Abstract

During 2004–2006, two hypomethylating agents (HMAs) were approved for the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) in the United States. We assessed the impact of HMAs on the cost of care and survival of MDS patients, by constructing a cohort of patients who were diagnosed during 2001–2007 (n=6,556, age ≥ 66.5 years) and comparable non-cancer controls. We assessed MDS patients’ and controls’ Medicare expenditures to derive MDS-related cost. We evaluated the two-year survival of patients as a group and by major subtypes. Taking into account the survival probabilities of MDS, the expected MDS-related 5-year cost was $63,223 (95% confidence interval: $59,868–66,432 in 2009 dollars), higher than the reported comparable cost for any of the 18 most prevalent cancers in the United States. Compared with MDS patients diagnosed in the earlier period (January 2001–June 2004) who received no HMAs, patients diagnosed later (July 2004–December 2007) who received HMAs had a significantly higher 24-month cost ($97,977 vs. $42,628 in 2009 dollars) and an improved 24-month survival (especially among patients with refractory anemia or refractory anemia with excess blasts). The magnitude of the cost of care underscores a need for comparative cost-effectiveness studies to reduce the clinical and economic burden of MDS.

Keywords: myelodysplastic syndromes, azacitidine, decitabine, cost, survival

Introduction

In the United States (US), 80% of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are ≥ 65 years at diagnosis.1 Most older patients are not eligible for allogeneic stem cell transplant, the only potentially curative therapy for MDS. Two hypomethylating agents (HMAs, azacitidine and decitabine) were approved for MDS treatment in the US in May 2004 and June 2006, respectively. Due to the lower toxicity than previous chemotherapy agents and fewer side effects, the HMAs have been gradually adopted in the treatment of elderly MDS patients.2 Although randomized clinical trials suggested that HMAs prolonged MDS survival and/or improved patients’ quality of life,3–6 patients included in the trials were usually younger than patients observed in the general population. The effectiveness of HMAs in the older population in actual clinical practice is not established.

HMAs are expensive - the annual costs for azacitidine or decitabine alone are approximately $55,332 and $74,160, respectively.7 While these costs are substantial, HMAs may reduce the need for supportive care such as blood transfusion.4,8–9 Many MDS patients become transfusion dependent during the course of the disease, and the cost of blood transfusions may exceed $31,000 annually for transfusion-dependent patients.10 It is unclear how the introduction of HMAs affected the overall economic burden posed by MDS. We therefore assessed the impact of HMAs on the cost of care and survival of MDS patients in the Medicare population, by assembling a large, population-based cohort of patients diagnosed during 2001–2007 and following the care they received through the end of 2009.

Methods

Study Design

We carried out a longitudinal analysis of health-care utilization and cost following MDS diagnosis by using the most recently updated Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare database, which is compiled by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and included MDS diagnoses during 2001–2007 and Medicare claims through 2009. The SEER program consists of population-based tumor registries that represent 26% of the US population. Cancer patients reported to SEER were matched against Medicare’s master enrollment file, and the claims for Medicare-eligible persons with fee-for-service coverage were retrieved. Among individuals who were included in SEER files and 65 years or older, 93% were found in the Medicare enrollment file.11 The NCI also created a file that identifies a 5% random sample of Medicare beneficiaries residing in SEER areas, with an indicator of whether they have a cancer diagnosis listed in SEER.

In this study, we defined “costs” as the actual amounts paid by Medicare, regardless of the amounts charged by health care providers and facilities. In health services research, Medicare payments are considered a good proxy for true economic cost.12 We selected MDS cases and non-cancer controls, tallied the Medicare costs incurred by cases and controls, and took the difference in costs between cases and controls as MDS-related cost. In addition, we counted MDS-related cost within 2 years of diagnosis, regardless of the phases of care. The case-control, indirect approach we used is preferable for the assessment of disease-specific cost and is commonly used in health services research.13 The essence of this approach is to estimate the overall disease-specific cost incurred by an individual, as opposed to counting costs attributable to specific treatments (e.g. HMAs and transfusions).

The evaluation of MDS survival was conducted among cases only. We assessed the impact of HMAs on 24-month survival by accounting for a variety of patient characteristics that had been previously linked to MDS survival and/or the use of HMAs in the SEER-Medicare population.2,14–15

We chose 24 months after diagnosis as the primary time window for the assessment of cost and survival because the median survival in elderly MDS patients was about 2 years in this analysis, and 2-year survival was the primary endpoint in several clinical trials involving HMAs.3,16–18 In addition, we had at least 2 years of Medicare claims for all patients included in the study population.

