Abstract

Objective

While research has documented heavy drinking practices and associated negative consequences of college students turning 21, few studies have examined prevention efforts aimed to reduce high-risk drinking during 21st birthday celebrations. The present study evaluated the comparative efficacy of a general prevention effort (i.e., BASICS) and event specific prevention in reducing 21st birthday drinking and related negative consequences. Furthermore, this study evaluated inclusion of peers in interventions and mode of intervention delivery (i.e., in-person vs. web).

Method

Participants included 599 college students (46% male) who intended to consume at least five/four drinks (men/women respectively) on their 21st birthday. After completing a screening/baseline assessment approximately one week before turning 21, participants were randomly assigned to one of six conditions: 21st birthday in-person BASICS, 21st birthday web BASICS, 21st birthday in-person BASICS plus friend intervention, 21st birthday web BASICS plus friend intervention, BASICS, or an attention control. A follow-up assessment was completed approximately one week after students’ birthdays.

Results

Results indicated a significant intervention effect for BASICS in reducing blood alcohol content reached and number of negative consequences experienced. All three in-person interventions reduced negative consequences experienced. Results for the web-based interventions varied by drinking outcome and whether or not a friend was included.

Conclusions

Overall, results provide support for both general intervention and ESP approaches across modalities for reducing extreme drinking and negative consequences associated with turning 21. These results suggest there are several promising options for campuses seeking to reduce both use and consequences associated with 21st birthday celebrations.

Keywords: Alcohol, alcohol-related problems, college students, event-specific drinking, event-specific prevention, 21st birthday

To further improve alcohol prevention strategies for college populations, recent research has begun to evaluate Event Specific Prevention (ESP) efforts (Neighbors et al., 2007). Unlike general prevention efforts, ESP takes advantage of our knowledge regarding the severity and timing of specific events in which drinking is particularly extreme (e.g., 21st birthday celebrations, Spring Break, holidays, specific sporting events, Neighbors et al., 2007). The current study is an empirical evaluation of ESP, when delivered in-person or via the web, in comparison to general prevention efforts. Furthermore, the current study is an evaluation of the potential role of including friends in ESP.

Event Specific Prevention

Event specific prevention is a relatively new prevention paradigm (Neighbors et al., 2007) with roots in traditional college student alcohol interventions (e.g., BASICS; Dimeff, Baer, Kivlahan, & Marlatt, 1999). A substantial body of work has found individually focused feedback-based alcohol interventions to be effective in reducing college student alcohol consumption (for reviews see Carey, Scott-Sheldon, Carey, & DiMartini, 2007; Larimer & Cronce 2007; Walters & Neighbors, 2005). These interventions have traditionally focused on general drinking patterns and evaluations have typically assessed quantity and frequency of consumption and/or number and severity of consequences over some extended period of time (Baer et al., 1992; Borsari & Carey, 2000; Larimer et al., 2001; Marlatt et al., 1998; Neighbors et al., 2004). While effects of these interventions have been encouraging, prevention efforts that have focused on general drinking practices have not targeted potentially dangerous drinking that occurs during specific events associated with high risk drinking. These events include 21st birthdays, Spring Break, New Years, Halloween, St. Patrick’s Day, and others (Del Boca, Darkes, Greenbaum, & Goldman, 2004; Greenbaum, Del Boca, Darkes, Wang, & Goldman, 2005; Neighbors, Atkins, et al., 2011).

Several aspects of event specific drinking make them amenable to targeted interventions. First and foremost, they can be anticipated. Intervention providers know precisely when most specific events will occur far in advance (e.g., 21st birthdays and Spring Break). Second, specific events are usually time limited. Prevention efforts and resources can therefore be precisely timed prior to a given event and terminated at the conclusion of the event. Third, students may see specific events as inherently different from typical drinking. For example, students have different perceptions regarding norms for drinking on 21st birthdays than on typical occasions (e.g., Lewis, Neighbors, Lee, & Oster-Aaland, 2008; Neighbors, Bergstrom, Oster-Aaland, & Lewis, 2006), which argues for the potential effectiveness of providing 21st birthday specific norms (Lewis et al., 2008; Neighbors, Lee, Lewis, Fossos, & Walter, 2009). Fourth, event specific interventions which are found to be effective in targeting one specific event might be readily modified for addressing other similar events. Finally, event specific efforts might be considered as adjunct interventions to supplement ongoing efforts which target drinking more generally. Recent research suggests that 21st birthdays are a strong candidate for initial efforts in evaluating event specific prevention efforts.

21st Birthday Drinking

Extreme drinking associated with 21st birthday celebrations has received increasing attention in recent years. On their 21st birthday, approximately 90% of college students report consuming alcohol and reach an average blood alcohol concentration of .186 (Neighbors, Spieker, Oster-Aaland, Lewis, & Bergstrom, 2005; Neighbors, Atkins et al., 2011). A majority of students drink more than they intended to drink (Brister, Wetherill, & Fromme, 2010). Among those students who do drink, as many as 12% report consuming 21 or more drinks and approximately half consume more alcohol on this occasion than on any previous occasion (Rutledge, Park, & Sher, 2008). Alcohol-related consequences for 21st birthday drinking are quite prevalent with estimates for vomiting, hangovers, and blackouts ranging from 30 to 50% (Lewis, Lindgren, Fossos, Neighbors, & Oster-Aaland, 2009; Wetherill & Fromme, 2009). A higher proportion of students consume alcohol on 21st birthdays and reach higher estimated blood alcohol concentrations than on any other specific event (e.g., New Years, Spring Break, July 4th, St. Patrick’s day, etc.; Neighbors, Atkins et al., 2011).

21st Birthday Drinking Interventions

Interventions specifically targeting 21st birthday drinking were pioneered by Cindy McCue and colleagues at Michigan State University, who developed the Be Responsible About Drinking (B.R.A.D.) program. The program was inspired by Bradley McCue who died after consuming 24 drinks on his 21st birthday. The program consisted of sending birthday cards to all MSU students prior to their 21st birthday encouraging moderation and describing the death of Bradley McCue. Several interventions using a birthday card approach have since been evaluated (Glassman, Dodd, Sheu, Rienzo, & Wagenaar, 2010; Hembroff, Atkin, Martell, McCue, & Greenamyer, 2007; LaBrie, Migliuri, & Cail, 2009; Lewis et al., 2008; Neighbors et al., 2005; Smith, Bogle, Talbott, Gant, & Castillo, 2006). By and large, interventions utilizing birthday cards with moderation messages have not been found effective in reducing 21st birthday drinking. For example, Smith et al. (2006) evaluated four birthday cards and found no effects in reducing drinking or consequences. Although some have found significant effects, few have conducted analyses using an intent to treat analytical approach. For example, LaBrie et al. (2009) found reduced drinking and estimated BAC among those who reported drinking and having read the birthday card. Thus, these studies may overestimate the impact of the interventions as, in some cases, fewer than half of all participants responded to the surveys.

Birthday card interventions typically include limited content which is generic and not tailored to participants. More recently, Neighbors and colleagues (2009) evaluated a comprehensive web-based feedback intervention targeting 21st birthday drinking. Feedback was modeled after the BASICS intervention (Dimeff et al., 1999) but was specific to 21st birthday drinking. In contrast to birthday card interventions, this approach was associated with a significant reduction in 21st birthday BACs but did not examine whether there were also reductions in drinking consequences associated with the 21st birthday celebration. Across the research conducted to date, two factors which have not previously been considered in the context of 21st birthday drinking interventions include the influence of friends on intervention outcomes and mode of intervention delivery.

