Abstract

Objectives To describe the association and its magnitude between body mass index category, sex, and cardiovascular disease risk parameters in school aged children in highly developed countries.

Design Systematic review and meta-analysis. Quality of included studies assessed by an adapted version of the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias assessment tool. Results of included studies in meta-analysis were pooled and analysed by Review Manager version 5.1.

Data sources Embase, PubMed, EBSCOHost’s cumulative index to nursing and allied health literature, and the Web of Science databases for papers published between January 2000 and December 2011.

Review methods Healthy children aged 5 to 15 in highly developed countries enrolled in studies done after 1990 and using prospective or retrospective cohort, cross sectional, case-control, or randomised clinical trial designs in school, outpatient, or community settings. Included studies had to report an objective measure of weight and at least one prespecified risk parameter for cardiovascular disease.

Results We included 63 studies of 49 220 children. Studies reported a worsening of risk parameters for cardiovascular disease in overweight and obese participants. Compared with normal weight children, systolic blood pressure was higher by 4.54 mm Hg (99% confidence interval 2.44 to 6.64; n=12 169, eight studies) in overweight children, and by 7.49 mm Hg (3.36 to 11.62; n=8074, 15 studies) in obese children. We found similar associations between groups in diastolic and 24 h ambulatory systolic blood pressure. Obesity adversely affected concentrations of all blood lipids; total cholesterol and triglycerides were 0.15 mmol/L (0.04 to 0.25, n=5072) and 0.26 mmol/L (0.13 to 0.39, n=5138) higher in obese children, respectively. Fasting insulin and insulin resistance were significantly higher in obese participants but not in overweight participants. Obese children had a significant increase in left ventricular mass of 19.12 g (12.66 to 25.59, n=223), compared with normal weight children.

Conclusion Having a body mass index outside the normal range significantly worsens risk parameters for cardiovascular disease in school aged children. This effect, already substantial in overweight children, increases in obesity and could be larger than previously thought. There is a need to establish whether acceptable parameter cut-off levels not considering weight are a valid measure of risk in modern children and whether methods used in their study and reporting should be standardised.

Background

Two thirds of the world’s population live in countries where obesity related illness is a significant cause of death.1 As well as a considerable increase in adult obesity, there is good evidence that more children are also becoming obese. Over a 30 year period, the worldwide prevalence of obesity in childhood has increased substantially, with the greatest weight increase in those most obese.2 3 Globally in 2010, just under 43 million children younger than five years were overweight.1

Being overweight in adulthood is well known to increase the risk of cardiovascular disease.4 However, the effect of obesity on children is currently less well understood, in terms of the age at which risk parameters for cardiovascular disease begin to be affected and the magnitude of the effect. Nevertheless, a growing body of evidence suggests a similar association. In a 2009 study of children aged one to 17 years, being overweight increased the odds ratio for prehypertension by 50% and doubled or tripled the odds of hypertension, compared with normal weight children.5

Atherosclerosis has also been shown to begin as early as nine years of age; the cross sectional area of the common carotid artery wall and the mean intima media thickness of the internal carotid artery increases considerably from lean to obese children.6 7 8 Childhood obesity has been linked to a 12 fold increase in fasting insulin concentration in obese children aged five to 17 years.9 In addition, amounts of triglycerides, total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL cholesterol), and high density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL cholesterol) are all more likely to be abnormal in overweight children than in normal weight children.9 Risk parameters for cardiovascular disease in childhood such as body mass index, cholesterol, blood pressure, and triglyceride concentrations have shown to be significantly correlated with adult levels over long term follow-up.10 11 12 13 14 Furthermore, raised risk of cardiovascular disease has been found13 14 15 16 as well as increased coronary heart disease events over a five million person year follow-up.13 Therefore, childhood health could greatly affect the risk of cardiovascular disease in adulthood.

Studies that have focused on interventions to prevent or treat overweight children have had mixed success, with initial positive effects regressing back to and in some cases exceeding baseline.17 18 19 20 Therefore, it may be better to understand the effect of body mass index on cardiovascular disease risk parameters in school aged children and direct interventions to the most important risk parameters to reduce risk. However, to our knowledge, there has been no systematic examination of the magnitude of the relationship between body mass index categories and sex on risk parameters for cardiovascular disease in school aged children.

In view of increasing obesity, combined with the rates at which lifestyle changes have occurred in recent years, studies published as little as 15 years ago may no longer be relevant to modern children. For example, reports have been made on a 12% decline in 1991-97 in the number of high school students participating in daily physical education classes,21 a downward trend in the number of children walking or cycling to school,22 and an increase in sedentary behaviours such as computer use.23 Therefore, as a primary outcome we aimed to systematically review the evidence to examine the magnitude of the association between body mass index and risk parameters for cardiovascular disease in children. As a secondary outcome, if sufficient data were available, we aimed to examine whether the association between body mass index and cardiovascular disease risk is mediated by sex.

Methods

Review search strategy

To investigate the effect of body mass index on cardiovascular disease risk parameters in childhood, we searched the following databases: Embase, PubMed, EBSCOHost’s cumulative index to nursing and allied health literature, and the Web of Science. We combined the 18 search terms relating to overweight and obesity with 33 cardiovascular and metabolic outcomes, truncated with wildcard characters if necessary (web appendix 1). Search terms not covered under the MeSH tree were searched as keywords. Finally, we hand searched reference lists of the identified articles for further studies. To understand the current association between body mass index and cardiovascular disease for children, the search was limited to studies conducted after 1990 and published between January 2000 and December 2011. The search was not limited by language of publication.

We searched for studies in healthy children aged 5 to 15 years, those studies which included participants that fell outside this age range were excluded. We included studies from the 42 highly developed countries as defined by the United Nations’ human development index.24 We only included papers conducted in highly developed countries, to increase the comparability of the children in the studies since they would be more likely to have similar lifestyles.

Eligible studies included an objective measure of weight and one or more of the following cardiovascular disease risk parameters: systolic or diastolic blood pressure, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol or total cholesterol, triglyceride, fasting glucose, fasting insulin, Homeostasis Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance, carotid intima media thickness, and left ventricular mass. These parameters are risk factors for either atherosclerosis (such as carotid intima media thickness) or cardiovascular disease (such as blood pressure and cholesterol). Left ventricular mass and carotid intima media thickness were chosen as the physiological parameters of interest because they both provide evidence for the development of atherosclerosis in adolescents aged 12-18 years and have been correlated with other risk factors for coronary heart disease.25 Furthermore, we chose left ventricular mass over, for example, left ventricular hypertrophy, because it is more commonly assessed in child samples and has been found to be correlated to a predisposition for future hypertension in children, adolescents, and young adults.26

We included studies with a prospective or retrospective cohort, cross sectional, case-control, or randomised controlled trial design administered in school, outpatient, or community settings. We specified a minimum sample size of 20 participants for cross sectional or cohort studies and 20 participants per study arm in intervention studies, to limit potential small study effects in the meta-analysis. We excluded studies if the children had been diagnosed with another chronic physical or mental medical condition, or another condition associated with overweight (such as psychosocial problems, asthma, or sleep disordered breathing) was the primary outcome. We also excluded studies in inpatient settings, that used a pharmacological treatment, or that were a protocol or pilot study.

After the removal of duplicates, titles were reviewed by one author (CF), and studies that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. Two reviewers (CF and KM) independently reviewed the abstracts of the remaining papers and removed any that did not meet the inclusion criteria. Two reviewers (CF and KM) read the full texts of the papers and extracted the data from the papers that met the inclusion criteria. We resolved any disagreements regarding the inclusion or exclusion of papers through discussion with a third reviewer (CH). Web appendix 1 contains the full list of search terms and limits placed on the search. No further review protocol is available.

