Abstract

Pathological cardiac hypertrophy is a key risk factor for heart failure. It is associated with increased interstitial fibrosis, cell death and cardiac dysfunction. The progression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy has long been considered as irreversible. However, recent clinical observations and experimental studies have produced evidence showing the reversal of pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Left ventricle assist devices used in heart failure patients for bridging to transplantation not only improve peripheral circulation but also often cause reverse remodeling of the geometry and recovery of the function of the heart. Dietary supplementation with physiologically relevant levels of copper can reverse pathological cardiac hypertrophy in mice. Angiogenesis is essential and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a constitutive factor for the regression. The action of VEGF is mediated by VEGF receptor-1, whose activation is linked to cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase-1 (PKG-1) signaling pathways, and inhibition of cyclic GMP degradation leads to regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Most of these pathways are regulated by hypoxia-inducible factor. Potential therapeutic targets for promoting the regression include: promotion of angiogenesis, selective enhancement of VEGF receptor-1 signaling pathways, stimulation of PKG-1 pathways, and sustention of hypoxia-inducible factor transcriptional activity. More exciting insights into the regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy are emerging. The time of translating the concept of regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy to clinical practice is coming.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, HIF-1, hypertrophy, LVADs, PKG-1, regression, VEGF, VEGF Receptors

1. Introduction

The simple definition of cardiac hypertrophy is the enlargement of the heart. This enlargement results from the growth of the adult heart in response to an increase in load. Physical exercise and pregnancy can lead to cardiac hypertrophy along with normal or enhanced contractile function (Weeks & McMullen, 2011), which is defined as physiological cardiac hypertrophy and is reversible. In response to chronic pressure or volume overload under certain disease conditions such as hypertension, valvular heart disease, and coronary artery disease, the heart becomes hypertrophic (Opie et al., 2006; Weeks & McMullen, 2011). But this hypertrophy is associated with further development to cardiac dysfunction or heart failure, so that it is defined as pathological cardiac hypertrophy, which has been considered to be irreversible.

The traditional view of the irreversibility of pathological cardiac hypertrophy has recently been challenged. Clinical observation of left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) for bridging to transplantation has shown that some pathological changes in the heart can be reversed after a certain period of LVADs support. In some cases, the pathological cardiac hypertrophy can be reversed and the contractility of the heart can be recovered (Cai et al., 2009; Li et al., 2008; Moens et al., 2008). These observations provide a novel therapeutic option for heart failure patients, namely LVADs therapy for heart failure (Baughman & Jarcho, 2007; Birks et al., 2011; Maybaum et al., 2007; Strueber et al., 2011). Experimental studies have produced strong evidence that shows improvement of angiogenesis in hypertrophic heart can lead to regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy and the prevention of heart failure (Jiang et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2008, 2009a). With regard to this, the role of the trace element copper in the regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) transcriptional activity and the subsequent effects on the expression of genes involved in angiogenesis has become an interesting field of cardiac research (Borkow et al., 2010; Feng et al., 2009; Xie & Kang, 2009; Xie & Collins, 2011). Experimental studies have shown that supplementation with physiologically relevant levels of copper can reverse heart hypertrophy and improve cardiac function in a mouse model of pressure overload-induced pathological cardiac hypertrophy (Jiang et al., 2007).

How does the regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy occur under the aforementioned clinical and experimental conditions? Comprehensive understanding of this novel aspect of cardiac research and medicine has not been available, but recent studies have produced some interesting insights. A critical pathway involving cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)-dependent protein kinase-1 (PKG-1) has been shown to be the major player in the regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy (Takimoto et al., 2005). It has also been extensively demonstrated that vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) plays an essential role in triggering the regression pathway. This pathway is different from that of VEGF-stimulated cardiac hypertrophy in which VEGF is also essential. The regression pathway is mediated by VEGF receptor-1, but the hypertrophic pathway is mediated by VEGF receptor-2. Copper is a critical element in switching the VEGF pathways from VEGF receptor-2-dependent to receptor-1-dependent in the regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy (Zhou et al., 2009a)).

Regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy opens a new avenue of cardiac medicine. Currently clinical approaches basically focus on prevention of cardiac hypertrophy by blocking the hypertrophic signaling pathways. However, in most cases, pathological cardiac hypertrophy is a secondary development derived from primary cardiac diseases such as hypertension, valvular heart disease, and coronary artery disease. Exploring molecular targets that are involved in the regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy would generate alternative and probably more effective remedies for heart failure patients.

In this review, a brief summary of biochemical and functional changes in pathological cardiac hypertrophy will be presented to outline the distinct features of this pathological process. This will be followed by discussion of clinical observations and experimental studies demonstrating the use of LVADs in the regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Then, the discussion will be focused on the role of modulation of angiogenesis in the process of the regression, signaling pathways associated with the promotion of the regression, and identification of potential therapeutic targets to promote the regression. Hopefully, this review will provide a timely understanding of the new direction of cardiac research and medicine.

2. Distinct features of pathological cardiac hypertrophy

The distinction between physiological and pathological cardiac hypertrophy is difficult to define from anatomic features; both types of cardiac hypertrophy can be observed in the form of either concentric or eccentric; the former is characterized by an increase in wall thickness with no change or slight reduction in chamber volume and the latter is an increase in chamber volume with no or small change in wall thickness (Mihl et al., 2008). At the cellular level, concentric hypertrophy results from an increase in myocardial cell width due to a parallel addition of sarcomeres in the cell (Libonati, 2011). Eccentric hypertrophy results from an increase in myocardial cell length due to a series addition of sarcomeres in the cell (Libonati, 2011). Furthermore, increased mitochondrial dynamics in hypertrophic cardiomyocytes is described as an important feature for both types of cardiac hypertrophy. However, there are distinguishable changes between the two types of cardiac hypertrophy. The foremost difference is defined by the functional alteration; physiological hypertrophy is characterized by normal or enhanced cardiac contractile function whereas pathological hypertrophy shows decreased contractility often associated with arrhythmia. The cardiac dysfunction reflects the distinct pathogenesis of pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Experimental approaches have focused on the signaling pathways by which various stimuli can trigger physiological and pathological cardiac hypertrophy. There are many interesting studies and review articles on this topic (Abel & Doenst, 2011; Backs et al., 2009; Heineke et al., 2010; Luo et al., 2012; Suckau et al., 2009; van Berlo et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2012; Zhong et al., 2010), which will not be covered in this review. Some of the key features of physiological versus pathological cardiac hypertrophy are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of pathological cardiac hypertrophy in comparison with physiological cardiac hypertrophy.

| Characteristics | Pathological cardiac hypertrophy |

Physiological cardiac hypertrophy |

|---|---|---|

| Morphological changes | Increase in wall-thickness Increase in organ mass |

Increase in wall-thickness Increase in organ mass |

| Addition of new sarcomeres | Addition of new sarcomeres | |

| Cardiomyocyte dynamics | Apoptosis | - |

| Necrosis Increased efferocytosis |

- - |

|

| Increased autophagy | Increased autophagy | |

| ECM alterations | Increased collagen I deposition |

- |

| Increased collagen III deposition Interstitial fibrosis |

- - |

|

| Increased MMPs | - | |

| Increased TIMPs | - | |

| Myocardial metabolism | Decreased FA oxidation | Increased FA oxidation |

| Increased glucose oxidation | Increased glucose oxidation | |

| Decreased PCr | - | |

| Fetal gene expression | Up-regulation of ANP, BNP, β-MHC, and α–skeletal actin |

- - |

| Genes related to contractility functional alterations |

Down-regulation of SERCA2a, and α-MHC Decreased contractility |

- - Normal or enhanced contractility |

2.1. Interstitial fibrosis in pathological cardiac hypertrophy

The extracellular matrix (ECM), mainly fibrillar collagen, provides structural integrity to adjoining cardiomyocytes. This not only functions as a structural support for the myocardial tissue, but also facilitates myocyte shortening, which translates into efficient cardiac pump function (Baicu et al., 2003; Cleutjens & Creemers, 2002; Pelouch et al., 1993). The proportional distribution or deposition of fibrillar collagen in the heart is critical for cardiac contractile function. One of the unique features of pathological cardiac hypertrophy is increased interstitial fibrosis, or excessive deposition of fibrillar collagen. This excessive collagen deposition is not found in physiological cardiac hypertrophy. Most studies have demonstrated that in the hypertrophic heart of hypertension patients, there is increased diffuse fibrosis in which types I and III collagens are predominant (Brilla & Maisch, 1994; Diez et al., 2001; Gonzalez et al., 2002; Harada et al., 2007). The excessive collagen deposition is related to changes in the activity of fibroblasts under the condition of pathological stimulations.

