Abstract

The role of food matrix and gender on soy isoflavone metabolism and biomarkers of activity were examined in twenty free-living adults (34.7±11.5 yrs old) with hypercholesterolemia (221.9 ±18.7mg/dL). In a randomized crossover design study, participants consumed soy-bread (3 wk) or soy-beverage (3 wk) containing 20 g soy protein with 99 and 93 mg isoflavones aglycone equivalents per day, respectively. During soy bread intervention, women had significantly greater microbial metabolite excretion (P=0.05) of isoflavonoids than men. In men, isoflavone metabolite excretion was not discernibly different between the two matrices. Significant reductions (P ≤ 0.05) in triglycerides (24.8%), LDL cholesterol (6.0%), apolipoprotein A-I (12.3%), and lipid oxidative stress capacity (25.5%), were observed after soy food intervention. Our findings suggest that the food matrix significantly impacts soy isoflavone metabolism, particularly microbial metabolites in women.

Introduction

Numerous descriptive epidemiological studies associate the consumption of soy, common in Asian populations, with a reduced risk of several chronic disease processes.1 Many of these hypotheses have been tested in rodent models with demonstrated beneficial effects on endpoints of cancer, cardiovascular, and bone health with support of additional in vitro mechanistic studies.2-4 One critical issue that must be considered in moving forward with soy-based, long term clinical trials is the source and types of soy foods provided for participants. Indeed, the types of food products produced and employed in trials may have relevant impact upon the absorption, distribution metabolism, and excretion of the various phytochemicals, which in turn may influence their bioactivity. Differences in food types may also explain the mixed and inconsistent results of past reports.5,6 Thus, additional research in humans that focuses upon how the food matrix affects these processes is necessary in designing optimal soy-based foods for improved health.

Traditional Asian dietary habits incorporate a variety of soy products such as whole soybeans, soymilk, tofu, and miso with an estimated mean intake of 50 mg of soy isoflavones per day.7, 8 Whereas, in Western cultures these products are minimally consumed with the mean intake of soy isoflavones among Americans is estimated at less than 1-3 mg per day in 2003.8-10 The food industry has developed several approaches to increasing the availability of soy-based products to consumers in the United States including soy beverages, baked soy products, and texturized soy protein.11,12 Delivering sufficient amounts of soy protein and isoflavones suitable for clinical trials is a major obstacle in the production of palatable soy foods. The inclusion of substantial amounts of soy protein and phytochemicals results in beany off-flavors and specifically in bread, loss of bread quality, and changes in texture.

Among the various bioactive phytochemicals found in soy foods, isoflavones are the most active and extensively studied.8,13,14. In reference to cardiovascular disease, clinical trials have shown that soy isoflavones, when consumed with its associated protein, lower cholesterol,15,16 improve lipid oxidation resistance,17,18 minimize endothelial dysfunction,19,20 and behave as PPARγ agonists.13 Isoflavones modulate cellular signaling and gene expression in a manner that may impact cancer prevention and modulate immune response.21,22 Moreover, biologic activity varies among the different isoflavones and their metabolites.23,24 For instance, daidzein metabolites, equol and O-desmethylangolensin (ODMA), have demonstrated improved bone health25 and inhibition of growth in prostate cancer cells.26

In humans, isoflavone metabolite formation demonstrates significant complexity and heterogeneity. Host characteristics are hypothesized to contribute to the heterogeneity in soy isoflavone absorption and metabolite formation, including age,27,28 gender,29 colonic microbiota maturity,30-33 biological entrapment of isoflavones,34 and isoflavone degrading phenotype.35 Produced by microbiota residing within an individual’s colon, metabolic products of daidzein (dihydrodaidzein (DHD), equol, and ODMA) and genistein (dihydrogenistein and 6′-OH-ODMA) have been readily found in plasma and urine.30,36 Furthermore, factors such as food matrix,37-39 meal composition,40 and variation in isoflavone composition due to horticulture, processing, and cooking practices41,42 may all impact isoflavone metabolism and subsequent metabolite formation. Prior studies show that isoflavone distribution and profile in soy foods is variable and dependent on starting isoflavone composition, food matrix, and food processing history.38,40,42,43 Cassidy et al. investigated the effect of a single dose of three soy foods with varying viscosities and isoflavone profile on isoflavone absorption.40 Higher serum peak levels and greater area under the curve were observed with tempeh compared to textured vegetable protein while isoflavones from soy milk were absorbed faster with earlier peak levels.39,40 The objective of the current soy intervention trial was to assess the impact of food matrix upon isoflavone metabolism and biomarkers of activity in hypercholesterolemic men and women. We chose to compare a liquid (soy beverage) with a solid soy vehicle (soy bread) fed over 3 weeks. Since viscous foods are thought to delay gastric emptying, we hypothesized that differences in soy isoflavone metabolism can be expected, due to differences in food matrix.

Participants and Methods

Participants

This study protocol was approved by the Biomedical Sciences Institutional Review Board of The Ohio State University. Participants gave informed written consents and total cholesterol (TC) in fasting blood was screened to determine their eligibility. Provided they were free from significant co-morbidities that could impact metabolism, not on cholesterol lowering agents (statins and high dose niacin), MAO (monoamine oxidase) inhibitors, antibiotics (6 months prior to start of study), or dietary supplements, 21 hypercholesterolemic (200 to 275 mg/dL) men and women (18 to 70 years old) were enrolled.

