Abstract

Suppressing hyperactive endocannabinoid tone is a critical target for reducing obesity. The backbone of both endocannabinoids 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) and anandamide (AEA) is the ω-6 fatty acid arachidonic acid (AA). Here we posited that excessive dietary intake of linoleic acid (LA), the precursor of AA, would induce endocannabinoid hyperactivity and promote obesity. LA was isolated as an independent variable to reflect the dietary increase in LA from 1 percent of energy (en%) to 8 en% occurring in the United States during the 20th century. Mice were fed diets containing 1 en% LA, 8 en% LA, and 8 en% LA + 1 en% eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) + docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) in medium-fat diets (35 en% fat) and high-fat diets (60 en%) for 14 weeks from weaning. Increasing LA from 1 en% to 8 en% elevated AA-phospholipids (PL) in liver and erythrocytes, tripled 2-AG + 1-AG and AEA associated with increased food intake, feed efficiency, and adiposity in mice. Reducing AA-PL by adding 1 en% long-chain ω-3 fats to 8 en% LA diets resulted in metabolic patterns resembling 1 en% LA diets. Selectively reducing LA to 1 en% reversed the obesogenic properties of a 60 en% fat diet. These animal diets modeled 20th century increases of human LA consumption, changes that closely correlate with increasing prevalence rates of obesity. In summary, dietary LA increased tissue AA, and subsequently elevated 2-AG + 1-AG and AEA resulting in the development of diet-induced obesity. The adipogenic effect of LA can be prevented by consuming sufficient EPA and DHA to reduce the AA-PL pool and normalize endocannabinoid tone.

Introduction

Excessive endocannabinoid system activity is likely to have a causal role in obesity acting through multiple organ systems, but has not as yet been linked to the worldwide epidemic of obesity. The endocannabinoid system includes the two endogenous ligands 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) and N-arachidonoylethanolamine (anadamide or AEA) and two cannabinoid receptors (CB1 and CB2). Central CB1 receptor activation by increased endocannabinoid levels or exogenous agonists induces hyperphagia along with increased lipogenesis and peripheral adiposity (1,2). CB1 receptors are predominantly expressed in the brain, but also in the peripheral tissues of the gastrointestinal tract, adrenal glands, liver, adipose tissue, and skeletal muscles (3). In the liver, CB1 activation increases de novo lipogenesis through stimulation of cytosolic fatty acid synthase activity leading to fatty liver and obesity (2). Pharmacological blockade of the CB1 receptor is effective in treating obesity and related metabolic derangements. However serious psychiatric side effects, including suicidal tendencies (4), caused marketplace withdrawal of Rimonobant, a selective CB1 antagonist, and have impaired further pharmaceutical development. We postulated that in lieu of a better antiobesity drug, addressing an underlying cause of endocannabinoid hyperactivity may prove to be a viable and safe preventative alternative for decreasing obesity.

Endocannabinoids are endogenous lipid mediators made from essential fatty acids available only from dietary sources. The two best characterized endocannabinoids, 2-AG and AEA, are both metabolic derivatives of a single fatty acid precursor, the ω-6 arachidonic acid (AA, 20:4n-6) in phospholipids (AA-PL). Since humans cannot synthesize AA de novo, tissue PL concentrations are dependent upon the competition between dietary intakes of ω-6 and ω-3 fats (5): (i) linoleic acid (LA, 18:2n-6, the precursor to AA), (ii) preformed dietary AA, (iii) α-LA (18:3n-3, the precursor to eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20:5n-3) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n-3), and (iv) preformed dietary EPA and DHA. Endocannabinoids are formed enzymatically on demand from the pool of ω-6 membrane PL-fatty acid precursors (6). During the 20th century, elevations in AA-PL have been estimated from the dramatic increase in dietary LA resulting from a >1,000-fold increase in the estimated per capita consumption of soybean oil from 0.006 to 7.38% of energy (7). Here, we modeled these ecological dietary changes in mice to determine if increasing LA as a controlled dietary variable could elevate AA-PL composition, increase endocannabinoid levels, and induce metabolic and phenotypic changes consistent with obesity.

Methods and Procedures

Ethical statement

The experiment was performed under protocol (Animal Study Proposal no. LMBB-JH-01) approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Institute of Alcohol and Alcoholism, and followed the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Animals

Mice pregnant for 2 weeks ((e 14) C57BL/6j; Charles River Laboratories, Stone Ridge, NY) were randomly assigned to experimental diets (Table 1). Each litter (adjusted to six pups within 48 h of birth) was maintained on the same diet with its respective mother. The animals were maintained on a 12:12 h light-dark cycle. Three to four male pups from each litter were weaned after 23 days and were housed two per cage (two pups from the same litter). One animal in each cage was ear punched and used for data analysis. Individual weights were recorded for both animals twice a week.

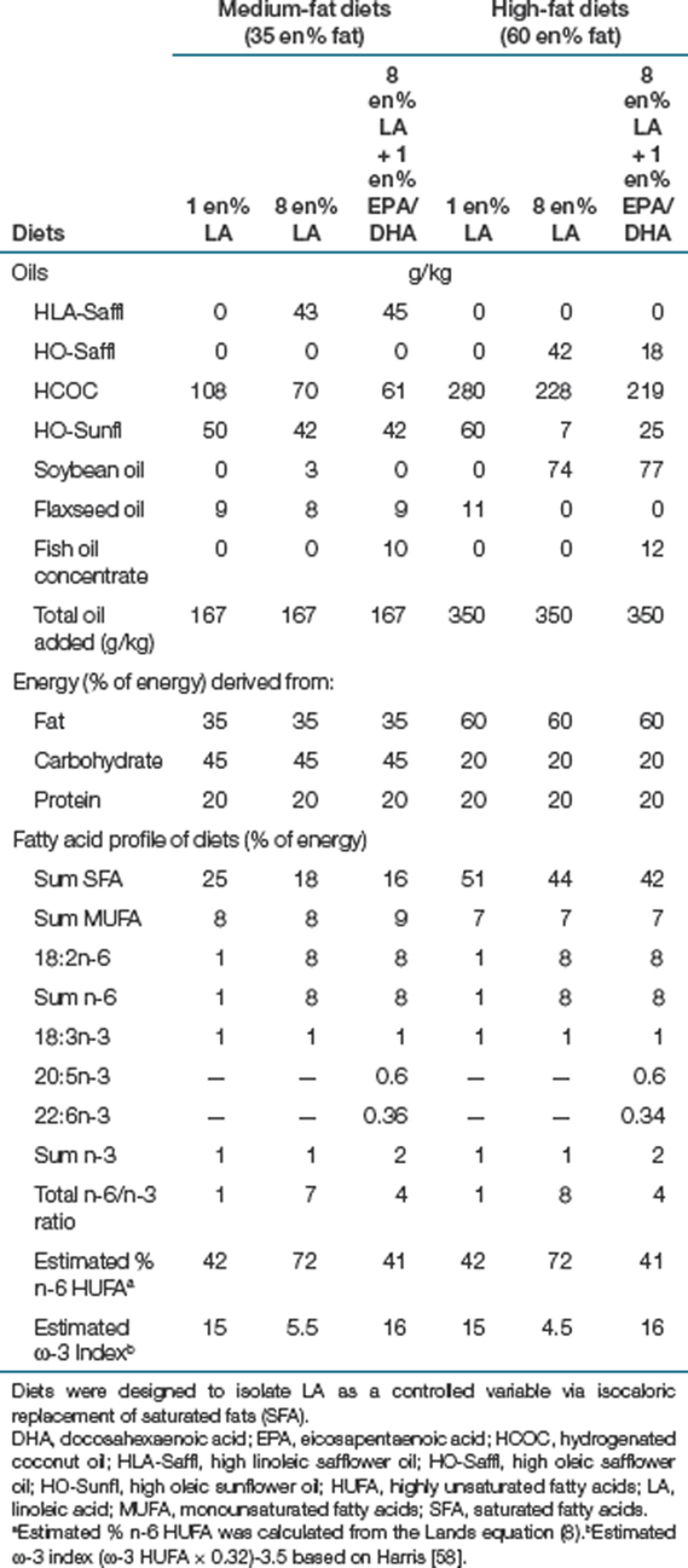

Table 1. Diet composition and fatty acid profile of diets.

