Abstract

This paper describes tooth development in a basal squamate, Paroedura picta. Due to its reproductive strategy, mode of development and position within the reptiles, this gecko represents an excellent model organism for the study of reptile development. Here we document the dental pattern and development of non-functional (null generation) and functional generations of teeth during embryonic development. Tooth development is followed from initiation to cytodifferentiation and ankylosis, as the tooth germs develop from bud, through cap to bell stages. The fate of the single generation of non-functional (null generation) teeth is shown to be variable, with some teeth being expelled from the oral cavity, while others are incorporated into the functional bone and teeth, or are absorbed. Fate appears to depend on the initiation site within the oral cavity, with the first null generation teeth forming before formation of the dental lamina. We show evidence for a stratum intermedium layer in the enamel epithelium of functional teeth and show that the bicuspid shape of the teeth is created by asymmetrical deposition of enamel, and not by folding of the inner dental epithelium as observed in mammals.

Keywords: cusps, gecko, null generation teeth, tooth development

Introduction

The structural qualities of teeth and design of the dentition are often viewed as pertinent characteristics of particular clades of vertebrates and key factors responsible for their evolutionary prosperity. Given this, comparative information on dental characters, and the developmental mechanisms that produce them, can essentially refine our comprehension of the dynamics of vertebrate evolution. To address this task it is important to examine dental development in a wide spectrum of different clades represented – if possible – by a model taxon close to the stem lines of extant crown groups that illustrates the dental specificities of a specific clade. It is also important to examine the distribution of particular dental characters over a phylogenetic tree in order to produce a vivid view of the actual pathways of dental phylogeny. However, the current taxonomical sampling available for such studies is often biased. The main model taxa of dental development (zebra fish, mouse, human) are greatly derived, and sufficiently rich comparative information is available perhaps only in mammals (Keranen et al. 1998; Jarvinen et al. 2008, 2009; Salazar-Ciudad & Jernvall, 2010; Stembirek et al. 2010; Yamanaka et al. 2010; Moustakas et al. 2011). In comparison with mammals, much less is known about dental development and the developmental background of dental variation in other tetrapods, both Amniota and Anamnia. Recently this has started to change, with tooth development being investigated in a range of squamate reptiles (Delgado et al. 2005; Buchtova et al. 2008; Vonk et al. 2008; Zahradnicek et al. 2008; Handrigan & Richman, 2010, 2011; Handrigan et al. 2010; Maxwell et al. 2011).

The traditional odontologic comparisons (Edmund, 1969; Peyer, 1986) provide convincing evidence that the major divergences in amniote radiations are accompanied by clade-specific dental characters. While dental evolution in Synapsida and Archosauria show, despite clear differences, certain similarities (thecodonty, reduction of tooth number, enlarging teeth, convergent appearance of prismatic enamel in several crown groups; compared in Buffetaut et al. 1986) the situation in Lepidosauria is clearly different. Although Lepidosauria are the largest clade of non-volant amniotes with more that 8000 species, the extent of dental rearrangements in this clade is much smaller than in other amniote tetrapods. The lepidosauria are divided into the Squamata and Rhynchocephalia. Extant Squamata, with the exception of the derived Toxifera (Vidal & Hedges, 2005), are mostly characterized by a homodont dentition composed of a large number of relatively small uniform conical teeth, structurally often resembling the functional dentition of extant amphibians, with attachment ranging from pleurodont to acrodont. In contrast, the Rhynchocephalia, represented in extant form by the tuatura, are characterized by a unique type of caniniform heterodont dentition (Evans et al. 2001). When identifying a model taxon illustrating plesiomorphic condition in Lepidosauria, ideally one would turn to the most basal clade of squamate radiation – the Gekkota (Vidal & Hedges, 2005; Wiens et al. 2010). The dentition of gekkonids fits well with the expected plesiomorphic condition in squamates (small numerous and morphologically uniform teeth with pleurodont attachment); however, the Gekkota show some features by which they differ from more derived clades. They have (i) a short tooth crown compared with the height of their dentine shafts and (ii) bicuspid crowns. The lingually tilted cusps characteristic of gekkonids are also reported in caecilians and extinct dissorophoid amphibians (Sumida & Murphy, 1987). Tentatively, this may suggest that the dental specificities of gekkonids are true autplesiomorphies and, hence, this group closely approaches the basal condition of amniote dental evolution.

This is the first reason why the Madagascan ground gecko, Paroedura picta, has been chosen for a detailed analysis of its developing dentition. The second reason is its reproductive strategy, which makes the embryos accessible and amenable for study. Recently, squamate species have taken centre stage with tooth development studied in a skink, corn snake, python, pit viper, bearded dragon, and leopard gecko (Delgado et al. 2005; Buchtova et al. 2008; Vonk et al. 2008; Zahradnicek et al. 2008; Handrigan & Richman, 2010, 2011; Handrigan et al. 2010). Although useful models for specific aspects of tooth development, these species provide problems as standard model taxa for developmental research as their reproductive characteristics do not allow for a controlled harvesting of embryonic material. In contrast, the Madagascan ground gecko, P. picta, is emerging as a suitable choice (Noro et al. 2009). The adults are small and easy to keep in captivity, with breeding colonies currently set up in the Czech Republic, Japan and UK. Eggs are laid relatively early in development, when compared with other reptiles, such as anole and python (Buchtova et al. 2007; Sanger et al. 2008), allowing for stages of neurulation and neural crest migration to be studied. Importantly, the eggs have calcified hard shells (Kratochvil et al. 2006) unlike the more leathery shells of most reptiles, allowing for the possibility of windowing eggs during development, in a similar manner to the chick (Noro et al. 2009). Such windowing is possible in leathery eggs but the mortality rate is extremely high due to the problems of re-sealing, making most experiments non-viable (Nagashima et al. 2007). The hard nature of the shells also allows the eggs to be individually moved from the place of laying to the lab for experimentation, something which can be a problem with softer eggs, which are often glued together in clutches and cannot be separated for experimentation. Two eggs are laid at a time every 7–10 days throughout the year, providing a constant supply of eggs. Anolis lizards have been suggested as a potential model organism (Sanger et al. 2008) but have the disadvantage of being seasonal (Lee et al. 1989), with one egg being laid every 1–4 weeks during the breeding season (Andrews, 1985). Paroedura picta thus encorporates many of the characteristics of a successful model organism and a staging series has recently been produced (Noro et al. 2009).

Paroedura picta possesses teeth on the mandibular, maxillary and pre-maxillary bones. The palatal bones are free of teeth, as in most reptilian species. The functional dentition is polyphyodont with homodont teeth pleurodontly ankylosed to the bone. This type of ankylosis is the general condition for extant reptiles, except agamids and chameleons with acrodont ankylosis and archosaurs with a thecodont type of tooth attachment (Edmund, 1969). The functional teeth are bicuspid and are covered by a non-prismatic enamel layer. In contrast to the functional teeth, a number of null generation, non-functional teeth form during embryonic development, similar to those observed in other reptiles (Leche, 1893; Lemus et al. 1980; Westergaard & Ferguson, 1986, 1990; Delgado et al. 2005). These null generation teeth are unicuspid with a reduced layer of enamel or lacking enamel completely. Information about the fate of null generation teeth is rather sporadic, and therefore while investigating the development of the functional dentition we also investigated the development and fate of these teeth.

Material and methods

Preparation of biological materials

Seventy embryos of gecko P. picta at different stages, two juveniles and one adult specimen were used during this investigation. A P. picta staging table of normal development was used for the staging (Noro et al. 2009) and anotated as days post-ovulation (dpo). Eggs were incubated in dry climaboxes at 28 °C. Embryos were killed by MS222 and fixed in 4% para-formaldehyde (PFA) overnight. The juveniles and adult died naturally and came from the collection of the Department of Zoology, Charles University, Czech Republic. These had been fixed in 70% ethanol for an extended period.

