Abstract

The Drosophila dribble (dbe) gene encodes a KH domain protein, homologous to yeast KRR1p. Expression of dbe transcripts is ubiquitous during embryogenesis. Overexpressed Dribble protein is localized in the nucleus and in some cell types in a subregion of the nucleolus. Homozygous dbe mutants die at first instar larval stage. Clonal analyses suggest that dbe+ is required for survival of dividing cells. In dbe mutants, a novel rRNA-processing defect is found and accumulation of an abnormal rRNA precursor is detected.

INTRODUCTION

The nucleolus is the site of ribosomal subunit synthesis in eukaryotic nuclei. Here, rRNA is transcribed, matured by a series of nucleolytic cleavages and chemical modifications, and assembled with ribosomal proteins into ribosomal subunits. It has also been implicated in a number of other activities including p53 regulation and posttranscriptional modification of some small RNA molecules (Olson et al., 2000). rRNA maturation and ribosome assembly is a complex series of events, likely to involve the action of many proteins and small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs).

Proteins localized in the nucleolus are therefore good candidates to be involved in ribosome biogenesis. One such protein is yeast KRR1p, which is essential for yeast viability (Gromadka et al., 1996). This contains a KH domain, originally characterized as a likely RNA-binding domain of hnRNP K (Siomi et al., 1993). KRR1p also interacts with the DNA replication protein MCM6 (Uetz et al., 2000). A human homologue, HuRip1, has been reported to interact with HIV-1 Rev protein in a yeast two-hybrid screen (reported in GenBank, accession number U55766). Tagged versions of the protein have been variously reported as being localized in the nucleolus (Burns et al., 1994) or the nuclear rim (Rout et al., 2000). While this paper was under review, a tagged version that appears fully functional was shown to be localized in the nucleolus (Sasaki et al., 2000), and krr1 mutations were shown to affect biogenesis of 18S rRNA and its precursors and of 40S ribosomal subunits (Sasaki et al., 2000).

To further address the function of the KRR1p family of proteins, we describe the identification and characterization of a novel KRR1p-like KH domain protein, Dribble (DBE), in Drosophila. Evidence presented here also suggests a role for it in pre-rRNA processing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila Stocks

Drosophila strains were raised at 25°C on cornmeal yeast agar medium (Roberts, 1998). Genetic markers, balancers, and cytological positions were described by Lindsley and Zimm (1992). The following stocks were used: y w (Sweeney et al., 1995); y1 w; CyO, y+/Sco (Hassan et al., 1998); w; CyO, GFP/Sco (Reichhart and Ferrandon, 1998); y w; +; D3/TM3 (Russell et al., 1996); y1 w; CyO, y+/If; MKRS/TM6, y+; w; CyO/Sp; Dr P{ry+, Δ2–3}99B/TM6C (Robertson et al., 1988); w; +; hsGAL4/TM6B (a kind gift of Dr. Karen Blochlinger); engrailed-GAL4 (A. Brand and K. Yoffe, unpublished materials cited in FlyBase (http://flybase.bio.indiana.edu); l(2)k05428 (dbeP) and l(2)06708 (Török et al., 1993); Df(2L)ast4 (Roberts et al., 1985); f36a; ck P{f+}30B FRT40A/CyO (de Celis et al., 1996); P{hs-neo ry+ FRT}2L-40A (Chou and Perrimon, 1996); hsFLP; CyO/Sp (Chou and Perrimon, 1996).

P-Element Mobilization

Imprecise excision of DNA flanking P-elements was performed essentially as described by O'Kane (1998). From approximately 75,000 progeny, 178 w− excision lines were recovered; 74 were lethal over the original insertion. These were screened for flanking deletions by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers flanking the dbeP P-element insertion site: AroF(R), 5′-CCGGTACCAGAAAT-CGTACTG-3′ (+1426), and JoutF1, 5′-GGTCGAGCAAATCGGTAATAAGC-3′ (−823); primer positions are assigned relative to the first nucleotide of the dbe open reading frame and refer to the 3′-nucleotides. AroF(R) extends toward the 3′-end of dbe, whereas JoutF1 extends toward the 5′-end. PCR conditions were 15 s at 98°C, 30 s at 62°C, 1.5 min at 72°C, 30 s at 95°C for 30 cycles, using single-fly template DNA (Gloor et al., 1993). Five PCR products that differed in size from wild type were purified and sequenced using primers AroF(R) and JoutF1.

Lethal Stage Determination

dbe fly lines were first crossed into a y1 background and then rebalanced over a CyO, y+ balancer (y1 w; CyO, y+/Sco; +). Homozygous larvae were identified by yellow coloration of the mouth hooks (Hassan et al., 1998).

Somatic Recombination and Clonal Analyses

To generate wing clones, w; m/CyO males were crossed to f; ck P{f+}30B FRT40A/CyO females (m represents either dbeD102 or a wild-type precise excision of dbeP obtained from a P-element mobilization screen described above and confirmed by DNA sequencing). Larval progeny were X-irradiated (1000 R; 300 R/min; 100 kV; 15 mA; with a 2-mm aluminum filter). Homozygous mutant clones were identified by the f marker and twin spot clones by ck.

To generate eye clones, dbeP/CyO males were crossed to Canton S w females. Larvae were irradiated with x-rays as before at 24–48 h after egg laying (AEL). Homozygous mutant clones would be w+/w+ (dark red), the wild-type twin spot would be w/w (white), and heterozygous nonrecombinant cells would be marked with w+/w (orange).

Germline clones were induced using the FLP/FRT system (Chou and Perrimon, 1992). Strategies used were modified from those of Schulze and Bellen (1996). The dbeD29 and dbeD102 deletions were first recombined separately onto a chromosome containing P{hs-neo ry+ FRT}2L-40A. First instar larvae (24–48 h AEL) of genotype P{hs-FLP}; m, P{hs-neo ry+ FRT}2L-40A were heat shocked at 37°C for 1 h (m represents dbeD29 or dbeD102 or a dbeP revertant). All Cy+ females were tested for egg-laying activity for several days. Ovaries from females that failed to lay eggs were dissected and examined.

Molecular Techniques

Basic molecular biology techniques were carried out according to those of Sambrook et al. (1989). Genomic DNA was isolated from adult flies using the Puregene DNA isolation kit (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Randomly primed DIG-labeled DNA probes were prepared using the DIG High-Prime kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Lewes, United Kingdom).

Genomic sequences flanking P-element insertions were obtained by plasmid rescue (Wilson et al., 1989). EcoRI and SacII were used for 3′-plasmid rescue. The P insertion site was determined by sequencing a plasmid rescue clone using a P-element–specific primer (P3′: 5′-CAAGCATACGTTAAGTGGATG-3′; Figure 1A), which extends toward the end of the 3′-end of the P-element, with its 3′-nucleotide at position +10,650 of the 10,691-bp PLacW construct.

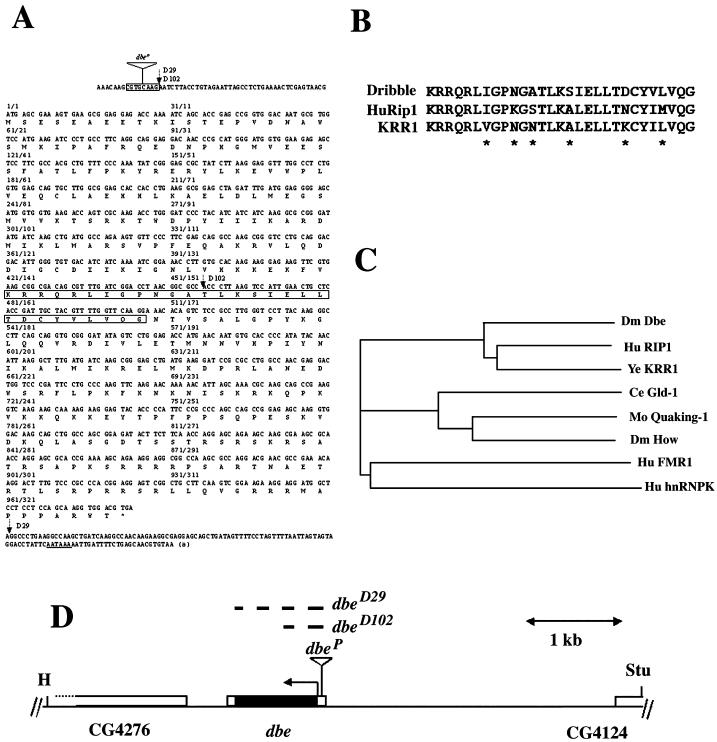

Figure 1.

