Abstract

Various adenosine analogues were tested at the adenosine A2B receptor. Agonist potencies were determined by measuring the cyclic AMP production in Chinese Hamster Ovary cells expressing human A2B receptors. 5′-N-Substituted carboxamidoadenosines were most potent. 5′-N-Ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (NECA) was most active with an EC50 value of 3.1 μM. Other ribose modified derivatives displayed low to negligible activity. Potency was reduced by substitution on the exocyclic amino function (N6) of the purine ring system. The most active N6-substituted derivative N6-methyl-NECA was 5 fold less potent than NECA. C8- and most C2-substituted analogues were virtually inactive. 1-Deaza-analogues had a reduced potency, 3- and 7-deazaanalogues were not active.

Introduction

The adenosine A2B receptor is one of the four known subtypes of adenosine receptors, the others being named A1, A2A and A3. The A1 and A3 receptor subtypes inhibit the enzyme adenylate cyclase, diminishing the production of the second messenger cyclic AMP. On the contrary, both A2 subtypes stimulate adenylate cyclase to produce cyclic AMP. A subdivision of A2 receptors was first proposed by Daly et al. based upon observations of lower EC50 values on cyclic AMP accumulation in rat striatum than in rat brain slices1. Bruns et al. designated the high affinity striatal A2 receptor as the A2A subtype, whereas they referred to the low affinity subtype, existing throughout the brain, as to A2B2. Molecular cloning and expression have been reported of all four subtypes of adenosine receptors of several species, including the A2B receptor from both rat and human brain3,4. By the cloning techniques it had also become possible to determine tissue distributions of the receptors. In the human body, low expression of the A2B receptor was found in kidney, moderate levels were observed in heart, brain and lungs, and high densities were measured in the colon5.

Through A2B receptors, adenosine inhibits the Tumour Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α) production by monocytes6,7. TNF-α is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that triggers the production cascade of other cytokines and acute-phase proteins8. When produced in large quantities—e.g., when the immune system is overactivated due to a challenge by pathogenic bacteria—TNF-α can lead to septic shock and eventually to death9,10. A future therapeutic purpose for adenosine A2B receptor agonists could thus be the treatment of septic shock.

However, no A2B selective compounds have been reported yet. One of the most potent agonists on this subtype is 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (NECA). EC50 values on the production of cyclic AMP are in the low micromolar range, considerably higher than on the other subtypes11–14.

As a start of our search to find agonists with increased potency and selectivity, we screened adenosine analogues with a great variety of substituents and modifications on their ability to generate cyclic AMP in a CHO cell line stably transfected with human adenosine A2B receptor cDNA4.

Results

Cyclic AMP production was measured at compound concentrations of 100 μM. Cyclic AMP production is shown as percentage of the production by 100 (μM NECA. A number of compounds were taken further into investigation by determining their EC50 values.

NECA (1) and 5′-N-cyclopropylcarboxamidoadenosine (NCPCA; 2) were found to have EC50 values on cyclic AMP production of 3.1 and 5.3 μM, respectively (TABLE 1).

TABLE 1.

Activities of NECA and NCPCA on cAMP production in CHO cells expressing human A2B receptors

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| R | EC50 (μM) | ||

| 1 | NECA | ethyl | 3.1±2.4 |

| 2 | NCPCA | cyclopropyl | 5.3±1.6 |

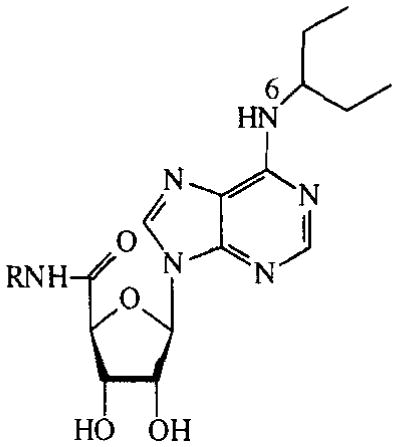

More 5′-carboxamidoadenosines are listed in TABLE 2. Compounds 3–8 are N6-(3-pentyl)-substituted. In this series, the 5′-N-benzyl-substituted analogue (8) did not show activity. Cyclic AMP production decreased according to the following substituent order: cyclopropyl > isopropyl > methyl > allyl > 3-pentyl. NECA lost its activity when the ethyl substituent was modified into a 2-aminoethyl group (compound 9).

TABLE 2.

