Abstract

Objective To investigate the basis and added value of clinicians’ “gut feeling” that infections in children are more serious than suggested by clinical assessment.

Design Observational study.

Setting Primary care setting, Flanders, Belgium.

Participants Consecutive series of 3890 children and young people aged 0-16 years presenting in primary care.

Main outcome measures Presenting features, clinical assessment, doctors’ intuitive response at first contact with children in primary care, and any subsequent diagnosis of serious infection determined from hospital records.

Results Of the 3369 children and young people assessed clinically as having a non-severe illness, six (0.2%) were subsequently admitted to hospital with a serious infection. Intuition that something was wrong despite the clinical assessment of non-severe illness substantially increased the risk of serious illness (likelihood ratio 25.5, 95% confidence interval 7.9 to 82.0) and acting on this gut feeling had the potential to prevent two of the six cases being missed (33%, 95% confidence interval 4.0% to 100%) at a cost of 44 false alarms (1.3%, 95% confidence interval 0.95% to 1.75%). The clinical features most strongly associated with gut feeling were the children’s overall response (drowsiness, no laughing), abnormal breathing, weight loss, and convulsions. The strongest contextual factor was the parents’ concern that the illness was different from their previous experience (odds ratio 36.3, 95% confidence interval 12.3 to 107).

Conclusions A gut feeling about the seriousness of illness in children is an instinctive response by clinicians to the concerns of the parents and the appearance of the children. It should trigger action such as seeking a second opinion or further investigations. The observed association between intuition and clinical markers of serious infection means that by reflecting on the genesis of their gut feeling, clinicians should be able to hone their clinical skills.

Introduction

The early recognition of serious infection in children can be difficult but life saving. Although the incidence of serious childhood infection is falling in Europe, associated with the introduction of vaccination programmes,1 2 serious infection remains an important cause of morbidity and mortality in children.3 Early recognition is also important for those clinicians who daily see large numbers of children with minor self limiting infections every day. For example, in Belgium children aged 0-3 years see a general practitioner on average four times a year, mainly with self limiting viral illnesses.4 The diagnostic task is not as difficult as “finding a needle in the haystack” but identifying a condition with an incidence of 4-5 per 1000 population is not straightforward.5 6 It is therefore not surprising that missed cases are common—for example, an audit of children with meningococcal disease in the United Kingdom reported that half the cases had been missed at first contact.7

A lot of research has been published recently that seeks to make the diagnostic task in acutely ill children easier. The diagnostic performance of individual clinical symptoms and laboratory tests has been clarified.8 9 A wide variety of clinical features have been tested for inclusion in clinical prediction rules.10 The evidence base has been improved for the interpretation of vital signs.11 However, primary care clinicians often see patients at a stage in the course of the illness when characteristic symptoms and signs have yet to develop. In this situation, clinicians sometimes report a “gut feeling of something serious” without being able to explain why. A recent systematic review identified this gut feeling as having greater diagnostic value than most symptoms and signs and suggested it should be seen as an important diagnostic red flag in itself.8

Before this gut feeling can be taught about and applied in practice, however, there is a need to understand what is meant by the term and whether it can be characterised with sufficient clarity to be useful. One study classified it as an intuitive feeling that something is wrong, even if the clinical assessment may be reassuring.12 This intuition is therefore conceptually separate from clinical impression—a mode of clinical assessment requiring a holistic judgment but necessarily explicable in terms of defined symptoms and signs.13 14 As the intuition must to some extent arise from the clinical history and examination we clarified the added value that gut feeling provides in addition to clinical assessment for diagnosing serious infections and identified the associated features of the clinical consultation.

Methods

In 2004 we prospectively recruited 3981 children and young people aged 0-16 years who had consecutively presented with an acute illness for a maximum of five days to primary care settings in Flanders, Belgium. In this analysis we included 3890 children presenting to general practitioners or community paediatricians.

