Abstract

A growing body of evidence suggests that mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with oxidative stress and impaired differentiation and invasion of trophoblasts, both of which have been related to preeclampsia pathogenesis. However, studies that examined circulating mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) copy number in relation to preeclampsia are limited. Therefore, we examined association of maternal whole blood mtDNA copy number (a novel biomarker of systemic mitochondrial dysfunction) with the odds of preeclampsia. This case-control study was comprised of 144 preeclampsia cases and 407 normotensive controls. Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used to assess the relative copy number of mtDNA in maternal whole blood samples collected at delivery. Logistic regression procedures were used to estimate adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Median mtDNA copy number was significantly higher among preeclamptic women compared with controls (271.5 vs. 239.3, Mann-Whitney U test p-value <0.001). There was evidence of a linear trend in higher odds of preeclampsia with increasing quartiles of mtDNA copy number (P for trend=0.03) after controlling for confounders. The adjusted ORs for the successive quartiles of mtDNA copy number, compared with the referent (first quartile) were 1.30 (95%CI 0.66-2.56), 1.93 (95%CI 1.02-3.67) and 1.86 (95%CI 1.00-3.48). Our findings suggest that maternal mitochondrial dysfunction may contribute to the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. However, replication in prospective studies is needed to further investigate this relationship.

Keywords: Mitochondria, DNA, mitochondrial DNA, preeclampsia, pregnancy

Introduction

Mitochondria are semiautomonous cytoplasmic organelles of the eukaryotic system that exert essential functions in energy metabolism, free radical production, calcium homeostasis and apoptosis [1-3]. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) abundance is positively correlated with the number and size of mitochondria [4]; and it is modulated by endogenous and exogenous factors such as hypoxemia and steroid hormone exposures [5-7]. Additionally, recent toxicogenomic studies have shown that mtDNA abundance is altered in relation to low-dose benzene [8] and tobacco smoke [9]. Unlike nuclear DNA (nDNA), mtDNA are not protected by histones [10]. Hence, they are particularly susceptible to oxidative stress-induced damage. Cells exposed to oxidative stress have been shown to synthesize more copies of their mtDNA (a marker of mitochondrial abundance) as a means for compensating for damage and to meet the increased respiratory demand for clearing reactive oxygen species (ROS) [4,11]. On the basis of these observations, alterations in mtDNA copy number in various tissues, including whole blood, has emerged as a possible biomarker of mitochondrial dysfunction and risk factor for diverse cardiometabolic, neurodegenerative disorders, as well as multiple cancers [12-14]. Notably, these diverse disorders have oxidative stress as a common pathophysiological mechanism.

Preeclampsia, a vascular disorder that is characterized by hypertension in late pregnancy, progressive renal dysfunction, oxidative stress, systemic inflammation, and diffuse vascular endothelial dysfunction, is a common medical complication of pregnancy [15]. Torbergsen et al [16] are credited with being the first investigative team to observe a high incidence of preeclampsia in a family with diagnosed mitochondrial dysfunction. Almost a decade after this astute clinical observation, Widschwendter and colleagues [17] proposed that defects in mitochondria of trophoblasts may be the initiating step in the pathophysiological cascade of preeclampsia. Based on these observations, and on an emerging literature supporting mitochondrial abundance as a biomarker of oxidative stress and oxidative stress related disorders, including findings from two small studies which suggest that mitochondrial abundance may be associated with placental insufficiency, intrauterine growth restriction and preeclampsia [18,19], we sought to expand the current literature by investigating associations of alterations in mitochondrial copy number in maternal blood with preeclampsia risk. We used clinical information, interview data, and plasma samples from a previously completed case-control study of preeclamptic and normotensive pregnant women [20]. We hypothesized that women with elevated mtDNA copy number, compared with women without this profile, have the higher odds of preeclampsia.

Material and methods

Subjects for this analysis were recruited between April 1998 and January 2000 as part of a case control study designed primarily to study the epidemiology of preeclampsia. Details regarding data collection methods have been previously described [20]. During the study period, women with preeclampsia and normotensive women were recruited from Swedish Medical Center, Seattle, Washington, USA; and Tacoma General Hospital, Tacoma, Washington, USA. Institutional Review Committees at both institutions reviewed and approved the research described herein; and all participants provided written informed consent.

