Abstract

The purpose of this article is to illustrate the imaging findings of lesions that present as cyst with a mural nodule tumor (CMNT). CMNT is a subtype pattern of intra-axial enhancement in central nervous system tumors, typical of a variety of brain neoplasms, including, as the most common, hemangioblastoma, pilocytic astrocytoma, ganglioglioma and pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma and as less common tanycytic ependymoma, intraparenchymal schwannoma, desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma and cystic metastasis. A retrospective design was chosen given the rarity of CMNT. Relevant cases were obtained retrospectively to review the different lesions that can present with the appearance of CMNT.

Keywords: Brain tumor, cyst, hemangioblastoma, pilocytic astrocytoma, ganglioglioma, pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma

Introduction

Cyst with a mural nodule tumor (CMNT) is one of the radiologic patterns of central nervous system (CNS) tumors. In a classification of the patterns of contrast enhancement in the brain and meninges[1], CMNT is considered a subtype pattern of intra-axial enhancement included in the category of fluid-secreting low-grade primary neoplasm. The CMNT pattern is seen in a variety of fluid-secreting neoplasms (Table 1), including, as the most common, hemangioblastoma[1–3], pilocytic astrocytoma[1–4], ganglioglioma[4], pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma[4] and, as less common, tanycytic ependymoma[5,6], intraparenchymal schwannoma[7], desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma[4,8] and cystic metastasis[9]. Our aim was to study the radiologic–pathologic correlation of intra-axial CMNT of the CNS.

Table 1.

Features of the most common brain tumors that present with a cyst with mural nodule appearance

| Tumor types | WHO | Peak age (years) | Features | Cyst |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pilocytic astrocytoma | I | 5–15 | Most common in the cerebellar hemispheres. Other typical location is optic nerve/chiasm/tract | The cyst content is iso- to slightly hyperintense to CSF. The cyst wall occasionally enhances |

| Hemangioblastoma | I | 40–60 | Most common in the posterior fossa. Flow voids visible in T1 and T2 in the nodular portion. The lesion abuts the pia | The cyst is slightly hyperintense in T1 compared with CSF The enhancement of the wall of the cyst is rarely seen in hemangioblastoma |

| Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma | II | 10–30 | Supratentorial superficial cortical mass. Usually in the temporal lobe | Cystic portion is isointense to CSF. Enhancement of adjacent meninges, with an appearance of dural tail |

| Ganglioglioma | I–II | 10–20 | Cortically based mass in a child/young adult with temporal lobe epilepsy. Calcifications inside the lesion are a common finding | The cyst often expands the cortex |

| Desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma | I | 1–2 | Large cyst with cortical-based enhancing tumor. Enhancement of adjacent pia and reactive dural thickening are specific findings | On T1 the hypointense cyst may contain septae while the nodule is heterogeneous |

Subjects and methods

A retrospective design was chosen given the rarity of CMNT. Relevant cases were obtained by taking advantage of the Department of Radiology’s data warehouse, which contains every diagnostic report produced by department radiologists since 2000. Using search tools developed in the division, cases were retrieved using multiple search term strategies. The inclusion criteria were: (1) the lesion should be primarily cystic; (2) the cyst cannot be smaller than one-third of the entire lesion; (3) there is a mural (from Latin murus = wall) nodule, i.e. a nodule that is peripherally located with respect to the cyst; (4) the nodule should enhance; the capsule of the lesion may or may not enhance.

Pilocytic astrocytoma

Formerly known as juvenile pilocytic astrocytoma, classified as World Health Organization (WHO) grade I, it is a well-circumscribed, often cystic, slow-growing tumor. Typically it presents as a cystic cerebellar CMNT or as an enlarged optic nerve/chiasm/tract with variable enhancement. It is located in the cerebellum in 60% of cases. In T1-weighted sequences, the solid portion of the CMNT is iso/hypointense to gray matter while the cyst content is iso- to slightly hyperintense to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (Figs. 1b and 2b). In T2 and fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences, the solid portion is hyperintense to gray matter while the cyst content is hyperintense to CSF. In FLAIR sequences, the cyst content is not suppressed (Fig. 1a). The cyst wall occasionally enhances[10], but cyst wall enhancement does not necessarily mean the presence of neoplastic tissue[11] and removal of the cyst wall does not affect the outcome in the case of pilocytic astrocytoma[12] (Figs. 1b and 2b). The pilocytic astrocytoma derives from astrocytic precursor cells and it is the most common primary brain tumor in children. Microscopically it shows classic biphasic pattern of two astrocyte populations: (a) compacted bipolar cells with Rosenthal fibers (Rosenthal fibers = electron dense glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) staining cytoplasmic inclusions); (b) loose-textured multipolar cells with microcysts, eosinophilic granular bodies.

