Abstract

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) is a DNA polymerase that increases the repertoire of antigen receptors by adding non-templated nucleotides (N-addition) to V(D)J recombination junctions. Despite extensive in vitro studies on TdT catalytic activity, the partners of TdT that enable N-addition remain to be defined. Using an intrachromosomal substrate, we show here that, in Chinese hamter ovary (CHO) cells, ectopic expression of TdT efficiently promotes N-additions at the junction of chromosomal double-strand breaks (DSBs) generated by the meganuclease I-SceI and that the size of the N-additions is comparable with that at V(D)J junctions. Importantly, no N-addition was observed in KU80- or XRCC4-deficient cells. These data show that, in a chromosomal context of non-lymphoid cells, TdT is actually able to promote N-addition at non-V(D)J DSBs, through a process that strictly requires the components of the canonical non-homologous end-joining pathway, KU80 and XRCC4.

INTRODUCTION

The maintenance of genetic stability requires the faithful repair of DNA. However, fundamental processes, such as the generation of the immune repertoire, require genetic variability. Notably, to generate an efficient immune repertoire, V(D)J recombination favors genetic diversity at two levels.

The first level of diversity corresponds to a recombinational diversity and is created by the rearrangement of variable (V), diversity (D) and joining (J) Ig and T-cell receptor (TCR) gene segments. The lymphoid-specific components of the recombination machinery, RAG1 and RAG2, generate two DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) at recombination signal sequences that are adjacent to the V, D and J coding segments (1). Subsequently, the joining of the DNA ends is processed by the non-lymphoid-restricted components of non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) (2,3).

NHEJ is a major DSB repair mechanism, which is not specific of DSBs generated by the V(D)J recombination process, thus it can occur all along the genome. DNA ends are recognized by the KU80/KU70 heterodimer, the catalytic subunit DNA-PKCS and Artemis. Then, recruitment of the XRCC4-Cernunos/Xlf-ligaseIV complex enables DNA end ligation (4). Alternatively to the canonical KU-ligaseIV NHEJ pathway (C-NHEJ), a highly error-prone KU- and XRCC4-independent end-joining process (alternative end-joining (A-EJ)) that leads to deletions at the re-sealed junction has recently emerged (5–11).

In addition to recombinational diversity, junctional diversity is used during V(D)J recombination. This second level of diversity during V(D)J recombination is characterized by a particular joining mechanism of coding segments characterized by the loss of nucleotides and the addition of extra nucleotides, adding thus junctional diversity. Two distinct mechanisms operate to generate variability at V(D)J junctions: the cleavage of hairpin intermediates, resulting in P (palindromic) nucleotides (12) and the addition of N (non-templated) nucleotides by the lymphocyte-specific terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) (13,14).

TdT, which belongs to the Pol X family of polymerases (15), randomly adds nucleotides to 3′-ends (16,17). N-nucleotides are present at >70% of junctions at the TCR and Ig loci (18,19). In TdT-deficient mice, N-additions at coding joints are rare (20), but in mice constitutively expressing TdT, N-additions are observed even in light chains (21).

Despite extensive in vitro studies on TdT catalytic activity (22–24), the partners of TdT that enable N-additions remain to be defined. In vitro studies have suggested that TdT does not require any other factor to add nucleotides at 3′OH ends (25). However, the absence of N-additions in the rare coding joints of KU80-deficient mice suggests that this NHEJ factor is necessary for TdT recruitment to DNA ends or for its activation (26). Consistent with this observation, using an episomal V(D)J substrate, Purugganan et al. (27) have shown an absence of N-additions in a KU-deficient CHO cell line in which TdT was ectopically expressed. In contrast, a more recent study shows that TdT promotes N-additions in a KU-independent manner on an episomal non-V(D)J substrate (28). Moreover, the additions were abnormally long in the absence of KU80 (11–27 nt compared with 1–5 nt in wild-type cells), leading the authors to suggest that N-addition promoted by TdT is KU-dependent at V(D)J but not at non-V(D)J DSBs (28). This conclusion implies that, at non-V(D)J DSBs, TdT might be active on intermediates generated by an alternative end-joining (A-EJ) process. However, an alternative hypothesis could be that, with non-V(D)J substrates, the KU dependency of TdT is actually different at episomal plasmid versus chromosomal breaks. Indeed, the role of KU on the activity of TdT at non-V(D)J sites has not been addressed in a chromosomal context.

To address the question of the requirement of cannonical (C-NHEJ) components for TdT-mediated N-addition at non-(V)D)J chromosomal DSBs, we used a strategy that allowed us to analyze the repair of DSBs generated by the meganuclease I-SceI (a non-V(D)J DSB) in a chromosomal context. Moreover, this substrate monitors both C-NHEJ and A-EJ (7,8). This substrate was chromosomally integrated in KU- or XRCC4-deficient hamster cells. Indeed, although many studies in KU80-deficient mice have shown that the KU proteins are involved in TdT-mediated N-additions at V(D)J junctions, few in vivo studies have addressed the relationship between TdT and XRCC4 because the knockout of XRCC4 is embryonic lethal in mice (29). However, the association between TdT and XRCC4/LigaseIV has been reported in vitro (30,31), prompting the study of the involvement of XRCC4 in N-additions by TdT. Of note, KU and XRCC4 might behave differently, since we have previously shown with our substrates that defects in KU80 or XRCC4 differentially affected the efficiency of the end-joining process (8).