Preeclampsia was diagnosed when both pregnancy-induced hypertension and proteinuria were present, in accordance with the criteria of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [21]. Hypertension was defined as persistent (≥6 hours) blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg. Proteinuria was defined as urine protein concentrations of ≥30 mg/dl on ≥2 random specimens collected ≥4 hours apart. Normotensive women, delivering on the same day of a case, were potential controls. Controls were women with pregnancies uncomplicated by pregnancy-induced hypertension or proteinuria. Women with pre-gestational hypertension and those with multi-fetal pregnancies were excluded from this study. A total of 144 preeclampsia cases and 407 normotensive controls constituted the final study population analyzed for this report.

From structured questionnaires and medical records, we obtained covariate information including maternal age, height, pre-pregnancy weight, last measured weight before delivery, reproductive and medical histories, and medical histories of first-degree family members. Infant weight was also collected from medical records. Pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Maternal non-fasting blood samples, collected in 10 ml Vacutainer tubes during labor and delivery hospital stay, were frozen at -80°C until analysis. DNA was extracted using standard salting-out procedures [22]. Total DNA was used as a template in real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) experiments using the ABI Prism 7000 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The RNase P gene was used as an endogenous control (catalog # 4316844; Applied Biosystems) and Applied Biosystems MT-7S (catalog # Hs02596861_s1) encoding the D-loop of the mitochondrial DNA as the target gene. RNase P is a single-copy nuclear gene and MT-7S is the replication start site for mtDNA. Experiments were performed using 50ng total DNA in a 20μL reaction made up of 10μL 2X TaqMan universal PCR master mix, 1μL primer, and nuclease-free water in a 96-well reaction plate. MT-7S and RNase P reactions were run in duplicate in separate wells. Cycling conditions were: 50°C for 2 min; 95°C for 10 min; followed by 40 cycles of 95°C, 15s and 60°C, 1 min. Data were analyzed using the comparative Ct method, where Ct is defined as the cycle number in which fluorescence first crosses the threshold. ΔCt was found by subtracting the RNaseP Ct values from the MT-7S Ct values. The result was applied to the term 2(-ΔCt). All assays were performed without knowledge of pregnancy outcome.

We examined frequency distributions of maternal socio-demographic, medical characteristics, and medical and reproductive histories according to preeclamptic case-control status. The distribution of whole blood mtDNA copy number was skewed for both cases and controls (p-values for skewness tests for normality were <0.01 for both groups). Therefore, we elected to use the Mann-Whitney U test to compare the difference of median values of mtDNA copy number across preeclampsia and control groups. Furthermore, we used one-way Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric ANOVA to compare median mtDNA copy number values according to selected maternal and perinatal outcomes.

To estimate the relative association between preeclampsia and levels of maternal whole blood mtDNA copy number, we categorized each subject according to quartiles determined by the distribution of mtDNA relative copy number among normotensive controls. We used the lowest quartile as the referent group, and we estimated odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for each of the upper three quartiles. To estimate the odds of preeclampsia in women with extremely high values of maternal blood mtDNA copy number, we created another dichotomous variable to allow for comparison of those women with values in the top 10% ile versus women in the lowest quartile. The lowest quartile was used as the reference value since we saw no evidence of association of preeclampsia with mtDNA in the lowest range of values (i.e., the lowest 10 percentile). In univariate analyses, we used the Mantel extension test [23] to assess the linear component of trend in odds between preeclampsia and mtDNA copy number. In multivariate analyses, using logistic regression procedures, we evaluated linear trends in odds by treating the four quartiles as a continuous variable after assigning a score to each quartile [24]. We also explored the possibility of a nonlinear relation between mtDNA and preeclampsia odds, using generalized additive logistic regression modeling procedures (GAM) [25]. S-Plus (version 6.1, release 2, Insightful Inc. Seattle, WA) was used for these analyses.

To assess confounding, covariates were entered into a logistic regression model one at a time, then the adjusted and unadjusted odds ratios were compared [24]. Final logistic regression models included covariates that altered unadjusted odds ratios by at least 10%, as well as those covariates of a priori interest (e.g., maternal age and parity). We considered the following covariates as possible confounders in this analysis: maternal race/ethnicity, parity, family history of chronic hypertension, leisure time physical activity during pregnancy, smoking during pregnancy, pre-pregnancy body mass index, and gestational age at delivery. All analyses except GAM procedure were performed using STATA 9.0 statistical software. All continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median [interquartile range, IQR]. Reported p-values are two-tailed.

