Abstract

Background

Disfiguring dermatoses may have a significant impact on patients’ quality of life, namely on their relationship with others, self image, and self esteem. Some previous studies have suggested that corrective foundation can improve the quality of life (QOL) of patients with facial dermatoses; in particular, in patients with acne vulgaris or pigmentary disorders.

Objective

The aim of this prospective study was to evaluate the impact of the skin conditions of patients with various skin diseases affecting their face (scars, acne, rosacea, melasma, vitiligo, hypo or hyperpigmentation, lentigines, etc) on their QOL and the improvement afforded by the use of corrective makeup for 1 month after being instructed on how to use it by a medical cosmetician during an initial medical consultation.

Methods

One hundred and twenty-nine patients with various skin diseases affecting the patients’ face were investigated. The patients were instructed by a cosmetician on how to use corrective makeup (complexion, eyes, and lips) and applied it for 1 month. The safety of the makeup application was evaluated and the QOL was assessed via a questionnaire (DLQI) and using a 10-cm visual analog scale (VAS) completed before the first application and at the final visit. The amelioration of their appearance was documented by standardized photography.

Results

No side effects occurred during the course of the study. A comparison of the standardized photographs taken at each visit showed the patients’ significant improvement in appearance due to the application of corrective makeup. The mean DLQI score dropped significantly from 9.90 ± 0.73 to 3.49 ± 0.40 (P < 0.0001).

Conclusion

Our results suggest that dermatologists should encourage patients with disfiguring dermatoses to utilize appropriate and safe makeup to improve their appearance and their QOL. Corrective makeup can also complement the treatment of face dermatological diseases in order to improve patient’s adherence.

Keywords: corrective makeup, disfiguring dermatoses, quality of life, scars, acne, rosacea, melasma, vitiligo

Introduction

Psychological impairments can be caused by dermatological diseases, especially disfiguring diseases such as vitiligo and other pigmentary disorders, vascular malformations, acne, and scars from surgery or trauma. They may have a significant impact on a patient’s quality of life (QOL), namely on their relationship with others, self image, and self esteem and can cause depression and/or emotional distress.1–3 These psychosocial aspects have important implications for the optimal management of patients by dermatologists: poor patient satisfaction leading to poor adherence to treatment with consequently poor health outcomes.4

Numerous studies have described cosmetic camouflage therapies,5 and their ability to restore the self esteem of the disfigured patients.6–8 Some others have also demonstrated that corrective makeup or cosmetic camouflage can result in the improvement of QOL in patients with pigmentary disorders and in particular vitiligo,8–12 acne,2,12–14 scars,11 vascular disorders,11 or after chemotherapy.15 These studies generally involved few patients and used mainly cosmetic foundation. Furthermore, instructions for using these products were not systematically given by a cosmetician, and some data have suggested that this last point can influence patients’ QOL.13 Despite all these data, dermatologists sometimes discourage patients from applying makeup since decorative cosmetics are considered one of the aggravating factors of their dermatoses. Based on these observations, we wanted to verify the impact of the skin conditions of patients with various skin diseases affecting their face (eg, scars, acne, rosacea, melasma, vitiligo, hypo or hyperpigmentation, lentigines, etc) on their QOL and on their social behavior and the improvement afforded by the use of corrective makeup (complexion, eyes, and lips) after being instructed on how to use it by a medical cosmetician during a medical consultation.

Patients and methods

Study design and population

One hundred and twenty-nine patients over the age of 18 years, with disfiguring dermatoses affecting the face were enrolled by dermatologists in this international, multicenter, open non-comparative prospective study. All of them gave their written consent to participate. During an initial medical consultation (Vi), including an initiation by a medical cosmetician to non-comedogenic corrective makeup (complexion, eyes, and lips) (La Roche-Posay Pharmaceutical Laboratories, Asnières, France), each volunteer underwent (before makeup) a dermatological examination and completed a QOL questionnaire. Patients continued using the recommended and given makeup for 2–4 weeks at least until the final visit (Vf). During the final consultation, the patient came back with makeup done by him/her and answered questions about product usage and agreement, cosmetic acceptability, and tolerance, and completed the QOL questionnaire. The amelioration of the appearance of volunteers was documented by standardized photography.