For each child we recorded a list of clinical features at point of care, including the doctors’ overall “clinical impression” of severity and whether their “gut feeling” suggested that the child had something more serious. We defined clinical impression as a subjective observation that the illness was serious on the basis of the history, observation, and clinical examination; clinical impression was recorded as either present or absent. Gut feeling was defined as an intuitive feeling that something was wrong even if the clinician was unsure why; we recorded this feature as either present, absent, or unsure (in the analyses coded as binary we used present/unsure or absent). The clinicians were told explicitly that such intuitive feelings might arise from the condition of the child (for example, a feeling that the child was unduly lethargic despite a lack of localising signs) or the behaviour of the parents (for example, a feeling that the mother was unusually anxious compared with previous consultations). Clinicians recorded these features at the end of the consultation, before any information from additional testing or referral was available.

We defined serious infections as admission to hospital for 24 or more hours with one of the following infections: pneumonia (infiltrate noted on chest radiograph), sepsis (bacterial pathogen isolated from blood culture), viral or bacterial meningitis (pleocytosis in cerebrospinal fluid and identification of bacteria or viruses), pyelonephritis (≥105/ml pathogens of a single species, white blood cells in urine, and an increase in serum C reactive protein levels), cellulitis (acute, suppurative inflammation of the subcutaneous tissues), osteomyelitis (bacterial pathogen identified from bone aspirate), and bacterial gastroenteritis (bacterial pathogens in stool). A consensus panel blinded to the results of the index tests adjudicated outcomes on the basis of information collected from 10 regional hospitals and follow-up information provided by the clinicians. Definitions of the terms used in this study and the methodology for recruitment and data collection are published elsewhere.15

A simple observational analysis was undertaken to characterise the diagnostic value of gut feeling. In case of an empty cell in a 2×2 table, we applied a correction by adding 0.5 to each cell. We carried out a multivariable logistic regression analysis using backwards selection at a significance level of 0.05 to explore the clinical features associated with gut feeling in the subset of children for whom the clinician did not have a clinical impression of serious illness. Supplementary table 2 lists the clinical features used to build the regression models. We restricted the first regression model to features that are not part of the formal clinical examination, such as a change in crying or concern of the parents. A second model was then built using all variables, including those elicited from clinical examination, such as meningeal irritation. We compared both models using the Akaike information criterion.16 This criterion balances both the goodness of fit and the number of variables used by imposing a penalty for an increasing number of variables. We selected as the optimum model that with the lowest Akaike information criterion value. Linearity of continuous features was checked with the lincheck module. All analyses were done with Stata v.11.

Results

The dataset included 3890 children, 21 of whom were admitted to hospital with a serious infection (12 for pneumonia, six for pyelonephritis, and one each for sepsis or meningitis, cellulitis, and bacterial lymphangitis). The mean age was 5.05 (range 0.02-16.93) years and 54.1% (95% confidence interval 52.5% to 55.7%) were boys.

Diagnostic added value of gut feeling

Table 1 shows the overall diagnostic performance of gut feeling separately for all the children and for children in whom the clinical assessment suggested a non-serious illness. Of the 3369 children clinically assessed as having a non-serious illness, six (0.2%) were subsequently admitted to hospital with a serious infection. A gut feeling that something was wrong despite this clinical assessment substantially increased the risk of serious illness (likelihood ratio 25.5, 95% confidence interval 7.9 to 82.0). Acting on this feeling had the potential to prevent two cases being missed (33%, 95% confidence interval 4.0% to 100%) at a cost of 44 false alarms (1.3%, 95% confidence interval 0.95% to 1.75%). When gut feeling was absent the probability of a serious infection decreased from 0.2% to 0.1%.

Table 1.

Diagnostic characteristics of clinicians’ gut feeling that something is wrong in children presenting to primary care

| Variables | Serious infection | Non-serious infection | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Predictive values (%) | Positive likelihood ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All children presenting to primary care (n=3890) | ||||||

| Gut feeling: | ||||||

| Present | 13 | 107 | 61.9 | 97.2 | Positive: 10.8, negative: 99.8 | 22.4 |

| Absent | 8 | 3762 | ||||

| Children in whom clinical impression was of a non-serious illness (n=3369)* | ||||||

| Gut feeling: | ||||||

| Present | 2 | 44 | 33.3 | 98.7 | Positive: 4.4, negative: 99.9 | 25.5 |

| Absent | 4 | 3319 | ||||

*Excludes children with clinical impression of serious illness (n=294) or for whom information on clinical impression was missing (n=227).

