Abstract

Objective

This study tested the comparative effectiveness of Modified Behavioral Self-Control Therapy (MBSCT) and naltrexone (NTX), as well as the added benefit of combining the two, in problem drinking men who have sex with men (MSM) seeking to reduce, but not quit drinking. Method: Participants (N=200) were recruited and urn randomized to one of two medication conditions, NTX or placebo (PBO) and either MSBCT or no behavioral intervention, yielding four conditions: PBO, NTX, MSBCT, and NTX+MSBCT. In addition, all participants received a brief medication compliance intervention. Participants were treated for 12 weeks and assessed one week after treatment completion. Two primary outcomes - sum of standard drinks and number of heavy drinking days - and one secondary outcome - percentage of those drinking in a non-hazardous manner (NoH) - were selected a-priori. Results: There was a significant main effect for MBSCT (all ps < .01), but not NTX on all three outcomes. In addition, the combination of NTX and MBSCT was not more effective than either MSCBT or PBO. There was a significant interaction effect on NoH, such that NTX significantly increased the likelihood (OR = 3.3) of achieving a non-hazardous drinking outcome relative to PBO. In addition, NTX was significantly more effective than PBO on a descriptive outcome: negative consequences of drinking.

Conclusions

There was no advantage to adding NTX to MBSCT. In addition, MBSCT showed stronger evidence of efficacy than NTX. At the same time, NTX delivered in the context of a minimal medication compliance intervention was significantly more effective than PBO on an important clinical indicator. Results provide new information to guide the treatment of problem drinking, including in primary care settings.

Introduction

Alcohol Use Disorders (AUDs) are a prevalent and costly public health problem that disproportionately affect young adults (Grant et al., 2004). Over the last forty years, the federal government has made the development, testing, and dissemination of effective pharmacotherapies for AUD a major research priority (Warren & Hewitt, 2010). The development of pharmacotherapies for AUD is seen as important for several reasons. First, it is increasingly clear that AUD has a biological basis, and the development of medications that target relevant biological mechanisms should improve outcomes beyond what can be achieved by psychosocial treatments alone (Jupp & Lawrence, 2010). Second, AUD along with other addictive disorders are highly stigmatized. It is thought that the development of medications will lead to a reduction in stigma, greater integration of AUD treatment into mainstream healthcare, and, hence, greater access to care (Roman, Abraham, & Knudsen, 2011). Third, the development of AUD medications is seen as critical to expanding the continuum of care in the United States (Willenbring, 2010). The dominant AUD treatment option is intensive, 12-step oriented treatment delivered in the specialty healthcare sector (McLellan, Carise, & Kleber, 2003). This intensive model is appropriate to treat chronic and severe AUD, but studies indicate that the majority of those diagnosed with alcohol dependence have mild to moderate forms of the disorder and less than 10% of these individuals ever seek treatment (Moss, Chen, & Yi, 2007). AUD pharmacotherapies, when combined with brief behavioral interventions, appear to be an effective and potentially attractive option for those with mild to moderate alcohol dependence and could be delivered as part of primary medical care (Willenbring, 2007). Thus, research on combined AUD medication and brief behavioral interventions, especially research that targets those with less severe forms of AUD, has high clinical and public health significance.

Research on Naltrexone and Behavioral Treatments for AUD

Oral naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, has been demonstrated to be a safe, well tolerated, and effective in the treatment for AUD (Rösner et al., 2010). Although not every trial has found that naltrexone improves outcome over placebo, a large meta-analysis showed that daily treatment with oral naltrexone decreased the risk of relapse to heavy drinking by approximately 36% (Srisurapanont & Jarusuraisin, 2005). A number of studies have examined whether combining naltrexone with an effective behavioral intervention improves outcomes over each treatment alone. Generally, some form of cognitive behavioral treatment (CBT) for AUD has been tested with the hypothesis that naltrexone's effect on craving coupled with CBT training on cue recognition and coping with craving would have synergistic effects (Anton et al., 1999).

Early studies did find that naltrexone and CBT improved outcomes over each alone (Anton et al., 2005; Balldin et al., 2003; Heinälä et al., 2001; O'Malley et al., 1992). However, a large multi-site trial found no added benefit for CBT relative to naltrexone plus medication management (Anton et al., 2006). In addition, Oslin et al. (2008) found that CBT plus naltrexone was no better than CBT alone and that naltrexone was not superior to placebo. Thus, considerable uncertainty remains about the best way to combine naltrexone and behavioral treatments. Recent reviews suggest that naltrexone's effects may be more selective than previously thought and recommend more targeted studies where sample heterogeneity is reduced and greater methodological rigor is employed (Pettinati et al., 2006; Rosner, Leucht, Lehert, & Soyka, 2008).

Problem Drinkers Seeking to Reduce but not Quit Drinking

One promising avenue for further research on naltrexone's effects is its use to treat problem drinkers seeking to reduce, but not quit drinking. Problem drinkers are characterized by mild-to-moderate alcohol problem severity, low rates of comorbid disorders, a higher level of psychosocial functioning than those with severe alcohol dependence (AD), and a preference to seek moderation, rather than abstinence as a treatment goal (Hester, 1995). While a number of effective behavioral interventions exist to treat problem drinkers, these interventions tend to be less effective for those with higher levels of alcohol dependence (Moyer, Finney, Swearingen, & Vergun, 2002), raising the possibility that an anti-craving medication like naltrexone added to behavioral treatment might improve outcomes. Moreover, a number of lines of evidence converge to suggest that naltrexone may be more effective at reducing heavy drinking than establishing abstinence. Thus, naltrexone might be more effective for moderation than abstinence goal treatments. Specifically, preclinical and clinical studies support the hypothesis that naltrexone acts to blunt the rewarding properties of alcohol such that individuals experience less arousal and more sedation as they continue to drink (O'Malley & Froehlich, 2003). In addition, reviews indicate that naltrexone has larger effects when the outcome measured is a reduction in heavy drinking as opposed to the promotion of abstinence (Pettinati, et al., 2006).

Research on Naltrexone as a Treatment to Reduce Heavy Drinking

Only three placebo-controlled trials have tested the efficacy of naltrexone with the explicit aim of reducing drinking (Heinälä, et al., 2001; Karhuvaara et al., 2007; Kranzler et al., 2003; Kranzler et al., 2009). These three studies varied considerably with regard to sample characteristics, medication administration, and type of behavioral intervention. Heinala and colleagues (2001) attempted to replicate and extend findings from O'Malley and colleagues (2003). They compared naltrexone with placebo and CBT with supportive therapy using a factorial design in outpatients with AUD. In contrast to earlier studies, there was no requirement for abstinence prior to study entry and the first 12 weeks of treatment, during which time naltrexone was administered daily, was designed as an induction period to establish abstinence. After 12 weeks, the medication was administered in a targeted fashion (taken only when cravings were high). Supportive therapy focused on maintaining absolute abstinence and CBT allowed for some drinking. The study showed a significant interaction between naltrexone and CBT, such that the group that received both had significantly better outcomes . While the Heinala et al. study is the only one of the three studies that tested the combination of naltrexone and a behavioral intervention, it is difficult to generalize findings to problem drinkers since the study did not explicitly target moderated drinking as a treatment goal and used a behavioral intervention that focused on abstinence as a comparison to CBT.

Kranzler and colleagues (2003; 2009) explicitly focused on problem drinkers who sought to moderate their drinking. The aim of these studies was to compare the efficacy of daily versus targeted naltrexone. Participants were randomly assigned to receive naltrexone (50 mg) or placebo on a daily or targeted basis. All participants received bi-weekly CBT focused on teaching moderation drinking skills. Participants in the targeted condition were taught to anticipate high-risk situations and take naltrexone as a coping strategy to avoid heavy drinking. Findings were somewhat equivocal across studies. In the earlier study, daily naltrexone reduced drinking but only among men (Kranzler, et al., 2003). In the later study (Kranzler, et al., 2009), targeted naltrexone yielded significantly better outcomes for men on the primary outcome measure (mean drinks per day) as well as significantly better outcomes on a secondary outcome measure (drinks per drinking day) for all participants. In commenting on the findings, Kranzler and colleagues note the promise of naltrexone in the context of brief interventions for problem drinkers and suggest future studies should consider administration of a higher dose of naltrexone than 50 mg and the use of a minimal medication compliance condition, since administration of CBT across conditions have may obscured the effects of naltrexone.

