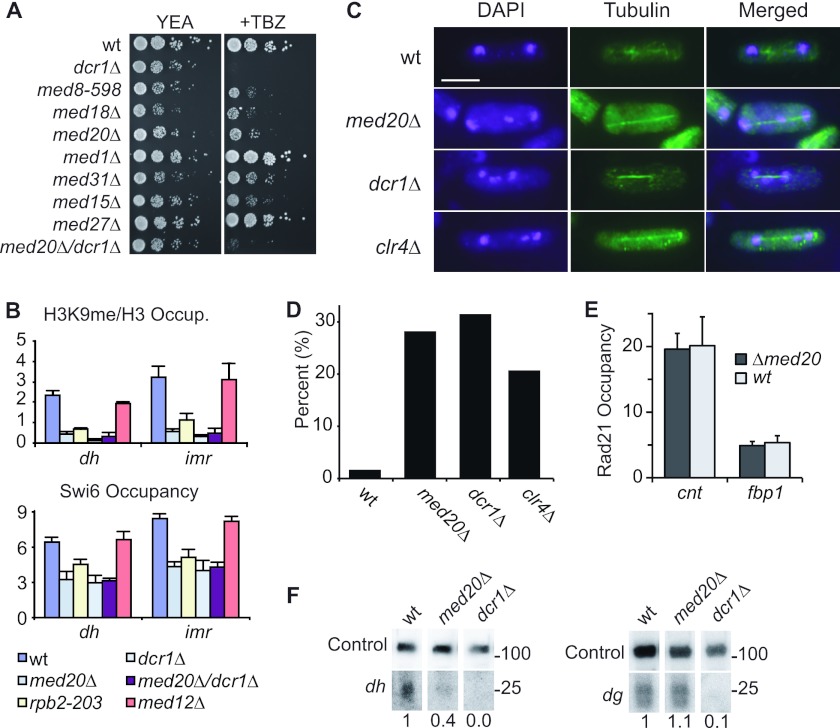

Fig 1.

Mediator components are required for chromosome segregation. (A) TBZ sensitivity test of Mediator mutants. Tenfold dilution series of the indicated strains were spotted on YEA plates with and without TBZ followed by incubation at 25°C. (B) H3K9me and Swi6 occupancy in the centromeric repeat regions (dh and imr) of chromosome I. (C) Images showing DNA content and spindle microtubules in anaphase cells of wt, med20Δ, dcr1Δ, and clr4Δ cells at 30°C. Immunofluorescent staining of tubulin, 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining, and merged images are shown as indicated. Scale bar, 5 μm. (D) Diagram showing the percentage of lagging chromosomes in anaphase cells of wt, med20Δ, dcr1Δ, and clr4Δ strains at 30°C (n = 100 to 125 per strain). (E) Rad21 occupancy in the core centromeric regions (cnt) of chromosome I and in a control locus (the fbp1 gene). (F) Northern blot showing siRNA levels using dh and dg probes. U6 RNA is used as a loading control. Relative siRNA fold changes are indicated below each lane. The locations of probes are indicated as black dots in Fig. 3C.

We used chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and monitored H3K9me and Swi6 occupancy to analyze effects on centromeric heterochromatin formation. In agreement with previous reports, a dcr1Δ strain and a strain carrying a mutation in the Rpb2 subunit of Pol II (rpb2-m203) displayed a strong reduction in H3K9me and Swi6 binding in the otr and imr regions of chromosome 1 (26, 57). Interestingly, the levels of both H3K9me and Swi6 were also significantly reduced in the med20Δ cells, indicating impaired heterochromatin formation (Fig. 1B). Mutations in the RNAi machinery that cause problems in forming a proper heterochromatin structure at centromeres ultimately affect kinetochore assembly and chromosome segregation (23). We therefore monitored the distribution of α-tubulin and DNA in med20Δ cells during mitosis. Loss of Med20 caused a severe defect in chromosome segregation (Fig. 1C and D), with a frequency of chromosome lagging of about 28.2% in anaphase cells (n = 124) compared to 1.7% in a wild-type (wt) control (n = 116). We also deleted med20 in a strain containing a disposable minichromosome with an adenine marker (1). Loss of Med20 resulted in a strong increase in minichromosome loss, further supporting the chromosome-lagging phenotype (data not shown). In mammalian cells, Mediator interacts with cohesin (24). To determine if the med20Δ deletion could influence cohesin distribution at fission yeast centromeres, we performed a ChIP analysis and analyzed the distribution of Rad21, a component of the cohesin complex. We observed no significant changes in Rad21 core centromeric occupancy in the med20Δ deletion strain (Fig. 1E). Similarly, Rad21 localization as determined by immunofluorescent microscopy was also unaffected (data not shown).

The effect of Med20 on centromere function is partially distinct from the RNAi machinery.

We hypothesized that the effects of med20Δ on centromere function could be explained by changes in pericentromeric ncRNA transcription and siRNA production. However, even if med20Δ caused a significant reduction of siRNA levels produced from dh transcripts (36% of wild-type levels), the effect was not nearly as strong as that observed in a dcr1+ deletion mutant. Furthermore, siRNA production from dg was not significantly impaired, whereas this RNA species was completely abolished upon loss of Dcr1 (Fig. 1F). The changes in siRNA production were therefore mild compared to the strong effects of the med20+ deletion on chromosome segregation. Therefore, even if the RNAi machinery could contribute to the observed phenotypes, it appeared likely that Med20 also affected chromosome segregation through a mechanism that was distinct from the RNAi pathway.

