Abstract

The proteome represents the identity, expression levels, interacting partners, and posttranslational modifications of proteins expressed within any given cell. Proteomic studies aim to census the quantitative and qualitative factors regulating the biological relationships of proteins acting in concert as functional cellular networks. In the field of endocrinology, proteomics has been of considerable value in determining the function and mechanism of action of endocrine signaling molecules in the cell membrane, cytoplasm, and nucleus and for the discovery of proteins as candidates for clinical biomarkers. The volume of data that can be generated by proteomics methodologies, up to gigabytes of data within a few hours, brings with it its own logistical hurdles and presents significant challenges to realizing the full potential of these datasets. In this minireview, we describe selected current proteomics methodologies and their application in basic and translational endocrinology before focusing on mass spectrometry as a model for current progress and challenges in data analysis, management, sharing, and integration.

The integration of computational technologies into biomedical science has catalyzed the development of myriad high-throughput experimental platforms and the birth of the 'omics age. Omics research encompasses global-scale investigations of cellular genomes, transcriptomes, epigenomes, proteomes, and metabolomes, in addition to disease states such as obesity, the so-called obesidome (1), and others. With the advent of these disciplines, experimentation has evolved from largely manual, hypothesis-driven approaches with modest metrics for data output to encompass rapid, automated or semi-automated surveys of cellular states that, in the case of genomic studies, can generate up to petabytes of data within a matter of hours.

The storage, transfer, analysis, and interpretation of 'omics datasets represent tremendous challenges requiring personnel with increasingly specialized skill sets that are distinct from those that have traditionally held sway in biomedical research. Although various bioinformatic working groups are working to develop and implement strategies to manage these issues (2), many problems accompanying 'omics-generated datasets currently exist for individuals at all levels of research, and particularly those at the bench. 1) Institutions may be overwhelmed by the rapid pace of technology development and often lack formal policies to efficiently support and oversee faculty or staff researchers participating in 'omics research (3). 2) Information technology personnel may not have cost-effective models in place for the storage, transmission, and management of large datasets generated by researchers who do not have tens of thousands of dollars to allocate toward storage and backup charges. 3) Core facilities frequently struggle with finding personnel with the necessary bioinformatics and biostatistics expertise for properly designing studies and analyzing the data. In addition, many laboratory information management systems are not readily scalable to support the 'omics datasets. 4) Scientists can struggle with the issue of how to interpret and integrate the primary, or even analyzed, data they receive from cores or private companies to synthesize information that can be communicated easily to the community. In addition, it is often not practical or feasible in traditional publications to convey all the findings from large datasets in any level of detail, requiring researchers to carefully select key results they describe within manuscripts. Important insights are therefore often not reported in papers and their abstracts, leading to the accumulation of valuable, but occult, data points. Although these data are nominally available in raw form in public repositories, deficits in annotation standards, deposition rates (4), and the development of easy-to-use analytic and searching tools render them in many cases effectively opaque to the community. Efforts to expose these occult data are ongoing (5, 6) (for a list of public protein resources, see Table 1). These logistical obstacles notwithstanding, the promise of 'omics methodologies is enormous, and the benefits for research that will accrue from their integration into systems-wide views of cell and tissue function are undeniable.

Table 1.

Selected public protein databases and knowledge bases

| Name | Features | Notes | URL (Ref.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BioGRID | Protein-protein and genetic interactions | Data from many different microorganisms and animals linked with GO terms | http://thebiogrid.org/ (116) |

| CORUM | Protein complex Function Cellular localization Composition |

Manually annotated mammalian protein complexes | http://bit.ly/IbHGqZ (117) |

| Entrez Protein | Sequence | Data from UniProtKB and PDB with nucleic to amino acid translations from GeneBank, RefSeq, and TPA | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein |

| HPRD | Protein-protein interaction Posttranslational modifications Cellular localization Disease association |

Standards-compliant, human-centric database based on experimental with tools for phosphorylation motif reports and signaling pathway information | http://www.hprd.org (118) |

| IMEx | Protein-protein interaction | Single source of nonredundant, manually curated data from DIP, IntAct, MINT, BioGRID, and other public databases; PSI-MI and other standards-compliant data downloads | http://www.imexconsortium.org/ (103) |

| InterPro | Structure Function Others |

Integrates protein family, structure, and function from multiple databases with GO terms and protein feature prediction algorithms | http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/ (119) |

| neXtProt | Sequence Structure Expression Cellular location Others |

Human data from UniProtKB/SWISS-PROT coupled with data from high-throughput studies, ENSEMBL, GO, etc. | http://www.nextprot.org/ (120) |

| Pfam | Sequence Structure Function |

Database of protein families and domains, driven by multiple sequence alignments and hidden Markov models; has protein-protein interaction prediction and other tools | http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk/ (121) |

| PMAP | Protease-specific data (class-specific database example) | Data sourced from MEROPS (REF), HPRD, and the literature with PathwayDB tool | http://www.proteolysis.org/proteases (122) |

| ProteomeXchange | Mass spectrometry experimental data | Single point of submission for MS data, feeding into PRIDE, PeptideAtlas, and Tranche | http://www.proteomexchange.org |

| UniProtKB | Sequence Structure Expression pattern Cellular location Posttranslational modifications Others |

SWISS-PROT is manually curated and annotated; TrEMBL is computationally analyzed and annotated | http://www.uniprot.org/ (123) |

| World-2DPage Constellation | 2D gel-based experimental data | MIAPE-compliant data repository and query portal | http://world-2dpage.expasy.org/ (123) |

Proteomics encompasses broad-scale surveys of protein sequence, structure and function, interaction partners, posttranslational modification (including phosphorylation, methylation, acetylation, glycosylation, etc.), localization, interactions, and complex formation in a cell, tissue, or organism. Although the human genome contains approximately 23,000 genes (7), alternative splicing events and posttranslational modifications combine to make the number of functionally distinct proteins orders of magnitude higher, with some possibly conservative estimates set at around 1,000,000 (8). Many online public databases have been developed to catalog these data and, in some cases, integrate them with gene, transcript, and other pertinent cellular information (Table 1). The end goal of proteomics research is to determine how proteins function in regulating biological processes as components of cell-type-specific networks, for applications ranging from biomarker discovery to assessments of drugs and small molecular inhibitors. In this review, we describe a variety of proteomics methodologies and selected illustrative examples of their application in basic and translational endocrinology and showcase mass spectrometry as a paradigm for current advances and challenges in data analysis, management, sharing, and integration.

Proteomics Methodologies

Many assays have been developed for the identification and quantitation of peptides and proteins and their interacting partners, including yeast two-hybrid, affinity purification, immunohistochemistry, and others. Although many of these techniques have been adapted into proteomics-scale applications, a discussion of all of these is beyond the scope of this review and we focus here instead upon a small number of popular categories of assays, namely protein arrays, two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis (2D-DIGE) and mass spectrometry (MS).

Protein arrays

Protein arrays are analogous to transcriptomic expression microarrays, which can simultaneously probe the abundance of tens of thousands of transcripts (9). These arrays allow for the multiplex identification of proteins of interest by subjecting a biological sample to a miniaturized array of up to thousands of distinct capture molecules (e.g. antibodies, affibodies, other proteins, peptides, DNA molecules, or aptamers) that have been spotted onto a slide to determine which substrates will be captured or bound. Many subcategories of protein arrays exist, including capture microarrays, reverse-phase protein arrays (RPPA), function-based protein microarrays, and others.

Capture arrays

Capture arrays are manufactured by spotting specific capture molecules on a chip surface and report upon protein binding affinities and expression levels between two samples, e.g. diseased vs. normal human tissues (10, 11). Multiple types of capture arrays have been developed, common among which are direct labeling and sandwich capture assays. Direct labeling requires that both experimental and control samples be labeled with a marker, such as a fluor, which allows for multiplex measurement by incorporating multiple markers in sample aliquots. This technique has its limitations, however: not all proteins in the samples will be uniformly labeled by the markers, labeling may interfere with the binding properties of the component proteins of interest, the background marker signal may be high, and marker cross-reactivity can result in false positives (12). Multiple distinct capture molecules may be used in parallel to alleviate these issues. Sandwich capture assays use two molecules, one adhered to the chip for trapping the protein and a second, labeled molecule to specifically mark proteins of interest. This method avoids some of the pitfalls of direct labeling described above in that it allows for determination of physiologically relevant protein levels (12, 13), although multiplex identification is more challenging. Capture libraries have been developed and, for nucleic acids trap molecules, in vitro selection experiments such as SELEX (systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment) can be performed to increase library complexity (14, 15). Label-free methods, such as surface plasmon resonance (reviewed in Ref. 16), are also available.

