Abstract

Objective

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to assess the effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction (mbsr) and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (mbct) in patients with breast cancer.

Methods

The medline, Cochrane Library, embase, cambase, and PsycInfo databases were screened through November 2011. The search strategy combined keywords for mbsr and mbct with keywords for breast cancer. Randomized controlled trials (rcts) comparing mbsr or mbct with control conditions in patients with breast cancer were included.

Two authors independently used the Cochrane risk of bias tool to assess risk of bias in the selected studies. Study characteristics and outcomes were extracted by two authors independently. Primary outcome measures were health-related quality of life and psychological health. If at least two studies assessing an outcome were available, standardized mean differences (smds) and 95% confidence intervals (cis) were calculated for that outcome. As a measure of heterogeneity, I2 was calculated.

Results

Three rcts with a total of 327 subjects were included. One rct compared mbsr with usual care, one rct compared mbsr with free-choice stress management, and a three-arm rct compared mbsr with usual care and with nutrition education. Compared with usual care, mbsr was superior in decreasing depression (smd: −0.37; 95% ci: −0.65 to −0.08; p = 0.01; I2 = 0%) and anxiety (smd: −0.51; 95% ci: −0.80 to −0.21; p = 0.0009; I2 = 0%), but not in increasing spirituality (smd: 0.27; 95% ci: −0.37 to 0.91; p = 0.41; I2 = 79%).

Conclusions

There is some evidence for the effectiveness of mbsr in improving psychological health in breast cancer patients, but more rcts are needed to underpin those results.

Keywords: Breast neoplasms, mindfulness-based stress reduction, mbsr, complementary therapies, psycho-oncology, meta-analysis, review

1. INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is the second most common cancer worldwide despite the fact that it is rare in men. In 2008, about 1.5 million new cases were diagnosed. Of all female cancers in 2008, 23% were breast cancers1. Although breast cancer mortality is still the highest among all cancers in women1, survival rates are increasing2. However, cancer diagnosis and treatment are often associated with physical and psychosocial impairments. Pain, fatigue, depression, and anxiety are the most common complaints in cancer patients3. Almost half of all cancer patients report fatigue as a problem, and more than one third experience substantial psychological distress4,5.

Complementary and alternative medicine is widely used by breast cancer patients to cope with symptoms of their disease6. More than 30% of all cancer patients utilize complementary medicine7.

Several complementary cancer treatments are based on mindfulness. Derived from the Buddhist Theravada tradition8, mindfulness has been viewed as the core construct of Buddhist meditation9. The mindfulness construct therefore describes engagement in a special form of meditation, but also a state of consciousness that has been characterized as a nonjudgmental moment-to-moment awareness and a curious experiential openness and acceptance towards one’s own experiences10. Mindfulness-based interventions therefore include not only training in the formal practice of mindfulness (mediation or mindful exercises, or both), but also training in the informal practice of mindfulness (retaining a mindful state of consciousness during routine activities in everyday life)9,11.

The most commonly used mindfulness-based interventions are mindfulness-based stress reduction (mbsr) and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (mbct)12,13. Mindfulness-based stress reduction is a structured 8-week group program of weekly 2.5-hour sessions and 1 all-day silent retreat. Key components of the program are sitting meditation, walking meditation, hatha yoga, and body scan (a sustained mindfulness practice in which attention is sequentially focused on various parts of the body)9. Another important component is the transition of mindfulness into everyday life. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy combines mbsr with cognitive–behavioral techniques14,15. Originally developed as a treatment for major depression14, mbct is more and more adapted for other specific conditions15. Other mindfulness-based interventions include mindful exercise16 and mindfulness-based art therapy17. A number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses suggest that mindfulness-based interventions are effective in chronic pain18, anxiety, and depression19. The effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions in cancer treatment has also been systematically reviewed20–22. Mindfulness-based stress reduction seems to be especially effective for a variety of psychosocial cancer symptoms such as stress, depression, anxiety, and reduced quality of life20–22; its effect on physical symptoms seems to be small20. The only systematic review of mbsr specifically for patients with breast cancer so far suggests a large effect of mbsr on psychological symptoms, mainly stress and anxiety, but a meta-analysis was not performed23.

The aim of the present review was to systematically assess and meta-analyze the effectiveness of mbsr and mbct in patients with breast cancer.

2. METHODS

The prisma (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines were followed to conduct this systematic review.

