Abstract

Neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2), characterized by tumors of the nervous system, is a result of functional loss of the NF2 gene. The NF2 gene encodes Merlin (moesin-ezrin-radixin-like protein), an ERM (Ezrin, Radixin, Moesin) protein family member. Merlin functions as a tumor suppressor through impacting mechanisms related to proliferation, apoptosis, survival, motility, adhesion, and invasion. Several studies have summarized the tumor intrinsic mutations in Merlin. Given the fact that tumor cells are not in isolation, but rather in an intricate, mutually sustaining synergy with their surrounding stroma, the dialogue between the tumor cells and the stroma can potentially impact the molecular homeostasis and promote evolution of the malignant phenotype. This review summarizes the epigenetic modifications, transcript stability, and post-translational modifications that impact Merlin. We have reviewed the role of extrinsic factors originating from the tumor milieu that influence the availability of Merlin inside the cell. Information regarding Merlin regulation could lead to novel therapeutics by stabilizing Merlin protein in tumors that have reduced Merlin protein expression without displaying any NF2 genetic alterations.

Keywords: Merlin, NF2, neurofibromatosis, stability, tumor microenvironment

Introduction

Neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) is an autosomal dominant disease affecting 1 in 30,000 children and young adults [1]. This disease is caused by a loss of heterozygosity of the NF2 (neurofibromatosis-2) gene located on chromosome 22q12 [2]. NF2 is a classical tumor suppressor gene that is frequently inactivated or its expression lost as a result of mutations in tumors of the nervous system such as schwannomas, meningiomas, and ependymomas [3-7]. While infrequent, loss of NF2 function due to mutations has been documented in other non-nervous system cancers such as mesotheliomas [8-10], colorectal cancer [11], prostate cancer [12], melanoma and thyroid cancer [13]. The presence of mutations in non-nervous system tumors accompanied by loss of NF2 function suggests that this tumor suppressor functions in a broad range of tissue types.

Merlin, also known as schwannomin or neurofibromin 2 was first discovered in 1993 as the protein encoded by the NF2 gene [14, 15]. Merlin is a member of the Band 4.1 family of cytoskeletal linker proteins that include the ERM (Ezrin, Radixin, Moesin) proteins [16]. Traditionally, proteins of this family function to process signals from the extracellular matrix and transmit these signals downstream to proteins inside the cell. Loss of Merlin function lends cells of the nervous system to unchecked proliferation and motility which results in the formation of the non-malignant tumors that NF2 patients present. Loss of Merlin is embryonic lethal in mice, indicating that Merlin is a critical molecule expressed during normal embryonic development [17, 18]. Moreover, heterozygous Merlin knockout mice (Nf2+/-) develop a series of highly metastatic tumors including hepatocellular carcinomas, fibrosarcomas, and osteosarcomas [19]. Cumulatively, this suggests that Merlin may function to inhibit tumor growth and progression in a variety of cell types. This review will focus on Merlin’s tumor suppressor function with a large portion devoted to the various mechanisms by which Merlin is regulated.

Merlin Functions as a Tumor Suppressor

Merlin has been shown to inhibit tumor growth and suppress malignant activity of cancer cells through multiple mechanisms. There are three main mechanisms by which Merlin acts to inhibit tumor growth: Contact-dependent growth inhibition, decreased proliferation, and increased apoptosis. Merlin initially was discovered to reverse the Ras-induced phenotype and restore contact-inhibition of growth [20]. Morrison et al showed that Merlin disrupts the Ras and Rac signaling pathways leading to contact-dependent growth inhibition [21]. Evidence suggests that Merlin can suppress Ras-induced transformation through several mechanisms including binding to RalGDS (Ral guanine nucleotide dissociation stimulator) [22], binding to and inhibiting p21-activated kinase [23, 24], and inhibiting Rac/Cdc42 [25]. More recently, Yi et al demonstrated that Merlin complexes with the tight junction-associated protein, Angiomotin, and functions to suppress cell growth by inhibiting Rac1 and Ras-MAPK signaling [26].

Several studies have revealed the ability of Merlin to negatively regulate cell growth and proliferation [27-29]. Kim et al showed that Merlin can induce apoptosis upon over-expression, in part by causing degradation of Mdm2 leading to the increased stability and overall tumor suppressor function of p53 [30]. Others have shown that Merlin can inhibit cell cycle progression through suppression of PAK1-mediated expression of Cyclin D1 [31]. Merlin’s function as a tumor suppressor by negative regulation of cell proliferation and induction of apoptosis is conserved in Drosophila [32]. Merlin can also reduce cell proliferation by binding to the cytoplasmic tail of the CD44 receptor. This binding inhibits the interaction of Hyaluronic Acid (HA) with CD44 and suppresses downstream signaling events [28, 33]. More recent studies have focused on previously undefined roles for Merlin such as nuclear translocation to inhibit the E3 ubiquitin ligase CRL4 (DCAF1) resulting in decreased proliferation in schwannomas [34, 35]. In addition, Merlin has been shown to sequester EGFR in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and halt downstream signaling [36, 37] resulting in decreased cell proliferation. Based on this information, a clinical trial was developed to study the effect of erlotinib (a small molecule inhibitor of EGFR) in patients with progressive vestibular schwannoma. The study concluded that there was no tumor response using this inhibitor alone suggesting that Merlin’s tumor suppressor effect is not mediated solely through EGFR [38]. James et al showed that constitutively active mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) in Merlin-deficient meningioma cells led to increased cell growth [39]. NF2 patient tumors as well as Nf2-deficient MEFs displayed elevated mTORC1 signaling. Re-introduction of Merlin suppressed mTORC1 signaling. This group also found that Merlin inhibits mTOR signaling through a novel PI3-Kinase/AKT-independent mechanism which may lead to combination therapies including rapamycin or other mTOR inhibitors. Although Merlin has been shown to inhibit several signaling pathways that are important for tumor growth and progression, it is likely that future studies will reveal many more aspects of Merlin activity. Merlin regulation studies have largely been focused on mutational events. However, there are other important regulatory mechanisms determining Merlin’s availability in a given cell. These include epigenetic alterations, transcript stability, and post-translational modifications. There is a significant body of literature that details the various mutations associated with loss of Merlin [40, 41]. This review focuses on aspects of Merlin regulation that include epigenetics, transcript stability and post-translational modifications that are influenced by the dialogue between the tumor cells and their microenvironment.