Clinical evaluation

The dermatologists described the disfiguring dermatose including the percentage of the face area affected. The patients’ history of depression was researched and the investigators evaluated their depression with simplified scale: “none/weak/moderate/serious”. The QOL questionnaire completed by the patient derived from the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI),16 and consists of ten items covering symptoms and feelings, daily activities, leisure, work or school, personal relationships, and treatment. Each question has six alternative responses: “not relevant”, “not at all”, “a little”, “moderately”, “a lot”, and “very much”, with corresponding scores of 0, 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. The total score is calculated by adding the score of each question and total scores ranged from a minimum of “0” to a maximum of “40”, with higher scores representing greater impairment of QOL. Furthermore, a global evaluation of the QOL was performed using a 10-cm visual analog scale (VAS).

Statistics

Data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) and percentages (%). For each score, descriptions were at the same time global and stratified; they mentioned systematically the number, maximum and minimum, median, standard deviation, and mean. We quantified changes in longitudinal data: we described the percentages of responders (% of cases improved at the final visit by comparison with the initial visit), and the percentages of improvement (individual differences [Vf − Vi] expressed as percentage of the individual value at Vi).

We used the Wilcoxon non-parametric test and a general linear model for repeated measures. The differences were considered as being statistically discernible with an alpha risk value of 5% for the efficacy and an alpha risk value of 1% for the distances from normality. The data were analyzed using SPSS software (v 15; SPSS France, Paris, France).

Results

Characterization of the cohort

The characteristics and diagnoses of enrolled patients are summarized in Table 1. The patients suffering from acne and the resulting scars had a mean condition duration of less than 10 years, while patients suffering from pigmentary or vascular disorders had a mean condition duration of more than 15 years. The importance of the face area affected was smaller for patients with scars (85% with less than 25% of the face affected) and larger for those suffering from vascular dermatoses (40% with less than 25% of the face affected). For the other groups, around 50% of patients presented less than 25% of the face affected. Patients with pigmentary disorders (including vitiligo and melasma) were significantly more depressed (36%) than those affected by other diseases (acne, vascular disorders, or scars, with 17%, 10%, and 19% of depressed patients, respectively, as judged by dermatologists), without any link with the importance of the face area affected or the duration of the disease. At the initiation of the study (Vi), 60% of patients were under medical treatment for their dermatoses (which was kept the same throughout the study) and 74% usually used makeup to camouflage their lesions. Patients who did not use makeup, did so due to lack of product knowledge (53%), fear of worsening their condition (29%), or because they did not feel the need (9%). During the makeup consultation with the medical cosmetician, 100% of patients used products for complexion (79% foundation, 80% corrective pen-brush, 26% powder, 63% blush), 81.4% eye products (72% eyeshadow, 54% pencil, 5% liner, and 85% mascara), and 78.3% lips products (54% pencil and 84% lipstick). After they applied the makeup, 99% of patients thought that it made a noticeable improvement of their face, 94% thought that the cosmetic application was easy to do, and 100% said that they would use the recommended products (88% complexion, 63% eye, and 38% lip products). Sixty-five percent indicated that they would wear makeup every day, 12% when they work, and 23% when they leave home; lastly, 88% thought that they would feel more comfortable in their relationship with others.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics | % | Diagnoses | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Acne and the resulting scars | 22 | |

| Male | 5 | Pigmentary disorders (including vitiligo, melasma) | 28 |

| Female | 95 | Vascular disorders (including rosacea, couperosis, angioma) | 23 |

| Marital status | Other | 8 | |

| Married | 53 | Age (years)* | 42.8 ± 1.4 |

| Without children | 59 | Duration of disease (years)* | 12.7 ± 1.2 |

| Skin type | Face area affected | ||

| Light (type I to III) | 91 | Slight (<5% of the face) | 24 |

| Dark (type IV to V) | 9 | Moderate (>10% to <25% of the face) | 33 |

| Depressive profile | Very important (>50% of the face) | 9 | |

| No | 73 | Treatment | |

| Unknown | 5 | Under treatment (local or systemic) | 60 |

| If yes, intensity | Without treatment | 40 | |

| Light | 31 | ||

| Moderate | 55 | ||

| Severe | 10 | ||

| Unknown | 4 | ||

| Makeup user | |||

| Yes | 74 | ||

| No | 26 |

Note:

Data expressed as mean ± SEM.