Structure of the dbe gene. (A) Nucleotide sequence of dbe cDNA and its deduced amino acid sequence. Nucleotide position of the dbe coding region (counted from the first nucleotide of the first ATG) is indicated above the nucleotide sequence and followed by the amino acid position. The inverted triangle represents the P-element insertion site of l(2)k05428, and the 8-bp target site duplication is boxed. Vertical arrows represent the breakpoints in dbe deletion mutants. The KH domain is boxed. The stop codon is designated with an asterisk; the polyA signal is underlined, and the final “a” indicates the position of the polyA tail. (B) Alignment of amino acid sequences of the Drosophila DBE KH domain with the corresponding regions in the human (HuRip1) and yeast (KRR1) proteins. For accession numbers, see C. Asterisks represent variable amino acid residues. (C) A dendrogram illustrating the similarity relationships of different KH domain proteins using the PHYLIP package (J. Felsenstein, University of Washington). The length of the longitudinal lines is proportional to the estimated distance between two sequences. Accession numbers (all GenBank unless otherwise noted): Drosophila DBE, EMBL Z96931; Human Rip1, U55766; KRR1p, NP 009872; HUMAN FMR1, S65791; human hnRNPK, S74678; Caenorhabditis elegans Gld1–1, U20535; Mouse Quaking-1, U44940; Drosophila How, U85651. Dm, Drosophila melanogaster; Hu, human; Ye, Saccharomyces cerevisiae; Ce, Caenorhabditis elegans; Mo, mouse. (D) Genomic organization of dbe and surrounding loci. The StuI/HindIII genomic rescue fragment is shown. The arrow represents the direction of transcription. Empty boxes in the dbe transcript represent 5′- and 3′-UTRs, and the black box represents the coding region. The inverted triangle represents the insertion site of l(2)k05428 (dbeP). Dashed lines represent breakpoints of the dbeD29 and dbeD102 deletions. Stu, StuI; H, HindIII.

A 1.4-kb fragment flanked by XhoI (−11) and KpnI (+1437) sites (Figure 1A; coordinates relative to the first nucleotide of the dbe coding region) was subcloned from lambda genomic clone 8(1) (Schneuwly et al., 1989) into pBluescript (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) to make pBluescript-dbe and sequenced. Two cDNA clones, LD11164 and LD14295 (Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project/HHMI Expressed Sequence Tag (EST) Project, www.fruitfly.org), were sequenced in one strand. The 5′-end of clone LD24634 contained an additional 5′-untranslated region (UTR) sequence of dbe (Figure 1A; Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project/HHMI EST Project, www.fruitfly.org). Phylogenetic analyses were carried out using the PHYLIP package (J. Felsenstein, University of Washington, Seattle, WA). Because of the sequence homology of this open reading frame to a nuclear/cytoplasmic shuttling protein (HuRIP1; see below), we therefore named it “dribble” to illustrate its homology to this protein.

Transgenic Experiments

P-element–mediated germline transformation was performed essentially according to the method of Rubin and Spradling (1982). For heat shock, animals were subjected to 37°C for 30–60 min and a recovery period of 60 min at 25°C before dissection.

A 6.5-kb HindIII-StuI fragment (Figure 1D) with the whole dbe open reading frame was subcloned from lambda genomic clone 8(1) (Schneuwly et al., 1989) into pWhiteRabbit (Martin-Bermudo et al., 1997) to make P{WhiteRabbit-8(1)HindIII/StuI}. For rescue experiments, flies homozygous for dbeD29 and carrying an X-linked insertion of P{WhiteRabbit-8(1)HindIII/StuI} were constructed. A stable stock of genotype y w P{WhiteRabbit-8(1)HindIII/StuI}; dbeD29/CyO, y+ (floating) was obtained from one of the four lines where rescue was observed. To test the genotype of this stock, non-Curly putative dbeD29 homozygous females were outcrossed en masse to wild-type males (Canton S). PCR reactions were performed on 26 single progeny (Gloor et al., 1993) to detect the dbeD29 deletion with primers AroF(R) and JoutF1 (diagnosed by a 1.2-kb band, compared with 2.2 kb in the wild-type allele). All showed the presence of the dbeD29 deletion chromosome, confirming that the parents had been homozygous for dbeD29.

To generate hs-dbe and UAS-dbe constructs, an EcoRI-KpnI fragment from pBluescript-dbe was subcloned into pMartini (kind gift of Dr. S. Findley, University of Washington) to make pMartini-dbe. An EcoRI-NotI fragment containing the 1.4-kb dbe genomic fragment from pMartini-dbe was then ligated into either pCaSpeR-hs (Thummel and Pirrotta, 1991) or pUAST (Brand and Perrimon, 1993) vectors to make pCaSpeR-hs-dbe and pUAST-dbe, respectively.

To generate the UAS-ATG-FLAG-dbe construct, two complementary oligonucleotides (ATG-FLAG-dbeF: 5′-AATTCATGGATTACAAGGACGATGACGATAAGGAT-3′, and ATG-FLAG-dbeR: 5′-CGATCCTTATCGTCATCGTCCTTGTAATCCATG-3′) were annealed to give an EcoRI-ClaI fragment (Afshar et al., 1995), which was ligated to linearized EcoRI-ClaI pMartini-dbe to make pMartini-ATG-FLAG-dbe. This encoded a protein with a predicted N-terminal sequence MDYKDDDDKD-Dribble, which was confirmed by DNA sequencing. A 1.5-kb EcoRI-NotI fragment with the ATG-FLAG-dbe cassette was subcloned from this plasmid into pUAST to make pUAST-ATG-FLAG-dbe.

Generation and Purification of Anti-Dribble Antisera

The 1.4-kb XhoI-KpnI dbe genomic fragment from pMartini-dbe was ligated in-frame into a His-tag expression vector pRSetC (InVitrogen, Inchinnan, United Kingdom). Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3)C41 (Miroux and Walker, 1996) was used for recombinant fusion protein expression according to the supplier's instructions (InVitrogen). The His-Dbe fusion protein was purified using an Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose column (Qiagen, Crawley, United Kingdom) and injected repeatedly into two New Zealand White rabbits numbered 71 and 72 (Regal group, UK). Serum from rabbit 72 was used for all experiments shown here because it contains less cross-immunoreactivity with Drosophila epitopes.

Preabsorption was done by incubating 100 μl of antiserum with pRSetC-transformed BL21(DE3)C41 cell lysate (900 μl) and subsequently with wild-type embryo homogenates (400 μl) at 4°C overnight. Affinity purification of antisera from immunoblots was performed essentially according to the method of Harlow and Lane (1988). The affinity-purified serum was used at a dilution of 1:2000 for immunohistochemistry.

In Situ Hybridization and Immunohistochemistry to Whole Mount Ovaries, Embryos, and Larval Drosophila Tissues

Single-stranded DNA probes labeled with digoxygenin-11-dUTP (Boehringer Mannheim) were prepared by PCR labeling (Chan et al., 1997), using either T7 or SP6 primers. Templates were PCR products containing Drosophila DNA that had been amplified from gel-purified plasmid DNA template. In situ hybridization was performed essentially according to the procedure of Tautz et al. (1992).

