Abstract

Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection continues to cause substantial human suffering. New chemotherapeutic strategies, which require insight into the pathways essential for M. tuberculosis pathogenesis, are imperative. We previously reported that depletion of the CarD protein in mycobacteria compromises viability, resistance to oxidative stress and fluoroquinolones, and pathogenesis. CarD associates with the RNA polymerase (RNAP), but it has been unknown which of the diverse functions of CarD are mediated through the RNAP; this question must be answered to understand the CarD mechanism of action. Herein, we describe the interaction between the M. tuberculosis CarD and the RNAP β subunit and identify point mutations that weaken this interaction. The characterization of mycobacterial strains with attenuated CarD/RNAP β interactions demonstrates that the CarD/RNAP β association is required for viability and resistance to oxidative stress but not for fluoroquinolone resistance. Weakening the CarD/RNAP β interaction also increases the sensitivity of mycobacteria to rifampin and streptomycin. Surprisingly, depletion of the CarD protein did not affect sensitivity to rifampin. These findings define the CarD/RNAP interaction as a new target for chemotherapeutic intervention that could also improve the efficacy of rifampin treatment of tuberculosis. In addition, our data demonstrate that weakening the CarD/RNAP β interaction does not completely phenocopy the depletion of CarD and support the existence of functions for CarD independent of direct RNAP binding.

INTRODUCTION

At least 30% of the world's population is infected with latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which in some individuals will reactivate and cause 1.4 million deaths per year (26). An initial infection with M. tuberculosis occurs when droplet nuclei are inhaled into the pulmonary alveoli, where they are phagocytosed by cells of the innate immune system (11). Macrophages, lymphocytes, and fibroblasts aggregate around the infected cells to form a granuloma. Within the granuloma, the infected macrophages are activated to destroy the bacteria with which they are infected (12). The infected cells restrain mycobacteria from proliferating by imposing an arsenal of oxidative stress, hypoxia, acid stress, genotoxic stress, cell surface stress, and starvation (reviewed in reference 21). Despite this onslaught of attacks, M. tuberculosis is able to persist for the lifetime of the host, indicating that this pathogen has substantial molecular mechanisms for resisting host defenses.

M. tuberculosis resists elimination not only by the host's immunity but also by antimicrobial agents that are highly active against M. tuberculosis in vitro, but only slowly sterilize M. tuberculosis infection. Although active infection with drug-susceptible M. tuberculosis can be treated with multidrug antibiotic therapy, the core of which consists of isoniazid, rifampin, and pyrazinamide, the shortest antibiotic regimens that will achieve a reliable clinical cure of active M. tuberculosis infection are 6 months in duration. Significant investment in programs, like the Stop TB Strategy program (25), for reducing tuberculosis (TB) incidence and mortality have made some progress in decreasing the per capita TB rates. Unfortunately, the prevalence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains (resistant to the first-line therapies rifampin and isoniazid), which constituted 4.9% of TB cases in 2007, has caused growing recognition that the achievement of program goals may not be possible with currently available tools. The inadequacies of present tuberculosis therapies demand the discovery of new agents to treat M. tuberculosis infection, which requires insight into the pathways involved in M. tuberculosis pathogenesis.

During earlier investigations aimed at better understanding mycobacterial stress responses, we identified CarD as a highly expressed bacterial protein that is also transcriptionally induced by multiple types of stress (22). Efforts to delete the carD gene in M. tuberculosis and Mycobacterium smegmatis were unsuccessful, suggesting that CarD may be essential for viability, a suspicion that was confirmed by the construction of depletion strains (22). Transient depletion of CarD revealed that cells lacking CarD are sensitive to being killed by reactive oxygen species, ciprofloxacin, and starvation. M. tuberculosis bacilli depleted for CarD are also unable to replicate and persist in mice. Therefore, the CarD protein is a very attractive drug target, and the development of assays for screening for chemical inhibitors of CarD requires characterization of the essential functions and mechanisms of action of this protein.

Microarray analyses revealed global changes in the transcriptional profiles of mycobacteria during CarD depletion (22). Furthermore, mycobacterial CarD was shown to associate with RNA polymerase (RNAP). These findings led us to hypothesize that CarD might be essential due to its ability to influence gene expression through direct contact with RNAP. Here we investigate this hypothesis and establish that disrupting the interaction between CarD and the β subunit of RNAP has significant effects on mycobacterial survival, resistance to stress, and pathogenesis in murine tissues. In addition, we discovered distinct phenotypic differences between depleting CarD and weakening the CarD/RNAP β1 interaction, suggesting that CarD performs additional cellular functions separate from that of binding the RNAP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media and bacterial strains. (i) M. tuberculosis.

All M. tuberculosis strains were derived from the Erdman strain and were grown at 37°C in 7H9 (broth) or 7H10 (agar) (Difco) medium supplemented with 60 μl/liter oleic acid, 5 g/liter bovine serum albumin (BSA), 2 g/liter dextrose, 0.003 g/liter catalase (OADC), 0.5% glycerol, and 0.05% Tween 80 (broth). Gene switching was used to construct strains of mycobacteria expressing different carD alleles and to test for their viability (17). Specifically, the M. tuberculosis ΔcarD attB∷tet-carD merodiploid strain (as described previously [22]) was transformed with pDB19-Rv3583cWT, pDB19-Rv3583cR25E, pDB19-Rv3583cR47E, or pDB19-Rv3583cR25E,R47E (expresses wild-type M. tuberculosis CarD [CarDWT], CarDR25E, CarDR47E, or CarDR25E,R47E, respectively, from a constitutive Pmyc1-tetO promoter, zeocin resistant) to replace the pMSG430Rv3583c construct (expresses M. tuberculosis CarD from a constitutive Pmyc1-tetO promoter, kanamycin resistant) at the attB site of M. tuberculosis ΔcarD attB∷tet-carD (22). The transformants were selected on zeocin and confirmed for the loss of the pMSG430Rv3583c construct by verifying their inability to grow on kanamycin. The Rv3583c gene from each transformant was sequenced to confirm the presence of the correct sequence. When positive transformants were unattainable in M. tuberculosis ΔcarD attB∷tet-carD (as was the case for the pDB19-Rv3583cR25E and pDB19-Rv3583cR25E,R47E transformations), these mutants were deemed nonviable. The M. tuberculosis ΔcarD attB∷tet-carD strains transformed with pDB19-Rv3583cWT and pDB19-Rv3583cR47E were named mgm3080 and mgm3081, respectively. There is only a single copy of the carD gene in all strains of the mycobacteria used in this paper.

(ii) M. smegmatis.

All M. smegmatis strains were isogenic to mc2155 and were grown at 37°C in LB supplemented with 0.5% dextrose, 0.5% glycerol, and 0.05% Tween 80 (broth). The M. smegmatis strains expressing either hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged or untagged CarDWT, CarDR25E, or CarDR47E were engineered as described for the analogous M. tuberculosis strains using pDB19 expression plasmids and the M. smegmatis carD merodiploid ΔcarD attB∷tet-carD strain (as described previously [22]). The M. smegmatis ΔcarD attB∷tet-carD strains transformed with pDB19-Rv3583cWT, pDB19-Rv3583cR25E, and pDB19-Rv3583cR47E were named mgm1849, csm3, and csm40, respectively. The M. smegmatis Tet-CarD (mgm1703) and control (mgm1701) strains used for the CarD depletion experiments were previously described (22). Rifampin-resistant M. smegmatis ΔcarD attB∷tet-carD, RNAP βS438F, and RNAP βH442R strains were isolated by plating on 200 μg/ml of rifampin. To engineer M. smegmatis RNAP βS438F and RNAP βH442R strains to express CarDWT or CarDR25E, the rifampin-resistant mutants were transformed with pDB19-Rv3583cWT or pDB19-Rv3583cR25E to replace the pMSG430smcarD construct, as just described.

