Abstract

The wide availability and recent improvement in technology coupled with portability, low cost and safety makes ultrasound the first choice imaging investigation for the evaluation of musculoskeletal diseases. Diagnostic use of ultrasound findings is greatly enhanced by knowledge of the clinical presentation. Conversely, ultrasound skills with its prerequisite anatomical knowledge make the clinical diagnosis more precise and reduce uncertainty in the choice of therapy. Therefore, it is essential for rheumatologists to acquire ultrasonography skills in order to improve patient care. Ultrasound examination provides an excellent opportunity for patient education and to explain the rationale for therapy. This review summarizes the indications for musculoskeletal ultrasound and describes its role in diagnosis, monitoring and prognosis.

Keywords: ultrasonography, early diagnosis, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, osteoarthritis, crystal arthritis, seronegative spondyloarthropathy, epicondylitis, carpal tunnel syndrome, polymyalgia rheumatic, vasculitis, paediatric rheumatology, pain management, sports medicine, advances in MSK ultrasound

Introduction

Ultrasonography (US) has long been the domain of radiologists. However, with advances in technology and wide availability there is a larger trend among physicians in various specialties to integrate US into their routine clinical assessment. More recently rheumatologists have started using US for quantitative and qualitative real-time assessment of musculoskeletal (MSK) pathology. US is increasingly being used as an extension to physical examination. Its application in rheumatology goes beyond the detection of inflammation in joints.

Growing evidence has made it clear that early and aggressive therapy of inflammatory arthritis with a treat to target approach alters prognosis significantly. This requires the use of easily available imaging modalities such as ultrasound in establishing accurate diagnosis so that early therapeutic decisions can be made. Apart from diagnosis, US plays a major role in disease monitoring, assessment of damage and therapeutics.

History of musculoskeletal ultrasound

The earliest report of application of US in the MSK system was published in 1972 where the diagnostic potential of ultrasound was used to differentiate Baker’s cysts from thrombophlebitis [McDonald and Leopold, 1972]. Just a few years later US was used to demonstrate synovitis and to evaluate result of the treatment in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients [Cooperberg et al. 1978]. The applications of ultrasound to MSK conditions have continued to expand and it has become the primary modality of imaging for most of MSK conditions.

Advantages of ultrasonography

US is the most practical and rapid method of obtaining images of the MSK system. It can be performed readily in the clinic, with assessment of multiple joints at the same appointment, providing a ‘one stop’ answer to many MSK problems. This relatively inexpensive technology with the benefits of portability and real-time dynamic examination has made it possible to provide a diagnostics service in the community or even on the sports field.

US technology offers several inherent advantages. Being noninvasive, with a quick scan time and without radiation makes it well accepted by patients. There are several advantages from the clinician’s point of view. It allows contralateral examination and does not pose limitations due to metal artefacts, which can be problematic in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The ability to visualize needles and target structures in real time makes it an ideal tool for the guidance procedures used in diagnosis and management [Del Cura, 2008].

There are several applications of real-time dynamic US examination in the MSK system. US can show tendon instability such as anterior dislocation of the extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU) [Bianchi et al. 2001]. It plays an important role in the diagnosis of impingement of the shoulder by showing which structure is being impinged and reveals potential intrinsic and extrinsic causes [Bureau et al. 2006].

US performed by the physician provides an excellent opportunity for patient education and to explain the rationale for treatments [Borg et al. 2008]. With increasing experience the examiner is able to perform focused examination which provides immediate answers to any clinical queries raised.

Limitations

Despite these advantages, there are some limitations of this technology. US is considered to be an operator-dependent technology with poor repeatability. However, it is reassuring to see that recent studies have established moderate to good interobserver reliability [Scheel et al. 2005b; Schmidt and Blockmans, 2005; Naredo et al. 2006].

Even with advances in the resolution of the transducers, deeper structures are difficult to visualize as the higher-frequency transducers have lower tissue penetration. MRI has clear advantages over US in the imaging of deeper structures. MRI scans can also examine a larger area. Another limitation is the restricted access to certain joints such as the 4th metacarpophalangeal (MCP) which are difficult to image with an US probe.

Acquisition of US skills takes time depending on trainee’s hand–eye coordination skills. A long training period may be an important limiting factor in its popular use by physicians.

In addition, examination of multiples joints in the clinical setting can be time consuming. Evidence is accumulating for focused examination with concentration on a small number of active joints to reduce examination time [Backhaus et al. 2009].

Applications of US in musculoskeletal diseases

Ultrasound can be used in imaging both inflammatory and noninflammatory MSK diseases. US is used as a screening tool to detect and assess the degree of synovitis in a patient suspected of having inflammatory arthritis, whereas noninflammatory use involves the identification of structures involved in a soft-tissue-related clinical problem (e.g. suspected rotator cuff tear).

Rheumatoid arthritis

It is clear that early diagnosis and early treatment of inflammatory arthritis has an impact on prognosis. However, before exposing a patient to medications with potentially toxic side effects it is important to establish a correct diagnosis. The detection of synovitis on examination can be difficult and noninflammatory conditions such as fibromyalgia can mimic the features of inflammatory arthritis. Typical radiographic features of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), such as bone erosions, may not be present in the early stages of disease and serological markers have limitations of sensitivity and specificity. The use of US in the assessment of patients presenting with possible inflammatory arthritis may help to overcome these hurdles.

Synovitis

US has been shown to be more sensitive than clinical examination in determining synovitis [Grassi, 2003; Kane et al. 2003]. Brown and colleagues showed that RA patients who were judged by their consultant rheumatologist to be in remission had significant evidence of active inflammation on US. This ongoing subclinical inflammation can lead to radiographic progression [Brown et al. 2008]. The accurate evaluation of disease status may improve RA management by providing a more timely and accurate diagnosis, improving treatment decisions and more accurately assessing remission. In a study of 90 patients with active RA, US Disease Activity Score (DAS) was not only more reliable in assessing disease activity but it was also better at anticipating future joint damage [Damjanov et al. 2012].

The OMERACT definition of synovitis on US is abnormally thickened, hypoechoic, intra-articular tissue that is poorly compressible and can demonstrate increased Doppler signals [Wakefield et al. 2005] (Figure 1).

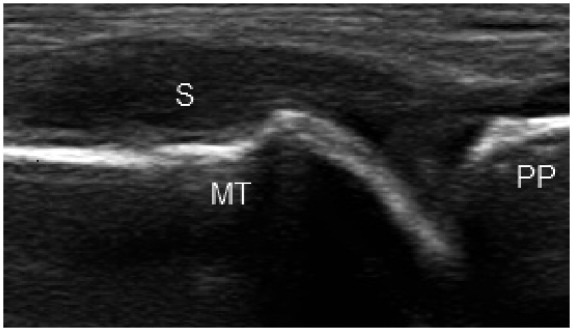

Figure 1.

Longitudinal image of the 1st metatarsophalyngeal joint showing grade 3 synovitis as hypoechoic synovial thickening within the joint capsule. MT, metatarsal head; PP, proximal phalanx; S, hypoechoic synovium.

The widely accepted method for synovial hypertrophy quantification with greyscale US is the semiquantitative scale [Szkudlarek et al. 2003]: 0 indicates no intra-articular changes, and 1–3 indicates mild, moderate, and large synovial hypertrophy (Figures 2–4). US detection of finger joint synovitis can be considerably improved by focusing on the palmar proximal area of the finger joints (proximal interphalangeal (PIP) and MCP) than from the dorsal aspect [Scheel et al. 2005a; Vlad et al. 2011].