Activities of N6-(3-pentyl), 5′-N-disubstituted carboxamidoadenosines on cAMP production in CHO cells expressing human A2B receptors. Compounds were tested at 100 μM. Activities are given as percentages of stimulation with 100 μM NECA.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| R | % stimulation | |

| 3 | methyl | 63% |

| 4 | allyl | 41% |

| 5 | isopropyl | 69% |

| 6 | cyclopropyl | 78% |

| 7 | 3-pentyl | 6% |

| 8 | benzyl | 0% |

| 9 | 2-NH2-ethyl* | 1% |

N6-unsubstituted analogue

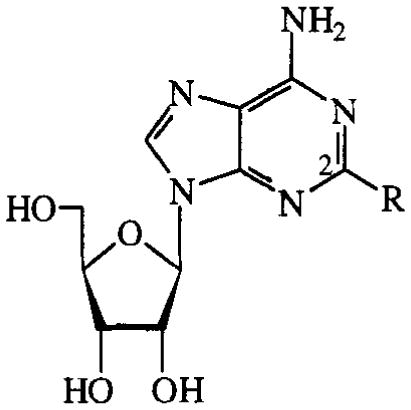

Adenosines substituted at the C2-position of the purine are shown in TABLE 3. Several 2-thio-, 2-amino- and 2-halo-analogues were evaluated. C2-substution of adenosine diminished potency. In the 2-halo series, 2-chloroadenosine (18) was the most potent compound with an EC50 value of 24 μM; potency decreased when an iodo or a fluoro substituent was present instead of a chloro substituent. 2-Thio- and 2-amino-substituted adenosines, including the A2A agonist CV 1808, displayed low potency.

TABLE 3.

Activities of C2-substituted adenosines on cAMP production in CHO cells expressing human A2B receptors. Compounds were tested at 100 μM. Activities are given as percentages of stimulation with 100 μM NECA.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| R | % stimulation or EC50 (μM) | |

| 10 | SH | 1% |

| 11 | SCH2CH2CN | 0% |

| 12 | S-cyclohexyl | 3% |

| 13 | S-hexadecyl | 5% |

| 14 | SBn | 3% |

| 15 | NHPh (CV1808) | 10% |

| 16 | NHPhEt | 3% |

| 17 | F | 23% |

| 18 | Cl | 24±11μM |

| 19 | I | 2% |

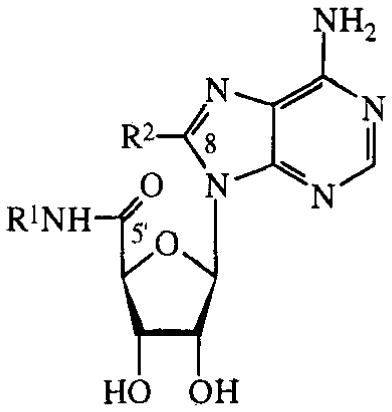

In the C8-amino-substituted series (TABLE 4), only the 8-amino-analogue itself showed some activity, albeit marginal (9%).

TABLE 4.

Activities of C8-substituted NECA and MECA analogues on cAMP production in CHO cells expressing human A2B receptors. Compounds were tested at 100 μM. Activities are given as percentages of stimulation with 100 μM NECA.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | R2 | % stimulation | |

| 20 | Et | Br | 0% |

| 21 | Et | NH2 | 9% |

| 22 | Et | EtNH | 0% |

| 23 | Et | Me2N | 0% |

| 24 | Me | MeNH | 0% |

| 25 | Me | Me2N | 0% |

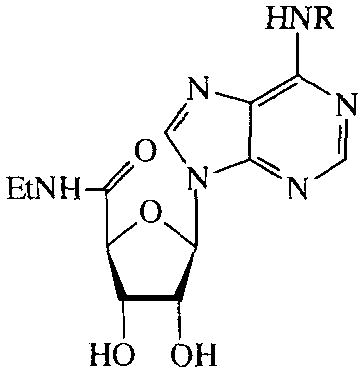

N6-substituted analogues were categorized into four groups as shown in TABLES 5–8. In TABLE 5, NECA analogues are listed; analogues of 5′-N-methylcarboxamidoadenosine (MECA) are shown in TABLE 6; adenosine derivatives without modifications in the ribose are displayed in TABLE 7; some N6-functionalized congeners are listed in TABLE 8.

TABLE 5.

Activities of N6-substituted NECA analogues on cAMP production in CHO cells expressing human A2B receptors. Compounds were tested at 100 μM. Activities are given as percentages of stimulation with 100 μM NECA.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| R | EC50 (μM) or % stimulation | |

| 26 | methyl | 19±6μM |

| 27 | 3-CH3O-phenyl | 63% |

| 28 | 3-CH3-benzyl | 16% |

| 29 | 4-CH3O-benzyl | 14% |

| 30 | 3-CH3O-benzyl | 91% |

| 31 | 3-F-benzyl | 80% |

| 32 | 3-Cl-benzyl | 84% |

| 33 | 3-Br-benzyl | 95% |

| 34 | 3-I-benzyl | 71% |

| 35 | 2-NO2-benzyl | 87% |

| 36 | 3-NO2-benzyl | 57% |

| 37 | 4-NO2-benzyl | 41% |

| 38 | benzyl* | 24% |

5′-N-cyclopropyl analogue

TABLE 8.