Fibroblasts synthesize pro-collagen that is secreted into the interstitial space where it is split by pro-collagen N- and C-proteinases (PCP) in the end-terminal pro-peptide sequences to enable collagen fiber formation (Weber, 1997). Myocardial inflammation is an early response to pathological stimulation. Cytokines and chemokines produced under the inflammatory condition further augment the inflammatory effects as well as stimulate counteracting responses. Under the inflammatory condition, cell loss due to apoptosis and necrosis triggers compensatory responses. All of these together significantly increase the activity of fibroblasts, leading to excessive deposition of fibrillar collagens. Many studies have demonstrated the role of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in the initiation and progression of cardiac interstitial fibrosis (Bujak & Frangogiannis, 2007; Khan & Sheppard, 2006; Schultz Jel et al., 2002; Sun et al., 2007). Recent studies have shown microRNAs also participate in the regulation of cardiac fibrogenesis. Myocardial infarction leads to a down-regulation of the miR-29 family microRNAs. The miR-29 family targets mRNAs that encode proteins involved in cardiac fibrosis, including collagen production and deposition, dynamics of fibrillins, and activities of elastin. Therefore, down-regulation of miR-29 relieves the repression of these mRNAs, leading to enhanced cardiac fibrosis (Khan & Sheppard, 2006; van Rooij et al., 2008).

Collagen turnover is mainly regulated by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and the expression of these proteins is significantly up-regulated in pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Although the production of MMPs is increased, the net deposition of fibrillar collagens remains predominant. This is due to the production of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) accompanying the increase in MMPs. These inhibitors function in preventing the degradation of fibrillar collagens by MMPs, ensuring the formation of interstitial fibrosis. Therefore, the ratio of MMPs/TIMPs maintains the equilibrium of collagen deposition and degradation within the myocardium (Cleutjens, 1996).

2.2. Myocardial cell loss in pathological cardiac hypertrophy

Prolonged pressure or volume overload in the setting of cardiovascular disease leads to myocardial cell death in the modes of both apoptosis and necrosis. The myocardial cells that survive the insults become adaptive both in their structure and function. The initial adaptation includes hypertrophy, which is considered to be compensatory in the early phase but transitions to pathological in the constant presence of the insults. In the pathogenesis of pathological cardiac hypertrophy, apoptosis was found to be critically involved (Gottlieb et al., 1994), which has been demonstrated in heart failure patients (Olivetti et al., 1997).

Many in vivo studies have shown that only a very small percentage of myocardial cell populations undergo apoptosis under pathological conditions. For example, less than 0.5% of cells appeared apoptotic in myocardial tissue in the hypertrophic heart of a mouse model (Kang et al., 2000). At first glance, this number seems to be too insignificant to account for myocardial pathogenesis. In a carefully designed time–course study (Kajstura et al., 1996), it was estimated that cardiomyocyte apoptosis is completed in less than 20 hours in rats. Myocytes that undergo apoptosis are lost and may not be replaced under pathological conditions. Although the possibility of myocardial regeneration has been identified (Anversa et al., 2006; Beltrami et al., 2003; Leri et al., 2005; Nadal-Ginard et al., 2003), inhibition of regeneration or degenerative activities often become predominant under myocardial disease conditions (Bicknell et al., 2007; Buja & Vela, 2008).

Myocardial cell death is a critical event in myocardial infarction, which had been considered as a consequence of necrosis (Eliot et al., 1977). It is now recognized that apoptosis contributes significantly to myocardial infarction (Yaoita et al., 2000). Apoptosis and necrosis were originally described as two distinct modes of cell death that can be clearly distinguished (Wyllie, 1994). However, the processes of apoptosis and necrosis are exchangeable. There is a critical control point for a cell to undergo apoptotic pathway. If the apoptotic program is aborted before this control point and the trigger event is severe, cell death may occur by necrosis (Leist et al., 1997). Therefore, the triggering events can be common, but a downstream controller determines the pathway of cell death, which is related to the intensity and duration of insults.

The removal of apoptotic cells is an important process of the cell death program. Efferocytosis is the process by which apoptotic cells are removed by phagocytic cells, which can be regarded as the burying of dead cells (deCathelineau & Henson, 2003). During this process, the cell membrane of phagocytic cells engulfs the apoptotic cell to form a large fluid-filled vesicle containing the dead cell. This vesicle is called an efferosome. Efferocytosis removes dead cells before their membrane integrity is completely lost and the membrane ruptured, so that the contents of apoptotic cells will not leak into the surrounding tissue. This prevents toxic and autoimmune responses due to the exposure to the contents of apoptotic cells (Vandivier et al., 2006). There are “eat me” signals on the membrane of apoptotic cells, such as phosphatidyl serine and calreticulin (Gardai et al., 2005). These signals distinguish apoptotic cells from living cells and guide the process of efferocytosis.

Cell death leads to myocardial cell loss in pathological cardiac hypertrophy. It cannot be excluded that cell death also occurs in physiological cardiac hypertrophy. However, the capacity of myocardial regeneration remains in physiological cardiac hypertrophy so that the replacement of lost myocardial cells may take place. This capacity in pathological cardiac hypertrophy is inhibited and the replacement does not occur.

2.3. Autophagy in pathological cardiac hypertrophy

Autophagy is a “housekeeping” process whereby damaged and dysfunctional cellular organelles and protein aggregates are phagocytosed to produce energy during metabolic stress (Levine & Klionsky, 2004). Autophagy occurs in all eukaryotic cells under starvation, hypoxia, and toxic insults, as well as in response to hormones and developmental signals. There are two forms of autophagy, called selective autophagy and nonselective autophagy. Selective autophagy of mitochondria is termed mitophagy, which is triggered by opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore and loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (Tolkovsky, 2009). In cardiomyocytes, mitophagy is a continuous process of mitochondrial turnover, but the rate of this turnover is influenced by stress and makes a critical contribution to myocardial pathogenesis. Nonselective autophagy has been observed in response to nutrient starvation; the degradation of cytosolic components including mitochondria provides amino acids and lipid substrates for intermediary metabolism (Tolkovsky, 2009).

Autophagy is a highly coordinated process, during which dysfunctional organelles and damaged proteins are encircled in a double-membrane vesicle called autophagosome for the delivery to lysosomes, and the contents are hydrolyzed to produce amino acids, fatty acids, and substrates for ATP generation (Klionsky & Emr, 2000; Z. Xie & Klionsky, 2007; Yoshimori, 2004). Autophagy can be divided into 4 steps: (1) initiation of autophagy in response to triggers; (2) formation of autophagosomes; (3) fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes; and (4) degradation of autophagic contents (Klionsky & Emr, 2000; Xie & Klionsky, 2007). There are multiple proteins involved in the molecular machinery and signaling pathways in autophagy (Shintani & Klionsky, 2004; Wang & Klionsky, 2003). These proteins are found in cardiomyocytes (Gustafsson & Gottlieb, 2009). It has been shown that a basal, constitutive level of autophagy is essential for normal cardiac structural integrity and biological function (Nakai et al., 2007), and up-regulation of autophagy takes place in response to cardiac pressure overload (Halestrap et al., 2004; Paillard et al., 2009) and ischemia-reperfusion (Hamacher-Brady et al., 2006; Kyosola, 1981; Yan et al., 2005).

The up-regulation of autophagy in the setting of cardiac disease conditions is related to (1) nutritional deprivation and depletion of high energy phosphate stores (Inoki et al., 2005); (2) increases in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations (Brady et al., 2007; Hoyer-Hansen et al., 2007; Yitzhaki et al., 2009); (3) generation of reactive oxygen species (Becker et al., 1999; Chen et al., 2007, 2009; Scherz-Shouval et al., 2007a; Scherz-Shouval et al., 2007b; Vanden Hoek et al., 1997; Yang et al., 2008); (4) opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (Brady et al., 2006; Gustafsson & Gottlieb, 2009; Halestrap et al., 2004); and (5) activation of a hypoxia-responsive protein Bnip3 (Bcl-2/adenovirus E1B 19-kilodalton interacting protein) (Kubasiak et al., 2002; Regula et al., 2002). In addition, ER stress, accumulation of damaged or misfolded proteins, and increases in dysfunctional organelles further enhance autophagy (Minamino & Kitakaze, 2010; Qi et al., 2007; Severino et al., 2007; Thuerauf et al., 2006). While these triggers of autophagy in the heart are well documented, the critical issue is whether up-regulation of autophagy is protective or detrimental.

The role of autophagy in cardiac pathogenesis is complex. At present, it is commonly accepted that whether autophagy is beneficial or detrimental depends on the context and amplitude of the induction (Kuma et al., 2004; Yue et al., 2003). For instance, when the cell is starved of energy due to ischemia, activation of autophagy is protective (Gottlieb et al., 2009). However, activation of autophagy during post-ischemic reperfusion is maladaptive (Gottlieb et al., 2009). In the load-stressed heart, activation of autophagy is detrimental (Halestrap et al., 2004). Regardless of being beneficial or detrimental, the increase in autophagy in response to various stresses is a natural process of the heart. However, overt enhancement of autophagy contributes to pathogenesis of pathological cardiac hypertrophy.