2.1. Literature Search

The medline, embase, Cochrane Library, Psycinfo, and cambase databases were searched from their inception until November 2011. No language restrictions were applied. The literature search consisted of key words for mbsr and mbct and keywords for breast cancer. The search strategy was adapted for each database as necessary. The complete search strategy for medline was: (MBSR[Title/Abstract] OR MBCT[Title/Abstract] OR mindful*[Title/Abstract]) AND (breast neoplasms[MeSH Terms] OR (breast[Title/Abstract] AND (neoplasm*[Title/Abstract] OR cancer[Title/Abstract] OR oncology[Title/Abstract]))). Reference lists of identified original and review papers were hand-searched to locate additional papers.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Randomized controlled trials (rcts) comparing mbsr or mbct with no treatment, usual care, or any active treatment were included. Nonrandomized trials were excluded. Only studies that assessed mbsr or mbct as the main intervention were eligible for inclusion. Studies of mindfulness-based interventions that were clearly different from the original mbsr or mbct programs, such as mindfulness-based exercise or art therapy were excluded, but variations of the mbsr or mbct programs, such as those of program length, frequency, or duration did not hinder inclusion. Studies that included patients with a diagnosis of breast cancer regardless of current treatment status were selected, but studies that included heterogeneous cancer populations were excluded.

2.3. Data Extraction

Two reviewers extracted data on the characteristics of the study (for example, trial design, randomization, blinding), characteristics of the patient population (sample size, stage of cancer, current treatment, age, and so on), characteristics of the intervention and control condition (type, program length, frequency, and duration, among others), outcome measures, results, and safety.

Risk of bias was assessed by two authors independently using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool24.

2.4. Data Analysis

Primary outcome measures were health-related quality of life and psychological health. Safety was defined as secondary outcome measure. Other outcome measures in the included studies underwent an exploratory analysis. If at least two studies with a specific outcome were available, a meta-analysis for that outcome was conducted using the Review Manager software application (version 5.1: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). Separate meta-analyses were conducted for measurements made at post-treatment and longest available follow-up. A random effects model was used.

Standardized mean differences (smds) with 95% confidence intervals (cis) were calculated. The smds were calculated as the difference in means between groups, divided by the pooled standard deviation. Where no standard deviations were available from the original records, they were calculated from standard errors, confidence intervals, or t-values, when available24.

This effect size is also known in the social sciences as the Hedges (adjusted) g. Cohen’s categories were used to evaluate the magnitude of the overall effect size with small, moderate, and large effect sizes being defined as smd = 0.2 to 0.5, smd = 0.5 to 0.8, and smd > 0.8 respectively25.

2.5. Assessment of Heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was explored using the I2 and chi-square statistics, measures of how much variance between studies can be attributed to differences between those studies rather than to chance. Moderate, substantial, and considerable heterogeneity were indicated by I2 > 30%, I2 > 50% and I2 > 75% respectively24. A p value of 0.10 or less from the chi-square test was considered to indicate significant heterogeneity24. To explore possible reasons for heterogeneity, sensitivity analyses were planned by type of intervention (mbsr or mbct), type of control treatment (usual care or active comparator), and current cancer treatment (use of chemotherapy or radiation, or no conventional treatment).

2.6. Publication Bias

Publication bias was assessed by visual analysis of funnel plots generated using the Review Manager software application. Asymmetry of funnel plots was regarded to indicate publication bias26.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study Selection

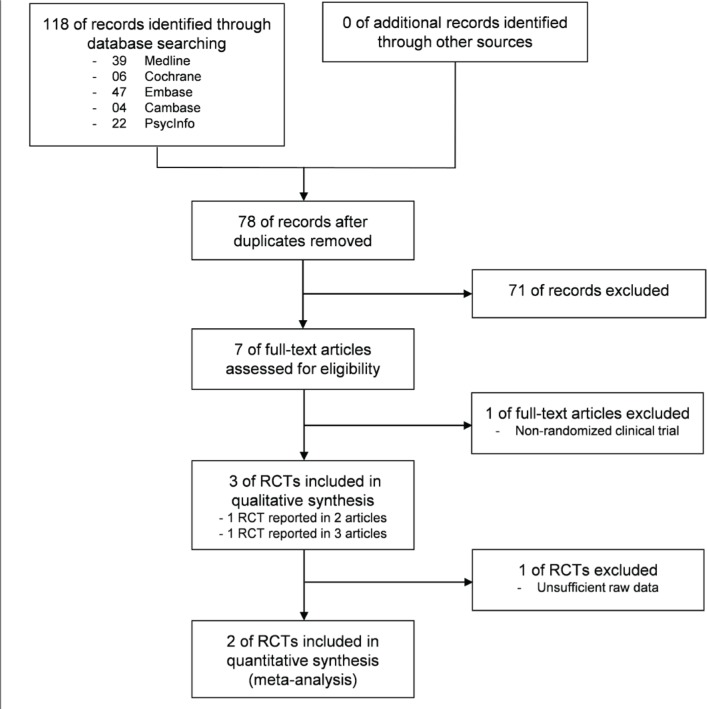

The literature search located 118 records, 40 of which were duplicates (Figure 1). Seven full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. One article had to be excluded because the study it reported was not randomized27. The remaining six articles reported results from three rcts. Two articles28,29 reported separate outcomes for one rct, and 3 articles30–32 reported separate outcomes for another rct. The third article33 described part of a larger rct; however, no other records for that study could be located.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of the results of the literature search.

