Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) has emerged over the last decade as a major cause of gastrointestinal morbidity in both children and adults. EoE is a chronic inflammatory condition defined by symptoms of esophageal dysfunction, an eosinophilic infiltrate in the esophageal epithelium, and the absence of other potential causes of eosinophilia.1 First described in 1978,2 EoE was only rarely reported for the subsequent two decades.3–7 In the late 1990s, however, the condition was increasingly recognized, first in children and then in adults, and the incidence and prevalence have been rapidly increasing.8–14 The prevalence of EoE varies based on the study design and setting.15 In the general population, case estimates have ranged from 0.2 – 4/1,000 in asymptomatic patients,10, 16 but in those undergoing endoscopy for upper GI symptoms, EoE is found in 5–16%.17–19 Current estimates suggest that the overall prevalence of EoE in the general population is between 43 and 52/100,000.11, 20

EoE is thought to be an immune-mediated disorder where food or environmental antigens stimulate a Th2 inflammatory response.1, 21 Key cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 stimulate the production of eotaxin-3 in the esophageal mucosa. Eotaxin-3, a potent chemokine which is markedly upregulated in EoE, recruits eosinophils to the esophageal mucosa.21, 22 In turn, activated eosinophils secrete proinflammatory and profibrotic mediators, cause local tissue damage, and recruit additional inflammatory cells (mast cells and fibroblasts), perpetuating the inflammatory response and resulting in esophageal remodelling.23–26 The interaction between environmental exposures and genetic susceptibility has been illustrated both in animal models and in patients with EoE.22, 27–29

With the increasing knowledge base for EoE, paradigms for diagnosis and treatment of EoE are also evolving. The purpose of this paper is to review the approach to diagnosis and management of EoE, with a focus on the evidence that informs current practice. The consensus diagnostic guidelines will be presented, and a discussion of the clinical, endoscopic, and histologic features of EoE will illustrate practical points and potential pitfalls related to diagnosis of EoE. The three major treatment approaches to EoE – pharmacologic therapy, dietary modification, and endoscopic dilation – will also be presented in detail.

Diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis

The first consensus guidelines for diagnosis of EoE were published in 2007 and represented a major milestone.30 Prior to this, there was marked variability in the literature with regard to how the disease was defined,31 and after this there has been some degree of increasing uniformity in diagnosis, though this has not been complete.32, 33 The 2007 guidelines emphasized that EoE was a clinicopathologic condition, meaning that both clinical and histologic features were needed for diagnosis and that neither could be interpreted in isolation. Three specific criteria were required to diagnose EoE: 1) symptoms of esophageal dysfunction (e.g. dysphagia, food impaction, heartburn, chest pain, regurgitation, etc); 2) at least 15 eosinophils per high-power microscopy field (eos/hpf) in at least one esophageal biopsy; and 3) exclusion of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) as a cause of esophageal eosinophilia by either lack of response to a high-dose proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) trial or negative pH monitoring.30 As knowledge about EoE increased, there was a recognition that the guidelines would need to evolve. In particular, the complex relationship between EoE, GERD, and esophageal eosinophilia became increasingly acknowledged,34 EoE and GERD were observed to coexist in some cases, and a new phenomenon termed PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia (PPI-REE; discussed below) was described.

To address these issues, the consensus guidelines were updated in 2011 and presented a conceptual definition of EoE as a “chronic immune/antigen-mediated esophageal disease characterized clinically by symptoms related to esophageal dysfunction and histologically by eosinophil-predominant inflammation.”1 To diagnose EoE, three criteria were retained but with some modifications (Table 1): 1) symptoms of esophageal dysfunction; 2) a maximum eosinophil count of ≥15 eos/hpf, with few exceptions; and 3) eosinophilia limited to the esophagus with exclusion of other possible causes of esophageal eosinophilia, including PPI-REE. These new guidelines address the limitations of excluding GERD in all cases, provide some degree of flexibility in histologic interpretation, and recognize PPI-REE as a new entity. Given the ongoing advances in EoE-related knowledge, it is expected that these guidelines will continue to be updated as new data are generated.

Table 1.

Diagnostic guidelines for EoE1

Because EoE is a clinicopathologic disease, the following clinical and histologic information are required for diagnosis:

|

Clinical features of eosinophilic esophagitis

While the diagnostic guidelines require symptoms of esophageal dysfunction, EoE can present with a range of symptoms that vary by patient age.1, 8, 13, 35, 36 In adolescents and adults, dysphagia is the hallmark of EoE, affecting between 25% and 100% of patients depending on the study design and setting.9, 13, 17, 19, 31 Acute food impaction is the most extreme presentation of solid food dysphagia, and EoE is now the cause in approximately half of cases of patients with food impaction requiring emergent evaluation and bolus clearance.37–39 On history, it is important not only to ask patients about trouble swallowing, but also about avoidance of specific foods, ability to dine at restaurants, and thoroughness of chewing in order to characterize dietary modifications that minimize overt symptoms of dysphagia. In younger children, the presentation is more nonspecific, with symptoms of feeding intolerance, failure to thrive, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and regurgitation.9, 35, 40 In patients of both ages, between 10% and 100% have heartburn, again depending on study design and setting.9, 13, 17, 19, 31 Conversely, EoE is the cause of heartburn 1–8% of patients with PPI-refractory symptoms of GERD.9, 19, 41–44 It is important to note that no symptom in isolation is specific for the diagnosis of EoE.

EoE has been described across the age spectrum, but is most common before the age of 40.9, 12, 31 It is also thought to be more common in males and Caucasians,17–19, 40, 45–47 but as more data are accrued from centers with diverse patients populations, EoE is being reported with increasing frequency in African-American and other minority populations.19, 46, 48 Associated allergic diseases such as atopic dermatitis, atopic rhinitis/sinusitis, asthma, and food allergies are also very common in patients with EoE. In children, up to 50–80% have atopy, with a somewhat lower rate in adults.13, 40, 49–52 Atopy is not universal in EoE, however, and the role of the allergist is often dependent on local expertise and practice patters. The most recent guidelines suggest that referral to an allergist be considered to help maximize therapy for non-esophageal allergic diseases and assist with the interplay between multiple allergic conditions.1