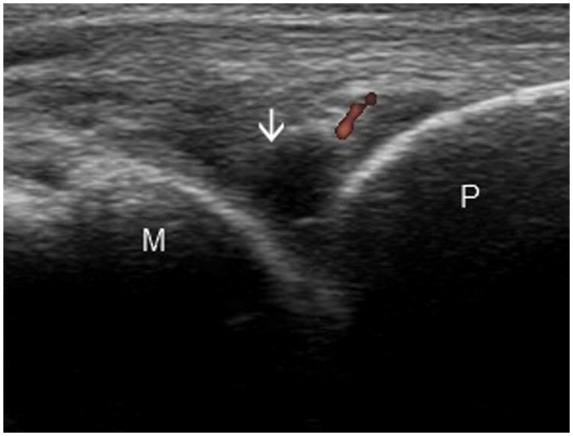

Figure 2.

Longitudinal image of the 4th metacarpophalangeal joint showing grade 1 synovitis (arrow) and power Doppler. M, metacarpal head; P, proximal phalanx.

Figure 3.

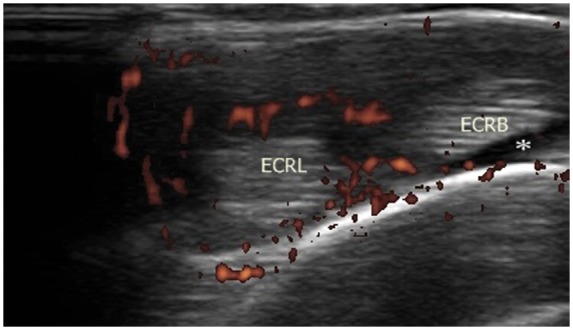

Transverse view of second extensor compartment of wrist joint demonstrating grade 2 power Doppler with anechoic fluid surrounding the tendons (asterisk). ECRL, extensor carpi radialis longus; ECRB, extensor carpi radialis brevis.

Figure 4.

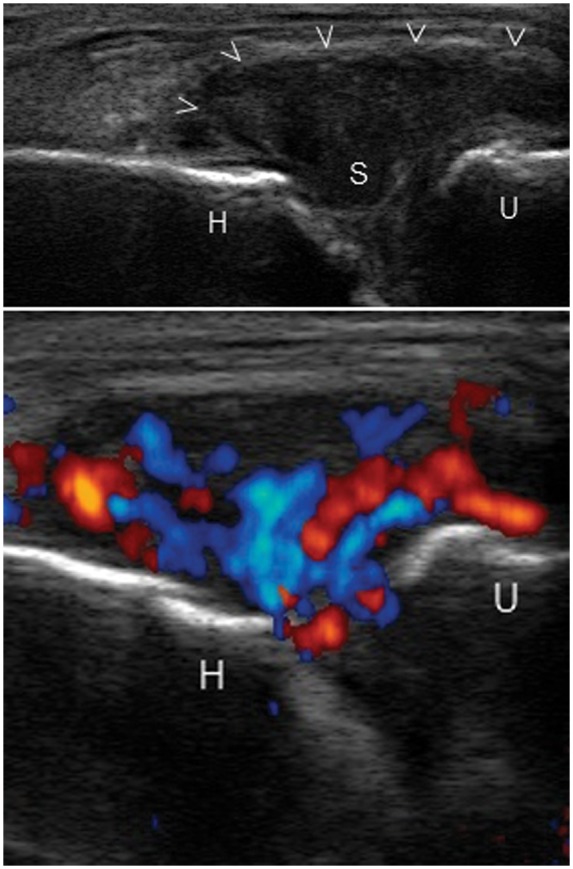

Grade 3 synovitis of the elbow joint with distended joint capsule (arrow heads) in a longitudinal view. H, trochlea of humerus; U, coronoid process of ulna; S, hypoechoic synovitis.

Power Doppler imaging plays a major role in monitoring response to treatment [Teh et al. 2003]. US scoring of synovial inflammatory activity involves four grades: 0, no flow in the synovium; 1, single-vessel signals (Figure 2); 2, confluent vessel signals in less than half of the area of the synovium (Figure 3); 3, vessel signals in more than half of the area of the synovium (Figure 4).

With advances in power Doppler technology its accuracy in measuring synovitis has been proved to be comparable to dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI [Szkudlarek et al. 2001; Terslev et al. 2003]. To prevent joint damage from subclinical inflammation, the use of power Doppler in defining remission of RA has been advocated [Saleem et al. 2011].

Erosions

When compared with radiography US is definitely more sensitive in identifying the presence of erosions during initial patient evaluation of RA patients [Bajaj et al. 2007]. US can detect up to seven times more metacarpophalangeal erosions than plain X-ray in early RA [Wakefield et al. 2000]. Detection of erosions early in the disease is predictive of an aggressive disease course [Van Der Heijde et al. 1992]. Thus, US also helps in determining prognosis.

On US, erosions are defined as the discontinuity of the smooth echogenic bone surface or cortex greater than 2 mm in diameter, visualized in two planes and having an irregular floor [Wakefield et al. 2005; Bajaj et al. 2007] (Figure 5). The 2 mm diameter size cut off not only has reliable repeatability but it also helps in distinguishing from nonpathological anatomical variations such as dorsal metacarpal head depressions [Lopez-Ben, 2007; Bajaj et al. 2007]. With regards to presence of bone erosion, interobserver agreement of 91% has been reported [Szkudlarek et al. 2003]. Power Doppler can show increased signal within this pannus indicating active disease. US detects more erosions in the easily accessible joints such as the 1st, 2nd and 5th MCP joints compared with the 4th MCP which protrudes less than other MCP joints.

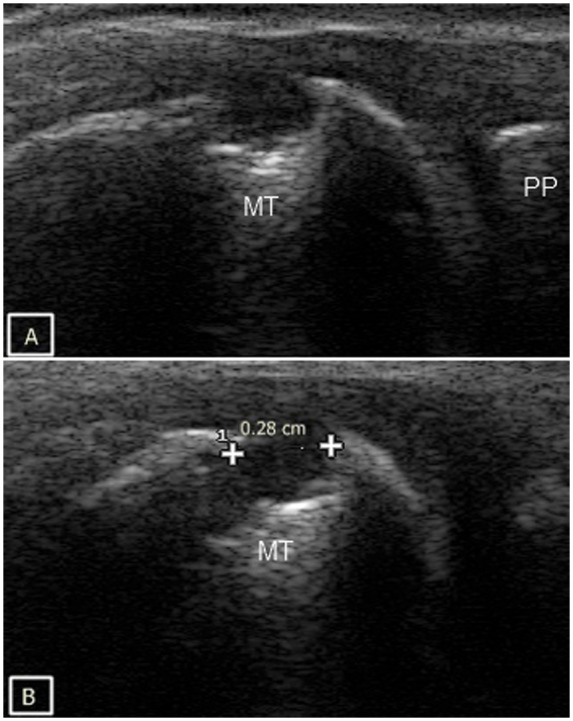

Figure 5.

Cortical bone erosion of the 1st metatarsophalyngeal joint in both longitudinal (A) and transverse plane (B). MT, metatarsal head; PP, proximal phalanx.

