Social media is a powerful and potentially useful tool in oncology and other clinical specialties, but it raises ethical challenges and can have harmful consequences if not used wisely.

Abstract

Online social networking has replaced more traditional methods of personal and professional communication in many segments of society today. The wide reach and immediacy of social media facilitate dissemination of knowledge in advocacy and cancer education, but the usefulness of social media in personal relationships between patients and providers is still unclear. Although professional guidelines regarding e-mail communication may be relevant to social media, the inherent openness in social networks creates potential boundary and privacy issues in the provider-patient context. This commentary seeks to increase provider awareness of unique issues and challenges raised by the integration of social networking into oncology communications.

Case Study

The day's work is done. Time to steal a few minutes at home online to catch up with Facebook friends. A safe haven from the difficulties of an oncology practice? Perhaps not. Tonight, a friend request from the mother of a former patient causes me to ponder the delicate boundary issues of my job. It has been a while since I have heard from this family. I think, “Is she okay? How is the family coping?” It seems a post on a colleague's wall led her to reach out to me. Does ignoring the request give the wrong signal? Even if I might have concerns, she could infer that my institution does not prohibit such interaction, because my colleague has already friended her.

Today's oncology practitioner is likely to peruse or be actively involved in social media such as blogging, social networks (eg, Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn), private Web sites for people experiencing significant health challenges (eg, Caring Bridge), or multimedia sharing (eg, YouTube). The interactions may be intended as solely professional or personal venues. However, increased usage of these forms of social media is making it progressively more difficult to maintain clear professional boundaries. A study of more than 400 trainees in France found most young physicians had Facebook profiles displaying enough personal information to be identified,1 including name and date of birth, and, in 91% of cases, a personal photo. Although 85% said they would automatically refuse a patient's friend request, 15% would decide on a case-by-case basis. Reasons for accepting a friend request included feeling an affinity with the patient and fear of embarrassing, upsetting, or losing the patient if they declined. Similarly, a study conducted at a US university comparing Facebook use from 2007 to 2009 among physicians in training found participation and disclosure of personal information had significantly increased over time.2

Defining Professional Boundaries

Many variables influence how one defines appropriate professional boundaries within oncology settings. These may include the care environment, community characteristics, patient needs, nature of therapy, patient and practitioner age, and intensity of clinical involvement.3 Patients and families facing a health crisis or impending death may desire to deepen the attachment with their physician, who is then challenged to convey a caring, concerned attitude while remaining objective.4 Spending time with family members, learning family history and values, and addressing day-to-day symptoms can lead to relationships that resemble pseudofamilies.5 Such closeness can be comforting for both practitioners and patients but can also put pressure on professional limits or boundaries, such as with friend requests, and result in differences of opinion among staff as to where appropriate boundaries lie.

Potential Risks of Social Media

Legal and Ethical Considerations

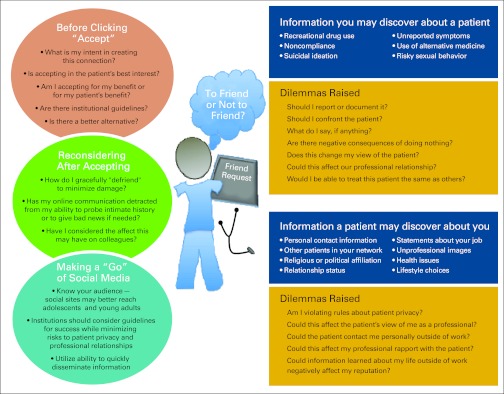

Legal questions surrounding the use of social media in clinical medicine are also evolving. Although online postings may seem innocuous (eg, “tough day, one relapse, hormonal nurse, many meetings—happy hour tonight”), caregivers risk having their opinions viewed by a wider audience than intended.6 Online posts can potentially violate the privacy rights of patients, colleagues, or faculty as well as misrepresent an institution or damage its credibility.7 Medical students have been dismissed and at least one physician has lost his malpractice case because of inappropriate online posts.8,9 The oncologist may discover personal information about a patient that places him or her in an awkward situation. Moreover, information learned by either the provider or the patient via social networking can create ethical tensions (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Communication with patients through social networking.