Treatment Considerations for Problem Drinking MSM

In the United States, MSM have consistently represented the largest percentage of persons diagnosed with AIDS and continue to be the group comprising the largest proportion of new HIV infections (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010). Heavy drinking is a risk factor for HIV infection among MSM (Koblin et al., 2006). Although the relationship between heavy drinking, unsafe sex, and HIV infection is complex, studies show that heavy drinking among MSM is associated with a greater frequency of risky sex (Irwin, Morgenstern, Parsons, Wainberg, & Labouvie, 2006; Ostrow & Stall, 2008). Because of the connection between heavy drinking, illicit drug use, and risky sex, substance abuse treatment is seen as a primary HIV prevention strategy for MSM (Hong & Koblin, 2009; Shoptaw & Frosch, 2000). Prior research has focused on developing effective and acceptable interventions for problem drinking MSM as part of an HIV prevention strategy (Morgenstern et al., 2007; The EXPLORE Study Team, 2004; Velasquez et al., 2009). In these studies, the drinking intervention was brief (4 to 12 sessions) and focused on either a choice of drinking goals (abstinence or moderation) or moderation alone. It was thought that these features would increase the likelihood that MSM would engage in treatment (Morgenstern, et al., 2007).

The current study builds directly on the results of the study by Morgenstern and colleagues (2007). Morgenstern et al. (2007) found that a brief behavioral intervention was effective at reducing heavy drinking among HIV-negative MSM. However, a significant portion of the sample continued to drink at problematic levels, and those with higher alcohol dependence were less likely to reduce drinking to non-hazardous levels. Anecdotal reports suggested participants experienced high level of cravings that interfered with their ability to moderate drinking (Kuerbis, Morgenstern, & Hail, 2011). In addition, willingness to engage in treatment was limited, with some prospective participants indicating that they were not interested in receiving counseling (Morgenstern et al., 2007). This result raised the possibility that offering MSM an option of a medication intervention without psychosocial treatment might lead to higher rates of treatment engagement.

Summary and Study Aims

There is an urgent need to develop effective AUD treatment models that appeal to a broader population than those currently served in specialty care settings. The combination of medication and brief behavioral interventions offer an important option for expanding the AUD continuum of care, including the delivery of treatment in primary care medical settings (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2005; Willenbring, 2007, 2010). Naltrexone is a safe, well tolerated, and effective medication for AUD, but considerable uncertainty remains about the best way to combine naltrexone and brief behavioral interventions. Evidence suggests that naltrexone might be especially effective for moderation goal treatments, but more research is needed (Kranzler et al., 2009).

Because of the high prevalence of HIV and the link between heavy drinking and HIV risk, problem drinking MSM are a distinct subgroup at especially high risk for negative health consequences as a result of drinking. Prior studies have tested brief, moderation drinking goal interventions in an effort to expand the continuum of care for problem drinking MSM. Studies have shown these interventions are effective (Morgenstern et al. 2007; Velasquez et al., 2009), but adding naltrexone to behavioral interventions might improve their efficacy. In addition, demonstrating that naltrexone without a behavioral intervention is effective for individuals seeking to reduce their drinking would expand options available to treat AUD.

Based on these considerations, we tested the efficacy of 100 mg of daily naltrexone versus placebo in sexually active MSM with an AUD. We selected a dose of 100 mg based on the positive results for naltrexone in Project COMBINE (Anton et al.,2006). We used a factorial design that combined medication with either modified behavioral self-control training (MBSCT) or no behavioral intervention. All participants received a brief medication compliance therapy that was designed to resemble physician practice in a primary care setting. We hypothesized that naltrexone or MBSCT would be superior to placebo and that the combination of naltrexone and MBSCT would be superior to either the active medication or MBSCT alone.

Method

Participants

Potential participants responded to online and print advertisements that targeted MSM who wished to reduce their drinking and not quit altogether. Advertisements emphasized client choice and a moderation approach and avoided potentially stigmatizing labels. Participants were also recruited through direct engagement with community outreach teams at gay bars and events, advertisements on social networking internet sites, flyers posted in gay community centers, and print media advertisements.

To be eligible for this study, men had to: 1) be age 18 to 65; 2) have an average weekly consumption of at least 24 standard drinks per week over the preceding 90 days; 3) identify as being sexually active with other men; and 4) read English at an eighth grade level or higher. Participants were excluded if they: 1) had a lifetime diagnosis of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or other psychotic disorder; an untreated current major depressive disorder; or current physiological dependence on alcohol or other drugs (with the exception of nicotine or cannabis), as demonstrated by physical withdrawal symptoms or a history of withdrawal, such as previous delirium tremens or seizures; 2) started or changed psychotropic medication in the preceding 90 days; 3) were at risk for serious medication side effects from naltrexone, such as those taking contraindicated medications or with severe liver abnormalities; 4) reported regular use of opioids; or 5) were enrolled in concurrent drug- or alcohol-related treatment during the 12-week treatment phase of the study.

Sample Characteristics

Sample baseline demographics and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. The typical participant was approximately 40 years old, Caucasian, single, had attended at least some college, had a baseline weekly consumption of 43.1 standard drinks (SD=25.5), and drank a little over 8 drinks per drinking day. Of the entire sample, 93% met criteria for DSM-IV alcohol dependence, and 73% were in the contemplation stage of change (Heather & Rollnick, 2000). Self-reported HIV status for the sample was as follows: 15% were HIV positive; 79% were HIV negative; and 6% did not know their HIV status.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Condition | NTX & MBSCT (n = 51) | NTX (n = 51) | MBSCT (n = 50) | PBO (n = 48) | Overall Sample (N = 200) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M or % | SD | M or % | SD | M or % | SD | M or % | SD | M or % | SD |

| Demographics | ||||||||||

| Age | 38.4 | (10.2) | 38.5 | (11.3) | 42.2 | (10.8) | 42.4 | (11.4) | 40.3 | (11.1) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||

| White | 73 | 78 | 59 | 85 | 74 | |||||

| African-American | 8 | 0 | 26 | 4 | 10 | |||||

| Asian | 4 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 3 | |||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 16 | 18 | 12 | 8 | 13 | |||||

| Education | ||||||||||

| High School/GED or less | 0 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 6 | |||||

| Some college/Associates | 16 | 22 | 19 | 13 | 17 | |||||

| Bachelor's degree | 41 | 28 | 14 | 25 | 27 | |||||

| Some/Grad/Prof | 43 | 42 | 61 | 54 | 50 | |||||

| Employed (n = 187) | ||||||||||

| Employed | 70 | 86 | 74 | 72 | 76 | |||||

| Unemployed/looking work | 13 | 8 | 8 | 12 | 10 | |||||

| Not in labor force/not look | 17 | 6 | 18 | 16 | 14 | |||||

| Drinking Severity | ||||||||||

| Mean sum std. drinks/week | 37.8 | (15.0) | 39.7 | (19.8) | 47.8 | (35.2) | 47.2 | (26.4) | 43.1 | (25.4) |

| Mean drinks per drinking day | 7.8 | (3.0) | 7.8 | (3.3) | 8.7 | (5.1) | 9.0 | (6.1) | 8.3 | (4.5) |

| Mean number of heavy drinking days/week | 3.1 | (1.9) | 3.2 | (1.9) | 3.7 | (2.0) | 3.7 | (2.3) | 3.4 | (2.0) |

| Short Inventory of Problems score | 16.5 | (7.6) | 17.6 | (8.0) | 14.6 | (7.2) | 16.1 | (7.3) | 16.2 | (7.6) |

| Alcohol Dependence Scale score | 14.4 | (5.6) | 13.7 | (4.8) | 12.7 | (5.5) | 14.3 | (5.8) | 13.8 | (5.4) |

| Number of alcohol dependence criteria met | 5.2 | (1.5) | 5.0 | (1.5) | 5.1 | (1.4) | 4.7 | (1.9) | 5.0 | (1.6) |

| Any drug usea | 77 | 77 | 52 | 63 | 67 | |||||

| Ever received formal treatment for substance use problem | 11 | 19 | 14 | 13 | 14 | |||||

| Beck Depression Inventory-II Score | 19.6 | (9.5) | 19.3 | (8.8) | 17.3 | (7.8) | 18.1 | (8.5) | 18.6 | (8.6) |

| State STAI Scoreb | 40.8 | (12.0) | 41.2 | (11.0) | 39.2 | (9.8) | 38.9 | (11.3) | 40.0 | (11.0) |