Activities of N6 functionalized congeners on cAMP production in CHO cells expressing human A2B receptors. Compounds were tested at 100 μM. Activities are given as percentages of stimulation with 100 μM NECA.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| R | % stimulation | |

| 80 | NHAc | 13% |

| 81 | N(CH3)3 | 17% |

| 82 | OH | 19% |

TABLE 6.

Activities of N6-substituted MECA analogues on cAMP production in CHO cells expressing human A2B receptors. Compounds were tested at 100 μM. Activities are given as percentages of stimulation with 100 μM NECA.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | R2 | % stimulation | |

| 39 | 3-CH3-benzyl | H | 13% |

| 40 | 3-CF3-benzyl | H | 0% |

| 41 | 4-Cl-benzyl | H | 1% |

| 42 | 3-Br-benzyl | H | 16% |

| 43 | 4-Br-benzyl | H | 3% |

| 44 | 3-I-benzyl (IB-MECA) | H | 10% |

| 45 | 3-I-benzyl (Cl-IB-MECA) | Cl | 3% |

| 46 | 3-I-benzyl | SMe | 0% |

| 47 | 3-I-benzyl | NHMe | 0% |

| 48 | 4-SO3H-benzyl | H | 0% |

| 49 | 3-I-4-NH2-benzyl (I-AB-MECA) | H | 18% |

| 50 | 3-NO2-benzyl | H | 4% |

| 51 | (R)-1-phenyl-ethyl | H | 23% |

| 52 | (S)-1-phenyl-ethyl | H | 15% |

| 53 |

|

H | 0% |

| 54 | benzyl | H | 15% |

TABLE 7.

Activities of N6-substituted adenosines on cAMP production in CHO cells expressing human A2B receptors. Compounds were tested at 100 μM. Activities are given as percentages of stimulation with 100 μM NECA.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | R2 | EC50 (μM)or % stimulation | |

| 55 | cyclopentyl (CPA) | H | 203±97 μM |

| 56 | phenyl | H | 63±19 μM |

| 57 | benzyl | H | 96±32 μM |

| 58 | phenylethyl | H | 67±4 μM |

| 59 | (R)-phenylisopropyl (R-PIA | H | 53 ±8μM |

| 60 | 4-SO3H-phenyl (SPA) | H | 52 ±17μM |

| 61 |

|

H | 3% |

| 62 | 4-NH2-benzyl | H | 12% |

| 63 | 2-CH3benzyl (metrifudil) | H | 21% |

| 64 | 2-Cl-benzyl | H | 35% |

| 65 | 3-I-benzyl | H | 18% |

| 66 | 3-I-benzyl | Cl | 6% |

| 67 | 3-I-benzyl | NH2 | 6% |

| 68 | 4-SO3H-phenylpropyl | H | 1% |

| 69 | 4-SO3H-phenylbutyl | H | 2% |

| 70 | 4-SO3H-phenyldecyl | H | 4% |

| 71 | n-butyl | H | 23% |

| 72 | n-decyl | H | 3% |

| 73 | 4-NH2-butyl | H | 10% |

| 74 | 10-NH2-decyl | H | 0% |

| 75 | N, N-dimethy* | H | 0% |

| 76 | N, N-dipropy* | H | 0% |

| 77 | NH2 | H | 0% |

| 78 | (adenosin-N6-yl)butyl | H | 15% |

| 79 | (adenosin-N6-yl)decyl | H | 13% |

N6, N6-disubstituted analogue

In the series of the NECA analogues in TABLE 5, the N6-methyl-substituted member (26) was the most active one with an EC50 value of 19 μM. The other analogues, most of them bearing N6-(substituted)-benzyl groups, had activities varying from 14–95%. The MECA analogues in TABLE 6 generally displayed a considerably lower activity than the NECA analogues (0–23%). In the adenosine series (TABLE 7), EC50 values of compounds 55–60 were determined. The A1 selective agonist N6-cyclopentyladenosine (CPA, 55) had an EC50 value of 203 μM. The N6-phenyl-(56), N6-benzyl-(57), N6-phenylethyl-(58) and N6-(R)-phenylisopropyl-substituted (R-PIA, 59) adenosines were more active, with EC50 values in the range of 53–96 μM. The activity of N6-(4-sulfophenyl)adenosine (SPA, 60) was in this same range (52 μM). Adenosine derivatives with other N6-substituents were also tested. N6-furyl adenosine (61) gave a 3% response. Analogues with substituted benzyl groups had activities of 12–35% (62–65). N6-alkyladenosines (71–74) were less potent than the N6-phenyl(alkyl)adenosines mentioned before. N6, N6-dialkyladenosines (75,76) were inactive. The N6-(4-sulfo-phenyl)alkyladenosines 68–70 appeared to be far less active than SPA (60). N6-amino adenosine (6-hydrazino purine riboside, 77) was not active.