Reverse-phase protein arrays

RPPA are useful for multiplex detection in specimens of protein alterations, particularly for posttranslational modifications, and can inform upon the state of cellular pathways, such as altered phosphorylation signatures associated with disrupted signaling pathways in disease states (17–20). In contrast with capture arrays, in RPPA, the biological sample (or samples) is arrayed onto a chip, which is then probed with specific reagents to determine relative protein abundance (21, 22). Due to limitations arising from more abundant proteins interfering with detection of less abundant proteins, as well as false positives arising from cross-reacting detection reagents, these assays are typically more useful for determining the relative quantities of a small number of proteins.

Functional microarrays

Specific biochemical activities or interactions between proteins and other molecules can be determined using functional microarrays (23). These arrays require correctly folded, functional proteins to be printed onto a chip. Functional microarray chips must therefore be carefully designed and manufactured to protect the activity of what are often labile proteins. The production of sufficient yields of proteins of interest, their relative lack of stability, and behavioral changes induced by attaching proteins to the chip are three major challenges for these arrays. The development of assays that allow for in situ protein synthesis in a cell-free system, in which protein production occurs directly on the chip, have helped address these concerns. High-yield techniques include nucleic acid programmable protein arrays (NAPPA) (24, 25), DNA array to protein array (DAPA) (26–28), protein in situ array (PISA) (28, 29), the Escherichia coli protein Tus with its Ter 20-bp DNA sequence capture reagent (TUS-TER) (30, 31), and others (reviewed in Ref. 32).

Two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis provides for the separation of nondigested proteins within a biological sample based either upon apparent molecular mass (by gel electrophoresis) or by charge (via isoelectric focusing) to determine protein abundance and to identify isoforms and posttranslational modifications (33). Fluorescent 2D-DIGE was developed to obviate time-consuming gel staining and analysis to remove gel image artifacts and, more importantly, to increase the level of reproducibility among experimental replicate gels by removing the need to run different sample types (e.g. treated vs. untreated cells) on separate gels. 2D-DIGE methodologies allow the simultaneous surveying of up to three samples labeled with fluorescent cyanine-based dyes on the same gel, typically with internal protein standards (34–36). By exploiting differences in excitation wavelength of the three dyes, proteins and their spot patterns on the gel within each sample can be separately visualized for cross-comparison. Mechanisms to increase detection of low-abundance proteins include use of sensitive dyes on the DIGE gel, coupling of 2D-DIGE with Western blots in which specific antibodies are applied to a gel blot and the blot image compared with that from the DIGE, and prefractionation enrichment procedures (37, 38).

Mass spectrometry

One of the most popular high-throughput methodologies in proteomics, MS, measures the mass-to-charge ratio of charged particles to determine the mass and elemental composition in complex mixtures of either individual proteins or the relative quantity of proteins of interest (39). Unlike most other proteomics methodologies, MS runs can output gigabytes of data in several hours (40). Due to the complex nature of MS experiments and large volume of raw data output, it is critical that statistically appropriate study design plans are created and followed during experimental execution (41). Broadly speaking, there are two types of MS experiments: top-down experiments, in which whole proteins are run through the instrument, and bottom-up experiments, in which proteins within a sample of interest are digested with proteases before the MS run, thereby availing of the greater sensitivity of MS instruments for peptides over proteins. The resulting peptide mixtures may then be separated before MS using liquid chromatographic (LC), gas chromatographic, or ion mobility spectrometry methods. To allow for quantification of identified proteins, samples can be isotopically labeled via methods such as stable isotope labeling by amino acids (SILAC) (42), isotype-coded affinity tag (ICAT) (43, 44), isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantification (iTRAQ) (45), and mass tags for relative and absolute quantification (mTRAQ), (46), among others. Multiple different MS techniques can be coupled together in distinct experimental workflows, but these are too numerous to cover in depth due to space limitations. In general, MS workflows consist of sample (intact or digested protein) loading, vaporization, ionization [e.g. electrospray ionization (ESI) (47) or matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) (48, 49)], separation of ionized sample by mass-to-charge ratio, detection in an MS instrument, and generation of spectra as output. Tandem MS (MS/MS) instruments can perform multiple rounds of spectrometry, allowing for high specificity in protein identification and quantitation.

Proteomics Approaches in Basic Endocrinology

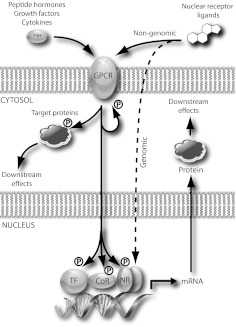

Although transcriptomic approaches have been widely used to characterize regulation of gene expression in endocrinology, they are by their nature limited to reporting on regulation of gene expression at the mRNA level. In tandem with these studies, over the past decade, there has been a growing appreciation of the role of processes at the protein level in driving responses to hormones in target cells. The increasing accessibility of global proteomics tools has given rise to a growing number of discovery-driven (or hypothesis-generating) studies that have generated datasets on cellular-scale processes in endocrinology. Figure 1 illustrates the variety of events in molecular endocrinology that are subject to proteomic interrogation, including the formation of protein complexes by hormone receptors as well as hormone-dependent regulation of cellular proteins and phosphoproteins. We describe next selected examples of the applications of various proteomics technologies to the investigation of these processes.

Fig. 1.

Proteomics elucidates function and mechanism in molecular endocrinology. The schematic shows events on which proteomics reports in general functional models of G protein-coupled receptor and NR signaling. The binding of a variety of peptide ligands to G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) induces recruitment of intracellular interacting partner proteins, touching off a variety of kinase cascades with functional endpoints in the cytoplasm (phosphorylated target protein) and nucleus. Nuclear targets of kinase cascades include transcription factors (TF), NR, and coregulators (CoR), which collectively modulate target gene expression and de novo protein synthesis. NR ligands bind directly to NR (the classic genomic model), inducing the recruitment of coregulators and modulating expression of target genes. Certain NR ligands have also been reported to elicit rapid cellular effects via cross talk with cellular kinase cascades (the nongenomic model). Phosphorylation events upon which phosphoproteomics reports are indicated.

Proteomics in nuclear receptor (NR) signaling

In pioneering studies in the Roeder and Freedman laboratories, the ligand-binding domains of thyroid hormone receptor-α (50) and later the vitamin D3 receptor (51) were used as baits to isolate and define the orthologous thyroid receptor-associated proteins and vitamin D3 receptor-interacting proteins complexes, respectively. After these initial studies, a number of groups have characterized interacting complexes for other members of the NR superfamily. LC/MS (52, 53) and bottom-up 2D-PAGE (54) analysis has since been used to characterize estrogen receptor-α (ERα)-interacting proteomes in MCF-7 cells. A systematic affinity purification/mass spectrometry screen for interacting proteins of characterized NR coregulators in HeLa cells identified an extensive network of interactions and classified NR coregulators based on the stability of the cellular interaction networks they establish (55). Other studies have used proteomic surveillance as a surrogate for regulation of gene expression by physiological NR ligands, including the ubiquitous 17β-estradiol action in MCF-7 cells (56, 57) as well as a study of the thyroid hormone-regulated hepatic secretome (58). The number of induced genes extrapolated from some of these studies is considerably smaller than might have been anticipated from transcriptomic studies. This discrepancy may be attributable to mismatching protein identifiers and mRNA probe sets and differences in inter-laboratory techniques and experimental conditions as well as differences in RNA and protein degradation (59). Since the discovery that dopamine activated the human progesterone receptor through cellular kinase-mediated pathways (60–62), posttranslational modification of NR and coregulators has been accepted as a fundamental component of their mode of action. Before the advent of global proteomics techniques, posttranslational modifications analysis was limited to painstaking incremental characterization of individual residues, but LC-MS analysis has greatly facilitated the characterization of these residues, most notably in the case of 17β-estradiol-induced posttranslational modifications of ERα (63). Finally, a variety of phosphoproteomic studies have emerged that have profiled ligand-induced variations in cellular phosphoregulomes in response to NR ligands, including the 17β-estradiol-ER signaling axis (64, 65) and retinoic acid in neuroblastoma cells (66).