3.2. Study Characteristics

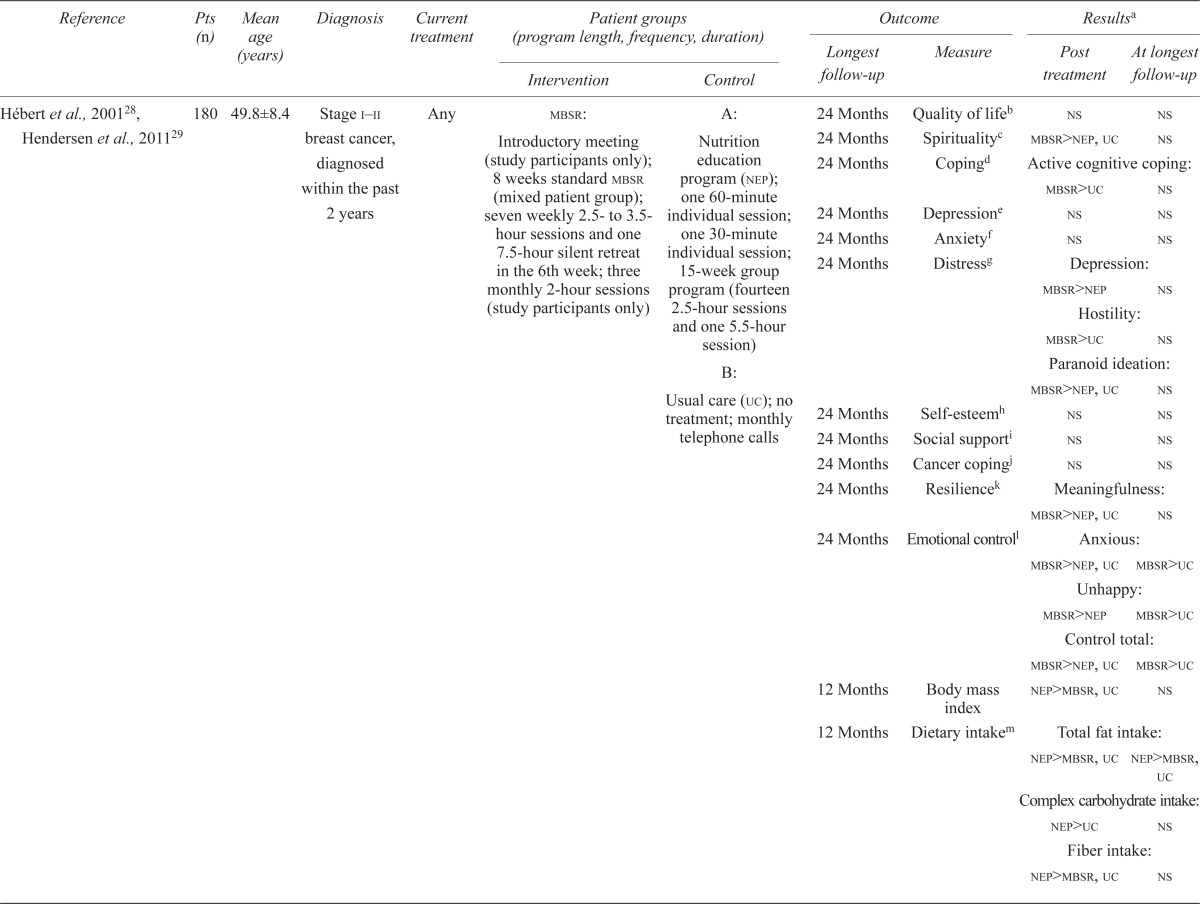

Table i shows key characteristics of the included studies.

TABLE I.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Reference | Pts (n) | Mean age (years) | Diagnosis | Current treatment |

Patient groups (program length, frequency, duration)

|

Outcome

|

Resultsa

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | Longest follow-up | Measure | Post treatment | At longest follow-up | |||||

| Hébert et al.,200128, Hendersen et al.,201129 | 180 | 49.8±8.4 | Stage i–ii breast cancer, diagnosed within the past 2 years | Any |

mbsr: Introductory meeting (study participants only); 8 weeks standard mbsr (mixed patient group); seven weekly 2.5- to 3.5- hour sessions and one 7.5-hour silent retreat in the 6th week; three monthly 2-hour sessions (study participants only) |