Diets

Food provided as pellets (medium-fat diets) and pastes (high-fat diets), was available ad libitum for 14 weeks. Dyets (Bethlehem, PA) prepared all diets containing the same 20 en% protein (casein) and (g/kg): sucrose 75, cellulose 50, mineral mix 47, vitamin mix 13.5, l-cystein 3 and choline bitartrate 2.5, ethoxyquin 0.06. Protein and carbohydrate sources were chosen so as to have minimal background fat content. LA was isolated as an independent variable by mixing seven different oils to maintain equivalent amounts of α-LA and monounsaturates (Table 1). Modifications in dietary LA were offset solely with reciprocal changes in saturated fatty acids. For example, the diets with 1 en% LA contained 7 en% more saturated fat compared to the 8 en % LA diets. Medium-fat (35 en%) and high-fat (60 en%) diets differed only by greater amounts of saturated fats offset by the carbohydrate sources; dextrin, dyetrose, and sucrose. Food intake was measured every other day by weighing each food cup and spillage and subtracting the previously collected weight.

Endocannabinoid analysis

Stable isotope dilution gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS/MS) analysis was employed to determine 2-AG, 1-AG, and AEA. Lipids were extracted from liver or brain (thalamus/hippocampus region) as modified from Folch (8). In brief, about 100 mg of frozen tissues were homogenized in icy 0.75 ml Tris buffer (50 mmol/l, pH 8.0), 1 ml of isopropanol:methanol (4:1), 2 ml of chloroform. The lower organic phase was extracted after centrifugation 1,800g × 5 min; the remainder was extracted with chloroform once more. The combined lipid extract was dried under a stream of nitrogen and precipitated with 2 ml of acetone at −20 °C for 30 min. Acetone-treated lipid extract was centrifuged to remove precipitation, dried, and trimethylsilylated with TMT (TMSI:MSTFA:TMCS = 3:3:2) for liver or TBT (TMSI:BSTFA:TMCS = 3:3:2) for brain 30 min at 70 °C. Internal standards, 2H5-2-AG (125 pmol for liver, 1.3 nmol for brain), 2H4- AEA (30 pmol for both liver and brain), were added to each sample before lipid extraction. An Agilent 7000A mass spectrometer triple quad equipped with an Agilent 7890A gas chromatography (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) was used for the quantification of 2-AG and AEA; 1-AG was measured using 2H5-2-AG as internal standard. An aliquot of 1 µl of trimethylsilyl ester per sample was injected onto two DB-1MS capillary columns (15 m in length × 0.25 mm internal diameter × 0.25 µm film) with helium as carrier gas and configured with backflush. The gas chromatographic oven temperature was programmed from 170 to 290 °C at 2–3 °C/min followed by holding for 5 min. Multiple reaction monitoring of the product ions from the precursor ions of the analyte of interest were carried out and quantitated. Details on the ions monitored (m/z) are as following: 507→147 was for 2-AG and 1-AG, 512→147 for 2H5-2-AG; 404→118 for AEA, 408→122 for 2H4-AEA. Calibration curves (r2 > 0.995) were built for both 2-AG and AEA. They are linear in the range of 0–2 µg/g for 2-AG in liver; 0–10 µg/g for 2-AG in brain; 0–210 ng/g for AEA in both liver and brain. The linearity of 1-AG was estimated by applying 2H5-2-AG as internal standard, r2 = 0.99 for liver, r2 = 0.999 for brain at the similar range as 2-AG. Both 2-AG and 1-AG were detectable to 0.0246 ng or 0.0651 pmol. Specifically, that recovery for AEA, 1-AG, and 2-AG (96%, n = 3) was within-assay precision for 2-AG (5.4%, n = 3). Since 1-AG and 2-AG undergo rapid isomerization, it is difficult to report quantities of each species originating from tissues with certainty (9), thus results are reported as the sum of the individual peaks of 2-AG + 1-AG.

Fatty acid analysis in PL

Hypothalamus and liver were extracted by a modification of the Folch method (8) using 23:0 phosphatidylcholine as internal standard. PL were separated using solid-phase extraction (a 3-ml solid-phase extraction columns, packed with polar phase aminopropylsilane (NH2) bonded to silica gel made by Mallinckrodt Baker (Phillipsburg, NJ), with the weight of stationary phase was 500 mg per column) based on Agren et al. (10); 1 ml of the chloroform extract was dried down under nitrogen and reconstituted in 500 µl of 100:3:0.3 hexane:methyl tert-butylether:acetic acid for solid-phase extraction. A 3 ml solid-phase extraction column was rinsed with 2 × 2 ml hexane under vacuum to maintain solvent flow rate of about 1–2 drops/s. The sample was loaded to the column and cholesterol esters were eluted with 2 × 2 ml hexane. The triglyceride fraction was eluted with 2 × 2 ml 2:1 (vol/ vol) hexane:chloroform, the free fatty acids were eluted with 2 × 2 ml 100:2:2 (vol/vol) chloroform:methanol:actetic acid and the PL fraction was eluted and collected with 2 × 2 ml 4:1 (vol/vol) isopropanol:3N HCl. The PL fraction was transmethylated with 14% boron triflouride-MeOH at 100 °C for 60 min and methyl esters were analyzed by gas chromatography (11). Erythrocytes were added to cold butylated hydroxytoluene (50 µg/ml)—methanol with 22:3n-3 as internal standard. Samples were vortexed for 1 min, 1 ml chloroform was added and samples were vortexed for 1 min. The samples were frozen overnight at −80 °C, thawed the following day, vortexed briefly and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min. The chloroform layer was transferred and pellets were re-extracted with 2 ml chloroform:methanol (1:1, vol/ vol), vortexed for 1 min and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min. Then 1.8 ml of double distilled H2O was added and vortexed briefly. The chloroform phase was transferred to a new tube, methylated and analyzed as described for hypothalamus and liver.

mRNA analysis and plasma hormones

RNA was purified from liver and white adipose tissues (12) and real-time reverse transcription PCR (13) conducted for messenger RNA (mRNA) levels of SREBP-1c, FAS, ACC1, AMPK a2, and AMPK a2. Plasma levels of leptin, adiponectin, and insulin were determined using enzyme immunoassay (ALPCO Diagnostics, Salem, NH).

