Abstract

Bacterial vaginosis is a common vaginal infection associated with numerous gynecological and obstetric complications. This condition is characterized by the presence of thick adherent vaginal biofilms, composed mainly of Gardnerella vaginalis. This organism is thought to be the primary aetiological cause of the infection paving the way for various opportunists to colonize the niche. Previously, we reported that the natural antimicrobials subtilosin, ε-poly-L-lysine, and lauramide arginine ethyl ester selectively inhibit the growth of this pathogen. In this study, we used plate counts to evaluate the efficacy of these antimicrobials against established biofilms of G. vaginalis. Additionally, we validated and compared two rapid methods (ATP viability and resazurin assays) for the assessment of cell viability in the antimicrobial-treated G. vaginalis biofilms. Out of the tested antimicrobials, lauramide arginine ethyl ester had the strongest bactericidal effect, followed by subtilosin, with clindamycin and polylysine showing the weakest effect. In comparison to plate counts, ATP viability and resazurin assays considerably underestimated the bactericidal effect of some antimicrobials. Our results indicate that these assays should be validated for every new application.

1. Introduction

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is the most common vaginal infection in women of childbearing age [1, 2]. This condition is characterized by the replacement of vaginal lactobacilli with a variety of predominantly-anaerobic pathogens, such as Gardnerella vaginalis, Prevotella, Peptostreptococcus, and Bacteroides spp., with total bacterial numbers often rising 100- to 1000-fold compared to the normal levels in the vagina [3–8]. These changes within the vaginal microbiota are frequently (but not always) accompanied by an elevation in vaginal pH and by an abundance of vaginal secretions that have a typical amine odor [9]. Aside from being a major nuisance due to its symptoms, BV (even in its asymptomatic form) has been associated with serious gynecological and obstetric complications [10–13]. In particular, BV may lead to preterm birth in pregnant women, a major risk factor for perinatal mortality and morbidity [14–16]. BV is a risk factor for the development of after abortion endometritis and pelvic infection following gynecologic surgery [17, 18]. There is also evidence that BV increases the chance of transmission and acquisition of sexually-transmitted infections, such as HIV [19, 20] and HSV-2 [21, 22].

Due to the complex polymicrobial nature of this disorder, conventional treatments for BV, with the antibiotics clindamycin and metronidazole, are notorious for their low (60%) efficacy and high (30–40%) rates of recurrent infection [23–27]. The exact aetiology of BV remains unclear despite decades of intense research, making it a challenge to design effective treatment [28]. Since most BV-related species are frequently isolated from the vaginas of healthy women, many researchers view BV as a microbial imbalance rather than an infection [29–31]. Conversely, there is also evidence that at least some BV-related pathogens can be transmitted sexually [32, 33]. Ultimately, most researchers agree that the aetiology of BV is complex and that the outcome of the infection depends not only on the pathogens but also on the indigenous vaginal microflora and the host's immunity [28].

Historically, G. vaginalis was thought to be the sole causative agent of this condition [34, 35], however its role in the aetiology of BV was downgraded over the years as the plethora of other bacterial species was gradually linked to the condition [28, 34, 36]. Recent evidence has once again placed G. vaginalis in the spotlight. In particular, studies of vaginal biopsy samples revealed that dense adherent biofilms of G. vaginalis, in contrast to the sparse cells, were detected only in the vaginas of BV patients and not in healthy women [37]. In vitro studies assessing adherence, biofilm formation capabilities, and cytotoxicity among BV-related anaerobes indicated that G. vaginalis has the highest virulence potential [38]. Finally, vaginal biofilms composed mainly of G. vaginalis were shown to persist following standard antibiotic therapy [39]. Presumably, bacteria within these biofilms serve as a reservoir for the recovery of BV microbiota after the cessation of antibiotic therapy leading to recurrence of BV [39]. These findings suggest that G. vaginalis may have a leading role in the BV infection process, paving the way for various opportunists to colonize the vagina [38].

The less than satisfactory performance of antibiotics is thought to be due to their inability to fully eradicate BV-associated pathogens (partly because of emerged resistance), and to their negative impact on healthy vaginal microbiota [37, 39, 40]. For this reason, novel antimicrobials, with the ability to selectively target vaginal pathogens, particularly biofilms, are critically needed.

The bacteriocin subtilosin is a promising alternative treatment for BV, especially when used as part of a multiple-hurdle approach, a tactic well known to drastically hinder microbial resistance mechanisms [41, 42]. Subtilosin (subtilosin A) is a cyclic 34-amino acid peptide produced by a dairy-derived strain, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens KATMIRA1933. This peptide was shown to inhibit the growth of BV-associated G. vaginalis, Mobiluncus curtisii, and Peptostreptococcus anaerobius [41]. Sutyak Noll et al. [41] reported that natural antimicrobials ε-poly-L-lysine (polylysine) and lauramide arginine ethyl ester (LAE) synergized with subtilosin in inhibiting G. vaginalis. Importantly, the subtilosin-based antimicrobial formulations involving polylysine and LAE did not inhibit the growth of vaginal lactobacilli strains [41]. Polylysine is cationic polypeptide consisting of 25–35 L-lysine residues. Numerous in vivo studies indicated that this antimicrobial is safe for human consumption and it is currently on the commercial market in Japan as a food preservative [43–45]. LAE is a derivative of lauric acid,L-arginine, and ethanol [46] with the generally recognized as safe (GRAS) status for use in meat, poultry, and other food products (GRAS notice no. GRN 000164). To this point, only the inhibitory activity of subtilosin, polylysine, and LAE has been evaluated against BV-related pathogens. Prevention of pathogenic growth is a model reflective of prophylaxis but not necessarily of treatment of BV, since this condition is characterized by the presence of already-established pathogenic vaginal biofilms [37]. Due to protection of exopolysaccharide matrix and other factors, biofilm cells are generally more resistant to stresses than their planktonic counterparts [47, 48]. Therefore, concentrations of antimicrobials that are effective against biofilms are expected to be higher than the concentrations effective against planktonic cells.