Our results show that, upon ectopic expression of TdT in non lymphoid CHO cells, N-nucleotides are efficiently added to I-SceI DSBs in a chromosomal context, and the size of the N-additions is comparable to that at V(D)J junctions. This process is dependent on both KU80 and XRCC4, two essential components of the canonical NHEJ pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and transfection

XR-1 cell lines and their derivatives were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (without pyruvate); CHO-K1, xrs6 and their derivatives were cultured in Minimum essential Medium Eagle-alpha Modification (α-MEM) supplemented with 10% Fetal calf Serum (FCS), 2 mM glutamine and 200 IU/ml penicillin at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cells (2 × 105 for xrs6 and 3 × 105 for XR-1) were plated 1 day before transfection with polyethylenimine derivative (Jet-PEI), which was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Polyplus-Transfection, Illkirch, France). KU-deficient cells and the corresponding control cell lines were transfected with (i) 10 × 10−13 moles empty vector pBL99 for mock experiments; (ii) 2.5 × 10−13 moles of empty vector and 7.5 × 10−13 moles of the I-SceI expression vector pCMV-I-SceI (32) or (iii) 7.5 × 10−13 moles of pCMV-I-SceI and 2.5 × 10−13 moles of the TdT expression vector pCMV-TdT (33). XRCC4-deficient cells were transfected with (i) 10 × 10−13 moles of empty vector; (ii) 2.5 × 10−13 moles of empty vector and 7.5 × 10−13 moles of pCMV-I-SceI; (iii) 1.25 × 10−13 moles of empty vector, 7.5 × 10−13 moles of pCMV-I-SceI and 1.25 × 10−13 moles of pCMV-TdT; (iv) 1.25 × 10−13 moles of empty vector, 7.5 × 10−13 moles of pCMV-I-SceI and 1.25 × 10−13 moles of the XRCC4 expression vector for complementation experiments or (v) 7.5 × 10−13 moles of pCMV-I-SceI, 1.25 × 10−13 moles of TdT and 1.25 × 10−13 moles of the XRCC4 expression vector.

Enrichment of CD4+ cells

At 72 hours after transfection, the cells were dissociated in phosphate buffered saline (PBS)/50 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and washed with PBS (without Ca2+ or Mg2+)/0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA)/2 mM EDTA. A total of 1 × 107 cells were stained for 15 min with 1.5 μg of anti-CD4-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC). Enrichment for CD4+ cells was performed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS; FITC-positive cells).

Immunofluorescence

At 48 hours after transfection, cells on coverslips were washed in PBS and fixed with PBS/2% PAF for 15 min at room temperature. After 10 min of permeabilization with PBS/0.5% saponin and a saturation step with PBS/0.5% saponin/0.2% BSA for 30 min, the cells were incubated for 1 hour with polyclonal rabbit TdT antibody (Abcam, ab14772) and monoclonal mouse anti-hyaluronic acid antibody (Covance) for the detection of I-SceI. Both of the antibodies were diluted 1/250 in PBS/0.5% saponin/0.2% BSA. The cells were washed with PBS/0.1% saponin and then incubated for 1 hour with secondary antibodies diluted 1/400 in PBS/0.5% saponin/0.2% BSA. After a washing step with PBS/0.1% saponin, the cells were stained with 4′, 6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and mounted under coverslips.

Junction sequence analysis

The manipulations were performed as previously described (7–9).

Statistical analysis

The number of junctions exhibiting deletions or N-additions in presence versus absence of TdT was compared using non-parametric Mann–Whitney test, and P-values were calculated using the GraphPad Prism software.

RESULTS

Cell lines and strategy

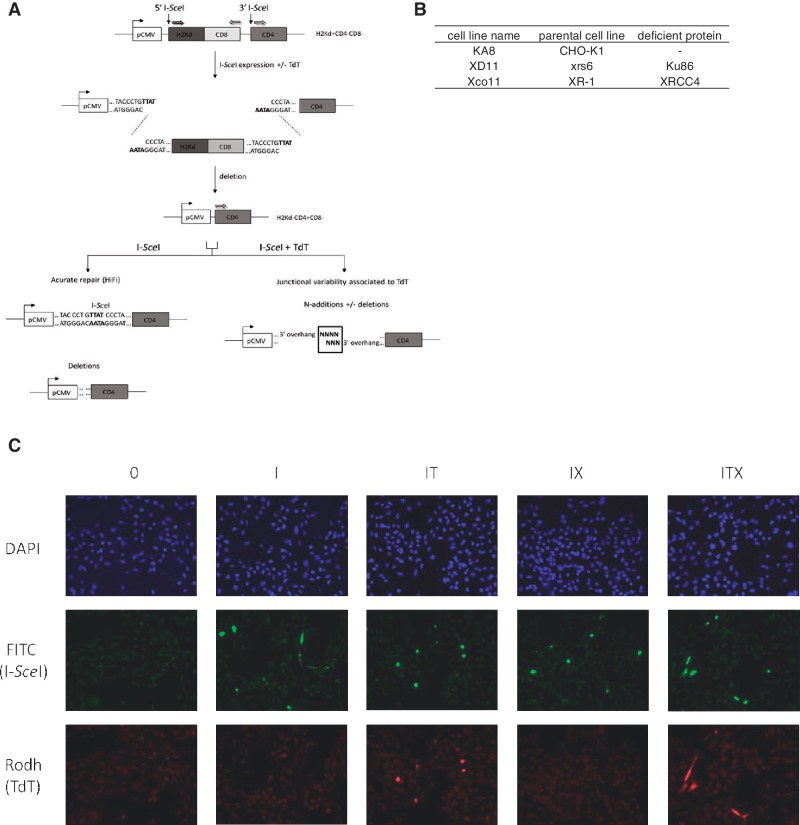

To analyze the junctional variability associated with TdT in a non-V(D)J chromosomal context, we used the substrate depicted in Figure 1A, stably integrated as a single copy in the genome of wild-type CHO-K1, NHEJ mutant, xrs6 (KU80-defective) or XR-1 (XRCC4-defective) hamster cells. The different cell lines used are indicated in Figure 1B and were described previously (7,8). This substrate monitors chromosomal NHEJ: the reporter genes H2Kd and CD4 encode membrane antigens, but in the absence of expression of the meganuclease I-SceI, CD4 is not expressed; two I-SceI cleavage sites flank the fragment containing H2Kd and after cleavage by I-SceI, rejoining of the DNA ends leads to the excision of the internal H2-Kd fragment and the expression of CD4. These events can be measured by FACS or fluorescence microscopy, and the resealed junctions can be amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and sequenced. Using this substrate, we previously characterized in living cells the A-EJ pathway in a chromosomal context, which systematically involves deletions (>4 nt) at junctions frequently associated with the use of microhomologies distant from the DNA ends. C-NHEJ (KU/XRCC4-dependent) uses the 3′-protruding nucleotides (3′-Pnt) generated by I-SceI cleavage, either with perfect annealing (with fully complementary ends, resulting in error-free repair or HiFi) or imperfect annealing of the 3′-Pnt resulting in short insertions or deletions of 1, 2 or 3 nucleotides (summarized in Supplementary Information S1). A-EJ (KU/XRCC4-independent) is highly error-prone and deletes at least the four 3′-Pnt (usually more); the re-sealing is thus accompanied by deletions of four or more nucleotides (summarized in Supplementary Information S1) (7–9). The cleavage of I-SceI sites generates 3′ overhangs to which TdT might be able to add N-nucleotides. The re-sealing pattern was analyzed in CD4+ cells, in which we know that an end-joining event must have occurred.

