Buruli or Bairnsdale Ulcer (BU) is a neglected infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium ulcerans and is characterized by necrotic cutaneous lesions. Infection is challenging to treat, and the ideal combination of surgery and antimicrobial therapy continues to evolve. M. ulcerans has been endemic to the Bellarine peninsula in Victoria, Australia, since 1998, with more than 250 cases of infection. Studies have illustrated the safety and efficacy of antimicrobial therapy [1]–[5], and our standard treatment practice has evolved over the last 15 years to comprise limited surgical debridement with combination antimicrobial therapy.

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) is a paradoxical reaction occurring during treatment of an infection, recognized clinically by deterioration after initial improvement. These reactions are well described in tuberculosis and leprosy, where effective antimicrobial killing may be accompanied by (transient) clinical deterioration during treatment [6], [7], predominantly in HIV-infected patients after the introduction of antiretroviral therapy [8]. IRIS reactions may also occur in patients with a competent immune system [9]. Our group and others have described paradoxical reactions occurring during the treatment of M. ulcerans infection with antimicrobials [10], [11].

In cases of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB) infection complicated by IRIS, steroid therapy is recommended. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of IRIS in TB found that prednisone reduced the need for hospitalization and therapeutic procedures and hastened improvements in symptoms, performance, and quality of life [12]. In our group's description of paradoxical reactions during therapy for BU, we proposed that adjunctive corticosteroid therapy may improve healing and prevent the need for further surgical intervention [10]. In the last 2 years our group has therefore acquired an early experience with the use of steroid therapy to treat severe IRIS in patients with M. ulcerans infection.

From 1998 through the end of 2011, our group has treated 163 patients with M. ulcerans infection with antimicrobials. We have assessed both retrospectively (until 2009) and prospectively (since 2009) that 31 patients (19%) developed paradoxical reactions. To date, five patients have been treated with steroid therapy for severe paradoxical reactions.

The patients treated with corticosteroids were aged between 9 and 84 years. All patients were ambulatory and managed as outpatients. These patients developed IRIS 2–13 weeks after commencing combination antimicrobial therapy after experiencing an initial clinical improvement in the erythema and induration surrounding the lesion. The clinical findings that were indicative of a severe paradoxical reaction included markedly increased inflammation and induration surrounding the M. ulcerans lesion, copious wound discharge, the appearance of new secondary lesions, and necrotic eschar formation (see Table 1).

Table 1. Clinical details of patients with paradoxical reactions treated with corticosteroids.

| Age | Gender | Lesion Location | Time to Paradoxical Reaction (Days) | Initial Size of Lesion | Features of Paradoxical Reaction | Features after Steroid Therapy |

| 62 | F | Achilles region, ulcer | 21 | 2×5 cm ulcer; induration 13×4 cm | Increased wound discharge and pain | Ulcer unchanged; discharge and pain resolved |

| 83 | F | Posterior heel, ulcer | 92 | 3×3 cm ulcer; induration 5×8 cm | 8×4 cm induration and wound ooze | 2×2 cm lesion; no induration |

| 9 | F | Lower leg, ulcer | 53 | 1 cm ulcer; minimal induration | Marked induration and wound discharge | Ulcer unchanged; swelling and discharge resolved |

| 14 | F | Knee, ulcer | 17 | 8 mm ulcer; induration 2×2 cm | Induration 6×6 cm and wound discharge | Ulcer unchanged; induration and discharge resolved |

| 84 | M | Elbow, edematous lesion | 30 | No ulcer; induration 13×11 cm | Induration 28×20 cm | Induration resolved |

Time to paradoxical reaction was defined as the number of days from the commencement of antibiotics until the onset of the paradoxical reaction.

Clinical deterioration during antibiotic treatment may be interpreted as treatment failure, leading to further potentially disfiguring and unnecessary surgery and either a change or prolongation of antimicrobial therapy [10]. Therefore, we believe that confirmation of a paradoxical reaction via histopathological assessment of a biopsy specimen and mycobacterial cultures are important in the therapeutic decision-making process for patients with clinical deterioration during antimicrobial therapy for M. ulcerans. Histopathological findings of a paradoxical reaction include ulceration and necrosis, a florid mixed inflammatory infiltrate with multinucleated giant cells, usually sparse or absent acid fast bacilli (AFB), and negative mycobacterial cultures (see Figures 1 and 2) [10], [13], although excised tissue may remain positive for M. ulcerans via polymerase chain reaction. In all of our cases with a paradoxical reaction, mycobacterial cultures were negative regardless of whether AFBs were seen on microscopy. We recognize that biopsy and histopathology may not be readily available in resource-limited settings managing patients with BU. In these cases, a diagnosis of paradoxical reaction based on clinical parameters will be most appropriate.