Scanning procedure

For scanning electron microscopy (SEM) the jaws of juvenile and adult specimens were cleared of soft tissue, dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, placed in 100% acetone, then air dried and glued onto a copper support. Specimens were coated with a thin layer of gold and observed by a JEOL SEM 6380 LV operating at 25 kV. Specimens for microCT (computerised tomography) were scanned using a GE Locus SP microCT scanner. The specimens were scanned to produce 14-μm voxel size volumes, using an X-ray tube voltage of 80 kVp and a tube current of 80 μA. The specimens were characterised by making 3D isosurfaces, generated using microview software (GE). A faxitron X-ray was used to image the whole head.

Histology

Two histological methods were used. The specimens for the alizarin red S staining were washed in distilled water and stained in alizarin red S staining solution in 1.5% KOH for 2 days. After staining the specimens were cleared in 50% glycerol for 1 day and then stored in 100% glycerol. Calcified teeth were observed from the lingual view. The specimens containing older bone that were used for histology staining were decalcified in 5% EDTA in 10% formaldehyde at room temperature (RT). The time of decalcification ranged from 1 week to several weeks depending on the level of ossification. Bone-free specimens or decalcified specimens were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and subsequently dehydrated through an ethanol series, embedded in paraffin wax and frontally sectioned at 6–10 μm. Sections were stained with a trichrome stain (alcian blue, haematoxylin, sirrus red) and mounted in DEPEX. Complete series of frontal sections were used to reconstruct dental development and to follow the development of the different tooth types.

Results

Dental pattern during development

To understand how the pattern of the teeth is laid down during development we followed tooth initiation patterns in the developing mandible. The first teeth to develop were the single generation of non-functional (null generation) teeth. These were small in size and formed near to the oral surface. The first tooth formed before 14 dpo in the rostral part of the jaw, with the second tooth forming caudal to the first. Subsequent null generation teeth were initiated both rostral and caudal to these first teeth, with new tooth buds initiated close to the oral epithelium until around 35 dpo (Fig. 1A–C above dotted line). All null generation teeth were replaced by a functional tooth during embryonic development and therefore did not play a role in mastication at any stage. The null generation teeth formed 15 tooth positions within each mandible by 40 dpo, approximately half of the tooth positions in place at hatching (blue numbers in Fig. 1D). The remaining tooth positions were established by the functional teeth, without the presence of an earlier null generation tooth (black numbers in Fig. 1D). Formation of a null generation tooth is therefore not a pre-requisite for later development of a functional tooth.

Fig. 1.

Dental laminas of mandibles at different stages of development with mineralised tooth germs showing the developing dental pattern. Mandibles orientated rostral to the right, caudal to the left. Mineralised tooth germs were visualised by alizarin red and viewed from the lingual side, oral side uppermost. (A–D) Dissected dental laminas. The dotted line (A–D) separates the more superficially developing single generation of non-functional (null) tooth germs (above the line) from the more deeply positioned functional tooth germs (below the line). Dental lamina at (A) 30 dpo; (B) 32 dpo; (C) 35 dpo; (D) 40 dpo. Green arrows mark functional teeth that will replace the null generation teeth. Black arrows in (D) indicate functional teeth that will replace the first set of functional teeth. The numbering show the tooth positions at hatching. The black numbers indicate tooth positions where tooth families are established by functional teeth, and the blue numbers indicate tooth positions established by null generation teeth. (E) Ankylosed teeth in the jaw before hatching at 60 dpo. Scale bar: 500 μm.

From 30 dpo, the first functional teeth were visible along the dental lamina, positioned deeper within the jaw than the null generation teeth (Fig. 1A–C below dotted line). As some of these teeth replace the null generation teeth, they can be thought of as being in the same tooth family as the null generation teeth (green arrows Fig. 1C,D). By 40 dpo, teeth that would replace the first functional generation had started to mineralise in some tooth positions (black arrows Fig. 1D). By 60 dpo, the first signs of tooth resorption of the functional dentition were visible as the successional teeth started to move orally in some areas of the jaw (Fig. 1E). By the end of embryonic development there were approximately 30 functional dental positions in each half of the mandible, the number correlating to the size of the animal at hatching (Fig. 1E). During postembryonic stages the number of tooth positions increased, with approximately 50 teeth on each side of the mandible (Fig. 9A–C).

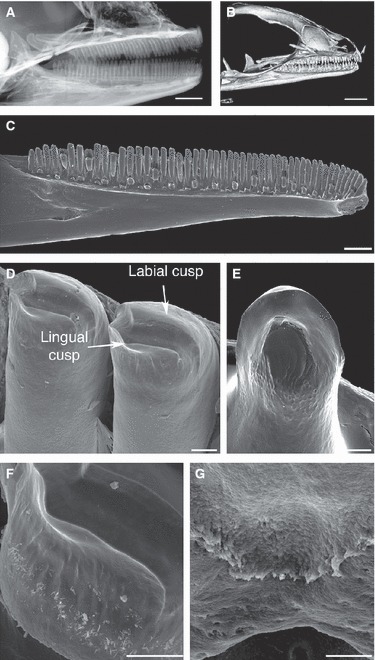

Fig. 9.

Analysis of the adult dentition in Paroedura picta. (A) Faxitron X-ray image of an adult head showing uniform teeth in maxillae and mandibles. (B) MicroCT image of adult head. (C–G) SEM images of adult mandible. (C) Adult mandible showing pleurodontly ankylosed homodont teeth. (D) Crown morphology of an adult tooth shows a bicuspid shape, with two cusps divided by a groove. (E) Crown morphology of an egg tooth (early hatchling) shows two rounded crests. (F) Vertical enamel ridges line the cusps. (G) A serrated crest forms between the bone and tooth base on the lingual side of the ankylosis. Scale bars: (A) 2 mm, (B) 3 mm, (C) 1 mm, (D–G) 50 μm.

Embryonic development of the single generation of non-functional (null generation) tooth germs

The first and second null generation teeth of each jaw quadrant were initiated directly from the oral epithelium before 14 dpo (Fig. 2A). The first tooth in the mandible formed before Meckel's cartilage appeared, and the second tooth formed during the first signs of cartilage chondrification. The first teeth in the maxilla were initiated slightly earlier than the mandibular teeth. The first sign of tooth development was a thickening of the oral epithelium, around which the mesenchyme started to condense (Fig. 2A). The enamel organs of the first two teeth in each jaw quadrant projected out from the oral epithelium into the oral cavity as they developed, forming an inverted bud, as has been described for archosaurian teeth (Fig. 2A,B; Westergaard & Ferguson, 1986). As these first null generation teeth reached the cap/bell stage, the dental lamina started to form up against the first null generation teeth, and continued to invaginate into the mesenchyme. The enamel organ of the first and second tooth germs sunk into the mesenchyme as the dental lamina grew inwards and these first teeth no longer markedly projected out from the oral epithelium (Fig. 2C). At this stage, the centre of the inner dental epithelium of the first tooth was in direct contact with the oral ectoderm. The cells of the inner dental epithelium were short columnar to cuboidal and did not form typical polarised ameloblasts, in contrast to functional teeth in the crown area at later stages. The cells of the dental papilla, neighbouring the inner dental epithelium, appeared rounded and were larger than the rest of the mesenchymal cells of the papilla, indicating that they had started to differentiate into odontoblasts (Fig. 2C). In other positions in the jaw the null generation tooth germs did not start to initiate until after dental lamina formation. In these cases the tooth germs were intricately connected with the extending dental lamina, and were initiated from the labial side at the base of the lamina (Fig. 3A–D). These tooth germs did not markedly project from the oral epithelium surface. The dental mesenchyme weakly condensed around the tooth germs, which became more pronounced by the cap stage (Fig. 3B,C). The tooth germ of these early developing teeth underwent the classic transition from the cap to bell, with the formation of a limited number of odontoblasts and the deposition of dentine (Fig. 3D). In some cases the functional tooth was observed developing directly over the tooth of the null generation, highlighting the large size difference between the two tooth types (Fig. 3E). These null generation tooth germs that were associated with the forming dental lamina often appeared embedded directly into the lamina with limited outer dental epithelium (Fig. 3D,E). Cells of the inner dental epithelium elongated but remained unpolarised and no evidence of enamel deposition was observed (Fig. 3D,E).