Immunohistochemical staining was performed essentially according to the method of Patel (1994). The following primary antibodies were used, with the dilutions indicated: rabbit anti-Dribble polyclonal antisera 71 and 72 at 1:1000 for affinity-purified antibodies; rabbit polyclonal anti-actin (Sigma, Poole, United Kingdom) at 1:200; monoclonal antibody D77 against fibrillarin (Aris and Blobel, 1988) at 1:1000; monoclonal antibody against HIV-1 Rev protein (Repligen, Needham, MA; Meyer and Malim, 1994) at 1.25 μg/ml; monoclonal antibody M5 against the FLAG epitope (Kodak, Rochester, NY; Afshar et al., 1995) at 1:1000. Horseradish peroxidase-linked immunohistochemical staining was detected by the ABC elite kit (Dakopatts, Glostrup, Denmark). Goat–anti-rabbit Cy3 or fluorescein isothiocyanate fluorescent secondary antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:200 (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). Propidium iodide was used at 20 μg/ml to visualize nuclei. Embryo staging was according to the method of Campos-Ortega and Hartenstein (1997).

Western Blotting

Western blotting was performed essentially according to the procedure of Towbin et al. (1979). Preabsorbed serum 72 was used at a dilution of 1:2000 and anti-HIV-1-Rev monoclonal antibody was used at 100 ng/ml. Signals were detected using either nitroblue tetrazolium/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate color detection (Harlow and Lane, 1988) or the ECL chemiluminescence kit (Amersham, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom).

Northern Blotting

Total RNA isolation and Northern blot analysis was performed according to the method of Brogna (1999), except that RNA was not separated from DNA with LiCl2 (this allowed DNA to be used for visual quantitation of gel loading). For optimal RNA separation, formaldehyde was included in the 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid running buffer. Total RNA was purified from either wild-type larvae or mutant first instar larvae of genotype y w; dbeD29/dbeD29, which were selected under a dissecting microscope by the color of their mouth hooks. Probes were amplified by PCR from a genomic DNA template.

RESULTS

Isolation of dbe Genomic and cDNA Clones

Sequence comparisons identified a KRR1-like sequence in the 21DE region of the Drosophila genome, approximately 16 kb to the right of kraken, a gene that encodes a putative hydrolytic enzyme (Chan et al., 1998), and immediately to the left of P-element insertion l(2)k05428. Further homology searching of the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project EST database (www.fruitfly.org) identified EST clot 2705 in this genomic sequence. Sequencing of cDNA clones LD11164 and 14295 from this clot and comparison with the genomic sequence showed that the KRR1-like gene lacked introns, and encoded a predicted protein of 327 amino acid residues with a 5′-UTR of up to 56 bp in clone LD24634 (Figure 1A).

dbe, a Member of a New KH Domain Protein Subfamily

The gene identified by clot 2705 was designated dbe and subsequently as CG4258 by the Drosophila Genome Sequencing Project (http://flybase.bio.indiana.edu). dbe shows homology to human HuRip1 and to yeast KRR1 (Figure 1, B and C). A highly conserved KH domain was found from amino acid residues 141 to 169 (29 amino acids in length), which showed 79% identity to the HuRip1 and KRR1p KH domains (Figure 1B). Although conservation among DBE, HuRip1, and KRR1p continued throughout these proteins, extended similarities to other proteins were confined to the KH domain. Other KH domain proteins showed lower homology to the DBE KH domain, e.g., 56% identity to mouse Quaking KH domain (Ebersole et al., 1996) over 25 residues, and no obvious similarity to DBE outside the KH domain. DBE, HuRip1, and KRR1p therefore define a new KH domain subfamily (Figure 1C).

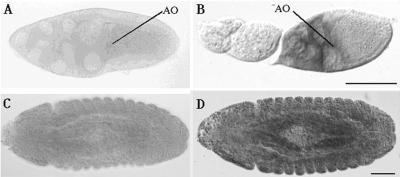

Expression of dbe Transcript during Development

During oogenesis, dbe mRNA expression was detected from stage 10A until the end of oogenesis (Figure 2B). At stage 10A, dbe was expressed in the nurse cells, with some mRNA in the anterior part of the oocyte that may have been transported from the nurse cells (Figure 2B). Nurse cell expression of dbe persisted from stage 10A until stage 14. After the breakdown of nurse cells at the end of oogenesis, dbe was detected in the follicle cells that form the dorsal appendages (Chan, Brogna, and O'Kane, unpublished results). dbe was detected ubiquitously at all stages of embryogenesis examined (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Expression of dbe during oogenesis and embryogenesis. (A) A stage 10A egg chamber hybridized with a dbe sense probe. (B) stage 5–10A egg chambers hybridized with a dbe antisense probe. Scale bar (A and B), 200 μm. (C) A stage 14 embryo hybridized with a dbe sense probe. (D) A stage 14 embryo hybridized with a dbe antisense probe. Scale bar (C and D), 50 μm. AO, anterior end of oocyte.

Subcellular Localization of DBE Protein in Drosophila Tissues

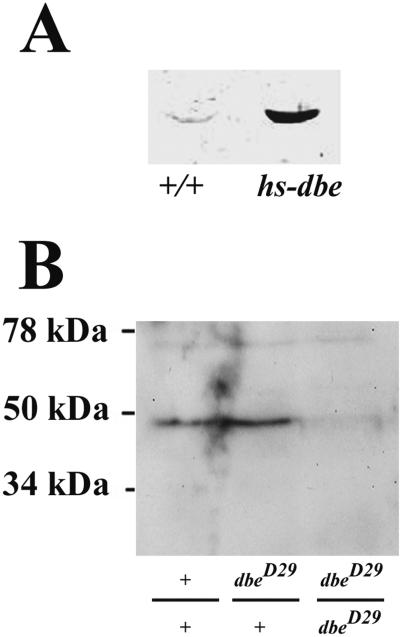

To gain insight into the subcellular localization of DBE protein, polyclonal antibodies against the DBE protein were generated. From the embryo in situ hybridization data (Figure 2), DBE protein was expected to be ubiquitously expressed; however, no signal was detected when preabsorbed anti-DBE antibody was used for immunohistochemistry on embryos (Chan, Brogna, and O'Kane, unpublished results). Western blotting showed that endogenous DBE levels were low compared with those that could be induced in flies that expressed dbe under heat shock control (Figure 3A), and we attribute the failure to detect endogenous DBE by immunohistochemistry to levels of expression that are below the levels detectable in our hands.

Figure 3.

(A) Drosophila DBE protein is recognized by the DBE antiserum 72. +/+, lane loaded with wild-type third instar larvae; hs-dbe, lane loaded with third instar larvae that carried an hs-dbe construct. (B) Expression level of DBE protein is greatly reduced in homozygous dbeD29 first instar larvae. A 46-kDa band was detected in the wild-type (+/+) and heterozygous dbeD29/+ lanes with preabsorbed serum 72, but the intensity of this band is markedly reduced in the homozygous dbeD29/dbeD29 lane.

