Abstract

Background:

Predictable root coverage and good colour match are the major therapeutic end points in the treatment of gingival recession. Alloderm has been used as a substitute to connective tissue graft, but its colour match in populations with a high degree of melanin pigmentation has not been extensively studied. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of an Acellular dermal matrix graft for root coverage procedures and to objectively analyze the post-operative esthetics using a Visual Analog Scale (VAS).

Materials and Methods:

Both male and female patients were selected, aged 20-50 years presenting with aesthetic problems due to the exposure of recession defects when smiling. A total of 14 patients contributed to 15 sites, each site falling into Miller's class I or class II gingival recession.

Results:

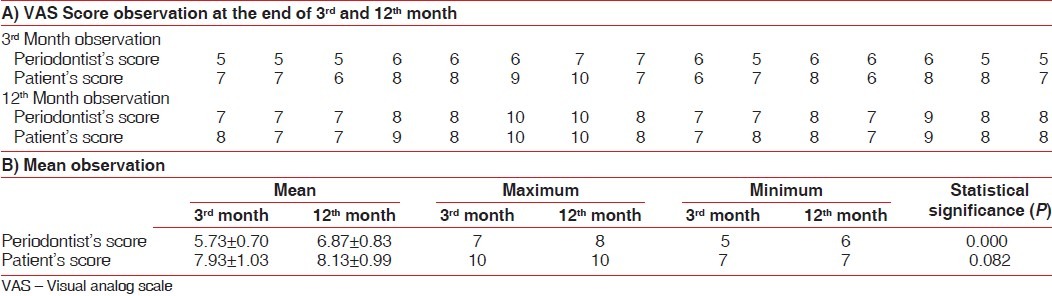

A total of 15 sites were treated and a mean coverage of (85.56±21.70 and 83.33±21.82%) was obtained at the end of 3rd and 12th month respectively. A mean VAS score of 7.93±1.03 and 8.13±0.99 (3rd and 12th month) and 5.73±0.70 and 6.87±0.83 (3rd and 12th month) was obtained when the colour match recorded by the patients and an independent observer, respectively.

Conclusion:

The study showed that acellular dermal matrix graft (alloderm) may be successfully used to treat gingival recession, as adequate root coverage may be predictably obtained. The grafted areas underwent melanization from the 6th month onwards and complete blending with the adjacent sites was obtained at 1 year.

Keywords: Acellular dermal matrix graft (alloderm), colour match, gingival recession, root coverage, subepithelial connective tissue graft

INTRODUCTION

The major therapeutic goals in mucogingival surgery are correction of esthetic problems, hypersensitivity and/or shallow root carious lesions. Several techniques such as the free gingival graft,[1–3] Laterally repositioned flap,[4–6] Coronally positioned flap[7,8] and double papilla graft[9] have been proposed for the correction of these mucogingival deformities.

Originally Sullivan and Atkins(1968)[1] described a technique for coverage of exposed root surfaces using the free gingival autogenous graft. The graft survival over large expanses of avascular root surfaces was however unpredictable, complete root coverage was hence rarely achieved. Moreover, the procedure involved two surgical sites, creating a large denuded area on the palate that resulted in considerable postoperative discomfort to the patients. The inconsistent color blending of the graft with adjacent gingival tissues limits its use in esthetically sensitive areas.

Karring and Co-workers[10] demonstrated that the underlying connective tissue has a direct bearing on the type of epithelium that is superimposed upon it. Edel[11] showed that a significant increase in the volume of gingiva can be achieved by grafting gingival connective tissue alone.

Langer and Langer[12] described the subepithelial connective tissue graft technique in root coverage on both single and multiple adjacent teeth. The advantage of this graft is the double blood supply from the overlying flap and palatal connective tissue, which maximize the graft survival. It also provides excellent esthetic results. Several modifications of this technique have been proposed and connective tissue grafts are considered the gold standard for treatment of gingival recession.[13–16]

However, this technique involves a certain degree of discomfort to the patient because an additional palatal donor site has to be prepared, increasing the risk of postoperative pain and hemorrhage. The post-operative discomfort has been considerably minimized through not fully eliminated by more conservative methods described by Bruno[17] and Hurzeler and Weng.[18]

Yukna et al,[19] demonstrated that allogenic freeze-dried skin graft is a clinically acceptable and beneficial grafting material for the treatment of mucogingival problems.