The N6, C2-disubstituted compounds 45–47 and 66,67 were found to have reduced activities in comparison with the C2-unsubstituted analogues 44 and 72. Analogues with large substituents, such as the (adenosin-N6-yl)alky)-substituted compounds 78 and 79 in TABLE 7 and the functionalized congeners 80–82 in TABLE 8, had low activities (10–20%).

Deaza derivatives (TABLE 9) showed negligible potencies, except the 1-deaza analogues.

TABLE 9.

Activities of deazaadenosine analogues on cAMP production in CHO cells expressing human A2B receptors. Compounds were tested at 100 μM. Activities are given as percentages of stimulation with 100 μM NECA.

| analogue | % stimulation or EC50 (μM) | |

|---|---|---|

| 83 | 1-deazaadenosine | 10% |

| 84 | 2-chloro-1-deazaadenosine | 20% |

| 85 | 3-deazaadenosine | 1% |

| 86 | 1, 3-dideazaadenosine | 1% |

| 87 | 7-deazaadenosine | 0% |

| 88 | 1, 7-dideazaadenosine | 0% |

| 89 | 1-deaza-NECA | 16±5μM |

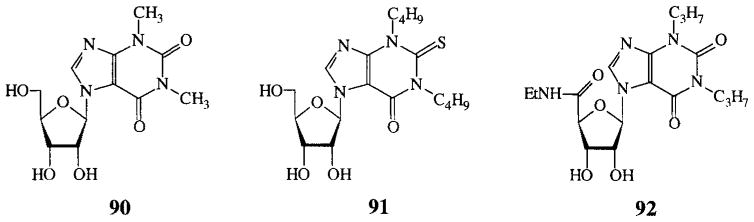

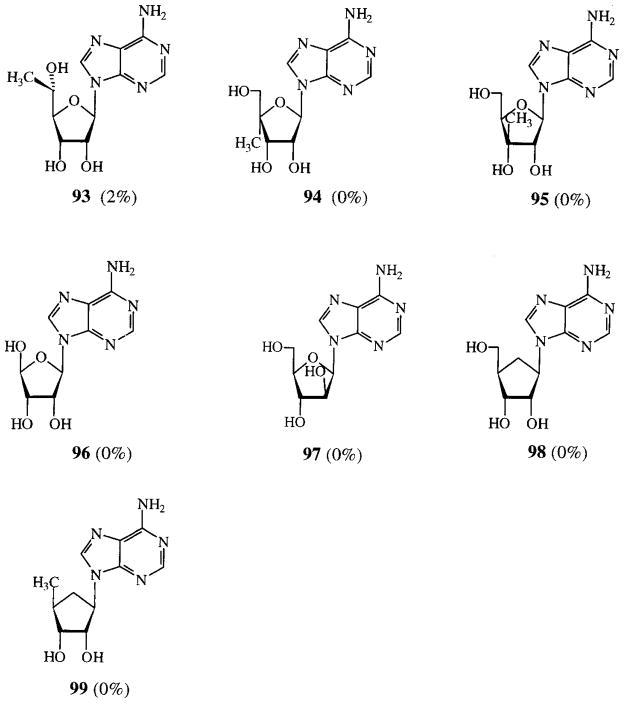

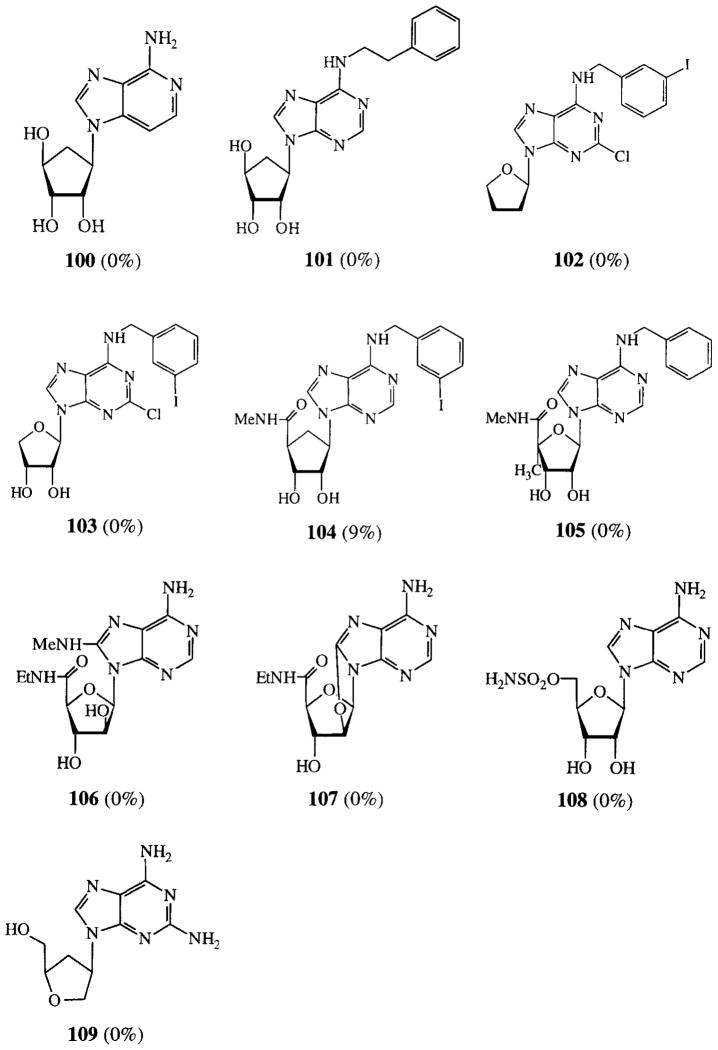

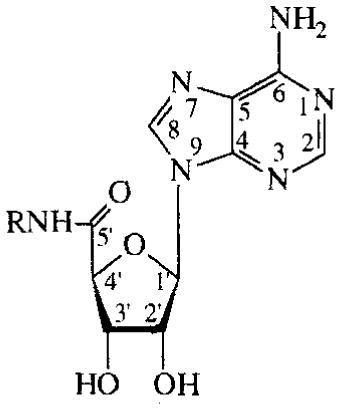

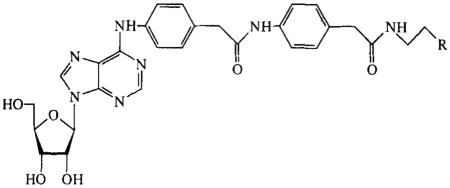

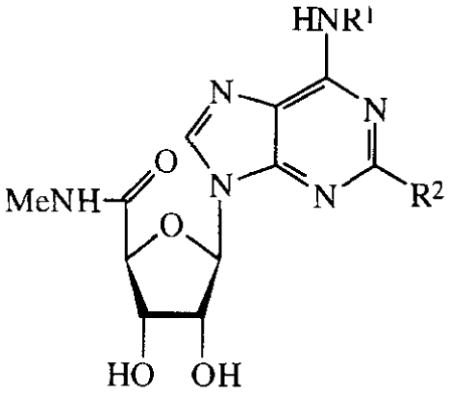

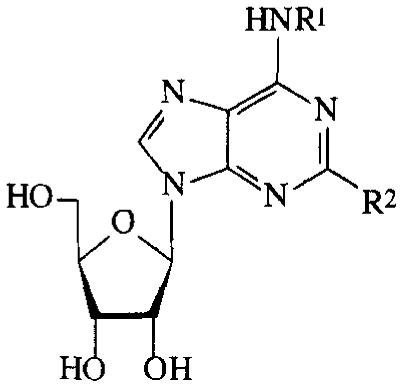

7-Xanthinyl adenosines (FIG. 1) lacked potency, as well as the ribose modified adenosines in FIG. 2. Compounds that were not categorized, most of them having more than one modification, are depicted in FIG. 3. These all had low activities.

FIG. 1.

7-Xanthinyl analogues (no activities on cAMP production in CHO cells expressing human A2B receptors). Compounds were tested at 100 μM.

FIG. 2.

Activities of ribose modified adenosines on cAMP production in CHO cells expressing human A2B receptors. Compounds were tested at 100 μM. Activities are given as percentages of stimulation with 100 μM NECA.

FIG. 3.

Activities of variously modified analogues on cAMP production in CHO cells expressing human A2B receptors. Compounds were tested at 100 μM. Activities are given as percentages of stimulation with 100 μM NECA.

Discussion

Our aim was to analyze compounds for A2B agonism. Therefore we tested modified adenosine analogues. In this approach our focus was on stimulation of the receptor. We did not do experiments to determine antagonistic activities.

Until today the reference ligand for the adenosine A2B receptor has been the nonselective adenosine agonist NECA. Pierce et al. and Alexander et al. reported NECA to have an EC50 value of approximately 1 μM on the production of cyclic AMP in CHO-K1 cells4,14. These cells were also used here as the test system. EC50 values of 3.1 and 5.3 μM were determined for NEC A and its 5′-N-cyclopropyl analogue NCPCA, respectively (TABLE 1).

