Abstract

We report an approach to the chemical oxidation of a ferrocene-containing cationic lipid [bis(11-ferrocenylundecyl)dimethylammonium bromide, BFDMA] that provides redox-based control over the delivery of DNA to cells. We demonstrate that BFDMA can be oxidized rapidly and quantitatively by treatment with Fe(III)sulfate. This chemical approach, while offering practical advantages compared to electrochemical methods used in past studies, was found to yield BFDMA/DNA lipoplexes that behave differently in the context of cell transfection from lipoplexes formed using electrochemically oxidized BFDMA. Specifically, while lipoplexes of the latter do not transfect cells efficiently, lipoplexes of chemically oxidized BFDMA promoted high levels of transgene expression (similar to levels promoted by reduced BFDMA). Characterization by SANS and cryo-TEM revealed lipoplexes of chemically and electrochemically oxidized BFDMA to both have amorphous nanostructures, but these lipoplexes differed significantly in size and zeta potential. Our results suggest that differences in zeta potential arise from the presence of residual Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions in samples of chemically oxidized BFDMA. Addition of the iron chelating agent EDTA to solutions of chemically oxidized BFDMA produced samples functionally similar to electrochemically oxidized BFDMA. These EDTA-treated samples could also be chemically reduced by treatment with ascorbic acid to produce samples of reduced BFDMA that do promote transfection. Our results demonstrate that entirely chemical approaches to oxidation and reduction can be used to achieve redox-based ‘on/off’ control of cell transfection similar to that achieved using electrochemical methods.

Keywords: Cationic Lipids, Lipoplexes, DNA Delivery, Nanostructure, Ferrocene

Introduction

Cationic lipids are used widely to formulate lipid/DNA complexes (or lipoplexes) that promote delivery of DNA to cells [1-5]. Many properties of lipoplexes depend strongly on the nature of lipid-DNA interactions, and the ability to control or change the nature of these interactions is thus important in a range of contexts. Cationic lipids containing functional groups that respond to changes in stimuli present in intracellular environments, for example, can promote more effective trafficking of DNA and thus more efficient cell transfection [6-15]. In contrast, lipids containing functionality that can be addressed, transformed, or activated using other, externally-applied stimuli [16-18] could provide new opportunities to exert active or ‘on-demand’ control over the properties of lipoplexes (for example, methods that provide spatiotemporal control over the ‘activation’ of lipoplexes could lead to new approaches to active spatiotemporal control over the delivery of DNA to cells).

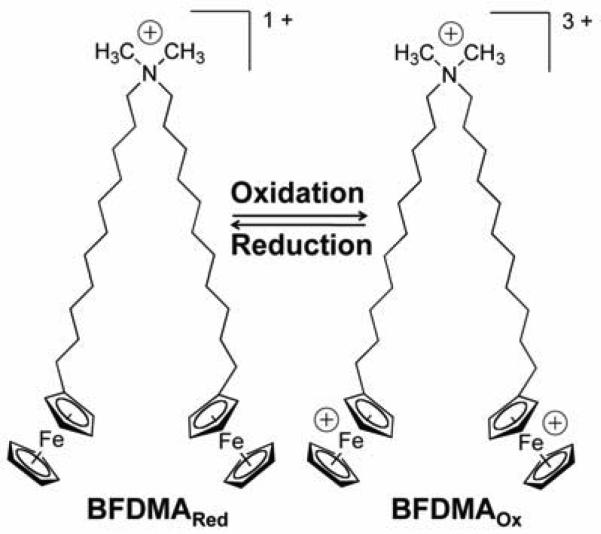

As a step toward the development of lipids that provide active control over the properties of lipoplexes, our group has investigated interactions between DNA and the redox-active, ferrocene-functionalized cationic lipid BFDMA [bis(11-ferrocenylundecyl) dimethylammonium bromide, Figure 1] [19-25]. Our past studies demonstrate that lipoplexes formed using BFDMA can promote the delivery of DNA to cells, but that the ability to do so depends strongly on the oxidation state of the ferrocenyl groups of the lipid [19, 20, 23, 24]. For example, whereas the reduced form of BFDMA (net charge of +1) can promote high levels of transgene expression, lipoplexes formed using oxidized BFDMA (net charge of +3) yield negligible or very low levels. Physical characterization experiments suggest that this oxidation-state dependence arises from differences in the nanostructures and other biophysical properties (e.g., differences in zeta potentials) that determine the extents to which the lipoplexes are internalized by cells [21-24]. The results of our past work also suggest that these differences in lipoplex properties that exert their primary influences in the extracellular environment (i.e., by either promoting or almost completely preventing internalization, respectively [23, 24]) rather than by influencing downstream events that occur in the intracellular environment.

Figure 1.

Structure of bis(11-ferrocenylundecyl)dimethylammonium bromide (BFDMA).

Because ferrocenyl groups can be oxidized and reduced readily and reversibly (using either chemical or electrochemical methods) [26, 27], BFDMA also offers a basis for active control over the ability of lipoplexes to transfect cells (e.g., by application of a chemical or electrochemical stimulus to transform the oxidation state of BFDMA). We have demonstrated that it is possible to reduce the BFDMA in lipoplexes of oxidized BFDMA by treatment with chemical reducing agents (e.g., glutathione or ascorbic acid) [23, 24], and that these treatments can be used to influence physical properties that activate these lipoplexes toward transfection. A recent publication from our group also demonstrates that chemical reduction can be used to activate lipoplexes of oxidized BFDMA in culture media, in the presence of cells, to initiate transfection [24].

In our past studies, we synthesized reduced BFDMA directly and then obtained oxidized BFDMA by subsequent electrochemical oxidation [19-24]. While this electrochemical approach is useful, complete electrochemical oxidation of BFDMA generally requires long times (e.g., 2-3 hours) at high temperatures (75 °C). This current study sought to address these and other practical issues associated with electrochemical oxidation by investigating approaches to the chemical oxidation of BFDMA.

We report here that Fe(III)sulfate can be used to oxidize reduced BFDMA rapidly, quantitatively, and at ambient temperatures. However, lipoplexes formed using chemically oxidized BFDMA behaved differently than lipoplexes prepared using electrochemically oxidized BFDMA in the context of cell transfection (e.g., whereas the latter do not promote high levels of transfection, lipoplexes of chemically oxidized BFDMA do). The results of additional experiments reveal these differences to be a result of residual iron ions present in solutions of chemically oxidized BFDMA, and that treatment with an iron chelating agent (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, EDTA) [28] can be used to produce bulk samples of chemically oxidized BFDMA that do not promote cell transfection. We demonstrate further that (i) these EDTA-treated samples can be chemically reduced by treatment with ascorbic acid to produce samples of reduced BFDMA that do promote transfection, and (ii) lipoplexes formed using EDTA-treated samples can be chemically reduced to activate the lipoplexes and initiate transfection. Our results demonstrate that chemical approaches to the transformation of BFDMA can be used to preserve redox-based ‘on/off’ control over cell transfection demonstrated in past studies using electrochemical methods.