Proteomics in G protein-coupled receptor signaling

G protein-coupled receptors mediate signal transduction in a variety of endocrine, cytokine, and growth factor pathways, and their ligand-activated assembly of intracellular protein complexes and the ensuing kinase cascade-mediated phosphorylation events have been well characterized (reviewed in Ref. 67). Affinity purification using purified forms of membrane receptors coupled to MS has been used to characterize specific cellular proteins that associate with the receptors, such as in the case of the activin type II receptor, which was shown to be a receptor for several TGFβ family members as well as members of the bone morphogenetic protein family (68). Analogous to NR, recruitment of transcriptional coregulators by nuclear membrane receptor-activated transcription factors has also been profiled using proteomics strategies. For example, multidimensional protein identification technology (MUDPIT), which couples 2D chromatographic separation with MS, has been used to demonstrate the presence in the Ccaat-enhancer-binding protein beta complex of members of the sucrose nonfermentable family, components of the APOBEC1 complementation factor and chromatin accessibility complex chromatin remodeling complexes (69). Proteomics-based profiling of hormone target tissues has been used to interrogate global fluctuations in cellular protein levels in many different tissues, including the effect of the pituitary gonadotropins FSH and LH in the ovary (70) and that of insulin in the pancreatic β-cell (71) as well as bone responses to PTH (72). Phosphoproteomic analysis is particularly well suited to profile cellular changes in response to peptide hormone signaling, which involves profound, rapid fluctuations in the phosphorylation status of many proteins. For example, insulin-responsive fluctuations in the phosphoregulome of hepatic (73) and brown adipose tissue (74) have been reported, as has renal phosphoprotein regulation by vasopressin, glucagon, PTH, and calcitonin (75, 76).

Proteomics Approaches in Translational Endocrinology

In the preproteomic era, hypothesis-driven identification of clinical biomarkers relied upon an a priori rationale for pursuing a specific candidate marker. Translational proteomics approaches are based on the ability of high-throughput methodologies to simultaneously and sensitively interrogate the entire complement of proteins (as well as their splice and posttranslational variants) in a given disease sample compared with a normal control sample. The myriad genetic and environmental factors that influence the level of a protein in a biological sample present considerable challenges to proteomic approaches to biomarker development. We focus here upon a number of studies that have reported the identification of promising candidates in diabetes and its associated tissue-specific disease states.

Type 2 diabetes has its origin in the derangement of metabolic pathways regulating the consumption, use, and storage of carbohydrates and lipids and is associated with a variety of peripheral tissue pathological endpoints. In humans, diabetic retinopathy secondary to hyperglycemic damage to retinal blood vessels is one of the most common manifestations of diabetes. A variety of studies variously using 2D-LC-MS/MS (77), ESI-Quadrupole Time of Flight MS/MS (78), and iTRAQ/ESI-MS/MS (79) approaches have identified the extracellular protein lipocalin-1 as differentially expressed in the lacrimal fluid of diabetic patients relative to healthy controls. Thingholm et al. (80) used iTRAQ to compare proteomic signatures of skeletal muscle samples between nondiabetic and diabetic subjects and identified lower levels of adenosine deaminase in the diabetic samples. Diabetic nephropathy is a well-characterized diabetic complication and a common precursor of end-stage renal disease, for which animal models have been widely used in proteomic studies. Q-STAR LC-MS/MS-based comparison of glomeruli from spontaneous type 2 diabetes or normal rats identified Sorbin and SH3 domain-containing protein 2, an actin cytoskeleton-associated protein involved in the formation of stress fibers, as a novel etiological factor and potential biomarker in diabetic nephropathy (81). Streptozotocin treatment of rats followed by perfusion with a reactive ester derivative of biotin and subsequent affinity purification/MS analysis identified elevated levels of the ectoenzyme pantetheinase vanin-1 and uromodulin in the kidneys of the streptozotocin-treated rats. Subsequent validation of this observation using urine samples from diabetic patients identified these proteins as markers for type 1 diabetic macroalbuminuria and type 1 diabetes, respectively, suggesting their use as potential clinical markers in type 1 diabetes (82).

MS: A Case Study in Proteomics

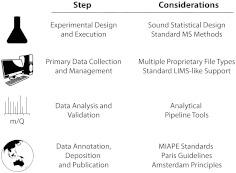

MS has been used to considerable effect in molecular endocrinology, owing to its ability to generate a large volume of data quickly, the free availability of analysis tools, and its ready adaptability to metabolomics. As such, it stands as an instructive paradigm for existing and future proteomics techniques that also generate vast quantities of data. Moreover, the obstacles surrounding data management, analysis, sharing, and integration are shared among other 'omics domains. Here we provide an overview of the current progress and challenges for data management, analysis, sharing, access, and integration (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Available standards for the lifecycle of MS experimentation. From initial experimental design to the publication of MS results (steps, left), standard protocols, analysis pipelines, data structures, and guidelines/recommendations for publishers (considerations, right) have been developed, although the relative maturity of each may differ. LIMS, Laboratory information management systems; m/Q, mass-to-charge ratio.

Data management and analysis

A variety of MS instruments manufactured by different companies generate raw data as flat files in proprietary formats, such as ABI/Sciex WIFF, Bruker FID/YEP/BAF, Thermo Scientific RAW, and Waters MassLynx file types. As previously alluded to, core facilities or investigator groups frequently struggle with managing primary data and often have in place what are at best irregular data backup strategies (83). Certain laboratory information management systems packages provide support for backups and early analytic steps, but many offer only some combination of equipment scheduling, service request, billing, instrument monitoring, and limited experimental data management. Open source tools have been developed recently to automate raw data backup from the instrument to file servers (83) and to store, track, and link annotations on biological samples with their associated experimental data in a proteomics standards-compliant fashion (e.g. PRODIS for 2D-PAGE, LC, and MS data) (84).

Typical MS analytical workflows involve multiple steps (reviewed in Ref. 85) such as the conversion of proprietary primary data outputs to standardized, open data formats for processing (86), identification of peptides and proteins (87), and where applicable, quantification of individual species (Fig. 1) (88). Although several analytic tools may be used in tandem to create a custom analytic pipeline, several off-the-shelf open source software tool suites currently exist, including those described in Table 2. These software suites typically include the facility to convert proprietary vendor files to the open format Institute of Systems Biology's standard data structures, mzXML (40) and/or the newer mzML (89), which are types of XML files that enforce rules on encoding data in a way that makes them readable to both humans and software. The suites then match uninterpreted spectra, mzML, and/or mzXML data to known peptide sequences via one or more spectral search engines (see Table 3 for examples). Alternatively, in conjunction with searches of known sequences, some software analysis suites make provision for hypothetical spectral library searches by including engines such as SpectraST (90). Finally, many of these suites allow end users to perform statistical data validation such as false discovery rates and probabilities, quantification for isotopic or isobaric labeling experiments, and quality assurance (Table 2).

Table 2.

Selected MS data analysis pipeline suites

| Name | Description | URL (Ref.) |

|---|---|---|

| Central Proteomics Facilities Pipeline (CPFP) | Suite for labeled or label-free quantitation in core proteomics facilities | http://cpfp.sourceforge.net (124) |

| LabKey Server | Suite to identify and quantify proteins using its Computational Proteomics System (CPAS) and integrating with a variety of search engines and TPP components | http://labkey.com (125) |

| MaxQuant | Suite for high-resolution labeled or label-free MS data with Andromeda search engine and a Viewer for visualization | http://maxquant.org (68) |

| Open Comprehensive Analysis Pipeline (OCAP) | Suite for iTRAQ quantitative MS data analysis incorporating a variety of search engines and visualization components | http://code.google.com/p/ocap (126) |

| PhoMSVal | Suite for MS/MS phosphopeptide data | http://csbi.itdk.helsinki.fi/phomsval (127) |

| The OpenMS Proteomic Pipeline (TOPP) | Suite for creating custom analytic pipelines of HPLC/MS data | http://open-ms.sourcefourge.net/topp/ (128) |

| TPP (Trans-Proteomic Pipeline) | Suite for validation, quantitation, and visualization of MS and MS/MS data, incorporating a variety of search engines | http://sourceforge.net/projects/sashimi (129) with a guided tour (130) |

Table 3.