2.4. Metabolic disorder in pathological cardiac hypertrophy

ATP is the most important molecule in myocardial metabolism. In the heart, the primary ATP-utilizing reactions are catalyzed by actomyosin ATPase in the myofibril, the Ca2+-ATPase in the SR, and the Na+,K+-ATPase in the sarcolemma (Ingwall & Weiss, 2004). ATP is also needed for molecular synthesis and degradation in the heart as the same as in other organ systems. ATP synthesis by oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondria is usually sufficient to support the normal needs of the heart, even when the work output of the heart increases three- to five-fold (Ingwall & Weiss, 2004). In addition, the glycolytic pathway and the tricarboxylic acid cycle also make small contributions to ATP synthesis. The concentration of ATP does not define the energetic state of the heart. The amount of ATP made and used at any given time is many times greater than the size of the measurable ATP pool (Ingwall & Weiss, 2004). Thus, cardiac myocytes contain high concentrations of mitochondria, which ensure that ATP remains constant through oxidation of a variety of carbon-based fuels for ATP synthesis under different conditions.

A unique feature in energy metabolism of the heart is the use of energy reserve systems, such as phosphocreatine (PCr), to maintain a high phosphorylation potential to drive ATPase reactions under highly demanding conditions (Ingwall et al., 1985). PCr exists in the heart at twice the ATP concentration (Bittl & Ingwall, 1985). The enzyme creatine kinase (CK) transfers the phosphoryl group between ATP and PCr at a rate about 10 times faster than the rate of ATP synthesis by oxidative phosphorylation. The reaction catalyzed by CK is: PCr + ADP + H+ ↔ creatine + ATP. Under the conditions when ATP demand exceeds ATP supply, the use of PCr is a major pathway to maintain a constant supply of ATP. The CK reaction is also important to maintain low ADP and Pi concentrations, thereby retaining high phosphorylation potential (Saupe et al., 2000). Creatine is not made in the heart but accumulates against a large concentration gradient facilitated by a creatine transporter. In the normal heart, about two-thirds of the total creatine pool is phosphorylated through the CK reaction to form PCr (Neubauer et al., 1999; Wallimann et al., 1998).

The continuous synthesis of ATP via mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation is mandatory for the work of the heart (Huss & Kelly, 2005). Under normal conditions, the oxidation of fatty acid (FA) is the major pathway, providing about 70% of the total energy demand. In contrast, the oxidation of glucose provides about 30% of the total energy demand (Shipp, 1961; Wisneski et al., 1987). In physiological cardiac hypertrophy, both FA and glucose oxidation are enhanced. However, in pathological cardiac hypertrophy, there is a metabolic shift from FA- to glucose-dependent energy supply. Thus, decreased FA oxidation and increased glucose utilization in association with depressed FA deposition and increased glucose uptake are observed in pathological hypertrophic and failing hearts (van Bilsen et al., 2004). This shift enhances the glycolytic pathway, and thus increases anaerobic metabolism. It remains uncertain whether this metabolic shift to the so-called “fetal phenotype” is adaptive or maladaptive. It is important to note that the “shift” is only partial, and even when the proportion of ATP synthesized from glucose increases many fold, aerobic metabolism still remains dominant (van Bilsen et al., 2004).

2.5. Fetal gene expression in pathological cardiac hypertrophy

Fetal gene expression in pathological cardiac hypertrophy has been extensively investigated for many years (Park et al., 2011; Sheehy et al., 2009; Tanno et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2004). The most studied and well-characterized fetal genes whose expression is significantly up-regulated in myocardial pathogenesis include atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), and α-skeletal actin (Holtwick et al., 2003; McKie et al., 2010; Stilli et al., 2006). With the increase in the expression of these fetal genes, a simultaneous down-regulation of genes involved in critical function of cardiomyocytes takes place. For instance, the calcium-handling protein sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2A (SERCA2a) is among the depressed proteins found in pathological cardiac hypertrophy (Song et al., 2008). In addition, alterations in cardiac contractile proteins, such as decreased α-myosin heavy chain (α-MHC) and increased β-myosin heavy chain (β-MHC) proteins, are also found in pathological cardiac hypertrophy.

The progression of these distinct biochemical and molecular changes in pathological cardiac hypertrophy discussed above leads to myocardial dysfunction and eventual heart failure. This progression involves myocardial remodeling that has been believed to propagate forwardly, resulting in irreversible pathogenesis. However, recent clinical observations and experimental studies have accumulated evidence showing that reverse remodeling occurs and the pathological cardiac hypertrophy is reversible. In this context, the use of left ventricular assist devices has generated strong evidence as discussed in the next section.

3. Left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) in the regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy

Myocardial remodeling has been a major topic in pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Left ventricular remodeling is the process involving alterations in ventricular size, shape, protein content and composition, and function resulting from the action of mechanical, neurohormonal, and genetic factors (Gao et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2004b; Sedmera et al., 2005). The progression of this remodeling leads to the transition from pathological cardiac hypertrophy to heart failure. Many efforts have been devoted to understand the mechanisms of heart failure. In this context, the hemodynamic model of heart failure explains the effect of an altered load on the failing left ventricle, which results in use of vasodilators and inotropic agents (Berenji et al., 2005; Carroll & Tyagi, 2005; Nishikimi et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2004). The neurohormonal model investigates the importance of the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis and the sympathetic nervous system in the progression of cardiac dysfunction, which leads to the use of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin-receptor antagonists (Pasini et al., 2004; Sethi et al., 2004; Somogyi et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2004) for the treatment of heart failure. Molecular mechanistic understanding of heart failure has recognized an autocrine and paracrine function of the neurohormonal factors (Chatterjee, 2005; Davila et al., 2005; Kamath et al., 2005; Kaye & Esler, 2005; Opgaard & Wang, 2005; Vonder Muhll et al., 2004) dictating an effect on myocardium itself in addition to circulation. The use of left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) has provided alternative insights into regression of heart failure.

3.1. Left ventricular assist devices (LVADs)

End-stage heart failure is currently viewed as an irreversible condition for which current medical therapy offers only temporary symptomatic relief. Patients with end-stage heart failure rely on transplantation to reduce long-term morbidity and to improve survival (Herrington & Tsirka, 2004; Meine & Russell, 2005; Spann & Van Meter, 1998). Due to the limitation of donors and a long waiting list, left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) have been used as a bridge to transplantation (Acker, 2004; Haddad et al., 2005; Kherani & Oz, 2004; Nemeh & Smedira, 2003; Westaby, 2004). This truly novel engineering concept has been further advanced in response to the need for new heart failure therapy. In particular, the HeartMate® (Thoratec Inc) left ventricular assist system (LVAS) has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2002 as a destination therapy for patients ineligible for cardiac transplantation.

Serendipitously, the clinical experience with LVADs has suggested that the use of LVADs not only has become a reliable means of sustaining medically refractory patients with heart failure awaiting cardiac transplantation, but also implicated the potential as a bridge to recovery (Bick et al., 2005; Dandel et al., 2005; Entwistle, 2004; Wohlschlaeger et al., 2005; Zhang & Narula, 2004). An early report in 1994 documented the improvement of cardiac parameters in a transplant candidate living in a hospital with the support of a LVAD (Frazier, 1994). The patient lived for 505 days on LVAD support. Since the first report, numerous case studies have demonstrated a consistent improvement in survival and improved quality of life in patients supported by several different LVADs (Hon & Yacoub, 2003; Massie, 2002; Rose et al., 2001; Salzberg et al., 2003). In a retrospective analysis of a large cohort of patients who were supported by LVADs as a bridge to transplantation, 5% of the patients were weaned successfully so that a transplant was no longer needed (Mancini et al., 1998). This is a surprising discovery because the patients who were selected to receive LVADs support were based on the criteria that define LVADs as a bridge to transplantation, not to recovery. Many studies thus have focused on the phenomenon of LVAD-assisted improvement in cardiac structural and functional parameters. “Reverse remodeling” of the heart with LVAD support has been observed, as described in the following sections.

3.2. Reversal of myocardial hypertrophy by LVAD support

In a study specifically addressing the effect of LVAD support on human left ventricle hypertrophy, Zafeirides et al. (1998) observed that in 6 patients for whom echocardiographs were obtained before and after LVAD support for an average of 75 days, left ventricular mass decreased almost 45% and left ventricular end-diastolic diameter decreased by more than 25%. Other clinical studies using echocardiograph also showed a decrease in left ventricular end-diastolic dimension and left ventricular mass (Heerdt et al., 2000; Ogletree-Hughes et al., 2001). LVADs appear to offer long-term survival with an acceptable quality of life to the LVAD-implanted patients (Frazier et al., 1996). In some LVAD patients who required removal of the device because of device failure, native cardiac function could be improved sufficiently to avoid the second device replacement or transplantation (Zafeiridis et al., 1998). Histopathologic analysis also supported the reversal of cardiac hypertrophy in the LVAD-support patients (Barbone et al., 2001; Dipla et al., 1998).

