Abstract

The binding affinities at rat A1, A2a, and A3 adenosine receptors of a wide range of derivatives of adenosine have been determined. Sites of modification include the purine moiety (1-, 3-, and 7-deaza; halo, alkyne, and amino substitutions at the 2- and 8-positions; and N6-CH2-ring, -hydrazino, and -hydroxylamino) and the ribose moiety (2′-, 3′-, and 5′-deoxy; 2′- and 3′-O-methyl; 2′-deoxy 2′-fluoro; 6′-thio; 5′-uronamide; carbocyclic; 4′- or 3′-methyl; and inversion of configuration). (−)- and (+)-5′-Noraristeromycin were 48- and 21-fold selective, respectively, for A2a vs A1 receptors. 2-Chloro-6′-thioadenosine displayed a Ki value of 20 nM at A2a receptors (15-fold selective vs A1). 2-Chloroadenin-9-yl(β-L-2′-deoxy-6′-thiolyxofuranoside) displayed a Ki value of 8 μM at A1 receptors and appeared to be an antagonist, on the basis of the absence of a GTP-induced shift in binding vs a radiolabeled antagonist (8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine). 2-Chloro-2′-deoxyadenosine and 2-chloroadenin-9-yl(β-D-6′-thioarabinoside) were putative partial agonists at A1 receptors, with Ki values of 7.4 and 5.4 μM, respectively. The A2a selective agonist 2-(1-hexynyl)-5′-(N-ethylcarbamoyl)adenosine displayed a Ki value of 26 nM at A3 receptors. The 4′-methyl substitution of adenosine was poorly tolerated, yet when combined with other favorable modifications, potency was restored. Thus, N6-benzyl-4′-methyladenosine-5′-(N-methyluronamide) displayed a Ki value of 604 nM at A3 receptors and was 103- and 88-fold selective vs A1 and A2a receptors, respectively. This compound was a full agonist in the A3-mediated inhibition of adenylate cyclase in transfected CHO cells. The carbocyclic analogue of N6-(3-iodobenzyl)adenosine-5′-(N-methyluronamide) was 2-fold selective for A3 vs A1 receptors and was nearly inactive at A2a receptors.

Introduction

The adenosine receptors are members of the super-family of receptors coupled to guanyl nucleotide-binding proteins (G-proteins). The are composed of seven transmembrane helical domains.1 Adenosine mediates a wide variety of physiological functions including vasodilatation, vasoconstriction in the kidney, cardiac depression, inhibition of lipolysis, inhibition of platelet aggregation, inhibition of lymphocyte functions, inhibition of insulin release and potentiation of glucagon release in the pancreas, inhibition of neurotransmitter release from nerve endings, stimulation of steroidogenesis, and potentiation of histamine release from mast cells.1–5 The A1, A2a, A2b, and A3 adenosine receptors have been cloned from several species, including in each case rat, dog, mouse, and human.6 Activation of A1 and A3 receptors causes the inhibition of adenylate cyclase, activation of phospholipase C, activation of potassium channels, and inhibition of calcium channels.4,5 The A2a and A2b receptors activate adenylate cyclase via G-protein coupling.5

Numerous structure–activity relationship studies of adenosine responses have been published (see ref 1). The objectives of these studies have been to discover highly potent analogues of adenosine, long-acting and nonmetabolizable agonists and antagonists, and analogues which are specific for a subtype of adenosine receptors. The recent discovery of the novel rat A3 adenosine receptor subtype7 prompted us to undertake a detailed examination of a variety of nucleoside analogues as ligands for A3 and other adenosine receptors. Agents selective for A3 receptors8–10 have promise as agents for treating ischemia of the brain and heart,11,12 inflammation, and asthma.13 This study is a survey of some known and some novel modifications of adenosine to identify structural changes that result in selectivity.

Since some adenine and adenosine derivatives have been shown to be adenosine receptor antagonists,15,26 we have examined potential new leads for adenosine derivatives as selective antagonists. A selective antagonist at the rat A3 receptor is lacking. Several xanthine analogues that act as the potent antagonists at rat, rabbit, and human A1 and A2 receptors only weakly displaced the binding of radioligand from cloned rat A3 receptors.16

Results

Chemistry

Adenosine analogues containing a variety of structural modification (compounds 1–44) were examined in this study. The affinity of the adenosine analogues at A1, A2a, and A3 receptors was established in binding assays17–19 (Table 1). Physical data for new adenosine analogues are listed in Table 2. Compounds 10b24b and 12b52 were prepared according to literature-known procedures.

Table 1.

Affinities of Adenosine Derivatives in Radioligand Binding Assays at Rat Brain A1, A2a, and A3 Receptorsa–c,g

| a. Non-N6-substituted Derivatives

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Compound | Structure | R2= | Ki (μM) or % displacement at 10−4 Mg | |||

| Ki(A1)a | Ki(A2a)b | Ki(A3)c | Reference | |||

| 1 | A-Rib | Cl | 0.0093 | 0.063 | 1.89d | 9 |

| 2 |

|

- | 0.226 ±0.028 | 0.163 ±0.040 | 2.48±0.36 | 42 |

| 3 | A-Rib | F | 0.0059 | 0.028 | 10.4±2.3 | 43 |

| 4 |

|

- | 41% | 22.7 | 31%d | 9 |

| 5 |

|

- | 53%h | 24.1 | 26% | 23,38 |

| 6 |

|

- | 11.4h | 11.5 | 31% | 23,38 |

| 7 |

|

H | 3±1% | 0% | 200±8 | - |

| 8 |

|

H | 0.269 | 0.596 | 2.83d | 9 |

| 9 |

|

H | 12±4% | 4.30±0.41 | 66±2% | 28 |

| 10a |

|

H | 33.0±6.8 | 0.692 ±0.096 | 68±1% | 20,24 |

| 10b |

|

H | 37±7% | 41.4± 11.0 | 122± 17 | 24b |

| 11 | φ-(CH2)2 NH- | 0.98e (IC50) | 0.068f (IC50) | 25 | ||

| 12a |

|

NH2 | 30±1% | 20.8±3.7 | 199±26 | - |

| 12b |

|

NH2 | 0% | 16±5% | 198±33 | 52 |

| 12cj |

|

φ-(CH2)2NH- | 0.946 ±0.179 | 1.82±0.20i | 59.2±9.2 | - |

| 13 |

|

- | 21.5 | 59.8 | 61.7d | 9 |

| 14j |

|

- | 4% | 8% | 20% | 44 |

| 15a |

|

- | >100 | 48% | 39%d | 9 |

| 15b |

|

- | 29±6% | 11 ±2% | 70.4±2.2 | - |

| 16j |

|

- | 0% | 8% | 19% | 20,44 |

| 17 |

|

H | 29.0 | 25% | 10%d | 9 |

| 18 |

|

H | 180±40 | 8.54±1.77 | 24±1% | 24 |

| 19 |

|

Cl | 0.300 ±0.053 | 0.0198 ±0.0046 | 1.09±0.11 | 29 |

| 20 |

|

H | 20% | 26% | 24%d | 9 |

| 21 |

|

Cl | 5.36±0.87 | 7.12±1.36 | 49.3±2.2 | 29 |

| 22 |

|

Cl | 7.99±1.38 | 12.8±2.4 | 32% | 29 |

| 23 |

|

Cl | 0.640 ±0.107 | 0.897 ±0.178 | 82.4±5.2 | 30 |

| 24 |

|

H | 31% | 39% | 28%d | 9 |

| 25 |

|

Cl | 7.32±0.96 | 20.4±3.5 | 207±8 | 46 |

| 26 |

|

- | 29.0±4.4 | 35±3% | 21% | 31 |

| 27 |

|

- | 101±19 | 55.5±2.8 | 16% | 32 |

| 28a |

|

H | 29% | 49% | 43%d | 9 |

| 28b |

|

H | 0% | 8% | 11% | - |

| 29a |

|

H | 51.0±5.5 | 13% | 9% | 49 |

| 29b |

|

H | 3% | 0% | 8% | 50 |

| 30j |

|

H | 1.03±0.05 | 5.00±1.63 | 11.0±1.9 | 34 |

| 31 |

|

H | 0.063 | 0.0103 | 0.113d | 9 |

| 32 |

|

- | 0.051 | 0.58f | 0.703 ±0.035 | 35 |

| 33 |

|

C≡C-(CH2)3CH3 | 0.130e | 0.0022 | 0.0256 ±0.0032 | 36 |

| b. N6-Substituted Derivatives

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Compound | Structure | R6 = | Ki(A1)a | Ki(A2a)b | Ki(A3)c | Reference |

| 34 | A-Rib | H2N- | 29.7±6.6 | 7.34±1.12 | 16.9±1.3 | - |

| 35 |

|

- | 9.4h | 10 | 56% (10−4) | 48 |

| 36 | A-Rib | φCH2- | 0.120 | 0.285 | 0.120d | 9 |

| 37 | A-Rib |

|

0.0596 ±0.0143 | 0.0241 ±0.0018 | 0.36±0.21 | 37 |

| 38 | A-Rib |

|

0.236 ±0.005 | 0.129 ±0.039 | 0.742 ±0.312 | 45 |

| 39 | A-Rib |

|

0.042 ±0.013 | 0.293 ±0.077 | 1.48 ±0.41 | - |

| 40 |

|

φCH2- | 0.898 | 0.597 | 0.016d | 9 |

| 41 |

|

φCH2- | 62.4±6.1 | 53.6±14.6 | 0.604 ±0.143 | 21 |

| 42 |

|

|

8.61 ±2.55 | 6.22 ±2.71 | 0.720 ±0.250 | - |

| 43 |

|

|

0.054 | 0.056 | 0.0011 | 8 |

| 44 |

|

|

35.9 ± 8.3 | 28±5% | 19.5 ±4.7 | - |

Displacement of specific [3H]PIA binding, unless noted, in rat brain membranes expressed as Ki ± SEM in μM (n = 3–6), or as a single average value if from a literature report.

Displacement of specific [3H]CGS 21680 binding, unless noted, in rat striatal membranes expressed as Ki ± SEM in μM (n = 3–6), or as a single average value if from a literature report.

Displacement of specific binding of [125I]-N6-(4-amino-3-iodobenzyl)adenosine-5′-(N-methyluronamide),19 unless noted, in membranes of CHO cells stably transfected with the rat A3-cDNA expressed as Ki ± SEM in μM (n = 3–7).

Displacement of specific binding of [125I]-N6-(4-amino-3-iodophenethyl)adenosine9 in membranes of CHO cells stably transfected with the rat A3-cDNA expressed as Ki ± SEM in μM (n = 3–5).

Displacement of specific [3H]-N6-cyclohexyladenosine binding in rat brain membranes,

Displacement of specific [3H]-5′-(N-ethylcarbamoyl)adenosine binding in rat striatal membranes.

When a percentage is given, it refers to the percent displacement of radioligand binding at 10−4 M.

Displacement of specific [3H]-8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine binding in rat brain membranes.

Radioligand binding increased at 10−4 M.

DMSO stock solution made fresh before assay.

Table 2.