Antibiotics and chemicals.

In mycobacteria, 20 μg/ml kanamycin, 12.5 μg/ml zeocin, 50 μg/ml hygromycin, 20 μg/ml streptomycin (unless otherwise indicated), and 50 ng/ml of anhydrotetracycline (ATc) were used. H2O2 (Fisher Scientific) and rifampin (Sigma) were used at the indicated concentrations.

Bacterial two-hybrid assays.

Plasmids for the two-hybrid analyses were created by the cloning of corresponding NotI/BamHI-digested PCR products into either NotI/BamHI-digested pBRαLN or pACλCI32 (as described in reference 15). The plasmid pACλCI-Mt β1 encodes residues 1 to 236 of the bacteriophage λCI protein fused to residues 52 to 178 of the β subunit of M. tuberculosis RNAP fused to residues 379 to 440 of the β subunit of M. tuberculosis RNAP via two glycine residues, under the control of the isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible lacUV5 promoter. The plasmids pBRα-Mt CarD, pBRα-Mt CarD(1 to 66), and pBRα-Mt transcription-repair coupling factor (TRCF) encode residues 1 to 248 of the Escherichia coli RNAP α subunit fused to full-length M. tuberculosis CarD, residues 1 to 66 of M. tuberculosis CarD, or residues 513 to 653 of M. tuberculosis TRCF, respectively, under the control of tandem lpp and IPTG-inducible lacUV5 promoters. The indicated amino acid substitutions were introduced into pACλCI-Mt β1 and pBRα-CarD(1 to 66) by PCR. The plasmid pBRα encodes the wild-type α subunit and the plasmid pACλCI encodes the bacteriophage λCI protein.

FW102 F′ OL2-62 reporter strain cells (6) that contained the test promoter placOL2-62 driving the expression of a linked lacZ gene on an F′ episome were cotransformed with the indicated pAC- and pBR-derived plasmids. Individual transformants were selected and grown in LB supplemented with carbenicillin (100 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml), and kanamycin (50 μg/ml). The plasmids directed the synthesis of the fusion proteins under the control of IPTG-inducible promoters, and the cells were grown in the presence of 5 μM IPTG. β-Galactosidase assays were performed as described in reference 23 using microtiter plates and a microtiter plate reader. Miller units were calculated as described in reference 23.

Antibiotic survival assays.

For the zone of inhibition assays, 500 μl of a log-phase culture was plated on 7H10 agar. A single 6-mm disk (Sigma) was placed in the middle of the freshly plated bacterial lawn, and 5 μl of either 200 mg/ml streptomycin or 50 mg/ml isoniazid (INH) was spotted on the disk. Water was spotted on a disk on a separate plated bacterial lawn as a control. The plates were then incubated for 2 days before the radius of the zone of inhibition was measured. For transient treatment in liquid culture assays, log-phase cultures in LB broth for M. smegmatis or 7H9 broth for M. tuberculosis were treated with an antibiotic or H2O2 at the stated concentrations. As done previously (22), M. smegmatis cultures were treated for 1 or 2 h, which was adequate in M. smegmatis for us to see an effect of each treatment in wild-type controls. When we tried this same period of time for transient treatment in M. tuberculosis cultures, we observed no effects on the survival of wild-type M. tuberculosis after 2 h. By performing a time course, we determined that 75 h of H2O2 or rifampin treatment in M. tuberculosis cultures was adequate to detect a measurable effect of treatment in wild-type controls. The dilutions were made directly from the treated cultures, and 5 μl of each dilution was spot plated. We have performed similar experiments by centrifuging treated cultures and washing the cell pellets with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before plating dilutions and saw no difference in the rates of survival. Therefore, we chose not to wash the treated cells to avoid the added stress of centrifugation.

Western blotting and immunoprecipitation.

For immunoprecipitation, 50-ml cultures were washed and lysed in 500 μl of NP-40 buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 0.25% NP-40, and Roche Complete protease inhibitor cocktail) by bead beating. Twenty-five microliters of lysate was used for the input sample, and the rest was added to monoclonal anti-HA agarose (Sigma) and rotated overnight at 4°C. The matrix was washed 3 times with NP-40 buffer, and immunoprecipitated protein complexes were eluted with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 500 μg/ml HA peptide (Roche), and protease inhibitors. For the Western blot analyses, CarD HA and RNAP β were detected using mouse monoclonal antibodies specific for HA (Sigma) and RNAP β (clone 8RB13; Neoclone, Madison, WI), respectively. A rabbit polyclonal antibody to CarD (22) was used to detect the CarD protein in the depletion experiments shown in Fig. 5, and a monoclonal antibody to CarD (clone 10F05; Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center Monoclonal Antibody Core Facility) was used to detect CarD in the depletion experiments shown in Fig. 6.

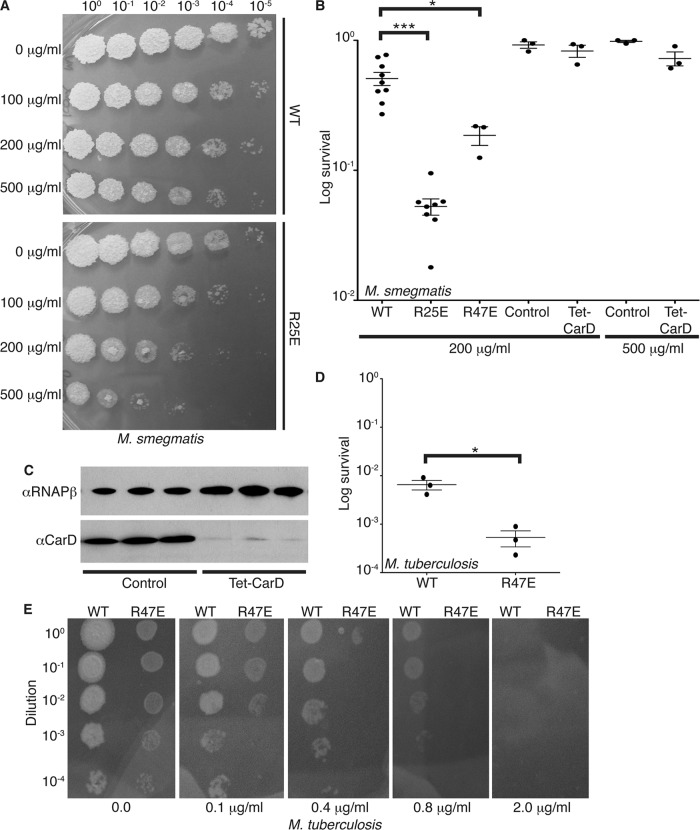

Fig 5.

Weakening the interaction between CarD and the RNAP increases the sensitivity of mycobacteria to rifampin. (A and B) Survival of M. smegmatis strains during transient rifampin treatment. The log-phase M. smegmatis ΔcarD attB∷tet-carD strains expressing CarDWT, CarDR25E, or CarDR47E growing in LB were treated for 1 h with 100 μg/ml, 200 μg/ml, or 500 μg/ml rifampin before dilutions were plated to determine the surviving CFU. M. smegmatis Tet-CarD and control strains were grown in LB without ATc for 13 h to deplete the carD transcript levels in Tet-CarD and treated for 1 h with 200 μg/ml or 500 μg/ml rifampin, and dilutions were plated on LB plus ATc to determine the surviving CFU. (A) Representative experiment. (B) Survival as the mean ratio of CFU in treated cultures to that in untreated cultures ± the SEM, with each sample represented by a black circle. (C) Western blot analysis of protein lysates from M. smegmatis Tet-CarD and control strains grown in LB without ATc for 13 h to confirm depletion of CarD in Tet-CarD samples. RNAP β was detected in each sample as a loading control. (D) Survival of M. tuberculosis strains during transient rifampin treatment. The M. tuberculosis ΔcarD attB∷tet-carD strains expressing CarDWT or CarDR47E growing in 7H9 broth were transiently treated for 75 h with 200 μg/ml of rifampin. After treatment, dilutions were plated on 7H10 plates, and the survival was calculated as a ratio of CFU after treatment to that in untreated cultures. The graph shows the mean ± SEM of data from three experiments, with each sample represented by a black circle. The significance levels in panels B and D were determined as described for Fig. 3. (E) Tenfold dilutions starting at 2.5 × 108 CFU of M. tuberculosis strains expressing CarDWT or CarDR47E were plated on 7H10 plates containing 0.0, 0.1, 0.4, 0.8, or 2 μg/ml of rifampin. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 6 weeks, and the MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of rifampin that inhibited all growth of the M. tuberculosis strain. The significance levels for all panels were determined as described for Fig. 3.