Studies using isolated cardiac myocytes to evaluate changes in myocyte size, shape, and heterogeneity after sustained LVAD support demonstrated that the average volume of failing human myocytes was nearly twice as large as that observed in nonfailing myocytes. LVAD support caused a 60% reduction in the size of hypertrophied cardiomyocytes, a 62% regression of the increase in average myocyte length, and a decrease in the heterogeneity of myocyte length associated with advanced heart failure (Zafeiridis et al., 1998). This observation was followed by another report demonstrating that the decrease in myocyte size during LVAD support was not observed in the minimally unloaded right ventricle (Barbone et al., 2001). Other studies also showed that long-term LVAD support resulted in a 28% reduction in cardiomyocyte volume, 20% reduction in cell length, 20% reduction in cell width, and 32% reduction in cell length-to-thickness ratio. These cellular changes were associated with reductions in left ventricular dilation and left ventricular mass measured by echocardiograph (Hon & Yacoub, 2003; Salzberg et al., 2003).

There are more studies that provided evidence showing that LVADs induce the reversion of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, a process described as “reverse remodeling” (Popovic et al., 2005). However, there were also studies reporting that the LVAD unloading did not cause cardiomyocyte atrophy, but resulted in increased microvascular density (Massie, 2002). Given that human myocyte hypertrophy is associated with nuclear polyploidization, Rivello et al. examined myocyte diameter, nuclear size and DNA content with static cytomorphometry on tissue sections of the myocardium before and after the implantation of a LVAD, and found that the use of LVADs was associated with a reduction in cardiomyocyte diameter and a marked decline in nuclear DNA content (Ogletree-Hughes et al., 2001).

3.3. Reversal of myocardial contractile dysfunction by LVAD support

Several studies have demonstrated that myocardial contractile function can be significantly improved after a sustained LVAD support. Using isolated cardiomyocytes, Dipla et al. (1998) observed a significant improvement in the fractional shortening and in the rate of shortening and relaxation after 1 to 6 months of LVAD support. Another study using isolated cardiac muscle strips reported a 38% improvement in developed force after LVAD support (Heerdt et al., 2000). The latter study was conducted using a paired tissue analysis in which the muscle strips were obtained from left ventricular apical core before LVAD support and the post-LVAD tissue strips were obtained from the left ventricular free wall. However, there were also studies that demonstrated neither alterations in the developed tension nor changes in contractile parameters under basal conditions after LVAD support, but improved adrenergic responses were observed (Ogletree-Hughes et al., 2001). Several studies also examined the effect of LVAD support on left ventricle contractile function in vivo. One study performed by Frazier et al. showed an improvement of the left ventricle ejection fraction from 11 ± 5% to 22 ± 17% after LVAD support (Frazier et al., 1996). Other studies also demonstrated improved left ventricle ejection fraction after LVAD support (Loebe et al., 1999; Muller et al., 1997).

Impaired calcium handling is an important mechanism for decreased contractility of cardiomyocytes. Thus, several studies have explored the possibility of improvement in myocardial calcium handling after LVAD support. Dipla et al. using isolated myocytes identified changes in the shape of the calcium transient in association with changes in myocyte shortening after LVAD support (Dipla et al., 1998). Other investigators have shown that calcium uptake rate and binding in isolated sarcoplasmic reticulum membranes were improved after LVAD support (Frazier et al., 1996; Heerdt et al., 2000). These results were accompanied by the finding that LVAD support increased mRNA abundance for sarcoplasmic reticulum ATPase, ryanodine receptor, and sodium and calcium exchanger (Nishikimi et al., 2005). These molecules are important for calcium handling and their defects have been recognized in heart failure. Therefore, LVAD-assisted improvement in calcium handling may result from multiple effects on the regulation of expression and function of key proteins.

3.4. Reversal of impaired beta-adrenergic responsiveness by LVAD support

Impaired myocardial adrenergic responsiveness is a characteristic feature of heart failure and is responsible for poor exercise tolerance. While examining the effect of LVAD support on basal contractile function, several studies also investigated the effects of LVAD on myocardial adrenergic responsiveness. Using isolated myocytes, Wisneski et al. showed that LVAD support significantly enhanced the shortening response to isoproterenol stimulation (Wisneski et al., 1987). In the study described above using cardiac muscle strips, Ogletree-Hughes et al. have reported that in response to isoproterenol a marked improvement in peak developed tension, +dP/dt, and −dP/dt, was observed from the LVAD supported failing muscle strips relative to before LVAD support (Ogletree-Hughes et al., 2001). Furthermore, the reversal of impaired adrenergic responsiveness by LVAD support was suggested by the fact that the improved response to isoproterenol observed in the LVAD-supported failing heart muscle strips was essentially the same as that observed in human cardiac trabeculae from non-failing hearts (Ogletree-Hughes et al., 2001).

It has been observed that gradual normalization of the increased circulating epinephrine and norepinephrine levels in heart failure patients takes place during the first 1 to 2 months after the initiation of LVAD support (Loebe et al., 1999; Muller et al., 1997). LVAD support also resulted in normalization of myocardial beta-receptor density in failing human hearts, which was decreased in failing hearts before LVAD support in comparison with non-failing hearts (Ogletree-Hughes et al., 2001). Because these factors are critically involved in the initiation and progression of heart failure, their normalization would make a significant contribution to the reversal of impaired adrenergic responsiveness.

3.5. Reversal of abnormal cardiac electrophysiology by LVAD support

Heart failure is associated with a prolongation of QT interval observed from electrocardiograph, which results from prolongation of the action potential duration of cardiomyocytes. Harding et al. examined electrophysiological alterations after the mechanical circulatory support from LVAD in patients with advanced heart failure (Harding et al., 2001). It was observed that there were two phases of LVAD effects on QT intervals. Cardiac unloading caused an immediate increase in the heart rate-adjusted QT interval despite an immediate decrease in QRS duration. However, there was a secondary decrease in QT interval during sustained LVAD support, which paralleled decreases in the action potential duration measured from isolated human ventricular myocytes. This secondary decrease in QT interval by sustained LVAD support suggests a reversal of the electrophysiological abnormality associated with heart failure.

3.6. Reverse or forward remodeling of myocardial extracellular matrix (ECM)

The results obtained from studies examining the effect of LVAD support on myocardial fibrosis in failing hearts are controversial, ranging from no effect (Kinoshita et al., 1996; Li et al., 2001) to increase in fibrosis (Frazier et al., 1996; Madigan et al., 2001; McCarthy et al., 1995; Scheinin et al., 1992) and to reversal of fibrosis (Bruckner et al., 2001). However, there are critical issues that need to be addressed before these data can be compared. Among these issues are sampling procedures, different measurement techniques, duration of LVAD support, etiology of heart failure, and adjuvant therapies. Bruckner et al. examined paired myocardial samples of 18 patients with end-stage cardiomyopathy obtained at the time of LVAD implantation and removal and found that total collagen content was reduced by 72%, collagen I content decreased by 66% and collagen III content decreased by 62% (Bruckner et al., 2001). In this study, the mean age of patents was 46 ± 3 years (range 24 – 64) and the mean length of LVAD support was 159 ± 25 days (range 18 – 420).

Li et al. reported that after 2 months of LVAD support, myocardial collagen content was unchanged (Li et al., 2001), but the degree of ECM cross-linking was increased in association with decreases in MMP-1 and –9 and increases in TIMP-1 and –3, but no changes in MMP-2 and –3 and TIMP-2 and –4. A time course analysis of LVAD effect on myocardial fibrosis showed that relative collagen content was significantly increased in failing hearts supported with LVAD for more than 40 days (Madigan et al., 2001). Other studies also showed increased myocardial fibrosis after a relative sustained support by LVAD (Barbone et al., 2001; Scheinin et al., 1992).

3.7. Reversal or alteration of signaling pathways and inhibition of apoptosis by LVAD support

Inhibition of myocardial apoptosis is a common observation in the studies of LVAD-assisted regression of cardiomyopathy. There are a few studies that have elucidated signaling transduction pathways that may lead to myocardial phenotype changes, including inhibition of apoptosis in failing hearts supported by LVAD. In this context, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways have been studied (Bartling et al., 1999; Flesch et al., 2001). Flesch et al. showed that LVAD support significantly reduced the activity of p44/42 and JNK1/2 but significantly increased p38 activity. These differential changes in MAPKs were associated with significant reductions in cardiac myocyte size and myocyte apoptosis after LVAD support relative to non-LVAD support (Flesch et al., 2001). Bartling et al. showed that the activity of ERK and Akt in failing hearts dramatically decreased after LVAD support, but GSK-3 increased. At the same time, cardiac myocyte apoptosis and myocyte size also significantly decreased after LVAD support (Bartling et al., 1999). However, the link between the changes in the kinase activities and the reductions in myocyte size and apoptosis remains elusive.