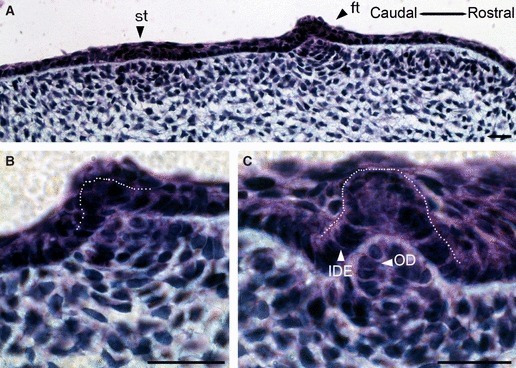

Fig. 2.

Development of the first null generation teeth from the oral surface. (A) The first tooth (ft) and second tooth (st) start to form at the oral surface, and the underlying mesenchyme starts to condense at 13 dpo. (B) High-power view of the first tooth. The cells of the dental papilla are organized into layers adjacent to the oral epithelium. (C) During later development these teeth shift deeper into mesenchyme and no longer stick out into the oral cavity. The dental papilla cells adjacent to the IDE mature into odontoblasts. ide, inner dental epithelium (outlined by dotted line); od, odontoblast. Scale bar: 10 μm.

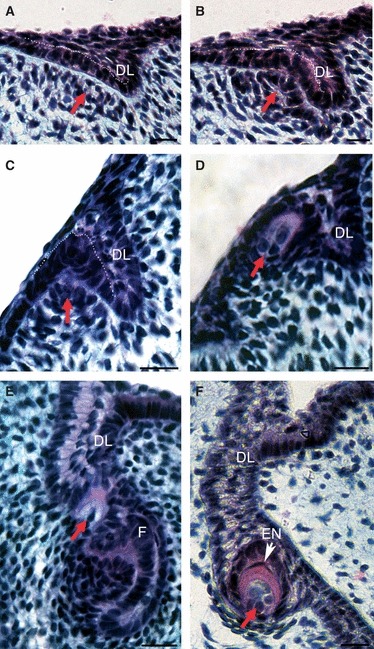

Fig. 3.

Development of later initiating null generation teeth within the mandible. (A–F) Frontal section through mandible with lingual on right, labial on left. (A) A null generation tooth germ with characteristic superficial position developing on the labial base of the invaginating dental lamina (DL). Tooth germ in the rostral part of the jaw at 14 dpo. Arrow indicates condensing mesenchyme. (B) Cap stage with clear condensing mesenchyme (arrow). Tooth germ in the rostral part of the jaw at 16 dpo (C) Early bell stage at 22 dpo. (D) Mineralised tooth germ showing dentine formation in red/purple at 18 dpo. (E) A late initiating null generation tooth germ (red arrow) sitting on the dental lamina above a functional tooth (F). Note the large size difference between the tooth germs. (F) A late initiating null generation tooth germ (35 dpo) with a thin enamel coat (EN). White arrow, polarized ameloblasts (am). These teeth have more differentiated cervical loops (surrounding red arrow) in comparison with the superficial teeth. (A–C) White dotted line outlines the inner dental epithelium. Scale bar: 10 μm.

The last null generation teeth to be initiated within the jaw were located at the growing front of the dental lamina deeper within the mesenchyme. The enamel organ of these teeth did not fully sink into the dental lamina, as was observed with null generation teeth that had formed earlier in other positions within the jaw, and as a result the outer dental epithelium and cervical loops were clearly developed (Fig. 3F). Elongated ameloblasts were apparent, and a thin layer of enamel was evident capping the dentine in some examples (Fig. 3F). In a few cases these teeth appeared to attempt to ankylose to the maxillary bone, although this was not observed in the mandible (Fig. 5E). The ankylosis was observed at the edge of the bone, or the tooth germs of the null generation became completely encapsulated by the developing maxillary bone (Fig. 5E). Within these null generation teeth there was no evidence of vascularisation or innervation of the pulp (Fig. 3F).

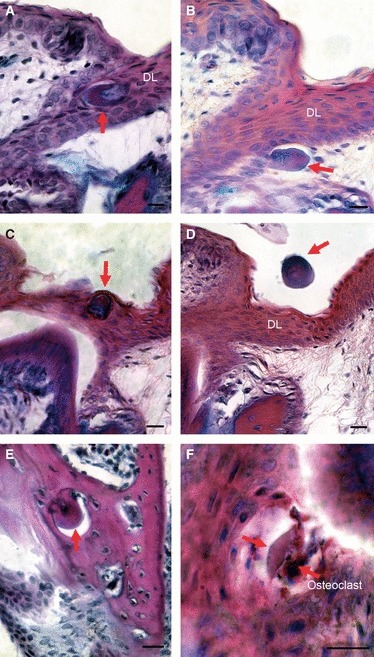

Fig. 5.

The fate of the null generation teeth. Trichrome stained sections. (A–D,F) show teeth in a mandible, whereas (E) is the maxillary bone in an embryo close to hatching. (A) Null generation teeth are very often enclosed in the dental lamina where they can turn around so that the dentine faces aborally. (B) Null generation tooth pushed out of the dental lamina. (C) Some teeth are pushed out orally as the functional tooth that forms underneath erupts. (D) In some cases these teeth are shown floating free in the oral cavity having been shed into the mouth. (E) In a few cases, later-initiating null generation teeth appeared to become ankylosed to the bone of attachment in the maxilla. Here these tooth germs have become nearly completely encapsulated by bone. (F) Some of the null generation teeth are resorbed by osteoclast-like cells from the outside in. Red arrows, null generation teeth. DL, dental lamina. Scale bar: 10 μm.

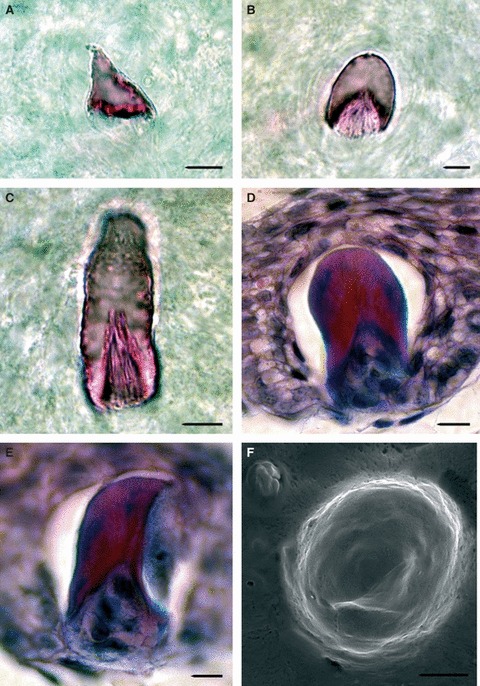

The null generation dentition formed simple unicuspid teeth, in contrast to the bicuspid functional dentition (Fig. 4A–F). In some cases the teeth were conical (Fig. 4A), others were rounded (Fig. 4B,D), cylindrical (Fig. 4C) or hooked (Fig. 4E). The different shapes appeared to correlate with different regions of the jaw, with the cylindrically shaped teeth associated with the rostral area of the jaw. In the later initiating null generation teeth, a small ridge was visible on the tooth cusp by SEM, indicating production of enamel (Fig. 4F), agreeing with the enamel layer observed by histology (Fig. 3F).

