Abstract

We developed a highly efficient, biocompatible surface coating that disperses bacterial biofilms through enzymatic cleavage of the extracellular biofilm matrix. The coating was fabricated by binding the naturally existing enzyme dispersin B (DspB) to surface-attached polymer matrices constructed via a layer-by-layer (LbL) deposition technique. LbL matrices were assembled through electrostatic interactions of poly(allylamine hydrochloride) (PAH) and poly(methacrylic acid) (PMAA), followed by chemical crosslinking with glutaraldehyde and pH triggered removal of PMAA, producing a stable PAH hydrogel matrix used for DspB loading. The amount of DspB loaded increased linearly with the number of PAH layers in surface hydrogels. DspB was retained within these coatings in the pH range from 4 to 7.5. DspB-loaded coatings inhibited biofilm formation by two clinical strains of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Biofilm inhibition was ≥ 98% compared to mock-loaded coatings as determined by CFU enumeration. In addition, DspB-loaded coatings did not inhibit attachment or growth of cultured human osteoblast cells. We suggest that the use of DspB-loaded multilayer coatings presents a promising method for creating biocompatible surfaces with high antibiofilm efficiency, especially when combined with conventional antimicrobial treatment of dispersed bacteria.

Keywords: biocompatibility, biofilm inhibition, cytotoxicity, dispersin B, layer-by-layer, Staphylococcus epidermidis

INRODUCTION

Bacterial attachment and biofilm development at surfaces of implanted biomedical devices are inherent to infection and inflammation. For example, colonization with Staphylococcus epidermidis and Escherichia coli is a common cause of intravascular catheter-associated infection, and Staphylococcus aureus is associated with infection at surfaces of metallic implants.1,2 As biofilms grow and infection progresses, initially reversible bacterial adhesion becomes irreversible, and bacterial cells build up a three-dimensional extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix. This matrix supports bacterial functions in the colonies, and significantly elevates bacterial resistance to antibiotic treatment as compared to that of planktonic cells.3

One class of compounds with a significant potential in fighting bacterial infections is proteins and peptides (short proteins with less than 50 aminoacids, later on in this paper also called `proteins' for simplicity). The most common mechanism of antimicrobial activity of proteins includes penetration in cell membrane and induction of cell lysis.4,5,6 Such mechanism is usually found for positively charged proteins (antimicrobial peptides). Another class of proteins does not attack bacterial membrane but rather degrades biofilm matrix and disperses their colonies. Proteins of these type include enzymes such as glycosidases, proteases, and deoxyribonucleases.7 A significant advantage of using protein-like antibacterial agents compared to traditional antibiotics is their lower propensity in developing bacterial resistance to antimicrobial treatment.8,9 In addition, biofilm-dispersing proteins are usually less toxic for cells than membrane-permeating antibacterial agents,7,9 as often they do not carry positive charges usually required for antibacterial activity of membrane-active proteins.

For efficient, localized protection against bioflm growth, surfaces were functionalized with monolayers of proteins achieved through adsorption,10,11,12,13,14,15 or covalent attachment. 16,17,18,19 However, antimicrobial proteins can lose their activity within surface monolayers,12,20 and the overall amount of proteins in monolayers is small. Incorporation of proteins within layer-by-layer (LbL) coatings enables bringing larger amounts of bioactive compounds to surfaces for antibacterial applications.21,22,23,24,25,26 In addition, the LbL technique enables the use of a variety of polymers, supports film construction in aqueous solutions, and allows for deposition of conformal coatings on substrates of complex shapes. Moreover, the amount of surface-bound bioactive compounds can be controlled by the thickness of the LbL coatings, determined by number of deposited layers.

There exist two routes to incorporate proteins within LbL films. A more traditional route is based on sequential absorption of proteins and polymers at surfaces.21,22,23 This route requires the use of large volumes of protein solutions, often not available in the case of precious bioactive compounds. In addition, sequential deposition of proteins at surfaces can be aggravated with film erosion.27 Another route pursued here relies on a single-step loading of proteins within pre-formed, LbL-derived hydrogels matrices.28,29

All previous reports on protein-containing, biofilm-resistant LbL coatings rely on killing bacteria at surfaces or in their vicinity. When killed, microorganisms usually accumulate at surfaces, reducing coating's antimicrobial efficiency. To remove dead cells adhered to surfaces at different stages of the biofilm development, “lift off” polyelectrolyte multilayers (PEMs) or slowly eroding coatings have been reported. 30,31 However, there exists a concern that complete erosion of PEM films might results in significant losses of antibacterial surface activity.

In the present study, we explore a strategy for fabricating anti-infective surfaces that involves incorporation of a biofilm-dispersing enzyme within an LBL-derived surface hydrogels. The enzyme of our choice was a biofilm-degrading glycoside hydrolase dispersin B (DspB), which cleaves poly-N-acetylglucosamine (PNAG) polysaccharide. PNAG is a component of the biofilm matrix produced by the Gram-positive bacteria S. aureus32 and S. epidermidis,33 as well as several Gram-negative bacteria including Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, Bordetella spp., Burkholderia spp., E. coli and Yersinia pestis.34,35,36,37 The fact that DspB does not inhibit bacterial growth minimizes the chances for development of bacterial resistance to the treatment. Antibiofilm activities of DspB as a monolayer and combination of DspB with antibiotics on the surfaces of polyurethane catheters have been reported earlier.14,15 Here, for the first time, we exploit the potential of LbL-enabled coatings to assure efficient binding of large amounts of DspB at surfaces. In contrast to our previous work on reversible, pH-triggered binding of antibacterial proteins within LbL-derived coatings,29 here we demonstrate irreversible, pH-independent retention of DspB molecules within surface coatings. DspB-containing LbL coatings were highly efficient showing at least 98% inhibition in biofilm growth. At the same time, the coatings were highly biocompatible with attachment and growth of cultured osteoblast cells.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials

Poly(methacrylic acid) (PMAA; Mw 150 kDa), poly(allylamine hydrochloride) (PAH; Mw 70 kDa), glutaraldehyde (GA) 70% solution, monobasic and dibasic sodium phosphate, hydrochloric acid, sodium hydroxide, sodium chloride, magnesium chloride, potassium chloride, 4-nitrophenyl phosphate bis(cyclohexylammonium) salt (pNPP), 5% diethanolamine and bovine serum albumin (BSA) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. All chemicals were used without any further purification. Dispersin B (DspB) was purified from an overexpressing strain of E. coli as previously described.38 Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-DspB monoclonal antibodies were purchased from BioGenes GmbH (Traunstein, Germany). Millipore filtered water (Milli-Q system) with a resistivity of 18.2 MΩ was used in all experiments. D2O with 99.9% isotope content was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories and was used as received. Silicon (110) wafers were prime grade, p-type, 500 μm thickness, with native oxide layer ~ 2 nm thick, and were purchased from University Wafer.

