Abstract

Cognitive dysfunction is a major health problem in the 21st century, and many neuropsychiatric disorders and neurodegenerative disorders, such as schizophrenia, depression, Alzheimer's Disease dementia, cerebrovascular impairment, seizure disorders, head injury and Parkinsonism, can be severly functionally debilitating in nature. In course of time, a number of neurotransmitters and signaling molecules have been identified which have been considered as therapeutic targets. Conventional as well newer molecules have been tried against these targets. Phytochemicals from medicinal plants play a vital role in maintaining the brain's chemical balance by influencing the function of receptors for the major inhibitory neurotransmitters. In traditional practice of medicine, several plants have been reported to treat cognitive disorders. In this review paper, we attempt to throw some light on the use of medicinal herbs to treat cognitive disorders. In this review, we briefly deal with some medicinal herbs focusing on their neuroprotective active phytochemical substances like fatty acids, phenols, alkaloids, flavonoids, saponins, terpenes etc. The resistance of neurons to various stressors by activating specific signal transduction pathways and transcription factors are also discussed. It was observed in the review that a number of herbal medicines used in Ayurvedic practices as well Chinese medicines contain multiple compounds and phytochemicals that may have a neuroprotective effect which may prove beneficial in different neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders. Though the presence of receptors or transporters for polyphenols or other phytochemicals of the herbal preparations, in brain tissues remains to be ascertained, compounds with multiple targets appear as a potential and promising class of therapeutics for the treatment of diseases with a multifactorial etiology.

Keywords: Antioxidants, medicinal plants, neuroprotective herbs, nootropics, phytochemicals

INTRODUCTION

The brain can be described as the most complex structure in the human body. It is made up of neurons and neuroglia, the neurons being responsible for sending and receiving nerve impulses or signals. The microglia and astrocytes are essential for ensuring proper functioning of neurons. They are quick to intervene when neurons become injured or stressed. As they are sentinels of neuron well-being, pathological impairment of microglia or astrocytes could have devastating consequences for brain function. It is assumed that neuroglial activation is largely determined by neuronal signals.[1] Acute injury causes neurons to generate signals that inform neuroglia about the neuronal status. Depending on how severe a degree of neuronal injury, neuroglia will either nurse the injured neurons into regeneration or kill them if they are not viable. These types of neuroglial responses are considered to represent normal physiological and neuroprotective responses. In contrast, some processes that are chronic in nature persistently activate neuroglia eventually causing a failure in their physiological ability to maintain homeostasis. This could have detrimental consequences and may lead to bystander damage due to neuroglial dysfunction.

Neurodegeneration is a process involved in both neuropathological conditions and brain ageing. It is known that brain pathology in the form of cerebrovascular and neurodegenerative disease is a leading cause of death all over the world, with an incidence of about 2/1000 and an 8% total death rate.[2] Cognitive dysfunction, is a major health problem in the 21st century, and many neuropsychiatric disorders and neurodegenerative disorders, such as schizophrenia, depression, Alzheimer's Disease (AD) dementia, cerebrovascular impairment, seizure disorders, head injury, Parkinsonism etc can be severly functionally debilitating in nature..[3] Neuroprotection refers to the strategies and relative mechanisms able to defend the central nervous system (CNS) against neuronal injury due to both acute (e.g. stroke or trauma) and chronic neurodegenerative disorders (e.g. Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease).[4] Moreover, stroke and dementia are a source of high individual and family suffering mainly because of the lack of efficient therapeutic alternatives. The latter motivates research efforts to identify the mechanisms of neuronal death and to discover new compounds to control them.

The past decade has also witnessed an intense interest in herbal medicines in which phytochemical constituents can have long-term health promoting or medicinal qualities. In contrast, many medicinal plants exert specific medicinal actions without serving a nutritional role in the human diet and may be used in response to specific health problems over short- or long-term intervals. Phytochemicals present in vegetables and fruits are believed to reduce the risk of several major diseases including cardiovascular diseases, cancers as well as neurodegenerative disorders. Therefore people who consume higher vegetables and fruits may be at reduced risk for some of diseases caused by neuronal dysfunction.[5,6]

Herbal medicine has long been used to treat neural symptoms. Although the precise mechanisms of action of herbal drugs have yet to be determined, some of them have been shown to exert anti-infl ammatory and/or antioxidant effects in a variety of peripheral systems. Now, as increasing evidence indicates that neuroglia-derived chronic inflammatory responses play a pathological role in the central nervous system, anti-inflammatory herbal medicine and its constituents are being proved to be a potent neuroprotector against various brain pathologies. Structural diversity of medicinal herbs makes them a valuable source of novel lead compounds against therapeutic targets that are newly discovered by genomics, proteomics, and high-throughput screening. This review will highlight the importance of phytochemicals on neuroprotective function and other related disorders, in particular their mechanism of action and therapeutic potential.[7]

Nootropics

Nootropics is a term used by proponents of smart drugs to describe medical drugs and nutritional supplements that have a positive effect on brain function; “nootropic” is derived from Greek and means acting on the mind.[8] A number of pharmaceutical compounds are in the market which have been used for their neuroprotective property. Drugs to improve neurofunction generally work by altering the balance of particular chemicals (neurotransmitters) in the brain. Some acts by selective enhancement of cerebral blood flow, cerebral oxygen usage metabolic rate and cerebral glucose metabolic rate in chronic impaired human brain function i.e., multi-infarct (stroke) dementia, senile dementia of the Alzheimer type and pseudo dementia, ischaemic cerebral (poor brain blood flow) infarcts. Number of medicines are derived from the medicinal plants and have shown memory enhancing properties by virtue of their bioactive phytochemical constituents. One of the mechanisms suggested to dementia is decreased cholinergic activity in brain. Therefore, cholinergic drugs (of plant origin) like: Muscarinic agonists (e.g. arecoline, pilocarpine etc.), nicotinic agonists (e.g. nicotine) and cholinesterase inhibitors (e.g. huperzine) can be employed for improving memory.[8] Some other classes of drugs used in dementia are: Stimulants or nootropics (e.g. piracetam, amphetamine), putative cerebral vasodilators (e.g. ergot alkaloids, papavarine), calcium channel blocker (e.g. nimodipine).