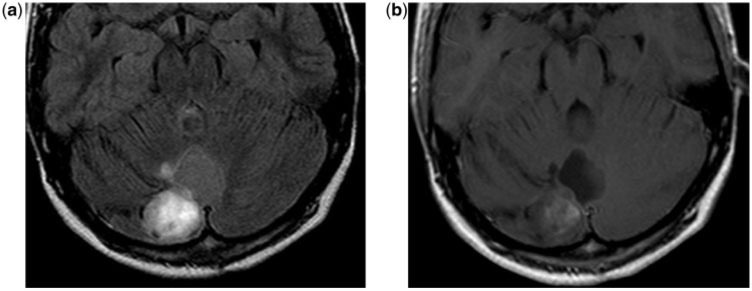

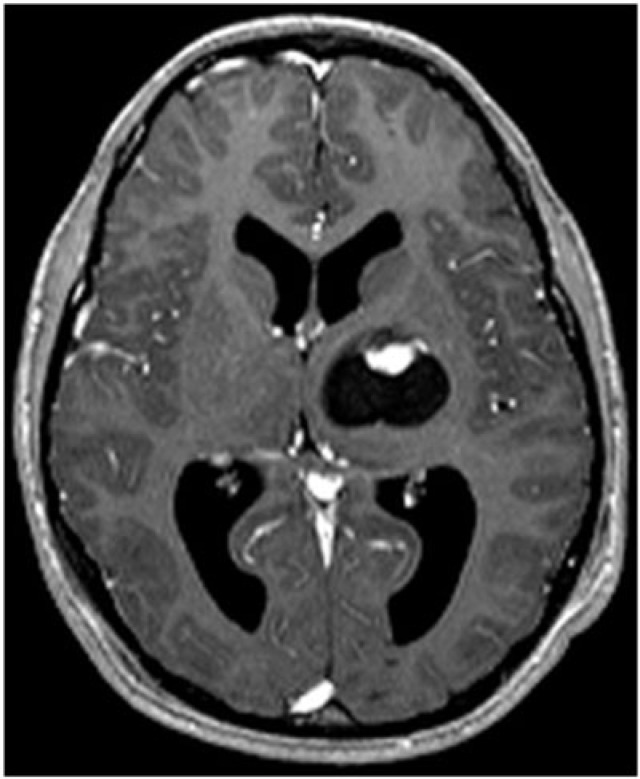

Figure 1.

An 11-year-old boy with a cerebellar pilocytic astrocytoma. (a) Axial T2-weighted FLAIR magnetic resonance (MR) image shows the cerebellar superficial hyperintense nodule and the lack of suppression of the signal in the cystic component. Compare with the CSF signal in the temporal horns. (b) Axial contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR image shows enhancement of the nodular component and slight enhancement of the cyst wall.

Figure 2.

A 6-year-old girl with a hypothalamic pilocytic astrocytoma. (a) Axial T2-weighted MR image shows a cyst with a heterogeneous nodular lesion in the hypothalamus. (b) Axial contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR image show heterogeneous enhancement of the nodular component and the lack of enhancement of the cyst wall.