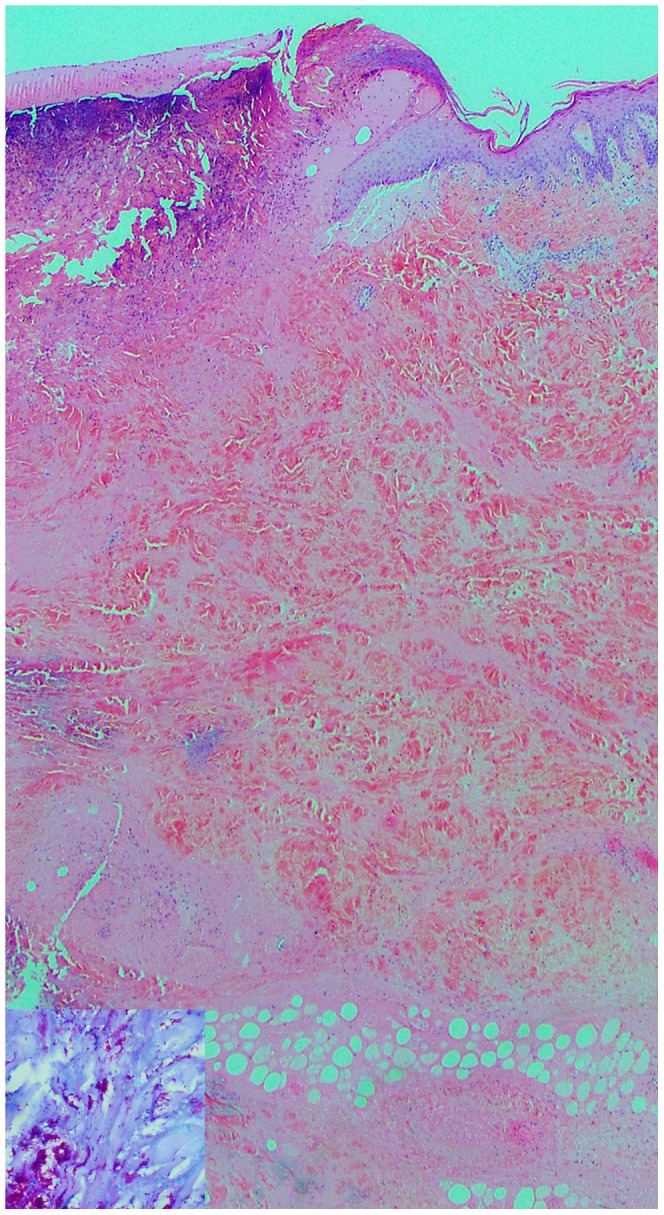

Figure 1. Skin biopsy from patient A after diagnosis of BU.

Skin biopsy (×2.5 magnification) showing ulceration and extensive undermining necrosis of the dermis and subcutaneous fat with minimal inflammation, typical of B.U. Insert, Wade Fite stain (×40 magnification) showing numerous acid fast bacilli.

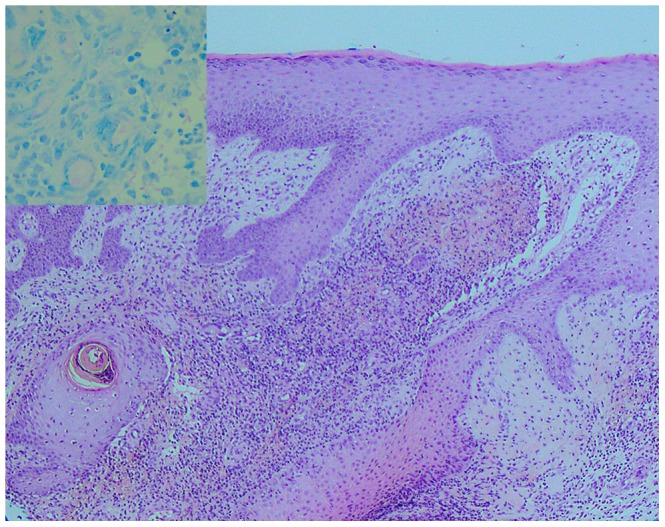

Figure 2. Skin biopsy from patient A with IRIS 7 weeks through antibiotic treatment for BU.

