Abstract

PURPOSE

This investigation examined the trends for gender-based advancement in academic surgery by performing a comparative analysis of the rate of change in the percentage of medical students, surgery residents, and full professors of surgery who are women.

METHODS

All available Women in Medicine Annual Reports were obtained from the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC). The gender compositions of medical graduates, surgery residents, and full professors were plotted. Binomial and linear trendlines were calculated to estimate the year when 50% of surgery full professors would be women. Additionally, the percentage distribution of men and women at each professorial rank was determined from 1995 to 2009 using these reports to demonstrate the rate of academic advancement of each gender.

RESULTS

The slope of the line of increase for women full professors is significantly less than for female medical students and for female general surgery residents (0.36, compared with 0.75 and 0.99, respectively). This predicts that the earliest time that females will account for 50% of full professors in surgery is the year 2096. When comparing women and men in academic ranks, we find that women are much less likely than men to be full professors.

CONCLUSIONS

The percentage of full professors in surgery who are women is increasing at a rate disproportionately slower than the increases in female medical students and surgery residents. The rates of increase in female medical students and surgery residents are similar. The disproportionately slow rate of increase in the number of female full professors suggests that multiple factors may be responsible for this discrepancy.

Keywords: faculty, medical/statistics & numerical data, physicians, women/trends, physicians, women/statistics & numerical data, career mobility, gender bias, surgery, surgery department, hospital

INTRODUCTION

Ecosystem stability depends on the ability of the community to contain functional groups with different responses to stressors.1 Physicians in the United States consisted of men only until Elizabeth Blackwell graduated from Geneva Medical College in 1849; 160 years later, women are trying to establish themselves as part of the leadership of the medical profession.2,3

In 1996, the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) approved the first report from the Increasing women’s Leadership in Academic Medicine Project Committee, identifying 15 tasks organized under 3 objectives designed to increase the number of women progressing to the senior ranks in academic medicine.4 A key finding was that the numbers of women faculty, department chairs, and deans have all increased; however, the disparities in gender advancement have not been reduced substantially.4 Cohort studies of medical school faculty have found that women remain less likely than men to be promoted, even after adjusting for the number of publications, amount of grant support, tenure vs other career track, hours worked, and specialty.5-8

In this study, we investigated these trends as they pertain to surgery on a national level for the past 15 years. Subsequently, we compared our findings to the data at our institution, Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC). We then created a brief questionnaire and surveyed the general surgical residents and faculty of the Section of Surgical Sciences to gain insight into the reasons for the trends observed.

METHODS

Data collection

The data for this study were taken from reports from the AAMC. All Women in Academic Medicine: Statistics and Benchmarking Reports were obtained from the AAMC. These reports are generated annually from 1983 until the present; the earliest reports contained data from as early as 1965. We requested all available reports from the AAMC. We received reports for 1983 and 1992-2009. Specifically, medical student data were available from the years 1965, 1970, 1975, 1980, 1985, and 1990-2008. Surgery resident data were available from 1981, 1988-1991, and 1993-2008. Surgery professor data were available from 1995 and 1997-2009. We used all data points provided by the AAMC.

These reports contain information regarding the gender of medical school graduates, resident matriculants, and academic faculty at schools accredited by the AAMC.9 Data from each reporting institution are verified by Faculty Roster Representatives or Women Liaison officers. In 2009, of the 130 accredited medical schools, 120 provided data for this report, for a response rate of 92%.9 The main limitation of the survey is that part of the data is obtained from the prepopulated faculty roster data, which may not be verified by the submitting institution.9

VUMC data were obtained from the faculty roster for the Section of Surgical Sciences. The surgical specialties included were general surgery, vascular surgery, transplant surgery, orthopedic surgery, otorhinolaryngology, neurosurgery, pediatric surgery, plastic surgery, thoracic surgery, cardiac surgery, urology, and oral and maxillofacial surgery.

VUMC faculty belonging to these specialties and all general surgical residents were also asked to respond to a survey created using Research Electronic Data Capture Software (REDCap; Vanderbilt University) (Fig. 1).10 The study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Vanderbilt University.10 REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing (1) an intuitive interface for validated data entry, (2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures, (3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages, and (4) procedures for importing data from external sources. Additional demographics of age, gender, and academic rank were also collected.

FIGURE 1.

Gender in academic medicine survey.

Data Analysis

These data were used to determine the percentage of medical school graduates, general surgery residency matriculants, and full professors in surgery who were women for all years contained within the reports. Subsequently, these percentages were plotted simultaneously to investigate trends. A linear and binomial approximation was calculated using GraphPad Prism (La Jolla, California) to examine slope and to approximate the year that women’s share of full professors in surgery would equal 50%.