Neuroprotective herbs

The ‘Green’ movement in Western society has changed attitudes in the general population who now conceive naturally derived substances and extracts as being inherently safer and more desirable than synthetic chemical products, with the net effect of increase in sales of herbal preparations.[9,10] About 80% of people in the developing countries rely on phytomedicine for primary healthcare for man and livestock.[11] In traditional practices of medicine, numerous plants have been used to treat cognitive disorders, including neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease (AD) and other memory related disorders. Herbal products contain complicated mixtures of organic chemicals, which may include fatty acids, sterols, alkaloids, flavonoids, glycosides, saponins, tannins, terpenes and so forth. Proponents of herbal medicines describe a plant's therapeutic value as coming from the synergistic effects of the various components of the plants, in contrast to the individual chemicals of conventional medicines isolated by pharmacologists, therefore it is believed that traditional medicines are effective, with few or no side-effects. Roughly one-quarter to one-half of current pharmaceuticals originally were procured from plants.

Identification and characterization of new medicinal plants to cure neurodegenerative diseases and brain injuries resulting from stroke is the major and increasing scientific interest in recent years. There are more than 120 traditional medicines that are being used for the therapy of Central Nervous System (CNS) disorders in Asian countries.[4] In the Indian system of medicine the following medicinal plants have shownpromising activity in neuropsychopharmacology: Allium sativum, Bacopa monnierae, Centella asiatica, Celastrus paniculatus, Nicotiana tabaccum, Withania somnifera, Ricinus communis, Salvia officinalis, Ginkgo biloba, Huperiza serrata, Angelica sinensis, Uncaria tomentosa, Hypericum perforatum, Physostigma venosum, Acorus calmus, Curcuma longa, Terminalia chebula, Crocus sativus, Enhydra fluctuans, Valeriana wallichii, Glycyrrhiza glabra etc. In Chinese medicine, numerous plants have been used to treat stroke, and some of the them are: Ledebouriella divaricata, Scutellaria baicalensis, Angelica pubescens, Morus alba, Salvia miltiorrhiza, Uncaria rhynchophylla, and Ligusticum chuanxiong.[12] The neuroprotective natures of some of the traditional plants being used from the ages are given below.

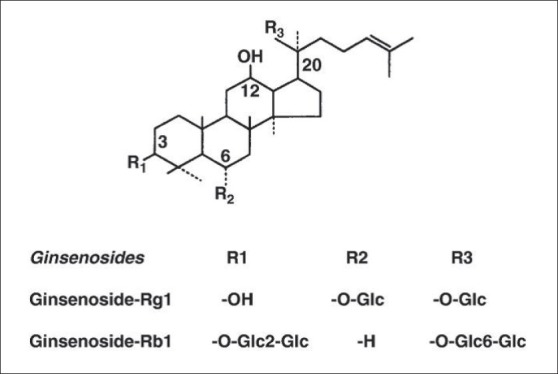

Ginkgo biloba L

Ginkgo Biloba (Ginkgoaceae) is also known as maiden hair tree, kew tree, ginkyo, yinhsing and is indigenous to East Asia. It has been used in traditional Chinese medicine for the improvement of memory loss associated with abnormalities in the blood circulation.[13] The herb shows memory enhancing action by increase the supply of oxygen, and helps the body to eliminate free radicals thereby improving memory. Phytoconstituents include terpenoids bilobolide, ginkgolides, flavanoids, steroids (sitosterol and stigmasterol) and organic acids (ascorbic, benzoic shikimic and vanillic acid). Leaf extract contains 24% of flavonoids and 6% of terpenic lactones, giving this extract its unique polyvalent pharmacological action. The flavonoid fraction is mainly composed of three flavonols, quercetin, keampferol and isorhamnetin, whereas terpenic derivatives are represented by diterpenic lactones, the ginkgolides A, B, C, J and M [Figure 1], and a sesquiterpenic trilactone, the bilobalide.[13] Bilobalide and ginkgolides present in Ginkgo biloba have been classified as nootropic agents.[4]

Figure 1.

Ginsenoside Rb1 and Rg1 from Ginkgo Biloba

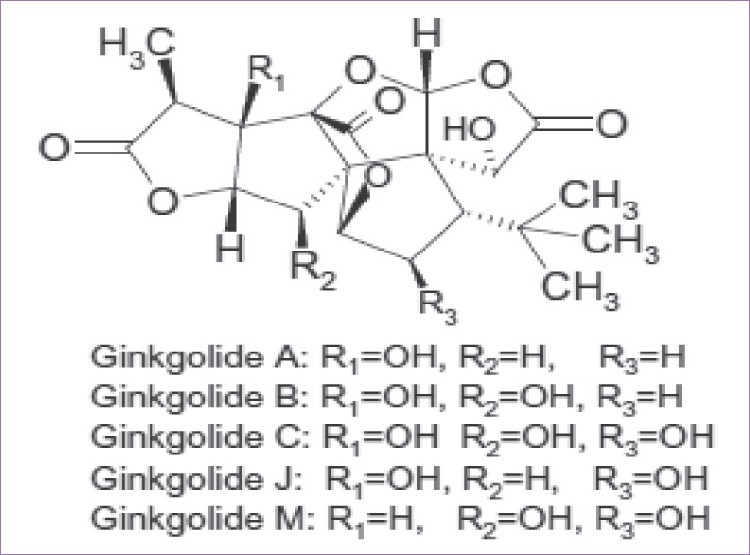

Panax ginseng

Ginseng refers to a group of several species within the Panax (from the Greek pan = all, and akèia = cure) genus and the family of Araliaceae growing in north-eastern Asia, with P. ginseng, or Asian ginseng, among the most commonly used species also in Korean traditional medicine and Kampo (Japanese traditional medicine). It is one of the most widely used herbs in Chinese medicine for boosting energy. It is being used as anti-ageing herb and also employed since thousands of years as a tonic and revitalizing agent.[14] Ginseng root, characterized by the presence of ginsenosides [Figure 2] (triterpenic saponin complexes), is considered an adaptogenic herb, able to increase the body's resistance to stress, trauma, anxiety and fatigue by modulating the immune function. Ginseng may provide protection against neurodegeneration by multiple mechanisms.

Figure 2.

