Abstract

Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome is a very rare syndrome of autosomal recessive inheritance characterized by palmar-plantar hyperkeratosis and early onset of a severe destructive periodontitis leading to premature loss of both primary and permanent dentitions. Various etiopathogenic factors are associated with the syndrome; but a recent report has suggested that the condition is linked to mutations of the cathepsin C gene. Two cases of Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome in the same family, having all of the characteristic features are presented. An 11-year-old girl, and her elder sister, a 13-year-old girl complained of loose teeth and discomfort in chewing along with recurrently swollen and friable gums. Both patients also had premature shedding of their deciduous teeth. The family history revealed consanguineous marriage of the parents. Both patients presented with persistent thickening, flaking and scaling of the skin of palms and soles. Severe generalized periodontal destruction with mobility of teeth was evident on intraoral examination; orthopantomograph examination showed severe generalized loss of alveolar bone in both the patients.

Keywords: Hyperkeratosis, Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome, periodontitis

INTRODUCTION

Papillon–Lefèvre syndrome (PLS) is characterized by hyperkeratosis of hands and feet and by a generalized aggressive periodontitis in both the primary and the permanent dentition.[1] The syndrome is a rare autosomal recessive trait with an estimated prevalence of one to four cases per million persons. Parental consanguinity is demonstrated in 20% to 40% of the cases.[1] Calcification of the falx cerebri and the choroid plexus, and retardation of somatic development is often an associated feature.[2–4] It has been suggested that 20–25% of such patients show an increased susceptibility to infections,[1,3,5] of which otitis media is a common example.[6] The recently identified genetic defect in PLS has been mapped to chromosome 11q14–q21, which involves mutations of cathepsin C.[7,8] Studies in PLS patients have shown more than 90% reduction in cathepsin C activity.[8,9] The cathepsin C gene encodes a cysteine-lysosomal protease also known as dipeptidyl-peptidase I, which functions to remove dipeptides from the amino terminus of the protein substrate. It also has an endopeptidase activity. The cathepsin-C gene is expressed mainly in the epithelial regions such as palms, soles, knees, and keratinized oral gingiva. These are generally the areas that are mostcommonly affected by PLS. This gene is also expressed at high levels in various immune cells including polymorphonuclear leukocytes, macrophages, and their precursors. All PLS patients are homozygous for the cathepsin-C mutations inherited from a common ancestor. Parents and siblings, heterozygous for cathepsin C mutations do not show either the palmoplantar hyperkeratosis or severe early onset periodontitis characteristic of PLS.[7] Despite these advances in characterizing the genetic basis of the syndrome, the pathogenic mechanisms leading to the periodontal involvement remain elusive. An impaired chemotatic and phagocytic function of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) and impaired reactivity to T- and B-cell mitogens has been described in many reports.[10–17] Periodontal effects appear almost immediately after tooth eruption when gingiva becomes erythematous and oedematous. Plaque accumulates in the deep crevices and halitosis can ensue. The primary incisors are usually affected first and can display marked mobility by the age of three years. By the age of four or five years, all the primary teeth may have exfoliated.[1,4] Treatment with oral hygiene instructions, scaling, and root planing has been reported unsuccessful.[18–20] Non-surgical treatment combined with the use of systemic antibiotics[21–24] and additional periodontal surgery[23,25] has also been reported to fail. Following the deciduous tooth loss, the gingival appearance resolves and may well return to health only for the process to be repeated as the permanent dentition starts to erupt.[1] The majority of teeth are lost by the age of 14–15 years.[1,4,5] There is a dramatic alveolar bone destruction, often leaving the jaws atrophied. Patients are often edentulous at an early age.[5] We hereby report two cases of Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome in the same family, having all of the characteristic features of the syndrome.

CASE REPORTS

Case history

An 11-year-old girl (Case 1), and her elder sister, a 13-year-old girl (case 2), reported to the Department of Periodontics, Govt. Dental College and Hospital, Srinagar, with complaints of loose teeth and discomfort in chewing along with recurrently swollen and friable gums. Both patients also complained of persistent thickening, flaking and scaling of the skin of palms and soles. Both patients also had premature shedding of their deciduous teeth. The remainder of their past medical history was unremarkable. The family history revealed consanguineous marriage of the parents. The parents and other family members were not affected. Pregnancy and delivery were normal.