Data analysis

We analysed data descriptively and through a meta-analysis. Studies were included in the meta-analysis if they reported data for at least one unhealthy category of body mass index as well as the normal category of body mass index, at a level of detail sufficient for the pooled analysis. Those studies not included in the meta-analysis were analysed descriptively; web appendix 2.1 contains the full list of reasons for exclusion from the meta-analysis. The descriptive data for each risk parameter from published papers was extracted independently by two reviewers (CF and KM) and summarised using mean and standard deviation where possible. If the included paper reported on a prospective or retrospective study or randomised controlled trial, the baseline data for the whole sample was extracted. We used conversion factors (table 1) to convert reported values to standard international units and a standard formula for combining subgroup means.27

Table 1.

Conversion factors used for conventional to standard international units

| Risk parameter for cardiovascular disease | Conventional unit | Conversion factor | SI unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total, HDL, and LDL cholesterol | mg/dL | 0.0259 | mmol/L |

| Glucose | mg/dL | 0.0555 | mmol/L |

| Insulin | μIU/mL | 6.945 | pmol/L |

| Triglyceride | mg/dL | 0.0113 | mmol/L |

Analysis of cardiovascular disease risk parameters was performed in four categories of body mass index: underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese. We classified these categories according to the international age and sex specific curves passing through body mass index values 17, 25, and 30 at age 18 years, as defined by Cole and colleagues.28 29 Using these definitions, children who were underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese were each defined as having a body mass index of 17 or less, 17 to 25, more than 25 to 30, and more than 30, respectively. If studies reported the mean weight of their sample rather than the mean body mass index, or the definitions of the cut-off points used did not match those used in this review, we reclassified the data according to the cut-off points of Cole and colleagues.

We used Review Manager (version 5.1) to analyse the mean differences in the cardiovascular disease risk parameters for each body mass index category compared with normal weight children, and where possible stratified by sex. We used random effects models rather than fixed effects models to allow for variation in study effects, owing to a real dispersion in the effect sizes across studies (expected from varying factors such as ages, ethnicities, and methods). In addition, a random effects model is more appropriate for balancing weights across large and small studies.27 30 Heterogeneity was measured by I2, which indicates the amount of variability in the data that is due to heterogeneity rather than error.31 32 We also calculated the effect sizes for each risk parameter comparison between normal with overweight or obese children.

Owing to the high number of risk parameters for cardiovascular disease used, we reported results with 99% confidence intervals as a more stringent measure of significance. We did subgroup analyses based on sex where possible, but because of insufficient data, we were unable to perform subgroup analyses on different age categories.

Quality assessment

Since no standard tool existed for quality assessment that could be applied to all our included studies,33 we based quality assessment on the Cochrane risk of bias tool (Review Manager version 5.1, Cochrane Collaboration). We rated risk of bias in the three areas that were relevant to all types of study: blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, and selective reporting. We added two further categories: measurement methods that were not suitable or precise, and use of an unrepresentative sample.33 34 Papers were assigned as moderate risk for bias if the level of bias was unclear from the paper or if their rate of participation was between 60% and 80%. To assess the influence of low quality studies (as identified in the quality assessment) on our results, we did a sensitivity analysis excluding them from the pooled analysis.

Results

Study characteristics and quality

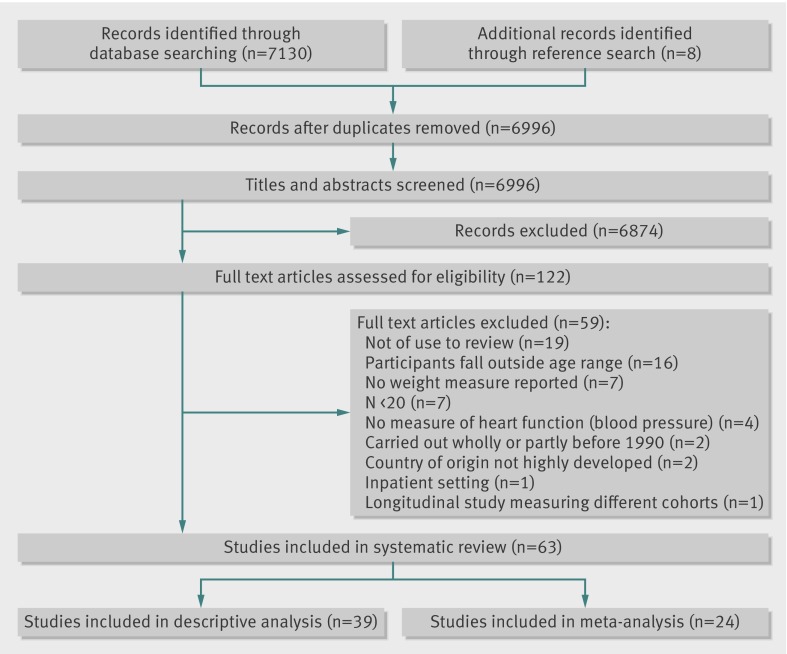

Of 6996 papers, we included 63 of 49 220 children in 23 countries (web appendix 2). Figure 1 shows the number of papers excluded at each stage of review. The number of children in included studies varied between 38 and 7589 (age range 5-15 years). Three countries contributed 25 (40%) included studies: United States (11 studies), Italy (eight), and Denmark (six). The remaining papers were conducted in: Sweden, Cyprus, Israel, Belgium, Japan, Greece, and Iceland (one study each); Hong Kong, Hungary, South Korea, Norway, and France (two); Spain, Germany, United Kingdom, and Australia (three); Switzerland, Estonia, and Canada (four); and Portugal (five). We included 42 cross sectional studies, 19 randomised controlled trials, one cohort study, and one case-control study. Most studies were performed in school (34 studies) or clinical outpatient (23) settings, with fewer in community settings (five) and one multicentre study. Of the 63 included papers, 24 supplied data for the meta-analysis (web appendix 3). Two papers included in the meta-analysis reported geometric means or least mean squares rather than arithmetic means,35 36 but because sensitivity analysis excluding these studies found no difference in significance or heterogeneity, they were included in the final analyses.

Fig 1 Progression of papers through the review process

Quality assessment

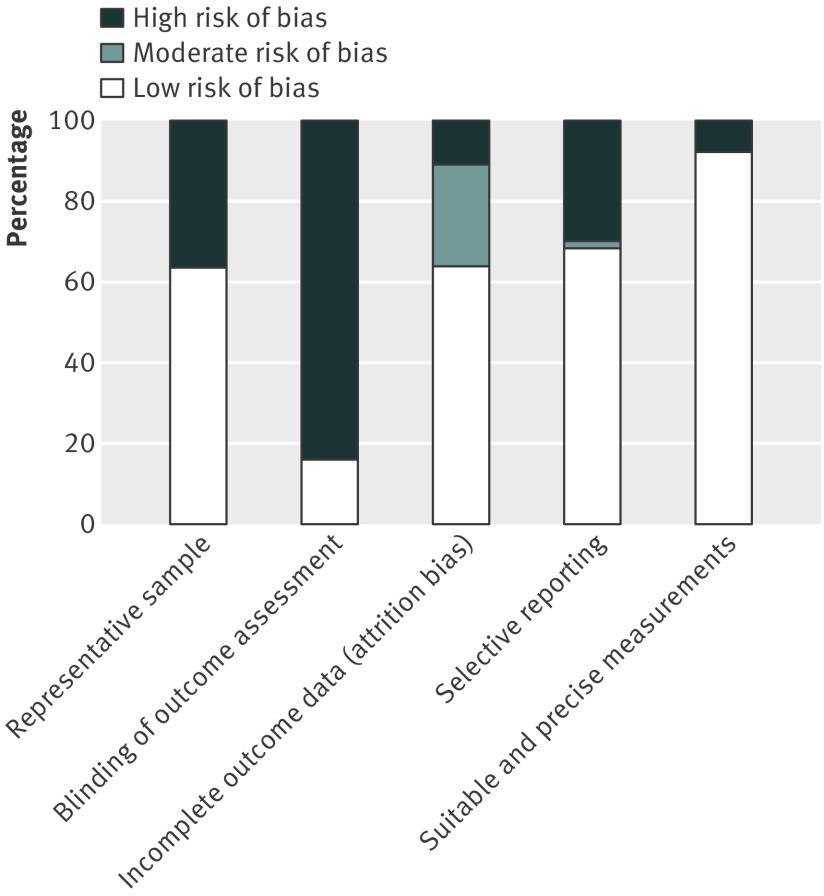

Figures 2 and 3 show the results of the risk of bias assessment. Only two studies scored low risk in all five bias categories,37 38 57 were described as moderate risk scoring low risk in two to four of the categories, and four were described as high risk scoring a low risk for bias in one or fewer of the categories.35 39 40 41 The most common source of bias was a lack of blinding of the outcome assessors, that is, the researchers analysing the risk parameter levels were frequently not blinded to the body mass index of the child. The risk of bias from unsuitable or imprecise measurement methods was generally small, with only five studies judged to be at high risk—most frequently because of failure to repeat and take the average of measurements carried out by hand, and the use of assessment tools that may not have been applicable to the study sample. Sensitivity analysis excluding the one low quality study in the meta-analysis found little effect on most measures, with the exception of diastolic blood pressure in overweight compared with normal weight girls, in which the test for overall effect became insignificant. No studies were excluded due to low quality.