Study Design

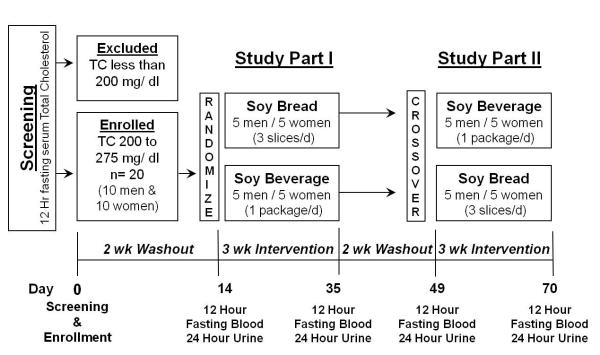

Participants were stratified by gender and in a randomized crossover design involving two soy food interventions (soy beverage and soy bread) (Fig. 1). After a 2 wk washout, participants were randomized either to a 3 wk soy beverage or soy bread intervention, followed by another 2 wk washout and then crossed over to the other dietary intervention (3 wk). Height was measured with a wall mounted Harpenden Stadiometer (Holtain Ltd., UK) during the screening visit. Weight (Scale-Tronix digital scale) and vital signs (pulse, blood pressure, temperature, and respirations) were recorded on days 0, 14, 35, 49, and 70. Compliance to dietary intervention was assessed using a soy food intake journal. Participants were instructed to document any deviations in their legume-free diet and their consumption of soy study foods (time, quantity of soy study foods consumed, and foods used for their preparation) in their journals. Interview questions were used to assess changes in physical activity, alcohol consumption, diet, and bowel patterns.

Fig.1.

Schematic diagram of the crossover study design comparing soy bread and soy beverage in women and men

Diet

Free-living participants followed a legume-free diet during the 10 wk soy intervention. Therefore participants were instructed to avoid all legumes such as beans, peanuts, peas, lentils, soybeans (soy lecithin and soybean oil were permitted), sprouts (clover, alfalfa, and bean), and products made with these ingredients. One package (58g) of Vanilla Pleasure™ soy beverage powder (Revival® Soy, Physicians Laboratories, Winston-Salem, NC) when reconstituted with 12 US fl oz of a low-fat liquid (water, fruit juice, or non-fat milk) was provided daily during the soy beverage intervention period. The beverage powder provided 220 kcal, 6 g fat, 31 g carbohydrate, 20 g of soy protein (aqueous washed soy protein isolate and soy protein concentrate), and 99 mg aglycone equivalents (AE) of total isoflavone. For the soy bread intervention period, three slices (65g/slice) of Healthyhearth™ soy bread (Bavoy®, Inc., Columbus, OH) was consumed daily, alone or as a sandwich with condiments (jam, jelly, nut butter, ketchup, mustard, mayonnaise, or butter). The soy bread contained a balance of bread ingredients and mix of defatted soy flour and a solvent-free processed soymilk. Three slices of soy bread provided 330 kcal, 9 g fat, 39 g carbohydrates, 25 g protein (20 g soy protein), and 93 mg AE of total isoflavones. There were no differences in total aglycone (8.95 mg AE and 8.55 mg AE) and glycoside (89.94 mg AE and 84.95 mg AE) composition in the soy beverage and soy bread, respectively. Participants were instructed to avoid heating (toasting, frying, microwave heating or reconstituting with hot liquids) the study foods.

Chemicals

HPLC-grade acetonitrile (ACN), acetic acid, methanol (MeOH), and water were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ). Dimethyl sulfoxide (ACS spectrophotometric grade) and isoflavone standards daidzein, genistein, glycitein, and equol were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). A compound similar in structure to isoflavones, 2′,4′, dihydroxy-2-phenylacetophenone (Indofine, Hillsborough, NJ), was used to evaluate recovery during the extraction process (recovery in food was 91% and in urine 86%). Daidzin, genistin, glycitin, acetyl daidzin, malonyl genistin, and acetyl genistin were obtained from LC Laboratories division (PKC Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Woburn, MA) and malonyl daidzin, and malonyl glycitin from Wako Chemicals USA, Inc. (Richmond, VA). Isoflavone metabolites (DHD, dihydrogenistein, genistein, glycitein, ODMA, and 6-OH-ODMA) were from Plantech (Reading, England).

Food Sample Preparation

Samples of soy bread from each of the 22 baking days and powdered soy beverage from a single lot were prepared for extraction as described by Murphy et al.44 Adapted from Achouri et al., freeze-dried samples (500 mg) were extracted using 60% ACN (10 mL) in polypropylene centrifuge tubes in a sonicating bath (Fisher Scientific FS30H, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) at 15°C for 20 min. and centrifuged (30 min. at 2500xg).45 Extractions were repeated once and pooled for each food sample. Extracts (2.0 ml aliquot) were dried under nitrogen and stored at −80°C until HPLC analysis. Each food sample was re-dissolved in 80% MeOH prior to HPLC analysis. Soy bread and beverage samples were analyzed in triplicate.

Separation and Quantification of Isoflavones in Soy Foods

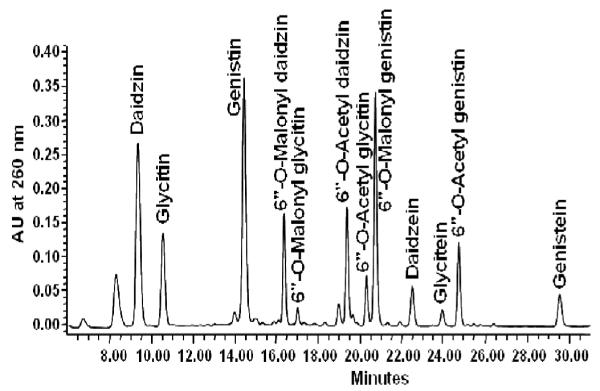

Food extracts were analyzed utilizing a Waters model 2690 HPLC equipped with Waters 2996 photodiode array detector (PDA), autosampler (10°C), and column heater at 30°C (Waters Associates, Milford, MA). Reversed phase separation was performed using a 3.0 × 100 mm, 3 μm particle, HydroBond™ PS C18 column (MAC-MOD Analytical, Inc., Chadds Ford, PA) with a HydroBond™ guard column (Fig. 2). The tertiary mobile phase (1% aqueous acetic acid: ACN: MeOH) gradient began at 85:10:5 for 2 min., progressing linearly to 65:35:0 by 31 min., 25:75:0 by 36 min., and 85:10:5 by 37 min. for a total run time of 42 min.. Injection volume was 10 μL.