Hemangioblastoma

Hemangioblastoma, also named capillary hemangioblastoma, is a vascular neoplasm of uncertain origin currently classified as a WHO grade I tumor[13]. It is found mostly in adults. It presents as a CMNT in 60% of cases with the enhancing mural nodule abutting the pia[2]; in 95% of cases, hemangioblastomas are in the posterior fossa, predominantly in the cerebellar hemispheres. The nodular portion occasionally demonstrates flow voids visible in T1- and T2- sequences, while the cyst is slightly hyperintense in T1 images compared with CSF. In T2 and FLAIR images, both cyst and nodule are hyperintense (Figs. 3a and 4a). The enhancement of the wall of the cyst is rarely seen in hemangioblastoma (Figs. 3b and 4b). Both cystic and nodular components of hemangioblastomas have to be totally surgically removed because they have a striking tendency to recur. The hemangioblastoma is a vascularized neoplasm with stromal cells of uncertain histogenesis. Historically they were assigned in the category of vascular meningiomas although they gained an independent WHO category from 1991. Regarding the pathogenesis of the formation of the cyst, a major hypothesis is that the absence of astrocytic end feet and tight junctions can be found in the microvessels of these neoplasms, which may lead to breakdown of the blood–brain barrier, and have a role in cyst formation[14]. The cystic fluid is xanthochromic, with a concentration of amino acids, alkaline phosphates, and mucoproteins similar to blood, suggesting that they originate by diffusion from the vascular component of the solid tumor[3].

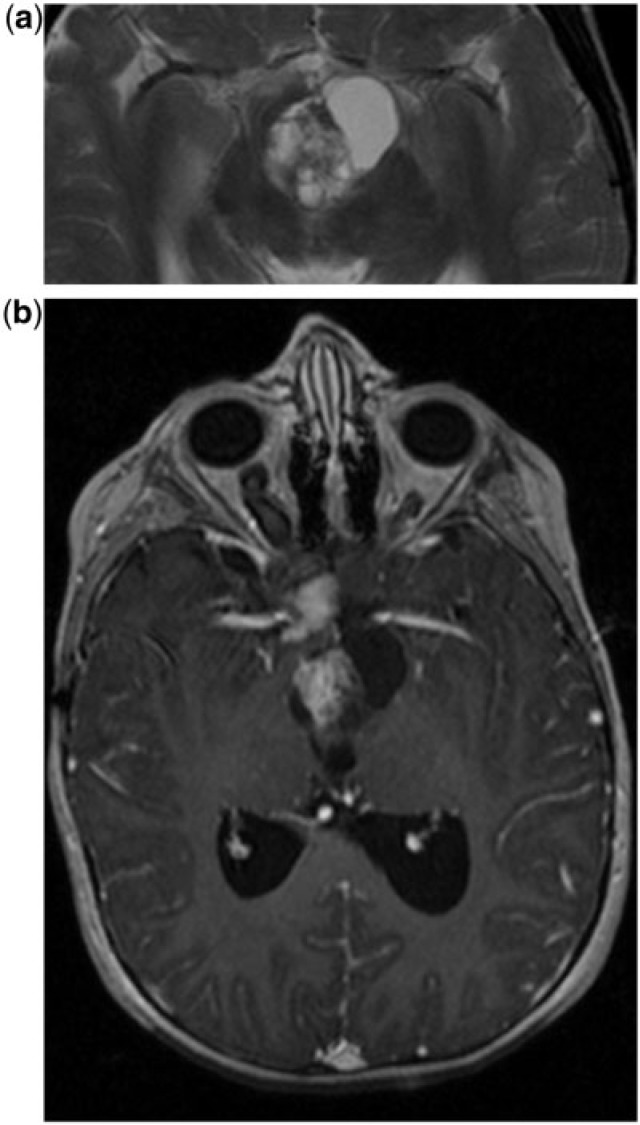

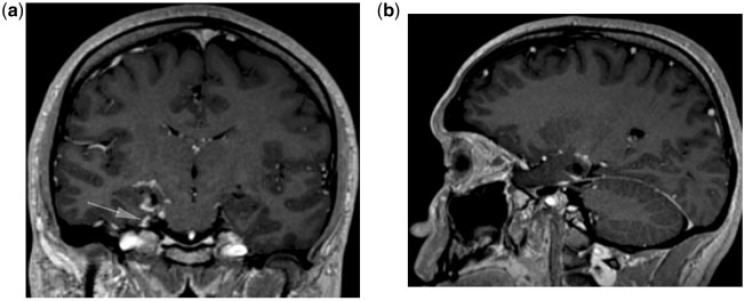

Figure 3.

A 38-year-old woman with a cerebellar hemangioblastoma. (a) Axial T2-weighted MR image shows a cyst with a nodular lesion in the cerebellum without perilesional edema; the nodule is heterogeneously hyperintense. (b) Coronal contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR image show the enhancing nodule of the lesion that abuts its inferior surface.