Fig 2 Outcome of risk of bias assessment by paper. Studies labelled a and b refer to different papers by the same authors published in the same year

Fig 3 Outcome of risk of bias assessment by type of bias

Descriptive analysis

Thirty nine studies did not provide data for the meta-analysis, and we included them as a descriptive analysis. In these papers, we found that general risk parameters for cardiovascular disease were worsened by high body mass index. Body mass index was positively associated with systolic blood pressure in five studies,40 42 43 44 45 diastolic blood pressure in four studies,42 43 44 45 total cholesterol in one study,46 LDL cholesterol in three studies,43 45 46 triglycerides in three studies,43 45 46 and left ventricular mass in one study,47 and inversely associated with HDL cholesterol in two studies.45 46 Body mass index was also associated with cardiovascular disease risk parameter clustering,43 44 48 49 50 51 and one study found the metabolic syndrome to be present in a statistically significant number of its overweight sample.48

No studies reported cardiovascular disease risk associated with underweight as defined by the cut-off values for body mass index used in this review. In the study reporting the risk parameter levels in very lean children, lipids, insulin resistance, intima media thickness, and blood pressure levels were similar to those in overweight children.52 Web appendices 3.1 and 3.2 provide a more detailed description of the main findings of interest to our review.

Meta-analysis

Systolic, diastolic, and ambulatory measures of blood pressure were significantly higher in overweight and obese participants compared with normal weight participants (table 2). Resting systolic blood pressure was higher in overweight children by 4.54 mm Hg (99% confidence interval 2.44 to 6.64, P<0.001; eight studies, 12 169 children) and in obese children by 7.49 mm Hg (3.36 to 11.62, P<0.001; 15, 8074). Systolic blood pressure increased to a greater degree in girls than boys in both overweight and obese categories (P<0.001). Diastolic blood pressure was increased by 2.57 mm Hg (1.55 to 3.58, P<0.001; seven, 11 529) and by 4.06 mm Hg (2.05 to 6.08, P<0.001; 16, 8140) in overweight and obese children, respectively. As with systolic blood pressure, girls showed a greater increase than boys in diastolic blood pressure (P<0.001; table 2). Ambulatory systolic blood pressure over 24 h was increased in obese children by 11.55 mm Hg (1.26 to 21.84, P=0.004; five, 823) compared with normal weight, but with a wide confidence interval.

Table 2.

Mean differences in blood pressure

| Parameter | No of studies | No of participants | Mean difference (99% CI), random effects model | Test for heterogeneity* | Test for overall effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resting systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | |||||

| Obese v normal weight | |||||

| All | 15 | 8074 | 7.49 (3.36 to 11.62) | χ2=188.82, I2=93 | Z=4.67, P<0.001 |

| Girls | 4 | 4739 | 12.72 (7.08 to 18.37) | χ2=38.77, I2=92 | Z=5.80, P<0.001 |

| Boys | 4 | 5013 | 10.81 (7.75 to 13.86) | χ2=11.72, I2=74 | Z=9.11, P<0.001 |

| Overweight v normal weight | |||||

| All | 8 | 12 169 | 4.54 (2.44 to 6.64) | χ2=50.26, I2=86 | Z=5.57, P<0.001 |

| Girls | 3 | 5160 | 6.03 (4.61 to 7.46) | χ2=3.07, I2=35 | Z=10.90, P<0.001 |

| Boys | 3 | 5160 | 5.67 (3.32 to 8.03) | χ2=7.28, I2=73 | Z=6.20, P<0.001 |

| Resting diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | |||||

| Obese v normal weight | |||||

| All | 16 | 8140 | 4.06 (2.05 to 6.08) | χ2=104.36, I2=86 | Z=5.19, P<0.001 |

| Girls | 4 | 4723 | 7.40 (3.85 to 10.95) | χ2=34.39, I2=91 | Z=5.37, P<0.001 |

| Boys | 4 | 5013 | 6.09 (3.78 to 8.40) | χ2=16.04, I2=81 | Z=6.80, P<0.001 |

| Overweight v normal weight | |||||

| All | 7 | 11 529 | 2.57 (1.55 to 3.58) | χ2=17.96, I2=67 | Z=6.49, P<0.001 |

| Girls | 3 | 5160 | 2.66 (1.20 to 4.13) | χ2=5.39, I2=63 | Z=4.68, P<0.001 |

| Boys | 3 | 5160 | 2.36 (1.74 to 2.98) | χ2=1.35, I2=0 | Z=9.80, P<0.001 |

| 24 h ambulatory blood pressure (mm Hg) | |||||

| Overweight v normal weight | |||||

| Systolic, all | 5 | 823 | 11.55 (1.26 to 21.84) | χ2=114.62, I2=97 | Z=2.89, P=0.004 |

| Diastolic, all | 5 | 823 | 6.09 (−0.11 to 12.29) | χ2=135.72, I2=97 | Z=2.53, P=0.01 |

*Data for I2 values are percentages.

Total cholesterol was significantly higher in all obese children by 0.15 mmol/L (99% confidence interval 0.04 to 0.25, P<0.001; nine studies, 5072 children) and in obese girls by 0.31 mmol/L (0.08 to 0.54, P<0.001; three, 2213), but no significant effect was found in overweight children. Compared with normal weight children, HDL cholesterol was significantly lower in overweight children by 0.17 mmol/L (−0.22 to −0.13, P<0.001; five, 5752), in obese children by 0.22 mmol/L (−0.39 to −0.06, P<0.001; eight, 4915), and in obese boys by 0.29 mmol/L (−0.34 to −0.24, P=0.55; two, 2470) but not in obese girls. Compared with normal weight children, triglycerides were higher in overweight children by 0.21 mmol/L (0.14 to 0.27, P<0.001; five, 6515), obese children by 0.26 mmol/L (0.13 to 0.39, P<0.001; 10, 5138), obese girls by 0.28 mmol/L (0.04 to 0.51, P=0.002; three, 2213), and obese boys by 0.30 mmol/L (0.19 to 0.41, P<0.001; three, 2557; table 3).

Table 3.