Fig. 2.

Representative HPLC chromatogram of isoflavones in soy food at 260 nm.

Stock solutions of isoflavone standards were prepared as described by Achouri et al.45,46 Retention times of standards in HPLC chromatograms and previously published UV–visible spectral signatures were used for identification of unknowns.47 Isoflavone concentration in food is reported in mg AE. Since standard was unavailable, acetyl glycitein was estimated using the glycitin standard curve and adjusted using a response factor derived from published extinction coefficients.44

Urine Sample Preparation

Pre-weighed 24 h urine containers with boric acid (1.0 g) and ascorbic acid (0.50 g) were provided to participants prior to each clinic visit. Completed urine collection were those collected for more than 23 hours. The urine volume was measured, and samples were aliquoted and stored at −80°C until HPLC analysis. Extraction of isoflavones in urine was adapted from Franke et al.48 Urine samples (2.0 mL) were incubated for 3 hours at 37°C in a Dubnoff Metabolic Shaking incubator (GCA/ Precision Scientific, Chicago, IL) with 100 μL of crude H. pomatia gastric juice (Hoffman La Roche, Basels, Switzerland) and extracted with diethyl ether (5.0 ml × 3 volumes). Pooled extracts were dried under nitrogen and stored at −80°C until HPLC analysis. Dried deconjugated urine extract was re-dissolved in MeOH, sonicated, and filtered prior to HPLC analysis.

Separation and Quantification of Isoflavones in Urine Samples

HPLC analysis of urine extracts utilized the same instrumentation, stationary, and mobile phases as food samples. However, the linear gradient was as follows: 75:15:10 (1% aqueous acetic acid/ACN/ MeOH) isocratic for 5 min, linearly increased to 65:20:15 by 10 min., 50:25:25 by 13 min., 10:45:45 by 16 min., 5:50:45 by 20 min., and returned to starting composition (75:15:10) by 22 min., for a total run time of 27 min.

Isoflavone metabolite standards were used to quantify isoflavone metabolites from hydrolyzed urine samples.46 Urinary isoflavonoids were reported as mg isoflavonoid excreted in 24 hours. HPLC-mass spectrometry was used to test for daidzein metabolites in urine. The same HPLC system was used as described above except the PDA eluent was split 1:10 and interfaced with a QTof Premier (Micromass UK Ltd., Manchester, UK) in electrospray negative mode. Instrument parameters included: capillary voltage 2.8 kV, desolvation temperature 450°C, cone 35 V, cone gas 50 L/h and desolvation gas 600 L/h.

Plasma Biomarkers

Venous blood samples were obtained in the General Clinical Research Center at The Ohio State University Medical Center (OSUMC), Columbus, OH. After a 12 hour fast, blood was collected in Vacutainer™ tubes (Becton, Dickinson and Co., Franklin Lakes, NJ) with appropriate additives for each specific test. Blood was analyzed at the OSUMC Central Laboratory (complete lipid panel and C-reactive protein (CRP)) and by the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN (apolipoprotein A-I and B). TC, high density lipoprotein (HDL), and triglyceride (TG) were enzymatically analyzed using an automated PDA spectrophotometer clinical analyzer (SYNCHRON® System; Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA). For all lipid parameters and CRP, total %CV was 4.5 and within run %CV was 2.0 to 3.0.49,50 Low density lipoprotein (LDL) concentration was calculated using the Friedewald equation.51 CRP was analyzed using laser nepholometry methods (Beckman Coulter Image; Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA). Quantification of apolipoprotein A1 (apoA1) and apolipoprotein B (apoB) were conducted at the Mayo Clinic using immunoturbidimetric methods (within run %CV 6.6).52,53

Lipid Oxidative Stress Capacity

Once blood was collected in K3EDTA Vacutainer™ tubes, lipid oxidative stress capacity (LOSC) was evaluated using methods detailed by Hadley and colleagues.54 Triplicate repetitions were performed for each blood sample. By suspending and re-precipitating with dextran-MgCl2 solution, EDTA was removed from isolated LDL+VLDL fraction. Cholesterol concentration of the LDL+VLDL fraction (within-run %CV was 4.2; total %CV was 8.6) was determined using a total cholesterol quantification kit (Diagnostics Chemicals Limited). During lipoprotein isolation all reagents and samples were kept on ice.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using Minitab 15.0 (Minitab Inc., State College, PA) and P ≤ 0.05 was considered to be significant. Independent t-test was used to evaluate significant differences in soy food isoflavone composition. The normal probability plots of clinical parameters and urinary isoflavones were not normally distributed. Therefore Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to evaluate differences within and among treatment periods and Mann-Whitney tests were used to determine differences between genders within each treatment period. Values are reported as arithmetic mean ± SD for soy isoflavones and mean ± SE for clinical measures and isoflavonoids from urine.

Results

Participant Description

Forty-nine adults were screened and 21 participants (34.7 ± 11.5 years old) enrolled with 20 completing the study. One participant dropped out during the first treatment period due to difficulty in complying with the soy bread diet. The majority were Caucasian (85%) and non-smokers (95%). All women except one were premenopausal (67% on oral contraceptives). Age, height, mean arterial pressure (MAP), weight, and body mass index (BMI) within gender groups randomized to begin with soy bread or soy beverage treatment did not differ and no significant changes in these parameters were observed. According to soy food intake journals, self-reported compliance to the legume-free diet was excellent at 94.3 ± 6.8% with overall compliance to the soy bread (94.5 ± 6.4%) and soy beverage (95.5 ± 8.6%) intervention being similar. One participant was excluded because urinary isoflavones were not detected after their soy bread intervention suggesting non-compliance.

