Abstract

Background

We report the 10-year results of the EORTC trial 24891 comparing a larynx-preservation approach to immediate surgery in hypopharynx and lateral epilarynx squamous cell carcinoma.

Material and methods

Two hundred and two patients were randomized to either the surgical approach (total laryngectomy with partial pharyngectomy and neck dissection, followed by irradiation) or to the chemotherapy arm up to three cycles of induction chemotherapy (cisplatin 100 mg/m2 day 1 + 5-FU 1000 mg/m2 day 1–5) followed for complete responders by irradiation and otherwise by conventional treatment. The end points were overall survival [OS, noninferiority: hazard ratio (preservation/surgery) ≤ 1.428, one-sided α = 0.05], progression-free survival (PFS) and survival with a functional larynx (SFL).

Results

At a median follow-up of 10.5 years on 194 eligible patients, disease evolution was seen in 54 and 49 patients in the surgery and chemotherapy arm, respectively, and 81 and 83 patients had died. The 10-year OS rate was 13.8% in the surgery arm and 13.1% in the chemotherapy arm. The 10-year PFS rates were 8.5% and 10.8%, respectively. In the chemotherapy arm, the 10-year SFL rate was 8.7%.

Conclusion

This strategy did not compromise disease control or survival (that remained poor) and allowed more than half of the survivors to retain their larynx.

Keywords: chemotherapy, hypopharynx, larynx preservation, radiotherapy, surgery

introduction

The advent of the cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil (CF) regimen in the early 80s shifted many paradigms in the management of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), especially for advanced laryngopharyngeal SCC. At that time, these indications were treated either by surgery (total laryngectomy and neck dissection) with postoperative radiotherapy (RT) or by definitive RT with possible salvage surgery. These two approaches had never been randomly compared. The CF regimen achieved impressive response rates [1, 2] and chemosensititive tumors appeared to be radiosensitive as well [3]. Consequently, induction chemotherapy (ICT) was envisaged as a means of selecting patients (who would otherwise have undergone total laryngectomy) for a larynx-preservation approach with RT. If many teams initiated this research for laryngeal SCC, it was less for hypopharynx SCC because of the often poor performance status of these patients and because salvage surgery was reputed more morbid for this primary site. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Head and Neck Cancer Group launched a randomized phase III trial to test if ‘larynx preservation with ICT was safe in hypopharynx SCC’ (EORTC 24891). First results were published in 1996 [4], we now present 10-year follow-up results.

patients and methods

Patient selection criteria are detailed in supplemental Table S1 (available at Annals of Oncology online). Informed consent was required according to the local regulations. Ethical committee approval was obtained in all centers. This study is registered on Physician Data Query® (protocol search id = 7804219).

treatment

ICT consisted of cisplatin (100 mg/m2 i.v. infusion) after an i.v. bolus of 12.5 g of mannitol in 1 l of 5% dextrose in 0.45% NaCl with 30 mmEq of KCl. The 5-fluorouracil infusion was started with 1000 mg/m2/day in 2 l of 5% dextrose in 0.45% NaCl infusion over 5 days. Response to CT (assessed by World Health Organization [6] and reported earlier [4]) was clinically evaluated by endoscopy before each cycle. Lymph node(s) was assessed separately by clinical examination and palpation. The treatment flowchart is described supplemental Figure S1 (available at Annals of Oncology online).

All patients had to receive two-dimensional external irradiation (RT) either postoperatively or immediately after ICT in case of complete response. The irradiated volumes included the primary site and both sides of the neck. Patients were irradiated in a supine position with megavoltage equipment using a conventional fractionation (1 fraction of 2 Gy/day, 5 days/week). The dose for definitive RT after ICT was 50 Gy followed by a booster dose of 20 Gy on the tumor site and palpable lymph node(s), if present. The postoperative RT dose was 50 Gy intended to the entire remaining pharynx, both sides of the neck and the tracheostomy. An additional booster dose of 14 Gy was given to sites of positive margins and/or of extracapsular spread and/or of three or more positive lymph nodes, if any. The spinal cord had to be shielded at 40 Gy and electrons were used to complete the RT of the posterior part of the neck.