3.8. LVADs as a bridge to recovery in heart failure patients

Based upon the studies described above, many efforts have focused on the demonstration of using LVADs for the treatment of end-stage heart failure as a “bridge to recovery” (Boyle et al., 2011; Smedira et al., 2010). Furthermore, long-term circulatory support “destination therapy” has become an increasingly realistic alternative to cardiac transplantation for most of the heart failure patients who are ineligible for transplantation because of associated co-morbidity (Pamboukian et al., 2011). Because the mechanical unloading by LVADs can decrease oxygen consumption and reduce excess load of the left ventricle in heart failure (Baughman & Jarcho, 2007; Blume et al., 2006; Klotz et al., 2008), the use of LVADs improves survival (Kugler et al., 2011; Radovancevic et al., 2007) and cardiac function (Kukucka et al., 2011) for some of the patients who were thought to have irreversible heart failure. While the “destination therapy” is available to more heart failure patients, the bridge to recovery by LVADs is an attractive concept in cardiac medicine.

Reversal of pathological cardiac hypertrophy is associated with improvement in coronary circulation. Recent studies have demonstrated that while cardiac hypertrophic growth is angiogenesis-dependent, regression of cardiac hypertrophy also relies on angiogenesis. The next section will specifically discuss angiogenesis in the regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy.

4. Angiogenesis and regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy

It is widely recognized that cardiac hypertrophy is accompanied by the change of coronary angiogenesis. Physiological cardiac hypertrophy is associated with normal or increased density of myocardial capillaries (Hudlicka et al., 1992). Pathological hypertrophy is accompanied by enhanced coronary angiogenesis at the initial stage of cardiac hypertrophy (Huo et al., 2007; Kassab et al., 1993, 2000). However, the capillary density obviously decreases in the late phase of pathological cardiac hypertrophy (Anversa et al., 1986; Flanagan et al., 1991; Hamasaki et al., 2000; Hudlicka et al., 1992; Karch et al., 2005; Shimamatsu & Toshima, 1987). Reduced coronary reserve, defined as the difference between basal flow and maximal flow during infusion of agents such as adenosine, occurs in pathological cardiac hypertrophy (Shimamatsu & Toshima, 1987). Hypertension with left ventricular hypertrophy is associated with both coronary vascular remodeling and attenuated endothelial and non-endothelial coronary flow reserve (Hamasaki et al., 2000).

Inhibition of angiogenesis by suppressing the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling pathway can completely block the enlargement of the heart under hypertrophic stimulation in animal models (Higashikuni et al., 2011; Jiang et al., 2007; Makino et al., 2009; Shiojima et al., 2005). While angiogenesis is essential for the enlargement of the heart, it is quite interesting that the regression of cardiac hypertrophy is also angiogenesis-dependent (Jiang et al., 2007), and VEGF is required for the reduction in the size of hypertrophic cardiomyocytes (Zhou et al., 2008, 2009a; Zuo et al., 2010).

4.1. Disrupted coordination between angiogenesis and cardiac hypertrophy in heart failure

The match of the increase in the density of myocardial capillaries to the hypertrophic growth of the heart muscle is critical to keep cardiac function normal or ensure the functional adaptation to the increase in cardiac load. A study using a conditional transgenic mouse model in which Akt1 gene expression can be specifically activated in the heart showed that Akt activation led to cardiomyocyte hypertrophy (Taniyama et al., 2005). In this system, both physiological and pathological cardiac hypertrophy could be developed through a sequential manner of induction of Akt1 gene expression. Physiological cardiac hypertrophy was induced by a short-term Akt activation and displayed preserved contractile function with enhanced coronary angiogenesis. However, a long-term activation of Akt in the same mouse model resulted in pathological cardiac hypertrophy with reduced contractility and impaired coronary angiogenesis (Taniyama et al., 2005). Therefore, the coordination between coronary angiogenesis and the enlargement of the heart ensures that the hypertrophy is physiological and disruption of this coordination results in the pathogenesis of pathological cardiac hypertrophy and its transition to heart failure.

In the conditional Akt1 transgenic system in mice, coronary angiogenesis is related to mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-dependent expression of VEGF-A and angiopoietin-1 (Taniyama et al., 2005). Detailed analysis has revealed that under physiological hypertrophic conditions, the expression of VEGF-A and angiopoietin-1 is up-regulated and under pathological hypertrophy, the expression of these genes is down-regulated (Taniyama et al., 2005). However, even in the acute induction of Akt expression, which led to physiological cardiac hypertrophy, the inhibition of coronary angiogenesis by a VEGF decoy receptor switched the development of physiological cardiac hypertrophy to the pathogenesis of heart failure, characterized by reduced capillary density along with contractile dysfunction and impaired cardiac growth. Thus, VEGF signaling plays a critical role in coronary angiogenesis, which in turn is essential in the sustention of normal cardiac function under hypertrophic stimulation.

4.2. Angiogenesis is essential for regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy

Promotion of coronary angiogenesis can lead to reversal of pathological cardiac hypertrophy. In a mouse model of pathological cardiac hypertrophy induced by pressure overload through ascending aortic constriction it was found that the density of myocardial capillaries significantly decreased (Jiang et al., 2007). The decrease in capillary density was associated with suppression of VEGF and a concomitant decrease in the concentration of myocardial copper (Jiang et al., 2007). The expression of VEGF is regulated by hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) and copper is essential for VEGF gene expression because copper is required for HIF-1 transcriptional activity (Feng et al., 2009; Jiang et al., 2007). Importantly, dietary copper supplementation promoted VEGF production and relieved the suppression of coronary angiogenesis leading to regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Moreover, anti-VEGF antibody completely blunted the copper-induced coronary angiogenesis and the subsequent regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy (Jiang et al., 2007).

In another mouse model of pressure overload-induced pathological cardiac hypertrophy, Takimoto et al. showed that chronic inhibition of cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase 5A (PDE5A) by sildenafil (Viagra) reversed the pre-established pathological cardiac hypertrophy induced by transverse aortic constriction (Takimoto et al., 2005). It was found that the inhibition of PDE5A deactivated multiple hypertrophic signaling pathways triggered by pressure overload, including the calcineurin/NFAT, phosphoinositide-3 kinase/Akt, and ERK1/2 signaling pathway (Takimoto et al., 2005). The inhibition of the hypertrophic signaling pathways would make perfect sense for the inhibition of progression of cardiac hypertrophy, for which it had been shown that PDE5A inhibition indeed prevented pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy (Takimoto et al., 2005). How does PDE5A inhibition relate to regression of cardiac hypertrophy? Subsequent analyses showed that PDE5A inhibition stimulates VEGF and angiopoietin-1 production and promotes coronary angiogenesis (Koneru et al., 2008; Vidavalur et al., 2006). In addition, PDE5A inhibition also activates the cGMP-dependent protein kinase-1 (PKG-1) signaling pathway in cardiomyocytes (Zhang et al., 2010), which will be discussed in next section. Acting together, these effects result in the regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy.

4.3. Pharmaceutical agents affecting myocardial angiogenesis

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are pharmaceutical drugs primarily used for the treatment of hypertension and congestive heart failure. Frequently prescribed ACE inhibitors include captopril, enalapril, lisinopril, and ramipril. ACE inhibitors have been shown to be effective for not only patients with hypertension, but also patients with normal blood pressure. Use of a maximum dose of ACE inhibitors for prevention of diabetic nephropathy, congestive heart failure, and prophylaxis of cardiovascular events is justified because it improves clinical outcomes, independent of the blood pressure-lowering effect of ACE inhibitors. Several studies have demonstrated that ACE inhibitors can attenuate the progression of cardiac hypertrophy in experimental models of heart failure by affecting the coronary capillary density and function (Chiba et al., 1994; Ruzicka et al., 1995; Weinberg et al., 1994).

Dipyridamole is a drug that inhibits thrombus formation when given chronically and causes vasodilation when given at high doses over a short period of time. Treatment with dipyridamole has been shown to increase endomyocardial capillary density in cardiac hypertrophy (Torry et al., 1992). It increases myocardial perfusion and left ventricular function in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy.