Lipid Measures

There were no significant differences in plasma biomarkers at baseline between the two study groups, and no change from baseline to day 14. Of the many biomarkers examined, significant reductions in triglycerides (P = 0.05), LDL cholesterol (P = 0.05), apo A-I (P < 0.001), and LOSC lag time (P < 0.001) were observed after for the total soy food intervention from day 14 to day 70 (Table 1). When lipid parameters were stratified according to soy bread and soy beverage interventions, Apo A-I decreased by 9.1% (P < 0.001) and LOSC lag time decreased by 14% (P = 0.01) following beverage intervention. Changes were not significant after the bread intervention, nor were differences between women and men.

Table 1.

| Lipid Variables | Day 14c | Day 70 |

|---|---|---|

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 221.9 ± 4.5 | 213.5 ± 7.5 |

| High Density Lipoprotein (mg/dL) | 47.5 ± 3.0 | 48.3 ± 3.2 |

| Low Density Lipoprotein (mg/dL) † | 147.1 ± 4.2 | 138.3 ± 6.5 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) † | 178.6 ± 45.6 | 134.3 ± 22.3 |

| Apolipoprotein A-I (mg/dL) † | 173.6 ± 7.4 | 149.3 ± 8.0 |

| Apolipoprotein B (mg/dL) | 98.9 ± 3.4 | 95.8 ± 3.9 |

| C-reactive Protein (mg/dL) | 4.3 ± 0.8 | 3.6 ± 0.5 |

| Lipid Oxidative Stress Capacity† | 168.1 ± 13.0 | 125.1 ± 6.4 |

Serum cholesterol

Lipid oxidative stress capacity measured by copper induced formation of conjugated diene

Mean ± SEM (n=19)

Statistical significance (P ≤ 0.05) determined using Wilcoxon signed-rank test

Soy Food Intervention on Isoflavonoid Excretion

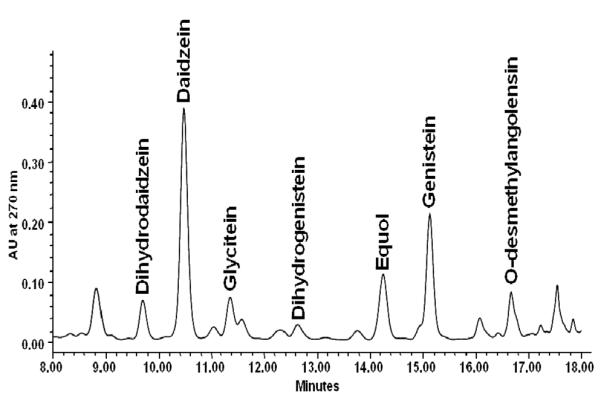

The isoflavones monitored by HPLC (Fig. 3) included the three parent isoflavones (daidzein, genistein, and glycitein) and the daidzein and genistein microfloral isoflavonoids (DHD, ODMA, equol, dihydrogenistein, and 6′OH-ODMA). Isoflavonoid levels in day 14 urine samples were very low and often undetectable, indicating adequate legume washout. Among the isoflavone families, recovery of daidzeins (daidzein, DHD, ODMA, equol) was greater than that of genisteins (genistein, dihydrogenistein, 6′′OH-ODMA) regardless of soy food type. Daidzein and genistein (parent compounds) accounted for the majority of isoflavonoids excreted although metabolites of both were detected.

Fig. 3.

Representative HPLC chromatogram of isoflavonoids in enzymatically digested urine of an equol and O-desmethylangolensin excretor at 270 nm

Isoflavonoid Excretion in Women and Men Following Soy Bread Intervention

Significant differences in isoflavonoid excretion patterns were found with soy bread intervention in women. Women excreted significantly greater amounts of DHD (P = 0.05) and ODMA (P = 0.05) than men after soy bread consumption (Table 2), and all women excreted detectable amounts of either ODMA or equol yet only 56% of the men did so with bread intervention. Additionally, a metabolite of genistein, 6-OH-ODMA, was excreted in significantly greater amounts in women and not detectable in men with soy bread intervention. In contrast, there were no significant differences in isoflavonoid excretion after soy beverage intervention between men and women.

Table 2.