This study assessed bactericidal properties of subtilosin, polylysine, and LAE against established G. vaginalis biofilms in comparison to clindamycin. The activity of each antimicrobial was evaluated by three different methods (plate counting, ATP viability, and resazurin assays) to determine the advantages and limitations of each method when used to study G. vaginalis biofilms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Media, Strains, and Growth Conditions

G. vaginalis ATCC 14018 was stored at −80°C in Brain-Heart Infusion (BHI) medium (Difco, Sparks, MD) supplemented with 3% horse serum (JRH Biosciences, KS) and with 15% glycerol added to the total volume. The cells were propagated anaerobically at 37°C in BHI with 3% horse serum. For experimental procedures, G. vaginalis was subcultured at least once in BHI broth supplemented with 1% glucose (BHIG). Media used for all procedures involving G. vaginalis were preincubated overnight at 37°C in an anaerobic environment to minimize any stress to the cells (i.e., oxygen, low temperature).

Frozen stocks of Lactobacillus vaginalis ATCC 49540, Lactobacillus gasseri ATCC 33323, and Lactobacillus plantarum ATCC 39268 were stored at −80°C in MRS broth containing 15% glycerol (v/v). The cells were propagated in DeMan, Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS) broth at 37°C under aerobic conditions and were subcultured at least twice prior to being used in the experiments.

2.2. Preparations of Antimicrobials

The antimicrobials used were subtilosin, ε-poly-L-lysine (polylysine), lauramide arginine ethyl ester (LAE), and clindamycin. Subtilosin was produced through fermentation of B. amyloliquefaciens KATMIRA1933 and purified as described previously [42]. The aqueous stock solution of subtilosin contained 2.65 mg/mL protein as determined by Micro BCA. Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) and produced a single band on a silver stained SDS-PAGE gel indicating its purity. Polylysine (250 mg/mL) and LAE (100 mg/mL, MIRENAT-CF) were gifts from Chisso America, Inc. (Rye, NY, USA) and Vedeqsa Inc. (Barcelona, Spain), respectively; clindamycin phosphate was purchased from TCI America (Portland, OR, USA). The aqueous solutions of all the antimicrobials were filter-sterilized through 0.2 μm syringe filters (NALGENE, Rochester, NY, USA) prior to use. The antimicrobials were then serially diluted with BHIG broth to attain the desirable concentrations.

2.3. Minimial Inhibitory Concentrations

Minimal Inhibitory Concentrations (MICs) of the tested antimicrobials were determined using the assay described by Sutyak Noll et al. [41] with minor modifications. Briefly, serial 2-fold dilutions of each antimicrobial were prepared in a 96-well microplate (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) with appropriated bacterial growth medium being used as a diluent. Then, the overnight culture was added to each well of the plate at 1% of the total volume (200 μL). G. vaginalis plates were incubated anaerobically at 37°C for 24 hours. Lactobacilli plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours under aerobic conditions. Bacterial growth was evaluated following the incubation period by taking an endpoint reading at OD595 with a microplate reader (Model 550, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA).

2.4. Growth of Biofilms

Unless stated otherwise, all biofilm-related procedures were conducted at 37°C within the anaerobic glove box (Coy Laboratory Products, Inc., Grass Lake, MI, USA) which was supplied with a gas mixture containing 10% hydrogen, 5% carbon dioxide, and 85% nitrogen. To grow biofilms, BHIG broth was inoculated with an overnight culture (1%) and dispensed into a 96-well microplate (200 μL in each well). Transparent MICROTEST tissue culture plates with flat bottoms (BD) were used to grow biofilms for all the experiments involving antimicrobials. Biofilms were grown in opaque tissue culture plates (BD) to compare the ATP content of intact and disrupted biofilms. The plates were incubated for either 25 or 50 hours (depending on the experimental objective) with the growth medium being replaced every 25 hours.

The activity of the antimicrobials was evaluated using 25-hour biofilms. The supernatant covering the biofilms was removed using a micropipette, and each well of the plate was gently washed with 200 μL of BHIG broth. Then 200 μL of BHIG broth containing the selected antimicrobial was dispensed over each biofilm. After 25 hours of incubation the antimicrobial-containing medium was removed with a micropipette. Each well was gently washed with 200 μL of BHIG broth, and 200 μL of BHIG broth was dispensed over each biofilm. The cell viability of each biofilm was then quantified using the following three methods.

2.5. Plate Counting

Biofilms were first disrupted by vigorous pipetting. The cell suspension was then serially diluted using BHIG broth and 10 μL of each dilution was plated in four replicates (40 μL in total) on BHI agar plates using the drop plate method described by Hoben and Somasegaran [50] and Herigstad et al. [51]. Colonies on the plates were counted after 72 hours of incubation under anaerobic conditions at 37°C.

2.6. ATP Viability Assay

The ATP viability assay was conducted using the method described by Patterson et al. [48] with minor modifications. Briefly, biofilms were turned into cell suspensions by vigorous pipetting. Each suspension was diluted ten-fold with BHIG broth and 270 μL of the dilution was transferred into a well of a white opaque tissue culture plate (BD). The plate was centrifuged for five minutes (1238 g, 22°C) and the liquid in each well was carefully removed with a micropipette. The wells were then gently washed with 200 μL of PBS buffer. After this procedure, 50 μL of BacTiter-Glo (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) reagent was dispensed over the cells in each well. Following five minutes of incubation at ambient temperature, luminescence readings (integration time 500 ms) were taken using Luminoscan Ascent (Thermo Scientific, Barrington, IL, USA). Aside from experimental samples, each plate contained standards which were used to construct standard curves relating the measurements of luminescence to viable cell count (VCC). These standards were prepared by vigorously pipetting untreated biofilms and by making serial dilutions of the cell suspension.