Statistics

All data are analyzed using STATISTICA version 8.0 (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK). Data were analyzed for homogeneity of variance (Levene's test) which was nonsignificant except for fatty acids, 2-AG, insulin, and mRNA data that were thus analyzed using Mann–Whitney U-test. Multiple testing was corrected by adjusting to P < 0.01 and statistical tendency was considered when P < 0.05. The other data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, and Fisher's least significant difference post hoc test, with P < 0.05. Data are presented as ± s.e.m.

Results

Dietary LA increased tissue LA-PL, AA-PL, 2-AG + 1-AG, and AEA

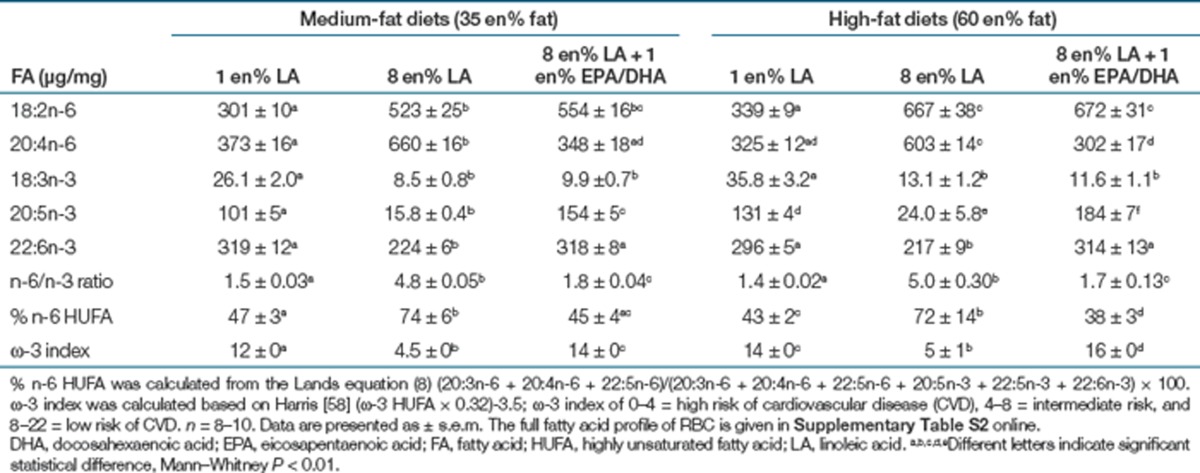

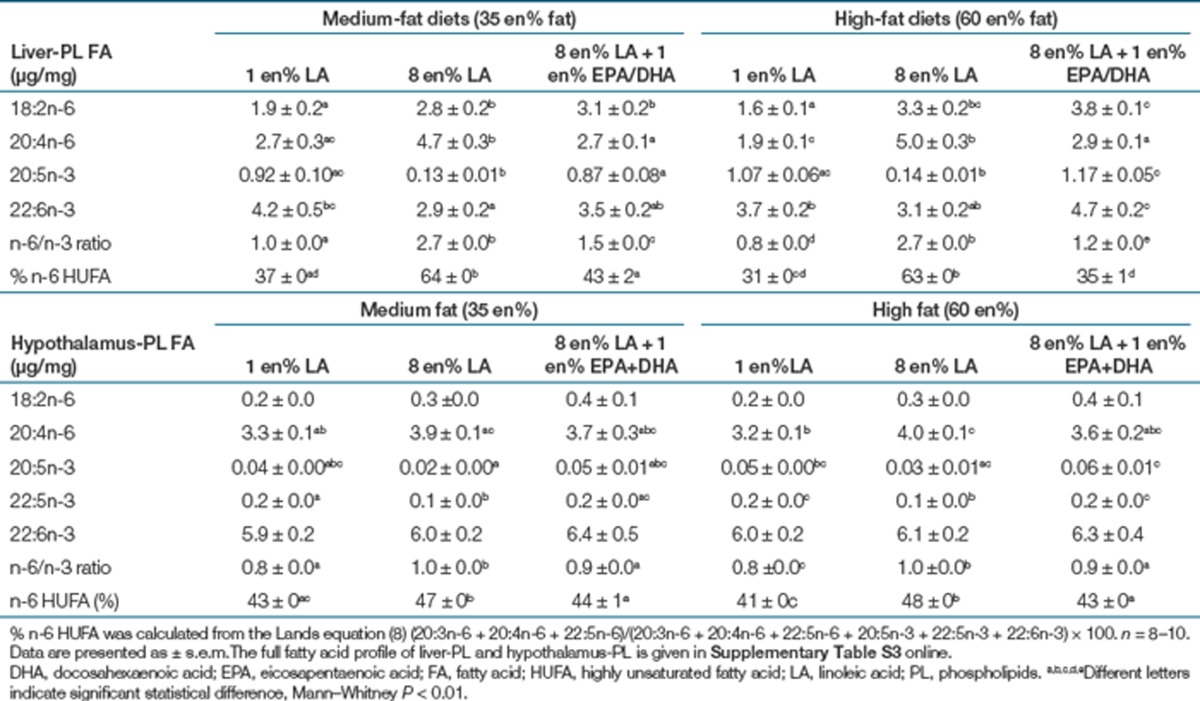

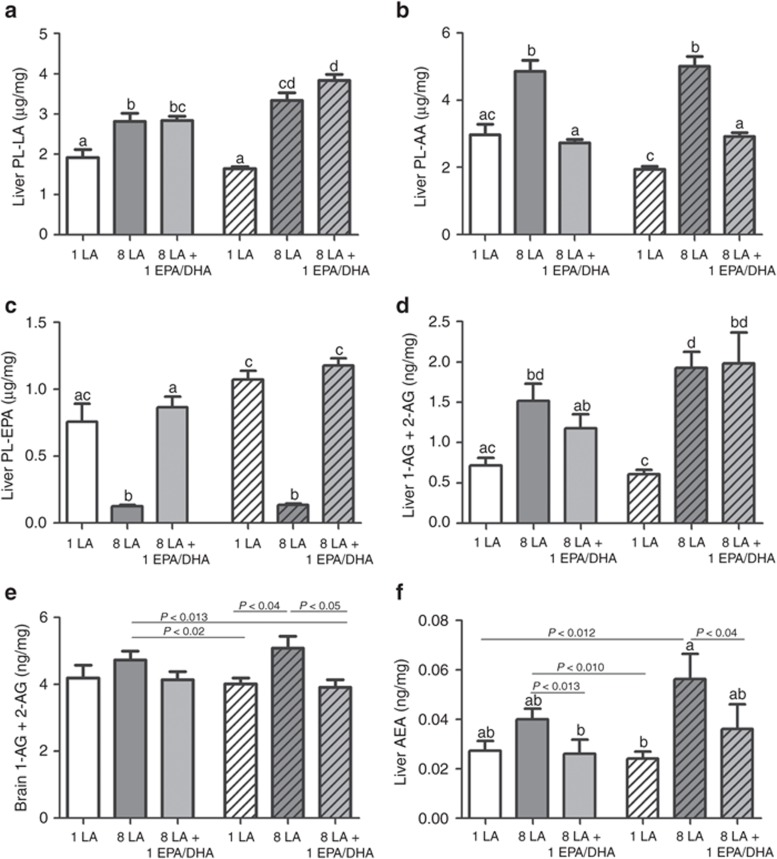

The 8 en% LA diets significantly elevated LA-PL and AA-PL in erythrocytes (Table 2), liver (Table 3, Figure 1a,b), and hypothalamus (Table 3) compared to the 1 en% LA diets. Consequently, elevating LA nearly tripled liver 2-AG + 1-AG and AEA in both medium- and high-fat diets (Figure 1d,f). EPA was nearly fivefold higher in both liver (Figure 1c) and erythrocytes (Table 2) in the 1 en% compared to the 8 en% LA diets. Lowering LA to 1 en% elevated erythrocyte (Table 2) and liver DHA (Table 3) to levels similar to adding preformed EPA and DHA at 1 en%, for most diets.