Surgery had to take place at least 3 weeks after ICT. Surgery per protocol (immediate or after ICT) consisted in total laryngectomy with partial pharyngectomy allowing a primary closure without any kind of flap. The excision margins were determined by the tumor extent before CT, as documented at the initial examination conducted under general anesthesia. The type of neck dissection was dictated by the clinical node status.

statistical methods

Randomization was centrally carried out at the EORTC Headquarters by minimization with parameters institution, tumor size (T2 versus T3–T4), nodal status (N0–N1 versus N2–N3) [5] and site (piriform sinus versus aryepiglottic fold) [7].

The trial design was detailed in the original publication [4] and supplemental Table S2 (available at Annals of Oncology online). Overall survival (OS) was the primary end point of this noninferiority trial with noninferiority defined as mortality hazard ratio (HR) ≤ 1.43 for the CT arm at the one-sided α = 0.05. Event-free rates were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier technique and compared by log-rank test or log-rank test for noninferiority (OS) [8, 9]. Confidence intervals (CIs) are presented at the two-sided 95% confidence level.

results

A total of 202 patients were enrolled in the study (99 in the surgery arm and 103 in the CT arm). A total of 194 eligible patients with follow-up are included in this final analysis (94 in the surgery arm and 100 in the CT arm). Six patients ineligible due to inadequate disease status (four in the surgery arm and two in the CT arm) and two patients without any follow-up (one per arm) are excluded. At currently 10.5 years median follow-up, 164 of 194 patients (84.6%) have died compared with 116 in the first report [4].

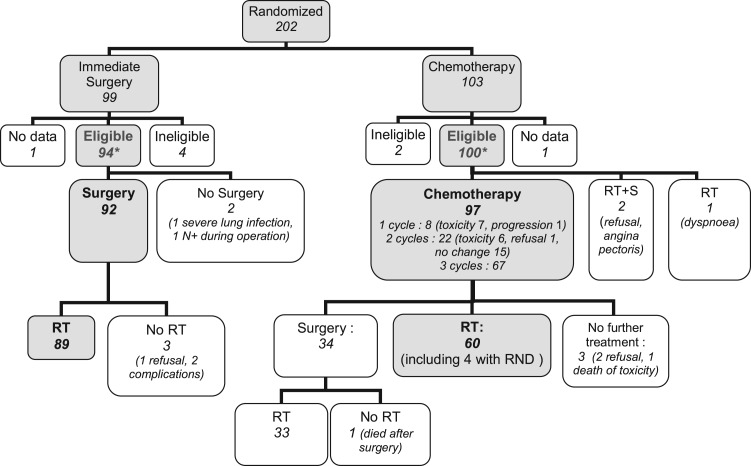

The baseline characteristics were well balanced between the two arms (Table 1 and supplemental Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online) and represent of a classical population of hypopharyngeal cancer. Protocol compliance is summarized in Figure 1 and was reported earlier [4].

Table 1.

Patient's characteristics at randomization

| Characteristics | Surgery, n = 94 (%) | Chemotherapy, n = 100 (%) | All, n = 194 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 92 (98) | 94 (94) | 186 (96) |

| Male | |||

| Female | 2 (2) | 6 (6) | 8 (4) |

| Age (years) | |||

| Median | 54.5 | 56.3 | 55.6 |

| Range | 35.8–70.3 | 37.9–70.4 | 35.8–70.4 |

| Site | |||

| Pyriform sinus | 74 (79) | 78 (78) | 152 (78) |

| Aryepiglottic fold | 20 (21) | 22 (22) | 42 (22) |

| World Health Organization performance status | |||

| 0 | 85 (90) | 94 (94) | 179 (92) |

| 1 | 7 (8) | 5 (5) | 12 (6) |

| 2 | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 3 (2) |

| Stage [5] | |||

| II | 6 (6) | 7 (7) | 13 (6) |

| III | 51 (54) | 59 (59) | 110 (57) |

| IV | 37 (39) | 34 (34) | 71 (37) |

Figure 1.

Study flowchart. o is the number of events; n is the number of patients. *Included in the primary analysis. CT, chemotherapy; RT, external beam radiotherapy; S, surgery.