Selected MS/MS spectral search engines

| Name | Description | URL (Ref.) |

|---|---|---|

| MASCOT | Identify proteins via peptide mass fingerprint, sequence queries, and MS/MS ion searches from several public peptide/protein and contaminant databases | http://www.matrixscience.com (131) |

| Open MS Search Algorithm (OMSSA) | Searches known sequence databases and assigns probability scores with a BLAST algorithm | http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omssa/ (132) |

| Phenyx | Searches public databases and other search engines included here for validation as well as other extra-search functionalities | http://genebio.com/products/phenyx/ (133) |

| ProbID | Component of TPP that searches protein sequence databases | http://tools.proteomecenter.org/wiki/index.php?title=Software:ProbID (134) |

| SEQUEST | Original and still popular engine for searching sequence databases now distributed by Thermo | http://proteomicsresource.washington.edu/sequest.php (135) |

| X!Tandem | Searches against sequence databases and calculates statistical confidence to sequence assignments and maps these assignments to known proteins sequences | http://www.thegpm.org/tandem (136) |

| MR-X!Tandem | Cloud-based (e.g. located on the internet) version of X!Tandem that runs multiple searches in parallel on different servers, making it useful for very large peptide searches | http://insilicos.com/products/mr-tandem (137) |

Data sharing

Several different parallel international efforts are ongoing to develop and implement standards for proteomics data to facilitate data sharing and reuse. Standard metadata (e.g. data, such as MS instrument type or experimental conditions, that describe the actual MS or MS/MS dataset), data terms, and data structures have been developed by the Human Proteome Organization (HUPO) and are being adopted by the community at large. Similar to those developed for gene expression microarray submissions, major progress has been made in creating guidelines for proteomics publications by the editors of Molecular and Cellular Proteomics (MCP) and their colleagues, including adoption of HUPO data standards, namely the Paris Guidelines (91) and Amsterdam Principles (92).

Development of data standards

HUPO was formed in 2001 with the mission of promoting proteomics research by fostering collaborations through training (93), outreach (e.g. see Refs. 94 and 95) and the development and implementation of standards for proteomics research. HUPO has launched more than a dozen proteomics initiatives, many of which are centered around specific human tissues such as the kidney, liver, and brain as well as model organisms [initiative on Model Organism Proteomes (iMOP)] (96). Its Proteomics Standards Initiative (PSI) was tasked with the development of data representation standards that could be adopted by analytical tool developers, public databases, and vendors to facilitate meaningful data deposition, sharing, and use by researchers (97, 98). HUPO-PSI has achieved a number of landmarks in the establishment of parameters for proteomics research.

Annotation guidelines

These include minimal information about a proteomics experiment (MIAPE), similar to MIAME for gene expression microarray experiments (99), MIMIx for reporting a molecular interaction experiment (100), and others. MIAPE and MIMIx are useful in that proteomics data repositories complying with these standards can mandate a minimal set of annotations that must accompany any data deposition, comparable with gene expression microarray data in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO).

Standard data structures

Controlled vocabularies restrict options for annotations to only specific, authorized values (e.g. similar to a drop-down menu in a web page) to establish uniform descriptions of a protein or other biological entity and to facilitate data sharing. HUPO-PSI most recently created mzML, a format that implements a controlled vocabulary for protein and peptide identification as well as posttranslational modifications. The working group has also created other XML standards for molecular interactions and protein separation.

Mechanisms for data interchange between popular proteomics databases

The HUPO-PSI standards are being adopted by vendors (e.g. Applied Biosystems, Bruker Daltonics, and Waters Corp.) and other public web-based resource providers (Cytoscape, HPRD, IntAct, ProteomeCommons.org, etc.) (101). As a complement to the MCP and HUPO-PSI efforts, the National Cancer Institute and proteomics community has also developed guidelines to promote deposition of, and open access to, proteomic data in central public repositories (92, 102). Moreover, the International Molecular Exchange (IMEx) Consortium, a network of major public databases including many of those listed in Table 1, are creating protocols and procedures for data curation rules, policies on which annotations are necessary to fully describe protein-protein interactions and providing guidelines so that data from partner sites is available in a standardized format (103–105). Continued adoption of international standards efforts such as these should facilitate increased meaningful data exchange among public protein databases, data repositories, and researchers.

Proteomic experimental dataset repositories

The development of repositories for processed proteomic data and metadata, each with their own unique focus, has made possible the sharing of data by the proteomics research community. These repositories include PeptideAtlas (106), Proteomics Identifications (PRIDE) database (107), and Tranche, a component of the Proteome Commons (108). PeptideAtlas allows for data reanalysis and validation via a standardized Trans Proteomics Pipeline analytic workflow (Table 2) of raw MS/MS data. The processed data are then used to annotate genomic sequences and are exposed to the community through visualization and query tools. PRIDE provides a centralized, standards-compliant public repository that uses a variety of cross-referenced identifiers (UniProt, IPI, ENSEMBL, RefSeq, and NCBI Entrez gene identifiers) and the option to search for data by Gene Ontology (GO) terms, Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) diseases, species, tissues, and cell types. Tranche provides free password-encrypted storage of datasets, such that these datasets can be deposited before publication, shared only with desired parties (e.g. collaborators) or shared freely with the public upon publication under certain user-specified licensing conditions (108). Another unique factor of Tranche is that it is a distributed repository, meaning that datasets are duplicated across different servers such that any one server can crash without irreversible loss of data. This strategy allows the repository to operate without limiting the number or size of files that investigators may deposit and helps keep costs low by allowing the use of cheaper consumer-grade servers, thereby reducing the need for expensive enterprise-grade hardware while effectively protecting against data loss. An international consortium, the ProteomeXchange, aspires to serve as a single point of MS data submission for PeptideAtlas, PRIDE, and Tranche to facilitate data exchange among major proteomics dataset repositories (108) and to create universal accession numbers that are used by all participating databases. As a measure of its success, the HUPO Plasma Proteome Project has adopted ProteomeXchange policies for the types of data and metadata that must be submitted with experiments as well as the standards implemented therein (109).

Data access

Although the work of MCP, HUPO, and ProteomeXchange is a large step in the right direction, it does not guarantee the free accessibility, exchange, and integration of proteomic datasets. Incentives must be developed for scientists to adopt existing standards, fully annotate their data, and deposit them in a public repository. Models such as that of the Tranche repository are particularly attractive because they allow the investigators who generated the data to decide when to share them more broadly (e.g. after a manuscript is published) and under what terms such sharing may take place. The National Institutes of Health Direct Working Group on Data and Informatics recently issued a Request for Information for gathering community feedback on the issues such as incentivization, support, and standards (RFI NOT-OD-12-032). In addition to professional rewards, it is incumbent upon major journals and funding agencies to require investigators to deposit data in public repositories as a condition of publication or grant renewals. Some journals have already adopted the Paris Guidelines or some variant thereof (110, 111). Validation of deposition is an arduous task for any group, and it will be important for repositories, journals and funding agencies to collaborate to develop meaningful standards and automated processes for this effort.

Data integration and conclusions

Proteomics encompasses a powerful set of technologies but reports on only one component of cellular signaling pathways and their downstream biological effects. For example, identifying the transcriptional output of a given gene requires the use of transcriptomic technologies. Moreover, regulation of the specific activity of cellular enzymes and flux in cellular metabolites in response to a given signal are the province of metabolomic data platforms. Accordingly, there is a growing appreciation in the research community of the need to apply multiple 'omics approaches to a specific biological question in ways that can afford a broader perspective on the biological outputs of signal transduction pathways. One of the key challenges facing the field of biological informatics is the integrative management of these heterogeneous data types and formats and their distribution to the community through intuitive user interfaces that can allow them to carry out meaningful hypothesis generation and validation.

The obstacles to integration of primary proteomics datasets, even in the absence of data from other types of 'omics studies, are myriad, including the existence of multiple proprietary and nonproprietary file types, the dearth of standards-compliant data repositories, and the lack of incentives to encourage data deposition. Myriad reports have described difficulty in sophisticated, direct comparisons of transcriptomic and proteomic data (112), although at least one study noted significantly improved correlation when comparing expression of individual exons in splice variants to protein isoforms (113). Linkage of analyzed data on proteins of interest from experiments within a model system, however, is more feasible if the data share common gene or protein and species identifiers. Many scientists carry out this work on a small scale with their own data, and publicly available bioinformatics websites such as our Nuclear Receptor Signaling Atlas (NURSA) web resource (www.nursa.org) compile data on a broader scale, integrating many different datasets from the literature or public repositories and data from public reference databases. This larger-scale integration is generally labor intensive, requiring the identification of relevant data in the literature and/or public data repositories; extraction, curation, and annotation of data; and linkage around common biological identifiers. Work thus far has largely centered on integration of hundreds of transcriptomic datasets, but proteomics data have also been incorporated with protein annotations. NURSA team members, for example, recently used reciprocal immunoprecipitation/MS analysis to identify all approximately 9000 proteins expressed within a HeLa cell and the relative expression levels of these proteins alone and in complexes with other proteins that nucleate around coregulators (55). NURSA web resource members annotated the protein complex and quantification information with publication data, functional domain, other protein, organism, phenotype, and other information linked through standard identifiers (e.g. Entrez gene identifiers from the dataset were mapped to UniProt protein identifiers) from reference databases such as GenBank, InterPro, Pfam, Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, and others. This work generally requires at least some knowledge of familiarity with computer programming and reference databases.