Table 2. Concentration of major ω-6 and ω-3 fatty acids in RBC phospholipids (µg/mg).

Table 3. Concentration of major ω-6 and ω-3 fatty acids in liver and hypothalamus phospholipids (µg/mg).

Figure 1.

Selective elevation of dietary LA elevates AA precursors and endocannabinoids in mice fed medium-fat diets (open bars) and high-fat diets (coarse bars). Dietary LA at 1 en% is indicated by white bars, 8 en% LA by dark gray bars, and 8 en% LA + 1 en% EPA/DHA by light gray bars. Dietary LA (8 en%) elevates (a) liver LA in phospholipids (PL) (µg/mg) and (b) liver PL-AA (µg/mg). Compared to 8 en% LA, diets of 1 en% dietary LA allows endogenous accretion of (c) liver PL–EPA (µg/mg), levels equal to consuming 1 en% EPA/DHA directly. Increasing dietary LA from 1 en% to 8 en% elevates (d) liver 1-AG + 2-AG (ng/mg) (by over fourfold), (e) brain 1-AG + 2-AG (ng/mg), and (f) liver AEA (ng/ml). The addition of 1 en% EPA/DHA reduces the endocannabinoid precursor pool and tissue concentrations of 2-AG and AEA. a,b,c,dDiffering letters indicate P < 0.01 and lines by specified values by Mann–Whitney testing. Lines indicate differences at P values shown. n = 9–10. 2-AG, 2-arachidonoylglycerol; AA,arachidonic acid; AEA, anandamide; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; LA,linoleic acid.

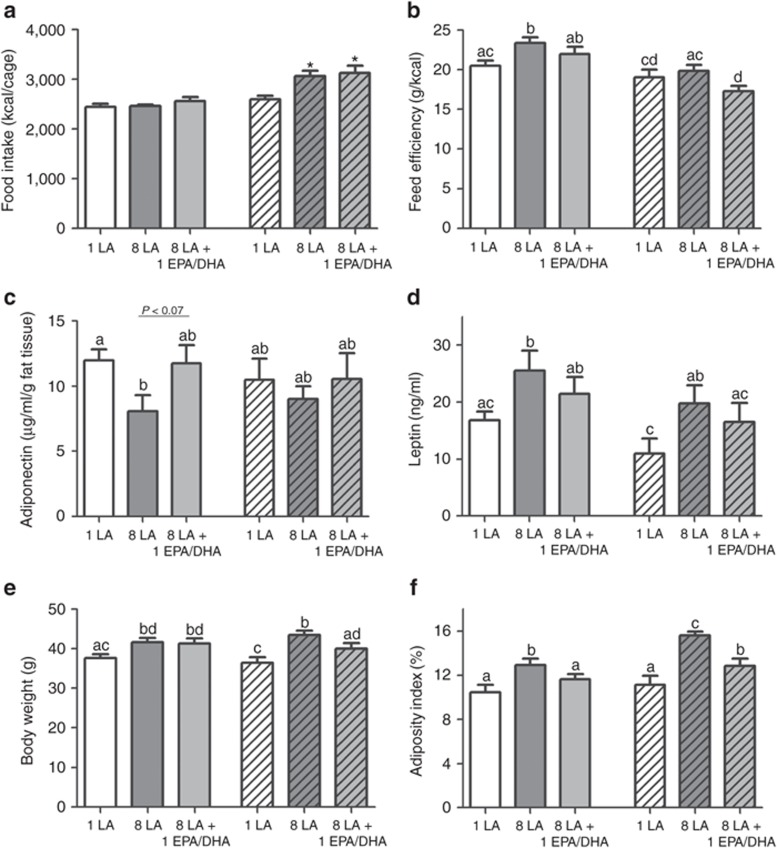

Dietary LA increased food intake, body weight, and adiposity

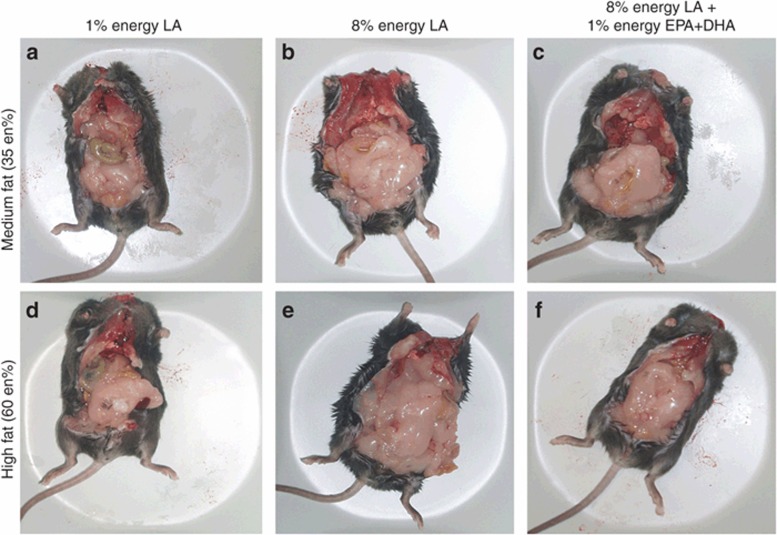

The 8 en% LA diets increased body weight (Figure 2e and Supplementary Figures S1 and S2 online) and adiposity (Figure 2f and Figure 3) compared to 1 en% of LA. Food intake was lower in the 1 en% LA high-fat diet, compared to the other high-fat diets, resulting in a caloric intake of the 1 en% LA high-fat diet similar to the medium-fat diets (Figure 2a). The 8 en% LA diets increased feed efficiency compared to the 1 en% LA fed animals (Figure 2b). The medium-fat diets had a higher feed efficiency compared with high-fats diets (22.0 ± 0.5 mg/kcal and 18.8 ± 0.5 mg/kcal respectively, P < 0.0001). Remarkably animals fed a 35 en% fat diet with 8 en% LA had significantly greater adiposity than animals fed a 60 en% fat diet with 1 en% LA (Figure 2f), an indication that it is the 8 en% LA that triggered the endocannabinoid mediated adiposity. Animals fed 8 en% as LA had more visible adipose tissue in both medium- and high-fat diets (Figure 3). Thus, the selective reduction of LA decreased food intake in the high-fat diet and reduced adiposity and feed efficiency regardless of diet.

Figure 2.