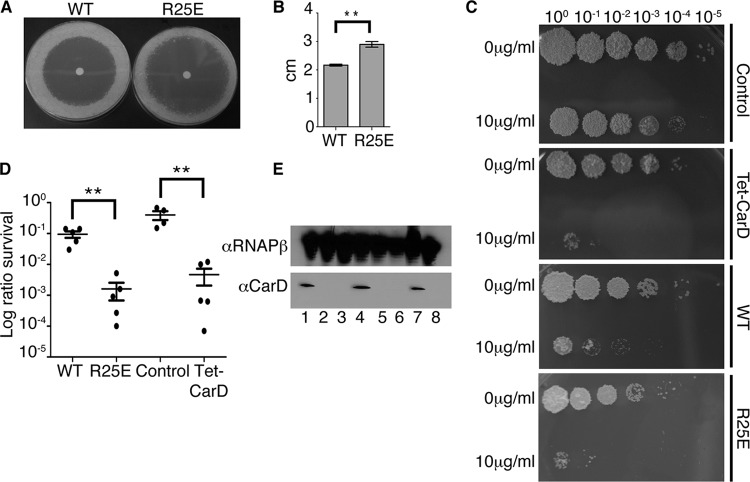

Fig 6.

Weakening the interaction between CarD and the RNAP and depleting CarD increases sensitivity to streptomycin. (A and B) Survival of the M. smegmatis strains during the disk zone of inhibition assays with streptomycin. Five hundred microliters of the log-phase M. smegmatis ΔcarD attB∷tet-carD strains expressing CarDWT or CarDR25E was plated on LB agar, and a disk spotted with 5 μl of 200-mg/ml streptomycin was placed in the middle of the bacterial lawn. (A) Representative experiment. (B) The radius of the zone of inhibition as the mean ± SEM of data from three biological replicates for each strain. (C and D) Survival of M. smegmatis strains during transient streptomycin treatment. The log-phase M. smegmatis ΔcarD attB∷tet-carD strains expressing CarDWT or CarDR25E growing in LB were treated for 2 h with 10 μg/ml streptomycin before the dilutions were plated to determine the surviving CFU. M. smegmatis Tet-CarD and control strains were grown in LB without ATc for 13 h to deplete carD transcript levels in Tet-CarD and treated for 2 h with 10 μg/ml streptomycin, and dilutions were plated on LB plus ATc to determine the surviving CFU. (C) Representative experiment. (D) Survival as the mean ratio of CFU in treated cultures to that in untreated cultures ± SEM, with each sample represented by a black circle. (E) Western blot analysis of protein lysates from M. smegmatis Tet-CarD (lanes 2, 3, 5, 6, and 8) and control (lanes 1, 4, and 7) strain replicates grown in LB without ATc for 13 h to confirm the depletion of CarD in Tet-CarD samples. The RNAP β subunit was detected in each sample as a loading control. The significance levels for all panels were determined as described for Fig. 3.

Animal infections.

Before infection, exponentially replicating M. tuberculosis mgm3080 (CarDWT) and mgm3081 (CarDR47E) strains were washed in PBS plus 0.05% Tween 80 and sonicated to disperse clumps. Eight- to nine-week-old female C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratory) or H2K gp91phox−/− mice (kindly provided by Kathy Frederick and Emil Unanue) were exposed to 8 × 107 CFU of the appropriate strain in an inhalation exposure system (Glas-Col) that delivers 100 bacteria per animal. The bacterial burden was determined by plating serial dilutions of lung and spleen homogenates onto 7H10 agar plates. The plates were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 3 weeks prior to counting colonies. All procedures involving animals were conducted according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines for the housing and care of laboratory animals, and they were performed in accordance with institutional regulations after protocol review and approval by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine (protocol 20100190, Analysis of Mycobacterial Pathogenesis). Washington University is registered as a research facility with the United States Department of Agriculture and is fully accredited by the American Association of Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. The Animal Welfare Assurance documentation is on file with the Office for Protection from Research Risks of the NIH. All animals used in these experiments were subjected to no or minimal discomfort. All mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation, which is approved by the American Veterinary Medical Association Panel on Euthanasia.

RESULTS

Single point mutations in the CarD RID protein and RNAP β1 domain disrupt their interaction.

The N terminus of the CarD protein displays amino acid sequence similarity to that of the RNAP interaction domain (RID) of the TRCF (the product of the mfd gene). We previously reported that Thermus thermophilus CarD interacts with the same region at the N terminus of the RNAP β subunit (the β1 domain) as the T. thermophilus TRCF (22, 24). Studies of Myxococcus xanthus proteins have reported similar findings (10). To establish whether M. tuberculosis CarD also interacts with the β1 domain of M. tuberculosis RNAP, we used a bacterial two-hybrid assay (Fig. 1A) (7, 8). In this assay, contact between a protein domain fused to a component of RNAP (here, the α subunit) and a partner protein fused to a DNA-binding protein (here, the CI protein of bacteriophage λ) activates transcription of a lacZ reporter gene under the control of a test promoter bearing an upstream recognition site for the DNA-binding protein (in this case, a λ operator). We fused either the full-length M. tuberculosis CarD or the CarD RID (residues 1 to 66) to the α subunit N-terminal domain (α-NTD), replacing the α subunit C-terminal domain, and the M. tuberculosis β1 domain was fused to the CI protein of bacteriophage λ. We detected a large increase in transcription from the test promoter when we induced the synthesis of the CI-β1 fusion protein along with either the full-length CarD α fusion protein or the CarD RID α fusion protein (Fig. 1B). This demonstrated that M. tuberculosis CarD, via its N-terminal RID domain, interacts with the β1 domain of M. tuberculosis RNAP. Although the mode of binding of CarD and TRCF to RNAP is the same, we have previously shown that these proteins have distinct cellular functions (22).

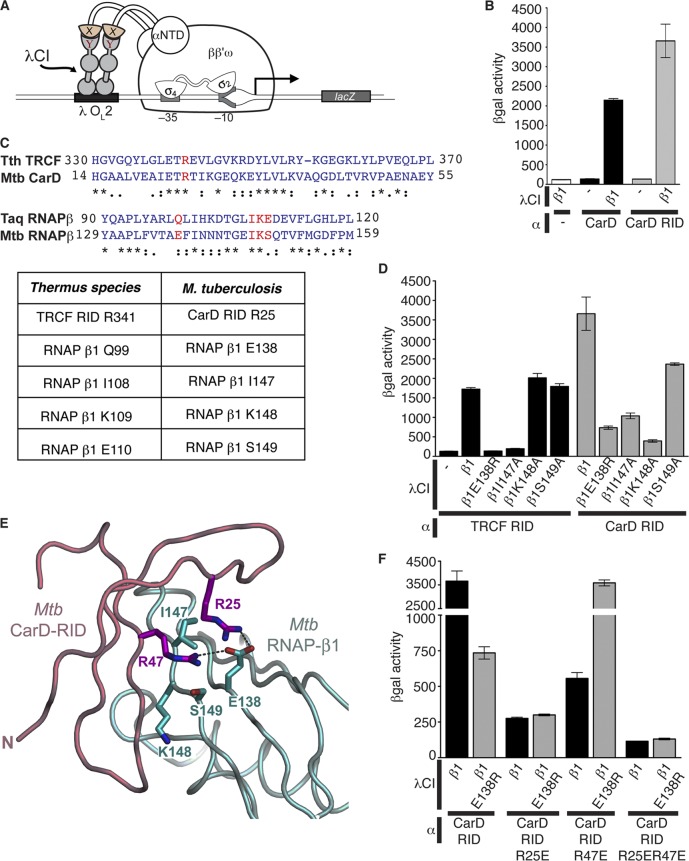

Fig 1.