Data from the AAMC over the past 14 years were also used to analyze the progression of women and men through the academic ranks in surgery. These data were tabulated over the course of 1995-2009 and displayed as a percentage of total faculty members. The years not shown in these data resemble the trends of the other years. Additionally, the raw numbers of professors in surgery of each gender were plotted over the course of 1995-2009 to investigate the total increase of persons of each gender at the professorial level.

VUMC surgical faculty statistics were examined in a similar manner to determine the progression through the academic ranks by men and women in surgical specialties at VUMC. The number of faculty members is expressed as a percentage of the entire VUMC surgical faculty.

To compare male and female responses to the survey, a generalized lambda test was conducted to determine whether women and men differed in their responses to the 11 statements in the questionnaire (using IBM SPSS 18; SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois).

RESULTS

Matriculation

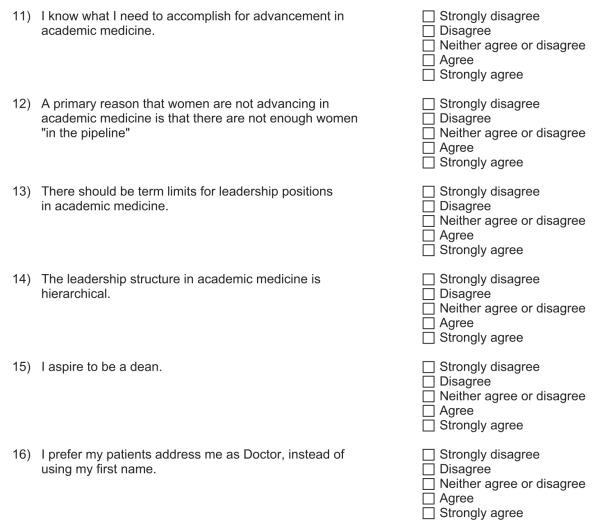

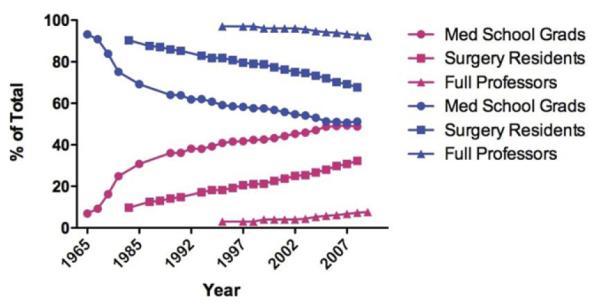

Since 2005, the percentage of medical school graduates who are women has equilibrated at approximately 50%. Figure 2 demonstrates how the gender compositions of graduating medical student classes, surgery residents, and full professorship have changed over time. The graph shows that all lines seem to trend toward convergence but at different rates. In 2008, 48.8% of medical school graduates were women, 32.3% of general surgery residents were women, and the percentage of full professors in surgery who were women was low at 7.3%. A linear trend suggests that surgery residents could have equal proportions of women and men by the year 2028 (R2 = 0.98). From the binomial trend line equation for full professors of surgery, we estimate that there will be an equal number of male and female full professors in surgery in the year 2096 (R2 = 0.98).

FIGURE 2.

Gender composition trends for medical graduates, surgical residents, and surgical professors. The graph represents how the gender compositions of graduating medical student classes, surgery residents, and full professorship have changed from 1965 to 2009. Pink delineates women and blue delineates men. Using data lines with the best fit, this graph suggests that the gender composition of surgery residents and full professors of surgery could be 50% women by the year 2028 and 2096, respectively.

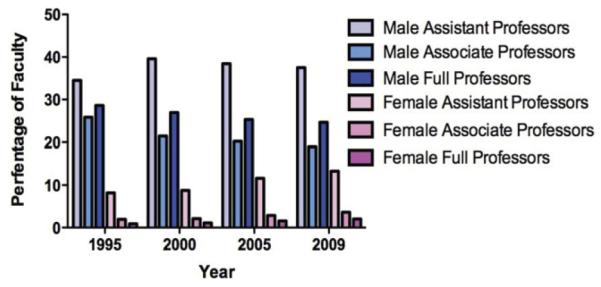

AAMC

Fourteen years of AAMC data (1994-2009) demonstrated a difference in the magnitude of and general trends in the percentages of men and women at each academic rank (Fig. 3). There are more assistant professors than either associate or full professors for both men and women. Over the years, among men, there have been more full professors than associate professors. Conversely, this pattern is not observed for female professors of surgery; in particular, associate professors outnumber full professors among women. And, while the pattern is changing slowly, men still dominate all ranks of surgical professorships.