Selection of Study Sample

MDS patients who met the following criteria were identified (n = 11,494): 1) first primary MDS [International Classification of Disease for Oncology, 3rd edition (ICD-O-3) codes:9980, 9982, 9983, 9985, 9986, 9987 and 9989]19 diagnosed between 1/1/2001 and 12/31/2007; 2) aged ≥ 66.5 years at diagnosis; 3) were not identified through death certificates or autopsy only. Health maintenance organizations are not required to submit claims for services received by Medicare enrollees. To ensure completeness of data, we excluded patients who were not enrolled in Medicare Parts A and B continuously, or were enrolled in a health maintenance organization any time from 18 months before MDS diagnosis through the date of death (if patient died) or the end of 2009, whichever was earlier (n = 4,342). To ensure that MDS cases are incident, we excluded patients who had any Medicare claims with the International Classification of Disease, 9th Edition (ICD-9) code 238.7 during the 6–18 months before the SEER-recorded date of MDS diagnosis (n = 588). The ICD-9 code 238.7 covers MDS and other hematological conditions such as myeloproliferative neoplasms. We chose the cutoff of 6 months because the diagnosis of MDS can take several months. Due to the need to obtain Medicare claims for 18 months before the date of MDS diagnosis for exclusion purpose, we limited the MDS patients to those diagnosed at the age of ≥ 66.5 years.

Non-cancer controls were selected from the 5% random sample of Medicare beneficiaries and had to satisfy the same inclusion criteria for age and Medicare coverage as MDS patients. Additionally, controls had no cancer diagnoses based on SEER records and Medicare claims. With a 1:4 case:control ratio, controls were frequency-matched to MDS patients by factors known or suspected to be associated with cost, including age group (66.5–74, 75–79, 80–84, or 85 years), sex, pre-diagnosis cost (in quartiles), number of comorbidities (0, 1, and 2+), and SEER registry. The pre-diagnosis cost was calculated by aggregating Medicare payments during the 6–18 months before the reference date (date of MDS diagnosis for cases or a randomly assigned pseudo-diagnosis date for controls) and categorized into quartiles based on the distribution among MDS patients. Matched controls could not be found for 8 MDS patients, who were excluded from the study.

A total of 6,556 MDS patients and 26,109 controls were included in the study.

Study Variables

We used a phase-of-care approach to estimate the cost of medical care.20 The period of time from MDS diagnosis through death was divided into three phases: initial, continuing, and end-of-life phases. The initial phase was defined as the first 12 months after MDS diagnosis, the end-of-life phase was defined as the final 12 months of life, and the continuing phase was defined as all months between the initial and end-of-life phases. Not all patients had three phases. For patients surviving less than 12 months, all observed months were allocated to the end-of-life phase. For patients surviving less than 24 months, the final 12 months were allocated to the end-of-life phase, with the remaining months allocated to the initial phase. Patients surviving beyond December 2009 only had initial and continuing phases. Months of observation were also allocated to different phases for controls.20 For all subjects, Medicare inpatient, outpatient, and carriers claims were searched to retrieve Medicare payments. As 2009 was the most recent year for which we had records of Medicare payments, all costs were adjusted to 2009 US dollars accounting for temporal and geographic variations using the Prospective Payment System, Medicare Economic Index, Geographic Adjustment Factor, and Geographic Practice Cost Index as is common in studies utilizing the SEER-Medicare database.13,21

Survival of MDS patients was defined as the duration between the date of diagnosis and the date of death due to any cause (if a MDS patient has died), or December 31, 2009, whichever was earlier. Other variables of interest included MDS subtypes, age at diagnosis, sex, race, comorbidities, median household income at the zip code level, and treatment with HMAs. The subtypes were based on ICD-O-3 codes and included (1) 9980: refractory anemia (RA); (2) 9982: RA with ringed sideroblasts (RARS); (3) 9983: RA with excess blasts (RAEB); and (4) 9985: refractory cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia (RCMD). Inpatient, outpatient and carrier files were searched to ascertain Medicare claims during the 6–18 months before the reference date for comorbidities that were suggested by Elixhauser et al.22 and were significantly associated with mortality among non-cancer controls. Median household income was categorized into three levels, with the first tertile representing the lowest income. Validation studies suggest that Medicare claims can accurately identify the receipt of chemotherapy and specific agents that are not orally administered.23 Since azacitidine is administered by intravenous or subcutaneous injection, and decitabine is administered intravenously, the use of these drugs should be well captured by SEER-Medicare. We have developed the protocol to identify the use of the two HMAs with specific Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes.2 Treatment with either HMA agent was considered the same.