Results

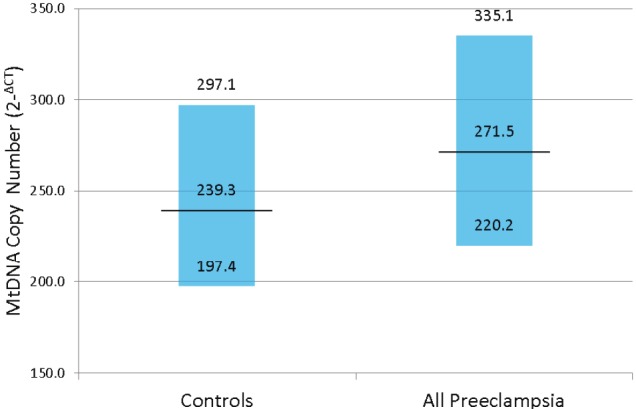

The socio-demographic, medical and reproductive characteristics of preeclampsia cases and normotensive controls are shown in Table 1. Compared with controls, cases tended to be nulliparous, heavier, and to be a cigarette smoker during pregnancy. Cases were also more likely to have a positive family history of chronic hypertension as compared with controls. Overall, the relative median mtDNA copy number was 14.9% higher in preeclampsia cases as compared with controls (Median: 271.5 vs. 239.3 p-value <0.001) (Table 1). The distribution of mtDNA copy number is shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of Preeclampsia (PE) Cases and Normotensive Control Subjects According to Selected Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Preeclampisa Cases (N =144) N % | Control Subjects (N = 407) N % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Age (years)† | 30.1 ± 6.7 | 30.6 ± 5.9 | ||

| <20 | 6 | 4.2 | 21 | 5.1 |

| 20-34 | 100 | 69.4 | 264 | 64.9 |

| ≥35 | 38 | 26.4 | 122 | 30.0 |

| Maternal Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 101 | 70.1 | 288 | 70.8 |

| African American | 15 | 10.4 | 26 | 6.4 |

| Asian | 8 | 5.6 | 33 | 8.1 |

| Other | 20 | 13.9 | 60 | 14.8 |

| Unmarried | 34 | 23.6 | 81 | 19.9 |

| ≤ 12 years Education | 36 | 25.0 | 69 | 17.0 |

| Nulliparous‡ | 100 | 69.4 | 210 | 51.6 |

| Smoked During Pregnancy‡ | 26 | 18.1 | 44 | 10.8 |

| Physical Inactive During Pregnancy | 66 | 45.8 | 151 | 37.1 |

| Family History of Hypertension‡ | 76 | 52.8 | 170 | 41.8 |

| Pre-Pregnancy BMI* † ‡ | 26.8 ± 6.2 | 22.9 ± 4.1 | ||

| <18.5 | 2 | 1.4 | 20 | 4.9 |

| 18.5-24.9 | 68 | 47.2 | 299 | 73.5 |

| 25.0-29.9 | 34 | 23.6 | 63 | 15.5 |

| ≥30.0 | 40 | 27.8 | 25 | 6.1 |

Pre-pregnancy body mass index = BMI = weight (kg)/height2 (m2);

Mean ± standard deviation (SD);

p-value<0.05

Figure 1.

Distribution of Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) Copy Number According to Preeclampsia Case and Normotensive Control Status. Median and Interquartile Range [IQR] are shown.

As shown in Table 2, median mtDNA copy numbers in maternal peripheral blood were not influenced by advanced maternal age, race/ethnicity, parity, exercise or smoking status during pregnancy, and pre-pregnancy BMI. In controls, mtDNA copy number median values were higher in women with family history of chronic hypertension (251.9 vs. 234.9, p-value=0.04). However, we did not observe a statistically significant elevation of mtDNA copy number in women with a family history of chronic hypertension as compared with women without family history of chronic hypertension among preeclampsia cases (280.1 vs. 255.5, p-value=0.28).

Table 2.