Dietary LA induces adiposity in mice fed medium-fat diets (open bars) and high-fat diets (coarse bars). Dietary LA of 8 en% increases (a) food intake in high-fat diets, (b) feed efficiency in medium-fat diets, (c) reduces plasma adiponectin (µg/ml/g fat tissue), and increases (d) plasma leptin (ng/ml). Compared to a diet of 1 en% LA, 8 en% LA also increases (e) body weight and (f) adiposity index. Adding 1 en% EPA/DHA reverses the effects of 8 en% diets. Feed efficiency; (body weight gain/Mcal intake), adiposity index ((subcutaneous + retroperitoneal + inguinal fat pads)/eviscerated body weight × 100). Adiponectin levels were adjusted for gram fat tissue dissected out (subcutaneous + inguinal + retroperitoneal fat pads). a,b,c,dDiffering letters indicate P < 0.05 by ANOVA, leptin, and adiponectin; n = 6, other parameters; n = 9–10. DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; LA,linoleic acid.

Figure 3.

Reducing dietary LA to 1 en% prevents adipose tissue accumulation and reverses the obesogenic effects of a high-fat (60 en%) diet. Animals fed 8 en% LA (b,e) accumulated more fat than animals fed 1 en% LA (a,d). The addition of 1 en% n-3 EPA/DHA to 8 en% LA diets (c,f) prevented the increase in adipose tissue seen in animals fed 8% energy LA in b,e. The obesogenic properties of a high-fat diet (60 en% fat) in e were reversed by selective reduction of LA from 8 en% to 1 en% and replacement by greater saturated fat in d. The animals shown are representative for the animals in each dietary treatment. Upper row; isocaloric medium-fat diets of 35 en% fat, lower row; isocaloric high-fat diets of 60 en% fat. The fatty acid composition, not total fat calories, determined the obesogenic properties of the diets. DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; LA,linoleic acid.

Dietary EPA and DHA decreased tissue AA-PL, 2-AG + 1-AG, AEA, and adiposity

We sought to determine if the changes in 2-AG + 1-AG and adiposity phenotypes were due to lowering LA or lowering the endocannabinoid precursor AA-PL as a proportion of the PL precursor pool (the percentage of n-6 highly unsaturated fatty acids (HUFA) or % n-6 in HUFA). Adding dietary EPA and DHA (1 en%) to the 8 en% LA diet reversed the elevations of AA-PL (Figure 1b), 2-AG + 1-AG (Figure 1d,e) and liver AEA (Figure 1f) in a pattern similar to lowering LA to 1 en%. Addition of 1 en% EPA/DHA to the 8 en% LA diets prevented the increase in tissue % n-6 in HUFA (Tables 2 and 3) induced by the 8 en% LA diet, and decreased both feed efficiency and adiposity (Figure 2b,f). Liver and brain 2-AG + 1-AG (Figure 1d,e), liver AEA (Figure 1f), and plasma leptin (Figure 2d) levels trended to be lower in animals fed 8 en% LA + EPA/DHA diets compared to the 8 en% LA diets. The addition of 1 en% EPA/DHA to the 8 en% LA diets greatly increased the ω-3 index in erythrocytes from 4.5 to 16 (P < 0.0000001) (Table 2). The 1 en% LA diets without added EPA/DHA produced an ω-3 index between 12 and 14 in the medium- and high-fat diets respectively (Table 2). These results indicate that reducing the endocannabinoid precursor pool of AA-PL by either lowering dietary LA or raising EPA/DHA is similarly effective in lowering 2-AG + 1-AG and AEA concentrations.

Dietary LA increased leptin and decreased adiponectin

Animals fed the 8 en% LA diets had higher levels of leptin (Figure 2d) and lower adiponectin levels (Figure 2c) in plasma compared to animals fed 1 en% LA. A similar pattern was seen with addition of 1 en% EPA and DHA to the 8 en% LA diets. Insulin levels did not differ by diet (Supplementary Table S1 online). The fact that insulin levels did not change may suggest that despite the development of obesity in these mice, they were not hyperinsulinemic and may not have reached a state of metabolic dysregulation typical of complications seen in the metabolic syndrome.

Dietary LA did not increase lipogenic gene expression

The differences in mRNA expression were more affected by the total amount of fat and total amount of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) in the diet than the differences in LA and EPA/DHA content and do not follow the diet-induced patterns of adiposity and endocannabinoid levels (Supplementary Figures S3 and S4 online). As expected, high-fat diets trended to suppress mRNA expression for SREBP-1c, FAS, ACC1, AMPKa1, and AMPKa2 compared to medium-fat diets (Supplementary Figure S3 online). Within the high-fat diets, greater amount of total PUFA, as in the 8 en% LA + 1 en% EPA/DHA high-fat diet, trended to suppress the liver and white adipose tissue expression of SREBP-1c, FAS, ACC1, adiponectin, resistin, and AMPKa1 or AMPKa2.