FIGURE 3.

Advancement in academic surgery. The data compiled for the years 1995, 2000, 2005, and 2009 from the AAMC show the gender and rank composition of surgical faculty. There are more assistant professors than either associate or full professors among both men and women. Among men, full professors outnumber associate professors. Conversely, among women, both assistant and associate professors outnumber full professors.

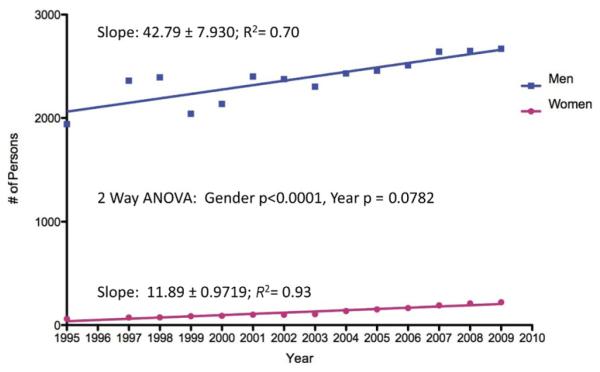

Examining the same 14 years of AAMC data, the numbers of both women and men who are full professors in surgery have increased (Fig. 4). Linear regression was performed separately for women and men. Men have a slope of 42.79 (R2 = 0.70) and women have a slope of 11.89 (R2 = 0.93). Thus, approximately 43 additional men become full professors of surgery each year, compared with approximately 12 women. A 2-way analysis of variance performed on these data demonstrated that gender was significant reason for the difference in number of full professors (p < 0.0001), whereas the year was not (p = 0.0782).

FIGURE 4.

Annual number of professors of surgery in the United States. Graphical comparison of the number of male and female full professors of surgery in the United States.

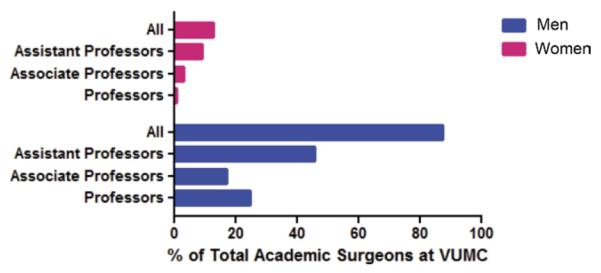

VUMC

When VUMC’s gender profile was compared with the AAMC data, the same gender advancement patterns were observed (Fig. 5). These data show the same pattern of gender differences as the AAMC data (Fig. 3). In particular, the ratio of male to female faculty members is high, and full professors outnumber associate professors among men but not among women.

FIGURE 5.

Advancement in academic surgery at VUMC. These data show gender differences similar to those shown in Fig. 3. In particular, full professors outnumber associate professors among men but not among women.

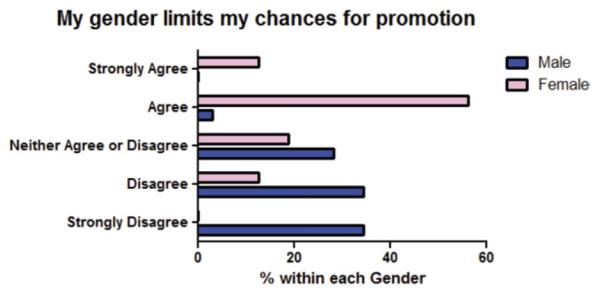

VUMC Questionnaire

The survey was answered by 32 men and 16 women faculty members and residents for a response rate of 32%. The mean age was 36.90 ± 9.40 years old with a range of 0-27 years served in academic medicine, with an average duration of 4.33 ± 6.80 years. Zero years indicated that the participant was a resident. Of the 11 statements in the survey, only 1 resulted in a statistically significant difference across genders (Fig. 6). The absence of statistically significant differences on other some other statements is partly because of the small sample size (n = 48). The statement asked whether respondents believed gender limited their chances for promotion. The lambda test for gender dependence in the nominal data showed that λ = 0.625 and p = 0.01. Female participants were significantly more likely than male participants to respond that their gender limited their chances for promotion.

FIGURE 6.

Female surgical faculty and residents report that gender limits promotion. An 11-question survey sent to all faculty in the section of Surgical Sciences and to all general surgery residents yielded one statistically significant difference in responses between men and women (men, n = 32; women, n = 16; response rate, λ = 0.625; p = 0.01).