Characterization of Newly Synthesized Compounds

| comp no. | formula | analysis | mp (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12a | C10H14N6O | C, H, N | 214–215 |

| 12c | C18H22N6O3 | C, H, N | 200 |

| 15b | C22H29N5O3·2 H2O | C, H, N | 210–213 |

| 21 | C10H12ClN5O3S | C, H, N | 207 |

| 22 | C10H12ClN5O2S | C, H, N | 171–173 |

| 39 | C19H22N5O6·0.5 H2O | C, H, N | 176–178 |

| 41 | C19H22N6O4 | C, H | 125–130 (dec) |

| 42 | C16H17N6O5 | C, H, N | 200–203 |

| 44 | C19H21IN6O3 | C, H, N | foam |

| 46 | C10H8Cl2N4O | C, H, N | foam |

| 48 | C10H12ClN5O3 | C, H, N | 180 |

| 50 | C11H19NO5 | C, H | oil |

| β-51 | C12H19NO7 | C, H | oil |

| 52 | C16H18ClN5O6 | C, H | foam |

| 57 | C12H14ClN5O3 | C, H, N | foam |

| 58 | C17C21N3O2·H2O | C, H, N | 211–212 |

| 60 | C17H19Cl2N3 | C, H, N | 70–72 |

| 61 | C16H17Cl2N3O | C, H, N | 80 |

| 62 | C18H23Cl2N3O2 | C, H, N | 52–55 |

| 64 | C22H27ClN4O3·H2O | C, H, N | 172–175 |

| 65 | C9H13ClN4O | C, H, N | 171–173 |

| 66 | C15H16Cl2N6O | C, H, N | |

| 68 | C10H12ClN5O | C, H, N | 197–198 |

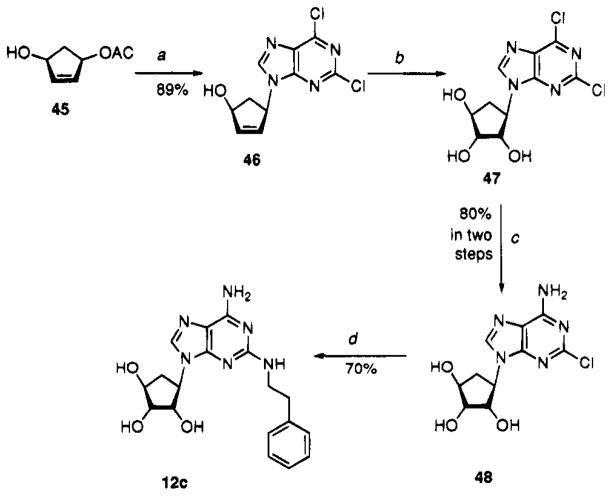

The synthesis of the carbocyclic derivative 12c is shown in Scheme 1. Using a procedure that has been employed to couple cyclopentyl acetates with nucleophiles in the presence of Pd(0) catalysis to give cis-oriented products,20 reaction of (+)-45 with 2,6-dichloropurine gave (+)-46. Standard vicinal glycolization of (+)-46 to (−)-47 was followed by exchanging the 6-chloro group with NH4OH to give 48. Heating 48 with phenylethylamine gave 12c.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Compound 12ca

aReaction conditions: (a) (i) NaH, 2,6-dichloropurine, THF, 0 °C; (ii) Pd(PPh3)4, PPh3, 45, THF, 50 °C; (b) OsO4, N-methylmorpholine N-oxide, THF/H2O; (c) NH4OH, MeOH; (d) phenylethylamine, EtOH, Et3N, reflux.

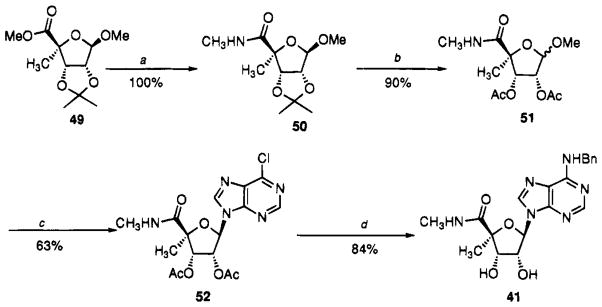

3′-C-Methyladenosine, 29a, and 4′-C-methyladenosine, 29b, were prepared according to known procedures.49,50 The 4′-C-methyl modification was combined with other substitutions known to favor A3 selectivity (Scheme 2). The methyl 4-methyl-D-ribofuranoside uronate 49 was prepared previously as an intermediate in the chemoenzymatic synthesis of methyl 4-methyl-D-ribofuranoside from cyclopentadiene.21 This methyl uronate was transformed into the corresponding nucleoside. Direct amidation proceeded smoothly with methylamine in MeOH to give the methyl amide 50, which was converted to the diacetate 51 by treatment with HCl/MeOH and acetylation with acetic anydride and pyridine. When the β-methyl glycoside 51 was subjected to Vorbrüggen conditions22 (N9-TMS-6-chloropurine, TMS-OTf, CH3CN, 50 °C), a significant amount of the α-nucleoside was initially formed even though the 2-acetyl group is β-directing. Apparently the carbonyl of the uronamide can participate as an α-director. However, upon heating to 80 °C for 6–12 h, the thermodynamically more stable β-nucleoside 52 was formed in good yield as the sole product. When the displacement of the chloro group with benzylamine was conducted in methanol at 70 °C, 1–2% of the 6-methoxy derivative contaminated the product. The use of tert-butyl alcohol instead of methanol as cosolvent suppressed this type of reaction and gave clean N-benzyl-adenosinuronamide 41.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Uronamide 41a

aReaction conditions: (a) MeNH2, MeOH; (b) (i) HCl, MeOH, (ii) Ac2O, py; (c) N-TMS-6-Cl-purine, TMS-OTf, CH3CN; (d) (i) NH3, MeOH, 0 °C, (ii) BnNH2, t-BuOH.

An N6-substituted 5′-uronamide, 42, was synthesized following the approach of Gallo-Rodriguez et al.8 via the action of furfurylmethylamine on 6-chloropurine-5′-(N-methyluronamido)riboside 2′,3′-dimethylacetal, 53. Deblocking the 2′,3′-dimethylacetal protecting group was sluggish due to the acid-sensitive nature of the furfuryl group.

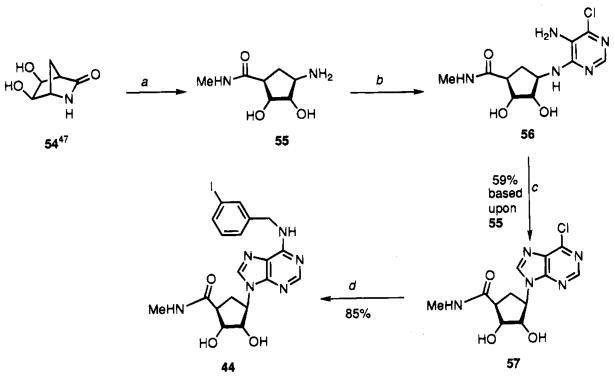

The synthesis of the carbocyclic analogue (±)-44 (Scheme 3) began by heating (±)-54 with methylamine to provide (±)-55. Reaction of 55 with 5-amino-4,6-dichloropurine gave intermediate 56. Heating 56 with methyl dimethoxyacetate followed by acidic treatment gave 57. The 6-chloro group of 57 was displaced by 3-iodobenzylamine to give 44.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of Carbocyclic IB-MECA, 44a

aReaction conditions: (a) MeNH2, THF, heat; (b) 5-amino-4,6-dichloropyrimidine, n-BuOH, Et3N; (c) (i) (MeO)2CHOAc, reflux, (ii) 1 N HCl; (d) 3-I-PhCH2NH2·HCl, Et3N, EtOH, heat.

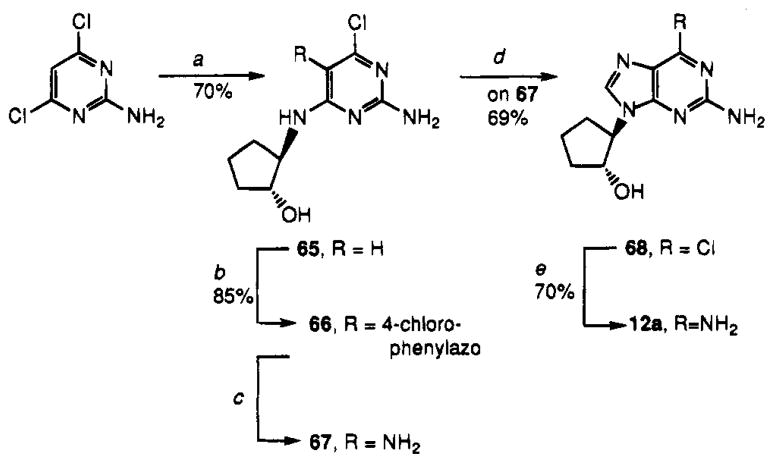

Synthesis of 12a (Scheme 4) was accomplished by employing a standard procedure for preparing carbocyclic nucleosides.56 Thus, reaction of (±)-trans-2-aminocyclopentanol with 2-amino-4,6-dichloropyrimidine yielded 65, which was subjected to C-5 diazo coupling with 4-(chlorophenyl)diazonium chloride to result in 66. Completion of the preparation of 12a followed a routine sequence:56 reduction of 66 to amine 67, ring closure with trimethyl orthoformate to prepare precursor 68, and, finally, displacement of chlorine by ammonia to give 12a.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of Compound 12aa

aReaction conditions: (a) (±trans-2-aminocyclopentanol,57 reflux in 1-BuOH; (b) (4-chlorophenyl)diazonium chloride; (c) Zn in AcOH/EtOH/H2O, reflux; (d) (MeO)3CH, concentrated HCl; (e) NH3 in MeOH.

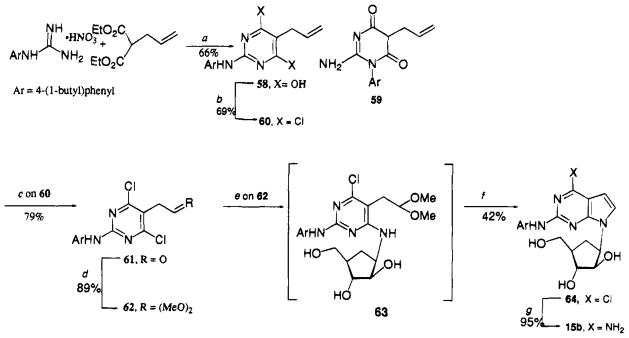

The synthesis of the carbocyclic 15b began with the reaction of N-[4-(1-butyl)phenyl]guanidine nitrate with diethyl allylmalonate to give 58 (Scheme 5) plus a small amount of the isomeric 59.53 To achive successful chlorination of 58 to 60, it was necessary to add tetraethylammonium chloride to the phosphorus oxychloride. In our hands, the standard ozonolysis approach for converting the allyl side chain of 60 to the acetaldehyde substituent of 61 could not be accomplished, apparantly due to susceptibility of the arylamino side chain to the reaction conditions. Thus, treatment of 60 with osmium tetraoxide in the presence of sodium periodate yielded 61 that was, in turn, readily converted into its dimethyl acetal derivative 62. Reaction of 62 with (±)-4α-amino-2β,3α-dihydroxy-1α-cyclopentanemethanol54 provided 63. The latter product was not fully characterized but was ring closed under acidic conditions to 64 that was then converted into the target derivative 15b by heating with methanolic ammonia.

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of 2-[[4-(1-Butyl)phenyl]amino]-ara-aristeromycin, 15ba

aReaction conditions: (a) NaOEt, EtOH; (b) POCl3, Et4NCl, N,N-diethylaniline in MeCN, 70 °C then 100 °C; (c) OsO4, NaIO4 in MeOH, acetone, H2O; (d) NH4Cl, pyridinium p-toluenesulfonate in absolute MeOH; (e) (±)-4a-amino-2β,3α-dihydroxy-1α-cyclopentanemethanol54 in n-BuOH containing ET3N, heat; (f) 2 N HCl in 1,4-dioxane; (g) NH3-MeOH, heat.