Regarding the relatively high potency of the carboxamido analogues NECA and NCPCA, the compounds in TABLE 2 are interesting. Although the N6-(3-pentyl) group reduced activity, still a trend can be observed. The 5′-N-cyclopropyl-substituted analogue was the most potent ligand in this series, followed by the isopropyl-, the methyl-, the allyl-, the (3-pentyl)- and the benzyl-substituted compounds. A (3-pentyl) and a benzyl group in this position are largely unfavourable, probably because of steric or electronic interactions.

Substitution at the C2-position (TABLE 3) with appropriate groups is known to enhance A2A selectivity. The relatively A2A selective agonist CV 1808 (15) showed only low activity in the A2B assay. This was also observed with other 2-amino-substituted adenosines and with 2-thio-analogues. Of the halogen atoms in the 2-position, chloro (in compound 18) appeared to be a relatively good substituent. The activity (24 μM), however, did not equal that of NECA. Recently Alexander et al reported 2-chloroadenosine to have an EC50 value of 5.3 μM on the same cell line we used here14; the A2A reference compound 2-[p-(2-carboxyethyl)-phenylethylamino]-NECA (CGS 21680, not tested in our study) showed a 40% response at a concentration of 100 μM and it was inactive at concentrations of 10 μM. Results from both this and our study suggest that C2 is not a suitable site of modification in order to gain A2B potency. Probably there is little space in the receptor for a substituent in this position.

Substitution at the C8-position (TABLE 4) led to virtually inactive compounds. Bruns reported responses for 8-methylamino- and 8-dimethylaminoadenosine of 33% and 5% respectively11. These responses are higher than the activities we measured with the MECA and NECA analogues. The 5′-N-methylcarboxamido moiety in 8-methylamino-MECA (24) probably causes the lower activity in comparison with Bruns’ adenosine analogue. More recently it has been shown that C8-substitution yields partial agonists for the A1 receptor15.

N6-Substitution with appropriate groups has led to A1 and A3 selective agonists16,17. In the N6-substituent series of MECA (TABLE 6), compounds have reduced activities compared to their NECA analogues (TABLE 5). It is concluded that an ethyl substituent on the 5′-carboxamido group is favoured over a methyl substituent. The selective A3 agonist 2-chloro-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-MECA (Cl-IB-MECA, 45)18 was included in the MECA series. This compound and the other 2-substituted derivatives 46, 47 (TABLE 6), 66 and 67 (TABLE 7) displayed lower activities than their C2-unsubstituted analogues 44 and 72. These results also indicate that C2-substitution diminishes A2B potency.

N6 should be monosubstituted, because the disubstituted analogues 75 and 76 were inactive. The potency order for the N6-benzyl-substituted derivatives (TABLES 5, 6 and 7) was: 2 ≥ 3 > 4 substitution. However, no trends in the type of benzyl substituents could be discovered. In the adenosine series (TABLE 7) optima in potency were found for N6-phenyl (56) and N6-(R)-phenylisopropyl (59) substitution (50–60 μM). The N6-benzyl substituted analogue (57) showed the lowest activity (96 (μM). Metrifudil (63, N6-[(2-methylphenyl)methyl]adenosine) has been reported to be a moderately A2B selective agonist, albeit five times less potent than NECA on guinea pig aorta contraction19. Here we report a 21% response for metrifudil. These results suggest that substituted N6-phenyl and N6-phenylisopropyl groups might lead to more active agonists than substituted benzyl groups.

The NH2 group in the adenosine molecule is even allowed to bear rather large substituents (TABLES 7 and 8), not causing a total loss of activity (diadenosines 78 and 79, functionalized congeners 80–82). There must be some space in the receptor in this position. A part of the N6-substituent might occupy a region outside the receptor, as has been hypothesized for the adenosine A1 receptor20.

From the results of the deazaadenosines in TABLE 9 it is obvious that the purine nitrogen atoms are essential for potency of adenosine A2B receptor agonists, especially N3 and N7. When N1 was substituted for CH, a response was left, such as in 1-deazaadenosine (90), 2-chloro-1-deazaadenosine (91) and 1-deaza-NECA (96). 1-Deaza-NECA21 was moderately potent with an EC50 value of 16 μM. When the other nitrogen atoms were substituted, the response was negligible. In Bruns’ study 7-deazaadenosine was found to be inactive, whereas 1- and 3-deazaadenosine were not evaluated. 2-Azaadenosine on the contrary (not tested in our assay) was slightly less active than NECA11. All results together suggest that the purine skeleton should not be altered. Similar observations have been done for analogues in TABLE 9 in binding experiments on the rat brain A1 receptor and on the platelet A2A receptor22.

Derivatives in which the purine ring system was modified into a (substituted) xanthinyl group are depicted in FIG. 1. All three hybrides gave very low responses. This accounts again for the importance of an intact purine ring system for A2B agonists.