Statistical Analysis

Within each phase, the control group was used to estimate the background cost unrelated to MDS. The differences in average monthly costs between MDS patients and controls were considered MDS-related costs. Confidence intervals (CIs) for the monthly costs were derived by using a nonparametric bootstrap approach.

To estimate 1-year and 5-year MDS-related costs, we obtained from SEER24 the monthly survival probabilities of incident MDS patients 66 years or older who were diagnosed during 2001–2007 and had no history of previous cancer. The survival probabilities were specific to patients with various characteristics (e.g. white, male). We summed phase-specific monthly costs across the number of months patients contributed to each phase. As patients survived different lengths of time, we weighted cost estimates based on the percentage of patients surviving each month. We then used the lower and upper bounds of the 95% CIs of monthly costs to estimate plausible ranges for expected 1-year and 5-year costs. The expected 1-year cost is based on the survival experience of a large number of MDS patients during the first year after diagnosis, and it represents the average cost an elderly MDS patient would incur in the first year after diagnosis. The expected 5-year cost has a similar interpretation. Additionally, we tallied MDS-related cost within the 24 months after diagnosis, as the time frame for the survival analysis was 24 months.

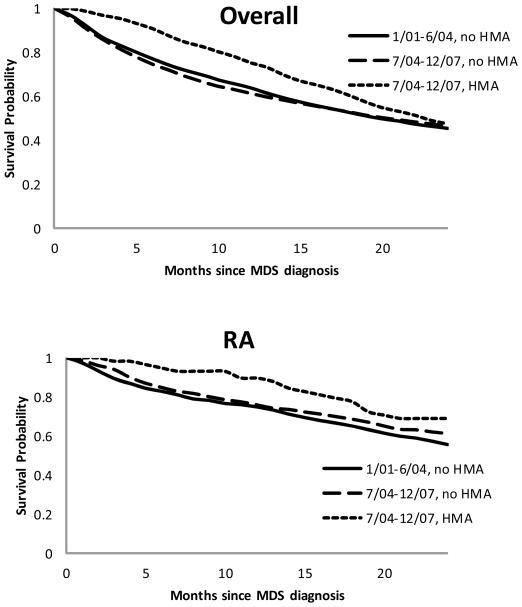

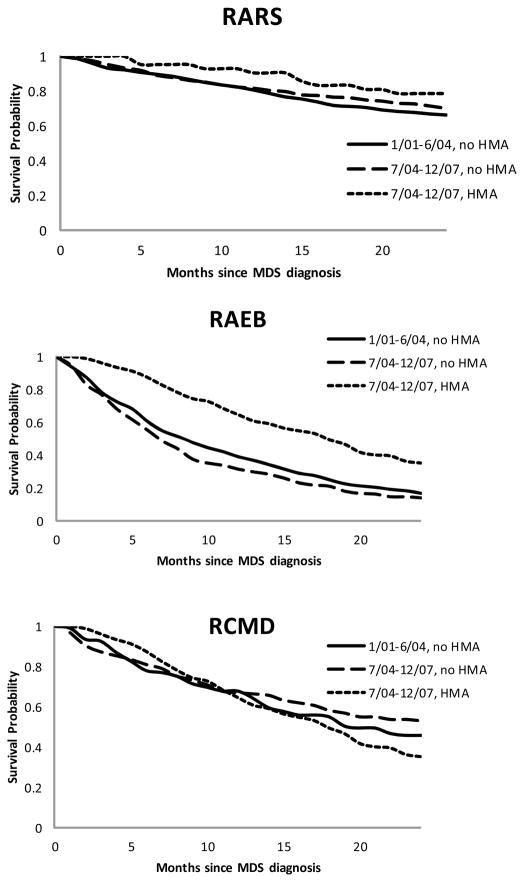

We assessed MDS survival across strata of era of diagnosis (earlier, January 2001–June 2004 vs. later, July 2004–December 2007) and history of HMAs treatment (yes vs. no). Since few MDS patients diagnosed during the earlier period received HMAs (n = 158, 2.4% of all patients), this particular analysis focused on three subgroups: earlier period without HMAs (n = 2,895), later period without HMAs (n = 2,847), and later period with HMAs (n = 669). Moreover, we evaluated MDS survival in major subtypes. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were plotted over a 24-month period, and log-rank tests were used to compare the curves.