Skin biopsy (×10 magnification) showing mixed inflammatory and granulation tissue reaction with prominent multinucleated giant cells, typical of a paradoxical reaction during antibiotic therapy for BU. Insert, Wade Fite stain (×40 magnification) showing very sparse acid fast bacilli.

In our patients a provisional diagnosis of severe IRIS was followed by commencement of prednisone at a dose of 0.5–1 mg/kg daily with the aim of reducing further tissue destruction, preserving skin grafts, and limiting the extent of further surgery. In all patients with M. ulcerans treated with steroid therapy, there was a marked clinical improvement in the appearance of the lesion within days to weeks, and the duration of prednisone therapy used was 4–6 weeks, with gradual tapering of the dose after the first 2–3 weeks of therapy.

All patients tolerated prednisone well with no side-effects, and antimicrobial therapy was not changed nor prolonged beyond 12 weeks despite the occurrence of a paradoxical reaction. All patients underwent debridement of their M. ulcerans lesions before or after the commencement of the prednisone. Ultimately all have achieved complete healing without recurrence between 9–21 months after initial treatment.

M. ulcerans produces a necrotizing macrolide toxin, mycolactone, which profoundly suppresses elements of innate and adaptive cell-mediated immunity, thereby enhancing progression of BU [14]. Histopathologically, BU lesions are characterized by a poor inflammatory response. In some BU lesions, treatment with antibiotics may cause temporary immune-mediated inflammation with clinical worsening, which we and others have proposed as a paradoxical sign of treatment success [10], [11].

In the cases that we have treated with prednisone for a paradoxical reaction during therapy for M. ulcerans infection, subsequent severe clinical deterioration has occurred after initial improvement on antibiotic therapy. This may be explained by an apparent reversal of the local immune-tolerant state of active M. ulcerans infection due to antibiotic therapy. A local cellular immune response has been shown to develop in these situations as production of mycolactone is reduced [14], presumably in response to persisting mycobacterial antigens. We believe that in our patients, the current practice of limited surgical debridement with combination antimicrobial therapy results in incomplete excision of mycobacteria-infected tissue, which may potentiate the development of paradoxical reactions.

As with paradoxical immune reactions to antimicrobial therapy for other mycobacterial diseases where corticosteroids are known to be effective [12], [15], our approach with these BU infections was to commence prednisone as adjunctive treatment to antibiotics to settle the severe immune-mediated reaction and limit secondary tissue damage. The dose was chosen based on recommendations for the treatment of TB-IRIS reactions [12]. The use of prednisone in these BU cases was associated with a settling of the skin lesions and ultimately prevented the need for further extensive surgery. Furthermore, complete healing occurred despite not extending the duration of antimicrobial therapy beyond 12 weeks.

We acknowledge several factors that may limit the use of steroid therapy in this clinical setting. Prednisone may adversely affect outcomes by suppressing the host immune response to M. Ulcerans, and reduced serum levels of prednisone may result from an interaction with rifampin [16], [17]. In addition, the use of steroid therapy is associated with many potential complications, and therefore, not all patients with BU may be optimal candidates for steroid therapy. For example, in BU endemic areas with high rates of co-existent infections such as tuberculosis or strongyloidiasis, prednisone may adversely affect the outcomes of these co-infections [18]. It is advisable during therapy with corticosteroids that the following parameters be monitored: mood changes, sleep disturbance, and increase in appetite. Blood glucose levels and blood pressure should be monitored where there is a history of diabetes mellitus or hypertension or a clinical predisposition to either of these conditions.

There are potential limitations to our purely observational description of success with the use of adjunctive steroid therapy in patients with a severe paradoxical reaction during antimicrobial treatment for BU. For instance, in the absence of a control group, it is unclear what the progress of the healing of these skin lesions would have been without steroid therapy, and whether the outcome may have been the same. Furthermore, the use of limited debridement of lesions in conjunction with antimicrobials, both of which are known to be effective in the cure of M. ulcerans infection [1]–[3], may have influenced healing significantly such that the effect of steroids alone is unclear. Nonetheless, there is historical precedence that is supportive of corticosteroid use in paradoxical reactions with other mycobacterial infections [12].