Mediator interacts directly with centromeres.

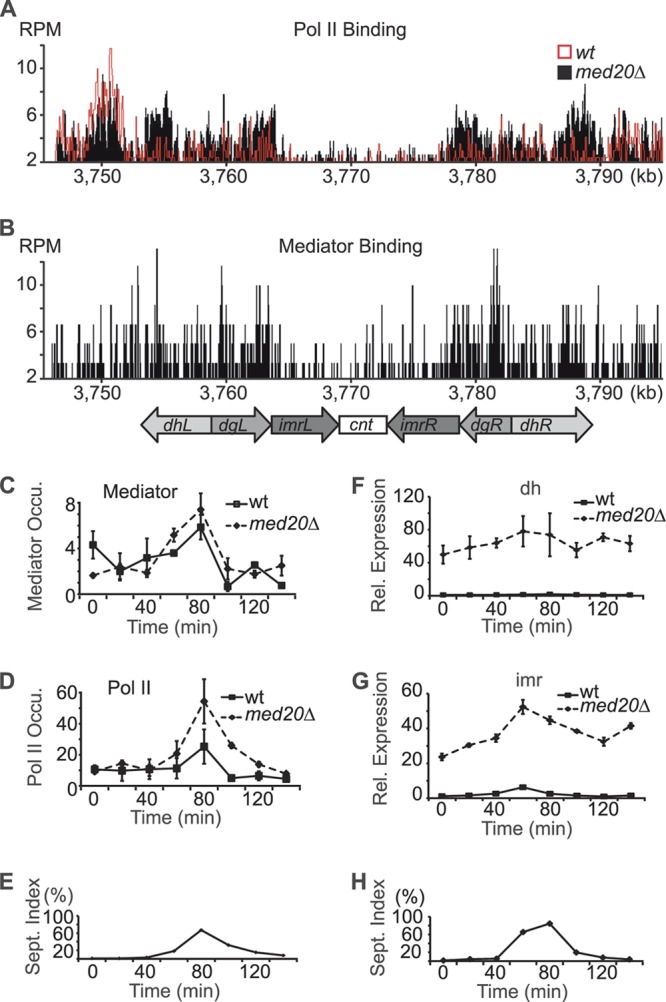

To investigate if Mediator interacted directly with the centromere region, we used ChIP followed by DNA sequencing (ChIP-seq) (Fig. 2A and B). We found a number of distinct Mediator peaks and, more importantly, a pattern of binding that was similar to that of Pol II. We observed Mediator and Pol II binding to the pericentromeric repeat regions but also lower levels of protein binding to the central core region (cnt). We also monitored Pol II binding in the med20Δ strain and observed a significant increase in the pericentromeric region but also modestly higher Pol II binding at the core centromere (Fig. 2A). Compared to many other genomic regions, the levels of Mediator and Pol II were relatively low in the centromeric region. We hypothesized that this could be due to periodic variations and that Mediator interacted with the centromeric regions only during a short phase of the cell cycle. In support of this idea, transcription of the otr and imr regions primarily occurs in S phase, when the DNA is exposed during replication (10). We therefore also investigated Mediator and Pol II occupancy during cell cycle progression when cells were synchronized with cdc25-22 block-release experiments. Even if the variations were relatively mild (about 2-fold), both Mediator and Pol II bound to the dh repeat region, with a peak in S phase (Fig. 2C and D). The periodic variation supported the ChIP-seq data and demonstrated that Mediator is directly recruited to the centromeric region. Loss of Med20 did not change the periodicity of Mediator binding (Fig. 2C) but did cause a distinct increase of Pol II occupancy in the med20Δ strain (Fig. 2D). In agreement with increased Pol II binding, loss of Med20 also caused a dramatic 25- to 50-fold upregulation of transcript levels at both dh and imr (Fig. 2F and G). We could still discern a cell cycle-dependent periodicity of imr transcription in the med20Δ strain, but the levels of transcripts were much higher (Fig. 2G). We therefore conclude that loss of Med20 derepresses pericentromeric transcription without affecting Mediator recruitment.

Fig 2.

Mediator occupancy and transcription at centromeres during cell cycle progression. (A and B) Occupancy profiles for Pol II and Mediator (Med7-Myc) at centromere 1. ChIP-seq data are shown as reads per million (RPM). The centromere structure is shown aligned to the x axis. In panel A, Pol II occupancy in wt cells (red profile) are compared to that in a med20Δ mutant strain (black profile). (C and D) ChIP analyses of Med7-myc (C) and Pol II (D) occupancy in the otr (dh) region. ChIP ratios were normalized to no-antibody controls. (E) Septation index for the experiments shown in panels C and D. Peak indicating S phase. (F and G) Quantification of transcript levels by qPCR from the dh and imr regions in synchronized cells. Samples were normalized to act1+. Rel, relative. (H) Septation index for the experiments shown in panels F and G. Error bars indicate standard deviations from at least three independent experiments.

Deletion of med20+ disrupts centromeric silencing.