A: Nutrition education program (nep); one 60-minute individual session; one 30-minute individual session; 15-week group program (fourteen 2.5-hour sessions and one 5.5-hour session) |

24 Months | Quality of lifeb | ns | ns |

| 24 Months | Spiritualityc | mbsr>nep, uc | ns | |||||||

| 24 Months | Copingd | Active cognitive coping: | ||||||||

| mbsr > uc | ns | |||||||||

| 24 Months | Depressione | ns | ns | |||||||

| 24 Months | Anxietyf | ns | ns | |||||||

| 24 Months | Distressg | Depression: | ||||||||

| mbsr > nep | ns | |||||||||

| Hostility: | ||||||||||

| mbsr > uc | ns | |||||||||

| B: Usual care (uc); no treatment; monthly telephone calls | Paranoid ideation: | |||||||||

| mbsr > nep, uc | ns | |||||||||

| 24 Months | Self-esteemh | ns | ns | |||||||

| 24 Months | Social supporti | ns | ns | |||||||

| 24 Months | Cancer copingj | ns | ns | |||||||

| 24 Months | Resiliencek | Meaningfulness: | ||||||||

| mbsr > nep, uc | ns | |||||||||

| 24 Months | Emotional controll | Anxious: | ||||||||

| mbsr > nep, uc | mbsr > uc | |||||||||

| Unhappy: | ||||||||||

| mbsr > nep | mbsr > uc | |||||||||

| Control total: | ||||||||||

| mbsr > nep, uc | mbsr > uc | |||||||||

| 12 Months | Body mass index | nep > mbsr, uc | ns | |||||||

| 12 Months | Dietary intakem | Total fat intake: | ||||||||

| nep > mbsr, uc | nep > mbsr, uc | |||||||||

| Complex carbohydrate intake: | ||||||||||

| nep > uc | ns | |||||||||

| Fiber intake: | ||||||||||

| nep > mbsr, uc | ns | |||||||||

| Lengacher et al.,200930, Lengacher et al., 201131 , Lengacher et al.,201132 | 84 | 57.5±9.4 | Stage 0–iii breast cancer, underwent surgery and received radiation or chemotherapy, or both | Within 18 months post treatment | mbsr (n=41): Standard mbsr adapted for breast cancer patients in six 2-hour weekly sessions; formal practice 6 days each week, 15–45 minutes daily; informal practice 15–45 minutes daily | Usual care [uc (n=43)]: Standard post-treatment clinic visits | No follow-up | Fear of recurrencen | mbsr> uc | — |

| Anxietyo | mbsr>uc | — | ||||||||

| Depressionp | mbsr>uc | — | ||||||||

| Optimismq | ns | — | ||||||||

| Perceived stressr | ns | — | ||||||||

| Quality of lifes | Physical function: | |||||||||

| mbsr>uc | — | |||||||||

| Role physical: | ||||||||||

| mbsr>uc | — | |||||||||

| Energy: | ||||||||||

| mbsr>uc | — | |||||||||

| Social supportt | ns | — | ||||||||

| Spiritualityu | ns | — | ||||||||

| Residual symptomsv | ns | — | ||||||||

| Immune recoveryw | Percentage activated T cells: | |||||||||

| mbsr>uc | — | |||||||||

| T-Helper 1/T-helper 2 ratio: | ||||||||||

| mbsr>uc | — | |||||||||

| Shapiro et al., 200333 | 63 | 57.0±9.7 | History of stage ii breast cancer, currently in remission | Within 24 months post treatment |

mbsr (n=31): Adapted from standard mbsr, six 2-hour weekly sessions and one 6-hour silent retreat |

Free choice (n=32): Weekly free choice of stress management technique for 6 weeks |

9 Months | Moodx | nr | nr |

| Depressione | nr | nr | ||||||||

| Worryy | nr | nr | ||||||||

| Anxietyo | nr | nr | ||||||||

| Quality of lifeb | nr | nr | ||||||||

| Controlz | nr | nr | ||||||||

| Resiliencek | nr | nr | ||||||||

| Sleep quality and efficiency (sleep diary) | ns | nr | ||||||||

A greater than symbol (>) means “significantly better than.”

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Breast.

Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Spiritual Well-Being.

Dealing with Illness questionnaire.

Beck Depression Inventory.

Beck Anxiety Inventory.

Symptom Checklist 90–Revised.

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale.

UCLA Loneliness Scale.

Mini Mental Adjustment to Cancer Scale.

Sense of Coherence Scale.

Courtauld Emotional Control Scale.

7-Day dietary recall.

Concerns About Recurrence Scale.

State–Trait Anxiety Inventory.

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

Life Orientation Test.

Perceived Stress Scale.

Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form Health Survey.

Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey.

Likert scale.

MD Anderson Symptom Inventory.