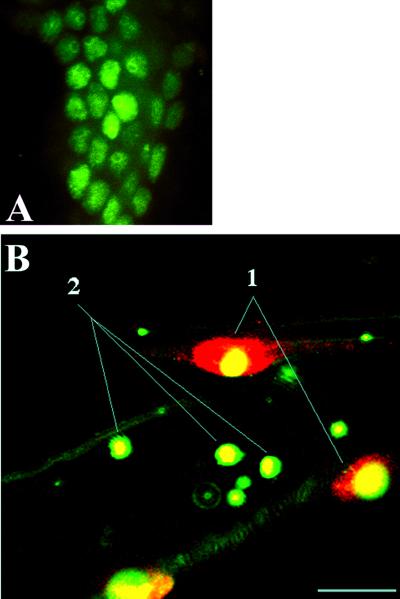

We therefore expressed DBE in flies using an engrailed-GAL4 driver (Brand and Perrimon, 1993); a nuclear engrailed-like pattern of ectopically expressed DBE was obtained in embryonic epidermal cells (Figure 4A). Overexpressed DBE protein was localized predominantly in the nucleoplasm and in most cells was preferentially localized in a perinucleolar ring structure (Figure 4A). A similar pattern was observed in salivary gland cells from heat-shocked hs-dbe transgenic third instar larvae (Chan, Brogna, and O'Kane, unpublished results).

Figure 4.

(A) Ectopically expressed FLAG-tagged DBE fusion protein was detected by anti-FLAG antibody. Embryos were collected from a cross between flies bearing UAS-FLAG-dbe and engrailed-GAL4. A perinucleolar ring structure was observed in a majority of embryonic epithelial cells. (B) Gut cells from a larva bearing hs-dbe. 1, DBE is present throughout both nucleoplasm and nucleolus in cells on the periphery of the gut (possibly visceral muscle); 2, DBE is present only in the center of the fibrillarin-positive part of the nucleolus. Green, fibrillarin; red, DBE; yellow, colocalization. Scale bar, 10 μm.

To determine the subnuclear localization of DBE, double-labeling experiments were performed using DBE antibodies and a nucleolus-specific monoclonal antibody (D77). D77 recognizes fibrillarin (Aris and Blobel, 1988; Zimowska et al., 1997), found in the fibrillar center, which contains rDNA, RNA polymerase I, and associated transcription factors, and in the dense fibrillar component where most rRNA processing occurs (Cerdido and Medina, 1995; Lamond and Earnshaw, 1998). In heat-shocked hs-dbe third instar larvae, localization of DBE varied between different cells. For example, two situations were observed in gut cells (Figure 4B): 1) DBE was detected throughout both nucleoplasm and nucleolus; 2) DBE was detected in the center of the fibrillarin-positive part of the nucleolus, in the fibrillar center, where rRNA transcription occurs.

Isolation of dbe Mutants

Because the subcellular localization of DBE suggested a possible nucleolar function, we wished to study the loss of function phenotype of the dbe gene. Genomic Southern blots using a dbe probe suggested that dbe was a single-copy gene (Chan, Brogna, and O'Kane, unpublished results) and that no closely related paralogs would therefore complicate any subsequent genetic analysis. Line l(2)k05428 contains a single homozygous lethal P insert and is lethal over deletion Df(2L)ast4 (Roberts et al., 1985), which affects the 21D/E region. No obvious dominant effects of this insertion on viability or development could be detected. Comparison of the LD24634 cDNA sequence from clot 2705 with that of a plasmid-rescued clone from line l(2)k05428 revealed that the P-element had inserted in the 5′-UTR of dbe, duplicating a target site between positions −49 and −41 (numbered from the first nucleotide of the predicted protein; Figure 1A). Transposase-mediated excision performed using line l(2)k05428 showed that the homozygous lethality could be reverted to viability, suggesting that the lethality was indeed due to a P insertion; this insertion was therefore designated dbeP. Another P insert line, l(2)k06708 was also found to have an insertion in the 5′-UTR of the dbe transcript. However, this stock was apparently balanced over a P insertion in the nearby Star gene (Chan, Brogna, and O'Kane, unpublished results) and was not investigated further. Because l(2)k05428 is inserted in the 5′-UTR of the dbe transcript, the P-element insertion might not completely knock out dbe. To generate dbe null mutants, an imprecise excision screen of the l(2)k05428 insert was performed. Two lines that carried deletions (dbeD29 and dbeD102) were chosen for further analyses. The 5′-deletion breakpoint in both lines is at the site of dbeP (Figure 1A). In addition, both lines had lost the entire P insert and retained one copy of the target site duplication from the dbeP insertion. Line dbeD29 appears to be a dbe null mutant because the whole open reading frame of dbe is deleted (Figure 1, A and D). This is supported by Western blots that show that the 46-kDa DBE protein is almost absent in dbeD29 homozygous first instar larvae, except for a small amount that may be the remains of a maternal contribution (Figure 3B). In the case of dbeD102, only the 5′ half of the open reading frame was deleted; its 3′ breakpoint is in the middle of the KH domain of DBE (Figure 1, A and D).

To test whether the only essential gene affected by the dbeD29 lesion is the dbe gene, a transgenic rescue experiment was performed. A HindIII/StuI 6.5-kb genomic fragment contained the whole dbe gene and some 5′ sequences of genes CG4276 and CG4124 (Figure 1D); no coding sequence of either of these genes was included in this fragment. Transgenic lines carrying this fragment were generated. An insertion on the X-chromosome was chosen for the rescue experiment. Homozygous dbeD29 female flies that also contained this fragment were rescued to adulthood, although only 4 of 26 individual crosses showed this rescue, suggesting that one copy of the genomic rescue fragment may not provide high enough levels of dbe gene product to rescue consistently. Nonetheless, this confirmed that dbe is the only essential gene affected in line dbeD29.

Lethal Phase Determination

Homozygous mutant larvae of dbeD29, dbeD102, and dbeP appeared to be arrested at the first instar stage. They failed to increase in size or to develop into the second instar larval stage (as determined by the morphology of their mouth hooks; Ashburner, 1989). Homozygous larvae died 2–3 days after hatching, without any morphological defect. Given that dbeD102 and dbeP behave similarly to the protein null allele dbeD29, it is likely that dbeD29, dbeD102, and dbeP are all strong or null alleles of dbe.

Requirement for dbe in Developing Cells

First, germline clones homozygous for either dbeD29 or dbeD102 were generated using the dominant female sterile FLP/FRT technique (Chou and Perrimon, 1992; Chou and Perrimon, 1996). Mosaic females of genotype hsFLP; dbe P{hs-neo ry+ FRT}2L-40A/ovoD P{hs-neo ry+ FRT}2L-40A were crossed to wild-type males. Cells that are dbe+ will also carry the ovoD allele and arrest at stage 6 of oogenesis (Schulze and Bellen, 1996). Recombinant homozygous dbe cells can develop beyond this stage if their dbe genotype allows this, and they or their offspring will show any phenotype that is due to loss of dbe function in the female germline. When a dbe+ FRT chromosome was used as a positive control, 48% of the 52 females tested were fertile (Figure 5A). However, of 105 dbeD29 mosaic females and 75 dbeD102 mosaic females, none produced any eggs (Figure 5A). Ovaries from these females showed the stage 6 block characteristic of ovoD, implying that any homozygous dbe ovarioles were blocked at or before this stage (Chan, Brogna, and O'Kane, unpublished results) and that dbe+ activity is required during female germline development before this stage.

Figure 5.

Clonal analysis of dbe mutant phenotype. (A) Germline clone analysis. n is the number of ovoD P{hs-neo ry+ FRT}2L-40A/dbe P{hs-neo ry+ FRT}2L-40A females examined. Fertility is defined by the appearance of larvae after an incubation period of 5 days at 25°C. Sterility is defined by the absence of egg laying after an incubation period of 5 days at 25°C. Comparison of cell numbers in homozygous wild-type dbeP revertant (B) or dbeD102 mutant (C) patches (marked with forked) with cell numbers in twin spot clones (marked with crinkled) generated in larvae of genotype f; ck P{f+}30B FRT40A/dbe. n is the number of clones examined. A slope of 1 means that sizes of forked and crinkled clones are on average the same throughout the size range found.