Low responses were also found for adenosines with modified ribose parts (FIG. 2) and with various modifications (FIG. 3). It should be mentioned that adenosine deaminase was added to the assay to avoid false hits caused by endogenous adenosine. The use of adenosine deaminase, however, may have inactivated some of the derivatives in FIG. 2. Especially suspect are 94, 95, 97 and 98, all having (besides a free 6-amino function) an unsubstituted hydroxymethylene group which has been proven necessary for adenosine deaminase substrates to be hydrolysed23. 5′-Deoxyasteromycin (99), not a substrate for adenosine deaminase, did not show activity, whereas Bruns found a fairly good agonistic activity for asteromycin 9811. Apparently, removal of the 5′-hydroxyl group is detrimental for A2B receptor activity. This is also the case when the hydroxymethylene group is removed (103, compare with 66), or when a methyl group is added on C-5′ (93). Adding a methyl group on C-4′ also lowers activity (94 and 105, compare with 54). Substituting the ribose ring oxygen for a methylene group does not cause an increase of activity (98 and 104). Summarizing, for enhanced potency it is not allowed to add methyl groups in various positions in the ribose part, neither to remove the 5′-hydroxyl group or the 5′-methylene group, nor substituting the ring oxygen for a methylene group.

Conclusions and evaluation

By the study presented here, we gained more insight in the pharmacologic profile of the human adenosine A2B receptor. Of all compounds, NECA was most potent with an EC50 value of 3.1 μM, and still the most active agonist reported yet. Concerning the medicinal chemistry of the human A2B receptor we conclude that 1) 5′-N-carboxamidoadenosines show highest potencies; NECA analogues are most potent in this series, MECA derivatives are less active; the rest of the ribose moiety should not be changed; 2) C2- and C8-substitution lower agonist activity; 3) N6-substitution reduces potency, but less severely than C2 and C8 substitution; 4) the purine ring system should not be modified into deazapurines or xanthines.

Two sites of substitution might be promising in order to increase agonist potency. The first site is the 5′-carboxamido moiety. Analogues with novel substituents on the carboxamido group could be synthesized and tested. Secondly, there appears to be space in the N6-region of the receptor. Appropriate substituents in this part of the molecule, possibly combined with a 5′-carboxamido function, might yield more potent and selective agonists.

Experimental section

Materials

Test system

A Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO.K1) cell line stably transfected with human adenosine A2B receptor cDNA4,14 was used to test the adenosine analogues.

Compounds

[3H]-cyclic AMP was obtained from NEN (Du Pont de Nemours, ‘s-Hertogenbosch, the Netherlands).

Test compounds came from the following persons or companies: NECA (1) and 2-chloroadenosine (18) were purchased from Sigma; NCPCA (2) and compounds 3–8 and 27 were a gift of Dr. R.A. Olsson; compounds 15 and 16 were a gift of Takeda Chem. Ind. Ltd., Japan; compounds 19, 56 and 58 were synthesized according to literature procedures, with minor modifications24–26; CPA (55) and R-PIA (59) were purchased from Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany; compound 57 was a gift from Dr. A. van Aerschot, Leuven, Belgium; SPA (60) was a gift from Research Biochemicals Inc., Massachusetts, USA; compound 62 was a gift from Dr. J. Linden; compound 64 was a gift from Dr. O. Saiko and Prof. H.P. Wolf, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany; compounds 71–76, 78 and 79 have been synthesized and published before by Van Galen et al.27; one of the authors, G.C., provided the deaza compounds 83–89; one of the authors, K. A. J., provided compounds 9–14,17, 20–54, 61, 63–70,77, 80–82,90–109.

Cell culture

CHO-K1 cells were grown under 5% CO2/95% O2 humidified atmosphere at a temperature of 37°C in DMEM supplemented with Hams F12 nutrient mixture (1/1), 10% newborn calf serum, 2mM glutamine and containing 100 IU penicillin and streptomycin. Cells were cultured in 10 cm Ø round plates and subcultured when grown confluent (approximately after 72 hours). PBS/EDTA containing 0.25% trypsine was used for detaching the cells from the plates. Experimental cultures were grown overnight as a monolayer in 24 wells tissue culture plates (400 μL/well; 0.8×106 cells/well).

Cyclic AMP generation

Cyclic AMP generation was performed in DMEM/HEPES buffer (DMEM containing 50mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 37°C). To each well, washed twice with DMEM/HEPES buffer, 125 μL adenosine deaminase (final concentration 10 U/mL) and 125 μL rolipram (final concentration 100 μM) were added. After incubation for 40 minutes at 37°C, 100 μL of the ligand solution (final concentration 100 μM; maximal DMSO concentration 3%) was added. After 15 minutes, incubation at 37°C was terminated by removing the medium and adding 200 μL of 0.1 M HCl. Wells were stored at −20°C until assay.