Endoscopic features of eosinophilic esophagitis

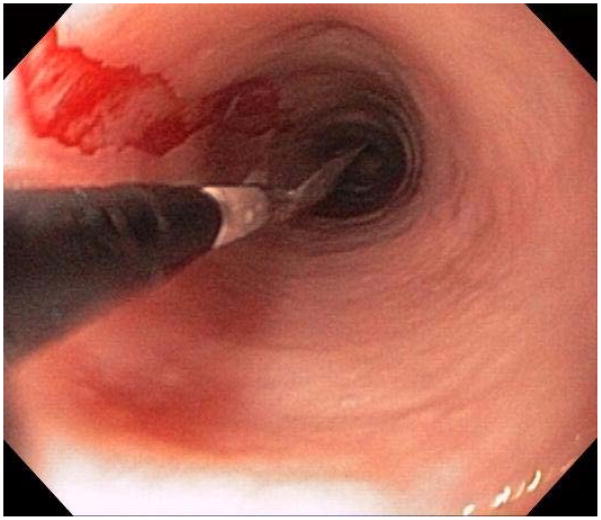

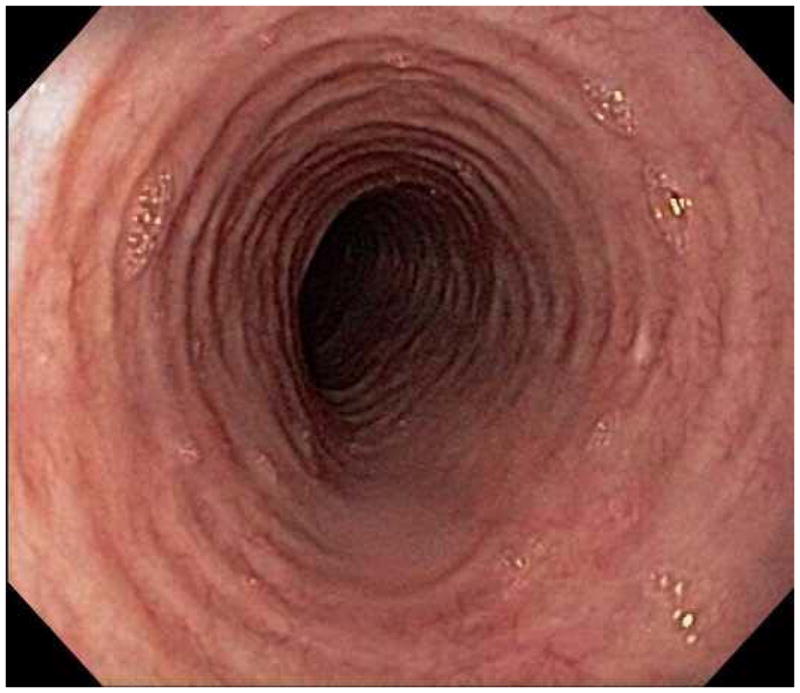

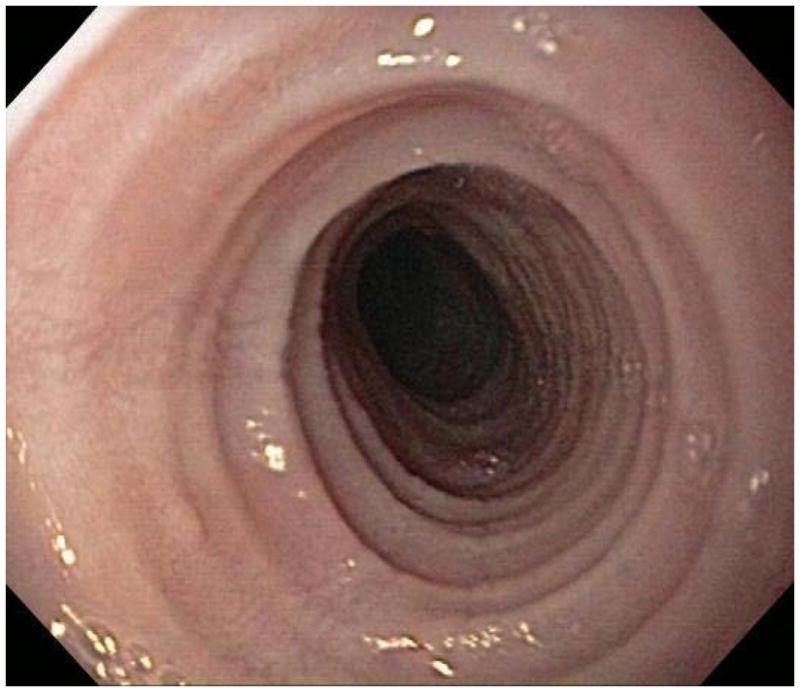

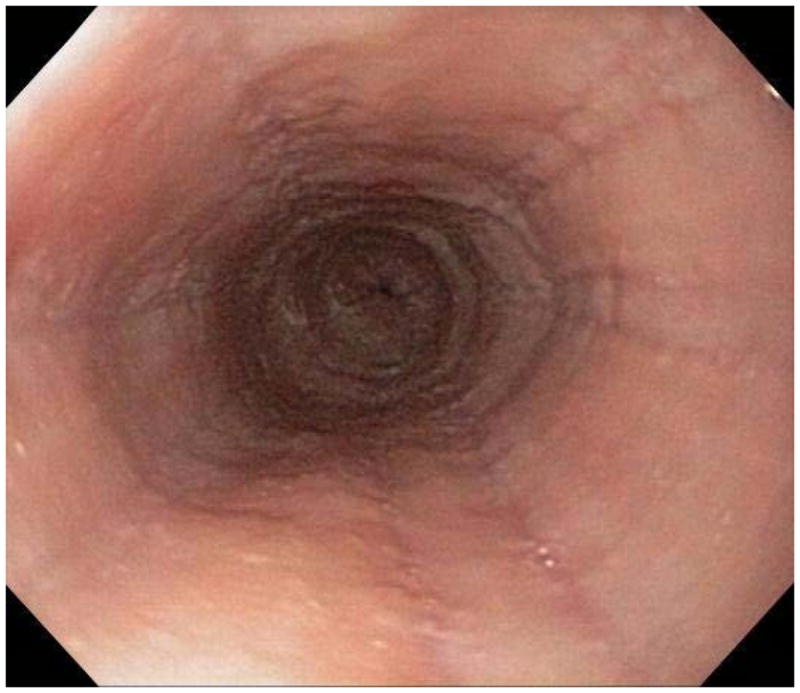

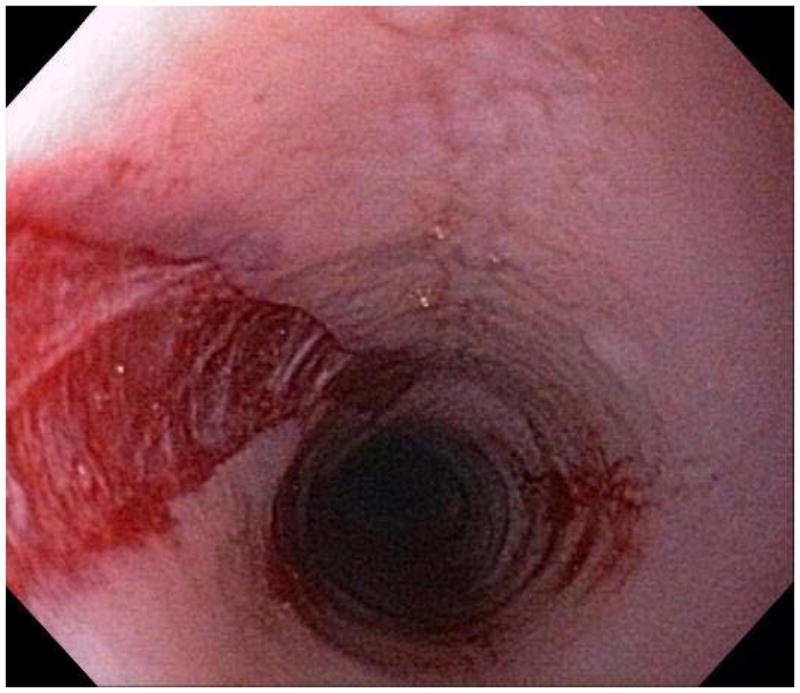

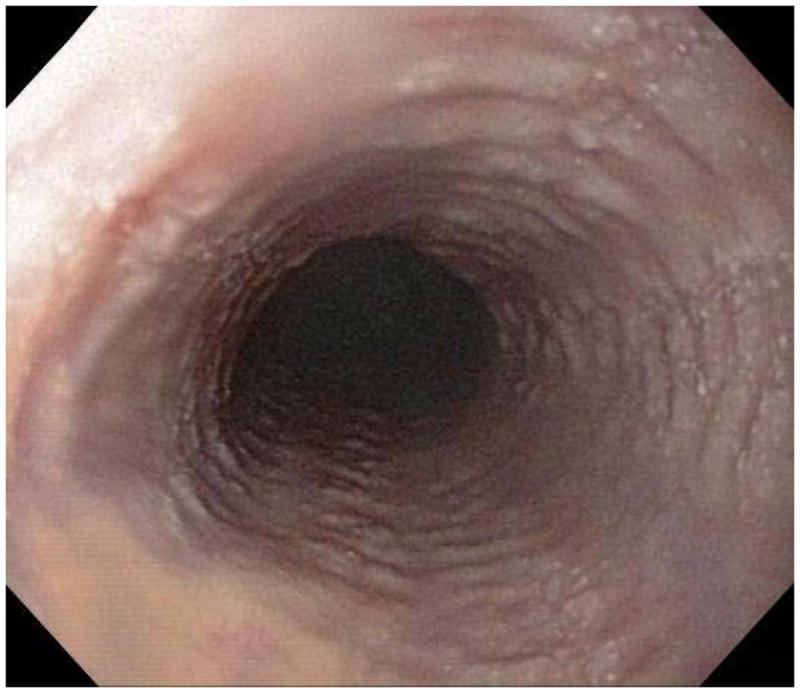

When a suggestive clinical picture leads to suspicion of EoE, upper endoscopy (esophagogastroduodenoscopy; EGD) is needed to inspect the esophagus, evaluate for alternative causes, and obtain esophageal biopsies. There are number of typical endoscopic findings of EoE, although similar to symptoms, none are specific for the condition. Findings can occur individually or in combination and include: esophageal rings which can be fixed or transient; narrow-caliber esophagus; longitudinal furrows running parallel to the axis of the esophagus; mucosal pallor, congestion or decreased vascularity; white plaques or exudates which can inadvertently be mistaken for candidal esophagitis; and fragile esophageal mucosa, termed “crêpe-paper mucosa”, where a tear occurs with passage of the endoscope (Figure 1). It is important to note that in approximately 7–10% of subjects with EoE, the esophagus will appear normal,31, 53 and if biopsies are not obtained, the diagnosis will be missed. In addition, two recent studies showed that the inter- and intra-observer reliability of detecting findings of EoE are only fair.54, 55 Compounding this, in a recent meta-analysis of 100 studies reporting EoE findings in over 4600 EoE patients and 2700 controls, the sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of endoscopic findings in EoE were insufficient to make diagnostic decisions.53 Therefore, it is recommended that esophageal biopsies be obtained in all patients suspected of having EoE regardless of the endoscopic appearance.1 Moreover, when performing biopsies, at least 2–4 from the distal and 2–4 from the proximal esophagus should be taken to maximize diagnostic sensitivity.1 This practice is supported by studies showing that the esophageal eosinophilic infiltrate in EoE is patchy,56, 57 that eosinophil levels vary between the proximal and distal esophagus,58, 59 and that increasing numbers of biopsies improve the likelihood of making the correct diagnosis,58, 60 but prospective studies comparing different biopsy protocols for diagnosis of EoE have not been conducted.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic findings of EoE include fixed esophageal rings (A), narrow caliber esophagus (B; also note the pale/congested mucosa with decreased vascularity), longitudinal furrows running parallel to the axis of the esophagus (C), white plaques or exudates (D), and crêpe-paper mucosa which tears passage of the endoscope alone (E). Often, a combination of these findings can be seen at the same time (F).