Tenosynovitis

Tenosynovitis is common in RA [Hmamouchi et al. 2011] but its true prevalence in early disease has not been firmly established. A complication of persistent tenosynovitis is complete rupture of the tendon with loss of function [Mcqueen et al. 2005]. Tenosynovitis can be difficult to diagnose clinically in patients with arthritis as pain could easily be attributed to underlying joint involvement. In view of reliability and a good sensitivity:specificity ratio, US has been proposed as the gold standard in assessing tendon involvement in rheumatic diseases [Grassi et al. 2000].

Tenosynovitis is defined by abnormal hypoechoic or anechoic material with or without fluid inside the tendon sheath and with possible signs of Doppler signals in two perpendicular planes [Wakefield et al. 2005] (Figures 6 and 7). Tendon sheath widening is considered as a hallmark of early tendon involvement in inflammatory arthritis [Grassi et al. 2000]. However, flexor tendon sheath thickening on US is also a feature of diabetic chiero-arthropathy [Ismail et al. 1996]. Tenosynovitis of the ECU, commonly seen in early RA, can easily be detected on US. Recently, involvement of the ECU was found to be associated with erosive progression in early RA [Lillegraven et al. 2011].

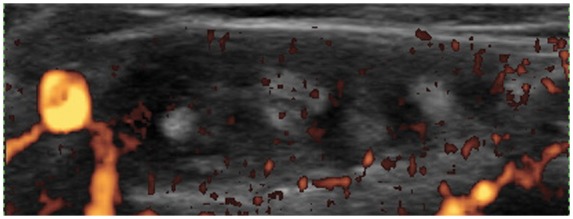

Figure 6.

Transverse view of the 4th extensor compartment of the wrist showing hypoechoic and hypervascular tenosynovitis.

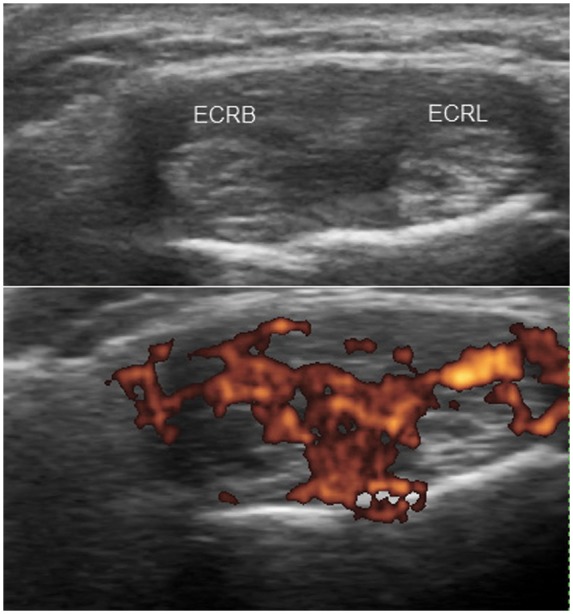

Figure 7.

Transverse view demonstrating tenosynovitis of the extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL) and brevis (ECRB) tendons with tendon swelling, synovial thickening and hypervascularity.

Psoriatic arthritis

About 50% of patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) progress, leading to functional impairment [Gladman et al. 1987]. US is useful in determining both intra- and extra-articular manifestations of PsA. The extra-articular features include enthesitis (Figure 8), tendonitis, tenosynovitis, and dactylitis [Scheinfeld, 2011; Kane et al. 1999]. Routine screening of psoriasis patients for the MSK involvement with US helps in detecting early PsA changes [De Simone et al. 2011].

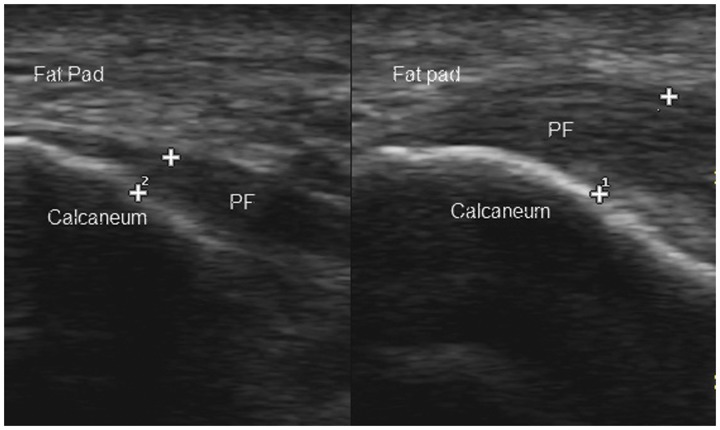

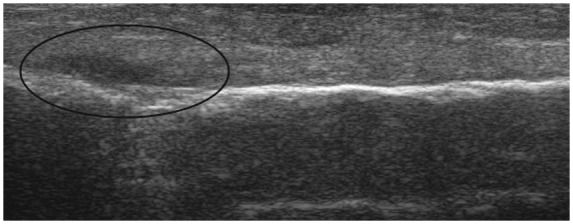

Figure 8.

Planter fasciitis on the right with significant thickening compared with the normal left side in a patient of newly diagnosed PsA. PF, planter fascia.

Osteoarthritis

Conventional radiography is the current standard for osteoarthritis (OA) imaging in routine practice. However, it does not allow the assessment of synovitis. In addition, radiographic features of OA do not concord with the symptoms of OA [Felson, 2004; Hannan et al. 2000]. US has been shown to be more sensitive than clinical examination in the detection of joint inflammation in patients with erosive OA [Koutroumpas et al. 2010]. Synovitis detection in OA is considered important because its presence has been shown to be associated with pain [Hill et al. 2001].

US can be used to detect various manifestations of OA including effusion, synovitis, erosion and osteophytes. Unlike in RA, synovial hypertrophy is seen in association with osteophytes in OA of the hand with no or minimal Doppler signal [Hayashi et al. 2011]. Given the discordance between radiographic structural changes and symptoms in OA, the importance of US-detected changes in terms of therapeutic interventions needs to be established.

Crystal arthritis

The physics of US makes it an ideal tool in the diagnosis of crystal arthritis. The crystalline material reflects US waves more strongly than surrounding tissues. Hence, US can detect deposition of crystals on cartilage, tendon sheaths, synovial fluid and subcutaneous tissues. In addition, it can visualize erosions and tophaceous material.

The anatomical location of the crystal deposits allows differentiation between monosodium urate (MSU) and calcium pyrophosphate aggregates. MSU crystals are deposited predominantly in the superficial portions of the articular cartilage giving rise to the ‘double contour’ sign [Sokoloff, 1957] (Figure 9). Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate (CPPD) crystals lie within the substance of the hyaline cartilage. These deposits can be seen to float within the joint cavity, giving rise to a ‘snowstorm’ appearance [Grassi et al. 2006] (Figure 10).

Figure 9.

Double contour sign: Longitudinal view demonstrating modest and discontinuous (arrows) hyperechoic enhancement on the cartilage surface due to MSU crystal deposition in a patient with longstanding gout.

Figure 10.

Snowstorm pattern characterized by rounded aggregates of variable echogenicity (arrowhead) floating within the joint cavity in a patient with crystal arthritis.

Medial and lateral epicondylitis

Epicondylitis is an inflammatory process that affects the elbow medially or laterally. In lateral epicondylitis due to overuse syndrome of the common extensor tendons, predominantly extensor carpi radialis brevis is affected. The reported sensitivity and specificity of US in the detection of lateral epicondylitis is approximately 80% and 50%, respectively [Levin et al. 2005].