Lymphocyte subsets, T cell activation, T-helper 1 and 2 cytokines.

Profile of Mood States.

Penn State Worry Questionnaire.

Shapiro Control Inventory.

Pts = patients; mbsr = mindfulness-based stress reduction;

ns = no significant group difference; nr = not reported.

All three included rcts were conducted in the United States. Patients were recruited from cancer centres30–32, hospitals28,29, or private oncology practices33. Cancer populations were quite homogeneous between the studies, with no study including patients with metastatic breast cancer. Patients in two studies had recently completed breast cancer treatment30–33; patients in the third study were included regardless of current cancer treatment provided they had been diagnosed within the preceding 2 years28,29. In the latter study, 11.7% of patients received chemotherapy and 24.5% received radiation during the study28,29. All three studies defined a broad range of ages as eligible for inclusion, but the mean age of the included patients was comparable between studies, ranging from 50 years to 57.5 years.

3.2.1. MBSR

All included rcts assessed mbsr interventions that were adapted from the original mbsr program.

Patients in one trial29 participated in a standard mbsr intervention, including eight 2.5- to 3.5-hour weekly sessions and an all-day silent retreat. Besides the study patients, a heterogeneous group with various somatic or psychiatric disorders participated in that program. For study participants, the standard mbsr program was complemented by preceding and ensuing sessions.

The other two rcts30–33 used study-participant-only programs that differed from the original mbsr program mainly in terms of program length. Both interventions were only 6 weeks in length, with weekly 2-hour sessions. One trial included an all-day silent retreat33; the other did not30–32. The mbsr interventions included formal (sitting meditation, walking meditation, body scan, gentle yoga) and informal practice of mindfulness. In two trials, the program components were adapted to the needs and possibilities of breast cancer patients30–33. In one trial, the intervention was presented by specially trained mental health clinicians who were long-term meditation practitioners29; in another trial, it was presented by a clinical psychologist trained and licensed in mbsr30–32. The third trial did not report the professional qualification of the mbsr instructors33.

3.2.2. Control Conditions

One rct compared mbsr with usual care. The usual-care group did not receive a specific intervention, but did continue standard individual post-treatment clinic visits. Patients were instructed not to use mbsr, yoga, or meditation during the study period30–32. Another rct compared mbsr with usual care and a nutrition education program. The nutrition program involved education on dietary change and group cooking, based on social cognitive theory and patient-centered counselling28,29. The third rct compared mbsr with free choice stress management. Each week, patients were free to choose a stress-management technique in which to engage—such as talking to a friend, exercise, or taking a bath33.

In only one rct were contact time and homework practice matched for mbsr and at least one control condition29.

3.3. Risk of Bias

Table ii shows risk of bias for each study. No study reported methods of random sequence generation or allocation concealment. Only one study addressed blinding, and it reported blinding of patients and outcome assessors at baseline but not at post-treatment assessment30. Selective reporting was present in all the included studies: two rcts reported results for various outcome measures in multiple publications28–32; the third did not report results for all pre-specified outcomes33. The overall evidence was therefore of unclear selection bias, performance bias, and detection bias, with a high risk of reporting bias, but a low risk of attrition bias and other bias24 (Table ii).

TABLE II.

Risk of bias assessmenta of the included studies

| Reference |

Type of bias

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random sequence generation (“selection”) | Allocation concealment (“selection”) | Blinding of participants and personnel (“performance”) | Blinding of outcome assessment (“detection”) | Incomplete outcome data (“attrition”) | Selective reporting (“reporting”) | Other | |

| Hendersen et al., 201128, Hébert et al., 200129 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | High risk | Low risk |

| Lengacher et al., 200930, Lengacher et al., 201131, Lengacher et al., 201132 | Unclear | Unclear | High risk | High risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk |

| Shapiro et al., 200333 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | High risk | Low risk |

Using the Cochrane risk of bias tool.

3.4. Outcomes

3.4.1. MBSR Versus Usual Care

Two rcts compared mbsr with usual care28–32, one of which included repeated measurements at various points in time.

Post-Treatment:

Both trials assessed health-related quality of life post treatment; however, only one trial reported significant group differences favoring mbsr30. Insufficient reporting of raw data29 hindered meta-analysis. Both trials also assessed a wide range of psychosocial variables post treatment. One trial29 reported mbsr as being superior to usual care in improving coping strategies, distress, resilience, and emotional control (Table i). The other trial30 reported significant group differences favouring mbsr with respect to fear of cancer recurrence (Table i).