Mean differences in lipid concentrations

| Parameter | No of studies | No of participants | Mean difference (99% CI), random effects model | Test for heterogeneity* | Test for overall effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | |||||

| Obese v normal weight | |||||

| All | 9 | 5072 | 0.15 (0.04 to 0.25) | χ2=8.31, I2=4 | Z=3.67, P<0.001 |

| Girls | 3 | 2213 | 0.31 (0.08 to 0.54) | χ2=3.65, I2=45 | Z=3.44, P<0.001 |

| Boys | 3 | 2557 | 0.14 (−0.11 to 0.39) | χ2=5.95, I2=66 | Z=1.49, P=0.14 |

| Overweight v normal weight | |||||

| All | 5 | 5949 | 0.02 (−0.21 to 0.17) | χ2=17.16, I2=77 | Z=0.29, P=0.77 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | |||||

| Obese v normal weight | |||||

| All | 7 | 4773 | 0.18 (0.09 to 0.26) | χ2=5.62, I2=0 | Z=5.27, P<0.001 |

| Overweight v normal weight | |||||

| All | 3 | 5036 | −0.02 (−0.41 to 0.37) | χ2=18.55, I2=89 | Z=0.12, P=0.91 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | |||||

| Obese v normal weight | |||||

| All | 8 | 4915 | −0.22 (−0.39 to −0.06) | χ2=61.82, I2=89 | Z=3.60, P<0.001 |

| Girls | 2 | 2153 | −0.10 (−0.66 to 0.47) | χ2=29.07, I2=97 | Z=0.44, P=0.66 |

| Boys | 2 | 2470 | −0.29 (−0.34 to −0.24) | χ2=25, I2=96 | Z=0.60, P=0.55 |

| Overweight v normal weight | |||||

| All | 5 | 5752 | −0.17 (−0.22 to −0.13) | χ2=4.68, I2=15 | Z=10.63, P<0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | |||||

| Obese v normal weight | |||||

| All | 10 | 5138 | 0.26 (0.13 to 0.39) | χ2=42.25, I2=79 | Z=5.08, P<0.001 |

| Girls | 3 | 2213 | 0.28 (0.04 to 0.51) | χ2=15.12, I2=87 | Z=3.06, P=0.002 |

| Boys | 3 | 2557 | 0.30 (0.19 to 0.41) | χ2=3.06, I2=35 | Z=7.03, P<0.001 |

| Overweight v normal weight | |||||

| All | 5 | 6515 | 0.21 (0.14 to 0.27) | χ2=10.50, I2=62 | Z=8.01, P<0.001 |

*Data for I2 values are percentages.

Fasting glucose, insulin, and insulin resistance were significantly raised only in obese children (table 4). Obese boys had significantly higher levels of fasting glucose than normal weight boys by 0.29 mmol/L (99% confidence interval 0.12 to 0.46, P<0.001; two studies, 345 children). Fasting insulin levels were significantly higher in obese girls by 70.90 pmol/L (49.52 to 92.28, P<0.001; two, 221) and obese boys by 77.03 pmol/L (41.70 to 112.36, P<0.001; two, 345) when compared with normal weight girls and boys.

Table 4.

Mean differences in fasting insulin, glucose, and insulin resistance

| Parameter | No of studies | No of participants | Mean difference (99% CI), random effects model | Test for heterogeneity* | Test for overall effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | |||||

| Obese v normal weight | |||||

| All | 8 | 771 | 0.10 (−0.03 to 0.23) | χ2=17.05, I2=59 | Z=1.96, P=0.05 |

| Girls | 2 | 221 | 0.15 (−0.03 to 0.33) | χ2=0.37, I2=0 | Z=2.20, P=0.03 |

| Boys | 2 | 345 | 0.29 (0.12 to 0.46) | χ2=0.18, I2=0 | Z=4.48, P<0.001 |

| Overweight v normal weight | |||||

| All | 3 | 348 | 0.13 (−0.04 to 0.31) | χ2=3.99, I2=50 | Z=1.99, P=0.05 |

| Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance | |||||

| Obese v normal weight | |||||

| All | 7 | 779 | 1.32 (0.83 to 1.82) | χ2=26.89, I2=78 | Z=6.89, P<0.001 |

| Overweight v normal weight | |||||

| All | 2 | 760 | 0.88 (−0.08 to 1.85) | χ2=16.53, I2=94 | Z=2.36, P=0.02 |

| Fasting insulin (pmol/L) | |||||

| Obese v normal weight | |||||

| All | 6 | 629 | 48.47 (31.96 to 64.97) | χ2=18.98, I2=74 | Z=7.56, P<0.001 |

| Girls | 2 | 221 | 70.90 (49.52 to 92.28) | χ2=2.10, I2=52 | Z=8.54, P<0.001 |

| Boys | 2 | 345 | 77.03 (41.70 to 112.36) | χ2=3.45, I2=71 | Z=5.62, P<0.001 |

| Overweight v normal weight | |||||

| All | 3 | 924 | 21.82 (−1.44 to 45.08) | χ2=23.28, I2=91 | Z=2.42, P=0.02 |

*Data for I2 values are percentages.

Finally, for physiological parameters, obesity was associated with an increase in left ventricular mass of 19.12 g (99% confidence interval 12.66 to 25.59, P<0.001; three studies, 223 children); this effect was still significant after adjusting for height (increase 11.29 g/m, 6.49 to 16.10, P<0.001; five, 918; table 5).

Table 5.

Mean differences in intima media thickness, left ventricular mass, and left ventricular mass indexed for height

| Parameter | No of studies | No of participants | Mean difference (99% CI), random effects model | Test for heterogeneity* | Test for overall effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intima media thickness (mm) | |||||

| Obese v normal weight | |||||

| All | 5 | 592 | 0.03 (0.00 to 0.06) | χ2=34.07, I2=88 | Z=2.61, P=0.009 |

| Left ventricular mass (g) | |||||

| Obese v normal weight | |||||

| All | 3 | 223 | 19.12 (12.66 to 25.59) | χ2=0.27, I2=0 | Z=7.62, P<0.001 |

| Left ventricular mass adjusted for height (g/m) | |||||

| Obese v normal weight | |||||

| All | 5 | 918 | 11.29 (6.49 to 16.10) | χ2=39.50, I2=90 | Z=6.06, P<0.001 |

*Data for I2 values are percentages.

Approximations had to be made of the number of participants per group for two papers in the meta-analysis. For Aguilar and colleagues,53 the number reported for each body mass index category was halved to approximate the numbers in the intervention and control groups. For Falaschetti and colleagues,35 the proportion of the total participants in each measurement was calculated, and the number for each measure under each body mass index category was that proportion of the total number of children in each category. Analyses were conducted without these papers but this did not significantly affect the results and so they were included.

Half the studies in the meta-analysis adjusted for confounders including age, sex, birth weight, physical activity, parental overweight or education, baseline measures, or the various risk parameters for cardiovascular disease. Such adjustments were made when the study went on to further analyse the data to answer a research question. Since this review used only baseline data in the meta-analysis, all data were unadjusted with the exception of left ventricular mass adjusted for height.

Discussion

Main findings

We found that obesity was associated with significantly worse risk parameters for cardiovascular disease in school aged children. This association was also true for overweight children, although the effect was not as strong as for obese children. The effect sizes found were substantial and are concerning, in view their potential effect on the risk of future cardiovascular disease. As an example of the gradient effect of increased body mass index on risk parameters for cardiovascular disease, the mean difference in systolic blood pressure between normal weight and obese children was 40% higher than the difference between normal and overweight children. Additionally, concentrations of total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol were 7.5 times (0.15 v 0.02 mmol/L) and nine times (0.18 v 0.02 mmol/L) higher, respectively, in the obese versus normal weight comparison than in the overweight versus normal weight comparison. The increase in mean difference in the body mass index from the normal versus overweight comparison to the normal versus obese comparison was about five points for both the total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol analyses. This difference translates to an increase of 0.026 mmol/L in total cholesterol and 0.036 mmol/L in LDL cholesterol for each body mass index point gained in our analyses.

Comparison with other studies

A 2011 review undertaken by an expert panel and funded by the National Institutes of Health suggested that in the next 25 years, obesity will increase the incidence of coronary heart disease in adults by 5% to 16%,6 based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data for obese adolescents in 2000. This prediction may still be an underestimate since the data used were a decade old at the time the simulation was performed, and were based on obese adolescents. As such, these data did not take into account the effect that being overweight might also have, as found in our review.

Raised concentration of fasting insulin has been linked to a twofold increase in the future incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus.54 and this review found fasting insulin to be 2.2 times higher in obese versus normal weight comparisons than in overweight versus normal weight comparisons. Furthermore, raised triglyceride levels are an independent risk factor for type 2 diabetes in men.55 Raised concentrations of triglycerides increase the incidence of coronary heart disease in men 3.6-fold to 4.7-fold,56 and double the relative risk of myocardial infarction in women.57 We found that lipid levels were significantly more abnormal in overweight and obese children. Levels of HDL cholesterol in obese children were lowered to such an extent that an equivalent reduction from the acceptable level (as defined by expert panels from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Cholesterol Education Program) would result in a child falling into the lowest percentile for HDL cholesterol concentration.6 58 This result suggests that these children will enter the abnormal lipid levels as an adult earlier and may have the associated atherosclerotic damage and illness end points at a younger age.