Figure 4.

A 65-year-old woman with a hemangioblastoma. (a) Coronal T2-weighted MR image shows a cyst with mural nodule lesion characterized by a very large cyst and a tiny peripheral nodule, which is hyperintense in T2. The cyst content is slightly hyperintense in T1 compared with CSF. (b) Axial contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR image show the enhancement of the small nodule that abuts the inferior cerebellum surface and the lack of enhancement of the cyst capsule. The cyst content is slightly hyperintense in T1 compared with CSF.

Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma

Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma (PXA) is a WHO grade II distinct type of benign astrocytoma. Typically it is a supratentorial cortical mass with an adjacent enhancing dural tail. CMNT appearance is present in upwards of 60% of cases. The temporal lobe is the most common location, followed by the parietal and occipital lobes. The mass is round to oval but despite its circumscribed appearance, the tumor often infiltrates into the brain. On T1 images, the nodule appears hypointense or isointense to gray matter while the cystic portion is isointense to CSF (Figs. 5 and 6). Sometimes an associated cortical dysplasia may also be seen. On T2 images, the pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma looks hyperintense or may have mixed signal intensity, and surrounding edema is rare (Figs. 5 and 6). On FLAIR images, the cyst content is normally suppressed. A peculiar feature is the presence of enhancement of adjacent meninges, with the appearance of a dural tail (in approximately 70% of cases) as visible in Fig. 6. The enhancing nodule often abuts the pial surface (Fig. 6a). From a pathologic point of view, the PXA is noted for cellular pleomorphism and xanthomatous change. It may originate from cortical (subpial) astrocytes or from multipotential neuroectodermal precursor cells common to both neurons and astrocytes. It has a pleomorphic appearance meaning that it can be highly variable in the size and shape of cells and/or their nuclei. CD34 antigen may help differentiate PXA from other tumors and may be associated with cortical dysplasia.

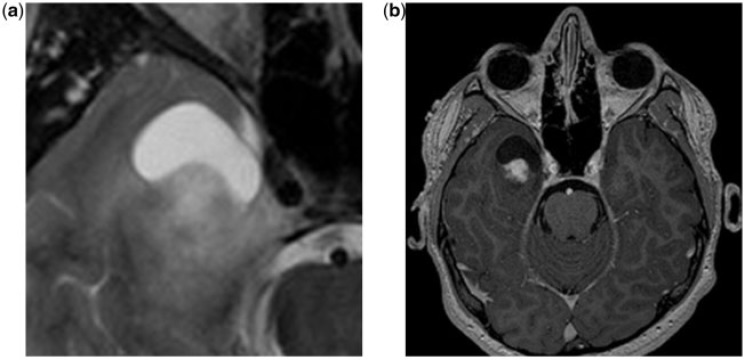

Figure 5.

A 15-year-old boy with pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma. Axial contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR image shows a pallido-thalamic cyst with mural nodule lesion. Note the absence of surrounding edema and the enhancement of the nodular component.

Figure 6.

A 28-year-old man with pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma. (a) Coronal and (b) sagittal contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR image shows the temporal mesial superficial tumor. Note the dural enhancement along the tentorium (arrow).

Ganglioglioma

The ganglioglioma is a well-differentiated, WHO grade I or II, slow-growing neuroepithelial tumor composed of neoplastic ganglion cells and neoplastic glial cells. It is one of the most common causes of temporal lobe epilepsy. Typical features are a partially cystic component with an enhancing, cortically based mass in a child/young adult with temporal lobe epilepsy. Most commonly it involves superficial hemispheres, most notably the temporal lobe (Fig. 7a), and it typically is 2–3 cm in adults and up to 6 cm in children. It is a well-circumscribed mass that often expands the cortex. Calcifications inside the lesion are a common finding. In T1 images it is hypo-isointense to gray matter; rarely it can be hyperintense for the presence of Ca2+; and has associated cortical dysplasia. In T2 images it is typically hyperintense (Fig. 7a). Enhancement is usually moderate and heterogeneous (Fig. 7b). Malignant transformation into glioblastoma multiforme has been reported. There are two theories on the etiology of the ganglioglioma: (a) it may be a neoplastic transformation of glial hamartoma or (b) it may derive from subpial granule cell transformation.