Tendinosis appears as tendon enlargement and heterogeneity, and tendon tears are depicted as hypoechoic regions with adjacent tendon discontinuity [Walz et al. 2010]. US features of lateral epicondylitis that correlates well with symptoms are calcification within the common extensor tendon, tendon thickening, adjacent bone irregularity, focal hypoechoic regions in the tendon and diffuse tendon heterogeneity [Levin et al. 2005; Walz et al. 2010].

US is useful for determining the extent of tendon damage in patients who are symptomatic. Cortical irregularity would be useful in both diagnosing and determining the chronic stage of epicondylitis.

The US appearance of medial epicondylitis is similar to that of lateral epicondylitis. US can help to distinguish medial tendinopathy from a lesion of the underlying medial collateral ligament. Similar to the lateral epicondyle, enthesopathy may be observed at this site instead of tendinopathy.

US displayed sensitivity and specificity of 95% and 92%, respectively, in the detection of clinical medial epicondylitis [Park et al. 2008].

Enthesitis and bursitis in seronegative spondyloarthropathy

Traditionally, enthesitis has been evaluated by clinical examination based on the presence of tenderness and/or swelling. However, it is increasingly clear that enthesial involvement can be subclinical in spondyloarthropathy (SpA) [McGonagle and Benjamin, 2009]. US is better than clinical examination in the detection of peripheral enthesitis in SpA [Gutierrez et al. 2011]. This has been established in the assessment of enthesitis in children as well [Jousse-Joulin et al. 2011]. Enthesopathy on US is defined by the OMERACT criteria as ‘abnormally hypoechoic (loss of normal fibrillar architecture) and/or thickened tendon or ligament at its bony attachment (may occasionally contain hyperechoic foci consistent with calcification) seen in two perpendicular planes that may exhibit Doppler signal and/or bony changes including enthesophytes, erosions, irregularities’.

Adjacent bursitis is commonly seen on ultrasound in patients with SpA as an anechoic or hypoechoic collection between two hyperechoic lines [Filippucci et al. 2009] (Figures 11 and 12).

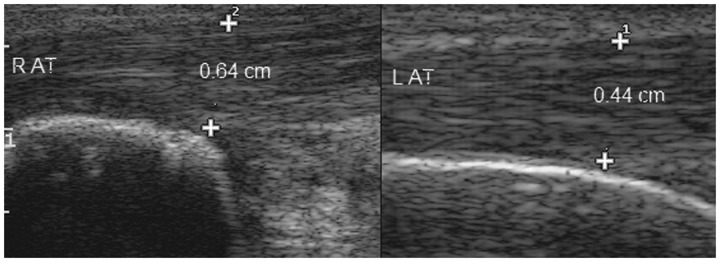

Figure 11.

Longitudinal view demonstrating thickening of right Achilles tendon in a seronegative spondyloarthropathy patient. R AT, right Achilles tendon; L AT, left Achilles tendon.

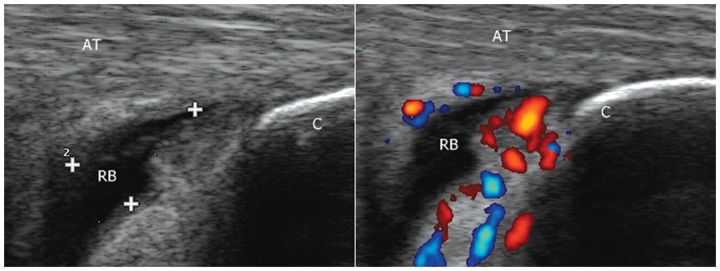

Figure 12.

Retrocalcaneal bursitis in a patient with active seronegative spondyloarthropathy. Grade 2 power Doppler on right indicates active disease. AT, Achilles tendon; RB, retrocalcaneal bursa; C, calcaneum.

Table 1.

Ultrasound features.

| Diagnosis | Common ultrasound features | Possible finding on ultrasound |

|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory arthritis | Synovitis with hypervascularity, erosions, joint effusions, tenosynovitis | Median nerve swelling, tendon rupture |

| Crystal arthritis | Synovitis, joint effusions, gouty erosions, tophi, chondrocalcinosis | Double contour sign, ‘snowstorm’ appearance |

| Osteoarthritis | Effusion, osteophytes, joint space narrowing | Synovitis with no or minimal Doppler signal, erosion |

| Carpal tunnel syndrome | Hypoechoic nerve swelling >10 mm, loss of fascicular pattern, flattening of nerve, tethering of nerve | Notch sign, synovitis, tenosynovitis, ganglions, nerve sheath deposits |

| Medial and lateral epicondylitis | Tendon thickening, focal hypoechoic regions in the tendon, and diffuse tendon heterogeneity, hypervascularity | Calcification within the common extensor/flexor tendon origin and adjacent bone irregularity (chronic cases) |

| Seronegative spondyloarthropathy | Peripheral enthesitis, hypervascularity | Planter fasciitis, retrocalcaneal bursitis, Achilles tendonitis |

| Polymyalgia rheumatica | Bilateral subacromial/subdeltoid bursitis, biceps long head tenosynovitis and trochanteric bursitis, synovitis, hip effusion | Enthesitis, glenohumeral effusions, Flexor tenosynovitis, peripheral synovitis |

| Giant cell arteritis | Temporal artery periluminal hypoechogenic halo sign, Segmental arterial stenosis and arterial luminal occlusion | Axillary artery involvement |

Carpal tunnel syndrome

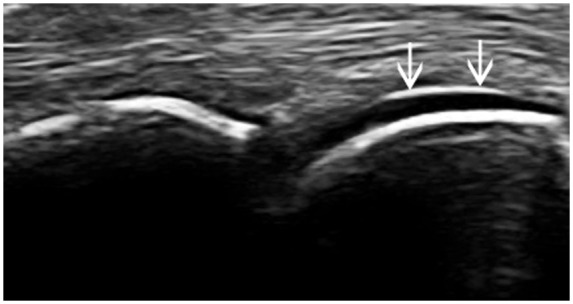

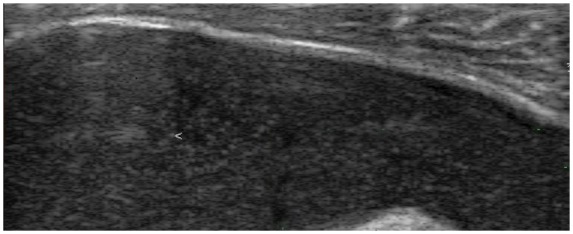

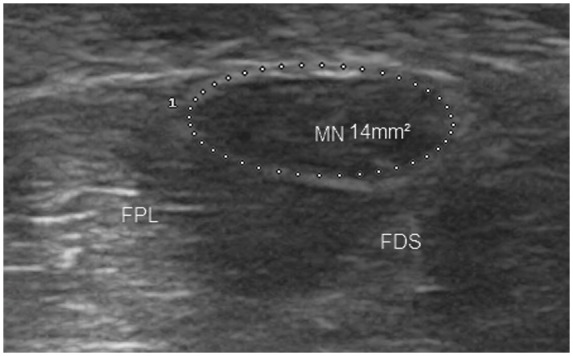

The most common entrapment neuropathy of the wrist concerns the median nerve at the carpal tunnel. US diagnosis is based on the demonstration of secondary nerve changes, i.e. hypoechoic nerve swelling, loss of fascicular pattern or flattening of nerve. Inflammatory arthritis, metabolic conditions and ganglions are all well-described causes of carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS). As compared with invasive nerve conduction tests US not only helps in the diagnosis of CTS but also provides essential anatomic information which can modify the surgical approach. For example, US may show the presence of a median artery or a local expansile mass, such as ganglia.