We found left ventricular mass and left ventricular mass adjusted for height to be significantly raised in obese children. In children, height adjusted left ventricular mass has been correlated to both body mass index and systolic blood pressure,59 and has been suggested to be an indicator for the need for pharmacological treatment of paediatric hypertension.6 What is clear from our findings and the work of previous researchers is weight, and especially obesity, has a significant effect on the risk parameters for cardiovascular disease that are present in children from age five years. This effect could give them a head start on their normal and even overweight classmates for future cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and stoke.

Two factors relate to the potential implication of the elevations we identified in risk parameters for cardiovascular disease in overweight and obese children on cardiovascular related outcomes in adulthood. Firstly, the extent to which these elevated levels continue into adulthood. Evidence indicates that risk factors can track into adulthood,6 10 11 60 and these increase the risk of many conditions in addition to coronary heart disease—for example, type 2 diabetes, and musculoskeletal, pulmonary, and psychosocial complications.2 In particular, it has been reported that tracking occurs for elevated blood pressure (that is, elevated blood pressure in childhood is likely to persist into adulthood), although correlation coefficients are moderate and related to baseline blood pressure, age, and method of measurement.11 61

Secondly, in view of the evidence that tracking occurs, it is unclear whether the magnitude of difference in cardiovascular disease risk parameters between normal, overweight, and obese children continues unchanged into adulthood. If the magnitudes between the differences do continue, the effect of excess weight on cardiovascular disease risk, as we have noted particularly in obese children, will probably have a profound effect in adulthood. For instance, adults with a 10 mm Hg reduction in systolic blood pressure or a 5 mm Hg reduction in diastolic blood pressure has been linked to a 30-40% reduction in stroke mortality risk and a 30% reduction in mortality from ischaemic heart disease.62 63 Even a reduction of 2 mm Hg in systolic blood pressure was associated with a 10% reduction in stroke and a 7% reduction in ischemic heart disease risk.62 This association in adulthood was linear at all levels of blood pressure, true at all ages and unaffected by sex. In our review, obese children had higher systolic and diastolic blood pressure than normal weight children, by 7.5 mm Hg and 4.1 mm Hg, respectively. In this obese group, ambulatory systolic blood pressure at 24 h was also significantly increased by 11.55mm Hg, and previous research has shown this measurement method to be more accurate than both clinic and home measures of blood pressure.64 Therefore, if these pressures are allowed to track unchecked into adulthood, obese children could already be at a 30-40% higher risk of future stroke and ischaemic heart disease than their normal weight counterparts. Indeed, the effect of obesity on future health, particularly cardiovascular health, could be far greater than previously suggested.

Limitations of the review

Several limitations to this review are worth noting. Firstly, we saw a high level of heterogeneity between studies in some risk parameters. Although we defined inclusion criteria carefully to ensure that the participants of included studies were as similar as possible, factors such as ethnicity, pubertal status, and age still varied. We also placed few restrictions on the type of study that could be included, and thus, influencing factors such as setting and measurement methods could have added to the heterogeneity. Additionally, although the large sample in this review meant that random variation should have had little effect on the estimates of difference, reporting methods frequently varied between studies (such as for units of measurement, summary statistics, and cut-off points).

Secondly, we were unable to assess the influence of age and pubertal status because too few papers reported data at the required level of detail. This lack of detail suggests a need for more primary research into the effect of weight on cardiovascular disease risk in different age groups. Thirdly, our review was limited by missing data either from potentially eligible studies that were missed, or by data that were not reported in the included studies. However, we believe that our search strategy was robust and unlikely to have missed eligible studies, and that there was a low risk of selective reporting because most of the included studies were scored as low risk for reporting bias.

Fourthly, the conclusions from our review only provide a picture of the cardiovascular disease risk of children at the time they were measured. Therefore, our review cannot establish the relation between risk parameters for cardiovascular disease and the ongoing changes in weight in the same child, nor can it determine how the disease risk in those children might progress into adulthood. Finally, a potential source of error was that two papers in the meta-analysis included children who fell close to or on the cut-off point for a body mass index category, or who had a body mass index category that needed reclassification in our analysis.65 66 This was because of discrepancies between the definitions of the category boundaries used by each study and those used in our review (web appendix 4). Although this introduces a risk of misclassification, it was necessary in order to pool and analyse the data. However, we believe that any misclassification would not have led to any significant errors in the analyses since these two papers contributed small samples compared with the total number of children in the analysis, and only one study’s sample was reclassified as overweight, although it grouped all overweight and obese children together.66

Recommendations and conclusions

The current study has shown that overweight and obese children have raised risk parameters for cardiovascular disease compared with normal weight children; however, the exact ages at which changes in a child’s risk parameters begin need to be established. Risk parameters could then be targeted before abnormal levels are reached and treatment could be preventative. In addition, the continuous association between body mass index and risk parameters for cardiovascular disease is an area of interest for future research, particularly if the change in risk parameters per unit increase of body mass index can be established.

Since we only included studies done in highly developed countries, the findings may not be generalisable to children in low and middle developed countries. This review could therefore be expanded to examine these settings. Future work could also clarify the link between childhood body mass index, risk parameters, and morbidity and mortality related to cardiovascular disease in adults. Although excess weight in childhood has been linked to adverse health outcomes in adulthood,67 a 2010 review reported little evidence to suggest that childhood body mass index was an independent risk factor.68 The interaction between body mass index and risk parameters could contribute to adulthood disease rather than the individual effects of each factor, but this theory needs to be confirmed.

Currently, studies in this area are limited by the lack of consensus on cut-off points and standardisation in measurement methods. For example, when defining categories by body mass index, studies in this systematic review used 11 different sets of cut-off values ranging in publication dates from 1986 to 2006. We examined the differences in the 90th, 95th, and 97th centile cut-off points in the three most frequently cited papers28 69 70 and found that they differed by as much as five points at some thresholds of body mass index (web appendix 5). These differences may arise from the different populations that form the basis for the cut-off points. This weakness has been tackled by creation of thresholds based on international samples, although their generalisability to populations worldwide is still unknown. Moreover, differences in cut-off points used to identify children at risk for cardiovascular disease has considerable implications for the numbers categorised as at higher risk, and for subsequent therapeutic decisions such as drug treatments or lifestyle changes. Therefore, the most appropriate cut-offs and methods should be established to improve the quality and comparability of studies undertaken.

Finally, existing definitions of “normal” levels of risk parameters for cardiovascular disease should be re-examined and take into account the weight of the child as well as their age and height. Blood pressure and lipid tables such as those published by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) claim to provide a more precise definition of childhood blood pressure centiles by incorporating height or age into their calculations, but fail to take into account the weight of the child.71 72 For instance, an increase of 7.49 mm Hg found in obese children in this review would result in all children being diagnosed as hypertensive unless their blood pressure based on their age and height was lower than the 25th centile according to these tables. Likewise, the obese children assessed in our review had an overall mean triglyceride level of 1.1 mmol/L, which would place them in the borderline to high category according to screening recommendations from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

This review suggests that we may not fully appreciate the extent of the association between body mass index and cardiovascular disease risk in children. It also highlights that without standardising the definitions and methods of measurement of risk parameters and ensuring that all acceptable levels of these are calculated, taking weight into account, further research could be hindered by error and poor comparability between studies. In conclusion, this review aimed to investigate the association, and the magnitude of that association, between body mass index and cardiovascular disease risk parameters in children. We found that overweight and obesity have a significant effect on blood pressure, lipids, insulin levels and resistance, and left ventricular mass. This effect on risk parameters for cardiovascular disease is greatest in obese children and the implications for their future health may be greater than has been previously suggested.