Work-Life Balance

Maintaining a healthy work-life balance may be difficult when physicians continue communication with patients and families outside of the work environment. Over time, this could contribute to job burnout or compassion fatigue, a term used to describe a state of tension and preoccupation with the patient's suffering10 and depletion of the practitioner's emotional and physical energy toward work.11 Readily available contact information or current whereabouts may even facilitate cyber or physical stalking. Unwanted behavior may ensue, with increasing contact unrelated to medical care, such as showing up without an appointment just to hang out, or even more extreme situations, such as unwanted surveillance of the physician's whereabouts after work and threats of harm.12–15

Therapeutic Relationship

As the vignette illustrates, professional boundaries in oncology may remain unclear even after treatment is completed. The patient or family may desire to stay connected with the medical team, and the oncologist may not see any harm in developing a more familiar relationship with the family. The patient may send electronic invitations to their oncology practitioners to personal gatherings, including an end-of-treatment party, graduation, or wedding. But such blurring of boundaries can create difficulties in balancing the role and authority required in future professional interactions. If the oncologist attends such an event, and a more personal relationship develops, can he or she return to established boundaries if the patient relapses and needs further treatment? Will compliance with medical care be as good as it would with a physician who was not a friend?

Even if years have elapsed since the patient's treatment ended, the family can easily find staff members through an Internet search. In a New England Journal of Medicine publication,7 a physician described his response to receiving a Facebook friend request from a patient. Despite reporting uneasiness at the decision, he accepted the request and discovered that the patient simply wanted advice about medical school. In another report, a nurse practitioner opted to reject a Facebook friend request from a former patient 3 years after leaving the medical institution where they met and wrote the patient a note explaining that he felt it inappropriate, given the possibility of his future return to that institution. The patient understood his reasoning, and the professional relationship was preserved.16 These conversations can be delicate, because the patient may feel rejected or hurt by the oncology practitioner. Guidance on appropriate social media responses should be considered by the oncology practice, department, or institution, which should assist staff in rejecting a friend request without causing a patient to feel abandoned (Table 1; Fig 1).

Table 1.

Facebook/MySpace Etiquette

| Sample Situations | Sample Phrases |

|---|---|

| 1. You receive a friend request and don't want to confirm | “I'd be happy to communicate with you through other means (telephone, at the office) but I have a personal policy not to connect with patients or family members through this site.” |

| 2. You want to block a patient from seeing everything | “I'd like to be able to communicate with you through this site, but am unable to share all of my personal information with you, since it may affect our professional relationship.” Or “I carefully choose my privacy settings to preserve our professional relationship.” |

| 3. You want to defriend someone you have already connected with | “I'm sorry I can't continue to communicate with you through this venue. My institution has put a policy in place that prohibits me from connecting to patients or family members through this site.” |

Institutional Considerations

With the rapid growth of social media in academia and health care, overall guidance for the medical community is imperative. The American Medical Association recently enacted a social media policy that recommends using privacy settings, separating personal and professional presences online, and being cognizant that actions online can negatively affect one's career.17 The policy does not specifically address friend requests or how to maintain professionalism in the intense relationships that can develop in oncology settings. Medical and nursing journals, medical centers, and medical schools are trying to keep pace with the potential effects of such networking on clinical practice.18 The dean for medical education at Harvard Medical School recommended caution in using social networking sites such as Facebook. “Items that represent unprofessional behavior that are posted by you on such networking sites reflect poorly on you and the medical profession. Such items may become public and could subject you to unintended exposure and consequences.”19 Although social network effects on clinical practice have begun to receive public scrutiny, the potential risks associated with blurring professional boundaries through social networking are not consistently incorporated into medical school education.20