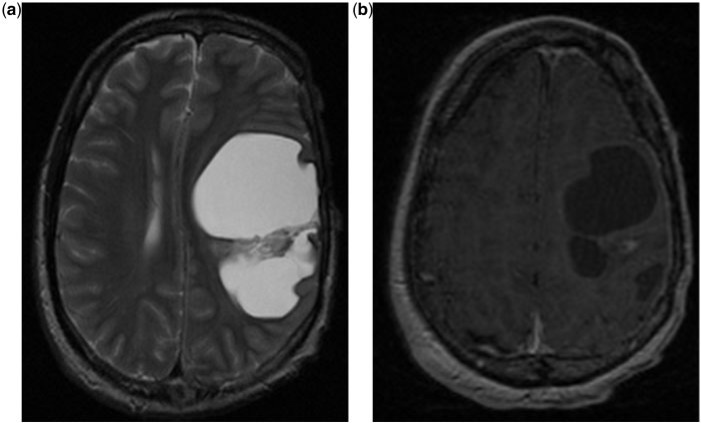

Figure 7.

A 14-year-old boy with a ganglioglioma. (a) Axial T2-weighted MR image shows a superficial cyst with a mural nodule lesion in the temporal lobe, which is the typical location. Note the concave interface between the nodule and the cyst. (b) Axial contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR image: note the heterogeneous contrast enhancement and the edgeless interface between the nodule and the temporal lobe parenchyma.

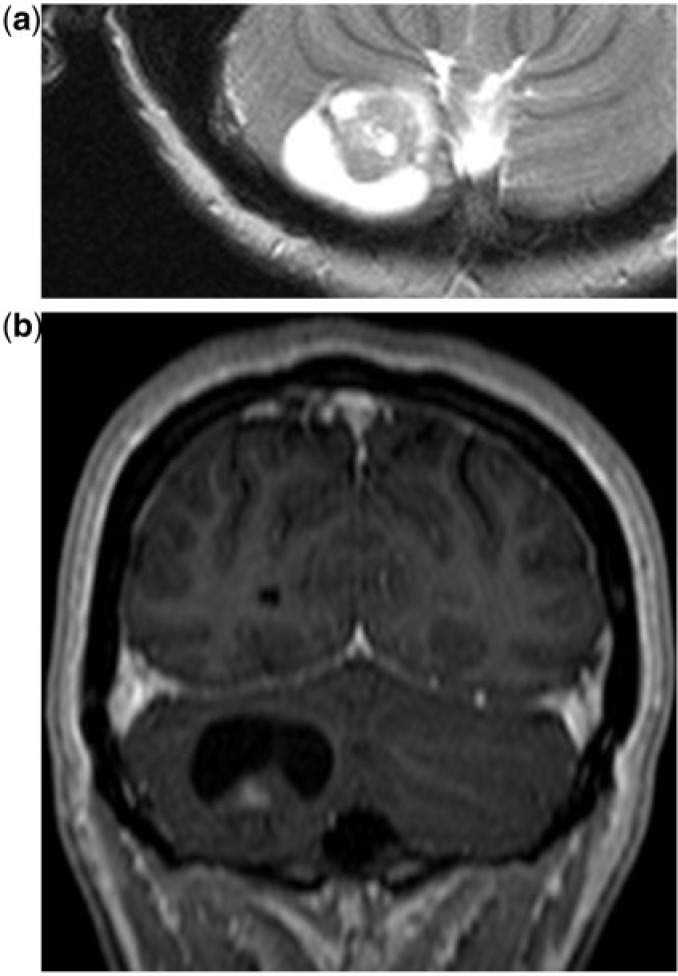

Desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma

Desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma (DIG) is a WHO grade I tumor that affects children in the first 2 years. Typical features are the presence of a large cyst with a cortical-based enhancing tumor nodule. Enhancement of the adjacent pia and the reactive dural thickening are quite specific findings. It tends to be frontal or parietal. On T1 images, the hypointense cyst may contain septae while the nodule is heterogeneous. On T2 images the cyst is hyperintense and the nodule usually has a low signal (Fig. 8a). The solid tumor nodule enhances markedly along with the leptomeninges and dura adjacent to the solid tumor (Fig. 8b). From a pathologic point of view, DIG has prominent desmoplastic stroma plus neoplastic astrocytes, with a variable neuronal component. DIG arises from subpial astrocytes; the large cyst contains xanthochromic fluid and the tumor may be firmly attached to the dura and brain tissue.