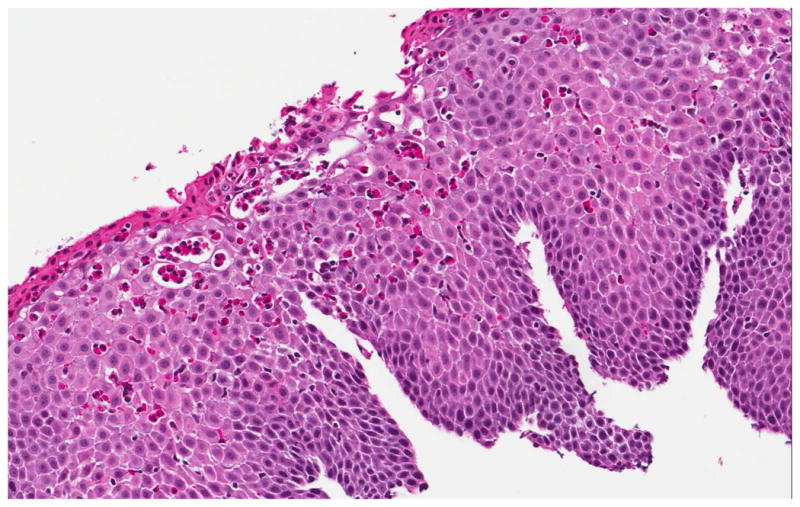

Histologic features of eosinophilic esophagitis

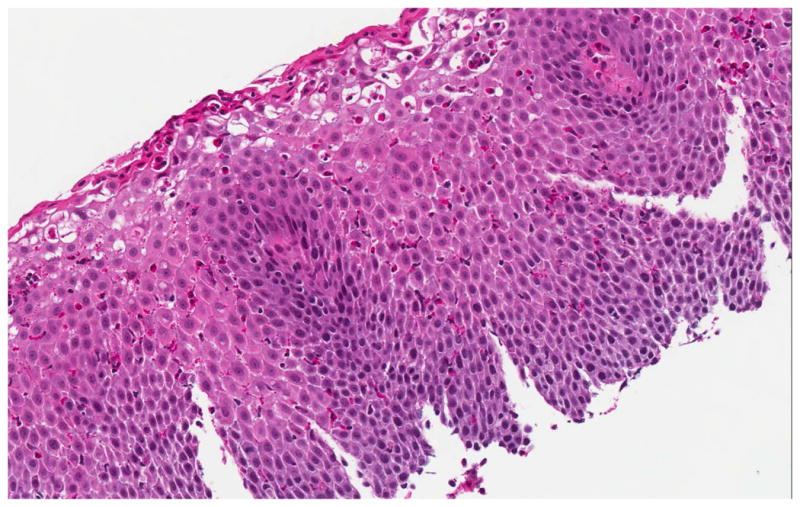

On examination of biopsy specimens, an eosinophilic infiltrate in the esophageal epithelium with ≥ 15 eos/hpf suggests the diagnosis of EoE (Figure 2). However, like clinical symptoms and endoscopic findings, esophageal eosinophilia alone is not diagnostic for EoE and the biopsy findings must be placed in the clinical context.1, 61, 62 There are also a number of associated histopathologic features of EoE, including: eosinophil degranulation where extracellular deposition of eosinophil granule proteins is observed; eosinophil microabscesses, defined by clusters of ≥ 4 eosinophils; basal zone hyperplasia or rete peg elongation; spongiosis; and fibrosis of the lamina propria if sufficient subepithelial tissue is present for evaluation (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Histologic findings of EoE include a brisk infiltrate of eosinophils in the esophageal epithelium, eosinophilic microabscesses (clusters of 4 or more eosinophils), spongiosis, and basal zone hyperplasia (A). In addition to an eosinophilic infiltrate, spongiosis, and basal zone hyperplasia, this sample shows eosinophil degranulation with extracellular eosinophil granules dispersed throughout the epithelium (B). If an esophageal biopsy contains tissue deeper than epithelium, fibrosis of the lamina propria can often be seen (C).

Potential diagnostic pitfalls

When the correct combination of clinical and histologic findings is present, EoE can be diagnosed. However, in many cases the diagnostic process is challenging because findings may not be clear-cut and there can be overlap between clinical entities such as EoE and GERD. For each of the diagnostic criteria and associated clinical findings, there are important pitfalls to avoid in the diagnostic process. First, while there is excellent inter- and intra-observer reliability for pathologists determining eosinophil counts using a specified protocol,63 the high-power field (hpf) size varies depending on make and model of the microscope used by a given pathologist.31 Therefore, for any given eosinophil density (in eos/mm2), the specific eosinophil count (in eos/hpf) will depend on the hpf size and it is possible that a count that falls below the diagnostic threshold on one microscope would be above the threshold on a different one.31 This is one reason that communication with pathologists about findings, understanding how eosinophils are quantified, and also reporting associated biopsy findings beyond the eosinophil count alone are all important.

A key point is that the finding of esophageal eosinophilia does not immediately confer a diagnosis EoE. There is a differential diagnosis of esophageal eosinophilia that must be considered, which includes other eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders such as eosinophilic gastroenteritis, GERD, PPI-REE, hypereosinophilic syndrome, infection, achalasia, drug hypersensitivity, Crohn’s disease, connective tissue disease, and others.1, 30 While most of these entities are uncommon and can be readily excluded with a basic evaluation, from a practical standpoint GERD and PPI-REE present the most commonly encountered challenges. For GERD, there is substantial clinical (heartburn, dysphagia, chest pain, regurgitation) and histologic (esophageal eosinophilia) overlap with EoE.1, 34, 44 Previously, it was felt that if a patient was treated with a PPI with subsequent resolution of symptoms and esophageal eosinophilia, then EoE was excluded and the diagnosis was GERD. However, the situation is no long straightforward due to the recognition of PPI-REE.

In 2006, a case series presented three children with dysphagia, food impaction, vomiting and suspected EoE.64 All had high levels of esophageal eosinophilia, and all completely responded to PPI therapy. The study raised the question of whether this phenomenon was GERD or an EoE phenotype that was PPI-responsive. Since then, several studies have shown that approximately one-third of patients or more with clinical symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and esophageal eosinophilia respond to PPI therapy.65–70 As of yet, it is not know if these patients have an atypical presentation of GERD, a variant of EoE that responds to PPI therapy, or a completely different entity, but clinical features and pH testing do not appear to predict response.65, 67 Intriguing preliminary data show an anti-inflammatory effect of PPIs independent of an anti-acid effect as a potential explanation for this clinical observation.71 The recognition of PPI-REE implies that the diagnosis of EoE now requires a PPI trial, not to exclude GERD necessarily, but to evaluate for PPI-response in patients with esophageal eosinophilia.1 Typically, an 8 week course of 20–40 mg twice daily of any of the available agents is felt to be adequate for this trial, but there are few data to support specific dosing regimens or agents.66, 67 While much more needs to be learned about this patient sub-group, currently PPI-REE must be excluded formally to diagnose EoE.

Because of these diagnostic challenges and potential pitfalls, there is ongoing research to develop new diagnostic approaches. Though these methods are not yet validated for clinical use, they are promising and may have substantial utility in the near future. These include clinical scoring systems,13, 72, 73 enhanced or novel endoscopic imaging techniques,54, 74, 75 functional luminal imaging of the esophagus,76 biomarker assessments on esophageal biopsies,77–80 non-invasive serum biomarkers,81–83 and genetic testing.22, 84

Treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis

Treatment of EoE is focused on improving both patient symptoms and histology on esophageal biopsies, as well as correcting or preventing complications such as esophageal strictures or food impactions leading to esophageal rupture, but there are currently few data to support specific treatment endpoints.1, 85 Ideally, the goal would be complete symptom resolution and normalization of the esophageal epithelium with elimination of all eosinophils, but in practice symptom improvement and histologic response do not always correlate,72, 85–89 and, as discussed below, the treatment trials to date have used different primary outcomes. Therefore, aiming to improve patient symptoms and substantially reduce the level of esophageal eosinophilia, while minimizing treatment side effects and adverse impact on quality of life, is a sensible strategy until more data can inform specific recommendations. This strategy will typically require a follow-up endoscopy after an initial course of therapy to assess for histologic response.

Overall, there are three general categories of treatment, often referred to as “the three D’s”: drugs, diet, and dilation.1, 90, 91 While there are as yet no FDA-approved medications or devices to treat EoE, strong data supporting all three categories of EoE treatment have been developed over the past decade.

Pharmacologic therapy

Topical corticosteroids

Corticosteroids used topically are a mainstay of EoE treatment and first line agents in many cases. These are typically asthma preparations (multi-dose inhalers or nebulizer solutions) that are taken orally so the medication is swallowed rather than inhaled. The initial experience was presented in a pediatric case series,92 and subsequent observational studies reported that medications such as fluticasone and budesonide, when swallowed, improved patient symptoms, decreased esophageal eosinophilia, and were generally well-tolerated.9, 93–98

There have now been 9 randomized clinical trials examining the use of topical steroids for EoE, including fluticasone vs placebo,99, 100 fluticasone vs prednisone,59 fluticasone vs esomeprazole,68, 69 budesonide vs placebo,87, 101, 102 and a study of two forms of budesonide.103 Table 2 summarizes the details of these trials, and presents the most stringent outcome (ie the greatest degree of improvement in eosinophilia) rather than the primary outcome, for ease of comparison given that the primary outcome varied in each trial.

Table 2.

