Abstract

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) obtained by the ectopic expression of defined transcription factors have tremendous promise and therapeutic potential for regenerative medicine. Many studies have highlighted important differences between iPSCs and embryonic stem cells (ESCs). In this work, we used meta-analysis to compare the global transcriptional profiles of human iPSCs from various cellular origins and induced by different methods. The induction strategy affected the quality of iPSCs in terms of transcriptional signatures. The iPSCs generated by non-integrating methods were closer to ESCs in terms of transcriptional distance than iPSCs generated by integrating methods. Several pathways that could be potentially useful for studying the molecular mechanisms underlying transcription factor-mediated reprogramming leading to pluripotency were also identified. These pathways were mostly associated with the maintenance of ESC pluripotency and cancer regulation. Numerous genes that are up-regulated during the induction of reprogramming also have an important role in the success of human preimplantation embryonic development. Our results indicate that hiPSCs maintain their pluripotency through mechanisms similar to those of hESCs.

Keywords: DNA microarray analysis, embryonic stem cells, gene expression profiling, induced pluripotent stem cells

Introduction

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) are derived from somatic cells by transfecting two pluripotent transcription factors, Oct4 (O) and Sox2 (S), and two proto-oncogenes, c-Myc (M) and Klf4 (K). These four transcription factors globally reset the epigenetic and transcriptional state of fibroblasts into that of pluripotent cells (Takahashi et al., 2007). This technology provides alternative pluripotent cells that closely resemble blastocyst-derived embryonic stem cells (ESCs), which are considered the gold standard for stem cells (Takahashi et al., 2007; Kang et al., 2010). The replacement of ESCs with iPSCs in the field of regenerative medicine is based on the assumption that iPSCs are as potent as ESCs in their ability to differentiate and in their safety for clinical applications (Boue et al., 2010). Mouse iPSCs have the same functional characteristics as mouse ESCs, as shown by their capacity to generate mice in tetraploid complementation experiments (Boland et al., 2009; Kang et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2009). In contrast, this convincing pluripotency test is difficult to execute in human iPSCs (hiPSCs). Genome-wide profiling analysis of gene expression (Ghosh et al., 2010), DNA methylation patterns (Doi et al., 2009) and differentiation properties have detected incomplete reprogramming in hiPSCs. These findings suggest that there are substantial differences between hESCs and hiPSCs.

The advantages and disadvantages of the delivery method for each factor have been discussed elsewhere (Achiwa et al., 2005; Gonzalez et al., 2011). Since the first report on iPSCs produced by retroviral delivery of four factors (OSKM), a substantial number of alternative approaches have been developed to induce pluripotency. In this report, we describe a meta-analysis of gene expression information from multiple independent but related studies (summarized in Table 1). For this, we compared the transcription signatures of hiPSCs generated by different methods and transcriptional factors, with hESCs serving as the gold standard. We also determined the detailed molecular events involved in human cell reprogramming by comparing the transcriptomes of hiPSCs and fibroblasts.

Table 1.

Data for 20 hiPSC lines derived from cells of different origins and different methods of induction. The dataset for each iPSC line includes the donor cells, method of induction and reprogramming factors. The differentially expressed genes were identified by comparing iPSCs and ESCs of the same sex and from the same laboratory. All of the microarray data can be retrieved through the corresponding GEO number. iPSCs-ESCs indicates the number of differentially expressed genes between iPSCs and ESCs, and iPSCs-fibroblasts indicates the number of differentially expressed genes between iPSCs and fibroblasts. K: Klf4, L: Lin28, M: c-Myc, N: Nanog, O: Oct4, S: Sox2.