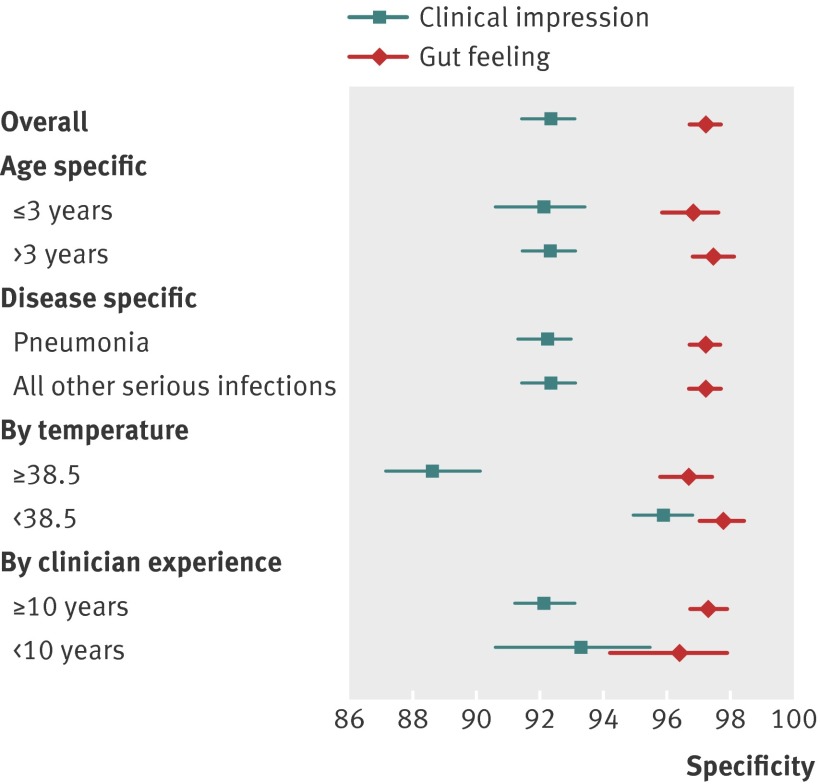

The figure compares the specificity (rule-in value) of gut feeling and clinical impression in the children. Compared with the clinical impression that the children were seriously ill, gut feeling was consistently more specific irrespective of the children’s age or diagnosis, or the seniority of the doctor (see supplementary table 1 for tabulated data on specificity, positive predictive values, and likelihood ratios).

Specificity of gut feeling and clinical impression for diagnosing serious illness in children; error bars represent 95% confidence intervals

What gives rise to gut feeling?

Table 2 shows the features independently associated with a gut feeling when the clinical impression was of a non-serious illness (see supplementary table 3 for univariate analysis). In the multivariate model excluding clinical features based on examination findings, the feature most strongly associated with gut feeling was a history of convulsions (odds ratio 80.5, 95% confidence interval 6.2 to 1051). The children’s appearance, pattern of breathing, and level of drowsiness were also significant but were much less likely to provoke a gut feeling than parental concern (odds ratio 26.9, 9.0 to 80.4). Temperature did not influence gut feeling although a history of cough and diarrhoea made a gut feeling less likely. The only other two features of the clinical history independently associated with gut feeling were weight loss and urinary symptoms.

Table 2.

Features independently associated with a gut feeling of serious infection in children for whom clinical impression of serious illness was lacking

| Features | Odds ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Model excluding variables elicited at clinical examination (n=2295)* | Model including all variables (n=2279)† | |

| Presenting symptoms: | ||

| Cough | 0.26 (0.09 to 0.71) | 0.26 (0.09 to 0.74) |

| Diarrhoea | 0.15 (0.03 to 0.72) | 0.11 (0.02 to 0.69) |

| Weight loss | 16.83 (3.29 to 85.96) | 10.53 (1.53 to 72.50) |

| Urinary symptoms | 11.64 (3.19 to 42.45) | 13.51 (3.69 to 49.44) |

| Convulsions | 80.51 (6.16 to 1051.60) | 61.72 (3.56 to 1069.56) |

| Child’s overall appearance: | ||

| Drowsiness | 3.49 (1.04 to 11.75) | — |

| No laughing | 3.37 (1.27 to 9.00) | 3.84 (1.47 to 10.04) |

| Changed breathing | 4.88 (1.38 to 17.26) | — |

| Clinical examination findings: | ||

| Tachypnoea | — | 13.64 (3.52 to 52.80) |

| Decreased consciousness | — | 52.04 (2.73 to 992.18) |

| Parental concern illness is different | 26.93 (9.02 to 80.41) | 36.26 (12.28 to 107.07) |

| Years of experience of doctor‡ | 0.95 (0.90 to 1.00) | 0.95 (0.90 to 1.00) |

*R2=0.3174.