Figure 8.

A 5-year-old girl with desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma. (a) Axial T2-weighted MR image shows a large hemispheric cystic lesion with a heterogeneous nodule with irregular septae communicating with the cyst wall. (b) Axial T1-weighted MR image after contrast enhancement shows slight enhancement of the nodule.

Metastases

A frank CMNT pattern in metastasis is rare. Recently, a case has been described in the literature[9]. Cystic metastasis is much more common (Fig. 9).

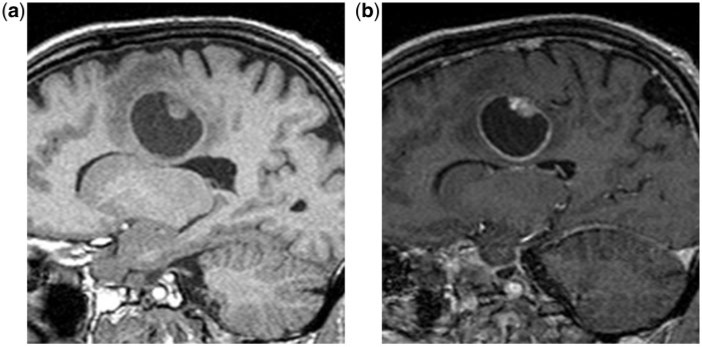

Figure 9.

A 62-year-old man with a bronchial carcinoma metastasis. (a) Sagittal T1-weighted MR image shows a deep frontal cyst with mural nodule lesion. (b) Sagittal contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR image shows the enhancement of both the nodule and the cyst capsule.

Very rare cases

Tanycytic ependymoma

Tanycytic ependymomas are a subtype of ependymomas, recognized as a new pathologic entity in the WHO classiffication of 2000[13]. The tumor cells have morphological characteristics resembling tanycytes, a special subtype of ependymal cells. Tanycytic ependymomas arising in the cervicomedullary junction have been consistently associated with a CMNT appearance (Fig. 10). It is paramount that tanycytic ependymomas are removed totally by means of a surgical intervention because they frequently recur by cyst formation.

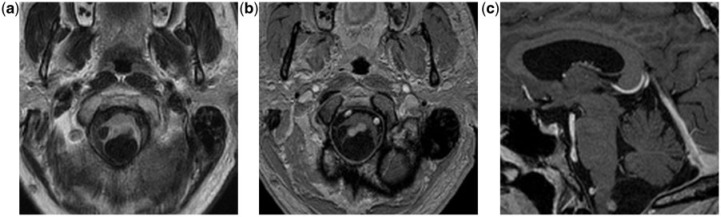

Figure 10.

A 61-year-old man with a tanycytic ependymoma. (a) Axial T2-weighted FLAIR MR image show a posterior medullary cystic with mural nodule lesion. (b) Axial and (c) sagittal contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR images show mural nodule enhancement.

Intracerebral schwannoma

Fewer than 50 cases of intracerebral schwannoma are described in the literature. Since Schwann cells are normally not present in the cerebral parenchyma, it is difficult to explain the origin of intracranial parenchymal schwannomas; it is suggested that they derive from Schwann cells within perivascular nerve plexi[7].

Rosette-forming glioneuronal tumor (RGNT) of the fourth ventricle

RGNT was described as an entity in 2002. Usually it presents as a cerebellar lesion in a young adult. It originates from the roof and protrudes into the fourth ventricle and is often present with a CMNT pattern[16].

Papillary glioneuronal tumor (PGNT)

PGNT was described as an entity in 1998. It is a very rare lesion (30 cases described so far) located usually in the temporal lobe. Many of the few PGNT described had a CMNT pattern[17].

Adjacent epidermoid cyst and primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL)

A CMNT pattern was present in a single case report of epidermoid cyst and PCNSL occurring as adjacent synchronous tumors[18].