Recently, an Acellular dermal matrix graft has been used as a substitute for the palatal donor sites to increase the width of keratinized tissue around the teeth and implants,[20–22] for the treatment of alveolar ridge deformities[23] and for root coverage procedures.[23–25] Processing of the dermis obtained from human donor removes all cells, leaving a structurally intact connective tissue matrix composed of type-I collagen. Harris[23] reported the use of this acellular dermal matrix graft with coronally positioned flap for the treatment of gingival recession. The Acellular dermal matrix consistently integrated into the host tissue, maintaining structural integrity of the tissue and revascularized via preserved vascular channels. The color match obtained was also reported to be comparable to that of the connective tissue graft.

Most of the information in the literature related to colour match has been derived from subjective assessment of the postoperative results by the clinician. The patient perception of postoperative esthetics with soft tissue grafts including Alloderm has not been extensively studied, particularly in populations with high degree of melanin pigmentation.

Visual Analog Scale (VAS) has been used to provide a measurable scale to evaluate subjective phenomena such as pain, esthetics, etc.[26]

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of an acellular dermal matrix (alloderm) graft for root coverage procedures and to objectively analyze the post-operative esthetics using a VAS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

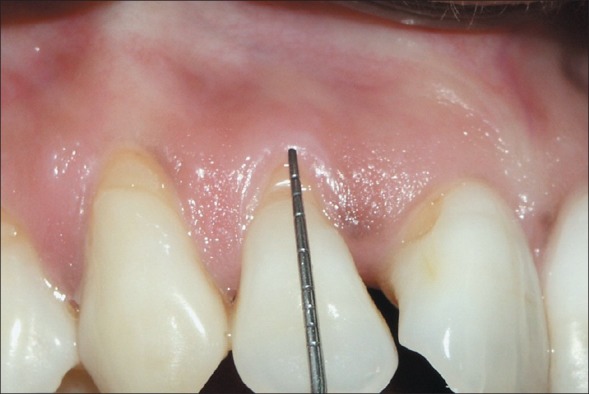

The study population consisted of male and female patients, aged 20-50 years with aesthetic problems due to the exposure of recession defects while smiling. A total of 14 patients contributed to 15 sites. The sites were decided on toss of the coin [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Pre operative facial view of gingival recession

The patients agreed to the study protocol and informed consent was obtained prior to treatment. The inclusion criteria are (1) The presence of at least one Miller's class I or class II gingival recession,[27] (2) Facial recession of maxillary and mandibular anteriors. The exclusion criteria included (1) The presence of severe cervical abrasion/root caries, (2) The presence of abnormal frenal attachment, (3) Current smokers, (4) Medically compromised patients.

The patients initially completed a plaque control program, till all of them achieved a full mouth plaque score (FMPS) <25%.

Pre operative measurements

The following clinical measurements were taken by a single examiner at base line at the mid-buccal point of the involved tooth like Probing pocket depth (PPD), Gingival recession (GR), and Clinical attachment level (CAL). All the measurements were made with a William's periodontal probe (Hu-friedy).

Surgical procedure

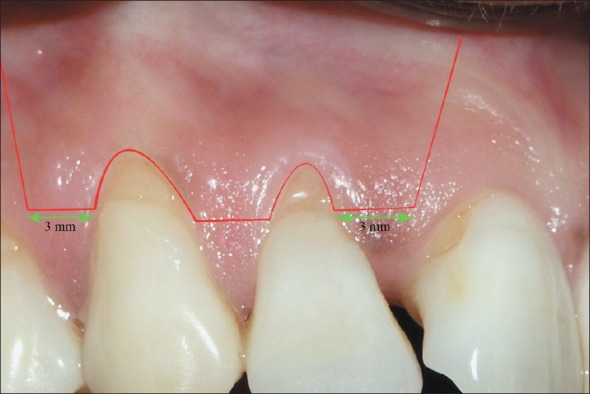

All surgical procedures were done by the same operator. First, an intracrevicular incision was made through the bottom of the crevice and horizontal incision was placed at the level of cementoenamel junction (CEJ) extending 3mm on either side of the involved tooth including their papilla. Two vertical incisions were placed from end point of horizontal incision to the alveolar mucosa to establish a trapezoidal flap [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Line diagram depicting the incisions