| Donor cells | iPSCs | Method of induction | Reprogramming factors | ESCs | Sex | GEO number | iPSCs-ESCs | iPSCs-fibroblasts | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPC | iPS 462813 | Episome | OS | HUES6 | F | GSE18618 | 9507 | 7688 | Marchetto et al. (2009) |

| MSC fibroblasts | MSC-derived iPSC line | Retroviral | OSKM | BG01 ESCs | M | 1424 | 15106 | Marchetto et al. (2009) | |

| Foreskin | iPS cells | Episome | OSNL | H13B ESC | M | GSE15148 | 8823 | 9689 | Yu et al. (2009) |

| Foreskin | JT-iPSC | Episome | OSNL | H13 | M | GSE20014 | 1843 | 10673 | Jia et al. (2010) |

| Foreskin | iPSC | Minicircle DNA | OSNL | H13 | M | 7668 | 12092 | Jia et al. (2010) | |

| Fibroblast | hiPSC | Retroviral | OSKMN | Hsf1 p51 | F | GSE22392 | 10048 | 9598 | Chin et al. (2010) |

| Fibroblast | hiPS | Inducible system | OSK | hES_BG01 | M | GSE22499 | 6209 | 15684 | Guenther et al. (2010) |

| Fibroblast | hiPSC | Proteins | OSKMN | H9 hESCs | F | GSE16093 | 1610 | 9104 | Kim et al. (2009) |

| dH1f fibroblast | dH1f-iPS3 | Retroviral | OSKM | H1-OGN hES cells | M | GSE9832 | 8658 | 8614 | Park et al. (2008) |

| dH1cf16 | dH1cf16-iPS5 | Retroviral | OSKM | H1-OGN hES cells | M | 11159 | 7793 | Park et al. (2008) | |

| BJ fibroblast | BJ_iPS | Retroviral | OSKM | H1_ES-1 | M | 14523 | 15424 | Park et al. (2008) | |

| dH1F fibroblast | dH1F_iPS3 | Retroviral | OSKM | H1_ES-1 | M | GSE23583 | 8658 | 15243 | Warren et al. (2010) |

| dH1F fibroblast | dH1F_RiPS | mRNA | OSKM | H1_ES-1 | M | 9125 | 11490 | Warren et al. (2010) | |

| BJ1 fibroblast | BJ1-iPSC 2 | Retroviral | OSKM | BG01 ESCs | M | 2188 | 12499 | Warren et al. (2010) | |

| BJ fibroblast | BJ_RiPS | mRNA | OSKM | H1_ES-1 | M | 10173 | 11072 | Warren et al. (2010) | |

| MRC5 fibroblast | MRC5_RiPS | mRNA | OSKM | H1_ES-1 | M | 10445 | 12092 | Warren et al. (2010) | |

| BJ1 fibroblast | BJ1-iPS1 | Retroviral | OSKM | H1-OGN hES cells | M | GSE24182 | 2920 | 15424 | Loewer et al. (2010) |

| CB_CD133+ | CBiPS_4F | Retroviral | OSKM | ES2_1 | F | GSE16694 | 15414 | 16810 | Giorgetti et al. (2009) |

| CB_CD133+ | CBiPS_2F | Retroviral | OS | ES2_1 | F | 14523 | 8614 | Park et al. (2008) | |

| BJ sample | BJ hIPS | Inducible system | OSKMN | HUES 8 p | M | GSE12390 | 6159 | 15684 | Maherali et al. (2008) |

Materials and Methods

Source of gene expression data

All of the microarray information and individual cell intensity (CEL) files in the HG-U133Plus2 microarray platform (Affymetrix) were obtained online at the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), a public repository for a wide range of high-throughput experimental data. The donor cells and different hiPSC lines are summarized in Table 1.

Microarray analysis

We imported datasets from GEO into GeneSpring GX 11.0 using a guided workflow step to identify potential targets that were both statistically and biologically meaningful. Probe sets with gene-level normalized intensities greater than log (base 2) of 5.0 in a least one sample were excluded from ANOVA. The data were then filtered based on their flag values (P – present and A – absent) to remove probe sets for which the signal intensities for all the treatment groups were in the lowest 20 percentile of all intensity values. ANOVA in conjunction with the Benjamini-Hochberg FDR multiple test correction was used to identify genes that were differentially expressed between different groups. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Gene ontology (GO) annotation and pathway analysis

The functions of up- or down-regulated genes in iPSCs vs. somatic cells were investigated by using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) v 6.7 (Huang et al., 2009) based on gene ontology (GO) (Ashburner et al., 2000) annotations. In addition, groups of genes associated with specific pathways (based on the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes – KEGG) were analyzed together to assess pathway regulation during reprogramming.