Discussion

Social media is a powerful and potentially useful tool in oncology and other clinical specialties, including enabling health professionals and consumers to network, participate in interest groups, and share information. Social networking may be especially helpful in reaching adolescent and young adult patients. However, the use of social media raises ethical challenges and can have harmful consequences if not used wisely (Appendix Table A1, online only). Communicating with patients on social media sites can cross professional-patient boundaries, risking patient confidentiality, exposing patients to inappropriate details of physicians' personal lives, and jeopardizing therapeutic relationships. Connecting with patients through online venues can also pose risks to providers' reputations, safety, privacy, and work-life balance. Physician organizations and institutions should consider progressive policies on professional and ethical responses to patient friend requests and the use of social media for work-related issues to keep both patients and physicians as productive and protected as possible.21

Some oncology centers are creating their own institutional Facebook page as one way to satisfy the desire to communicate via social media without jeopardizing individual provider-patient relationships. New avenues will emerge as social media technology evolves. With the rapid growth of technology and the transformational changes in how we communicate, there is a professional responsibility to establish norms and guidelines to protect and maximize our commitment to the best interests of our patients while maintaining high professional standards and integrity.

Acknowledgment

We appreciate the opportunity to discuss the complexities of communicating with patients through social media with oncology practitioners at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center. We thank Joan Sheeron, MA, RN, Seema Shah, JD, Crystal Mackall, MD, and Alan Wayne, MD, for their careful review and thoughtful comments. Supported in part by the Intramural Research Programs of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research, and Clinical Center. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not represent the opinions of the National Institutes of Health, Public Health Service, or Department of Health and Human Services.

Appendix

Table A1.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Social Media

| Media | Definition | Potential Advantages | Potential Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social networking sites that allow people to connect with friends and family or to expand their network with people of shared interests | • Information disseminated to a large number of people at no cost | • Sensitive content could unknowingly and rapidly be disseminated beyond the target audience18 | |

| MySpace | • Connections with people out of the geographic area | • Lack of filtering systems: some people post inappropriate images or messages17 | |

| Friendster | Sites include features such as sharing of photos, videos, music, personal news, and contact information, as well as communication through instant messaging or private e-mails | • Venue for online chats on health-related topics for people in similar situations or with similar interests17 | • Patient privacy issues if your “friends” can see information about patients you are friends with |

| • Avenue to follow patient's life after treatment | • Privacy issues if patients can see information about colleagues you are friends with • Clinicians could become privy to information not intended for them • Patients/families have access to personal content which could affect professional reputation • Friendships may transpire that go beyond medical professional/patient therapeutic relationship • Personal information posted on the site can alter focus to professional's personal life rather than patient's situation |

||

| Social network focused on professionals | • Can help clinicians identify other physicians and oncology practitioners by schooling and training • Can focus on a specific field or interest |

• Professional credentials are not verified • If you do not have many connections or are a new provider, or not viewed as active |

|

| Caring Bridge | Personal, private websites for people experiencing significant health challenges to connect with and update friends and family. Patients and families invite people to access their site, and site visitors can post messages of support | • Keep family, friends, community up-to-date on news of a patient's course of disease • Can help clinicians stay connected to patients, which may help to meet their own emotional needs • Can help clinicians feel they are being better providers by staying cognizant of family perspective |

• May contribute to compassion fatigue if clinician follows progress of patient outside of work • Potential to base decisions about care on personal feelings affected by what the clinician readsor on family's perspectives of treatment • Could interfere with treating all patients equally if clinician feels deeper connection to patient and family11 |

| Method of sending digital messages from one author to one or more recipients | • Immediate means of communication • Helps maintain contact with people who move around • Offers venue for medical advice without requiring an appointment/missing work |