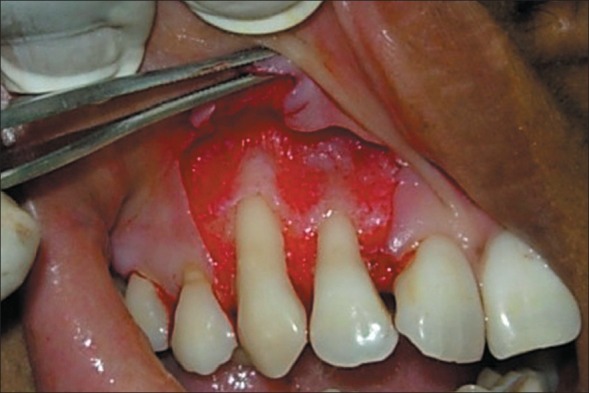

A Split thickness flap was elevated and all muscle interferences were eliminated in order to facilitate its coronal advancement. The remaining buccal soft tissue of the anatomic interdental papillae was deepithelized. The root surface was mechanically treated with Gracey curettes followed by conditioned with 1ml tetracycline hydrochloride solution for 3 minutes with subsequent rinsing with saline [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Split thickness trapezoidal flap is elevated

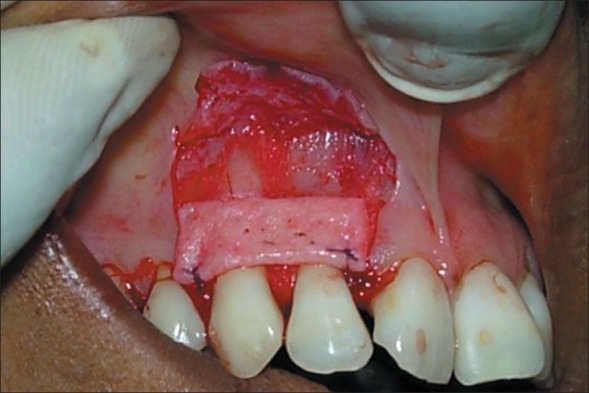

The Acellular dermal matrix allograft was aseptically rehydrated in sterile saline, according to the manufacturer's instructions. The graft was trimmed to a shape and size designed to cover the root surface upto CEJ and the surrounding bone. The basement membrane side was placed adjacent to bone and tooth, and the connective tissue side was placed facing the flap, as per previous studies.[23] The graft was sutured over the defect with 5-0 bioabsorbable sutures [Figure 4], followed by coronally advancement of the elevated flap and sutured. The area was reexamined to ascertain that none of the graft was visible and that the flap was sutured without tension [Figure 5]. A periodontal dressing was applied and was changed after a week.

Figure 4.

Initial stabilization of the Alloderm

Figure 5.

Coronal repositioning of the flap with complete closure

All patients were instructed to discontinue tooth brushing and to avoid trauma (or) pressure at the surgical site. A 0.12% chorhexidine digluconate mouth rinse was prescribed 2 times daily for 15 days, and analgesics and antibiotics were prescribed for 7 days. The patients were instructed to clean the surgical site with a cotton pellet soaked in a 0.12% chorhexidine digluconate solution 3 times daily for 10 days. After this period, they resumed mechanical tooth cleaning of the treated areas using a soft toothbrush and a careful roll technique.

The patients were recalled for plaque control prophylaxis after 2 and 4 weeks, followed by monthly upto 4 months; then every 3 months for 1 year.

Post operative measurements

The following post operative measurements were taken by the same examiner at the end of 3 months [Figure 6] and 12 months [Figure 7] period at the mid-buccal point of the involved tooth like Probing pocket depth (PPD), Gingival recession (GR), Clinical attachment level (CAL).

Figure 6.

Postoperative facial view at the end of 3rd month (compare with Figure 1)

Figure 7.

Postoperative facial view at the end of 12th month (compare with Figure 1)

Visual analog scale

In order to determine the colour match, the examiner fixed a ‘0-10 scale’ criteria, in that “0” score was no colour match and “10” score was absolute colour match. The scoring was done at the end of 3 months and 12 months in all the patients. In order to reduce observer bias, all scorings were made by an independent (second) periodontist. Every patient was given the same scale to rate his personal satisfaction with the colour match after treatment with Alloderm.

The results were analyzed statistically using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Paired t-test to estimate the mean root coverage and the color match.