To further analyze silencing defects at different centromeric locations, we used a set of S. pombe strains in which the ura4+ marker had been integrated at three different regions of the fission yeast centromere (otr, imr, or cnt) (1). Growth on 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) was used as an indicator of ura4+ silencing. In agreement with our measurements of pericentromeric transcription (Fig. 2F and G), med20Δ caused derepression of the ura4+ marker gene transcription in the otr and imr regions. Interestingly, we also noted derepression of ura4+ in the cnt region. This finding was distinctly different from that seen with RNAi mutants, which disrupt silencing of otr and imr but not the cnt region (57). Another Mediator mutant, med12Δ, that did not influence TBZ sensitivity had no effect on ura4+ transcription at the locations tested (Fig. 3A). To further verify our findings, we used reverse transcription-PCR and demonstrated that ura4+ was transcribed from both the pericentromeric repeats and the centromeric core region when med20+ was deleted (Fig. 3B).

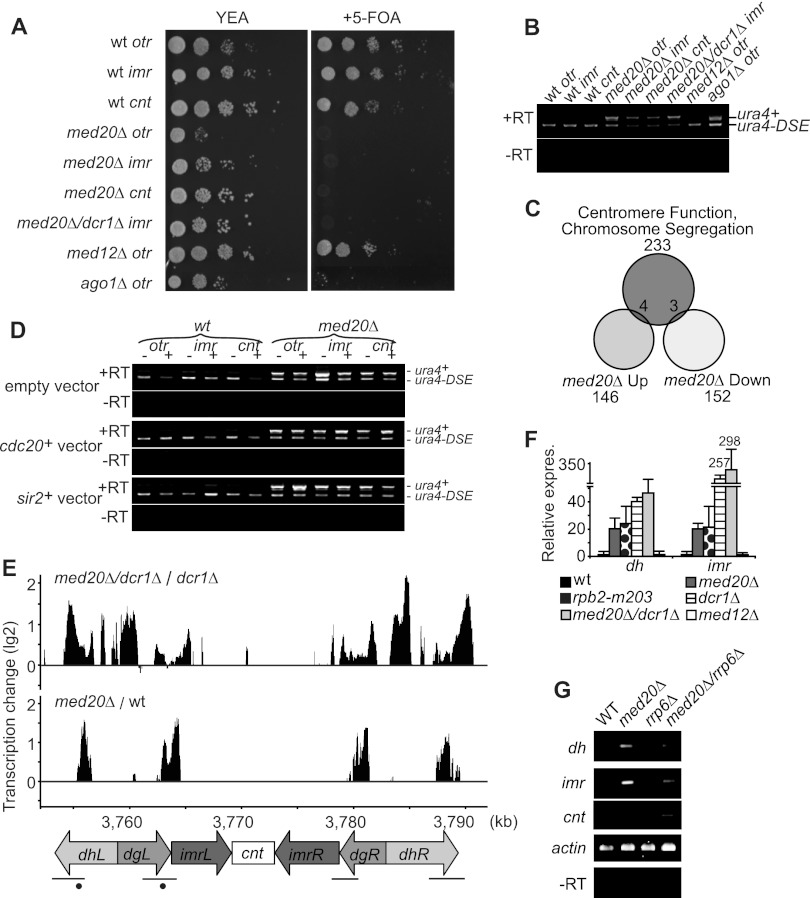

Fig 3.

Loss of Med20 causes a defect in centromeric silencing. (A) Tenfold dilutions of the indicated strains were spotted on YEA plates, with and without 5-FOA. The locations of the introduced ura4+ markers are indicated after the strain names. (B) RT-PCR showing transcript levels of the ura4+ marker and a mutated version of ura4+ (ura4-DSE) transcribed from the endogenous locus. Reactions performed without reverse transcriptase (−RT) are shown as controls. (C) A Venn diagram showing how genes involved in centromere function and chromosome segregation overlap genome-wide transcription changes (cutoff, 1.5-fold) in the med20Δ strain. (D) RT-PCR analysis of the ura4+ marker located in otr, imr, and cnt regions. cdc20+ and sir2+ are expressed from a pREP81X vector. Minus (−) indicates without induction and plus (+) indicates with gene induction. The empty vector is shown as negative control. (E) Tiling array analysis shows transcription changes in med20Δ cells normalized to the wt level and med20Δ dcr1Δ cells normalized to the dcr1Δ strain level in the chromosome I centromere region. A schematic figure of the centromere is shown aligned to the x axis. Black bars represent previously identified siRNA regions (10). Dots represent siRNA probe locations for the Northern blot analyses shown in Fig. 1F. (F) Quantification by qPCR of dh and imr transcripts. Samples are normalized to act1+ levels. Bars show standard deviations of at least three independent cultures. (G) RT-PCR showing transcript levels in the centromere regions (dh, imr, and cnt) in the wt, med20Δ, rrp6Δ, and med20Δ rrp6Δ strains. Actin and −RT are shown as controls.