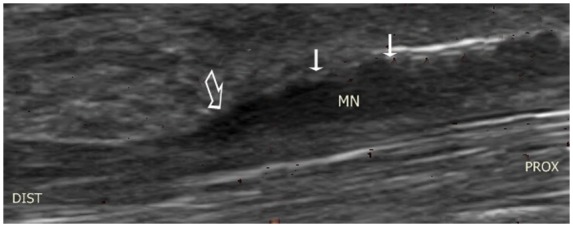

The widely used diagnostic criterion is reported to be a median nerve cross-sectional area greater than 9 mm2 at the level of pisiform bone [Duncan et al. 1999] (Figure 13). This has reported sensitivity of 82% and specificity of 92%. The increase in cross-sectional diameter correlates well with the severity of electromyographic findings or the functional outcome after surgery [Hashefi, 2009]. Other features are the ‘notch sign’ (Figure 14) and power Doppler signals seen within the swollen nerve.

Figure 13.

Median nerve in transverse view showing hypoechoic swelling at the scaphoid–pisiform level. MN, median nerve; FPL, flexor pollicis longus; FDS, flexor digitorum superficialis.

Figure 14.

Longitudinal view of median nerve demonstrating hypoechoic swelling (small arrows) and ‘notch sign’ which indicates an abrupt change in median nerve calibre in the carpal tunnel at proximal part of flexor retinaculum (large arrow). MN, median nerve.

Polymyalgia rheumatica

Until the last few years, imaging played only a minor role in the diagnosis of polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR). With advances in technology US has increasingly been used as an adjunct to the diagnosis of PMR. It can be particularly helpful in establishing diagnosis in patients with typical PMR symptoms who have normal inflammatory markers. Typical US findings of PMR include bilateral subacromial bursitis, biceps long head tenosynovitis (Figure 15) and trochanteric bursitis. These findings help to distinguish PMR from other inflammatory diseases. Synovial proliferation is not typical in PMR [Falsetti et al. 2011] (Figure 16) and if it is present other differentials such as late onset RA should be considered. In the hips, most frequent ultrasound findings are synovitis and trochanteric bursitis. The recent EULAR ACR PMR classification criteria award a point each for typical US findings, in either both shoulders or a shoulder and a hip, as part of the overall scoring algorithm for PMR [Dasgupta et al. 2012]. In addition, US may have utility in disease assessment [Matteson et al. 2012].

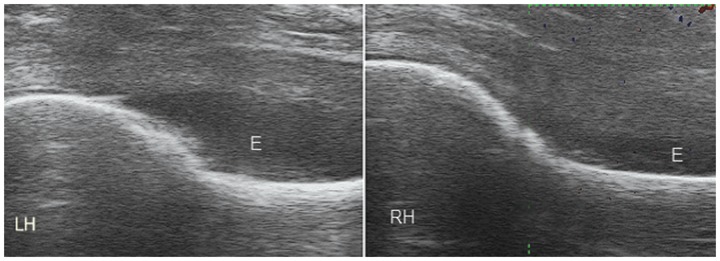

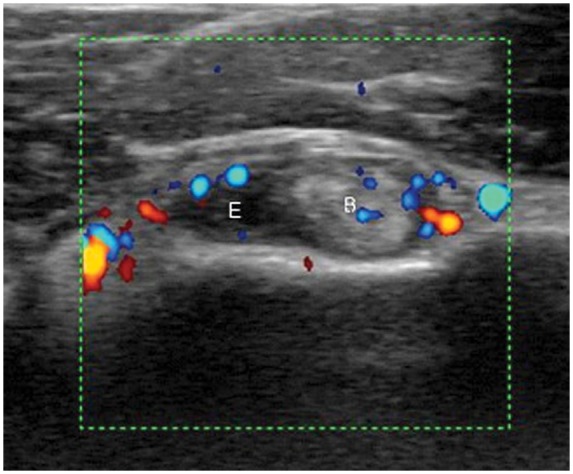

Figure 15.

Transverse view showing the long head of the biceps demonstrating tenosynovitis and effusion in a patient with polymyalgia rheumatica. E, effusion; B, long head of the biceps.

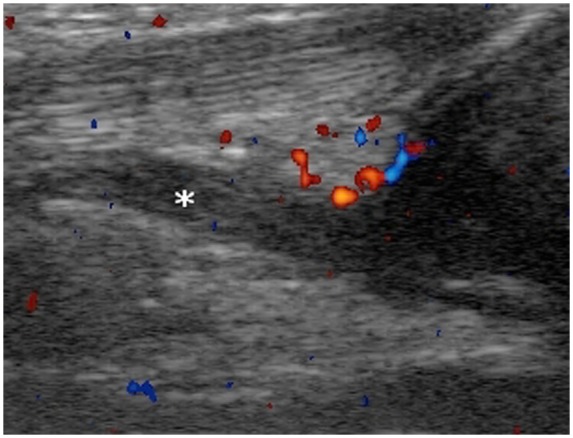

Figure 16.

Bilateral hip effusions with no hypervascularity in a patient with PMR. E, effusion; LH, left hip; RH, right hip.

Vasculitis

Application of US for the diagnosis of large vessel vasculitis and early Takayasu arteritis has been reported in the literature [Schmidt et al. 2002, 2006; Schmidt and Blockmans, 2005]. Schmidt and colleagues [Schmidt et al. 2006] showed that arteritis of small vessels involved in granulomatosis with polyangiitis and rheumatoid vasculitis can also be assessed with US.

The role of US in the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis (GCA) is becoming increasingly recognized due to the lack of specific biomarkers and the fact that a failure to diagnose in time can result in irreversible visual loss. Temporal artery biopsy is considered the gold standard. However, it has the limitation of being an invasive technique with a complication rate of 0.5% and only moderate sensitivity. Ultrasound can contribute significantly in the diagnosis of GCA by identifying characteristic findings in the temporal artery. A recent meta-analysis reported that the unilateral periluminal hypoechogenic halo reflecting arterial wall oedema achieved an overall sensitivity of 68% and specificity of 91% in biopsy-proven GCA [Arida et al. 2010] (Figure 17). Segmental arterial stenosis and arterial luminal occlusion can be seen in severe cases of GCA. Suelves and colleagues [Suelves et al. 2010] found 100% correlation with temporal artery biopsy. They also established the use of US in the selection of the inflamed section of artery for biopsy, treatment response evaluation and detection of disease relapse with recurrence of halo sign. This technology has the potential to replace biopsy as the first-line diagnostic procedure in GCA. An ongoing multicentre study in the UK (TABUL GCA) is aimed at validating this hypothesis. A long training period is required for the acquisition of high-quality images and the ability to interpret findings correctly.

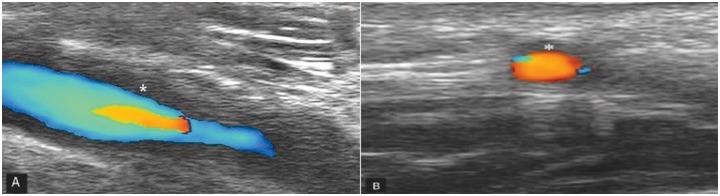

Figure 17.

‘Halo sign’ of GCA: hypoechoic area (asterisk) around the temporal artery in longitudinal view (A) and transverse view (B).