Fig. 4.

The shape of null generation teeth. Null generation teeth from mandibles of older embryos (A–E) and maxillary bone of freshly hatched juvenile (F) visualised by alizarin red S (A–C), trichrome staining on frontal sections (D,E) and by SEM (F). Shapes of teeth: (A) conical, (B,D) rounded, (C) cylindrical and (E) hooked. (F) The later null generation teeth often have small ridges on their surface. Scale bar: 10 μm.

Fate of null generation teeth

The fate of null generation teeth in reptiles is unclear. It has been hypothesised that they might be expelled by being pushed out of the oral cavity, or absorbed by the surrounding tissue (Westergaard & Ferguson, 1986). To identify the fate of the large number of null generation teeth in P. picta, these teeth were followed during late embryonic development. Interestingly, depending on their site of initiation within the jaw, the null generation teeth underwent a number of different fates. Those tooth germs that were initiated superficially, directly above a functional tooth, were incorporated into the enamel organ of the successive functional tooth and then were pushed out into the oral cavity as the functional tooth erupted (Fig. 5C,D). In other cases the null generation teeth became completely enclosed by the dental lamina, and were moved around through the movement of the growing lamina (Fig. 5A) or moved out of the dental lamina (Fig. 5B). These teeth appeared to be removed by osteoclast-like cells, which surrounded the tooth rudiments and resorbed them (Fig. 5F). Finally, those null generation teeth that ankylosed to the forming maxilla, and were surrounded by the bone, were incorporated into the bone itself and appeared to become part of the functional jaw (Fig. 5E).

Embryonic development of the functional dentition

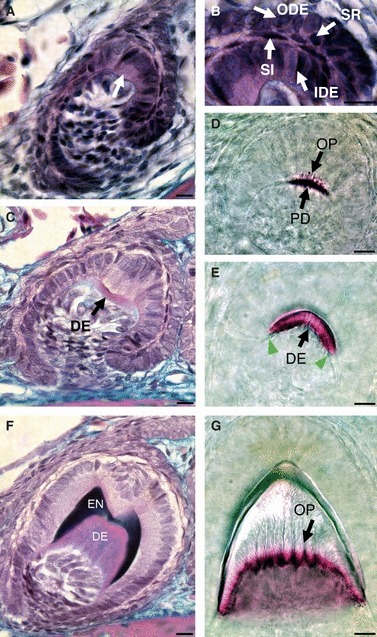

Unlike the superficial null generation teeth, the functional teeth developed from the dental lamina deep within the forming jaw. The first buds of the functional dentition were observed before 20 dpo, less than a week after the first null generation tooth germs were observed. The cells at the top of the dental lamina on the labial side formed a bud, surrounded by condensing mesenchyme (Fig. 6A,B). During the bud-cap transition, three layers became distinct within the enamel organ: the inner dental epithelium, outer dental epithelium and a medial dental epithelium between the two (Fig. 6C,D). Cap stage functional teeth were observed from 20 dpo. The shape of the tooth germ did not change significantly as it moved from cap to bell, this transition being marked by the differentiation of the inner dental epithelium into ameloblasts and adjacent mesenchyme into odontoblasts (Fig. 7A). At this stage the medial dental epithelium was composed of two cell layers: rounded and flattened cells (Fig. 7B). The rounded cells, which formed between the flattened cells and the outer dental epithelium, formed the stellate reticulum. The darkly staining flattened layer of cells, located between the stellate reticulum and the inner dental epithelium, appear to represent the stratum intermedium, a cell type not previously observed in lizards (Delgado et al. 2005). The cervical loops developed asymmetrically, with the lingual loop being larger than the labial (Fig. 7A,C). As the tooth reached the late bell stage the cells of the inner dental epithelium became further elongated and polarised, with the nuclei situated at the proximal pole (Fig. 7C). The layer of mature ameloblasts spread out from the centre of the inner dental epithelium of the tooth towards the cervical loops. This wave was matched by a similar wave of odontoblast differentiation and pre-dentine production from the centre of the dental papilla out towards the cervical loops (Fig. 7C–E). Unlike the null generation tooth germs, the functional teeth were vascularised during the late mineralisation stages with the formation of blood vessels in the dental pulp (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 6.

Functional tooth development: bud and cap stage. (A) Functional tooth development is initiated deeper in the mesenchyme from the end of the growing dental lamina. (B) Detail of epithelial bud surrounded by the condensing mesenchyme (M) at 24 dpo. (C) The cap stage at 26 dpo. (D) Detail of the cell organisation of the enamel organ and mesenchymal cells in the dental papilla at the cap stage. DL, dental lamina; CL, cervical loop; DP, dental papilla; IDE, inner dental epithelium; MDE, medial dental epithelium; ODE, outer dental epithelium. Scale bar: 100 μm.

Fig. 7.

Crown formation in functional teeth: from the bell stage to mineralisation. (A–C,F) Frontal sections stained by trichrome. (D,E,G) Alizarin red preparations from the mandible, lingual (side) view. (A) Bell stage. The first ameloblasts differentiate in the centre of the IDE overlying the differentiating odontoblasts, where a bulge is visible (arrow). (B) Detail of the enamel organ at the bell stage. The enamel organ comprises several layers: inner dental epithelium (IDE), outer dental epithelium (ODE), flattened stratum intermedium cells (SI) and rounded stellate reticulum cells (SR). (C) Slightly more advanced bell stage, showing the first signs of pre-dentine (DE) deposition, which occurs prior to enamel formation. Note the tooth shape is very constant between A and C. The bulge in the centre of the IDE is still apparent. (D,E,G) Successive tooth crown mineralisation (side view). (D) Numerous odontoblastic processes (OP) are observed during pre-dentine (PD) production. (E) Dentine formation (DE) spreads out from the centre of the IDE (white arrows). (F) The dome of dentine (DE) is capped by enamel (EN) which is laid down asymmetrically to create the two cusps. (G) Late-stage tooth germ. The lines in the dentine show the branched odontoblastic processes (OP) and the saw-like shaped front of dentine adjacent to the odontoblasts. Scale bar: 10 μm.

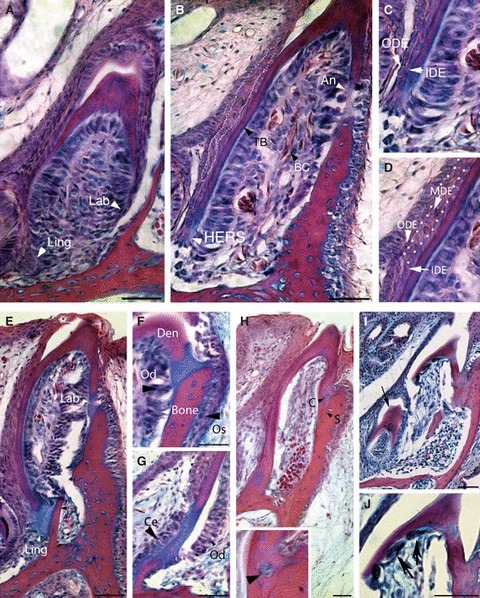

Fig. 8.