Ginkgolides A, B, C, J and M from Panax ginseng

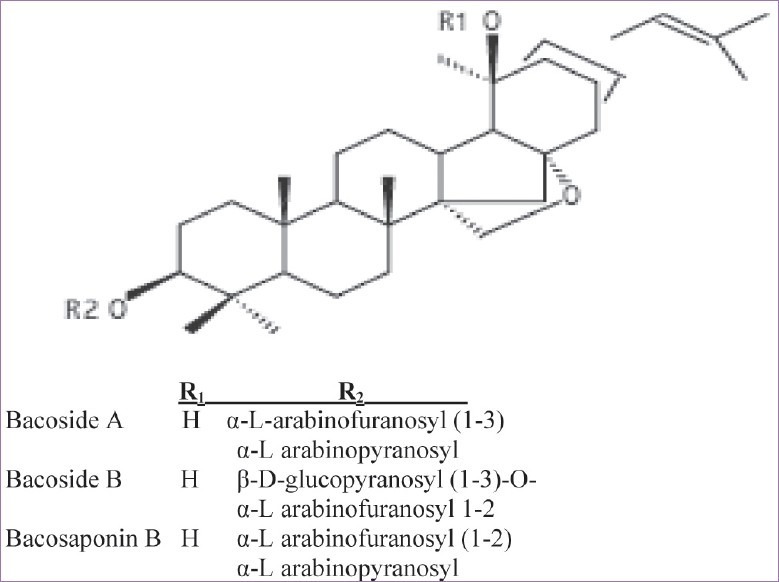

Bacopa monniera

“Brahmi,” has been used in the Ayurvedic system of medicine for centuries. Traditionally, it was used as a brain tonic to enhance memory development, learning and to provide relief to patients with anxiety or epileptic disorders.[15] Bacopa include many active constituents includes the alkaloids brahmine and herpestine, saponins d-mannitol and hersaponin and monnierin. Other active constituents have since been identified, including betulic acid, stigmastarol, beta-sitosterol, as well as numerous bacosides and bacopasaponins. The constituents responsible for Bacopa's cognitive effects are bacosides A and B [Figure 3].[16] The bacosides aid in repair of damaged neurons by enhancing kinase activity, neuronal synthesis, and restoration of synaptic activity, and ultimately nerve impulse transmission.[17]

Figure 3.

Bacoside A, B and Bacosaponin from Bacopa monniera

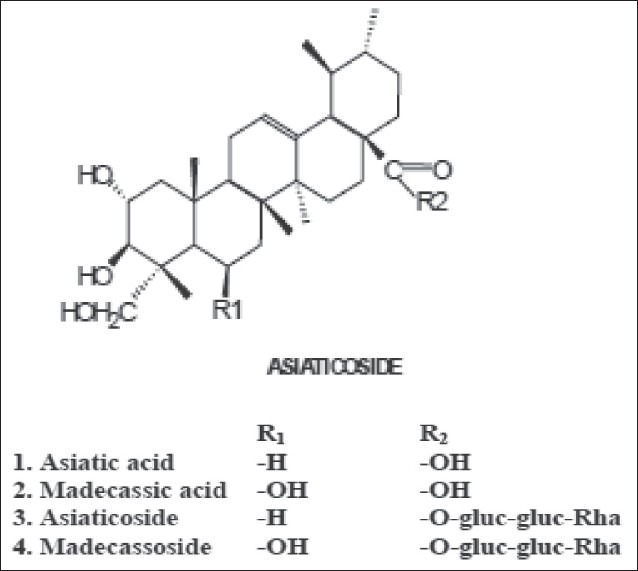

Centella asiatica

Centella asiatica (CA) L. Urban (syn. Hydrocotyle asiatica L.) belonging to family Apiaceae (Umbelliferae) is a psychoactive medicinal plant being used from centuries in Ayurvedic system of medicine as a medhya rasayna.[18,19] It has been shown to decrease the oxidative stress parameters. Major bioactive compounds of this plant contain highly variable triterpenoid saponins, including asiaticoside, oxyasiaticoside, centelloside, brahmoside, brahminoside, thankunoside, isothankunoside and related sapogenins. It also contains triterpenoid acids viz. asiatic acid, madecassic acid [Figure 4], brahmic acid, isobrahmic acid and betulic acid etc. However, its exact mechanism of action in the treatment and management of neurodisorders has not been fully understood.[18]

Figure 4.

Asiatic acid, madecassic acid, asiaticoside and madecassoside from Centella asiatica

Phytochemical based antioxidants in neuroregeneration

The brain has a large potential oxidative capacity but a limited ability to counteract oxidative stress.[20] Oxidative stress has been implicated in mechanisms leading to neuronal cell injury in various pathological states of the brain, including neurodegenerative disorders. Although the brain accounts for less than 2% of the body weight, it consumes about 20% of the oxygen available through respiration. Therefore, because of its high oxygen demand, the brain is the most susceptible organ to oxidative damage.[20] Phytopharmaceuticals are gaining importance in modern medicine as well as in traditional system of medicine owing to their therapeutic potential. Novel antioxidants may offer an effective and safe means of bolstering body's defense against free radicals. Central nervous system cells are able to combat oxidative stress using some limited resources like, vitamins, bioactive molecules, lipoic acid, antioxidant enzymes and redox sensitive protein transcriptional factors. However, this defense system can be activated/modulated by nutritional antioxidants such as polyphenols, flavonids, terpenoids, fatty acids etc. Plant derived alternative antioxidants (AOX) are regarded as effective in controlling the effects of oxidative damage, and hence have had influence in what people eat and drink.[21,22] There is ample scientific and empirical evidence supporting the use of antioxidants for the control of neurodegenerative disorders. As the focus of medicine shifts from treatment of manifest disease to prevention, herbal medicine (with its four pillars of phytochemistry, phytopharmacy, phytopharmacology and phytotherapy) is coming into consideration, being a renaissance of age-old human tradition.

