Abstract

Introduction

Rectal polypectomy causes thinning (or even perforation) of the rectal wall in addition to thermic injury at the polypectomy site.

Case report

We present a rare case of spontaneous rectal perforation after uncomplicated nerve sparing endoscopic extraperitoneal radical prostatectomy in a patient with a previous history of rectal polypectomy at the perforation site. The patient could be treated conservatively. There was complete healing of the fistula without any effect on functional results. This Conservative therapy for such rectal perforations is indicated if the patient's general condition remains stable without any signs of infection.

Conclusions

Polypectomy is an important risk factor for rectal perforation during nsEERPE. Adequate time interval should be given to allow healing and avoid adding further thermal wall damage which may obscure healing leading to complications like fistula. Conservative therapy for small missed rectal perforations constitutes an attractive, feasible and non invasive treatment entity. Following this principle we have not faced this complication in following similar cases.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, (nsEERPE), Rectum perforation

Introduction

Coloscopy is a routine examination for men over 50 years in Germany. From the surgical point of view it has two main risks. The first one is the bleeding after endoluminal polypectomy. The other one is the perforation of the gut which is a severe and possibly lethal complication with a reported incidence of 0.1% to 0.9% [1-4].

Most rectal injuries during nerve sparing endoscopic extraperitoneal radical prostatectomy (nsEERPE) occur while transecting rectourethralis muscle cutting further into rectal wall. Mostly they are identified intraoperatively and repaired in 2-layers [5-7].

We present a rare case of spontaneous rectal perforation after uncomplicated nsEERPE in a patient with a previous history of rectal polypectomy at the perforation site, which was successfully treated conservatively.

Case report

In November 2005, an otherwise healthy 71-year-old man with localised prostate cancer underwent nsEERPE in our hospital. He gave history of polypectomy 10 cm from anus 4 weeks before, otherwise no clinical or laboratory abnormalities. The operation was uneventful with 300 ml blood loss and without suspected injuries. The patient suffered rectal bleeding 24 hours postoperatively. Coloscopy revealed bleeding from intraluminal wall laceration over a haematoma in polypectomy site (Figure 1a) which was sealed with fibrin glue. CT revealed pelvic haematoma without detectable connections between rectum, bladder or abdomen (Figure 1b). The drain was removed at 3rd day. Follow up coloscopies at 4th and 6th day showed established perforation. The clinical picture remains stable without peritonitis. 10th day cystography revealed intact anastomosis and the catheter was removed. The patient is continent without micturation or defecation problems. Conservative treatment without antibiotics was done up 10th day. CT at 16th day showed established free connection between rectum and haematoma with some air without abdominal connections (Figure 2a, b). Later, there was complete resorption of haematoma and healing of fistula as shown by abdominal CT (Figure 2c) and coloscopy at 3rd month. Pathologic stage was pT3b, pN0, pM0, G3, R0. PSA is still undetectable.

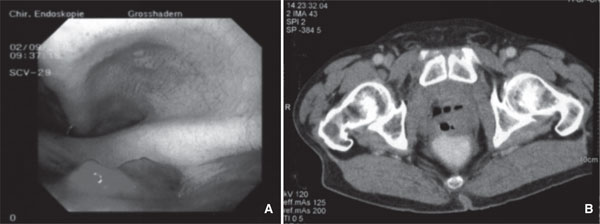

Figure 1.

(A) Rectoscopy view showing bleeding from wand haematoma without any fistula (2nd postoperative day). (B) CT examination showing pelvic haematoma without any signs of rectal perforation (3rd postoperative day).

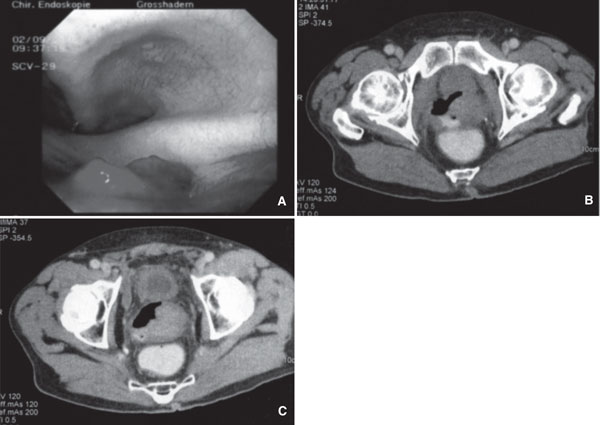

Figure 2.

(A. and B) coronal and sagittal abdominal CT sections showing free connection between rectum and prostate bed with haematoma, contrast material and some air (16th postoperative day). (C) CT examination after 3 months showing completely normal view.

Discussion

In this case rectal perforation could be either due to laceration because of previous polypectomy or missed iatrogenic perforation.