Development of the tooth base. (A–D) 45 dpo. (A) Asymmetrical growth of the enamel organ is important for formation of the tooth base. The lingual side (Ling) of the enamel organ is longer and extends deeper than the labial one (Lab). (B) The labial side of the tooth base (TB) starts to undergo ankylosis (An) before the lingual side. Blood vessels containing nucleated blood cells (BC) populate the dental pulp. White arrrowheads in A and B point to the ends of the tooth base on both sides. (C) The lower end of the enamel organ on the lingual side is formed by HERS, a double layer of cells made from the inner dental epithelium (IDE) and outer dental epithelium (ODE). (D) The majority of the tooth base is formed by a three-layered enamel organ with a central medial dental epithelium (mde), outlined with white dots in B and D. (E–G) 50 dpo; (H–J) 60 dpo. (E) The bone and tooth are initially joined by an acellular matrix before mineralisation of the join. Ling, lingual; Lab, labial. (F) High power magnification of the labial side showing the first signs of ankylosis. Os, osteoblasts; Od, odontoblasts; Den, dentine. (G) High power magnification of the labial side. Ce, cementoblasts; Od, odontoblasts. The red stain shows bone and dentine, and the blue stain shows matrix deposition at the site of connection. (H) The sites of fusion become mineralised and stains red with alizarin red. The tooth is now firmly attached to the bone. Some cells are observed trapped within the join (C), highlighted at bottom of image (black arrow). A thin suture between the bone and dentine is apparent (S). (I) Resorption of the functional tooth in the maxillary bone. The resorption starts from the lingual side, where a successional tooth (arrow) waits to become functional. The labial side remains attached to the bone until the resorption of the lingual enamel-free dentine base is complete. (J) Resorption of the lingual side in detail. Big multinucleated osteoclast-like cells are found lining the inner side of the lingual dentine base (black arrows). Scale bar (A,B,E–J): 100 μm.

Crown formation: development of two cusps

At the centre of the inner dental epithelium a bulge of cells was observed, in a similar position to the enamel knot of mammalian cap stage teeth (Jernvall et al. 1994). Such a bulge was not reported in unicuspid snake teeth (Buchtova et al. 2008) but has recently been observed in the leopard gecko, Eublepharis macularius (Handrigan & Richman, 2011). In mammals the enamel knots direct folding of the inner enamel epithelium but no folding of the epithelium was observed in P. picta, and dentine was laid down adjacent to the inner dental epithelium in a unicuspid shape (Fig. 7F). By the bell stage, the mature odontoblasts were large, elongated and polarised (Fig. 7C), with odontoblastic processes reaching toward the enamel–dentine junction (Fig. 7D,G). In contrast to the dentine layer, the enamel layer was asymmetrically deposited, with low production of enamel at the centre of the inner dental epithelium, in the area corresponding to the earlier bulge. The asymmetric production of enamel by the inner dental epithelium resulted in the creation of the bicuspid pattern (Fig. 7F). The bicuspid shape was clear in frontal section, although not evident from sagittal views (Fig. 7F,G). All functional teeth observed during embryonic development had the classic double cusp crown morphology observed in adults when viewed in frontal section.

Tooth base development and ankylosis of the functional dentition

As the tooth crown started to take shape, the tooth base started to develop (Fig. 8A). Along the shaft of the tooth the epithelial tissue was composed of three layers: the inner, medial and outer dental epithelium (Fig. 8B,D). At the tooth base, however, the medial layer disappeared, so that the inner dental epithelium contacted the outer dental epithelium forming a two-layered structure, similar to that observed during mammalian tooth development with the formation of Hertwig's epithelial root sheath (HERS) at the bottom of the cervical loops (Fig. 8C). The HERS on the labial side of the tooth was much shorter than on the lingual side. The cells of the inner dental epithelium adjacent to the medial dental epithelium had a cuboidal shape, whereas in the HERS area these cells were flattened up against the outer dental epithelium (Fig. 8C). The adjacent papilla cells differentiated as odontoblasts and produced the dentine of the tooth base. The functional teeth were observed fusing to the maxilla and mandible from around 50 dpo. Ankylosis was first observed on the labial side (Fig. 8B). No evidence of HERS disintegration, such as isolated rests of epithelial cells, as described in mammals, was observed at the base of the tooth in any of our specimens. Odontoblasts were evident on the inner side of the tooth, adjacent to the dentine and along the site of ankylosis, and osteoblasts were found lining the jaw-bone on the outer surface (Fig. 8E,F). At the site of ankylosis, cells resembling cementoblasts lined the junction between the tooth and bone on the opposite side to the odontoblasts, under the epithelial HERS (Fig. 8G). The matrix joining the tooth and bone therefore appeared to be created by a mix of dentine, bone and cementum matrix. These tissues mineralised and firmly fixed the tooth in position. A distinct suture line between the dentine and bone was visible on both sides of the tooth (Fig. 8H). Interestingly, in some cases cells were observed trapped between the fusing mineralised tissue (Fig. 8H, inset). During ankylosis of the tooth to the bone, the enamel organ overlying the mineralised tissue flattened and degraded to leave an open path for the tooth to emerge (Fig. 8E). Eruption of the functional dentition was observed from 60 dpo (Fig. 8H).

Even as the functional dentition was starting to erupt, the replacement tooth behind could be seen pushing up against the previous tooth, leading to resorption of the dentine and remodelling of the bone (Fig. 8I). The replacement tooth moved up on the lingual side of the previous tooth in the sequence, while the labial tooth-bone connection remained solid (Fig. 8I). Osteoclast-like cells could be observed on the inner surface of the first tooth lining the dentine next to the site of resorption (Fig. 8J). These osteoclast-like cells were only observed on the lingual side of the tooth, correlating with the pattern of resorption on the lingual side only.

Final morphology of the functional dentition

The fully developed functional teeth of P. picta were similar in shape throughout the jaw (homodont) and were bicuspid at the tips (Fig. 9A–D). The rather shallow cusps were situated labially and lingually on the tip of the crown (Fig. 9D,F). The tooth crown formed one-third of the total tooth length. The sides of the crown were augmented by a sequence of low vertical enamel ridges (Fig. 9F). There were two egg teeth in the premaxilla at hatching, which, in contrast to the rest of the dentition, were not bicuspid but possessed two rounded enamel crests (Fig. 9E). The tooth base was formed from dentine and was pleurodontly ankylosed to the lingual side of the bone of attachment. A serrated crest was visible at the point where the tooth met the bone (Fig. 9G).

Discussion

Dental pattern in P. picta follows an alternating pattern

The dental pattern was initiated in P. picta, as in other lepidosaurians and archosaurs, with the development of the first tooth, termed the dental determinant. The initiation of the dental determinant is then proposed to switch on the periodic dental program and, in keeping with this, waves of initiation of the following teeth were observed from 14 dpo in P. picta, spreading from the first tooth forwards and backwards. Interstitial teeth were formed in the growing spaces between earlier initiated teeth, as previously shown in archosaurs (Osborn, 1974, 1998). In P. picta the first and second teeth were initiated from the oral epithelium before the dental lamina appeared, the first stages of tooth formation looking morphologically similar to the dental placode in the alligator (Westergaard & Ferguson, 1986). In Alligator mississippienssis, Sphenodon punctatus, Cnemaspis kandiana, Lacerta viridis and Iguana tuberculata several first null generation teeth project markedly from the surface of the oral epithelium (Leche, 1893; Westergaard & Ferguson, 1986; Westergaard, 1988b). In contrast to these species, in Lacerta agilis and Anguis fragilis these teeth project from the surface of oral epithelium only slightly and only for a short time period and their later development is connected with the dental lamina (Westergaard, 1988a). In P. picta the first tooth germs project from the oral surface until the late cap stage and then sink into the mesenchyme as the dental lamina forms and invaginates inwards. The significance of this projection is unclear and is probably a mechanical consequence of tooth development at the oral surface. As some of the early null generation teeth developed before the dental lamina had formed, the dental lamina is not necessary for tooth development but it is important for the development of the polyphyodont dental pattern. In P. picta the first two null generation teeth within each jaw quadrant developed directly over the place where the dental lamina will later form, indicating the odontogenic potential of this region of oral tissue. As the waves of intiation spread throughout the jaw, the later developing null generation tooth germs were initiated deeper within the mesenchyme from the dental lamina. Generally in reptiles, the later initiated teeth develop closer to their most mature neighbours and are bigger than earlier teeth (Westergaard & Ferguson, 1986). This rule regarding the size difference between early and late initiated teeth was not apparent in the functional teeth in P. picta, but within the single generation of null generation tooth germs, those that were initiated early were smaller than those initiated later. In addition to being larger, the later initiating null generation tooth germs developed to a later stage of cytodifferentiation and incorporated more cells into the dental papilla. In contrast in Chalcides viridanus (Delgado et al. 2005), the number of tooth positions was not fixed at hatching but increased postnatally as the jaw increased in size.