Even standard, curated reference protein databases face challenges in extracting data and annotating in a consistent way. For example, in a comparison of nine major protein-protein interaction databases, Turinsky et al. (114) quantified the degree to which data from the same publication that was cited in databases agreed and found that any two of the databases are fully aligned for only 42% of interactions and 62% of curated proteins. The discrepancies were largely due to an inability to easily map protein isoforms and interacting partners to standard gene or protein identifiers. This issue is related in part to differences in how each database represented curated protein complexes, such that the researchers could not readily interconvert between one database's representation to a second and also to some true discrepancies in what protein data were curated for a given publication across the databases. Another important confounding factor was differences in how experiments were annotated for organism, because some databases recorded interactions only in the organism from which the proteins were extracted, whereas others also extrapolated the interactions to orthologs that share functional domains and/or amino acid sequences. Issues such as these are common to large-scale biological curation efforts and serve to highlight the opportunities for adoption of controlled vocabularies for gene, canonical protein, and protein isoform complex identifiers, coupled with standard use of universal ontologies for species, tissue, cell line, and other biological entity names to help alleviate them.

The challenges confronting proteomics research are shared by other 'omics, and collectively, these greatly compound the complexity of efforts to integrate heterogeneous 'omics data types (115). With the continued adoption and implementation of standards for data structure, experimental annotation, and data management, however, the collective promise of endocrinomics is tremendous. Although this promise must be tempered by consideration of the issues we have outlined in this review, proteomics and other 'omics can only catalyze the rate of discovery in basic and translational endocrinology in the years to come.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by U19 DK06234 (to L.B.B. and N.J.M.) and P30 CA125123 (to L.B.B.).

Disclosure Summary: L.B.B. and N.J.M. have nothing to declare.

Footnotes

- 2D-DIGE

- Two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis

- ERα

- estrogen receptor-α

- ESI

- electrospray ionization

- HUPO

- Human Proteome Organization

- iTRAQ

- isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantification

- LC

- liquid chromatography

- MCP

- Molecular and Cellular Proteomics

- MIAPE

- minimal information about a proteomics experiment

- MS

- mass spectrometry

- NR

- nuclear receptor

- NURSA

- Nuclear Receptor Signaling Atlas

- PRIDE

- Proteomics Identifications

- PSI

- Proteomics Standards Initiative

- RPPA

- reverse-phase protein array.

References

- 1. Pardo M, Roca-Rivada A, Seoane LM, Casanueva FF. 2012. Obesidomics: contribution of adipose tissue secretome analysis to obesity research. Endocrine 41:374–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cochrane G, Akhtar R, Bonfield J, Bower L, Demiralp F, Faruque N, Gibson R, Hoad G, Hubbard T, Hunter C, Jang M, Juhos S, Leinonen R, Leonard S, Lin Q, Lopez R, Lorenc D, McWilliam H, Mukherjee G, Plaister S, Radhakrishnan R, Robinson S, Sobhany S, Hoopen PT, Vaughan R, Zalunin V, Birney E. 2009. Petabyte-scale innovations at the European Nucleotide Archive. Nucleic Acids Res 37:D19–D25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Institute of Medicine 2012. Evolution of translational omics: lessons learned and the path forward. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ochsner SA, Steffen DL, Stoeckert CJ, Jr, McKenna NJ. 2008. Much room for improvement in deposition rates of expression microarray datasets. Nat Methods 5:991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rhodes DR, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Mahavisno V, Varambally R, Yu J, Briggs BB, Barrette TR, Anstet MJ, Kincead-Beal C, Kulkarni P, Varambally S, Ghosh D, Chinnaiyan AM. 2007. Oncomine 3.0: genes, pathways, and networks in a collection of 18,000 cancer gene expression profiles. Neoplasia 9:166–180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ochsner SA, Watkins C, McOwiti A, Dehart M, Darlington Y, Xu X, Cooney AJ, Steffen D, Becnel LB, McKenna NJ. 10 July 2012. Transcriptomine, a web resource for mining nuclear receptor signaling transcriptomes. Physiol Genomics 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. James P. 1997. Protein identification in the post-genome era: the rapid rise of proteomics. Q Rev Biophys 30:279–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dettmer K, Aronov PA, Hammock BD. 2007. Mass spectrometry-based metabolomics. Mass Spectrom Rev 26:51–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schena M, Shalon D, Davis RW, Brown PO. 1995. Quantitative monitoring of gene expression patterns with a complementary DNA microarray. Science 270:467–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sreekumar A, Nyati MK, Varambally S, Barrette TR, Ghosh D, Lawrence TS, Chinnaiyan AM. 2001. Profiling of cancer cells using protein microarrays: discovery of novel radiation-regulated proteins. Cancer Res 61:7585–7593 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Haab BB, Dunham MJ, Brown PO. 2001. Protein microarrays for highly parallel detection and quantitation of specific proteins and antibodies in complex solutions. Genome Biol 2:RESEARCH0004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moody MD, Van Arsdell SW, Murphy KP, Orencole SF, Burns C. 2001. Array-based ELISAs for high-throughput analysis of human cytokines. Biotechniques 31:186–190, 192–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mendoza LG, McQuary P, Mongan A, Gangadharan R, Brignac S, Eggers M. 1999. High-throughput microarray-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Biotechniques 27:778–780, 782,–786, 788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brody EN, Gold L. 2000. Aptamers as therapeutic and diagnostic agents. J Biotechnol 74:5–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Robertson MP, Ellington AD. 2001. In vitro selection of nucleoprotein enzymes. Nat Biotechnol 19:650–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. de Mol NJ. 2012. Surface plasmon resonance for proteomics. Methods Mol Biol 800:33–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Improta G, Zupa A, Fillmore H, Deng J, Aieta M, Musto P, Liotta LA, Broaddus W, Petricoin EF, 3rd, Wulfkuhle JD. 2011. Protein pathway activation mapping of brain metastasis from lung and breast cancers reveals organ type specific drug target activation. J Proteome Res 10:3089–3097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Berg D, Wolff C, Malinowsky K, Tran K, Walch A, Bronger H, Schuster T, Höfler H, Becker KF. 2012. Profiling signalling pathways in formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded breast cancer tissues reveals cross-talk between EGFR, HER2, HER3 and uPAR. J Cell Physiol 227:204–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tibes R, Qiu Y, Lu Y, Hennessy B, Andreeff M, Mills GB, Kornblau SM. 2006. Reverse phase protein array: validation of a novel proteomic technology and utility for analysis of primary leukemia specimens and hematopoietic stem cells. Mol Cancer Ther 5:2512–2521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Speer R, Wulfkuhle JD, Liotta LA, Petricoin EF., 3rd 2005. Reverse-phase protein microarrays for tissue-based analysis. Curr Opin Mol Ther 7:240–245 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Charboneau L, Tory H, Scott H, Chen T, Winters M, Petricoin EF, 3rd, Liotta LA, Paweletz CP. 2002. Utility of reverse phase protein arrays: applications to signalling pathways and human body arrays. Brief Funct Genomic Proteomic 1:305–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nishizuka S, Charboneau L, Young L, Major S, Reinhold WC, Waltham M, Kouros-Mehr H, Bussey KJ, Lee JK, Espina V, Munson PJ, Petricoin E, 3rd, Liotta LA, Weinstein JN. 2003. Proteomic profiling of the NCI-60 cancer cell lines using new high-density reverse-phase lysate microarrays. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:14229–14234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hall DA, Zhu H, Zhu X, Royce T, Gerstein M, Snyder M. 2004. Regulation of gene expression by a metabolic enzyme. Science 306:482–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ramachandran N, Hainsworth E, Bhullar B, Eisenstein S, Rosen B, Lau AY, Walter JC, LaBaer J. 2004. Self-assembling protein microarrays. Science 305:86–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ramachandran N, Raphael JV, Hainsworth E, Demirkan G, Fuentes MG, Rolfs A, Hu Y, LaBaer J. 2008. Next-generation high-density self-assembling functional protein arrays. Nat Methods 5:535–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. He M, Stoevesandt O, Palmer EA, Khan F, Ericsson O, Taussig MJ. 2008. Printing protein arrays from DNA arrays. Nat Methods 5:175–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stoevesandt O, Vetter M, Kastelic D, Palmer EA, He M, Taussig MJ. 2011. Cell free expression put on the spot: advances in repeatable protein arraying from DNA (DAPA). N Biotechnol 28:282–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. He M, Stoevesandt O. 2010. In situ biosynthesis of peptide arrays. Methods Mol Biol 615:345–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. He M, Taussig MJ. 2001. Single step generation of protein arrays from DNA by cell-free expression and in situ immobilisation (PISA method). Nucleic Acids Res 29:E73–E73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sitaraman K, Chatterjee DK. 2011. Protein-protein interactions: an application of Tus-Ter mediated protein microarray system. Methods Mol Biol 723:185–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chatterjee DK, Sitaraman K, Baptista C, Hartley J, Hill TM, Munroe DJ. 2008. Protein microarray on-demand: a novel protein microarray system. PLoS One 3:e3265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nand A, Gautam A, Pérez JB, Merino A, Zhu J. 2012. Emerging technology of in situ cell free expression protein microarrays. Protein Cell 3:84–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Görg A, Weiss W, Dunn MJ. 2004. Current two-dimensional electrophoresis technology for proteomics. Proteomics 4:3665–3685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Viswanathan S, Unlü M, Minden JS. 2006. Two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis. Nat Protoc 1:1351–1358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Marouga R, David S, Hawkins E. 2005. The development of the DIGE system: 2D fluorescence difference gel analysis technology. Anal Bioanal Chem 382:669–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Alban A, David SO, Bjorkesten L, Andersson C, Sloge E, Lewis S, Currie I. 2003. A novel experimental design for comparative two-dimensional gel analysis: two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis incorporating a pooled internal standard. Proteomics 3:36–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kosako H, Yamaguchi N, Aranami C, Ushiyama M, Kose S, Imamoto N, Taniguchi H, Nishida E, Hattori S. 2009. Phosphoproteomics reveals new ERK MAP kinase targets and links ERK to nucleoporin-mediated nuclear transport. Nat Struct Mol Biol 16:1026–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dubrovska A, Souchelnytskyi S. 2005. Efficient enrichment of intact phosphorylated proteins by modified immobilized metal-affinity chromatography. Proteomics 5:4678–4683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Aebersold R, Mann M. 2003. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Nature 422:198–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pedrioli PG, Eng JK, Hubley R, Vogelzang M, Deutsch EW, Raught B, Pratt B, Nilsson E, Angeletti RH, Apweiler R, Cheung K, Costello CE, Hermjakob H, Huang S, Julian RK, Kapp E, McComb ME, Oliver SG, Omenn G, Paton NW, Simpson R, Smith R, Taylor CF, Zhu W, Aebersold R. 2004. A common open representation of mass spectrometry data and its application to proteomics research. Nat Biotechnol 22:1459–1466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Oberg AL, Vitek O. 2009. Statistical design of quantitative mass spectrometry-based proteomic experiments. J Proteome Res 8:2144–2156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ong SE, Mann M. 2007. Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture for quantitative proteomics. Methods Mol Biol 359:37–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. von Haller PD, Yi E, Donohoe S, Vaughn K, Keller A, Nesvizhskii AI, Eng J, Li XJ, Goodlett DR, Aebersold R, Watts JD. 2003. The application of new software tools to quantitative protein profiling via isotope-coded affinity tag (ICAT) and tandem mass spectrometry. II. Evaluation of tandem mass spectrometry methodologies for large-scale protein analysis, and the application of statistical tools for data analysis and interpretation. Mol Cell Proteomics 2:428–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. von Haller PD, Yi E, Donohoe S, Vaughn K, Keller A, Nesvizhskii AI, Eng J, Li XJ, Goodlett DR, Aebersold R, Watts JD. 2003. The application of new software tools to quantitative protein profiling via isotope-coded affinity tag (ICAT) and tandem mass spectrometry. I. Statistically annotated datasets for peptide sequences and proteins identified via the application of ICAT and tandem mass spectrometry to proteins copurifying with T cell lipid rafts. Mol Cell Proteomics 2:426–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zieske LR. 2006. A perspective on the use of iTRAQ reagent technology for protein complex and profiling studies. J Exp Bot 57:1501–1508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kang UB, Yeom J, Kim H, Lee C. 2010. Quantitative analysis of mTRAQ-labeled proteome using full MS scans. J Proteome Res 9:3750–3758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fenn JB, Mann M, Meng CK, Wong SF, Whitehouse CM. 1989. Electrospray ionization for mass spectrometry of large biomolecules. Science 246:64–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tanaka K, Ido Y, Akita S, Yoshida Y, Yoshida T. 1988. Protein and polymer analysis up to m/z 100,000 by laser ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 2:151 [Google Scholar]