Note: NTX + MBSCT = naltrexone and Modified Behavioral Self Control Therapy; NTX = naltrexone alone; MBSCT = Modified Behavioral Self Control Therapy alone; PBO = placebo.

χ2(3, N = 200) = 9.67, p = .02.

STAI=State-Trait Spielberger Anxiety Inventory

Procedures

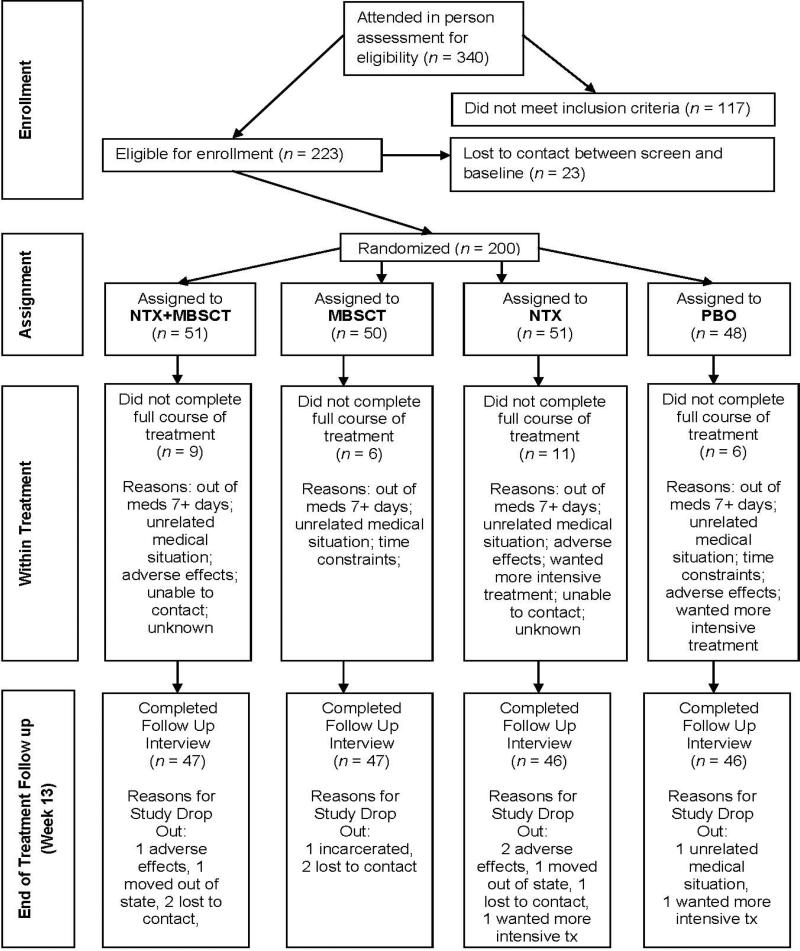

Procedures were in compliance with and approved by the institutional review board at New York State Psychiatric Institute. Potential participants interested in the study called to participate in a brief telephone interview to receive information about study procedures. Callers were asked to provide verbal consent and screened for initial study eligibility. Eligible participants were then scheduled for an in-person interview during which they provided informed consent. Three hundred forty individuals were screened in person. Participants (N=223) who met full eligibility criteria were assessed. Following the screening visit, but prior to randomization, 23 participants were lost to contact. The final sample consisted of 200 participants who were assigned via urn randomization to one of two medication conditions, naltrexone or placebo. All participants received an adjusted version of the Brief Behavioral Compliance Enhancement Treatment (BBCET, Johnson, DiClemente, Ait-Daoud, & Stoks, 2003), a brief intervention that represents usual care for managing medication compliance. Additionally, participants were randomly assigned to receive Modified Behavioral Self-Control Therapy (MBSCT) or no behavioral intervention.

The treatment phase lasted 12 weeks, with a follow-up assessment at one week thereafter (also known as end of treatment). After completing the end-of-treatment assessment, participants were given a sealed envelope revealing their medication condition, so that they could use the information if they wished to obtain treatment in the community. Staff remained blind to participants’ medication condition throughout the study. (See Figure 1 for detailed flow of study procedures).

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through the study.

Interventions

Usual care

Brief Behavioral Compliance Enhancement Treatment (BBCET) is an intervention designed to enhance medication compliance among participants, reinforcing the benefits of the medication for reduction in drinking, and discussing the management of any adverse effects (Johnson, et al., 2003). Within BBCET, physicians also reviewed with participants other drug use, current mental status, and encouraged clients to set reasonable drink reduction goals. BBCET was developed as a minimal physician intervention that would not include elements thought to be the active ingredients of effective AUD behavioral therapies. Thus, therapist interventions involving addressing ambivalence, increasing motivation to reduce drinking, or skills training were proscribed. Although designed for pharmacotherapy trials, the tasks involved can be easily adapted to a primary care setting.

All participants, regardless of condition, received BBCET, a series of 20-minute sessions with a psychiatrist weekly for the first three weeks, and then every other week thereafter.. All BBCET sessions were audio-recorded for fidelity purposes. Two independent coders assessed the extent to which each of the five psychiatrists that implemented BBCET during the study covered the assigned discussion points regarding the time period since the participant's last visit. To differentiate between the MBSCT and BBCET sessions, each coder assessed whether the psychiatrist used specific Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT) skills (e.g., challenging irrational thoughts, conducting a functional analysis of drinking behavior) during the session. A total of 30 audio tapes of BBCET sessions were randomly selected and rated across the domains by the coders. Overall, 100% of the sessions demonstrated adherence to the BBCET protocol. In addition, there were no MBSCT or other CBT skills utilized by the treating psychiatrist during any of the randomly selected sessions. Participants attended a mean of 7.7 (SD=.55) BBCET sessions out of eight possible. For ease of presentation we refer to BBCET as Usual Care throughout the manuscript.

Medication (naltrexone or placebo)

Medication assignment was double blind, and psychiatrists administering BBCET were blind to participants’ therapy and medication conditions. Medication tablets were encapsulated to accommodate placebo and facilitate medication blinding. The dosage of medication was initiated at 25 mg/day, increased to 100 mg/day of naltrexone or the placebo equivalent during the first three weeks of treatment, and remained at this level through the remainder of the treatment phase. Adherence to medication was assessed and recorded by study psychiatrists at each BBCET visit. Physicians inquired about participants’ daily doses, number of capsules taken, and number of days and doses missed. Participants were considered medication adherent if, based on capsule counts, they took at least 80% of the medication during the 12-week treatment period.