The Influence of Friends and Peers on Drinking

Direct influence from peers and modeling are social factors that may be relevant in explaining drinking at the situational level (Borsari & Carey, 2001; Graham, Marks, & Hansen, 1991). Direct peer influences, including overt suggestions or offers to drink (e.g., being given an unsolicited drink by a friend), are associated with heavier and more problematic drinking (Wood, Read, Palfai, Stevenson, 2001). Research on peer modeling revealed individuals consume more alcohol in situations where others are drinking more (Caudill & Marlatt, 1975; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985; Quigley & Collins, 1999). Furthermore, research has shown that close friends have a strong influence on drinking behavior. The perception of best friend’s drinking is more strongly associated with drinking than perceptions of students in general (Baer & Carney, 1993; Baer, Stacy, & Larimer, 1991; Thombs, Olds, & Ray-Tomasek, 2001). Moreover, motivations for best friends’ drinking are uniquely associated with one’s own drinking, over and above one’s own reasons for drinking (Hussong, 2003). Given these findings, is seems likely that friends would play a particularly important role in specific situations with strong social expectations for heavy drinking (i.e., 21st birthday celebrations), given the inherently social nature of these events.

While friends’ influence on drinking is typically presented in the BASICS intervention (Dimeff et al., 1999), existing interventions rarely incorporate the influence that friends have on drinking directly (e.g., recruiting friends to administer/support intervention efforts). Although in the adolescent literature, iatrogenic effects of including peers in interventions have been suggested (Dishion, McCord, & Poulin, 1999), meta-analytic review provides little empirical basis for this contention (Weiss et al., 2005). Furthermore, in the adult treatment literature friends and significant others have routinely been successfully incorporated in alcohol treatment (Copello et al., 2002; Longabaugh, Wirtz, Beattie, & Noel, 1995; Longabaugh, Wirtz, Zweben, & Stout, 1998; McCrady, 2004). However, with few exceptions, friends have not been directly incorporated in college student alcohol interventions. The work of O’Leary Tevyaw and colleagues (O’Leary et al., 2002; Tevyaw, Borsari, Colby, & Monti, 2007) provides an exception and demonstrates both the feasibility and promise of incorporating friends in brief interventions. For example, a peer-enhanced motivational intervention had larger effects on both drinking quantity and frequency when compared to an individual motivational intervention (Tevyaw et al., 2007). This particular peer intervention was delivered in-person to the student and the student’s peer in the same session. Research has yet to evaluate the delivery of an intervention to a student’s peer in a session separate from the student receiving the intervention.

In-person vs. Web-based Brief Interventions

In-person brief motivational interventions, utilizing personalized feedback as a major component, have been efficacious in reducing alcohol use and negative consequences in college students (e.g., Borsari & Carey, 2000; Larimer et al., 2001, 2007; Marlatt et al., 1998). Recently, the efficacy of personalized feedback in the absence of in-person MI sessions in reducing alcohol use and negative consequences has been established using the Internet (e.g., Bewick, Trusler, Mulhern, Barkham, & Hill, 2008; Doumas, McKinley, & Book, 2009; Neighbors et al., 2009, 2010; Neighbors, Jensen et al., 2011; Riper et al., 2008). For college students, Internet-based interventions allow for anonymity, economy of time, and convenience of access (Koski-Jannes & Cunningham, 2001; Kypri, Saunders, & Gallagher, 2003). When deciding between reading materials, health education seminars, Internet-based assessments, or assessments by a professional, the majority of college problem drinkers selected Internet-based assessments as the most appealing intervention (Kypri et al., 2003). Thus, for prevention efforts, offering an online intervention may be an effective means of broadly disseminating preventive interventions and reducing barriers at relatively low individual cost. This may be especially relevant for ESP given that these events can be predicted and that the interventions may be time-sensitive. Alternative to web-based personalized feedback interventions, in-person interventions may have benefits for alcohol users, due to the enhanced ability to discuss and process resistance to change, presenting skills components tailored to the individual, challenging expectancies, and highlighting discrepancies between ideal and actual behavior in relation to personal goals (McNally, Palfai, & Kahler, 2005; Miller & Rollnick, 2002). Little research has directly compared feedback alone to feedback in the context of an in-person interview (Murphy et al., 2004; Walters, Vader, Harris, Field, & Jouriles, 2009). Results of these two studies were inconclusive with respect to differential efficacy of web-based feedback versus in-person feedback.

The Present Study

The present study provides an important test of ESP in comparison to assessment only and to a standard intervention which is not focused on a specific event (i.e., BASICS) in reducing 21st birthday drinking and related negative consequences. Furthermore, this study will be the first to evaluate the role of peers in both ESP and general preventative efforts. In addition to examining differences of active treatment conditions with control, we expected the specific event focus of the 21st birthday BASICS delivered via the web and in-person would be more efficacious at reducing 21st birthday drinking and consequences relative to the more general BASICS and control. When evaluating the two 21st birthday BASICS interventions, although previous research has not been conclusive, we tentatively expected the in-person intervention to be more efficacious at reducing 21st birthday drinking and consequences in relation to the web-based intervention. We further expected, based on the influence of friends, that 21st BASICS (both in-person and web) with the addition of a peer-based intervention would be more efficacious than conditions without peers included.

Method

Participants

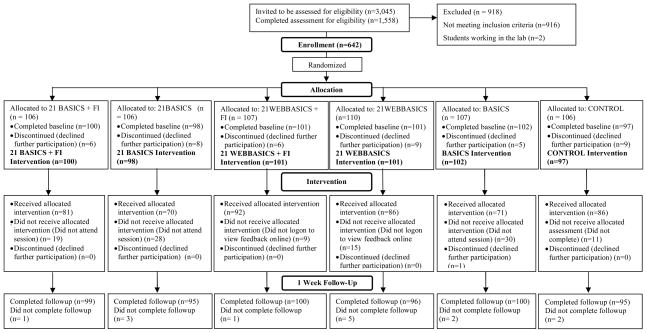

Participant flow through the study is presented in Figure 1. Participants for the present study included 599 college students turning 21 at a large public northwestern university who reported intent to engage in heavy drinking on their 21st birthday. Demographic characteristics included 68.1% White, 15.9% Asian, 7.7% Multi-Ethnic, and 8.3% other and 53.9% women.

Figure 1.

Participant flow

Screening and Recruitment of Participants

A list of all undergraduate students turning 21 between December 2008 and December 2009 was obtained from the university registrar. Invitations to participate in a brief online screening survey were sent to all students turning 21 (N=3,043) one month prior to their 21st birthday by email and U.S. mail. Inclusion criteria for the longitudinal trial was: 1) intending to consume 4 (for women) or 5 (for men) drinks during their 21st birthday; 2) listing the email address of at least one friend, 18 years or older, with whom they planned to celebrate their birthday; and 3) having not previously participated in the study as a friend (see details of friend procedures below). The present study utilized data from two types of people, referred to as Participants (i.e., those who are turning 21) and Friends (i.e., those who were listed by a Participant as being a supportive friend and who will be present at the 21st birthday celebration). Of the 3,043 invited students, 1,558 (51.2%) completed the screening assessment and 642 (41.2%) met screening criteria and were invited to participate in the longitudinal 21st birthday study. Of these 599 (93.3%) completed the baseline assessment. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board and a Federal Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained.