What is already known on this topic

Increased weight is associated with raised risk of an abnormal blood pressure and lipid profile, and could contribute to early changes in risk parameters for cardiovascular disease in children

The magnitude of the association between weight and these risk parameters among children in different categories body mass index has not been systematically established

What this study adds

Compared with normal weight children, obese children (body mass index ≥30) have raised systolic and diastolic blood pressure by 7.49 mm Hg and 4.45 mm Hg, respectively, and increased concentrations of total cholesterol by 0.15 mmol/L

All parameters measured had similar increases, showing a gradient effect with lesser increases in overweight children compared with normal weight children

Being overweight or obese in childhood may have a larger effect on risk parameters for cardiovascular disease and on future health than previously thought. Existing definitions of “normal” levels of risk parameters should be re-examined to take into account the child’s weight and the age when changes in cardiovascular disease risk parameters begin should be established

Contributors: CF participated in the protocol design, search design, literature search, screening of papers, data extraction, data analysis, data interpretation, creation of figures, writing, and editing. CH participated in the protocol design, screening of papers, data interpretation, writing, and editing. KM participated in the screening of papers, data extraction, writing, and editing. MT participated in the data interpretation, writing, and editing. RP participated in the data analysis. AW participated in the protocol design, data interpretation, writing, and editing. All authors had full access to all the data collected in this systematic review, have checked for accuracy, and agree to submit this manuscript.

Funding: This review received no specific funding.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; CF receives a stipend from the Medical Research Council; CH teaches workshops on evidence based medicine, does media work, writes for the Guardian newspaper, attends World Health Organization meetings, and has coauthored toolkit books on statistics and evidence based medicine; MT received grant funding in 2011-12 to Oregon Health Sciences University from the United States Preventive Services task force, to a lead the evidence review for the task force’s review on screening for hypertension in children; AW attends WHO meetings; the University Department of Primary Care Health Sciences is part of the National Institutes for Health Research School of Primary Care Research, which provide financial support for senior staff who contributed to this paper; no other relationships or activities exist that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval was not required for this study.

Data sharing: Data for each study are available from the corresponding author.

Cite this as: BMJ 2012;345:e4759

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Web appendix: Supplementary material (web appendices 1-4)

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight factsheet number 311. 2011. www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/index.html.

- 2.Ebbeling CB, Pawlak DB, Ludwig DS. Childhood obesity: public-health crisis, common sense cure. Lancet 2002;360:473-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flegal KM, Troiano RP. Changes in the distribution of body mass index of adults and children in the US population. Int J Obes 2000;24:807-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McPherson K, Marsh T, Brown M. Tackling obesities: future choices—modelling future trends in obesity and the impact on health: report for Foresight. Government Office for Science, 2007.

- 5.Rosner B, Cook N, Portman R, Daniels S, Falkner B. Blood pressure differences by ethnic group among United States children and adolescents. Hypertension 2009;54:502-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kavey R, Simons-Morton D, de Jesus J. Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents: summary report. Pediatrics 2011;S213-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Stabouli S, Kotsis V, Papamichael C, Constantopoulos A, Zakopoulos N. Adolescent obesity is associated with high ambulatory blood pressure and increased carotid intimal-medial thickness. J Pediatr 2005;147:651-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyer AA, Kundt G, Steiner M, Schuff-Werner P, Kienast W. Impaired flow-mediated vasodilation, carotid artery intima-media thickening, and elevated endothelial plasma markers in obese children: the impact of cardiovascular risk factors. Pediatrics 2006;117:1560-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freedman DS, Dietz WH, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. The relation of overweight to cardiovascular risk factors among children and adolescents: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Pediatrics 1999;103:1175-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juhola J, Magnussen CG, Viikari JSA, Kähönen M, Hutri-Kähönen N, Jula A, et al. Tracking of serum lipid levels, blood pressure, and body mass index from childhood to adulthood: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. J Pediatr 2011;159:584-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen X, Wang Y. Tracking of blood pressure from childhood to adulthood: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Circulation 2008;117:3171-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freedman DS, Patel DA, Srinivasan SR, Chen W, Tang R, Bond MG, et al. The contribution of childhood obesity to adult carotid intima-media thickness: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Int J Obes 2008;32:749-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baker JL, Olsen LW, Sorensen TIA. Childhood body mass index and the risk of coronary heart disease in adulthood. N Engl J Med 2007;357:2329-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrison JA, Glueck CJ, Horn PS, Yeramaneni S, Wang P. Pediatric triglycerides predict cardiovascular disease events in the fourth to fifth decade of life. Metabolism 2009;58:1277-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrison JA, Glueck CJ, Wang P. Childhood risk factors predict cardiovascular disease, impaired fasting glucose plus type 2 diabetes mellitus, and high blood pressure 26 years later at a mean age of 38 years: the Princeton-lipid research clinics follow-up study. Metabolism 2012;61:531-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gunnell D, Frankel S, Nanchahal K, Peters T, Davey Smith G. Childhood obesity and adult cardiovascular mortality: a 57-y follow-up study based on the Boyd Orr cohort. Am J Clin Nutr 1998;67:1111-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barlow SE, Dietz WH. Obesity evaluation and treatment: expert committee recommendations. Pediatrics 1998;102:e29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Epstein LH, Myers MD, Raynor HA, Saelens BE. Treatment of pediatric obesity. Pediatrics 1998;101:554-70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris KC, Kuramoto LK, Schulzer M, Retallack JE. Effect of school-based physical activity interventions on body mass index in children: a meta-analysis. CMAJ 2009;180:719-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaya FT, Flores D, Gbarayor CM, Wang J. School-based obesity interventions: a literature review. J Sch Health 2008;78:189-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowry R, Wechsler H, Kann L, Collins J. Recent trends in participation in physical education among US high school students. J Sch Health 2001;71:145-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Department for Transport. National travel survey 2010. 2012. www.dft.gov.uk/pgr/statistics/datatablespublications/nts/index.html.

- 23.Nelson MC, Neumark-Stzainer D, Hannan PJ, Sirard JR, Story M. Longitudinal and secular trends in physical activity and sedentary behavior during adolescence. Pediatrics 2006;118:e1627-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.United Nations. Human development report 2010. 2nd ed. Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

- 25.Kelishadi R, Sabri M, Motamedi N, Ramezani MA. Factor analysis of markers of inflammation and oxidation and echocardiographic findings in children with a positive family history of premature coronary heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol 2009;30:477-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dekkers JC, Treiber FA, Kapuku G, Snieder H. Differential influence of family history of hypertension and premature myocardial infarction on systolic blood pressure and left ventricular mass trajectories in youth. Pediatrics 2003;111:1387-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011.

- 28.Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ 2000;320:1240-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cole TJ, Flegal KM, Nicholls D, Jackson AA. Body mass index cut offs to define thinness in children and adolescents: international survey. BMJ 2007;335:194-202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to meta-analysis. John Wiley and Sons Ltd, 2009.

- 31.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altman DG. Systematic reviews of evaluations of prognostic variables. BMJ 2001;323: 224-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Heneghan C, Badenoch D. Evidence based medicine toolkit. 2nd ed. Blackwell Publishing, 2006.