Phytochemical based antioxidants may have neuroprotective (preventing apoptosis) and neuroregenerative roles,[23] by reducing or reversing cellular damage and by slowing progression of neuronal cell loss. In nature, AOX are grouped as endogenous or exogenous. The endogenous group includes enzymes (and trace elements part-of) like superoxidase dismutase (zinc, manganese, and copper), glutathione peroxide (selenium) and catalase, and proteins like albumin, transferrin, ceruloplasmin, metallothionein and haptoglobin. The most important exogenous AOX are dietary phytochemicals (such as polyphenols, quinones, flavonoids, catechins, coumarins, terpenoids) and the smaller molecules like ascorbic acid (Vitamin C), alpha-tocopherol (Vitamin E), beta-carotene vitamin-E, and supplements.[24,25] Though their mode of action is not yet completely elucidated, and clinical trials involving them are still relatively scarce, AOX offer a promising approach in the control or slowing down progression of neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, Huntington's disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke.[25,26]

Phytochemicals in neuroprotection

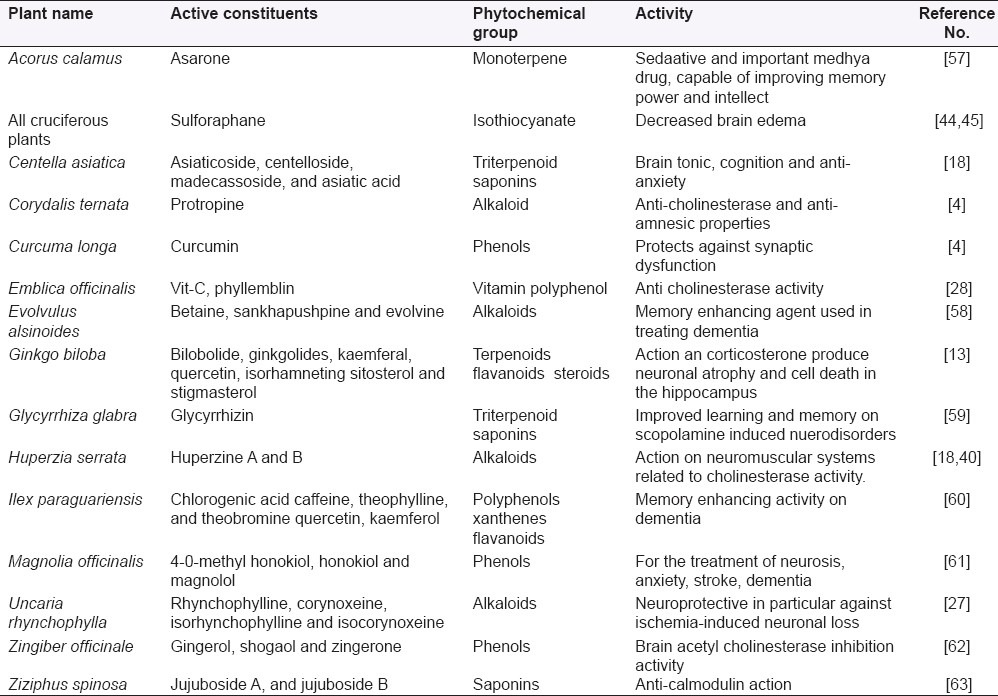

There has been considerable public and scientific interest in the use of phytoconstituents for neuroprotection or to prevent neurodegenerative diseases. Many phytochemicals have been shown to exert neuroprotective actions in animal and cell culture models of neurological disorders. For example, a chalcone (safflor yellow B) can protect neurons against ischemic brain injury and piceatannol can protect cultured neurons against Aβ-induced death. Epidemiological studies of human populations, and experiments in animal models of neurodegenerative disorders, have provided evidence that phytochemicals in fruits and vegetables can protect the nervous system against disease.[27,28] The vast majority of studies on health benefits of phytochemicals have focused on the fact that many of the active chemicals possess antioxidant activity. Neuroprotective effects of various phytochemicals are associated with reduced levels of oxidative stress. For example, resveratrol, quercetin and catechins reduced oxidative stress and protected cultured hippocampal neurons against nitric-oxide-mediated cell death.[24] Some of the neuroprotective herbs with their major bioactive compound and mode of action was shown in Table 1. Hundreds of articles have been published reporting neuroprotective effects of compounds in natural products, including a-tocopherol, lycopene, resveratrol, ginkgo biloba and ginsenosides.[29] Some of important phytochemicals in neuroprotection have given below:

Table 1.

Nootropic herbs with their active constituents’ that help in neuroprotection

PHENOLS

Phenolic compounds in foods have attracted great interest since the 1990s due to growing evidence of their beneficial effect on human health. Evidence from in vitro, in vivo studies and clinical trials has shown that polyphenols from apple, grape, and citrus fruit juices possess a stronger neuroprotection than antioxidant vitamins. The phenolic compounds (catechins and epicatechins) of green tea are capable to protect neurons against a range of oxidative and metabolic insults, which includes protection of dopaminergic neurons from damage induced by 6-hydroxydopamine in a rat model of Parkinson's disease;[30] protection of retinal neurons against ischemia reperfusion injury;[31] and reduction of mutant huntingtin misfolding and neurotoxicity in Huntington's disease models.[32]

Catechins are polyphenols exhibiting neuroprotective activities that are mediated, in part, by activation of protein kinase C (PKC) and transcription factors that induce the expression of cell-survival genes.[33] Catechins have been suggested to suppress the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease, and to protect neurons against the processes of Alzheimer's disease. Studies have shown that catechins and their metabolites activate multiple signaling pathways that can exert cell-survival and anti-inflammatory actions, including altering the expression of pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic proteins, and upregulating antioxidant defenses.[34]

FLAVONOIDS

Recently, there has been intense interest in the potential of flavonoids to modulate neuronal function and prevent age-related neurodegeneration. Dietary intervention studies in several mammalian species, including humans, using flavonoid rich plant or food extracts have indicated an ability to improve memory and learning, by protecting vulnerable neurons, enhancing existing neuronal function or by stimulating neuronal regeneration. Individual flavonoids such as the citrus flavanone tangeretin, have been observed to maintain nigro-striatal integrity and functionality following lesioning with 6- hydroxydopamine, suggesting that it may serve as a potential neuroprotective agent against the underlying pathology associated with Parkinson's disease.[35] In order for flavonoids to access the brain, they must first cross the blood brain barrier (BBB), which controls entry of xenobiotics into the brain.[32] Flavanones such as hesperetin, naringenin and their in vivo metabolites, along with some dietary anthocyanins, cyanidin-3-rutinoside and pelargonidin-3-glucoside, have been shown to traverse the BBB in relevant in vitro and in situ models.[35,36] Anthocyanins can possibly cross the monolayer in blood-brain barrier models in vitro.