DISCUSSION

It has been said that the long-term success of academic health centers is linked to the development of women leaders, and it is estimated that $8 billion are spent annually on diversity training.4,11 In fact, Jordan Cohen, past president of the AAMC, stated:

Cultivating diversity in our faculty and in our leadership is an indispensable strategic instrument for meeting the challenges that academic medicine faces in the 21st century. Grooming women for leadership positions and eradicating the barriers currently impeding their success are essential components of this strategy. Those institutions that fail to seize the advantages offered by elevating talented women to positions of power are destined to be eclipsed by those that do.12

The data presented suggest that a gender bias exists in promotions in academic medicine and that, despite increasing numbers of women completing surgical residencies, these women are not (yet) advancing to the ranks of full professors of surgery (Figs. 2 and 3). In fact, there have been no changes in the representation of women in academic surgery at each faculty rank nationally over the last 15 years (Fig. 3). This trend is consistent with almost 20 years of national data presented by Nonnemaker6 in 2000 for academic medicine. Effectively, this suggests that the proportional representation of women in professorial ranks in surgery has been largely unchanged for the last 35 years, even though the absolute number of women in academic surgery is increasing.

Examining this even more, linear regression revealed that the medical school graduates and surgical residency graduates are increasingly gender balanced (0.75, R2 = 0.97 and 0.99, R2 = 0.98 respectively), with full professors lagging behind (0.36, R2 = 0.93) (Fig. 2). Previous reports and current reviews have demonstrated that women enter academic medicine as faculty members in numbers equal to men.13,14 Our data indicate that the increased percentage of graduating medical students who are women approximates, or impacts directly, the percentage of graduating surgical residents who are women. Thus, if the numbers of men and women entering academic medicine are similar among surgery residents, as suggested by the literature, it is a reasonable conclusion that women are not advancing to leadership positions in academic surgery. The lack of advancement of women in academic surgery is consistent with published reports demonstrating the lack of advancement of women in academic medicine more generally.4,7,14-16 The question of why this is happening remains, and these data do not provide insight into the etiology of this phenomenon.

To investigate the reason behind these trends, we surveyed the general surgery faculty and general surgery residents at our institution (Fig. 1) and found that women were significantly more likely than men to believe that gender limits their chances for promotion (Fig. 6; p < 0.001). Interestingly, women and men were equally likely to believe that the smaller number of women in surgery was not limiting women’s advancement. In fact, in the specialty of obstetrics and gynecology, where women compose 51% of academic faculty, we observed the same advancement trends as in surgery (AAMC data not shown).

An interesting finding from our survey is that all participants agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that the leadership structure in academic surgery is hierarchical. Hierarchy is an organizational structure in which every entity in the organization, except one, is subordinate to a single other entity.17 Hierarchical organization has been identified as a potential barrier to the advancement of women in academic medicine.17 Kanter argued that, in business organizations, employee behavior is determined by the structure of the organization rather than by the intrinsic character of employees themselves.18 Limited access to advancement possibilities and resources, support, and information related to one’s occupation is associated with higher levels of job strain and burnout and with lower levels of work satisfaction, commitment to an organization, and trust in management.19-23

These findings are particularly important when most department chairs and division chiefs in surgery have indeterminate tenure. Indeterminate tenure creates multiple obstacles to advancement, including lack of transparency and exclusion of department members from decision making, and it results in a bottleneck for advancement opportunities to the department chair and division chief level. This bottleneck seems to affect women more than men.17 In business, the typical chief executive officer has a tenure of fewer than 7 years, and the percent annual turnover has been increasing since 1992.24 The average tenure of surgical department chairs is 9.6 years ± 7.8 years, and 37.5% of chairs surveyed in a recent study had held their position for more than 10 years.25 Perhaps if we change the structure of the surgical work environment by eliminating the hierarchy and placing term limits on leadership positions, then multiple factors could be corrected, potentially leading to the abolition of gender disparity in surgical leadership positions.

LIMITATIONS

In Fig. 2, we report total percentages of graduating medical school, surgical residents, and full professors in surgery who are women. More precise data would include the percentage of those entering academic surgery after residency that are women and the number or percentages of graduating medical students entering a surgical residency. In the reports we examined from the AAMC, these data were unavailable. It has been reported previously that, in recent years, men and women enter academic medicine at similar rates; we believe this evidence supports our conclusions about possible barriers to women’s advancement in academic surgery.13

Additionally, our data do not contain any attrition rates for women (or men) in the surgical specialties listed. Previous cohort comparisons have examined the proportions of women remaining on academic faculty long enough that they would be considered for advancement.6 We did not attempt to obtain these data for surgery specifically because all the trends across academic medicine were similar in our analysis to those previously reported by Nonnemaker.6

Furthermore, it has been reported that salary disparities exist between men and women of similar rank in academic surgery.14 One postulation is that women are choosing a prolonged career path. We attempted to obtain these data from VUMC; however, all current women faculty have advanced through the traditional track (eg, consistently working full rather than part time).