Design

Upon completion of the screening survey, Participants were automatically randomized to one of six conditions. The design for the present trial could be described as a 2 (21 Birthday BASICS In-person or Web-based) × 2 (Friend [FI] or No Friend) + 1 (General BASICS) + 1 (Assessment Only Control) design. Randomization was stratified by gender and drinking severity to ensure equivalence of groups.

Participant Procedures

Upon completion of the baseline survey Participants randomized to the in-person interventions (i.e., 21 BASICS, 21 BASICS + Friend, BASICS) were routed to schedule their intervention session (which included a post-intervention assessment). Participants in the Web-intervention conditions received an email two days before their birthday containing a link to personalized feedback based on their prior survey responses and the brief post-intervention assessment. Participants randomized to the control condition received an email two days before their birthday containing a link to a brief survey to assess their satisfaction with the prior assessments. All participants were invited to complete assessments 1-week post birthday. Incentives for participation were $10 for screening survey, $30 for baseline, and $10 for post-intervention and $30 for the post-21st birthday 1-week follow-up.

Friend Procedures

In the initial screening survey, all study participants were told that we were interested in examining how friendship relates to 21st birthday celebrations and that we would like to contact friends for a random portion of participants. Participants provided contact information for up to 3 friends who they could count on for watching out for them on their 21st birthday. Attempts were made to recruit up to two friends to increase active help for the participant in avoiding alcohol-related negative consequences during the birthday celebration. The nominated friends of participants in the 21 BASICS + FI or 21 WEB BASICS + FI were sent an email prior to the participant’s 21st birthday. This email stated that his/her friend is celebrating their 21st birthday in a few weeks and named them as a good friend to be counted on to watch out for them on their 21st birthday. The email included the purpose of the study, what would be asked of the participant (i.e., Friend), rights as human subjects participants, and instructions. Of the 201 participants randomized to friend conditions who completed baseline, 383 friends were invited and 283 friends provided consent for participation (139 friends to 91 participants in 21BASICS + FI and 144 friends to 97 participants in 21 WEB BASICS + FI). Of those 283 friends who consented to participate, 241 actually logged in to view the online feedback intervention (85.1%). Friends received brief web-based materials on helping the participant have a safe and fun 21st birthday celebration and were paid $20 for completion of the Friend pre-birthday survey.

Intervention Descriptions

The content and process of all interventions were modified from methods developed and tested by Marlatt and colleagues (Baer et al., 1992; Larimer et al., 2001; Marlatt et al., 1998) and described in detail in the BASICS manual (Dimeff et al., 1999). The interventions were non-confrontational in tone, sought to increase motivation to reduce drinking, and were based on the information provided during the baseline assessment. The BASICS intervention consisted of a one-hour session conducted by a trained facilitator in the spirit of Motivational Interviewing (MI; Miller & Rollnick, 2002) and utilized personalized feedback which included summaries of drinking behavior, related consequences, and normative perceptions of alcohol use among peers, as well as other content areas related to alcohol use such as providing protective behavioral strategies and targeting alcohol expectancies, to prompt discussion of general alcohol use with the goal of motivating readiness to change drinking, The BASICS condition did not review any content specific to 21st birthday drinking. Descriptions of each intervention condition and specific procedures are presented below. Please refer to the description of personalized feedback in 21 BASICS as reference for all birthday specific conditions, as the only variation was whether feedback was presented in person (21 BASICS and 21 BASICS + FI) or on the web (21 WEB BASICS and 21 WEB BASICS + FI). The friend intervention is described separately.

21 BASICS

The 21 BASICS feedback interview with a trained facilitator consisted of a one-hour, individual intervention based on the information provided during the screening and baseline assessment. Content included personalized feedback regarding intended drinking quantity, frequency, peak alcohol consumption, and estimated BAC based on gender, consumption, and reported duration of drinking episodes for 21st birthday celebrations. Heavy drinking intentions were targeted both directly through normative feedback focused on participants 21st birthday drinking intentions and indirectly through attempting to increase perceived likelihood of experiencing unpleasant unintended consequences at intended BACs. Factors affecting BAC were also discussed in reference to explaining individuals’ risk for intoxication based on intentions to drink during 21st birthday celebrations. Students’ intended drinking was compared to their estimates of norms (i.e., what they believed other students to drink on 21st birthdays) and to the actual norm on the campus. Risks for alcohol problems and outcome expectancies specifically related to 21st birthday drinking were reviewed and discussed. Participants were invited to explore alternatives to alcohol use during 21st birthday celebrations. All participants took home a copy of their graphic feedback, as well as a miniature BAC card personalized based on their weight and gender, and ‘tips’ summarizing the alcohol education and skills-training components of the interview. Students were paid $10 for completing a participant satisfaction survey online, immediately following the feedback interview.

21 WEB BASICS

The 21 WEB BASICS intervention consisted of the exact feedback and tip components as the 21 BASICS individual intervention, but was presented in a web-compatible format two days prior to the 21st birthday. Participants assigned to this condition were able to view the feedback as often as they chose and could print the feedback if desired.

Friend Intervention

Half of all students randomized to 21 BASICS and 21 WEB BASICS also were randomized to the Friend Intervention (FI). Friends were invited via email to participate in a study about 21st birthdays and were informed that their friend (i.e., the Participant) had given their name to us as someone whom they would be celebrating with. Friends who accessed the website and provided consent for participation viewed online information about general tips for helping ensure a safe and fun 21st birthday celebrations two days before the Participant’s birthday. The webpage Friends saw included information regarding the assessment of standard drinks (i.e., definition and calculating standard drinks), information for calculating BAC and encouragement to discuss with the Participant how much they intend to drink and over what course of time and their desired experiences (e.g., avoiding blacking out, hangovers, etc). Content also included descriptions of typical consequences experienced at given BAC levels; signs of alcohol poisoning; and celebration tips and strategies focused on strategies to engage in prior to going out for the birthday celebration (e.g., eating before drinking, setting a limit, planning safe transportation) and during the birthday celebration (e.g., keeping track of the number of drinks the friend drank, pacing your friend, making sure the friend drinks water, etc.). Friends were encouraged to let other people know early on that they are watching out for the celebrant and to enlist the help of others to ensure a safe and enjoyable birthday. Additionally, Friends were provided personalized information about their intended drinking on the Participant’s birthday (e.g., “You mentioned that you plan to consume 15 drinks in 6 hours which, given your reported weight and gender, would put you at a blood alcohol content of 0.2), as well as the length of time it would take for their intended BAC to return to zero, and potential effects from alcohol at their intended levels of drinking. A personalized BAC chart for the Friend was provided. Friends completed a survey, which mirrored the participant’s survey, viewed feedback, and completed a short satisfaction survey, after which they were paid $20.

Control

Students randomized to the control group only received assessments.