Gender differences isoflavonoids in urine (mg isoflavone/24 hour) a

| Urine Isoflavonoids |

Women (n=10) |

Men (n=9) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total IFb | |||

| Soy beverage | 28.34 ± 2.86 | 28.61 ± 6.12 | 0.74 |

| Soy bread | 32.31 ± 4.95 | 20.96 ± 7.34 | 0.29 |

| Total Daidzeinc | |||

| Soy beverage | 22.60 ± 2.34 | 23.08 ± 5.26 | 0.99 |

| Soy bread | 26.50 ± 4.06 | 15.20 ± 5.56 | 0.12 |

| Total Genisteind | |||

| Soy beverage | 4.12 ± 1.08 | 3.68 ± 0.77 | 0.94 |

| Soy bread | 5.35 ± 1.19 | 5.24 ± 2.34 | 0.41 |

| Glycitein | |||

| Soy beverage | 1.62 ± 0.20 | 1.85 ± 0.44 | 0.99 |

| Soy bread | 0.46 ± 0.09 | 0.52 ± 0.25 | 0.46 |

| Daidzein | |||

| Soy beverage | 9.31 ± 2.03 | 7.30 ± 1.66 | 0.68 |

| Soy bread | 5.84 ± 1.27 | 6.18 ± 2.68 | 0.57 |

| Dihydrodaidzein | |||

| Soy beverage | 2.52 ± 0.81 | 5.91 ± 3.22 | 0.54 |

| Soy bread | 4.42 ± 0.91† | 1.56 ± 0.66† | 0.05 |

| Equol | |||

| Soy beverage | 2.68 ± 2.10 | 2.97 ± 2.97 | 0.70 |

| Soy bread | 7.31 ± 3.80 | 4.00 ± 4.00 | 0.25 |

| ODMA (O-desmethylangolensin) | |||

| Soy beverage | 8.09 ± 2.38 | 6.90 ± 1.97 | 0.99 |

| Soy bread | 8.93 ± 2.40† | 3.46 ± 1.86† | 0.05 |

| Genistein | |||

| Soy beverage | 3.85 ± 0.94 | 3.26 ± 0.64 | 0.87 |

| Soy bread | 4.71 ± 0.96 | 4.91 ± 2.37 | 0.37 |

| Dihydrogenistein | |||

| Soy beverage | 0.26 ± 0.16 | 0.42 ± 0.24 | 0.72 |

| Soy bread | 0.53 ± 0.23 | 0.33 ± 0.15 | 0.49 |

| 6-OH-ODMA (6OH-O-desmethylangolensin) | |||

| Soy beverage | 0.01 ± 0.01 | ND | 0.98 |

| Soy bread | 0.11 ± 0.09 | ND | 0.04 |

mg isoflavonoid per total volume of urine collected over 24 hours from days 35 and 70 (stratified by soy food intervention), reported as mean ± SEM.

Includes total of all isoflavonoids excreted in urine

Includes daidzein, dihydrodaidzein, O-desmethylangolensin, and equol

Includes genistein, dihydrogenistein, and 6-OH O-desmethylangolensin Statistical significance between genders was determined using Mann-Whitney test denoted by †

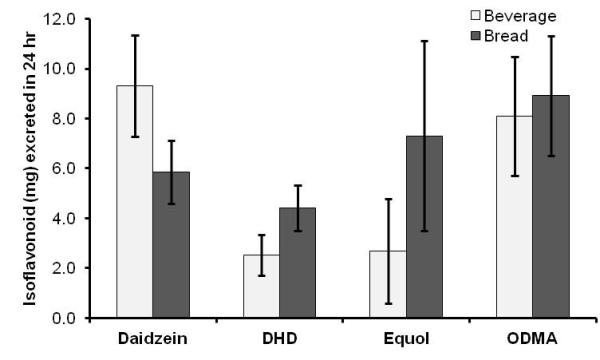

When isoflavonoid profiles in urine were compared between soy bread and soy beverage interventions in women, DHD was significantly greater (P=0.04) following the soy bread period. Similarly, there was a trend toward greater equol and ODMA levels and lower daidzein after the soy bread period (Fig. 4). Soy bread appeared to encourage metabolism of daidzein to its respective metabolites in women. These differences were not seen in men.

Fig.4.

Comparison of daidzein metabolite profile in women (n=10) after soy beverage and soy bread intervention. DHD (dihydrodaidzein), equol, and ODMA (O-desmethylangolensin). Statistical significance (P ≤ 0.05) determined using Wilcoxon signed-rank test denoted with *.

Discussion

Phytochemical-rich soy can be incorporated into beverage and bread food products that are convenient and desirable for use in clinical trials. The acceptance of both soy bread and soy beverage, as demonstrated in this study, illustrate the versatility of a new generation of soy-enhanced foods and their convenience as we consider future clinical trials to assess health outcomes and disease prevention. We observed no significant toxicity based upon NIH criteria.55 Both products deliver soy isoflavones, one of many classes of potentially bioactive components in soy, at levels similar to those found in Asian diets.7,56,57 Our work further suggests that food matrix influences isoflavone metabolism in women, a finding that may allow future investigators to design food products to achieve specific patterns of phytochemical metabolism in vivo.

During the ten week study significant changes in LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, apolipoprotein A-I, and LOSC were observed in men and women. Specifically, soy beverage intervention significantly decreased apolipoprotein A-I and LOSC. One early study reported an increase in lag time as much as 32% greater than baseline17 whereas others reported no change to lag time with soy intervention.58 These modest changes in biomarkers of cardiac risk in our cohort maybe due to the relatively low dose of soy protein compared to what is recommended by the FDA approved health claim (25g/day)59 or the short 3 wk duration for each soy food intervention.

Equivalent quantities of dietary genistein and daidzein were consumed in this study; however, similar to earlier studies, excretion of isoflavones varied significantly with urinary daidzein and its metabolites being excreted more readily than genisteins.31,60-62 Furthermore, consistent with other studies, 30% of our cohort were equol producers and all except three participants produced ODMA and DHD.33,63 Equol and ODMA production has been associated with specific intestinal bacteria.36,63 The ODMA non-producers were positive for equol which may reflect that equol conversion outcompeted the ODMA pathway.61 Similar to findings of Heinonen and colleagues, in our study dihydrogenistein was found more readily (53% of participants in our cohort) than 6-OH-ODMA,64 but metabolites represented only 2-13% of total genistein.

Previous soy intervention studies investigating soy isoflavone metabolism have administered isoflavones via single food matrix,34 as a single dose,38 as purified compounds,46 or with varied isoflavone profiles in multiple matrices.39,40 Much effort was made to maintain dosage and aglycone and glycoside composition homogeneity between the liquid and solid matrices in this study. We observed that isoflavones and their metabolites were excreted in varying amounts depending on the soy food, similar to other studies.39,40 Specifically, with soy bread intervention, women tended to show less excretion of the parent isoflavone daidzein with corresponding increases in daidzein metabolites compared to soy beverage. These findings imply that the physicochemical properties of soy bread favored formation of isoflavone metabolites in women. As previous studies suggest, the solid matrix might affect isoflavone metabolism by protecting against its degradation, or lengthening isoflavone exposure time to intestinal microflora or intestinal epithelial tissue for absorption.39,65 Zheng et al. observed that a solid food matrix enhanced microbial degradation of isoflavone compounds and thereby diminished isoflavone bioavailability.66