General and extra-oral examination

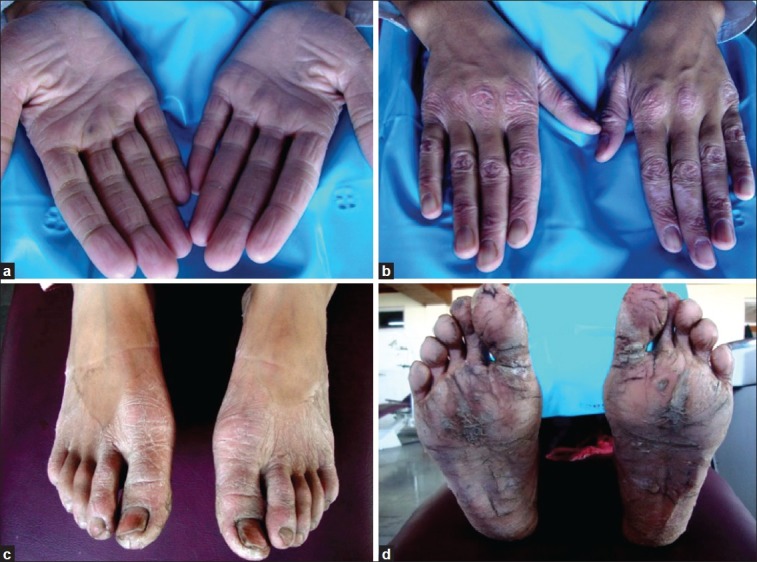

Both the patients had overall normal physical and mental development. Extra-oral examination of case 1 revealed yellowish, keratotic, confluent plaques affecting the skin of her palms and soles. Her nails and hair were normal. Extra-oral examination of case 2 revealed symmetric, well-demarcated, yellowish, keratotic, confluent plaques affecting the skin of her palms and soles and extending onto the dorsal surfaces. Her nails were discolored, but her hair was normal. Well-circumscribed, psoriasiform, erythematous, scaly plaques were present on the knees bilaterally [Figures 1 and 2].

Figure 1.

(a) Case 1 presenting with yellowish, keratotic, confluent plaques affecting the skin of palmar surfaces of hands; (b) Case 1 presenting with keratotic plaques on the dorsal surfaces of hands; (c) Keratotic plaques affecting the dorsal surface of feet; (d) Several confluent plaques on soles

Figure 2.

(a) Case 2 presenting with keratotic, confluent plaques affecting the skin of palmar surfaces of hands; Keratotic plaques affecting the dorsal surfaces of hands; (c) Plaques affecting the dorsal surfaces of feet; (d) Several confluent plaques affecting the soles; (e) In case 2, well-circumscribed, erythematous, scaly plaques on the knees bilaterally are also noticed

Intraoral examination

On intraoral examination of case 1, upper left permanent central incisors, lower left permanent central and lateral incisors were missing. Severe gingival inflammation, abscess formation, and deep periodontal pockets were noticed. Severe mobility affecting all the teeth, with heavy deposits of plaque and calculus and halitosis were also present [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Intraoral examination of case 1 showing missing upper left permanent central incisor, lower left permanent central and lateral incisors and permanent right lower central incisor. Severe gingival inflammation, abscess formation, and deep periodontal pockets were noticed. Severe mobility affecting all the teeth, with heavy deposits of plaque and calculus and halitosis, were also present

Intraoral examination of case 2 showed deep periodontal pockets, gingival inflammation, and mobility of lower anterior teeth [Figure 4]. All primary teeth were exfoliated and no tooth was missing.

Figure 4.

Intraoral examination of case 2 showing deep periodontal pockets, gingival inflammation, and mobility of lower anterior teeth

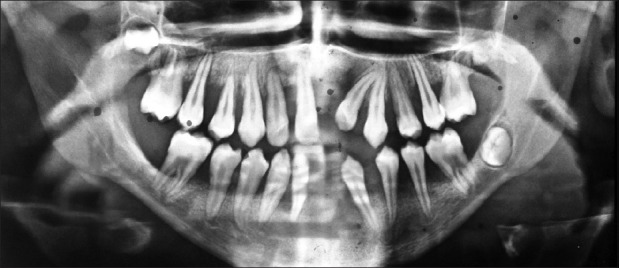

Radiographic finding

Orthopantomographic examination of case 1 showed severe generalized destruction of alveolar bone. The mandibular right first molar was almost entirely out of its socket and was almost without bone support [Figure 5]. Case 2 showed generalized loss of alveolar bone [Figure 6].