ALKALOIDS

Alkaloids are a vast group of natural products containing nitrogen, carbon, hydrogen and usually oxygen. Alkaloids may affect the CNS, including nerve cells of the brain and spinal cord which control many direct body functions and the behavior. They may also affect the autonomic nervous system, which includes the regulation of internal organs, heartbeat, circulation and breathing. Indole alkaloids contain the indole carbon-nitrogen ring which is also found in the fungal alkaloids ergine and psilocybin and the mind-altering drug Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). These alkaloids may interfere or compete with the action of serotonin in the brain.[37] Ergot alkaloids have marked effects on blood flow, which was originally thought to be the main mechanism of action. Tropane alkaloids like atropine, hyoscyamine and scopolamine from Datura affect the spinal cord and CNS. Iso-quinoline alkaloid such as morphine, which is isolated from Papaver somniferum (opium poppy) is a highly potent analgesic and a narcotic drug. Morphin's mechanism of action is strong binding to the μ-opioid receptor (MOR) in the central nervous system, resulting in an increase of Gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) in the synapses of the brain.[38] Vinpocetine is an alkaloid obtained from Vinca minor, and is a highly potent vasodilator. Clinical studies of vinpocetine report selective enhancement of cerebral blood flow and metabolism, including enhanced glucose uptake, which may protect against the effects of hypoxia and ischaemia.[38] Galantamine is a tertiary alkaloid, belonging to the phenanthrene chemical class, which occurs naturally in the daffodil (Narcissus tazetta), snowdrop (Galanthus nivalis) and the snowflake (Leucojum aestivum). The drug also belongs to a class of drugs called cholinesterase inhibitors and is capable of stimulating nicotinic receptors which further enhance cognition and memory.[38]

TERPENOIDS AND SAPONINS

Many plant-derived essential oils, such as wormwood, have been known for over a century to have convulsant properties. The rhizome of valerian (Valerian officinalis) contains two pharmacologically active ingredients: Valepotriates and sesquiterpenes (valerenic acid and acetoxyvalerenic acid). Sedating effects of the active agents have been demonstrated in mice. Valerian crude extract, however, is noted to have GABA(B) receptor binding properties and GABA uptake inhibition in rat synaptosomes.[39] Huperzine A, a sesquiterpene alkaloid purified from the Chinese medicinal herb Huperia serrata, exhibits a broad range of neuroprotective actions. Huperzine A ameliorated learning and memory impairments, and improved spatial working memory. In Centella asiatica L. triterpenoid, brahminoside[40] and monoterpenes, β-pinene and γ-terpinene[18] are active chemical substances in revitalizing and strengthening the nervous function.

FATTY ACIDS

Consuming monounsaturated fatty acids and Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) was shown to slow cognitive decline in animals and in humans. Most studies have focused on the n23 and n26 (omega-3 and omega- 6) PUFAs found in nuts, such as walnuts contain the monounsaturated fatty acid oleic acid (8:1) and the n26 and n23 PUFAs linoleic acid (LA) and a-linolenic acid (ALA).[41] Numerous studies have shown that consuming diets deficient in n23 fatty acids will impair cognitive functioning.[42] The structure of neurons is critical to their function as the cells must maintain appropriate electrical gradients across the membrane, with normal anchor receptors and the ion channels in proper position to communicate with other cells, and be able to release and reabsorb unmetabolized neurotransmitters. These properties depend on the fatty acid composition of the neuronal membrane.[43] The fatty acid composition of neuronal membranes declines during aging, but dietary supplementation with essential fatty acids was shown to improve membrane fluidity and PUFA content. In addition to affecting membrane biophysical properties, PUFAs in the form of phospholipids in neuronal membranes can also directly participate in signaling cascades to promote neuronal function, synaptic plasticity, and neuroprotection.[43]

Other phytochemicals of neuroprotective importance

Sulforaphane

Sulforaphane is an isothiocyanate present in high amounts in broccoli, brussels sprouts and other cruciferous vegetables. Several studies have reported neuroprotective effects of sulforaphane in animal models of both acute and chronic neurodegenerative conditions. In a rodent model of stroke, sulforaphane administration reduced the amount of brain damage, brain edema and protected retinal pigment epithet.[44] Sulforaphane has been reported to protect cultured neurons against oxidative stress and dopaminergic neurons against mitochondrial toxins.[45]

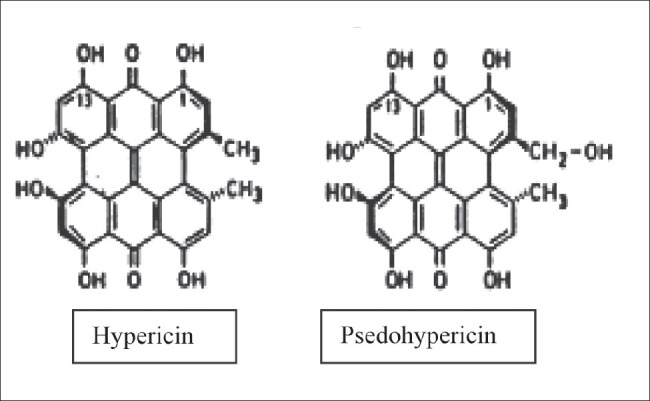

Hypericin and pseudohypericin

Naphthodianthrones such as hypericin and pseudohypericin are predominant components of Hypericum perforatum. There is strong evidence that hypericin and pseudohypericin [Figure 5] contribute to the antidepressant action. Inhibition of monoamine oxidase is one mechanism by which some antidepressants operate to increase levels of neurotransmitters such as serotonin, norepinephrine, or dopamine.[46] This chemical appears to block synaptic re-uptake of serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine.[47] Blocking neurotransmitter re-uptake elevates their synaptic concentration. This represents another mechanism by which synthetic antidepressants may operate.[47]

Figure 5.