At 10.5 years median follow-up, 8 patients in the surgery arm had experienced a local, 15 a regional and 5 a locoregional failure. In the CT arm, 8 experienced a local, 12 a regional and 12 a locoregional failure. In the surgery and CT arms, respectively, 34 and 38 patients experienced distant failure (isolated in 26 and 17). In total 54 patients (57.4%) in the surgery arm and 49 patients (49.0%) in the CT arm developed at least one event during the follow-up (Table 2).

Table 2.

Pattern of failure

| Sites of failurea last failure (%) | Surgery arm (n = 94) |

Chemotherapy arm (n = 100) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial number of failures (n) | Number salvaged | Ultimateb number of failures, n (%) | Initial number of failures (n) | Number salvaged | Ultimateb number of failures, n (%) | |

| Local | 13 | 2 | 11 (11.7) | 20 | 6 | 14 (14.0) |

| Regional | 20 | 2 | 18 (19.1) | 24 | 5 | 19 (19.0) |

| Distant | 34 | 0 | 34 (36.2) | 28 | 0 | 28 (28.0) |

aIsolated or associated to another one.

bAs stated at the last examination.

Of 12 patients with a local failure in the surgery arm, 5 were treated by CT and 1 by reirradiation (and was controlled), 1 had tracheotomy alone, 1 had iterative laser CO2 desobstruction, 2 had salvage surgery (successful in 1) and 2 had only supportive care. Of 20 patients with local failure in the CT arm, 4 received CT; 2 were reirradiated and one had chemoradiation (0/7 were controlled); 10 patients had salvage surgery (successful in 6); 2 received supportive care, one is undocumented. Thus ultimately, the primary site could not be controlled for 11 patients in the surgery arm and 14 in the CT arm.

Of the 20 patients with regional failures in the surgery arm, 8 had no treatment, 7 had CT, 2 had reirradiation and 1 had tracheotomy alone (0/15 were controlled); and 2 patients had salvage surgery (successful in both). Of the 24 patients with regional failure in the CT arm, 5 had no treatment, 6 had CT alone and 6 were reirradiated (0/12 controlled); 7 patients had salvage surgery (successful in 5). Thus, 18 patients in the surgery arm and 19 in the CT arm could ultimately not be controlled in the neck.

None of the patients who developed distant metastases were controlled.

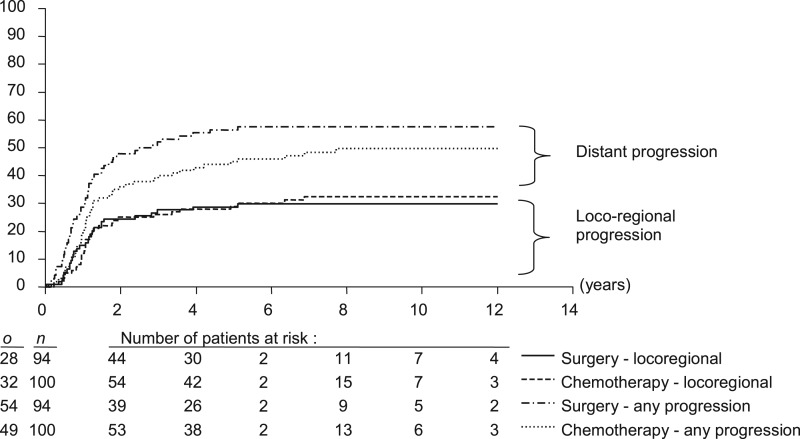

There was no significant difference in the cumulative incidence of first progression (Figure 2; P = 0.13), locoregional failures (Figure 2; P = 0.84) or distant metastases (P = 0.14).

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of first progression. o is the number of events; n is the number of patients.

In the surgery arm, 2 of the 13 patients with an isolated local relapse had salvage surgery (1 glossopharyngectomy with major pectoralis myocutaneous flap for a recurrence on the base of tongue at month 14 and 1 pharyngoesophagectomy with gastric pull-up for a recurrence on the pharyngoesophageal junction at month 18). Postoperative courses were satisfactory and surgical margins were free in both cases. Only the patient with the oropharyngeal recurrence could be controlled (and died of a second tumor 7 years later) while the second patient died of an extensive regional evolution 4 months after surgery. Two more patients had salvage neck surgery for an isolated regional recurrence at respectively 2 and 4 years of follow-up (the first with a major pectoralis myocutaneous flap and the second with a parotidectomy) without postoperative complication or further regional evolution (the first patient died of a second cancer 2 years later and the other patient was still alive).