Epigenetic Modifications

Although mutations in the NF2 gene cause tumors of the nervous system, there are likely multiple mechanisms that account for the inactivation of the Merlin protein. Promoter methylation has been shown to cause silencing of several tumor suppressor genes including E-cadherin [42], p16 [43], and VHL [44]. Although there are likely several reasons for Merlin inactivation, promoter methylation is the only epigenetic modification that has been associated with changes in Merlin expression. Thus far there is no available literature on promoter deacetylation with regard to regulation of Merlin. Kino and colleagues found that nearly 60% of tumors from schwannoma patients displayed methylation of the NF2 promoter at three different sites within a CpG island. They also noted that Merlin mRNA expression was consistent with the methylation status [45]. Another study confirmed NF2 promoter methylation as a frequent event in schwannomas although at a much lower rate [46]. More recently, it was determined that there were a significant number of sporadic vestibular schwannoma patients that did not exhibit methylation of wild-type NF2 (>40%) [47]. Given the discrepancy regarding NF2 methylation in schwannomas, several studies aimed to determine the methylation status in other tumors of the nervous system such as meningiomas and ependymomas. One study confirmed that NF2 methylation was a rare event (1 of 21) in meningioma patients [48], with another study only detecting methylation at one CpG site in 1 out of 12 tumor samples [49]. An independent study determined that NF2 methylation occurred in less than 10% of ependymoma cases analyzed [50]. It appears that promoter methylation may be important for NF2 regulation, but further investigation is required to confidently make this assertion.

mRNA Stability

Transcript stability is another important aspect that controls tumor suppressor protein expression. Tumor suppressors such as p53 [51] and p21 [52] are known to be regulated at the mRNA level by other proteins and miRNAs. Evidence is inconclusive as to whether Merlin mRNA stability plays a role in tumor progression and also which mechanisms (miRNA signaling or mutational events) are important for Merlin transcript stability. Since there are no studies yet concerning regulation of Merlin mRNA by miRNAs, this section will be centered on whether mutational events are necessary for stability of Merlin mRNA. Hoang-Xuan et al found that Merlin transcript levels are not altered in gliomas [53], while Jacoby et al determined that different mutations resulted in varying degrees of Merlin mRNA expression in NF2 and schwannomatosis [54]. Another study in meningiomas showed that tumors from patients harboring NF2 mutations had 10-fold lower Merlin transcript levels [55]. Deguen et al. showed that 11 of 18 human malignant mesothelioma (HMM) cell lines exhibited decreased Merlin transcript levels, 4 of which displayed no detectable mutations [56]. With the limited available literature focusing on Merlin transcript stability, it appears that a reduction in Merlin mRNA levels is associated with mutations of the NF2 gene. Moreover, in the absence of mutations, Merlin transcript stability is unaltered. Three independent studies confirmed the absence of mutations in the NF2 gene in breast cancer [57-59]. Kanai et al reported no mutations of NF2 upon analysis of 68 patient samples, Arakawa et al detected no mutations in samples from 55 patient tissues, and Yaegashi et al observed a mutation in only 1 out of 60 patient tissues [57-59]. Cumulatively, these studies suggested that mutation of the NF2 gene is an infrequent event in breast cancer. Our recent study confirmed a lack of change in Merlin transcript levels in advanced breast cancer compared with normal breast tissues [60]. Although there are correlative results concerning Merlin transcript stability, more investigation into this area of Merlin regulation is needed.

Post-translational Regulation of Merlin

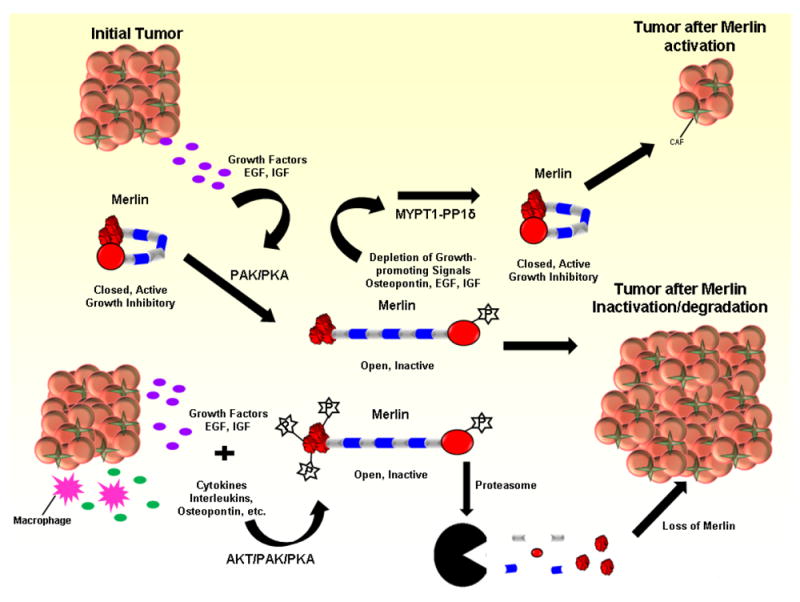

The ERM proteins function as molecular linkers by connecting the cytoskeleton with the plasma membrane [61]. Although the ERM proteins and other related proteins share a central α-helical domain, Merlin lacks an actin-binding motif that is present at the carboxy-terminus in other ERM proteins [62, 63]. This suggests that Merlin may have functions distinct from other ERM family members. Merlin is able to form homodimers with itself and also heterodimers with other ERM protein family members via head-to-tail intra- and inter-molecular associations [64-66] (Figure 1). Merlin’s tumor suppressive activity is dependent on its ability to form a head-to-tail association resulting in a closed, active conformation [27] (Figure 1). A recent crystallographic study suggested that the “closed” conformation of Merlin is in fact an “open” dimer of two Merlin molecules and that this association is responsible for Merlin’s tumor suppressor activity [67]. Myosin phosphatase MYPT1-PP1δ dephosphorylates Merlin at Ser518 in response to high cell density or serum withdrawal and thereby activates Merlin [28, 68] (Figure 1). However, the oncogene protein kinase C-potentiated phosphatase inhibitor of 17 kDa (CPI-17) has been shown to inhibit Merlin activity in mesothelioma by inhibiting the targeting subunit of MYPT1-PP1δ [68, 69] (Table 1).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the effect of Merlin activity/stability on tumorigenesis.

Shown in the schematic is the effect of the growth-promoting cytokines (EGF, IGF, osteopontin etc.) that are either produced by the tumor or are available to the tumor as a component of its microenvironment. The mitogenic response-stimulated phosphorylation of Merlin protein by PKA/PAK/AKT causes Merlin to switch to open, inactive conformation upon its phosphorylation at Serine 518. Phosphorylation of Merlin at Threonine 230/Serine 315 causes Merlin to be marked for proteasomal degradation, leading to the loss of availability of Merlin to function as a tumor suppressor, promoting subsequent malignant progression. MYPT1-PP1δ dephosphorylates Merlin allowing Merlin to fold back into closed, active conformation. This conformation permits Merlin to perform its tumor suppressor function. (CAF represents cancer associated fibroblasts)

Table 1.