Biology

2-Chloroadenosine, 1, was much more potent than 1-deaza-2-chloroadenosine, 2, at A1 receptors and nearly equipotent at A3 receptors. Thus, the 1-deaza modification is well tolerated at rat A3 receptors. Among 2-halo analogues, the difference in affinity between 2-chloro- and 2-fluoroadenosine was most pronounced at A3 receptors, at which the 2-fluoro analogue 3 was 5.5-fold less potent. As shown previously, certain 8-position substitution, such as bromo, 4, was not well tolerated at A3 receptors, and the potencies of the 8-amino and 8-butylamino analogues23 5 and 6, respectively, were consistent with this observation. There was a slight tendency toward A2a selectivity among compounds 4–6.

Carbocyclic nucleosides have found wide application in the antiviral area.24 At adenosine receptors, there are few reports of the affinity of carbocyclic derivatives of adenosine. Francis et al.25 reported that the carbocyclic analogue of CGS 21680, an A2a selective agonist, retained that selectivity. Racemic aristeromycin was reported to have activity at A2b receptors.26 Enantiomerically pure aristeromycin, 7, isolated from Streptomyces citricolor,27 showed essentially no displacement of radioligand from A1 or A2a receptors but was weakly potent at A3 receptors. The 5′-deoxy modification of adenosine, shown previously to be tolerated at A1, A2a, and A3 receptors, was somewhat compatible with the carbocyclic modification at A2a and A3 receptors. 5′-Deoxyaristeromycin,28 9, was only 7-fold less potent than 5′-deoxyadenosine, 8, at A2a receptors and of comparable potency to aristeromycin, 7, at A3 receptors. Curiously, by deleting the 5′-methylene group of aristeromycin, as in compound 10a ((−)-5′-noraristeromycin), the potency was greatly enhanced at A1 and A2a receptors. The Ki value of 10a at A2a receptors was 0.69 μM, and there was also selectivity vs A1 (48-fold) and A3 receptors. This prompted us to synthesize an analogue which contained a 2-(2-phenylethyl)amino group, found previously to be conducive to A2 selectivity,18,25 as in compound 11. The two sets of modifications however were not additive at A2a receptors, and the hybrid compound 12c was nearly equipotent at A1 and A2a receptors. With the 2-(2-phenylethyl)amino group, there was no decrease in affinity at A1 receptors from the 5′-norcarbocyclic modification. The same carbocyclic modification nearly abolished affinity at all adenosine receptors when combined with the 3-deaza modification (cf. 13 and 14). Didehydrodideoxy and dideoxy analogues of carbocyclic nucleosides 10b24b and 12a were inactive at A1, and they were marginally active at A2a and A3 receptors. Dideoxy-3-oxa derivative 12b52 was nearly inactive at A1 receptors, but it showed very weak binding affinity to A2a and A3 receptors. 3-Deazaadenosine, 13, itself, was only weakly potent at the three subtypes. Similarly 7-deazaadenosine, 15a, was only marginally potent, and in combination with the 5′- and carbocyclic modifications was essentially inactive in binding. 7-Deaza-2-(phenylbutyl)-ara-aristeromycin, 15b, was only weakly potent at the three sybtypes, and there was also selectivity for A3 vs A1 and A2a receptors.

β-L-Adenosine, compound 17, was shown to bind weakly to A1 receptors.9 Curiously, compound 18 ((+)-5′-noraristeromycin), the L-analogue of compound 10a, showed considerable potency at A2a (>A1 and A3) receptors and was 21-fold selective for A2a vs A1 receptors. The 6′-thio modification of adenosine29 was well tolerated in receptor binding. (The position corresponding to the carbohydrate 4′-oxygen is here numbered 6′, as in carbocyclic derivatives.) Compound 19 was 3.2-fold more potent than the corresponding oxygen analogue 1 at A2a receptors, while at A1 receptors affinity diminished by 32-fold. Compounds 1 and 19 were of similar potency at A3 receptors. Thus, this thio modification, which provided 15-fold selectivity in 19, may serve as a means of increasing A2a selectivity in general. The 6′-thio and 2-chloro modifications of the arabinoside resulted in a substantial gain in potency at all three subtypes (cf. 21 and 20). Surprisingly, even the 2′-deoxy-6′-thio-L-xylofuranoside analogue 22 had potency comparable to 21 at A1 and A2a receptors.

Compounds 23–29 contain 2′- and 3′-ribose modifications. The 2′-deoxy-2′-fluoro modification of 2-chloroadenosine,30 23, had Ki values at A1 and A2a receptors in the micromolar range and was 2 orders of magnitude less potent at A3 receptors. The degree of tolerance of the 2′-fluoro substituent (cf. compound 1) was greatest at A2a receptors. The corresponding 2′-deoxy analogue 2546 was less potent than 23 at A1 and A2a receptors by factors of 11 and 23. Thus at the 2′-position substituents in the order OH > F > H are favored in receptor binding at all three subtypes. For purposes of this comparison, it was essential to have the potency-enhancing 2-chloro substituent in order to obtain measurable Ki values (cf. compound 24, which was nearly inactive).

The 1-deaza modification of adenosine was already shown to be tolerated in receptor binding (see compound 2).42 Deletion of the 2′-hydroxy group of 2, resulting in compound 26, was poorly tolerated in receptor binding.31,32 Only at A1 receptors was there a measurable Ki value (29 μM). Deletion of both 2′- and 3′-hydroxyl groups, as in compound 27, resulted in a 3-fold loss of potency at A1 receptors (vs 26) and an apparent slight gain in affinity at A2a receptors.

The 2′-methoxy derivative of the A1-selective agonist N6-cyclohexyladenosine (CHA) has been reported by Wagner et al.33 to have substantial in vivo activity, perhaps as a prodrug of CHA. We have evaluated methoxy derivatives of adenosine at the three subtypes and found the 3′-derivative 28a to be nonselective and of very weak affinity and the 2′-derivative 28b to be inactive. The inclusion of methyl groups in place of hydrogen in the ribose ring was examined in compounds 29a,b. The 3′-methyl analogue 29a bound weakly with A1 selectivity, while the 4′-methyl analogue 29b was virtually inactive.

Limited modification of the 5′-position of adenosine is tolerated at adenosine receptors. NECA, 31, has long been known as a highly potent, nonselective agonist.1 A cytotoxic aminosulfonate derivative 3034 was much less potent than NECA, with Ki values in the 1–10 μM range. 1-Deaza-NECA, 31, as reported previously,35 has substantial activity at A1 receptors, and at A2a and A3 receptors, the potencies vs those of NECA are diminished by factors of 56- and 6-fold. Thus, at A2a and A3 receptors, the 1-deaza substitution is tolerated better in the 2-chloro series (cf. compounds 1 and 2), while at A1 receptors, the 1-deaza modification is tolerated better in the uronamide series. The addition of the 2-hexynyl group to NECA, resulting in the A2a selective agonist compound 33 (HE-NECA), previously studied in platelets and on the coronary artery,36 enhanced the A3 potency. Thus, the order of selectivity of HE-NECA (with Ki values in nM) is A2a (2.2) > A3 (25.6) > A1 (130).

Numerous modifications of the N6-position of adenosine have been introduced and shown to result generally, but not exclusively, in A1 selectivity.1 Table 1b shows a comparison of affinities of a variety of N6-substituted analogues. 6-Hydrazinopurine riboside, 34, had Ki values in the 10−5 M range and was nearly nonselective for A1/A2a/A3 receptors. 1-Deaza-6-(hydroxylamino)-purine riboside, 35, also bound weakly but was 1 order of magnitude selective for A1 and A2a vs A3 receptors. The affinity of adenosine, itself, for comparison with these compounds is difficult to evaluate, due to the presence of adenosine deaminase in the medium.

At A3 receptors, N6-benzyl substituents, as in 36, have been shown to be favored. Several other known N6-arylmethylene analogues were studied. Metrifudil, 37, a potent hypotensive agent, which had entered human trials in the early 1970’s,37 was found to be 2.5-fold selective for rat A2a vs A1 receptors and 15-fold selective for rat A2a vs A3 receptors. The affinity of 37 was enhanced 12-fold and diminished 3-fold at A2a and A3 receptors, respectively, by the presence of the 2-methyl group on the benzyl ring. (−)-Kinetin riboside,45 38, was also slightly selective for A2a receptors, although 5-fold less potent than metrifudil. An N6-bicyclic methylene analogue, 39, was slightly selective for A1 receptors.

N6-Benzyl-NECA was the first A3 selective agonist identified,9 although it was only 14-fold selective verses either A1 or A2a receptors. The corresponding N-methyl analogue 40 had enhanced potency and selectivity.8 A 4′-methyl analogue, 41, displayed even greater selectivity, although it was 38-fold less potent than 40 at A3 receptors. Compound 41 was 100- and 89-fold selective for A3 vs A1 and A2a receptors, respectively. Curiously, the affinity of 41 is in contrast to the inactivity of the simple 4′-methyladenosine derivative 29b. The combination of the 5′-N-methyluronamide group with the N9-furfuryl group of kinetin riboside resulted in an A3-selective compound, 42, of micromolar affinity.

A selective A3 agonist that has been studied in vivo is IB-MECA, 43.10,11 The carbocyclic analogue of IB-MECA, 44, was weakly binding and more potent at A1 and A3 vs A2a receptors. IB-MECA, 43, was 18 000-fold more potent than this carbocyclic analogue at A3 receptors.

Since many of the adenosine derivatives diverge greatly in structure from adenosine itself, it was not to be assumed that all of the compounds found to bind to the receptors were agonists. Previously, removal of the 2′ and 3′-hydroxyl groups of N6-substituted adenosine derivatives was shown to result in partial agonist or antagonist properties.15,38 Therefore we tested selected analogues for A1 agonist efficacy using a straight forward binding method. GTP shifts in the displacement curves for agonist verses antagonist have been shown to be indicative of agonist.38 Thus, we examined the ability of selected analogues to displace the antagonist radioligand [3H]CPX and the degree of shift of the displacement curve in the presence of 1 mM GTP, and the results are given in Table 3. For agonists a typical shift in the Ki value is > 2-fold. Full agonists, such as (R)-PIA and CPA, under the same conditions give shifts of 5.5 and 6.0, respectively. For pure antagonists, no shift or only a very small shift is expected. For example, the value for the A1 adenosine antagonist 9-methyladenine14 is 1.2. Compound 22 appears to be in the antagonist range, which is consistent with its highly unnatural carbohydrate moiety. Compounds 21 and 25 are predicted to be partial agonists at A1 receptors. The 2′-deoxy 2′-fluoro analogue, compound 23, is likely a full agonist.

Table 3.

Displacement of the Antagonist Radioligand [3H]CPX and the Degree of Shift of the Displacement Curve in the Presence of 1 mM GTP

| compd |

Ki value (μM) or % displacement at 10−4 Ma

|

GTP Shiftb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 (−GTP) | A1 (+GTP) | ||

| 10a | 40 | nd | |

| 12c | 35 | nd | |

| 18 | 36 | nd | |

| 21 | 13 | 30 | 2.3 |

| 22 | 8.4 | 12 | 1.4 |

| 23 | 1.7 | 8.3 | 4.9 |

| 25 | 12 | 21 | 1.7 |

| 26 | 31 | nd | |

| 27 | 37 | nd | |

| 28b | 12 | nd | |

Average of two determinations.

nd = not determined.

Ratio of Ki values in the presence and absence of GTP.

