Abstract

Background:

The aim of this systematic review and associated meta-analysis was to compare manual and powered brushes in relation to the removal of plaque and gingival health. Stain removal, adverse effects and microbiological evaluation cost were also considered.

Materials and Methods:

To be included in the review, a trial had to be a randomized-controlled trial (RCT) comparing manual and powered brushes. Trials confined to comparing different types of powered or different types of manual brushes were excluded. Split mouth designs were eligible. Trials with subjects of specific age group (18–25 years) were included. The primary outcomes were plaque and gingival health with data defined as short-term (0–28 days) duration were analyzed. Powered brushes were categorized into three groups depending on mode of action. Numerical data extracted were checked by a fourth reviewer for accuracy.

Results:

Three trials with full articles were identified. These include trials published between 2002 and 2005. The trials involved 56 subjects at baseline, without loss of subject for follow up. Powered brushes reduced plaque and gingivitis at least as effectively as manual brushing. Ionic brushes statistically significantly reduced plaque and gingivitis.

Conclusion:

In general there was no evidence of a statistically significant difference between powered and manual brushes. However, ionic brushes significantly reduce plaque and gingivitis in both the short-term evaluations. The clinical significance of this reduction is not known. Observation of methodological guidelines and greater standardization of design would benefit both future trials and meta-analyses.

Keywords: Common type of control toothbrush, electric, ionic, meta-analysis, powered brush, ultrasonic

INTRODUCTION

Dental plaque is implicated in the etiology of dental caries, gingivitis and periodontitis, therefore the removal of plaque is thought to play a key role in the prevention of these diseases.[1] The relationship between plaque levels (oral hygiene) and periodontal disease is complex and not well understood. Similarly, when teeth are brushed with fluoride toothpaste there is considerable evidence of a caries reduction.[2] However, this reduction in caries levels is principally due to the action of fluoride in the toothpaste rather than brushing per se.[3]

Commercial powered (electric) toothbrushes were first introduced in the early 1960s,[4–7] although Frederick Wilhelm,[8] a Swedish clockmaker, patented the earliest device in 1855. Powered brushes were first introduced with a back and forth action. Subsequent development has lead to the development of rotary action brushes and more recently higher frequency of vibration brushes.[9,10]

One study has shown that 36 months after purchase, 62% of people were still using their powered brush on a daily basis.[11] The reported compliance level was high and was unrelated to any social factors of the population studied. Mechanical plaque removal with a manual toothbrush remains the primary method of maintaining good oral hygiene for the majority of the population.[10]

Despite the increasing interest in powered toothbrushes, their effectiveness in comparison to manual toothbrushes has not previously been evaluated through a systematic review of the literature. Systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials are seen as the gold standard for assessing the effectiveness of healthcare interventions. By following explicit, well-documented, scientific methodology, they aim to provide an objective, comprehensive view of the research literature.

Systematic review is a thorough, comprehensive and explicit way of interrogating the literature. It typically involves various steps. Meta-analysis is a statistical procedure that integrates the results of several independent studies considered to be “combinable”. It is a statistical approach to combine data derived from systematic review and it gives a more objective appraisal of the evidence than traditional narrative reviews. It provides a more precise estimate of a treatment effect. Therefore, it should be based upon underlying systematic review but not every systematic review leads to meta-analysis.

The aim of this systematic review and associated meta-analysis was to compare manual and powered brushes in relation to the removal of plaque and gingival health.

The Medline search revealed no report on meta-analysis of studies wherein a common type of control toothbrush is compared with different powered toothbrushes in different studies. Hence, the present meta-analysis includes effect of three powered toothbrushes versus control toothbrush.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

To be included in the review a trial had to be a randomized-controlled trial (RCT) comparing manual and powered brushes. Trials confined to comparing different types of powered or different types of manual brushes were excluded. Split mouth designs were eligible. Trials with subjects of specific age group (18–25 years) were included but trials including individuals with special needs and orthodontic bands that would compromise their brushing ability were excluded.

For the purpose of the review, powered brushes were defined as those with a mechanical movement and additional features of the brush head. Powered brushes were divided into three groups depending on their mode of action.