Even if our findings so far pointed toward a direct effect of Mediator on centromere function, we could not exclude the possibility that indirect effects on gene transcription contributed to the observed phenotypes. Mediator is a general regulator of Pol II transcription, and deletion of med20+ could therefore affect transcription of genes involved in chromosome segregation and centromere function. To address this possibility, we used genome-wide expression data for med20Δ as well as for med8(Ts), med12Δ, med15Δ, and med18Δ (36, 38). We compared how the Mediator mutations affected transcription of a group of 233 genes required for centromere function and chromosome segregation (Fig. 3C; also data not shown). Only 7 of the 233 genes were upregulated (4 genes) or downregulated (3 genes) more than 1.5-fold in a med20Δ strain. Five out of the seven affected genes were also changed in other mediator mutants, e.g., a med12Δ strain, that did not display TBZ sensitivity (data not shown), and only two of the genes with changed transcription levels were unique to the med20Δ strain, cdc20+ (slp1+) and sir2+. It appeared unlikely that changes in the expression levels of these two genes could explain the observed effects of med20Δ on centromere function. The cdc20+ gene is required for the spindle checkpoint but has not been linked to centromeric silencing (29), and deletion of sir2+ leads to impaired silencing of imr but only weakly reduces silencing of otr and does not affect the cnt region (20, 51). To directly address the contribution of cdc20+ and sir2+ to the phenotypes observed in med20Δ cells, we overexpressed these genes in med20Δ strains with a ura4+ marker introduced at the otr, imr, or cnt region. Overexpression increased the transcript levels of cdc20+ and sir2+, but neither of the two genes could restore centromeric transcription silencing in the med20Δ strain at any of the locations investigated (Fig. 2D). Impaired transcription of cdc20+ or sir2+ could therefore not explain the centromeric silencing defect observed in the med20Δ strain.

Tiling array analysis of centromeric ncRNA transcription.

To better characterize the effects of Mediator on centromeric transcription, we performed transcriptome analysis with tiling arrays and monitored centromeric ncRNA transcription in med20Δ cells. We also profiled transcription in cells where both med20+ and dcr1+ had been deleted since it allowed us to monitor transcripts that would otherwise have been processed by the RNAi machinery (57). In the med20Δ strain, transcript levels were increased in the centromeric region compared to levels in a wild-type (wt) control (Fig. 3E). The upregulated transcripts corresponded to ncRNAs, which are processed into siRNAs (13). We observed a significant increase of the same ncRNA transcripts in the dcr1Δ strain (data not shown), and the levels were increased even further in the dcr1Δ med20Δ double mutant (Fig. 3E). These observations were verified using quantitative PCR with primers covering the otr and imr transcripts (Fig. 3F). Our findings therefore supported the observations done with synchronized cells (Fig. 2F and G) and demonstrated that med20+ is required for repression of centromeric transcripts that are subsequently used for siRNA production.

We could not observe any clear effects on cnt region transcription in the tiling array transcriptome analysis, which we expected to be a consequence of cnt transcripts being rapidly degraded by the exosome (11). To address this possibility, we used reverse transcription-PCR and monitored cnt transcription. We could not detect cnt transcripts in wt cells. Similarly, cnt transcripts were not observed in cells where med20+ or the exosome component rrp6Δ had been deleted. However, when med20+ was deleted in an rrp6Δ mutant background, cnt transcripts were detected (Fig. 3G). Based on these results, we conclude that Med20 is required for transcription silencing also at the core centromere regions but that the produced transcripts are rapidly degraded by the exosome. In contrast, the increased levels of pericentromeric transcripts (dh and imr) observed in the med20Δ strain were not significantly affected by deletion of rrp6+ (Fig. 3G).

CENP-ACnp1 incorporation is impaired in med20Δ cells.

De novo recruitment of CENP-ACnp1 to centromeres depends on pericentromeric heterochromatin formation (19). The chromosome segregation defects and impaired transcription silencing associated with med20Δ therefore prompted us to investigate effects on CENP-ACnp1 localization (58). An endogenously expressed CENP-ACnp1–CFP fusion protein was used to visualize CENP-ACnp1 positioning (2). In wt cells, a distinct CENP-ACnp1–CFP signal was observed from kinetochores, but the signals were much weaker in the med20Δ strain, and many cells did not have a localized CENP-ACnp1 signal (Fig. 4A). Impaired recruitment of CENP-ACnp1 to centromeres was confirmed by ChIP analysis, in which CENP-ACnp1 levels were reduced more than 5-fold compared to levels in a wt control (Fig. 4B). The effect appeared specific to CENP-ACnp1 since deposition of histone H3 in the surrounding pericentromeric regions was unaffected by loss of Med20 (data not shown). In budding yeast, failure of CENP-ACse4 to localize to the centromere leads to CENP-ACse4 degradation (22, 48). The situation appears to be similar in fission yeast since immunoblotting revealed a strong reduction of CENP-ACnp1 protein levels in the med20Δ strain (Fig. 4C) even though the mRNA levels for CENP-ACnp1 were unaffected (Fig. 4D). We thus concluded that Med20 is required for incorporation of CENP-ACnp1 at centromeres.