Materials and Methods

Materials

BFDMA was synthesized according to methods published previously [29]. Dodecyltrimethylammonium bromide (DTAB) and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) were purchased from Acros Organics (Morris Plains, NJ). Fe(III)sulfate (Fe2(SO4)3·5H2O; also referred to herein as Fe3+) was purchased from Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) with a purity of at least 97%. Deionized water (18.2 MΩ) was used to prepare all buffers and salt solutions. Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM), Opti-MEM cell culture medium, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fetal bovine serum (FBS), and Lipofectamine 2000 were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Plasmid DNA encoding enhanced green fluorescent protein (pEGFP-N1, >95% supercoiled) and firefly luciferase (pCMV-Luc, >95% supercoiled) were purchased from Elim Biopharmaceuticals, Inc., San Francisco, CA. Bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kits were purchased from Pierce (Rockford, IL). Glo Lysis Buffer and Steady-Glo Luciferase Assay kits were purchased from Promega Corporation (Madison, WI). All commercial materials were used as received without further purification unless otherwise noted.

Preparation of Reduced and Electrochemically Oxidized BFDMA Solutions

Solutions of reduced BFDMA were prepared by dissolving a desired mass of reduced BFDMA in aqueous Li2SO4 (1 mM, pH 5.1) followed by dilution to a desired concentration. Solutions of electrochemically oxidized BFDMA were prepared by electrochemical oxidation of a 1 mM reduced BFDMA solution at 75 °C using a bipotentiostat (Pine Instruments, Grove City, PA) and a three electrode cell to maintain a constant potential of 600 mV between the working electrode and a Ag/AgCl reference electrode, as described previously [19-21, 23]. Platinum mesh (2.5 cm2) was used as the working and counter electrodes. For electrochemical oxidation of BFDMA in D2O (used in SANS analyses described below), 1 mM sodium acetate was added to the BFDMA prior to oxidation to achieve full conversion of reduced BFDMA to oxidized BFDMA. The progress of oxidation was followed by monitoring current passed at the working electrode and by UV/visible spectrophotometry, as described previously [19, 20, 23].

Characterization of the Transformation of Reduced BFDMA upon Addition of Fe3+

Solutions of chemically oxidized BFDMA were prepared by chemical oxidation of solutions of 1 mM reduced BFDMA using a negligible volume (0.5-5 μL) of a concentrated solution of Fe3+ (1.0 M) to obtain the BFDMA/Fe3+ molar ratios described in the text. Time-dependent characterization of chemical oxidation of reduced BFDMA upon addition of Fe3+ was conducted by measuring UV/vis absorbance spectra at wavelengths ranging from 400 to 800 nm. To this end, following the acquisition of an initial wavelength scan of reduced BFDMA solution, Fe3+ was added and the absorbance spectrum of the solution was monitored at predetermined time intervals until a constant absorbance at 630 nm (a wavelength characteristic of the absorbance of oxidized BFDMA) was observed. For experiments involving measurements made on solutions of reduced BFDMA, DTAB was added immediately prior to measurement of absorbance to eliminate clouding observed in BFDMA solutions at concentrations greater than 100 μM. For experiments for which Fe3+ was added to oxidize BFDMA, DTAB was added at the conclusion of each experiment before making an absorbance measurement. We note that DTAB does not absorb light in the visible region of interest (400-800 nm) in these experiments. For experiments in which iron chelating agents were used to investigate the influence of residual Fe2+ and Fe3+ species on the lipoplex activity (see text), solutions of chemically oxidized BFDMA were treated with a 1.5-fold molar excess of EDTA. Subsequent experiments investigating the chemical reduction of EDTA-treated samples of chemically oxidized BFDMA were performed using a 10-fold molar excess of ascorbic acid.

Preparation of Lipoplex Solutions

Lipoplexes of reduced, electrochemically oxidized, or chemically oxidized BFDMA were prepared in the following general manner. A solution of plasmid DNA (24 μg/mL in water) was added to a vortexing solution of aqueous Li2SO4 containing an amount of reduced or oxidized BFDMA sufficient to give the final lipid concentrations and BFDMA/DNA charge ratios (CRs) reported in the text. Total sample volume used for zeta potential and cell transfection experiments was 5 mL, and 50 μL, respectively. Lipoplexes were allowed to stand at room temperature for 20 min before use in subsequent experiments.

General Protocols for Transfection and Characterization of Gene Expression

COS-7 cells used in transfection experiments were grown in clear or opaque polystyrene 96-well culture plates (for experiments using pEGFP-N1 and pCMV-Luc, respectively) at initial seeding densities of 15 103 cells/well in 200 μL of growth medium (90% Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin 100 units/mL, streptomycin 100 μg/mL). After seeding, all cells were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. At approximately 80% confluence, culture medium was aspirated and replaced with 200 μL of serum-free medium (Opti-MEM), followed by addition of 50 μL of a lipoplex solution (to yield a final concentration of 10 μM BFDMA). After 4 h at 37 °C incubation, lipoplex-containing medium was aspirated from all wells and replaced with 200 μL of serum-containing medium. Cells were incubated for an additional 48 h prior to characterization of transgene expression. For experiments conducted using lipoplexes formed from pEGFP-N1, cell morphology and relative levels of EGFP expression were characterized using phase contrast and fluorescence microscopy. For experiments conducted using lipoplexes formed from pCMV-Luc, levels of luciferase expression were characterized using a commercially available luminescence based luciferase assay kit, using the manufacturer's specified protocol. Luciferase expression data were normalized to total cell protein in each respective well using a commercially available BCA protein assay kit.

Characterization of Zeta Potentials of Lipoplexes

Experiments designed to characterize the zeta potentials of lipoplexes were conducted in the following general manner. Samples of lipoplexes formed from either reduced BFDMA, electrochemically oxidized BFDMA, or chemically oxidized BFDMA were prepared as described above. These samples were then diluted using 1 mM Li2SO4 (pH 5). For each sample, 5 mL of lipoplex solution was injected into the inlet of a Zetasizer 3000HS instrument, and measurements were made at ambient temperature using an electrical potential of 150 V. The final BFDMA and plasmid DNA (pEGFP-N1) concentrations were 10 μM and 24 mg/mL, respectively for all samples. These values are the same as those used in the cell transfection experiments described above. A minimum of five measurements was recorded for each sample, and the Henry equation was used to calculate zeta potentials from measurements of electrophoretic mobility. For this calculation, we assumed the viscosity of the solution to be the same as that of water.