Preparation of GA-crosslinked PMAA Surface Hydrogels

Hydrogels were deposited onto the surfaces of silicon wafers, which were pre-cleaned under a quartz UV lamp, soaked in concentrated sulfuric acid, and then carefully rinsed with Milli-Q water. Deposition of hydrogen-bonded PAH/PMAA multilayers at the surface of silicon wafers was performed using 0.2 mg/mL polymer solutions at pH 9 (water for PAH, and 0.01 M phosphate buffer for PMAA). Polymers were allowed to adsorb for 15 min, and two rinsing steps with a phosphate buffer at pH 9 were applied after each deposition step. After the desired number of bilayers was deposited, the film was chemically crosslinked by subsequent treatment with a crosslinker solution of GA with concentration 2.8 mg/mL (4 mg/mL of 70% solution) at pH 3.6 supported by 0.01 M phosphate buffer. To remove PMAA, PAH crosslinked multilayers were exposed to a 0.01 M phosphate buffer solution containing 0.3 M NaCl at pH 8.5 for 5 min and then to 0.01 M phosphate buffer solution at pH 11.8 for 1 min. Finally, the hydrogels were rinsed with pure water and dried under flowing nitrogen gas.

Incorporation of DspB within PAH Films

To load DspB, PAH hydrogels crosslinked with GA were exposed to solutions of DspB (0.5 mg/mL in 0.01 M phosphate buffer at pH 7.5, 1 mL) overnight to achieve complete absorption within the films.

Release of DspB from PAH Films Triggered by pH

To study pH-triggered release of DspB, loaded PMAA hydrogel films were exposed to 0.01 M phosphate buffer solutions containing 0.2 M NaCl with pH set at various values between 4.0 and 7.5 at 25 °C.

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy in Attenuated Total Reflection Mode (FTIR-ATR)

In situ ATR-FTIR experiments were performed with a Bruker Equinox-55 Fourier transform infrared spectrometer equipped with a narrow-band mercury cadmium telluride detector. The ATR Si crystal (50 mm × 20 mm × 2 mm, cut at 45°, Harrick Scientific) was installed within a flow-through stainless steel cell filled with D2O solutions.

Phase-Modulated Ellipsometry Measurements of Dry Films

Ellipsometry measurements were performed using a home-built, single-wavelength, phase-modulated ellipsometer at 65° of incidence.39 Optical properties of the substrates and oxide layer thickness were determined prior to polymer deposition. In measurements of dry film thickness, the refractive index was fixed at a value of 1.5.

Procedure for Direct Enzyme Linked-Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Duplicate 10-layer wafers were eluted for 30 or 90 min in 1.5 mL of potassium phosphate buffer pH 5.8, 6.6 or 7.4 at 25 °C. Elutes were analyzed in a DspB ELISA assay using anti-DspB monoclonal antibodies. In this direct ELISA method, the wells were first coated with 50 μL per well of DspB standard or test samples diluted in phosphate buffered saline (PBS; 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na3PO4, 2 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.2) at 4°C overnight. Unbound DspB was removed by rinsing with wash buffer (PBS, 0.05% Tween-20) and the wells were blocked with 200 μL per well blocking solution (PBS, 2% BSA). Detection antibody solution (alkaline phosphate conjugated anti-DspB monoclonal antibody) was added to the wells (100 μL/well) and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. The unbound antibodies were removed by rinsing with wash buffer. The DspB bound antibodies were detected by incubation with 50 μL/well substrate solution containing 2mM pNPP [4-nitrophenyl phosphate bis(cyclohexylammonium) salt], 5% diethanolamine, 0.5 mM MgCl2 (pH 9.8). The yellow color that developed was quantified by measuring optical density at 405 nm (OD405). DspB concentrations in test samples were extrapolated using the standard curve developed by plotting concentrations of DspB standards against corresponding OD405 values.

Biofilm Assay

A plastic cloning cylinder (5 mm inside diam × 9 mm high) was attached to the surface of the wafer using high vacuum grease. This created a “well” with the wafer surface as the bottom, which was then filled with 200 μL of S. epidermidis strain NJ 970940 or strain 146741 inoculum in fresh Tryptic Soy broth (BD Diagnostic Systems). Inocula contained ca. 104–105 CFU/mL and were prepared as previously described 42. Wafers were incubated at 37°C. After the specified amount of time, the broth was aspirated from the well with a pipette. The plastic cylinder was removed from the wafer, and the surface of the wafer was rinsed with 10 mL of saline using a pipette to remove loosely attached cells. The wafer was placed in 5 mL of saline (0.9% NaCl) in a 50 mL centrifuge tube and sonicated for 2 × 30 sec to detach the biofilm cells from the wafer. Each sonicate was analyzed in two ways. First, the absorbance of the sonicate was measured in a BioRad Benchmark microtiter plate reader set to 490 nm. Second, the CFU/mL values of each sonicate were measured by dilution plating on agar plates. In this serial dilution assay, the limit of detection was 1,000 CFU/wafer. Each experiment was performed using duplicate wafers and was repeated at least twice.

Osteoblast Cells Culture

Human fetal osteoblast cells (HFOB 1.19, ATCC # CRL-11372) were used for the evaluation of cell response on (PAH)2 films loaded with DspB. Cells were cultured in medium containing a 1:1 mixture of Ham's F12 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA ) and Dulbeccco's Modified Eagle Medium-Low Glucose (DMEM-LG; Cellgro) supplemented with antibiotic solution (1% penicillin-streptomycin; Sigma-Aldrich) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Atlanta Biologicals). Cells were incubated in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C with medium change every 3 d. All cells used in this study were between 4 and 6 passages.

Cell Seeding on LbL Films

Silicon wafers coated with (PAH)2 films were sterilized by dipping into 70% ethanol for one hour followed by three washes in sterile PBS pH 7.4. Those samples were loaded with DspB overnight. As controls, wafers coated with as-synthesized, DspB-free (PAH)2 films, as well as bare wafers, sterilized by 70% ethanol, were used. All wafers were then thoroughly washed in fresh medium. The wafers were placed in the wells of a 12-well microtiter plate and a volume of 40 μL of HFOB cell suspension containing 2 × 104 cells was pipetted onto each wafer. Cells were allowed to attach for 2 h followed by addition of 1 mL medium per well. Cultures were maintained for 4 d with medium replacement every other day. After 1 d and 4 d, wafers were removed and characterized for cell attachment, cell proliferation, live/dead viability and morphological analysis.