MBSCT

Based on existing behavioral self control therapy (Sanchez-Craig, Annis, Bornet, & MacDonald, 1984), MBSCT is a manual-based amalgam of Motivational Interviewing (MI) and CBT for moderation of drinking specifically designed for problem drinking MSM focused on reduction of alcohol consumption (Morgenstern et al., 2007). Both MI (Hettema, Steele, & Miller, 2005; Morgenstern et al., 2007) and CBT (Morgenstern & McKay, 2007) have received significant empirical support in the treatment of problem drinking. In the current study, treatment was comprised of 12 one-hour sessions that focused on moderation. The first two sessions of counseling consisted of MI, and the last 10 sessions focused on the development of skills to modify behavior patterns of excessive drinking. The first session of CBT involved completion of an individualized functional analysis that guided which skills training sessions would be covered and addressed proximal factors for at-risk drinking. Each skills session was structured to include a skills rationale, skills didactic training, an in-session performance exercise, and corresponding homework. In addition to assigned practice exercises, all clients completed daily self-monitoring cards of drinking. Self-monitoring cards, client goals for drinking and homework were reviewed at the beginning of each subsequent session. A total of 10 master's- and doctoral-level therapists delivered this intervention. All therapists had extensive training in implementing both MI and CBT and attended weekly supervision with the first author of the study. All but one therapist had more than five years of experience implementing these interventions prior to the study.

Fidelity to the therapy was monitored in two ways. The first was through weekly supervision, in which all therapists watched videos of sessions and discussed fidelity and technique. Second, the Yale Adherence Competence Scale (YACS, Carroll et al., 2000; Madson & Campbell, 2006), which has demonstrated strong psychometrics, was used to evaluate therapist's skill level and frequency of utilization of skills for both MI and CBT. Because the protocol was flexible, it was not expected that every skill session would be covered with each client or that every skill would be utilized in a session. Two independent raters trained in the YACS coded 10% of the videotaped psychotherapy sessions. These tapes were randomly selected across all therapists, across different points in the therapy (e.g., different session numbers), and across 30 different clients. Because sessions were individually tailored, therapists were considered adherent if they completed at least two of the a priori defined components to the therapy according to the YACS coding. Interrater agreement was 80.2%, with therapists demonstrating a high level of adherence and skill for both MI and CBT components as demonstrated by a mean rating of 6.43 (SD=.27) out of a possible 7. This score indicates that therapists delivered the prescribed interventions with a high level of consistency and skill, suggesting a high level of protocol adherence.

Study discontinuation and attrition

Participants in the treatment groups were discontinued or dropped out of treatment and/or the study for similar reasons. Below is a description of those who discontinued treatment or were unavailable for an end-of-treatment follow-up assessment.

Discontinuation from treatment

A total of 16% of participants discontinued treatment. Eight participants were non-adherent to a therapeutic dose of naltrexone or placebo (at least 50 mg or two capsules) for seven days or more and were removed from the treatment phase of the trial by the treatment team; six participants experienced unrelated medical problems that required un-blinding and discontinuation of the medication. For each of these reasons for discontinuation, there were no significant differences across conditions. Seven participants withdrew from treatment due to time constraints or for unknown reasons. Additionally, five participants withdrew from treatment due to uncomfortable adverse effects. Although there were slightly more individuals in the naltrexone condition that discontinued treatment due to adverse effects, this difference was not statistically significant. One participant chose to pursue alternative treatment. Finally, there were five individuals who could not be reached by investigators despite substantial outreach. Of all of the participants who discontinued or withdrew from treatment, only five did not provide data for the planned drinking outcome analyses.

Unavailable for follow up

Seven percent of participants were unavailable for follow up on the Timeline Followback interview. Two expressed a desire to pursue more intensive treatment, two moved out of the tri-state area, and one participant was incarcerated. Four participants chose to withdraw from the study altogether: three from adverse effects of medication and one due to an unrelated medical condition. We were unable to contact five participants despite several outreach attempts. Reasons for withdrawal or drop out were evenly distributed across condition. There were no significant group differences. See Figure 1. The study also reports on descriptive clinical outcomes at the end of treatment based on self-report questionnaire data. Questionnaire data were available for participants who attended an in-person interview within a limited time window at the end of treatment. Among those from whom we collected drinking outcomes data, 92.5% had complete questionnaire data.

Measures

Sociodemographics

A self-report, demographic questionnaire used in a series of completed studies was used during the initial phone and in-person encounter with the participant. This covered age, race/ethnicity, education, employment, psychiatric and substance abuse history, treatment history, and HIV status.

Substance use and other psychiatric disorders

The Composite International Diagnostic Instrument, Substance Abuse Module (CIDI-SAM, Cottler, Robins, & Helzer, 1989) was used to evaluate substance dependence exclusion criteria. It is a well established diagnostic interview that has demonstrated excellent reliability for individual symptoms of substance abuse and dependence (Cottler, et al., 1989). Participants were screened for psychosis or bipolar disorder using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, psychotic screening and bipolar disorder sections (SCID, First, Spitzer, & Gibbon, 1996) and for cognitive impairment using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE, Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975). Depressive symptoms were measured using the Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition (BDI-II, Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996). Symptoms of anxiety were measured using the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI, Spielberger, 1983). The state subscale was used for these analyses.

Alcohol and drug use patterns and problems

The widely implemented Form 90 (Miller & Del Boca, 1994) was used to evaluate lifetime and recent (past 90 days) drug use severity. The Form 90 has demonstrated strong reliability and validity (Tonigan, Miller, & Brown, 1997). The Short Inventory of Problems (SIP, Miller, Tonigan, & Longabaugh, 1995) is a 15-item self-report measure of lifetime or past three months’ negative consequences of drinking. The SIP has demonstrated strong psychometric properties (Kenna et al., 2005) and for this sample yielded strong reliability at all time points (alpha=.87 across all time points). The Readiness to Change Questionnaire (RCQ, Heather & Rollnick, 2000) is a 12-item instrument used to determine participants’ current stage of change for reducing/quitting drinking: precontemplation, contemplation, or action. It has demonstrated good psychometric properties and predictive validity. The Time-Line Follow-Back Interview (TLFB, Sobell et al., 1980) assessed frequency of alcohol use during the previous 90 days at prescreen and at the end of treatment. Drinking was assessed using the TLFB for the period between the prescreen and baseline interviews (typically 1-to-2 weeks). The TLFB has demonstrated good test-retest reliability (Carey, Carey, Maisto, & Henson, 2004), agreement with collateral reports of alcohol (Dillon, Turner, Robbins, & Szapocznik, 2005), convergent validity, and reliability across mode of administration (i.e., in person or over the phone, Vinson, Reidinger, & Wilcosky, 2003).

Analytic Plan

Two primary outcomes--weekly sum of standard drinks (SSD), and weekly number of heavy drinking days (HDD)--were selected a priori because NIAAA safe drinking guidelines include measures of drinking quantity (no more than 14 drinks per week for men) and intensity (no heavy drinking days). In addition, a secondary outcome measure, the percent of subjects who achieved non-hazardous drinking (NoH) in the prior week (defined as drinking 14 or fewer standard drinks per week and having no heavy drinking days) was selected as a dichotomous measure. We selected this dichotomous measure because it lends itself tmore readily to clinical interpretation than continuous measures. Similar types of dichotomous measures are now required by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the approval of new drug applications to treat AD (Falk et al., 2010).

Generalized estimating equations (GEE, Liang & Zeger, 1986) were used to analyze the non-normal, longitudinal data for the three dependent variables (DVs): SSD, HDD and NoH. GEE is a data analytic technique for longitudinal data that corrects for correlated observations (Stokes, Davis, & Koch, 2000). Only the 186 individuals providing at least some alcohol use data after randomization were included in the models. Among those 186 participants with some data, missing data were extremely rare as valid data were available for 2225 out of 2232 possible observations (N=186 and 12 weeks), thus, missing data were not imputed. All available data were used in the analyses.

The independent variables (IVs) for the models were medication condition (naltrexone or placebo) and therapy condition (MBSCT or no behavioral intervention) and the interaction of these conditions. To allow simultaneous testing of both main and interaction effects, the IVs were orthogonally contrast-coded. Time (weeks 1-12) and the interactions of time x medication condition, time x therapy condition, and time x medication x therapy were included in the models to test effects over time. The time variable was centered.