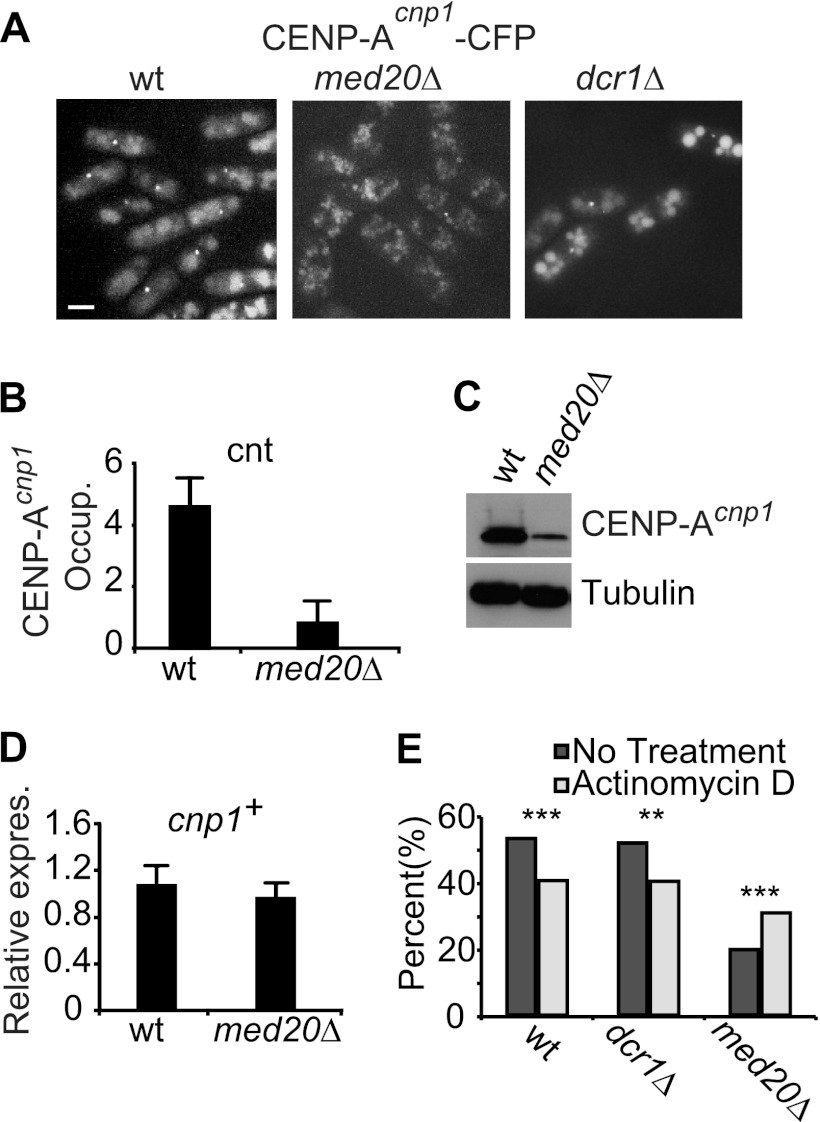

Fig 4.

Deletion of med20+ leads to loss of CENP-ACnp1. (A) Localization of CENP-ACnp1 fused to CFP in wt, med20Δ, and dcr1Δ cells. Scale bar, 5 μm. (B) ChIP analysis of CENP-ACnp1 occupancy over the cnt region. Bars show standard deviations. (C) The CENP-ACnp1 protein was detected by Western blotting using a GFP antibody. Tubulin was used as the loading control. (D) Quantification by qPCR of CENP-ACnp1 transcript levels. Bars indicate standard deviations. (E) Diagram showing the effect of actinomycin D on the percentage of cells with an identifiable CENP-ACnp1 signal in the indicated strains (n > 160 per strain). CENP-ACnp1 localization was blindly scored, and the statistical significance (**, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001) was calculated as described in Materials and Methods.

We speculated that the increased transcription observed in med20Δ cells directly blocks CENP-ACnp1 chromatin assembly. This model would connect the observed effect on transcription with the chromosome segregation defects found in med20Δ cells. To address this possibility, we used the transcription inhibitor actinomycin D (dactinomycin), which inhibits RNA polymerases in eukaryotic cells (5). In wt and dcr1Δ cells, actinomycin D caused a slight reduction of CENP-ACnp1 incorporation. In contrast, the levels of CENP-ACnp1 were significantly increased in med20Δ cells, and the percentage of cells with a localized CENP-ACnp1 signal increased from 21% to 32% (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4E). These results demonstrate that the effect seen in med20Δ cells is at least partially transcription dependent and suggest that Mediator-dependent repression of centromeric transcription is essential for CENP-ACnp1 chromatin assembly.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we demonstrate that the Mediator complex is required for proper centromere function in S. pombe. Loss of the Med20 subunit leads to upregulation of centromeric ncRNA transcription, impaired heterochromatin formation, and reduced CENP-ACnp1 incorporation. CENP-ACnp1 is required for proper kinetochore assembly (44), explaining the dramatic defect on chromosome segregation, with lagging chromosomes seen in the med20Δ strain. The phenotypes are in some aspects different, and the effects are even more pronounced than those observed for mutations in the RNAi machinery (56).

Based on our results, we would like to propose a tentative model for Mediator-dependent CENP-ACnp1 incorporation at centromeres (Fig. 5). As demonstrated here, the Mediator complex binds to the centromere region and regulates Pol II binding and activity. The effect on Pol II transcription is most likely direct since the Med18-Med20 heterodimer has been shown to physically interact with both TBP and Pol II (8, 34). It is thus possible that Med20 may repress TBP and/or Pol II recruitment during certain phases of the cell cycle, thereby affecting preinitiation complex formation at centromeric transcription units. Interestingly, the interactions between Med18-Med20 and Pol II are mediated by the polymerase subunits Rpb4 and Rpb7 in budding yeast. This observation may be of relevance since we have previously reported that a mutation in the rpb7+ gene can impair centromeric transcription and RNAi-directed chromatin silencing in fission yeast (14).