Summary of randomized clinical trials for treatment of EoE

| Author, year | Treatment (dose; n) | Comparator (dose; n) | Subjects | Duration | Histologic outcomes | Symptom outcomes | Comment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Definition | Treatment | Comparator | Definition | Treatment | Comparator | ||||||

| Corticosteroids | |||||||||||

| Konikoff, 2006 | Fluticasone* 880 ucg/d (n = 21) | Placebo (n = 15) | Children | 3 mos | Complete response (≤1 eos/hpf) | 50% | 9% | -- | -- | -- | Full symptom data n/a |

| Schaefer, 2008 | Fluticasone* 880–1760 ucg/d (n = 40) | Prednisone 2 mg/kg/d (max 60mg) (n = 40) | Children | 12 wks (4 wk rx, 8 wk wean) | Histologic response in biopsy grade | 94% | 94% | Presenting symptom improved | 97% | 100% | -- |

| Peterson, 2009 | Fluticasone* 880 ucg/d (n = 15) | Esomeprazole 40 mg/d (n = 15) | Adults | 8 wks | Complete resolution (≤5 eos/hpf) | 15% | 33% | Dysphagia improved | 50% | 25% | Subjects not on PPI prior to enrollment |

| Dohil, 2010 | Budesonide† 1–2 mg/d (n = 15) | Placebo (n = 9) | Children | 3 mos | Complete response (≤6 eos/hpf) | 87% | 0% | Symptom score (all symptoms) | 3.5 → 1.2 | 2.7 → 1.8 | -- |

| Straumann, 2010 | Budesonide‡ 2 mg/d (n = 18) | Placebo (n = 18) | Adults | 15 d | Histologic remission (<5 eos/hpf) | 72% | 11% | Dysphagia symptom score | 5.6 → 2.2 | 5.3 → 4.7 | -- |

| Gupta, 2011 | Budesonide# 0.35–4 mg/d (n = 53) | Placebo (n = 18) | Children | 12 wks | Histologic remission (≤1 eos/hpf) | 77% | 0% | Symptom score (all symptoms) | “Improved” | “Improved” | Abstract; full symptom data n/a |

| Fouad, 2011 | Fluticasone* 880 ucg/d (n = 21) | Esomeprazole 40 mg/d (n = 21) | Adults | 8 wks | Eosinophilia resolution (< 7 eos/hpf) | 19% | 35% | Mayo dysphagia score | 17 → 12 | 19 → 1 | Abstract |

| Alexander, 2012 | Fluticasone* 1760 ucg/d (n = 21) | Placebo (n = 15) | Adults | 6 wks | Complete response (>90% eos. decrease) | 62% | 0% | Dysphagia completely improved | 43% | 29% | |

| Dellon, 2012 | Budesonide† 2 mg/d (n = 13) | Budesonide‡ 2 mg/d (n = 12) | Adults | 8 wks | Complete response (<1 eos/hpf) | 64% | 27% | Mayo dysphagia score | 25 → 15 | 34 → 10 | |

| Biologics | |||||||||||

| Straumann, 2010 | Anti-IL-5** (n = 5) | Placebo (n = 6) | Adults | 13 wks | Complete remission (< 5 eos/hpf) | 0% | 0% | Global symptoms improved | 40% | 17% | |

| Assa’ad, 2011 | Anti-IL-5** med/high dose (n = 40) | Anti-IL-5** low dose (n = 19) | Children | 12 wks | Complete response** (<5 eos/hpf) | 0% | 18% | -- | -- | -- | Multiple individual symptoms analyzed |

| Spergel, 2012 | Anti-IL-5†† low/med/high doses (n = 169) | Placebo (n = 57) | Children | 15 wks | % decrease in peak eosinophil count†† | 64% | 24% | Decrease in primary symptom score | 1.12 | 1.14 | Physician global assessment also analyzed |

| Fang, 2011 | Anti-IgE‡‡ (n = 16) | Placebo (n = 14) | Adults | 16 wks | Peak eosinophil count‡‡ | 28 → 30 eos/hpf | 34 → 26 eos/hpf | Dysphagia symptom score | 4 → 3 | 6 → 4 | Abstract |

| Other | |||||||||||

| Straumann, 2012 | CRTH2 antagonist## (n = 14) | Placebo (n = 12) | Adults | 8 wks | Mean eosinophil count | 115 → 74 eos/hpf | 103 → 99 eos/hpf | Symptom score | 17 → 9 | 17 → 10 | Abstract |

Fluticasone multi-dose inhaler puffed into the mouth and swallowed

Budesonide respule (aqueous solution) mixed into a slurry with sucralose and swallowed

Budesonide respule nebulized and swallowed

Budesonide viscous suspension; outcomes presented for the “high dose” groups only (dosing was at three levels as determined by age; for 2–9 yo, 0.35 mg/d, 1.4 mg/d, or 2.8 mg/d were the low, medium and high doses; for 10–18 yo, the doses were 0.5 mg/d, 2 mg/d, and 4mg/d, respectively)

Mepolizumab; for Assa’ad, 2011, data presented for high dose vs low dose

Reslizumab; data are presented for high dose vs placebo

Omalizumab; data for proximal eosinophil counts presented

Chemoattractant receptor-homologous molecule expressed on Th2 cells antagonist (OC000459)

The first treatment trial in EoE randomized 21 children to receive swallowed fluticasone 880 ucg/d divided twice daily and 15 children to receive placebo for 3 months.99 Fifty percent of patients receiving fluticasone achieved the primary endpoint of complete histologic remission (≤ 1 eos/hpf) compared to just 9% of patients receiving placebo, but only the symptom of vomiting was noted to improve. A similarly designed study was recently conducted in adults where 21 patients received fluticasone 1760 ucg/d divided twice daily and 15 received placebo for 6 weeks.100 The primary endpoint of a >90% decrease in the mean eosinophil count was reached by 62% treated with fluticasone and 0% of the placebo group. Improvement in dysphagia was not significantly different between groups.

An approach to topical steroids using swallowed budesonide was developed in children to simplify medication administration.97, 104 Here, a budesonide aqueous solution was mixed with a sugar substitute (sucralose) to make a sweet and easy to swallow slurry, termed “oral viscous budesonide” (OVB). A subsequent clinical trial randomized 15 children to 1–2 mg of OVB/d depending on height and 9 children to placebo for 3 months. The primary outcome of histologic response (≤ 6 eos/hpf) was achieved by 87% in the treatment arm and none in the placebo group. The mean symptom score also improved in OVB compared to placebo. A larger RCT in children examining a muco-adherent formulation of a budesonide suspension also showed an outstanding histologic response, but both study arms had substantially improved symptoms, highlighting a lack of correlation between symptoms and histology of EoE that has been repeatedly observed.87 The efficacy of budesonide has also been confirmed in adults. One study randomized patients to a protocol where they swallowed budesonide droplets that had been aerosolized by a nebulizer and showed that histology and symptoms substantially improved compared to placebo after only 15 days.102 A recent study that compared OVB with nebulized/swallowed budesonide found that OVB was more effective for improving histology, but that symptoms again improved in both study groups.103 There are no commercial preparations of OVB yet available in the U.S., so if this medication option is chosen, patients must be instructed on how to mix the aqueous budesonide solution with a sugar substitute.

Topical steroids have been found to be well tolerated. There have been no reports of adrenal suppression associated with the initial course of topical steroid administration,87, 100, 101, 103 but longer term safety data are needed for a variety of potential steroid-related side effects.1 The rate of candidal esophagitis with topical steroids has ranged from 0–32% in prospective studies, though the majority of these cases were asymptomatic and detected incidentally at follow-up endoscopy.59, 87, 99–103 Herpes esophagitis has also been reported as a rare complication.105

If topical steroids are stopped after the initial treatment course, the majority of patients will have symptom recurrence. This is a theme that is repeated for all treatment modalities: because EoE is chronic, symptoms and histologic findings tend to recur after discontinuing treatment. One study investigating disease recurrence after topical steroid use contacted 32 adult patients who had previously been treated with 6 weeks of swallowed fluticasone.106 At a mean duration of 3.3 years of follow-up, 91% reported recurrent dysphagia, with a mean time to symptom recurrence of 9 months, and 69% required repeat fluticasone treatment. To date, there has been one trial of maintenance therapy in EoE. In this study, subjects who previously responded to nebulized/swallowed budesonide102 were randomized to continue low-dose budesonide at 0.5 mg/d or to receive placebo for a year.107 Histologic recurrence was universal in the placebo group compared with the budesonide group (100% vs 50%), and symptom recurrence was also more common (64% vs 36%). These data raise the question of whether maintenance therapy should be considered in patients with EoE.

Systemic corticosteroids

Systemic corticosteroids were the first of the steroid therapies used for EoE.3, 108 A pediatric case series showed that treatment with methylprednisolone led to either complete or marked symptom improvement in 19 of 20 children with a mean time to response of just 8 days.109 However, 6 months post-treatment, the majority of children had recurrent symptoms and eosinophilia. In the one RCT of systemic steroids, prednisone was compared to swallowed fluticasone in 80 children.59 Prednisone was equivalent to fluticasone for decreasing esophageal eosinophilia and improving the presenting symptom, but was associated with more adverse events. Because of this result and the concern about risks of long-term use, systemic steroids are typically reserved for second-line therapy in cases where topical steroids are not effective, or first-line therapy primarily in children with severe symptoms, malnutrition, or feeding intolerance where a very rapid response may be needed or topical steroid administration is logistically difficult.

Leukotriene antagonists and mast cell stabilizers

Because of the presumed immune-mediated etiology of EoE, allergy medications are a theoretically attractive option for EoE treatment but few data support this approach. The initial report of treatment with the leukotriene antagonist montelukast showed efficacy in 6 of 8 adults, but with a dose range that averaged 20–40 mg/d and was associated with nausea and vomiting.110 Two recent studies using standard dosing, one in children111 and one in adults112 had mixed results, with 3 of 8 children and no adults responding. There have also been two studies which assessed cysteinyl leukotrienes and leukotriene synthesis enzyme staining, respectively, in esophageal biopsies and did not find differential levels in EoE cases compared with controls.113, 114 For these reasons, montelukast is not routinely recommended for use and is reserved as a second line agent in selected cases.

Despite mast cells being increasingly recognized as critical in the pathogenesis of EoE,24–26, 115 mast cell stabilizers such as cromolyn sodium are not felt to be effective based on case series data and are not recommended for routine use in EoE.9

Immunomodulators

Use of immunomodulators such as azathioprine or 6MP has been reported in a single case series of 3 steroid-refractors adults with EoE.116 In all cases, subjects were treated with azathioprine (2–2.5 mg/kg/d), had an excellent response in esophageal eosinophilia, and relapsed after treatment was discontinued. After relapse, they were successfully treated with corticosteroids and maintained on azathioprine with good success. While intriguing, the data are as yet too limited to recommend an “induce and maintain” strategy analogous to IBD, and routine use of immunomodulators is not recommended in EoE, particularly due to potential side effects.