- 35.Falaschetti E, Hingorani AD, Jones A, Charakida M, Finer N, Whincup P, et al. Adiposity and cardiovascular risk factors in a large contemporary population of pre-pubertal children. Eur Heart J 2010;31:3063-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Platat C, Wagner A, Klumpp T, Schweitzer B, Simon C. Relationships of physical activity with metabolic syndrome features and low-grade inflammation in adolescents. Diabetologia 2006;49:2078-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aggoun Y, Farpour-Lambert NJ, Marchand LM, Golay E, Maggio ABR, Beghetti M. Impaired endothelial and smooth muscle functions and arterial stiffness appear before puberty in obese children and are associated with elevated ambulatory blood pressure. Eur Heart J 2008;29:792-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roh EJ, Lim JW, Ko KO, Cheon EJ. A useful predictor of early atherosclerosis in obese children: serum high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. J Korean Med Sci 2007;22:192-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Evans RK, Franco RL, Stern M, Wickham EP, Bryan DL, Herrick JE, et al. Evaluation of a 6-month multi-disciplinary healthy weight management program targeting urban, overweight adolescents: effects on physical fitness, physical activity, and blood lipid profiles. Int J Pediatr Obes 2009;4:130-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Graf C, Rost SV, Koch B, Heinen S, Falkowski G, Dordel S. Data from the StEP TWO programme showing the effect on blood pressure and different parameters for obesity in overweight and obese primary school children. Cardiol Young 2005;15:291-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reinehr T, Schaefer A, Winkel K, Finne E, Toschke AM, Kolip P. An effective lifestyle intervention in overweight children: findings from a randomized controlled trial on “Obeldicks light.” Clin Nutr 2010;29:331-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mirzaei M, Taylor R, Morrell S, Leeder SR. Predictors of blood pressure in a cohort of school-aged children. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2007;14:624-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Savva SC, Tornaritis M, Savva ME, Kourides Y, Panagi A, Silikiotou N, et al. Waist circumference and waist-to-height ratio are better predictors of cardiovascular disease risk factors in children than body mass index. Int J Obes 2000;24:1453-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thomas N-E, Cooper SM, Williams SP, Baker JS, Davies B. Relationship of fitness, fatness, and coronary-heart-disease risk factors in 12- to 13-year-olds. Pediatr Exerc Sci 2007;19:93-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vizcaino VM, Aguilar FS, Martinez MS, Lopez MS, Gutierrez RF, Rodriguez-Artalejo F. Association of adiposity measures with blood lipids and blood pressure in children aged 8-11 years. Acta Paediatr 2007;96:1338-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Teixeira PJ, Sardinha LB, Going SB, Lohman TG. Total and regional fat and serum cardiovascular disease risk factors in lean and obese children and adolescents. Obesity 2001;9:432-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Woo KS, Chook P, Yu CW, Sung RYT, Qiao M, Leung SSF, et al. Effects of diet and exercise on obesity-related vascular dysfunction in children. Circulation 2004. a;109:1981-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Andersen LB, Wedderkopp N, Hansen HS, Cooper AR, Froberg K. Biological cardiovascular risk factors cluster in Danish children and adolescents: the European Youth Heart Study. Prev Med 2003;37:363-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jago R, Harrell JS, McMurray RG, Edelstein S, El Ghormli L, Bassin S. Prevalence of abnormal lipid and blood pressure values among an ethnically diverse population of eighth-grade adolescents and screening implications. Pediatrics 2006;117:2065-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ribeiro JC, Guerra S, Oliveira J, Teixeira-Pinto A, Twisk JWR, Duarte JA, et al. Physical activity and biological risk factors clustering in pediatric population. Prev Med 2004;39:596-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Steene-Johannessen J, Kolle E, Anderssen SA, Andersen LB. Cardiovascular disease risk factors in a population-based sample of Norwegian children and adolescents. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 2009;69:380-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Giannini C, de Giorgis T, Scarinci A, Cataldo I, Marcovecchio ML, Chiarelli F, et al. Increased carotid intima-media thickness in pre-pubertal children with constitutional leanness and severe obesity: the speculative role of insulin sensitivity, oxidant status, and chronic inflammation. Eur J Endocrinol 2009;161:73-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aguilar FS, Martinez-Vizcaino V, Lopez MS, Martinez MS, Gutierrez RF, Martinez SS, et al. Impact of an after-school physical activity program on obesity in children. J Pediatr 2010;157:36-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dankner R, Chetrit A, Shanik MH, Raz I, Roth J. Basal-state hyperinsulinemia in healthy normoglycemic adults is predictive of type 2 diabetes over a 24-year follow-up. Diabetes Care 2009;32:1464-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tirosh A, Shai I, Bitzur R, Kochba I, Tekes-Manova D, Israeli E, et al. Changes in triglyceride levels over time and risk of type 2 diabetes in young men. Diabetes Care 2008;31:2032-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tirosh A, Rudich A, Shochat T, Tekes-Manova D, Israeli E, Henkin Y, et al. Changes in triglyceride levels and risk for coronary heart disease in young men. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:377-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lindquist P, Bengtsson C, Lissner L, Björkelund C. Cholesterol and triglyceride concentration as risk factors for myocardial infarction and death in women, with special reference to influence of age. J Int Med 2002;251:484-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.NCEP Expert Panel on Blood Cholesterol Levels in Children and Adolescents. National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP): highlights of the report of the Expert Panel on Blood Cholesterol Levels in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics 1992;89:495-501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Richey PA, DiSessa TG, Hastings MC, Somes GW, Alpert BS, Jones DP. Ambulatory blood pressure and increased left ventricular mass in children at risk for hypertension. J Pediatr 2008;152:343-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Webber LS, Srinivasan SR, Wattigney WA, Berenson GS. Tracking of serum lipids and lipoproteins from childhood to adulthood. Am J Epidemiol 1991;133:884-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen X, Wang Y, Appel LJ, Mi J. Impacts of measurement protocols on blood pressure tracking from childhood into adulthood. Hypertension 2008;51:642-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Prospective Studies Collaboration. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet 2002;360:1903-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lawes CMM, Bennett DA, Feigin VL, Rodgers A. Blood pressure and stroke. Stroke 2004;35:776-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hodgkinson J, Mant J, Martin U, Guo B, Hobbs FDR, Deeks JJ, et al. Relative effectiveness of clinic and home blood pressure monitoring compared with ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in diagnosis of hypertension: systematic review. BMJ 2011;342:d3621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Di Bonito P, Carldo B, Forziato C, Sanguigno E, Di Fraia T, Scilla C, et al. Central adiposity and left ventricular mass in obese children. Nutr Metab Carbiovasc Dis 2008;18:613-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Suriano K, Curran J, Byrne SM, Jones TW, Davis EA. Fatness, fitness, and increased cardiovascular risk in young children. J Pediatr 2010;157:552-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Juhola J, Magnussen CG, Viikari JSA, Kähönen M, Hutri-Kähönen N, Jula A, et al. Tracking of serum lipid levels, blood pressure, and body mass index from childhood to adulthood: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. J Pediatr 2011;159:584-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lloyd LJ, Langley-Evans SC, McMullen S. Childhood obesity and adult cardiovascular disease risk: a systematic review. Int J Obes 2010;34:18-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Guo SS, Wei R, et al. CDC growth charts: United States. Report number: 314. National Center for Health Statistics, 2000.

- 70.Kromeyer-Hauschild K, Wabitsch M, Kunze D, Geller F, Geiß HC, Hesse V, et al. Perzentile für den Body-mass-Index für das Kindes- und Jugendalter unter Heranziehung verschiedener deutscher Stichproben. Monatsschr Kinderheilk 2001;149:807-18. [Google Scholar]

- 71.National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. NIH Publication number 05-5267. NIH, 2005.

- 72.Daniels SR, Benuck I, Christakis DA, Dennison BA, Gidding SS, Gillman MW. Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2011.