Comparison of Median Maternal Whole Blood Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number in Preeclampsia Cases and Controls.

| Characteristics | Preeclampsia (N=144) | Controls (N=407) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| n | Median [IQR] | P-value | n | Median [IQR] | P-value | |

| Overall Mitochondrial DNA | 271.5 [220.2-335.1] | 239.3 [197.4-297.1] | <0.001 | |||

| Advanced Maternal Age | ||||||

| <35 years | 106 | 271.5 (219.8-353.0) | 0.61 | 285 | 238.1 (197.4-308.0) | 0.43 |

| ≥35 years | 38 | 270.0 (226.8-311.8) | 122 | 240.9 (196.3-282.5) | ||

| Maternal Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 101 | 270.1 (221.5-338.9) | 0.59 | 288 | 236.7 (196.5-302.7) | 0.63 |

| Other | 43 | 275.5 (214.5-319.8) | 119 | 246.6 (214.0-285.8) | ||

| Parity | ||||||

| Multiparous | 44 | 263.1 (216.6-295.0) | 0.11 | 197 | 238.1 (197.1-285.8) | 0.37 |

| Primiparous | 100 | 282.0 (221.0-362.7) | 210 | 242.2 (198.7-314.9) | ||

| Leisure Time Exercise During Pregnancy | ||||||

| Yes | 78 | 274.8 (231.3-363.2) | 0.27 | 256 | 238.5 (201.1-294.1) | 0.85 |

| No | 66 | 266.7 (214.5-311.8) | 151 | 246.6 (193.9-301.2) | ||

| Smoked during Pregnancy | ||||||

| No | 118 | 273.4 (215.5-337.5) | 0.73 | 363 | 240.3 (198.7-295.4) | 0.44 |

| Yes | 26 | 259.3 (225.1-332.6) | 44 | 230.9 (184.0-303.6) | ||

| Family History of Hypertension | ||||||

| No | 68 | 255.5 (196.1-345.9) | 0.28 | 237 | 234.9 (196.4-288.2) | 0.04 |

| Yes | 76 | 280.1 (231.6-325.0) | 170 | 251.9 (206.0-303.0) | ||

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||

| <18.5 | 2 | 362.4 (319.8-405.0) | 0.24 | 20 | 212.9 (184.4-257.8) | 0.20 |

| 18.5-24.9 | 68 | 271.5 (230.5-360.3) | 299 | 238.1 (197.3-293.9) | ||

| 25.0-29.9 | 34 | 278.3 (211.4-353.0) | 63 | 258.5 (203.6-308.0) | ||

| ≥30.0 | 40 | 258.7 (196.1-308.6) | 25 | 251.2 (214.2-299.0) | ||

| Preterm Delivery | ||||||

| No | 50 | 253.7 (219.8-362.1) | 0.70 | 388 | 239.0 (197.4-296.8) | 0.61 |

| Yes | 94 | 276.8 (225.1-332.2) | 19 | 249.3 (185.5-299.0) | ||

| Infant Low Birth Weight | ||||||

| No | 56 | 248.6 (212.7-335.8) | 0.24 | 396 | 239.3 (197.2-296.8) | 0.83 |

| Yes | 88 | 280.1 (231.6-335.1) | 11 | 250.5 (220.3-299.4) | ||

| Infant Birthweight | ||||||

| AGA | 120 | 274.8 (219.8-335.1) | 0.74 | 340 | 238.5 (195.4-296.3) | 0.20 |

| LGA | 3 | 311.8 (229.7-367.7) | 55 | 244.5 (209.8-302.4) | ||

| SGA | 21 | 245.5 (220.6-316.3) | 12 | 278.1 (229.5-313.0) | ||

P-values from one-way Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric ANOVA; AGA=average for gestational age; LGA=large for gestational age; SGA=small for gestational age

The ORs of preeclampsia increased across increasing quartiles of maternal whole blood mtDNA copy number (p-value for trend = 0.002 for linear trend) (Table 3). Women in the highest quartile had a 2.2-fold increased odds of preeclampsia than women in the lowest quartile (OR=2.17; 95% CI 1.23-3.83). Evidence of a linear trend of increasing odds of preeclampsia remained after adjusting for maternal race/ethnicity, parity, family history of chronic hypertension, leisure time physical activity during pregnancy, smoking during pregnancy, and prepregnancy body mass index (p-value for trend =0.03 for linear trend in odds across quartiles). The adjusted ORs for the successive higher quartiles of mtDNA copy number, compared with the referent first quartile, were 1.30 (95% CI 0.66-2.56), 1.93 (95% CI 1.02-3.67) and 1.86 (95% CI 1.00-3.48).

Table 3.