Ecological comparison

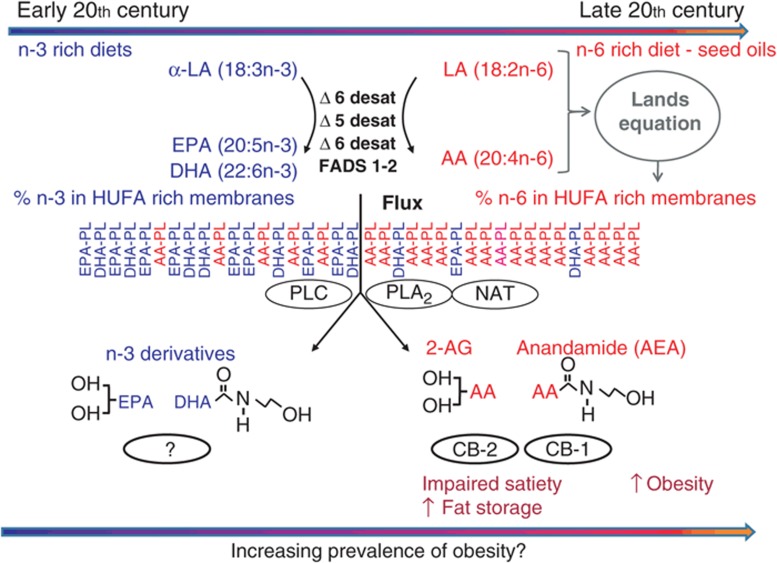

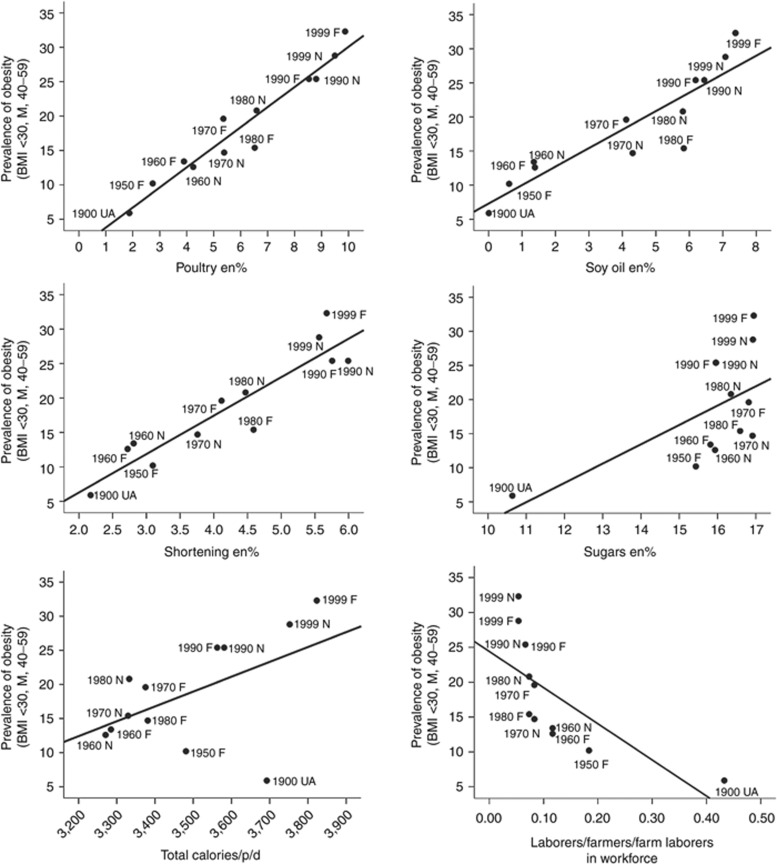

We selected rodent diets of 1 en% and 8 en% LA to reflect increases in dietary intakes for this fat in the United States during the 20th century (7). We postulated that if LA induced endocannabinoid hyperactivity similarly in humans, then increased soy oil consumption would correlate with increasing prevalence rates of obesity during this time period (Figure 4). Soy bean oil is about 50% LA by weight and is the greatest contributor of increased LA in the last century. The estimated per capita consumption of food commodities and availability of essential fatty acids from 273 food commodities was calculated as previously described (7) by using economic disappearance data for each year from 1909 to 1999. We compared the change in the dietary availability of commodities and nutrients in the US food supply to the age adjusted prevalence rates of obesity (>30 BMI) for males aged 40–59 among US Union Army Veterans in 1900 (14), among National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) (15) and Framingham cohorts (16). Dietary availability of LA was calculated not only from soy oil but summed from 273 food commodities. Increased consumption of LA (en%) (r2 = 0.68, P < 0.001) and the primary dietary sources of LA; soybean oil (r2 = 0.83, P < 0.00001), poultry (r2 = 0.94, P < 0.00001) and shortening (en%) (r2 = 0.86, P < 0.00002), and sugars (en%) (r2 = 0.37, P < 0.04) were positively correlated with greater risk of obesity (Figure 5). A shift from physical labor occupations including farmers, farm laborers, and laborers was negatively correlated with prevalence of obesity (r = −0.49, P < 0.04). In contrast, changes in total energy consumption, and calories from grains, beef, all fish and seafood, eggs, dairy or vegetables were not significantly correlated with increasing rates of obesity.

Figure 4.

Dietary essential fats and the metabolism of endocannabinoids. The endocannabinoids 2-AG and anandamide (AEA) are synthesized on demand from the essential fatty acid arachidonic acid (AA) (20:4n-6) in membrane phospholipids (AA-PL). AA in the phospholipid precursor pool can be elevated by dietary linoleic acid (LA) (18:2n-6) or diminished consumption of omega-3 fatty acids notably eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Activation of the cannabinoid receptors (CB1 and CB2) by the AA-PL derived endocannabinoids, AEA and 2-AG, both centrally and peripherally, favors metabolic processes that stimulate appetite, increase food intake, activates fat storage pathways, promotes adipocyte inflammation, and downregulates catabolism resulting in adipose accretion. Figure indicates the shift in available seed oil and changes in estimated tissue compositions of n-6 highly unsaturated fatty acids described in Blasbalg et al. 2010 (10). Horizontal arrows indicate the hypothesis that these shift in diet and resulting endocannabinoid levels may contribute to the increasing prevalence of obesity in the United States during the 20th century. 2-AG, 2-arachidonoylglycerol; HUFA, highly unsaturated fatty acids; NAT, N-acetyltransferase; PLA2, phospholipase A2; PLC, phospholipase C.

Figure 5.

Dietary sources of linoleic acid (LA) and increasing prevalence rates of male obesity in the United States during the 20th century. Prevalence of male obesity (40–59 years, BMI >30) in each year is indicated by source: UA-Union Army Veterans, F-Framingham cohorts, N-NHANES cohorts. Scattergrams and univariate linear regression lines are indicated in each panel. Increasing prevalence rates of male obesity are positively correlated with apparent consumption of dietary sources of LA indicated in (a) poultry a percent of energy (en%), (r2 = 0.94, P < 0.000000), (b) soybean oil (en%) (r2 = 0.82, P < 0.00005), (c) shortening (en%) (r2 = 0.86, P < 0.00002), and (d) sugars (en%) (r2 = 0.37, P < 0.04) but not to (e) total calories/p/d (r2 = 0.27, P < 0.08). Prevalence of obesity is negatively correlated with (f) declines in physical labor occupations, farmers, farm laborers, and laborers (r2 = 0.49, P < 0.01). Animal diets of 1 en% and 8 en% LA were selected to model these changes.

Discussion

Here we demonstrate that endocannabinoid hyperactivity and obesity can be caused by elevating a single molecular species in the diet, LA, an ω-6 essential fatty acid and a precursor to AA-PL, the backbone of endocannabinoids. We modeled human dietary increases in LA from 1 en% to 8 en% which significantly increased LA-PL, AA-PL in liver and erythrocytes, nearly tripled liver 2-AG and AEA, resulting in increased food intake, feed efficiency, plasma leptin, and adiposity. Decreasing AA-PL in liver and erythrocyte by adding 1 en% from EPA and DHA reduced 2-AG + 1-AG and AEA levels, reduced feed efficiency and reversed the adipogenic effects of the 8 en% LA diets. These findings demonstrate the critical importance of dietary LA to tissue AA-PL concentrations to endocannabinoid hyperactivity, as proposed by others (17–19). We utilized the Lands equation (5) to predict AA-PL compositions as the % n-6 HUFA from dietary intakes of LA, ALA, AA, and EPA/DHA, with excellent concurrence between calculated (Supplementary Table S1 online) and experimental values (Tables 2 and 3). Consistent with previous studies (20,21) our results indicate that the elongation and desaturation of ALA to EPA and DHA, and/or the acylation of EPA and DHA into the sn-2 position of tissue PL, are considerably more effective when dietary LA is below 2 en%. Moreover, in agreement with earlier studies (21–24), we show that increasing dietary LA decreased tissue n-3 HUFA.

Compared to diets of 8 en% LA, supplementing the 8 en% LA diets with 1 en% EPA/DHA resulted in lower adiposity and endocannabinoid levels. Fish oil-based diets reduced fat in diet-induced obesity (25) and supplementation with 0.8 en% EPA/DHA resulted in lower endocannabinoid levels and reduced ectopic fat deposition (17). Pups from mothers fed fish oil had lower body weight, less adipose tissue and lower 2-AG in hippocampus than pups from mothers fed hydrogenated vegetable oil (26). Although supplementation of EPA/DHA to 8 en% LA diets prevented the increase in AA-PL, EPA/DHA in a 8 en% LA diet was not equally effective as 1 en% LA in preventing excessive endocannabinoid production nor restoring metabolic disturbances. The addition of DHA and AA to a westernized diet high in LA (10.7 en%) did not support the same frontal cortex fatty acid composition as achieved by a diet low in LA (1.2 en%) (21). Hence to improve tissue EPA and DHA concentrations and prevent excessive endocannabinoid signaling emphasis should be on lowering dietary LA in addition to dietary supplementation with EPA and DHA.