To account for the baseline propensity to receive HMA treatment, we used a multivariate logistic regression model to develop a propensity score for each patient 25, with the outcome being HMA treatment and the independent variables being a list of patient characteristics that had been linked to the use of HMAs or MDS survival in the SEER-Medicare population.2,14–15 After a step-wise selection, age at diagnosis, sex, comorbidities, pre-diagnosis cost, subtype and year of diagnosis remained in the final model. Patients were then divided into propensity score quintiles, and propensity quintile was included in a multivariate Cox proportional hazard model as an independent variable in lieu of all patient factors except treatment.26 We verified the proportional hazard assumption for the Cox model.

All analyses were conducted using SAS (version 9.2, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

MDS patients and controls were comparable regarding the matching variables (Table 1). Accounting for the survival probabilities of MDS patients, the expected 1-year and 5-year MDS-related cost were $26,125 (range: $24,924–27,266) and $63,223 (range: $59,868–66,432), respectively (Table 2). The 5-year cost appeared to be higher for patients who were younger, male or resided in the Northeast or Midwest, but it did not vary substantially by race. Of the major subtypes, RAEB had the highest 1-year cost, but the 5-year cost for RAEB was comparable to that for RARS and RCMD due to the short survival of RAEB patients (Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Population

| MDS Patients

|

Controls

|

P for Chi-square | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Total | 6556 | 26109 | |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | |||

| 66–74 | 1730 (26.4) | 6917 (26.5) | 1.00 |

| 75–79 | 1646 (25.1) | 6560 (25.1) | |

| 80–84 | 1690 (25.8) | 6719 (25.7) | |

| ≥ 85 | 1490 (22.7) | 5913 (22.7) | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 3069 (46.8) | 12264 (47.0) | 0.82 |

| Male | 3487 (53.2) | 13845 (53.0) | |

| Pre-diagnosis cost (in 2009 dollars) | |||

| <1151 | 1645 (25.1) | 6580 (25.2) | 0.99 |

| 1151– <3387.15 | 1666 (25.4) | 6654 (25.5) | |

| 3387.15– <11224.61 | 1654 (25.2) | 6581 (25.2) | |

| ≥11224.61 | 1591 (24.3) | 6294 (24.1) | |

| Comorbidity | |||

| 0 | 2439 (37.2) | 9684 (37.1) | 0.98 |

| 1 | 1607 (24.5) | 6391 (24.5) | |

| ≥ 2 | 2510 (38.3) | 10034 (38.4) | |

| SEER Registry | |||

| San Francisco | 153 (2.3) | 607 (2.3) | 1.00 |

| Connecticut | 351 (5.4) | 1400 (5.4) | |

| Detroit | 602 (9.2) | 2379 (9.1) | |

| Hawaii | 64 (1.0) | 249 (1.0) | |

| Iowa | 535 (8.2) | 2137 (8.2) | |

| New Mexico | 119 (1.8) | 470 (1.8) | |

| Seattle | 576 (8.8) | 2293 (8.8) | |

| Utah | 172 (2.6) | 681 (2.6) | |

| Atlanta | 140 (2.1) | 550 (2.1) | |

| San Jose | 166 (2.5) | 660 (2.5) | |

| Los Angeles | 432 (6.6) | 1722 (6.6) | |

| Rural Georgia | 13 (0.2) | 43 (0.2) | |

| Greater California | 1072 (16.4) | 4286 (16.4) | |

| Kentucky | 577 (8.8) | 2300 (8.8) | |

| Louisiana | 476 (7.3) | 1900 (7.3) | |

| New Jersey | 1108 (16.9) | 4432 (17.0) | |

Table 2.