Second, homozygous dbe eye clones (dbeP/dbeP; marked with w+/w+ and predicted to give a red-eyed phenotype) can be distinguished in principle from dbeP/dbe+ cells (nonrecombinant; marked with w+ and giving an orange-eyed phenotype) as well as the dbe+/dbe+ clones (twin-spot; marked with w− and giving a white-eyed phenotype). Somatic recombination was induced by x-ray irradiation 24–48 h AEL, i.e. first instar larval stage. No dark red homozygous dbe clones were observed after 1948 eyes were examined. However, 62 white dbe+/dbe+ twin spot clones were found. This experiment suggested that dbe is required for cell viability during eye development.

Third, to induce homozygous dbeD102 clones in the wing, X-irradiation was applied 48–96 h AEL (third instar). The doubling time of cell mass during this stage is ∼10–12 h, and at the end of this rapid cell proliferation (∼120 h AEL), differentiation occurs (Garcia-Bellido and Merriam, 1971); these data allow us to estimate the approximate birth date of any clone based on its size. To distinguish dbe homozygous clones, a chromosome that contains two wing phenotypic markers (a f+ transgene on a crinkled (ck) chromosome; P{f+}30A, ck; a gift of Dr. Jose F. de Celis) was used. In this situation, all f cells represented homozygous dbe clones, and the wild-type twin spot clones were marked with ck.

Wild-type twin spot clones (marked with ck) could be classified broadly as late (<20 cells, estimated birth 80–96 h AEL), intermediate (20–40 cells, estimated birth 64–80 h AEL), or early (>40 cells, estimated birth 48–60 h AEL). With late clones, homozygous dbeD102 clones (marked with f) were always found, and a linear relationship between the number of f and ck cells was observed (Figure 5C, left). With intermediate clones, although homozygous dbeD102 clones were still found, they were usually smaller than the twin-spot clones (Figure 5C). With early clones, virtually no homozygous dbeD102 clones were observed (Figure 5C). Similar results were obtained when dbeD29 was used. In contrast, when a dbe+ chromosome (a transposase-mediated revertant of dbeP) was used as a positive control, a linear relationship between the number of f and ck cells was observed, and ck twinspot clones were always associated with f clones (Figure 5B).

Hence, dbe+ is essential for survival of epithelial cells during early wing disk development. The presence of small-sized intermediate or late homozygous dbeD102 clones may be because of perdurance of the DBE gene product (Garcia-Bellido and Merriam, 1971) or to dbe+ not being required at later stages.

Requirement for dbe in Normal rRNA Processing

DBE is a nuclear protein, and within the nucleus it is preferentially localized in or near the nucleolus (Figure 4B). Because the nucleolus is the site of processing and covalent modification of pre-rRNA during ribosome assembly, we tested whether dbe mutant flies had any abnormality in pre-rRNA processing.

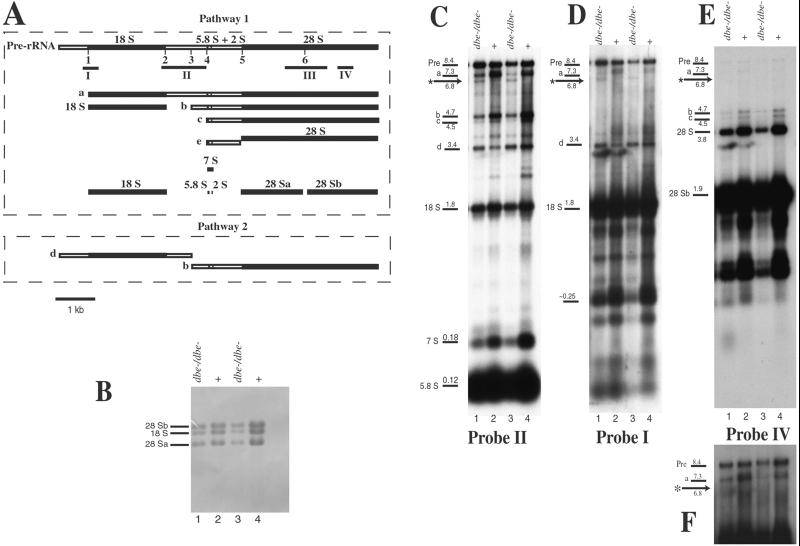

In Drosophila, as in other eukaryotes, the 28S, 18S, and 5.8S rRNAs are transcribed as a single transcription unit, and the mature rRNAs are generated by extensive pre-rRNA processing that involves both endonucleolytic and exonucleolytic steps (Long and Dawid, 1980) and base modification (Giordano et al., 1999). In Drosophila, initial processing of pre-rRNA can follow two alternative pathways. In one pathway (1, Figure 6A) the pre-rRNA is first cleaved at position 1, removing the external transcribed spacer and generating intermediate “a.” In the alternative pathway (2), the pre-rRNA is first cleaved at position 3 in the internal transcribed spacer, generating intermediates “d” and “b.” Following this initial difference, both pathways take the same maturation steps (see Figure 6 legend for more details).

Figure 6.

dbe mutants show defects in rRNA processing. (A) Pre-rRNA processing in D. melanogaster. The top line shows the structure of the pre-rRNA transcript; the numbers below it show the endonucleolytic sites; the solid boxes indicate regions corresponding to mature rRNA species, and the open boxes indicate the ETS and internal transcribed spacer regions (ITS). The small lines below the pre-rRNA map (I, II, III, and IV) indicate the positions of probes used. Probe I was prepared using primers 5′-GCTATATAAAAATGGCCGTATTCG-3′ and 5′-CACACGTCCCATAAGGTTCATG-3′ and was made up of nucleotides 669-1064 of pre-rRNA, including 193 nucleotides upstream of 18S rRNA and 203 nucleotides at the 5′-end of 18S rRNA. Probe II was prepared using primers 5′-TTCACGATGAACTTGGAATTCCC-3′ and 5′-CAGCATGGACTGCGATATGCG-3′ and consisted of nucleotides 2613–3705 of pre-rRNA, including the last 244 nucleotides of 18S rRNA, all of the 5.8S rRNA, and the spacer that lies between them. Probe III, homologous to 28S rRNA, was prepared using primers 5′-CTGGCGCTGTGGGATGAACC-3′ and 5′-GTTCCACAATTGGCTACGTAAC-3′ and was made up of nucleotides 5474–6518 of pre-rRNA, including the last 463 nucleotides of 28Sa, the first 482 nucleotides of 28Sb, and the spacer that lies between these two molecules. Probe IV was prepared using primers 5′-TATCGTCAATGAAATACCACTACTC-3′ and 5′-GTACTGAACACCGAGATCAAGTC-3′ and consisted of nucleotides 6990–7386 of pre-rRNA or a 397-nucleotide stretch of 28Sb rRNA, which lay 707-1103 nucleotides upstream of the 3′-end of the 28Sb rRNA and pre-rRNA. There are two alternative pathways of processing. In pathway 1 the first cleavage is at site 1 followed by cleavage at sites 2 through 6; in pathway 2 the first cleavage is at site 3 followed by cleavage at sites 1 and 2 and then 4 through 6. Below the diagram of the pre-rRNA are the rRNA intermediates found in wild type. Intermediate “d” is specific for pathway 2 (Long and Dawid, 1980). (B) Methylene blue staining of the gel used for the Northern blots shown in C, D, and E. Note the variation in the levels of rRNA between mutant and wild type, and note that relative levels of 18S, 28Sa, and 28Sb do not vary between lanes. (C) Northern blot of total nucleic acids purified from wild-type and dbeD29 larvae, probed with probe II (see A). Lanes 1 and 2 are 24-h-old larvae (1st instar), and lanes 3 and 4 are 48-h-old larvae (the mutant is arrested at 1st instar). Loading of DNA was approximately equalized to correct for variation in the RNA yield of the purification protocol. The genotype of larvae used is indicated above each lane. Lines to the left of the first lane indicate the positions of rRNA-processing intermediates (labeled as in A), and the size in kilobases is indicated above each line. The aberrant intermediate is indicated with an asterisk and arrow. The same pattern of intermediate products is observable when using probes complementary to the 28S region (Chan, Brogna, and O'Kane, unpublished results). (D) Hybridization of the same filter as shown in C with probe I (shown in A). Labeling of the bands is as in A. The 0.25-kb band may be a fragment from the 3′-end of the ETS, generated by cleavage 1 plus cleavage at a previously undetected upstream site in the ETS. The signals below band d are due to nonspecific probe hybridization; note their absence in lanes 3 and 4. (E) Hybridization of the same filter as shown in C with probe IV (shown in A). Labeling of the bands is as in A. The signals below the 28S band are due to nonspecific probe hybridization; note their absence in lanes 3 and 4. (F) A longer exposure of the top part of the blot shown in E, showing the absence of a 6.8-kb band.