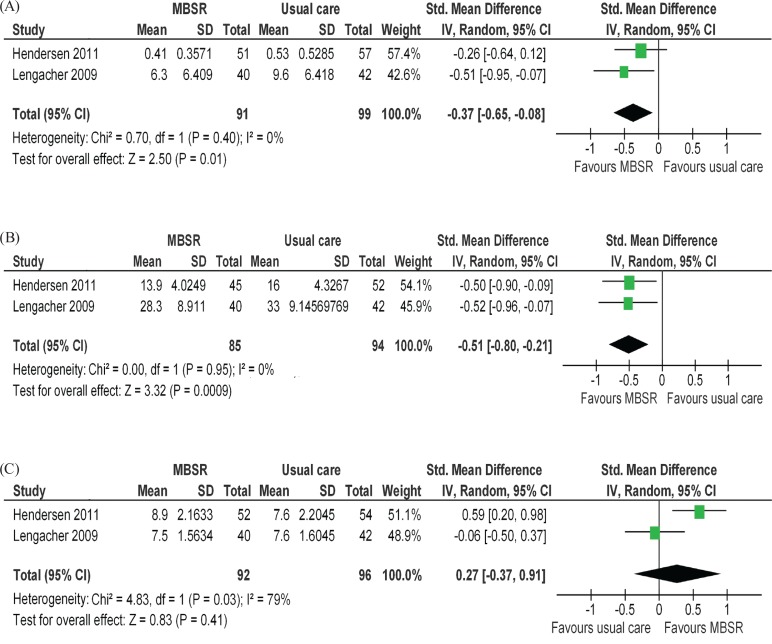

Both rcts assessed depressive symptoms. One trial reported mbsr as being superior to usual care in relieving depression30; the other trial reported significant group differences for only one of two outcome measures for depression29. Meta-analysis revealed a small but significant overall effect (smd: −0.37; 95% ci: −0.65 to −0.08; p = 0.01). The rcts were homogeneous, with an I2 of 0% (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Forest plots of mindfulness-based stress reduction versus usual care for (A) depression, (B) anxiety, and (C) spirituality.

Both rcts also assessed anxiety. Again, one trial found mbsr superior to usual care30, and the other trial found mbsr to be superior in only one of two outcome measures for anxiety29. The pooled effect was significant and of moderate size (smd: −0.51; 95% ci: −0.80 to −0.21; p = 0.0009). Again, the rcts were homogeneous, with an I2 of 0% (Figure 2).

Both rcts measured spirituality, and one reported significant group differences favouring mbsr29. Meta-analysis did not find significant group differences (smd: 0.27; 95% ci: −0.37 to 0.91; p = 0.41; I2 = 79%).

One rct assessed body mass index and dietary intake post treatment, but did not find significant differences between mbsr and usual care28. The other rct measured immune parameters32. For most parameters, the groups were not significantly different, but the percentage of activated T cells and the T-helper 1–to–T-helper 2 ratio were significantly higher in the mbsr group.

Longest Follow-Up:

One rct assessed quality of life and psychosocial variables at various points in time, with 24 months after the start of the intervention being the longest follow-up29. At that time point, mbsr was superior to usual care in improving anxiety and emotional control. The same rct also assessed body mass index and dietary intake 12 months after the start of the intervention, but did not find significant group differences28.

3.4.2. MBSR Versus Nutrition Education Program

One rct compared mbsr with a nutrition education program28,29. At the post-treatment assessment, mbsr was superior to nutrition education in increasing spirituality, resilience, and emotional control, and in decreasing distress29. In contrast, nutrition education was superior to mbsr in decreasing body mass index and dietary intake of total fat and fiber post treatment28. At longest follow-up, the only significant group difference was total fat intake favouring nutrition education28.

3.4.3. MBSR Versus Free Choice Stress Management

One rct compared mbsr with a free choice of stress management technique33. This trial assessed a variety of psychosocial variables post treatment, but results for the selected outcome measures have not been reported. Results for sleep quality and sleep efficiency were reported, but the trial did not find any significant group differences.

3.5. Sensitivity Analysis

Because only two studies were included in each meta-analysis, sensitivity analyses were impossible.

3.6. Publication Bias

Because of the small number of eligible studies, visual analysis of funnel plots led to inconclusive results.

3.7. Safety

No study formally reported the occurrence (or absence) of adverse events. Only one trial described reasons for all drop-outs30. In that trial, only 1 patient dropped out from the mbsr group, and her drop-out was related to recurrence of her cancer30. Another trial reported 1 drop-out in the mbsr group because of cancer recurrence before the intervention began33, but reasons for drop-outs during the intervention period were not given. The third trial reported the number of drop-outs, but no reasons for the drop-outs28,29.

4. DISCUSSION

Previous systematic reviews found favourable effects of mbsr on psychosocial variables in cancer patients20–22. However, only one systematic review so far has focused solely on breast cancer patients23. An important finding of previous reviews is that, although a considerable amount of literature has been published on mbsr in supportive cancer treatment, very few rigorous trials have been conducted. That finding is confirmed by the results of the present systematic review. Literature search identified only three rcts, none of them ensuring or reporting rigorous methodology.