†R2=0.3397.

‡Years since graduation from medical school.

Incorporating the features elicited by clinical examination in the multivariate model marginally increased the goodness of fit, indicating that gut feeling is not entirely an intuitive process independent of formal clinical examination and history taking. However, inclusion of these variables had little impact on the estimated associations—the main change was that the clinical findings of decreased consciousness and tachypnoea displaced the reported symptoms of drowsiness and changed breathing pattern. The estimated importance of parental concern was increased (odds ratio 36.3, 12.3 to 107.1). For every year of additional experience, the clinician was 5% less likely to experience a gut feeling separate from their clinical assessment (odds ratio 0.95, 0.90 to 1.00).

Late admissions

Of the 21 children who were eventually admitted to hospital with a serious infection, nine were not referred at first contact (despite the initial clinical impression of a serious illness in four children). Table 3 describes the clinical features of these nine cases. In these nine children the mean age (2.2 v 2.1 years), mean duration of illness (41.0 v 54.5 hours), and mean temperature (38.8°C v 39.3°C) did not differ significantly from those referred immediately at first contact. However, in four of the nine children (44%), the clinician had a gut feeling of something serious.

Table 3.

Children not referred at first contact but with a final diagnosis of serious infection at hospital admission

| Child | Age (years) | Duration of illness (h) | Temperature (°C) | Non-specific clinical features | Gut feeling something wrong | Working hypothesis at consultation | Final diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5.32 | 24 | 36.9 | Drowsy, does not laugh, signs of upper respiratory tract infection, vomiting, decreased eating and drinking | Yes | Viral gastroenteritis and upper respiratory tract infection | Bacterial lymphangitis |

| 2 | 3.23 | 5 | 38.8 | Irritable, inconsolable, different crying, does not laugh | Yes | Viral syndrome | Pneumonia |

| 3 | 1.44 | 48 | 38.8 | Irritable, different crying, does not laugh, diarrhoea, cough, abnormal breathing, tachypnoea, dyspnoea | Yes | Viral syndrome (pneumonia?) | Pneumonia |

| 4 | 1.04 | 5 | — | Drowsy, inconsolable, different crying, does not laugh, signs of upper respiratory tract infection, decreased eating and drinking, cough, changed breathing, dyspnoea | Yes | Asthma attack | Pneumonia |

| 5 | 3.24 | 72 | 38.5 | Signs of upper respiratory tract infection, tummy ache | No | urinary tract infection and upper respiratory tract infection | Pyelonephritis |

| 6 | 1.81 | 24 | 39.1 | Irritable, inconsolable, does not laugh, signs of upper respiratory tract infection, vomiting, cough, somnolent, dyspnoea | No | upper respiratory tract infection | Pneumonia |

| 7 | 2.38 | 120 | 40.0 | None recorded | No | Pyelonephritis | Pyelonephritis |

| 8 | 1.31 | 24 | 39.4 | Diarrhoea, decreased eating and drinking | No | Viral gastroenteritis | Pyelonephritis |

| 9 | 0.2 | 48 | — | Signs of upper respiratory tract infection, cough, dyspnoea | No | upper respiratory tract infection | Pneumonia |

Discussion

The gut feelings of primary care clinicians of something wrong in children even when unexplained by clinical assessment had a high specificity and high positive likelihood ratio for serious infectious illness. This finding was consistent across age and diagnostic groups and was independent of the presence of fever. The diagnostic value of a gut feeling changed little with clinical experience although the more senior the doctors the less likely they were to experience a gut feeling in addition to forming a clinical impression. This is presumably because the holistic clinical features that trigger gut feeling are gradually assimilated into clinical assessment.