Figure 1.

Intrachromosomal substrates (A) and cell lines used (B). (A) The mouse cell surface antigens H2kd and CD4 were used as reporter genes. In the parental configuration, H2 is expressed under the control of the CMV promoter, but CD4 is not expressed because it is located too far from the promoter. The cleavage of the I-SceI sites generates 3′ overhangs to which TdT should be able to add N-nucleotides. The excision of the H2kd fragment followed by the joining of the two distant ends places CD4 under CMV promoter control. CD4 expression is monitored with FACS analysis (7). The re-sealing pattern of the junctions in CD4+ cells (i.e. in cells in which an end-joining event actually occurred) is then analyzed after PCR amplification using a set of primers specific for the CD4 sequence and the CMV promoter. (B) The cell lines used were described previously (8). (C) TdT and I-SceI expression in XRCC4-deficient cells. Cells were transfected with an empty vector (0) or with a combination of I-SceI (I), TdT (T) and XRCC4 cDNA (X) expression vectors. A high frequency of co-localization of TdT and I-SceI was detected with immunofluorescence in XRCC4-deficient cells (IT) and XRCC4-complemented cells (ITX). These results are representative of observations in wild-type and KU-deficient cells.

The cells were co-transfected with an expression vector encoding I-SceI and with either a TdT-encoding expression vector or an empty expression vector (control). Immunofluorescence staining showed that most cells expressing I-SceI also expressed TdT (Figure 1C). The high efficiency of co-transfection with I-SceI and TdT expression vectors allows the investigation of the potential effect of TdT on junctional variability.

Sequence analysis of the repair junctions in CD4+ cells allowed us to determine the effect of TdT at the nucleotide level (Figures 2–5).

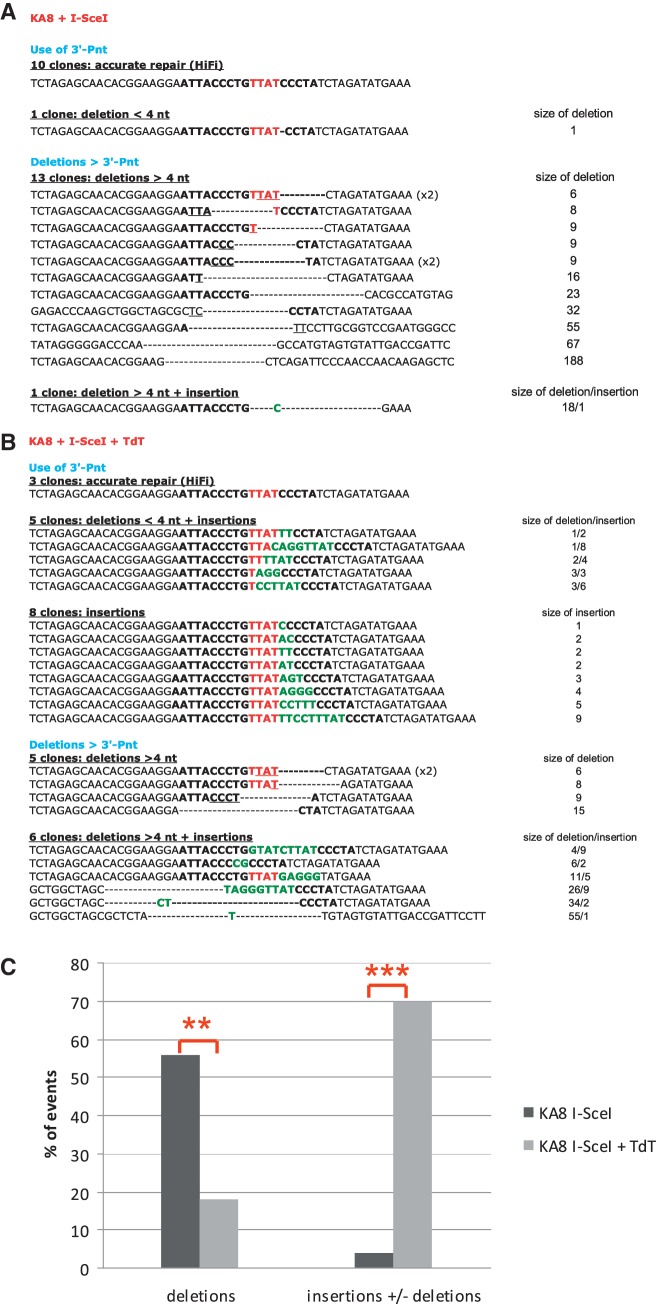

Figure 2.

Sequence analysis of the junctions in wild-type cells. (A) Junction sequences from cells transfected with only the I-SceI expression vector. (B) Junction sequences from cells transfected with both the I-SceI and the TdT expression vectors. The nucleotides of the I-SceI sites are in bold, and the 4 nt that constitute the 3′ overhangs (the four 3′P-nt after the breaks) are indicated in red. The nucleotides involved in microhomology annealing are underlined. Extra-nucleotides added at the junction are in green. Parentheses indicate the number of identical sequences. (C) Frequencies of junctions with deletions and/or N-additions. P-values for deletions and N-additions in presence versus absence of TdT are indicated in the text and Table 1. **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001.