NO can modify the structure of vascular tissues by inhibiting the growth of vascular smooth muscle cells. There is an increase in the basal activity of NO (without a significant change in endothelial NO synthase expression) in early compensated left ventricular hypertrophy, followed by a decrease in both endothelial NO synthase expression and NO bioactivity during the transition to heart failure (Grieve et al., 2001). Releasing NO by bradykinin-NO pathway can inhibit the progression of cardiac hypertrophy (Balligand et al., 1993; Brady et al., 1993; Ishigai et al., 1997). These preventing effects on cardiac hypertrophy and on the transition to heart failure are all due to the promotion by NO of myocardial angiogenesis (Janssens et al., 2004; Murohara et al., 1998).

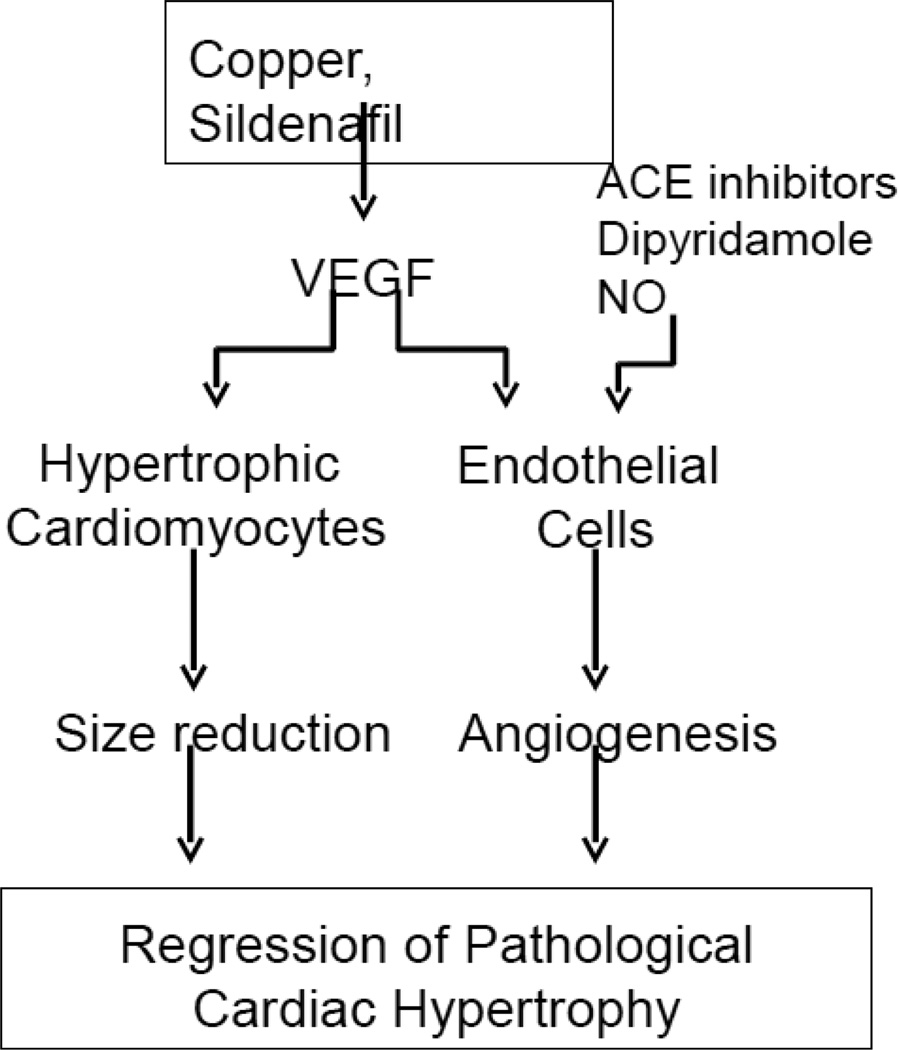

While the essentiality of myocardial angiogenesis has been sufficiently demonstrated, the molecular event leading to reversal of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy is another important topic. Angiogenesis improves the microenvironment of hypertrophic cardiomyocytes, the regression of myocyte hypertrophy is the process occurring inside of the cells. However, both angiogenesis and reversal of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy are VEGF-dependent, as elucidated in Figure 1. The understanding of signaling pathways existing in cardiomyocytes and involved in the reversal of myocyte hypertrophy, independent of signaling pathways leading to angiogenesis, is important for the development of pharmaceutical agents in the regression of cardiac hypertrophy.

Figure 1. VEGF-dependent angiogenesis and reversal of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy.

Both copper and sildenafil cause up-regulation of VEGF expression, which is also affected by ACE inhibitors, dipyridamole, and NO. There are VEGF receptors on both endothelial cells and cardiac myocytes. Activation of the endothelial cells leads to angiogenesis and the response of hypertrophic cardiomyocytes to VEGF results in reduction in cell size, all together promoting the regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy.

5. Signaling pathways leading to regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy

The signaling pathways involved in cardiac hypertrophy have been extensively studied and some of the molecules involved in the critical pathways have been the targets of pharmaceutical development (Belmonte & Blaxall, 2011; Care et al., 2007; Gaspar-Pereira et al., 2011; McKinsey & Kass, 2007; Wang et al., 2010; Zhang & Mende, 2011). However, the signaling pathways involved in the regression of cardiac hypertrophy are a relatively new field of study to which investigation has just begun. There are several exciting clues and experimentally-tested signaling molecules that have been identified in the regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Among these are the VEGF-VEGF receptor-1 signaling pathway, activation of PKG-1 pathway, and regulation of HIF-1 transcriptional activity. This review will cover only the current mainstays of the experimentally-tested signaling pathways, although there are other molecules that are also suggested to function in the regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy. It should be noted that these currently, extensively studied signaling pathways are still far from being comprehensively understood. There are many missing components that need to be identified for the full elucidation of the signaling pathways.

5.1. VEGF-VEGF receptor-1 signaling pathway

VEGF triggers cellular responses through its receptors on the cell membrane. Binding of VEGF promotes the receptors to dimerize and be activated through autophosphorylation, leading to signaling transduction cascades (Hoeben et al., 2004). There are three VEGF receptors (VEGFRs) and each receptor functions differently and coordinately with each other. VEGFR-2 is a dominant component in VEGF-triggered cell growth and differentiation signaling pathways. Activation of VEGFR-2 by VEGF in cells devoid of VEGFR-1 results in a mitogenic response, while the activation of VEGFR-1 in cells lacking VEGFR-2 does not induce cell proliferation (Kliche & Waltenberger, 2001; Nishi et al., 2008; Roberts et al., 2004). VEGFR-2 activates mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway whereas VEGFR-1 cannot activate this pathway (Haddad et al., 2005). Extensive studies performed in endothelial cells suggest that VEGFR-2 mediates most of the known cellular responses to VEGF such as embryonic vasculogenesis and tumor angiogenesis (Sakurai et al., 2005; Takahashi, 2011; Yang & Cepko, 1996). It is traditionally believed that VEGFR-1 regulates VEGFR-2 signaling, either negatively or positively (Clark et al., 1998; Zeng et al., 2001).

VEGF also stimulates cell growth in myocardial tissue (Sano et al., 2007; Shimojo et al., 2007; Shyu et al., 2005; Song et al., 2007; Zisa et al., 2009). A VEGFR-2 antagonist blocks cardiac growth induced by Akt1 activation (Izumiya et al., 2006; Shiojima et al., 2005), indicating a link between the VEGFR-2 and the Akt1 signaling pathway. However, in the hypertrophic myocardium or hypertrophic cardiomyocytes in cultures, VEGF causes regression of hypertrophy (Jiang et al., 2007; Shiojima et al., 2005; Zhou et al., 2008). This suggests that VEGF has a dual function in cardiomyocytes; stimulating cell growth under physiological or stress conditions and reducing the size of cardiomyocytes under hypertrophic conditions.

Expression of the dual function of VEGF needs to be mediated by VEGFRs. The link of VEGFR-2 to the growth stimulation pathway suggests that other receptors would link to the regression pathway. It has been shown that an increase in the ratio of VEGFR-1 to VEGFR-2 in the regression of hypertrophy occurs in cultured cardiomyocytes (Zhou et al., 2009). The cause-effect relationship between the increase in the ratio of VEGFR-1 to VEGFR-2 and the reversal of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy has been demonstrated using siRNA targeting of VEGFR-2 to elevate the ratio of VEGFR-1 to VEGFR-2. This increase in the ratio of VEGFR-1 to VEGFR-2 in hypertrophic cardiomyocytes led to the regression of the hypertrophy (Zhou et al., 2009). This regression was blocked when anti-VEGF antibody was applied to the cells. Furthermore, gene silencing of VEGFR-1 blocked the reversal of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, further demonstrating the role of VEGF-VEGFR-1 signaling pathway in the regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy.