Vascular lesions

Parenchymal brain perianeurysmal cyst is a very rare but potentially very dangerous lesion that radiologists should be aware of when facing a CMNT. The mechanism of cyst formation is still controversial[19]. Cavernous angiomas accompanied by a cyst are a rare occurrence[20].

Neurocysticercosis

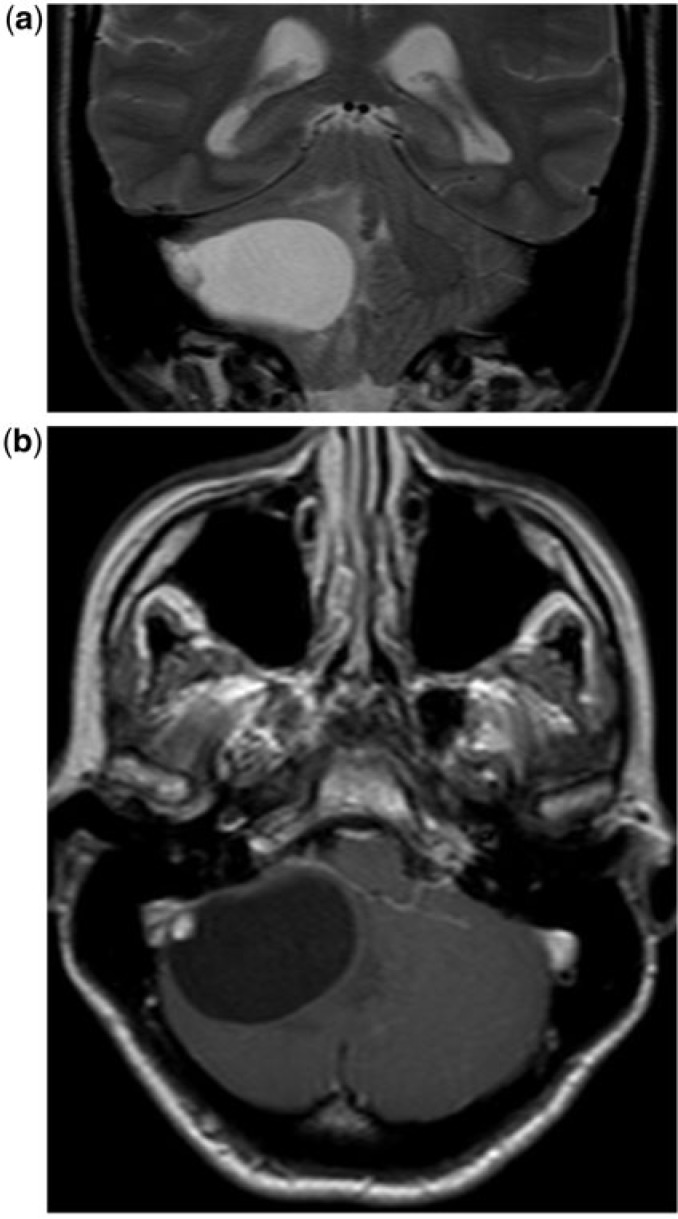

Neurocysticercosis is the most common parasitic disease of the CNS. The typical CMNT pattern is very rare in neurocysticercosis and is mainly present when the lesion is in the colloidal stage (Fig. 11).

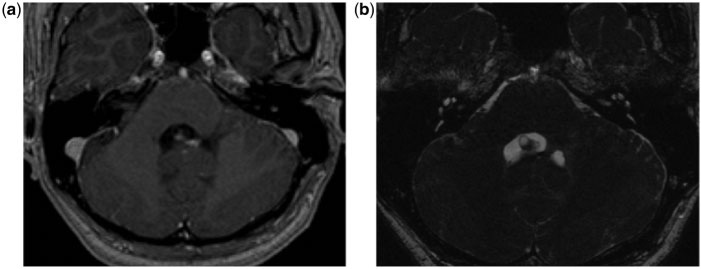

Figure 11.

A 47-year-old man with neurocysticercosis. (a) Axial T1-weighted postcontrast image demonstrates a cystic lesion with mural nodule within the fourth ventricle. (b) High-resolution axial constructive interference in steady state (CISS) image demonstrates the wall of the cystic lesions within the fourth ventricle.