In the CT arm, 10 of the 20 patients with a local relapse had salvage surgery. Of them, 8 patients had surgery for a local recurrence alone (at a 6-month follow-up in 1 case, at a 1-year follow-up in 2 cases, at a 2-year follow-up in 2 cases and at 3, 5 and 7 years for the other patients). Surgery consisted of a total laryngectomy with a partial pharyngectomy in seven cases (with elective neck dissection in five cases) while the last patient had a circumferential pharyngolaryngectomy with esophagectomy, neck dissection and coloplasty. One patient presented an extensive skin necrosis and died postoperatively and another one had a fistula. Surgical margins were satisfactory in seven cases but for the patient who required an esophagectomy, margins were positive (he died of locoregional evolution 6 months later). Only one patient had positive lymph nodes (he died 3 years later of a regional evolution). One patient was still alive. One patient died of a new local evolution with regional recurrence and distant metastases in the lung 1 year after salvage surgery and died, one patient died of regional evolution 1 year after surgery, one patient died of a second primary tumor 2 years later and another one of distant metastases 3 years later. Two patients had a locoregional evolution and underwent a total laryngectomy with partial pharyngectomy and neck dissection. Both presented a skin necrosis. One had positive margins and positive lymph nodes and died of disease 3 months later; one had negative margins and positive lymph nodes and died of brain metastases 1 year later. Finally, five of the patients who had a regional recurrence alone (occurring at 4 months, 6 months, 1 year, 5 years and 6 years) had salvage neck dissection. There was no postoperative complication. All five patients died (one at 4 months from a new nodal evolution, one at 2 years from distant metastases, one at 2 years of a second primary tumor, one at 3 years of a local evolution and one at 13 years of unknown cause).

A total of 81 patients in the surgery arm and 83 in the CT arm have died. In the surgery arm, 41 patients died of the index primary tumor evolution and 21 of a second primary cancer, 11 patients of another disease without cancer evolution and 8 of an unknown cause.

In the CT arm, 41 patients died of the index primary tumor evolution and 15 of a second primary cancer, 1 patient died of ICT-related toxicity, another patient died postoperatively after salvage surgery for local recurrence, 17 died of another disease without any cancer evolution and 10 of an unknown cause.