VEGFR-1 is associated with PKG-1 activation. The link of VEGFR-1 to the PKG-1 pathway in the regression of heart hypertrophy has been demonstrated in hypertrophic cardiomyocytes (Zhou et al., 2009). The PKG-1 signaling pathway is the most studied and critically important pathway in the regression of heart hypertrophy, as will be discussed in next section. It was observed that the suppression of VEGFR-1 reduced the activity of PKG-1, indicating the activation of PKG-1 is at least in part VEGFR-1 dependent (Zhou et al., 2009). Conversely, a PKG-1 inhibitor, 8-(4-chlorophenylthio)guanosine-3’,5’-cyclic monophosphorothioate, Rp-isomer (Rp-8-pCPT-cGMPS) effectively blocked the reversal of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy induced by the increase in the ratio of VEGFR-1 to VEGFR-2. Therefore, the down-stream players of VEGFR-1 signaling pathway involve PKG-1 in hypertrophic cardiomyocytes. However, it is unknown how VEGFR-1 and PKG-1 interact to ignite this signaling transduction.

The aforementioned inhibition of PDE5A by sildenafil leading to regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy is related to VEGF up-regulation. In a rat model of myocardial ischemia and reperfusion, it was observed that treatment with sildenafil before occlusion of the left anterior descending artery (ischemia) followed by reperfusion significantly increased capillary and arteriolar density along with increased blood flow. The improvement in angiogenesis was accompanied by the increase in gene expression of VEGF and angiopoietin-1. These changes resulted in a significant reduction in myocardial infarct size, and reduced apoptosis of cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells. These changes were also associated with a significant improvement in cardiac function including an increase in fractional shortening and ejection fraction, and increased contractile reserve (Koneru et al., 2008). Therefore, it was concluded that up-regulation of VEGF and angiopoietin-1 by sildenafil most likely stimulates a cascade of events leading to neovascularization and conferring myocardial protection against injuries by ischemia and reperfusion, although further insights into mechanisms by which sildenafil activates these pathways need to obtained.

Pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy in a mouse model is associated with a loss of myocardial copper concentrations. Dietary supplementation with physiologically relevant levels of copper not only replenishes cardiac copper levels but also reverses cardiac hypertrophy. In searching for potential mechanisms leading to copper repletion-induced regression of cardiac hypertrophy, it was found that copper deficiency suppressed the expression of VEGF in the heart and copper repletion restored VEGF expression (Jiang et al., 2007). The increased VEGF expression was accompanied by increased myocardial capillary density. It was also found that administration of anti-VEGF completely blocked copper supplementation-enhanced angiogenesis and suppressed the reversal of cardiac hypertrophy. Therefore, it was concluded that recovery of VEGF expression and the subsequent angiogenesis contribute to copper supplementation-induced regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Further analysis revealed that copper functions in switching the VEGFR2-dependent to the VEGFR1-dependent signaling pathway in the hypertrophic cardiomyocytes (Zhou et al., 2009).

5.2. Activation of PKG-1 pathway

It has been known that activation of PKG-1 leads to inhibition of myocardial growth (Fiedler et al., 2002; Wollert et al., 2002), and further studies have determined that PKG-1 is involved in the regression of cardiac hypertrophy (Takimoto et al., 2005). Activation of PKG-1 has been observed in pressure overload-induced heart hypertrophy (Takimoto et al., 2005). In a mouse model of cardiac pressure overload induced by transverse aorta constriction (TAC), heart hypertrophy was observed after TAC for 3 weeks. PKG-1 activity was significantly elevated in the hypertrophic myocardium (Takimoto et al., 2005). This activation was considered as a counteracting action to heart hypertrophy induced by pressure overload. However, the PKG-1 activation was not sufficient to prevent the development of heart hypertrophy (Takimoto et al., 2005). However, treatment with an oral PDE5A inhibitor, sildenafil, blocked the intrinsic catabolism of cGMP leading to sustained activation of PKG-1 with an accompanying regression of heart hypertrophy.

In the study using cardiomyocytes in cultures (Zhou et al., 2009), it has been demonstrated that phenylepherine (PE) increased the size of cardiomyocytes, which was associated with enhanced PKG-1 activity. Addition of copper reduced the size of hypertrophic cardiomyocytes. Copper did not affect PE-induced activation of PKG-1. However, copper inhibited VEGFR-2, which is linked to the Akt-1 signaling pathway. The inhibition of VEGFR-2 was associated with the increase in the ratio of VEGFR-1 to VEGFR-2, thus activating PKG-1 due to the link between VEGFR-1 and PKG-1. Therefore, under the VEGFR-1-PKG-1 dominant condition, the signaling pathway switches from VEGFR-2 mediated hypertrophic stimulation to regression of cardiac hypertrophy, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. VEGFR1-dependent regression pathways in hypertrophic cardiomyocytes.

GPCRs (guanine nucleotide binding-protein coupled receptors) recognize a variety of ligands and stimuli causing cardiac hypertrophy. These receptors affect the generation of small molecules that act as intracellular mediators or second messengers leading to hypertrophic signaling cascades. Among these pathways is the activation of Gq (G-protein subunit q), leading to activation of its downstream signaling transductions. Ca2+-dependent signaling pathways are critically involved in cardiac hypertrophy, including calcineurin/nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), calmodulin-dependent kinases (CaMK) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways. VEGF binding to VEGFR1 leads to PKG-1 activation, which in turn activates regulator of G-protein signaling 2 (RGS2) that inhibits Gq, and phosphorylates vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) that suppresses Ca2+ signaling pathways. PKG-1 also inhibits L-type calcium channels and transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily 95 C, member 6 (TRPC6). These are counteractions against GPCR-mediated hypertrophic responses. Atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) binds to natriuretic peptide receptors (NPRs), also called guanylyl cyclases (GCs), to convert GTP to cGMP and activate PKG-1. Inside the cells, L-arginine is converted to NO by endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), which in turn activates soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) and increases the levels of cGMP. Sildenafil inhibits phosphodiesterase type 5A (PDE5A) to block the conversion from cGMP to GMP, leading to sustained accumulation of cGMP and activation of PKG-1.

The link between VEGFR-1 and PKG-1 is a recent finding in the PKG-1 signaling pathway field. Factors upstream of PKG-1 activation have long been known to be related to natriuretic peptides (Kotera et al., 2003). For instance, cardiac atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) binds to the transmembrane guanylyl cyclase (GC) receptor, GC-A, to exert its diverse functions, including regulating arterial blood pressure, modulating cardiomyocyte growth, and stimulating angiogenesis. The GC-A receptor is coupled to the c-GMP-dependent or PKG-1 signaling pathway, preventing pathological increases in intracellular Ca2+ and counteracting the hypertrophic signaling pathway. However, in chronic cardiac hypertrophy, ANP levels are markedly increased and the GC-A receptor is desensitized, leading to blunted responsiveness of the cGMP-dependent signaling pathway (Kotera et al., 2003). The newly-identified link between VEGFR-1 and PKG-1 would thus reactivate the cGMP-dependent signaling pathway, compensating for the desensitized effect of GC-A receptor.

How does PKG-1 activation lead to regression of cardiac hypertrophy? There are several downstream pathways that are linked to PKG-1, including both positive and negative regulators. PKG-1 is a crucial component in the NO-dependent signaling pathway, in which NO activates sGC leading to the release of cGMP and the activation of PKG-1. In general, PKG-1 causes down-regulation of hypertrophic pathways through its interactions with some critical molecules.

The transient receptor potential canonical (TRPC) 6 is a receptor-operated Ca2+ channel known to positively regulate the signaling pathway of calcineurin-nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), which plays a pivotal role in cardiac hypertrophy. TRPC6 expression increased in the heart of mice subjected to pressure overload, and in neonatal and adult rat cardiomyocytes treated with angiotensin II or endothelin-1 (Koitabashi et al., 2010). A study using cardiac myocytes showed that the activation of PKG-1 by ANP induced phosphorylation of TRPC6 at threonine 69, leading to a significant inhibition of agonist-evoked NFAT activation and Ca2+ influx, and attenuation of cardiac hypertrophy (Kinoshita et al., 2010). These inhibitory effects were abolished by specific PKG-1 inhibitors or by substituting an alanine for threonine 69 in TRPC6. When the activation of PKG-1 was blocked by the ANP receptor GC-A deletion, the calcineurin-NFAT pathway was constitutively activated. A selective TRPC channel blocker, BTP2 (N-{4-[3,5-bis(Trifluoromethyl)-1H-pyrazol-1-yl]phenyl}-4-methyl-1,2,3-thiadiazole-5-carboxamide), significantly attenuated agonist-induced cardiac hypertrophy (Kinoshita et al., 2010). Therefore, it was concluded that TRPC6 is a critical target for PKG-1 activation, and its blockade contributes to the regression of cardiac hypertrophy.

Vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) is a molecule that is suggested to be involved in the regulation of cardiac hypertrophy. Pressure overload induced by ascending aortic constriction in mice resulted in a significant increase in the expression and phosphorylation of VASP. The beta-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol activates the cAMP-dependent signaling pathway and promotes the rapid and reversible phosphorylation of VASP at Ser157 and Ser239. The inhibition of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase blocked the phosphorylation of VASP (Sartoretto et al., 2009). The cAMP-dependent phosphorylation of VASP is associated with increases in intracellular Ca2+ and cardiac hypertrophy. However, the activation of the cGMP-dependent signaling pathway by ANP leads to phosphorylation of VASP only at Ser239 (Sartoretto et al., 2009). This phosphorylation is associated with attenuated cellular Ca2+ entry, and altered growth and proliferation (O'Neil, 2007). Therefore, VASP as a target of PKG-1 plays an alternative role in the regulation of cardiac hypertrophy, whereas it promotes cardiac hypertrophy when activated by the cAMP-dependent signaling pathway.

The regulator of G-protein signaling 2 (RGS2) is a target of PKG-1. PKG-1 binds to, phosphorylates, and activates RGS2, which in turn disrupts the activation of intracellular calcium signaling via its inhibitory effect on Gq-coupled signaling pathway (Tang et al., 2003). PKG-1, through this calcium signaling inhibitory effect, causes multiple suppressive actions on calcium-dependent regulatory proteins, such as the L-type calcium channel, the ryanodine receptor calcium release channel, and troponin I (Saucerman & McCulloch, 2004). In addition, PKG-1 also directly interacts with several calcium-dependent regulatory proteins (Gray et al., 1999).

5.3. Regulation of HIF-1 transcriptional activity

HIF-1 plays a critical role in the regulation of cellular metabolism, homeostasis, and responses to stresses (Hirsila et al., 2005; Maxwell & Salnikow, 2004; Semenza, 2000). Therefore, the regulation of HIF-1 transcriptional activity has been a major focus in understanding the fundamental process of HIF-1 activation and its therapeutic significance. HIF-1 is composed of HIF-1α and HIF-1β or ARNT (aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator). The cellular stability of HIF-1α determines the ultimate activation of HIF-1. The expression level of HIF-1α is undetectable in most cell types under normoxic conditions due to its degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. In this process, one or both of the two conserved proline residues (Pro402 and Pro564) in HIF-1α is recognized by members of the prolyl hydroxylase domain-containing proteins (PHDs), which catalyze the reaction of proline hydroxylation (Huang et al., 1998; Ivan et al., 2001; Jaakkola et al., 2001). The hydroxylated HIF-1α is recognized by the von Hippel-Lindau protein (pVHL), which is a constituent of a ubiquitin ligase complex, targeting the HIF-1α subunit for degradation by the proteasome in the cytoplasm (Masson et al., 2001; Maxwell et al., 1999; Ohh et al., 2000; Tanimoto et al., 2000). Under hypoxic conditions, HIF-1α escapes from the degradation pathway, accumulates in the cytoplasm, and translocates to the nucleus, where it dimerizes with HIF-1β and interacts with cofactors to assemble the HIF-1 transcriptional complex, leading to transcriptional activation.

Several transition metals are capable of increasing the accumulation of HIF-1α in the cell. For instance, cobalt inhibits PHDs (Hirsila et al., 2005; Ke et al., 2005; Maxwell & Salnikow, 2004; Yuan et al., 2003), leading to the stabilization of HIF-1α and its accumulation in the cell. Other metals, such as nickel and copper, share the same inhibitory action on PHDs with cobalt (Hirsila et al., 2005; Ke et al., 2005; Martin et al., 2005; Maxwell & Salnikow, 2004; van Heerden et al., 2004; Yuan et al., 2003). However, recent study has demonstrated that copper is required for HIF-1 transcriptional activity under hypoxic conditions besides its inhibitory action on PHDs (Feng et al., 2009).

The mechanism of action of copper on HIF-1 transcriptional activity involves its role in the interaction between HIF-1 and the hypoxia-responsive element (HRE) sequence of target genes and the formation of the HIF-1 transcriptional complex (Feng et al., 2009). Because these processes take place in the nucleus, copper has to be transported into the nucleus to effect activation of the transcriptional activity of HIF-1. The copper chaperone for Cu, Zn-SOD (CCS) most likely functions as a copper chaperone for its nuclear translocation. It has been shown that gene silencing of CCS inhibited HIF-1 transcriptional activity under hypoxic conditions (Feng et al., 2009). The inhibitory effect of CCS deletion on HIF-1 transcriptional activity cannot be relieved by excess copper, although the inhibitory effect of copper restriction by copper chelation on HIF-1 transcriptional activity can be reversed by excess copper (Feng et al., 2009), indicating that CCS is essential in this action.

The most important relevance of copper regulation of HIF-1 transcriptional activity in the regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy is that during the pathogenesis of cardiac hypertrophy, copper levels in the heart significantly decrease (Jiang et al., 2007). Under ischemic or hypoxic conditions, HIF-1α is accumulated in the heart, which has been observed in biopsy tissue samples of patients and in animal models (Kakinuma et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2000). However, it has been known that long-term ischemia or hypoxia leads to inhibition of VEGF expression and suppression of angiogenesis (Wang et al., 2010). It is thus interesting to know why the increased HIF-1α levels are associated with decreased expression of genes regulated by HIF-1 in the ischemic or hypertrophic heart. The loss of copper in ischemic or hypertrophic heart leading to suppression of HIF-1 transcriptional activity provides at least a partial explanation (He & Kang, 2012).

The association of copper deficiency with ischemic heart disease and cardiac hypertrophy has been recognized for a long time (Davydenko et al., 1995; Klevay, 1989; Shliakhover et al., 1990), but its clinical significance has not been fully explored. An early study using hearts from people who died from ischemic heart disease showed that copper concentrations were decreased in the uninjured tissues of the infarcted hearts relative to normal heart tissues (Wester, 1965). Another study showed that copper concentrations decreased in the hearts of people who died from acute ischemic infarction (Zama & Towns, 1986). The death rate from ischemic heart disease in soft water areas was found to be increased and copper concentrations were lower in the hearts of people who died from chronic ischemic heart disease (Anderson et al., 1975; Chipperfield & Chipperfield, 1978). Copper deficiency leads to congestive heart failure (Elsherif et al., 2003). The most important aspect of copper deficiency-induced cardiac hypertrophy is that upon copper repletion through dietary supplementation, the pre-established cardiac hypertrophy can be reversed (Elsherif et al., 2004a, 2004b; Zhou et al., 2009b). A study in a small population of chronic heart failure patients showed that dietary supplementation with micronutrients for 9 months increases left ventricle ejection and decreases left ventricle volume along with improvement of quality of life (Witte et al., 2005). Copper (1.2 mg/day) was among the formulated micronutrients in that study.

Further studies have shown that pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy is also reversible by dietary copper supplementation. In a mouse model of pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction, it has been found that pressure overload is associated with copper loss in the heart (Jiang et al., 2007). Dietary supplementation with physiologically relevant levels of copper replenishes cardiac copper levels and reverses cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction even in the presence of chronic pressure overload. The cardiac effect of dietary copper supplementation is associated with recovery of normal VEGF expression and enhanced angiogenesis. In the presence of anti-VEGF antibody, dietary copper supplementation failed to reverse the pre-established heart hypertrophy and dysfunction. As discussed above, this effect results from copper activation of HIF-1 transcriptional activity (Feng et al., 2009). It is important to note that VEGF and VEGFR-1 are regulated by HIF-1, and VEGFR-2 is not. This would provide another explanation for copper-induced switching from VEGFR-2-dependent to VEGFR-1-dependent signaling pathways.

These signaling pathways and transcriptional regulation of critical molecules involved in regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy discussed above become important targets for therapeutic intervention. Understanding these targets will provide insightful suggestions for the consideration for pharmaceutical development.

6. Potential therapeutic targets for promoting regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy

Regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy is a relatively new concept. Clinical and experimental observations have noted the regression phenomenon, but the significance has not been fully appreciated. There are multiple obstacles that need to be overcome in order to make the regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy a realistic medical approach: (1) It is still a mainstay belief that pathological cardiac hypertrophy is not reversible, although there is accumulating evidence that shows it is possible. (2) Experimental approaches to understand the mechanisms by which regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy occur must focus on blocking the pathogenesis pathways leading to cardiac hypertrophy. This approach would help develop interventions to inhibit the progression, but would hardly provide critical insights into the regression because the regression would not be a simple reversal of the forward process. (3) Experimental models focusing on regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy, not prevention of cardiac hypertrophy, are not appreciably available. Making such experimental models is timeand effort-consuming, which add more difficulties to the existing complexity. (4) Pharmaceutical approaches take time to be established and a long-term vision needs to be created in order to guide drug development.

There are some clues that implicate potential therapeutic targets that would play important roles in the regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy. It again needs to be pointed out that this journey is at its beginning and validation of any of these targets has not been done.

6.1. Promotion of myocardial angiogenesis