Quantification of Cell numbers on LbL Films

After incubation, cell numbers were determined using an MTS assay kit (Promega). Briefly, samples were transferred to a fresh 12-well plate. A volume of 200 μL the combined tetrazolium salt (MTS)/phenazine methosulfate (PMS) solution (20:1) was pipetted into each well containing 1 mL of culture medium. The plate was then incubated for 2 h at 37 °C in a humidified and 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cell proliferation was expressed as absorbance at 490 nm as measured in a microplate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT). Each group was measured in triplicate. Cell number was determined through a standard curve established by our lab and shown in Figure S1 in Supporting Information.

Immunofluorescence Staining

Fluorescence staining was performed to observe the formation of actin filaments after 1 d and 4 d. In brief, cells cultured on LBL hydrogels matrices were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS at 4 °C for 30 min, and then rinsed three times in PBS. The cells were permeabilized for 5 min in 1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS, followed by blocking with 1% BSA in PBS for 30 min. Cells were stained for 30 min with FITC-labeled phalloidin (1:100; Sigma-Aldrich) to stain actin fibers, rinsed three times with PBS, and mounted on glass slides. Images were captured using a Nikon C1 confocal microscope at a magnification of 10× objective.

Live/Dead Cell Viability Assay

Cell viability quantified using a live/dead cell viability assay kit (Invitrogen) after 1 d and 4 d. The cells were vital fluorescence double-stained based on membrane integrity and intracellular esterase activity as per the manufacturer's protocols. Briefly, cell-seeded scaffolds were incubated at room temperature for 30 min in PBS containing 2 μM calcein AM (green) and 4 μM ethidium homodimer-1 (red). Cells stained green (live) and red (dead) were imaged using a Nikon C1 confocal microscope with a 10× objective.

Cell Differentiation

The retention of the osteoblastic phenotype at day 4 was evaluated by measuring the alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity. After incubation, specimens were moved to new 24-well plates and treated with 1 mL 1% Triton X-100, which was supplemented with 5 mM MgCl2, and then with a freezing and thawing process three times to extract the intracellular phosphatase. The activity of ALP in cell lysates was determined in diethanolamine substrate buffer (1X) containing 1mg p-nitrophenyl phosphate in 96-well plates and was measured with a microplate reader (BioTek) at 405 nm. 2N sodium hydroxide in PBS was used as blank. The results for ALP activity were normalized by the total DNA amount from DNA assay in each ALP sample well. Specifically, DNA was measured using the dsDNA assay kit (PicoGreen p7589 Invitrogen, Ltd) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 100 μL of sample was added into 96 well plate and mixed with equal quantity of 1X dsDNA assay in TE buffer after 5 min incubation in the dark at room temperature. Samples and standard curve were read on a microplate reader (BioTek) at 485/520 nm (excitation/emission). At least three scaffolds were evaluated.

Statistical Analysis

All quantitative data are reported as mean ± standard deviation. At least three samples per time point were evaluated for statistical analysis. Statistical differences among the groups of scaffolds were determined by performing a Student t test. A confidence interval of P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Construction of PAH Hydrogel Matrices and their Loading with DspB

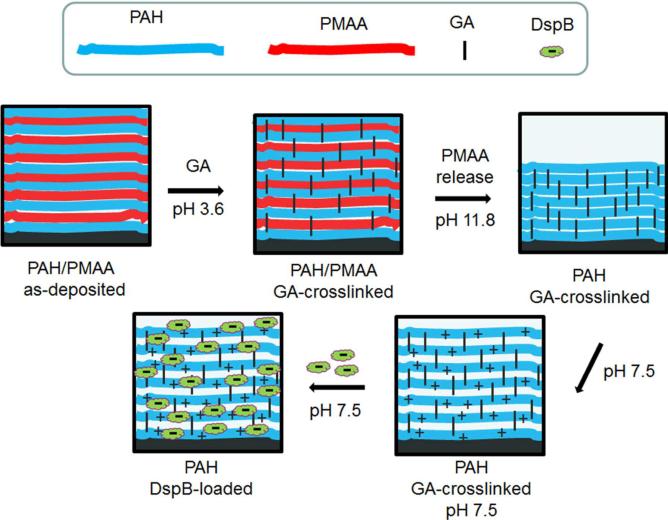

Our approach was to construct a polymer coating which enables highly efficient and controlled binding of DspB at surfaces. Because of the negative charge of DspB at pH 7.5 (pKa ~ 5.7–6.1),43 we aimed to create a positively charged coating to assist trapping DspB through electrostatic interactions. Using a versatile LbL strategy that allows facile deposition of functional coatings at a variety of surfaces, we have constructed positively charged, hydrogel-like, ultrathin polymer matrices for enzyme loading (Figure 1). As in the case of conventional LbL films, the thickness of such pre-constructed hydrogel coatings can be fine-tuned at the nm-level. At the same time, unlike conventional LbL films whose construction is associated with multi-step application and disposal of large volumes of solutions, surface hydrogels enable deposition of payload in a single step, which is the preferred method for surface functionalization using costly and precious bioactive compounds.

Figure 1.

Preparation of functional DspB-loaded PAH films.

The hydrogel matrix construction was based on the earlier described strategy of selective chemical crosslinking of two-component LbL films, followed by release of an uncrosslinked film component.44,45 Our procedure included constructing LbL films via sequential deposition of poly(allyl amine) (PAH) and poly(methacrylic acid) (PMAA), followed by crosslinking of PAH/PMAA films with glutaraldehyde (GA). Uncrosslinked PMAA was then released by the film by exposure to high pH (pH 11.8), which released PMAA due to deprotonation of PAH and dissociation of –COO−/–NH+3 ionic bonds. A similar procedure has been reported for PAH/poly(acrylic acid) (PAA) multilayers.45 Note that GA crosslinking strategy was also applied to PAH/poly(styrene sulfonate) (PSS) multilayers, but the use of strongly electrostatically bound PSS prevented release of PSS from the film and impeded formation of a positively charged hydrogel.46 Still another reported approach to synthesize PAH hydrogels, though not pursued in this work, includes PAH crosslinking via alternating immersion into PAH and GA solutions.47 Here, for the first time, we are exploring a potential of multilayer-derived PAH hydrogels as matrices for loading of biologically active molecules.