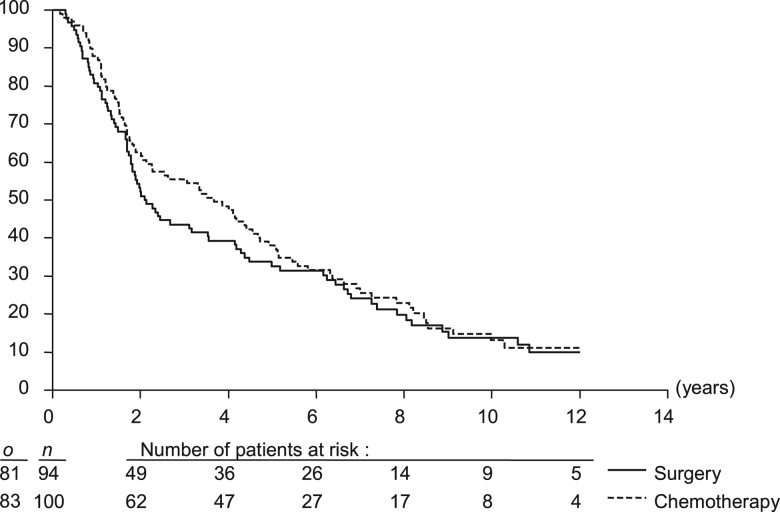

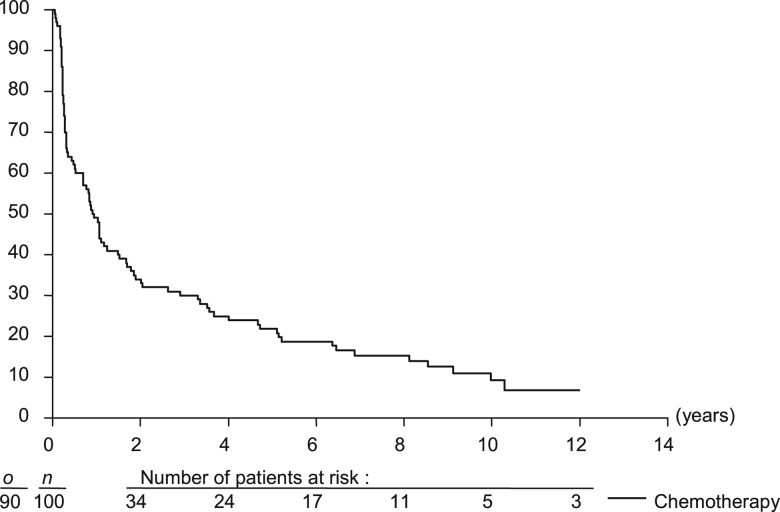

The median OS was 2.1 years (95% CI 1.8–4.2) in the surgery arm and 3.7 years (95% CI 2.3–4.7) in the CT arm [HR = 0.88 favoring the CT arm (95% CI 0.65–1.19)], demonstrating the noninferiority of the CT arm (noninferiority: P = 0.002; Figure 3; Table 3). The 5- and 10-year OS rates were 32.6% (95% CI 23.0% to 42.1%) and 13.8% (95% CI 6.1% to 21.6%) in the surgery arm and 38.0% (95% CI 28.4% to 47.6%) and 13.1% (95% CI 5.6% to 20.6%) in the CT arm, respectively.

Figure 3.

Overall survival. o is the number of events; n is the number of patients.

Table 3.

Overall and progression-free survival

| Surgery arm | Chemotherapy arm | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall survival | ||

| Median (95% CI) | 2.1 years (1.8–4.2) | 3.67 years (2.3–4.7) |

| 5-year survival rate (95% CI) | 32.6% (23.0–42.1) | 38.0% (28.4–47.6) |

| 10-year survival rate (95% CI) | 13.8% (6.1–21.6) | 13.1% (5.6–20.6) |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 0.88 (0.65–1.19) | |

| Progression-free survival | ||

| Median (95% CI) | 1.6 years (1.2–2.4) | 2.1 years (1.4–3.6) |

| 5-year event-free rate (95% CI) | 26.4% (17.5–35.4) | 31.7% (22.5–40.9) |

| 10-year event-free rate (95% CI) | 8.5% (2.0–15.0) | 10.8% (3.8–17.9) |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Reference group | 081 (0.60–1.09) |

| Progression-free survival (including second cancer as event) | ||

| Median (95% CI) | 1.4 years (1.1–2.1) | 1.8 years (1.3–3.0) |

| 5-year event-free rate (95% CI) | 24.1% (15.4–32.9) | 26.8% (18.1–35.5) |

| 10-year event-free rate (95% CI) | 6.7% (1.2–12.1) | 8.6% (2.3–14.9) |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Reference group | 0.83 (0.62–1.12) |

CI, confidence interval.

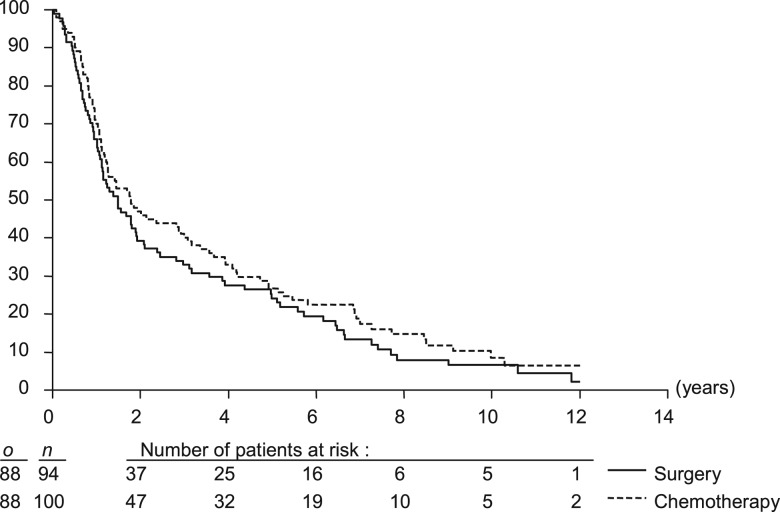

The CT arm provided similar progression-free survival as the surgery arm, irrespective, if deaths of second cancer were included (Figure 4) or not (Table 3) with HR of 0.83 (95% CI 0.62–1.12) and 0.81 (95% CI 0.60–1.09), respectively.