Preparation of Samples of Lipoplexes for Characterization by SANS and Cryo-TEM

Samples of lipoplexes formed from BFDMA and plasmid DNA (pEGFP-N1) were prepared in deuterated or aqueous Li2SO4 (1 mM) for SANS and cryo-TEM experiments, respectively. The 1 mM stock solution of BFDMA was diluted with DNA stock solution and vortexed for 5 s. Lipoplexes used in these experiments were formulated at CRs similar to those used in cell transfection experiments (see text), but the absolute concentrations of BFDMA used in the SANS experiments (0.7 to 0.9 mM) were substantially higher than those used in transfection experiments (10 μM). These higher concentrations were necessary to obtain sufficient intensities of scattered neutrons in SANS experiments. To be consistent with the concentrations used in the SANS measurements and also allow better sampling, cryo-TEM analyses of lipoplexes were also performed at these high lipid concentrations.

Characterization of Lipoplexes by SANS

SANS was performed using the CG-3 Bio-SANS instrument at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), Oak Ridge, TN. The incident neutron wavelength was on average 6 Å, with a spread in wavelength, Δλ/λ, of 15 %. Data were recorded at two different sets of sample-to-detector distances (0.3, 6, and 14.5 m or 1 and 14.5 m), giving q ranges from 0.360-0.030, 0.065-0.0065 and 0.03-0.003 Å-1 or from 0.490-0.018 and 0.064-0.003 Å-1, respectively. The two different sets of sample-to-detector distances represent two separate trips to ORNL to perform these analyses. To ensure statistically relevant data, at least 106 counts were collected for each sample at each detector distance. The samples were contained in quartz cells with a 2 mm path length and placed in a sample chamber held at 25.0 ± 0.1 °C. The data were corrected for detector efficiency, background radiation, empty cell scattering, and incoherent scattering to determine the intensity on an absolute scale [22]. The background scattering from the solvent was subtracted. The processing of data was performed using Igor Pro (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR) with a program provided by ORNL. Guinier analysis described in detail elsewhere [22, 30] was used to interpret the scattering. Errors reported for d-spacing were calculated directly from q-values by assuming 2% experiment-to-experiment change in Bragg peak position versus q position (via calibration using silver behenate standards).

Characterization of Lipoplexes by Cryo-TEM

Specimens of lipoplexes were prepared in a controlled environment vitrification (CEVS) system at 25 °C and 100% relative humidity, as previously described [22, 24, 25, 31, 32]. Samples were examined using a Philips CM120 or in a FEI T12 G2 transmission electron microscope operated at 120 kV, with Oxford CT-3500 or Gatan 626 cooling holders and transfer stations. Specimens were equilibrated in the microscope below -178 °C, and then examined in the low-dose imaging mode to minimize electron-beam radiation-damage. Images were recorded at a nominal underfocus of 1-2 μm to enhance phase contrast. Images were acquired digitally by a Gatan MultiScan 791 (CM120) or Gatan US1000 high-resolution (T12) cooled-CCD camera using the Digital Micrograph software package.

Results and Discussion

Characterization of the Chemical Oxidation of Reduced BFDMA Using Fe3+

We selected Fe(III)sulfate (Fe3+) as a model chemical oxidizing agent on the basis of past studies demonstrating that Fe3+ can be used to oxidize ferrocenyl groups, including those present in single-tailed ferrocenyl surfactants [33, 34]. In a series of initial experiments, we characterized the rate and extent of the oxidation of the ferrocenyl groups in solutions of reduced BFDMA after addition of Fe3+ at ambient temperature (25 °C). For all experiments performed in this study, we used BFDMA solutions (0.5 mM) prepared using 1 mM aqueous Li2SO4. Although chemical reduction can also be performed in biologically relevant media, we used this simple electrolyte solution to permit more direct comparisons between solutions of chemically oxidized BFDMA and electrochemically oxidized BFDMA [19, 20, 22-24] (the latter of which requires the use of an electrolyte solution).

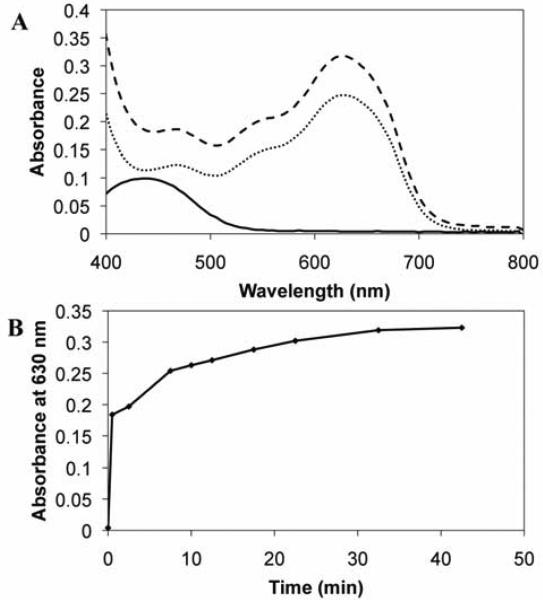

Figure 2A shows the UV/vis absorption spectra of solutions of reduced BFDMA (solid black line), electrochemically oxidized BFDMA (dotted black line), and a sample of reduced BFDMA to which Fe3+ was added (dashed black line; produced by treating solutions of reduced BFDMA with a 1.5-fold molar excess of Fe3+). Inspection of these data reveals that upon treatment of the solution of reduced BFDMA with Fe3+, the absorbance peak at 445 nm (characteristic of solutions of reduced BFDMA) disappeared, and that a new peak at 630 nm (characteristic of solutions of electrochemically oxidized BFDMA) appeared.

Figure 2.

(A) UV/visible absorbance spectra of solutions of reduced BFDMA (solid black line), electrochemically oxidized BFDMA (dotted black line) or chemically oxidized BFDMA (dashed black line). (B) Increase in absorbance maximum (630 nm) of oxidized BFDMA vs time upon treatment of reduced BFDMA solution with 1.5-fold excess of Fe3+ (See Figure S1, Supporting Information for details of the kinetics of oxidation).