Selection, Training, and Supervision of Intervention Facilitators

Trained intervention providers served as facilitators to provide the in-person interventions. Facilitators had to demonstrate adequate adherence and competence in mock intervention sessions prior to conducting any interventions. Adherence and competence measures were designed to assess warmth, empathy, interpersonal communication style consistent with MI (Miller and Rollnick, 2002), knowledge of the intervention, and qualities shown to be important to effective peer-counseling (Forrest, Strange, & Oakley, 2002). Facilitators participated in a two-day training on MI and BASICS content, watched examples of BASICS and MI interventions, and conducted practice exercises. Facilitators assigned to birthday specific interventions also received training specific to 21st birthdays. Each facilitator participated in additional supervised practice and completed a role-play session to demonstrate competency. Each interviewer was assigned a pilot case which was coded for adherence and reviewed by a supervisor who provided detailed feedback. Ongoing, weekly group supervision further ensured adherence.

Monitoring of Adherence/Competence

All BASICS (specific and non-specific) sessions were video-taped and rated for adherence and competence by trained coders supervised by the investigators. Sessions were rated using the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity system (MITI) developed at the University of New Mexico (Moyers, Martin, Manuel, Hendrickson, & Miller, 2005). Specifically, tapes were coded by a team of six supervised graduate and undergraduate students using the MITI system for interviewer global ratings (empathy, MI spirit) as well as behaviors (MI adherent and non-adherent statements, open and closed questions, and simple and complex reflections). Inter-rater reliability for coders was high (Intraclass correlations’ ranged from .78 – .98) for a majority of the behavioral counts and global codes. Facilitator adherence for each of the global codes exceeded competency criteria (Empathy, M=5.19, SD=.57 and Spirit, M=5.27, SD=.66). Participants also indicated significantly higher intervention satisfaction (e.g., found information interesting, convincing, etc.) for in-person sessions, as compared to those who received their feedback via the web.

Online Feedback Participation and Satisfaction

Most participants and friends who were assigned to log in and view feedback did so. Specifically, 93% of the 21 WEB BASICS and 91% of the 21 WEB BASICS + FI participants logged in to view the feedback. Likewise, 60% of the friends assigned to the 21 BASICS + FI and 66% of the 21 WEB BASICS + FI participants logged in to view the feedback. Unfortunately, while we did assess the length of time participants viewed the feedback, the time variable ended up being unreliable due to the tracking of the entire length a participant may be logged on to a page but not actually viewing feedback (e.g., multiple browser windows open, taking phone calls, leaving the computer when the webpage is still open).

For both the online and the in-person intervention, participants were asked to complete a satisfaction measure immediately following the intervention. Results revealed significantly higher intervention satisfaction ratings for those participants who attended an in-person session, as compared to those who received their feedback via the web, t (402) = 8.16, p < .001.

Measures

Measures included in the present analyses focused on evaluating intervention efficacy. Thus, measures of intended and actual alcohol consumption, intended and actual blood alcohol content (BAC), and alcohol-related consequences during the 21st birthday were assessed.

21st Birthday Drinking Intentions

A modified version of the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins et al., 1985; Dimeff et al., 1999) was used to assess the number of drinks participants intended to consume on each day of the week of their 21st birthday (3 days before to 3 days after). Participants were also asked to report the number of hours they intended to drink for each of the seven days.

Intended BAC

A widely used modification of the Widmark formula (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 1994) was used to estimate intended BAC based on the number of drinks, length of time consuming alcohol, gender, and weight. In the present analyses, estimated BACs Windsorized with values above .50 were recoded to .50.

Likelihood of Alcohol-Related 21st Birthday Consequences

A subset of 10 items taken from a modified version of Young Adult Alcohol Problems Screening Test (YAAPST; Hurlbut & Sher, 1983) was used to assess likelihood of experiencing alcohol-related consequences during the 21st birthday week. The 10 items included in the scale were selected based on a pilot study and were the items participants most frequently endorsed experiencing over their 21st birthday week (α=.79). Examples of items are “You will feel very sick to your stomach or throw up after drinking”, “You will drive a car when you know you had too much to drink”, and “You will become rude, obnoxious, or insulting after drinking”. Scale responses ranged from 0 = Very unlikely – won’t probably happen to 4 = Very Likely – Will probably happen.

21st Birthday Drinking

The measure of 21st birthday drinking mirrored the measure of intended 21st birthday drinking but asked for reports of participants’ actual drinking rather than intentions. Number of drinks on 21st birthday was scored as the number of standard drinks participants reported drinking on their 21st birthday. BAC on 21st birthday was calculated using a modified version of the Widmark formula described above (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 1994).

21st birthday alcohol-related consequences

The ten alcohol-related consequences, matching the likelihood measure, were assessed for whether they happened because of drinking on the 21st birthday (α=.75). Three of the consequences were assessed for the day after the 21st birthdays (Headache morning after, late for work next day, could not remember night before). Scores reflected the number of consequences experienced with a possible range of 0 to 10.

Satisfaction

Satisfaction was assessed by seven items (α = .86). Response options ranged from 0 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Example items were “I liked the message presented in the information” and “I found the information compelling.”

Results

Analyses

Treatment differences were examined using intent-to-treat analyses of three outcomes: a) total number of alcohol drinks on the 21st birthday, b) estimated peak blood alcohol content (eBAC) on the 21st birthday, and c) total number of drinking-related consequences on the 21st birthday (e.g., vomiting, hangover, arrested). Total drinks and total consequences are both count outcomes, as they can only assume non-negative integer values and were highly skewed. In addition, consequences had a notable stack of values at zero. Moreover, count outcomes typically have higher variability at greater mean levels of the outcome, and all of these characteristics will lead to violations of the model assumptions underlying ordinary least squares regression. A common approach to count outcomes is to use Poisson regression; however, count variables are often “over-dispersed” relative to the Poisson distribution, which assumes that the mean is equal to the variance (i.e., oftentimes the variance far exceeds the mean). For these reasons, we used a negative binomial regression model as our primary statistical model in the present analyses for total drinks and total consequences (see, e.g., Atkins & Gallop, 2007; Hilbe, 2011). eBAC also had a skewed distribution. We examined different models including those where we transformed the outcome to reduce skew-kurtosis to acceptable levels as well as using an alternative probability model without normality assumption. In the end, substantive results were consistent across models, and ordinary least squares regression was used to ease interpretation. All models included gender and drinking-related intentions assessed at baseline as covariates. Our primary regression models took the following form:

| (1) |

That is, the outcome on the 21st birthday was modeled by the participant’s intended outcome (e.g., intended total drinks on birthday), gender, and five dummy-coded treatment contrasts that compared each active treatment to the control condition. The intentions covariate was centered around its mean, and gender was contrast coded (Men = −0.5, Women = 0.5) so that the intercept can be interpreted as the average outcome for control participants. In addition, after models were fit, linear contrasts compared coefficients from the conditions including 21st birthday specific content with Control and BASICS conditions (as a test of the event-specific intervention hypotheses).

Four of the treatment conditions represent a 2 × 2 design (i.e., in-person vs. web-based and solo vs. friend participation). A second set of analyses focused on just these four conditions and tested main effects of in-person and friend participation. For interpretation, negative binomial regression uses a log link function, and similar to logistic regression, raw coefficients are exponentiated (i.e., raised to the base e) and interpreted as rate ratios (RR). An RR of one indicates no effect, and RRs smaller or larger than one indicate the percentage reductions or increases in the outcome. Analyses adhered to the intent-to-treat principle and analyzed all available data treating individuals as randomized, regardless of treatment received. All analyses were done in R v2.12.0 (R Development Core Team, 2010) and made use of the glm.nb() function for negative binomial regression in the MASS package.