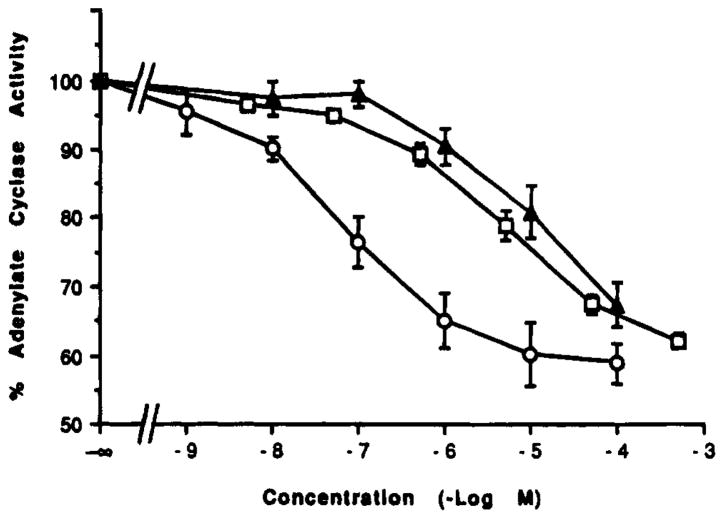

Compound 41, which was A3 selective, was tested in a functional assay at rat A3 receptors. Compound 41 inhibited adenylate cyclase (Figure 1), using membranes from CHO cells stably transfected with rat A3 receptors. We previously demonstrated that compounds with high affinity in binding were very active in this assay of A3-mediated inhibition of adenylate cyclase.39 Compound 41 appeared to be a full agonist, with an inhibition of forskolin-stimulated adenylate cyclase of 32.7% ± 3.2% at 10−4 M and an IC50 value of 10 μM. (based on a maximal inhibition of 40%). Thus it was less potent than NECA, 31, which had an IC50 value of 5.6 μM, but was more selective for A3 receptors.

Figure 1.

Inhibition of adenylate cyclase in membranes from CHO cells stably transfected with rat A3 receptors. The assay was carried out as described in the Experimental Section in the presence of 1 mM forskolin. Each data point is shown as the mean ± SEM for four determinations. Adenosine derivatives were (number of separate experiments in parentheses) triangles, 41, N6-benzyl-4′-methyladenosine-5′-(N-methyluronamide); circles, 2-chloro-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)adenosine-5′-(N-methyluronamide); and squares, NECA. IC50 values were Cl-IB-MECA, 66.8 ± 9.0 nM; NECA, 3 μM; and 41, 10 μM.

Discussion

The results of this study imply the existence of receptor binding sites for adenosine with very strict structural requirements. 1-Deaza modification of adenosine derivatives is well tolerated at A1, A2a, and A3 receptors. The marked difference in affinity between 2-chloro- and 2-fluoroadenosine at rat A3 receptor suggests preference for hydrophobic interaction near the 2-position of the purine ring. Substitution at the 8-position of adenosine resulted in agonists having decreased affinity for all the receptor subtypes.

Carbocyclic nucleosides were in general weakly A2a selective ligands and showed poor affinity for A3 receptors. Therefore it can be assumed that the 6′-oxygen of the ribose moiety is beneficial for binding to A1 and A3 receptors. Interestingly deletion of the 5′-methylene group of carbocyclic nucleosides (5′-noraristeromycin derivatives) resulted in enhanced affinity at A1 and A2a receptors. However, substitution at the 2-position of the purine ring of carbocyclic nucleosides did not enhance their affinity at A2a receptors.

Replacement of the 6′-oxygen by sulfur was well tolerated at all the adenosine receptors. Adenine-β-D-arabinofuranoside, 20, was weakly potent at all the receptor subtypes.9 Curiously, the 2′-deoxyxylose modification combined with the 6′-thio modification resulted in enhanced binding at A1 and A2a receptors and a moderate affinity for A3 receptors. In general 6′-thio and carbocyclic modifications of agonists were more suitable for increasing A2a selectivity.

Various 2′-deoxy- and 2′,3′-dideoxyadenosine analogues were inactive in binding at rat A3 receptors, but they showed considerable binding affinity at A1 and A2a receptors. Compounds 21 and 25 were putative partial agonists. 2-Chloro-2′-deoxy-1-deazaadenosine, 26, was active, possibly as a partial agonist at A1 receptors only. Recently Sipe et al.40 reported that therapeutic use of 2-chloro-2′-deoxyadenosine, 25, an antileukemic drug, slowed the progression of multiple sclerosis.

β-L-Adenosine, 17, bounds appreciably A1 receptors only.9 However, β-L-5′-noraristeromycin, 18, was an A2a selective ligand. Surprisingly, when 6′-thio and 2′-deoxyxylo modifications were applied to the β-L-nucleoside enantiomer, the resultant nucleoside, 22, behaved as an antagonist at A1 receptors.

The 2-chloro 1-deaza modification was well tolerated at A2a and A3 receptors. Combination of the 1-deaza modification with a 5′-uronamide group leads to A1 selectivity. Replacement of the 6-amino group by hydrazine or hydroxylamine was tolerated. Substitution at N6 by benzyl, furfuryl, and benzopyryl groups was well tolerated at A1, A2a, and A3 receptors. N6-Substitution modification combined with 5′-uronamide derivatives increased A3 selectivity. Substitution of 4′-hydrogen by a methyl group (compound 41) maintained agonist activity at A3 receptors and selectivity. This methyl group is designed to diminish metabolic hydrolysis of the amide group in vivo to provide a longer biological half-life. The 5′-uronamide N6-benzyl-modified carbocyclic nucleoside 44 displaced binding at A1 and A3 receptors. It is to be noted that the inactivity of a singly modified derivative of adenosine, e.g., 29b, does not preclude activity in multiple modified versions of the same, e.g., 41.

Most of the compounds in this study are not substrates for adenosine deaminase. Those analogues having the N6-alkyl, 5′-carboxamido, 2-chloro, 3- and 7-deaza, and 8-position modifications, and the carbocyclic “nor” analogues (e.g., 9, 10a, 12c, and 16),24a are expected to be stable to adenosine deaminase. It is possible that some of the compounds (20, 24, 28, and 29) may be substrates for adenosine deaminase and that any residual deaminase present during the binding assay may raise the observed Ki value. Compound 7 is reported to be an adenosine deaminase substrate.51 Compound 35 is an inhibitor of adenosine deaminase in the micromolar range.48

Conclusions

The most significant new compound, N6-benzyl-4′-methyladenosine-5′-(N-methyluronamide), 41, was identified as an A3 selective agonist, and it displayed a Ki value of 604 nM at A3 receptors and was 103- and 88-fold selective vs A1 and A2a receptors, respectively. Compounds 1,3, and 25 were A1 selective. Compounds 17,35, and 39 were somewhat selective for A1 receptors. Compounds 4, 5, 22, 37, 38, and 39 were identified as slightly A2a selective ligands. The moderately A2a selective agonists were 9, 11, 18, 19, and 33. On the basis of intermediate GTP shifts in binding versus an antagonist radioligand, 2-chloro-2′-deoxyadenosine, 25, and 2-chloroadenine-9-(β-D-6′-thioarabinoside), 21, are putative partial agonists at A1 receptors, with Ki values of 7.4 and 5.4 μM, respectively. Compound 22 was identified as an A1 antagonist from this search for new leads for ligand selectivity at adenosine receptors. We are synthesizing derivatives of 22 to enhance its potency as antagonists at adenosine receptors subtypes.

Although the corresponding simple 4′-methyladenosine derivative 29b was inactive at adenosine receptors, compound 41, containing two other modifications as well, was an A3 selective, full agonist. Thus, this study emphasizes that inactivity or low binding affinity of an adenosine derivative does not preclude activity in optimally modified derivatives of the same ligand.

Experimental Section

All chemicals were purchased from Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI) unless otherwise noted. Compounds 28b and 34 were the gift of the Drug Synthesis & Chemistry Branch, Developmental Therapeutics Program, Division of Cancer Treatment, NCI. Compounds 1, 7, 31, and 38 were purchased from Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, MO. Cylinders of ammonia and methylamine were obtained from Union Carbide and Matheson, respectively. Anhydrous methyl alcohol and tert-butyl alcohol were used from freshly opened bottles as received. Column chromatography was carried out with silica gel 60 from EM Science (230–400 mesh). 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded in the solvent and field strength noted. Chemical shifts are reported relative to the solvent standard. Elemental analyses were performed by Midwest Microlab, Indianapolis, IN, and M-H-W Laboratories, Phoenix, AZ.

(±)-(1α,2β)-2-(2,6-Diamino-9H-purin-9-yl)cyclopentan-1-ol (12a)

Compound 68 (220 mg, 0.87 mmol) in MeOH (30 mL) saturated with anhydrous NH3 was heated in a sealed cylinder at 100 °C for 12 h. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the residue purified by column chromatography (CH2Cl2:MeOH, 9:1) to give 12a as white crystals following recrystallization from MeOH (140 mg, 69.7%): mp 214–215 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.5–2.2 (m, 6 H, 3 × CH2 of cyclopentyl), 4.20 (m, 2 H, H-1 and H-2 of cyclopentyl), 5.79 (s, 2 H, NH2), 6.69 (s, 2 H, NH2), 7.74 (s, 1 H, H-8 of purine); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 19.90, 28.97, 31.99, 62.15, 74.93, 113.57, 136.30, 151.88, 156.04, 159.77.

(1S,2R,3S,4R)-4-[6-Amino-2-[(phenylethyl)amino]-9H-purin-9-yl]cyclopentane-1,2,3-triol (12c)

To a suspension of 48 (300 mg, 1.05 mmol) in absolute EtOH (10 mL) was added phenylethylamine (300 mg, 2.45 mmol). This mixture was heated at 90 °C for 3 days. The solvent was removed by rotary evaporation, and the residue was subjected to column chromatography on silica gel (eluent CH2Cl2–MeOH) to give 12c (272 mg, 70%) as a yellow solid: mp 200 °C dec; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.77–1.90 (m, 1 H, H-5′), 2.50–2.60 (m, 1 H, H-5′), 2.8 (m, 4 H, 2 × CH2), 3.75 (m, 1 H, H-2′), 3.89 (m, 1 H, H-1′), 4.40–4.52 (m, 1 H, H-3′), 4.62–4.81 (m, 1 H, H-4′), 4.87 (d, 1 H, J = 3.6 Hz, OH), 5.01 (d, 1 H, J = 6.6 Hz, OH), 5.36 (d, 1 H, J = 4.8 Hz, OH), 7.22 (s, 2 H, NH2), 7.48 (m, 5 H, Ph), 8.48 (s, 1 H, H-8).

(±)-1α,2β,3β,5β)-3-[2-[[4-(1-Butyl)phenyl]amino]-4-amino-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-7-yl]-5-(hydroxymethyl)-1,2-cyclopentanediol (15b)

Into an ice-cooled solution of 64 (500 mg, 1.16 mmol) in dry MeOH (50 mL) was bubbled anydrous NH3 until a saturated solution was obtained. The mixture was transfered to a sealed tube and heated at 125 °C for 55 h. After cooling to 0 °C, the sealed tube was opened and the volatiles were removed by evaporation in vauo. The residual solid was chromatographed on silica gel (CH2-Cl2–MeOH, 9:1). The product-containing fractions were evaporated to dryness, and the residue was rechromatographed on 5 g of Norit-A (CH2Cl2–MeOH, 6:4) to give pure 15b (454 mg, 95%): mp 210–213 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 0.89 (t, 3 H, Me), 1.42 (m, 5 H, 2 × CH2 and H-4′), 1.9 (m, 2 H, H-4′ and H-5′), 2.5 (m, 2 H, CH2), 3.0–4.1 (m, 7 H, CH2OH, H-1′, H-2′, H-3′, and 2 × OH), 5.0 (m, 1 H, OH), 6.4 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1 H, H-7), 7.0 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2 H, ArH). 7.4 (br, 3 H, H-8 and NH2), 7.7 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2 H, ArH), 8.8 (br, 1 H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 13.76, 21.67, 30.06, 33.23, 34.13, 46.38, 55.15, 63.38, 77.14, 78.07, 100.38, 101.09, 118.43, 120.59, 128.56, 135.65, 136.89, 147.41, 148.82, 158.35.