In general, the overall shape of the absorption spectrum of the solution of Fe3+-treated BFDMA was similar to that of solutions of electrochemically oxidized BFDMA. We attribute the difference in the magnitudes of the absorbance values of solutions of electrochemically oxidized BFDMA (0.25) and chemically oxidized BFDMA (0.31) at 630 nm to (i) the loss of small amounts of the former during electrochemical oxidation (e.g., by adsorption of BFDMA to the electrode and salt bridge (glass frit) of the electrochemical cell during oxidation; evident by visual inspection) and (ii) the slightly higher turbidity of solutions of chemically oxidized BFDMA (even in the presence of DTAB, which was used to disrupt aggregates and reduce the turbidity of the solution; these differences in absorbance are not the result of residual Fe3+ or Fe2+ species in solution.) Characterization of the time-dependent appearance of the peak in absorbance at 630 nm upon addition of Fe3+ to reduced BFDMA (Figure 2B; see also Figure S1) demonstrated that complete chemical oxidation of BFDMA can be achieved rapidly compared to electrochemical methods (e.g., oxidation is ~90% complete in less than 20 min). These results demonstrate that Fe3+ can be used to oxidize reduced BFDMA rapidly and quantitatively at ambient temperature. The observation that this transformation does not occur instantaneously upon the addition of Fe3+ may be a consequence of the fact that reduced BFDMA self-associates to form submicrometer-scale vesicles in aqueous media (i.e., sequestration of ferrocenyl groups within these assemblies could slow access of Fe3+ to the ferrocene) [35].

Characterization of Cell Transfection Mediated by Lipoplexes of Chemically Oxidized BFDMA

We performed cell-based experiments to determine how DNA lipoplexes formed using chemically oxidized BFDMA behave in the context of cell transfection. These experiments were performed using COS-7 cells and lipoplexes formed using plasmid DNA (pEGFP or pCMV-Luc) encoding enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) or firefly luciferase to permit qualitative and quantitative characterization of levels of transgene expression, respectively. We selected COS-7 cells for use in these studies for two reasons. First, the use of this cell line allowed us to compare our results to those of our past studies on BFDMA-mediated transfection using this cell line [19, 20, 23-25]. Second, COS-7 cells are generally regarded as being relatively easy to transfect [36]. The use of this cell line in these experiments thus provides a more rigorous challenge with respect to characterization of the ability (or the inability) of oxidized BFDMA to transfect cells.

For the experiments described here, we used lipoplexes of reduced BFDMA and oxidized BFDMA (produced either by electrochemical or chemical oxidation) prepared at BFDMA/DNA charge ratios (CRs) of 1.4:1 and 4.2:1, respectively. We note that solutions of lipoplexes formed using oxidized BFDMA (net charge of +3) at a CR of 4.2:1 contain the same molar ratio of BFDMA and DNA as solutions of lipoplexes formed using reduced BFDMA (net charge of +1) at a CR of 1.4:1. These conditions were chosen on the basis of optimized protocols [20] demonstrating that lipoplexes formed using reduced BFDMA at a CR of 1.4:1 mediate high levels of cell transfection, but lipoplexes formed from electrochemically oxidized BFDMA at a CR of 4.2:1 lead to low levels of transfection. For all lipoplex formulations, the overall lipid concentration used for transfection experiments was 10 μM.

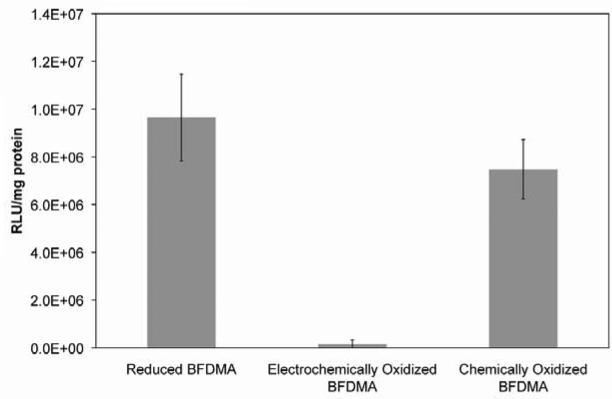

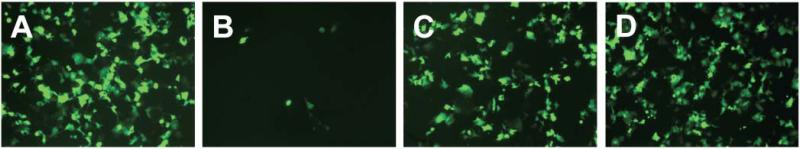

Figure 3 shows fluorescence micrographs of EGFP expression in COS-7 cells treated with lipoplexes formed from (A) reduced BFDMA, (B) electrochemically oxidized BFDMA, and (C) chemically oxidized BFDMA produced as described above. Inspection of these images reveals that lipoplexes of reduced and electrochemically oxidized BFDMA mediated high and low levels of EGFP expression, respectively, consistent with the results of our past studies [19, 20, 23, 24]. The image presented in Figure 3C, however, reveals that lipoplexes prepared using chemically oxidized BFDMA mediated high levels of transgene expression that were qualitatively similar to those using reduced BFDMA (Figure 3A). Figure 4 shows levels of luciferase expression (expressed as relative light units normalized to total cell protein) for cells treated with lipoplexes of reduced BFDMA, electrochemically oxidized BFDMA, or chemically oxidized BFDMA. These data also reveal that lipoplexes of chemically oxidized BFDMA mediated high levels of transgene expression similar to those promoted by lipoplexes of reduced BFDMA, consistent with the qualitative EGFP expression results discussed above (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Representative fluorescence micrographs (100× original magnification, 1194 μm × 895 μm) of confluent monolayers of COS-7 cells showing EGFP expression mediated by lipoplexes of (A) reduced BFDMA, (B) electrochemically oxidized BFDMA and (C) chemically oxidized BFDMA. See text for additional information on lipid/DNA ratios and other experimental details.

Figure 4.

Normalized luciferase expression in COS-7 cells mediated by lipoplexes formed from reduced BFDMA, electrochemically oxidized BFDMA and chemically oxidized BFDMA. See text for additional information on lipid/DNA ratios and other experimental details.

Although the results presented in Figure 2 demonstrate that both electrochemical and chemical methods can be used to oxidize the ferrocenyl groups of BFDMA, it is clear from the results of these cell-based experiments that lipoplexes formed using these two different forms of oxidized BFDMA behave quite differently in the context of cell transfection. Below, we describe the results of characterization experiments that identify features and properties of these lipoplexes that could underlie these differences in cell transfection.