M. tuberculosis CarD and TRCF interact with the RNAP β1 domain. (A) The cartoon depicts how contact between a protein domain (X) fused to the α subunit of the E. coli RNAP and a partner domain (Y) fused to a DNA-binding protein (the CI protein of bacteriophage λ) activates transcription from the test promoter placOL2-62, which bears an upstream recognition site for λCI (λOL2). (B) Results of β-galactosidase assays performed with FW102 OL2-62 cells that contained two compatible plasmids: one that encoded M. tuberculosis CarD (black bars) or CarD RID (residues 1 to 66; gray bars) protein fused to α or unfused to α (designated −; white bar) and another that encoded the M. tuberculosis RNAP β1 protein (residues 52 to 178-GG-379 to 440) fused to λCI or λCI itself (designated −). (C) Alignments of the T. thermophilus TRCF RID region with the M. tuberculosis CarD RID region and T. aquaticus RNAP β1 with M. tuberculosis RNAP β1. Thermus sp. residues are based on alignments shown in Fig. 2 of reference 24. An asterisk indicates a fully conserved residue, a colon indicates conservation between groups of strongly similar properties, and a period indicates conservation between groups of weakly similar properties. The residues highlighted in red are listed in the table as residues in M. tuberculosis that correspond to the amino acids previously characterized in Thermus sp. to participate in the interaction between TRCF and RNAP β1 (24). (D) Results of β-galactosidase assays performed with FW102 OL2-62 cells that contained two compatible plasmids: one that encoded M. tuberculosis TRCF RID (residues 513 to 653; black bars) or the M. tuberculosis CarD RID (residues 1 to 66; gray bars) protein fused to α and another that encoded the indicated M. tuberculosis RNAP β1 protein (residues 52 to 178-GG-379 to 440) fused to λCI or λCI itself (designated −). (E) Homology model (19) of M. tuberculosis CarD RID with M. tuberculosis RNAP β1 based on the crystal structure of the T. thermophilus TRCF RID with T. aquaticus RNAP β1 (24). Proteins are shown as backbone ribbons, with the CarD RID in light pink and RNAP β1 in light cyan. The side chains of residues at the interaction interface discussed in the text are shown (CarD RID, magenta; RNAP β1, cyan). (F) Results of β-galactosidase assays performed with FW102 OL2-62 cells that contained two compatible plasmids: one that encoded the indicated M. tuberculosis CarD RID (residues 1 to 66) protein fused to α and another that encoded the indicated M. tuberculosis RNAP β1 protein (residues 52 to 178-GG-379 to 440) fused to λCI. All bar graphs show the averages of three independent measurements and standard deviations.

Having established that we could use the two-hybrid assay to detect the M. tuberculosis CarD/β1 interaction, we next sought to determine whether M. tuberculosis CarD and TRCF interact with the RNAP β subunit in a similar manner. The X-ray crystal structure of the T. thermophilus TRCF RID complexed with the Thermus aquaticus RNAP β1 domain (24) revealed that T. thermophilus TRCF RID R341 forms a hydrogen bond with RNAP β1 Q99, as well as polar interactions with RNAP β1 E110. The RNAP β1 residues I108 and K109 are also central to the protein/protein interface, making extensive van der Waals contacts with the TRCF RID (24). T. thermophilus TRCF RID R341 and T. aquaticus RNAP β1 E110 correspond to Escherichia coli TRCF RID L499 and RNAP β1 E119, respectively, which were both previously demonstrated to be important for the interaction between the TRCF and RNAP β in E. coli (6, 20).

To extrapolate these structural insights to mycobacteria, we aligned the T. aquaticus β1 sequence with the β1 domain from M. tuberculosis and concluded that residues E138, I147, K148, and S149 of M. tuberculosis RNAP β1 correspond to residues Q99, I108, K109, and E110 in T. aquaticus RNAP β1, respectively (24) (Fig. 1C). To determine whether these residues were critical to the TRCF RID/β1 interaction in mycobacteria, we performed bacterial two-hybrid experiments between the M. tuberculosis TRCF RID and RNAP β1 harboring one or more mutations in these residues. The M. tuberculosis RNAP β1E138R and RNAP β1I147A substitutions had dramatic effects on the strength of the interaction with the TRCF RID (Fig. 1D). In contrast, alanine substitutions at M. tuberculosis RNAP β1 K148 or S149 did not inhibit the association with the TRCF RID.

We next used the bacterial two-hybrid assay to determine if the same mutations in M. tuberculosis RNAP β1 that weakened the interaction with the TRCF RID would also affect the association with the M. tuberculosis CarD RID (residues 1 to 66). Similar to their effect on the TRCF RID interaction, the RNAP β1E138R and RNAP β1I147A substitutions weakened the interaction with the CarD RID (Fig. 1D). The β1K148A and β1S149A substitutions in the M. tuberculosis RNAP β1 domain also weakened CarD RID binding, although these same mutations were inconsequential for TRCF RID binding. Therefore, CarD and TRCF associate with the RNAP β subunit in similar manners, although with subtle differences.

To identify residues in CarD that are important for the CarD/RNAP interaction, we generated a homology model of the M. tuberculosis CarD RID interacting with the RNAP β1 domain based on the structure of the Thermus sp. TRCF RID/RNAP β1 complex (Protein Data Bank accession number 3MLQ [24]) (Fig. 1E). According to our modeled structure, M. tuberculosis CarD RID R25 interacts with M. tuberculosis RNAP β1 E138 (homologous to the Thermus sp. TRCF-RID R341:RNAP β1 Q99 interaction) (Fig. 1E). In addition to M. tuberculosis CarD RID R25, the model structure predicts that another arginine, that at position 47, would interact with M. tuberculosis RNAP β1 E138. We made arginine-to-glutamic acid substitutions at position 25 or 47 in our CarD RID bacterial two-hybrid constructs to test the effects of these mutations on the interaction between CarD and RNAP β1. Either substitution on its own greatly diminished the ability of these proteins to interact, with CarD RIDR25E having the most severe effect (Fig. 1F). A double point mutation (CarD RIDR25E,R47E) completely abolished the interaction. We were able to fully suppress the effect of the CarD RIDR47E mutation with the RNAP β1E138R substitution, confirming the specific interaction between these two residues predicted from the structural model (Fig. 1F). The RNAP β1E138R mutation did not suppress the effects of the CarD RIDR25E mutation, suggesting that the CarD RIDR25E substitution disrupts additional contacts between these proteins. This is supported by the Thermus sp. TRCF RID/β1 structure, where Thermus sp. TRCF RID R341 (corresponding to M. tuberculosis CarD RID R25) interacts with multiple residues in the β1 subunit (24).

The CarD/RNAP β1 interaction is critical for mycobacterial survival.