Paediatric rheumatology

The lack of ionizing radiation, quick scan time and close interaction between the examiner and patient makes US an ideal modality for use in paediatric MSK diseases. However, getting maximum cooperation from a child is required for good results. Examinations performed by the child’s physician in the same clinical environment can help to overcome this hurdle.

The classification, treatment strategy and prognosis of some forms of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) are based on the number of joints involved. In this context US can play a vital role with its ability to detect subclinical inflammatory change in the joints (Figures 18 and 19). In one study of early arthritis originally felt to be oligoarthritis, US detected subclinical synovitis in two thirds of the patients while one third could be reclassified as polyarticular [Wakefield et al. 2004]. Spârchez and colleagues found power Doppler assessment of disease activity in children with JIA superior to erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein [Spârchez et al. 2010].

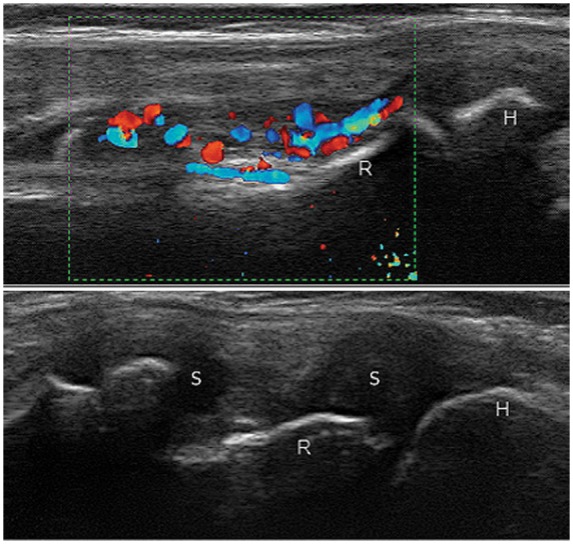

Figure 18.

Clinical examination of a 4-year-old child did not reveal any abnormality; a left knee effusion extending into suprapatellar bursa (asterisk) was noted on ultrasound.

Figure 19.

Right elbow synovitis grade 3 with PD grade 2 in a 10-year-old boy with polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. H, humerus; R, radial head; S, synovitis.

Apart from JIA, US has a significant role to play in various paediatric MSK diseases including sports injuries, congenital and developmental disorders, acute trauma of bone and joints, and peripheral nerve injuries [Martinoli et al. 2011].

Pain management

As this technology has a high success rate in avoiding sensitive structures under constant monitoring, this makes it an ideal tool for use in pain management. With advances in technology such as enhanced needle visualization, US is increasingly competing with traditional imaging such as fluoroscopy or computed tomography (CT). The lack of radiation and ability of US to visualize small nerves in real time makes it the modality of choice for diagnostic and therapeutic nerve blocks [Curatolo and Eichenberger, 2008].

Diagnostic use involves injection of low-dose local anesthetic near to nerves that supply the site of the pain origin to see whether it relieves the pain. Identifying the source of pain then allows targeted treatments such as nerve blocks or denervation.

An example is identification of source of neck pain following whiplash injury. Injecting small amount of local anaesthetic helps to identify involved zygapophyseal joints. This identifies the nerves to be destroyed using a percutaneous radiofrequency neurotomy technique providing lasting pain relief [Eichenberger et al. 2004]. However, diagnostic blocks are not suitable to identify the pathology responsible for the pain (e.g. inflammatory, neuropathic, etc.).

Sports medicine

US is commonly being used for ‘on-field assessment’ of injured athletes due to portability and technological advances in the equipment. Examination of tendons forms a major part of sports medicine. US can be considered to be the best method for the study of tendons [Grassi et al. 2000] and dynamic imaging can support the clinical examination by showing the level of tendon subluxation and determine the severity of a tendon injury (Figure 21). US should be used in establishing accurate diagnosis as rheumatic diseases can initially mimic sports-related injuries [Jennings et al. 2008].

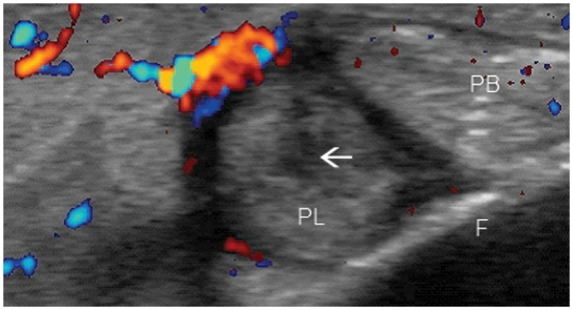

Figure 21.

Peroneal longus tendon tear (arrow) in transverse view. Peroneal tendon injury is a major cause of posttraumatic lateral ankle pain. PL, peroneus longus; PB, peroneus brevis; F, fibula.

Similarly, ultrasound is useful in assessing muscle injury. There will be loss of the normal pennate pattern of the muscle fibres corresponding to the location of the damage within muscle. However, in the first 25 hours muscle injury can sometimes be difficult to identify using ultrasound [Allen and Wilson, 2007]. Bone should routinely be assessed during ultrasonography as it can detect occult fractures incidentally during the examination of soft tissue (Figure 20).

Figure 20.

Longitudinal lateral view of the fibula. Bone should routinely be assessed during ultrasonography as it can detect occult fractures incidentally during the examination of soft tissues as shown in this picture.

US is considered a reliable diagnostic tool to distinguish between a simple muscle strain and an avulsion fracture in young athletes [Hashefi, 2009]. Other common indications for the use of US in sports injuries include diagnosis of sternal and insufficiency fractures and central slip injuries in the extensor mechanism of the finger.

Recent advances

US imaging techniques are evolving continuously with the discovery of new techniques and increasing application in rheumatology.

Contrast-enhanced US

With help of contrast agents the potential applications of the Doppler technique have increased further. Colour and power Doppler sonography are limited in their ability to detect low-volume blood flow in very small vessels. US contrast agents increase sensitivity of colour Doppler examination by enhancing the blood scattering reflection [Cimmino and Grassi, 2008]. Their use is becoming established in the assessment of disease activity. With arthroscopy as a reference a study has proved reliability of contrast-enhanced US in the detection of synovial vascularity [Fiocco et al. 2003]. US contrast media can help in early detection and follow up of disease activity in RA [De Zordo et al. 2007]. However, the routine use of contrast agents for MSK US examinations is not established enough as it is for MRI.

Three-dimensional US

The revolutionary development of three-dimensional US technology has made it possible to study the joint in great detail. It can help surgeons to understand anatomy well before surgery. This technology can overcome the limitation of traditional US. However, it still remains operator dependant with long learning curve. The most promising application of 3D US is in the monitoring of synovial perfusion using power Doppler [Cimmino and Grassi, 2008].

Fusion imaging

Fusion of ultrasonographic data with MRI or CT data is another logical step to increase diagnostic accuracy. Image fusion combines the advantages of two different technologies and negates each other’s limitations to produce optimal results. In a study by Klauser and colleagues, fusion of real-time US and previously obtained CT scans improved the accuracy of injection into the sacroiliac joints [Klauser et al. 2010].