2.7. Resazurin Assay

The assay was conducted using methods described by Extremina et al. [52] and Pettit et al. [53] with some modifications. Biofilms were disrupted by pipetting, and 24 μL of 2 μM resazurin solution was added to 170 μL of the cell suspension. The change in absorbance at OD595 was monitored every 120 seconds using a Bio-Rad microplate reader, Model 500 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Kinetic curves were generated with the Microplate Manager 5.2.1 software (Bio-Rad). This software was also used to determine the inverse slope (change in OD595 over time, AU/sec) of each curve during a 600 second incubation interval. The inverse slope is predicted to be proportional to the number of viable cells because it corresponds to the rate of resazurin reduction.

2.8. Microscopy

For microscopic imaging, cells were grown in Lab-Tek II Chambered Coverglass System (NUNCTM, Rochester, NY, USA) for 25 hours. Biofilms were handled as described above, and were then stained with LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability Kit for microscopy (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) by following the manufacturer's instructions. The imaging was performed with LSM 710 Confocal Microscope (Carl Zeiss, New York, NY, USA) under 1000x magnification using 488 nm laser and two detection channels with spectra ranging between 493–526 nm and 598–633 nm, respectively.

2.9. Data Analysis and Statistics

All experiments were conducted at least three times in duplicate. The standard deviation is represented in the figures by error bars. The efficacy of the antimicrobials (Figure 2) was evaluated using cumulative data from three independent experiments. The cell viability of each biofilm was assessed simultaneously by the three methods. The methods were compared within a single experimental set (Figure 4). Unless stated otherwise, calculations were carried out in Microsoft Excel, and the results were graphed using SigmaPlot 11.0 (Systat Software Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical analysis was performed with SigmaPlot 11.0 (Systat Software Inc.) using the Student's t-test (P ≤ 0.01).

Figure 2.

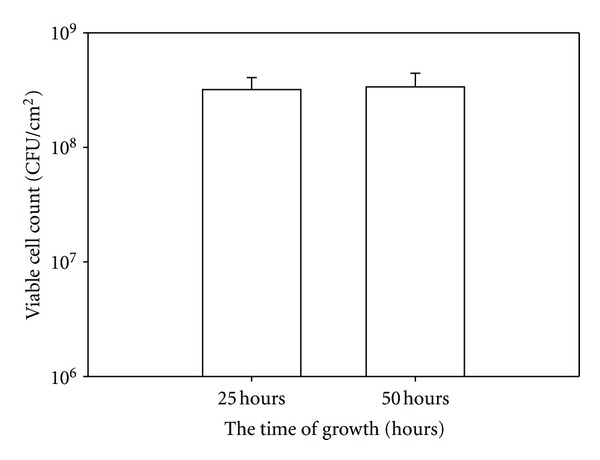

The viable cell counts in 25 and 50-hour biofilms of G. vaginalis.

Figure 4.

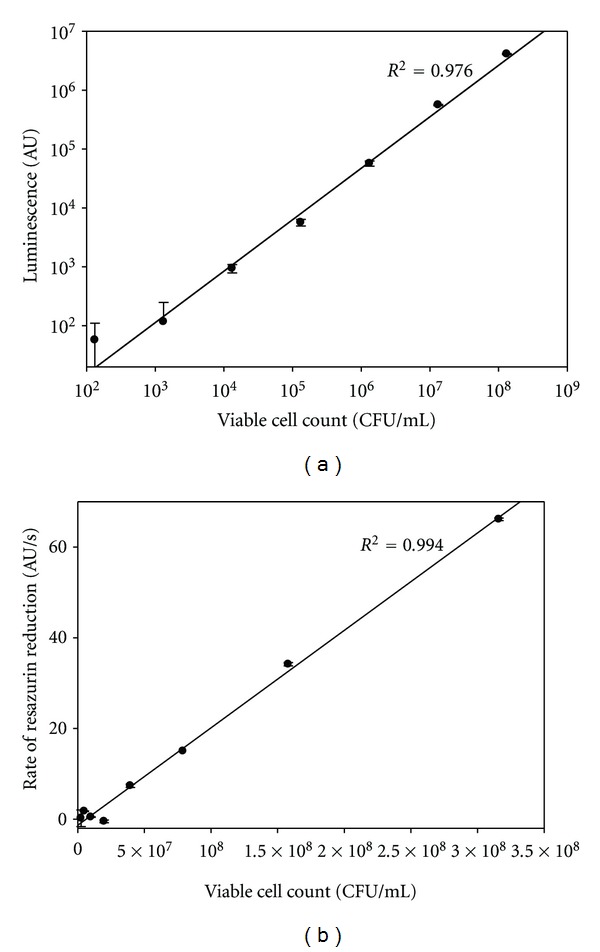

Standard curves relating measurements obtained by ATP viability (a) and resazurine (b) assays to the number of viable biofilm cells. The linear range is between 103–108 CFU/mL for the ATP viability assay (a) and between 107–108 CFU/mL for the resazurine assay (b).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. General Description of G. vaginalis Biofilm