The nature of the features that gave rise to a gut feeling of something serious were not surprising—general appearance, breathing pattern, weight loss, and history of convulsions. However, the intuitive feelings of primary care doctors were also strongly influenced by parental concern, specifically that the illness was different from any previously experienced.

Temperature did not influence the probability of gut feeling. We had hypothesised that a high temperature (>39°C) without localising signs would give rise to a gut feeling of something wrong, but our results contradicted this assumption. It is possible that temperature did contribute to gut feeling but did not appear in the multivariate analysis because it was correlated with other features, especially parental concern (which was also likely to be influenced by temperature). Nevertheless, it is important that primary care clinicians recognise the diagnostic value of fever in their clinical assessment—for every 20 children with a temperature of 40°C or more in a primary setting, one will have a serious infection.8

Similarly, the symptom of diarrhoea reduced the probability of a gut feeling about serious illness in children. Although this may reflect the fact that the diagnostic importance of diarrhoea is fully recognised in the clinical assessment, it is also possible that the potential diagnostic importance of diarrhoea is misunderstood in primary care. Although diarrhoea is also a common symptom of self limiting illness, its presence in a young child taken to a general practitioner is a less benign feature; not just because of the risk of complications related to fluid loss but also because diarrhoea can be a presenting symptom of sepsis.8 Therefore the presence of unexplained diarrhoea as a presenting symptom in a child should probably increase intuitive concern rather than reassure.

Limitations of the study

Analysing the components of gut feeling was not the primary aim of the original study and therefore the study was not powered to do so. Although 120 children elicited a gut feeling in the clinicians of something wrong, only 21 children were admitted to hospital with a serious infection, so some of the estimates of diagnostic performance lack precision. Moreover, the analyses may not provide a complete explanation of gut feeling, as the amount of variance explained by the multivariate models was modest (R2 estimates 0.32 and 0.34). This lack of explanatory power was also suggested by the observation that although senior clinicians did not experience gut feelings as often as their junior colleagues, the diagnostic power of their gut feeling was similar. Studies should try to resolve the residual unexplained variation, including information on variation between clinicians, either from within the same setting, from different settings or from different countries. Another limitation of the current analyses is possible bias related to the diagnostic investigations. Children for whom clinicians had a gut feeling were referred more often than children for whom clinicians did not have a gut feeling. It is possible that the risk of being admitted for a serious infection was influenced by additional testing done in secondary care. However, the diagnostic value of gut feeling was similar in the group of children with suspected non-serious illness on initial clinical assessment and who were therefore not initially referred.

Comparison with other studies

Clinical reasoning involves integrating intuitive and analytical processes. One study suggested that the intuitive process involves rapid framing of a problem; looking for specific features, including red flags; and connecting these to an existing mental model.17 Gut feeling has been described as an intuitive feeling that results from a rapid, unconscious process that is context specific and comes with experience.18 In contrast, we found that less experienced clinicians reported gut feelings more often than did senior clinicians, suggesting increasing diagnostic certainty with experience, perhaps also suggesting that the features triggering a gut feeling are assimilated into conscious diagnostic reasoning processes over time. However, the diagnostic power of gut feeling was no better in experienced clinicians than in non-experienced clinicians.

Exploration of the meaning of gut feeling in other aspects of clinical decision making has suggested that it depends above all on knowledge of what is normal—this is, much more important than knowledge of the potentially serious condition itself. For example, in making referral decisions in patients with acute chest pain,19 or in recognising children with behavioural or mental problems,20 the gut feeling described seemed to refer to deviation from a recognised pattern, triggered by the clinician’s interpretation of the patient’s narrative and knowledge of the patient and family.

We sought to discriminate between gut feeling (a feeling of something wrong without knowing quite why) and non-intuitive clinical impression explicable in terms of the formal process of history taking and examination. The consistent difference in diagnostic performance of these two constructs, with gut feeling having consistently higher specificity, suggests that the clinicians involved in the study recognised the difference between gut feeling and clinical impression. However, the concept of clinical impression demands an element of holistic assessment and it has also been found useful in diagnosing bacteraemia,21 22 meningococcal disease,23 and gastrointestinal infection with dehydration.24 Nevertheless, we suspect clinical impression focuses solely on the clinical presentation whereas gut feeling brings other factors into play, especially parental concern but also contradictory findings (for example, between observation, history, or clinical examination), differences with previous illness episodes, and lack of pattern recognition.