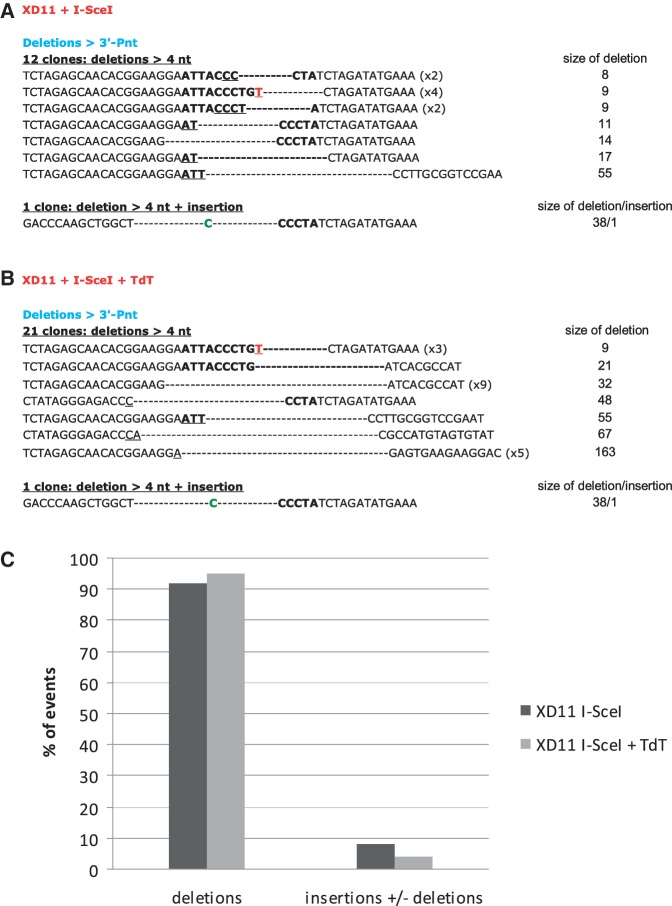

Figure 3.

Sequence analysis of the junctions in KU-deficient cells. (A) Junction sequences from cells transfected with only the I-SceI expression vector. (B) Junction sequences from cells transfected with both the I-SceI and the TdT expression vectors. The nucleotides of the I-SceI sites are in bold, and the 4 nt that constitute the 3′ overhangs (the four 3′P-nt after the breaks) are indicated in red. The nucleotides involved in microhomology annealing are underlined. Extra-nucleotides added at the junction are in green. Parentheses indicate the number of identical sequences. (C) Frequencies of junctions with deletions and/or N-additions. P-values for N-additions in presence versus absence of TdT are indicated in the text and Table 1.

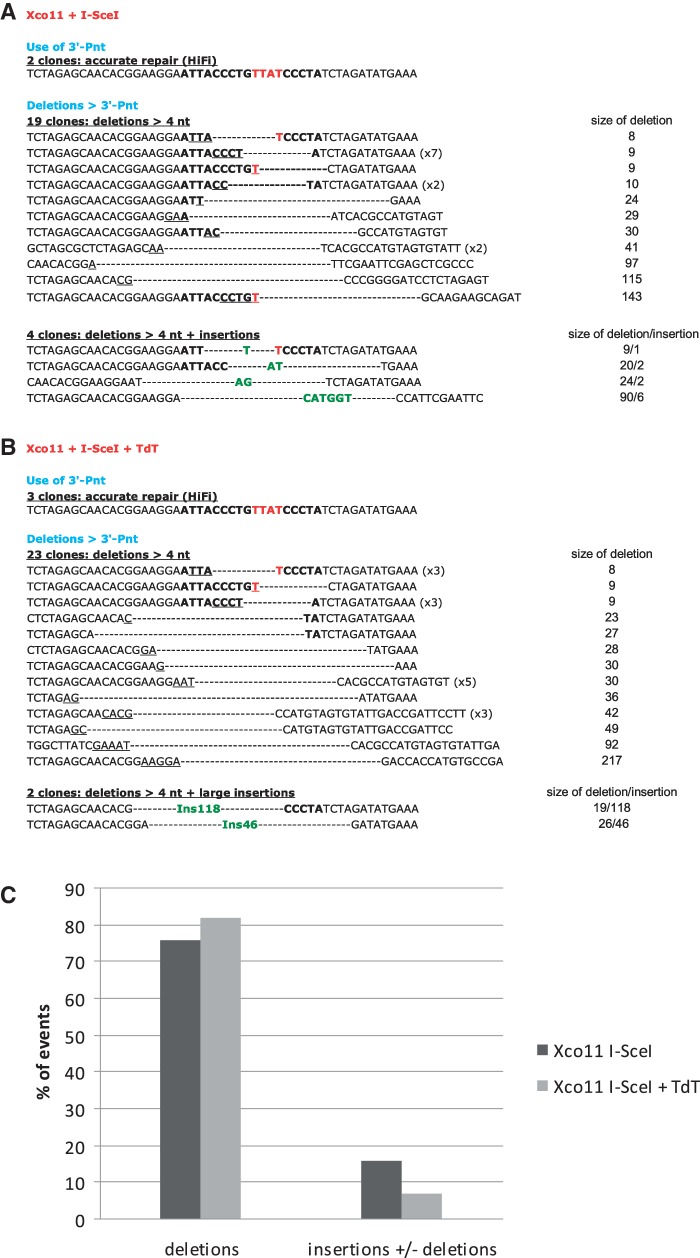

Figure 4.

Sequence analysis of the junctions in XRCC4-deficient cells (A) Junction sequences from cells transfected with only the I-SceI expression vector. (B) Junction sequences from cells transfected with both the I-SceI and the TdT expression vectors. The nucleotides of the I-SceI sites are in bold, and the 4 nt that constitute the 3′ overhangs (the four 3′P-nt after the breaks) are indicated in red. The nucleotides involved in microhomology annealing are underlined. Extra-nucleotides added at the junction are in green. Parentheses indicate the number of identical sequences. (C) Frequencies of junctions with deletions and/or N-additions. P-values for N-additions in presence versus absence of TdT are indicated in the text and Table 1.