Having identified the amino acid substitutions that disrupt the CarD/RNAP β1 interaction, we next sought to determine whether disrupting this interaction would affect mycobacterial viability. We chose to examine only the effects of point mutations in CarD and not in RNAP β1 for our assays in mycobacteria to avoid interfering with the TRCF/RNAP interaction. Thus, we attempted to replace the carD gene of M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis with the alleles encoding CarDR25E, CarDR47E, or the CarDR25E,R47E double mutant using a gene-switching technique (17). We successfully replaced the wild-type (WT) carD gene in M. smegmatis with an allele expressing CarDR25E or CarDR47E and in M. tuberculosis with an allele expressing CarDR47E (Fig. 2A). Using the gene-switching technique, we were unable to engineer a viable CarDR25E,R47E double mutant, which is incapable of interacting with RNAP β1 (Fig. 1F), indicating that the interaction between CarD and the RNAP is important for viability (Fig. 2A). In fact, even the CarDR25E substitution was unattainable in M. tuberculosis, again emphasizing that attenuating the CarD/RNAP β1 interaction compromises survival.

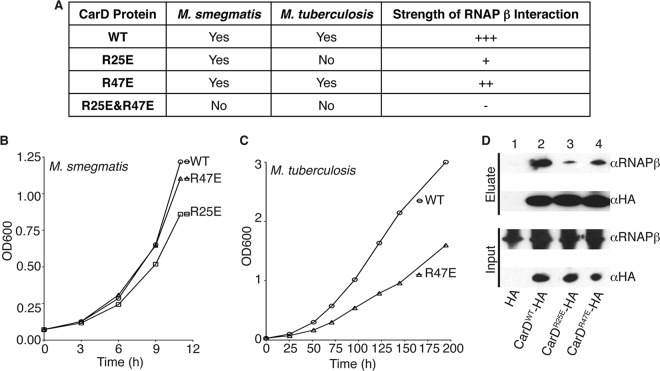

Fig 2.

Weakening the interaction between CarD and the RNAP compromises the growth of mycobacteria. (A) Table of mycobacterial strains engineered by replacing the CarDWT expression cassette with one that expresses the designated mutant and mutants that were unattainable by gene switching. The strength of RNAP interaction is based on the bacterial two-hybrid results shown in Fig. 1. (B and C) Representative growth curve from 5 replicates of M. smegmatis (B) and 3 replicates of M. tuberculosis (C) ΔcarD attB∷tet-carD strain expressing CarDWT, CarDR25E, or CarDR47E. (D) Immunoprecipitation experiments with a monoclonal antibody specific for HA in the M. smegmatis ΔcarD attB∷tet-carD strain expressing untagged CarDWT (lane 1, also expresses HA peptide), CarDWT-HA (lane 2), CarDR25E-HA (lane 3), or CarDR47E-HA (lane 4). Inputs (before immunoprecipitation) and eluates were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies specific for either RNAP β or HA.

We measured growth curves of the viable M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis mutants and found that as the interaction of CarD with RNAP was weakened, the growth rate also decreased (Fig. 2B and C). Based on five replicate experiments, the doubling time of the M. smegmatis CarDR25E mutant was 1.198 times (standard deviation, 0.067) slower than that of the wild-type control strain. Likewise, the doubling time of the M. tuberculosis CarDR47E mutant was 1.181 times (standard deviation, 0.001) slower than that of the wild-type control strain in three replicate experiments. The phenotypes associated with interfering with the CarD/RNAP β interaction were dramatically more severe in M. tuberculosis than in M. smegmatis. This was evidenced by the decrease in the growth rate of the M. tuberculosis CarDR47E mutant compared to that in the wild-type CarD-expressing strain, while in M. smegmatis the analogous mutant grew at wild-type rates. These findings suggest that an optimal interaction between CarD and RNAP β is more critical for the growth of M. tuberculosis than of M. smegmatis, and further comparison of these bacteria may shed light on the functions of CarD.

Consistent with the bacterial two-hybrid results, coimmunoprecipitation experiments in mycobacteria demonstrated that even though the intracellular levels of CarD and RNAP β were unchanged, CarDR25E and CarDR47E mutants coprecipitated less RNAP β than CarDWT (Fig. 2D). These data confirmed that the R25E and R47E substitutions in CarD compromise the association with RNAP and emphasize the importance of the CarD/RNAP β1 interaction for mycobacterial growth and survival. In light of these findings, we predict that small molecules that interfere with the CarD/RNAP β1 interaction could be promising novel chemotherapies for killing M. tuberculosis.

The CarD/RNAP β1 interaction is essential for the ability of mycobacteria to resist killing by reactive oxygen species.

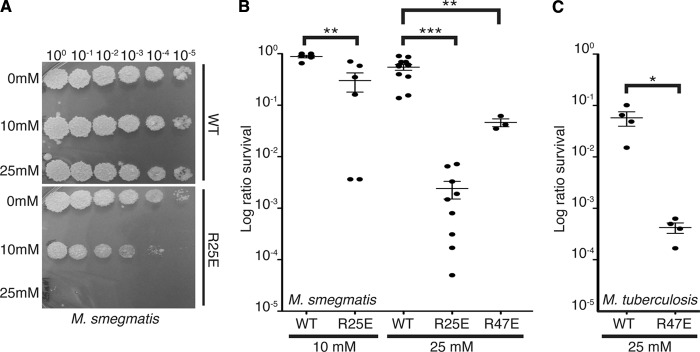

During infection, M. tuberculosis must withstand an arsenal of host-derived stresses, including the production of reactive oxygen species by the oxidative burst (5). We previously showed that depleting CarD dramatically increases the sensitivity of mycobacteria to oxidative stress (22). To test whether weakening the CarD/RNAP β1 interaction would have a similar effect, log-phase cultures of M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis strains expressing different carD alleles were treated with either 10 mM or 25 mM H2O2 before dilutions were plated to count the surviving CFU (Fig. 3). All CarD mutants were more sensitive to H2O2 treatment than were the wild type, with the M. smegmatis CarDR25E mutant being more sensitive than was M. smegmatis expressing CarDR47E, demonstrating that the strength of the CarD/RNAP β1 interaction directly correlates to survival in the presence of reactive oxygen species (Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

Weakening the interaction between CarD and the RNAP compromises the survival of mycobacteria during oxidative stress. (A and B) Survival of M. smegmatis strains during oxidative stress. The log-phase M. smegmatis ΔcarD attB∷tet-carD strains expressing CarDWT, CarDR25E, or CarDR47E in LB were treated for 1 h with either 10 mM or 25 mM H2O2. After treatment, dilutions were plated on LB. Panel A shows one such experiment, and B graphically represents survival as a ratio of CFU in treated cultures to that in untreated cultures. (C) Survival of the M. tuberculosis strains during oxidative stress. The log-phase M. tuberculosis ΔcarD attB∷tet-carD strains expressing CarDWT or CarDR47E growing in 7H9 broth were treated for 75 h with 25 mM H2O2. After treatment, dilutions were plated on 7H10 agar, and survival is graphically represented as the ratio of CFU in treated cultures to that in untreated cultures. The graphs in panels B and C show the mean± standard error of the mean (SEM), and each sample is represented by a black circle. The significance levels in panels B and C were determined by calculating P values by Student's t test; an asterisk indicates significance with a P value of <0.05, two asterisks indicate significance with a P value of <0.01, and three asterisks indicate significance with a P value of <0.005.

Weakening the CarD/RNAP β1 interaction affects the pathogenesis of M. tuberculosis in murine tissues.