Several covariates were included in the models: the respective value of the DV (i.e., SSD, HDD) at prescreen and the week prior to baseline assessment. Age, baseline BDI-II scores, and the baseline maximum number of days of any drug use (except nicotine) were considered as potential covariates of drinking outcomes. However, they were unrelated to outcome and therefore not included.

Within each of the GEE analyses, a negative binomial distribution with log link functions for SSD and HDD, and a binomial distribution with logit link function for NoH, were specified and provided good model fit. An exchangeable working correlation matrix was specified (Stokes, et al., 2000). To further explore the findings of the primary analyses, post hoc analyses were performed.

To aid in the clinical interpretation of findings, descriptive outcomes of the three alcohol consumption variables described above were also calculated for the final month in treatment (weeks 9-12). The estimated marginal means of these variables were computed, controlling for baseline values, and can thus be compared to the baseline values to more fully evaluate the extent of drink reduction. We did not test condition differences in these analyses, as that would be redundant with prior tests. In addition, we report on three additional clinically-relevant self-reported outcomes: level of depression, level of anxiety, and negative consequences of drinking during the entire treatment period. We tested for condition differences using regression analysis with similar IVs as described above.

We had no a priori hypotheses regarding condition differences on the psychological outcomes, as the treatment did not focus on mental health symptoms. Although over time one would expect a similar pattern of condition differences to emerge for negative consequences as the other drinking outcome measures, our assessment methods to detect these differences had limitations. For example, the SIP questionnaire assessed negative consequences occurring over the entire treatment period, and thus would be less sensitive to detect effects that might emerge towards the end of treatment than weekly alcohol consumption data drawn from the TLFB. We discuss this and other limitations in interpreting the negative consequences outcome results in the Discussion Section. All analyses were conducted using the SAS software, Version 9.2 of the SAS system for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., 2002-2008).

Results

Group Equivalency

The only significant difference among the randomization conditions was on baseline drug use (χ2(3, N = 200) = 9.67, p = .02) as noted in Table 1.

Medication Adherence, Adverse Effects, and Medication Attributions

Ninety-five percent of participants received the full dosage of medication. Just under 90% (89.2%) of participants were adherent to the medication regimen.

More than half (62.0%) of participants reported experiencing some adverse effects, the most common of which were nausea, insomnia, diarrhea, fatigue, and loss of libido, and most dissipated once participants began treatment with the 100-mg dosage. There were no group differences on the frequency of adverse effects by medication group, with the exception of one week during the treatment phase. During week two, 55% of those on naltrexone reported experiencing adverse effects, as compared to only 37% of those on placebo (t(184)=-2.52, p < .02). Those with severe or intolerable adverse effects were titrated down to a lower dosage or ceased taking medication altogether under physician supervision. Among these cases, fatigue was the most commonly reported adverse effect.

At the end-of-treatment assessment, participants were asked to guess their medication condition, and 61.8% of all participants guessed the correct medication condition. Those in the placebo condition were more likely to guess their assigned medication condition correctly (χ2(1, N = 165) = 8.93, p = .03).

GEE Models of Drinking Outcomes

For the SSD model, GEE analysis revealed a significant main effect for time [B = -0.02, SE = 0.00, p < .0001 (IRR = 0.98, CI 95% = 0.98, 0.99)], indicating a linear decrease in drinking over the 12 weeks of treatment. The analysis also yielded a significant parameter estimate for therapy condition [B = -0.32, SE = 0.08, p < .0001 (IRR = 0.72, CI 95% = 0.62, 0.85)] when controlling for prescreen and baseline drinking, such that MBSCT was associated with a 28% lower expected count of drinks consumed per week over the 12-week treatment period than usual care alone. There was not a significant main effect for naltrexone [B = -0.09, SE = 0.08, p > .10 (IRR = 0.91, CI 95% = 0.78, 1.07)].

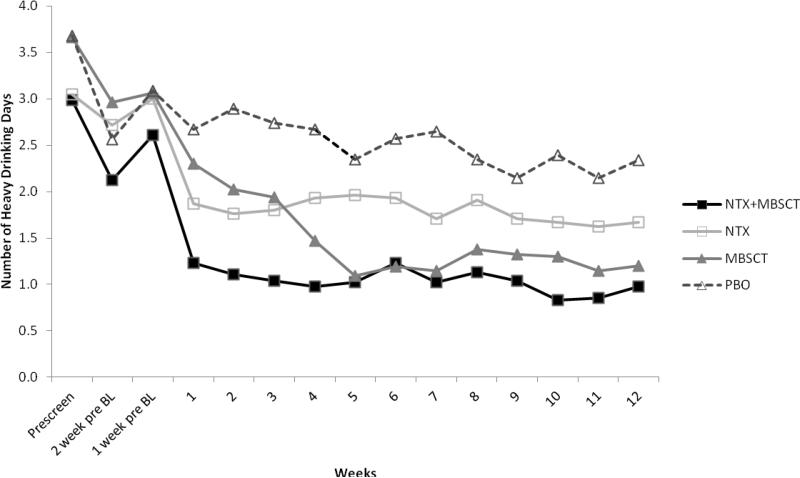

GEE analysis also yielded a significant effect for time [B = -0.03, SE = 0.01, p < .001 (IRR = 0.97, CI 95% = 0.96, 0.99)] in relation to HDD, again indicating a linear decrease in the number of heavy drinking days over time. A significant parameter estimate for therapy condition [B = -0.42, SE = 0.13, p < .01 (IRR = 0.66, CI 95% = 0.51, 0.85)] showed that MBSCT was associated with a 35% lower expected count of heavy drinking days per week over the 12-week treatment period than usual care alone. There was not a significant main effect for naltrexone [B = -0.17, SE = 0.14, p > .10 (IRR = 0.85, CI 95% = 0.65, 1.11)]. See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Number of heavy drinking days by condition pre-screen visit to end of treatment.

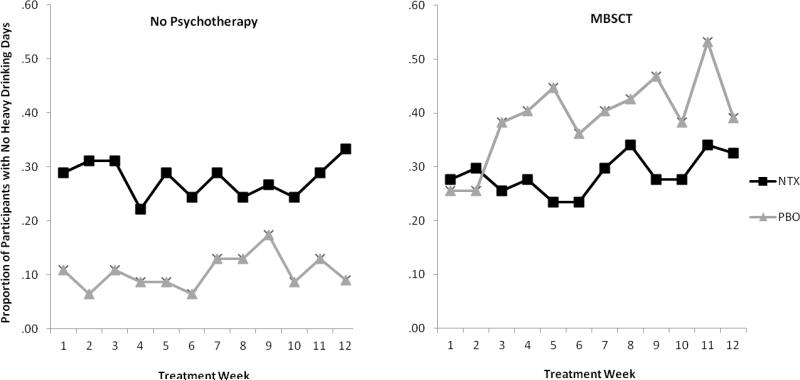

In regards to NoH, a significant main effect for time [B = 0.033, SE = 0.016, p < .05, (OR = 1.033, CI 95% = 1.00, 1.065)] indicated that the odds of drinking less than or equal to 14 standard drinks and having no heavy drinking days in a week increased 3% with each additional week of treatment. A significant main effect also was found for therapy condition [B = 0.82, SE = 0.26, p < .01 (OR = 2.27, CI 95% = 1.35, 3.81)] indicating that the odds of drinking less than or equal to 14 standard drinks with no heavy drinking days per week were more than two times greater for MBSCT compared to usual care alone during treatment. In addition, a significant interaction effect for therapy x medication condition was obtained (B = -1.81, SE = 0.54, p < .001). Follow-up analyses indicated that among those receiving usual care only, those received naltrexone were significantly more likely to have NoH over the course of the treatment period than those who received placebo (OR = 3.33, CI 95% = 2.14, 17.42). For those receiving MBSCT, naltrexone had no significant effect (OR = 0.53, CI 95% = 0.26, 1.07). Figure 3 illustrates this interaction.