Figure 4.

Progression-free survival (time to locoregional or distant recurrence, second cancer or death of any cause). o is the number of events; n is the number of patients.

In the CT arm, survival with preserved larynx was defined as survival without local disease evolution, tracheotomy nor feeding tube. The 5- and 10-year rates of survival with preserved larynx were 21.9% (95% CI 13.7% to 30.0%) and 8.7% (95% CI 2.5% to 16.1%; Figure 5), respectively. In other words, 22 of 37 (59.5%) patients alive at 5 years and 5 of 8 patients alive at 10 years had retained a normal larynx. When deaths not due to uncontrolled local evolution and with preserved larynx were censored in the analysis, 5- and 10-year disease-specific survival rates with preserved larynx were 40.5% and 26.97%, respectively.

Figure 5.

Larynx preservation [survival with preserved larynx; i.e. without local evolution or tracheotomy or feeding tube (i.e. larynx function preservation and local control)]. o is the number of events; n is the number of patients.

discussion

This final analysis confirmed the preliminary results published in 1996 [4] except for the median survival which was significantly longer in the experimental arm: 44 versus 25 months in the surgical arm, in the first analysis. The OS difference disappeared with a longer follow-up mainly due to the appearance of distant metastases (36%) which was delayed in the CT arm. This led to an OS similar in both groups: ∼33% at 5 years and 13% at 10 years. If the surgery was mutilating (removal of the entire voice box), it also provided a local control of 86% (Table 3).

The excess of cancer-unrelated/unknown deaths observed in the experimental arm is another matter of concern. It emphasizes the need for a careful and prolonged follow-up in order to detect the impact of comorbidities and to diminish the number of unknown reasons of death which preclude a clear interpretation of the phenomenon.

In the experimental arm, CT was quite well tolerated: 14 patients had limiting toxic effects (14%), one of them was lethal. After CT, slightly over half of the patients (54%) had a complete response at the primary site and in the neck (51%), for a total of 43% of patients free of disease above the clavicles. For patients who had to undergo surgery due to an incomplete response to CT, the quality of the surgical resection was not compromised with the same rate of negative margins (95%). Conversely, the postoperative course did not differ as the median time to wound healing was similar in both arms and postoperative irradiation was equally tolerated. For patients who underwent irradiation after CT, there was no increased toxicity. Of the 20 patients who relapsed locally, 10 were treated by salvage surgery and 6 were controlled leading to an ultimate local control similar in both arms. If the median survival was significantly longer in the CT arm, the 5-year and 10-year OS did not differ between both arms, but remained poor for this primary site (33% and 13%, respectively). Of interest, more than half of the survivors in the CT arm retained a functional larynx.

Larynx preservation based on a selection of patients with ICT appeared safe and efficient in this trial.

It should be noted that the protocol was designed and conducted many years ago, using two-dimensional RT based on direct simulation procedures, which is not the current standard anymore. Based on a number of randomized controlled trials, intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) should be considered as gold standard and this technique is increasingly used in head and neck RT, leading to a significant reduction of radiation-induced xerostomia without compromising locoregional control [10–12]. Moreover, recent studies on intensity modulated radiotherapy showed excellent locoregional control rates compared to historical reports using more conventional radiation techniques [13]. Therefore, we do not expect that the results found in the experimental arm of the current study will be hampered when IMRT is used instead of two-dimensional RT.

The publication of several trials on concurrent chemoirradiation and in particular the publication of the large MACH-NC meta-analysis and its update [14, 15] have shown a significant improvement of survival after radiation given concomitantly with CT. Concurrent chemoirradiation become the logical next step in clinical research for larynx preservation.

To date, a single randomized trial on larynx preservation with concurrent CT has been published for laryngeal SCC only (RTOG 91-11) [16]. It showed a significant higher 2-year preservation rate in the concurrent arm (84%) but no impact on survival (74%). A more recent update, showed a 5-year larynx-preservation rate of 83.6%, with a similar survival in all groups of treatment (54%) [17]. Of importance, the mucosal toxicity was significantly increased in this arm.