Tolerability and cosmetic acceptability of the makeup products

At the final consultation (Vf), which was an average of 33 days after the initial visit, 99% had used the recommended makeup products (98% complexion, 81% eye, and 72% lip products), although 20% had encountered some makeup difficulties. Seventy-five percent thought that makeup had improved their relationships with their family, at work (94%), or in public places (95%). Ninety-five percent tolerated the recommended products well (only some tingling [n = 5] or burning [n = 2] sensations were noticed).

Quality of life assessment

The overall QOL scores obtained at baseline (Vi) and at the final (Vf) visit for the different aspects of life affected by the disfiguring dermatoses are presented in Table 2. The global QOL score at baseline was 9.90 ± 0.73 (scale from 0 to 40) indicating a moderate effect on patients’ lives.16 This was confirmed by the result of the QOL–VAS (0–10) of 5.12 ± 0.22. The most significant impact was on feelings (question 2) and the least significant on work or school (question 7, with only six positive answers). Patients with scars were slightly more affected in their life than the other ones (mean VAS score of 5.52 versus 5.35 for vascular disorders, 4.96 for pigmentary disorders, and 4.91 for acne) despite the involved area being smaller. Depressed patients were also slightly more affected in their life than the non-depressed ones (5.82 versus 4.89).

Table 2.

Scores of quality of life items at baseline (Vi) and at the end of the study (Vf)

| Baseline (Vi) | Final (Vf) | R (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Over the last week, how itchy, sore, painful, or stinging has your skin been? | 1.01 ± 0.10 | 0.39 ± 0.07* | 42 |

| 2. Over the last week, how embarrassed or self conscious have you been because of your disfiguring lesions? | 2.11 ± 0.11 | 0.74 ± 0.08* | 74 |

| 3. Over the last week, how much have your disfiguring lesions interfered with you going shopping or looking after your home or garden? | 1.30 ± 0.11 | 0.37 ± 0.07* | 55 |

| 4. Over the last week, how much have your disfiguring lesions influenced the clothes you wear? | 0.95 ± 0.12 | 0.36 ± 0.07* | 33 |

| 5. Over the last week, how much have your disfiguring lesions affected any social or leisure activities? | 1.33 ± 0.12 | 0.52 ± 0.08* | 50 |

| 6. Over the last week, how much have your disfiguring lesions made it difficult for you to do any sport? | 0.64 ± 0.10 | 0.16 ± 0.05* | 29 |

| 7. Over the last week, have your disfiguring lesions prevented you from working or studying? | 0.19 ± 0.07 | 0.06 ± 0.04 | 4 |

| If “No”, over the last week how much have your disfiguring lesions been a problem at work or studying? | 0.65 ± 0.08 | 0.19 ± 0.04* | 33 |

| 8. Over the last week, how much have your disfiguring lesions created problems with your partner or any of your close friends or relatives? | 0.85 ± 0.10 | 0.3 ± 0.06* | 36 |

| 9. Over the last week, how much have your disfiguring skin lesions caused any sexual difficulties? | 0.37 ± 0.08 | 0.13 ± 0.04** | 17 |

| 10. Over the last week, how much of a problem has the treatment for your skin been, for example by making your home messy, or by taking up time? | 0.50 ± 0.08 | 0.26 ± 0.05* | 23 |

| Global score (0–40) | 9.90 ± 0.73 | 3.49 ± 0.40* | 81 |

Notes: N = 129; score (0–4) for each question. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. R = responsiveness or percentage of responders. Comparison of mean scores obtained at the baseline and at the final visit (*P ≤ 0.0001; **P = 0.0006).