The first generation of developing tooth germs in P. picta are non-functional

The development of null generation tooth germs was previously described in both archosaurs and lepidosaurian reptiles (Leche, 1893; Osborn, 1971; Westergaard & Ferguson, 1986; Sire et al. 2002) and in sharks (Reif, 1976). The single generation of non-functional teeth observed in P. picta, other reptiles and sharks may represent the remnants of a past functional dentition that has become redundant. In those non-mammalian species that possess rudimentary teeth, such teeth are associated with a relatively long embryonic gestation and the absence of a small larval first dentition (Sire et al. 2002). As gestation was extended in these groups, the need for a set of small rapidly developing teeth would have been reduced, allowing for the development of a larger first set of functional teeth. The rudimentary teeth observed may thus be remnants of this first set of small teeth. A functional first set of small teeth are observed in young larvae of Teleostei and Caudata. Like the null generation teeth of P. picta, these first generation teeth are smaller and simpler in shape compared with the later generations and the dental pulp is not vascularised or innervated (Huysseune & Sire, 1997; Sire et al. 2002; Davit-Beal et al. 2006). These early functional teeth of urodele and actinopterygian larval stages also form dentine without odontoblastic processes and thin enameloid (Sire et al. 2002) in a similar manner to the null generation teeth of P. picta. Poor development of odontoblasts and the inner dental epithelium, resulting in a lack of enamel, is also observed in the first generation of teeth in archosaurs (Westergaard & Ferguson, 1986). It is possible that the lack of a vascular system in the null generation tooth germs limited their growth, explaining their small size. In addition to lack of vasculature, no evidence of innervation was observed in the P. picta null generation teeth, although to show this definitively, a neuronal marker or stain should be used. There may therefore be a general trade off between tooth size and tooth maturation. However, it is likely that in such small teeth, nutrients are able to reach all layers of the tooth by diffusion and so small teeth may simply not require a blood vessel network in the pulp.

The grade of null generation tooth development, from a simple dentine tooth to a dentine tooth covered by a thin layer of enamel, correlated with the time of initiation (later initiated teeth showed more complex development), and with the position where they were initiated (teeth that developed deeper within the dental mesenchyme showed more complex development). Thus it seems that the stage of development reached by a tooth is directed by the temporospatial context, perhaps driven by temporospatial differences in key signalling molecules and transcription factors active during development. A low level of Sonic hedgehog (Shh) signalling, for example, has been suggested to be responsible for the formation of superficially developing null generation teeth in the bearded dragon (Handrigan & Richman, 2010). A shift in the expression of such signalling factors during evolution may have therefore rendered early developing teeth non-functional.

Even though they are non-functional with respect to mastication, the tooth germs of the null generation may still play a role in the positioning of the dental lamina and organisation of the later functional dentition, and therefore may remain a key part of the patterning process. It is therefore interesting to note that half, although not all, the functional dentition replaces a null generation tooth. The null generation teeth, as the first to develop, appear to play the role of the dental determinant, setting up the patterning of the later functional dentition. Such as role would explain why these null generation teeth are so common and abundant in number within reptile species.

Null generation teeth are not restricted to reptiles and sharks, as aborted tooth germs are also apparent during mammalian tooth development. For example, in the mouse, rudimentary tooth germs develop in the diastema distal to the first molar. These tooth germs are thought to be remnants of ancestral premolars, a tooth type not found in mice, and undergo apoptosis at the bud stage. It has been proposed, however, that these null generation teeth initiate the sequential development of the mouse molars, and therefore have an essential early patterning role (Prochazka et al. 2010). In the shrew the deciduous tooth germs in some positions are aborted to make way for the permanent tooth germs before they become functional (Jarvinen et al. 2008). Here it has been proposed that the later-developing functional dentition suppresses the first generation of teeth, something that may also be occurring in reptiles.

Fate of the null generation teeth depends on their site of initiation

The fate of superficially developing teeth has been described in archosaurs to involve absorption and expulsion (Westergaard & Ferguson, 1986, 1990). The first teeth of the alligator null generation disappear below the jaw surface, their enamel organs disintegrate and the dentine is resorbed. These teeth can persist for some time in the mesenchyme before resorption (Westergaard & Ferguson, 1986). Interestingly, we observed no single fate for the null generation teeth, which were expelled from the oral cavity, incorporated into the enamel organ of functional teeth or the maxillary bone, or resorbed. The eventual fate of these teeth appeared to depend on the site where the tooth germ initiated. Non-functional teeth developing close to the surface were expelled into the oral cavity with the eruption of the functional dentition, whereas more deeply initiated teeth were resorbed. Later-developing null generation teeth that initiated from the dental lamina appeared to attempt ankylosis to the bone, and as a result were completely enveloped in bony tissue. In contrast to observations in alligators (Westergaard & Ferguson, 1986), we did not find evidence for osteoclasts acting inside the dental papillas of the null generation teeth, which might be due to the small size of the dental papillas as well as the large size of multinucleated osteoclast-like cells. Osteoclast-like cells, however, were observed surrounding null generation teeth, resorbing from the outside in.

Differentiation of cell layers during odontogenesis in reptiles

In mammals an intermediate layer is observed between the ameloblast layer of the inner dental epithelium and the stellate reticulum, known as the stratum intermedium. The cells in this layer are spindle-shaped, lying perpendicular to the ameloblasts, and have been proposed to function with the ameloblasts in the mineralisation of the enamel (Nakamura et al. 1991). This layer has been described in alligators and in the actinopterygian lineage (Sasagawa & Ishiyama, 2002) but was not previously described in lepidosaurians (Ogawa, 1977; Sire et al. 2002; Delgado et al. 2005; Buchtova et al. 2008; Handrigan & Richman, 2010). In P. picta, we see a layer of flattened cells that lie in the position of the stratum intermedium in both late-developing null generation and functional tooth germs, suggesting that some squamate reptiles do possess this dental layer. The timing and position of the stratum intermedium-like layer appeared similar to the stratum intermedium in mammals (Koyama et al. 2001). Difference between these layers, however, also exist, as the stratum intermedium-like structure in P. picta is still present during the late mineralisation phasis in P. picta, whereas in mammals the stratum intermedium cells are only present until ameloblast differentiation (Koyama et al. 2001). In P. picta the presence of a stratum intermedium-like layer and the formation of enamel was highly correlated, suggesting the importance of this layer for enamel deposition in this reptile. The stratum intermedium layer is therefore found in mammals, fish and reptiles and could represent the plesiomorphic character of jawed vertebrates.

The stellate reticulum in P. picta is composed of rounded cells separated by big extracellular spaces, similar to that described in Ch. viridanus (Delgado et al. 2005). This layer is thin in P. picta and persists until late mineralisation stages. This layer is not fully differentiated at the tooth base, indicating its importance for ameloblast differentiation. A thin layer of stellate reticulum is also present in snakes (Buchtova et al. 2008). Such a thin stellate reticulum is therefore associated with reptile species that have narrow conical or cylindrical teeth, while species with larger, wider teeth have a more substantial, mammalian-like stellate reticulum (Handrigan & Richman, 2010).