Known phosphorylation sites and their effect on Merlin activity/stability.

| Phosphorylation Site | Kinase/Phosphatase | Result | Functional Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serine 10 | PKA/AKT | May target Merlin for degradation | Altered cell morphology, growth permissive | Laulajainen et al. |

| Threonine230/Serine 315 | PAK1/2, AKT | Targets Merlin for proteasomal degradation | Growth permissive | Ye et al., Tang et al., Morrow et al. |

| Serine 518 | PKA, PAK1 Myosin phosphatase (MYPT1-PP1δ) |

Switches Merlin to open conformation | Growth permissive | Sherman et al., Morrison et al., Kissil et al., Xiao et al., Rong et al., Thaxton et al., Jin et al., Thurneysen et al. |

Merlin acts as a mediator of extracellular signals to intracellular proteins. In the context of its microenvironment, the tumor cells are recipients of a multitude of extracellular cyto/chemokines, all of which profoundly impact the tumor cell behavior. The reactive stroma surrounding the tumor engages in a two-way dialogue with the tumor cells. The tumor milieu comprises infiltrating immune cells, complement proteins, endothelial cells, pericytes and growth inhibitory as well as growth promoting cytokines. Inflammatory conditions in the tumor microenvironment promote proliferation and survival of malignant cells, angiogenesis, metastasis, subversion of adaptive immunity, response to hormones and chemotherapeutic agents. This tumor microenvironment is also rich in cytokines and growth factors that can enhance many signaling pathways.

In response to growth factors, low confluence in culture, or cell/substrate attachment, Merlin is phosphorylated at Ser518 by either cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) or p21-activated kinase 1/2 (PAK1/2). This phosphorylation results in an open, inactive conformation and loss of tumor-suppressor activity of Merlin [27, 70-73] (Figure 1, Table 1). NF2 missense mutations in either the N-terminus or C-terminus maintain Merlin in an “open” conformation, one that does not suppress cell growth [74]. In response to growth factors such as EGF (epidermal growth factor) or IGF (insulin growth factor) that are abundant in the tumor milieu, AKT phosphorylates Merlin at Thr230 and Ser315. This phosphorylation targets Merlin for proteasomal degradation by ubiquitination [75] (Table 1). A recent study revealed Ser10 as a novel AKT phosphorylation site that targets Merlin for proteasomal degradation [76] (Table 1).

We recently demonstrated in breast cancer that the availability of Merlin protein (assessed by immunohistochemistry and subsequent scoring) was compromised despite no significant changes at the transcript level. In breast cancer Merlin protein is targeted for degradation by AKT-mediated phosphorylation at Ser315 in response to the tumor microenvironment-associated cytokine, osteopontin. Our study demonstrated that breast tissues displaying loss of Merlin expression show a concomitant increase in osteopontin expression as determined by immunohistochemistry in 77% (58 of 75) of patient tissues analyzed [60]. Osteopontin is a secreted positive regulator of tumor progression and metastasis [77, 78] that is readily available in the tumor microenvironment and elevated in multiple cancer types including advanced breast cancer [79-82]. Osteopontin promotes pro-inflammatory conditions of the tumor milieu [83] and acts as an effector of tumor progression and metastasis at several levels. Osteopontin signals via multiple receptors including several integrins and CD44, activates NF-κB, PI-3-kinase and AKT signaling and enhances malignant attributes [77].

While osteopontin induced ubiquitin-mediated degradation of endogenous (wild-type) Merlin in the breast cancer cells, an exciting aspect of this study was that a degradation-resistant Merlin mutant was able to suppress malignant activity of breast cancer cells even in the presence of osteopontin. This suggests a novel mechanism of Merlin regulation, as well as an opportunity for therapeutic intervention in tumors that display elevated levels of osteopontin or other growth factors such as EGF, either in the tumor cells themselves or in the extracellular milieu. Thus, Merlin is modulated by factors extrinsic to the tumor itself, necessitating the need to assess the Merlin at the protein level rather than simply evaluating tumor-intrinsic genetic mutations in Merlin. More work is necessary to determine the full implications of post-translation modifications of Merlin protein and when these modifications are important for disease.

Discussion

The vast majority of literature concerning Merlin focuses on mutational events within the NF2 gene, resulting in a non-functional Merlin protein. Given that the topic of mutational events has been widely discussed, this review has concentrated on the stability of Merlin protein in the absence of mutational events. At this point, it is unclear whether Merlin protein can be regulated by epigenetic modifications such as promoter methylation. There have been relatively few studies aimed at uncovering the role of Merlin mRNA stability in tumor progression. It appears that further efforts are warranted since there seems to be a correlation between mutational events and overall transcript levels. However, there is little evidence that Merlin mRNA stability plays a role in tumor progression in the absence of deleterious mutations. Despite the fact that NF2/Merlin loss has been studied extensively at the genomic level, there have been relatively few studies focusing on post-translational modifications. These studies will be important in malignancies like breast cancer where no mutational events are detected. A loss of Merlin protein expression may still occur without any change at the transcript level [60]. More work is necessary in determining the exact pathways that lead to phosphorylation which seems to inhibit Merlin tumor suppressor activity. Further investigation into mechanisms of dephosphorylation is also warranted. The lone Merlin phosphatase, MYPT1-PP1δ, has been established as a positive regulator of Merlin tumor suppressor activity by relegating Merlin to its closed, active confirmation. However, there is little knowledge about its expression and activity levels in cancers negative for Merlin mutations. To date, no phosphatase(s) have been identified that regulate Merlin stability. The identification of these potential phosphatases could lead to the development of therapies aimed at stabilizing Merlin protein.

Merlin is not the only tumor suppressor that is regulated at the level of protein stability. Degradation of the p53 and Rb tumor suppressor genes by Mdm2 have been well documented to contribute to tumorigenesis [84]. In breast cancer, it has recently been demonstrated that the nucleolar protein ZNF668 (zinc finger protein 668) can inhibit proliferation in vitro and tumorigenicity in vivo by increasing the stability of p53 [85]. Moreover, in lung cancer a recent report showed that the anti-apoptotic protein TCTP (translationally controlled tumor protein) promotes the degradation of p53 protein [86] which leads to reduced apoptosis. Inhibition of TCTP leads to stabilized p53 and increased apoptotic activity. Furthermore, the E3 ubiquitin ligase Itch was found to negatively regulate the large tumor suppressor (LATS1) by targeting LATS1 for polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation [87]. Upon knockdown of Itch, endogenous LATS1 proteins were stabilized, suggesting that Itch expression levels are important for the post-translational regulation of the LATS1 tumor suppressor. In breast cancer, the tumor suppressor PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog) is frequently downregulated at the protein level in the absence of promoter methylation or genetic alterations [88-90]. Yim et al demonstrated that enhanced binding of E3 ubiquitin ligase leads to ubiquitination and degradation of PTEN [91]. Conversely, evidence suggests that PICT-1 (protein interacting with carboxyl terminus 1) physically interacts with PTEN, promotes C-terminal phosphorylation, and enhances PTEN protein stability in MCF7 breast cancer cells [92]. Further, protein kinase CK2 was shown to phosphorylate PTEN on C-terminal serine/threonine residues leading to increased protein stability [93]. Though the importance of tumor suppressor stability regulation is becoming clearer, the extracellular signals that dictate this stability have yet to be elucidated. However, our laboratory recently found in breast cancer that the growth and metastasis-promoting inflammatory cytokine, osteopontin, signals the degradation of the tumor suppressor Merlin mediated by AKT phosphorylation [60]. Moreover, it is important to note that osteopontin is readily available in the tumor microenvironment. The expression of osteopontin is increased in advanced grade breast tumors. Our study demonstrated that low Merlin expression correlated with high osteopontin expression as determined by immunohistochemistry in 77% (58 of 75) of patient tissues. This provides evidence that the tumor microenvironment can play a critical role in post-translational stability of tumor suppressor proteins.