Figure 3.

Interaction of medication and condition on no heavy drinking days. The graph on the left shows participants who received no psychotherapy, and the graph on right shows participants who were assigned to Modified Behavioral Self Control Therapy.

Descriptive Clinical Outcomes

The top part of Table 2 presents the estimated marginal means and the standard error values of the drinking outcomes described above for the last month in treatment controlling for the baseline values. There are clinically significant reductions in SSD and HDD from baseline across all conditions. These reductions are greater in the MBSCT condition. For example, in MSBCT the average number of standard drinks per week is reduced from baseline by more than half and the mean of 17.8 is not far above the NIAAA-recommended weekly consumption of 14 standard drinks for men (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2005). A somewhat different pattern of results obtains for NoH. Based on eligibility criteria, all participants drank heavily at least one day during the baseline period. A relatively small percentage of those in the placebo condition, 13%, were able to eliminate heavy drinking completely by the end of treatment. By contrast, the rates of this important clinical indicator more than doubled in the other conditions relative to placebo.

Table 2.

Descriptive Outcomes at End Treatment

| NTX+MBSCT (n = 47) | NTX (n = 46) | MBSCT (n = 47) | PBO (n = 46) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M | SE | M | SE | M | SE | M | SE |

| Primary Drinking Outcomesa | ||||||||

| Mean drinks per week | 17.9 | (2.2) | 24.8 | (2.2) | 17.8 | (2.2) | 28.9 | (2.2) |

| Heavy drinking days per week | .84 | (.26) | 1.6 | (.26) | 1.2 | (.26) | 2.3 | (.26) |

| % No heavy drinking last month | 28 | (.46) | 30 | (.47) | 34 | (.48) | 13 | (.34) |

| Other Outcomesb | (n = 44) | (n = 39) | (n = 44) | (n = 45) | ||||

| BDI II Scorec | 13.1 | (.84) | 13.1 | (.89) | 13.9 | (.84) | 14.0 | (.83) |

| State STAI Scored | 38.8 | (1.4) | 39.4 | (1.4) | 37.3 | (1.4) | 39.7 | (1.3) |

| SIP Scoree | 9.1 | (8.9) | 9.7 | (5.8) | 9.2 | (6.2) | 12.0 | 7.8 |

Note: NTX + MBSCT = naltrexone and Modified Behavioral Self Control Therapy; NTX = naltrexone alone; MBSCT = Modified Behavioral Self Control Therapy alone; PBO = placebo.

Primary drinking outcomes are based on weekly means for the last month of treatment. Data was collected at the week 13 assessment.

All psychological measure outcomes reported here are estimated means controlling for baseline scores.

BDI=Beck's Depression Inventory II

STAI=State-Trait Spielberger Anxiety Inventory

SIP=Short Inventory of Problems

The bottom half of Table 2 presents outcomes from questionnaire data. There was a statistically significant reduction in depression but not anxiety scores from baseline to the end of treatment. There were no significant main or interaction effects by condition (all ps > .27). Negative consequences (SIP score) demonstrated a statistically significant reduction across conditions (t(172) = 11.55, p < .001). Regression analysis of negative consequences from the SIP yielded a significant effect for a greater reduction in naltrexone relative to placebo (t(172) = -2.3, p < .03) Although the findings were in the expected direction for MSBCT relative to usual care, the effect did not reach significance (t(172)= -1.1, p < .27). There was no significant condition interaction (p > .35). Because there were more participants with missing SIP than TLFB outcome data (n = 14), and ten of those participants were in the naltrexone condition, we imputed missing values for those 14 participants using the baseline value of their SIP score and reran the analyses. This analysis yielded a weaker effect for naltrexone relative to placebo, with the effect findings at a trend level (t(172) = -1.7, p < .09). Results did not differ for MSCBT.

Discussion

This study is the first to rigorously test the efficacy of naltrexone, a behavioral therapy, or the combination, in a sample of individuals with AUD explicitly seeking to reduce but not quit drinking. The study sample reported high rates of DSM-IV alcohol dependence (93%), low rates of other co-occurring disorders, and high rates of being in earlier readiness to change: 75% reported being in the contemplation phase. Thus, this sample has a similar profile to that identified by Moss and colleagues (2007) of problem drinkers who might best be treated in primary care.

Contrary to the hypothesis, the combination of naltrexone and MBSCT did not improve outcomes relative to MBSCT alone. MBSCT delivered concurrently with medication compliance therapy was significantly more effective than compliance therapy alone on all outcome indicators. As illustrated in Figure 2, participants in MBSCT, regardless of medication condition reduced the number of heavy drinking days from about 3.5 days per week prior to treatment to about 1 day per week at the end of the treatment period. Overall, the incidence rates of heavy drinking days per week was 35% lower in those receiving MBSCT compared to compliance therapy alone.

Naltrexone did not significantly reduce drinking more than placebo, although findings were in the expected direction. However, there was a significant interaction effect in the analysis of the percentage of participants who achieved non-hazardous drinking. Among those receiving only medication compliance therapy, participants receiving naltrexone were significantly more likely than those receiving placebo to achieve non-hazardous drinking. Figure 3 illustrates that, by the end of treatment, about 32% of participants receiving naltrexone were drinking nonhazardously compared to about 9% of those receiving placebo.

The descriptive clinical outcomes showed a reduction in depression across all groups, but no differences based on condition. In addition, there was a significant reduction in negative consequences as a result of drinking in all conditions. Naltrexone yielded a significantly greater reduction than placebo, but there was no significant difference between MSCBT and the no behavioral treatment condition. These findings need to be interpreted in light of some design limitations. Findings that naltrexone yielded a significantly greater reduction in negative consequences relative to placebo are consistent with its effects on the non-hazardous drinking outcome and strengthen the evidence that naltrexone is effective in reducing recognized clinical markers of problem drinking. However, once the missing data were imputed (conservatively) the results were no longer statistically significant at the p<.05 level. The absence of significant effects for MSBCT is not consistent with those of the other drinking outcomes. One likely explanation is that MSCBT may have differentially increased awareness of negative consequences relative to not receiving behavioral treatment. A critical activity in MSBCT was helping clients become aware of the negative effects of their heavy drinking during the treatment. Indeed, this was a prescribed therapy activity in each session. By contrast, this therapy activity was proscribed in the medication compliance condition. Although participants across MSCBT and no behavioral treatment reported significantly reduced negative consequences, this confound may have obscured a significant difference between the conditions on this outcome. Another possible explanation is that changes in the occurrence of alcohol-related problems may take time to appear after changes in heavy drinking have occurred. Figure 2 shows that the drop in frequency of heavy drinking occurred earliest in the naltrexone groups and may have translated into changes in related problems before the end of the study period. In contrast, reduced problems attributable to MSCBT-induced reductions in heavy drinking may not have appeared until after the end of treatment and thus were not detected.

Results in Context

Several earlier studies showed greater efficacy for the combination of naltrexone and CBT (Anton, et al., 1999; Balldin, et al., 2003; Heinälä, et al., 2001) than either treatment alone, but later studies failed to replicate those findings (Anton, et al., 2006; Oslin, et al., 2008). We hypothesized that the efficacy of the combination of naltrexone and CBT would be more evident in an AUD sample seeking to reduce drinking and where treatment conditions were designed to provide a strong contrast of active ingredients: 100 mg of naltrexone versus placebo and MBSCT versus minimal medication compliance intervention. Results clearly indicate that combining NTX with MSCBT did not improve outcomes over MBSCT alone. Very few studies have evaluated naltrexone in the absence of a formal psychosocial intervention (e.g., CBT, Medication Management, BRENDA). Two studies found evidence to support the efficacy of naltrexone in the absence of a formal psychosocial intervention (Latt, Jurd, Houseman, & Wutzke, 2002; O'Malley & Froehlich, 2003), and one (Oslin, et al., 2008) did not. The current study is the first to examine this issue in an AUD sample seeking to reduce but not quit drinking.