The inner dental epithelium of P. picta is asymmetric. The lingual side is thinner and grows preferentially on the labial side. Similar asymmetrical growth was observed in Ch. viridanus (Delgado et al. 2005) and may be necessary for development of a pleurodont ankylosis.

Alternative morphogenesis of reptilian bicuspid teeth compared with the mammalian molar model

The functional teeth in P. picta are cyclindrical with a bicuspid crown covered by enamel, ornamented by enamel ridges. The bicuspid shape of the P. picta tooth was shown to be created by asymmetrical deposition of enamel over a unicuspid dome of dentine. This is in contrast to mammalian teeth, where tooth cusps are created by folding of the inner dental epithelium prior to deposition of dentine and enamel. Similar to mammalian teeth, however, P. picta was found to have a bulge at the centre of the inner dental epithelium, characteristic of an enamel knot. As this bulge in the inner dental epithelium has not been observed in unicuspid snake teeth but has been similarly identified in the leopard gecko, E. macularius (Handrigan & Richman, 2011), it is tempting to speculate that it plays a central role in cusp generation. Mammalian primary enamel knot markers, such as Shh, Edar and Bmp4, have been investigated in the snake but are found throughout the inner dental epithelium and not restricted to a specific population at the centre (Buchtova et al. 2008; Richman & Handrigan, 2011). In contrast, Bmp2 was localised to this bulge in E. macularius, but not the unicuspid snake or bearded dragon at the cap and bell stages, indicating this signalling factor may co-ordinate the formation of the two cusps (Handrigan & Richman, 2011). It would, therefore, be particularly interesting to analyse the expression of Bmp2 in the bicuspid P. picta, to confirm that this is a conserved mechanism to generate two cusps in squamates. The cusps in P. picta are created by asymmetrical deposition of enamel, with the bulge area producing less that the adjacent inner dental epithelium. Of interest, it has recently been shown that grooves in mammalian teeth, as observed in the cane rat and jumping mouse, are created by enamel-free areas, over a continuous base of dentine, and that similar enamel free areas create complex tooth shapes in African cichlid fishes (Ohazama et al. 2010). Asymmetrical deposition of enamel may therefore play a central role in creating complex cusp/ornament patterns on teeth throughout the vertebrates.

HERS formation at the reptilian tooth base

The tooth base, which is not covered by enamel, forms the main part of the tooth in P. picta, connecting the functional part of tooth, the crown, with the bone of attachment. The term ‘root’ for lepidosaurian reptiles is also sometimes used (McIntosh et al. 1968; Luan et al. 2006); however, this term is generally regarded as being specific for mammals and it should not be used for the reptilian tooth base (Peyer, 1986). The induction of root formation in mammals, odontoblast differentiation and root shaping are controlled by a bilayered extension of the cervical loop, known as Hertwig's root sheath (HERS; Selvig, 1963; Ten Cate, 1996). HERS cells may induce the dental follicle (sac) cells to mature into cementoblasts (Paynter & Pudy, 1958), influence the pre-cementoblast migration to the surface of the root (Thomas & Kollar, 1989), and may even transform into cementoblasts themselves (Huang et al. 2009). McIntosh et al. (1968) followed HERS formation in lepidosaurian reptiles and described that this layer covers the tooth base, except at the crown. In P. picta we observed that most of the developing tooth base was formed of three layers of enamel organ (inner, medial and outer dental epithelium) and not by bilayered HERS. A bilayer was only seen right at the apical end of the tooth base. The cells of the inner dental epithelium in the HERS area were flattened, a similar flattening being observed in mammals before HERS disintegration (Owens, 1978; Andujar et al. 1984). Disintegration of HERS and formation of epithelial rests has also been described in archosaurs, which have a gomphosis type of tooth attachment (McIntosh et al. 1968). Disintegration of HERs, however, was not reported in other lepidosaurian reptiles with an ankylotic type of attachment (Luan et al. 2006), and at the time of ankylosis, the apical end of the tooth base was found to be free of HERS (McIntosh et al. 1968; Luan et al. 2006). At ankylosis in P. picta the tooth base also appears free of HERS. It is possible that the HERS-like cells observed early on, do disintegrate but over a relatively short period of time that was missed in our staging series. Whether lepidosaurians have a disintegration of HERS like mammals and archosaurs is therefore still an open question.

In conclusion, there are many interesting questions relating to reptile tooth development to be addressed and P. picta is an excellent model for answering these. This paper has shown the presence of a stratum intermedium, the formation of HERS, and the creation of a bicuspid crown during the development of the functional teeth, and has illustrated the large number of null generation teeth that develop before initiation of the functional teeth. The next step is to investigate the cellular dynamics and signalling molecules that create and shape the different teeth. Genes involved in development have started to be cloned in P. picta (Noro et al. 2009), opening up a wealth of interesting new avenues to explore.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Lukáš Kratochvíl, Zuzana Starostová and Hana Jirků for providing us with samples of P. picta. This work was supported by the Grant Agency of the Academy of Sciences, grant KJB601110910 and CZ: GA CR: P305/12/1766.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- Andrews RM. Oviposition frequency of Anolis carolinensis. Copeia. 1985;1:259–262. [Google Scholar]

- Andujar MB, Magloire H, Grimaud JA. Fibronectin in basement membrane of Hertwig's epithelial sheath. Light and electron immunohistochemical localization. Histochemistry. 1984;81:279–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00495639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchtova M, Boughner JC, Fu K, et al. Embryonic development of Python sebae – II: craniofacial microscopic anatomy, cell proliferation and apoptosis. Zoology (Jena) 2007;110:231–251. doi: 10.1016/j.zool.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchtova M, Handrigan GR, Tucker AS, et al. Initiation and patterning of the snake dentition are dependent on Sonic hedgehog signaling. Dev Biol. 2008;319:132–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffetaut E, Dauphin Y, Jaeger JJ, et al. Prismatic dental enamel in theropod dinosaurs. Naturwissenschaften. 1986;73:326–327. doi: 10.1007/BF00451481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davit-Beal T, Allizard F, Sire JY. Morphological variations in a tooth family through ontogeny in Pleurodeles waltl (Lissamphibia, Caudata) J Morphol. 2006;267:1048–1065. doi: 10.1002/jmor.10455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado S, Davit-Beal T, Allizard F, et al. Tooth development in a scincid lizard, Chalcides viridanus (Squamata), with particular attention to enamel formation. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;319:71–89. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-0950-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmund AG. Dentition. In: Gans C,BellairsA'A, Parsons TS., editors. Biology of the Reptilia. London: Academic Press; 1969. pp. 117–200. volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Evans SE, Prasad GVR, Manhas BK. Rhynchocephalians (Diapsida: Lepidosauria) from the Jurassic Kota Formation of India. Zool J Linn Soc. 2001;133:309–334. [Google Scholar]

- Handrigan GR, Richman JM. Autocrine and paracrine Shh signaling are necessary for tooth morphogenesis, but not tooth replacement in snakes and lizards (Squamata) Dev Biol. 2010;337:171–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handrigan GR, Richman JM. Unicuspid and bicuspid tooth crown formation in squamates. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol. 2011;316:598–608. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handrigan GR, Leung KJ, Richman JM. Identification of putative dental epithelial stem cells in a lizard with life-long tooth replacement. Development. 2010;137:3545–3549. doi: 10.1242/dev.052415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Bringas P, Jr, Slavkin HC, et al. Fate of HERS during tooth root development. Dev Biol. 2009;334:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huysseune A, Sire JY. Structure and development of first-generation teeth in the cichlid Hemichromis bimaculatus (Teleostei, Cichlidae) Tissue Cell. 1997;29:679–697. doi: 10.1016/s0040-8166(97)80044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvinen E, Valimaki K, Pummila M, et al. The taming of the shrew milk teeth. Evol Dev. 2008;10:477–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2008.00258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvinen E, Tummers M, Thesleff I. The role of the dental lamina in mammalian tooth replacement. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol. 2009;312B:281–291. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernvall J, Kettunen P, Karavanova I, et al. Evidence for the role of the enamel knot as a control center in mammalian tooth cusp formation: non-dividing cells express growth stimulating Fgf-4 gene. Int J Dev Biol. 1994;38:463–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keranen SV, Aberg T, Kettunen P, et al. Association of developmental regulatory genes with the development of different molar tooth shapes in two species of rodents. Dev Genes Evol. 1998;208:477–486. doi: 10.1007/s004270050206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama E, Wu C, Shimo T, et al. Development of stratum intermedium and its role as a Sonic hedgehog-signaling structure during odontogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2001;222:178–191. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratochvil C, Kubicka L, Landova E. Yolk hormone levels in the synchronously developing eggs of Paroedura picta, a gecko with genetic sex determination. Can J Zool. 2006;84:1683–1687. [Google Scholar]