Characterization of the Zeta Potentials of Lipoplexes of Chemically Oxidized BFDMA

The zeta potentials of lipoplexes can affect the efficiency with which lipoplexes are internalized by cells and, thus, influence levels of cell transfection significantly [37, 38]. Our past studies suggested that large differences in the zeta potentials of lipoplexes of reduced and electrochemically oxidized BFDMA (discussed in more detail below) correlate to differences in the extent to which these lipoplexes are internalized by cells (an important first step in the overall cell transfection process) [23, 24]. We performed experiments to characterize and compare the zeta potentials of lipoplexes formed using electrochemically and chemically oxidized BFDMA (prepared as used in the cell transfection experiments above, i.e., at a BFDMA concentration of 10 μM and at BFDMA/DNA CRs of 1.4:1 and 4.2:1 for lipoplexes of reduced and oxidized BFDMA, respectively).

The results shown in Table 1 demonstrate that the average zeta potentials of lipoplexes prepared from electrochemically oxidized BFDMA (approximately –18 mV) were more negative than those of lipoplexes formed from reduced BFDMA (approximately –10 mV). These results are in general agreement with the results of past studies [21, 24]. The average zeta potentials of lipoplexes formed from chemically oxidized BFDMA, however, were positive (approximately +2 mV) and, thus, substantially different from the zeta potentials of lipoplexes of both reduced and electrochemically oxidized BFDMA. We hypothesized that this positive zeta potential was the result of association of lipoplexes with residual Fe2+ and/or Fe3+ species present in solutions of chemically oxidized BFDMA (because a 1.5-fold molar excess of Fe3+ was used to oxidize BFDMA, both Fe2+ and Fe3+ species are present in solution at the end of the oxidation process; these species are not present in solutions of electrochemically oxidized BFDMA). It is possible that the small but positive zeta potentials of these lipoplexes could contribute to more favorable interactions with cell membranes and promote more efficient internalization (and, thus, contribute to higher levels of cell transfection than those promoted by lipoplexes of electrochemically oxidized BFDMA). We note, however, that other factors could also contribute to these observed differences, and we return to a discussion of the impact of changes in zeta potentials on cell transfection again in the discussion below.

Table 1.

Zeta Potentials of Lipoplexes.a

| Sample Type | Zeta Potentials (mV) |

|---|---|

| Lipoplexes of reduced BFDMA | -10 ± 4 |

| Lipoplexes of electrochemically oxidized BFDMA | -18 ± 9 |

| Lipoplexes of chemically oxidized BFDMA | +2 ± 1 |

| Lipoplexes of EDTA-treated chemically oxidized BFDMA | -20 ± 7 |

Lipoplexes were prepared in Li2SO4 and diluted into Li2SO4 so that the final concentration of BFDMA was 10 μM in all cases, and lipid/DNA charge ratios were fixed at 1.4:1 for lipoplexes of reduced BFDMA and 4.2:1 for lipoplexes of oxidized BFDMA (see text for additional details).

Characterization of Lipoplex Nanostructures Using SANS and Cryo-TEM

We used SANS and cryo-TEM to provide insight into potential differences in the nanostructures of lipoplexes of electrochemically and chemically oxidized BFDMA that may underlie differences in cell transfection levels and zeta potentials described above. These experiments were performed in deuterated 1 mM Li2SO4 using lipoplexes formulated at BFDMA/DNA CRs of 1.1:1 and 3.3:1 for lipoplexes of reduced BFDMA and oxidized BFDMA, respectively. We note that these CRs do not correspond exactly to those used in the cell transfection experiments presented in Figures 3 and 4. The CRs used here were chosen to permit more direct comparisons to the results of our past SANS and cryo-TEM analyses of BFDMA lipoplexes [22, 24, 25], which were performed at these slightly different CRs. Those past studies suggested that the nanostructures of lipoplexes formed from BFDMA and DNA do not change substantially with small changes in the BFDMA/DNA CR (at least for lipoplexes formed from reduced BFDMA) [22].

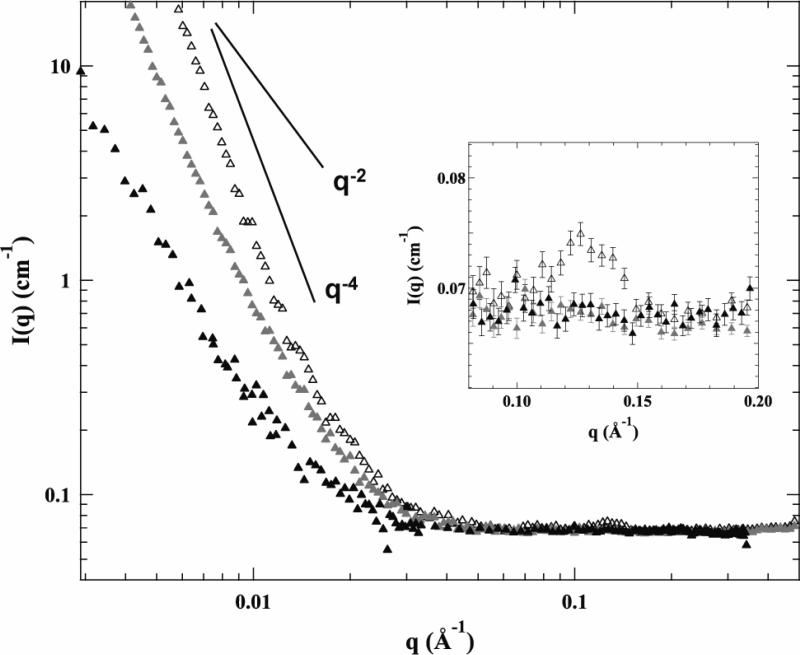

Figure 5 shows SANS spectra of lipoplexes of reduced BFDMA (open black triangles), lipoplexes of electrochemically oxidized BFDMA (solid gray triangles), and lipoplexes of chemically oxidized BFDMA (solid black triangles). The inset in Figure 5 shows the Bragg peaks identified for these complexes. The SANS spectrum of the lipoplexes of reduced BFDMA exhibits a Bragg peak at q=0.12 Å-1 (see also the inset in Figure 5). This peak corresponds to the periodicity of multilamellar lipoplexes formed from BFDMA and DNA in which DNA (thickness of 2.7 nm) is intercalated between lipid bilayers (thickness of 2.5 nm) [22]. This model of lipoplex structure is also confirmed by the results of our cryo-TEM analyses (Figure 6, discussed below). Further inspection of the SANS data for lipoplexes of reduced BFDMA in the low q region of the spectrum reveals a q-4 dependence that is consistent with the presence of polydisperse multilamellar vesicles. Figure 5 also reveals that no Bragg peaks were observed for lipoplexes formed from either electrochemically or chemically oxidized BFDMA. This result indicates the absence of any measurable periodic nanostructures for either of these oxidized BFDMA lipoplex formulations. In addition, the SANS spectra of these complexes in the low q region follows a q dependence of q-3, consistent with the presence of loose aggregate structures rather than a periodic multilamellar structure.