Animal obesity, which is characterized by elevated endocannabinoids (27), is classically induced by 60 en% fat diets containing 8 en% LA (2). Here, lowering LA to 1 en% decreased 2-AG + 1-AG, AEA, and reversed adiposity while maintaining a 60 en% fat diet. This indicates that the causal factor for inducing obesity in the 60 en% diet was the high LA composition of 8 en%, not the high calorie density. We also note that feed efficiency was much greater in the medium-fat diets compared to the high-fat diets. One explanation is that carbohydrates supplied 45 en% for the medium-fat diets but only 20 en% for the high-fat diets (28). Activation of the CB1 receptor induces lipogenesis (2) preferentially directing carbohydrate calories towards fat production and storage. Thus the proadipogenic effect of the 8 en% LA medium-fat diet combines a high endocannabinoid tone with abundant carbohydrates resulting in a similar phenotype as the high-fat diets (29,30). Acute 1 h pharmacological activation of liver CB1 receptors with the potent synthetic agonist HU210 increased liver mRNA levels of SREBP-1c, ACC1, and FAS; and chronic 3 day treatment also caused increased transcriptional activity of the SREBP-1c in a DNA mobility shift assay (2). In the same study, feeding a high-fat diet for 3 weeks increased the basal rate of fatty acid synthesis in liver, suggesting that an early endocannabinoid-mediated increase in de novo lipogenesis is a critical component in diet-induced obesity (2). After 14 weeks of feeding, we observed an obese phenotype with the 8 en% LA diets, but we failed to induce increases in SREBP-1c, ACC1, and FAS mRNA levels in liver (Supplementary Figure S3 online). In line with previous reports (19,29,30), we find that in the patterns of mRNA expression of lipogenic gene expression in the high-fat diets were more closely related to the total PUFA content of the diets than the dietary LA.

Dietary LA of 8 en% elevated leptin levels despite higher endocannabinoid levels (1). The negative control of endocannabinoid levels by leptin may be tissue-specific, making the hypothalamus more sensitive to hormonal regulation than to precursor availability than the liver. Dietary LA of 8 en% LA reduced adiponectin levels compared to 1 en% LA and 8 en% LA + EPA/DHA. The prevention and reduction of adiposity development in mice fed 1 en% LA, and 8 en% LA + EPA/DHA, respectively, are likely a result of lower CB1 activation and higher adiponectin levels. Selectively antagonizing CB1 increased adiponectin expression and inhibited the proliferation of preadipocytes (31), whereas a CB1 antagonist downregulated adiponectin expression (32). Activation of CB1 stimulate adipocyte proliferation (31), participate in preadipocyte differentiation into mature adipocytes, induce accumulation of lipid droplets and stimulate de novo fatty acid synthesis in the liver (2) indicating the direct role of the endocannabinoid system in adipogenesis and adipocyte lipogenesis (19). A hyperactivity of endocannabinoid signaling from early age may have resulted in excessive proliferation of preadipocytes and caused greater adiposity in mice exposed to 8 en% LA from last week of gestation to 17 weeks of age compared to diets of 1 en% LA and 8 en% LA + EPA/DHA. The quality and quantity of maternal dietary fat during last week of gestation and throughout lactation directly influenced neonatal metabolism, fatty acid profile of PL, and sensitivity to endocannabinoid system manipulation (26). Although being hyperleptinemic, insulin levels in mice fed 8 en% LA did not differ from mice fed 1 en% LA; suggesting that the mice were still insulin sensitive despite an obese phenotype. Insulin-resistant adipocytes lose their ability to regulate endocannabinoid metabolism (33) and are thus unable to decrease intracellular endocannabinoid pool in response to insulin stimulation. The present study was able to model the 20th century diet and the prevalence of the obesity epidemic showing that dietary levels of 8 en% LA caused increases in the endocannabinoid precursor pool and subsequent endocannabinoid hyperactivity leading to obesity as summarized in Figure 4.

Here we isolated LA as a dietary variable to elevate endocannabinoid levels and adiposity. Our findings are consistent with prior reports (26,34,35), that fatty acids alter endocannabinoid levels in brain, plasma, adipocytes, liver, heart and adipose tissue, and organs involved in endocrine function and energy homeostasis. Artmann et al. (36) did not find that increasing LA elevated AEA or 2-AG + 1-AG in liver or adiposity; however, the short term exposure of 1 week of LA feeding did not allow adequate time for the alteration of the AA-PL precursor pool or the development of adiposity. Dietary LA of 8 en% caused more pronounced elevation of 2-AG + 1AG in liver than cerebral cortex. The brain is less influenced by dietary manipulation than other tissues; however, diets that simultaneously raised n-3 HUFA and lowered LA and lowered brain PL-AA and 2-AG (17,26,37). Brain PL-AA and 2-AG were lowered more significantly using krill oil, which contained less AA than fish oil (37), and by initiating the diet of the mothers during pregnancy compared to treatment of adults for 4 weeks (17,26,37). A critical following question is whether the pool of AA-PL, and endocannabinoid derivatives, can be reduced by either selectively lowering dietary LA or selectively raising dietary n-3 HUFAs. In this study, selectively reducing dietary LA from 8 en% to 1 en% to and lowered n-6 HUFA from 48 to 41% in hypothalamus, associated with lower levels of 2-AG + 1AG, but not AEA, in thalamus/hippocampus region. As predicted, we found that adding 1 en% EPA/DHA to the high-fat 8 en% LA diet reduced 2–AG + 1AG in brain, and AEA in liver of mice fed 8 en% LA and thus the lowering of dietary LA to 1 en% was just as effective as increasing n-3 HUFA in lowering brain PL-AA and brain 2-AG+1AG.

Previous reports suggest that elevated intakes of LA during early development may be related to the development of obesity (38). An epidemiological report linked increased LA intake, especially in infant feeding, over the last 40 years to increased prevalence of obesity and postulated that AA induced elevations in 2-AG may have altered energy balance towards obesity (38). Consistent with this, we found strong ecological relationship between apparent consumption of soybean oil, shortening, and poultry, the major dietary sources of LA, and the rise in obesity in the United States during the 20th century. Data on the apparent consumption is robustly associated with adipose concentrations of short chain (r = 0.92) and long chain (r = 0.88) PUFA across 11 countries (39). We note that the shift away from physical labor occupations is likely to be a significant factor; however, the increasing prevalence of obesity is also found separately within physical and non-physical labor occupations (40). We recognize that simultaneous temporal changes in potential contributors to obesity risk are difficult to disentangle sufficiently enough to confirm causality. These ecological associations do not demonstrate that increasing LA caused increasing obesity in the United States during the 20th century. However, the results of the causal test of this inference in rodents are consistent with the interpretation that increasing dietary LA in human diets caused endocannabinoid hyperactivity and substantially contributed to increasing prevalence rates of obesity.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the Intramural Research program of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, NIH, the National Institute of Nutrition and Seafood Research (NIFES), Bergen, Norway, and the Research Council of Norway 186908/l10. The fish oil concentrate was provided by Axellus, Norway. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

See the ICME Conflict of Interest Forms for this article.