Expected Myelodysplastic Syndromes-Related Cost (in 2009 Dollars) by Patient Characteristics, Based on the Phase of Care Approach13

| 1-Year

|

5-Year

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % alive | MDS-related Cost (range) | % alive | MDS-related Cost (range) | |

| Overall | 66.9 | 26125 (24924–27266) | 24.2 | 63223 (59868–66432) |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | ||||

| 66–74 | 73.7 | 28632 (25863–31506) | 33.7 | 73828 (65700–82084) |

| 75–79 | 70.6 | 26815 (24329–29225) | 27.8 | 66980 (60057–73530) |

| 80–84 | 65.0 | 23090 (21069–25256) | 21.1 | 54207 (48762–60084) |

| ≥ 85 | 56.2 | 20853 (18856–22672) | 11.1 | 44874 (40171–49285) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 66.6 | 26208 (24945–27457) | 23.3 | 63339 (59963–66772) |

| Non-White | 68.7 | 25872 (22269–29423) | 30.4 | 62730 (51948–73568) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 69.0 | 24608 (23095–26161) | 26.5 | 60449 (55980–65023) |

| Male | 65.1 | 27462 (25634–29176) | 22.3 | 65635 (61002–70196) |

| SEER region | ||||

| Northeast | 69.3 | 26036 (23556–28601) | 27.8 | 66581 (59417–73975) |

| Midwest | 67.3 | 27156 (24453–29839) | 23.6 | 66183 (58852–73674) |

| South | 67.2 | 27148 (24181–30016) | 22.6 | 63771 (56278–71304) |

| West | 65.9 | 25376 (23546–27220) | 23.6 | 60555 (55529–65593) |

| Major subtypes* (ICD-O-3) | ||||

| RA (9980) | 76.8 | 20917 (18416–23354) | 35.3 | 56186 (47941–64114) |

| RARS (9982) | 83.2 | 22041 (19027–25093) | 40.5 | 71520 (61430–82488) |

| RAEB (9983) | 45.1 | 39673 (35630–43891) | 5.7 | 70735 (62798–79173) |

| RCMD (9985) | 70.6 | 30382 (24920–35925) | 22.5 | 74162 (59259–90324) |

RA: refractory anemia; RARS: RA with ringed sideroblasts; RAEB: RA with excess blasts; RCMD: refractory cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia.

When we assessed MDS-related cost within 24 months of diagnosis, patients who were younger, male, had RAEB, had none or one comorbidity, were diagnosed in the later era, or had been treated with HMAs incurred significantly higher cost than patients without these characteristics (Table 3). The group of MDS patients who were diagnosed during the later era and received HMAs had a 24-month MDS-related cost of $97,977 (95% CI: $92,551 – 103,859). The same group also had better survival than the other groups during the 24 months following diagnosis (Figure 1, p=0.013). A statistically significant association was observed between HMAs and survival for patients with RA (p from log-rank test = 0.046) or RAEB (p < .0001), but not for RARS (p = 0.191) or RCMD (p = 0.562) (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Observed Myelodysplastic Syndromes-Related Cost (in 2009 Dollars) within 24 Months of Diagnosis, by Patient Characteristics

| 24-Month Cost ($) | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | 46661 | 45111 – 48182 |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | ||

| 66–74 | 59523 | 56111 – 63096 |

| 75–79 | 50534 | 47610 – 53833 |

| 80–84 | 42204 | 39582 – 45036 |

| ≥ 85 | 32489 | 30000 – 34747 |

| Race | ||

| White | 46542 | 44900 – 48093 |

| Non-White | 47632 | 43077 – 51918 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 42928 | 40832 – 44976 |