Northern blots of rRNA from wild-type and from dbeD29 mutant larvae were probed with a number of fragments from different regions of the pre-rRNA molecule (Figure 6A). Probing with sequences from the center of pre-rRNA (probe II, Figure 6A) showed that in dbe mutant larvae there was an overall reduction of most intermediates and mature rRNA molecules (Figure 6C, compare lanes 1 and 3 with 2 and 4). The reduction appears to be due to a posttranscriptional abnormality, because the level of pre-rRNA (Pre) is not significantly reduced in the mutant (lane 1) relative to the wild-type (lane 2). This is most apparent if comparing the relative ratio of pre-rRNA (Pre) to the “a” intermediate in wild-type (lanes 2 and 4) and in mutant (lanes 1 and 3) larvae. In 48-h old larvae (lane 3 and 4) the level of pre-rRNA in the mutant appears also to be reduced relative to wild type; however, by this time the larvae are very sick and transcription may be reduced in general. However not all intermediates are reduced in the mutant; levels of the “d” intermediate look higher than in wild type (Figure 6D). Intermediate “d” is generated only in pathway 2, when the first endonucleolytic cleavage is at site 3 in the internal transcribed spacer (Figure 6A).

In addition, an aberrant pre-rRNA species is produced (Figure 6C, asterisk) in dbeD29 mutants. This new intermediate could have been generated by ectopic cleavage(s) 1) ∼500 nucleotides downstream of cleavage 1, 2) in the 3′-end of the pre-rRNA, ∼1600 nucleotides from the 3′-end of the 28S rRNA, or 3) at two positions, within ∼1600 nucleotides of each end, thus trimming both ends to give a product 1600 nucleotides smaller than the pre-rRNA. Several observations argue in favor of the second possibility. First, the levels of intermediate “d” are barely affected in dbe mutant larvae, suggesting that the 5′-end of the pre-rRNA remains intact. Second, the same filter was probed (Figure 6D) with a fragment from nucleotides 669 to 1064 of pre-rRNA, spanning cleavage 1 and covering only the first 203 nucleotides of 18S rRNA (probe I, Figure 6A). The abnormal cleavage product is still detected, implying that there cannot be a cleavage site at the 5′-end of pre-rRNA that lies downstream further than 203 bp from cleavage site 1. Therefore, the 6.8-kb band appears to have been generated by abnormal cleavage in the 3′-end of the pre-rRNA within the presumptive 28S rRNA. Third, the filter was therefore also hybridized with a probe corresponding to a region downstream of the expected site for this abnormal cleavage (probe IV, Figure 6A). This probe does not detect the 6.8-kb intermediate (Figure 6, E and F), supporting the model that the 6.8 kb intermediate is generated by cleavage in the 28S region, at ∼1600 nucleotides from the 3′-end.

The abnormal cleavage does not seem to lead to accumulation of a truncated 28S rRNA (Figure 6B), even 24 h after the aberrant cleavage started to be apparent (compare lanes 1 and 2 from 24-h-old larvae with lanes 3 and 4 from 48-h-old larvae). Hybridization with a 28S probe (probe III in Figure 6A) also did not show any indication of a truncated 28S or 28Sb (Chan, Brogna, and O'Kane, unpublished results).

The normally sized mature rRNAs could be of maternal origin; in larvae, rRNA inherited from embryos has a half-life of ∼48 h (Winkles et al., 1985). It is also possible that some mature rRNA could be produced with residual wild-type dbe of maternal origin.

DBE Has No Obvious role in Nuclear Import or Export

Given its homology to HuRip1 and its subnuclear localization, we wished to test whether DBE might play a role in either nuclear localization of the HIV-1 Rev protein (Pollard and Malim, 1998) or in nuclear export. In both wild-type and dbeD29 homozygous late first instar larval cells, a functional Rev-GFP fusion protein (Stauber et al., 1998) and another fusion of GFP to a nuclear localization signal (Shiga et al., 1996) were localized within the nucleus (Chan, Brogna, and O'Kane, unpublished results), suggesting that DBE has no role in nuclear import. Cytoplasmic localization of actin depends on the presence of nuclear export signals (Wada et al., 1998) and a functional CRM1-dependent nuclear export pathway (Collier et al., 2000). Actin localization appeared normal in homozygous dbeD29 first instar larvae (Chan, Brogna, and O'Kane, unpublished results), suggesting that dbe is not involved in the CRM1-dependent nuclear export pathway.

DISCUSSION

DBE: a Novel Single KH Domain Protein

DBE belongs to a subfamily of KH domain proteins that includes KRR1p and HuRip1. Unlike the other two KH domain protein subfamilies, members of the dbe subfamily contain only one KH domain and with no STAR domain-like homodimerization domains. The RNA-binding activity of KH domains requires cooperation of additional KH domain or other RNA-binding domains. Since the KH domain is situated in the middle of the DBE protein (Figure 1A), it is possible that there are some poorly defined homo- or hetero- oligomerization domains that are present at the N- or C- terminus of the protein. Also, there might also be other inconspicuous RNA-binding domains in the DBE sequence. In addition to RNA binding, it is still possible that the KH domain in DBE is involved in some other aspects of pre-rRNA processing e.g., as a docking molecule to bring proteins that are involved in pre-rRNA processing to the nucleolus.

Subcellular Localization of DBE Protein

A variable subnuclear localization of DBE was observed, although when any nonuniform DBE localization was observed in the nucleus, it included preferential localization in or near the nucleolus. There are a few possible explanations for this. Because nucleolar proteins are localized by interactions with other proteins or with nucleic acids (Carmo-Fonseca et al., 2000), it is possible that an unknown “nucleolar receptor” for DBE is present in a cell cycle-dependent or a cell type-dependent manner. When DBE is overexpressed, cells that contain more of this nucleolar receptor would be able to localize more DBE protein in the nucleolus (Figure 4B). However, in other cell types that contain less nucleolar receptor, overexpressed DBE would swamp the nucleolar localization mechanisms and be found throughout most of the nucleus. It is also possible that the subnuclear localization of DBE is dynamic, in a way that results in different cell types having different predominant localizations for the protein, or developmentally regulated; nucleolar structure, and hence probably its composition, shows much variability between cell types (Scheer and Hock, 1999) Alternatively, the distribution seen in Figure 4B may reflect differential trafficking of DBE in different cells in response to the heat shock used to induce expression of DBE protein. Because we cannot detect endogenous DBE by immunocytochemistry, we cannot tell whether it also shows a similar differential localization, which would reflect developmental regulation of DBE localization or nucleolar organization or possible cycling between different nuclear compartments.

dbe Shows Widespread Expression and Is Required for Cell Survival during Development

The maternal and ubiquitous embryonic expression of dbe suggests a possible housekeeping function for it. Consistent with this, dbe homozygous larvae died at first instar stage, presumably when maternal gene product is exhausted (see traces of DBE in first instar null mutants in Figure 3B), displaying no obvious developmental phenotype. Furthermore, in eye, germline, and wing cell clones generated during earlier larval development, DBE appeared to be essential for cell viability.