Implications for practice

Although students and trainees are taught to look at children’s overall appearance and breathing, there seems to be a potential gap between the routine clinical assessment of these features and the more holistic response, producing a “something is wrong” gut feeling. Perhaps we should also be more explicit in encouraging sensitivity to parental concern, stressing that it does make the presence of serious illness more likely even when clinical examination is reassuring. We should certainly make clear when teaching that an inexplicable (or not fully explicable) gut feeling is an important diagnostic sign and a good reason for seeking the opinion of someone with more expertise or scheduling a review of the child.

Although clinicians throughout Europe mention gut feelings in their daily practice,25 our observation of colleagues suggests that the diagnostic value of this intuitive response is often dismissed. Even experienced clinicians need to be clear about the red flag properties of gut feelings. Gut feelings should not be ignored but used in decision making. The referral of all children for whom an inexperienced clinician in primary care has a gut feeling that something is wrong has the potential to result in large numbers of unnecessary visits to the emergency department. However we suggest that having a gut feeling that something is wrong should make three things mandatory: the carrying out of a full and careful examination, seeking advice from more experienced clinicians (by referral if necessary), and providing the parent with carefully worded advice to act as a “safety net.”26 The observed association between gut feeling and clinical markers of serious infection means that by reflecting on the genesis of their gut feeling, clinicians should be able to hone their clinical skills.

Our data are restricted to assessment of children in primary care. The estimates of diagnostic value cannot necessarily be extrapolated to adults and other clinical settings. However, the experience of gut feelings is a common phenomenon across medicine and it seems unlikely that its diagnostic value could not be harnessed elsewhere.

What is already known on this topic

About 1 in 200 children seen in primary care have a serious illness that is easily missed

In assessing children in primary care, the clinician’s intuitive feeling that something is wrong seems to have diagnostic value

Neither the basis of intuition nor its added value to the clinical history and examination is understood

What this study adds

Gut feeling is the clinician’s response to the feelings of the parent and the appearance of the child

Acting on gut feeling has the potential to significantly reduce the number of missed cases without causing an unmanageable number of false alarms

Where gut feeling suggests something serious despite a reassuring clinical examination, clinicians should seek a second opinion or initiate further investigations

We thank Rafael Perera for advising on the statistical analyses.

Contributors: AVdB conceived the study, did the main analyses, and contributed to the interpretation of the results and the drafting of the manuscript. She is guarantor of the study. MT contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and the drafting of the manuscript. FB conceived and designed the original study and contributed to the conception, design, and interpretation of the current analyses and the drafting of the manuscript. DM contributed to the conception and design of the current analyses, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. All authors gave final approval of the version submitted.

Funding: The original study was funded by a grant of the Research Foundation-Flanders (FWO) and an unconditional grant from Eurogenerics. None of the funders had any role in the design or analysis of the original study nor of the current analyses. The present analyses were done as part of the MaDOx programme, which presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research under its programme grants for applied research funding scheme (RP-PG-0407-10347). MT is funded by a career development fellowship supported by the National Institute for Health Research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the National Institute for Health Research, or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare that they have received no support from any organisation for the submitted work; have no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; and have no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the medical ethics committee of the Catholic University of Leuven.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2012;345:e6144

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Supplementary tables 1-3

References

- 1.Slack MP, Azzopardi HJ, Hargreaves RM, Ramsay ME. Enhanced surveillance of invasive Haemophilus influenzae disease in England, 1990 to 1996: impact of conjugate vaccines. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1998;17(suppl 9):S204-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trotter CL, Andrews NJ, Kaczmarski EB, Miller E, Ramsay ME. Effectiveness of meningococcal serogroup C conjugate vaccine 4 years after introduction. Lancet 2004;364:365-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health. Why children die: a pilot study 2006; England (South West, North East and West Midlands), Wales and Northern Ireland. In: Pearson GA, ed. CEMACH, 2008.