Biologics

With the rapid increase in knowledge about the pathogenesis of EoE, new biologic therapies have been developed to target key factors in EoE pathways. The best studied of these agents are antibodies to IL-5, a central cytokine in eosinophil physiology and EoE pathophysiology. A case series of 4 patients treated with anti-IL-5 (mepolizumab) suggested this approach had potential for improving symptoms and reducing levels of esophageal eosinophilia.117 Since that time, there have been 3 placebo-controlled RCTs (see Table 2).88, 118, 119 In all three studies, there was a mild to moderate decrease in eosinophil counts, but strict endpoints of resolution of esophageal eosinophilia were not met. Further, in the largest of the studies which examined the anti-IL-5 antibody reslizumab,88 symptoms improved equally in both the treatment and placebo group. These agents are still considered experimental, not yet commercially available, and are not recommend for routine use in EoE.

Omalizumab, an antibody to IgE, was studied in EoE given that it has efficacy in other atopic conditions such as allergic asthma and chronic urticaria. In this investigation, 16 EoE patients were randomized to receive omalizumab, and 14 received placebo.120 After a 16 week treatment period, eosinophil counts and symptoms did not improve in either the treatment or placebo arm. This agent is not recommended for use in EoE at this time.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) has been shown to be increased in esophageal biopsies from patients with EoE, suggesting a possible clinical utility for anti-TNF agents.121 However, in a case series of 3 adults with steroid-refractory EoE who were treated with infliximab, there was no substantial improvement in either symptoms or histology.122 This agent is also not recommended for use in EoE at this time.

Future pharmacologic agents

Novel therapeutic agents for treatment of EoE are actively being sought, and monoclonal antibodies such as anti-IL-13 and anti-eotaxin-3 are under development.1 Improved formulations and delivery methods for administering current topical corticosteroids are also under investigation.87, 123 Finally, a new medication class, an antagonist to the chemoattractant receptor-homologous molecule expressed on Th2 cells (CRTH2) has recently been found to result in a mild improvement in esophageal eosinophilia, and further studies will be needed to assess its clinical utility.124

Dietary therapy

Because food allergens may contribute to the pathogenesis of EoE in many patients,21 identifying and avoiding dietary allergens is appealing to target an underlying etiology of EoE. There are three general strategies for dietary elimination in EoE: elemental diet, six-food elimination diet, and targeted elimination diet. The specific approach often depends on local allergy and nutritional expertise and support, and patient and family preferences, resources, and motivation. If a patient decides to embark on dietary therapy, referral to an allergist may be considered to determine whether specific testing for food allergies is needed and by what modality, to help manage the dietary elimination and reintroduction process, and to fully evaluate and treat the patient for potential concomitant atopic disorders. However, outside of dietary therapy and associated allergic conditions, not every EoE patient will require evaluation by an allergist.1

An elemental formula comprised of amino-acids, basic carbohydrates, and medium chain triglycerides is allergen free and has been shown to be extremely effective for treatment of EoE in children. The first report of this approach showed that all 10 children treated had either resolution or improvement in symptoms and esophageal eosinophilia within 2–6 weeks.7 A larger study of 51 children with EoE treated with an elemental diet showed that 49 (96%) had a marked improvement in symptoms and esophageal eosinophilia, with an average time to symptom improvement of only 9 days.125 This response rate has subsequently been confirmed in other large series.9, 126 Only one small study has examined use of an elemental diet in adults with EoE, and this showed a 50% partial response rate, perhaps due to difficulties with compliance.127

In practice, use of an elemental diet can be difficult; formulas are expensive, unpalatable and may need to be administered via an enteral feeding tube, extremely restrictive, and can adversely impact quality of life. Because of these issues, an empiric six-food elimination diet (SFED) was developed to increase compliance and acceptability. This diet eliminates 6 of the most common food allergens: milk, eggs, wheat, soy, seafood, and nuts. It was first studied on a retrospective basis, and compared very favorably to an elemental diet with 74% of subjects having a histologic response to ≤ 10 eos/hpf, and 95% having a symptomatic response.128 In addition, this approach was found to be more palatable than the elemental diet. Subsequent work from the same group showed that after food reintroduction, the most common food trigger was milk, with wheat, egg, and soy being less common.129 Recent work in children has confirmed this response rate,126 and a prospective study of SFED in adults with EoE now shows efficacy as well.130 In this study, 50 subjects were treated with SFED, 64% had a complete histologic response (≤ 5 eos/hpf) and 94% had symptom improvement. After a food reintroduction protocol, wheat and milk were the most commonly identified allergens. Similar results have been reported in abstract form in another study of adults treated with SFED.131

The last approach to dietary therapy is a targeted diet where food allergens identified on allergy testing are eliminated. While it is beyond the scope of this paper to fully review the various methods of testing for food allergies, it can be difficult to reliably detect specific food allergies with current testing modalities, and the best approach is still debated.1, 30, 126, 129, 130, 132 With that caveat, data also support the use of targeted elimination. An initial study performed both skin prick and atopy patch testing on 26 children with EoE.133 After identification and elimination of potential culprit allergens, 24 of the subjects had a complete or partial response to therapy, with milk and egg being the most commonly detected allergens by prick testing, and wheat and soy being the most common with patch testing. While subsequent studies have showed success with this approach, the response rates have been closer to the 55–75% range in children,9, 126, 134 and potentially lower in adults.135, 136

Endoscopic dilation

The final treatment approach for EoE, used in patients with esophageal strictures or narrow caliber esophagus and symptoms of dysphagia, is esophageal dilation. While the techniques, typically wire-guided bougie dilation or through-the-scope (TTS) balloon dilation, are familiar to many gastroenterologists, special comment on the application of dilation to EoE is warranted. When dilation was first described in EoE, multiple case series raised substantial safety concerns by reporting high rates of complications such as esophageal perforation, esophageal rents, and hospitalization for post-procedural chest pain.137–142 For example, in the largest of these studies, 3 of 36 patients undergoing esophageal dilation had a perforation (8%) and 1 had emesis-induced Boerhaave’s syndrome.142 As a result of this, and in the context of observed mucosal fragility in EoE,139 the first consensus guidelines for EoE recommended a very cautious approach to dilation only after institution medical or dietary therapy for this condition.

Over the past several years, however, larger studies have reported on a more extensive and carefully characterized experience with esophageal dilation in EoE,143–149 and there are now two systematic reviews on dilation for patients with EoE.150, 151 While these studies are retrospective, almost 500 patients, representing nearly 1000 dilations, have cumulatively been reported and there have been 3 esophageal perforations. This rate (0.3%) is not dissimilar to that quoted for standard endoscopy with dilation in a non-EoE population.152 In addition, the large majority of the perforations that have been reported to date have been managed non-operatively.

In addition to being safer than initially believed, esophageal dilation is also effective in improving symptoms of dysphagia even though it has no impact on underlying eosinophilic inflammation.147, 148, 150, 151 In one large study of esophageal dilation, a subgroup of 42 patients who were treated with dilation alone were contacted and symptoms were assessed.147 Post-dilation, 81% were symptom-free at 3 months, 46% were symptom free at 1 year, and 41% were symptom free at 2 years. Importantly, this study also noted that 74% of patients reported some degree of retrosternal pain after the endoscopy, and this was described as moderate in 21% and severe in 17%. Nevertheless, all of the patients who were questioned found the procedure to be acceptable and would have repeat dilation if indicated.

Taken in sum, these data show that esophageal dilation can be a safe and effective treatment for EoE patients with strictures or narrow caliber esophagus, and its use is now supported by the updated consensus recommendations.1 The typical approach is to defer esophageal dilation at the baseline (diagnostic) endoscopy unless there is an area of critical narrowing, in favor of performing dilation during the follow-up endoscopy performed to assess response to medical or dietary therapy. The choice of dilation as the initial therapy in all cases is still controversial. There are few data to guide dilator choice in EoE, and there are proponents of both bougie and TTS balloon dilation.148, 153 Balloon dilation offers the theoretic advantages of reduced shear force and ability to accurately determine esophageal caliber, directly visualize the dilation, and stop dilation once a non-transmural esophageal tear is noted without having to reintroduce the endoscope after each dilator size increase (Figure 3). In contrast, bougies allow dilation of the entire esophageal with one pass, can provide a tactile sensation of resistance to the endoscopist, and are less expensive. Because further studies are needed to determine the safest and most effective dilation approach, it remains prudent to approach esophageal dilation in EoE judiciously and discuss the risks and benefits, including the high likelihood of post-procedural chest discomfort, with patients prior to endoscopy.

Figure 3.

Endoscopic dilation for treatment of EoE. A through-the-scope balloon dilator has been inflated to a diameter of 12mm in a patient with EoE and a narrow caliber esophagus (A). When the balloon is deflated, a longitudinal rent is noted, indicating good dilation effect (B).

Conclusions

Over the past two decades, EoE has made a remarkable transformation from a rarely seen, case-reportable diagnosis to a commonly encountered condition in GI practice. Because no individual clinical, endoscopic, or histologic feature alone is pathognomonic, EoE is a clinicopathologic condition; in order to diagnose EoE all features must be considered together. The most recent consensus guidelines state that EoE is diagnosed when there are symptoms of esophageal dysfunction, ≥ 15 eos/hpf on esophageal biopsy, and when other causes of esophageal eosinophilia, including PPI-REE, are excluded. Once the diagnosis is confirmed, the three main treatment options are drugs, diet, and dilation.