N6-(Benzodioxanylmethy)adenosine Hemihydrate (39)

6-Chloropurine riboside (200 mg, 0.70 mmol) was refluxed in 10 mL of ethanol with 162 mg (0.77 mmol) of racemic benzdioxan-2-methylamine and 2 g (2.1 mmol) of triethylamine solution (5.3 g of triethylamine in 50 g of ethanol) for 18 h. After 48 h at −20 °C, a white crystalline product was formed that was collected and dried. Further workup afforded a second crop of the product: total yield 180 mg (62%); mp 176–178 °C; MS (CI) MH+ = 416.

1-[6-(Benzylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl]-1-deoxy-N,4-dimethyl-β-D-ribofuranosiduronamide (41)

The diacetyl nucleoside 52 (195 mg, 0.474 mmol) was selectively deacylated by treatment with a methanolic solution of NH3 at 0 °C for 10 min. The solution was evaporated to dryness, and to the residue was added a 1:1 solution of t-BuOH and benzylamine (4 mL). This solution was heated at 70 °C for 16 h and concentrated under reduced pressure (0.1 Torr, 40 °C). Chromatography of the residue on silica gel (gradient 30:1–10:1 CH2Cl2:MeOH) gave 159 mg (84%) of N-benzyladenine nucleoside 41 as a white solid: [α]23D–25.7° (c 1.02, CH3OH); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD, prior H–D exchange) δ 8.29 (s, 1 H), 8.13 (s, 1 H), 7.35 (d, 2 H, J = 7.0 Hz), 7.28 (t, 2 H, J = 7.5 Hz), 7.21 (t, 1 H, J = 7.5 Hz), 5.97 (d, 1 H, J = 8.5 Hz), 4.83 (dd, 1H, J = 8.5, 5.0 Hz), 4.78 (br s, 2 H), 4.30 (d, 1 H, J = 5.0 Hz), 2.82 (s, 3 H), 1.50 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CD3OD) δ 174.98, 154.73, 152.48, 148.33, 140.77, 138.78, 128.13, 127.10, 126.81, 120.10, 88.16, 87.74, 73.75, 71.75, 43.62, 24.90, 18.79.

1-[6-(Furfurylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl]-1-deoxy-N-methyl-β-D-ribofuranosiduronamide (42)

To a solution of 2′,3′-isopropylidene-1-(6-chloro-9H-purin-9-yl)-1-deoxy-N-methyl-β-D-ribofuranosiduronamide8 (50 mg, 0.16 mmol) in absolute EtOH (5 mL) was added furfurylamine (20 mg, 0.21 mmol). This mixture was heated at 90 °C for 20 h. After cooling to room temperature, solvent was removed by rotary evaporation and the residue was dissolved in 0.5 N HCl and heated at 60 °C for 1 h. After cooling to 0 °C in an ice bath, the reaction mixture was neutralized with concentrated NH4OH and evaporated to dryness. The residue was purified by preparative thin-layer chromatography on silica gel to give 42 (21 mg, 40%) as white solid: 1H NMR (DMSO- d6) δ 3.32 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 3 H, Me), 4.12 (m, 1 H, H-3′), 4.33 (s, 1 H, H-4′), 4.60 (dd, J = 4.6, J = 4.3 Hz, 1 H, H-2′), 4.70 (br s, 2 H, N6-CH2-), 5.53 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 1 H, OH-2′), 5.56 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1 H, H-1′), 5.71 (d, J = 4.1 Hz, 1 H, OH-3′), 5.60 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1 H, H-1′), 7.3 (m, 3 H), 8.42 (s, 1 H, H-8), 8.56 (br s, 1 H, H-Ne), 8.55 (br s, 1 H, NH-Me).

(±)-9-[2α,3α-Dihydroxy-4β-(N-methylcarbamoyl)cyclopent-1β-yl)]-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)adenine (44)

To a solution of 57 (100 mg, 0.32 mmol) in absolute EtOH (10 mL) was added 3-iodobenzylamine hydrochloride (90 mg, 0.34 mmol), and the resulting mixture was heated at 90 °C for 24 h, under a nitrogen atmosphere. The solvent was removed by evaporation in vacuo, and the residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (eluent CH2Cl2–MeOH, 10:0.5) to give 44 (140 mg, 85%) as colorless foam: 1H NMR (DMSO- d6) δ 2.71 (s, 2 H, CH2), 3.31 (m, 1 H, H-1′), 3.42 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 3 H, Me), 4.32 (m, 1 H, H-3′), 4.35 (s, 1 H, H-4′), 4.70 (s, 2 H, CH2-Ph), 4.74 (dd, J = 4.0, J = 4.3 Hz, 1 H, H-2′), 5.45 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 1 H, OH-2′), 5.60 (d, J = 4.1 Hz, 1 H, OH-3′), 5.60 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1 H, H-1′), 7.13 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 1 H), 7.40 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1 H), 7.60 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1 H), 8.21 (s, 1 H, H-8), 8.50 (br s, 1 HN6), 8.60 (br s, 1 H, NH-Me).

(1R,4S)-4-(2,6-Dichloro-9H-purin-9-yl)cyclopent-2-en-1-ol (46)

To a solution of 2,6-dichloropurine (2 g, 10.64 mmol) in dry DMSO (25 mL) was added sodium hydride (60% suspension in mineral oil, 0.42 g, 10.64 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at the room temperature for 30 min followed by the addition of tetrakis(triphenylphosphine)-palladium (0.5 g, 0.22 mmol), triphenylphosphine (0.25 g, 0.95 mmol), and a solution of (+)-4520 (1.66 g, 11.70 mmol) in dry THF (25 mL). This mixture was stirred at 50 °C for 20 h. The volatiles were removed by rotary evaporation in vacuo at 50 °C. The residue was slurried in CH2Cl2 (50 mL) and filtered to remove insoluble solids. The filtrate that resulted was washed with brine (2 × 50 mL), dried (MgSO4), and evaporated to dryness. The residual oil was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel by eluting first with AcOEt to remove the nonpolar impurities and then with AcOEt–MeOH (9:1). The product containing fractions were evaporated to dryness to give 46 (3.55 g, 89%) as a colorless foam: 1H NMR (DMSO- d6) δ 1.62–2.7 (m, 2 H, H-5′), 3.26 (m, 3 H, OH), 3.65 (m, 1 H, H-1′), 4.58 (m, 3 H, H-2′, H-3′, H-4′), 8.34 (m, 1 H, H-8).

(1S,2R,3S,4R)-4-(6-Amino-2-chloro-9H-purin-9-yl)cyclopentane-1,2,3-triol (48)]

To a solution of 46 (1 g, 3.70 mmol) in THF-H2O (10:1, 50 mL) was added a 60% aqueous solution of N-methylmorpholine N-oxide (1.2 mL, 1.14 mmol) and then osmium tetraoxide (30 mg). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. The solvent was removed by rotary evaporation, and the residue was coevaporated with EtOH (3 × 50 mL) to give a gummy material. This residue was dissolved in MeOH presaturated with anhydrous ammonia (50 mL) and stirred in a sealed tube at room temperature for 5 days. Volatiles were removed by rotary evaporation, and the residue was subjected to column chromatography on silica gel (eluent MeOH–CH2Cl2, 9:1) to give 48 (800 mg, 80%) as a white solid: mp 180 °C dec; 1H NMR (DMSO- d6) δ 1.77–190 (m, 1 H, H-5′), 2.50 (m, 1 H, H-5′) 3.75 (m, 1 H, H-2′), 3.89 (m, 1 H, H-1′), 4.40–4.52 (m, 1 H, H-3′), 4.62–4.81 (m, 1 H, H-4′), 4.87 (d, 1 H, J = 3.6 Hz, OH), 5.01 (d, 1 H, J = 6.6 Hz, OH), 5.36 (d, 1 H, J = 4.8 Hz, OH), 7.22 (s, 2 H, NH2), 8.11 (s, 1 H, H-8).

Methyl 2,3-O-Isopropylidene-N,4-dimethyl-β-D-ribofuranosiduronamide (50)

A solution of methyl ester 4921 (502 mg, 2.04 mmol) in MeOH (30 mL) was saturated with gaseous methylamine and stirred until TLC (2:1 hexane: EtOAc) showed the reaction was complete. The solution was concentrated and the residue chromatographed on silica gel (1.5:1 hexane:EtOAc) to give 502 mg (100%) of 50 as a clear oil: [α]23D–45.0° (c 1.05, CH2Cl2); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.56 (br s, 1 H), 5.10 (d, 1 H, J = 5.9 Hz), 4.93 (s, 1 H), 4.51 (d, 1 H, J = 5.9 Hz), 3.39 (s, 3 H), 2.79 (d, 3 H, J = 5.0 Hz), 1.47 (s, 3 H), 1.44 (s, 3 H), 1.30 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 174.55, 112.53, 110.25, 89.33, 85.15, 82.35, 55.96, 26.16, 25.98, 24.76, 20.96.

Methyl 2,3-O-Diacetyl-N,4-dimethyl-β-D-ribofuranosiduronamide (51)

To a solution of acetonide 50 (502 mg, 2.04 mmol) in MeOH (60 mL) was added concentrated HCl (0.1 mL). The solution was stirred for 18 h and then concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was chromatographed on silica gel (gradient EtOAc–30% MeOH in EtOAc) to give 105 mg (21%) of starting acetonide and 310 mg of diols as a mixture of glycosides which were acetylated with Ac2O (0.48 mL) and pyridine (0.85 mL) in CH2Cl2 (30 mL) containing a catalytic amount of DMAP. Toluene (10 mL) was added, and the solution was concentrated to dryness. The residue was chromatographed on silica gel (1:1 hexane:EtOAc) to give 380 mg (64%) of β-51 and 40 mg (7%) of α-51 (81% and 8.5% yields, respectively, based on recovered acetonide). β-51: oil; [α]23D –27.5° (c 1.2, CH2Cl2); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.77 (br s, 1 H), 5.54 (d, 1 H, J = 4.8 Hz), 5.19 (dd, 1 H, J = 3.2, 4.8 Hz), 5.01 (d, 1 H, J = 3.2 Hz), 3.48 (s, 3 H), 2.82 (d, 3 H, J = 5.0 Hz), 2.10 (s, 3 H), 2.05 (s, 3 H), 1.46 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 173.26, 169.19 (2), 106.54, 85.69, 74.71, 73.75, 56.87, 26.11, 20.56 (2), 20.45. Anal. Calcd for C12H19NO7: C, 49.82; H, 6.62. Found: C, 49.75; H, 6.52. α-51: mp 112–113 °C (CH2Cl2/hexane); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.71 (br s, 1 H), 5.64 (d, 1 H, J = 6.3 Hz), 5.12 (d, 1 H, J = 4.8 Hz), 4.94 (dd, 1 H, J = 6.3, 4.8 Hz), 3.42 (s, 3 H), 2.81 (d, 3 H, J = 5.0 Hz), 2.16 (s, 3 H), 2.08 (s, 3 H), 1.48 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 172.92, 169.81, 169.58, 101.35, 85.59, 72.08, 70.78, 55.83, 26.08, 21.14, 20.65, 20.45.