Isoflavonoid concentrations in urine relative to their families (daidzein and genistein) between men and women were affected by the physicochemical differences between the two soy food matrices. In our cohort, women tended to produce more microfloral metabolites with bread intervention. In men, isoflavone metabolite excretion was highly variable following soy bread and soy beverage interventions therefore differences due to food matrix were difficult to distinguish. Faughnan et al. administered isoflavones as a single dose in different food matrices (soymilk and textured vegetable protein) and with varied isoflavone composition (tempeh).39 Similar to the current study, they found that only female isoflavone excretion was affected by food matrix.39,40 Other studies have observed greater isoflavone excretion from women and improved hormone-related response to phytochemical ingestion than men.29, 66-69

Epidemiologic evidence have suggested that a diet rich in soy foods has shown potential promise in ameliorating risk of disease, specifically hormone-related cancers such as those affecting the prostate and breasts.70-71 However, among prospective dietary intervention studies investigating isoflavone efficacy, the significant variability may be masking the benefits of soy isoflavones.32,72 Recent studies have emerged addressing the relevance of inter-individual variations in isoflavone metabolism and formation of isoflavone metabolites as an explanation for the variability found in soy intervention studies.32 For instance, individuals capable of producing daidzein metabolites equol or ODMA have been associated with improved bone health26,31,73 and prostate health.74 Knowledge gained from this study may help reveal whether phenotypic responses to diet dictate risk of disease and health outcomes when consuming soy products.

Findings in this study reiterate the relevance of food matrices in discriminating isoflavone metabolism in women and warrant further exploration in designing food matrices that will optimize delivery to targeted tissues or discerning food processing strategies that will result in formation of specific metabolite profiles. Using differences in the physicochemical properties of food to help decipher isoflavone metabolite producing phenotypes could assist in identifying individuals who would benefit most from soy consumption.

Conclusions

In this crossover study the significant findings address the role of food matrix and gender on soy isoflavone metabolism. Daidzein metabolites (DHD, and ODMA) were produced more readily in women than in men after soy bread intervention, while men had no response to soy matrix. Additionally, 6-OH-ODMA, a metabolite of genistein not commonly investigated, was detected in the urine of some women. Future clinical studies using a single specific matrix with controlled phytochemical profiles of isoflavones are needed to decipher differences in isoflavone bioavailability and metabolism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dr. Dennis Pearl for his generous help with the statistical analyses of the urinary isoflavonoid and clinical data. This study was supported by Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Centre (OARDC) support of a SEED grant and The Centre for Advanced Functional Foods Research and Entrepreneurship, OSU Comprehensive Cancer Centre, The Nutrient and Phytochemical Analytic Shared Resource (NPASR), The Schoen Cancer Prevention Research Fund (246394), The National Institutes of Health support to The General Clinical Research Centre (M01-RR00034, National Centre of Research Resources), and National Cancer Institute support of R01 CA112632, R21 CA125909, and the Comprehensive Cancer Center Grant P30 CA16058.