Hypericin and Pseudohypericin from Hypericum perforatum

Curcumin

Several beneficial effects of curcumin for the nervous system (at least 10 known neuroprotective actions) have been reported. In an animal model of stroke, curcumin treatment protected neurons against ischemic cell death and ameliorated behavioral deficits.[48] Indeed, accumulating cell culture and animal model data show that dietary curcumin is a strong candidate for use in the prevention or treatment of major disabling age-related neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and stroke. Moreover, curcumin has been shown to reverse chronic stress-induced impairment of hippocampal neurogenesis and increase expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in an animal model of depression.[48]

Resveratrol

Resveratrol, a phytophenol present in high amounts in red grapes exhibits antioxidant activity. However, more recent findings shown that resveratrol enters the CNS rapidly following peripheral administration, and can protect neurons in the brain and spinal cord against ischemic injury. Administration of resveratrol to rats reduced ischemic damage to the brain in a model of stroke, and also protected spinal cord neurons against ischemic injury.[49] Resveratrol can protect cultured neurons against nitric oxide-mediated oxidative stress-induced death. Similarly, resveratrol protected dopaminergic neurons in midbrain slice cultures against metabolic and oxidative insults, a model relevant to Parkinson's disease.[49] Resveratrol protected cells against the toxicity of mutant huntingtin in worm and cell culture models.[50] In models relevant to Alzheimer's disease, resveratrol protected neuronal cells from being killed by amyloid β-peptide and promoted the clearance of amyloid β-peptide from cultured cells.[51]

Allium and allicin

Organosulfur compounds, such as the allium and allicin are present in high amounts in garlic and onions, and have been shown to be neuroprotective. In addition to their antioxidant activities, allyl-containing sulfides might activate stress-response pathways, resulting in the upregulation of neuroprotective proteins such as mitochondrial uncoupling proteins.[52] Moreover, allicin activates transient receptor potential (TRP) ion channels in the plasma membrane of neurons. Numerous other phytochemicals also activate TRP channels in neurons, including isothiocyanates, garlic alliums and cannabinoids, resulting in adaptive cellular stress responses.[52]

Phytochemicals in receptor binding activity

Numerous phytochemicals modify neuronal excitability by activating or inhibiting specific receptors or ion channels. Approximately 50 neurotransmitters belonging to diverse chemical groups have been identified in the brain. Acetylcholine (Ach), the first neurotransmitter to be characterized, has a very significant presence in the brain; recently it was determined that acetylcholine is essential for learning and memory.[53] Acetylcholine has been a special target for investigations for almost two decades because its deficit, among other factors, has been held responsible for senile dementia and other degenerative cognitive disorders, including Alzheimer's disease.

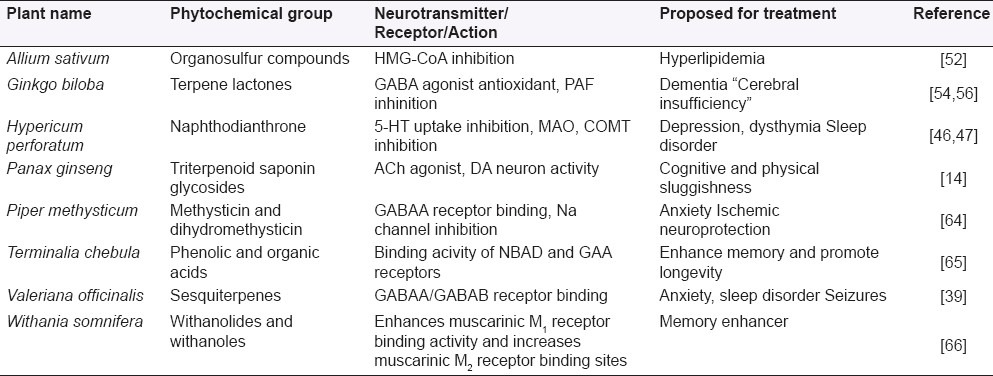

A well-characterized example is capsaicin, the phytochemical responsible for the striking noxious physiological effects of hot peppers; capsaicin activates specific Ca2+ channels called vanilloid receptors. There is now an impressive array of natural products that are known to influence the function of ionotropic receptors for GABA, the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain. A wide range of plant derived flavonoids, terpenes, and related substances modulate the function of ionotropic GABA receptors.[54] Such GABA modulators have been found in fruit (e.g., grapefruit), vegetables (e.g., onions), various beverages (including tea, red wine, and whiskey), and in herbal preparations (such as Ginkgo biloba and Ginseng). Many of the chemicals first used to study ionotropic GABA receptors are of plant origin including the antagonists bicuculline (from Dicentra cucullaria)[54] and picrotoxin (from Anamirta cocculus)[55] and the agonist muscimol (from Amanita muscaria).[56] These substances are known to cross the blood–brain barrier and are thus able to influence brain function. Low levels of activation of glutamate receptors can enhance synaptic plasticity and protect neurons against dysfunction and degeneration, in part by inducing the expression of neurotrophic factor. In addition, several phytochemicals are well-known for their actions on the nervous system by activating transient receptor potential (TRP) calcium channels in the nerve cell membrane. Capsaicin (a noxious chemical in hot peppers), allicin (a pungent agent in garlic) and Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) all activate TRP channels.[56] Some of the phytochemical mechanisms on different neurotransmitters or receptors are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Neurotransmitter or receptor binding activity of some medicinal herbs

CONCLUSION

Plants, in the form of herbs, spices and foods, constitute an unlimited source of molecules available for improving human health. However, a single plant contains hundreds or thousands of secondary, bioactive metabolites, a chemical diversity that determined the evolutionary success of plants, favoring their adaptation to a changing environment. In this view, to ascribe the health-promoting effects of a medicinal herb or a plant food only to a molecule, or a single class of compounds, represents an inappropriate and inopportune task. It is likely that different phytochemicals produce in vivo additive and/or synergistic effects, thus amplifying (or reducing/inhibiting) their activities.

Many of the phytochemicals that have recently been reported to exert neuroprotective effects in various experimental models of neurological disorders, were previously shown to have cytostatic or cytotoxic effects on cancer cells. Although demand for phytotherapeutic agents is growing, there is need for their scientific validation before plant–derived extracts gain wider acceptance and use. So-called “natural” products may provide a new source of beneficial neuropsychotropic drugs. These studies provide a phytochemical basis for some of the effects that these herbal preparations have on brain function and neuroprotection. As implicitly outlined in this survey, most of our current knowledge about CNS-active plants of cultural and traditional importance arose from ethnobotanical and ethnopharmaceutical (including historical) studies, as for other natural active ingredients. Moreover, for a suitable neuroprotective agent, a very important property regards its ability to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB), in order to reach the target sites of the CNS. Finally, though the presence of receptors or transporters for polyphenols or other phytochemicals in brain tissues remains to be ascertained, compounds with multiple targets appear as a potential and promising class of therapeutics for the treatment of neurodisorders.