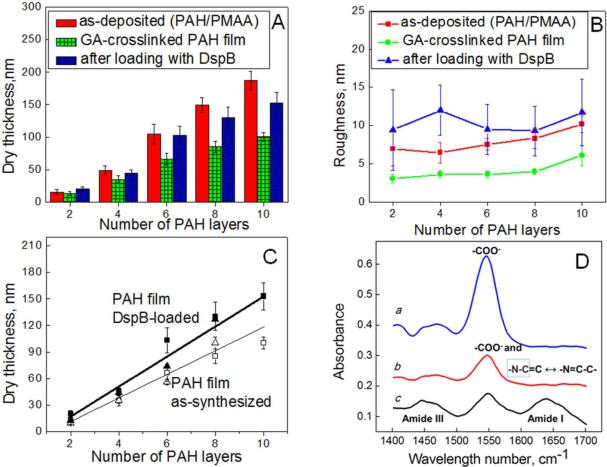

The hydrogel construction and loading with DspB have been studied using several complimentary techniques: atomic force microscopy (AFM), ellipsometry and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy in attenuated total reflection mode (FTIR-ATR) (Figure 2). Figure 2A summaries AFM measurements of the step height made on dry films with a razor blade. The dry thicknesses of as-deposited PAH/PMAA films increased with layer number, with smaller incremental increase for first and second closest-to-the-substrate bilayers (5 and 8 nm, respectively), and with linear growth at larger layer numbers with incremental thickness of ~17 nm per PAH/PMAA bilayer. This relatively high bilayer thickness is explained by the pH conditions chosen for the multilayer construction. At a deposition pH of 9, PAH chains have relatively low charge density (pKa of ~ 8.8),48 and deposits at the surface within relatively thick layers in loopy conformations.49 However, the amount of PAH deposited within the closest-to-the-substrate monolayer was small (with dry thickness of ~ 2 nm). Considering that under these conditions surface coverage might be incomplete, we used LbL films with two or more PAH/PMAA bilayers. Figure 2A also shows that after GA crosslinking and exposure to pH 11.8, the thickness of PAH/PMAA films decreased, suggesting release of PMAA. The thickness decrease for the films of two PAH/PMAA bilayers was smaller (~ 15%) than that for films with higher number of deposited bilayers. These data indicate that PMAA is retained within two closest-to-the-substrate PAH/PMAA bilayers. Reluctant PMAA release from closest-to-the-substrate layers is due to the substrate-proximity effect known for LbL films.50 Taking into account these retained PMAA components, ~ 40% decrease in thickness occurred for PAH/PMAA bilayers with n > 2 (where n is the bilayer number). Since independent ellipsometry measurements of incremental PAH and PMAA thicknesses during film deposition showed 3:2 PAH:PMAA bilayer composition, this 40% decrease in dry thickness indicates complete release of PMAA from PAH/PMAA bilayers with n > 2. Figure 2B illustrates that PAH hydrogels (consisting of two to ten PAH/PMAA bilayer) have a relatively smooth surface, as indicated by a decrease in the root-mean-square (RMS) roughness of 8 ± 1 and 4 ± 0.5 nm before and after crosslinking, respectively. Figure 2C demonstrates that AFM results were consistent within 15% with ellipsometry measurements of film thickness. Release of PMAA after exposure of GA-crosslinked multilayers to pH 11.8 was confirmed by in situ FTIR-ATR, performed in D2O solutions at pH 7.5 (Figure 2D). Spectrum a in Figure 2D refers to (PAH/PMAA)5 film deposited at pH 9 and immersed in 0.01 M phosphate buffer solution at pH 7.5. It shows a prominent band at ~1549 cm−1 which is associated with asymmetric stretching vibration of carboxylic groups. Spectrum b in Figure 2D corresponds to GA-crosslinked (PAH/PMAA)5 film after pH-triggered PMAA release. The remaining intensity of the band at 1549 cm−1 (spectrum b) after PMAA release is due to a fraction of PMAA retained within the first two closest-to-the-substrate PAH/PMAA bilayers, and might also include contributions from stretching vibrations of resonantly stabilized Schiff base emerged as a result of chemical crosslinking between GA and PAH.51

Figure 2.

AFM studies on dry thickness (A) and roughness (B) of as-deposited PAH/PMAA, as well as GA-crosslinked and DspB-loaded PAH films. (C) Dry thickness of GA-crosslinked PAH films as a function of number of PAH layers before (□ – AFM, △ – ellipsometry) and after DspB loading (■ – AFM, ▲ – ellipsometry). (D) In situ FTIR-ATR data from D2O solutions on a Si ATR crystal. All spectra were taken at pD 7.5: spectrum a – (PAH/PMAA)5; spectrum b – GA-crosslinked (PAH)5 after PMAA release at pD 11.8; spectrum c – DspB-loaded (PAH)5.

At pH 7.5, the amino groups of PAH matrix were protonated and available for loading of anionic molecules. Figure 2A–D demonstrates changes in the hydrogel thickness, surface roughness, and chemical composition as a result of DspB binding. The amount of DspB within the film increased with number of layers within PAH hydrogel (Fig 2A and C), suggesting loading of DspB within the PAH hydrogels rather than its adsorption at the film surface. Figure 2B shows that incorporation of DspB within PAH films (for number of PAH/PMAA bilayers from two to ten) resulted in an increase in surface roughness from 4 ± 1 to 10 ± 1 nm, and spectrum c in Figure 2D indicates the emergence of characteristic protein vibrational bands. These bands include amide I vibrations in the 1600–1700 cm−1 region for the most part associated with stretching vibrations hydrogen-bonded carbonyl groups in proteins, and the amide III region at ~1450 cm−1. Note that the amide II band, related to C-N stretching coupled with N-H bending vibrations, was not pronounced in the 1500–1600 cm−1 region, because of the N-H to N-D exchange in D2O solution.52 Inclusion of DspB within PAH film was homogeneous throughout the surface hydrogel matrix (except for the first closest-to-the-substrate bilayers), giving a loading amount 0.72 μg/cm2 per PAH layer. In this calculation, we have assumed a protein density of 1.4 mg/mL.53 From these estimates, a ~ 6-nm distance between centers of protein globules loaded within the coatings has also been calculated. Such efficient inclusion of within PAH hydrogels indicates that the hydrogel mesh size is large enough to allow transport of DspB through the matrix. DspB is a globular protein approximately 6 nm in diameter.43

Control experiments performed using ellipsometry were consistent with inclusion of DspB within the PAH hydrogel, and a predominantly electrostatic force driving loading of DspB. One of these experiments showed that the amount of DspB adsorbed at the surface of as-deposited (PAH/PMAA)1.5 film (with PAH as the outermost layer) was approximately 2 nm. Another control experiment showed that protein absorption was completely prevented when the protein and the surface coating carry charge of the same sign. Specifically, no adsorption of DspB occurred at the negatively charged surface of PMAA-topped (PAH/PMAA)2 films.