- 49. Karas M, Bachmann D., Hillenkamp F. 1985. Influence of the wavelength in high irradiance ultraviolet laser desorption mass spectrometry of organic molecules. Anal Chem 57:2935–2939 [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fondell JD, Ge H, Roeder RG. 1996. Ligand induction of a transcriptionally active thyroid hormone receptor coactivator complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:8329–8333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rachez C, Suldan Z, Ward J, Chang CP, Burakov D, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Freedman LP. 1998. A novel protein complex that interacts with the vitamin D3 receptor in a ligand-dependent manner and enhances VDR transactivation in a cell-free system. Genes Dev 12:1787–1800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tarallo R, Bamundo A, Nassa G, Nola E, Paris O, Ambrosino C, Facchiano A, Baumann M, Nyman TA, Weisz A. 2011. Identification of proteins associated with ligand-activated estrogen receptor α in human breast cancer cell nuclei by tandem affinity purification and nano LC-MS/MS. Proteomics 11:172–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hu ZZ, Kagan BL, Ariazi EA, Rosenthal DS, Zhang L, Li JV, Huang H, Wu C, Jordan VC, Riegel AT, Wellstein A. 2011. Proteomic analysis of pathways involved in estrogen-induced growth and apoptosis of breast cancer cells. PLoS One 6:e20410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Malorni L, Cacace G, Cuccurullo M, Pocsfalvi G, Chambery A, Farina A, Di Maro A, Parente A, Malorni A. 2006. Proteomic analysis of MCF-7 breast cancer cell line exposed to mitogenic concentration of 17β-estradiol. Proteomics 6:5973–5982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Malovannaya A, Lanz RB, Jung SY, Bulynko Y, Le NT, Chan DW, Ding C, Shi Y, Yucer N, Krenciute G, Kim BJ, Li C, Chen R, Li W, Wang Y, O'Malley BW, Qin J. 2011. Analysis of the human endogenous coregulator complexome. Cell 145:787–799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chen J, Huang P, Kaku H, Zhang K, Watanabe M, Saika T, Nasu Y, Kumon H. 2009. A comparison of proteomic profiles changes during 17β-estradiol treatment in human prostate cancer PC-3 cell line. Cancer Genomics Proteomics 6:331–335 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nilsen J, Irwin RW, Gallaher TK, Brinton RD. 2007. Estradiol in vivo regulation of brain mitochondrial proteome. J Neurosci 27:14069–14077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. She X, Jiang Z, Clark RA, Liu G, Cheng Z, Tuzun E, Church DM, Sutton G, Halpern AL, Eichler EE. 2004. Shotgun sequence assembly and recent segmental duplications within the human genome. Nature 431:927–930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mijalski T, Harder A, Halder T, Kersten M, Horsch M, Strom TM, Liebscher HV, Lottspeich F, de Angelis MH, Beckers J. 2005. Identification of coexpressed gene clusters in a comparative analysis of transcriptome and proteome in mouse tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:8621–8626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Power RF, Lydon JP, Conneely OM, O'Malley BW. 1991. Dopamine activation of an orphan of the steroid receptor superfamily. Science 252:1546–1548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Denner LA, Schrader WT, O'Malley BW, Weigel NL. 1990. Hormonal regulation and identification of chicken progesterone receptor phosphorylation sites. J Biol Chem 265:16548–16555 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Denner LA, Bingman WE, 3rd, Greene GL, Weigel NL. 1987. Phosphorylation of the chicken progesterone receptor. J Steroid Biochem 27:235–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Atsriku C, Britton DJ, Held JM, Schilling B, Scott GK, Gibson BW, Benz CC, Baldwin MA. 2009. Systematic mapping of posttranslational modifications in human estrogen receptor-α with emphasis on novel phosphorylation sites. Mol Cell Proteomics 8:467–480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wu CJ, Chen YW, Tai JH, Chen SH. 2011. Quantitative phosphoproteomics studies using stable isotope dimethyl labeling coupled with IMAC-HILIC-nanoLC-MS/MS for estrogen-induced transcriptional regulation. J Proteome Res 10:1088–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Oyama M, Nagashima T, Suzuki T, Kozuka-Hata H, Yumoto N, Shiraishi Y, Ikeda K, Kuroki Y, Gotoh N, Ishida T, Inoue S, Kitano H, Okada-Hatakeyama M. 2011. Integrated quantitative analysis of the phosphoproteome and transcriptome in tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer. J Biol Chem 286:818–829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Laserna EJ, Valero ML, Sanz L, del Pino MM, Calvete JJ, Barettino D. 2009. Proteomic analysis of phosphorylated nuclear proteins underscores novel roles for rapid actions of retinoic acid in the regulation of mRNA splicing and translation. Mol Endocrinol 23:1799–1814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lefkowitz RJ. 2004. Historical review: a brief history and personal retrospective of seven-transmembrane receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci 25:413–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Souza TA, Chen X, Guo Y, Sava P, Zhang J, Hill JJ, Yaworsky PJ, Qiu Y. 2008. Proteomic identification and functional validation of activins and bone morphogenetic protein 11 as candidate novel muscle mass regulators. Mol Endocrinol 22:2689–2702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Steinberg XP, Hepp MI, Fernández García Y, Suganuma T, Swanson SK, Washburn M, Workman JL, Gutiérrez JL. 2012. Human CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β interacts with chromatin remodeling complexes of the imitation switch subfamily. Biochemistry 51:952–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Satoh M, Tokoro M, Ikegami H, Nagai K, Sono Y, Shin SW, Nishikawa S, Saeki K, Hosoi Y, Iritani A, Fukuda A, Morimoto Y, Matsumoto K. 2009. Proteomic analysis of the mouse ovary in response to two gonadotropins, follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone. J Reprod Dev 55:316–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Martens GA, Jiang L, Verhaeghen K, Connolly JB, Geromanos SG, Stangé G, Van Oudenhove L, Devreese B, Hellemans KH, Ling Z, Van Schravendijk C, Pipeleers DG, Vissers JP, Gorus FK. 2010. Protein markers for insulin-producing β cells with higher glucose sensitivity. PLoS One 5:e14214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kim SH, Jun S, Jang HS, Lim SK. 2005. Identification of parathyroid hormone-regulated proteins in mouse bone marrow cells by proteomics. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 330:423–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Monetti M, Nagaraj N, Sharma K, Mann M. 2011. Large-scale phosphosite quantification in tissues by a spike-in SILAC method. Nat Methods 8:655–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Krüger M, Kratchmarova I, Blagoev B, Tseng YH, Kahn CR, Mann M. 2008. Dissection of the insulin signaling pathway via quantitative phosphoproteomics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:2451–2456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Gunaratne R, Braucht DW, Rinschen MM, Chou CL, Hoffert JD, Pisitkun T, Knepper MA. 2010. Quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis reveals cAMP/vasopressin-dependent signaling pathways in native renal thick ascending limb cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:15653–15658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Bansal AD, Hoffert JD, Pisitkun T, Hwang S, Chou CL, Boja ES, Wang G, Knepper MA. 2010. Phosphoproteomic profiling reveals vasopressin-regulated phosphorylation sites in collecting duct. J Am Soc Nephrol 21:303–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Border MB, Schwartz S, Carlson J, Dibble CF, Kohltfarber H, Offenbacher S, Buse JB, Bencharit S. 2012. Exploring salivary proteomes in edentulous patients with type 2 diabetes. Mol Biosyst 8:1304–1310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Kim HJ, Kim PK, Yoo HS, Kim CW. 2012. Comparison of tear proteins between healthy and early diabetic retinopathy patients. Clin Biochem 45:60–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Cssz É, Boross P, Csutak A, Berta A, Tóth F, Póliska S, Török Z, Tzsér J. 2012. Quantitative analysis of proteins in the tear fluid of patients with diabetic retinopathy. J Proteomics 75:2196–2204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Thingholm TE, Bak S, Beck-Nielsen H, Jensen ON, Gaster M. 2011. Characterization of human myotubes from type 2 diabetic and nondiabetic subjects using complementary quantitative mass spectrometric methods. Mol Cell Proteomics 10:M110.006650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Nakatani S, Kakehashi A, Ishimura E, Yamano S, Mori K, Wei M, Inaba M, Wanibuchi H. 2011. Targeted proteomics of isolated glomeruli from the kidneys of diabetic rats: sorbin and SH3 domain containing 2 is a novel protein associated with diabetic nephropathy. Exp Diabetes Res 2011:979354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Fugmann T, Borgia B, Révész C, Godó M, Forsblom C, Hamar P, Holthöfer H, Neri D, Roesli C. 2011. Proteomic identification of vanin-1 as a marker of kidney damage in a rat model of type 1 diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int 80:272–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Ma ZQ, Tabb DL, Burden J, Chambers MC, Cox MB, Cantrell MJ, Ham AJ, Litton MD, Oreto MR, Schultz WC, Sobecki SM, Tsui TY, Wernke GR, Liebler DC. 2011. Supporting tool suite for production proteomics. Bioinformatics 27:3214–3215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Faria-Campos A, Fernandes-Rausch H, Val C, Thorun P, Abreu V, Batista PH, Mendonca PH, Alves V, Rodrigues MR, Pimenta A, Franco G, Campos SV. 2011. PRODIS: a proteomics data management system with support to experiment tracking. BMC Genomics 12(Suppl 4):S15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Vitek O. 2009. Getting started in computational mass spectrometry-based proteomics. PLoS Comput Biol 5:e1000366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Deutsch EW, Lam H, Aebersold R. 2008. Data analysis and bioinformatics tools for tandem mass spectrometry in proteomics. Physiol Genomics 33:18–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Nesvizhskii AI, Vitek O, Aebersold R. 2007. Analysis and validation of proteomic data generated by tandem mass spectrometry. Nat Methods 4:787–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Listgarten J, Emili A. 2005. Statistical and computational methods for comparative