- 4.Van den Bruel A, Bartholomeeusen S, Aertgeerts B, Truyers C, Buntinx F. Serious infections in children: an incidence study in family practice. BMC Fam Pract 2006;7:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant CC, Harnden A, Mant D, Emery D, Coster G. Why do children hospitalised with pneumonia not receive antibiotics in primary care? Arch Dis Child 2012;97:21-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harnden A. Recognising serious illness in feverish young children in primary care. BMJ 2007;335:409-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson MJ, Ninis N, Perera R, Mayon-White R, Phillips C, Bailey L, et al. Clinical recognition of meningococcal disease in children and adolescents. Lancet 2006;367:397-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van den Bruel A, Haj-Hassan T, Thompson M, Buntinx F, Mant D. Diagnostic value of clinical features at presentation to identify serious infection in children in developed countries: a systematic review. Lancet 2010;375:834-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van den Bruel A, Thompson MJ, Haj-Hassan T, Stevens R, Moll H, Lakhanpaul M, et al. Diagnostic value of laboratory tests in identifying serious infections in febrile children: systematic review. BMJ 2011;342:d3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson M, Van den Bruel A, Verbakel J, Lakhanpaul M, Haj-Hassan T, Stevens R, et al. Systematic review and validation of prediction rules for identifying children with serious infections in emergency departments and urgent-access primary care. Health Technol Assess 2012;16:1-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleming S, Thompson M, Stevens R, Heneghan C, Pluddemann A, Maconochie I, et al. Normal ranges of heart rate and respiratory rate in children from birth to 18 years of age: a systematic review of observational studies. Lancet 2011;377:1011-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stolper E, Van de Wiel M, Van Royen P, Van Bokhoven M, Van der Weijden T, Dinant GJ. Gut feelings as a third track in general practitioners’ diagnostic reasoning. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:197-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCarthy PL, Lembo RM, Fink HD, Baron MA, Cicchetti DV. Observation, history, and physical examination in diagnosis of serious illnesses in febrile children less than or equal to 24 months. J Pediatr 1987;110:26-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berger RM, Berger MY, van Steensel-Moll HA, Dzoljic-Danilovic G, Derksen-Lubsen G. A predictive model to estimate the risk of serious bacterial infections in febrile infants. Eur J Pediatr 1996;155:468-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van den Bruel A, Aertgeerts B, Bruyninckx R, Aerts M, Buntinx F. Signs and symptoms for diagnosis of serious infections in children: a prospective study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2007;57:538-46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Automat Contr 1974;19:716-23. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balla JI, Heneghan C, Glasziou P, Thompson M, Balla ME. A model for reflection for good clinical practice. J Eval Clin Pract 2009;15:964-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenhalgh T. Intuition and evidence—uneasy bedfellows? Br J Gen Pract 2002;52:395-400. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruyninckx R, Van den Bruel A, Hannes K, Buntinx F, Aertgeerts B. GPs’ reasons for referral of patients with chest pain: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract 2009;10:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lykke K, Christensen P, Reventlow S. “This is not normal . . .”—signs that make the GP question the child’s well-being. Fam Pract 2008;25:146-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haddon RA, Barnett PL, Grimwood K, Hogg GG. Bacteraemia in febrile children presenting to a paediatric emergency department. Med J Aust 1999;170:475-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waskerwitz S, Berkelhamer JE. Outpatient bacteremia: clinical findings in children under two years with initial temperatures of 39.5 degrees C or higher. J Pediatr 1981;99:231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wells LC, Smith JC, Weston VC, Collier J, Rutter N. The child with a non-blanching rash: how likely is meningococcal disease? Arch Dis Child 2001;85:218-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shavit I, Brant R, Nijssen-Jordan C, Galbraith R, Johnson DW. A novel imaging technique to measure capillary-refill time: improving diagnostic accuracy for dehydration in young children with gastroenteritis. Pediatrics 2006;118:2402-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stolper E, van Royen P, Dinant GJ. The ‘sense of alarm’ (‘gut feeling’) in clinical practice. A survey among European general practitioners on recognition and expression. Eur J Gen Pract 2010;16:72-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Almond S, Mant D, Thompson M. Diagnostic safety-netting. Br J Gen Pract 2009;59:872-4; discussion 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary tables 1-3