Inhibition of S. epidermidis Biofilm Growth by DspB-Loaded Coatings

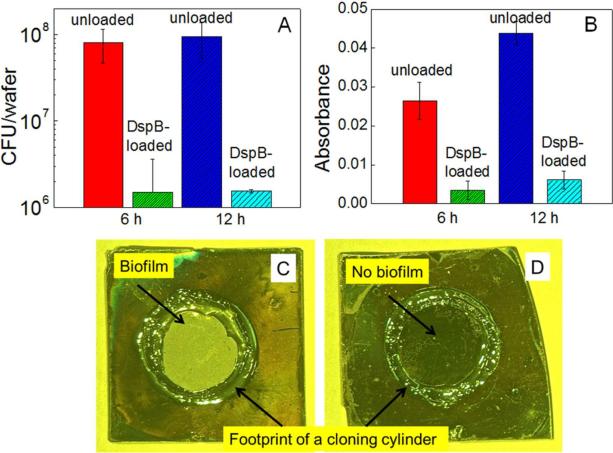

To study retention of biological activity of DspB after binding at a surface, the protein-loaded PAH hydrogel films were challenged with S. epidermidis NJ 9709, a biofilm-forming strain isolated from an infected catheter.40 Figure 3 shows bacterial growth at as-synthesized and DspB-loaded PAH coatings at two time points: 6 and 12 h. A significant inhibition of biofilm development on DspB-loaded PAH hydrogels was observed for both time points. Quantification of biofilm inhibition using the dilution plating technique indicated at least 98% reduction in surface coverage with S. epidermidis NJ 9709 with DspB-loaded (PAH)10 films as compared with as synthesized PAH films (Figure 3A). A similarly significant reduction in bacterial colonization was also evident from the optical density measurements (Figure 3B). Optical images of as-synthesized and DspB-loaded (PAH)10 films indicate the dramatic reduction of S. epidermidis biofilm formation at PAH hydrogels carrying DspB payload after 12 h (Figure 3C and D). The antibiofilm activity of DspB-loaded PAH hydrogels was also examined using S. epidermidis strain 1467, and results indicated a similar inhibition of biofilm formation. The data are shown in Figure S2 in Supporting Information.

Figure 3.

Quantification of S.epidermidis NJ 9709 growth on as-synthesized and DspB-loaded (PAH)10 films using dilution plating (A), and optical density measurements (B), as well as optical images of as-synthesized and DspB-loaded (PAH)10 films (C and D, respectively) after growth of S. epidermidis for 12 h.

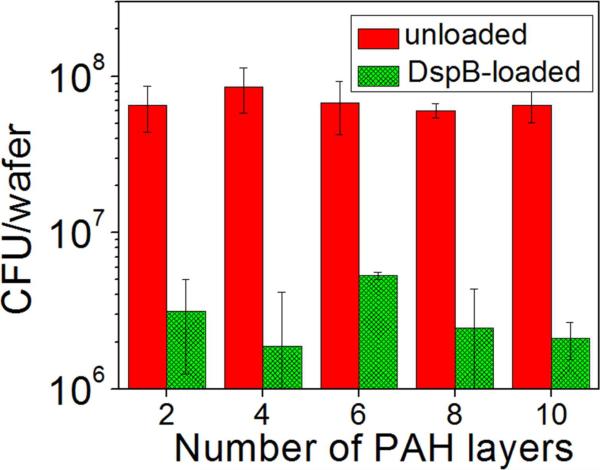

To elucidate the effect of the amount of loaded DspB on the antibiofilm efficacy of the coating, DspB was loaded within PAH hydrogels with different number of PAH layers, and S. epidermidis NJ 9709 was incubated in contact with these coatings. Figure 4 shows that biofilm dispersing properties of the coatings were preserved for films containing as few as two PAH layers. In contrast, as-synthesized, DspB-free surface hydrogels induced strong adhesion and biofilm development of S. epidermidis NJ 9709. The independence of the antibacterial efficacy of DspB-loaded coatings on the total amount on DspB within the coating suggests that the coatings are likely to act through contacting their surface with the biofilm rather than through leaching of DspB in the surrounding solution. This result also shows that the thickness of the coating can be significantly decreased, and both number of hydrogel construction steps, and that the consumption of DspB can be reduced without compromising the antibiofilm activity of the coating.

Figure 4.

Quantification of 6 hour S.epidermidis NJ 9709 growth at as-synthesized and DspB-loaded PAH hydrogels with different number of PAH layers using dilution plating.