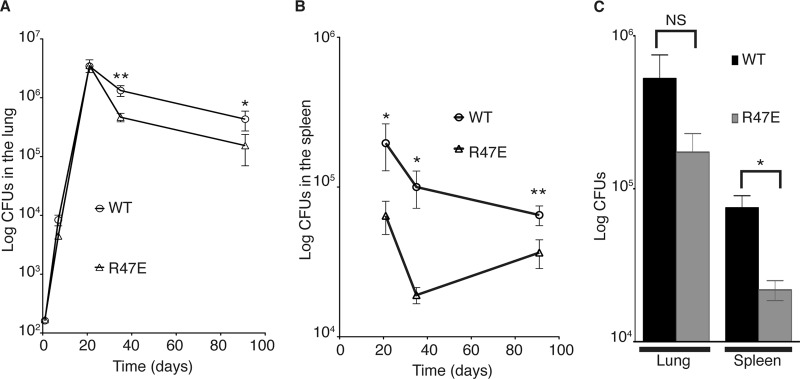

CarD is essential for acute and persistent M. tuberculosis infections in mice (22). We hypothesized that the optimal association of CarD with RNAP would be particularly critical for mycobacteria to resist host-inflicted oxidative stress during infection, and disrupting the interaction could compromise M. tuberculosis survival in the host. To investigate the effect of weakening the association of CarD with RNAP on M. tuberculosis pathogenesis, we infected C57BL/6 mice with M. tuberculosis strains expressing either CarDWT or the CarDR47E mutant. These strains showed similar virulence during acute infection of the murine lungs (Fig. 4A). However, at 5 weeks postinfection, which is early during a persistent infection, the bacterial titers of the M. tuberculosis CarDR47E mutant were a half-log lower than those of the CarDWT-expressing bacteria in the lung and were unable to persist at the same level as the CarDWT-expressing strain (Fig. 4A). The attenuation of the M. tuberculosis CarDR47E strain was more dramatic in the spleens of infected mice, where the titer of the mutant was already a half-log lower than that of the CarDWT-expressing bacteria by 3 weeks postinfection (Fig. 4B), despite identical levels between strains in the lungs at that time point (Fig. 4A). In addition, the titer of the mutant was more than a half-log lower than that of the CarDWT-expressing bacteria by 5 weeks in the spleen (Fig. 4B), suggesting that weakening the association of CarD with the RNAP causes a defect that is particularly detrimental to dissemination to or survival in the spleen. Given that the R47E substitution in CarD only has partial effects on RNAP binding (Fig. 1F and 2D) and that mutations that further decrease the affinity of CarD to RNAP β are unattainable in M. tuberculosis (Fig. 2A), we predict an even more dramatic attenuation in pathogenesis if the CarD/RNAP β1 association is more severely inhibited.

Fig 4.

The association of CarD with the RNAP is required for the persistence of M. tuberculosis in mice. (A and B) Pathogenesis of M. tuberculosis strains in C57BL/6 mice. Shown are bacterial titers in the lungs (A) and spleens (B) of C57BL/6 mice infected with M. tuberculosis expressing either CarDWT (open circles) or CarDR47E (open triangles). Each time point is the mean ± SEM of data from seven mice per strain, combined from two experiments. (C) Pathogenesis of M. tuberculosis strains in H2K gp91phox−/− mice. Shown is a graph of the total CFU in the lungs of gp91phox−/− mice infected with 80 to 120 CFU of M. tuberculosis expressing either CarDWT (black bars) or CarDR47E (gray bars) at 5 weeks postinfection. Data are means ± SEM of results for three mice per strain. The significance levels for data in all panels were determined as described for Fig. 3. NS, not significant.

Since we had observed that the M. tuberculosis strains expressing CarDR47E were more sensitive to oxidative stress (Fig. 3), one possible cause for the attenuation of these strains is their inability to resist the host oxidative burst. The phagocytic oxidative burst requires the NADPH oxidase gp91phox and p47phox proteins to produce superoxide. Infection of mice lacking the p47phox gene with wild-type M. tuberculosis results in a significant increase in bacterial growth over days 14 to 30 of infection, indicating that the phagocytic oxidative burst is transiently important in controlling infection (5). The infection of gp91phox−/− mice (18) with M. tuberculosis strains expressing either CarDWT or CarDR47E demonstrated that the mutant was still attenuated for infection despite the absence of the phagocytic oxidative burst (Fig. 4C), indicating that the in vivo phenotype of the CarDR47E strain must also be due to sensitization to additional host-derived stresses.

Compromising the CarD/RNAP β1 interaction increases rifampin sensitivity in mycobacteria, whereas depleting CarD does not.

The interaction between CarD and the β subunit of RNAP would be a novel target for tuberculosis treatment; however, it would not be the first time that the bacterial RNAP was targeted. Rifampin, a potent, broad-spectrum antibiotic, is a key component of antituberculosis therapy that binds the RNAP β subunit within the DNA/RNA channel and is predicted to block directly the path of the elongating RNA (3, 9). Although the rifampin binding site is distinct from the binding site of CarD on the β subunit, we were curious whether weakening the CarD/RNAP interaction would affect the efficacy of rifampin treatment of mycobacteria. To test this, we transiently treated M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis strains expressing CarDWT, CarDR25E (M. smegmatis only), or CarDR47E (M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis) with rifampin and monitored survival by plating for CFU (Fig. 5A). In both mycobacterial species, the strength of the CarD interaction with RNAP directly correlated to survival during rifampin treatment (Fig. 5A, B, and D), thus showing that weakening the association of CarD with RNAP increases the potency of rifampin. In a similar experiment, we tested whether depleting CarDWT levels made M. smegmatis more sensitive to rifampin treatment, and we found that it did not (Fig. 5B and C). This implies that it is the specific interference of the CarD/RNAP interaction that compromises the bacteria's survival during rifampin treatment.

Since we had shown that M. tuberculosis strains expressing CarDR47E instead of CarDWT were more sensitive to transient treatment with rifampin, we were curious how weakening the CarD/RNAP interaction would affect the MIC of the rifampin treatment of M. tuberculosis. To test the minimum concentration of rifampin that is able to halt the growth of M. tuberculosis, we plated dilutions of strains expressing CarDWT or CarDR47E onto 7H10 plates containing a range of rifampin concentrations (Fig. 5E). The MIC of the rifampin treatment of M. tuberculosis expressing CarDWT was ∼2 μg/ml, which is comparable to published values for wild-type strains (16). In contrast, the MIC of the rifampin treatment of M. tuberculosis expressing CarDR47E was ∼0.8 μg/ml, and the survival of the CarDR47E-expressing strain in the presence of 0.4 μg/ml rifampin was 3 logs lower than that of the CarDWT-expressing strains (Fig. 5E). These data show that weakening the association of CarD with the RNAP decreases the MIC of rifampin, suggesting that targeting the CarD/RNAP β interaction could increase the efficacy of rifampin treatment. In addition, we predict that inhibiting the CarD/RNAP β interaction more dramatically than the R47E mutation would further increase the sensitivity to rifampin.

We had also previously shown that depleting CarD increased the sensitivity of M. smegmatis to ciprofloxacin treatment (22). In contrast, weakening the M. smegmatis CarD/RNAP β1 interaction had no effect on sensitivity to 10 μg/ml ciprofloxacin treatment in 2 h of transient-treatment liquid culture assays (data not shown). Therefore, although depletion of CarDWT and weakening the CarD/RNAP β1 interaction have similar effects on resisting reactive oxygen species, these alterations of CarD function have different effects on the susceptibilities to rifampin and ciprofloxacin. This raised the question of how CarD depletion and the CarD RID mutants would affect the sensitivity of mycobacteria to other antibiotics used to treat M. tuberculosis infection. To address this, we examined CarD-mediated resistance to isoniazid (INH), pyrazinamide (PZA), and streptomycin in M. smegmatis. The depletion of CarD or weakening of the CarD/RNAP β interaction had no effect on sensitivity to up to 8 mg/ml PZA in media at pH 5.2 in 2 h of transient-treatment liquid culture assays and no reproducible effect on INH sensitivity in the disk zone of inhibition assays, transient-treatment liquid culture assays with up to 500 μg/ml INH, or MIC determination assays done by plating strains on 7H10 agar containing INH (as done previously [14]) (data not shown). However, we found that the M. smegmatis CarDR25E strain, as well as a strain depleted for CarDWT, were significantly more sensitive to streptomycin treatment than control strains in both the disk zone of inhibition assays (Fig. 6A and B, CarDR25E only) and transient-treatment liquid assays (Fig. 6C to E, CarDR25E and CarD depletion). Thus, the depletion of CarD and the weakening of the CarD/RNAP association have the same effect on sensitivity to streptomycin.