Descriptive Results

On average, participants intended to drink about 10 drinks on their 21st birthday (M = 10.13, SD = 5.49). Average intended blood alcohol concentration was approximately .18 (SD = .13). Both of which are consistent with previous reported 21st birthday drinking. Overall, participants rated the probability of experiencing consequences as between ‘unlikely’ and ‘possibly’ (M = 1.39, SD = .61). There were no overall differences in intentions across conditions. Descriptive statistics of participant’s observed drinking and consequences on their 21st birthday are found in Table 1. Effect sizes (d’s) are included representing differences between each condition and control. Effect sizes were all small and in the anticipated direction. Across conditions, students reported drinking approximately 9.5 drinks on their birthday and reaching a BAC of about .17. Thus, overall, participants’ drinking was strikingly consistent with their intentions. Across all conditions participants reported experiencing about 1.5 alcohol-related consequences.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for 21st Birthday-Related Outcomes.

| Intervention Condition | N | M | SD | Zero proportion | d, 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Drinks on 21st Birthday | |||||

| CONTROL | 95 | 10.27 | 7.15 | 0.06 | |

| 21 BASICS + FI | 99 | 9.51 | 5.78 | 0.04 | −0.11 (−0.37, 0.15) |

| 21 BASICS | 95 | 9.92 | 6.90 | 0.02 | −0.05 (−0.32, 0.22) |

| 21 WEB BASICS + FI | 100 | 9.89 | 6.50 | 0.06 | −0.05 (−0.32, 0.21) |

| 21 WEB BASICS | 96 | 9.13 | 6.22 | 0.04 | −0.16 (−0.42, 0.10) |

| BASICS | 100 | 9.06 | 6.59 | 0.07 | −0.17 (−0.44, 0.10) |

|

| |||||

| eBAC on 21st Birthday | |||||

| CONTROL | 95 | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.06 | |

| 21 BASICS + FI | 99 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.04 | −0.17 (−0.46, 0.10) |

| 21 BASICS | 95 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.02 | −0.19 (−0.48, 0.11) |

| 21 WEB BASICS + FI | 100 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.06 | −0.07 (−0.34, 0.21) |

| 21 WEB BASICS | 96 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.04 | −0.24 (−0.52, 0.05) |

| BASICS | 100 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.07 | −0.25 (−0.52, 0.01) |

|

| |||||

| 21st Birthday Alcohol-Related Problems | |||||

| CONTROL | 94 | 1.85 | 1.69 | 0.25 | |

| 21 BASICS + FI | 99 | 1.45 | 1.40 | 0.27 | −0.23 (−0.49, 0.03) |

| 21 BASICS | 95 | 1.45 | 1.57 | 0.36 | −0.23 (−0.51, 0.04) |

| 21 WEB BASICS + FI | 100 | 1.45 | 1.47 | 0.31 | −0.23 (−0.49, 0.03) |

| 21 WEB BASICS | 95 | 1.52 | 1.52 | 0.32 | −0.20 (−0.46, 0.06) |

| BASICS | 100 | 1.39 | 1.28 | 0.28 | −0.27 (−0.51, −0.04) |

Note. Effect size (d) statistics were calculated as mean differences between active treatments and Control, divided by the Control group SD. Confidence intervals were calculated via bootstrapping 5,000 samples. The effect sizes are included as descriptive magnitudes for treatment differences, as the negative binomial regressions make more realistic assumptions for inferential statistics.

Regression Analyses

Regression results for the primary outcomes are reported in Table 2. With respect to number of drinks consumed on 21st birthdays, the control group consumed an average of 9.75 drinks. Intentions were strongly associated with number of drinks and men consumed about 13% more drinks than women. There were no significant treatment differences for total number of drinks relative to control, though the RRs for all active treatment groups are less than one, indicative of fewer total drinks. General BASICS, with a 14% reduction relative to control, revealed a trend at p = .10. Moreover, general linear contrasts showed that intervention conditions including 21st birthday content were not significantly different (as a group) from control (RR = 0.94, CI = 0.82, 1.07) or BASICS (RR = 1.08, CI = 0.96, 1.22).

Table 2.

Regression Results for Treatment Differences on Primary Outcomes (N = 585)

| Number of Drinks on 21st Birthday | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 95% CI | p | ||

| (Intercept) | 9.743 | 8.663 | 10.959 | < .01 |

| Intended Drinks | 1.061 | 1.053 | 1.069 | < .01 |

| Gender | 0.868 | 0.786 | 0.958 | .008 |

| 21BASICS_FRIEND | 0.911 | 0.781 | 1.062 | .288 |

| 21BASICS_SOLO | 0.967 | 0.814 | 1.148 | .703 |

| 21WEBBASICS_FRIEND | 0.987 | 0.839 | 1.161 | .878 |

| 21WEBBASICS_SOLO | 0.885 | 0.749 | 1.045 | .168 |

| GENERAL_BASICS | 0.863 | 0.737 | 1.012 | .096 |

| eBAC on 21st Birthday | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | 95% CI | p | ||

| (Intercept) | 0.205 | 0.179 | 0.232 | < .01 |

| Intended BAC | 0.549 | 0.451 | 0.648 | < .01 |

| Gender | −0.005 | −0.027 | 0.017 | .659 |

| 21BASICS_FRIEND | −0.035 | −0.074 | 0.004 | .079 |

| 21BASICS_SOLO | −0.021 | −0.063 | 0.021 | .293 |

| 21WEBBASICS_FRIEND | −0.009 | −0.045 | 0.028 | .662 |

| 21WEBBASICS_SOLO | −0.049 | −0.088 | −0.01 | .014 |

| GENERAL_BASICS | −0.051 | −0.086 | −0.016 | .009 |

| 21st Birthday Alcohol-Related Problems | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 95% CI | p | ||

| (Intercept) | 1.821 | 1.523 | 2.176 | < .01 |

| Intended Problems | 1.055 | 1.042 | 1.068 | < .01 |

| Gender | 0.926 | 0.795 | 1.079 | .335 |

| 21BASICS_FRIEND | 0.752 | 0.582 | 0.972 | .033 |

| 21BASICS_SOLO | 0.707 | 0.54 | 0.926 | .012 |

| 21WEBBASICS_FRIEND | 0.769 | 0.597 | 0.99 | .050 |

| 21WEBBASICS_SOLO | 0.816 | 0.628 | 1.061 | .130 |

| GENERAL_BASICS | 0.751 | 0.58 | 0.972 | .033 |

Note. RR = Rate ratio; eBAC = estimated blood alcohol content. Gender was contrast coded (Men = −0.5, Women = 0.5), and baseline intention covariates were centered around their respective means. Number of drinks on 21st birthday and alcohol-related consequences on 21st birthday were fit using a negative binomial regression, whereas eBAC was fit using ordinary least-squares regression.

In examining eBAC, intentions were a strong predictor but there was not a significant difference between men and women. Both General BASICS and 21 WEB BASICS condition participants reported significantly lower eBAC on their birthdays relative to control. Control participants had an average eBAC of 0.21, whereas General BASICS and 21 WEB BASICS participants were approximately 0.05 eBAC points lower (or 0.16 on average). The 21 BASICS + FI condition had a smaller effect (B = −0.035) that was close to significance (p = .08). General linear contrasts showed that intervention conditions including 21st birthday content were marginally different (as a group) from control (B = −0.03, CI = −0.06, 0.01, p = .057) and significantly worse than General BASICS (B = 0.06, CI = 0.01, 0.13, p = .045).