Counter oscillation (Braun Oral B Ultra Plaque Remover): In which adjacent tufts of bristles (usually 6–10) rotate in one direction and then the other, independently. Each tuft rotating in the opposite direction to that adjacent to it.

Ultrasonic (Ultrasonex): In which the brush bristles vibrate at ultrasonic frequencies (i.e. above 20 kHz)

Ionic (hyG): In which ions are released from brush bristles, this brings about disruption of plaque from tooth surface.

Identification of relevant studies

The search strategy followed was Medline database and hand searching. These databases were searched using controlled vocabulary (MeSH terms) and free text words. All references cited in the included trials were checked. The clinical reports in Japanese were translated to English. There was a lack of data on common manual tooth brush (control) compared with different types of powered toothbrushes. The hand search led to the procurement of three RCTs done with similar inclusion and exclusion criteria, indices used for plaque and gingival health and microbiological evaluation in single centre.

Study selection and data extraction

Three reviewers independently reviewed the titles and abstracts identified through the hand search strategy. If, in the opinion of both reviewers, an article clearly did not fulfill the defined inclusion criteria it was considered ineligible. Full reports of three trials were obtained for assessment. For plaque, data were extracted where possible, as the Turesky modification of the Quigley–Hein Plaque Index.[12] For gingivitis, where possible, data were extracted as the Gingival Bleeding Index of Ainamo and Bay.[13] Data were extracted for whole mouth scores rather than part mouth scores. Trial data was recorded as ‘short-term’ (baseline to 28 days). All numerical data were checked by a fourth reviewer for accuracy and entered.

Data

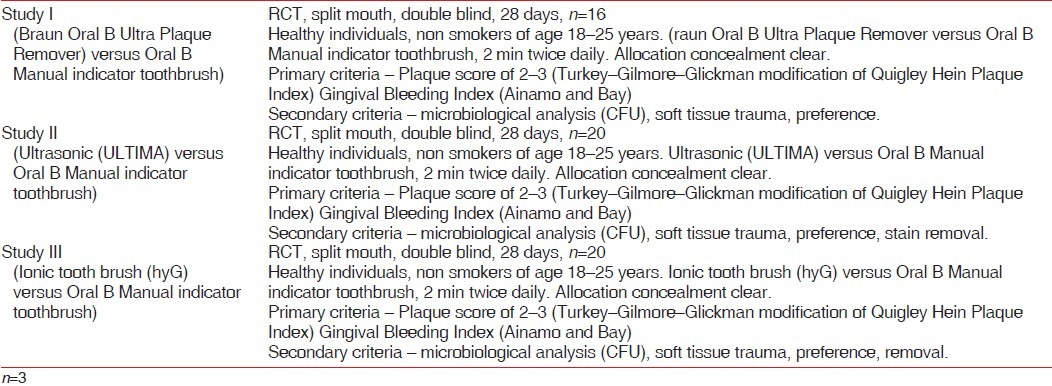

Considering the above measures, present meta-analysis included three studies, which are RCT, split-mouth design, double blind with similar control brush. Clinical parameters included Plaque and Gingival Bleeding Index. Three studies are basically combinable with similar assessment features [Table 1].

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

RESULTS

The search identified three trials with full articles.[14–16] These include trials being published between 2002 and 2006. The trials involved 56 subjects at baseline, without loss of subject for follow up. All trials were reported as self-funding trials; however, ultrasonic and ionic toothbrush were supplied free of cost for research trial. All trials reported full mouth scores for plaque index and gingival bleeding index.

In Study I, the electric toothbrush (Braun Oral B Ultra Plaque Remover) and manual toothbrush (Oral B Indicator) were compared. On statistical analysis it was found that electronic toothbrush showed 86% (1.77±0.39 SD) reduction of plaque index and 95% of reduction in Bleeding index from baseline, whereas manual toothbrush showed 85% (1.72±0.35) of reduction in Plaque index and 90% reduction in Bleeding index. Both brushes showed significant reduction from baseline. On intergroup comparison there was no significant difference.[14]

In study II, ultrasonic and manual brushes showed statistically significant reduction of Plaque index (50% and 60%, respectively) and Bleeding index (35% and 26%, respectively) from baseline but intergroup comparison showed non-significant results.[15]