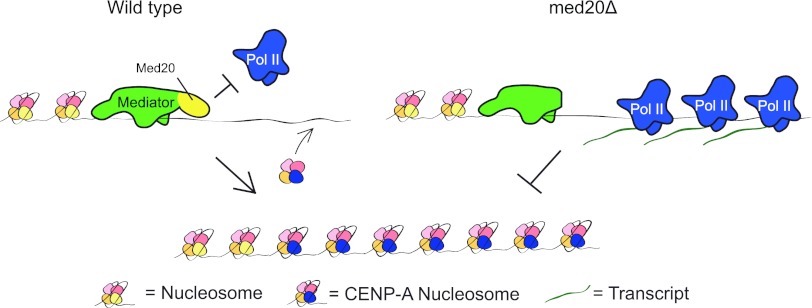

Fig 5.

A suggested model for the function of Mediator at centromeres. The Mediator complex binds to the core centromere region and regulates Pol II binding and activity. Med20 represses Pol II binding to the cnt region, which promotes incorporation of CENP-ACnp1 at the core centromere, forming a silenced chromatin structure. Disruption of med20+ (indicated in yellow) causes unregulated binding of Pol II to the centromere. The continued transcription impairs the incorporation of CENP-ACnp1, which leads to a dysfunctional kinetochore and chromosome segregation defects.

Our data reveal that Mediator-dependent transcription regulation is critical for establishment of the correct chromatin structure in both the pericentromeric and centromeric regions. Deregulated transcription may affect chromatin structure in at least two different ways. First, efficient siRNA production from the dh region transcripts may require precise regulation of ncRNA transcription, which would explain why the observed increase in ncRNA transcript levels results in lower, and not higher, levels of siRNA. Second, loss of regulation leading to higher transcription levels may in itself physically disturb heterochromatin formation either by recruiting chromatin-remodeling complexes in a manner which is not properly coordinated with cell cycle progression or by interfering with the CENP-ACnp1 loading machinery.

According to our model, Mediator-dependent transcription repression is also important for the correct incorporation of CENP-ACnp1 at the centromere core region. Disruption of med20+ impairs repression of Pol II activity and leads to a strong upregulation of the centromere core region transcription, which in turn causes decreased CENP-ACnp1 incorporation (Fig. 5). Here, direct effects on transcript levels are more difficult to observe. In fact, the exosome appears to efficiently degrade the centromere core region transcripts as they are being formed, suggesting that it is the transcription process per se that influences CENP-ACnp1 incorporation and not the ncRNA products formed. Eventually, loss of CENP-ACnp1 results in a dysfunctional kinetochore and chromosome segregation defects. Overall CENP-ACnp1 levels are dramatically decreased. We believe that this effect is similar to that seen in S. cerevisiae, where CENP-ACse4 is rapidly degraded when it is not present in chromatin.

The idea that the basal transcription machinery may be involved in centromere assembly in fission yeast is consistent also with studies of the transcription elongation factor Spt6. Deletion of the spt6+ gene leads to similar centromeric defects as med20Δ, i.e., strongly increased levels of Pol II and noncoding RNA and impaired heterochromatin formation with reduced H3K9me and Swi6. In addition, siRNAs produced from the centromeric dh and dg repeats are decreased (28). In view of the effects reported here for Med20 deficiency, it will be interesting to see whether CENP-ACnp1 assembly is affected also in spt6Δ cells.

Mediator may also affect centromere function by additional pathways. One factor required for proper CENP-ACnp1 incorporation is Hrp1. This is a CHD1 ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling factor, which has been shown to interact directly with the centromere during DNA replication in early S phase (11, 58). Interestingly, we have recently demonstrated that Hrp1 is also a transient component of the Mediator complex in fission yeast (27). This observation raises the interesting possibility that Mediator not only regulates ncRNA transcription in the central core region but also affects the activity of Hrp1 at specific centromeric nucleosomes; i.e., Mediator can effect CENP-ACnp1 incorporation by partially independent mechanisms. In fact, a similar mechanism may also exist in higher cells since human Mediator has been shown to functionally interact with the Hrp1 homologue, Chd1 (35).

In Arabidopsis thaliana, a med20+ homologue regulates production of long noncoding scaffold RNA molecules from heterochromatin, which are subsequently used by the RNAi machinery (30). This observation raises the interesting possibility that Mediator has a conserved role in heterochromatin formation and that its role for centromere function may be conserved also in other eukaryotes. However, there are also species-specific differences since loss of Med20 led to reduced pericentromeric ncRNA transcripts and Pol II occupancy in A. thaliana, whereas the opposite effect was observed when med20+ was deleted in fission yeast. In future studies, it will be important to investigate effects of Mediator on mammalian centromeres, which, similar to fission yeast, also depend on the RNAi machinery for proper centromere function (25). Comparative studies in budding yeast may also be relevant. Centromeric transcription is required for incorporation of the S. cerevisiae CENP-A homologue, Cse4, even if budding yeast centromeres are distinctly different from those in fission yeast and human cells (42). Interestingly, previous studies have identified the mediator component Med11 (Cse2) as required for proper chromosome segregation in S. cerevisiae (59), which could indicate that Mediator regulates centromeric transcription and Cse4 incorporation also in budding yeast. Further studies are required to establish what seems to be an evolutionarily conserved role for Mediator in regulation of centromere function and chromosome inheritance in the different branches of the eukaryotic kingdom.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Per Sunnerhagen and Ka-Wei Tang for supplying reagents and Shiv I. S. Grewal for supplying yeast strains. Imaging was performed at the Centre for Cellular Imaging at the Sahlgrenska Academy.