Figure 5.

OPG of case 1 showing severe generalized destruction of alveolar bone. The mandibular right first molar was almost entirely out of its socket with not much bone support

Figure 6.

OPG of case 2 showing generalized destruction of alveolar bone. See the severe periodontal destruction in upper right first molar

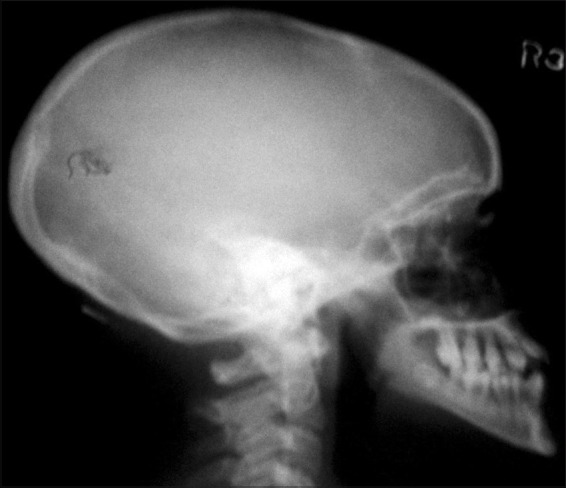

On lateral skull radiograph, there was no evidence of intracranial calcification in both the patients [Figure 7].

Figure 7.

Lateral skull view of case 1 showing no evidence of intracranial calcification

Laboratory investigation

Laboratory investigation was carried out, which included hematological and biochemical assessment. The results were within normal limits.

Diagnosis

In view of the above findings, the cases were diagnosed as PLS.

DISCUSSION

PLS can adversely affect growing children psychologically, socially, and esthetically. Hence, an early dental evaluation and parental counseling as a part of preventive dental treatment is essential for providing complete psychosocial rehabilitation for PLS children; a multidisciplinary approach may improve the prognosis and quality of life of these children. Although the exact pathogenesis of this syndrome remains relatively obscure; immunologic, microbiologic, and genetic bases have been proposed. Microbiological studies have demonstrated Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Fusobacterium nucleatum, and Treponema denticola organisms, suggesting that many pathogens may be involved in the disease process. Previous case reports and studies have reported that A. actinomycetemcomitans play a significant role in the pathogenesis and progression of the rapid periodontal breakdown seen in PLS.[5,12,26,27] A decreased chemotactic and phagocytic function of neutrophils has also been suggested.[28] Recent research has shown that inactivation of the cathepsin C gene is responsible for the abnormalities in skin development and periodontal disease progression.[29] These various factors contributing to the etiopathogenesis of this disease ensure that successful treatment of the rapid periodontal destruction seen in this syndrome remains a challenging problem. In our cases, genetic testing could not be performed to identify the gene mutation because of the low economic status of the parents, but the dermatological, periodontal, and radiological features strongly suggested the diagnosis of PLS. Moreover, consanguineous descent has been described for this syndrome,[29] and the two cases reported here were also associated with consanguinity of parents. Phenotypically, the parents were healthy and there was no family history of the disease, suggesting an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance.

The differential diagnoses include Haim-Munk syndrome and hypophosphatasia. Haim-Munk syndrome has been described as an autosomal-recessive genodermatosis characterized by congenital palmoplantar keratoderma and progressive early-onset periodontitis. Haim-Munk syndrome also exhibits arachnodactly, acroosteolysis, atrophy of nails, and deformity of the phalanges in the hands. None of these features were found in the present cases. In hypophosphatasia, deficiency of alkaline phosphatase activity is seen,[30] but in our cases, the values were within normal limits and therefore this differential diagnosis could be excluded.