Conclusion

Ultrasound provides a safe, cost-effective and rapid means of assessing MSK abnormalities. This review has emphasized the role of ultrasound examination as the primary imaging investigation in initial evaluation of MSK diseases. In most aspects of assessment of MSK diseases US is comparable to or even better than the expensive imaging techniques such as MRI. The combination of high-frequency probes and improved power Doppler technology provides a great opportunity to study image aspects of inflammatory conditions such as tenosynovitis and enthesitis that were traditionally considered difficult to image. Recent advances in technology such as three-dimensional ultrasound and contrast agents have potential to play a major role in early detection and monitoring of inflammatory arthritis in the future. The long learning curve remains an important limiting factor to widespread use of US in routine clinical practice.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: Prof. Dasgupta has received honorarium for lectures/consultation with Merck, Roche, Pfizer and Mundipharma.

Contributor Information

Pravin Patil, Southend University Hospital – Rheumatology, Prittlewell Chase, Westcliff-on-Sea, Essex SS0 0RY, UK.

Bhaskar Dasgupta, Southend University Hospital – Rheumatology, Prittlewell Chase, Westcliff-on-Sea, Essex, UK.

References

- Allen G., Wilson D. (2007) Ultrasound in sports medicine - a critical evaluation. Eur J Radiol 62: 79–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arida A., Kyprianou M., Kanakis M., Sfikakis P.P. (2010) The diagnostic value of ultrasonography-derived edema of the temporal artery wall in giant cell arteritis: a second meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 11: 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backhaus M., Ohrndorf S., Kellner H., Strunk J., Backhaus T.M., Hartung W., et al. (2009) Evaluation of a novel 7-joint ultrasound score in daily rheumatologic practice: a pilot project. Arthritis Rheum 61: 1194–1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj S., Lopez-Ben R., Oster R., Alarcon G.S. (2007) Ultrasound detects rapid progression of erosive disease in early rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective longitudinal study. Skeletal Radiol 36: 123–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi S., Martinoli C., Sureda D., Rizzatto G. (2001) Ultrasound of the hand. Eur J Ultrasound 14: 29–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borg F., Agrawal S., Dasgupta B. (2008) The use of musculoskeletal ultrasound in patient education. Ann Rheum Dis 67: 419 [Google Scholar]

- Brown A.K., Conaghan P.G., Karim Z., Quinn M.A., Ikeda K., Peterfy C.G., et al. (2008) An explanation for the apparent dissociation between clinical remission and continued structural deterioration in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 58: 2958–2967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau N.J., Beauchamp M., Cardinal E., Brassard P. (2006) Dynamic sonography evaluation of shoulder impingement syndrome. Am J Roentgenol 187: 216–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimmino M.A., Grassi W. (2008) What is new in ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging for musculoskeletal disorders? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 22: 1141–1148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooperberg P.L., Tsang I., Truelove L., Knickerbocker W.J. (1978) Gray scale ultrasound in the evaluation of rheumatoid arthritis of the knee. Radiology 126: 759–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curatolo M., Eichenberger U. (2008) Ultrasound in interventional pain management. Eur J Pain Suppl 2: 78–83 [Google Scholar]

- Damjanov N., Radunovic G., Prodanovic S., Vukovic V., Milic V., Pasalic K.S., et al. (2012) Construct validity and reliability of ultrasound disease activity score in assessing joint inflammation in RA: comparison with DAS-28. Rheumatology 51: 120–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta B., Cimmino M., Maradit-Kremers H., et al. (2012) European League Against Rheumatism - American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for polymyalgia rheumatica. Ann Rheum Dis Arthritis Rheum, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Cura J.L. (2008) Ultrasound-guided therapeutic procedures in the musculoskeletal system. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol 37: 203–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Simone C., Caldarola G., D’agostino M., Carbone A., Guerriero C., Bonomo L., et al. (2011) Usefulness of ultrasound imaging in detecting psoriatic arthritis of fingers and toes in patients with psoriasis. Clin Developmental Immunol, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Zordo T., Mlekusch S.P., Feuchtner G.M., Mur E., Schirmer M., Klauser A.S. (2007) Value of contrast-enhanced ultrasound in rheumatoid arthritis. Eur J Radiol 64: 222–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan I., Sullivan P., Lomas F. (1999) Sonography in the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. AJR Am J Roentgenol 173: 681–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenberger U., Greher M., Curatolo M. (2004) Ultrasound in interventional pain management. Techn Regional Anesthesia Pain Managem 8: 171–178 [Google Scholar]

- Falsetti P., Acciai C., Volpe A., Lenzi L. (2011) Ultrasonography in early assessment of elderly patients with polymyalgic symptoms: a role in predicting diagnostic outcome? Scand J Rheumatol 40: 57–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felson D.T. (2004) An update on the pathogenesis and epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Radiol Clin North Am 42: 1–9, v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippucci E., Aydin S.Z., Karadag O., Salaffi F., Gutierrez M., Direskeneli H., et al. (2009) Reliability of high-resolution ultrasonography in the assessment of Achilles tendon enthesopathy in seronegative spondyloarthropathies. Ann Rheum Dis 68: 1850–1855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiocco U., Ferro F., Cozzi L., Vezzu M., Sfriso P., Checchetto C., et al. (2003) Contrast medium in power Doppler ultrasound for assessment of synovial vascularity: comparison with arthroscopy. J Rheumatol 30: 2170–2176 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladman D.D, Shuckett R., Russell M.L., Thorne J.C., Schachter R.K. (1987) Psoriatic arthritis (PSA) - an analysis of 220 patients. Q J Med 62: 127–141 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassi W. (2003) Clinical evaluation versus ultrasonography: who is the winner? J Rheumatol 30: 908–909 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassi W., Meenagh G., Pascual E., Filippucci E. (2006) “Crystal Clear” - sonographic assessment of gout and calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease. Semin Arthritis Rheum 36: 197–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassi W., Filippucci E., Farina A., Cervini C. (2000) Current comment sonographic imaging of tendons. Arthritis Rheum 43: 969–976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez M., Filippucci E., De Angelis R., Salaffi F., Filosa G., Ruta S., et al. (2011) Subclinical entheseal involvement in patients with psoriasis: an ultrasound study. Semin Arthritis Rheum 40: 407–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannan M.T., Felson D.T., Pincus T. (2000) Analysis of the discordance between radiographic changes and knee pain in osteoarthritis of the knee. J Rheumatol 27: 1513–1517 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashefi M. (2009) Ultrasound in the diagnosis of noninflammatory musculoskeletal conditions. MRI Ultrasound Diagnosis Managem Rheumatol Dis 1154: 171–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi D., Roemer F.W., Katur A., Felson D.T., Yang S.O., Alomran F., et al. (2011) Imaging of synovitis in osteoarthritis: current status and outlook. Semin Arthritis Rheum 41: 116–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill C.L., Gale D.G., Chaisson C.E., Skinner K., Kazis L., Gale M.E., et al. (2001) Knee effusions, popliteal cysts, and synovial thickening: association with knee pain in osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol 28: 1330–1337 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hmamouchi I., Bahiri R., Srifi N., Aktaou S., Abouqal R., Hajjaj-Hassouni N. (2011) A comparison of ultrasound and clinical examination in the detection of flexor tenosynovitis in early arthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 12: 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail A.A., Dasgupta B., Tanqueray A.B., Hamblin J.J. (1996) Ultrasonographic features of diabetic cheiroarthropathy. Br J Rheumatol 35: 676–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings F., Lambert E., Fredericson M. (2008) Rheumatic diseases presenting as sports-related injuries. Sports Med 38: 917–930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jousse-Joulin S., Breton S., Cangemi C., Fenoll B., Bressolette L., De Parscau L., et al. (2011) Ultrasonography for detecting enthesitis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 63: 849–855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane D., Greaney T., Bresnihan B., Gibney R., FitzGerald O., et al. (1999) Ultrasonography in the diagnosis and management of psoriatic dactylitis. J Rheumatol 26: 1746–1751 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane D., Balint P.V., Sturrock R.D. (2003) Ultrasonography is superior to clinical examination in the detection and localization of knee joint effusion in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 30: 966–971 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klauser A.S., De Zordo T., Feuchtner G.M., Djedovic G., Weiler R.B., Faschingbauer R., et al. (2010) Fusion of real-time US with CT images to guide sacroiliac joint injection in vitro and in vivo. Radiology 256: 547–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutroumpas A.C., Alexiou I.S., Vlychou M., Sakkas L.I. (2010) Comparison between clinical and ultrasonographic assessment in patients with erosive osteoarthritis of the hands. Clin Rheumatol 29: 511–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin D., Nazarian L.N., Miller T.T., O’Kane P.L., Feld R.I., Parker L., et al. (2005) Lateral epicondylitis of the elbow: US findings. Radiology 237: 230–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillegraven S., Boyesen P., Hammer H.B., Ostergaard M., Uhlig T., Sesseng S., et al. (2011) Tenosynovitis of the extensor carpi ulnaris tendon predicts erosive progression in early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 70: U2049–U2199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Ben R. (2007) Rheumatoid arthritis: ultrasound assessment of synovitis and erosions. Ultrasound Clin 2: 727–736 [Google Scholar]