Owing to the intimate anatomical relation to prostate, it is our believe that this rectal wall thinning (or perforations) together with thermic injury at site of polypectomy should be given enough time to heal with adequate scare, otherwise it well predispose to laceration followed by perforation/necrosis in this site during or after operative manipulations. Postoperative rectal bleeding remains the cardinal sign for diagnosis. However care should be taken to exclude merely secondary haemorrhage due to clot dissolution in these cases which may manifest itself days to weeks after coloscopy (0.3-6.1%) [2,3].

Although practiced in the beginning of open retropubic prostatectomy, most laparoscopic groups, including ours, leave the urethra intact during most of the dissection. Instead, the plane between the seminal vesicles, prostate, and rectum is developed, progressing from the base of the prostate as close as possible to the apex. It is during this dissection that most iatrogenic rectal injuries occur [2]. Most of these injuries are visually identified intraoperatively and commonly repaired in a 2-layer suture with or without interposition of omentum/fat between the rectum and the vesicourethral anastomosis [5-7].

In case of missed perforations, signs and symptoms will be related to the size and site of the perforation, adequacy of bowel preparation, amount of peritoneal soilage, underlying bowel pathology (e.g. thin walled colon from colitis or ischemia may result in a larger perforation than a healthy colon) and finally, overall clinical condition of the patient [8]. Radiology often establishes the diagnosis however a localized perforation may demonstrate lack of pneumo peritoneum and necessitates other diagnostic procedures.

Management remains a controversial issue in that it can be effectively done by operative and nonoperative measures. Generally, nonsurgical management is indicated if the patient's general condition remains stable, the pneumoperitoneum does not increase in size, there are no signs of peritonitis and if the patient's condition improves in response to conservative treatment [9,10].

Surgery is most definitely indicated in the presence of a large perforation, in the setting of generalized peritonitis or ongoing sepsis, the presence of concomitant pathology, unremitting colitis or perforation proximal to an obstructing distal lesion. Finally, in the patient who deteriorates with conservative management [8].

However, the best treatment for rectal injury during nsEERPE remains prevention. Although the primary reason is certainly anatomical since the plane of dissection is close to the rectum, another reason could be weakness of the rectal wall e.g. following polypectomy. In our opinion the later case needs 2 months in order to heal adequately and withstand operative manipulations. Also to avoid adding further thermal wall damage to this site which may later obscure healing leading to more serious complications like fistula. According to this principle we have not faced this complication in following similar cases.

Nevertheless, the use of an intrarectal device/air should be emphasized in difficult cases due to surgeon inexperience, inflamed prostate, large volume gland, narrow and/or deep pelvis or previous rectal operations [5]. These simple manoeuvres help in identifying the site of perforation and/or lacerations, if exist.

Conclusion

Polypectomy is an important risk factor for rectal lacerations and/or perforations during nEERPE. About 2 months interval should be given to allow adequate healing before the operation and avoid adding further thermal wall damage which may obscure healing leading to complications like fistula. Conservative therapy for these small missed rectal perforations constitutes a feasible and non invasive treatment entity. However in the presence of a large perforation, generalized peritonitis, ongoing sepsis or if the patient condition deteriorates surgery is indicated. Intra-operative use of an intrarectal device/air should be emphasized in difficult cases.

Conflicts of interests

The authors disclose any commercial association that might pose a conflict in connection with the submitted article.

References

- Gedebou TM, Wong RA, Rappaport WD, Jaffe P, Kahsai D, Hunter GC. Clinical presentation and management of iatrogenic colon perforations. Am J Surg. 1996;172:454–457. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(96)00236-X. discussion 457-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanek P, Adámek S, Pafko P. Our Experiences with Surgical Treatment of Iatrogenic Colon Perforation. Zentralbl Chir. 2005;130:120–122. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-836338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra-Blanco A, Kaminaga N, Kojima T, Endo Y, Tajiri A, Fujita R. Colonoscopic polypectomy with cutting current: is it safe? Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:676–681. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.105203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson D, McQuaid K, Bond J. et al. Procedural success and complications of large-scale screening colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55(3):307–314. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.121883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillonneau B, Gupta R, El Fettouh H, Cathelineau X, Baumert H, Vallancien G. Laparoscopic management of rectal injury during laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2003;169:1694–1696. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000059860.00022.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz R, Borkowski T, Hoznek A, Salomon L, de la Taille A, Abbou CC. Operative management of rectal injuries during laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2003;62:310–313. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(03)00326-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolzenburg JU, Rabenalt R, Do M. et al. Endoscopic extraperitoneal radical prostatectomy: oncological and functional results after 700 procedures. J Urol. 2005;174:12715. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000173940.49015.4a. discussion 1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damore LJ, Rantis PC, Vernava AM, Longo WE. Colonoscopic perforations: Etiology, diagnosis, and management. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:1308–1314. doi: 10.1007/BF02055129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpio G, Albu E, Gumbs MA, Gerst PH. Management of colonic perforation after colonoscopy: Report of three cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:624–626. doi: 10.1007/BF02554186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao TH, Wang HM, Liou TY, Chen JB, Chen SS. Clinical treatment in colonoscopic perforation: a comparison of surgical and conservative management. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei) 1997;60:36–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]