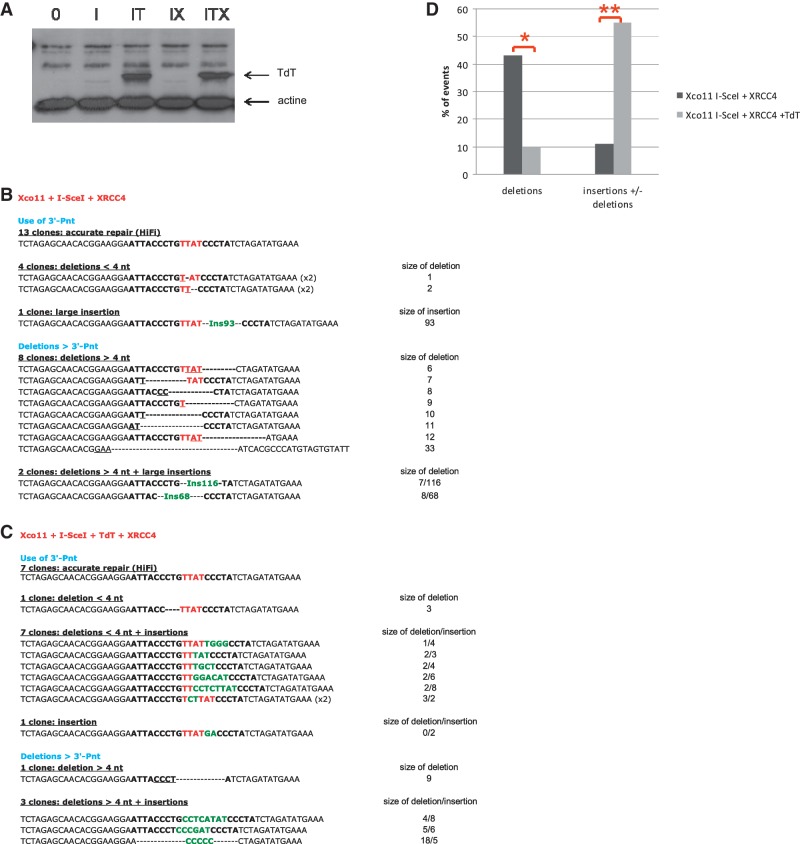

Figure 5.

Sequence analysis of the junctions in XRCC4-complemented cells. (A) Western blot showing the level of TdT expression in XRCC4-deficient cells and complemented cells. I: I-SceI; IT: I-SceI + TdT; IX: I-SceI + XRCC4; ITX: I-SceI + XRCC4 + TdT. (B) Junction sequences from cells transfected with only the I-SceI expression vector. (C) Junction sequences from cells transfected with both the I-SceI and the TdT expression vectors. The nucleotides of the I-SceI sites are in bold, and the 4 nt that constitute the 3′ overhangs (the four 3′P-nt after the breaks) are indicated in red. The nucleotides involved in microhomology annealing are underlined. Extra-nucleotides added at the junction are in green. Parentheses indicate the number of identical sequences. (D) Frequencies of junctions with deletions and/or N-additions. P-values for N-additions in presence versus absence of TdT are indicated in the text and Table 1. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01.

TdT efficiently adds N-nucleotides at I-SceI-chromosomal DSBs

Interestingly, in wild-type cells, the frequency of error-free events substantially dropped from 40% to 11% upon TdT addition (HiFi junctions, Table 1 and Figure 2, P = 0.0179), with 70% of the junctions exhibiting extra-nucleotides (Figure 2B and 2C, Table 1, P < 0.0001), a frequency similar to that observed at TCR and Ig loci (18,19). Moreover, the mean size of the N-additions was ∼4 nt, which is similar to the size of the N-additions at V(D)J junctions.

Table 1.

Summary of analysis of end-joining junctions in the different cell lines in presence and absence of TdT

| Transfection condition |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I-SceIa |

I-SceI + TdTb |

I-SceI versus I-SceI + TdT | |||||

| HiFi junctionsc | Non-HiFi junctions with extra-nucleotidesd | HiFi junctionsc | Non-HiFi junctions with extra-nucleotidesd | P-values for Non-HiFi junctions with extra-nucleotides | |||

| Cell line | Total sequences | (%) | (%) | Total sequences | (%) | (%) | |

| KA8 (wild-type) | 25 | 10 (40) | 1 (4) | 27 | 3 (11) | 19 (70) | <0.0001 |

| XD11 (Ku-deficient) | 13 | 0 | 1 (8) | 22 | 0 | 1 (5) | =0.7342 |

| Xco11 (XRCC4-deficient) | 25 | 2 (8) | 4 (16) | 28 | 3 (11) | 2 (7) | =0.3222 |

| Xco11 + XRCC4 cDNA | 28 | 13 (46) | 3 (11) | 20 | 7 (35) | 11(55) | =0.0010 |

cHiFi junctions refer to accurate repair events (HiFi, high fidelity).

dExtra-nucleotides refer to N-additions (from 1 to 9 nt) and insertions of DNA sequences (≥46 bp) that are likely DNA capture events.

Importantly, in the majority of cases (70%), N-additions conserve all or part of the four 3′-Pnt of the site cleaved by I-SceI (Figure 2B), which is a hallmark of the KU/XRCC4 pathway (7,8).

Finally, the presence of TdT significantly reduces the extent of deletions at the re-sealed junctions (P = 0.0018). Indeed, the mean size of deletions at junctions was reduced from 30 nt in the absence of TdT to 9 nt when TdT was expressed (Figure 2A and B). A limited deletion size is also a hallmark of the KU-NHEJ pathway (7,8).

Taken together, these data (i) show that TdT can promote N-additions at I-SceI-DSBs in a chromosomal context (producing N-additions with similar sizes to those observed at V(D)J junctions) and (ii) suggest the involvement of the canonical NHEJ pathway in this N-addition. To directly validate the second conclusion, we analyzed the effect of TdT in KU80- or XRCC4-deficient cells.