Retention of DspB within the PAH Matrix

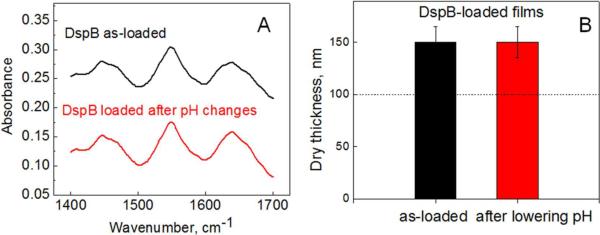

Because DspB is bound within the PAH hydrogels through non-covalent interactions, and a decrease in pH occurs during S. epidermidis growth,29 we were then interested in exploring the retention of DspB within the coating upon pH variations. In recent work, we explored anionic rather than cationic surface hydrogels as matrices for loading and release of biologically active molecules in response to pH variations.29 We found that the hydrogel matrix built from a weak polyacid (PMAA) was highly efficient in loading and retention of positively charged proteins at a constant pH (pH = 7.5), but released them at lower pH values29. Here, we aimed to investigate the effect of pH on retention of DspB within cationic PAH surface hydrogels. Similar to protein-loaded PMAA hydrogels,29 a change in the charge balance occurs in the case of DspB-loaded PAH hydrogels upon pH variations. In particular, DspB, with its pKa value of ~5.7–6.1, changes its charge from negative to positive when pH is lowered from its original value of 7.5 (DspB carries 9 negative charges at pH 7.5, and 5 positive net charges at pH 5.5). However, in sharp contrast to the PMAA matrix,29 here we found that the PAH matrix did not release protein payload in response to pH-triggered charge imbalance. This conclusion is supported by the data obtained using three complementary techniques. First, (PAH)5 hydrogels were constructed in situ and then loaded with DspB films at pH 7.5. Films were incubated in 0.01 M phosphate buffered heavy water solution containing 0.2 M NaCl at pH 4 for three days. We observed no changes in the intensities of amide I and amide III DspB bands using in situ FTIR-ATR (Figure 5A). Second, we employed a highly sensitive ELISA technique to detect possible leaching of DspB into solution (the limit of detection of DspB using Dispersin ® ELISA kit is 10 ng/mL). Elutes were analyzed with a DspB ELISA assay using anti-DspB monoclonal antibodies. Anti-DspB monoclonal antibody and alkaline phosphate conjugate were bound with DspB and detected by incubation with p nitrophenyl phosphate, which results in emergence of the absorption band at 405 nm (also seen as yellow color), enabling quantification of DspB. We found that elutes collected after 30 and 90 min from both as-synthesized and DspB-loaded (PAH)10 coatings were not absorbing at 405 nm. Finally, strong retention of DspB within PAH coatings has been also confirmed by AFM measurements of thicknesses of dry PAH films. In these experiments (Figure 5B), we observed no changes in the thickness of (PAH)10 matrix loaded with DspB, after pH was varied from 7.5 to 4 in 0.01 M phosphate buffer with additional 0.2 M NaCl. For DspB-containing films with different thicknesses, we confirmed, using ellipsometry, that the coatings remained stable in the pH range between 7.5 to 4 independently on number of PAH layers (data not shown). We explain this strong retention of DspB within PAH films by strong ionic coupling between primary amino groups of PAH and negative charges at DspB,43 as well as by a possible additional contribution of nonelectrostatic interactions to intermolecular binding DspB within PAH multilayers.

Figure 5.

Retention of DspB within PAH films as confirmed by (A) in situ FTIR-ATR from D2O solution at pD 7.5 on (PAH)5 and (B) AFM measurements of the height of a razor-cut step in dry (PAH)10 films. Dash line indicates dry thickness before DspB loading.

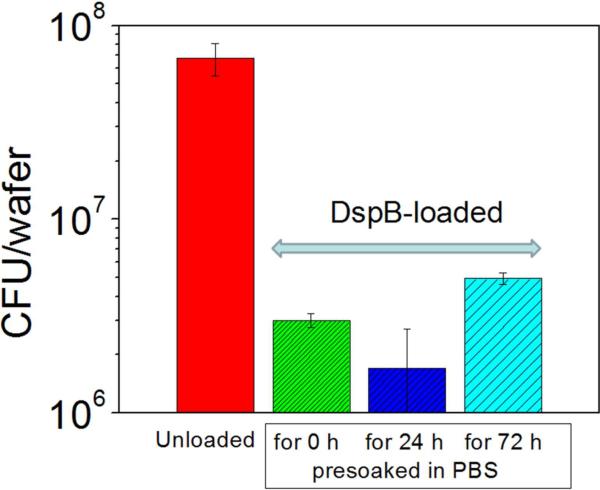

We also tested whether DspB retained within PAH coatings for prolong periods of time retain their biological activity. To that end, DspB-loaded coatings were pre-soaked in PBS buffer for 24 and 72 h, and their biofilm inhibiting activities were then tested using the serial plate transfer method. Figure 6 shows that there is no significant difference in the biofilm-inhibiting capacity between pre-soaked DspB-loaded coatings and freshly used ones.

Figure 6.

Quantitative analysis of 6-h growth of S.epidermidis NJ 9709 at as-synthesized and DspB-loaded (PAH)10 films pre soaked in PBS solution for different time intervals.

Cytocompatibility of DspB-loaded Coatings

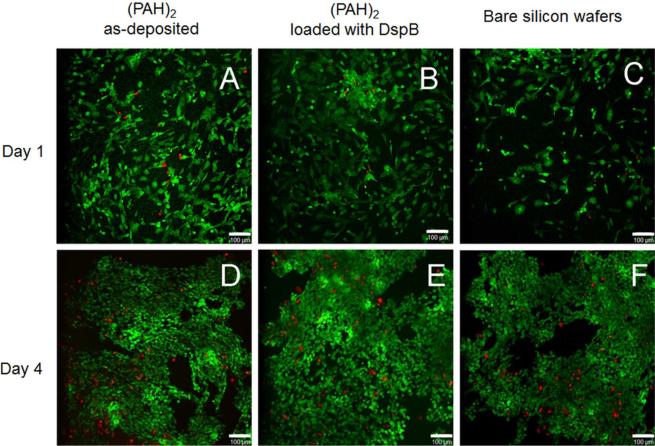

HFOB 1.19 osteoblast cells were used for in vitro cytocompatibility experiments. Figure 7 shows HFOB 1.19 cells visualized by the live-dead staining, at as-synthesized or DspB-loaded (PAH)2 surface coatings, as well as at the surface of bare silicon wafers as a control. HFOB 1.19 cells were capable of adhering and proliferating at both as-deposited (PAH)2 (Figure 7, A and D) as well as at DspB-loaded films (Figure 7, B and E). A large percentage of cells remained intact and alive after 1 day (Figure 7 A–C) and 4 days (Figure 7 D–F) of cell growth. This indicated that DspB is not toxic and suitable for implant surface coating in bone tissue engineering.

Figure 7.

Confocal laser microscopy images of HFOB 1.19 cell attachment and proliferation at as-synthesized (PAH)2 coatings (A and D), DspB-loaded (PAH)2 films (B and E), as well as at the surface of bare silicon wafers (C and F) after 1 day (A, B, C) and 4 days (D, E, F). Representative live/dead images indicate much higher number of live cells (green) as compared to dead cells (red). The scale bar is 100 μm.