Network analysis

We investigated the possible functional associations between the top 484 noticeably significant unregulated genes in iPSCs compared with fibroblasts using the STRING database (STRING score of at least 0.5) (von Mering et al., 2007). Gene networks for which there was high confidence as interacting partners were visualized using MEDUSA (Hooper and Bork, 2005).

Results

Comparative global transcriptomic analysis of iPSCs and ESCs

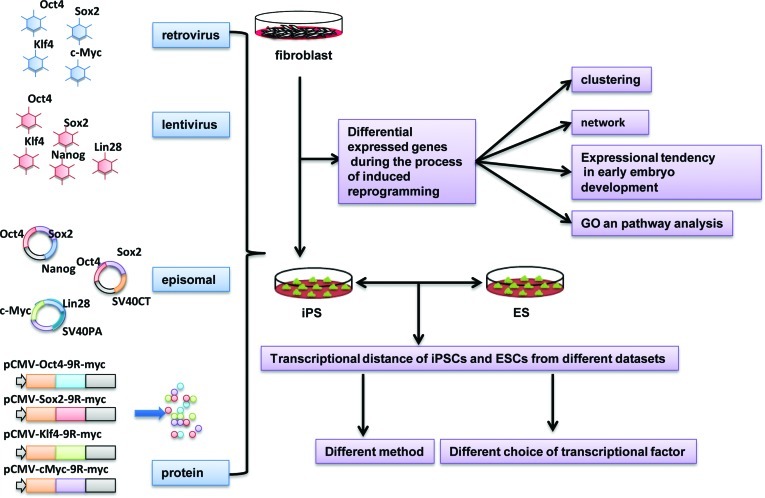

Figure 1 provides a flowchart of the global transcriptomic analysis. Reprogramming methods can be divided into two classes, i.e., those that are integration-free (including synthetic modified mRNA, episomes, proteins and minicircles) and those involving the integration of exogenous transcription factors (lentiviral and retroviral methods and inducible reprogramming systems). Most (75%) of the iPSCs analyzed in this study used fibroblasts as the donor cell type. ANOVA was used to determine the degree of reprogramming within hiPSCs derived using different methods of induction and transcription factors, and to examine the “distance”, i.e., number of differentially expressed genes (based on cut-off criteria of p < 0.05 and a fold-change = 2), among hESCs, hiPSCs and their corresponding donor cells (Figure 1). To eliminate the influence of micro-environmental factors associated with different laboratories and the genetic background of donor cells, the differentially expressed genes were identified by comparing iPSCs and ESCs derived from the same laboratory and donor animals of the same sex (Table 1). Table S1 (Supplementary material) provides a detailed list of the genes that were differentially expressed between iPSCs and ESCs.

Figure 1.

A schematic overview of the approach used in this study. The microarray data for ESCs, iPSCs and their donor cells were obtained from the GEO database. Comparison of the gene expression signature between ESCs and iPSCs showed that the characteristics of the reprogramming varied according to the strategy used. Likewise, comparison of the gene expression signature between iPSCs and original donor cells provided insights into the process of induced reprogramming.

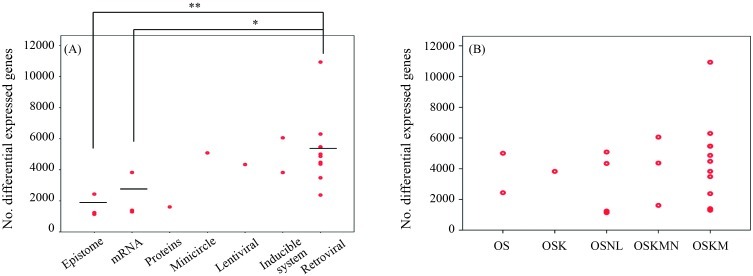

We also analyzed the relationship between the “distance” of iPSCs vs. ESCs and the method used to deliver the transcription factor(s). iPSCs generated by integrating viral vectors (moloney-based retrovirus and HIV-based lentivirus) were not as close to ESC lines as iPSCs generated by non-integrating methods (episomes, synthetic modified mRNA, proteins and minicircle DNA) (Figure 2A). The type of transcription factor used had little impact on the gene expression signature of iPSCs (Figure 2B). No overlapping genes were differentially expressed between hESCs and hiPSCs derived from various reprogramming experiments, i.e., there were no consistent differences in the global gene expression between human ESCs and iPSCs. These findings supported the idea that reprogramming progressed through a series of stochastic events to produce pluripotency.