Figure 5.

SANS spectra of lipoplexes of reduced BFDMA (open black triangles), lipoplexes of electrochemically oxidized BFDMA (solid gray triangles), and lipoplexes of chemically oxidized BFDMA (solid black triangles). The inset shows the Bragg peak observed at q=0.12 Å-1.

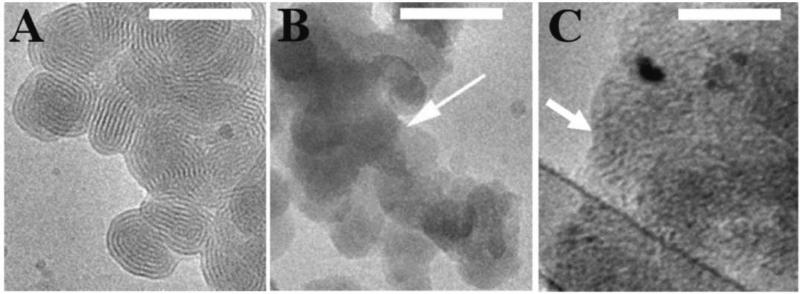

Figure 6.

Cryo-TEM images of (A) lipoplexes of reduced BFDMA, (B) lipoplexes of electrochemically oxidized BFDMA (arrow points to amorphous, nonlamellar structures), and (C) lipoplexes of chemically oxidized BFDMA (arrow points to large aggregates composed of a stack of sheets, superimposed due to the two-dimensional nature of cryo-TEM optics). Scale bars are 100 nm in each image.

Cryo-TEM images of lipoplexes of reduced BFDMA (Figure 6A) revealed spherically-shaped multilamellar structures with a periodicity of 5.1 ± 0.2 nm, consistent with the above-described interpretation of our SANS results (Figure 5). Inspection of cryo-TEM images of lipoplexes of electrochemically oxidized BFDMA (Figure 6B) and chemically oxidized BFDMA (Figure 6C) reveals differences in overall morphology, but that both of these complexes form aggregates without any internal periodicity. In general, these observations are consistent with the q dependence of -3 in the low q region and the absence of a Bragg peak in the SANS spectrum of these lipoplexes (Figure 5). However, further inspection of the cryo-TEM images of these lipoplexes demonstrates that the aggregates formed using chemically oxidized BFDMA appear larger than those formed using electrochemically oxidized BFDMA. This difference in size or extent of aggregation was not detected in the SANS analyses (i.e. both complexes have a q dependence of -3 in the low q region). This may result from the fact that larger aggregates settle more rapidly to the bottom of the cuvettes used for SANS over the time scale of those longer measurements (and, thus, they reside largely out of the path of the incident neutron beam travelling through and being scattered by the sample).

We performed dynamic light scattering (DLS) experiments to further characterize differences in the sizes of aggregates formed using electrochemically or chemically oxidized BFDMA. These measurements were performed using lipoplexes prepared at the same BFDMA/DNA CRs used for SANS and cryo-TEM, but at a lower BFDMA concentration (8 μM) to permit characterization by DLS. These experiments revealed the mean size of lipoplexes of electrochemically oxidized BFDMA to be ~190 nm, but that the average size of lipoplexes formed using chemically oxidized BFDMA was approximately 1500 nm (Figure S2). These results provide further evidence of differences in the physical properties of lipoplexes formed from electrochemically and chemically oxidized BFDMA (and suggest that the apparent difference in the sizes of aggregates shown in Figure 6B-C is not the result of artifacts arising from the preparation of these samples for cryo-TEM analysis).

Investigation of Potential Influences of Residual Fe2+ and Fe3+ on the Properties and Behaviors of Lipoplexes of Chemically Oxidized BFDMA

The results above demonstrate that Fe3+ can oxidize the ferrocenyl groups of BFDMA rapidly and completely at ambient room temperature. However, our results also demonstrate that lipoplexes formed using samples of chemically oxidized BFDMA differ from lipoplexes prepared using electrochemically oxidized BFDMA in several important ways. Foremost among these differences (at least from a functional standpoint) is that lipoplexes of chemically oxidized BFDMA are able to promote high levels of cell transfection that are similar to those mediated by reduced BFDMA. Thus, although the use of Fe3+ presents a practical alternative to electrochemical oxidation, it also appears to have a significant influence on the levels of redox-based ‘on/off’ control over cell transfection that can be achieved using reduced and electrochemically oxidized BFDMA.

Lipoplexes formed using reduced and electrochemically oxidized BFDMA exhibit large differences in zeta potentials, a likely result of differences in the nanostructures of these lipoplexes (as discussed above and shown in Figures 5 and 6, lipoplexes of reduced BFDMA exhibit multilamellar nanostructures, while lipoplexes of electrochemically oxidized BFDMA are amorphous and devoid of periodic nanostructure). Our current results reveal differences in the zeta potentials of lipoplexes of chemically and electrochemically oxidized BFDMA that could also underlie the large differences in cell transfection observed in Figures 3 and 4. Interestingly, however, our current results suggest that these differences in zeta potential do not arise from substantial differences in the nanostructures of these complexes (e.g., as shown in Figures 5 and 6, lipoplexes of chemically and electrochemically oxidized BFDMA both possess amorphous, non-periodic nanostructures). As a final point of discussion, we note that the results of cryo-TEM and DLS experiments reveal that the average size of aggregates in solutions of lipoplexes of chemically oxidized BFDMA is substantially larger (~1500 nm) than the average size of aggregates present in solutions of lipoplexes of electrochemically oxidized BFDMA (~190 nm). The presence of these larger aggregates could arise from differences in the zeta potentials of these lipoplexes, and these larger structures could promote more effective physical delivery of DNA to cells during transfection experiments (e.g., by sedimentation). Although this latter possibility could potentially contribute to the higher levels of transfection observed using lipoplexes of chemically oxidized BFDMA, we note that any fraction of larger aggregates capable of sedimenting more rapidly would also be less likely to be internalized by cells.

The samples of chemically oxidized BFDMA used in this study contain additional Fe2+ and Fe3+ species that are not present in solutions of electrochemically oxidized BFDMA. The presence of these species does not appear to influence the nanostructures of these lipoplexes. However, the presence and association of these ionic species with the surfaces of lipoplexes could influence surface charges (and thus zeta potentials). To investigate the potential influence of these species, we performed experiments using samples of chemically oxidized BFDMA treated with EDTA, a well known chelating agent used to sequester Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions [28].