Conclusion

The CMNT appearance is an important radiological pattern of brain lesion that can be related to primary or secondary brain tumors. Other rare causes such as infections or vascular anomalies should be considered.

Footnotes

This paper is available online at http://www.cancerimaging.org. In the event of a change in the URL address, please use the DOI provided to locate the paper.

References

- 1.Smirniotopoulos JG, Murphy FM, Rushing EJ, Rees JH, Schroeder JW. Patterns of contrast enhancement in the brain and meninges. Radiographics. 2007;27:525–551. doi: 10.1148/rg.272065155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hasso AN, Bell SA, Tadmor R. Intracranial vascular tumors. Neuroimaging Clin North Am. 1994;4:849–870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho VB, Smirniotopoulos JG, Murphy FM, Rushing EJ. Radiologic-pathologic correlation: hemangioblastoma. Am J Neuroradiol. 1992;13:1343–1352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koeller KK, Henry JM. From the archives of the AFIP: superficial gliomas: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. Radiographics. 2001;21:1533–1556. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.21.6.g01nv051533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shin JH, Lee HK, Khang SK, et al. Neuronal tumors of the central nervous system: radiologic findings and pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2002;22:1177–1189. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.5.g02se051177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ito T, Ozaki Y, Nakagawara J, Nakamura H, Tanaka S, Nagashima K. A case of cervicomedullary junction tanycytic ependymoma associated with marked cyst formation. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2005;22:29–33. doi: 10.1007/s10014-005-0174-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casadei GP, Komori T, Scheithauer BW, Miller GM, Parisi JE, Kelly PJ. Intracranial parenchymal schwannoma. A clinicopathological and neuroimaging study of nine cases. J Neurosurg. 1993;79:217–222. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.79.2.0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tamburrini G, Colosimo C, Giangaspero F, Riccardi R, Di Rocco C. Desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma. Childs Nerv Syst. 2003;19:292–297. doi: 10.1007/s00381-003-0743-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garg A, Suri A, Gupta V. Cyst with a mural nodule: unusual case of brain metastasis. Neurol India. 2004;52:136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pencalet P, Maixner W, Sainte-Rose C, et al. Benign cerebellar astrocytomas in children. J Neurosurg. 1999;90:265–273. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.90.2.0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beni-Adani L, Gomori M, Spektor S, Constantini S. Cyst wall enhancement in pilocytic astrocytoma: neoplastic or reactive phenomena. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2000;32:234–239. doi: 10.1159/000028944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palma L, Guidetti B. Cystic pilocytic astrocytomas of the cerebral hemispheres. Surgical experience with 51 cases and long-term results. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:811–815. doi: 10.3171/jns.1985.62.6.0811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, et al. The 2007 who classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Y, Tachibana O, Hasegawa M, et al. Absence of tight junctions between microvascular endothelial cells in human cerebellar hemangioblastomas. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:660–670; discussion 660–670. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000223372.18607.D7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pierallini A, Bonamini M, Di Stefano D, Siciliano P, Bozzao L. Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma with CT and MRI appearance of meningioma. Neuroradiology. 1999;41:30–34. doi: 10.1007/s002340050700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vajtai I, Arnold M, Kappeler A, et al. Rosette-forming glioneuronal tumor of the fourth ventricle: Report of two cases with a differential diagnostic overview. Pathol Res Pract. 2007;203:613–619. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Atri S, Sharma MC, Sarkar C, Garg A, Suri A. Papillary glioneuronal tumour: a report of a rare case and review of literature. Childs Nerv Syst. 2007;23:349–353. doi: 10.1007/s00381-006-0196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masuoka J, Sakata S, Maeda K, Sugita Y. Adjacent epidermoid cyst and primary central nervous system lymphoma: Case report. Surg Neurol. 2008;69:530–533; discussion 533–534. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2007.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benvenuti L, Gagliardi R, Scazzeri F, Gaglianone S. Parenchymal perianeurysmal cyst in the brain: case report. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:E788; discussion E788. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000204306.38345.4F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lim S-C, Hong R, Kim Y-S, Jang S-J. Large cystic cavernous angioma of the cerebellum mimicking pilocytic astrocytoma. J Neurooncol. 2006;79:169–170. doi: 10.1007/s11060-005-9065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]