In Study III, ionic and manual brushes showed statistically significant reduction of Plaque index (83% and 17%, respectively) and Bleeding index (97% and 33%, respectively) from baseline but intergroup comparison showed non-significant results. The Effect size represents the magnitude of impact of intervention on an outcome or degree of association between two variables.[16]

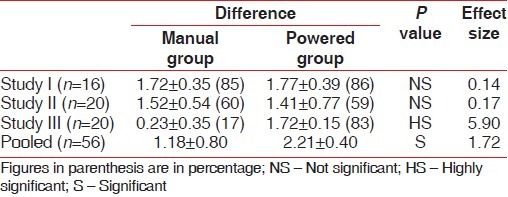

Effect size for plaque index

Effect size calculation was done for all the three trials wherein Study I and Study II showed value 0.14 and 0.17, respectively, which designates a very small effect, whereas Study III showed effect size value of 5.9 which designates a very large effect. Effect size of pooled data showed value of 1.72, which designates a very large effect of using powered toothbrush for plaque removal as compared to manual toothbrush [Table 2].

Table 2.

Summary of pooled estimates of effect for gingival bleeding index

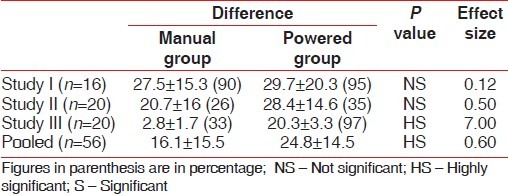

Effect size for gingival bleeding index

Study I showed a value of 0.12 which designates a very small effect, Study II showed value 0.5 which designates a moderate effect whereas Study III showed effect size value of 7 which designates a very large effect. Effect size of pooled data showed value of 0.6, which designates a moderately large effect of using powered toothbrush for reduction of gingival bleeding as compared to manual toothbrush [Table 3].

Table 3.

Summary of pooled estimates of effect for gingival bleeding index

All trials reported on microbiological analysis (CFU), soft tissue trauma wherein trial II reported stain removal efficacy. None of the adverse effects reported were a major cause for concern. CFU results for Study I (Electric) and Study II (Ultrasonic) showed greater CFU reduction in powered toothbrush group but were not statistically significant as compared to manual toothbrush whereas in Study III Ionic brush showed statistically significant reduction from baseline to 28th day.

DISCUSSION

People brush their teeth for a number of reasons: to feel fresh and confident; to have a nice smile; to avoid bad breath and avoid disease. There is overwhelming evidence that toothbrushing reduces gingivitis.[17] It may prevent periodontitis, although many factors as well as plaque are associated with periodontitis including tobacco usage and medical factors. Tooth brushing certainly prevents tooth decay if carried out in conjunction with fluoride toothpaste.[3] These benefits occur whether the brush used is manual or powered. It is likely that on initial use of a new device such as a new powered brush will have a novelty effect.

As mentioned in Tables 2 and 3, the results of study I (electric tooth brush) are similar to study done by Ainamo et al.[18] whereas Barnes et al.[19] showed significant result with use of Electric toothbrush. The results of study II (ultrasonic tooth brush) are similar to study done by Forgas et al.[20] whereas Terezhalmy et al.[9] showed significant result with use of Ultrasonic toothbrush and the results of Study III (ionic tooth brush) are similar to study done by Van Swol et al.[21] showed significant result with use of Ionic toothbrush. The effect size of pooled data for plaque index demonstrates value of 1.72, which designates very large effect of using powered toothbrush for plaque removal as compared to manual brush. The plaque score in short-term trials of rotation oscillation brushes was SMD 20.44. Using this level of effectiveness as an example, in the trial by Cronin[22] a similar SMD (20.45) corresponded to a mean difference in the Turesky modification of the Quigley Hein index of 0.27. The mean plaque score among those using manual brushes in the trial by Cronin was 2.55 and thus the difference is 11%.[22] The effect size of pooled data for gingival bleeding index demonstrates value of 0.6, which designates moderately large effect of using powered toothbrush for reduction of gingival bleeding as compared to manual brush. For gingival scores the SMD in short-term trials of rotation oscillation brushes was also 20.44. Again, using this level of effectiveness, in the trial by Heasman,[23] the SMD of 20.42 corresponded to a mean difference in the Loe and Silness Gingival Index[24] of 0.09. The mean gingival index score for those using manual brushes in the trial was 1.64 and thus the difference is 6%.