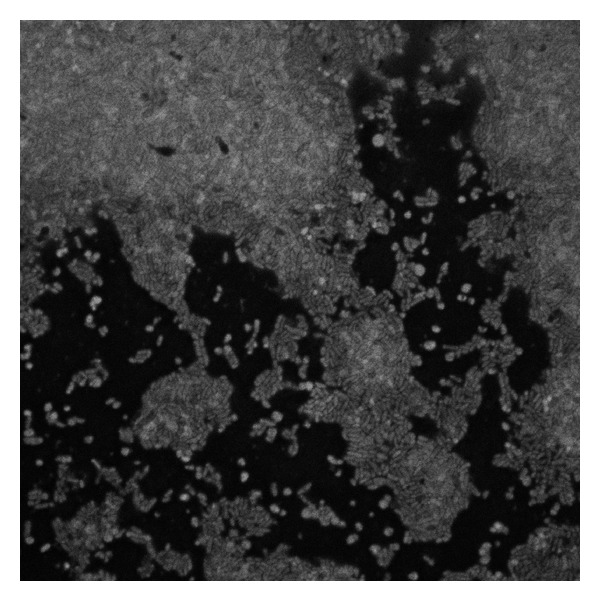

G. vaginalis formed confluent multilayered biofilms on both polystyrene and glass surfaces. Microscopic examination of the single-layered region near the edge of the slide revealed cells densely packed within an exopolysaccharide matrix (Figure 1). As expected, exposure to oxygen and ambient temperatures had a detrimental effect on G. vaginalis [54]. Mature (25 hours) G. vaginalis biofilms that were washed and plated on the bench as described by Patterson et al. [48] (under aerobic conditions at ambient temperatures) had 100-fold fewer viable cells compared to the biofilms handled in the anaerobic chamber at 37°C; in both cases agar plates were incubated anaerobically. Therefore, to minimize stress to the cells, all procedures, except for the luminescence measurements, were conducted in the anaerobic chamber at 37°C.

Figure 1.

The 24-hour biofilm of G. vaginalis on a glass surface.

3.2. Bactericidal Effect of Four Antimicrobials on Biofilms of G. vaginalis

The minimal inhibitory concentrations of the antimicrobials in our system were similar to those reported for G. vaginalis in the literature (Table 1). The discrepancies between the previously reported MIC values and the ones we measured can be attributed to differences in bacterial growth media and other conditions of the assay. For each antimicrobial, three concentrations covering the 100-fold range were tested against G. vaginalis biofilms. The comparison between the antimicrobials was made at 10x the MIC concentration reported in the literature.

Table 1.

Minimal inhibitory concentrations of the antimicrobials tested against G. vaginalis.

| Antimicrobial | MIC (μg/mL) |

|---|---|

| Subtilosin | 7.21/9.22, Sutyak Noll et al. [41] |

| ε-poly-L-lysine | 331/252, Sutyak Noll et al. [41] |

| Lauramide arginine ethyl ester | 13.31/102, Sutyak Noll et al. [41] |

| Clindamycin | 1.91/162, Catlin [34], Martens et al. [49] |

1MIC in BHIG broth, 2Reported elsewhere.

After 25 hours of incubation the VCC in G. vaginalis biofilms reached 108 CFU/cm2. The VCC did not change following the additional 25 hours of incubation in BHIG broth (the duration of antimicrobial exposure) (Figure 2). Therefore, any decrease in VCC following exposure of the biofilm to the antimicrobials signifies cell death.