Figure 2.

The transcriptional signature of iPSCs from different laboratories using different methods of induction and different transcription factors. (A) iPSCs generated by integrating viral vectors were less closely related to ESCs than iPSCs generated by a non-integrating method. (B) The choice of transcription factor (OS, OSK, OSNL, OSKMN and OSKM) did not significantly affect the transcriptional profile of iPSCs. K: Klf4, L: Lin28, M: c-Myc, N: Nanog, O: Oct4, S: Sox2. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.001 compared to the retroviral method.

Functional analysis of significantly altered genes between iPSCs and donor cells

The detailed molecular events involved in reprogramming to produce iPSCs remain largely unknown. To address this issue, we undertook an in-depth analysis of the biological functions of differentially expressed genes in all 20 iPSC lines vs. donor fibroblasts; the selection criteria were again p < 0.05 (Student’s t-test) and at least a two-fold difference in gene expression. Table 1 summarizes the number of differentially expressed genes between the iPSC lines and the original cell lines. Of these, 312 genes up-regulated in each iPSC line were compared with fibroblasts (Table S2). We defined the 312 up-regulated probes as essential for maintaining the pluripotency of hiPSCs (EMP genes). The STRING database was used to visualize all known functional interactions between EMP genes in iPSC lines using the default cutoff suggested by STRING. One hundred and fifty-nine genes in this set (32%) interacted with each other (Figure 3). The functional network of genes with higher expression levels in iPSCs showed a central, highly interconnected area in which common pluripotency regulators such as Pou5f1, Nanog, Lin28, Dnmt3 and Dppa4 were identified. This finding indicated that hiPSCs and hESCs shared a similar core network to maintain pluripotency. The absence of Sox2 in this analysis reflects the fact that Marchetto et al. (2009) used mouse neural stem cells (NSCs), which have a high endogenous expression of Sox2, as the donor cell lines to induce reprogramming. Hence, Sox2 was not included in the 312 genes unregulated in iPSCs. This protein interaction network for pluripotency provides a model for exploring neo-factors that may enhance the induction of reprogramming.

Figure 3.

Predicted stem-cell-specific protein-protein interaction network of genes with higher expression levels in iPSCs compared to somatic cells.

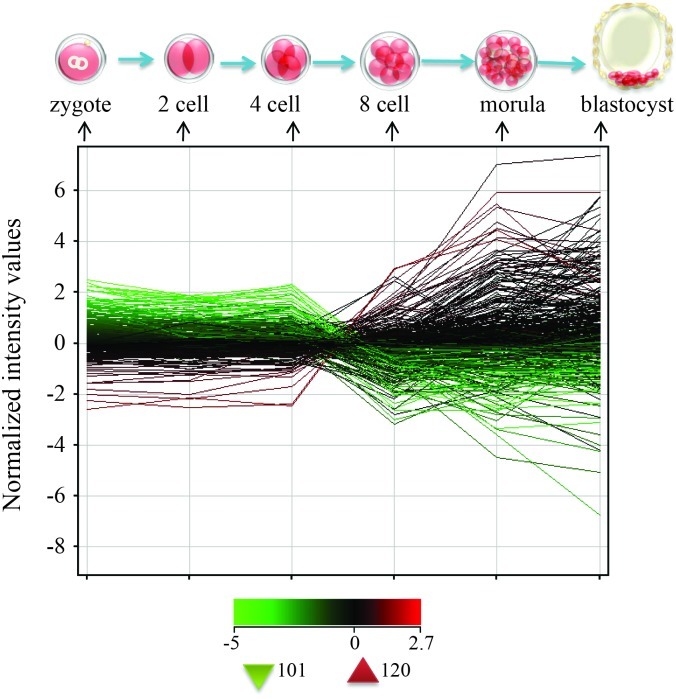

We took advantage of a recently published microarray dataset (Xie et al., 2010) to study the dynamic changes in EMP genes during mammalian preimplantation embryonic development (Table S3). One hundred and twenty EMP genes, including Pou5f1 Dppa4 and Lin28, were up regulated during the transitional phase from the four-cell stage to the eight-cell stage of human early embryonic development, known as the human zygotic genome activation period (Hoffert et al., 1997) (Figure 4). This pluripotent network, which is essential for maintaining the self-renewal of iPSCs, also plays a pivotal role in establishing embryos in vivo. The 101 EMP genes that were down-regulated during the process could contribute to the differentiation of stem cells in vivo and in vitro.