Given this information, it seems logical that proteasome inhibition might serve as a critical therapeutic strategy. Indeed, there have been numerous clinical trials conducted using the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib as a single agent in non-small cell lung cancer [94], androgen-independent prostate carcinoma [95], as well as multiple myeloma and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma [96]. Bortezomib has been approved for use in certain subsets of patients with relapsed/refractory myeloma after data showed bortezomib induced a better overall response rate than the previous standard dexamethasone [97, 98]. In cases where chemoresistance is evident, bortezomib has been combined with several chemotherapy agents including docetaxel [99], pegylated liposomal doxorubicin [100], and carboplatin [101] among others. In metastatic breast cancer bortezomib has been combined with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in a phase II clinicial trial showing minimal activity [102]. A separate phase II trial was conducted in patients with endocrine-resistant metastatic breast cancer combining anti-hormonal treatments with bortezomib. This study similarly showed no objective antitumor response [103] suggesting that proteasome inhibition is not sufficient for treatment of advanced breast cancer even when combined with other chemotherapeutic agents.

Given the fact that tumor cells are not in isolation, but rather in an intricate, mutually sustaining synergy with their surrounding stroma, the dialogue between the tumor cells and the stroma can potentially impact the molecular homeostasis and promote evolution of the malignant phenotype. This highlights the need for additional methods of Merlin stabilization, in tumors showing no mutations in NF2 gene, such as inhibition of the activity of tumor-promoting cytokines (or their receptors) that are readily available in the tumor microenvironment.

While the majority of information regarding loss of Merlin function has been centered on mutational events leading to non-functional Merlin protein, this review has focused on stability of Merlin protein. Post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation have been documented to regulate Merlin stability in the absence of mutations. Our recent report demonstrated that a tumor microenvironment-associated cytokine, osteopontin, targets Merlin for degradation mediated by AKT phosphorylation in breast cancer. If we can target tumor-associated molecules such as cytokines and growth factors or their receptors, we could stabilize tumor suppressor proteins like Merlin within the cell. This approach may lead to tumor reduction in tissues that display no mutational events in the NF2 gene. In tumors that have lost Merlin expression, the AKT pathway activation is increased [104, 105]. This provides another avenue for therapeutic intervention. There is a significant amount of research underway to target AKT. There are several clinical trials in all different phases currently aimed at targeting the AKT pathway in multiple cancer types including lymphoma, head and neck cancer, melanoma, and breast cancer. While it is still early, targeting the AKT pathway shows promise as the inhibitor triciribine was well-tolerated and showed pharmacodynamic activity as measured by decreased active AKT in a phase I trial in patients with advanced hematologic malignancies, including refractory/relapsed acute myelogenous leukemia [106]. This inhibitor can also suppress growth in breast cancer cell lines that have endogenously high levels of AKT, but not in tumors that contain low levels of AKT [107]. Perifosine is an oral AKT inhibitor that inhibits cell growth concomitant with an increase in apoptosis in breast cancer models [108]. Given this information, it appears that drugs aimed at downstream effector molecules hold significant promise in malignancies that lack active tumor suppressor proteins. In addition, drugs aimed at inhibiting activity of tumor-associated cytokines or their receptors may result in stabilization of tumor suppressor proteins like Merlin, possibly leading to tumor reduction. This strategy holds enormous potential as the role of stabilizing tumor suppressor proteins in patients has been vastly understudied.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by NIH grant R01CA138850 to L.A.S. This review was conceptualized at Mitchell Cancer Institute, University of South Alabama.