N-nucleotide addition at I-SceI-chromosomal DSBs is KU80/XRCC4-dependent

In the absence of KU80, the frequency of accurate events is completely abolished (Table 1), consistent with our previous observations (7,8).

Importantly, in contrast to a study based on an episomal plasmid assay (28), in a chromosomal context, we found no N-additions in KU-deficient cells after TdT addition (Figure 3B and C), except for one event out of 23 junctions (Figure 3B), which is likely to be TdT-independent because it was also observed in cells without TdT (Figure 3A, Table 1, P = 0.7342). Taken together, these data show that N-addition at intrachromosomal I-SceI-DSBs is largely KU80-dependent.

Similarly, we then tested the effect of XRCC4, the ligase IV co-factor that acts at the last step of C-NHEJ. As previously described (8), a deficiency in XRCC4 strongly affected the accuracy of end-joining: only 8% of junctions were accurately repaired compared with 40% in wild-type cells (Table 1).

Importantly, as observed in KU-deficient cells, TdT did not promote N-addition in XRCC4-deficient cells (Figure 4, Table 1, P = 0.3222). To assess the XRCC4 dependency of TdT-mediated N-addition, cells were co-transfected with TdT and XRCC4 expression vectors. At similar expression level of TdT (Fig. 5A), N-additions were performed only in XRCC4-complemented cells (Figure 5B–D). The frequency of N-additions increases from 0% (Figure 5B) to 55% (Figure 5C) upon the expression of TdT in XRCC4-complemented cells (Table 1, P = 0.001), and the mean size of N-additions was ∼5 nt, similar to what we observed in wild-type cells. Taken together, the present data show that, in a chromosomal context, N-addition by TdT at an I-Sce-I-DSB is KU- and XRCC4-dependent.

DISCUSSION

Our data show that TdT can promote N-addition at a non-V(D)J DSB in a chromosomal context. This result is consistent with the abnormal N-additions observed in Ig light chain genes (21) and in loci outside V(D)J regions in B and T cells expressing TdT (34,35). Interestingly, although the DSBs generated by the meganuclease I-SceI in this study are located in non-coding sequences in contrast with V(D)J junctions, the size of the N-additions is comparable in both situations. This result suggests that the same mechanistic constraints involving the KU complex limit the size of N-additions in both contexts (I-SceI versus RAG-induced DSBs).

Our study also shows that TdT is efficient in non-lymphoid cells, which means that TdT does not need any lymphoid-specific factor to be recruited and act at non-V(D)J chromosome ends. Moreover, TdT can act independently of RAG1-RAG2 in a chromosomal context, suggesting that TdT performs N-additions at a post-synapsis cleavage step during V(D)J recombination.

Finally, we show that the effect of TdT on non-V(D)J DSBs is strictly dependent on the KU/XRCC4 pathway. Indeed, in the absence of KU80 or XRCC4, no N-addition events were observed: either TdT is not recruited or is unstable at the DSB, or the nucleotides that were newly added by A-EJ were lost after resolution of the molecular intermediates.

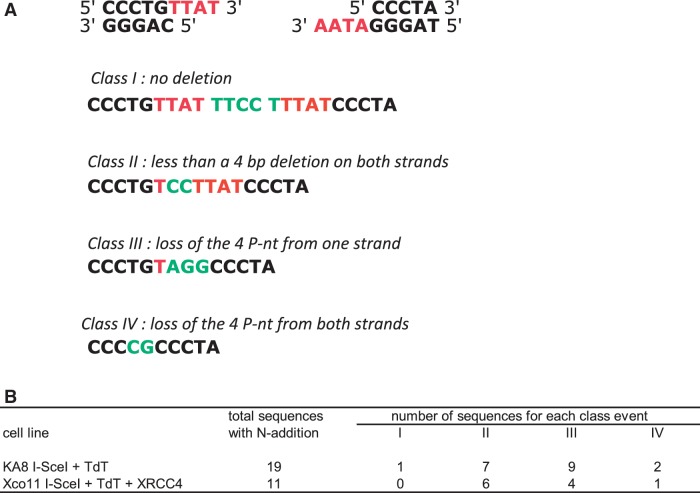

The requirement for KU80 and XRCC4 is consistent with the result that, in wild-type cells, the 3′-Pnt generated by I-SceI cleavage are maintained in most of the events involving N-additions (at least in part). Indeed, the use of the 3′-Pnt is a hallmark of the canonical KU/XRCC4-dependent NHEJ pathway, and the canonical KU80/XRCC4 NHEJ pathway is highly efficient, even with mismatched ends (7–9). In the absence of DNA degradation, nucleotide addition at both DNA ends prior to ligation should result in duplication of the 3′-Pnt interrupted by the N-additions (see example in Figure 6A, class I). Although such events can occur (Figure 6B, 1 event in wild-type cells), most of the N-addition events show the maintenance of between one and four of the 3′-Pnt for at least one of the ends (Figure 6, classes II and III). Moreover, the requirement of XRCC4 for N-additions strongly supports the idea that ligase IV is necessary and cannot be replaced by another ligase; thus, that N-additions require the entire C-NHEJ process, from the early steps (KU80) to the late steps (XRCC4).

Figure 6.

Junction patterns after N-nt addition by TdT. The 4 P-nt insertions generated by the meganuclease I-SceI at both sites are indicated in red, and the N-nucleotides added by TdT are indicated in green. Four classes of junctions with N-addition are depicted in (A). Their pattern of distribution in wild-type and XRCC4-complemented cells are indicated in (B).

Our data contrast with the results of plasmid end-joining assays showing frequent abnormally long nucleotide insertions in the presence of TdT in KU-deficient cells (28). However, discrepancies between plasmid-based assays and chromosomal substrates are common. Indeed, it has already been shown for V(D)J substrates that the average length of N-nucleotides added by TdT is smaller for chromosomal substrates than for episomal substrates (23). Likewise, in the same cell lines used here, the precise rejoining of DNA ends is not impaired in KU80- or XRCC4-deficient cells with a plasmid substrate (36), whereas it is strongly affected at the chromosomal level (ref 7,8 and present data). These differences likely reflect chromatin regulation and general chromosome structure/dynamic constraints and highlight the importance of analyzing DSB repair in a chromosomal context.