Evaluation of 21st birthday alcohol-related consequences again revealed a main effect for intentions but no difference between men and women. In contrast to number of drinks and eBAC, all intervention conditions except 21 WEB BASICS revealed significantly fewer consequences relative to control, with effects ranging from 29% (21 BASICS) to 23% (21 WEB BASICS + FI) reduction. Finally, general linear contrasts showed that intervention conditions including 21st birthday content significantly reduced consequences (as a group) relative to control (RR = 0.81, CI = 0.68, 0.97) but not relative to General BASICS (RR = 1.03, CI = 0.86, 1.25).

As noted earlier, four of the active treatment groups form a 2 × 2 design contrasting solo vs. friend and in-person vs. web. Secondary analyses examined whether there was support for these main effects among these four intervention conditions. There was no evidence for superiority for either effect (i.e., solo vs. friend, in-person vs. web) with all ps > .30 across all outcomes.

Discussion

This study evaluated 21st birthday specific prevention programs to reduce 21st birthday drinking and related consequences among college students. The study is unique in that it compared a general intervention to event-specific interventions, web modalities versus in-person, and addressed whether including friends may provide a means to augment treatment effects. Overall we found that all intervention conditions reported post-birthday drinking behavior and consequences that were lower than controls, although not all conditions reached statistical significance on every outcome. Contrary to our hypotheses, General BASICS, not specifically tailored for the 21st birthday but administered shortly before the birthday celebration, significantly reduced both drinking and consequences, as compared to control. Results for other conditions were less consistent. In reducing BAC, the 21 WEB BASICS intervention, without including friends, significantly reduced BAC in comparison with control. Conversely, in reducing drinking consequences on the 21st birthday, all three in-person interventions significantly decreased consequences as did the 21 WEB BASICS + FI intervention. Contrary to our expectations there was no overall effect for in-person 21st birthday specific interventions as compared to web-based interventions for any of the drinking outcomes, nor was there support overall for the efficacy of enlisting friends as an additional avenue of intervention in reducing drinking. As a group, interventions which included a specific 21st birthday focus did not result in a lower number of drinks relative to control but did result in lower eBAC reached and fewer consequences relative to control. Moreover, BASICS outperformed 21st birthday specific interventions (as a group) in reducing eBAC but was otherwise comparable in performance.

Twenty-first birthday celebrations are an area of public health concern given the high degree of drinking and alcohol-related consequences associated with this particular event. Although other holidays are associated with increased risk of drinking, this particular one is associated with significantly more drinking than others (Neighbors, Atkins et al., 2011). Overall, findings for the efficacy of 21st birthday specific interventions have been mixed (Glassman et al., 2010; Hembroff et al., 2007; LaBrie et al., 2009; Lewis et al., 2008; Neighbors et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2006). Moderation messages delivered as birthday cards have been relatively ineffective (Glassman et al., 2010; Lewis et al., 2008; Neighbors et al., 2005, Smith et al., 2006). Studies that have used web-based or birthday card based interventions incorporating personalized normative feedback or protective behavioral strategies have generally had small but significant effects in reducing BAC (Neighbors et al., 2009). However, none of these studies have examined in-person interventions nor have they compared the interventions to a general, non-tailored treatment. Based on our findings it is unclear whether tailored interventions are necessary in addressing 21st birthday drinking. Both tailored and non-tailored interventions were effective, at least in reducing some 21st birthday-related drinking outcomes. It is possible that the more critical issue is the timing of the feedback to be more proximal to the celebration. It is also important to note that in this study, and other research examining personalized normative feedback, normative information appears to be a crucial component.

Twenty-first birthday celebrations are events that take place within a social context. Given the role that peer models and social norms have on drinking, as well as the strong social component associated with birthday celebrations, it is surprising that there was no overall treatment effect for friends. Friends did appear to be effective in conjunction with the in-person intervention but only in reducing consequences, not in reducing drinking behavior overall. Perhaps friends focused on different ways to reduce harm such as using a designated driver or making sure they got home okay rather than strategies that would reduce drinking. Prior research has shown that students celebrating their 21st birthday are more likely to use protective behavioral strategies aimed at reducing serious harm rather than strategies aimed to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed (Lewis et al., in press). It may be that friends had a similar focus for those who were turning 21 and thus focused on reducing harm rather than reducing drinking. It is important to note that the friend intervention was web-based, thus an experienced facilitator was not working with friends to increase their motivation to help reduce drinking.

Few studies have directly compared comparable interventions across modalities. In-person interventions allow for more customized feedback and a more nuanced approach. Using motivational enhancement strategies, facilitators will tailor the discussion of feedback based on the individuals’ unique response to the intervention. However, in-person interventions are useful only to the extent to which individuals show up for the interventions. They also require a much higher investment of resources; from the training and supervision of facilitators to scheduling and following up with canceled or missed appointments, to maintaining space within which to have intervention sessions. For a time sensitive event like 21st birthday’s some of the issues regarding logistics can be particularly problematic. In contrast, web-based interventions are relatively low cost to administer once the feedback is programmed and are easy to push out to the target population. However, these interventions are somewhat less personalized and do not have the ability to respond to the participant “on the fly” like a human facilitator. Web-based interventions may also be somewhat less engaging. Moreover, it is more difficult to tell how the feedback is being received and to correct any misperceptions. Overall we found that a general in-person intervention was the only intervention to significantly reduce both use and consequences with a 20% reduction in BAC and a 25% reduction in consequences for those students who were randomized to receive the intervention. Both in-person event-specific interventions and web-based interventions that included friends were effective in reducing consequences.

Limitations

Though the current study had several methodological strengths and adds to the emerging literature on 21st birthday drinking prevention, there are several limitations that must be considered. First, the current sample included only college students, and thus it is not known how these results would generalize to 21st birthday drinking among non-college participants. Further, the current study included only those male/female students who reported the intention to consume at least 5/4 drinks on their birthday. Research indicates intentions are related to future drinking behavior (Armitage & Connor, 2001), however it is also likely that some students fail to anticipate the opportunity for excessive drinking on their birthday, and these individuals may be at elevated risk for harmful consequences (Lewis et al., 2009). Thus, future research is needed to evaluate these interventions across the full range of drinking intentions, and with both college and non-college young adults.

A second limitation is that while the in-person interventions in the current study were conducted in a controlled setting in the research lab offices, the web-based interventions were accessed from a variety of locations of participants’ choice, and thus we were unable to control the context in which participants accessed the web nor were we able to control any distractions that may have reduced their attention to the intervention content. While it’s possible that effects for web intervention would have been larger if implemented in a controlled context, the current results likely have greater external validity, more consistent with the anticipated “real world” impact on a typical college campus.