This raises the question, what level of plaque removal and reduction in gingivitis will result in clinically significant improvements in oral health? Arbitrary thresholds are set, for example, the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs[25] suggested a 15% statistically significant reduction versus baseline in gingivitis and a statistically significant reduction in plaque scores; others have suggested 20% reductions as an appropriate threshold.[26,27] Unfortunately, at present there is no evidence to base such a threshold for either gingivitis or plaque. It has been suggested that thresholds for clinical significance are set in advance on clinical grounds.[28] One possible weakness of the review is inclusion of only tree studies; however, strength of this review is that it is a single centre study with a similar criteria. Whilst this approach allowed more powerful meta-analyses, it is possible that toothbrushes whose actions or design had subtle differences were more or less effective. Filament arrangement, orientation, size shape flexibility, brush head size and shape along with the presence or absence of a timer would be too difficult to define and standardize across brush types. Time spent brushing may be related to the effectiveness of brushing and therefore a timer may be a particularly useful adjunct and motivator.[28]

One possible confounding factor is lack of compliance; however, gingivitis and plaque levels improved in the individual studies suggesting at least some compliance. Further, in randomized trial compliance levels are likely to be equal across the groups. One way to overcome this is to supervise brushing prior to measurements; this reduces some confounding factors but cannot be described as ‘real life’ and therefore has its own problems. In present review, the compliance was not an issue in all the three RCTs. Individuals who prefer to use a powered brush can be assured that in general there was no statistical difference between powered and manual toothbrushes and powered brushes are as safe. As no trail compared durability, reliability or cost of using manual versus powered brushes, it is not possible to make a clear recommendation on toothbrush superiority. The review compared manual versus powered brushes and not comparisons of differing powered brushes and therefore different powered toothbrush manufacturer's products.[28] In the present meta-analysis, the control brushes were similar in all the studies unlike reported systematic review. As compared to the systematic review,[29] the present meta-analysis included similar age group, plaque and gingival bleeding indices, duration of brushing; children group and subjects with orthodontic bands were excluded. For all of these reasons no recommendation regarding the effectiveness or efficiency of any specific powered toothbrush is made. However, short coming of present metaanalysis is that it includes only three studies of small sample size and short duration.

Trials of longer duration are required to fully evaluate powered brushes. Data on the long-term benefits of powered toothbrushes would be valuable in their own right and could be used to trial other outcomes such as the adverse effects and benefits in the prevention of periodontitis and dental caries. Moreover, more trials would lend greater power to systematic reviews of the effectiveness of powered toothbrushes.