Figure 4.

The gene expression tendency of 312 transcripts (EMP genes) in different stages of human preimplantation embryonic development. One hundred and twenty transcripts were upregulated and 101 transcripts were down-regulated, the later mainly in the four-cell stage to eight-cell stage. Red represents the up regulated expressed genes and green the down-regulated ones.

The functions associated with genes that were significantly altered in reprogramming were examined by analyzing the over-represented annotations and pathways using DAVID, with a cut-off criterion of p < 0.01. The over-represented GO terms focused on “regulation of transcription” and “regulation of cell proliferation” (Table S4). The results of this analysis supported the idea that an increase in proliferation rate was necessary for fully cellular reprogramming (Smith et al., 2010).

We also analyzed whether significant pathways in iPSCs were enriched in significantly altered genes. The results showed that hiPSCs were responsive to the TGF-β signaling pathway that regulates the maintenance of pluripotency, self-renewal and proliferation of hESCs (Table S4). These results demonstrated that hiPSCs reprogrammed from somatic or embryonic cells relied on similar signaling pathways to control their pluripotency.

Discussion

The results described herein show that the overall transcriptional profiles of different human iPSC lines shared a common “signature” with hESCs, although there were certain differences. Notably, the transcriptomes of hiPSCs produced by a delivery method that avoided genomic integration shared a greater gene expression signature with hESCs than did iPSCs produced by a virus-based method. Gene-delivery methods can affect the quality of the resulting iPSCs by influencing the amount, balance, continuity and silencing of transgene expression. Potent oncogenes such as myc apparently have little effect on the transcriptional signature of iPSCs. Our findings provide a basis for selecting the most suitable method for clinical or basic applications and a better understanding of the reprogramming process.

This study also improves our understanding of the mechanisms of cellular reprogramming. The transcriptional network maintains the self-renewal and pluripotency of iPSCs established primarily during preimplantation at the stage of zygote genome activation. Detailed analysis showed that increased proliferation and the up-regulation of genes that drive the cell cycle are necessary events for fibroblast reprogramming. Recent reports have shown that hiPSCs are more tumorigenic than hESCs based on a comparison of protein-coding point mutations (Gore et al., 2011), copy number variations (Hussein et al., 2011) and DNA methylation (Lister et al., 2011). Together, these results stress the link between pluripotency and tumorigenicity. Given that self-renewal is a hallmark of ESCs and cancer cells, the ability to induce tumors during cellular reprogramming implies that there are potential risks involved in the use of iPSCs for regenerative therapy.

In addition, non-coding RNA, including microRNA (miRNA) and large intergenic non-coding (lincRNA), which may represent a distinct layer to fine-tune the transcriptional network of stem cells, has a role in modulating the induction of reprogramming (Judson et al., 2009; Loewer et al., 2010). Significantly, recent work has shown that a single miRNA cluster rapidly reprogrammed mouse and human fibroblasts into iPSCs and totally avoided the use of transcription factors (Anokye-Danso F et al., 2011). The mechanism underlying reprogramming by miRNA differs from that of transcription factor-induced reprogramming in that there is no requirement for protein translation; the former method also targets hundreds of ESC-related mRNAs directly.

In conclusion, we have examined the gene expression profiles of iPSCs obtained by different methods and from donor cell of different of origins. iPSCs produced by non-integrative methods are more closely resembled the fully reprogrammed pluripotent state than did iPSCs obtained by using integrative delivery systems, although the efficiency and kinetics were lower. Some of the results described here may reflect the markedly different circumstances in which they were generated, e.g., the culture conditions, the passage number at which the cells were used and the age of the donor cells. Another limitation in our analysis was that only the initial state (donor cell) and end state (pluripotent cell) of reprogramming were examined.