- Leche W. Über die Zahnentwicklung bei Iguana tuberculata. Anat Anz. 1893;S:793–800. [Google Scholar]

- Lee JC, Clayton D, Einstein S, et al. The reproductive cycle of Anolis sagrei in Southern Florida. Copeia. 1989;4:930–937. [Google Scholar]

- Lemus D, Paz de la Vega Y, Fuenzalida M, et al. In vitro differentiation of tooth buds from embryos and adult lizards (L. gravenhorsti): an ultrastructural comparison. J Morphol. 1980;165:225–236. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1051650302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan X, Ito Y, Diekwisch TG. Evolution and development of Hertwig's epithelial root sheath. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:1167–1180. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell EE, Caldwell MW, Lamoureux DO, et al. Histology of tooth attachment tissues and plicidentine in Varanus (Reptilia: Squamata), and a discussion of the evolution of amniote tooth attachment. J Morphol. 2011;272:1170–1181. doi: 10.1002/jmor.10972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh J, Anderton X, Flores-de-Jacoby L, et al. Tooth attachment apparatus in young Caiman sclerops. Arch Oral Biol. 1968;13:735–743. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(68)90091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moustakas JE, Smith KK, Hlusko LJ. Evolution and development of the mammalian dentition: insights from the marsupial Monodelphis domestica. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:232–239. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagashima H, Kuraku S, Uchida K, et al. On the carapacial ridge in turtle embryos: its developmental origin, function and the chelonian body plan. Development. 2007;134:2219–2226. doi: 10.1242/dev.002618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura M, Bringas P, Jr, Slavkin HC. Inner enamel epithelia synthesize and secrete enamel proteins during mouse molar occlusal ‘enamel-free area’ development. J Craniofac Genet Dev Biol. 1991;11:96–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noro M, Uejima A, Abe G, et al. Normal developmental stages of the Madagascar ground gecko Paroedura pictus with special reference to limb morphogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:100–109. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa T. [A histological study of the gekko tooth (author's translation)] Shigaku. 1977;64:1377–1388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohazama A, Blackburn J, Porntaveetus T, et al. A role for suppressed incisor cuspal morphogenesis in the evolution of mammalian heterodont dentition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:92–97. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907236107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn JW. The ontogeny of tooth succession in Lacerta vivipara Jacquin (1787) Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1971;179:261–289. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1971.0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn JW. On the control of tooth replacement in reptiles and its relationship to growth. J Theor Biol. 1974;46:509–527. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(74)90012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn JW. Relationship between growth and the pattern of tooth initiation in alligator embryos. J Dent Res. 1998;77:1730–1738. doi: 10.1177/00220345980770090901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens PD. Ultrastructure of Hertwig's epithelial root sheath during early root development in premolar teeth in dogs. Arch Oral Biol. 1978;23:91–104. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(78)90145-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paynter KJ, Pudy G. A study of the structure, chemical nature, and development of cementum in the rat. Anat Rec. 1958;131:233–251. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091310207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyer B. Comparative Odontology. Chicago: University Chicago press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Prochazka J, Pantalacci S, Churava S, et al. Patterning by heritage in mouse molar row development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:15497–15502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002784107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reif W-E. Morphogenesis, pattern formation and function of the dentition of Heterodontus (Selachii) Zoomorphologie. 1976;83:1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Richman JM, Handrigan GR. Reptilian tooth development. Genesis. 2011;49:247–260. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar-Ciudad I, Jernvall J. A computational model of teeth and the developmental origins of morphological variation. Nature. 2010;464:583–586. doi: 10.1038/nature08838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger TJ, Losos JB, Gibson-Brown JJ. A developmental staging series for the lizard genus Anolis: a new system for the integration of evolution, development, and ecology. J Morphol. 2008;269:129–137. doi: 10.1002/jmor.10563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasagawa I, Ishiyama M. Fine structure and Ca-ATPase activity of the stratum intermedium cells during odontogenesis in gars, Lepisosteus, Actinopterygii. Connect Tissue Res. 2002;43:505–508. doi: 10.1080/03008200290001203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvig KA. Electron microscopy of Hertwig's epithelial sheath and of early dentin and cementum formation in the mouse incisor. Acta Odontol Scand. 1963;21:175–186. doi: 10.3109/00016356308993957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sire JY, Davit-Beal T, Delgado S, et al. First-generation teeth in nonmammalian lineages: evidence for a conserved ancestral character? Microsc Res Tech. 2002;59:408–434. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stembirek J, Buchtova M, Kral T, et al. Early morphogenesis of heterodont dentition in minipigs. Eur J Oral Sci. 2010;118:547–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2010.00772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumida SS, Murphy RW. Form and function of the tooth crown structure in gekkonid lizards (Reptilia, Squamata, Gekkonidae) Can J Zool. 1987;65:2886–2892. [Google Scholar]

- Ten Cate AR. The role of epithelium in the development, structure and function of the tissues of tooth support. Oral Dis. 1996;2:55–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.1996.tb00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas HF, Kollar EJ. Differentiation of odontoblasts in grafted recombinants of murine epithelial root sheath and dental mesenchyme. Arch Oral Biol. 1989;34:27–35. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(89)90043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal N, Hedges SB. The phylogeny of squamate reptiles (lizards, snakes, and amphisbaenians) inferred from nine nuclear protein-coding genes. C R Biol. 2005;328:1000–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonk FJ, Admiraal JF, Jackson K, et al. Evolutionary origin and development of snake fangs. Nature. 2008;454:630–633. doi: 10.1038/nature07178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westergaard B. Early dentition development in the lower jaws of Anguis fragilis and Lacertu agilis. Memo SOC Fauna Flora Fenn. 1988a;64:148–151. [Google Scholar]

- Westergaard B. The pattern of embryonic tooth initiation in reptiles. Teeth revised. Mem Mus Nat Hist Paris Ser C. 1988b;53:55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Westergaard B, Ferguson MW. Development of the dentition in Alligator mississipiensis. Early embryonic development in the lower jaw. J Zool (Lond) 1986;210:575–597. [Google Scholar]

- Westergaard B, Ferguson MW. Development of the dentition in Alligator mississippiensis: upper jaw dental and craniofacial development in embryos, hatchlings, and young juveniles, with a comparison to lower jaw development. Am J Anat. 1990;187:393–421. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001870407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiens JJ, Kuczynski CA, Townsend T, et al. Combining phylogenomics and fossils in higher-level squamate reptile phylogeny: molecular data change the placement of fossil taxa. Syst Biol. 2010;59:674–688. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka A, Yasui K, Sonomura T, et al. Development of deciduous and permanent dentitions in the upper jaw of the house shrew (Suncus murinus. Arch Oral Biol. 2010;55:279–287. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahradnicek O, Horacek I, Tucker AS. Viperous fangs: development and evolution of the venom canal. Mech Dev. 2008;125:786–796. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]