Rifampin resistance mutations in RNAP β do not rescue the sensitivity of mycobacteria to weakening of the CarD/RNAP interaction.

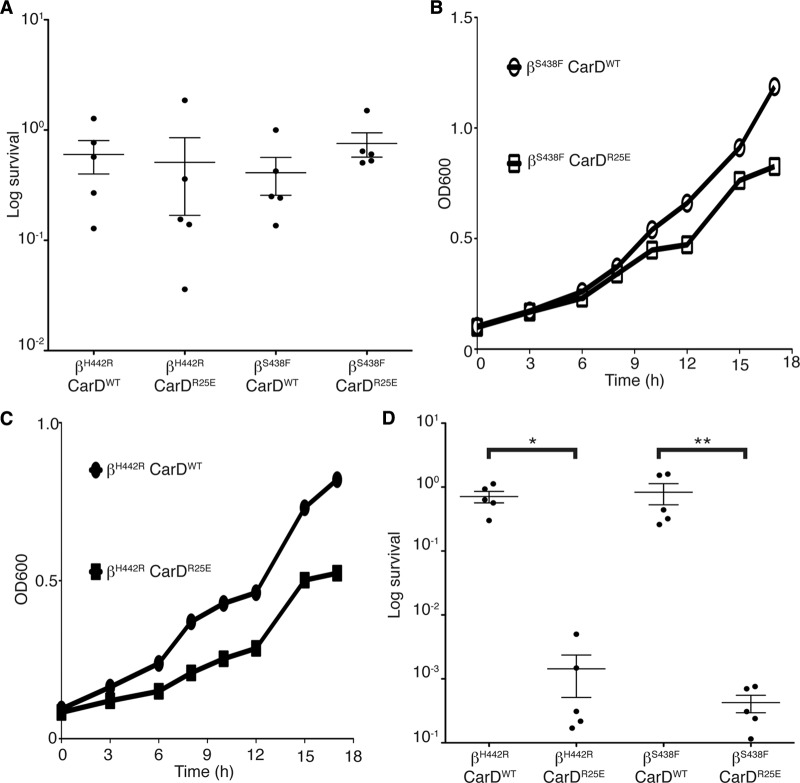

Rifampin resistance is a characteristic of the MDR M. tuberculosis strains, and almost all resistance mutations map to the RNAP β subunit. Since we had observed that weakening the CarD/RNAP interaction increased the sensitivity of mycobacteria to rifampin, we tested if we could restore rifampin sensitivity in resistant mutants by interfering with CarD's association with the RNAP. We selected for rifampin-resistant strains of M. smegmatis on plates containing 200 μg/ml of rifampin. We sequenced the rpoB gene (encoding the RNAP β subunit) of the colonies that grew and selected two strains with mutations in residues that have been reported to be altered in clinical isolates of the MDR M. tuberculosis: RNAP βS438F and RNAP βH442R (4, 13). These mutations are predicted to block the rifampin binding pocket. Each rifampin-resistant mutant was engineered to express either CarDWT or CarDR25E and treated with rifampin to test if they retained rifampin resistance. Figure 7A shows that despite the weaker association of CarD with RNAP, the RNAP βS438F- and RNAP βH442R-expressing strains retained resistance to 500 μg/ml of rifampin. This indicated that these mutations still interfere with the binding of rifampin, and therefore, the effects of the CarD-RID mutants on rifampin sensitivity could not be observed.

Fig 7.

Rifampin-resistant mutants are still sensitive to interference with the CarD/RNAP interaction. (A) Survival of M. smegmatis strains during rifampin treatment. The M. smegmatis strains resistant to rifampin due to substitutions in RNAP β at either position S438 (βS438F) or H442 (βH442R) were engineered to express either CarDWT or CarDR25E. The log-phase βS438F CarDWT, βS438F CarDR25E, βH442R CarDWT, and βH442R CarDR25E cultures in LB were treated for 1 h with 500 μg/ml in rifampin. After treatment, dilutions were plated on LB, and survival was determined as a ratio of CFU after treatment to that in untreated cultures. The graph shows the mean ± SEM, and each sample is represented by a black circle. (B and C) Representative growth curves from 4 replicates each of M. smegmatis βS438F CarDWT (open circles), βS438F CarDR25E (open squares), βH442R CarDWT (closed circles), and βH442R CarDR25E (closed squares) in LB. (D) Survival of M. smegmatis strains during H2O2 treatment. The log-phase M. smegmatis βS438F CarDWT, βS438F CarDR25E, βH442R CarDWT, and βH442R CarDR25E cultures were treated for 1 h with 25 mM H2O2. After treatment, dilutions were plated on LB, and survival was determined as a ratio of CFU after treatment to that in untreated cultures. The graph shows the mean ± SEM, and each sample is represented by a black circle. The significance levels were determined as described for Fig. 3.

The mutations in RNAP β that confer rifampin resistance may alter the conformation of the RNAP and could potentially have allosteric effects on the interactions of RNAP-associated factors, like CarD. Thus, we inquired whether a rifampin resistance mutation in RNAP β would affect the phenotypes of interference with the CarD/RNAP interaction. To examine this, we measured the growth rates and sensitivities to oxidative stress of the M. smegmatis rifampin-resistant mutants expressing either CarDWT or CarDR25E. The effect on the growth rates in M. smegmatis rifampin-resistant mutants varied based on the RNAP β mutation. CarDWT- and CarDR25E-expressing strains in the RNAP βS438F mutant background grew at similar rates, where the average ratio of CarDR25E to CarDWT doubling times was 0.988, with a standard deviation of 0.047 (Fig. 7B). However, strains expressing CarDR25E grew 1.229 times (standard deviation, 0.066) slower than did CarDWT-expressing strains in the RNAP βH442R background (Fig. 7C). In the presence of either rifampin-resistant mutation in RNAP β, the CarDR25E-expressing strains still showed increased susceptibility to oxidative stress (Fig. 7D). This demonstrates that rifampin-resistant mycobacterial strains are still compromised by weakening the CarD/RNAP interaction.

DISCUSSION

CarD represents a new class of RNAP-binding proteins that are absent from the model organism Escherichia coli but are ubiquitous in mycobacteria and conserved in many other eubacteria. Thus, our findings in mycobacteria expand the paradigms of transcription regulation and stress responses that have been established in model systems and then translate these processes to pathogenesis. To gain clues into the possible functions of CarD, our group and others have turned to the wealth of knowledge regarding TRCF due to the similarity of the RNAP interaction domains (RIDs) of these two proteins. Before our direct comparison of the CarD RID/RNAP β1 and TRCF RID/RNAP β1 complexes, the intricacies of these interactions would have been assumed to be the same due to their shared interaction surface on the RNAP. However, our analyses revealed subtle differences between the ways these proteins associate with RNAP β1 that may be relevant to their functional differences, strongly suggesting that we cannot settle on the TRCF RID/RNAP β1 structure as an absolute model for CarD's interaction with the RNAP, and an analogous structure of CarD with RNAP β1 is necessary to understand fully the CarD/RNAP interaction and CarD function.

In our original report of mycobacterial CarD, we used a tetracycline-inducible promoter system to deplete CarD transcript levels (which resulted in lower CarD protein levels) to study the effects of decreased CarD levels on the cell (22). The depletion of CarD led to pleiotropic effects in mycobacteria, and until now it was unknown what functions of CarD contributed to its essentiality. Currently, the only known activity of CarD is binding the RNAP through its N-terminal RID, but we have also shown that this activity is not sufficient for CarD function, since the RID alone cannot support mycobacterial viability (22). Thus, it was important to investigate what roles of CarD are mediated through its interaction with RNAP in order to begin to address the mechanism of action of CarD. In this paper, we have isolated CarD point mutants that do not change the abundance of the CarD protein but instead decrease its affinity to the RNAP β subunit. This has allowed us to examine functions of CarD that are specifically dependent on the interaction with RNAP β.