Homozygous dbe clones in wing epithelium were viable however, if generated late in larval life. The presence of homozygous dbe cells in late and some intermediate clones might be explained by perdurance of dbe+ product that was synthesized before clone induction (Garcia-Bellido and Merriam, 1971). Because the size of homozygous dbe clones never exceeded 20 cells, this suggested that any perduring dbe+ gene product could support only homozygous dbe cells through four to five rounds of cell division. However, any dbe cells that survive have no obvious defects in the ability of epithelial cells to differentiate and form trichomes, even in intermediate clones, when dbe clones are smaller than their twin spots and dbe+ product is therefore becoming limiting in later rounds of division. Therefore, either dbe+ product is required only for survival of dividing cells or dividing cells have a greater need for it than do postmitotic differentiating cells.

DBE Affects pre-rRNA Processing

The Northern blot analysis of pre-rRNA processing showed that dbe mutants have an overall reduction in the level of rRNA and that this may be a direct consequence of abnormal pre-rRNA processing. The appearance of a product shorter than “a” suggests that DBE protein specifically affects the specificity of either the first cleavage of pre-rRNA, and/or of intermediate “a.” The lack of 3′-truncated versions of intermediates “b,” “c,” 28S, or 28Sb suggests that the abnormal processing product is degraded rather than processed further. In contrast, levels of the “d” intermediate are not noticeably affected by the mutation; this suggests that the initial cleavage of pathway 2 at site 3 is unaffected in dbe mutants.

rRNA processing and maturation involve not only cleavage but also extensive site-specific base modification, principally pseudouridylation and 2′-O-ribose methylation. The complexity of these events requires a large number of components to catalyze them. A large number of proteins and snoRNAs have been implicated in them (Olson et al., 2000), and it is likely that many more still have to be found and characterized. The single-stranded nucleic acid-binding properties of KH domains suggest that DBE might act by binding to an rRNA precursor and/or to a snoRNA during rRNA processing. Although many chemical modifications of rRNA (and by implication the snoRNAs that guide them to the right location) appear to be dispensable for its essential function, a few snoRNAs are required for correct nucleolytic processing of rRNA precursors. These include the U3 (affects 5′-external transcribed spacer (ETS) and 18S regions), U8 (affects 5.8S and 28S rRNA), U14 (affects 18S rRNA), and U22 (affects 18S rRNA) members of the box C/D class of snoRNAs (Tollervey and Kiss, 1997). DBE protein could potentially bind to such snoRNAs during rRNA processing, or it could be necessary for processing of such snoRNAs from their precursor molecules (Weinstein and Steitz, 1999). Alternatively, DBE protein could be necessary for some chemical modifications of rRNA: some mutations that affect chemical modifications of rRNA, e.g., the Drosophila minifly mutation, which affects a homologue of the human dyskeratosis congenita disease gene (Heiss et al., 1988) and has an abnormal pseudouridylation pattern (Giordano et al., 1999), also lead to reduced levels of rRNA or its intermediates.

Our conclusion that processing of both 18S and 28S rRNA precursors is affected is in apparent contrast to those recently obtained by Sasaki et al. (2000), which suggest that mutations affecting the yeast DBE homologue, KRR1p, lead to loss of 18S rRNA synthesis but not to loss of 25S rRNA (the yeast equivalent of 28S rRNA) synthesis. However, the pulse–chase labeling of rRNA by Sasaki et al. (2000) would be sensitive to altered methylation in the krr1 mutant. They also observed that, although synthesis of methylated 25S rRNA was not blocked in krr1 mutants, it was slower than in wild type, indicating some requirement of KRR1p for normal processing of 25S rRNA precursors. Also, given the cross-phylum variation in the precise sites of rRNA modification directed by snoRNAs (Weinstein and Steitz, 1999), it is possible that similar molecular components could lead to modifications at different locations in rRNA or that interfering with modifications at the same sites could lead to different consequences in phyla with different downstream processing machinery.

The identification of dbe mutants and DBE protein should open the way to further identification of the molecules and events involved in rRNA processing. The conservation of rRNA-processing mechanisms and the high sequence similarity among DBE, KRR1p, and HuRip1 also suggest an important role for HuRip1 in humans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. Stephan Schneuwly, Daniel St. Johnston, and the Bloomington Drosophila Stock center for fly stocks and DNA clones; Dr. Sean Sweeney for embryo injections; Dr. Stefan Oehler for help with protein work; Dr. Jose de Celis for initial characterization of cell clones; Dr. Yong Zhang for help with cytology; and Drs. Cleta D'Sa-Eipper, G. Chinnadurai, Jane Pritchard, and Kevin Moffat for exchanging information and materials before publication. We thank Drs. Marie-Laure Parmentier, Hemi Mistry, Brian McCabe, Alicia Hidalgo, and David Hartley and members of the O'Kane lab for useful discussion. H-Y.E.C. was supported by scholarships from the Cambridge Commonwealth Trust, The Chinese University of Hong Kong Chung Chi College C.F. Hu Scholarship for Overseas Studies, and the Croucher Foundation. S.B. was supported by a Wellcome Trust project grant awarded to Michael Ashburner (ref. 057837/Z/99/Z), and work in the lab of S.B. and M. Ashburner is also supported by a Medical Research Council Program Grant to M. Ashburner, D. Gubb, and S. Russell.