- Martinoli C., Valle M., Malattia C., Beatrice Damasio M., Tagliafico A. (2011) Paediatric musculoskeletal US beyond the hip joint. Pediatr Radiol 41(Suppl. 1): S113–S124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matteson E.L., Maradit-Kremers H., Cimmino M.A., Schmidt W.A., Schirmer M., Salvarani C., et al. (2012) Patient-reported outcomes in Polymyalgia Rheumatica. J Rheumatol. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald D., Leopold G. (1972) Ultrasound B-scanning in the differentiation of Baker’s cyst and thrombophlebitis. Br J Radiol 45: 729–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGonagle D., Benjamin M. (2009) Entheses, enthesitis and enthesopathy. Topical Rev 38: 2209 [Google Scholar]

- Mcqueen F., Beckley V., Crabbe J., Robinson E., Yeoman S., Stewart N. (2005) Magnetic resonance imaging evidence of tendinopathy in early rheumatoid arthritis predicts tendon rupture at six years. Arthritis Rheum 52: 744–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naredo E., Moller I., Moragues C., De Agustin J.J., Scheel A.K., Grassi W., et al. (2006) Interobserver reliability in musculoskeletal ultrasonography: results from a “teach the teachers” rheumatologist course. Ann Rheum Dis 65: 14–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park G.Y., Lee S.M., Lee M.Y. (2008) Diagnostic value of ultrasonography for clinical medial epicondylitis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 89: 738–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff L. (1957) The pathology of gout. Metabolism Clin Exp 6: 230–243 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleem B., Brown A.K., Keen H., Nizam S., Freeston J., Wakefield R., et al. (2011) Should imaging be a component of rheumatoid arthritis remission criteria? A comparison between traditional and modified composite remission scores and imaging assessments. Ann Rheum Dis 70: 792–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheel A.K., Hermann K.G., Kahler E., Pasewaldt D., Fritz J., Hamm B., et al. (2005a) A Novel ultrasonographic synovitis scoring system suitable for analyzing finger joint inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 52: 733–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheel A.K., Schmidt W.A., Hermann K.G., Bruyn G.A., D’agostino M.A., Grassi W., et al. (2005b) Interobserver reliability of rheumatologists performing musculoskeletal ultrasonography: results from a EULAR “Train the Trainers” course. Ann Rheum Dis 64: 1043–1049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheinfeld N. (2011) Psoriatic arthritis imaging. Medscape. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/394752-overview#showall

- Schmidt W.A., Blockmans D. (2005) Use of ultrasonography and positron emission tomography in the diagnosis and assessment of large-vessel vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 17: 9–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt W.A., Nerenheim A., Seipelt E., Poehls C., Gromnica-Ihle E. (2002) Diagnosis of early Takayasu arteritis with sonography. Rheumatology 41: 496–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt W.A., Wernicke D., Kiefer E., Gromnica-Ihle E. (2006) Colour duplex sonography of finger arteries in vasculitis and in systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 65: 265–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spârchez M., Fodor D., Miu N. (2010) The role of power Doppler ultrasonography in comparison with biological markers in the evaluation of disease activity in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Med Ultrason 12: 97–103 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suelves A.M., Espana-Gregori E., Tembl J., Rohrweck S., Millan J.M., Diaz-Llopis M. (2010) Doppler ultrasound and giant cell arteritis. Clin Ophthalmol 4: 1383–1384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szkudlarek M., Court-Payen M., Jacobsen S., Klarlund M., Thomsen H.S., Ostergaard M. (2003) Interobserver agreement in ultrasonography of the finger and toe joints in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 48: 955–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szkudlarek M., Court-Payen M., Strandberg C., Klarlund M., Klausen T., Ostergaard M. (2001) Power Doppler ultrasonography for assessment of synovitis in the metacarpophalangeal joints of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a comparison with dynamic magnetic resonance imaging. Arthritis Rheum 44: 2018–2023 TABUL GCA: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT00974883?show_desc=Y#desc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teh J., Stevens K., Williamson L., Leung J., McNally E.G. (2003) Power Doppler ultrasound of rheumatoid synovitis: quantification of therapeutic response. Br J Radiol 76: 875–879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terslev L., Torp-Pedersen S., Savnik A., Von Der Recke P., Qvistgaard E., Danneskiold-Samsoe B., et al. (2003) Doppler ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging of synovial inflammation of the hand in rheumatoid arthritis: a comparative study. Arthritis Rheum 48: 2434–2441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Heijde D.M., Van Riel P.L., Van Leeuwen M.A., Van ‘T Hof M.A., Van Rijswijk M.H., Van De Putte L.B. (1992) Prognostic factors for radiographic damage and physical disability in early rheumatoid arthritis. A prospective follow-up study of 147 patients. Br J Rheumatol 31: 519–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlad V., Berghea F., Libianu S., Balanescu A., Bojinca V., Constantinescu C., et al. (2011) Ultrasound in rheumatoid arthritis: volar versus dorsal synovitis evaluation and scoring. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 12: 124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield R.J., Balint P.V., Szkudlarek M., Filippucci E., Backhaus M., D’agostino M.A., et al. (2005) Musculoskeletal ultrasound including definitions for ultrasonographic pathology. J Rheumatol 32: 2485–2487 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield R.J., Gibbon W.W., Conaghan P.G., O’Connor P., McGonagle D., Pease C., et al. (2000) The value of sonography in the detection of bone erosions in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a comparison with conventional radiography. Arthritis Rheum 43: 2762–2770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield R.J., Green M.J., Marzo-Ortega H., Conaghan P.G., Gibbon W.W., McGonagle D., et al. (2004) Should oligoarthritis be reclassified? Ultrasound reveals a high prevalence of subclinical disease. Ann Rheum Dis 63: 382–385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walz D.M., Newman J.S., Konin G.P., Ross G. (2010) Epicondylitis: pathogenesis, imaging, and treatment. Radiographics 30: 167–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]