| Male | 49948 | 47697 – 52242 |

| SEER Region | ||

| Northeast | 47607 | 44399 – 50935 |

| Midwest | 48748 | 45337 – 51987 |

| South | 47629 | 44008 – 51190 |

| West | 44876 | 42609 – 47205 |

| Major subtypes* (ICD-O-3) | ||

| RA (9980) | 39406 | 35997 – 42864 |

| RARS (9982) | 43237 | 38708 – 47812 |

| RAEB (9983) | 62475 | 57929 – 67228 |

| RCMD (9985) | 58617 | 51585 – 66280 |

| Comorbidity | ||

| 0 | 50711 | 48218 – 53244 |

| 1 | 49315 | 46614 – 52293 |

| ≥ 2 | 41090 | 38568 – 43765 |

| Pre-diagnosis cost (in 2009 dollars) | ||

| <1151 | 47426 | 44612 – 50309 |

| 1151– <3387.15 | 48801 | 45821 – 51890 |

| 3387.15– <11224.61 | 48677 | 45824 – 51822 |

| ≥ 11224.61 | 41391 | 38241 – 44752 |

| Era of diagnosis | ||

| Earlier (1/2001 – 6/2004) | 43888 | 41833 – 45923 |

| Later (7/2004 – 12/2007) | 49065 | 46939 – 51222 |

| HMA use | ||

| No | 40111 | 38619 – 41723 |

| Yes | 92102 | 87361 – 97350 |

| Combined era of diagnosis and HMA use | ||

| 1/2001–6/2004, no HMA | 42628 | 40405 – 44802 |

| 1/2001–6/2004, HMA | 67075 | 56192 – 78252 |

| 7/2004–12/2007, no HMA | 37552 | 35457 – 39532 |

| 7/2004–12/2007, HMA | 97977 | 92551 – 103859 |

RA: refractory anemia; RARS: RA with ringed sideroblasts; RAEB: RA with excess blasts; RCMD: refractory cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier Survival Probabilities of MDS Overall and by Major Subtypes

MDS: myelodysplastic syndromes

Major subtypes: RA: refractory anemia; RARS: RA with ringed sideroblasts; RAEB: RA with excess blasts; RCMD: refractory cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia.

HMA: hypomethylating agents

A multivariate Cox regression analysis accounting for the propensity to receive HMAs suggests that patients diagnosed in the later period and treated with HMAs had a significantly lower risk of death [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.80, 95% CI:0.70–0.93] during the 24 months post diagnosis, compared with patients diagnosed in the earlier period and not treated with HMAs. Patients diagnosed in the later period but were not treated with HMAs had a similar 24-month mortality to those diagnosed earlier and not treatment with HMAs (HR = 1.00, 95% CI: 0.91–1.09).

Discussion

This study provided a population-based estimate of the direct medical cost for treating elderly MDS patients in the US before and after the introduction of HMAs. We chose June 2004 as the cut-off point for our categorization of era of diagnosis (earlier: January 2001 – June 2004; later: July 2004 – December 2007), because it coincided with the approval of azacitidine (May 2004) and was the midpoint of the 7-year period during which all MDS cases were diagnosed. This study is the first to assess the impact of HMAs on MDS survival in a large observational study and to report an association between HMAs and an improved survival in RA patients. The use of HMAs is associated with both a significantly higher 24-month cost and an improved 24-month survival.

The cost of care for MDS was substantial. The expected 5-year MDS-related cost per patient was more than $63,000 in 2009 dollars. This estimate is much higher than the recently reported 5-year net costs for the18 most prevalent cancers in the US, which ranged from less than $10,000 (in 2004 dollars) for melanoma to more than $40,000 (in 2004 dollars) for lymphoma, esophageal, gastric and ovarian cancer.13 If we inflate these reported costs in 2004 dollars to 2009 dollars using the Consumer Price Index, the highest 5-year net cost would still be lower than $60,000 for 17 of the 18 cancers. Only ovarian cancer patients had a 5-year net cost similar to that of MDS. Two recent studies indicated that the incidence of MDS could be much higher than previously reported27–28, with one study suggesting that the annual incidence among Medicare beneficiaries was more than 45,00027. This, coupled with the high cost per patient, would underscore a heavy economic burden for the management of MDS.

HMA users had much higher cost then non-users. The cost for a standard cycle of azacitidine (75 mg/m2 daily for 7 days) or decitabine (20 mg/m2 daily for 5 days) are $4,611 and $6,180, respectively.7 Six cycles of azacitidine or four cycles of decitabine are recommended to be administered before discontinuation, in the absence of intolerable toxicity or peripheral blood evidence of disease progression.29 Following such a schedule, even if a patient does not respond to HMAs, the cost for azacitidine or decitabine alone would be $27,666 and $24,720, respectively. However, the cost discrepancy between HMAs users and non-users may not be entirely attributable to the cost of HMAs. According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Networks guideline30, HMAs are the primary treatment for high risk MDS patients who have no available donor for hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and a therapeutic option for low-risk patients who do not respond to other therapies, as well as for patients with serum erythropoietin levels >500 mU/mL. Candidates for HMAs were likely to receive other types of treatment before, after, or concurrently with the administration of HMAs. In addition, HMAs appeared to prolong overall survival (Figure 1), which may have subsequently increased the total cost due to longer duration of medical care.

In this study, MDS patients diagnosed in the later period (July 2004 – December 2007) had significantly higher 24-month MDS-related cost than patients diagnosed earlier, but the absolute difference in dollar amount ($49,065 vs. $43,888) was not substantial. This is probably due to the relatively small percentage of patients who received HMAs (19% for patients diagnosed in the later period), which may increase in the future.