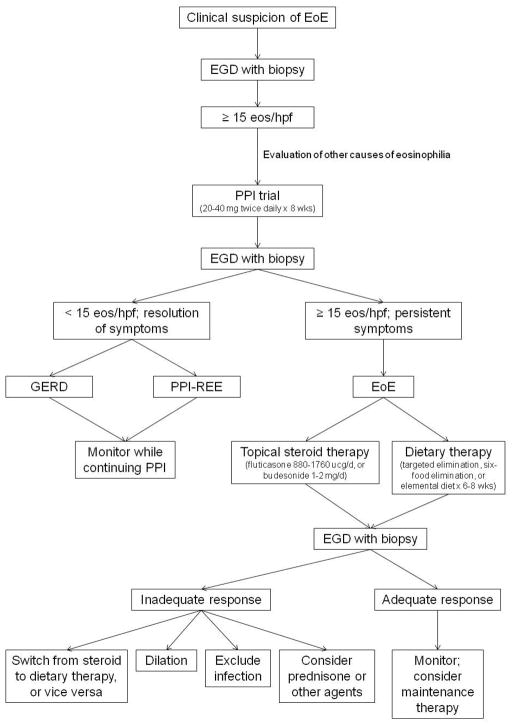

Figure 4 depicts a practical approach to diagnosis and treatment of EoE and summarizes the concepts discussed in this review. When EoE is suspected on a clinical basis, EGD is performed for initial evaluation. To maximize diagnostic sensitivity, at least 2–4 biopsies should be taken from both the proximal and distal esophagus regardless of the endoscopic appearance of the esophagus. If eosinophilia, in most cases with ≥ 15 eos/hpf, is noted on biopsy, EoE can be suspected, but not yet formally diagnosed. First, other conditions that cause esophageal eosinophilia must be excluded, and then a PPI trial, typically with twice daily therapy for 8 weeks, must be instituted to evaluate for the possibility of PPI-REE. At repeat endoscopy, if symptoms and esophageal eosinophilia have improved substantially or resolved, then the patient does not have EoE as it is currently defined. Further clinical evaluation can be performed as needed to determine if the patient has GERD. If there is not evidence of GERD, PPI-REE can be diagnosed. Given that the patient has clinically improved and that there are few data supporting the next step in management, the PPI is typically continued at the lowest dose that effectively controls symptoms and the patient is monitored. This part of the algorithm is likely to evolve in the future as more is learned about PPI-REE. In contrast, at repeat endoscopy if symptoms and esophageal eosinophilia persist with levels still ≥ 15 eos/hpf, then EoE is formally diagnosed. First line treatment can either be with topical/swallowed corticosteroids or with dietary elimination. If steroids are chosen, the dose range is typically 880–1760 ucg/d of fluticasone or 1–2 mg/d of budesonide mixed with 5g of sucralose, both administered twice daily with the exact dose determined by patient age or size. If dietary therapy is chosen, depending on patient preference, local expertise, allergy testing results, and illness severity, options include targeted elimination, empiric six-food elimination (eliminating milk, eggs, wheat, soy, seafood, and nuts), and elemental diets. Both pharmacologic and dietary therapies are initially prescribed for 6–8 weeks, and then follow-up endoscopy is performed. If there is a substantial improvement in symptoms and esophageal eosinophilia, then maintenance therapy can be considered and patients can be monitored. If there is not an adequate clinical response, then additional therapies can be considered. If steroids were chosen initially, then dietary elimination could be considered, and vice versa. If neither of these options is successful, there are few data to guide subsequent therapy and choices must be tailored to the individual patient. Endoscopic dilation could be considered if there are critical strictures, esophageal narrowing, or persistent fixed rings that are thought to explain dysphagia. Additionally, superimposed infections, such as candidal esophagitis, should be excluded. Systemic steroids could be considered if symptoms are severe or need to be treated quickly because of malnutrition. In select cases, other agents can also be considered. Looking to the future, there is hope that biomarkers will be able to make the diagnostic process less invasive and potentially individualize initial treatment choices. As new studies are conducted and additional data accumulate, the algorithm for diagnosis and treatment of EoE will continue to evolve.

Figure 4.

An approach to diagnosis and management of EoE.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH award number 1K23 DK090073-01.