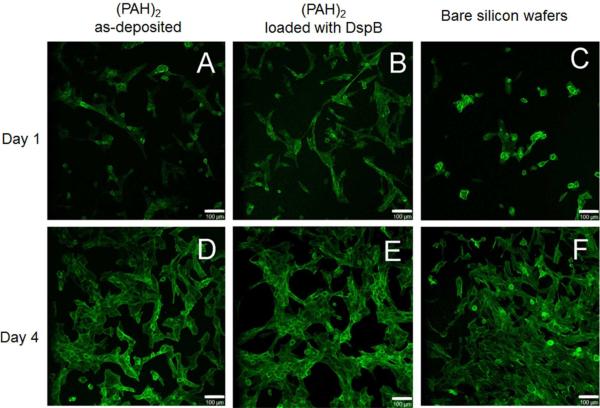

HFOB 1.19 cell cytoskeletal changes were then compared between the three substrate types (Figure 8). In the case of the bare silicon wafers, round cells with low protrusions were observed after 1 day of culture (Figure 8, C), and star-shaped cells with focal contacts as well as spindle-shaped cells were observed; tight cell–cell contacts were also present after 4 days of culture (Figure 8, F). In the case of LbL coatings (both as-deposited and DspB-loaded), cell adhesion and spreading were higher compared to bare silicon wafers, cells were less rounded and displayed a fine cytoskeleton (Figure 8 A and B). After 4 days of culture on PAH-containing samples, cells with an increased F-actin fibers formation indicated better cell spreading (Figure 8, D and E).

Figure 8.

Representative cell morphology micrographs showing F-actin stress fibers after 1 day (A, B, C) and 4 days of cell culture (D, E, F) with as-deposited (PAH)2 films (A and D), DspB-loaded (PAH)2 films (B and E), and with bare silicon wafers (C and F). The scale bar is 100 μm.

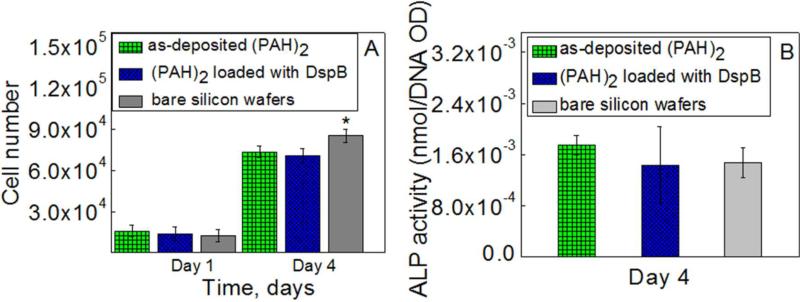

HFOB 1.19 cell attachment and proliferation were evaluated after 1 and 4 days based on the MTS assay (Figure 9). At day 1 of culture, cell adhesion with PAH-containing samples was slightly (but not significantly) higher than that with bare silicon wafer (p > 0.05). The results show an increase of absorption at 490 nm in 4 days indicating cell proliferation at all types of matrices. However, at day 4 time point, a significant (p < 0.05) increase in cell number at a bare silicon wafer occurred as compared to other two samples. Many factors, including surface chemistry and its charge, roughness, stiffness, and wettability54,55,56,57,58 can influence cell adhesion and proliferation at the multilayer films. As bare and hydrogel-coated silicon wafers vary in both surface chemistry and roughness (< 1nm for bare wafers vs. ~3–11 nm for hydrogel coatings), we suggest that both surface chemistry and roughness affect cell attachment and proliferations.

Figure 9.

MTS results (A) and ALP activity (B) for HFOB 1.19 cell at the surfaces of silicon wafers coated with as-deposited (PAH)2, DspB-loaded (PAH)2 films, as well as at the surface of bare silicon wafers. * indicates statistically significant (p<0.05) differences.

To further evaluate effects of the (PAH)2 films on osteoblast cell function, the differentiation capability of osteoblast cells was investigated by the ALP activity test at day 4 (Figure 9, B). The expression of ALP on (PAH)2 films showed no significant difference as compared to that for bare silicon wafers, indicating that (PAH)2 polymer coatings did not have any side effects for lowering osteoblast differentiation and function. Importantly, DspB-loaded hydrogels showed equally high ALP activity as DspB-free PAH films, suggesting that the loaded DspB had no negative effects on osteoblast differentiation and function. Taken together, results in Figures 7–9 confirm that both as-deposited (PAH)2 and DspB-loaded films possessed a good biocompatibility for cell growth.

CONCLUSIONS

A novel strategy for prevention of biofilm formation by cleavage of EPS matrix of PNAG-producing bacterial species by efficient immobilization of DspB within LbL-based coatings has been developed. DspB-loaded LbL-derived coatings demonstrated high efficacy against two strains of S. epidermidis. The coatings did not elute DspB in solution, were highly stable in a wide range of pH, and maintained their antibiofilm function after several-day-long pre-incubation in buffer solutions. Moreover, LbL DspB-containing coatings have shown high biocompatibility with human osteoblast cell line. A combination of anti-biofilm properties with non-toxicity to tissue cells is highly desirable for simultaneous prevention of bacterial infections and maintenance of healthy cell growth on implanted surfaces of biomedical devices. It can be envisioned that a synergistic use of these surface coatings with conventional antibiotics may present a powerful means for designing highly-efficient anti-biofilm and antibacterial coatings for medical implants.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was supported in part by grants from the National Science Foundation (#CBET-0708379 to S.S.) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (#AI82392 to J.B.K.). J.B.K. was also supported in part by grants from the U.S. Department of State Fulbright Commission and the Nord-Pas de Calais Regional Council (France). We thank Narayanan Ramasubbu (New Jersey Dental School) for helpful discussions, and Pierre Hardouin and Thierry Grard (Université du Littoral-Côte d'Opale) for helpful support. The authors are grateful to Neya Shah for her help with sample preparations (Stevens Technogenesis program).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. MTS calibration curve and quantification of S.epidermidis growth (strain 1467) on as-synthesized and DspB-loaded (PAH)8 films using dilution plating. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- (1).Barth E, Myrvik QM, Wagner WW, Gristina AG. Biomaterials. 1989;10:325–328. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(89)90073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Dankert FJ, Hogt AH, Feijen J. CRC Crit. Rev. Biocompat. 1986;2:219–301. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Hall-Stoodley L, Costerton JW, Stoodley P. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004;2:95–108. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Tenover FC. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2006;34:S3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2006.05.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Yeaman MR, Yount NY. Cardiovasc. Res. 2003;55:27–55. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Moellering RC. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2010;37:2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Kaplan JB. J. Dent. Res. 2010;89:205–18. doi: 10.1177/0022034509359403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Hancock REW, Patrzykat A. Curr. Drug Targets. Infectious Disorders. 2002;2:79–83. doi: 10.2174/1568005024605855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Landini P, Antoniani D, Burgess JG, Nijland R. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010;86:813–23. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2468-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Strauss J, Kadilak A, Cronin C, Mello CM, Camesano TA. Colloids Surf., B. 2010;75:156–64. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2009.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Harris LG, Tosatti S, Wieland M, Textor M, Richards RG. Biomaterials. 2004;25:4135–48. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Bower CK, Guire JMC. Microbiology. 1995;61:992–997. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.3.992-997.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Limjaroen P, Ryser E, Lockhart H, Harte B. J. Plast. Film Sheet. 2003;19:95–109. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Darouiche RO, Mansouri MD, Gawande PV, Madhyastha S. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2009;64:88–93. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Donelli G, Francolini I, Romoli D, Guaglianone E, Piozzi A, Ragunath C, Kaplan JB. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007;51:2733–40. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01249-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Haynie SL, Crum GA, Doele BA. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1995;39:301–7. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.2.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Willcox MDP, Hume EBH, Aliwarga Y, Kumar N, Cole N. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008;105:1817–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Chen G, Zhou M, Chen S, Lv G, Yao J. Nanotechnology. 2009;20:465706. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/20/46/465706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Appendini P, Hotchkiss JH. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2001;81:609–616. [Google Scholar]