After 1 month of makeup use, the mean global QOL score dropped significantly from 9.9 to 3.5 (P < 0.0001) and the mean VAS score from 5.12 to 3.46 (P < 0.0001). Improvement of QOL was larger among patients with vascular disorders (3.26 at Vf versus 5.35 at Vi, −39%, P < 0.0001) and smaller among individuals with scars (who had more severe initial impairment of QOL) (4.39 versus 5.52, −20%, P < 0.0001). The same result was obtained for depressed patients for whom a smaller improvement was noticed at Vf than for the non-depressed ones (−26% versus −35%, P < 0.0001). Lastly, patients under treatment showed the same improvement in their life (33%, from 5.28 at Vi to 3.53 at Vf) than patients without treatment (32%, from 4.88 at Vi to 3.35 at Vf). Interestingly, the improvement in QOL was slightly larger among patients without treatment (from 9.21 at Vi to 2.93 at Vf, n = 752) than for patients under topical or systemic treatment (from 10.05 at Vi to 4.37 at Vf, n = 77), highlighting the beneficial role of makeup in this improvement.

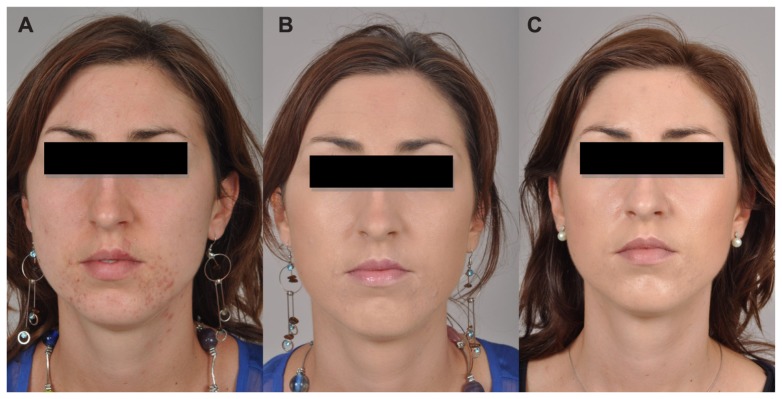

Appearance improvement

An example of the amelioration of appearance as documented by standardized photography is presented in Figure 1. Makeup completely masked the unwanted coloration, lesions, and scars, and application resulted in a noticeable amelioration of the patient’s appearance. These photos also highlight the differences between makeup performed with the help of the medical cosmetician and those made by the patient 1 month later.

Figure 1.

A patient with inflammatory acne at the initial consultation (Vi) before (A) and after makeup performed with the help of the medical cosmetician (B) and at the final visit (Vf) (C).

Discussion

This study confirms that disfiguring dermatoses have a moderate but significant impact on patients’ QOL that may lead to depression. In this study, more than 20% of the included patients were judged as depressed by the investigator dermatologists (55% with a moderate state and 30% with a light state). This depressive profile does not seem to be linked to the importance of the affected facial area or the duration of the disease. Patients with pigmentary disorders seemed more affected by depression than the other ones (36% versus <20%).

Skincare and makeup products used during this study were designed for patients with sensitive skin and have been submitted to non-comedogenic, non-irritating, and non-allergic tests. Our results indicate that they were safe for all ethnic groups (skin type I to V) and well tolerated by both male and female patients. The same improvement observed for patients with or without medical treatment before and throughout the study confirms that the use of these products could influence the QOL of affected patients without deteriorating conventional treatments.13

Boehncke et al2 have already reported the beneficial role of decorative cosmetics in patients with disfiguring skin diseases. He noticed that the mean DLQI score dropped significantly from 9.2 to 5.5 (P = 0.0009). Our data (9.9 to 3.5, P < 0.0001) confirm this assertion.