Further research on each aspect of reprogramming, e.g., the initial transcriptional response to the induction of reprogramming, the epigenetic roadblocks, the partially pluripotent state and the late events leading to pluripotency, is required in order to understand how reprogramming leads to pluripotency. A comprehensive understanding of the events involved in reprogramming a set of iPSCs can only be reached by examining the changes in the corresponding transcriptome (protein coding RNA, microRNA and lincRNA expression), epigenome (genome imprint, X chromosome activation, histone modifications and DNA methylation), metabolome and proteome.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Chinese National Natural Science Foundation (#30871786) and the Major Project of Chinese National Programs for Fundamental Research and Development (“973” plan, 2009CB941002).

Footnotes

Associate Editor: Carlos F.M. Menck

Supplementary Material

The following online material is available for this article:

Table S1 - Genes differentially expressed between iPSC lines and their original donor cells.

Table S2 – A detailed list of genes dynamically expressed during early embryonic development.

Table S3 - The over-represented classification of GO annotations for differentially expressed genes in iPSCs and ESCs compared with donor cells.

Table S4 - The over-represented classification of pathways for 1942 differentially expressed genes in iPSCs compared with donor cells.

This material is available as part of the online article from http://www.scielo.br/gmb.

References

- Achiwa Y, Hasegawa K, Udagawa Y. Molecular mechanism of ursolic acid induced apoptosis in poorly differentiated endometrial cancer HEC108 cells. Oncol Rep. 2005;14:507–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anokye-Danso F, Trivedi CM, Juhr D, Gupta M, Cui Z, Tian Y, Zhang Y, Yang W, Gruber PJ, Epstein JA, et al. Highly efficient miRNA-mediated reprogramming of mouse and human somatic cells to pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:376–388. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland MJ, Hazen JL, Nazor KL, Rodriguez AR, Gifford W, Martin G, Kupriyanov S, Baldwin KK. Adult mice generated from induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2009;461:91–94. doi: 10.1038/nature08310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boue S, Paramonov I, Barrero MJ, Belmonte JCI. Analysis of human and mouse reprogramming of somatic cells to induced pluripotent stem cells. What is in the plate? PLoS One. 2010;5:e12664. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin MH, Pellegrini M, Plath K, Lowry WE. Molecular analyses of human induced pluripotent stem cells and embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi A, Park IH, Wen B, Murakami P, Aryee MJ, Irizarry R, Herb B, Ladd-Acosta C, Rho J, Loewer S, et al. Differential methylation of tissue- and cancer-specific CpG island shores distinguishes human induced pluripotent stem cells, embryonic stem cells and fibroblasts. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1350–1353. doi: 10.1038/ng.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh Z, Wilson KD, Wu Y, Hu SJ, Quertermous T, Wu JC. Persistent donor cell gene expression among human induced pluripotent stem cells contributes to differences with human embryonic stem cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez F, Boue S, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Methods for making induced pluripotent stem cells: Reprogramming a la carte. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:231–242. doi: 10.1038/nrg2937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore A, Li Z, Fung HL, Young JE, Agarwal S, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Canto I, Giorgetti A, Israel MA, Kiskinis E, et al. Somatic coding mutations in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;471:63–67. doi: 10.1038/nature09805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgetti A, Montserrat N, Aasen T, Gonzalez F, Rodriguez-Piza I, Vassena R, Raya A, Boue S, Barrero MJ, Corbella BA, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human cord blood using OCT4 and SOX2. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:353–357. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther MG, Frampton GM, Soldner F, Hockemeyer D, Mitalipova M, Jaenisch R, Young RA. Chromatin structure and gene expression programs of human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffert KA, Anderson GB, Wildt DE, Roth TL. Transition from maternal to embryonic control of development in IVM/IVF domestic cat embryos. Mol Reprod Dev. 1997;48:208–215. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199710)48:2<208::AID-MRD8>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper SD, Bork P. Medusa: A simple tool for interaction graph analysis. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:4432–4433. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein SM, Batada NN, Vuoristo S, Ching RW, Autio R, Narva E, Ng S, Sourour M, Hamalainen R, Olsson C, et al. Copy number variation and selection during reprogramming to pluripotency. Nature. 2011;471:58–62. doi: 10.1038/nature09871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia F, Wilson KD, Sun N, Gupta DM, Huang M, Li Z, Panetta NJ, Chen ZY, Robbins RC, Kay MA, et al. A nonviral minicircle vector for deriving human iPS cells. Nat Methods. 2010;7:197–199. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judson RL, Babiarz JE, Venere M, Blelloch R. Embryonic stem cell-specific microRNAs promote induced pluripotency. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:459–461. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang L, Wang J, Zhang Y, Kou Z, Gao S. iPS cells can support full-term development of tetraploid blastocyst-complemented embryos. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:135–138. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang L, Kou ZH, Zhang Y, Gao SR. Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) - A new era of reprogramming. J Genet Genomics. 2010;37:415–421. doi: 10.1016/S1673-8527(09)60060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Kim CH, Moon JI, Chung YG, Chang MY, Han BS, Ko S, Yang E, Cha KY, Lanza R, et al. Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells by direct delivery of reprogramming proteins. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:472–476. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister R, Pelizzola M, Kida YS, Hawkins RD, Nery JR, Hon G, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, O’Malley R, Castanon R, Klugman S, et al. Hotspots of aberrant epigenomic reprogramming in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;471:68–73. doi: 10.1038/nature09798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewer S, Cabili MN, Guttman M, Loh YH, Thomas K, Park IH, Garber M, Curran M, Onder T, Agarwal S, et al. Large intergenic non-coding RNA-RoR modulates reprogramming of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Genet. 2010;42:1113–1117. doi: 10.1038/ng.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetto MC, Yeo GW, Kainohana O, Marsala M, Gage FH, Muotri AR. Transcriptional signature and memory retention of human-induced pluripotent stem cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maherali N, Ahfeldt T, Rigamonti A, Utikal J, Cowan C, Hochedlinger K. A high-efficiency system for the generation and study of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:340–345. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park IH, Zhao R, West JA, Yabuuchi A, Huo H, Ince TA, Lerou PH, Lensch MW, Daley GQ. Reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotency with defined factors. Nature. 2008;451:141–146. doi: 10.1038/nature06534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ZD, Nachman I, Regev A, Meissner A. Dynamic single-cell imaging of direct reprogramming reveals an early specifying event. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:521–526. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Mering C, Jensen LJ, Kuhn M, Chaffron S, Doerks T, Kruger B, Snel B, Bork P. STRING 7 - Recent developments in the integration and prediction of protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D358–362. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren L, Manos PD, Ahfeldt T, Loh YH, Li H, Lau F, Ebina W, Mandal PK, Smith ZD, Meissner A, et al. Highly efficient reprogramming to pluripotency and directed differentiation of human cells with synthetic modified mRNA. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:618–630. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie D, Chen CC, Ptaszek LM, Xiao S, Cao X, Fang F, Ng HH, Lewin HA, Cowan C, Zhong S. Rewirable gene regulatory networks in the preimplantation embryonic development of three mammalian species. Genome Res. 2010;20:804–815. doi: 10.1101/gr.100594.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu JY, Hu KJ, Smuga-Otto K, Tian SL, Stewart R, Slukvin II, Thomson JA. Human induced pluripotent stem cells free of vector and transgene sequences. Science. 2009;324:797–801. doi: 10.1126/science.1172482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao XY, Li W, Lv Z, Liu L, Tong M, Hai T, Hao J, Guo CL, Ma QW, Wang L, et al. iPS cells produce viable mice through tetraploid complementation. Nature. 2009;461:U86–U88. doi: 10.1038/nature08267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Internet Resources

- Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 - Genes differentially expressed between iPSC lines and their original donor cells.

Table S2 – A detailed list of genes dynamically expressed during early embryonic development.

Table S3 - The over-represented classification of GO annotations for differentially expressed genes in iPSCs and ESCs compared with donor cells.

Table S4 - The over-represented classification of pathways for 1942 differentially expressed genes in iPSCs compared with donor cells.