In a first set of experiments, we performed the oxidation of reduced BFDMA using a 1.5-fold molar excess of Fe3+ (as described above), and then added a 1.5-fold molar excess of EDTA. Characterization of these samples using UV/vis spectrophotometry revealed that the addition of EDTA did not change the overall shape of the absorption spectrum (data not shown), suggesting that addition of EDTA does not promote significant degradation or destruction of ferrocenium ions under these conditions. DLS analysis of lipoplexes formed using EDTA-treated solutions of chemically oxidized BFDMA (Figure S2) revealed the average size of these lipoplexes to be large (~1800 nm) and similar to the average size of lipoplexes prepared using untreated samples of chemically oxidized BFDMA. However, characterization of the zeta potentials of lipoplexes formed using these EDTA-treated solutions revealed values that were substantially lower (more negative) than those formed using untreated samples of chemically oxidized BFDMA (e.g., approximately –20 mV versus +2 mV for lipoplexes formed using untreated BFDMA; see Table 1). This substantially lower zeta potential is similar to that measured for lipoplexes prepared using electrochemically oxidized BFDMA (approximately –18 mV). This change in the zeta potentials of lipoplexes formed using EDTA-treated oxidized BFDMA reflects the affinity of Fe2+ and Fe3+ for EDTA relative to the lipoplexes, but these results do not distinguish potential differences in the relative contributions of these two species to the zeta potentials of lipoplexes in the presence or absence or EDTA.

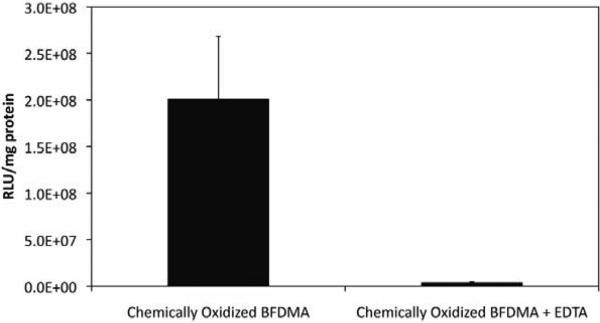

These observations are consistent with the view that the presence of Fe2+ and Fe3+ could influence levels of cell transfection (i.e., help to promote it) through their influence on the zeta potentials of lipoplexes. More generally, these results also suggest a practical and straightforward route to the preparation of samples of chemically oxidized BFDMA that can be used to prepare lipoplexes with properties that are more similar to those of lipoplexes formed using electrochemically oxidized BFDMA (that is, lipoplexes that do not transfect cells significantly). Figure 7A-B shows results of a cell transfection experiment using lipoplexes prepared using pEGFP and either chemically oxidized BFDMA or EDTA-treated samples of chemically oxidized BFDMA, respectively. These results demonstrate clearly that post-oxidation treatment of Fe3+-oxidized BFDMA with EDTA can be used to prepare solutions of oxidized BFDMA that do function, in the context of cell transfection, in ways that ‘recover’ the functional properties of solutions of electrochemically oxidized BFDMA (i.e., to formulate BFDMA lipoplexes that are inactive toward transfection; similar to the results of experiments using electrochemically oxidized BFDMA shown in Figure 3B). Figure 8 shows levels of luciferase expression for populations of cells treated with otherwise identical lipoplexes prepared the pLuc plasmid and either chemically oxidized BFDMA or EDTA-treated chemically oxidized BFDMA. The results of these quantitative experiments confirm the large qualitative differences observed in EGFP expression shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Representative fluorescence micrographs (100× original magnification, 1194 μm × 895 μm) of confluent monolayers of COS-7 cells showing EGFP expression mediated by (A) lipoplexes formed from chemically oxidized BFDMA (similar to the image shown in Figure 3C); (B) lipoplexes formed using chemically oxidized BFDMA treated with EDTA; (C) lipoplexes formed using EDTA-treated oxidized BFDMA treated with a 10-fold molar excess of ascorbic acid (prior to the formation of lipoplexes, see text); (D) lipoplexes formed using EDTA-treated oxidized BFDMA that were chemically reduced by the addition of a 10-fold molar excess of ascorbic acid in the presence of cells (i.e., ascorbic acid was added to lipoplexes after the lipoplexes had been placed in the presence of cells; see text).

Figure 8.

Normalized luciferase expression in COS-7 cells mediated by lipoplexes formed from chemically oxidized BFDMA and chemically oxidized BFDMA treated with EDTA. See text for additional information on lipid/DNA ratios and other experimental details.

Finally, as described in the Introduction, we recently demonstrated that treatment of lipoplexes of electrochemically oxidized BFDMA with the small-molecule chemical reducing agent ascorbic acid can be used to reduce BFDMA and “activate” these otherwise inactive lipoplexes toward cell transfection [24]. We performed experiments demonstrating that EDTA-treated solutions of chemically oxidized BFDMA can also be reduced by treatment with the chemical reducing agent ascorbic acid (as determined by UV/vis spectrophotometry; data not shown). The results of additional cell-based experiments also demonstrated that: (i) lipoplexes formed using these chemically reduced samples of BFDMA (Figure 7C) can promote high levels of cell transfection that are qualitatively similar to those promoted by fresh (as-synthesized) reduced BFDMA (Figure 3A), and (ii) that pre-formed lipoplexes formed using these EDTA-treated samples can be chemically reduced in vitro, in cell culture media and in the presence of cells, to activate lipoplexes toward transfection (e.g., Figure 7D). The results of these experiments, when combined, demonstrate that combinations of chemical oxidation and chemical reduction can be used to achieve levels of redox-based ‘on/off’ control of cell transfection that are similar to those achieved in past studies [23, 24] using electrochemical methods.

Summary and Conclusions

We have demonstrated that the ferrocenyl groups of the cationic, redox-active lipid BFDMA can be oxidized rapidly and quantitatively using a chemical oxidizing agent. This chemical approach to oxidation confers several practical advantages (including the ability to perform oxidation rapidly at ambient temperatures) compared to electrochemical oxidation methods used in past studies for the preparation of bulk samples of oxidized BFDMA. Subsequent experiments demonstrated that BFDMA/DNA lipoplexes prepared using samples of chemically oxidized BFDMA behaved very differently from lipoplexes formed using electrochemically oxidized BFDMA with respect to their ability to promote in vitro cell transfection. While lipoplexes of electrochemically oxidized BFDMA do not transfect cells efficiently, lipoplexes formed using chemically oxidized BFDMA promoted levels of transfection that were high and similar to levels mediated by lipoplexes of reduced BFDMA.