Though involvement of friends in the intervention was a strength of the current research, there are also several limitations related to this aspect of the study. First, friend interventions were all administered via the web, and it is not clear the extent to which friends actually implemented the recommended interventions during the participants’ 21st birthday celebration nor whether those friends who received the intervention actually accompanied participants on their birthday. A more detailed examination of potential moderators of friend interventions is beyond the scope of the present paper but worthy of future attention. Similar limitations as noted above regarding the context in which the friend interventions took place and the extent to which they attended to the intervention are also relevant. Thus, it’s possible that friend intervention effects would have been larger had friends been recruited to attend an in-person rather than web-based intervention. A related issue is the complexity of the design, which may be a strength and a limitation. Future research might consider a more incremental approach with less complexity and greater statistical power versus manipulating multiple factors at the same time.

Implications

Despite limitations, results of the current study are encouraging, and suggest that 21st birthday drinking can be impacted by both in-person and web-based brief interventions implemented just prior to the event. In the current study, the most consistent results were found for the General BASICS intervention, which was related to significantly lower BACs and fewer negative consequences resulting from the 21st birthday celebration. These results suggest that appropriate timing of an evidence-based intervention, rather than tailoring of intervention content per se, may be crucial to addressing 21st birthday drinking. Many campuses already have personnel with expertise in delivery of the General BASICS intervention, and may routinely utilize this approach with high-risk groups including freshman, mandated students, or members of fraternities. Thus, colleges may be able to cost-effectively leverage existing trained BASICS providers to help reduce 21st birthday negative drinking outcomes by providing similar interventions for students approaching their 21st birthday. While it may never be feasible for college campuses to administer in-person 21st birthday interventions to all students, the strong association between intentions and behavior suggests that the students most in need of an intervention could be readily identified. For example, college campuses could take a stepped care approach and send a very brief screening to all students, perhaps with a happy birthday message. Limited resources could then be applied only to those students most in need of an in-person intervention.

Future Directions

The current findings present several avenues for future research. First, longitudinal follow-up is needed to evaluate the extent to which interventions targeting 21st birthday drinking generalize to other high-risk situations such as Spring Break or New Year’s Eve, as well as the extent to which these interventions impact typical drinking behavior (rather than simply event-specific behavior) post-intervention. To the extent that results of these interventions generalize to other situations beyond the specific event, cost-effectiveness of the interventions is increased. Related, it is important to evaluate the extent to which timing of the intervention (i.e., immediately prior to the 21st birthday or at an earlier point in time) impacts drinking on the 21st birthday. Given the time required to implement these interventions, particularly for in-person BASICS, it may be prohibitive to implement such interventions within weeks of the 21st birthday for all students, thus it would be beneficial to understand the relative costs and benefits of intervening at different points in time relative to known high-risk events, in order to maximize resource utilization and intervention impact. It is also possible that general interventions, including BASICS and other empirically supported approaches, might be effective in reducing drinking on specific events without respect to timing. If this proposition is supported in subsequent work, it would provide additional rationale for broad, systematic dissemination of efficient, empirically supported, low-cost interventions in this population.

A second extension of the current findings might be to further explore aspects of participants’ friendships which might enhance or detract from efficacy of interventions including friends. For example, supportiveness of friendships and/or friends’ attitudes toward or perceived norms regarding alcohol may be influential in determining the extent to which including friends in the intervention enhances intervention efficacy. Research has been mixed regarding the effect of including friends in alcohol prevention activities (Dishion et al., 1999; O’Leary et al. 2002; Tevyaw et al., 2007; Weiss et al., 2005), but research consistently documents that peer influences are important risk factors for excessive drinking (Borsari & Carey, 2001). Thus, further research is also needed to attempt to more effectively harness the potential for peer influence to reinforce healthy, rather than risky behavior related to alcohol consumption.

Additionally, all intervention conditions in the current study involved multiple components, including personalized feedback regarding alcohol use and consequences, perceived norms regarding alcohol use (in general and/or on the 21st birthday), and expected outcomes from drinking, as well as protective behavioral strategies designed to reduce risks of drinking and increase alternatives to drinking. It is not currently clear which components are necessary or sufficient for producing drinking reductions in the context of the 21st birthday. A thorough evaluation of those questions was beyond the scope of this evaluation. Based on previous research (Neighbors et al., 2009) we would suggest that intentions; 21st birthday perceived norms; ability to estimate own BAC and associated effects; and protective behaviors would be good candidates for systematic investigation in subsequent examinations.

Beyond individual interventions, adequately addressing 21st birthday drinking may require efforts to reshape public perceptions of 21st birthday drinking as a rite of passage, as well as work with the bar and hospitality industry to alter or eliminate 21st birthday drink promotions. A combination of individual, public health, and policy interventions may be necessary to reduce the risks associated with drinking on the 21st birthday. Indeed, the high correspondence between drinking intentions and behavior around this event, as evident in the present study, underscores the challenges of changing 21st birthday drinking and the need to consider multiple strategies beyond individually focused interventions. Broader approaches combining multiples strategies (e.g., knowledge change, environmental change, health protection, and intervention and treatment services) at multiple levels (i.e., individual, group, institution, community, state, and/or society) are most likely to have the largest impact (for further discussion and examples see Neighbors et al., 2007).

In sum, these results are promising for options on campuses to reduce both use and consequences associated with 21st birthday celebrations. Given the potentially tragic outcomes that have been associated with navigating this high-risk event, and the relatively mixed findings in prior interventions studies, it is notable that we have both in-person and web-based interventions that appear to be efficacious.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant R01AA016099.

Contributor Information

Clayton Neighbors, University of Houston.

Christine M. Lee, University of Washington

David C. Atkins, University of Washington

Melissa A. Lewis, University of Washington

Debra Kaysen, University of Washington.

Angela Mittmann, University of Washington.

Nicole Fossos, University of Washington.

Irene M. Geisner, University of Washington

Cheng Zheng, University of Washington.

Mary E. Larimer, University of Washington

References

- Armitage CJ, Conner M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2001;40:471–499. doi: 10.1348/014466601164939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins DC, Gallop RJ. Rethinking how family researchers model infrequent outcomes: A tutorial on count regression and zero-inflated models. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:726–735. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Carney MM. Biases in the perceptions of the consequences of alcohol-use among college-students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993;54:54–60. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Marlatt GA, Kivlahan DR, Fromme K, Larimer ME, Williams E. An experimental test of three methods of alcohol risk reduction with young adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:974–979. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.6.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Stacy A, Larimer M. Biases in the perception of drinking norms among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1991;52:580–586. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bewick BM, Trusler K, Mulhern B, Barkham M, Hill AJ. The feasibility and effectiveness of a web-based personalised feedback and social norms alcohol intervention in UK university students: A randomised control trial. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:1192–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Effects of a brief motivational intervention with college student drinkers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:728–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Peer influences on college drinking: A review of the research. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2001;13:391–424. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brister HA, Wetherill RR, Fromme K. Anticipated versus actual alcohol consumption during 21st birthday celebrations. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71:180–183. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Carey MP, DeMartini KS. Individual-level interventions to reduce college student drinking: A meta-analytic review. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2469–2494. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caudill BD, Marlatt GA. Modeling influences in social drinking: An experimental analogue. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1975;43:405–415. doi: 10.1037/h0076689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: the effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copello A, Orford J, Hodgson R, Tober G, Barrett C. Social behaviour and network therapy: Basic principles and early experiences. Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27:345–366. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00176-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca FK, Darkes J, Greenbaum PE, Goldman MS. Up close and personal: temporal variability in the drinking of individual college students during their first year. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:155–164. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. Brief alcohol screening and intervention for college students. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McCord J, Poulin F. When interventions harm - Peer groups and problem behavior. American Psychologist. 1999;54:755–764. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.9.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doumas DM, McKinley LL, Book P. Evaluation of two Web-based alcohol interventions for mandated college students. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest S, Strange V, Oakley A. A comparison of students’ evaluations of a peer-delivered sex education programme and teacher-led provision. Sex Education. 2002;2:195–214. [Google Scholar]