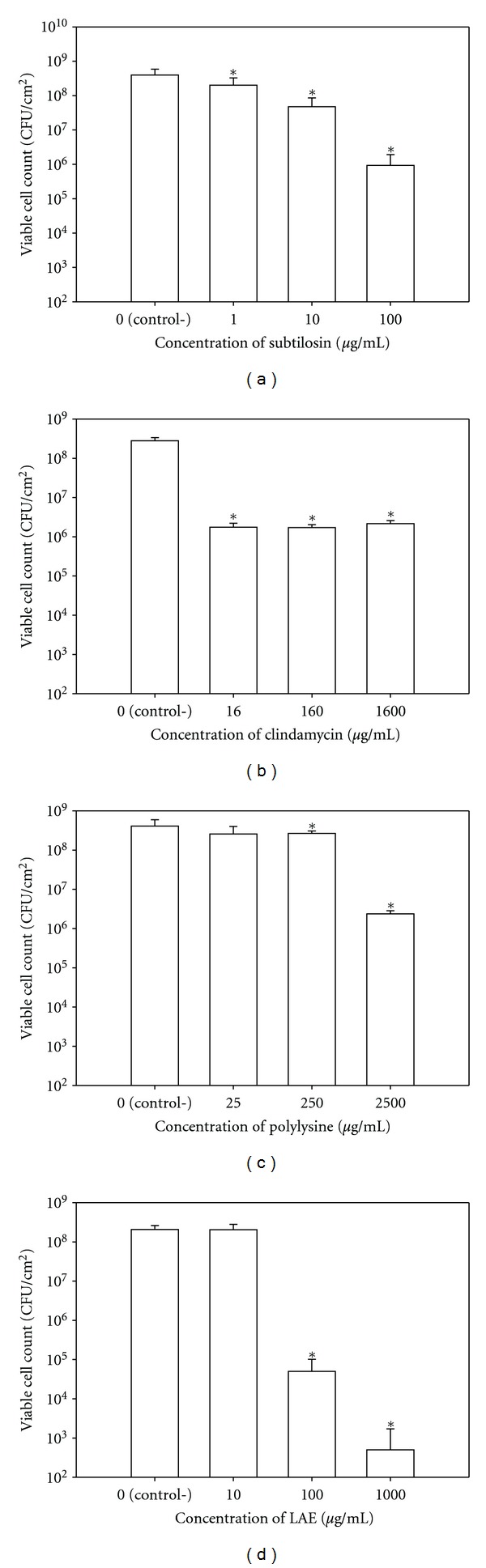

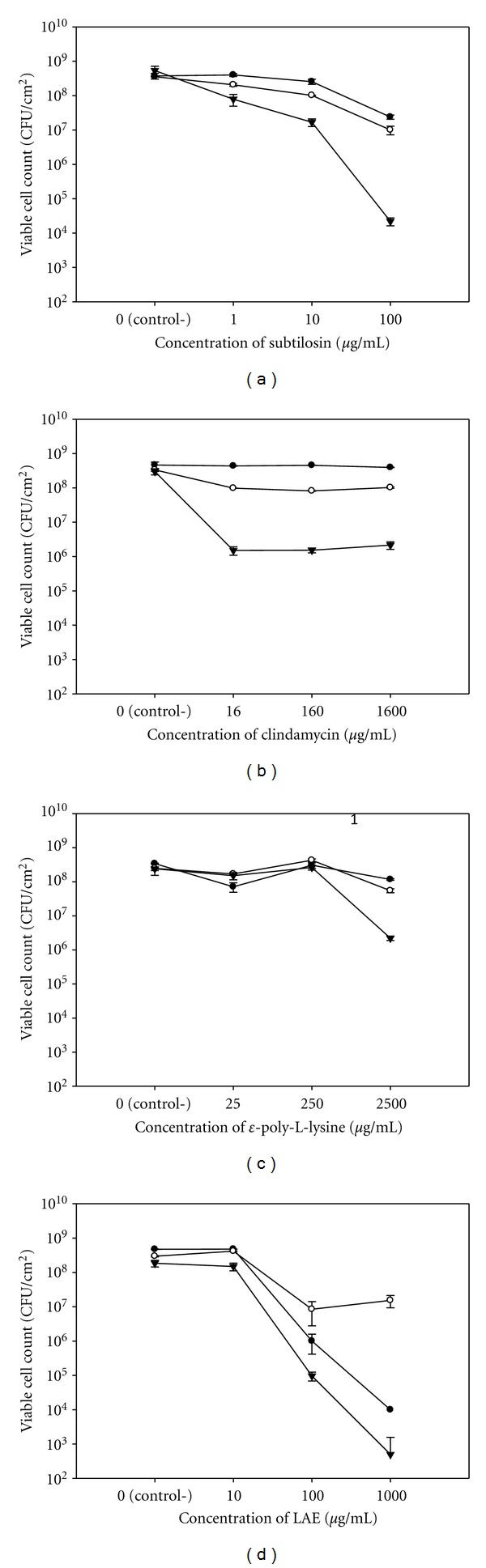

Clindamycin and polylysine produced only up to a 2-log reduction in the VCC of G. vaginalis (Figures 3(b) and 3(c), resp.). The effect of clindamycin remained constant within the tested range (16–1600 μg/mL) suggesting that it reached its threshold of activity. Only the highest concentration of polylysine (2500 μg/mL) reduced the VCC by more than 1 log. The antimicrobial activity of polylysine is related to its electrostatic adsorption to a cell's surface causing cell clumping and ultimately the cessation of protein synthesis [55]. Similarly, clindamycin is a protein synthesis inhibitor [56]. The cellular functions affected by these two antimicrobials may not be essential for survival of established biofilms in the absence of other stressors.

Figure 3.

Bactericidal effects of the antimicrobials subtilosin (a), clindamycin (b), polylysine (c), and LAE (d) against G. vaginalis biofilms as assessed by plate counting. Bars in each figure represent cumulative data from three independent experiments conducted in duplicate. Data sets that are statistically different from controls (P ≤ 0.01) are designated with asterisks (*).

In contrast to clindamycin and polylysine, LAE reduced the VCC in biofilms of G. vaginalis by up to 5 logs with a clear dose response within the tested range (10–1000 μg/mL) (Figure 3(d)). It is likely that the effectiveness of LAE against biofilms of G. vaginalis is at least partly related to the detergent properties of this compound [46]. Dose response within the tested range (1–100 μg/mL) was also observed for subtilosin with about 3-log reduction in VCC at concentration of 10x MIC (Figure 3(a)). Although both subtilosin and LAE target bacterial cytoplasmic membranes, these two antimicrobials have different molecular mechanisms of action [46, 57]. When compared at 10x MIC, subtilosin was less effective in reducing the number of viable biofilm cells than LAE but more effective than clindamycin and polylysine.

Most investigators agree that effective treatment for BV should selectively target BV-related pathogens, while allowing healthy vaginal microbiota to proliferate and recover. Swidsinski et al. [37] reported that in vivo vaginal lactobacilli do not form confluent biofilms; instead, they are sparsely distributed on vaginal epithelium. Therefore, in vitro studies involving lactobacilli biofilms may not be reflective of the situation in vivo. For these reasons, in our preliminary investigation we evaluated safety of the selected antimicrobials against commonly isolated vaginal Lactobacillius spp. (L. vaginalis, L. gasseri, and L. plantarum) by determining the MIC values.

The MICs of clindamycin greatly varied between the lactobacilli species, ranging from 0.78 to >50 μg/mL (Table 2). Earlier reports also suggested that clindamycin (much like metronidazole) can be harmful to healthy vaginal microflora [40]. In contrast, subtilosin was not inhibitory to any of the selected Lactobacillus spp. even at the highest tested concentration (100 μg/mL).

Table 2.

Minimal inhibitory concentrations of the antimicrobials tested against commonly isolated vaginal Lactobacillus spp.

| Lactobacilli spp. |

Antimicrobial agent (μg/mL) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subtilosin | Clindamycin | Polylysine | LAE | |

| L. vaginalis | >100 | 0.78 | 55.8 | 15.63 |

| L. gasseri | >100 | >50 | 111.6 | 31.25 |

| L. plantarum | >100 | 25 | 1786 | 62.5 |

MICs of polylysine and LAE varied greatly among the tested species. Generally, concentrations of these two antimicrobials that were modestly effective against biofilms of G. vaginalis when used alone were also inhibitory to vaginal lactobacilli. Therefore, high concentrations of LAE and polylysine may influence vaginal microbial balance restoration in women affected by BV. However, LAE and polylysine may be used in lower concentrations in combination with synergistically acting agents such as subtilosin.