- (20).da Silva Malheiros P, Daroit DJ, da Silveira NP, Brandelli A. Food Microbiol. 2010;27:175–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Rudra JS, Dave K, Haynie DT. J. Biomater. Sci., Polym. Ed. 2006;17:1301–15. doi: 10.1163/156856206778667433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Etienne O, Gasnier C, Taddei C, Voegel J-C, Aunis D, Schaaf P, Metz-Boutigue M-H, Bolcato-Bellemin A-L, Egles C. Biomaterials. 2005;26:6704–12. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.04.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Guyomard A, Dé E, Jouenne T, Malandain J-J, Muller G, Glinel K. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2008;18:758–765. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Boulmedais F, Frisch B, Etienne O, Lavalle Ph, Picart C, Ogier J, Voegel J-C, Schaaf P,EC. Biomaterials. 2004;25:2003–2011. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Shukla A, Fleming KE, Chuang HF, Chau TM, Loose CR, Stephanopoulos GN, Hammond PT. Biomaterials. 2010;31:2348–57. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Etienne O, Picart C, Taddei C, Haikel Y, Dimarcq JL, Schaaf P, Voegel JC, Ogier JA, Egles C. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004;48:3662–3669. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.10.3662-3669.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Izumrudov VA, Kharlampieva E, Sukhishvili SA. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6:1782–8. doi: 10.1021/bm050096v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Kozlovskaya VA, Kharlampieva EP, Erel-Unal I, Sukhishvili SA. Polym. Sci., Ser. A. 2009;51:719–729. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Pavlukhina S, Lu Y, Patimetha A, Libera M, Sukhishvili S. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11:3448–3456. doi: 10.1021/bm100975w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Lichter JA, Van Vliet KJ, Rubner MF. Macromolecules. 2009;42:8573–8586. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Chuang HF, Smith RC, Hammond PT. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:1660–8. doi: 10.1021/bm800185h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Kropec A, Maira-Litran T, Jefferson KK, Grout M, Cramton SE, Götz F, Donald A, G., Pier GB. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:6868–6876. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6868-6876.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Kaplan JB, Ragunath C, Velliyagounder K, Fine DH. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004;48:2633–2636. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.7.2633-2636.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Itoh Y, Wang X, Hinnebusch BJ, Preston JF, III, Romeo T. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:382–387. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.1.382-387.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Izano EA, Sadovskaya I, Vinogradov E, Mulks MH, Velliyagounder K, Ragunath C, Kher WB, Ramasubbu N, Jabbouri S, Perry MB, Kaplan JB. Microb. Pathog. 2007;43:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Izano EA, Wang H, Ragunath C, Ramasubbu N, Kaplan JB. J. Dent. Res. 2007;86:618–622. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Izano EA, Sadovskaya I, Wang H, Vinogradov E, Ragunath C, Ramasubbu N, Jabbouri S, Perry MB, Kaplan JB. Microb. Pathog. Pathog. 2008;44:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Kaplan JB, Ragunath C, Ramasubbu N, Fine DH. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:4693–4698. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.16.4693-4698.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Pristinski D, Kozlovskaya V, Sukhishvili SA. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A. 2006;23:2639–44. doi: 10.1364/josaa.23.002639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Kaplan JB, Ragunath C, Velliyagounder K, Fine DH. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004;48:2633–2636. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.7.2633-2636.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Mack D, Siemssen N, Laufs R. Infect. Immun. 1992;60:2048–57. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.5.2048-2057.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Gerke C, Kraft A, Süssmuth R, Schweitzer O, Götz F. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:18586–93. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Ramasubbu N, Thomas LM, Ragunath C, Kaplan JB. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;349:475–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.03.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Kozlovskaya V, Sukhishvili SA. Macromolecules. 2006;39:6191–6199. [Google Scholar]

- (45).Tuong SD, Lee H, Kim H. Macromol. Res. 2008;16:373–378. [Google Scholar]

- (46).Tong W, Gao C, Möhwald H. Chem. Mater. 2005;17:4610–4616. [Google Scholar]

- (47).Tong W, Gao C, Möhwald H. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2006;27:2078–2083. doi: 10.1002/marc.200900881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Choi J, Rubner MF. Macromolecules. 2005;38:116–124. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Erol M, Du H, Sukhishvili S. Langmuir. 2006;22:11329–36. doi: 10.1021/la061790e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Wang L, Wang L, S. Z. Soft Matter. 7:4851–4855. [Google Scholar]

- (51).Gaukler JC, Fehling P, Possart W. IOP Conf. Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 2009;5:012002. [Google Scholar]

- (52).Noinville S, Revault M. In: Conformations of proteins adsorbed at liquid-solid interfaces. Déjardin P, editor. Springer; Berlin: 2006. pp. 119–150. [Google Scholar]

- (53).Fischer H, Polikarpov I, Craievich AF. Protein Sci. 2004;13:2825–2828. doi: 10.1110/ps.04688204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Schneider GB, English A, Abraham M, Zaharias R, Stanford C, Keller J. Biomaterials. 2004;25:3023–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.09.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Zhang LF, Yang DJ, Chen HC, Sun R, Xu L, Xiong ZC, Govender T, Xiong CD. Int. J. Pharm. 2008;353:74–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Mehrotra S, Hunley SC, Pawelec KM, Zhang L, Lee I, Baek S, Chan C. Langmuir. 2010;26:12794–802. doi: 10.1021/la101689z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Richert L, Engler AJ, Discher DE, Picart C. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5:1908–16. doi: 10.1021/bm0498023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Lampin M, Warocquier Clérout R, Legris C, Degrange M, Sigot Luizard MF. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1997;36:99–108. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199707)36:1<99::aid-jbm12>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.