Cyclic AMP determination

The amounts of cyclic AMP were determined after a protocol with cAMP binding protein28 with the following minor modifications. As a buffer was used 150 mM K2HPO4/10mM EDTA/0.2% BSA FV at pH 7.5. Samples (20 μL) were incubated for 90 minutes at 0°C. Incubates were filtered over GF/C glass microfibre filters in a Brandel M-24 Cell Harvester. The filters were additionally rinsed with 4 times 2 ml 150 mM K2HPO4/10mM EDTA (pH 7.5, 4°C). Punched filters Were counted in Packard Emulsifier Safe scintillation fluid after 2 hours of extraction.

References

- 1.Daly JW, Butts-Lamb P, Padgett W. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1983;1:69–80. doi: 10.1007/BF00734999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruns RF, Lu GH, Pugsley TA. Mol Pharmacol. 1986;29:331–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stehle JH, Rivkees SA, Lee JJ, Weaver DR, Deeds JD, Reppert SM. Mol Endocrinol. 1992;6:384–393. doi: 10.1210/mend.6.3.1584214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pierce KD, Furlong TJ, Selbie LA, Shine J. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1992;187:86–93. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81462-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salvatore CA, Jacobson MA, Taylor HE, Linden J, Johnson RG. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10365–10369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Le Vraux V, Chen Y-l, Masson I, De Sousa M, Giroud J-P, Florentin I, Chauvelot-Moachon L. Life Sciences. 1993;52:1917–1924. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90632-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thiel M, Chouker A. J Lab Clin Med. 1995;126:275–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milchalek SM, Moore RN, McGhee JR, Rosenstreich DI, Mergenhagen SE. J Infect Dis. 1980;141:55. doi: 10.1093/infdis/141.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tracey KJ, Beutler B, Lowry SF, Merryweather J, Wolpe S, Milsark IW, Hariri RJ, Fahey TJ, III, Zentella A, Albert JD, Shires GT, Cerami AC. Science. 1986;234:470–474. doi: 10.1126/science.3764421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beutler B, Milsark IW, Cerami AC. Science. 1985;229:869–871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruns RF. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1980;58:673–691. doi: 10.1139/y80-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brackett LE, Daly JW. Biochem Pharmacol. 1994;47:801–814. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castañón MJ, Spevak W. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1994;198:626–631. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexander SPH, Cooper J, Shine J, Hill SJ. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;119:1286–1290. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb16035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roelen H, Veldman N, Spek AL, Von Frijtag Drabbe Künzel J, Mathôt RAA, IJzerman APJ. Med Chem. 1996;39:1463–1471. doi: 10.1021/jm950267m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobson KA, Van Galen PJ, Williams M. J Med Chem. 1992;35:407–422. doi: 10.1021/jm00081a001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallo-Rodriguez C, Ji XD, Melman N, Siegman BD, Sanders LH, Orlina J, Fischer B, Pu Q, Olah ME, van Galen PJ, et al. J Med Chem. 1994;37:636–646. doi: 10.1021/jm00031a014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim HO, Ji XD, Siddiqi SM, Olah ME, Stiles GL, Jacobson KA. J Med Chem. 1994;37:3614–3621. doi: 10.1021/jm00047a018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gurden MF, Coates J, Ellis F, Evans B, Foster M, Hornby E, Kennedy I, Martin DP, Strong P, Vardey CJ, Wheeldon A. Br J Pharmacol. 1993;109:693–698. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.IJzerman AP, Van Galen PJM, Jacobson KA. Drug Design and Discovery. 1992;9:49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cristalli G, Franchetti P, Grifantini M, Vittori S, Klotz KN, Lohse MJJ. Med Chem. 1988;31:1179–1183. doi: 10.1021/jm00401a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cristalli G, Griffantini M, Vittori S, Balduini W, Cattabeni F. Nucleosides Nucleotides. 1985;4:625–639. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bloch A, Robins MJ, McCarthy JR. J Med Chem. 1967;10:908–912. doi: 10.1021/jm00317a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montgomery JA, Hewson K. J Het Chem. 1964;1:213–214. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fleysher MH, Bloch A, Hakala MT, Nichol CA. J Med Chem. 1969;12:1056–1061. doi: 10.1021/jm00306a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kusachi S, Thompson RD, Bugni WJ, Yamada N, Olsson RA. J Med Chem. 1985;28:1636–1643. doi: 10.1021/jm00149a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Galen PJM, IJzerman AP, Soudijn W. FEBS Letters. 1987;223:197. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80535-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van der Wenden EM, Hartog-Witte HR, Roelen HCPF, Von Frijtag Drabbe Künzel JK, Pirovano IM, Mathôt RAA, Danhof M, Van Aerschot A, Lidaks MJ, IJzerman AP, Soudijn W. Eur J Pharmacol-Mol Pharmacol Sect. 1995;290:189–199. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(95)00064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]