2,3-O-Diacetyl-1-(6-chloro-9H-purin-9-yl)-1-deoxy-N,4-dimethyl-β-D-ribofuranosiduronamide (52)

A suspension of 6-chloropurine (590 mg, 3.82 mmol) in hexamethyldisilazane (6 mL) was heated to 100 °C until dissolution was complete, ca. 1 h. Toluene (2 mL) was added, and the solution was concentrated under an inert atmosphere. To remove final traces of HMDS, toluene (2 × 4 mL) was again added and the solution was concentrated in a similar manner. To the silylated 6-chloropurine in dry CH3CN (3 mL) was added 307 mg (1.05 mmol) of β-51 (dried by azeotropic distillation with toluene under reduced pressure) in dry CH3CN (5 mL) and trimethylsilyl trifluoromethanesulfonate (0.75 mL). This solution was heated to reflux for 12 h. The two initial nucleoside products detected by TLC gave way to a single thermodynamic product during this time. The reaction mixture was cooled, the reaction quenched by the addition of saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (1 mL), and the mixture partitioned between CH2-Cl2 (40 mL) and H2O (10 mL). The aqueous layer was extracted with CH2Cl2 (2 × 40 mL). The combined organics were dried (MgSO4), filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. Column chromatography on silica gel (1:2 CH2Cl2: EtOAc) gave 270 mg (63%) of 6-Cl-purine nucleoside 52 as a faint yellow foam: [α]23D 2.48° (c 1.45, CH2Cl2); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.68 (s, 1 H), 8.27 (s, 1 H), 7.61 (br q, 1 H, J = 4.9 Hz), 6.15 (d, 1 H, J = 7.5 Hz), 6.00 (dd, 1 H, J = 7.5, 5.0 Hz), 5.82 (d, 1 H, J = 5.0 Hz), 2.77 (d, 3 H, J = 4.9 Hz), 2.13 (s, 3 H), 1.88 (s, 3 H), 1.49 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 171.13, 168.78 (2), 151.80, 151.56, 150.96, 144.67, 133.39, 86.80, 86.07, 73.03, 71.15, 25.99, 20.20, 19.96, 19.75.

(±)-9-[2α,3α-Dihydroxy-4β-(N-methylcarbamoyl)cyclopent-1β-yl)]-6-chloropurine (57)

To a solution of compound 54 (1 g, 7.04 mmol, prepared according to the procedure reported by Cermak and Vince47) in dry MeOH (20 mL) was bubbled anhydrous methylamine for 10 min. The resulting solution was heated at 90 °C in a sealed tube for 20 h. After cooling to room temperature, solvent was removed by rotary evaporation in vacuo and the residue was used in the next step without further characterization. To this residue were added 5-amino-4,6-dichloropyrimidine (1.00 g, 6.13 mmol), triethylamine (2 mL), and n-BuOH (20 mL). The resulting mixture was heated at 100 °C, under an N2 atmosphere, for 24 h. Volatiles were evaporated in vacuo, and the residue was dissolved in methyl diethoxyacetate (10 mL). This mixture was heated at 100 °C for 2 h and then evaporated to dryness. The residue was dissolved in 1 N HCl (10 mL) and stirred at room temperature for 3 h. The ice-cold reaction mixture was neutralized with concentrated NH4OH and evaporated to dryness. The residue was subjected to column chromatography on silica gel (eluent CH2Cl2–MeOH, 9.5:0.5) to give 57 (1.3 g, 59% yield based upon 54) as a yellow foam: 1H NMR (DMSO- d6) δ 2.75 (s, 2 H, CH2), 3.33 (m, 1 H, H-1′), 3.40 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 3 H, Me), 4.22 (m, 1 H, H-3′), 4.33 (s, 1 H, H-4′), 4.75 (dd, J = 4.0, J = 4.3 Hz, 1 H, H-2′), 5.45 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 1 H, OH-2′), 5.60 (d, J = 4.1 Hz, 1 H, OH-3′), 5.60 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1 H, H-1′), 8.21 (s, 1 H, H-8), 8.50 (br s, 2 H, HN6), 8.60 (br s, 1 H, NH-Me).

5-Allyl-2-[[4-(1-butyl)phenyl]amino]-4,6-dihydroxypyrimidine (58)

N-[4-(1-Butyl)phenyl]guanidine nitrate56 (16 g, 62.99 mmol) was added to cold NaOEt in EtOH (250 mL prepared by dissolving 25 g of Na in 250 mL of absolute EtOH). This mixture was stirred at 5 °C for 10 min before diethyl allylmalonate (12.59 g, 62.95 mmol; Aldrich Chemical Co.) was added. The reaction mixture was then refluxed for 3 h. Concentrated HCl (40 mL) was added to the cold reaction mixture, which was allowed to stand for several hours. The crude product and inorganic salts precipitated. After filtration and washing the crude mixture with water and recrystallization of this material using EtOH, 12.5 g (66%) of pure 58 was obtained: mp 211–212 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO- d6) δ 0.81 (t, 3 H, CH3), 1.39 (m, 4 H, 2 × CH2), 2.44 (t, 2 H, CH2), 2.90 (d of t, 2 H, CH2), 3.03 (br, 1 H, OH), 4.86 (m, 2 H, CH2), 5.61 (m, 1 H, CH), 7.09 (d, 2 H of C6H5), 7.62 (d, 2 H of C6H5), 8.57 (s, 1 H, side chain NH), 10.50 (br, 1 H, ring OH/NH); 13C NMR (DMSO- d6) δ 13.77, 21.73, 26.39, 33.32, 34.25, 90.75, 113.66, 119.89, 128.51, 136.20, 136.80, 149.58, 165.08.

5-Allyl-2-[[4-(1-butyl)phenyl]amino]-4,6-dichloropyridimidine (60)

To a suspension of dried 58 (10 g, 33.44 mmol) in dry acetonitrile (150 mL) was added tetraethylammonium chloride (dried over P2O5) (2 g, 17.09 mmol) followed by N,N-diethylaniline (2.5 mL) and phosphorus oxychloride (30 mL). The reaction mixture was kept in an oil bath preheated at 70 °C for 2 h. An additional amount of phosphorus oxychloride (20 mL), containing N,N-diethylaniline (1.5 mL), was added, and the temperature was raised to 100 °C. After 2 h, the volatiles were evaporated under reduced pressure and the residue was dissolved in CHCl3 (100 mL). The organic solution was added to ice H2O, and the layers were separated. The aqueous layer was extracted with CHCl3 (3 × 50 mL), and the combined organic extracts were washed with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 solution (2 × 50 mL) and then H2O (2 × 50 mL). The CHCl3 solution was dried over MgSO4 and filtered, and the filtrates were evaporated on a rotary evaporator to yield crude 60. Recrystallization of this material using MeOH afforded 7.72 g (69%) of pure 60: mp 70–72 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 0.89 (t, 3 H, CH3), 1.25 (m, 4 H, 2 × H2), 2.48 (m, 2 H, CH2), 3.97 (m, 2 H, CH2), 5.03 (m, 2 H, CH2), 6.00 (m, 1 H, CH2), 7.36 (m, 5 H, C6H5 and NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 13.89, 22.23, 33.23, 33.61, 34.96, 116.71, 119.58, 128.79, 132.42, 135.67, 138.22, 156.91, 161.78.

[2-[[4-(1-Butyl)phenyl]amino]-4,6-dichloropyrimidin-5-yl]acetaldehyde (61)

To a suspension of 60 (37.12 g, 110.81 mmol) in MeOH (300 mL), acetone (200 mL), and H2O (200 mL) were added OsO4 (230 mg) and NaIO4 (94.8 g, 443.21 mmol). After mechanically stirring for 48 h, the reaction mixture was evaporated to remove the organic solvent. The suspension was diluted with H2O (500 mL) and extracted several times with EtOAc. The EtOAc layer was separated, dried over MgSO4, and evaporated to dryness. The crude product was recrystallized from a small amount of MeOH to give 61 (29.83 g, 79%) as white needles: 1H NMR (DMSO- d6) δ 0.91 (t, 3 H, CH3), 1.40 (m, 4 H, 2 × CH2), 1.99 (t, 2 H, CH2), 3.90 (s, 2 H, CH2CHO), 7.16 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2 H, ArH), 7.4 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2 H, ArH), 9.7 (s, 1 H, NH), 10.25 (s, 1 H, CHO); 13C NMR (DMSO- d6) δ 13.87, 21.71, 33.20, 34.24, 43.58, 112.65, 119.66, 128.38, 136.36, 137.01, 158.81, 161.37, 197.79.

2-[[4-(1-Butyl)phenyl]amino]-4,6-dichloro-5-(2,2-dimethoxyethyl)pyrimidine (62)

To a solution of 61 (29.25 g, 86.79 mmol) in dry MeOH (250 mL) was added pyridinium p-toluensulfonate (2.18 g, 8.67 mmol) and NH4Cl (460 mg, 8.68 mmol, freshly dried over P2O5), and this solution was refluxed for 4 h. After cooling to room temperature, the reaction mixture was treated with Norit-A and filtered through a pad of Celite, and the filtrate was evaporated to dryness. The residue was dissolved in AcOEt–hexane (2:8) and filtered through a plug of Florisil (150 g). Removal of the solvent and chromatography on Florisil (AcOEt–hexane, 2:8) gave 62 (29.71 g, 89%) as a yellow oil, which crystallized slowly at room temperature and was recrystallized from hexane to give pure 62 as colorless needles: mp 52–55 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 0.93 (t, 3 H, Me), 1.3 (m, 4 H, 2 × CH2), 2.5 (t, 2 H, CH2), 3.0 (d, 2 H, CH2), 3.3 (s, 6 H, OMe), 4.5 (t, 1 H, (MeO)2CH), 7.1 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2 H, ArH), 7.2 (s, 1 H, NH), 7.4 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2 H, ArH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 13.83, 22.39, 33.55, 33.72, 35.12, 54.14, 103.38, 116.93, 119.74, 129.01, 135.73, 138.43, 157.02, 162.43.

(±)-(1α,2β,3β,5β)-3-[2-[[4-(1-Butyl)phenyl]amino]-4-chloro-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pryimidin-7-yl]-5-(hydroxymethyl)-1,2-cyclopentanediol (64)

A mixture of (±)-4α-amino-2β,3β-dihydroxy-1α-cyclopentanemethanol (obtained by the acidic hydrolysis of 3.5 g (11.18 mmol) of its tetraacetate derivative54), 62 (3.0 g, 8.9 mmol), and Et3N (20 mL) in 1-BuOH (100 mL) was heated under reflx for 38 h. The reaction mixture was evaporated to dryness to give crude 63. A small amount of 63 was purified by column chromatography (CH2Cl2–MeOH, 95:5): 1H NMR (DMSO- d6) δ 0.89 (t, 3 H, Me), 1.42 (m, 5 H, 2 × CH2 and H-4), 2.0 (m, 2 H, H-4 and H-5), 2.5 (t, 2 H, CH2), 2.8 (d, 1 H, H-3), 3.3 (s, 6 H, 2 × OMe), 3.4–4.0 (m, 6 H, (MeO)2CHCH2-, CH2OH, H-1, and H-2), 4.2–5.2 (m, 4 H, (MeO)2CH amd 3 × OH), 6.5 (d, 1 H, NH), 7.0 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2 H, ArH), 7.6 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2 H, ArH), 9.2 (s, 1 H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO- d6) δ 12.57, 20.53, 30.50, 32.18, 33.35, 45.51, 51.57, 52.82, 53.20, 62.41, 75.74, 77.09, 99.09, 103.53, 117.34, 126.93, 133.59, 137.17, 156.38, 161.22.