Recently, Craig et al. also estimated the cost of care for MDS in the US, but the study only included patients diagnosed during 2001–2005, did not evaluate the use of HMAs, and focused on cost incurred in the 6 months after diagnosis.31 Our study focused on the impact of HMAs on the cost of care and survival of MDS, which is a timely topic given the relatively recent approval of the agents for MDS treatment. The construction of a large, population-based cohort and the use of established methods in health services research for cost estimation represent strength of the study. We used two different approaches to estimate MDS-related cost. Using the phase-specific approach and incorporating the survival probabilities of MDS patients allowed us to generate an expected 5-year cost and put it in the context of comparable costs for other types of cancer. Tallying the observed cost within 24 months of diagnosis allowed us to evaluate cost in the same time frame for survival.

The study also has some limitations. First, we only included Medicare-eligible patients, which affects the generalizability of the results. However, MDS is predominantly a disease of the elderly.1 Second, approximately half of MDS patients reported by SEER were labeled as “MDS, not otherwise classified”. Although we observed a similar association between HMA use and survival in this group of patients, these patients might be different from the rest of the study population. Third, we only captured costs for inpatient and outpatient services covered by Medicare Parts A and B. Patients’ out-of-pocket cost, such as the cost for orally administered drugs not covered by Parts A and B and the cost of travel or lost income, would not have been captured, leading to an underestimate of cost. Forth, given the relatively short time since the approval of HMAs (especially the approval of decitabine) for MDS treatment and the poor prognosis of MDS in the elderly population, we focused on 24-month survival in this study and did not make a distinction between azacitidine and decitabine. A longer follow-up for survival would be more informative. Finally, the present study is observational by design, and one complexity is that those treated with HMAs may have had different survival probabilities a priori. We have utilized the propensity score approach to account for the baseline propensity for a patient to receive HMA treatment. The largest number of MDS patients included in a treatment group in any of the HMA trials that we identified was 172.3 A recent survey suggests that only 1% of newly diagnosed MDS patients in the US are enrolled in clinical trials,32 and the percentage of elderly MDS patients enrolled in trials is likely even lower. Effectiveness data generated by a large observational study can be complementary to efficacy data from randomized trials.