A definite treatment regime has not been yet reported; however, to control periodontal destruction, several treatment modalities have been suggested, e.g., conventional periodontal therapy, oral hygiene instructions, and systemic antibiotics.[27] Further research is required for defining a treatment strategy that can save the smiles of these children. Identification of specific periodontal pathogens and antibiotic therapy appropriate to these microorganisms, along with extraction of severely periodontally compromised teeth can prolong the viability of non-affected teeth. Newer therapeutic modalities involve the use of oral retinoids, such as acitretin, etretinate, and isotretinoin.[12,31] It is reported that etretinate and acitretin modulate the course of periodontitis and preserve the teeth.[31] A course of antibiotics should be tried to control the active periodontitis in an effort to preserve the teeth and to prevent bacteremia and subsequently pyogenic liver abscess.[32] The risk of pyogenic liver abscess should be kept in mind in evaluating these patients when they present with fever of unknown origin.[32] In the future, stem cell therapy can be expected to open up new vistas in the dental treatment of such children.

CONCLUSION

PLS threatens children and their parents with the prospect of edentulism if left untreated. Hence, early diagnosis and intervention is essential. For edentulous patients, oral rehabilitation is required; which includes partial or complete denture prosthetic replacement (according to the age of the patient). Osseointegrated implants are an option for the future and can have a great impact psychosocially by restoring esthetics as well as function.