Finally, though the presence of receptors or transporters for polyphenols or other phytochemicals in brain tissues remains to be ascertained, compounds with multiple targets appear as a potential and promising class of therapeutics for the treatment of diseases with a multifactorial etiology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are thankful to the Director, Defence Food Research Laboratory, Mysore for his kind support.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Halliwell B. Reactive oxygen species and central nervous systems. J Neurochem. 1992;59:1609–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb10990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolominsky Rabas PL, Sarti C, Heuschmann PU, Graf C, Siemonsen S, Neundoerfer B, et al. A prospective communitybased study of stroke in Germany. The Erlangen Stroke Project (ESPro): Incidence and case fatality at 1, 3, and 12 months. Stroke. 1998;29:2501–6. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.12.2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Commenges D, Scotet V, Renaud S, Jacqmin-Gadda H, Barberger Gateau P, Dartigues JF. Intake of flavonoids and risk of dementia. Eur J Epidemiol. 2000;6:357–63. doi: 10.1023/a:1007614613771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar V. Potential medicinal plants for CNS disorders: An overview. Phytother Res. 2006;20:1023–35. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selvam AB. Inventory of Vegetable Crude Drug samples housed in Botanical Survey of India, Howrah. Pharmacognosy Rev. 2008;2:61–94. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lobo V, Patil A, Phatak A, Chandra N. Free radicals, antioxidants and functional foods: Impact on human health. Pharmacogn Rev. 2010;4:118–26. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.70902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pueyo IU, Calvo MI. Phytochemical Study and Evaluation of Antioxidant, Neuroprotective and Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitor Activities of Galeopsis ladanum L. extracts. Pharmacognosy Mag. 2009;5:287–90. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Houghton PJ, Raman A. Laboratory handbook for fractionation of natural extracts. London: Chapman and Hall; 1998. p. 199. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capasso R, Izzo AA, Pinto L, Bifulco T, Vitobello C, Mascolo N. Phytotherapy and quality of herbal medicines. Fitoterapia. 2000;71:S58–65. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(00)00173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plotkin MJ. Natural resources and human health: Plants of medicinal and nutritional value. Proceedings. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1992. Ethnomedicine: Past, present and future; pp. 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harvey AL. Medicines from nature: Are natural products still relevant to drug discovery? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20:196–8. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01346-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gong X, Sucher NJ. Stroke therapy in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM): Prospects for drug discovery and development. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20:191–6. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01276-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chandrasekaran K, Mehrabian Z, Spinnewyan B, Drieu K, Kiskum G. Neuroprotective effects of bilobalide, a component of Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb 761), in gerbil global brain ischemia. Brain Res. 2001;922:282–92. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03188-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nocerino E, Amato M, Izzo AA. The aphrodisiac and adaptogenic properties of ginseng. Fitoterapia. 2000;71:S1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(00)00170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anand T, Naika M, Swamy MS, Khanum F. Antioxidant and DNA damage preventive properties of Bacopa monniera (L) Wettst. Free Rad Antioxidants. 2011;1:89–95. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh HK, Dhawan BN. Neuropsychopharmacological effects of the Ayurvedic nootropic Bacopa monniera Linn. (Brahmi) Indian J Pharmacol. 1997;29:S359–65. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russo A, Borrelli F. Bacopa Monniera, A reputed nootropic plant: An overview. Phytomedicine. 2005;12:305–17. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nalini K, Aroor A, Karanth K, Rao A. Centella asiatica fresh leaf aqueous extract on learning and memory and biogenic amine turnover in albino rats. Fitoterapia. 1992;63:232–7. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anand T, Naika M, Kumar PG, Khanum F. Antioxidant And DNA Damage Preventive Properties Of Centella asiatica (L). Urb. Pharmacognosy Mag. 2011;2:53–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weiss RF, Fintelmann V. Herbal Medicine. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2000. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Viana M, Barbas C, Banet B, Bonet MV, Castro M, Fraile MU, et al. In vitro effect of a flavonoid-rich extract on LDL oxidation. Athelosclerosis. 1996;123:83–91. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(95)05763-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pinder RM, Sandler M. Alcohol, wine and mental health: Focus on dementia and stroke. J Psychopharm. 2004;18:449–56. doi: 10.1177/0269881104047272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moosmann B, Behl C. Antioxidants as treatment for neurodegenerative disorders. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2002;11:1407–35. doi: 10.1517/13543784.11.10.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larson RA. The antioxidants of higher plants. Phytochemistry. 1988;27:969–78. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berger MM. Can oxidative damage be treated nutritionally? Clin Nutr. 2005;24:172–83. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Floyd RA. Antioxidants, oxidative stress and degenerative neurological disorders. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1999;222:236–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1373.1999.d01-140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu RH. Health benefits of fruit and vegetables are from additive and synergistic combinations of phytochemicals. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:517S–20S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.3.517S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joseph JA, Bartus RT, Clody DE. Reversing the deleterious effects of aging on neuronal communication and behavior: Beneficial properties of fruit polyphenolic compounds. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:313S–6S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.1.313S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ikeda K, Negishi H, Yamori Y. Antioxidant nutrients and hypoxia/ischemia brain injury in rodents. Toxicology. 2003;189:55–61. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(03)00152-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo S, Yan J, Yang T, Yang X, Bezard E, Zhao B. Protective effects of green tea polyphenols in the 6- OHDA rat model of Parkinson's disease through inhibition of ROS-NO pathway. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:1353–62. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang B, Safa R, Rusciano D, Osborne NN. Epigallocatechin gallate, an active ingredient from green tea, attenuates damaging influences to the retina caused by ischemia/reperfusion. Brain Res. 2007;1159:40–53. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ehrnhoefer DE, Duennwald M, Markovic P, Wacker JL, Engemann S. Green tea (−)-epigallocatechin-gallate modulates early events in huntingtin misfolding and reduces toxicity in Huntington's disease models. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:2743–51. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mandel SA, Avramovich-Tirosh Y, Reznichenko L, Zheng H, Weinreb O, Amit T. Multifunctional activities of green tea catechins in neuroprotection.Modulation of cell survival genes, irondependent oxidative stress and PKC signaling pathway. Neurosignals. 