CONCLUSION

Powered brushes achieve a moderate reduction of plaque and gingival bleeding scores. Individuals who prefer to use a powered brush can be assured that in general there was no statistical difference between powered and manual brushes. The powered brushes are safe. As no trial compared durability and reliability of using manual versus powered brushes, it is not possible to make clear recommendation of toothbrush superiority. However, considering cost of powered brushes, manual brushes are still a choice for routine use in Indian scenario.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Loe H, Theilade E, Jensen SB. Experimental gingivitis in man. J Periodontol. 1965;36:177–87. doi: 10.1902/jop.1965.36.3.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marinho VC, Higgins JP, Logan S, Sheiham A. In The Cochrane Library. 2. Oxford: Update Software; 2003. Fluoride toothpastes for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents (Cochrane Review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chesters RK, Huntingdon E, Burchill CK, Stephen KW. Effects of oral care habits on caries in adolescents. Caries Res. 1992;26:299–304. doi: 10.1159/000261456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chilton NW, Di-Do A, Rothner JT. Comparison of the effectiveness of an electric and standard toothbrush in normal individuals. J Am Dent Assoc. 1962;64:777. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1962.0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cross WG, Forrest JO, Wade AB. A comparative study of tooth cleansing using conventional and electrically operated toothbrushes. Br Dent J. 1962;113:19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoover DR, Robinson HG. Effect of automatic and hand-brushing on gingivitis. J Am Dent Assoc. 1962;65:361–7. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1962.0262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elliot JR. A comparison of the effectiveness of a standard and electric toothbrush. J Periodontol. 1963;34:375–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scutt JS, Swann CJ. The first mechanical toothbrush? Br Dent J. 1975;139:152. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4803538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terezhalmy GT, Gagliardi VB, Rybicki L, Kaufman MJ. Clinical evaluation of the efficacy and safety of the Ultrasonex toothbrush: a 30-day study. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 1995;15:866–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weijden van der GA, Timmerman MF, Danser MM, Velden van der U. The role of electric toothbrushes: Advantages and limitations. Proceedings of the European Workshop on Mechanical Plaque Control. 1998:138–55. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stavineke K, Saderfeldt B, Sjadin B. Compliance in the use of electric toothbrushes. Acta Odontol Scand. 1995;53:17–9. doi: 10.3109/00016359509005938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turesky S, Gilmore ND, Glickman I. Reduced plaque formation by the chloromethyl analogue of vitamin C. J Periodontol. 1970;41:41–3. doi: 10.1902/jop.1970.41.41.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ainamo J, Bay I. Problems and proposals for recording gingivitis and plaque. Int Dent J. 1975;25:229–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vandana KL, Sangeeta B, Chandrashekhar KT. Comparative evaluation of Electric (Braun Oral B Ultra Plaque Remover) and manual toothbrush on oral hygiene status and microbiological parameters. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2003;6:54–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vandana KL, Penumatsa GS. A Comparative Evaluation of an Ultrasonic and a Manual Toothbrush on the Oral Hygiene Status and Stain Removing Efficacy. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2004;22:33–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deshmukh J, Vandana KL, Chandrashekar KT, Savitha B. Clinical evaluation of an ionic tooth brush on oral hygiene status, gingival status and microbial parameters. Indian J Dent Res. 2006;17:74–7. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.29887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lang NP, Cumming BR, Loöe H. Toothbrushing frequency as it relates to plaque accumulation and gingival health. J Periodontol. 1973;44:396–405. doi: 10.1902/jop.1973.44.7.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ainamo J, Xie Q, Ainamo A, Kallio P. Assessment of the effect of an oscillating/rotating electric toothbrush on oral health. A 12-month longitudinal study. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:28–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb01180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barnes CM, Weatherford TW, 3rd, Menaker L. A comparison of the Braun Oral-B Plaque Remover (D5) electric and a manual toothbrush in affecting gingivitis. J Clin Dent. 1993;4:48–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forgas-Brockmann LB, Carter-Hanson C, Killoy WJ. The effects of an ultrasonic toothbrush on plaque accumulation and gingival inflammation. J Clin Periodontol: 1998;25:375–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Swol RL, Van Scotter DE, Pucher JJ, Dentino AR. Clinical evaluation of an ionic toothbrush in the removal of established plaque and reduction of gingivitis. Quintessence Int. 1996;27:389–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cronin M, Dembling W, Warren PR, King DW. A 3-month clinical investigation comparing the safety and efficacy of a novel electric toothbrush (Braun Oral-B 3D Plaque Remover) with a manual toothbrush. Am J Dent. 1998;11(Suppl):17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heasman PA, Stacey F, Heasman L, Sellers P, Macgregor ID, Kelly PJ. A comparative study of the Philips HP 735.Braun/ Oral B D7 and the Oral B 35 Advantage toothbrushes. J Clin Periodontol. 1999;26:85–90. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.1999.260204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loe H, Silness J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. I. Prevalence and severity. Acta Odontologica Scand. 1963;21:533–51. doi: 10.3109/00016356309011240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Imrey PB. Logical and analytical issues in dental/oral product comparison research. J Periodontal Res. 1992;27(special issue):328–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1992.tb01689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imrey PB, Chilton NW, Pihlstrom HW. Recommended revisions to American Dental Association guidelines for acceptance of chemotherapeutic products for gingivitis control. J Dent Res. 1994;29:299–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1994.tb01225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.D’Agostino Discussion. Logical and analytical issues in dental/oral product comparison research. J Periodontal Res. 1992;27(special issue):349–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1992.tb01689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deery C, Heanue M, Deacon S, Robinson PG, Walmsley AD, Worthington H, et al. The effectiveness of manual versus powere toothbrushes for dental health: A systematic review. J Dent. 2004;32:197–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]