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Cancer Society (to K.E. and C.M.G.), Swedish Research Council (to K.E., B.L., and C.M.G.), the Göran Gustafssons Foundation for Research in Natural Sciences (to K.E.), the Assar Gabrielssons Foundation (to X.Z.), the Science Faculty of the University of Gothenburg (to B.L.), and Signhild Engkvists Foundation (to B.L.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 30 July 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Allshire RC, Nimmo ER, Ekwall K, Javerzat JP, Cranston G. 1995. Mutations derepressing silent centromeric domains in fission yeast disrupt chromosome segregation. Genes Dev. 9: 218–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Appelgren H, Kniola B, Ekwall K. 2003. Distinct centromere domain structures with separate functions demonstrated in live fission yeast cells. J. Cell Sci. 116: 4035–4042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bannister AJ, et al. 2001. Selective recognition of methylated lysine 9 on histone H3 by the HP1 chromo domain. Nature 410: 120–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Basi G, Schmid E, Maundrell K. 1993. TATA box mutations in the Schizosaccharomyces pombe nmt1 promoter affect transcription efficiency but not the transcription start point or thiamine repressibility. Gene 123: 131–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bensaude O. 2011. Inhibiting eukaryotic transcription: Which compound to choose? How to evaluate its activity? Transcription 2: 103–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bernad R, Sanchez P, Losada A. 2009. Epigenetic specification of centromeres by CENP-A. Exp. Cell Res. 315: 3233–3241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bjorklund S, Gustafsson CM. 2005. The yeast Mediator complex and its regulation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 30: 240–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cai G, et al. 2010. Mediator head module structure and functional interactions. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17: 273–279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cam HP, Chen ES, Grewal SI. 2009. Transcriptional scaffolds for heterochromatin assembly. Cell 136: 610–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen ES, et al. 2008. Cell cycle control of centromeric repeat transcription and heterochromatin assembly. Nature 451: 734–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Choi ES, et al. 2011. Identification of non-coding transcripts from within CENP-A chromatin at fission yeast centromeres. J. Biol. Chem. 286: 23600–23607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Creamer KM, Partridge JF. 2011. RITS-connecting transcription, RNA interference, and heterochromatin assembly in fission yeast. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2: 632–646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Djupedal I, et al. 2009. Analysis of small RNA in fission yeast; centromeric siRNAs are potentially generated through a structured RNA. EMBO J. 28: 3832–3844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Djupedal I, et al. 2005. RNA Pol II subunit Rpb7 promotes centromeric transcription and RNAi-directed chromatin silencing. Genes Dev. 19: 2301–2306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Donner AJ, Ebmeier CC, Taatjes DJ, Espinosa JM. 2010. CDK8 is a positive regulator of transcriptional elongation within the serum response network. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17: 194–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ekwall K. 2007. Epigenetic control of centromere behavior. Annu. Rev. Genet. 41: 63–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ekwall K, et al. 1996. Mutations in the fission yeast silencing factors clr4+ and rik1+ disrupt the localisation of the chromo domain protein Swi6p and impair centromere function. J. Cell Sci. 109: 2637–2648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Elmlund H, et al. 2006. The cyclin-dependent kinase 8 module sterically blocks Mediator interactions with RNA polymerase II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103: 15788–15793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Folco HD, Pidoux AL, Urano T, Allshire RC. 2008. Heterochromatin and RNAi are required to establish CENP-A chromatin at centromeres. Science 319: 94–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Freeman-Cook LL, et al. 2005. Conserved locus-specific silencing functions of Schizosaccharomyces pombe sir2+. Genetics 169: 1243–1260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Galbraith MD, Donner AJ, Espinosa JM. 2010. CDK8: a positive regulator of transcription. Transcription 1: 4–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gkikopoulos T, et al. 2011. The SWI/SNF complex acts to constrain distribution of the centromeric histone variant Cse4. EMBO J. 30: 1919–1927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hall IM, Noma K, Grewal SI. 2003. RNA interference machinery regulates chromosome dynamics during mitosis and meiosis in fission yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100: 193–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kagey MH, et al. 2010. Mediator and cohesin connect gene expression and chromatin architecture. Nature 467: 430–435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kanellopoulou C, et al. 2005. Dicer-deficient mouse embryonic stem cells are defective in differentiation and centromeric silencing. Genes Dev. 19: 489–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kato H, et al. 2005. RNA polymerase II is required for RNAi-dependent heterochromatin assembly. Science 309: 467–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Khorosjutina O, et al. 2010. A chromatin-remodeling protein is a component of fission yeast mediator. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 29729–29737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kiely CM, et al. 2011. Spt6 is required for heterochromatic silencing in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31: 4193–4204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kim SH, Lin DP, Matsumoto S, Kitazono A, Matsumoto T. 1998. Fission yeast Slp1: an effector of the Mad2-dependent spindle checkpoint. Science 279: 1045–1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim YJ, et al. 2011. The role of Mediator in small and long noncoding RNA production in Arabidopsis thaliana. EMBO J. 30: 814–822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Knuesel MT, Meyer KD, Bernecky C, Taatjes DJ. 2009. The human CDK8 subcomplex is a molecular switch that controls Mediator coactivator function. Genes Dev. 23: 439–451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Krebs AR, et al. 2010. ATAC and Mediator coactivators form a stable complex and regulate a set of non-coding RNA genes. EMBO Rep. 11: 541–547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. 