CONCLUSIONS

Women are not advancing to the senior ranks of academic surgery, despite increasing numbers of women entering the surgical field. One possible source of this trend is the hierarchical leadership structure present in academic surgery and practices that undergird women’s perception that their gender hinders their advancement. Subsequent research is needed to explore hierarchy and other factors as possible reasons for women’s relative absence in the senior ranks and to devise effective interventions.

Acknowledgments

Supported by Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research Grant 1 UL1 RR024975 from the National Center for Research Resources/National Institutes of Health for the use of the REDCap software.

Footnotes

COMPETENCIES: Systems Based Practice, Professionalism, Practice Based Learning and Improvement

REFERENCES

- 1.McCann KS. The diversity-stability debate. Nature. 2000;405:228–233. doi: 10.1038/35012234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roth N. The personalities of two pioneer medical women: Elizabeth Blackwell and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1971;47:67–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wyrzykowski AD, Han E, Pettitt BJ, Styblo TM, Rozycki GS. A profile of female academic surgeons: training, cre-dentials, and academic success. Am Surg. 2006;72:1153–1157. discussion: 1158-1159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bickel J, Wara D, Atkinson BF, et al. Increasing women’s leadership in academic medicine: report of the AAMC Project Implementation Committee. Acad Med. 2002;77:1043–1061. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200210000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carr PL, Friedman RH, Moskowitz MA, Kazis LE. Comparing the status of women and men in academic medicine. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:908–913. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-9-199311010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nonnemaker L. Women physicians in academic medicine: new insights from cohort studies. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:399–405. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002103420606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tesch BJ, Wood HM, Helwig AL, Nattinger AB. Promotion of women physicians in academic medicine. Glass ceiling or sticky floor? JAMA. 1995;273:1022–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yedidia MJ, Bickel J. Why aren’t there more women leaders in academic medicine? The views of clinical department chairs. Acad Med. 2001;76:453–465. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200105000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leadley J. Women in U.S. Academic Medicine: Statistics and Benchmarking Report 2008-2009. Association of American Medical Colleges; Washington, DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansen F. Diversity’s business case doesn’t add up. Work-force. 2003;2832 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen JJ. Women in medicine, much progress, much work to do. AAMC Rep. 2001;2 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ash AS, Carr PL, Goldstein R, Friedman RH. Compensation and advancement of women in academic medicine: is there equity? Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:205–212. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-3-200408030-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schroen AT, Brownstein MR, Sheldon GF. Women in academic general surgery. Acad Med. 2004;79:310–318. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200404000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carnes M, Morrissey C, Geller SE. Women’s health and women’s leadership in academic medicine: hitting the same glass ceiling? J Womens Health. 2008;17:1453–1462. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nickerson KG, Bennett NM, Estes D, Shea S. The status of women at one academic medical center. Breaking through the glass ceiling. JAMA. 1990;264:1813–1817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conrad P, Carr P, Knight S, et al. Hierarchy as a barrier to advancement for women in academic medicine. J Womens Health. 2010;19:799–805. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Men KRM. Women of the Corporation. Basic Books Inc.; New York: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kluska KM, Laschinger HK, Kerr MS. Staff nurse empowerment and effort-reward imbalance. Nurs Leadersh. 2004;17:112–128. doi: 10.12927/cjnl.2004.16247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laschinger HKF, J Shamian J. Promoting nurses’ health: effect of empowerment on job strain and work satisfaction. Nurs Econ. 2001;19:42–58. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laschinger HKF, J Shamian J. The impact of wokplace empowerment, organizational trust on staff nurses’ work satisfaction and organizational commitment. Health Care Manag Review. 2001;26:7–23. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laschinger HKF, J Shamian J, Wilk P. Workplace empowerment as a predictor of nurse burnout in restructured healthcare settings. Longwoods Rev. 2003;1:2–11. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson B, Laschinger HK. Staff nurse perception of job empowerment and organizational commitment. A test of Kanter’s theory of structural power in organizations. J Nurs Adm. 1994;24(suppl 4):39–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaplan SN, Minton B. How has CEO turnover changed? Increasingly performance sensitive boards and increasingly uneasy CEOs; National Bureau of Economic Research; Working Paper 12465; Cambridge, Mass: National Bureau of Economic Research. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurichi JE, Sonnad SS. Authorship patterns of surgical chairs. Surgery. 2007;141:267–271. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]