References

- 1.Adlercreutz H. Western diet and western diseases: Some hormonal and biochemical mechanisms and associations. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl. 1990;201:3–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lissin LW, Cooke JP. Phytoestrogens and cardiovascular health. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:1403–10. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00590-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fournier DB, Erdman JW, Jr, Gordon GB. Soy, its components, and cancer prevention: A review of the in vitro, animal, and human data. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:1055–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Setchell KD, Lydeking-Olsen E. Dietary phytoestrogens and their effect on bone: Evidence from in vitro and in vivo, human observational and dietary intervention studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:593S–609. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.3.593S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matthan NR, Jalbert SM, Ausman LM, Kuvin JT, Karas RH, Lichtenstein AH. Effect of soy protein from differently processed products on cardiovascular disease risk factors and vascular endothelial function in hypercholesterolemic subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:960–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.4.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Welty FK, Lee KS, Lew NS, Zhou JR. Effect of soy nuts on blood pressure and lipid levels in hypertensive, prehypertensive, and normotensive postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1060–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.10.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Messina M, Nagata C, Wu AH. Estimated Asian adult soy protein and isoflavone intakes. Nutr Cancer. 2006;55:1–12. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5501_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Messina M. Western soy intake is too low to produce health effects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:528, 9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.2.528. author reply 529-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barrett JR. The science of soy: What do we really know? Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:352–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.114-a352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnes S, Peterson T, Coward L. Rationale for the use of genistein-containing soy matrices in chemoprevention trials for breast and prostate cancer. J Cell Biochem. 1995;(Supp 22):181–187. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240590823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golbitz P, Jordon J. Soyfoods: Market and products. In: Riaz MN, editor. Soy Applications in Food. CRC; Taylor & Francis; Boca Raton, Fla.: London: 2006. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golbitz P. Traditional soyfoods: Processing and products. J Nutr. 1995;125:570S–2S. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.suppl_3.570S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ricketts ML, Moore DD, Banz WJ, Mezei O, Shay NF. Molecular mechanisms of action of the soy isoflavones includes activation of promiscuous nuclear receptors. J Nutr Biochem. 2005;16:321–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Setchell KD, Cassidy A. Dietary isoflavones: Biological effects and relevance to human health. J Nutr. 1999;129:758S–67S. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.3.758S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anthony MS, Clarkson TB, Williams JK. Effects of soy isoflavones on atherosclerosis: Potential mechanisms. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68:1390S–3S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.6.1390S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crouse JR, 3rd, Morgan T, Terry JG, Ellis J, Vitolins M, Burke GL. A randomized trial comparing the effect of casein with that of soy protein containing varying amounts of isoflavones on plasma concentrations of lipids and lipoproteins. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2070–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.17.2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tikkanen MJ, Wahala K, Ojala S, Vihma V, Adlercreutz H. Effect of soybean phytoestrogen intake on low density lipoprotein oxidation resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3106–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Djuric Z, Chen G, Doerge DR, Heilbrun LK, Kucuk O. Effect of soy isoflavone supplementation on markers of oxidative stress in men and women. Cancer Lett. 2001;172:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00627-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cuevas AM, Irribarra VL, Castillo OA, Yanez MD, Germain AM. Isolated soy protein improves endothelial function in postmenopausal hypercholesterolemic women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57:889–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yildirir A, Tokgozoglu SL, Oduncu T, Oto A, Haznedaroglu I, Akinci D, Koksal G, Sade E, Kirazli S, Kes S. Soy protein diet significantly improves endothelial function and lipid parameters. Clin Cardiol. 2001;24:711–6. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960241105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takimoto CH, Glover K, Huang X, Hayes SA, Gallot L, Quinn M, Jovanovic BD, Shapiro A, Hernandez L, et al. Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analysis of unconjugated soy isoflavones administered to individuals with cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(1):1213–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lakshman M, Xu L, Ananthanarayanan V, Cooper J, Takimoto CH, Helenowski I, Pelling JC, Bergan RC. Dietary genistein inhibits metastasis of human prostate cancer in mice. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2024–32. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breinholt V, Hossaini A, Svendsen GW, Brouwer C, Nielsen E. Estrogenic activity of flavonoids in mice. the importance of estrogen receptor distribution, metabolism and bioavailability. Food Chem Toxicol. 2000;38:555–64. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(00)00046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kostelac D, Rechkemmer G, Briviba K. Phytoestrogens modulate binding response of estrogen receptors alpha and beta to the estrogen response element. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:7632–5. doi: 10.1021/jf034427b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frankenfeld CL, McTiernan A, Thomas WK, LaCroix K, McVarish L, Holt VL, Schwartz SM, Lampe JW. Postmenopausal bone mineral density in relation to soy isoflavone-metabolizing phenotypes. Maturitas. 2006;53:315–24. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Setchell KD, Brown NM, Lydeking-Olsen E. The clinical importance of the metabolite equol-a clue to the effectiveness of soy and its isoflavones. J Nutr. 2002;132:3577–84. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.12.3577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duncan AM, Merz-Demlow BE, Xu X, Phipps WR, Kurzer MS. Premenopausal equol excretors show plasma hormone profiles associated with lowered risk of breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:581–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tham DM, Gardner CD, Haskell WL. Potential health benefits of dietary phytoestrogens: A review of the clinical, epidemiological, and mechanistic evidence. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:2223–35. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.7.4752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu L, Anderson K. Sex and long-term soy diets affect the metabolism and excretion of soy isoflavones in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68:1500S–1504. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.6.1500S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heinonen S, Hoikkala A, Wähälä K, Adlercreutz H. Metabolism of the soy isoflavones daidzein, genistein and glycitein in human subjects. Identification of new metabolites having an intact isoflavonoid skeleton. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;87:285–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu X, Harris KS, Wang HJ, Murphy PA, Hendrich S. Bioavailability of soybean isoflavones depends upon gut microflora in women. J Nutr. 1995;125:2307–15. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.9.2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Atkinson C, Frankenfeld CL, Lampe JW. Gut bacterial metabolism of the soy isoflavone daidzein: Exploring the relevance to human health. Exp Biol Med. 2005;230:155–70. doi: 10.1177/153537020523000302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joannou GE, Kelly GE, Reeder AY, Waring M, Nelson C. A urinary profile study of dietary phytoestrogens. the identification and mode of metabolism of new isoflavonoids. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1995;54:167–84. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(95)00131-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.King RA, Bursill DB. Plasma and urinary kinetics of the isoflavones daidzein and genistein after a single soy meal in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67:867–72. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.5.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang YC, Nair MG. Metabolism of daidzein and genistein by intestinal bacteria. J Nat Prod. 1995;58:1892–6. doi: 10.1021/np50126a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turner NJ. Bioactive isoflavones in functional foods: The importance of gut microflora on bioavailability. Nutr Rev. 2003;61:204–13. doi: 10.1301/nr.2003.jun.204-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu X, Wang HJ, Murphy PA, Hendrich S. Neither background diet nor type of soy food affects short-term isoflavone bioavailability in women. J Nutr. 2000;130:798–801. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.4.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Pascual-Teresa S, Hallund J, Talbot D, Schroot J, Williams CM, Bugel S, Cassidy A. Absorption of isoflavones in humans: Effects of food matrix and processing. J Nutr Biochem. 2006;17:257–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Faughnan M, Hawdon A, Ah-Singh E, Brown J, Millward DJ, Cassidy A. Urinary isoflavone kinetics: The effect of age, gender, food matrix and chemical composition. Br J Nutr. 2004;91:567–74. doi: 10.1079/BJN20041087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cassidy A, Brown J, Hawdon A, Faughnan M, King LJ, Millward J, Zimmer-Nechemias L, Wolfe B, Setchell KDR. Factors affecting the bioavailability of soy isoflavones in humans after ingestion of physiologically relevant levels from different soy foods. J Nutr. 2006;136:45–51. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang H, Liang H, Kwok K. Effect of thermal processing on genistein, daidzein and glycitein content in soymilk. J Sci Food Agric. 2006;86:1110–4. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coward L, Smith M, Kirk M, Barnes S. Chemical modification of isoflavones in soy foods during cooking and processing. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68:1486S–91S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.6.1486S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang HJ, Murphy PA. Mass balance study of isoflavones during soybean processing. J Agric Food Chem. 1996;44:2377–83. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murphy PA, Barua K, Hauck CC. Solvent extraction selection in the determination of isoflavones in soy foods. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2002;777:129–38. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(02)00342-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Achouri A, Boye IJ, Belanger D. Soybean isoflavones: Efficacy of extraction conditions and effect of food type on extractability. Food Res Intern. 2005;38:1199–204. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Busby MG, Jeffcoat AR, Bloedon LT, Koch MA, Black T, Dix KJ, Heizer WD, Thomas BF, Hill JM, et al. Clinical characteristics and pharmacokinetics of purified soy isoflavones: Single-dose administration to healthy men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75:126–36. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.1.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang H, Murphy PA. Isoflavone content in commercial soybean foods. J Agric Food Chem. 1994;42:1666–73. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Franke AA, Custer LJ, Wilkens LR, Le Marchand LL, Nomura AM, Goodman MT, Kolonel LN. Liquid chromatographic-photodiode array mass spectrometric analysis of dietary phytoestrogens from human urine and blood. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2002;777:45–59. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(02)00216-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Allain CC, Poon LS, Chan CSG, Richmond W, Fu PC. Enzymatic determination of total serum cholesterol. Clin Chem. 1974;20:470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bucolo G, David H. Quantitative determination of serum triglycerides by the use of enzymes. Clin. Chem. 1973;19:476–482. 1973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Contois JH, McNamara JR, Lammi-Keefe CJ, Wilson PWF, Massov T, Schaefer EJ. Reference intervals for plasma apolipoprotein B determined with a standardized commercial immunoturbidimetric assay: results from the Framingham Offspring Study. Clin Chem. 1996;42:515–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Contois JH, McNamara JR, Lammi-Keefe CJ, Wilson PWF, Massov T, Schaefer EJ. Reference intervals for plasma apolipoprotein A-1 determined with a standardized commercial immunoturbidimetric assay: results from the Framingham Offspring Study. Clin Chem. 1996;42:507–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hadley CW, Clinton SK, Schwartz SJ. The consumption of processed tomato products enhances plasma lycopene concentrations in association with a reduced lipoprotein sensitivity to oxidative damage. J Nutr. 2003;133:727–32. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.3.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Common Terminology Criteria [Internet] Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program; Bethesda: [updated 2010 Feb 26; cited 2010 May 16]. c2003-2010. Available from: http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcaev3.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Messina MJ. Legumes and soybeans: overview of their nutritional profiles and health effects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:439S–50S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.3.439s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Coward L, Barnes NC, Setchell KD, Barnes S. Genistein, daidzein, and their beta.-glycoside conjugates: Antitumor isoflavones in soybean foods from American and Asian diets. J Agric Food Chem. 1993;41:1961–7. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Steinberg FM, Guthrie NL, Villablanca AC, Kumar K, Murray MJ. Soy protein with isoflavones has favorable effects on endothelial function that are independent of lipid and antioxidant effects in healthy postmenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:123–30. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Food and Drug Administration, Health and Human Services Food labeling: Health claims; soy protein and coronary heart disease: Final rule. Fed Reg. 1999;64:57699–57733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang Y, Wang G, Song TT, Murphy PA, Hendrich S. Urinary disposition of the soybean isoflavones daidzein, genistein and glycitein differs among humans with moderate fecal isoflavone degradation activity. J Nutr. 1999;129:957–62. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.5.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kelly GE, Joannou GE, Reeder AY, Nelson C, Waring MA. The variable metabolic response to dietary isoflavones in humans. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1995;208:40–3. doi: 10.3181/00379727-208-43829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Franke AA, Ashburn LA, Kakazu K, Suzuki S, Wilkens LR, Halm BM. Apparent bioavailability of isoflavones after intake of liquid and solid soya foods. Br J Nutr. 2009;102:1203–10. doi: 10.1017/S000711450937169X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rowland I, Wiseman H, Sanders T, Adlercreutz H, Bowey E. Metabolism of oestrogens and phytoestrogens: Role of the gut microflora. Biochem Soc Trans. 1999;27:304–8. doi: 10.1042/bst0270304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Heinonen S. Identification of isoflavone metabolites dihydrodaidzein, dihydrogenistein, 6′-OH-O-dma, and cis-4-OH-equol in human urine by gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy using authentic reference compounds. Anal Biochem. 1999;274:211–9. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jenkins DJ, Wolever TM, Leeds AR, Gassull MA, Haisman P, Dilawari J, Goff DV, Metz GL, Alberti KG. Dietary fibres, fibre analogues, and glucose tolerance: Importance of viscosity. Br Med J. 1978;1:1392–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6124.1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zheng Y, Hu J, Murphy PA, Alekel DL, Franke WD, Hendrich S. Rapid gut transit time and slow fecal isoflavone disappearance phenotype are associated with greater genistein bioavailability in women. J Nutr. 2003;133:3110–6. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.10.3110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kurzer MS. Hormonal effects of soy in premenopausal women and men. J Nutr. 2002;132:570S–3S. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.3.570S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lu LW, Lin S, Grady JJ, Nagamani M, Anderson KE. Altered kinetics and extent of urinary daidzein and genistein excretion in women during chronic soya exposure. Nutr Cancer. 1996;26:289–302. doi: 10.1080/01635589609514485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bloedon LT, Jeffcoat AR, Lopaczynski W, Schell MJ, Black TM, Dix KJ, Thomas BF, Albright C, Busby MG, Crowell JA, Zeisel SH. Safety and pharmacokinetics of purified soy isoflavones: single-dose administration to postmenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:1126–37. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.5.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Castle EP, Thrasher JB. The role of soy phytoestrogens in prostate cancer. Urol Clin North Am. 2002;29:71–81. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(02)00019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Trock BJ, Hilakivi-Clarke L, Clarke R. Meta-analysis of soy intake and breast cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:459–71. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sirtori CR. Risks and benefits of soy phytoestrogens in cardiovascular diseases, cancer, climacteric symptoms and osteoporosis. Drug Safety. 2001;24:665–682. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200124090-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Frankenfeld CL, Atkinson C, Thomas WK, Gonzalez A, Jokela T, Schwartz SM, Wähälä K, Li SS, Lampe JW. Familial aggregation of daidzein-metabolizing phenotypes (poster abstracts) J Nutr. 2004;134:1284S–5S. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Akaza H, Miyanaga N, Takashima N, Naito S, Hirao Y, Tsukamoto T, Fujioka T, Mori M, Kim W, et al. Comparisons of percent equol producers between prostate cancer patients and controls: Case-controlled studies of isoflavones in Japanese, Korean and American residents. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2004;34:86–9. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyh015. 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.