The cell lines used here show that TdT is potentially active in different tissues and can act on enzyme-generated DSBs other than V(D)J recombination intermediates. TdT, the physiological role of which is to increase the diversity of the immune repertoire by adding non-templated nucleotide to V(D)J junctions, could represent a potential mutagenic risk at other DSBs, thus implying the necessity of the tight regulation of its expression. Indeed, TdT expression is restricted to specific cells (immature pre-B and pre-T lymphoid cells) and to a short window of time (the G1 phase of the cell cycle during which IgH and TCR gene rearrangement occurs). However, the good health of our transgenic mice constitutively expressing TdT (21) suggests that an aberrant expression of TdT would promote limited genome variability without threatening genome stability, consistently with our finding showing the involvement of the canonical NHEJ pathway, which protects against genome rearrangements (37–39), to add N-nucleotides to non-V(D)J DSBs.

Interestingly, our data should have promising applications. Indeed, several strategies are in development to generate targeted DSBs using meganucleases, zinc finger nucleases or Transcription Activation-like Effector (TALENs) nucleases to increase the efficiency of gene targeting (40–42). Alternatively, identifying unfaithful end-joining at targeted DSBs allows for the selection of mutants. However, one can object that this strategy is mainly based on A-EJ-mediated events and that (i) A-EJ is accompanied by uncontrolled resection at the repaired junctions; (ii) A-EJ favors translocations (11,37,38,43–45) and risks generating genetic instability and (iii) in wild-type cells, A-EJ is less efficient than C-NHEJ (7,8). For all of these reasons, C-NHEJ appears to be preferable, providing that variability can be introduced at the junction. The present data show that TdT is capable of generating variability at a C-NHEJ junction and would be a useful tool, in combination with specific nucleases, to generate targeted mutations in mammalian cells with minimal risk of genomic instability.

In conclusion, this study underlines the subtle regulation of N-addition by TdT to allow genetic diversity in association with the DNA repair processes involved in genome stability maintenance, a feature that has promising applications for genome modifications and functional studies.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online: Supplementary Information 1.