RESULTS

At base line, a mean gingival recession was 2.50±1.09 mm, a mean probing pocket depth was 1.5±0.52mm and a mean clinical attachment level was 4.03±1.23mm, were recorded.

At the end of 3 months, the mean recession reduced from 2.50±1.09mm to 0.47±0.83mm, the probing pocket depth also reduced from 1.53±0.52mm to 1.27±0.37mm and clinical attachment level increased from 4.03±1.23mm to 1.70±0.86mm. At the end of 12 months, the mean recession depth was reduced from 2.50±1.09mm to 0.47±0.64mm, probing pocket depth reduced from 1.53±0.52mm to 1.30±0.41mm and clinical attachment level increased from 4.03±1.23mm to 1.50±0.85mm. On statistical analysis there was significant reduction in gingival recession and clinical attachment gain at 3 months, but there was no statistical significance improvement between 3 months to 12 months interval [Table 1].

Table 1.

Base line, end of 3rd month and 12th month parameters

The mean root coverage was 85.56±21.70 and 83.33±21.82% at the end of 3rd and12th months respectively. 9 out of 15 sites, 9 sites showed100% root coverage at the end of 12 months [Table 2].

Table 2.

Mean root coverage at end of 3rd and 12th month

The colour match of surgical site was examined at the end of 3 months and 12 months using the VAS. A score of 5.73±0.70 and 6.87±0.83 was obtained by the periodontist at the end of 3rd and 12th months; respectively .A statistically significant improvement was seen between the 3rd and 12th month scores. The individual patient's VAS score was 7.93±1.03 and 8.13±0.99 at the end of 3rd and 12th month, respectively. There was no significant difference between the 3rd and 12th month scores [Table 3].

Table 3.

VAS score (colour match)

DISCUSSION

Autogenous connective tissue grafts have been extensively used for root coverage procedures in teeth and implants.[28,29] However, the necessity for a second surgical site and volume of graft material available are potential drawbacks when connective tissue grafts are used in the treatment of multiple gingival recessions.

Harris's study promised that the use of acellular dermal matrix graft would improve the gingival color, reduce patient morbidity, provide uniform thickness of material, and eliminate the need for multiple surgeries because of unlimited availability.[30] He[31] further reported that the results obtained for the treatment of gingival recessions with Alloderm was comparable to that obtained with connective tissue grafts.

The surgical protocol used in this study closely followed that of previous studies done with Alloderm.[23] The uniformly good root coverage obtained in this study was in accordance with previous reports[32] and confirm Alloderm's potential as a reliable alternative to connective tissue graft.

Henderson et al,[33] reported that sites treated with Alloderm had resulted in defect coverage of 95% and ≥90% defect coverage was obtained 80% of the time. The mean root coverage in this study using Alloderm graft was 83%. Although this root coverage compares unfavorably with the previous report, 9 of the 15 sites exhibited complete (100%) root coverage. In two of the fifteen sites treated, only 60-70% coverage was obtained. The results of these two sites are largely responsible for the comparatively lesser degree of root coverage obtained in this study. As all surgical procedures were performed by a single operator, factors such as experience of the clinician and technique sensitivity are unlikely to be the cause of this relatively poor coverage in these two sites. There was no significant difference in patient related factors such as plaque control. These two sites, however, exhibited attachment loss greater than 6 mm and we suggest that the initial recession depth may have a greater influence on the treatment outcome than previously reported. There was no significant difference in any of the clinical parameters measured at the 3rd month and 12th month interval. The results clearly indicate that the recession coverage obtained with Alloderm may be successfully maintained over a prolonged period of time, provided patients exhibit good plaque control.

Borghetti and Gardella[34] documented that creeping attachment may continue for 1 year post operatively, when thick grafts were used. Henderson et al,[33] reported that no creeping attachment was achieved in Alloderm cases from 2 to 12 months. In this study, there was no statistically significant creeping attachment between the 3rd and 12th month interval. However, 4 patients did show a 1mm improvement in attachment from the 3rd to 12th month.

The ethnic south Indian population from where the patient pool was chosen is characterized by heavy melanin pigmentation of the gingiva and hard palate. Although racial difference in pigmentation of gingiva has been previously documented,[35] its influence on the colour match following soft tissue grafts has not been extensively studied. It has been reported that Alloderm did not support keratinization of the overlying epithelium;[36] however, its ability to induce melanization is not known.