Physical characterization experiments revealed that lipoplexes of chemically and electrochemically oxidized BFDMA both have amorphous, non-periodic nanostructures, but that these lipoplexes differ significantly in terms of both size and zeta potential. The results of additional experiments suggested that these differences in zeta potential likely arise from the presence of residual Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions present in samples of chemically reduced BFDMA. In support of this hypothesis, we demonstrated that the addition of EDTA to solutions of chemically oxidized BFDMA can be used as a practical and straightforward method to produce samples of chemically oxidized BFDMA that are functionally similar to samples of electrochemically oxidized BFDMA (e.g., to produce lipoplexes that do not transfect cells significantly). Finally, our results demonstrate that (i) EDTA-treated samples of chemically oxidized BFDMA can be reduced by treatment with a chemical reducing agent to produce samples of reduced BFDMA that do promote high levels of cell transfection, and (ii) lipoplexes formed using these EDTA-treated samples can be chemically reduced in the presence of cells to activate the lipoplexes and initiate transfection. Overall, the results of this study demonstrate that combinations of chemical oxidation and chemical reduction can be used to achieve levels of redox-based ‘on/off’ control of cell transfection that are similar to those achieved in past studies using electrochemical methods.

Supplementary Material

Research Highlights.

The redox-active ferrocenyl lipid BFDMA can be chemically oxidized using FeIII.

Chemically oxidized BFDMA transfects cells; electrochemically oxidized BFDMA doesn't.

Characterization reveals similar nanostructures but differences in zeta potentials.

Treatment with EDTA restores the “inactivity” of chemically oxidized BFDMA.

Redox-control of transfection can be achieved by adding chemical reducing agents.

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by the NIH (1 R21 EB006168) and the National Science Foundation (CBET-0754921). We gratefully acknowledge S. Hata and H. Takahashi for assistance with the synthesis of BFDMA, and the support of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in providing the neutron facilities use in this work. Cryo-TEM work was carried out at the Technion Soft Matter Electron Microscopy Laboratory with the financial support of the Technion Russell Berrie Nanotechnology Institute (RBNI).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Felgner PL, Gadek TR, Holm M, Roman R, Chan HW, Wenz M, Northrop JP, Ringold GM, Danielsen M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1987;84:7413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zabner J. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1997;27:17. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(97)00019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kabanov AV, Felgner PL, Seymour LW. Self-Assembling Complexes for Gene Delivery: From Laboratory to Clinical Trial. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wasungu L, Hoekstra D. J. Control. Release. 2006;116:255. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Ilarduya CT, Sun Y, Duzgunes N. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010;40:159. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang FX, Hughes JA. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998;242:141. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wetzer B, Byk G, Frederic M, Airiau M, Blanche F, Pitard B, Scherman D. Biochem. J. 2001;356:747. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3560747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo X, Szoka FC. Acc. Chem. Res. 2003;36:335. doi: 10.1021/ar9703241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang ZH, Li WJ, MacKay JA, Szoka FC. Mol. Ther. 2005;11:409. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Budker V, Gurevich V, Hagstrom JE, Bortzov F, Wolff JA. Nat. Biotechnol. 1996;14:760. doi: 10.1038/nbt0696-760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerasimov OV, Boomer JA, Qualls MM, Thompson DH. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1999;38:317. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(99)00035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu J, Munn RJ, Nantz MH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:2645. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meers P. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001;53:265. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00205-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prata CAH, Zhao YX, Barthelemy P, Li YG, Luo D, McIntosh TJ, Lee SJ, Grinstaff MW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:12196. doi: 10.1021/ja0474906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang XX, Prata CAH, Berlin JA, McIntosh TJ, Barthelemy P, Grinstaff MW. Bioconjug. Chem. 2011;22:690. doi: 10.1021/bc1004526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagasaki T, Taniguchi A, Tamagaki S. Bioconjug. Chem. 2003;14:513. doi: 10.1021/bc0256603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolff JA, Rozema DB. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:8. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu YC, Le Ny ALM, Schmidt J, Talmon Y, Chmelka BF, Lee CT. Langmuir. 2009;25:5713. doi: 10.1021/la803588d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abbott NL, Jewell CM, Hays ME, Kondo Y, Lynn DM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:11576. doi: 10.1021/ja054038t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jewell CM, Hays ME, Kondo Y, Abbott NL, Lynn DM. J. Control. Release. 2006;112:129. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hays ME, Jewell CM, Kondo Y, Lynn DM, Abbott NL. Biophys. J. 2007;93:4414. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.107094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pizzey CL, Jewell CM, Hays ME, Lynn DM, Abbott NL, Kondo Y, Golan S, Tahnon Y. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:5849. doi: 10.1021/jp7103903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jewell CM, Hays ME, Kondo Y, Abbott NL, Lynn DM. Bioconjug. Chem. 2008;19:2120. doi: 10.1021/bc8002138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aytar BS, Muller JPE, Golan S, Hata S, Takahashi H, Kondo Y, Talmon Y, Abbott NL, Lynn DM. J. Control. Release. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.09.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Golan S, Aytar BS, Muller JPE, Kondo Y, Lynn DM, Abbott NL, Talmont Y. Langmuir. 2011;27:6615. doi: 10.1021/la200450x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilkinson G, Rosenblum M, Whiting MC, Woodward RB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1952;74:2125. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bard AJ, Faulkner LR. Electrochemical methods : fundamentals and applications. Wiley; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Přibil R. Analytical applications of EDTA and related compounds. Pergamon Press; Oxford, New York: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoshino N, Shoji H, Kondo Y, Kakizawa Y, Sakai H, Abe M. J. Jpn. Oil Chem. Soc. 1996;45:769. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guinier A, Fournet G. Small Angle X-ray Scattering. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1955. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bellare JR, Davis HT, Scriven LE, Talmon Y. J. Electron Microsc. Tech. 1988;10:87. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1060100111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Danino D, Bernheim-Groswasser A, Talmon Y. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2001;183:113. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gallardo BS, Hwa MJ, Abbott NL. Langmuir. 1995;11:4209. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bennett DE, Gallardo BS, Abbott NL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:6499. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kakizawa Y, Sakai H, Nishiyama K, Abe M, Shoji H, Kondo Y, Yoshino N. Langmuir. 1996;12:921. [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Gaal EVB, van Eijk R, Oosting RS, Kok RJ, Hennink WE, Crommelin DJA, Mastrobattista E. J. Control. Release. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.05.001. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tomlinson E, Rolland AP. J. Control. Release. 1996;39:357. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sakurai F, Inoue R, Nishino Y, Okuda A, Matsumoto O, Taga T, Yamashita F, Takakura Y, Hashida M. J. Control. Release. 2000;66:255. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00280-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.