Odds Ratios (OR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) for Preeclampsia According to Ccategories of Maternal Whole Blood Mitochondrial DNA Copy Numbers.

| Whole Blood Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number | Preeclampsia (N=144) | Controls (N=407) | Unadjusted OR (95%CI) | Adjusted OR* (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile 1 (<197.3) | 23 (16.0) | 101 (24.8) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Quartile 2 (197.4-239.2) | 28 (19.4) | 102 (25.1) | 1.21 (0.65-2.23) | 1.30 (0.66-2.56) |

| Quartile 3 (239.3-297.1) | 43 (29.9) | 103 (29.9) | 1.83 (1.03-3.26) | 1.93 (1.02-3.67) |

| Quartile 4 (≥297.2) | 50 (34.7) | 101 (24.8) | 2.17 (1.23-3.83) | 1.86 (1.00-3.48) |

| p-value for trend | 0.002 | 0.03 | ||

| Quartile 1 (<197.3) | 23 (16.0) | 101 (24.8) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Decile 90 (≥368.1) | 27 (18.8) | 41 (10.1) | 2.89 (1.49-5.62) | 2.72 (1.26-5.88) |

Adjusted for maternal race/ethnicity, parity, family history of chronic hypertension, leisure time physical activity during pregnancy, smoking during pregnancy, and pre-pregnancy body mass index

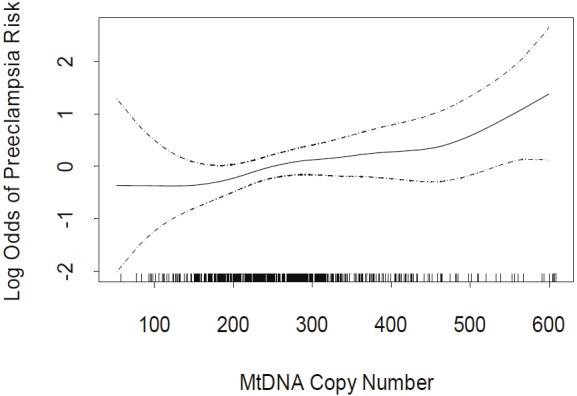

We next modeled the odds of preeclampsia in relation to maternal mtDNA copy number expressed as a continuous variable, using logistic regression procedures based on a generalized additive model (GAM). From these analyses, we noted an approximately linear relationship between preeclampsia risk and maternal mtDNA copy number (Figure 2). On the basis of this observation, we modeled the odds of preeclampsia in relation to maternal mtDNA copy number as a continuous variable. The results (Figure 2) indicate increasing odds of preeclampsia with increasing mtDNA copy number. In fully adjusted models, we noted that a 50-unit increase in mtDNA copy number was associated with a 15% increased odds of preeclampsia (OR=1.15; 95% CI 1.04-1.28). We explored the odds of preeclampsia in relation to extremely high values for mtDNA copy number. For this analysis, we defined extremely high mtDNA copy number as values in the top decile of the mtDNA distribution among normotensive controls (mtDNA copy number ≥ 368.1). Individuals in the lowest quartile (mtDNA copy number < 197.3) were defined as the referent group. In this subgroup analysis, after adjusting for confounders, extremely high mtDNA copy number was associated with a 2.7-fold increased odds of preeclampsia (OR=2.72; 95% CI 1.26-5.88).

Figure 2.

Relation between maternal whole blood mtDNA copy number and the relative odds of preeclampsia (solid line), with 95% CI (dotted lines). Vertical bars along the mtDNA copy number axis indicate distribution of study subjects.

Discussion

Mitochondria are at the crossroads of several crucial activities including ATP generation via oxidative phosphorylation; the biosynthesis of heme, pyrimidines and steroids, calcium and iron homeostasis, and programmed cell death [26,27]. By releasing several proteins that incite programmed cell death, mitochondria are thought to act as “executioners” in apoptosis [28]. Mitochondrial defects, once known to cause only rare severe metabolic and neurological diseases, are now believed to contribute to a wide range of disorders, including common disorders such as hypertension, diabetes, cancers, and neurodegenerative disorders [12-14]. A contribution of mitochondrial dysfunction to the pathogenesis of preeclampsia has been proposed by Torbergsen et al [16] and Widschwendter and et al [17], the latter postulating that defects in trophoblastic mitochondria may be the initiating step in the pathophysiological cascade of preeclampsia.