2009. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 10: R25 doi:10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lariviere L, et al. 2006. Structure and TBP binding of the Mediator head subcomplex Med8-Med18-Med20. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13: 895–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lin JJ, et al. 2011. Mediator coordinates PIC assembly with recruitment of CHD1. Genes Dev. 25: 2198–2209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Linder T, et al. 2008. Two conserved modules of Schizosaccharomyces pombe Mediator regulate distinct cellular pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 36: 2489–2504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lipardi C, Wei Q, Paterson BM. 2001. RNAi as random degradative PCR: siRNA primers convert mRNA into dsRNAs that are degraded to generate new siRNAs. Cell 107: 297–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Miklos I, et al. 2008. Genomic expression patterns in cell separation mutants of Schizosaccharomyces pombe defective in the genes sep10+ and sep15+ coding for the Mediator subunits Med31 and Med8. Mol. Genet. Genomics 279: 225–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nakayama J, Rice JC, Strahl BD, Allis CD, Grewal SI. 2001. Role of histone H3 lysine 9 methylation in epigenetic control of heterochromatin assembly. Science 292: 110–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Noma K, et al. 2004. RITS acts in cis to promote RNA interference-mediated transcriptional and post-transcriptional silencing. Nat. Genet. 36: 1174–1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nonet ML, Young RA. 1989. Intragenic and extragenic suppressors of mutations in the heptapeptide repeat domain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae RNA polymerase II. Genetics 123: 715–724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ohkuni K, Kitagawa K. 2011. Endogenous transcription at the centromere facilitates centromere activity in budding yeast. Curr. Biol. 21: 1695–1703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pauleau AL, Erhardt S. 2011. Centromere regulation: new players, new rules, new questions. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 90: 805–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pidoux AL, Allshire RC. 2004. Kinetochore and heterochromatin domains of the fission yeast centromere. Chromosome Res. 12: 521–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pidoux AL, Allshire RC. 2005. The role of heterochromatin in centromere function. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 360: 569–579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pidoux AL, Uzawa S, Perry PE, Cande WZ, Allshire RC. 2000. Live analysis of lagging chromosomes during anaphase and their effect on spindle elongation rate in fission yeast. J. Cell Sci. 113: 4177–4191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Provost P, et al. 2002. Dicer is required for chromosome segregation and gene silencing in fission yeast cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99: 16648–16653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ranjitkar P, et al. 2010. An E3 ubiquitin ligase prevents ectopic localization of the centromeric histone H3 variant via the centromere targeting domain. Mol. Cell 40: 455–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Reyes-Turcu FE, Zhang K, Zofall M, Chen E, Grewal SI. 2011. Defects in RNA quality control factors reveal RNAi-independent nucleation of heterochromatin. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18: 1132–1138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schalch T, et al. 2009. High-affinity binding of Chp1 chromodomain to K9 methylated histone H3 is required to establish centromeric heterochromatin. Mol. Cell 34: 36–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shankaranarayana GD, Motamedi MR, Moazed D, Grewal SI. 2003. Sir2 regulates histone H3 lysine 9 methylation and heterochromatin assembly in fission yeast. Curr. Biol. 13: 1240–1246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sijen T, et al. 2001. On the role of RNA amplification in dsRNA-triggered gene silencing. Cell 107: 465–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Spahr H, et al. 2003. Mediator influences Schizosaccharomyces pombe RNA polymerase II-dependent transcription in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 51301–51306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sugiyama T, Cam H, Verdel A, Moazed D, Grewal SI. 2005. RNA-dependent RNA polymerase is an essential component of a self-enforcing loop coupling heterochromatin assembly to siRNA production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102: 152–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Thompson CM, Young RA. 1995. General requirement for RNA polymerase II holoenzymes in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92: 4587–4590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Volpe T, et al. 2003. RNA interference is required for normal centromere function in fission yeast. Chromosome Res. 11: 137–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Volpe TA, et al. 2002. Regulation of heterochromatic silencing and histone H3 lysine-9 methylation by RNAi. Science 297: 1833–1837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Walfridsson J, et al. 2005. The CHD remodeling factor Hrp1 stimulates CENP-A loading to centromeres. Nucleic Acids Res. 33: 2868–2879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Xiao ZX, Fitzgerald-Hayes M. 1995. Functional interaction between the CSE2 gene product and centromeres in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Mol. Biol. 248: 255–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Xue Y, et al. 2004. A DNA microarray for fission yeast: minimal changes in global gene expression after temperature shift. Yeast 21: 25–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zaratiegui M, et al. 2011. RNAi promotes heterochromatic silencing through replication-coupled release of RNA Pol II. Nature 479: 135–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zhang K, Mosch K, Fischle W, Grewal SI. 2008. Roles of the Clr4 methyltransferase complex in nucleation, spreading and maintenance of heterochromatin. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15: 381–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zhu X, Gustafsson CM. 2009. Distinct differences in chromatin structure at subtelomeric X and Y′ elements in budding yeast. PLoS One 4: e6363 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zhu X, et al. 2006. Genome-wide occupancy profile of mediator and the Srb8-11 module reveals interactions with coding regions. Mol. Cell 22: 169–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]