Footnotes

Supplementary material is linked to the online version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/oby

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- Di Marzo V, Goparaju SK, Wang L.et al. Leptin-regulated endocannabinoids are involved in maintaining food intake Nature 2001410822–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osei-Hyiaman D, DePetrillo M, Pacher P.et al. Endocannabinoid activation at hepatic CB1 receptors stimulates fatty acid synthesis and contributes to diet-induced obesity J Clin Invest 20051151298–1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagotto U, Marsicano G, Cota D, Lutz B, Pasquali R. The emerging role of the endocannabinoid system in endocrine regulation and energy balance. Endocr Rev. 2006;27:73–100. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen R, Kristensen PK, Bartels EM, Bliddal H, Astrup A. Efficacy and safety of the weight-loss drug rimonabant: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2007;370:1706–1713. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61721-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lands WE, Libelt B, Morris A.et al. Maintenance of lower proportions of (n - 6) eicosanoid precursors in phospholipids of human plasma in response to added dietary (n - 3) fatty acids Biochim Biophys Acta 19921180147–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Ueda N. Biology of endocannabinoid synthesis system. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2009;89:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasbalg TL, Hibbeln JR, Ramsden CE, Majchrzak SF, Rawlings RR. Changes in consumption of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids in the United States during the 20th century. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:950–962. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.006643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch J, Lees M, Sloane stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoerner AA, Gutzki FM, Batkai S.et al. Quantification of endocannabinoids in biological systems by chromatography and mass spectrometry: a comprehensive review from an analytical and biological perspective Biochim Biophys Acta 20111811706–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agren JJ, Julkunen A, Penttilä I. Rapid separation of serum lipids for fatty acid analysis by a single aminopropyl column. J Lipid Res. 1992;33:1871–1876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salem N, Jr, Reyzer M, Karanian J. Losses of arachidonic acid in rat liver after alcohol inhalation. Lipids. 1996;31 Suppl:S153–S156. doi: 10.1007/BF02637068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen JB, Petersen RK, Larsen BM.et al. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma bypasses the function of the retinoblastoma protein in adipocyte differentiation J Biol Chem 19992742386–2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen L, Petersen RK, Sørensen MB.et al. Adipocyte differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes is dependent on lipoxygenase activity during the initial stages of the differentiation process Biochem J 2003375539–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmchen LA, Henderson RM. Changes in the distribution of body mass index of white US men, 1890-2000. Ann Hum Biol. 2004;31:174–181. doi: 10.1080/03014460410001663434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999-2000. JAMA. 2002;288:1723–1727. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh NI, Pencina MJ, Wang TJ.et al. Increasing trends in incidence of overweight and obesity over 5 decades Am J Med 2007120242–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batetta B, Griinari M, Carta G.et al. Endocannabinoids may mediate the ability of (n-3) fatty acids to reduce ectopic fat and inflammatory mediators in obese Zucker rats J Nutr 20091391495–1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matias I, Petrosino S, Racioppi A.et al. Dysregulation of peripheral endocannabinoid levels in hyperglycemia and obesity: Effect of high fat diets Mol Cell Endocrinol 2008286S66–S78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piscitelli F, Carta G, Bisogno T.et al. Effect of dietary krill oil supplementation on the endocannabinoidome of metabolically relevant tissues from high-fat-fed mice Nutr Metab (Lond) 2011851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munakata M, Nishikawa M, Togashi N.et al. The nutrient formula containing eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid benefits the fatty acid status of patients receiving long-term enteral nutrition Tohoku J Exp Med 200921723–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak EM, Dyer RA, Innis SM. High dietary omega-6 fatty acids contribute to reduced docosahexaenoic acid in the developing brain and inhibit secondary neurite growth. Brain Res. 2008;1237:136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.07.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle LD, MacKinnon MJ, Innis SM. Formula 18:2(n-6) and 18:3(n-3) content and ratio influence long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in the developing piglet liver and central nervous system. J Nutr. 1994;124:289–298. doi: 10.1093/jn/124.2.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lands WE, Morris A, Libelt B. Quantitative effects of dietary polyunsaturated fats on the composition of fatty acids in rat tissues. Lipids. 1990;25:505–516. doi: 10.1007/BF02537156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourre JM, Piciotti M, Dumont O, Pascal G, Durand G. Dietary linoleic acid and polyunsaturated fatty acids in rat brain and other organs. Minimal requirements of linoleic acid. Lipids. 1990;25:465–472. doi: 10.1007/BF02538090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JO, Peters JC, Lin D.et al. Lipid accumulation and body fat distribution is influenced by type of dietary fat fed to rats Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 199317223–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Asti E, Long H, Tremblay-Mercier J.et al. Maternal dietary fat determines metabolic profile and the magnitude of endocannabinoid inhibition of the stress response in neonatal rat offspring Endocrinology 20101511685–1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osei-Hyiaman D, Depetrillo M, Harvey-White J.et al. Cocaine- and amphetamine-related transcript is involved in the orexigenic effect of endogenous anandamide Neuroendocrinology 200581273–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen L, Pedersen LM, Liaset B.et al. cAMP-dependent signaling regulates the adipogenic effect of n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids J Biol Chem 20082837196–7205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Miyazaki M, Ntambi JM. Dietary cholesterol opposes PUFA-mediated repression of the stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 gene by SREBP-1 independent mechanism. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:1750–1757. doi: 10.1194/jlr.m100433-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Takahashi M, Ezaki O. Fish oil feeding decreases mature sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP-1) by down-regulation of SREBP-1c mRNA in mouse liver. A possible mechanism for down-regulation of lipogenic enzyme mRNAs. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25892–25898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gary-Bobo M, Elachouri G, Scatton B.et al. The cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist rimonabant (SR141716) inhibits cell proliferation and increases markers of adipocyte maturation in cultured mouse 3T3 F442A preadipocytes Mol Pharmacol 200669471–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perwitz N, Fasshauer M, Klein J. Cannabinoid receptor signaling directly inhibits thermogenesis and alters expression of adiponectin and visfatin. Horm Metab Res. 2006;38:356–358. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-925401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Eon TM, Pierce KA, Roix JJ.et al. The role of adipocyte insulin resistance in the pathogenesis of obesity-related elevations in endocannabinoids Diabetes 2008571262–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger A, Crozier G, Bisogno T.et al. Anandamide and diet: inclusion of dietary arachidonate and docosahexaenoate leads to increased brain levels of the corresponding N-acylethanolamines in piglets Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001986402–6406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S, Doshi M, Hamazaki T. n-3 Polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) deficiency elevates and n-3 PUFA enrichment reduces brain 2-arachidonoylglycerol level in mice. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2003;69:51–59. doi: 10.1016/s0952-3278(03)00056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artmann A, Petersen G, Hellgren LI.et al. Influence of dietary fatty acids on endocannabinoid and N-acylethanolamine levels in rat brain, liver and small intestine Biochim Biophys Acta 20081781200–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V, Griinari M, Carta G.et al. Dietary krill oil increases docosahexaenoic acid and reduces 2-arachidonylglycerol but not N-acylethanolamine levels in the brain of obese Zucker rats Int Dairy J 201020231–235. [Google Scholar]

- Ailhaud G, Massiera F, Weill P.et al. Temporal changes in dietary fats: role of n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids in excessive adipose tissue development and relationship to obesity Prog Lipid Res 200645203–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrova S, Dimitrov P, Willett WC, Campos H. The global availability of n-3 fatty acids. Public Health Nutr. 2011. pp. 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Caban AJ, Lee DJ, Fleming LE.et al. Obesity in US workers: The National Health Interview Survey, 1986 to 2002 Am J Public Health 2005951614–1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.