The crude 63 from the above step was dissolved in 1,4-dioxane (200 mL), and 2 N HCl (20 mL) was added to this. After stirring for 20 h at room temperature, the reaction mixture was neutrallized with concentrated NH4OH followed by evaporation to dryness. The residue was purified by medium pressure chromatography (CH2Cl2–MeOH, 95:5) to give 64 (1.6 g, 42% based upon 62) as a yellow foam, which crystallized from CH2Cl2: mp 172–175 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO- d6) δ 0.89 (t, 3 H, Me), 1.41 (m, 5 H, 2 × CH2 and H-4′), 2.0 (m, 2 H, H-4′ and H-5′), 2.5 (m, 2 H, CH2), 3.1 (d, 1 H, H-3′), 3.2–4.0 (m, 6 H, CH2OH, H-1′, H-2′, and 2 × OH), 5.1 (d, 1 H, OH), 6.36 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1 H, H-7), 7.0 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2 H, ArH), 7.38 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 1 H, H-8), 7.7 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2 H, ArH), 9.5 (br, 1 H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO- d6) δ 13.97, 21.88, 29.74, 33.53, 34.40, 45.72, 55.31, 63.44, 77.14, 78.23, 98.00, 110.14, 118.48, 127.25, 128.45, 135.00, 138.58, 150.61, 152.88, 154.83.

(±)-(1α,2β)-2-(2-Amino-6-chloro-9H-purin-9-yl)cyclopentan-1-ol (68)

A solution of 18.64 g (114 mmol) of 2-amino-4,6-dichloropyrimidine and 11.50 g (114 mmol) of (±)-trans-2-aminocyclopentanol57 in BuOH was heated at reflux under Ar. Following the reflux period, the solvent was removed by distillation under reduced pressure and the residue treated with H2O. The resulting beige solid was collected by filtration and washed well with H2O followed by CHCl3. The solid that remained was dried at 60 °C under vacuum to give 18.13 g (70%) of (±)-(1α,2β)-2-[(2-amino-6-chloropyrimidin-4-yl)amino]-cyclopentan-1-ol, 65, as a tan solid, which was suficiently pure for the following step. An analytical sample was prepared by recrystallization from MeCN: mp 171–173 °C.

A solution of 3.42 g (26.85 mmol) of 4-chloroaniline in 95% EtOH (25 mL) was treated with concentrated H2SO4 (2.75 mL). The solution was cooled to 27 °C and treated dropwise with 1-butyl nitrite (3.2 g). The solution was then warmed carefully to 35–40 °C for 10 min and then chilled in ice. The crystals of diazonium salt that separated were collected and washed with a minimum amount of cold EtOH and used immediately in the next step.

The diazonium salt prepared in the last step was dissolved in MeOH (30 mL) and the resulting solution treated with 65 (3.0 g, 13.12 mmol). Yellow crystals began to separate immediately. After 20 min, a solution of anhydrous AcONa (2.2 g) in H2O (20 mL) was added and the reaction mixture then stirred for 90 min. The thick yellow paste was collected and washed well with hot MeOH. The bright yellow sample (4.10 g, 85%) of (±)-(1α,2β)-2-[[2-amino-6-chloro-5-[(4-chlorophenyl)azo]pyrimidin-4-yl]amino]cyclopentan-1-ol, 66, was dried under high vacuum and found to be suffiently pure to use in the next step.

A solution of 66 (1.6 g, 4.37 mmol) and Zn (2.5 g) in a mixture of AcOH (1 mL), EtOH (60 mL), and H2O (20 mL) was refluxed under N2 until the yellow color disappeared. After filtration, the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure to give a residue of (±)-(1α,2β)-2-[(2,5-diamino-6-chloropyrimidin-4-yl)amino]cyclopentan-1-ol, 67, which was placed in a mixture of cooled DMF (20 mL) and trimethyl orthoformate (50 mL) containing concentrated HCl (0.5 mL). This mixture was then stirred at room temperature overnight and the solvent mixture evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was stirred in 0.5 N HCl (50 mL) for 3 h. After adjusting the pH to 9, the mixture was evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure to provide a residue that was purified by column chromatography (CH2Cl2:MeOH, 10:1) to give 68 as white crystals following recrystallization from MeOH (770 mg, 68.8%): mp 197–198 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO- d6) δ 1.5–2.2 (m, 6 H, 3 × CH2 of cyclopentyl), 4.45 (m, 2 H, H-1 and H-2 of cyclopentyl), 6.88 (s, 2 H, NH2), 8.21 (s, 1 H, H-8 of purine); 13C NMR (DMSO- d6) δ 19.64, 28.53, 31.78, 62.55, 74.71, 123.78, 142.15, 149.27, 154.23, 159.45.

Cell Culture and Radioligand Binding

CHO cells stably expressing the A3 receptor9,19 were grown in F-12 medium containing 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/mL and 100 μg/mL, respectively) at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, and membrane homogenates were prepared as reported.9

Binding of [125I]-N6-(4-amino-3-iodobenzyl)adenosine-5′-(N-methyluronamide) ([125I]AB-MECA) to the CHO cells membranes was performed essentially as described.16,19 Assays were performed in 50/10/1 buffer in glass tubes and contained 100 μL of the membrane suspension, 50 μL of [125I]AB-MECA (final concentration 0.3 nM), and 50 μL of inhibitor. Inhibitors were routinely dissolved in DMSO and then diluted with buffer; final DMSO concentrations never exceeded 1%. Incubations were carried out in duplicate for 1 h at 37 °C and terminated by rapid filtration over Whatman GF/B filters, using a Brandell cell harvester (Brandell, Gaithersburg, MD). Tubes were washed three times with 3 mL of buffer. Radioactivity was determined in a Beckman γ-5500B counter. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 40 μM. (R)-PIA. Ki values were calculated according to the Cheng-Prusoff equation,41 assuming a Kd for [125I]AB-MECA of 1.55 nM.16

Binding of [3H]PIA (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) to A1 receptors from rat brain membranes and [3H]CGS 21680 (DuPont NEN, Boston, MA) to A2 receptors from rat striatal membranes was performed as described previously.17,18 Adenosine deaminase (3 U/mL) was present during the preparation of brain membranes, in which an incubation at 30 °C for 30 min is carried out, and during the incubation with radioligand. At least six different concentrations spanning 3 orders of magnitude, adjusted appropriately for the IC50 of each compound, were used. IC50 values, computer-generated using a nonlinear regression formula on the InPlot program (Graph-PAD, San Diego, CA), were converted to apparent Ki values using Kd values of 1.0 and 14 nM for [3H]PIA and [3H]CGS 21680 binding, respectively, and the Cheng–Prusoff equation.41

GTP shifts in the displacement of the binding of [3H]-8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (CPX; DuPont NEN) were determined as described.38 Adenylate cyclase measurements in A3-transfected CHO cells were carried out as described.9

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Lars Knutsen (Novo Nordisk) for the gift of metrifudil. We are thankful to Dr. John P. Scovill (U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, Frederick, MD), Dr. Xing Chen (University of South Florida, Tampa, currently affiliated with Schering-Plough Co., NJ), and Dr. Debra Heckendorn (U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, Frederick, MD, currently affiliated with U.S. Naval Academy) for synthesizing compounds 12a,b. A part of this project was supported by funds from the Department of Health and Human Services (NO1-AI-72645), and this is appreciated.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AB-MECA, N6-(4-aminobenzyl)adenosine-5′-(N-methyluronamide; CGS 21680, 2-[[[4-(2-carboxyethyl)phenyl]ethyl]-amino]-5′-(N-ethylcarbamoyl)adenosine; CHA, N6-cyclohexyladenosine; CHO, Chinese hamster ovary; CPA, N6-cyclopentyladenosine; CPX, 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine; DMAP, 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine; DMF, N,N-dimethylformamide; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; EtOH, ethanol; HE-NECA, 2-(1-hexynyl)-5′-(N-ethylcarbamoyl)adenosine; HMDS, hexamethyldisilazane; MeOH, methanol; MeCN, acetonitrile; NECA, 5′-(N-ethylcarbamoyl)adenosine; PIA, (R)-N6-(phenylisopropyl)-adenosine; THF, tetrahydrofuran; TMS, trimethylsilyl; TMS-OTf, trimethylsilyl trifluoromethanesulfonate; Tris, tris(hydroxymethyl)-aminomethane.

References

- 1.Jacobson KA, van Galen P, Williams M. Adenosine receptors - pharmacology, structure activity relationships, and therapeutic potential. J Med Chem. 1992;35:407–422. doi: 10.1021/jm00081a001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olsson RA, Pearson JD. Cardiovascular purinoceptors. Pharmacol Rev. 1990;3:761–845. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.3.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Lubitz DKJE, Jacobson KA. Behavioral effects of adenosine receptor stimulation. In: Bellardinelli L, Pelleg A, editors. Adenosine and Adenine Nucleotides: From Molecular Biology to Integrative Physiology. Kluwer; Norwell, MA: 1995. pp. 489–498. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linden J. Cloned adenosine A3 receptors: Pharmacological properties, species differences and receptor function. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1994;15:298–306. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(94)90011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stiles GL. Adenosine receptors. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:6451–6454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobson M. Cloning and expression of human adenosine receptor subtypes. In: Bellardinelli L, Pelleg A, editors. Adenosine and Adenine Nucleotides: From Molecular Biology to Integrative Physiology. Kluwer; Norwell, MA: 1995. pp. 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou QY, Li CY, Olah ME, Johnson RA, Stiles GL, Civelli O. Molecular cloning and characterization of an adenosine receptor - the A3 adenosine receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7432–7436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallo-Rodriguez C, Ji X-D, Melman N, Siegman BD, Sanders LH, Orlina J, Pu Q-L, Olah ME, van Galen PJM, Stiles GL, Jacobson KA. Structure-activity relationships at A3-adenosine receptors. J Med Chem. 1994;37:636–646. doi: 10.1021/jm00031a014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Galen PJM, van Bergen AH, Gallo-Rodriguez C, Melman N, Olah ME, IJzerman AP, Stiles GL, Jacobson KA. A binding site model and structure-activity relationships for the rat A3 adenosine receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;45:1101–1111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobson KA, Nikodijević O, Shi D, Gallo-Rodriguez C, Olah ME, Stiles GL, Daly JW. A role for central A3-adenosine receptors: Mediation of behavioral depressant responses. FEBS Lett. 1993;336:57–60. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81608-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Lubitz DKJE, Lin RCS, Popick P, Carter MF, Jacobson KA. Adenosine A3 receptor stimulation and cerebral ischemia. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;263:59–67. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90523-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu GS, Richards SC, Olsson RA, Mullane K, Walsh RS, Downey JM. Evidence that the adenosine A3 receptor may mediate the protection afforded by preconditioning in the isolated rabbit heart. Cardiovasc Res. 1994;28:1057–1061. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.7.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bai TR, Weir T, Walker BAM, Salvatore CA, Johnson RG, Jacobson MA. Comparison and localization of adenosine A3 receptor expression in normal and asthmatic lung. Drug Dev Res. 1994;31:244. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson RD, Secunda S, Daly JW, Olsson RA. N6,9-Disubstituted Adenines - Potent, Selective Antagonists at the A1-Adenosine Receptor. J Med Chem. 1991;34:2877–2882. doi: 10.1021/jm00113a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lohse MJ, Klotz KN, Diekmann E, Friedrich K, Schwabe U. 2′,3′-Dideoxy-N6-cyclohexyladenosine: an adenosine derivative with antagonist properties at adenosine receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 1988;156:157–160. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90158-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim HO, Ji X-d, Melman N, Olah ME, Stiles GL, Jacobson KA. Structure activity relationships of 1,3-dialkylxanthine derivatives at rat A3-adenosine receptors. J Med Chem. 1994;37:3373–3382. doi: 10.1021/jm00046a022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwabe U, Trost T. Characterization of adenosine receptors in rat brain by (−) [3H]N6-phenylisopropyladenosine. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 1980;313:179–187. doi: 10.1007/BF00505731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jarvis MF, Schutz R, Hutchison AJ, Do E, Sills MA, Williams M. [3H]CGS 21680, an A2 selective adenosine receptor agonist directly labels A2 receptors in rat brain tissue. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;251:888–893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olah ME, Gallo-Rodriguez C, Jacobson KA, Stiles GL. [125I]AB-MECA, a high affinity radioligand for the rat A3 adenosine receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;45:978–982. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siddiqi SM, Chen X, Schneller SW. Enantiospecific synthesis of 5′-noraristeromycin and its 7-deaza derivative and a formal synthesis of (-)-5′-homoaristeromycin. Nucleosides Nucleotides. 1993;12:267–278. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson CR, Esker JL, van Zandt MC. Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of 4-Substituted Riboses: S-(4-methyl adenosyl)-L-homocysteine. J Org Chem. 1994;59:5854–5855. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vorbrüggen H, Krolikiewicz K, Bennua B. Nucleoside synthesis with trimethylsilyl triflate and perchlorate as catalysts. Chem Ber. 1981;114:1234–1255. and references cited therein. [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Chattopadhyaya JB, Reese CB. Reaction between 8-bromoadenosine and amines. Chemistry of 8-hydrazinoadenosine. Synthesis. 1977:725. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ikehara M, Yamada S. Studies of Nucleosides and Nucleotides. XLIX.1) Synthesis of 8-Fluoroadenosine.2) Chem Pharm Bull. 1971;19:104–109. [Google Scholar]