Yet, despite the low number of eligible studies, meta-analysis found small effects for mbsr compared with usual care in decreasing depression and anxiety. Moreover, there is limited evidence from one rct each that mbsr can improve coping strategies, distress, resilience, emotional control, and fear of cancer recurrence. That finding accords with earlier meta-analyses on mbsr for heterogeneous cancer populations that reported small effect sizes for mental health20 and mood, and moderate effect sizes for distress21. However, a recent systematic review23 reported large effect sizes for mbsr in improving anxiety and perceived stress in breast cancer patients, but only for uncontrolled trials34–36.

Although the meta-analysis reported here did not find a significant effect of mbsr compared with usual care for improving spirituality, one trial found increased spiritual well-being after mbsr was compared with usual care and nutrition education29. That finding accords with results from another study that found increased spiritual well-being in cancer patients after mbsr37.

On the other hand, evidence for physical improvements was very low, which is again consistent with earlier meta-analyses in mixed cancer populations, which either did not address physical outcomes21 or found mostly small effects20,23.

No study reported adverse events, and reasons for drop-outs were poorly reported. Those findings are unsatisfying, because safety is a major focus in the evaluation of therapies. Further trials should focus on complete reporting of safety data.

The included studies were conducted in primary, secondary, and tertiary care settings. The results of the present review are therefore applicable to patients in all settings of care, but are, however, limited to patients with non-metastatic breast cancer.

All included rcts used mbsr as an intervention. No rct assessing the effectiveness of mbct in breast cancer patients could be located. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy was originally developed for patients with recurrent depression14, but is now also used in oncology settings38. A rct with mixed cancer patients reported significant improvements in depression, anxiety, and distress after mbct38. Further rcts are needed before the evidence of mbct in breast cancer patients can be judged.

For investigating the effectiveness of mbsr, rcts are the most suitable design. On the other hand, the existential changes that may result from participation in a mbsr program might be better addressed using qualitative approaches39. Additional qualitative studies on mbsr that complement rcts in breast cancer patients are needed22.

The evidence reviewed here is clearly limited for several reasons. First, the total number of eligible rcts was small. Only two trials could therefore be included in each meta-analysis. Although meta-analyses can be done by combining at least two studies24, the conclusions drawn from such meta-analyses remain preliminary. Second, reporting of the studies themselves was incomplete. Risk of selection bias, performance bias, and detection bias could therefore not be ruled out. The evidence as published raised suspicion of high reporting bias. Risk of publication bias could not be ruled out because of the small number of included studies. Third, meta-analyses could be performed only to compare mbsr with usual care. Although the evidence that mbsr is superior to usual care is promising, more research is needed to evaluate the superiority or inferiority of mbsr in comparison with other active treatments.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This systematic review found some evidence for the effectiveness of mbsr in improving psychological health in breast cancer patients, although the evidence was limited by incomplete reporting and shortcomings in the methodology of the included trials. The existing data are promising, but further and more rigorous research is needed before the evidence for mbsr in supportive breast cancer treatment can be conclusively judged.

6. CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

All authors declare that they have no financial conflicts of interest.

7. REFERENCES

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. GLOBOCAN 2008 v1.2. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 10 [Web resource] Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010.[Available online at: http://globocan.iarc.fr (choose “World” and click “Go” in the left-side menu bar); cited November 7, 2011]