The most significant impact of these dermatoses on patients’ lives was on feelings (question 2) and the largest number of improved patients by makeup use was also for question 2. This result confirms the importance of self image for these patients, who have feelings of embarrassment and social inhibition and have an interest in using makeup to restore self esteem. Makeup covering visible signs of the disease can minimize stigmatization. As previously described, cosmetic camouflage rapidly improves patients’ mental status and quality of life. Just after self-applying the makeup at the baseline visit, 99% of patients thought that it made a noticeable improvement to their face and 88% felt more comfortable in their relationship with others. Moreover, the most improved aspects of their lives after makeup use was in leisure (sport, question 6) and daily activities (question 3), which are important psychologically. Interestingly, we noticed that the higher the initial impairment of QOL (depressed profile patients or patients with resulting scars) the smaller the observed improvement.

The present study allows for a better understanding of the profiles of patients with various disfiguring dermatoses and the effects on their lives. It also confirms their interest in corrective makeup to restore their self esteem and improve their QOL. Nevertheless, a limitation in this study is that there was not a control group for comparison that did not use makeup. In conclusion, dermatologists should encourage patients with disfiguring dermatoses to utilize appropriate and safe makeup to improve their appearance and their QOL. Corrective makeup can also complement the treatment of facial dermatological diseases in order to improve patients’ adherence. We therefore suggest that instructions and training for using skincare and corrective makeup might be useful.

Acknowledgments

We thank Martine Fortuné and Guénaëlle Le Dantec for their administrative support. The assistance of Stéphanie Ragot with the statistics is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Disclosure

S Seité and A Rougier are employees of La Roche-Posay Pharmaceutical laboratories this work was supported by a grant from La Roche-Posay Pharmaceutical Laboratories, Asnières, France.

References

- 1.Jowett S, Ryan TJ. Skin disease and handicap: an analysis of the impact of skin conditions. Soc Sci Med. 1985;20:425–429. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(85)90021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boehncke WH, Ochsendorf F, Paeslack I, Kaufmann R, Zollner TM. Decorative cosmetics improve the quality of life in patients with disfiguring skin diseases. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:577–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Segot-Chicq E, Compan-Zaouati D, Wolkenstein P, et al. Development and validation of a questionnaire to evaluate how a cosmetic product for oily skin is able to improve well-being in women. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:1181–1186. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Renzi C, Abeni D, Picardi A, et al. Factors associated with patient satisfaction with care among dermatological outpatients. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:617–623. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allevato MA, Stengel FM, Gutierrez Neri P. “Maquillage Correctivo Dermatologico”, a Publication by L’Oreal Argentina SA. 1st ed. Juramento; Argentina: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rayner VL. Cosmetic rehabilitation. Dermatol Nurs. 2000;12:267–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antoniou C, Stefanaki C. Cosmetic camouflage. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2006;5:297–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2006.00274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Draelos ZD. Colored facial cosmetics. Dermatol Clin. 2000;18:621–631. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(05)70213-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanioka M, Yamamoto Y, Kato M, Miyachi Y. Camouflage for patients with vitiligo vulgaris improved their quality of life. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2010;9:72–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2010.00479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ongenae K, Dierckxsens L, Brochez L, van Geel N, Naeyaert JM. Quality of life and stigmatization profile in a cohort of vitiligo patients and effect of the use of camouflage. Dermatology. 2005;210:279–285. doi: 10.1159/000084751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holme SA, Beattie PE, Fleming CJ. Cosmetic camouflage advice improves quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:946–949. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tedeschi A, Dall’Oglio F, Micali G, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Corrective camouflage in pediatric dermatology. Cutis. 2007;79:110–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuoka Y, Yoneda K, Sadahira C, Katsuura J, Moriue T, Kubota Y. Effects of skin care and makeup under instructions from dermatologists on the quality of life of female patients with acne vulgaris. J Dermatol. 2006;33:745–752. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2006.00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayashi N, Imori M, Yanagisawa M, Seto Y, Nagata O, Kawashima M. Makeup improves the quality of life of acne patients without aggravating acne eruptions during treatments. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:284–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merial-Kieny C, Nocera T, Mery S. Medical corrective make-up in post-chemotherapy. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2008;1:25–28. doi: 10.1016/S0151-9638(08)70094-2. French. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]