In the present study, we examined the association of maternal whole blood mtDNA copy number with the odds of preeclampsia. We found that the odds of preeclampsia were positively associated with maternal blood mtDNA copy number. Our results suggest that elevated peripheral blood mtDNA copy number-a novel biomarker of systemic mitochondrial dysfunction [29,30] may be a risk marker for preeclampsia, a common medical complication of pregnancy that is characterized by oxidative stress. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate preeclampsia risk in relation to maternal blood mtDNA copy number.

Mechanisms through which altered mtDNA copy number play a role in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia and other disorders are unclear. However several plausible mechanisms have been postulated. For example, it has been shown that alterations in the mitochondrial genome (e.g., deletions in the control regions of the circular genome) can alter mitochondrial gene expression and lead to a deficiency in oxidative phosphorylation and enhance generation of ATP by glycolysis [31]. Additionally, oxidative stress, known to be an important pathogenesis pathway implicated in preeclampsia [32], may contribute to alterations in mitochondrial function and increased mtDNA copy numbers through several mechanisms, it is plausible that higher levels of systematic reactive oxygen species (ROS) may damage or disrupt cellular structural elements, including the lipid membranes of mitochondria [33]. ROS may also affect mitochondrial function by damaging DNA and impairing election chain transport; and a compensatory response to this cellular stress may lead to increase in mtDNA copy number [4,31]. This thesis is underscored by experimental animal studies documenting increased mitochondrial damage and mtDNA copy numbers with increasing exposure to pro-oxidants [33]. Taken together, these studies suggest that observed that association of increased mtDNA copy number with preeclampsia is biologically plausible.

Several methodological caveats should be considered when interpreting the results of our study. Our study was retrospective, so we cannot determine whether higher mtDNA copy numbers preceded preeclampsia or whether differences can be attributed to preeclampsia-related alterations in maternal oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. We [32-35] and others [36] have previously reported that biomarkers of maternal oxidative stress precede the clinical diagnosis of preeclampsia. Hence it is stands to reason that alterations in mtDNA abundance may also precede the diagnosis of the disorder. Nevertheless, prospective cohort studies with serial longitudinal follow-up are needed to further clarify the temporal relationship of mtDNA copy number with the incidence of preeclampsia. Differential misclassification of maternal mtDNA copy number is unlikely, as all laboratory analyses were conducted without knowledge of participants’ pregnancy outcome. Although we controlled for multiple confounding factors, it cannot be concluded with certainty that the odds ratios reported are unaffected by residual confounding.

In summary, our results suggest that mtDNA copy number in maternal blood is associated with preeclampsia risk in a dose-dependent manner. Future research should include assessment of placental mtDNA copy number, direct measure of placental and maternal whole body mitochondrial function, and assays that elucidate the potential modifiers of this association. Analyses that interrogate the influence of variation in the mitochondrial genome are also warranted.