proteomic profiling using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics 4:419–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Martens L, Chambers M, Sturm M, Kessner D, Levander F, Shofstahl J, Tang WH, Rompp A, Neumann S, Pizarro AD, Montecchi-Palazzi L, Tasman N, Coleman M, Reisinger F, Souda P, Hermjakob H, Binz PA, Deutsch EW. 2011. mzML: a community standard for mass spectrometry data. Mol Cell Proteomics 10:R110.000133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Lam H, Deutsch EW, Eddes JS, Eng JK, King N, Stein SE, Aebersold R. 2007. Development and validation of a spectral library searching method for peptide identification from MS/MS. Proteomics 7:655–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Bradshaw RA, Burlingame AL, Carr S, Aebersold R. 2006. Reporting protein identification data: the next generation of guidelines. Mol Cell Proteomics 5:787–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Rodriguez H, Snyder M, Uhlén M, Andrews P, Beavis R, Borchers C, Chalkley RJ, Cho SY, Cottingham K, Dunn M, Dylag T, Edgar R, Hare P, Heck AJ, Hirsch RF, Kennedy K, Kolar P, Kraus HJ, Mallick P, Nesvizhskii A, Ping P, Pontén F, Yang L, Yates JR, Stein SE, et al. 2009. Recommendations from the 2008 International Summit on Proteomics Data Release and Sharing Policy: the Amsterdam principles. J Proteome Res 8:3689–3692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. James P, Marko-Varga GA. 2011. The International Proteomics Tutorial Programme: reaching out to the next generation proteome scientists. J Proteome Res 10:3311–3312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Orchard S, Albar JP, Deutsch EW, Eisenacher M, Binz PA, Martinez-Bartolomé S, Vizcaíno JA, Hermjakob H. 2012. From proteomics data representation to public data flow: a report on the HUPO-PSI workshop September 2011, Geneva, Switzerland. Proteomics 12:351–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Gröttrup B, Böckmann M, Stephan C, Marcus K, Grinberg LT, Meyer HE, Park YM. 2012. Translational proteomics in neurodegenerative diseases–16th HUPO BPP workshop September 5, 2011 Geneva, Switzerland. Proteomics 12:356–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Jones AM, Aebersold R, Ahrens CH, Apweiler R, Baerenfaller K, Baker M, Bendixen E, Briggs S, Brownridge P, Brunner E, Daube M, Deutsch EW, Grossniklaus U, Heazlewood J, Hengartner MO, Hermjakob H, Jovanovic M, Lawless C, Lochnit G, Martens L, Ravnsborg C, Schrimpf SP, Shim YH, Subasic D, Tholey A, et al. 2012. The HUPO initiative on Model Organism Proteomes, iMOP. Proteomics 12:340–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Orchard S, Taylor CF, Jones P, Montechi-Palazzo L, Binz PA, Jones AR, Pizarro A, Julian RK, Jr, Hermjakob H. 2007. Entering the implementation era: a report on the HUPO-PSI Fall workshop 25–27 September 2006, Washington DC, USA. Proteomics 7:337–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Orchard S, Hermjakob H, Apweiler R. 2003. The proteomics standards initiative. Proteomics 3:1374–1376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Taylor CF, Paton NW, Lilley KS, Binz PA, Julian RK, Jr, Jones AR, Zhu W, Apweiler R, Aebersold R, Deutsch EW, Dunn MJ, Heck AJ, Leitner A, Macht M, Mann M, Martens L, Neubert TA, Patterson SD, Ping P, Seymour SL, Souda P, Tsugita A, Vandekerckhove J, Vondriska TM, et al. 2007. The minimum information about a proteomics experiment (MIAPE). Nat Biotechnol 25:887–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Orchard S, Salwinski L, Kerrien S, Montecchi-Palazzi L, Oesterheld M, Stümpflen V, Ceol A, Chatr-aryamontri A, Armstrong J, Woollard P, Salama JJ, Moore S, Wojcik J, Bader GD, Vidal M, Cusick ME, Gerstein M, Gavin AC, Superti-Furga G, Greenblatt J, Bader J, Uetz P, Tyers M, Legrain P, Fields S, et al. 2007. The minimum information required for reporting a molecular interaction experiment (MIMIx). Nat Biotechnol 25:894–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Orchard S, Hermjakob H. 2008. The HUPO proteomics standards initiative: easing communication and minimizing data loss in a changing world. Brief Bioinform 9:166–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Kinsinger CR, Apffel J, Baker M, Bian X, Borchers CH, Bradshaw R, Brusniak MY, Chan DW, Deutsch EW, Domon B, Gorman J, Grimm R, Hancock W, Hermjakob H, Horn D, Hunter C, Kolar P, Kraus HJ, Langen H, Linding R, Moritz RL, Omenn GS, Orlando R, Pandey A, Ping P, et al. 2012. Recommendations for mass spectrometry data quality metrics for open access data (corollary to the Amsterdam principles). Proteomics 12:11–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Orchard S, Kerrien S, Abbani S, Aranda B, Bhate J, Bidwell S, Bridge A, Briganti L, Brinkman FS, Cesareni G, Chatr-aryamontri A, Chautard E, Chen C, Dumousseau M, Goll J, Hancock RE, Hannick LI, Jurisica I, Khadake J, Lynn DJ, Mahadevan U, Perfetto L, Raghunath A, Ricard-Blum S, Roechert B, et al. 2012. Protein interaction data curation: the International Molecular Exchange (IMEx) consortium. Nat Methods 9:345–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Kerrien S, Orchard S, Montecchi-Palazzi L, Aranda B, Quinn AF, Vinod N, Bader GD, Xenarios I, Wojcik J, Sherman D, Tyers M, Salama JJ, Moore S, Ceol A, Chatr-Aryamontri A, Oesterheld M, Stümpflen V, Salwinski L, Nerothin J, Cerami E, Cusick ME, Vidal M, Gilson M, Armstrong J, Woollard P, et al. 2007. Broadening the horizon–level 2.5 of the HUPO-PSI format for molecular interactions. BMC Biol 5:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Orchard S, Kerrien S, Jones P, Ceol A, Chatr-Aryamontri A, Salwinski L, Nerothin J, Hermjakob H. 2007. Submit your interaction data the IMEx way: a step by step guide to trouble-free deposition. Proteomics 7(Suppl 1):28–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Deutsch EW, Lam H, Aebersold R. 2008. PeptideAtlas: a resource for target selection for emerging targeted proteomics workflows. EMBO Rep 9:429–434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Jones P, Martens L. 2010. Using the PRIDE proteomics identifications database for knowledge discovery and data analysis. Methods Mol Biol 604:297–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Smith BE, Hill JA, Gjukich MA, Andrews PC. 2011. Tranche distributed repository and ProteomeCommons.org. Methods Mol Biol 696:123–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Omenn GS. 2011. Data management and data integration in the HUPO plasma proteome project. Methods Mol Biol 696:247–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Carr S, Aebersold R, Baldwin M, Burlingame A, Clauser K, Nesvizhskii A. 2004. The need for guidelines in publication of peptide and protein identification data: Working Group on Publication Guidelines for Peptide and Protein Identification Data. Mol Cell Proteomics 3:531–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Wilkins MR, Appel RD, Van Eyk JE, Chung MC, Görg A, Hecker M, Huber LA, Langen H, Link AJ, Paik YK, Patterson SD, Pennington SR, Rabilloud T, Simpson RJ, Weiss W, Dunn MJ. 2006. Guidelines for the next 10 years of proteomics. Proteomics 6:4–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Unwin RD, Smith DL, Blinco D, Wilson CL, Miller CJ, Evans CA, Jaworska E, Baldwin SA, Barnes K, Pierce A, Spooncer E, Whetton AD. 2006. Quantitative proteomics reveals posttranslational control as a regulatory factor in primary hematopoietic stem cells. Blood 107:4687–4694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Bitton DA, Okoniewski MJ, Connolly Y, Miller CJ. 2008. Exon level integration of proteomics and microarray data. BMC Bioinformatics 9:118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Turinsky AL, Razick S, Turner B, Donaldson IM, Wodak SJ. 2010. Literature curation of protein interactions: measuring agreement across major public databases. Database (Oxford) 2010:baq026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Joyce AR, Palsson BØ. 2006. The model organism as a system: integrating 'omics' data sets. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7:198–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Stark C, Breitkreutz BJ, Chatr-Aryamontri A, Boucher L, Oughtred R, Livstone MS, Nixon J, Van Auken K, Wang X, Shi X, Reguly T, Rust JM, Winter A, Dolinski K, Tyers M. 2011. The BioGRID Interaction Database: 2011 update. Nucleic Acids Res 39:D698–D704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Ruepp A, Waegele B, Lechner M, Brauner B, Dunger-Kaltenbach I, Fobo G, Frishman G, Montrone C, Mewes HW. 2010. CORUM: the comprehensive resource of mammalian protein complexes–2009. Nucleic Acids Res 38:D497–D501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Prasad TS, Kandasamy K, Pandey A. 2009. Human Protein Reference Database and Human Proteinpedia as discovery tools for systems biology. Methods Mol Biol 577:67–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Hunter S, Jones P, Mitchell A, Apweiler R, Attwood TK, Bateman A, Bernard T, Binns D, Bork P, Burge S, de Castro E, Coggill P, Corbett M, Das U, Daugherty L, Duquenne L, Finn RD, Fraser M, Gough J, Haft D, Hulo N, Kahn D, Kelly E, Letunic I, Lonsdale D, et al. 2012. InterPro in 2011: new developments in the family and domain prediction database. Nucleic Acids Res 40:D306–D312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Lane L, Argoud-Puy G, Britan A, Cusin I, Duek PD, Evalet O, Gateau A, Gaudet P, Gleizes A, Masselot A, Zwahlen C, Bairoch A. 2012. neXtProt: a knowledge platform for human proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 40:D76–D83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Punta M, Coggill PC, Eberhardt RY, Mistry J, Tate J, Boursnell C, Pang N, Forslund K, Ceric G, Clements J, Heger A, Holm L, Sonnhammer EL, Eddy SR, Bateman A, Finn RD. 2012. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res 40:D290–D301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Igarashi Y, Heureux E, Doctor KS, Talwar P, Gramatikova S, Gramatikoff K, Zhang Y, Blinov M, Ibragimova SS, Boyd S, Ratnikov B, Cieplak P, Godzik A, Smith JW, Osterman AL, Eroshkin AM. 2009. PMAP: databases for analyzing proteolytic events and pathways. Nucleic Acids Res 37:D611–D618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. UniProt Consortium 2012. Reorganizing the protein space at the Universal Protein Resource (UniProt). Nucleic Acids Res 40:D71–D75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Trudgian DC, Thomas B, McGowan SJ, Kessler BM, Salek M, Acuto O. 2010. CPFP: a central proteomics facilities pipeline. Bioinformatics 26:1131–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]