Previously, subtilosin was shown to have synergistic interactions with polylysine and LAE in inhibiting the growth of G. vaginalis [41]. Due to the major differences in the mode of action of these substances [46, 55, 57], subtilosin, LAE and polylysine are also expected to work synergistically against the biofilms of G. vaginalis when used in combination with each other and, perhaps, with conventional antibiotics. Our future work will focus on the combinatorial effect of these substances on biofilms. However, it is technically challenging to test large number of samples using plate counting. Therefore, we evaluated and compared two simpler methods for the enumeration of viable G. vaginalis cells in antimicrobial-treated biofilms.

3.3. Comparison of ATP Viability and Resazurin Assays to Plate Counting

Patterson et al. [48] reported the use of an ATP viability assay to study biofilms of G. vaginalis. However, to the best of our knowledge the assay has not been validated, for this specific microorganism, against other methods. The assay is rapid and convenient, and it relies on the assumption that the ATP content of a bacterial population is proportional to the number of viable cells [58]. This assumption is generally true for an exponentially-growing bacterial population. However, it is well known that antimicrobials may have very diverse effects on the ATP content of their target cells [28, 57, 59]. Additionally, due to a unique cell wall structure, G. vaginalis is notorious for being difficult to lyse. Therefore it is possible that the lysing component of the assay kit cannot be effectively used to extract ATP from the cells. Cell lysis may be further hindered by the biofilm matrix.

Initially, we used the BacTiter-Glo assay kit to compare the ATP content of intact biofilms with a cell suspension derived from the same biofilms by vigorous pipetting. The estimates of viable cells in intact biofilms and in the derived cell suspension were comparable (data not shown), suggesting that the biofilm matrix does not interfere with the assay. Furthermore, serial dilutions of the biofilm cell suspension had ATP contents proportional to their viable cell counts with a linear range between 103–108 CFU/mL (Figure 4(a)). In contrast, the linear range for resazurin reduction (Figure 4(b)) was rather narrow (between 107-108 CFU/mL). To the best of our knowledge, the use of resazurin assay with G. vaginalis has not been reported.

The ATP viability and resazurin assays generally revealed the same trend as plate counting for the activities of the antimicrobials. However, the actual log reduction estimated by these two methods differed from the numbers obtained by plate counting (Figure 5). One major discrepancy between the methods is the 100-fold reduction in the VCC caused by clindamycin which was not revealed by the ATP viability assay (Figure 5(b)). Clindamycin inhibits protein synthesis [56]. A plausible explanation for the discrepancy is that clindamycin's activity does not necessarily affect the cellular ATP content.

Figure 5.

Viability of G. vaginalis biofilm cells assessed by ATP viability and resazurin assays in comparison to plate counts. ATP viability (open circle) and resazurin assays (closed circle) reveal the same trend as plate counting (closed reverse triangle) for the activities of subtilosin (a), polylysine (c), and LAE (d) but not clindamycin (b). The actual log reduction estimated by these two assays was considerably different from that obtained by plate counting.

The effect of subtilosin was also severely underestimated by the ATP viability assay (Figure 5(a)). This underestimate is probably related to the fact that subtilosin (at its MIC) induces only a mild efflux of ATP (<25%) from cells of G. vaginalis and does not induce intracellular hydrolysis of ATP [57]. Something very similar might be true for other antimicrobials; that is, the antimicrobials may kill their target cells without depleting their ATP, thus giving false negative results in the ATP viability assay and possibly also in the resazurin assay.

It is also important to remember that although plate counting is a well-accepted method for enumerating viable cells, it has certain limitations, especially when used on antimicrobial-treated biofilms. This method is based on the assumption that each viable cell gives rise to a single colony, which may not be true due to cell clumping. Cells derived from biofilms treated with antimicrobials may clump differently than those in untreated biofilms. Additionally, cells injured by antimicrobials might be viable but not culturable (VBNC), which would result in an underestimate using plate counts [60].

Ultimately, the information collected by all three methods complement each other. Both ATP viability and resazurin assays are simple and rapid methods. However, the estimates of viable cells provided by these methods can be significantly different from plate counts. We recommend validating these methods for every new application. Nonetheless, both methods may still be useful for a quick, conservative (compared to plate counting) assessment of antimicrobial activity, especially when numerous samples have to be evaluated at once.

4. Conclusion

Plate counts revealed that at 10x MIC, LAE had the strongest bactericidal effect on biofilmsof G. vaginalis. Subtilosin was slightly less effective, while polylysine and clindamycin induced only a mild reduction in the VCC. Compared to plate counts, ATP viability and resazurine assays can considerably underestimate bactericidal effect of certain antimicrobials against G. vaginalis. Therefore, these assays must be validated for every new application.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Grand Challenges Exploration (Round 5, Phase I Grant OPP1025200 to M. L. Chikindas, Y. Turovskiy, T. Cheryian, and P. J. Sinko) and the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (1R01AI084137 to Y. Turovskiy, M. L. Chikindas, and P. J. Sinko).