Implications for Clinical Practice and Future Research

This study has a number of strengths in informing the development of models to treat AUD in primary care. The sample was similar in problem profile and stage of readiness to change that epidemiological studies have identified as an AUD population that could benefit from treatment delivered in primary care. The interventions tested represent relevant state-of-the-art treatment options that are feasible to implement in primary care. MBSCT yielded consistent and clinically significant reduction across planned outcome tests. Naltrexone was significantly more effective when compared to placebo in the absence of MBSCT on only one of three planned outcome tests: percent of participants drinking at non-hazardous levels. While this result may be due to Type I error, the magnitude of the difference (OR = 3.3), a similar result for negative consequences, and the clinical utility of a dichotomous outcome measure indicating a return to non-hazardous drinking is noteworthy.

The COMBINE study (Anton, et al., 2006) found that naltrexone along with medication management was as effective as a robust behavioral intervention. The clinical implication of this finding was that naltrexone and medication management should be the evidence-based option for delivery of AUD treatment in primary care because the staffing patterns (physicians, nurse) and modality of treatment (medication, nurse visits) are consistent with a primary care model. Findings from the current study suggest that for those seeking moderation, MBSCT has stronger evidence for efficacy than naltrexone.

Major changes in healthcare are serving as a catalyst for greater integration of behavioral health treatment into primary care settings (Buck, 2011) and the current finding should help inform that effort. Given its public health importance, treatment of problem drinkers remains an understudied area. It is noteworthy that traditional research designs to test medications and behavioral interventions have not shown the expected effects that the combination improves efficacy. Future research should consider the use of adaptive designs and include the study of client preferences (e.g., McKay, 2009) as many clients appear to have strong preferences for different types of treatments. For example, our findings suggest that naltrexone might be the favored treatment option for those problem drinkers who prefer medication to psychotherapy, but research is needed to test this hypothesis.

Study Limitations

Limitations on the internal validity of the study include the use of self-report for assessing medication compliance and drinking. Reviews indicate that the addition of biological measures does not add substantially to self-reported alcohol treatment outcomes (Babor, Steinberg, Anton, & Del Boca, 2000). In addition, we excluded participants with legal involvement and all participants were encouraged to select their own goals for drinking. Thus, some of the characteristics that might diminish the accuracy of self-report in many alcohol treatment studies were absent here. In addition, clients in the placebo condition were more likely to guess their medication assignment correctly. Thus, it might be that expectancies played a role in the differences observed between naltrexone and placebo. Potential limits to external validity include the presence of research assessments that could themselves influence drinking; recruitment and treatment of patients in non-primary-care academic settings, the ability to generalize from MSM to a broader population of men; and the absence of a post-treatment follow-up. However, prior treatment studies of MSM with AUD have found that drink reductions tend to remain stable over the year following behavioral treatment (Morgenstern, et al., 2007; Velasquez, et al., 2009). Although the ability to generalize results about MSCBT is limited by the fact that it was only administered in combination with a study medication, Motivational Interviewing and MBSCT have been demonstrated to be effective in reducing drinking in MSM with AUD (Morgenstern, et al., 2007; Velasquez, et al., 2009). In addition, because of the demographic features of the sample, findings may not generalize to younger, non-white, unemployed, and less educated groups of MSM.

Conclusions

This study tested the comparative effectiveness of a behavioral intervention (MBSCT) and a medication (naltrexone), as well as the added benefit of combining the two, in MSM with AUD seeking to reduce, but not quit drinking. MBSCT demonstrated statistically and clinically significant reductions in drinking across all planned tests. The combination of naltrexone with MBSCT was not more effective than MSCBT and placebo. Naltrexone did not prove more effective than placebo on the two primary outcomes. However, in the absence of MBSCT, naltrexone was significantly more effective than placebo on a clinically meaningful secondary outcome indicator: ability to achieve non-hazardous drinking. In addition, naltrexone was more effective than placebo on a clinically descriptive outcome: negative consequences of drinking.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Lisa Smith, Katherine Schaumberg, Svetlana Zilberman, Bram Heidinger, Lisa Hail, Mark Byon, Brett Hagman, and Christine Davis for their important contributions to this study's implementation and data management.

This work was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grants 5 RO1 AA015553 and K24 AA013736.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: Dr. Kranzler has received consulting fees from Alkermes, GlaxoSmithKline, Gilead, and Lundbeck and research support from Merck. He also reports associations with Eli Lilly, Merck, Janssen, Schering Plough, Lundbeck, Alkermes, GlaxoSmithKline, Abbott, and Johnson & Johnson, as these companies provide support to the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology Alcohol Clinical Trials Initiative (ACTIVE) and he receives support from ACTIVE.

Contributor Information

Jon Morgenstern, Columbia University.

Alexis N. Kuerbis, Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene, Inc. and Columbia University

Andrew C. Chen, Columbia University

Christopher W. Kahler, Brown University

Donald A. Bux, Jr., Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene, Inc.

Henry R. Kranzler, University of Pennsylvania, Perelman School of Medicine

References

- Anton R, Moak D, Waid R, Latham PK, Malcolm RJ, Dias JK. Naltrexone and cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of outpatient alcoholics: Results of a placebo-controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:1758–1764. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.11.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton R, Moak DH, Latham P, Waid LR, Myrick H, Voronin K, Woolson R. Naltrexone combined with either cognitive behavioral or motivational enhancement therapy for alcohol dependence. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2005;25(4):349–357. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000172071.81258.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton R, O'Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, Donovan DM, Zweben A. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence. The COMBINE study: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295:2003–2017. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor T, Steinberg K, Anton R, Del Boca FK. Talk is cheap: Measuring drinking outcomes in clinical trials. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:55–63. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balldin J, Berglund M, Borg S, Mansson M, Bendtsen P, Franck J, Willander A. A 6-month controlled naltrexone study: Combined effect with cognitive behavioral therapy in outpatient treatment of alcohol dependence. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:1142–1149. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000075548.83053.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory. Second Edition Manual Harcourt Brace; San Diego, CA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Buck JA. The looming expansion and transformation of public substance abuse treatment under the Affordable Care Act. Health Affairs. 2011;30(8):1402–1410. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Carey MP, Maisto SA, Henson JM. Temporal stability of the Timeline Followback Interview for alcohol and drug use with psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:774–781. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Nich C, Sifry RL, Nuro KF, Frankforter TL, Ball SA, Rounsaville BJ. A general system for evaluating therapist adherence and competence in psychotherapy research in the addictions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;57:225–238. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . HIV among Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Center for HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cottler LB, Robins LN, Helzer JE. The reliability of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Substance Abuse Module-(CIDI-SAM): A comprehensive substance abuse interview. British Journal of Addiction. 1989;84:801–814. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon FR, Turner CW, Robbins MS, Szapocznik J. Concordance among biological, interview, and self-report measures of drug use among African American and Hispanic adolescents referred for drug abuse treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19(4):404–413. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk D, Wang XQ, Liu L, Fertig J, Mattson ME, Ryan M, Litten RZ. Percentage of subjects with no heavy drinking days: Evaluation as an efficacy endpoint for alcohol clinical trials. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34(11):1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. Biometric Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou P, Dufour MC, Compton WM, Kaplan K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heather N, Rollnick S. Readiness to change questionnaire: User's manual. University of Northumbria at Newcastle; Newcastle, England: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Heinälä P, Alho H, Kiianmaa K, Lönnqvist J, Kuoppasalmi K, Sinclair JD. Targeted use of naltrexone without prior detoxification in the treatment of alcohol dependence: A factorial double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2001;21(3):287–292. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200106000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hester RK. Self-control training. In: Hester RK, Miller WR, editors. Handbook of alcoholism treatment approaches: Effective alternatives. 2nd ed. Allyn & Bacon; Needham Heights, MA: 1995. pp. 148–159. [Google Scholar]