- Glassman TJ, Dodd VJ, Sheu J, Rienzo BA, Wagenaar AC. Extreme ritualistic alcohol consumption among college students on game day. Journal of American College Health. 2010;58:413–423. doi: 10.1080/07448480903540473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Marks G, Hansen WB. Social influence processes affecting adolescent substance use. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1991;76:291–298. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.76.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum PE, Del Boca FK, Darkes J, Wang CP, Goldman MS. Variation in the drinking trajectories of freshmen college students. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:229–238. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hembroff L, Atkin C, Martell D, McCue C, Greenamyer J. Evaluation results of 21st birthday card program targeting high-risk drinking. Journal of American College Health. 2007;56:325–333. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.3.325-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbe JM. Negative Binomial Regression. 2. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hurlbut SC, Sher KJ. Assessing alcohol problems in college students. Journal of American College Health. 1992;41:49–58. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1992.10392818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM. Social influences in motivated drinking among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:142–150. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.17.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koski-Jannes A, Cunningham J. Interest in different forms of self-help in a general population sample of drinkers. Addictive Behaviors. 2001;26:91–99. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00092-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kypri K, Saunders JB, Gallagher SJ. Acceptability of various brief intervention approaches for hazardous drinking among university students. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2003;38:626–628. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agg121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Migliuri S, Cail J. A night to remember: A harm-reduction birthday card intervention reduces high-risk drinking during 21st birthday celebrations. Journal of American College Health. 2009;57:659–662. doi: 10.3200/JACH.57.6.659-663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM. Identification, prevention, and treatment revisited: Individual-focused college drinking prevention strategies 1999–2006. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2439–2468. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Lee CM, Kilmer JR, Fabiano PM, Stark C, Geisner IM, et al. Personalized mailed feedback for college drinking prevention: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:285–293. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Turner AP, Anderson BK, Fader JS, Kilmer JR, Palmer RS, et al. Evaluating a brief alcohol intervention with fraternities. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:370–380. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Lindgren KP, Fossos N, Neighbors C, Oster-Aaland L. Examining the relationship between typical drinking behavior and 21st birthday drinking behavior among college students: Implications for event-specific prevention. Addiction. 2009;104:760–767. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02518.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C, Lee CM, Oster-Aaland L. 21st birthday celebratory drinking: Evaluation of a personalized normative feedback card intervention. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:176–185. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Patrick ME, Lee CM, Kaysen DL, Mittman A, Neighbors C. Use of protective behavioral strategies and their association to 21st birthday alcohol consumption and related negative consequences: A between- and within-person evaluation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. doi: 10.1037/a0023797. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Wirtz PW, Beattie MC, Noel N. Matching treatment focus to patient social investment and support: 18-month follow-up results. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:296–307. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.2.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Wirtz PW, Zweben A, Stout RL. Network support for drinking, Alcoholics Anonymous and long-term matching effects. Addiction. 1998;93:1313–1333. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.93913133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Dimeff LA, Larimer ME, Quigley LA, et al. Screening and brief intervention for high-risk college student drinkers: results from a 2-year follow-up assessment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:604–615. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrady BS. To have but one true friend: Implications for practice of research on alcohol use disorders and social network. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:113–121. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.2.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally AM, Palfai TP, Kahler CW. Motivational Interventions for Heavy Drinking College Students: Examining the Role of Discrepancy-Related Psychological Processes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:79–87. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Manuel JK, Hendrickson SM, Miller WR. Assessing competence in the use of motivational interviewing. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Benson TA, Vuchinich RE, Deskins MM, Eakin D, Flood AM, et al. A Comparison of Personalized Feedback for College Student Drinkers Delivered with and without a Motivational Interview. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:200–203. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Computing a BAC estimate. US Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Atkins DC, Lewis MA, Lee CM, Kaysen D, Mittmann A, et al. Event specific drinking among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011 doi: 10.1037/a0024051. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Jensen M, Tidwell J, Walter T, Fossos N, Lewis MA. Social norms interventions for light and non-drinking students. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations. 2011;14:651–669. doi: 10.1177/1368430210398014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Larimer ME, Lewis MA. Targeting misperceptions of descriptive drinking norms: efficacy of a computer-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:434–447. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N, Walter T. Internet-based personalized feedback to reduce 21st-birthday drinking: A randomized controlled trial of an event-specific prevention intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:51–63. doi: 10.1037/a0014386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lewis MA, Atkins DC, Jensen MM, Walter T, Fossos N, et al. Efficacy of web-based personalized normative feedback: A two-year randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:898–911. doi: 10.1037/a0020766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Oster-Aaland L, Bergstrom RL, Lewis MA. Event- and context-specific normative misperceptions and high-risk drinking: 21st birthday celebrations and football tailgating. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:282–289. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Spieker CJ, Oster-Aaland L, Lewis MA, Bergstrom RL. Celebration intoxication: An evaluation of 21st birthday alcohol consumption. Journal of American College Health. 2005;54:76–80. doi: 10.3200/JACH.54.2.76-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Walters ST, Lee CM, Vader AM, Vehige T, Szigethy T, et al. Event-specific prevention: Addressing college student drinking during known windows of risk. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2667–2680. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary TA, Brown SA, Colby SM, Cronce JM, D’Amico EJ, Fader JS, et al. Treating adolescents together or individually? Issues in adolescent substance abuse interventions. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2002;26:890–899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley BM, Collins RL. The modeling of alcohol consumption: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60:90–98. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Software] Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2010. http://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- Riper H, Kramer J, Smit F, Conijn B, Schippers G, Cuijpers P. Web-based self-help for problem drinkers: A pragmatic randomized trial. Addiction. 2008;103:218–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutledge PC, Park A, Sher KJ. 21st birthday drinking: Extremely extreme. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:511–516. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.3.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BH, Bogle KE, Talbott L, Gant R, Castillo H. A randomized study of four cards designed to prevent problems during college students’ 21st birthday celebrations. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:607–615. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tevyaw TO, Borsari B, Colby SM, Monti PM. Peer enhancement of a brief motivational intervention with mandated college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:114–119. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.1.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thombs DL, Olds RS, Ray-Tomasek J. Adolescent perceptions of college student drinking. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2001;25:492–501. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.25.5.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Neighbors C. Feedback interventions for college alcohol misuse: what, why and for whom? Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:1168–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Vader AM, Harris TR, Field CA, Jouriles EN. Dismantling motivational interviewing and feedback for college drinkers: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:64–73. doi: 10.1037/a0014472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss B, Caron A, Ball S, Tapp J, Johnson M, Weisz JR. Iatrogenic effects of group treatment for antisocial youths. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:1036–1044. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetherill RR, Fromme K. Subjective responses to alcohol prime event-specific alcohol consumption and predict blackouts and hangover. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:593–600. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood MD, Read JP, Palfai TP, Stevenson JF. Social influence processes and college student drinking: The mediational role of alcohol outcome expectations. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:32–43. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]