- 24.(a) Siddiqi SM, Chen X, Schneller SW, Ikeda S, Snoeck R, Andrei A, Balzarini J, De Clercq E. Antiviral enantiomeric preference for 5′-noraristeromycin. J Med Chem. 1994;37:551–554. doi: 10.1021/jm00030a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Siddiqi SM, Chen X, Schneller SW, Ikeda S, Sneock R, Andrei G, Balzarini J, De Clercq E. An epimer of 5′-noraristeromycin and its antiviral properties. J Med Chem. 1994;37:1382–1384. doi: 10.1021/jm00035a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Marquez VE, Lim MI. Carbocyclic nucleosides. Med Res Rev. 1986;6:1–40. doi: 10.1002/med.2610060102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Francis JE, Webb RL, Ghai GR, Hutchison AJ, Moskal MA, Dejesus R, Yokoyama R, Rovinski SL, Contardo N, Dotson R, Barclay B, Stone GA, Jarvis MF. Highly selective adenosine-A2 receptor agonists in a series of N-alkylated 2-aminoadenosines. J Med Chem. 1991;34:2570–2579. doi: 10.1021/jm00112a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bruns RF. Adenosine receptor activation in human fibroblasts: nucleoside agonists and antagonists. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1980;58:673–691. doi: 10.1139/y80-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.(a) Kusaka T, Yamamoto H, Shibata M, Muroi M, Kishi T, Mizumo K. Streptomyces Citricolor No. Sp. and a new antibiotic aristeromycin. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1968;21:255–263. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.21.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kishi T, Muroi M, Kusaka T, Nishikawa M, Kamiya K, Mizuno K. The structure of aristeromycin. Chem Pharm Bull. 1972;20:940–946. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siddiqi SM, Schneller SW, Ikeda S, Snoeck R, Andrei G, Balzarini J, De Clercq E. S-Adenosyl-L-homocysteine hydrolase inhibitors as antiviral agents: 5′-Deoxyaristeromycin. Nucleosides Nucleotides. 1993;12:185–198. [Google Scholar]

- 29.(a) Tiwari KN, Secrist JA, Montgomery JA. Synthesis and biological activity of 4′-thionucleosides of 2-chloroadenosine. Nucleosides Nucleotides. 1994;13:1819–1828. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tiwari KN, Secrist JA, Montgomery JA, Masini L. Synthesis and biological activity of 4′-thioarabinonucleosides. Submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas HJ, Tiwari KN, Clayton SJ, Secrist JA, Montgomery JA. Synthesis and biological activity of purine 2′-deoxy-2′-fluororibonucleosides. Nucleosides Nucleotides. 1994;13:309–323. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cristalli G, Vittori S, Eleuteri A, Volpini R, Camaioni E, Lupidi G. Synthesis of 2′-deoxyribonucleoside derivatives of 1-dezazpurine. Nucleosides Nucleotides. 1994;13:835–848. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cristalli G, Vittori S, Eleuteri A, Volpini R, Camaioni E, Lupidi G. Manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagner H, Milavec-Krizman M, Gadient F, Menninger K, Schoeffter P, Tapparelli C, Fozard JR. Drug Dev Res. 1994;31:270. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shuman DA, Robins RK, Robins MJ. The synthesis of adenine 5′-O-sulfamoyl nucleosides related to nucleocidin. J Am Chem Soc. 1969;91:3931–3932. doi: 10.1021/ja01040a062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cristalli G, Franchetti P, Grifantini M, Vittori S, Klotz KN, Lohse MJ. Adenosine receptor agonists: synthesis and biological evaluation of 1-deaza analogues of adenosine derivatives. J Med Chem. 1988;31:1179–1183. doi: 10.1021/jm00401a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.(a) Cristalli G, Eleuteri A, Vittori S, Volpini R, Lohse MJ, Klotz KN. 2-Alkynyl derivatives of adenosine and adenosine-5′-N-ethyluronamide as selective agonists at A2 adenosine receptors. J Med Chem. 1992;35:2363–2368. doi: 10.1021/jm00091a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cristalli G, Volpini R, Vittori S, Camaioni E, Monopoli A, Conti A, Dionisotti S, Zocchi C, Ongini E. 2-Alkynyl derivatives of adenosine-5′-N-ethyluronamide: Selective A2 adenosine receptor agonists with potent inhibitory activity on platelet aggregation. J Med Chem. 1994;37:1720–1724. doi: 10.1021/jm00037a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wildbrandt R, Frotscher U, Freyland M, Messerschmidt W, Richter R, Schulte-Lippern M, Zschaege B. Treatment of glomerulonephritis with metrifudil. Preliminary Report. Med Klin (Munich) 1972;67(36):1138–1140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.(a) van der Wenden EM. PhD Thesis. University of Leiden; 1994. Structural requirements for the interaction between ligands and the adenosine A1 receptor: A search for partial agonists. [Google Scholar]; (b) van der Wenden EM, vonFrijtag Drabbe Künzel JK, Mathôt RAA, IJzerman AP, Soudijn W. Ribose modified adenosine analogues as potential partial agonists for the adenosine receptor. Drug Dev Res. 1994;31:330. doi: 10.1021/jm00020a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim HO, Ji X-d, Siddiqi SM, Olah ME, Stiles GL, Jacobson KA. 2-Substitution of N6-benzyladenosine-5′-uronamides enhances selectivity for A3-adenosine receptors. J Med Chem. 1994;37:3614–3621. doi: 10.1021/jm00047a018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sipe JC, Romine JS, Koziol JA, McMillan R, Zyroff J, Beutler E. Cladribine in treatment of chronic progressive multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1994;2:9–13. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheng YC, Prusoff WH. Relationship between the inhibition constant (Ki) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 percent inhibition (IC50) of an enzyme reaction. Biochem Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cristalli G, Grifantini M, Vittori S, Balduini W, Cattabeni F. Adenosine and 2-chloroadenosine deaza analogues as adenosine receptor antagonists. Nucleosides Nucleotides. 1985;4:625–639. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Daly JW, Padgett WL. Agonist activity of 2- and 5′-substituted adenosine analogues and their N6-cycloalkyl derivatives at A1-adenosine and A2-adenosine receptors coupled to adenylate cyclase. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;43:1089–1093. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90616-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siddiqi SM, Chen X, Rao J, Schneller SW, Ikeda S, Snoeck R, Andrei G, Balzarini J, De Clercq E. 3-Deaza- and 7-deaza-5′-noraristeromycin and their antiviral properties. J Med Chem. 1994 doi: 10.1021/jm00006a023. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iwamura H, Ito T, Kumazawa Z, Ogawa Y. Anticytokinin activity of 4-furfurylamino-7-(β-D-ribofuranosyl)pyrrolo[2,3-d]-pyrimidines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1974;57:412–416. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(74)90946-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kazimierczuk Z, Cottam HB, Revankar GR, Robins MJ. Synthesis of 2′-deoxytubercidin, 2′-deoxyadenosine, and related 2′-deoxynucleosides via a novel direct stereospecific sodium salt glycosylation procedure. J Am Chem Soc. 1969;91:3931–3932. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cermak RC, Vince R. (±)-4β-Amino-2α,3α-dihydroxy-1β-cyclopentanemethanol hydrochloride. Carbocyclic ribofuranosylamine for the synthesis of carbocyclic nucleosides. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981;22:2331–2332. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cristalli G, Vittori S, Eleuteri A, Grifantini M, Volpini R, Lupidi G, Capolongo L, Pesenti E. Purine and 1-deazapurine ribonucleosides and dexoyribonucleosides: Synthesis and biological activity. J Med Chem. 1991;34:2226–2230. doi: 10.1021/jm00111a044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nutt RF, Dickinson MJ, Holly FW, Walton E. Branched-Chain Sugar Nucleosides. III. 3′-C-Methyladenosine. J Org Chem. 1968;33:1789–1759. doi: 10.1021/jo01269a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Waga T, Nishizaki T, Miyakawa I, Ohrui O, Meguro H. Synthesis of 4′-C-Methylnucleosides. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1993;57:1433–1438. doi: 10.1271/bbb.57.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.(a) Secrist JA, III, Montgomery JA, Shealy YF, O’Dell CA, Clayton SJ. Resolution of Racemic Carbocyclic Analogues of Purine Nucleosides through the Action of Adenosine Deaminase. Antiviral Activity of the 2′-Deoxyguanosine Enantiomers. J Med Chem. 1987;30:746–749. doi: 10.1021/jm00387a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Herdewijn P, Balzarini J, De Clerq E, Vanderhaeghe H. Resolution of Aristeromycin Enantiomers. J Med Chem. 1985;28:1385–1386. doi: 10.1021/jm00148a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen X, Siddiqi SM, Schneller SW, Snoeck R, Balzarini J, De Clercq E. Synthesis and Antiviral Properties of Carbocyclic 3′-Oxa-2′,3′-dideoxyguanosine and Its 7-Deazaguanosine Analogue. Antiviral Res. 1993;20:333–345. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(93)90076-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seela F, Bussmann W, Götze A, Rosemeyer H. Isomeric N-methyl-7-deazaguanosines: Synthesis, Structural Assignment, and Inhibitory Activity on Xanthine Oxidase. J Med Chem. 1984;27:981–985. doi: 10.1021/jm00374a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vince R, Brownell J, Daluge S. Carbocyclic Analogues of Xylofuranosylpurine Nucleosides. Synthesis and Antitumor Activity. J Med Chem. 1984;27:1358–1362. doi: 10.1021/jm00376a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schneller SW, Chen X, Siddiqi SM. Carbocyclic 7-Deazaguanosine Nucleosides As Antiviral Agents. In: Chu CK, Baker DC, editors. Nucleosides and Nucleitides as Antitumor and Antiviral Agents. Plenum Press; New York: 1993. pp. 141–158. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Patil SD, Schneller SW. (±)-5′-Nor Ribofuranoside Carbocyclic Guanosine. J Heterocycl Chem. 1991;28:823–825. [Google Scholar]

- 57.McCasland GE, Smith DA. Stereochemistry of Aminocyclanols. Synthesis of cis-Epimers via Oxazolines. The 2-Aminocyclopentanols. J Am Chem Soc. 1950;72:2190–2195. [Google Scholar]