REFERENCES

- Afshar K, Scholey J, Hawley RS. Identification of the chromosome localization domain of the Drosophila nod kinesin-like protein. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:833–843. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.4.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aris JP, Blobel G. Identification and characterization of a yeast nucleolar protein that is similar to a rat liver nucleolar protein. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:17–31. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M. Drosophila: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Brand A, Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 1993;118:401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brogna S. Nonsense mutations in the alcohol dehydrogenase gene of Drosophila melanogaster correlate with an abnormal 3′ end processing of the corresponding pre-mRNA. RNA. 1999;5:562–573. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299981359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns N, Grimwade B, Ross-Macdonald PB, Choi EY, Finberg K, Roeder GS, Snyder M. Large-scale analysis of gene expression, protein localization, and gene disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1087–1105. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.9.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Ortega JA, Hartenstein V. The embryonic development of Drosophila melanogaster. 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Carmo-Fonseca M, Mendes-Soares L, Campos I. To be or not to be in the nucleolus. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:E107–E112. doi: 10.1038/35014078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerdido A, Medina FJ. Subnucleolar location of fibrillarin and variation in its levels during the cell cycle and during differentiation of plant cells. Chromosoma. 1995;103:625–634. doi: 10.1007/BF00357689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan H-YE, Harris SJ, O'Kane CJ. Identification and characterization of kraken, a putative hydrolytic enzyme in Drosophila melanogaster. Gene. 1998;222:195–201. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00497-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan H-YE, Zhang Y, O'Kane CJ. Identification and characterization of the gene for Drosophila S20 ribosomal protein. Gene. 1997;200:85–89. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00378-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou TB, Perrimon N. Use of yeast site-specific recombinase to produce female chimeras in Drosophila. Genetics. 1992;131:643–653. doi: 10.1093/genetics/131.3.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou TB, Perrimon N. The autosomal FLP-DFS technique for generating germline mosaics in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1996;144:1673–1679. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier S, Chan H-YE, Toda T, McKimmie C, Johnson G, O'Kane CJ, Ashburner M. The Drosophila embargoed gene is required for larval progression and encodes the functional homolog of Schizosaccharomyces Crm1. Genetics. 2000;155:1799–1807. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.4.1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Celis JF, Barrio R, Kafatos FC. A gene complex acting downstream of dpp in Drosophila wing morphogenesis. Nature. 1996;381:421–424. doi: 10.1038/381421a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebersole TA, Chen Q, Justice MJ, Artzt K. The quaking gene product necessary in embryogenesis and myelination combines features of RNA binding and signal transduction proteins. Nat Genet. 1996;12:260–265. doi: 10.1038/ng0396-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Bellido A, Merriam JR. Genetic analysis of cell heredity in imaginal discs of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68:2222–2226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.9.2222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano E, Peluso I, Senger S, Furia M. minifly, a Drosophila gene required for ribosome biogenesis. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:1123–1133. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.6.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloor GB, Preston CR, Johnson-Schlitz DM, Nassif NA, Phillis RW, Benz WK, Robertson HM, Engels WR. Type I repressors of P element mobility. Genetics. 1993;135:81–95. doi: 10.1093/genetics/135.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gromadka R, Kaniak A, Slonimski PP, Rytka J. A novel cross-phylum family of proteins comprises a KRR1T (YCL059c) gene which is essential for viability of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells. Gene. 1996;171:27–32. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow E, Lane D. Antibodies: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan BA, Prokopenko SN, Breuer S, Zhang B, Paululat A, Bellen HJ. skittles, a Drosophila phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase, is required for cell viability, germline development and bristle morphology, but not for neurotransmitter release. Genetics. 1998;150:1527–1537. doi: 10.1093/genetics/150.4.1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiss NS, Knight SW, Vulliamy TJ, Klauck SM, Wiemann S, Mason PJ, Poustka A, Doka I. X-linked dyskeratosis congenita is caused by mutations in a highly conserved gene with putative nucleolar functions. Nat Genet. 1988;19:32–38. doi: 10.1038/ng0598-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamond AI, Earnshaw WC. Structure and function in the nucleus. Science. 1998;280:547–553. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5363.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsley D, Zimm G. The Genome of Drosophila melanogaster. New York: Academic Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Long EO, Dawid IB. Alternative pathways in the processing of ribosomal RNA precursor in Drosophila melanogaster. J Mol Biol. 1980;138:873–878. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(80)90070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Bermudo MD, Dunin-Borkowski OM, Brown NH. Specificity of PS integrin function during embryogenesis resides in the α subunit extracellular domain. EMBO J. 1997;16:4184–4193. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.14.4184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer BE, Malim MH. The HIV-1 Rev trans-activator shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1538–1547. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.13.1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miroux B, Walker JE. Over-production of proteins in Escherichia coli: mutant hosts that allow synthesis of some membrane proteins and globular proteins at high levels. J Mol Biol. 1996;260:289–298. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Kane CJ. Enhancer traps. In: Roberts DB, editor. Drosophila, A Practical Approach. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. pp. 131–178. [Google Scholar]

- Olson MOJ, Dundr M, Szebeni A. The nucleolus: an old factory with unexpected capabilities. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:189–196. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01738-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel NH. Imaginal neuronal subsets and other cell types in whole mount Drosophila embryos and larvae using antibody probes. Methods Cell Biol. 1994;44:445–487. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60927-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard VW, Malim MH. The HIV-1 Rev protein. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1998;52:491–532. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.52.1.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichhart JM, Ferrandon D. Green balancers. Drosophila Inform Serv. 1998;81:201–202. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DB, editor. Drosophila, A Practical Approach. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DB, Brock HW, Rudden NC, Evans-Roberts S. A genetic and cytogenetic analysis of the region surrounding the LSP1-β gene in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1985;109:145–156. doi: 10.1093/genetics/109.1.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson HM, Preston CR, Phillis RW, Johnson-Schlitz DM, Benz WK, Engels WR. A stable genomic source of P element transposase in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1988;118:461–470. doi: 10.1093/genetics/118.3.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rout MP, Aitchison JD, Suprapto A, Hjertaas K, Zhao Y, Chait BT. The yeast nuclear pore complex: composition, architecture, and transport mechanism. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:635–651. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.4.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin GM, Spradling AC. Genetic transformation of Drosophila with transposable vectors. Science. 1982;218:348–353. doi: 10.1126/science.6289436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell S, Sanchez-Soriano N, Carpenter ATC, Wright CR, Ashburner M. A SOX-domain encoding gene of Drosophila melanogaster functions in embryonic segmentation. Development. 1996;122:3669–3672. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.11.3669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch E, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Toh EA, Kikuchi Y. Yeast krr1p physically and functionally interacts with a novel essential kri1p, and both proteins are required for 40S ribosome biogenesis in the nucleolus. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7971–7979. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.21.7971-7979.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheer U, Hock R. Structure and function of the nucleolus. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:385–390. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(99)80054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneuwly S, Shortridge RD, Larrivee DC, Ono T, Ozaki M, Pak WL. Drosophila ninaA gene encodes an eye-specific cyclophilin (cyclosporine A binding protein) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5390–5394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.14.5390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze KL, Bellen HJ. Drosophila syntaxin is required for cell viability and may function in membrane formation and stabilization. Genetics. 1996;144:1713–1724. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiga Y, Tanaka-Matakatsu M, Hayashi S. A nuclear GFP/beta-galactosidase fusion protein as a marker for morphogenesis in living. Drosophila Dev Growth Differ. 1996;38:99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Siomi H, Matunis MJ, Michael WM, Dreyfuss G. The pre-mRNA binding K protein contains a novel evolutionary conserved motif. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:1193–1198. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.5.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauber RH, Horie K, Carney P, Hudson EA, Tarasova NI, Gaitanaris GA, Pavlakis GN. Development and applications of enhanced green fluorescent protein mutants. Biotechniques. 1998;24:462–469. doi: 10.2144/98243rr01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney ST, Broadie K, Keane J, Niemann H, O'Kane CJ. Targeted expression of tetanus toxin light chain in Drosophila specifically eliminates synaptic transmission and causes behavioral defects. Neuron. 1995;14:341–351. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90290-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tautz D, Hülskamp M, Sommer RJ. Whole mount in-situ hybridization in Drosophila. In: Wilkinson DG, editor. In-Situ Hybridization: A Practical Approach. Oxford, UK: IRL Press; 1992. pp. 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Thummel C, Pirrotta V. New CaSper P element vectors. Drosophila Inform Serv. 1991;71:150. [Google Scholar]

- Tollervey D, Kiss T. Function and synthesis of small nucleolar RNAs. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:337–342. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Török T, Tick G, Alvarado M, Kiss I. P-lacW insertional mutagenesis on the second chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster: isolation of lethals with different overgrowth phenotypes. Genetics. 1993;135:71–80. doi: 10.1093/genetics/135.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of protein from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uetz P, Giot L, Cagney G, Mansfield TA, Judson RS, Knight JR, Lockshon D, Narayan V, Srinivasas M, Pochart P, Qureshi-Emili A, Li Y, Godwin B, Conover D, Kalbfleisch T, Vijayadamodar G, Yang M, Johnston M, Fields S, Rothberg JM. A comprehensive analysis of protein-proteins interactions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2000;403:623–627. doi: 10.1038/35001009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada A, Fukuda M, Mishima M, Nishida E. Nuclear export of actin: a novel mechanism regulating the subcellular localization of a major cytoskeletal protein. EMBO J. 1998;17:1635–1641. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein LB, Steitz JA. Guided tours: from precursor snoRNA to functional snoRNP. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:378–384. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(99)80053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson C, Pearson RK, Bellen HJ, O'Kane CJ, Grossniklaus U, Gehring WJ. P-element-mediated enhancer detection: an efficient method for isolating and characterizing developmentally regulated genes in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1301–1313. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.9.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkles JA, Phillips WH, Grainger RM. Drosophila ribosomal RNA stability increases during slow growth conditions. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:7716–7720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimowska G, Aris JP, Paddy MR. A Drosophila Tpr protein homolog is localized both in the extrachromosomal channel network and to nuclear pore complexes. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:927–944. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.8.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]