Abbreviations

- AKT

Protein kinase B

- Cdc42

Cell division control protein 42 homolog

- CpG

Cytosine-phosphate-guanine

- CPI-17

C-potentiated phosphatase inhibitor of 17 kDa

- EGF

Epidermal growth factor

- EGFR

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- ERM

Ezrin, Radixin, Moesin

- HA

Hyaluronic acid

- HMM

Human malignant mesothelioma

- IGF

Insulin growth factor

- LATS1

Large tumor suppressor 1

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MEF

Mouse embryonic fibroblast

- miRNA

micro RNA

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- MYPT1-PP1δ

Myosin phosphatase targeting subunit1-protein phosphatase1 delta

- NF2

Neurofibromatosis type 2

- NF2

Neurofibromin 2

- PAK

p21-activated kinase

- PICT-1

Protein interacting with carboxyl terminus 1

- PKA

cAMP-dependent protein kinase

- PTEN

Phosphatase and tensin homolog

- RalGDS

Ral guanine nucleotide dissociation stimulator

- RNA

Ribonucleic acid

- Ser

Serine

- TCTP

Translationally controlled tumor protein

- Thr

Threonine

- VHL

Von-Hippel Lindau

- ZNF668

Zinc finger protein 668

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Evans DG, Howard E, Giblin C, Clancy T, Spencer H, Huson SM, Lalloo F. Birth incidence and prevalence of tumor-prone syndromes: estimates from a UK family genetic register service. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:327–332. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scoles DR. The merlin interacting proteins reveal multiple targets for NF2 therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1785:32–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Irving RM, Moffat DA, Hardy DG, Barton DE, Xuereb JH, Maher ER. Somatic NF2 gene mutations in familial and non-familial vestibular schwannoma. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:347–350. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.2.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruttledge MH, Sarrazin J, Rangaratnam S, Phelan CM, Twist E, Merel P, Delattre O, Thomas G, Nordenskjold M, Collins VP, et al. Evidence for the complete inactivation of the NF2 gene in the majority of sporadic meningiomas. Nat Genet. 1994;6:180–184. doi: 10.1038/ng0294-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacoby LB, MacCollin M, Louis DN, Mohney T, Rubio MP, Pulaski K, Trofatter JA, Kley N, Seizinger B, Ramesh V, et al. Exon scanning for mutation of the NF2 gene in schwannomas. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:413–419. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.3.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ueki K, Wen-Bin C, Narita Y, Asai A, Kirino T. Tight association of loss of merlin expression with loss of heterozygosity at chromosome 22q in sporadic meningiomas. Cancer research. 1999;59:5995–5998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sainz J, Huynh DP, Figueroa K, Ragge NK, Baser ME, Pulst SM. Mutations of the neurofibromatosis type 2 gene and lack of the gene product in vestibular schwannomas. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:885–891. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.6.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bianchi AB, Mitsunaga SI, Cheng JQ, Klein WM, Jhanwar SC, Seizinger B, Kley N, Klein-Szanto AJ, Testa JR. High frequency of inactivating mutations in the neurofibromatosis type 2 gene (NF2) in primary malignant mesotheliomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:10854–10858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.10854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sekido Y, Pass HI, Bader S, Mew DJ, Christman MF, Gazdar AF, Minna JD. Neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) gene is somatically mutated in mesothelioma but not in lung cancer. Cancer research. 1995;55:1227–1231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng JQ, Lee WC, Klein MA, Cheng GZ, Jhanwar SC, Testa JR. Frequent mutations of NF2 and allelic loss from chromosome band 22q12 in malignant mesothelioma: evidence for a two-hit mechanism of NF2 inactivation. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1999;24:238–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rustgi AK, Xu L, Pinney D, Sterner C, Beauchamp R, Schmidt S, Gusella JF, Ramesh V. Neurofibromatosis 2 gene in human colorectal cancer. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1995;84:24–26. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(95)00059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horiguchi A, Zheng R, Shen R, Nanus DM. Inactivation of the NF2 tumor suppressor protein merlin in DU145 prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 2008;68:975–984. doi: 10.1002/pros.20760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bianchi AB, Hara T, Ramesh V, Gao J, Klein-Szanto AJ, Morin F, Menon AG, Trofatter JA, Gusella JF, Seizinger BR, et al. Mutations in transcript isoforms of the neurofibromatosis 2 gene in multiple human tumour types. Nat Genet. 1994;6:185–192. doi: 10.1038/ng0294-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rouleau GA, Merel P, Lutchman M, Sanson M, Zucman J, Marineau C, Hoang-Xuan K, Demczuk S, Desmaze C, Plougastel B, et al. Alteration in a new gene encoding a putative membrane-organizing protein causes neuro-fibromatosis type 2. Nature. 1993;363:515–521. doi: 10.1038/363515a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trofatter JA, MacCollin MM, Rutter JL, Murrell JR, Duyao MP, Parry DM, Eldridge R, Kley N, Menon AG, Pulaski K, et al. A novel moesin-, ezrin-, radixin-like gene is a candidate for the neurofibromatosis 2 tumor suppressor. Cell. 1993;75:826. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90501-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bretscher A, Chambers D, Nguyen R, Reczek D. ERM-Merlin and EBP50 protein families in plasma membrane organization and function. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2000;16:113–143. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McClatchey AI, Saotome I, Ramesh V, Gusella JF, Jacks T. The Nf2 tumor suppressor gene product is essential for extraembryonic development immediately prior to gastrulation. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1253–1265. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.10.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giovannini M, Robanus-Maandag E, van der Valk M, Niwa-Kawakita M, Abramowski V, Goutebroze L, Woodruff JM, Berns A, Thomas G. Conditional biallelic Nf2 mutation in the mouse promotes manifestations of human neurofibromatosis type 2. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1617–1630. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McClatchey AI, Saotome I, Mercer K, Crowley D, Gusella JF, Bronson RT, Jacks T. Mice heterozygous for a mutation at the Nf2 tumor suppressor locus develop a range of highly metastatic tumors. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1121–1133. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.8.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tikoo A, Varga M, Ramesh V, Gusella J, Maruta H. An anti-Ras function of neurofibromatosis type 2 gene product (NF2/Merlin) The Journal of biological chemistry. 1994;269:23387–23390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrison H, Sperka T, Manent J, Giovannini M, Ponta H, Herrlich P. Merlin/neurofibromatosis type 2 suppresses growth by inhibiting the activation of Ras and Rac. Cancer research. 2007;67:520–527. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryu CH, Kim SW, Lee KH, Lee JY, Kim H, Lee WK, Choi BH, Lim Y, Kim YH, Hwang TK, Jun TY, Rha HK. The merlin tumor suppressor interacts with Ral guanine nucleotide dissociation stimulator and inhibits its activity. Oncogene. 2005;24:5355–5364. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kissil JL, Wilker EW, Johnson KC, Eckman MS, Yaffe MB, Jacks T. Merlin, the product of the Nf2 tumor suppressor gene, is an inhibitor of the p21-activated kinase, Pak1. Mol Cell. 2003;12:841–849. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00382-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirokawa Y, Tikoo A, Huynh J, Utermark T, Hanemann CO, Giovannini M, Xiao GH, Testa JR, Wood J, Maruta H. A clue to the therapy of neurofibromatosis type 2: NF2/merlin is a PAK1 inhibitor. Cancer J. 2004;10:20–26. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200401000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaw RJ, Paez JG, Curto M, Yaktine A, Pruitt WM, Saotome I, O’Bryan JP, Gupta V, Ratner N, Der CJ, Jacks T, McClatchey AI. The Nf2 tumor suppressor, merlin, functions in Rac-dependent signaling. Dev Cell. 2001;1:63–72. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yi C, Troutman S, Fera D, Stemmer-Rachamimov A, Avila JL, Christian N, Persson NL, Shimono A, Speicher DW, Marmorstein R, Holmgren L, Kissil JL. A tight junction-associated Merlin-angiomotin complex mediates Merlin’s regulation of mitogenic signaling and tumor suppressive functions. Cancer cell. 2011;19:527–540. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sherman L, Xu HM, Geist RT, Saporito-Irwin S, Howells N, Ponta H, Herrlich P, Gutmann DH. Interdomain binding mediates tumor growth suppression by the NF2 gene product. Oncogene. 1997;15:2505–2509. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morrison H, Sherman LS, Legg J, Banine F, Isacke C, Haipek CA, Gutmann DH, Ponta H, Herrlich P. The NF2 tumor suppressor gene product, merlin, mediates contact inhibition of growth through interactions with CD44. Genes Dev. 2001;15:968–980. doi: 10.1101/gad.189601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ikeda K, Saeki Y, Gonzalez-Agosti C, Ramesh V, Chiocca EA. Inhibition of NF2-negative and NF2-positive primary human meningioma cell proliferation by overexpression of merlin due to vector-mediated gene transfer. J Neurosurg. 1999;91:85–92. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.91.1.0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim H, Kwak NJ, Lee JY, Choi BH, Lim Y, Ko YJ, Kim YH, Huh PW, Lee KH, Rha HK, Wang YP. Merlin neutralizes the inhibitory effect of Mdm2 on p53. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:7812–7818. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305526200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiao GH, Gallagher R, Shetler J, Skele K, Altomare DA, Pestell RG, Jhanwar S, Testa JR. The NF2 tumor suppressor gene product, merlin, inhibits cell proliferation and cell cycle progression by repressing cyclin D1 expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:2384–2394. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.6.2384-2394.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamaratoglu F, Willecke M, Kango-Singh M, Nolo R, Hyun E, Tao C, Jafar-Nejad H, Halder G. The tumour-suppressor genes NF2/Merlin and Expanded act through Hippo signalling to regulate cell proliferation and apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:27–36. doi: 10.1038/ncb1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bai Y, Liu YJ, Wang H, Xu Y, Stamenkovic I, Yu Q. Inhibition of the hyaluronan-CD44 interaction by merlin contributes to the tumor-suppressor activity of merlin. Oncogene. 2007;26:836–850. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li W, Giancotti FG. Merlin’s tumor suppression linked to inhibition of the E3 ubiquitin ligase CRL4 (DCAF1) Cell Cycle. 2010;9:4433–4436. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.22.13838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cooper J, Li W, You L, Schiavon G, Pepe-Caprio A, Zhou L, Ishii R, Giovannini M, Hanemann CO, Long SB, Erdjument-Bromage H, Zhou P, Tempst P, Giancotti FG. Merlin/NF2 functions upstream of the nuclear E3 ubiquitin ligase CRL4DCAF1 to suppress oncogenic gene expression. Science signaling. 2011;4:pt6. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Curto M, Cole BK, Lallemand D, Liu CH, McClatchey AI. Contact-dependent inhibition of EGFR signaling by Nf2/Merlin. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:893–903. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200703010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cole BK, Curto M, Chan AW, McClatchey AI. Localization to the cortical cytoskeleton is necessary for Nf2/merlin-dependent epidermal growth factor receptor silencing. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:1274–1284. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01139-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Plotkin SR, Halpin C, McKenna MJ, Loeffler JS, Batchelor TT, Barker FG., 2nd Erlotinib for progressive vestibular schwannoma in neurofibromatosis 2 patients. Otol Neurotol. 2010;31:1135–1143. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181eb328a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.James MF, Han S, Polizzano C, Plotkin SR, Manning BD, Stemmer-Rachamimov AO, Gusella JF, Ramesh V. NF2/merlin is a novel negative regulator of mTOR complex 1, and activation of mTORC1 is associated with meningioma and schwannoma growth. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:4250–4261. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01581-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neff BA, Welling DB, Akhmametyeva E, Chang LS. The molecular biology of vestibular schwannomas: dissecting the pathogenic process at the molecular level. Otol Neurotol. 2006;27:197–208. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000180484.24242.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sughrue ME, Yeung AH, Rutkowski MJ, Cheung SW, Parsa AT. Molecular biology of familial and sporadic vestibular schwannomas: implications for novel therapeutics. J Neurosurg. 2011;114:359–366. doi: 10.3171/2009.10.JNS091135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshiura K, Kanai Y, Ochiai A, Shimoyama Y, Sugimura T, Hirohashi S. Silencing of the E-cadherin invasion-suppressor gene by CpG methylation in human carcinomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7416–7419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Merlo A, Herman JG, Mao L, Lee DJ, Gabrielson E, Burger PC, Baylin SB, Sidransky D. 5’ CpG island methylation is associated with transcriptional silencing of the tumour suppressor p16/CDKN2/MTS1 in human cancers. Nat Med. 1995;1:686–692. doi: 10.1038/nm0795-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herman JG, Latif F, Weng Y, Lerman MI, Zbar B, Liu S, Samid D, Duan DS, Gnarra JR, Linehan WM, et al. Silencing of the VHL tumor-suppressor gene by DNA methylation in renal carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:9700–9704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kino T, Takeshima H, Nakao M, Nishi T, Yamamoto K, Kimura T, Saito Y, Kochi M, Kuratsu J, Saya H, Ushio Y. Identification of the cis-acting region in the NF2 gene promoter as a potential target for mutation and methylation-dependent silencing in schwannoma. Genes Cells. 2001;6:441–454. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gonzalez-Gomez P, Bello MJ, Alonso ME, Lomas J, Arjona D, Campos JM, Vaquero J, Isla A, Lassaletta L, Gutierrez M, Sarasa JL, Rey JA. CpG island methylation in sporadic and neurofibromatis type 2-associated schwannomas. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2003;9:5601–5606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kullar PJ, Pearson DM, Malley DS, Collins VP, Ichimura K. CpG island hypermethylation of the neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) gene is rare in sporadic vestibular schwannomas. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2010;36:505–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2010.01090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Tilborg AA, Morolli B, Giphart-Gassler M, de Vries A, van Geenen DA, Lurkin I, Kros JM, Zwarthoff EC. Lack of genetic and epigenetic changes in meningiomas without NF2 loss. J Pathol. 2006;208:564–573. doi: 10.1002/path.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hansson CM, Buckley PG, Grigelioniene G, Piotrowski A, Hellstrom AR, Mantripragada K, Jarbo C, Mathiesen T, Dumanski JP. Comprehensive genetic and epigenetic analysis of sporadic meningioma for macro-mutations on 22q and micro-mutations within the NF2 locus. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alonso ME, Bello MJ, Gonzalez-Gomez P, Arjona D, de Campos JM, Gutierrez M, Rey JA. Aberrant CpG island methylation of multiple genes in ependymal tumors. J Neurooncol. 2004;67:159–165. doi: 10.1023/b:neon.0000021862.41799.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vilborg A, Glahder JA, Wilhelm MT, Bersani C, Corcoran M, Mahmoudi S, Rosenstierne M, Grander D, Farnebo M, Norrild B, Wiman KG. The p53 target Wig-1 regulates p53 mRNA stability through an AU-rich element. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:15756–15761. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900862106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scoumanne A, Cho SJ, Zhang J, Chen X. The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 is regulated by RNA-binding protein PCBP4 via mRNA stability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:213–224. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hoang-Xuan K, Merel P, Vega F, Hugot JP, Cornu P, Delattre JY, Poisson M, Thomas G, Delattre O. Analysis of the NF2 tumor-suppressor gene and of chromosome 22 deletions in gliomas. Int J Cancer. 1995;60:478–481. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910600409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jacoby LB, MacCollin M, Parry DM, Kluwe L, Lynch J, Jones D, Gusella JF. Allelic expression of the NF2 gene in neurofibromatosis 2 and schwannomatosis. Neurogenetics. 1999;2:101–108. doi: 10.1007/s100480050060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wellenreuther R, Waha A, Vogel Y, Lenartz D, Schramm J, Wiestler OD, von Deimling A. Quantitative analysis of neurofibromatosis type 2 gene transcripts in meningiomas supports the concept of distinct molecular variants. Lab Invest. 1997;77:601–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Deguen B, Goutebroze L, Giovannini M, Boisson C, van der Neut R, Jaurand MC, Thomas G. Heterogeneity of mesothelioma cell lines as defined by altered genomic structure and expression of the NF2 gene. Int J Cancer. 1998;77:554–560. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980812)77:4<554::aid-ijc14>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kanai Y, Tsuda H, Oda T, Sakamoto M, Hirohashi S. Analysis of the neurofibromatosis 2 gene in human breast and hepatocellular carcinomas. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1995;25:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arakawa H, Hayashi N, Nagase H, Ogawa M, Nakamura Y. Alternative splicing of the NF2 gene and its mutation analysis of breast and colorectal cancers. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:565–568. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.4.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yaegashi S, Sachse R, Ohuchi N, Mori S, Sekiya T. Low incidence of a nucleotide sequence alteration of the neurofibromatosis 2 gene in human breast cancers. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1995;86:929–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1995.tb03003.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Morrow KA, Das S, Metge BJ, Ye K, Mulekar MS, Tucker JA, Samant RS, Shevde LA. Loss of Tumor Suppressor Merlin in Advanced Breast Cancer Is due to Post-translational Regulation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:40376–40385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.250035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arpin M, Algrain M, Louvard D. Membrane-actin microfilament connections: an increasing diversity of players related to band 4.1. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994;6:136–141. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90127-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Algrain M, Turunen O, Vaheri A, Louvard D, Arpin M. Ezrin contains cytoskeleton and membrane binding domains accounting for its proposed role as a membrane-cytoskeletal linker. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:129–139. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.1.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Turunen O, Wahlstrom T, Vaheri A. Ezrin has a COOH-terminal actin-binding site that is conserved in the ezrin protein family. J Cell Biol. 1994;126:1445–1453. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.6.1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shimizu T, Seto A, Maita N, Hamada K, Tsukita S, Hakoshima T. Structural basis for neurofibromatosis type 2. Crystal structure of the merlin FERM domain. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:10332–10336. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109979200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gronholm M, Sainio M, Zhao F, Heiska L, Vaheri A, Carpen O. Homotypic and heterotypic interaction of the neurofibromatosis 2 tumor suppressor protein merlin and the ERM protein ezrin. J Cell Sci. 1999;112(Pt 6):895–904. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.6.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pearson MA, Reczek D, Bretscher A, Karplus PA. Structure of the ERM protein moesin reveals the FERM domain fold masked by an extended actin binding tail domain. Cell. 2000;101:259–270. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80836-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yogesha SD, Sharff AJ, Giovannini M, Bricogne G, Izard T. Unfurling of the band 4.1, ezrin, radixin, moesin (FERM) domain of the merlin tumor suppressor. Protein Sci. 2011;20:2113–2120. doi: 10.1002/pro.751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jin H, Sperka T, Herrlich P, Morrison H. Tumorigenic transformation by CPI-17 through inhibition of a merlin phosphatase. Nature. 2006;442:576–579. doi: 10.1038/nature04856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thurneysen C, Opitz I, Kurtz S, Weder W, Stahel RA, Felley-Bosco E. Functional inactivation of NF2/merlin in human mesothelioma. Lung Cancer. 2009;64:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kissil JL, Johnson KC, Eckman MS, Jacks T. Merlin phosphorylation by p21-activated kinase 2 and effects of phosphorylation on merlin localization. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:10394–10399. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200083200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xiao GH, Beeser A, Chernoff J, Testa JR. p21-activated kinase links Rac/Cdc42 signaling to merlin. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:883–886. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100553200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rong R, Surace EI, Haipek CA, Gutmann DH, Ye K. Serine 518 phosphorylation modulates merlin intramolecular association and binding to critical effectors important for NF2 growth suppression. Oncogene. 2004;23:8447–8454. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Thaxton C, Lopera J, Bott M, Fernandez-Valle C. Neuregulin and laminin stimulate phosphorylation of the NF2 tumor suppressor in Schwann cells by distinct protein kinase A and p21-activated kinase-dependent pathways. Oncogene. 2008;27:2705–2715. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gutmann DH, Geist RT, Xu H, Kim JS, Saporito-Irwin S. Defects in neurofibromatosis 2 protein function can arise at multiple levels. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:335–345. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.3.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tang X, Jang SW, Wang X, Liu Z, Bahr SM, Sun SY, Brat D, Gutmann DH, Ye K. Akt phosphorylation regulates the tumour-suppressor merlin through ubiquitination and degradation. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1199–1207. doi: 10.1038/ncb1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Laulajainen M, Muranen T, Nyman TA, Carpen O, Gronholm M. Multistep phosphorylation by oncogenic kinases enhances the degradation of the NF2 tumor suppressor merlin. Neoplasia. 2011;13:643–652. doi: 10.1593/neo.11356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shevde LA, Das S, Clark DW, Samant RS. Osteopontin: an effector and an effect of tumor metastasis. Curr Mol Med. 2010;10:71–81. doi: 10.2174/156652410791065381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shevde LA, Samant RS, Paik JC, Metge BJ, Chambers AF, Casey G, Frost AR, Welch DR. Osteopontin knockdown suppresses tumorigenicity of human metastatic breast carcinoma, MDA-MB-435. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2006;23:123–133. doi: 10.1007/s10585-006-9013-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rodrigues LR, Teixeira JA, Schmitt FL, Paulsson M, Lindmark-Mansson H. The role of osteopontin in tumor progression and metastasis in breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:1087–1097. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rudland PS, Platt-Higgins A, El-Tanani M, De Silva Rudland S, Barraclough R, Winstanley JH, Howitt R, West CR. Prognostic significance of the metastasis-associated protein osteopontin in human breast cancer. Cancer research. 2002;62:3417–3427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kim YW, Park YK, Lee J, Ko SW, Yang MH. Expression of osteopontin and osteonectin in breast cancer. J Korean Med Sci. 1998;13:652–657. doi: 10.3346/jkms.1998.13.6.652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tuck AB, O’Malley FP, Singhal H, Harris JF, Tonkin KS, Kerkvliet N, Saad Z, Doig GS, Chambers AF. Osteopontin expression in a group of lymph node negative breast cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 1998;79:502–508. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19981023)79:5<502::aid-ijc10>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lund SA, Giachelli CM, Scatena M. The role of osteopontin in inflammatory processes. J Cell Commun Signal. 2009;3:311–322. doi: 10.1007/s12079-009-0068-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kitagawa K, Kotake Y, Kitagawa M. Ubiquitin-mediated control of oncogene and tumor suppressor gene products. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:1374–1381. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01196.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hu R, Peng G, Dai H, Breuer EK, Stemke-Hale K, Li K, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Mills GB, Lin SY. ZNF668 functions as a tumor suppressor by regulating p53 stability and function in breast cancer. Cancer research. 2011;71:6524–6534. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rho SB, Lee JH, Park MS, Byun HJ, Kang S, Seo SS, Kim JY, Park SY. Anti-apoptotic protein TCTP controls the stability of the tumor suppressor p53. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ho KC, Zhou Z, She YM, Chun A, Cyr TD, Yang X. Itch E3 ubiquitin ligase regulates large tumor suppressor 1 stability [corrected] Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:4870–4875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101273108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hennessy BT, Smith DL, Ram PT, Lu Y, Mills GB. Exploiting the PI3K/AKT pathway for cancer drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:988–1004. doi: 10.1038/nrd1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Brugge J, Hung MC, Mills GB. A new mutational AKTivation in the PI3K pathway. Cancer cell. 2007;12:104–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Stemke-Hale K, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Lluch A, Neve RM, Kuo WL, Davies M, Carey M, Hu Z, Guan Y, Sahin A, Symmans WF, Pusztai L, Nolden LK, Horlings H, Berns K, Hung MC, van de Vijver MJ, Valero V, Gray JW, Bernards R, Mills GB, Hennessy BT. An integrative genomic and proteomic analysis of PIK3CA, PTEN, and AKT mutations in breast cancer. Cancer research. 2008;68:6084–6091. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yim EK, Peng G, Dai H, Hu R, Li K, Lu Y, Mills GB, Meric-Bernstam F, Hennessy BT, Craven RJ, Lin SY. Rak functions as a tumor suppressor by regulating PTEN protein stability and function. Cancer cell. 2009;15:304–314. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Okahara F, Ikawa H, Kanaho Y, Maehama T. Regulation of PTEN phosphorylation and stability by a tumor suppressor candidate protein. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:45300–45303. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400377200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Torres J, Pulido R. The tumor suppressor PTEN is phosphorylated by the protein kinase CK2 at its C terminus. Implications for PTEN stability to proteasome-mediated degradation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:993–998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009134200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Aghajanian C, Soignet S, Dizon DS, Pien CS, Adams J, Elliott PJ, Sabbatini P, Miller V, Hensley ML, Pezzulli S, Canales C, Daud A, Spriggs DR. A phase I trial of the novel proteasome inhibitor PS341 in advanced solid tumor malignancies. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2002;8:2505–2511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Blaney SM, Bernstein M, Neville K, Ginsberg J, Kitchen B, Horton T, Berg SL, Krailo M, Adamson PC. Phase I study of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in pediatric patients with refractory solid tumors: a Children’s Oncology Group study (ADVL0015) J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4804–4809. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Orlowski RZ, Stinchcombe TE, Mitchell BS, Shea TC, Baldwin AS, Stahl S, Adams J, Esseltine DL, Elliott PJ, Pien CS, Guerciolini R, Anderson JK, Depcik-Smith ND, Bhagat R, Lehman MJ, Novick SC, O’Connor OA, Soignet SL. Phase I trial of the proteasome inhibitor PS-341 in patients with refractory hematologic malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4420–4427. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.01.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Richardson PG, Sonneveld P, Schuster MW, Irwin D, Stadtmauer EA, Facon T, Harousseau JL, Ben-Yehuda D, Lonial S, Goldschmidt H, Reece D, San-Miguel JF, Blade J, Boccadoro M, Cavenagh J, Dalton WS, Boral AL, Esseltine DL, Porter JB, Schenkein D, Anderson KC. Bortezomib or high-dose dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2487–2498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Richardson PG, Sonneveld P, Schuster M, Irwin D, Stadtmauer E, Facon T, Harousseau JL, Ben-Yehuda D, Lonial S, Goldschmidt H, Reece D, Miguel JS, Blade J, Boccadoro M, Cavenagh J, Alsina M, Rajkumar SV, Lacy M, Jakubowiak A, Dalton W, Boral A, Esseltine DL, Schenkein D, Anderson KC. Extended follow-up of a phase 3 trial in relapsed multiple myeloma: final time-to-event results of the APEX trial. Blood. 2007;110:3557–3560. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-036947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Messersmith WA, Baker SD, Lassiter L, Sullivan RA, Dinh K, Almuete VI, Wright JJ, Donehower RC, Carducci MA, Armstrong DK. Phase I trial of bortezomib in combination with docetaxel in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2006;12:1270–1275. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Orlowski RZ, Voorhees PM, Garcia RA, Hall MD, Kudrik FJ, Allred T, Johri AR, Jones PE, Ivanova A, Van Deventer HW, Gabriel DA, Shea TC, Mitchell BS, Adams J, Esseltine DL, Trehu EG, Green M, Lehman MJ, Natoli S, Collins JM, Lindley CM, Dees EC. Phase 1 trial of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in patients with advanced hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2005;105:3058–3065. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Aghajanian C, Dizon DS, Sabbatini P, Raizer JJ, Dupont J, Spriggs DR. Phase I trial of bortezomib and carboplatin in recurrent ovarian or primary peritoneal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5943–5949. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.16.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Irvin WJ, Jr, Orlowski RZ, Chiu WK, Carey LA, Collichio FA, Bernard PS, Stijleman IJ, Perou C, Ivanova A, Dees EC. Phase II study of bortezomib and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2010;10:465–470. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2010.n.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Trinh XB, Sas L, Van Laere SJ, Prove A, Deleu I, Rasschaert M, Van de Velde H, Vinken P, Vermeulen PB, Van Dam PA, Wojtasik A, De Mesmaeker P, Tjalma WA, Dirix LY. A phase II study of the combination of endocrine treatment and bortezomib. Oncol Rep. 2012;27:657–663. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ammoun S, Flaiz C, Ristic N, Schuldt J, Hanemann CO. Dissecting and targeting the growth factor-dependent and growth factor-independent extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway in human schwannoma. Cancer research. 2008;68:5236–5245. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hilton DA, Ristic N, Hanemann CO. Activation of ERK, AKT and JNK signalling pathways in human schwannomas in situ. Histopathology. 2009;55:744–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Garrett CR, Coppola D, Wenham RM, Cubitt CL, Neuger AM, Frost TJ, Lush RM, Sullivan DM, Cheng JQ, Sebti SM. Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of triciribine phosphate monohydrate, a small-molecule inhibitor of AKT phosphorylation, in adult subjects with solid tumors containing activated AKT. Investigational new drugs. 2011;29:1381–1389. doi: 10.1007/s10637-010-9479-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yang L, Dan HC, Sun M, Liu Q, Sun XM, Feldman RI, Hamilton AD, Polokoff M, Nicosia SV, Herlyn M, Sebti SM, Cheng JQ. Akt/protein kinase B signaling inhibitor-2, a selective small molecule inhibitor of Akt signaling with antitumor activity in cancer cells overexpressing Akt. Cancer research. 2004;64:4394–4399. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hennessy BT, Lu Y, Poradosu E, Yu Q, Yu S, Hall H, Carey MS, Ravoori M, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Birch R, Henderson IC, Kundra V, Mills GB. Pharmacodynamic markers of perifosine efficacy. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2007;13:7421–7431. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]