- 73.Alhassan S, Robinson TN. Objectively measured physical activity and cardiovascular disease risk factors in African American girls. Ethn Dis 2008;18:421-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Andersen LB, Harro M, Sardinha LB, Froberg K, Ekelund U, Brage S, et al. Physical activity and clustered cardiovascular risk in children: a cross-sectional study (the European Youth Heart Study). Lancet 2006;368:299-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bouziotas C, Koutedakis Y, Nevill A, Ageli E, Tsigilis N, Nikolaou A, et al. Greek adolescents, fitness, fatness, fat intake, activity, and coronary heart disease risk. Arch Dis Child 2004;89:41-4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brage S, Wedderkopp N, Ekelund U, Franks PW, Wareham NJ, Andersen LB, et al. Features of the metabolic syndrome are associated with objectively measured physical activity and fitness in Danish children: the European Youth Heart Study (EYHS). Diabetes Care 2004;27:2141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Carrel AL, Clark RR, Peterson SE, Nemeth BA, Sullivan J, Allen DB. Improvement of fitness, body composition, and insulin sensitivity in overweight children in a school-based exercise program: a randomized, controlled study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2005;159:963-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ekelund U, Anderssen SA, Froberg K, Sardinha LB, Andersen LB, Brage S, et al. Independent associations of physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness with metabolic risk factors in children: the European youth heart study. Diabetologia 2007;50:1832-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Flouris AD, Canham CH, Faught BE, Klentrou P. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk in Ontario adolescents. Arch Dis Child 2007;92:521-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hansen SE, Hasselstrom H, Gronfeldt V, Froberg K, Andersen LB. Cardiovascular disease risk factors in 6-7-year-old Danish children: the Copenhagen school child intervention study. Prev Med 2005;40:740-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Johnson ST, Kuk JL, Mackenzie KA, Huang TTK, Rosychuk RJ, Ball GDC. Metabolic risk varies according to waist circumference measurement site in overweight boys and girls. J Pediatr 2010;156:247-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kalarchian MA, Levine MD, Arslanian SA, Ewing LJ, Houck PR, Cheng Y, et al. Family-based treatment of severe pediatric obesity: randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics 2009;124:1060-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kim C, Kim B, Joo N, Park Y, Lim H, Ju Y, et al. Determination of the BMI threshold that predicts cardiovascular risk and insulin resistance in late childhood. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010;88:307-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Klasson-Heggebo L, Andersen LB, Wennlof AH, Sardinha LB, Harro M, Froberg K, et al. Graded associations between cardiorespiratory fitness, fatness, and blood pressure in children and adolescents. Br J Sports Med 2006;40:25-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kovacs VA, Fajcsak Z, Gabor A, Martos E. School-based exercise program improves fitness, body composition and cardiovascular risk profile in overweight/obese children. Acta Physiol Hung 2009;96:337-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kriemler S, Zahner L, Schindler C, Meyer U, Hartmann T, Hebestreit H, et al. Effect of school based physical activity programme (KISS) on fitness and adiposity in primary schoolchildren: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010;340:c785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.McMurray RG, Harrell JS, Bangdiwala SI, Bradley CB, Deng S, Levine A. A school-based intervention can reduce body fat and blood pressure in young adolescents. J Adolesc Health 2002;31:125-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Raman A, Sharma S, Fitch MD, Fleming SE. Anthropometric correlates of lipoprotein profile and blood pressure in high BMI African American children. Acta Paediatr 2010;99:912-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Reed KE, Warburton DE, Macdonald HM, Naylor PJ, McKay HA. Action schools! BC: a school-based physical activity intervention designed to decrease cardiovascular disease risk factors in children. Prev Med 2008;46:525-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Resnicow K, Taylor R, Baskin M, McCarty F. Results of go girls: a weight control program for overweight African-American adolescent females. Obes Res 2005;13:1739-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ruiz JR, Ortega FB, Rizzo NS, Villa I, Hurtig-Wennlof A, Oja L, et al. High cardiovascular fitness is associated with low metabolic risk score in children: The European Youth Heart Study. Pediatr Res 2007;61:350-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sacher PM, Kolotourou M, Chadwick PM, Cole TJ, Lawson MS, Lucas A, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the MEND program: a family-based community intervention for childhood obesity. Obesity 2010;18:S62-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shalitin S, Ashkenazi-Hoffnung L, Yackobovitch-Gavan M, Nagelberg N, Karni Y, Hershkovitz E, et al. Effects of a twelve-week randomized intervention of exercise and/or diet on weight loss and weight maintenance, and other metabolic parameters in obese preadolescent children. Horm Res 2009;72:287-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Simon C, Schweitzer B, Oujaa M, Wagner A, Arveiler D, Triby E, et al. Successful overweight prevention in adolescents by increasing physical activity: a 4-year randomized controlled intervention. Int J Obes 2008;32:1489-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Steinberger J, Jacobs DR, Moran A, Hong CP, Rocchini AP, Prineas RJ, et al. Relation of insulin resistance and body composition to left ventricular mass in children. Am J Cardiol 2002;90:1177-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Vizcaíno VM, Salcedo Aguilar F, Franquelo Gutiérrez R, Solera Martínez M, Sánchez López M, Serrano Martínez S, et al. Assessment of an after-school physical activity program to prevent obesity among 9- to 10-year-old children: a cluster randomized trial. Int J Obes 2008;1:12-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yoshinaga M, Sameshima K, Tanaka Y, Arata M, Wada A, Takahashi H. Association between the number of cardiovascular risk factors and each risk factor level in elementary school children. Circ J 2008;72:1594-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Banach AM, Peralta-Huertas J, Livingstone K, Petrella N, Klentrou P, Faught B, et al. Arterial distensibility is reduced in overweight pre- and early pubescent children. Eur J Pediatr 2010;169:695-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Barba G, Troiano E, Russo P, Strazzullo P, Siani A. Body mass, fat distribution and blood pressure in southern Italian children: results of the ARCA project. Nutr Metab Carbiovasc Dis 2006;16:239-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Calcaterra V, Klersy C, Muratori T, Telli S, Caramagna C, Scaglia F, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome (MS) in children and adolescents with varying degrees of obesity. Clin Endocrinol 2008;68:868-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Csabi G, Torok K, Jeges S, Molnar D. Presence of metabolic cardiovascular syndrome in obese children. Eur J Pediatr 2000;159:91-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.De Sousa G, Hussein A, Trowitzsch E, Andler W, Reinehr T. Hemodynamic responses to exercise in obese children and adolescents before and after overweight reduction. Klinische Padiatr 2009;221:237-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Di Salvo G, Pacileo G, Del Giudice EM, Natale F, Limongelli G, Verrengia M, et al. Abnormal myocardial deformation properties in obese, non-hypertensive children: an ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, standard echocardiographic, and strain rate imaging study. Eur Heart J 2006;27:2689-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Di Salvo G, Pacilco G, Del Giudice EM, Natale F, Limongelli G, Verrengia M, et al. Atrial myocardial deformation properties in obese nonhypertensive children. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2008;21:151-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Farpour-Lambert NJ, Aggoun Y, Marchand LM, Martin XE, Herrmann FR, Beghetti M. Physical activity reduces systemic blood pressure and improves early markers of atherosclerosis in pre-pubertal obese children. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:2396-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hrafnkelsson H, Magnusson KT, Sigurdsson EL, Johannsson E. Association of BMI and fasting insulin with cardiovascular disease risk factors in seven-year-old Icelandic children. Scand J Prim Health Care 2009;27:186-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Iannuzzi A, Licenziati MR, Acampora C, Salvatore V, Auriemma L, Romano ML, et al. Increased carotid intima-media thickness and stiffness in obese children. Diabetes Care 2004. a;27:2506-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 108.Iannuzzi A, Licenziati MR, Acampora C, Salvatore V, De Marco D, Mayer MC, et al. Preclinical changes in the mechanical properties of abdominal aorta in obese children. Metabolism 2004. b;53:1243-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 109.Maggio ABR, Aggoun Y, Marchand LM, Martin XE, Herrmann F, Beghett M, et al. Associations among obesity, blood pressure, and left ventricular mass. J Pediatr 2008;152:489-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Peralta-Huertas J, Livingstone K, Banach A, Klentrou P, O’Leary D. Differences in left ventricular mass between overweight and normal-weight preadolescent children. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2008;33:1172-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Van Putte-Katier N, Rooman RP, Haas L, Verhulst SL, Desager KN, Ramet J, et al. Early cardiac abnormalities in obese children: importance of obesity per se versus associated cardiovascular risk factors. Pediatr Res 2008;64:205-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Watts K, Bell LM, Byrne SM, Jones TW, Davis EA. Waist circumference predicts cardiovascular risk in young Australian children. J Paediatr Child Health 2008;44:709-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Woo KS, Chook P, Yu CW, Sung RYT, Qiao M, Leung SSF, et al. Overweight in children is associated with arterial endothelial dysfunction and intima-media thickening. Int J Obes 2004b;28:852-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web appendix: Supplementary material (web appendices 1-4)