To our knowledge this is the first description of corticosteroid use in cases of M. ulcerans where severe paradoxical reactions to antibiotic treatment have occurred. In our early experience, the use of prednisone at a dose of 0.5–1 mg/kg was clinically effective and well tolerated. Moreover, the use of steroid therapy in addition to antimicrobial therapy in our patients was associated with good cosmetic outcomes, no significant adverse effects, and no need for further major surgical intervention. Hence we would advocate for further prospective study of corticosteroid use in the treatment of M. ulcerans–associated severe paradoxical reactions.

Funding Statement

There was no funding for this work.

References

- 1. O'Brien DP, Hughes AJ, Cheng AC, Henry MJ, Callan P, et al. (2007) Outcomes for Mycobacterium ulcerans infection with combined surgery and antibiotic therapy: findings from a South-eastern Australian case series. Med J Aust 186: 58–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. O'Brien DP, McDonald A, Callan P, Robson M, Friedman ND, et al. (2012) Successful outcomes with oral fluoroquinolones combined with rifampicin in the treatment of Mycobacterium ulcerans: an observational cohort study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 6: e1473 doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nienhuis WA, Stienstra Y, Thompson WA, Awuah PC, Abass KM, et al. (2010) Antimicrobial treatment for early, limited Mycobacterium ulcerans infection: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 375: 664–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chauty A, Ardant MF, Marsollier L, Pluschke G, Landier J, et al. (2011) Oral treatment for Mycobacterium ulcerans infection: results from a pilot study in Benin. Clin Infect Dis 52: 94–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization (2004) Provisional guidance on the role of specific antibiotics in the management of Mycobacterium ulcerans disease. Geneva: WHO.

- 6. Beishuizen SJE, Geerlings SE (2009) Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome: immunopathogenesis, risk factors, diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Netherlands Journal of Medicine 67: 327–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Walker SL, Lockwood DN (2008) Leprosy type 1 (reversal) reactions and their management. Lepr Rev 79: 372–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Leprosy reversal reaction as immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in patients with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis 46: e56–e60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carvalho AC, De Laco G, Saleri N, Pini A, Capone S, et al. (2006) Paradoxical reaction during tuberculosis treatment in HIV-seronegative patients. Clin Infect Dis 42: 893–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. O'Brien DP (2009) “Paradoxical” immune-mediated reactions to Mycobacterium ulcerans during antibiotic treatment: a result of treatment success, not failure. Med J Aus 191: 564–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nienhuis WA, Stienstra Y, Mohammed Abass K, Tuah W, Thompson WA, et al. (2012) Paradoxical responses after start of antimicrobial treatment in mycobacterium ulcerans infection. Clin Infect Dis 54: 519–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meintjes GA (2010) Randomized placebo-controlled trial of prednisone for paradoxical tuberculosis-associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. AIDS 24: 2381–2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Guarner J, Bartlett J, Whitney EA, Raghunathan PL, Stienstra Y, et al. (2003) Histopathologic features of Mycobacterium ulcerans infection. Emerg Infect Dis 9: 651–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schutte D, Umboock A, Pluschke G (2009) Phagocytosis of Mycobacterium ulcerans in the course of rifampicin and streptomycin chemotherapy in Buruli ulcer lesions. Br J Dermatol 160: 273–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Garcia Vidal C, Rodriguez Fernandez S, Martinez Lacasa J, Salavert M, Vidal R, et al. (2005) Paradoxical response to antituberculous therapy in infliximab-treated patients with disseminated tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis 40: 756–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Finch CK, Chrisman CR, Baciewicz AM, Self TH (2002) Rifampin and rifabutin drug interactions: an update. Arch Intern Med 162: 985–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McAllister WA, Thompson PJ, Al-Habet SM, Rogers HJ (1983) Rifampicin reduces effectiveness and bioavailability of prednisolone. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 286: 923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Khasawneh F, Sreedhar R, Chundi V (2009) Strongyloides hyperinfection: an unusual cause of respiratory failure. Ann Intern Med 150: 570–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]