We have established that the interaction between CarD and the RNAP β subunit is required for mycobacterial viability and virulence and is thus a valid target for the development of screens for the identification of small-molecule inhibitors. Small-molecule inhibitors of proteins, like CarD, that are necessary for M. tuberculosis to tolerate stresses during infection would be promising candidates for compromising the pathogen and potentially shortening the duration of therapy. In general, it is thought that a protein/protein interaction is not an ideal drug target compared to the catalytic domain of an enzyme, but we believe that the sensitivity of the CarD/RNAP interaction to single-residue changes suggests that a small molecule could also interfere. The success of rifampin is also an excellent example of the efficacy of targeting the RNAP complex with antibiotics. Therefore, these studies provide the prelude to a new avenue of drug development involving screens for chemical inhibitors of the CarD/RNAP interaction that will not only be relevant to mycobacterial infections but could also be important for diverse bacterial pathogens that encode CarD homologs. In addition, we show that weakening the CarD/RNAP interaction also increases the sensitivity of M. tuberculosis to rifampin treatment. Although the mechanism of rifampin sensitivity in the CarD-RID mutants is currently unclear, further investigations into this phenomenon will provide much-needed insight into the mechanism of action of CarD regulation of transcription and will serve as a platform for investigating the possibility of increasing the potency of rifampin.

We had hypothesized that the effects of weakening the CarD/RNAP interaction would be similar to the effects of decreasing CarD protein levels. Surprisingly, phenotypic analyses revealed a more complicated situation. For instance, the depletion of CarD confers increased sensitivity to the fluoroquinolone ciprofloxacin but not to rifampin, while mutants that weaken the CarD/RNAP interaction display a different antibiotic-susceptibility profile. The finding that ciprofloxacin susceptibility is unresponsive to changes in the interaction of CarD with RNAP β1 but is sensitive to CarD protein levels indicates that CarD has a function distinct from binding RNAP. The unique sensitivity of the CarD RID mutants to rifampin treatment further supports the idea that other functional domains exist within CarD that retain activity in the context of the RID mutant but not during CarD protein depletion. In this case, we predict that when CarD binds the RNAP, it counteracts another function of CarD that would make the bacteria more sensitive to rifampin treatment. There are a number of examples in the literature of point mutants that inactivate one function of a protein but do not phenocopy the deletion mutant due to the activity of another functional domain. For instance, one of our groups recently showed that a mutation in the mycobacterial nonhomologous end-joining ligase D (LigD) that inactivates ligase activity does not phenocopy the ΔligD strain, because the scaffolding function of the polymerase domain of LigD is still present (1, 2). We speculate that a similar situation is true for CarD, where point mutations in the RID affect binding to RNAP β1 but leave another function of CarD intact; thus, the point mutant does not mimic CarD depletion.

The mycobacterial CarD RID comprises the 66 N-terminal amino acids of the protein, while the C terminus remains completely uncharacterized. We believe that the C terminus of CarD encodes an important functional domain since we are unable to complement CarD depletion with the M. smegmatis TRCF RID (22), indicating that RNAP binding is not sufficient for CarD activity. Investigations into the function of the CarD C terminus are under way and will hopefully shed light onto the elusive mode of transcriptional regulation by CarD, as well as help reconcile the phenotypic differences between CarD depletion and the disruption of the CarD/RNAP β interaction.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported by a biomedical research grant from the American Lung Association to C.L.S., a Pew Scholars award to B.E.N., and NIH grant AI064693 to M.S.G.

We thank Kathy Frederick and Emil Unanue for generously providing the gp91phox−/− mice and Chirangini Pukhrambam and Grihanjali Devi for assistance with two hybrid experiments.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 17 August 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Akey D, et al. 2006. Crystal structure and nonhomologous end-joining function of the ligase component of Mycobacterium DNA ligase D. J. Biol. Chem. 281: 13412–13423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aniukwu J, Glickman MS, Shuman S. 2008. The pathways and outcomes of mycobacterial NHEJ depend on the structure of the broken DNA ends. Genes Dev. 22: 512–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Campbell EA, et al. 2001. Structural mechanism for rifampicin inhibition of bacterial RNA polymerase. Cell 104: 901–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cole ST. 1996. Rifamycin resistance in mycobacteria. Res. Microbiol. 147: 48–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cooper AM, Segal BH, Frank AA, Holland SM, Orme IM. 2000. Transient loss of resistance to pulmonary tuberculosis in p47(phox−/−) mice. Infect. Immun. 68: 1231–1234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Deaconescu AM, et al. 2006. Structural basis for bacterial transcription-coupled DNA repair. Cell 124: 507–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dove SL, Hochschild A. 2004. A bacterial two-hybrid system based on transcription activation. Methods Mol. Biol. 261: 231–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dove SL, Joung JK, Hochschild A. 1997. Activation of prokaryotic transcription through arbitrary protein-protein contacts. Nature 386: 627–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Feklistov A, et al. 2008. Rifamycins do not function by allosteric modulation of binding of Mg2+ to the RNA polymerase active center. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105: 14820–14825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Garcia-Moreno D, et al. 2010. CdnL, a member of the large CarD-like family of bacterial proteins, is vital for Myxococcus xanthus and differs functionally from the global transcriptional regulator CarD. Nucleic Acids Res. 38: 4586–4598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Houben EN, Nguyen L, Pieters J. 2006. Interaction of pathogenic mycobacteria with the host immune system. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9: 76–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kaufmann SH. 2002. Protection against tuberculosis: cytokines, T cells, and macrophages. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 61(Suppl. 2): ii54–ii58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kourout M, et al. 2009. Molecular characterisation of rifampicin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains from Morocco. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 13: 1440–1442 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Miesel L, Weisbrod TR, Marcinkeviciene JA, Bittman R, Jacobs WR., Jr 1998. NADH dehydrogenase defects confer isoniazid resistance and conditional lethality in Mycobacterium smegmatis. J. Bacteriol. 180: 2459–2467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nickels BE. 2009. Genetic assays to define and characterize protein-protein interactions involved in gene regulation. Methods 47: 53–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ohno H, Koga H, Kohno S, Tashiro T, Hara K. 1996. Relationship between rifampin MICs for and rpoB mutations of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains isolated in Japan. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40: 1053–1056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pashley CA, Parish T. 2003. Efficient switching of mycobacteriophage L5-based integrating plasmids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 229: 211–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pollock JD, et al. 1995. Mouse model of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease, an inherited defect in phagocyte superoxide production. Nat. Genet. 9: 202–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sali A, Blundell TL. 1993. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 234: 779–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Smith AJ, Savery NJ. 2005. RNA polymerase mutants defective in the initiation of transcription-coupled DNA repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 33: 755–764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stallings CL, Glickman MS. 2010. Is Mycobacterium tuberculosis stressed out? A critical assessment of the genetic evidence. Microbes Infect. 12: 1091–1101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stallings CL, et al. 2009. CarD is an essential regulator of rRNA transcription required for Mycobacterium tuberculosis persistence. Cell 138: 146–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thibodeau SA, Fang R, Joung JK. 2004. High-throughput beta-galactosidase assay for bacterial cell-based reporter systems. BioTechniques 36: 410–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Westblade LF, et al. 2010. Structural basis for the bacterial transcription-repair coupling factor/RNA polymerase interaction. Nucleic Acids Res. 38: 8357–8369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. World Health Organization 2006. Actions for life towards a world free of tuberculosis. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- 26. World Health Organization 2010. Global tuberculosis control: a short update to the 2009 report. http://www.who.int/tb/country/en/