- 2.Berry DA, Cronin KA, Plevritis SK, et al. on behalf of the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (cisnet) collaborators Effect of screening and adjuvant therapy on mortality from breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1784–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patrick DL, Ferketich SL, Frame PS, et al. on behalf of the National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Panel National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference Statement. Symptom management in cancer: pain, depression, and fatigue, July 15–17, 2002. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1110–17. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Piantadosi S. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology. 2001;10:19–28. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200101/02)10:1<19::AID-PON501>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlson LE, Angen M, Cullum J, et al. High levels of untreated distress and fatigue in cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:2297–304. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fouladbakhsh JM, Stommel M. Gender, symptom experience, and use of complementary and alternative medicine practices among cancer survivors in the U.S. cancer population. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37:E7–15. doi: 10.1188/10.ONF.E7-E15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ernst E, Cassileth BR. The prevalence of complementary/alternative medicine in cancer: a systematic review. Cancer. 1998;83:777–82. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19980815)83:4<777::AID-CNCR22>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gunaratana B. Mindfulness in Plain English. Somerville, MA: Wisdom Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kabat–Zinn J. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness. New York, NY: Bantam Dell; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bishop SR, Lau M, Shapiro S, et al. Mindfulness: a proposed operational definition. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2004;11:230–41. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bph077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shapiro SL, Carlson LE, Astin JA, Freedman B. Mechanisms of mindfulness. J Clin Psychol. 2006;62:373–86. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baer RA. Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: a conceptual and empirical review. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2003;10:125–43. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpg015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baer R, Krietemeyer J. Overview of mindfulness and acceptance based treatment approaches. In: Baer RA, editor. Mindfulness Based Treatment Approaches; Clinician’s Guide to Evidence Base and Applications. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Academic Press; 2006. pp. 3–27. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teasdale JD, Segal ZV, Williams JM, Ridgeway VA, Soulsby JM, Lau MA. Prevention of relapse/recurrence in major depression by mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:615–23. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.4.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crane R. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy: Distinctive Features. New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor and Francis Group; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tacón AM, McComb J. Mindful exercise, quality of life, and survival: a mindfulness-based exercise program for women with breast cancer. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15:41–6. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monti DA, Peterson C, Kunkel EJ, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of mindfulness-based art therapy (mbat) for women with cancer. Psychooncology. 2006;15:363–73. doi: 10.1002/pon.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Veehof MM, Oskam MJ, Schreurs KM, Bohlmeijer ET. Acceptance-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2011;152:533–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, Oh D. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78:169–83. doi: 10.1037/a0018555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ledesma D, Kumano H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and cancer: a meta-analysis. Psychooncology. 2009;18:571–9. doi: 10.1002/pon.1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Musial F, Büssing A, Heusser P, Choi KE, Ostermann T. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for integrative cancer care: a summary of evidence. Forsch Komplementmed. 2011;18:192–202. doi: 10.1159/000330714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shennan C, Payne S, Fenlon D. What is the evidence for the use of mindfulness-based interventions in cancer care? A review. Psychooncology. 2011;20:681–97. doi: 10.1002/pon.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matchim Y, Armer JM, Stewart BR. Mindfulness-based stress reduction among breast cancer survivors: a literature review and discussion. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011;38:E61–71. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.E61-E71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Ver. 5.1.0. Oxford, U.K.: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Available online at: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org; cited November 7, 2011]

- 25.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matchim Y, Armer JM, Stewart BR. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (mbsr) on health among breast cancer survivors. West J Nurs Res. 2011;33:996–1016. doi: 10.1177/0193945910385363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hebert JR, Ebbeling CB, Olendzki BC, et al. Change in women’s diet and body mass following intensive intervention for early stage breast cancer. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101:421–31. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henderson VP, Clemow L, Massion AO, Hurley TG, Druker S, Hébert JR. The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on psychosocial outcomes and quality of life in early-stage breast cancer patients: a randomized trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;131:99–109. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1738-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lengacher CA, Johnson-Mallard V, Post–White J, et al. Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction (mbsr) for survivors of breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18:1261–72. doi: 10.1002/pon.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lengacher CA, Reich RR, Post–White J, et al. Mindfulness based stress reduction in post-treatment breast cancer patients: an examination of symptoms and symptom clusters. J Behav Med. 2012;35:86–94. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9346-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lengacher CA, Kip KE, Post–White J, et al. Lymphocyte recovery after breast cancer treatment and mindfulness-based stress reduction (mbsr) therapy. Biol Res Nurs. 2011. :[Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Shapiro SL, Bootzin RR, Figueredo AJ, Lopez AM, Schwartz GE. The efficacy of mindfulness-based stress reduction in the treatment of sleep disturbance in women with breast cancer: an exploratory study. J Psychosom Res. 2003;54:85–91. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00546-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dobkin PL. Mindfulness-based stress reduction: what processes are at work? Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2008;14:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tacon AM, Caldera YM, Ronaghan C. Mindfulness-based stress reduction in women with breast cancer. Fam Syst Health. 2004;22:193–203. doi: 10.1037/1091-7527.22.2.193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tacon AM, Tacon AM, Ronaghan C. Mindfulness, psycho-social factors, and breast cancer. J Cancer Pain Symptom Palliat. 2005;1:45–53. doi: 10.1300/J427v01n01_06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garland SN, Carlson LE, Cook S, Lansdell L, Speca M. A nonrandomized comparison of mindfulness-based stress reduction and healing arts programs for facilitating post-traumatic growth and spirituality in cancer outpatients. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:949–61. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0280-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Foley E, Baillie A, Huxter M, Price M, Sinclair E. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for individuals whose lives have been affected by cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78:72–9. doi: 10.1037/a0017566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verhoef MJ, Casebeer AL, Hilsden RJ. Assessing efficacy of complementary medicine: adding qualitative research methods to the “gold standard.”. J Altern Complement Med. 2002;8:275–81. doi: 10.1089/10755530260127961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]