The periodontist is the first member of the health team to see and treat the patients afflicted with such unusual syndromes such as PLS, and therefore, greater awareness of this syndrome will be helpful in identifying more cases for further study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Papillon MM, Lefèvre P. Deux cas de keratodermie palmaire et plantaire symétrique familiale (maladie de Meleda) chez le frere et la soeur. Coexistence dans les deus cas alterations dentaires grabes. Bulletin de la Soceite Francaise de Dermatologie et de Syphiligraphie. 1924;31:82–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorlin RJ, Cohen MM, Levin LS. Syndromes of the Head and Neck. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Pres; 1990. pp. 853–5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hall RK, editor. Paediatric Orofacial Medicine and Pathology. 1st ed. London: Chapman and HallMedical; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kressin S, Herforth A, Preis S, Wahn V, Lenard HG. Papillon–Lefèvre syndrome – successful treatment with a combination of retinoid and concurrent systematic periodontal therapy: Case reports. Quintessence Int. 1995;26:795–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wara-Aswapati N, Lertsirivorakul J, Nagasawa T, Kawashima Y, Ishikawa I. Papillon–Lefèvre syndrome: Serum immunoglobulins G (IgG) subclass antibody response to periodontopathic bacteria. A case report. J Periodontol. 2001;72:1747–54. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.12.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lundgren T, Crossner CG, Twetman S, Ullbro C. Systemic retinoid medication and periodontal health in patients with Papillon–Lefèvre syndrome. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:176–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1996.tb02073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hart TC, Hart PS, Bowden DW, Michalec MD, Callison SA, Walker SJ, et al. Mutation of the cathepsin C gene are responsible for Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome. J Med Genet. 1999;36:881–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toomes C, James J, Wood AJ, Wu CL, McCormick D, Lench N, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the cathepsin C gene result in periodontal disease and palmoplantar keratosis. Nat Genet. 1999;23:421–4. doi: 10.1038/70525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hart PS, Zhang Y, Firatli E, Uygur C, Lotfazar M, Michalec MD, et al. Identification of cathepsin C mutationsin ethnically diverse Papillon- Lefèvre syndrome patients. J Med Genet. 2000;37:927–32. doi: 10.1136/jmg.37.12.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D’Angelo A, Margiotta V, Ammatuma P, Sammartano F. Treatment of prepubertal periodontitis. A case report and discussion. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;19:214–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1992.tb00642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown RS, Hays G, Flaitz CM, O’Neill PA, Abramovitch K, White RR. A possible late onset variation of Papillon–Lefèvre syndrome: Report of 3 cases. J Periodontol. 1993;64:379–86. doi: 10.1902/jop.1993.64.5.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tinanoff N, Tempro P, Maderazo EG. Dental treatment of Papillon–Lefèvre syndrome: 15 year followup. J Clin Periodontol. 1995;22:609–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1995.tb00813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.FQratlQ E, Gurel N, Efeoglu A, Badur S. Clinical and immunological findings in 2 siblings with Papillon–Lefèvre syndrome. J Periodontol. 1996;67:1210–5. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.11.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghaffer KA, Zahran FM, Fahmy HM, Brown RS. Papillon–Lefèvre syndrome. Neutrophil function in 15 cases from 4 families in Egypt. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radio Endod. 1999;88:320–5. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(99)70036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu R, Cao C, Meng H, Tang Z. Leukocyte function in 2 cases of Papillon–Lefèvre syndrome. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:69–73. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2000.027001069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyberg T. Immunological and metabolic studies in two siblings with Papillon–Lefèvre syndrome. J Periodontol Res. 1982;17:563–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1982.tb01177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schroeder HE, Seger RA, Keller HU, Rateitschak- Plüss EM. Behavior of neutrophilic granulocytes in a case of Papillon–Lefèvre syndrome. J Clin Periodontol. 1983;10:618–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1983.tb01300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hathway R. Papillon–Lefèvre syndrome. Br Dent J. 1982;153:370–1. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4804940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bimstein E, Lustmann J, Sela MN, Neriah ZB, Soskolne WA. Periodontitis associated with Papillon– Lefèvre syndrome. J Periodontol. 1990;61:373–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.1990.61.6.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hattab FN, Rawashdeh MR, Yassin OM, Al-Momani AS, Al-Ubosi MM. Papillon–Lefèvre syndrome: a review of the literature and a report of 4 cases. J Periodontol. 1995;66:413–20. doi: 10.1902/jop.1995.66.5.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rateitschak-Plüss EM, Schroeder HE. History of periodontitis in a child with Papillon–Lefèvre syndrome. J Periodontol. 1984;55:35–46. doi: 10.1902/jop.1984.55.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glenwright HD, Rock WP. Papillon–Lefèvre syndrome. A discussion of aetiology and a case report. Br Dent J. 1990;168:27–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4807059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bullon P, Pascual A, Fernandez-Novoa MC, Borobio MV, Muniain MA, Camacho F. Late onset Papillon– Lefèvre syndrome. A chromosomic, neutrophil function and microbiological study? J Clin Periodontol. 1993;20:662–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1993.tb00712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Vree H, Steenackers K, de Boever JA. Periodontal treatment of rapid progressive periodontitis in 2 siblings with Papillon–Lefèvre syndrome: 15- years follow-up. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:354–60. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2000.027005354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Dyke TE, Taubman MA, Ebersole JL, Haffajee AD, Socransky SS, Smith DJ, et al. The Papillon–Lefèvre syndrome: Neutrophil dysfunction with severe periodontal disease. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1984;31:419–29. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(84)90094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sagllie FR, Marfany A, Camargo P. Intragingival occurrence of Actinobacilllus actinomycetemcomitans and Bacterioides gingivalis in active destructive periodontal lesions. J Periodontol. 1988;59:259–65. doi: 10.1902/jop.1988.59.4.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stabholz A, Taichman S, Soskolne WA. Occurrence of actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and anti-leukotoxin antibodies in some members of an extended family affected by Papilon-Lefèvre syndrome. J Periodontol. 1995;66:653–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.1995.66.7.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Firatli E, Gurel N, Efeoglu A, Badur S. Clinical and immunological findings in 2 siblings with Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome. J Periodontol. 1996;67:1210–5. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.11.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hart TC, Hart PS, Bowden DW, Michalec MD, Callison SA, Walker SJ, et al. Mutations of the cathepsin C gene are responsible for Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome. J Dent Res. 2004;83:368–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Preus H, Gjermo P. Clinical management of prepubertal periodontitis in 2 siblings with Papillon - Lefèvre syndrome. J Clin Periodontol. 1987;14:156–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1987.tb00959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gelmetti C, Nazzaro V, Cerri D, Fracasso L. Long term preservation of permanent teeth in a patient with Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome treated with etretinate. Pediatr Dermatol. 1989;6:222–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1989.tb00822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Almuneef M, Al Khenaizan S, Al Ajaji S, Al-Anazi A. Pyogenic liver abscess and Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome: Not a rare association. Pediatrics. 2003;111:85–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.1.e85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]