Footnotes

Disclosures: No conflicts of interested pertaining to this manuscript. Dr. Dellon has received research support from AstraZeneca, Meritage Pharma, Olympus, NIH, ACG, and AGA. Dr. Dellon has been a consultant for Oncoscope.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, Atkins D, Attwood SE, Bonis PA, Burks AW, Chehade M, Collins MH, Dellon ES, Dohil R, Falk GW, Gonsalves N, Gupta SK, Katzka DA, Lucendo AJ, Markowitz JE, Noel RJ, Odze RD, Putnam PE, Richter JE, Romero Y, Ruchelli E, Sampson HA, Schoepfer A, Shaheen NJ, Sicherer SH, Spechler S, Spergel JM, Straumann A, Wershil BK, Rothenberg ME, Aceves SS. Eosinophilic esophagitis: Updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:3–20.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landres RT, Kuster GG, Strum WB. Eosinophilic esophagitis in a patient with vigorous achalasia. Gastroenterology. 1978;74:1298–1301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Picus D, Frank PH. Eosinophilic esophagitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1981;136:1001–3. doi: 10.2214/ajr.136.5.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee RG. Marked eosinophilia in esophageal mucosal biopsies. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985;9:475–9. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198507000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Attwood SE, Smyrk TC, Demeester TR, Jones JB. Esophageal eosinophilia with dysphagia. A distinct clinicopathologic syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:109–16. doi: 10.1007/BF01296781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Straumann A, Spichtin HP, Bernoulli R, Loosli J, Vogtlin J. Idiopathic eosinophilic esophagitis: a frequently overlooked disease with typical clinical aspects and discrete endoscopic findings. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1994;124:1419–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelly KJ, Lazenby AJ, Rowe PC, Yardley JH, Perman JA, Sampson HA. Eosinophilic esophagitis attributed to gastroesophageal reflux: improvement with an amino acid-based formula. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1503–12. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90637-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noel RJ, Putnam PE, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilic esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:940–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200408263510924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liacouras CA, Spergel JM, Ruchelli E, Verma R, Mascarenhas M, Semeao E, Flick J, Kelly J, Brown-Whitehorn T, Mamula P, Markowitz JE. Eosinophilic esophagitis: a 10-year experience in 381 children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:1198–206. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00885-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Straumann A, Simon HU. Eosinophilic esophagitis: escalating epidemiology? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:418–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hruz P, Straumann A, Bussmann C, Heer P, Simon HU, Zwahlen M, Beglinger C, Schoepfer AM. Escalating incidence of eosinophilic esophagitis: A 20-year prospective, population-based study in Olten County, Switzerland. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:1349–1350. e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kapel RC, Miller JK, Torres C, Aksoy S, Lash R, Katzka DA. Eosinophilic esophagitis: a prevalent disease in the United States that affects all age groups. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1316–21. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dellon ES, Gibbs WB, Fritchie KJ, Rubinas TC, Wilson LA, Woosley JT, Shaheen NJ. Clinical, endoscopic, and histologic findings distinguish eosinophilic esophagitis from gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1305–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prasad GA, Alexander JA, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Smyrk TC, Elias RM, Locke GR, 3rd, Talley NJ. Epidemiology of eosinophilic esophagitis over three decades in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1055–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sealock RJ, Rendon G, El-Serag HB. Systematic review: the epidemiology of eosinophilic oesophagitis in adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:712–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ronkainen J, Talley NJ, Aro P, Storskrubb T, Johansson SE, Lind T, Bolling-Sternevald E, Vieth M, Stolte M, Walker MM, Agreus L. Prevalence of oesophageal eosinophils and eosinophilic oesophagitis in adults: The population-based Kalixanda study. Gut. 2007;56:615–20. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.107714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prasad GA, Talley NJ, Romero Y, Arora AS, Kryzer LA, Smyrk TC, Alexander JA. Prevalence and Predictive Factors of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Patients Presenting With Dysphagia: A Prospective Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2627–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mackenzie SH, Go M, Chadwick B, Lamphier S, Thomas K, Fang J, Peterson K. Prospective analysis of eosinophilic esophagitis in patients presenting with dysphagia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:S47 (A18). doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Veerappan GR, Perry JL, Duncan TJ, Baker TP, Maydonovitch C, Lake JM, Wong RK, Osgard EM. Prevalence of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in an Adult Population Undergoing Upper Endoscopy: A Prospective Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:420–426. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spergel JM, Book WM, Mays E, Song L, Shah SS, Talley NJ, Bonis PA. Variation in prevalence, diagnostic criteria, and initial management options for eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases in the United States. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:300–6. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181eb5a9f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rothenberg ME. Biology and treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1238–49. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blanchard C, Wang N, Stringer KF, Mishra A, Fulkerson PC, Abonia JP, Jameson SC, Kirby C, Konikoff MR, Collins MH, Cohen MB, Akers R, Hogan SP, Assa’ad AH, Putnam PE, Aronow BJ, Rothenberg ME. Eotaxin-3 and a uniquely conserved gene-expression profile in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:536–47. doi: 10.1172/JCI26679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aceves SS, Newbury RO, Dohil R, Bastian JF, Broide DH. Esophageal remodeling in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:206–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aceves SS, Chen D, Newbury RO, Dohil R, Bastian JF, Broide DH. Mast cells infiltrate the esophageal smooth muscle in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, express TGF-beta1, and increase esophageal smooth muscle contraction. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:1198–204. e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abonia JP, Blanchard C, Butz BB, Rainey HF, Collins MH, Stringer K, Putnam PE, Rothenberg ME. Involvement of mast cells in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:140–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dellon ES, Chen X, Miller CR, Fritchie KJ, Rubinas TC, Woosley JT, Shaheen NJ. Tryptase staining of mast cells may differentiate eosinophilic esophagitis from gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:264–71. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mishra A, Hogan SP, Brandt EB, Rothenberg ME. An etiological role for aeroallergens and eosinophils in experimental esophagitis. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:83–90. doi: 10.1172/JCI10224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blanchard C, Stucke EM, Burwinkel K, Caldwell JM, Collins MH, Ahrens A, Buckmeier BK, Jameson SC, Greenberg A, Kaul A, Franciosi JP, Kushner JP, Martin LJ, Putnam PE, Abonia JP, Wells SI, Rothenberg ME. Coordinate interaction between IL-13 and epithelial differentiation cluster genes in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Immunol. 2010;184:4033–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rothenberg ME, Spergel JM, Sherrill JD, Annaiah K, Martin LJ, Cianferoni A, Gober L, Kim C, Glessner J, Frackelton E, Thomas K, Blanchard C, Liacouras C, Verma R, Aceves S, Collins MH, Brown-Whitehorn T, Putnam PE, Franciosi JP, Chiavacci RM, Grant SF, Abonia JP, Sleiman PM, Hakonarson H. Common variants at 5q22 associate with pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Nat Genet. 2010;42:289–91. doi: 10.1038/ng.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, Gupta SK, Justinich C, Putnam PE, Bonis P, Hassall E, Straumann A, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1342–63. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dellon ES, Aderoju A, Woosley JT, Sandler RS, Shaheen NJ. Variability in diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis: A systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2300–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sperry SL, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. Toward uniformity in the diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE): the effect of guidelines on variability of diagnostic criteria for EoE. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:824–32. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.10. quiz 833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peery AF, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. Practice patterns for the evaluation and treatment of eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:1373–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spechler SJ, Genta RM, Souza RF. Thoughts on the complex relationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease and eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1301–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Putnam PE. Evaluation of the Child who has Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2009;29:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Straumann A. Clinical Evaluation of the Adult who has Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2009;29:11–8. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Desai TK, Stecevic V, Chang CH, Goldstein NS, Badizadegan K, Furuta GT. Association of eosinophilic inflammation with esophageal food impaction in adults. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:795–801. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)00313-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kerlin P, Jones D, Remedios M, Campbell C. Prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in adults with food bolus obstruction of the esophagus. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:356–61. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000225590.08825.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sperry SL, Crockett SD, Miller CB, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. Esophageal foreign-body impactions: epidemiology, time trends, and the impact of the increasing prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:985–91. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spergel JM, Brown-Whitehorn TF, Beausoleil JL, Franciosi J, Shuker M, Verma R, Liacouras CA. 14 years of eosinophilic esophagitis: clinical features and prognosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:30–6. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181788282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Foroutan M, Norouzi A, Molaei M, Mirbagheri SA, Irvani S, Sadeghi A, Derakhshan F, Tavassoli S, Besharat S, Zali M. Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Patients with Refractory Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:28–31. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0706-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garcia-Compean D, Gonzalez Gonzalez JA, Marrufo Garcia CA, Flores Gutierrez JP, Barboza Quintana O, Galindo Rodriguez G, Mar Ruiz MA, de Leon Valdez D, Jaquez Quintana JO, Maldonado Garza HJ. Prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in patients with refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms: A prospective study. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:204–8. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poh CH, Gasiorowska A, Navarro-Rodriguez T, Willis MR, Hargadon D, Noelck N, Mohler J, Wendel CS, Fass R. Upper GI tract findings in patients with heartburn in whom proton pump inhibitor treatment failed versus those not receiving antireflux treatment. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rodrigo S, Abboud G, Oh D, Demeester SR, Hagen J, Lipham J, Demeester TR, Chandrasoma P. High intraepithelial eosinophil counts in esophageal squamous epithelium are not specific for eosinophilic esophagitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:435–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Franciosi JP, Tam V, Liacouras CA, Spergel JM. A case-control study of sociodemographic and geographic characteristics of 335 children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:415–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sperry SLW, Woosley JT, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. Influence of race and gender on the presentation of eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:215–21. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bohm M, Malik Z, Sebastiano C, Thomas R, Gaughan J, Kelsen S, Richter JE. Mucosal Eosinophilia: Prevalence and Racial/Ethnic Differences in Symptoms and Endoscopic Findings in Adults Over 10 Years in an Urban Hospital. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011 doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31823d3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sharma HP, Mansoor DK, Sprunger AC, Zalos K, Taylor H, Martin X, Mikhail IK. Racial disparities in the presentation of pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:AB110. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Assa’ad AH, Putnam PE, Collins MH, Akers RM, Jameson SC, Kirby CL, Buckmeier BK, Bullock JZ, Collier AR, Konikoff MR, Noel RJ, Guajardo JR, Rothenberg ME. Pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: an 8-year follow-up. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:731–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chehade M, Aceves SS. Food allergy and eosinophilic esophagitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;10:231–7. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e328338cbab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Penfield JD, Lang DM, Goldblum JR, Lopez R, Falk GW. The Role of Allergy Evaluation in Adults With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:22–7. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181a1bee5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roy-Ghanta S, Larosa DF, Katzka DA. Atopic Characteristics of Adult Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:531–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim HP, Vance RB, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. The Prevalence and Diagnostic Utility of Endoscopic Features of Eosinophilic Esophagitis: A Meta-Analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.04.019. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peery AF, Cao H, Dominik R, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. Variable reliability of endoscopic findings with white-light and narrow-band imaging for patients with suspected eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:475–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moy N, Heckman MG, Gonsalves N, Achem SR, Hirano I. Inter-observer agreement on endoscopic esopahgeal findings in eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(Suppl 1):S236 (Ab Sa1146). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saffari H, Peterson KA, Fang JC, Teman C, Gleich GJ, Pease LF., 3rd Patchy eosinophil distributions in an esophagectomy specimen from a patient with eosinophilic esophagitis: Implications for endoscopic biopsy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dellon ES, Speck O, Woodward K, Woosley JT, Shaheen NJ. The patchy nature of esophageal eosinophilia in eosinophilic esophagitis: Insights from pathology samples from a clinical trial. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(Suppl 2):Ab Su1129. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gonsalves N, Policarpio-Nicolas M, Zhang Q, Rao MS, Hirano I. Histopathologic variability and endoscopic correlates in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:313–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schaefer ET, Fitzgerald JF, Molleston JP, Croffie JM, Pfefferkorn MD, Corkins MR, Lim JD, Steiner SJ, Gupta SK. Comparison of oral prednisone and topical fluticasone in the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis: a randomized trial in children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:165–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shah A, Kagalwalla AF, Gonsalves N, Melin-Aldana H, Li BU, Hirano I. Histopathologic variability in children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:716–21. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Collins MH. Histopathologic features of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2008;18:59–71. viii–ix. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Odze RD. Pathology of eosinophilic esophagitis: what the clinician needs to know. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:485–90. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dellon ES, Fritchie KJ, Rubinas TC, Woosley JT, Shaheen NJ. Inter- and intraobserver reliability and validation of a new method for determination of eosinophil counts in patients with esophageal eosinophilia. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1940–9. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1005-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ngo P, Furuta GT, Antonioli DA, Fox VL. Eosinophils in the esophagus--peptic or allergic eosinophilic esophagitis? Case series of three patients with esophageal eosinophilia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1666–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dranove JE, Horn DS, Davis MA, Kernek KM, Gupta SK. Predictors of response to proton pump inhibitor therapy among children with significant esophageal eosinophilia. J Pediatr. 2009;154:96–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sayej WN, Patel R, Baker RD, Tron E, Baker SS. Treatment With High-dose Proton Pump Inhibitors Helps Distinguish Eosinophilic Esophagitis From Noneosinophilic Esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;49:393–9. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31819c4b3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Molina-Infante J, Ferrando-Lamana L, Ripoll C, Hernandez-Alonso M, Mateos JM, Fernandez-Bermejo M, Duenas C, Fernandez-Gonzalez N, Quintana EM, Gonzalez-Nunez MA. Esophageal Eosinophilic Infiltration Responds to Proton Pump Inhibition in Most Adults. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:110–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Peterson KA, Thomas KL, Hilden K, Emerson LL, Wills JC, Fang JC. Comparison of esomeprazole to aerosolized, swallowed fluticasone for eosinophilic esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1313–9. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0859-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Moawad FJ, Dias JA, Veerappan GR, Baker T, Maydonovitch CL. Comparison of Aerosolized Swallowed Fluticasone to Esomeprazole for the Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011:S12 (AB 30). doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dohil R, Newbury RO, Aceves S. Transient PPI Responsive Esophageal Eosinophilia May Be a Clinical Sub-phenotype of Pediatric Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:1413–9. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1991-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cheng E, Zhang X, Huo X, Yu C, Zhang Q, Wang DH, Spechler SJ, Souza RF. Omeprazole blocks eotaxin-3 expression by oesophageal squamous cells from patients with eosinophilic oesophagitis and GORD. Gut. 2012 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Aceves SS, Newbury RO, Dohil MA, Bastian JF, Dohil R. A symptom scoring tool for identifying pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis and correlating symptoms with inflammation. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;103:401–6. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60359-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.von Arnim U, Wex T, Rohl FW, Neumann H, Kuster D, Weigt J, Monkemuller K, Malfertheiner P. Identification of clinical and laboratory markers for predicting eosinophilic esophagitis in adults. Digestion. 2011;84:323–7. doi: 10.1159/000331142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yoo H, Kang D, Katz AJ, Lauwers GY, Nishioka NS, Yagi Y, Tanpowpong P, Namati J, Bouma BE, Tearney GJ. Reflectance confocal microscopy for the diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis: a pilot study conducted on biopsy specimens. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:992–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Safdarian N, Liu Z, Zhou X, Appelman H, Nostrant TT, Wang TD, Wang ET. Quantifying human eosinophils using three-dimensional volumetric images collected with multiphoton fluorescence microscopy. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:15–20. e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kwiatek MA, Hirano I, Kahrilas PJ, Rothe J, Luger D, Pandolfino JE. Mechanical properties of the esophagus in eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:82–90. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Protheroe C, Woodruff SA, de Petris G, Mukkada V, Ochkur SI, Janarthanan S, Lewis JC, Pasha S, Lunsford T, Harris L, Sharma VK, McGarry MP, Lee NA, Furuta GT, Lee JJ. A novel histologic scoring system to evaluate mucosal biopsies from patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:749–755. e11. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kephart GM, Alexander JA, Arora AS, Romero Y, Smyrk TC, Talley NJ, Kita H. Marked deposition of eosinophil-derived neurotoxin in adult patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:298–307. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dellon ES, Chen X, RMC, Woosley JT, Shaheen NJ. Diagnostic utility of major basic protein and eotaxin-3 staining in the esophageal epithelium for differentiation of eosinophilic esophagitis from gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(Suppl 2):S15 (Ab 36). [Google Scholar]