In this study we observed that 1 month post operatively, all the gingival sites were devoid of pigmentation (data not shown). By the 3rd month; patients expressed high degree of satisfaction with the postoperative esthetics in the grafted sites on the VAS scores. It was noticeable though, that the periodontist's scores were consistently lower than that of the patient′s. The periodontist felt that the absence of normal pigmentation resulted in a mild pallor of the grafted sites, which detracted its colour match with the adjacent sites. Thus, patients seemed happier with the depigmented appearance than the periodontist, perhaps validating the necessity for a plethora of depigmentation procedures in-vogue.

By the 12th month; color match was better, as the grafted site showed almost complete pigmentation. As a result, the Periodontist's score at the end of one year was significantly higher than at the end of 3rd month.

Another interesting finding was that perception of the colour match did not strictly correlate with the degree of root coverage obtained, when the patients used the VAS. Conversely, the 9 sites that showed full coverage were scored higher by the periodontist.

The connective tissue has been known to influence epithelial behaviors through the secretion of paracrine growth factors such as as Keratinocyte growth factor (KGF),[37,38] direct contact and by communication through the basement membrane. Further, superficial connective tissue has been shown to have a greater influence on the epithelium when compared to the deep connective tissue.[39] Although melanization is principally an epithelium related event; factors such as Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) has been shown to influence melanin formation.[40]

The Acellular graft used in this study might have inhibited the effect of the underlying connective tissue due to the lack of cells necessary for the formation of the growth factors. We hypothesize that this is probably the reason for the slow melanin formation in the grafted site. As no histological examination could be made, a closer observation of the dynamics of melanization in Alloderm grafted sites was not possible. Further studies are required to elucidate the role of Alloderm in regulating melanin formation.