FUNDING

Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer [SL220100601353]. Institut National du cancer (INCa). Ligue Régionale contre le Cancer, comité Ile-de-France (to P.B.). Funding for open access charge: Institut Gustave Roussy.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr M. Jasin for providing the I-SceI expression vector. We are grateful to Drs Jan Baijer and Nathalie Déchamps from the Flow Cytometry Platform (CEA) for their help in cell sorting.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jung D, Alt FW. Unraveling V(D)J recombination; insights into gene regulation. Cell. 2004;116:299–311. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rooney S, Chaudhuri J, Alt FW. The role of the non-homologous end-joining pathway in lymphocyte development. Immunol. Rev. 2004;200:115–131. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lieber MR, Ma Y, Pannicke U, Schwarz K. The mechanism of vertebrate nonhomologous DNA end joining and its role in V(D)J recombination. DNA Repair. 2004;3:817–826. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lieber MR. The mechanism of double-strand DNA break repair by the nonhomologous DNA end-joining pathway. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2010;79:181–211. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.093131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corneo B, Wendland RL, Deriano L, Cui X, Klein IA, Wong SY, Arnal S, Holub AJ, Weller GR, Pancake BA, et al. Rag mutations reveal robust alternative end joining. Nature. 2007;449:483–486. doi: 10.1038/nature06168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennardo N, Cheng A, Huang N, Stark JM. Alternative-NHEJ is a mechanistically distinct pathway of mammalian chromosome break repair. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guirouilh-Barbat J, Huck S, Bertrand P, Pirzio L, Desmaze C, Sabatier L, Lopez BS. Impact of the KU80 pathway on NHEJ-induced genome rearrangements in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. 2004;14:611–623. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guirouilh-Barbat J, Rass E, Plo I, Bertrand P, Lopez BS. Defects in XRCC4 and KU80 differentially affect the joining of distal nonhomologous ends. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:20902–20907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708541104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rass E, Grabarz A, Plo I, Gautier J, Bertrand P, Lopez BS. Role of Mre11 in chromosomal nonhomologous end joining in mammalian cells. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:819–824. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soulas-Sprauel P, Le Guyader G, Rivera-Munoz P, Abramowski V, Olivier-Martin C, Goujet-Zalc C, Charneau P, de Villartay JP. Role for DNA repair factor XRCC4 in immunoglobulin class switch recombination. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:1717–1727. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan CT, Boboila C, Souza EK, Franco S, Hickernell TR, Murphy M, Gumaste S, Geyer M, Zarrin AA, Manis JP, et al. IgH class switching and translocations use a robust non-classical end-joining pathway. Nature. 2007;449:478–482. doi: 10.1038/nature06020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis SM. P nucleotide insertions and the resolution of hairpin DNA structures in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:1332–1336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benedict CL, Gilfillan S, Thai TH, Kearney JF. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase and repertoire development. Immunol. Rev. 2000;175:150–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desiderio SV, Yancopoulos GD, Paskind M, Thomas E, Boss MA, Landau N, Alt FW, Baltimore D. Insertion of N regions into heavy-chain genes is correlated with expression of terminal deoxytransferase in B cells. Nature. 1984;311:752–755. doi: 10.1038/311752a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nick McElhinny SA, Ramsden DA. Sibling rivalry: competition between Pol X family members in V(D)J recombination and general double strand break repair. Immunol. Rev. 2004;200:156–164. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bollum FJ. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase: biological studies. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas. Mol. Biol. 1978;47:347–374. doi: 10.1002/9780470122921.ch6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kato KI, Goncalves JM, Houts GE, Bollum FJ. Deoxynucleotide-polymerizing enzymes of calf thymus gland. II. Properties of the terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 1967;242:2780–2789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwasato T, Yamagishi H. Novel excision products of T cell receptor gamma gene rearrangements and developmental stage specificity implied by the frequency of nucleotide insertions at signal joints. Eur. J. Immunol. 1992;22:101–106. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimizu T, Yamagishi H. Biased reading frames of pre-existing DH–JH coding joints and preferential nucleotide insertions at VH–DJH signal joints of excision products of immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rearrangements. EMBO. J. 1992;11:4869–4875. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05593.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Komori T, Okada A, Stewart V, Alt FW. Lack of N regions in antigen receptor variable region genes of TdT-deficient lymphocytes. Science. 1993;261:1171–1175. doi: 10.1126/science.8356451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bentolila LA, Wu GE, Nourrit F, Fanton d’Andon M, Rougeon F, Doyen N. Constitutive expression of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase in transgenic mice is sufficient for N region diversity to occur at any Ig locus throughout B cell differentiation. J. Immunol. 1997;158:715–723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson RS, Bollum FJ, Beattie KL. Pyrophosphorolytic dismutation of oligodeoxy-nucleotides by terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3190–3196. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.15.3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Repasky JA, Corbett E, Boboila C, Schatz DG. Mutational analysis of terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated N-nucleotide addition in V(D)J recombination. J. Immunol. 2004;172:5478–5488. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Motea EA, Berdis AJ. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase: the story of a misguided DNA polymerase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1804:1151–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robbins DJ, Coleman MS. Initiator role of double stranded DNA in terminal transferase catalyzed polymerization reactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:2943–2957. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.7.2943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bogue MA, Wang C, Zhu C, Roth DB. V(D)J recombination in Ku86-deficient mice: distinct effects on coding, signal, and hybrid joint formation. Immunity. 1997;7:37–47. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80508-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Purugganan MM, Shah S, Kearney JF, Roth DB. Ku80 is required for addition of N nucleotides to V(D)J recombination junctions by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:1638–1646. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.7.1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandor Z, Calicchio ML, Sargent RG, Roth DB, Wilson JH. Distinct requirements for Ku in N nucleotide addition at V(D)J- and non-V(D)J-generated double-strand breaks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1866–1873. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao Y, Ferguson DO, Xie W, Manis JP, Sekiguchi J, Frank KM, Chaudhuri J, Horner J, DePinho RA, Alt FW. Interplay of p53 and DNA-repair protein XRCC4 in tumorigenesis, genomic stability and development. Nature. 2000;404:897–900. doi: 10.1038/35009138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma Y, Lu H, Tippin B, Goodman MF, Shimazaki N, Koiwai O, Hsieh CL, Schwarz K, Lieber MR. A biochemically defined system for mammalian nonhomologous DNA end joining. Mol. Cell. 2004;16:701–713. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahajan KN, Nick McElhinny SA, Mitchell BS, Ramsden DA. Association of DNA polymerase mu (pol mu) with Ku and ligase IV: role for pol mu in end-joining double-strand break repair. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:5194–5202. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.14.5194-5202.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liang F, Han M, Romanienko PJ, Jasin M. Homology-directed repair is a major double-strand break repair pathway in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:5172–5177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boule JB, Johnson E, Rougeon F, Papanicolaou C. High-level expression of murine terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase in Escherichia coli grown at low temperature and overexpressing argU tRNA. Mol. Biotechnol. 1998;10:199–208. doi: 10.1007/BF02740839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murray JM, O’Neill JP, Messier T, Rivers J, Walker VE, McGonagle B, Trombley L, Cowell LG, Kelsoe G, McBlane F, et al. V(D)J recombinase-mediated processing of coding junctions at cryptic recombination signal sequences in peripheral T cells during human development. J. Immunol. 2006;177:5393–5404. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sale JE, Neuberger MS. TdT-accessible breaks are scattered over the immunoglobulin V domain in a constitutively hypermutating B cell line. Immunity. 1998;9:859–869. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80651-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kabotyanski EB, Gomelsky L, Han JO, Stamato TD, Roth DB. Double-strand break repair in Ku86- and XRCC4-deficient cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:5333–5342. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.23.5333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simsek D, Jasin M. Alternative end-joining is suppressed by the canonical NHEJ component Xrcc4-ligase IV during chromosomal translocation formation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:410–416. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weinstock DM, Brunet E, Jasin M. Formation of NHEJ-derived reciprocal chromosomal translocations does not require Ku70. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2007;9:978–981. doi: 10.1038/ncb1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Y, Jasin M. An essential role for CtIP in chromosomal translocation formation through an alternative end-joining pathway. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2011;18:80–84. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carroll D. Genome engineering with zinc-finger nucleases. Genetics. 2011;188:773–782. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.131433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller JC, Tan S, Qiao G, Barlow KA, Wang J, Xia DF, Meng X, Paschon DE, Leung E, Hinkley SJ, et al. A TALE nuclease architecture for efficient genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:143–148. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Silva G, Poirot L, Galetto R, Smith J, Montoya G, Duchateau P, Paques F. Meganucleases and other tools for targeted genome engineering: perspectives and challenges for gene therapy. Curr. Gene. Ther. 2011;11:11–27. doi: 10.2174/156652311794520111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boboila C, Jankovic M, Yan CT, Wang JH, Wesemann DR, Zhang T, Fazeli A, Feldman L, Nussenzweig A, Nussenzweig M, et al. Alternative end-joining catalyzes robust IgH locus deletions and translocations in the combined absence of ligase 4 and Ku70. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:3034–3039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915067107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stephens PJ, McBride DJ, Lin ML, Varela I, Pleasance ED, Simpson JT, Stebbings LA, Leroy C, Edkins S, Mudie LJ, et al. Complex landscapes of somatic rearrangement in human breast cancer genomes. Nature. 2009;462:1005–1010. doi: 10.1038/nature08645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Y, Gostissa M, Hildebrand DG, Becker MS, Boboila C, Chiarle R, Lewis S, Alt FW. The role of mechanistic factors in promoting chromosomal translocations found in lymphoid and other cancers. Adv.Immunol. 2010;106:93–133. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(10)06004-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.