- Hong VT, Koblin B. HIV, alcohol, and noninjection drug use. Current Opinion in HIV & AIDS. 2009;4(4):314–318. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32832aa902. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32832aa902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin TW, Morgenstern J, Parsons JT, Wainberg ML, Labouvie E. Alcohol and sexual HIV risk behavior among problem drinking men who have sex with men: An event level analysis of timeline followback data. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10(3):299–307. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BA, DiClemente CC, Ait-Daoud N, Stoks SM. Brief Behavioral Compliance Enhancement Treatment (BBCET) manual. In: Johnson BA, Ruiz P, Galanter M, editors. Handbook of Clinical Alcoholism Treatment. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore, MD: 2003. pp. 282–301. [Google Scholar]

- Jupp B, Lawrence AJ. New horizons for therapeutics in drug and alcohol abuse. Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2010;125:138–168. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.002. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karhuvaara S, Simojoki K, Virta A, Rosberg M, Löyttyniemi E, Nurminen T, Mäkelä R. Targeted nalmefene with simple medical management in the treatment of heavy drinkers: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled multicenter study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31(7):1179–1187. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenna GA, Longabaugh R, Gogineni A, Woolard RF, Nirenberg TD, Becker B, Karolczuk K. Can the Short Index of Problems (SIP) be improved? Validity and reliability of the 3-Month SIP in an emergency department sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66(3):433–437. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblin BA, Husnik MJ, Colfax G, Huang Y, Madison M, Mayer K, Buchbinder S. Risk factors for HIV infection among men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2006;20:731–739. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000216374.61442.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranzler HR, Armeli S, Tennen H, Blomqvist O, Oncken C, Petry N, Feinn R. Targeted naltrexone for early problem drinkers. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2003;23(3):294–304. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000084030.22282.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranzler HR, Tennen H, Armeli S, Chan G, Covault J, Arias A, Oncken C. Targeted naltrexone for problem drinkers. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;29(4):350–357. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181ac5213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuerbis A, Morgenstern J, Hail LA. Predictors of moderated drinking in a primarily alcohol dependent sample of men who have sex with men. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011 doi: 10.1037/a0026713. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/a0026713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latt NC, Jurd S, Houseman J, Wutzke S. Naltrexone in alcohol dependence: A randomised controlled trial of effectiveness in a standard clinical setting. Medical Journal of Australia. 2002;176:530–534. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang K, Zeger SL. Longitudinal analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Madson MB, Campbell TC. Measures of fidelity in motivational enhancement: A systematic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;31:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR. Treating substance use disorders with adaptive continuing care. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Carise D, Kleber HD. Can the national addiction treatment infrastructure support the public's demand for quality care? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;25:117–121. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00156-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Del Boca FK. Measurement of drinking behavior using the Form 90 family of instruments. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;12(Suppl.):112–118. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Tonigan JS, Longabaugh R. NIAAA Project MATCH Monograph Series Volume 4. Vol. 4. NIAAA Project MATCH Monograph Series; Rockville, MD: 1995. The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC): An instrument for assessing adverse consequences of alcohol abuse. Test manual. [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Irwin TW, Wainberg ML, Parsons JT, Muench F, Bux DA, Schulz-Heik J. A randomized controlled trial of goal choice interventions for alcohol use disorders among men-who-have-sex-with-men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75(1):72–84. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss HB, Chen CM, Yi HY. Subtypes of alcohol dependence in a nationally representative sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;91(2-3):149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer A, Finney JW, Swearingen CE, Vergun P. Brief interventions for alcohol problems: A meta-analytic review of controlled investigations in treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking populations. Addiction. 2002;97(3):279–292. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley SS, Froehlich JC. Advances in the use of naltrexone: An integration of preclinical and clinical findings. In: Galanter M, editor. Recent Developments in Alcoholism XVI: Research on Alcoholism Treatment. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; New York: 2003. pp. 217–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley SS, Jaffe AJ, Chang G, Schottenfeld RS, Meyer RE, Rounsaville BJ. Naltrexone and coping skills therapy for alcohol dependence: A controlled study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992;49:881–887. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820110045007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oslin DW, Lynch KG, Pettinati H, Kampman KM, Gariti P, Gelfand L, O'Brien CP. A placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial of naltrexone in the context of different levels of psychosocial intervention. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32(7):1299–1308. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00698.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrow D, Stall R. Alcohol, tobacco, and drug use among gay and bi Men. In: Wolitski RJ, Stall R, Valdiseri RO, editors. Unequal opportunity: Health disparities affecting gay and bisexual men in the US. Oxford University Press; New York: 2008. pp. 121–158. [Google Scholar]

- Pettinati H, O'Brien C, Rabinowitz AR, Wortman SM, Oslin DW, Kampman KM, Dackis CA. The status of naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence: Specific effects on heavy drinking. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2006;26(6):610–625. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000245566.52401.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman PM, Abraham AJ, Knudsen HK. Using medication-assisted treatment for substance use disorders: Evidence of barriers and facilitators of implementation. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:584–589. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.032. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rösner S, Hackl-Herrwerth A, Leucht S, Vecchi S, Srisurapanont M, Soyka M. Opioid antagonists for alcohol dependence. Cochrane Database Systematic Review. 2010;8(12):CD001867. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001867.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosner S, Leucht S, Lehert P, Soyka M. Acamprosate supports abstinence, naltrexone prevents excessive drinking: Evidence from a meta-analysis with unreported outcomes. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2008;22:11–23. doi: 10.1177/0269881107078308. doi: 10.1177/0269881107078308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Craig M, Annis HM, Bornet AR, MacDonald KR. Random assignment to abstinence and controlled drinking: Evaluation of a cognitive-behavioral program for problem drinkers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1984;52:390–403. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.52.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS software, Version 9.2 for Windows. Author; Cary, NC: 2002-2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shoptaw S, Frosch D. Substance abuse treatment as HIV prevention for men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2000;4(2):193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell MB, Maisto SA, Sobell LC, Cooper AM, Cooper T, Saunders B. Developing a prototype for evaluating alcohol treatment effectiveness. In: Sobell LC, Ward E, editors. Evaluating alcohol and drug abuse treatment effectiveness: Recent advances. Pergamon; New York: 1980. pp. 129–150. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger DC. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Consulting Psychologist Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Srisurapanont M, Jarusuraisin N. Naltrexone for the treatment of alcoholism: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;8:267–280. doi: 10.1017/S1461145704004997. doi: 10.1017/S1461145704004997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes ME, Davis CS, Koch GG. Categorical data analysis using the SAS system. 2nd ed. SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- The EXPLORE Study Team Effects of a behavioural intervention to reduce acquisition of HIV infection among men who have sex with men: The EXPLORE randomised controlled study. The Lancet. 2004;364:41–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16588-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonigan JS, Miller WR, Brown JM. The reliability of Form 90: An instrument for assessing alcohol treatment outcome. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:358–364. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services . Helping patients who drink too much: A clinician's guide. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, MD: 2005. NIH Publication No. 07-3769. [Google Scholar]

- Velasquez MM, von Sternberg K, Johnson DH, Green C, Carbonari JP, Parsons JT. Reducing sexual risk behaviors and alcohol use among HIV-positive men who have sex with men: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(4):657–667. doi: 10.1037/a0015519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinson DC, Reidinger C, Wilcosky T. Factors affecting the validity of a Timeline Followback Interview. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:733–740. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren KR, Hewitt BG. NIAAA: Advancing alcohol research for 40 years. Alcohol Research & Health. 2010;33(1-2):5–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willenbring M. A broader view of change in drinking behavior. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31(s3):84s–86s. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willenbring M. The past and future of research on treatment of alcohol dependence. Alcohol Research & Health. 2010;33(1-2):55–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]