References

- 1.Eschenbach DA. History and review of bacterial vaginosis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1993;169(2):441–445. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90337-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sobel JD. Bacterial vaginosis. Annual Review of Medicine. 2000;51:349–356. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.51.1.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forsum U, Holst E, Larsson PG, Vasquez A, Jakobsson T, Mattsby-Baltzer I. Bacterial vaginosis—a microbiological and immunological enigma. Acta Pathologica, Microbiologica et Immunologica Scandinavica. 2005;113(2):81–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2005.apm1130201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larsson PG, Forsum U. Bacterial vaginosis—a disturbed bacterial flora and treatment enigma. Acta Pathologica, Microbiologica et Immunologica Scandinavica. 2005;113(5):305–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2005.apm_113501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.John ES, Mares D, Spear GT. Bacterial vaginosis and host immunity. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2007;4(1):22–28. doi: 10.1007/s11904-007-0004-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Livengood CH. Bacterial vaginosis: an overview for 2009. Reviews in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2009;2(1):28–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eschenbach DA. Vaginitis including bacterial vaginosis. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1994;6(4):389–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eschenbach DA. Bacterial vaginosis and anaerobes in obstetric-gynecologic infection. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1993;16(supplement 4):S282–S287. doi: 10.1093/clinids/16.supplement_4.s282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA. Nonspecific vaginitis. Diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. American Journal of Medicine. 1983;74(1):14–22. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)91112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simoes JA, Hashemi FB, Aroutcheva AA, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 stimulatory activity by Gardnerella vaginalis: relationship to biotypes and other pathogenic characteristics. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2001;184(1):22–27. doi: 10.1086/321002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romero R, Chaiworapongsa T, Kuivaniemi H, Tromp G. Bacterial vaginosis, the inflammatory response and the risk of preterm birth: a role for genetic epidemiology in the prevention of preterm birth. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;190(6):1509–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watts DH, Krohn MA, Hillier SL, Eschenbach DA. Bacterial vaginosis as a risk factor for post-cesarean endometritis. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1990;75(1):52–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmid G, Markowitz L, Joesoef R, Koumans E. Bacterial vaginosis and HIV infection. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2000;76(1):3–4. doi: 10.1136/sti.76.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Romero R, Chaiworapongsa T, Kuivaniemi H, Tromp G. Bacterial vaginosis, the inflammatory response and the risk of preterm birth: a role for genetic epidemiology in the prevention of preterm birth. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;190(6):1509–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oakeshott P, Kerry S, Hay S, Hay P. Bacterial vaginosis and preterm birth: a prospective community-based cohort study. British Journal of General Practice. 2004;54(499):119–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stevens AO, Chauhan SP, Magann EF, et al. Fetal fibronectin and bacterial vaginosis are associated with preterm birth in women who are symptomatic for preterm labor. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;190(6):1582–1589. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watts DH, Krohn MA, Hillier SL, Eschenbach DA. Bacterial vaginosis as a risk factor for post-cesarean endometritis. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1990;75(1):52–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin L, Song J, Kimber N, et al. The role of bacterial vaginosis in infection after major gynecologic surgery. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;7:169–174. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-0997(1999)7:3<169::AID-IDOG10>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atashili J, Poole C, Ndumbe PM, Adimora AA, Smith JS. Bacterial vaginosis and HIV acquisition: a meta-analysis of published studies. AIDS. 2008;22(12):1493–1501. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283021a37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen CR, Lingappa JR, Baeten JM, et al. Bacterial vaginosis associated with increased risk of female-to-male HIV-1 transmission: a prospective cohort analysis among African couples. PLoS Medicine. 2012;9(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001251.e1001251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mascellino MT, Iona E, Iegri F, et al. Evaluation of vaginal microflora in patients infected with HIV. Microbiologica. 1991;14(4):343–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cherpes TL, Melan MA, Kant JA, Cosentino LA, Meyn LA, Hillier SL. Genital tract shedding of herpes simplex virus type 2 in women: effects of hormonal contraception, bacterial vaginosis, and vaginal group B Streptococcus colonization. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2005;40(10):1422–1428. doi: 10.1086/429622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colli E, Landoni M, Parazzini F. Treatment of male partners and recurrence of bacterial vaginosis: a randomised trial. Genitourinary Medicine. 1997;73(4):267–270. doi: 10.1136/sti.73.4.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bannatyne RM, Smith AM. Recurrent bacterial vaginosis and metronidazole resistance in Gardnerella vaginalis. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 1998;74(6):455–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paavonen J, Mangioni C, Martin MA, Wajszczuk CP. Vaginal clindamycin and oral metronidazole for bacterial vaginosis: a randomized trial. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2000;96(2):256–260. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00902-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beigi RH, Austin MN, Meyn LA, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Antimicrobial resistance associated with the treatment of bacterial vaginosis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;191(4):1124–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eriksson K, Carlsson B, Forsum U, Larsson PG. A double-blind treatment study of bacterial vaginosis with normal vaginal lactobacilli after an open treatment with vaginal clindamycin ovules. Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 2005;85(1):42–46. doi: 10.1080/00015550410022249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turovskiy Y, Sutyak Noll K, Chikindas ML. The aetiology of bacterial vaginosis. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2011;110(5):1105–1128. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.04977.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guise JM, Mahon SM, Aickin M, Helfand M, Peipert JF, Westhoff C. Screening for bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2001;20(3):62–72. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00256-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hay P. Life in the littoral zone: lactobacilli losing the plot. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2005;81(2):100–102. doi: 10.1136/sti.2003.007161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwiertz A, Taras D, Rusch K, Rusch V. Throwing the dice for the diagnosis of vaginal complaints? Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials. 2006;5, article 4 doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-5-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwebke JR, Rivers C, Lee J. Prevalence of Gardnerella vaginalis in male sexual partners of women with and without bacterial vaginosis. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2009;36(2):92–94. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181886727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klebanoff MA, Andrews WW, Zhang J, et al. Race of male sex partners and occurrence of bacterial vaginosis. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2010;37(3):184–190. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181c04865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Catlin BW. Gardnerella vaginalis: characteristics, clinical considerations, and controversies. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 1992;5(3):213–237. doi: 10.1128/cmr.5.3.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gardner HL, Dukes CD. Haemophilus vaginalis vaginitis. A newly defined specific infection previously classified "nonspecific" vaginitis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1955;69(5):962–976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ling Z, Kong J, Liu F, et al. Molecular analysis of the diversity of vaginal microbiota associated with bacterial vaginosis. BMC Genomics. 2010;11(1, article 488) doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swidsinski A, Mendling W, Loening-Baucke V, et al. Adherent biofilms in bacterial vaginosis. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;106(5):1013–1023. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183594.45524.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patterson JL, Stull-Lane A, Girerd PH, Jefferson KK. Analysis of adherence, biofilm formation and cytotoxicity suggests a greater virulence potential of Gardnerella vaginalis relative to other bacterial-vaginosis-associated anaerobes. Microbiology. 2010;156(2):392–399. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.034280-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swidsinski A, Mendling W, Loening-Baucke V, et al. An adherent Gardnerella vaginalis biofilm persists on the vaginal epithelium after standard therapy with oral metronidazole. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;198(1):97.e1–97.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aroutcheva A, Simoes JA, Shott S, Faro S. The inhibitory effect of clindamycin on Lactobacillus in vitro. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001;9(4):239–244. doi: 10.1155/S1064744901000394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sutyak Noll K, Prichard MN, Khaykin A, Sinko PJ, Chikindas ML. The natural antimicrobial peptide subtilosin acts synergistically with glycerol monolaurate, lauric arginate and ε-poly-L-lysine against bacterial vaginosis-associated pathogens but not human lactobacilli. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2012;56(4):1756–1761. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05861-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sutyak KE, Wirawan RE, Aroutcheva AA, Chikindas ML. Isolation of the Bacillus subtilis antimicrobial peptide subtilosin from the dairy product-derived Bacillus amyloliquefaciens. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2008;104(4):1067–1074. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03626.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nishikawa M, Ogawa K. Inhibition of epsilon-poly-L-lysine biosynthesis in Streptomycetaceae bacteria by short-chain polyols. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2006;72(4):2306–2312. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2306-2312.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hiraki J, Ichikawa T, Ninomiya SI, et al. Use of ADME studies to confirm the safety of ε-polylysine as a preservative in food. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 2003;37(2):328–340. doi: 10.1016/s0273-2300(03)00029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoshida T, Nagasawa T. ε-poly-L-lysine: microbial production, biodegradation and application potential. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2003;62(1):21–26. doi: 10.1007/s00253-003-1312-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodríguez E, Seguer J, Rocabayera X, Manresa A. Cellular effects of monohydrochloride of L-arginine, Nα- lauroyl ethylester (LAE) on exposure to Salmonella typhimurium and Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2004;96(5):903–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tabak M, Scher K, Hartog E, et al. Effect of triclosan on Salmonella typhimurium at different growth stages and in biofilms. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2007;267(2):200–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patterson JL, Girerd PH, Karjane NW, Jefferson KK. Effect of biofilm phenotype on resistance of Gardnerella vaginalis to hydrogen peroxide and lactic acid. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;197(2):170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martens MG, Faro S, Maccato M, Riddle G, Hammill HA. Susceptibility of female pelvic pathogens to oral antibiotic agents in patients who develop postpartum endometritis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1991;164(5):1383–1386. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)91477-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hoben HJ, Somasegaran P. Comparison of the pour, spread, and drop plate methods for enumeration of Rhizobium spp. in inoculants made from presterilized peat. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1982;44(5):1246–1247. doi: 10.1128/aem.44.5.1246-1247.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Herigstad B, Hamilton M, Heersink J. How to optimize the drop plate method for enumerating bacteria. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 2001;44(2):121–129. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(00)00241-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Extremina CI, Costa L, Aguiar AI, Peixe L, Fonseca AP. Optimization of processing conditions for the quantification of enterococci biofilms using microtitre-plates. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 2011;84(2):167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pettit RK, Weber CA, Kean MJ, et al. Microplate alamar blue assay for Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm susceptibility testing. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2005;49(7):2612–2617. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.7.2612-2617.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Turovskiy Y, Ludescher RD, Aroutcheva AA, Faro S, Chikindas ML. Lactocin 160, a bacteriocin produced by vaginal Lactobacillus rhamnosus, targets cytoplasmic membranes of the vaginal pathogen, Gardnerella vaginalis. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins. 2009;1(1):67–74. doi: 10.1007/s12602-008-9003-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shima S, Matsuoka H, Iwamoto T, Sakai H. Antimicrobial action of poly-L-lysine. Journal of Antibiotics. 1984;37(11):1449–1455. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.37.1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chambers HF. Bactericidal vs. bacteriostatic antibiotic therapy: a clinical mini-review. Clinical Updates in Infectious Diseases. 2003;6(1):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Noll KS, Sinko PJ, Chikindas ML. Elucidation of the molecular mechanisms of action of the natural antimicrobial peptide subtilosin against the bacterial vaginosis-associated pathogen Gardnerella vaginalis. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins. 2011;3(1):41–47. doi: 10.1007/s12602-010-9061-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. BacTiter-Glo Microbial Cell Viability Assay: Technical bulletin, http://www.promega.com/~/media/Files/Resources/Protocols/Technical%20Bulletins/101/BacTiter-Glo%20Microbial%20Cell%20Viability%20Assay%20Protocol.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bonnet M, Rafi MM, Chikindas ML, Montville TJ. Bioenergetic mechanism for nisin resistance, induced by the acid tolerance response of Listeria monocytogenes. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2006;72(4):2556–2563. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2556-2563.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Trevors JT. Viable but non-culturable (VBNC) bacteria: gene expression in planktonic and biofilm cells. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 2011;86(2):266–273. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]