The EORTC had conducted a randomized trial for larynx and hypopharynx SCC comparing ICT (cisplatin and 5-FU) versus alternating chemoradiation for larynx preservation (EORTC 24954) [18]. The 3-year and 5-year rates of survival with a functional larynx (the primary end point) were statistically similar in both arms: 39.5% and 30.5% in the sequential arm versus 45.4% and 36.2% in the alternating arm, respectively. Acute toxic effects were statistically significantly higher in the sequential arm than in the alternating arm (all P < 0.001); in contrast, late severe edema and/or fibrosis were similar in both arms (16% versus 11% in sequential as alternating arms, respectively).

More recently, a randomized trial of patients who would have required total laryngectomy for laryngeal or hypopharyngeal SCC compared two ICT regimens: TPF (docetaxel added to cisplatin and 5-FU) versus PF (three cycles) before radiation in order to preserve the larynx [19]. The overall response rate was superior in the TPF group (80.0% versus 59.2%) leading to a higher 3-year actuarial larynx-preservation rate of 70.3% (versus 57.3% in the PF group), but without difference in terms of survival. Patients in the TPF group experienced more grade 3–4 neutropenia and infections, whereas the PTS in the PF group experienced more grade 3–4 stomatitis and thrombocytopenia. Late grade 4 larynx toxicity occurred in 6.2% versus 13.6% in patients of the TPF and PF groups, respectively [19].

Acute toxicity of new protocols is a real concern in clinical trials (selected populations of patients) and even more in daily practice (unselected populations of patients). Toxicity in patients with usually a poor performance status compromises the tolerance and compliance to treatment. It causes treatment interruptions that ultimately compromise treatment efficacy. Late toxicity may compromise the reliability and feasibility of salvage surgery.

Another trial that compared irradiation and a monoclonal antibody targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (cetuximab) to irradiation alone showed an improved survival and locoregional control while the grade 3–4 mucositis rates ware similar in both arms [20]. A specific analysis of the subset of patients with laryngeal SCC in that trial concluded to a trend (non significant) for an increased larynx-preservation rate with the addition of cetuximab [21]. Currently, trials are conducted to assess ICT followed by concurrent chemoirradiation in good responders and the place of targeted therapies in larynx preservation.

This first randomized trial on ICT for larynx preservation in advanced but resectable hypopharyngeal cancer has shown the feasibility and safety of this approach. Neither RT nor surgery has been compromised and the OS was similar to that achieved with surgery and postoperative irradiation. But if the OS could not be improved, more than half of the patients retained their larynx.

funding

This publication was supported by grants number (5U10-CA11488-18S2) through (5U10-CA11488-38) from the National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD).

disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Ligue Française Contre le Cancer for providing support for this research project. Role of the funding source: The EORTC was the sponsor of the trial. All trial development and trial management activities and statistical analyses were conducted at the EORTC Headquarters (Brussels, Belgium) in total independence of the funding source. The funding bodies had also no role in the interpretation of the results nor in writing the manuscript. Participating institutions: The following principal investigators and institutions, listed according to accrual of patients, participated in this EORTC Head and Neck Cancer Cooperative Group Study: JLL, MD, Study Coordinator (Centre Oscar Lambret, Lille, France); DC, MD (Hôpital Claude Huriez, Lille, France); BL, MD (Institut Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France); LT, MD (Hôpital Pellegrin, Bordeaux, France); GA, MD (Institut Jules Bordet, Brussels, Belgium); Jean-Pierre Rame, MD (Centre Francois Baclesse, Caen, France); Silvino Crispino, MD (Ospedale San Gerardo, Monza, Italy); Cesare Chiamenti, MD (Ospedale Verona, Italy); JMH van den Beek, MD (University Hospital, Maastricht, The Netherlands); Jean-Marie David, MD (Centre Claudius Regaud, Toulouse, France) and Jacques Bernier, MD (Ospedale San Giovanni, Bellinzona, Switzerland). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute.