2005;14:46–60. doi: 10.1159/000085385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sutherland BA, Rahman RM, Appleton I. Mechanisms of action of green tea catechins, with a focus on ischemia-induced neurodegeneration. J Nutr Biochem. 2005;17:291–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Youdim KA, Qaiser MZ, Begley DJ. Flavonoid permeability across an in situ model of the blood-brain barrier. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;36:592–604. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2003.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Youdim KA, Spencer JP, Schroeter H, Rice-Evans C. Dietary flavonoids as potential neuroprotectants. Biol Chem. 2002;383:503–19. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pearson VE. Galantamine: A new Alzheimer drug with a past life. Ann Pharmacother. 2001;35:1406–13. doi: 10.1345/aph.1A092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Halliwell B. Oxidative stress and cancer: Have we moved forward? Biochem J. 2007;401:1–11. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ortiz JG, Nieves-Natal J, Chaves P. Effects of Valeriana officinalis extracts on [3H] flunitrazepam binding, synaptosomal [3H] GABA uptake, and hippocampal [3H] GABA release. Neurochem Res. 1999;24:1373–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1022576405534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sakina MR, Dandiya PC. A psycho-neuropharmacological profile of Centella asiatica extract. Fitoterapia. 1990;61:291–6. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crews C, Hough P, Godward J. Study of the main constituents of some authentic walnut oils. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:4853–60. doi: 10.1021/jf0478354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCann JC, Ames BN. Is docosahexaenoic acid, an n23 longchain polyunsaturated fatty acid, required for development of normal brain function? An overview of evidence from cognitive and behavioral tests in humans and animals. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:281–95. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.82.2.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yehuda S, Rabinovitz S, Carasso RL. The role of polyunsaturated fatty acids in restoring the aging neuronal membrane. Neurobiol Aging. 2002;23:843–53. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao J, Kobori N, Aronowski J, Dash PK. Sulforaphane reduces infarct volume following focal cerebral ischemia in rodents. Neurosci Lett. 2006;393:108–12. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Han JM, Lee YJ, Lee SY, Kim EM. Protective effect of sulforaphane against dopaminergic cell death. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:249–56. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.110866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schulz V, Haänsel R, Tyler V. Rational Phytotherapy: A Physician's Guide to Herbal Medicine. Berlin: Springer- Verlag; 1998. pp. 1–155. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chatterjee SS, Bhattacharya SK, Wonneman M, Singer A, Muller WE. Hyperforin as a possible antidepressant component of Hypericum extracts. Life Sci. 1998;63:499–510. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00299-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu Y, Ku B, Cui L, Li X, Barish PA, Foster TC, et al. Curcumin reverses impaired hippocampal neurogenesis and increases serotonin receptor 1A mRNA and brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression in chronically stressed rats. Brain Res. 2007;1162:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang SS, Tsai MC, Chih CL, Hung LM, Tsai SK. Resveratrol reduction of infarct size in Long- Evans rats subjected to focal cerebral ischemia. Life Sci. 2001;69:1057–65. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01195-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parker JA, Arango M, Abderrahmane S, Lambert E, Tourette C, Catoire H, et al. Resveratrol rescues mutant polyglutamine cytotoxicity in nematode and mammalian neurons. Nat Genet. 2005;37:349–50. doi: 10.1038/ng1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marambaud P, Zhao H, Davies P. Resveratrol promotes clearance of Alzheimer's disease amyloid- beta peptides. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:37377–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508246200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oi YM, Imafuku C, Shishido Y, Kominato S, Nishimura K. Allyl-containing sulfides in garlic increase uncoupling protein content in brown adipose tissue, and noradrenaline and adrenaline secretion in rats. J Nutr. 1999;129:336–42. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.2.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Winkler J, Suhr ST, Gage FH, Thal LJ, Fischer LJ. Essential role of neocorticat acetylcholine in spatial memory. Nature. 1995;375:484–7. doi: 10.1038/375484a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Curtis DR, Duggan AW, Felix D, Johnston GA. Bicuculline and central GABA receptors. Nature. 1970;228:676–7. doi: 10.1038/228676a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jarboe CH, Porter LA, Buckler RT. Structural aspects of picrotoxinin action. J Med Chem. 1968;2:729–31. doi: 10.1021/jm00310a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Johnston GA. GABAA receptor channel pharmacology. Curr Pharm Design. 2005;11:1867–85. doi: 10.2174/1381612054021024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zanoli P, Avallone R, Baraldi M. Sedative and hypothermic effects induced by b-asarone, a main component of Acorus Calamus. Phytother Res. 1998;12:114–6. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gupta P, Siripurapu KB, Ahmad A, Palit G, Arrora A, Maurya R. Antistress constituents of Evolvulus alsinoides, an ayurvedic crude drug. Chem Pharma Bull. 2007;55:771–6. doi: 10.1248/cpb.55.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dhingra D, Parle M, Kulkarni SK. Memory enhancing activity of Glycyrrhiza Glabra in mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;91:361–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rui DS, Prediger M, Fernandes S, Daniel RS. Effects of acute administration of hydroalcoholic extract of mate tea leaves (Ilex Paraguariensis) in animal models of learning and memory. J Ethanopharmacol. 2008;120:465–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee H, Kim YO, Kim H. Flavonoid wogonin from medicinal herb is neuroprotective by inhibiting inflammatory activation of microglia. FASEB J. 2003;17:1943–4. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0057fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Topic B, Tani E, Tsiakitzis K, Kourounakis PN, Dere E, Hasenohrl RU, et al. Enhanced maze performance and reduced oxidative stress by combined extracts of Zingiber Officinals and Ginkgo Biloba in the aged rat. Neurobiol Ageing. 2002;23:135–43. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00241-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lu YJ, Zhou J, Zhang SM, Zhang HY, Zheng XX. Inhibitory effects of jujuboside A on EEG and hippocampal glutamate in hyperactive rat. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2005;6:265–71. doi: 10.1631/jzus.2005.B0265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jussofie A, Schmiz A, Hiemke C. Kavapyrone enriched extract from Piper methysticum as modulator of the GABA bindingsite in different regions of rat brain. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1994;116:469–74. doi: 10.1007/BF02247480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Misra R. Modern drug development from traditional medicinal plants using radioligand rexceptor-binding assays. Med Res Rev. 1998;18:383–402. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1128(199811)18:6<383::aid-med3>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schliebs R, Liebmann A, Bhattacharya SK, Kumar A, Ghosal S, Bigl V. Systemic administration of defined extracts from Withania somnifera (Indian Ginseng) and shilajit differentially affects cholinergic but not glutamatergic and gabaergic markers in rat brain. Neurochem Int. 1997;30:181–90. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(96)00025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]