• Sensitive content could rapidly be disseminated beyond the target audience (Guseh JS, et al: J Med Ethics 35:584-586, 2009) • If used as a replacement for in-person communication, can deprive the provider of critical information related to patient appearance and expression • Limits ability to ensure security of information—poses risks to privacy |

|

| Blogs | Web log: website that allows individuals to post regular entries of commentary, descriptions of events, or other material such as graphics or video, and visitors to post comments | • Quickly disseminate information to a large number of people at no cost • Maintain connections with people out of the area • Provide venue for online chats on health-related topics • Connect with young people where they are online and deliver health information (Bull SS, et al: J Pediatr Psychol 36:1082-1092, 2011) |

• Sensitive content could rapidly be disseminated beyond the target audience • Limits ability to ensure security of information—poses risks to privacy and could lead to HIPPA violations (Lagu T, et al: J Gen Intern Med 23:1642-1646, 2008) • Personal opinions could reflect poorly on the institution • Information can be taken out of context by visitors and forwarded to others, giving the author no opportunity to respond |

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: All authors

Administrative support: Lori Wiener

Provision of study materials or patients: Lori Wiener

Collection and assembly of data: Lori Wiener, Caroline Crum, Christine Grady

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

References

- 1.Moubarak G, Guiot A, Benhamou Y, et al. Facebook activity of residents and fellows and its impact on the doctor-patient relationship. J Med Ethics. 2011;37:101–104. doi: 10.1136/jme.2010.036293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black EW, Thompson LA, Duff P, et al. Revisiting social network utilization by physicians-in-training. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2:289–293. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00011.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheets V. Professional interpersonal boundaries: A commentary. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0FSZ/is_6_25/ai_n18609320/

- 4.Sable P. Pets, attachment, and well-being across the life cycle. Social Work. 1995;40:334–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith JB. Can you handle home care? RN. 1997;60:51–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.La Puma J, Priest R. Is there a doctor in the house? JAMA. 1992;267:1810–1812. doi: 10.1001/jama.267.13.1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain SH. Becoming a physician: Practicing medicine in the age of Facebook. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:649–651. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0901277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chretien K, Greysen S, Chretien JP, et al. Online posting of unprofessional content by medical students. JAMA. 2009;302:1309–1315. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawn C. Take two aspirin and tweet me in the morning: How twitter, facebook, and other social media are reshaping health care. Health Affairs. 2009;28:361–368. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.2.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maytum JC, Helman MB, Garwick AW. Compassion fatigue and burnout in nurses who work with children with chronic conditions and their families. J Pediatr Health Care. 2004;18:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Compassion fatigue: An expert interview with Charles R. Figley, MS, PhD. Medscape Psychiatry and Mental Health. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/513615.

- 12.Kearney MK, Weininger RB, Vachon ML, et al. Self-care of physicians caring for patients at the end of life. JAMA. 2009;301:1155–1164. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashmore R, Jones J, Jackson A, et al. A survey of mental health nurses' experiences of stalking. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2006;13:562–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2006.00981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hughes FA, Thom K, Dixon R. Nature and prevalence of stalking among New Zealand mental health clinicians. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2007;45:33–39. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20070401-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheridan LP, Blaauw E, Davies GM. Stalking knowns and unknowns. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2003;4:148–162. doi: 10.1177/1524838002250766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.La Puma J, Stocking CB, La Voie D, et al. When physicians treat members of their own families: Practices in a community hospital. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1290–1294. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110313251806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Medical Association. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2011. Code of Medical Ethics: Current Opinions With Annotations 2010-2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gruenberg PB. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2001. Boundary violations, in Ethics Primer of the American Psychiatric Association; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dr Jules Dienstag cautions doctors using Facebook and MySpace. Vitals. http://spotlight.vitals.com/2009/08/dr-jules-dienstag-cautions-doctors-using-facebook-and-myspace/

- 20.Social media in healthcare … Medicine for the masses: Part 2. Fresh ID. http://freshid.com/2010/07/social-media-in-healthcare%E2%80%A6medicine-for-the-masses-part-2/

- 21.Graham DL. Social media and oncology: Opportunity with risk. Am Soc Clin Oncol Ed Book. 2011:421–424. [Google Scholar]