References

- 1.Crimi M, Rigolio R. The mitochondrial genome, a growing interest inside an organelle. Int J Nanomedicine. 2008;3:51–57. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallace DC. Mitochondrial DNA mutations in disease and aging. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2010;51:440–450. doi: 10.1002/em.20586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallace DC. Mitochondria, bioenergetics, and the epigenome in eukaryotic and human evolution. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2009;74:383–393. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2009.74.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee HC, Wei YH. Mitochondrial role in life and death of the cell. J Biomed Sci. 2000;7:2–15. doi: 10.1007/BF02255913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoppeler H, Vogt M, Weibel ER, Flück M. Response of skeletal muscle mitochondria to hypoxia. Exp Physiol. 2003;88:109–119. doi: 10.1113/eph8802513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weitzel JM, Iwen KA, Seitz HJ. Regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis by thyroid hormone. Exp Physiol. 2003;88:121–128. doi: 10.1113/eph8802506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shadel GS. Expression and maintenance of mitochondrial DNA: new insights into human disease pathology. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1445–1456. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.071163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carugno M, Pesatori AC, Dioni L, Hoxha M, Bollati V, Albetti B, Byun HM, Bonzini M, Fustinoni S, Cocco P, Satta G, Zucca M, Merlo DF, Cipolla M, Bertazzi PA, Baccarelli A. Increased mitochondrial DNA copy number in occupations associated with low-dose benzene exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:210–215. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouhours-Nouet N, May-Panloup P, Coutant R, de Casson FB, Descamps P, Douay O, Reynier P, Ritz P, Malthièry Y, Simard G. Maternal smoking is associated with mitochondrial DNA depletion and respiratory chain complex III deficiency in placenta. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288:E171–177. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00260.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Croteau DL, Bohr VA. Repair of oxidative damage to nuclear and mitochondrial DNA in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25409–25412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu J, Sharma LK, Bai Y. Implications of mitochondrial DNA mutations and mitochondrial dysfunction in tumorigenesis. Cell Res. 2009;19:802–815. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiMauro S, Garone C, Naini A. Metabolic myopathies. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2010;12:386–393. doi: 10.1007/s11926-010-0119-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jezek P, Plecitá-Hlavatá L, Smolková K, Rossignol R. Distinctions and similarities of cell bioenergetics and the role of mitochondria in hypoxia, cancer, and embryonic development. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:604–622. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stark R, Roden M. ESCI Award 2006. Mitochondrial function and endocrine diseases. Eur J Clin Invest. 2007;37:236–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2007.01773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uzan J, Carbonnel M, Piconne O, Asmar R, Ayoubi JM. Pre-eclampsia: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2011;7:467–474. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S20181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torbergsen T, Oian P, Mathiesen E, Borud O. Pre-eclampsia--a mitochondrial disease? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1989;68:145–148. doi: 10.3109/00016348909009902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Widschwendter M, Schröcksnadel H, Mörtl MG. Pre-eclampsia: a disorder of placental mitochondria? Mol Med Today. 1998;4:286–291. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(98)01293-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lattuada D, Colleoni F, Martinelli A, Garretto A, Magni R, Radaelli T, Cetin I. Higher mitochondrial DNA content in human IUGR placenta. Placenta. 2008;29:1029–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colleoni F, Lattuada D, Garretto A, Massari M, Mandò C, Somigliana E, Cetin I. Maternal blood mitochondrial DNA content during normal and intrauterine growth restricted (IUGR) pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:365.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sorensen TK, Williams MA, Lee IM, Dashow EE, Thompson ML, Luthy DA. Recreational physical activity during pregnancy and risk of preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2003;41:1273–1280. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000072270.82815.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy: Report of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy. AJOG. 2000;183:S1–S22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;12:1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mantel N. Chi-square tests with one degree of freedom: extensions of Mantel-Haenszel procedure. J Am Stat Assoc. 1963;58:690–700. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Modern Epidemiology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hastie TJ, Tibshirani RJ. Generalized Additive Models. London: Chapman-Hall; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Houten B, Woshner V, Santos JH. Role of mitochondrial DNA in toxic responses to oxidative stress. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scarpulla RC. Nuclear control of respiratory chain expression by nuclear respiratory factors and PGC-1-related coactivator. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1147:321–334. doi: 10.1196/annals.1427.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garrido C, Kroemer G. Life's smile, death's grin: vital functions of apoptosis-executing proteins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16:639–646. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han D, Williams E, Cadenas E. Mitochondrial respiratory chain-dependent generation of superoxide anion and its release into the intermembrane space. Biochem. 2001;353:411–416. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3530411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eliseev RA, Gunter KK, Gunter TE. Bcl-2 prevents abnormal mitochondrial proliferation during etoposide-induced apoptosis. Exp Cell Res. 2003;289:275–281. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00278-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee HC, Wei YH. Mitochondrial biogenesis and mitochondrial DNA maintenance of mammalian cells under oxidative stress. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:822–834. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rudra CB, Qiu C, David RM, Bralley JA, Walsh SW, Williams MA. A prospective study of early-pregnancy plasma malondialdehyde concentration and risk of preeclampsia. Clin Biochem. 2006;39:722–726. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.James AM, Murphy MP. How mitochondrial damage affects cell function. J Biomed Sci. 2002;9:475–487. doi: 10.1159/000064721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qiu C, Phung TT, Vadachkoria S, Muy-Rivera M, Sanchez SE, Williams MA. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein (Oxidized LDL) and the risk of preeclampsia. Physiol Res. 2006;55:491–500. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.930813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanchez SE, Williams MA, Muy-Rivera M, Qiu C, Vadachkoria S, Bazul V. A case-control study of oxidized low density lipoproteins and preeclampsia risk. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2005;21:193–199. doi: 10.1080/09513590500154019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Y, Walsh SW. Increased superoxide generation is associated with decreased superoxide dismutase activity and mRNA expression in placental trophoblast cells in pre-eclampsia. Placenta. 2001;22:206–212. doi: 10.1053/plac.2000.0608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]