In conclusion, the cost of care for elderly MDS patients in the US was substantial. The use of HMAs was associated with a significantly higher 24-month cost and an improved 24-month survival (especially among patients with RA and RAEB). Given the magnitude of the economic burden imposed by MDS, further work is needed to assess the comparative cost-effectiveness of HMAs in different MDS subtypes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by two grants from the National Cancer Institute (R21 CA131927 and K07 CA119108) and a pilot award from the P30 Cancer Center Support Grant at the Yale Comprehensive Cancer Center. This study used the linked SEER-Medicare database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Program, National Cancer Institute; the Office of Research, Development and Information, Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services; Information Management Services, Inc.; and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions: RW, CPG, and XM designed the study and wrote the manuscript, RW and XM conducted statistical analyses with advice from KF and XX, KF, JL, XX, AR, NG, JZ, and GY helped to interpret the results and contributed to the writing. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest: None of the authors have a conflict of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ma X, Does M, Raza A, Mayne ST. Myelodysplastic syndromes: incidence and survival in the United States. Cancer. 2007;109(8):1536–1542. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang R, Gross CP, Maggiore RJ, et al. Pattern of hypomethylating agents use among elderly patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Leuk Res. 2011;35(7):904–908. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fenaux P, Mufti GJ, Hellstrom-Lindberg E, et al. Efficacy of azacitidine compared with that of conventional care regimens in the treatment of higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes: a randomised, open-label, phase III study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(3):223–232. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70003-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kantarjian H, Issa JP, Rosenfeld CS, et al. Decitabine improves patient outcomes in myelodysplastic syndromes: results of a phase III randomized study. Cancer. 2006;106(8):1794–1803. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lubbert M, Suciu S, Baila L, et al. Low-dose decitabine versus best supportive care in elderly patients with intermediate- or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) ineligible for intensive chemotherapy: final results of the randomized phase III study of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Leukemia Group and the German MDS Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(15):1987–1996. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.9245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silverman LR, Demakos EP, Peterson BL, et al. Randomized controlled trial of azacitidine in patients with the myelodysplastic syndrome: a study of the cancer and leukemia group B. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(10):2429–2440. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.04.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenberg PL, Cosler LE, Ferro SA, Lyman GH. The costs of drugs used to treat myelodysplastic syndromes following National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2008;6(9):942–953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silverman LR, McKenzie DR, Peterson BL, et al. Further analysis of trials with azacitidine in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome: studies 8421, 8921, and 9221 by the Cancer and Leukemia Group B. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(24):3895–3903. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.4346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steensma DP, Baer MR, Slack JL, et al. Multicenter study of decitabine administered daily for 5 days every 4 weeks to adults with myelodysplastic syndromes: the alternative dosing for outpatient treatment (ADOPT) trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(23):3842–3848. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.6550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frytak JR, Henk HJ, De Castro CM, Halpern R, Nelson M. Estimation of economic costs associated with transfusion dependence in adults with MDS. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25(8):1941–1951. doi: 10.1185/03007990903076699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, Bach PB, Riley GF. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care. 2002;40(8 Suppl):IV-3–18. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020942.47004.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown ML, Riley GF, Schussler N, Etzioni R. Estimating health care costs related to cancer treatment from SEER-Medicare data. Med Care. 2002;40(8 Suppl):IV-104–117. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208001-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yabroff KR, Lamont EB, Mariotto A, et al. Cost of care for elderly cancer patients in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(9):630–641. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang R, Gross CP, Halene S, Ma X. Neighborhood socioeconomic status influences the survival of elderly patients with myelodysplastic syndromes in the United States. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20(8):1369–1376. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9362-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang R, Gross CP, Halene S, Ma X. Comorbidities and survival in a large cohort of patients with newly diagnosed myelodysplastic syndromes. Leuk Res. 2009;33(12):1594–1598. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fenaux P, Gattermann N, Seymour JF, et al. Prolonged survival with improved tolerability in higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes: azacitidine compared with low dose ara-C. Br J Haematol. 2010;149(2):244–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kantarjian HM, O’Brien S, Huang X, et al. Survival advantage with decitabine versus intensive chemotherapy in patients with higher risk myelodysplastic syndrome: comparison with historical experience. Cancer. 2007;109(6):1133–1137. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seymour JF, Fenaux P, Silverman LR, et al. Effects of azacitidine compared with conventional care regimens in elderly (>/= 75 years) patients with higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2010;76(3):218–227. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fritz A, editor. International classification of diseases for oncology. 3. World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown ML, Riley GF, Potosky AL, Etzioni RD. Obtaining long-term disease specific costs of care: application to Medicare enrollees diagnosed with colorectal cancer. Med Care. 1999;37(12):1249–1259. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199912000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warren JL, Brown ML, Fay MP, Schussler N, Potosky AL, Riley GF. Costs of treatment for elderly women with early-stage breast cancer in fee-for-service settings. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(1):307–316. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lund JL, Sturmer T, Harlan LC, et al. Identifying Specific Chemotherapeutic Agents in Medicare Data: A Validation Study. Med Care. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31823ab60f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Surveillance Research Program. SEER*Stat software (seer.cancer.gov/seerstat) National Cancer Institute; [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rubin DB. Estimating causal effects from large data sets using propensity scores. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(8 Pt 2):757–763. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-8_part_2-199710151-00064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griffiths R, Mikhael J, Gleeson M, Danese M, Dreyling M. Addition of rituximab to chemotherapy alone as first-line therapy improves overall survival in elderly patients with mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118(18):4808–4816. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-348367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldberg SL, Chen E, Corral M, et al. Incidence and clinical complications of myelodysplastic syndromes among United States Medicare beneficiaries. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(17):2847–2852. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cogle CR, Craig BM, Rollison DE, List AF. Incidence of the myelodysplastic syndromes using a novel claims-based algorithm: high number of uncaptured cases by cancer registries. Blood. 2011;117(26):7121–7125. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-337964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blum W. How much? How frequent? How long? A clinical guide to new therapies in myelodysplastic syndromes. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2010;2010:314–321. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2010.1.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greenberg PL, Attar E, Bennett JM, et al. Myelodysplastic syndromes. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2011;9(1):30–56. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2011.0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Craig BM, Rollison DE, List AF, Cogle CR. Diagnostic testing, treatment, cost of care, and survival among registered and non-registered patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Leuk Res. 2011;35(11):1453–1456. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2011.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sekeres MA, Schoonen WM, Kantarjian H, et al. Characteristics of US patients with myelodysplastic syndromes: results of six cross-sectional physician surveys. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(21):1542–1551. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]