- 80.Blanchard C, Stucke EM, Rodriguez-Jimenez B, Burwinkel K, Collins MH, Ahrens A, Alexander ES, Butz BK, Jameson SC, Kaul A, Franciosi JP, Kushner JP, Putnam PE, Abonia JP, Rothenberg ME. A striking local esophageal cytokine expression profile in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:208–17. 217 e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gupta SK, Fitzgerald JF, Kondratyuk T, HogenEsch H. Cytokine expression in normal and inflamed esophageal mucosa: a study into the pathogenesis of allergic eosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;42:22–6. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000188740.38757.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Konikoff MR, Blanchard C, Kirby C, Buckmeier BK, Cohen MB, Heubi JE, Putnam PE, Rothenberg ME. Potential of blood eosinophils, eosinophil-derived neurotoxin, and eotaxin-3 as biomarkers of eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1328–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Subbarao G, Rosenman MB, Ohnuki L, Georgelas A, Davis M, Fitzgerald JF, Molleston JP, Croffie JM, Pfefferkorn MD, Corkins MR, Lim JR, Steiner SJ, Schaefer E, Gleich GJ, Gupta SK. Exploring potential noninvasive biomarkers in eosinophilic esophagitis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53:651–8. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318228cee6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Blanchard C, Mingler MK, Vicario M, Abonia JP, Wu YY, Lu TX, Collins MH, Putnam PE, Wells SI, Rothenberg ME. IL-13 involvement in eosinophilic esophagitis: transcriptome analysis and reversibility with glucocorticoids. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:1292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hirano I. Therapeutic End Points in Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Is Elimination of Esophageal Eosinophils Enough? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pentiuk S, Putnam PE, Collins MH, Rothenberg ME. Dissociation between symptoms and histological severity in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:152–60. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31817f0197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gupta SK, Collins MH, Lewis JD, Farber RH. Efficacy and Safety of Oral Budesonide Suspension (OBS) in Pediatric Subjects With Eosinophilic Esophagitis (EoE): Results From the Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled PEER Study. Gastroenterology. 2011;140 (Suppl 1):S179. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Spergel JM, Rothenberg ME, Collins MH, Furuta GT, Markowitz JE, Fuchs G, 3rd, O’Gorman MA, Abonia JP, Young J, Henkel T, Wilkins HJ, Liacouras CA. Reslizumab in children and adolescents with eosinophilic esophagitis: Results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:456–63. 463.e1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dellon ES, Woodward K, Speck O, Hores J, Woosley JT, Shaheen NJ. Symptoms do not correlate with histologic response in eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(Suppl 2):AB Su1130. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Straumann A. Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Diet, Drugs, or Dilation? Gastroenterology. 2012 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shah A, Hirano I. Treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis: drugs, diet, or dilation? Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2007;9:181–8. doi: 10.1007/s11894-007-0016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Faubion WA, Jr, Perrault J, Burgart LJ, Zein NN, Clawson M, Freese DK. Treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis with inhaled corticosteroids. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998;27:90–3. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199807000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Teitelbaum JE, Fox VL, Twarog FJ, Nurko S, Antonioli D, Gleich G, Badizadegan K, Furuta GT. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children: immunopathological analysis and response to fluticasone propionate. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1216–25. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Arora AS, Perrault J, Smyrk TC. Topical corticosteroid treatment of dysphagia due to eosinophilic esophagitis in adults. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:830–5. doi: 10.4065/78.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Noel RJ, Putnam PE, Collins MH, Assa’ad AH, Guajardo JR, Jameson SC, Rothenberg ME. Clinical and immunopathologic effects of swallowed fluticasone for eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:568–75. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00240-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Remedios M, Campbell C, Jones DM, Kerlin P. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults: clinical, endoscopic, histologic findings, and response to treatment with fluticasone propionate. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Aceves SS, Bastian JF, Newbury RO, Dohil R. Oral Viscous Budesonide: A Potential New Therapy for Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Children. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2271–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lucendo AJ, Pascual-Turrion JM, Navarro M, Comas C, Castillo P, Letran A, Caballero MT, Larrauri J. Endoscopic, bioptic, and manometric findings in eosinophilic esophagitis before and after steroid therapy: a case series. Endoscopy. 2007;39:765–71. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Konikoff MR, Noel RJ, Blanchard C, Kirby C, Jameson SC, Buckmeier BK, Akers R, Cohen MB, Collins MH, Assa’ad AH, Aceves SS, Putnam PE, Rothenberg ME. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fluticasone propionate for pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1381–91. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Alexander JA, Jung KW, Arora AS, Enders F, Katzka DA, Kephardt GM, Kita H, Kryzer LA, Romero Y, Smyrk TC, Talley NJ. Swallowed Fluticasone Improves Histologic but Not Symptomatic Responses of Adults with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dohil R, Newbury R, Fox L, Bastian J, Aceves S. Oral Viscous Budesonide Is Effective in Children With Eosinophilic Esophagitis in a Randomized, Placebo-controlled Trial. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:418–29. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Straumann A, Conus S, Degen L, Felder S, Kummer M, Engel H, Bussmann C, Beglinger C, Schoepfer A, Simon HU. Budesonide is effective in adolescent and adult patients with active eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1526–37. 1537 e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dellon ES, Sheikh A, Speck O, Woodward K, Whitlow AB, Hores JM, Ivanovic M, Chau A, Woosley JT, Madanick RD, Orlando RC, Shaheen NJ. Viscous Topical is More Effective than Nebulized Steroid Therapy for Patients with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2012 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Aceves SS, Dohil R, Newbury RO, Bastian JF. Topical viscous budesonide suspension for treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:705–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lindberg GM, Van Eldik R, Saboorian MH. A case of herpes esophagitis after fluticasone propionate for eosinophilic esophagitis. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;5:527–30. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Helou EF, Simonson J, Arora AS. 3-Yr-Follow-Up of Topical Corticosteroid Treatment for Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2184–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Straumann A, Conus S, Degen L, Frei C, Bussmann C, Beglinger C, Schoepfer A, Simon HU. Long-term budesonide maintenance treatment is partially effective for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:400–9. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Vitellas KM, Bennett WF, Bova JG, Johnson JC, Greenson JK, Caldwell JH. Radiographic manifestations of eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Abdom Imaging. 1995;20:406–13. doi: 10.1007/BF01213260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Liacouras CA, Wenner WJ, Brown K, Ruchelli E. Primary eosinophilic esophagitis in children: successful treatment with oral corticosteroids. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998;26:380–5. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199804000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Attwood SE, Lewis CJ, Bronder CS, Morris CD, Armstrong GR, Whittam J. Eosinophilic oesophagitis: a novel treatment using Montelukast. Gut. 2003;52:181–5. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.2.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Stumphy J, Al-Zubeidi D, Guerin L, Mitros F, Rahhal R. Observations on use of montelukast in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis: insights for the future. Dis Esophagus. 2011;24:229–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2010.01134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lucendo AJ, De Rezende LC, Jimenez-Contreras S, Yague-Compadre JL, Gonzalez-Cervera J, Mota-Huertas T, Guagnozzi D, Angueira T, Gonzalez-Castillo S, Arias A. Montelukast was inefficient in maintaining steroid-induced remission in adult eosinophilic esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:3551–8. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1775-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Dellon ES, Chen X, Miller CR, Woosley JT, Shaheen NJ. Diagnostic utility of major basic protein, eotaxin-3, and leukotriene enzyme staining in eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012 doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.202. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Gupta SK, Peters-Golden M, Fitzgerald JF, Croffie JM, Pfefferkorn MD, Molleston JP, Corkins MR, Lim JR. Cysteinyl leukotriene levels in esophageal mucosal biopsies of children with eosinophilic inflammation: are they all the same? Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1125–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kirsch R, Bokhary R, Marcon MA, Cutz E. Activated mucosal mast cells differentiate eosinophilic (allergic) esophagitis from gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44:20–6. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31802c0d06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Netzer P, Gschossmann JM, Straumann A, Sendensky A, Weimann R, Schoepfer AM. Corticosteroid-dependent eosinophilic oesophagitis: azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine can induce and maintain long-term remission. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:865–9. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32825a6ab4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Stein ML, Collins MH, Villanueva JM, Kushner JP, Putnam PE, Buckmeier BK, Filipovich AH, Assa’ad AH, Rothenberg ME. Anti-IL-5 (mepolizumab) therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:1312–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Straumann A, Conus S, Grzonka P, Kita H, Kephart G, Bussmann C, Beglinger C, Smith DA, Patel J, Byrne M, Simon HU. Anti-interleukin-5 antibody treatment (mepolizumab) in active eosinophilic oesophagitis: a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Gut. 2010;59:21–30. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.178558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]