CONCLUSION

Connective tissue graft is gold standard for treatment of gingival recession but the disadvantages are the second surgical site and inadequate graft availability. Hence acellular dermal matrix graft (alloderm) is the most successful and predictable procedure in the management of gingival recession due to adequate root coverage and good colour match, without the need for second surgical site.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Sullivan HC, Atkins JH. Free autogenous gingival grafts I.Principles of successful grafting. Periodontics. 1968;6:121–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sullivan HC, Atkins JH. Free autogenous gingival grafts III.Utilization of grafts in the treatment of gingival recession. Periodontics. 1968;6:152–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller PD., Jr Root coverage using the free soft tissue autograft following citric acid application part III.A successful and predictable procedure in areas of deep-wide recession. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1985;5:14–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grupe H, Warren R. Repair of gingival defects by sliding flaps operation. J Periodontal. 1956;27:290–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caffesse RG, Guinard EA. Treatment of localized gingival recession part I. Lateral sliding flap. J Periodontal. 1978;49:351–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1978.49.7.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caffesse RG, Guinard EA. Treatment of localized gingival recession part IV. Results after three years. J Periodontal. 1980;51:167–70. doi: 10.1902/jop.1980.51.3.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris RJ, Harris AW. The coronally positioned pedicle graft with indaid margins.A predictable method of obtaining root coverage of shallow defects. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1994;14:229–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Treatment of gingival recession using a collagen membrane with or without the use of demineralized freeze-dried bone allograft for space maintenance. J Periodontal. 2004;75:210–20. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen DW, Ross SE. The double papilla repositioned flap in periodontal therapy. J Periodontal. 1968;39:65–70. doi: 10.1902/jop.1968.39.2.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karring T, Lang NP, Loe H. The role of gingival connective tissue in determining epithelial differentiation. J Dent Res. 1972;51:1303–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1975.tb00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edel A. Clinical evaluation of free connective tissue grafts used to increase the width of keratinized gingival. J Clin Periodontal. 1974;1:185–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1974.tb01257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langer B, Langer L. Sub-epithelial connective tissue graft technique for root coverage. J Periodontal. 1985;56:715–20. doi: 10.1902/jop.1985.56.12.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raetzke PB. Covering localized areas of root exposures employing the envelope technique. J Periodontal. 1985;56:397–02. doi: 10.1902/jop.1985.56.7.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson SW. The subepithelial connective tissue graft, a bi-laminar reconstructive procedure for root coverage of denuded root surfaces. J Periodontal. 1987;58:94–102. doi: 10.1902/jop.1987.58.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouchard P, Etienne D, Ouhayoun JP, Nilvens R. Sub-epithelial connective tissue graft in the treatment of gingival recession - A comparative study of 2 procedures. J Periodontal. 1994;65:929–36. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.10.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris RJ. The connective tissue with partial thickness double pedicle graft.The results of 100 consecutively treated defects. J Periodontal. 1994;65:448–61. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.5.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruno JF. Connective tissue graft technique assuring wide root coverage. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1994;14:127–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hurzeler MB, Weng D. A single incision technique to harvest subepithelial connective tissue graft from the palate. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1999;19:279–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yukna RA, Tow HD, Carroll PB. Evaluation of the use of freeze-dried skin allografts in the treatment of human mucogingival problems. J Periodontal. 1977;48:187–93. doi: 10.1902/jop.1977.48.4.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Callan PP. Use of acellular dermal matrix allograft material in dental implant treatment. Dent Surg Products. 1996;9:14–7. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silverstein LH, Callan DP. An acellular dermal matrix allograft substitute for palatal donor tissue. Postgrad Dent. 1996;3:14–21. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Batista EL, Jr, Batista FC, Novars AB., Jr Management of soft tissue ridge deformities with acellular dermal matrix.Clinical approach and outcome after 6 months of treatment. J Periodontal. 2001;72:265–73. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.2.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris RJ. Root coverage with a connective tissue with partial thickness double pedicle graft and an acellular dermal matrix: A clinical and histlogical evaluation of a case report. J Periodontal. 1998;69:1305–11. doi: 10.1902/jop.1998.69.11.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aichelmann-Reidy ME, Yukna RA, Mayer ET. Acellular dermal matrix used for root coverage. J Periodontal. 1999;70:223. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris RJ. A comparative study of root coverage obtained with an acelluar dermal matrix versus a connective tissue graft. Results of 107 recession defects in 50 consecutively treated patients. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2000;20:51–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karadottir H, Lenoir L, Barbierato B, Bogle M, Riggs M, Sigurdsson T, et al. Pain experienced by patients during periodontal maintenance treatment. J Periodontal. 2002;73:536–42. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.5.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller PD., Jr A classification of marginal tissue recession. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1985;5:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borghetti A, Louise F. Controlled clinical evaluation of the sub pedicle connective tissue graft for the coverage of gingival recession. J Periodontal. 1994;65:1107–12. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.12.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bouchaed P, Etienne D, Ouhayoun JP, Nilveus R. Sub epithelial connective tissue grafts in the treatment of gingival recession – A comprehensive study of 2 procedures. J Periodontal. 1994;65:929–36. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.10.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aichelmann-Reidy ME, Yukna RA, Evans GH, Nasr HF, Mayer ET. Clinical evaluation of acellular allograft dermis for the treatment of human gingival recession. J Periodontal. 2001;72:998–1005. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.8.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris RJ. Short and long term comparison of root coverage with an acellular dermal matrix and subepithelial graft. J Periodontal. 2004;75:734–43. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.5.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harris RJ. Acellular dermal matrix used for root coverage, an 18 month follow up observation. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2002;22:156–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Henderson RD, Greenwell H. Predictable multiple site root coverage using an acellular dermal matrix allograft. J Periodontal. 2001;72:571–82. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.5.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borghetti, Gardella JP. Thick gingival auto graft for the coverage of gingival recession, clinical evaluation dentistry. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1990;10:216–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dummett CO. Physiological pigmentation of the oral and cuttanuous tissue in the Negro. J Dent Rest. 1946;25:422. doi: 10.1177/00220345460250060201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harris RJ. Gingival augmentation with a Acellular Dermal Matrix; Human histological evaluation of a case - placement of graft on bone. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2001;21:69–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Werner S. Keratinocyte growth factor: A unique player in epithelial repair processes. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1998;9:153–65. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(98)00010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rubin JS, Bottaro DP, Chadid M, Miki T, Ron D, Cheon G, et al. Keratinocyte growth factor. Cell Biol Int. 1995;19:399–411. doi: 10.1006/cbir.1995.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mackenzie IC, Tonetti MS. Formation of normal gingival epithelial phenotypes. J Periodontal. 1995;66:933–43. doi: 10.1902/jop.1995.66.11.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanaie AR, Firth JD. Keratinocytes growth factor (KGF)-1 and 2 protein and gene expression in human gingival fibroblasts. J Periodontal Res. 2002;37:66–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]