references

- 1.Weaver A, Flemming S, Kish J, et al. Cis-platinum and 5-fluorouracil as induction therapy for advanced head and neck cancer. Am J Surg. 1982;144(4):445–448. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(82)90419-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kish J, Drelichman A, Jacobs J, et al. Clinical trial of cisplatin and 5-FU infusion as initial treatment for advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer Treat Rep. 1982;66(3):471–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ensley JF, Jacobs JR, Weaver A, et al. Correlation between response to cisplatinum-combination chemotherapy and subsequent radiotherapy in previously untreated patients with advanced squamous cell cancers of the head and neck. Cancer. 1984;54(5):811–814. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840901)54:5<811::aid-cncr2820540508>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lefebvre JL, Chevalier D, Luboinski B, et al. Larynx preservation in pyriform sinus cancer: preliminary results of a European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer phase III trial. EORTC Head and Neck Cancer Cooperative Group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88(13):890–899. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.13.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Joint Committee on Cancer. TNM, Manual for Staging of Cancer. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. WHO Handbook for Reporting Results of Cancer Treatment. Geneva, Switzerland: Offset Publication; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pocock SJ, Simon R. Sequential treatment assignment with balancing for prognostic factors in the controlled clinical trial. Biometrics. 1975;31(1):103–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Com-Nougue C, Rodary C, Patte C. How to establish equivalence when data are censored: a randomized trial of treatments for B non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Stat Med. 1993;12(14):1353–1364. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780121407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mantel N. Evaluation of survival data and two new rank order statistics arising in its consideration. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1966;50(3):163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nutting CM, Morden JP, Harrington KJ, et al. PARSPORT trial management group. Parotid-sparing intensity modulated versus conventional radiotherapy in head and neck cancer (PARSPORT): a phase 3 multicentre randomized controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(2):127–136. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70290-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pow EH, Kwong DL, McMillan AS, et al. Xerostomia and quality of life after intensity-modulated radiotherapy vs. conventional radiotherapy for early-stage nasopharyngeal carcinoma: initial report on a randomized controlled clinical trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66(4):981–991. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kam MK, Leung SF, Zee B, et al. Prospective randomized study of intensity-modulated radiotherapy on salivary gland function in early-stage nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. J Clin Onol. 2007;25(31):4873–4879. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daly ME, Le QT, Jain AK, et al. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy for locally advanced cancers of the larynx and hypopharynx. Head Neck. 2011;33(1):103–111. doi: 10.1002/hed.21406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pignon JP, Bourhis J, Domenge C, Designe L. Chemotherapy added to locoregional treatment for head and neck squamous-cell carcinoma: three meta-analyses of updated individual data. MACH-NC Collaborative Group. Meta-Analysis of Chemotherapy on Head and Neck Cancer. Lancet. 2000;355(9208):949–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bourhis J, Armand C, Pignon JP. In ASCO Annual Meeting of the Journal of Clinical Oncology (Abstr 5505) New Orleans, LA: 2004. Update of the MACH-NC (Meta-Analysis of Chemotherapy in Head & Neck Cancer) database focused on concomitant chemoradiotherapy. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forastiere AA, Goepfert H, et al. Concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy for organ preservation in advanced laryngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(22):2091–2098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forastière AA, Maor M, Weber RS, et al. Long-term results of Intergroup RTOG 91–11: a phase III trial to preserve the larynx–induction cisplatin/5-FU and radiation therapy versus concurrent cisplatin and radiation therapy versus radiation therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(18S):5517. In 2006 ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings Part I. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lefebvre JL, Rolland F, Tesselaar M, et al. for the EORTC Head and Neck Cancer Cooperative Group and the EORTC Radiation Oncology Group. Phase 3 randomized trial on larynx preservation comparing sequential vs alternating chemotherapy and radiotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:142–152. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pointreau Y, Garaud P, Chapet S, et al. Randomized trial of induction chemotherapy with cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil with or without docetaxel for larynx preservation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:498–506. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonner J, Giralt J, Harari P, et al. In ASCO Annual Meeting (Abstr 5507) 2004. Cetuximab prolongs survival in patients with locoregionally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: a phase III study of high dose radiation therapy with or without cetuximab. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonner J, Harari P, Giralt J, et al. In ASCO Annual Meeting (Abstr 5533) 2005. Improved preservation of the larynx with the addition of cetuximab to radiation for cancers of the larynx and hypopharynx. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.