Abstract

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is an extracellular scaffold composed of complex mixtures of proteins that plays a pivotal role in tumor progression. ECM remodeling is crucial for tumor migration and invasion during the process of metastasis. ECM can be remodeled by several processes including synthesis, contraction and proteolytic degradation. In order to cross through the ECM barriers, malignant cells produce a spectrum of extracellular proteinases including matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), serine proteases (mainly the urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) system) and cysteine proteases to degrade ECM components. As major adhesion molecules to support cell attachment to ECM, integrins play critical roles in tumor progression by enhancing tumor cell survival, migration and invasion. Previous studies have shown that integrins can regulate the expression and activity of these proteases through different pathways. This review summarizes the roles of MMPs and uPA system in ECM remodeling and discusses the regulatory functions of integrins on these proteases in invasive tumors.

Keywords: ECM remodeling, Metastasis, Integrins, MMPs, uPA system

Introduction

ECM, a key component of the microenvironment, plays a pivotal role in tumor pathogenesis and progression. It is a complex assembly of many proteins such as fibrous structural proteins and proteoglycans, forming an elaborate network within tissues [1, 2]. ECM is not only a simple static scaffold, but also can be modified through remodeling to create an environment for tumor metastasis [3].

Metastasis is the leading cause of cancer mortality, by which cancer cells leave from the primary tumor, disseminate and settle at distant sites to form secondary tumors. The metastatic cascade is very complicated and remains poorly understood. Generally, the process can be summarized as follows: 1) formation of new blood vessels for the growing tumor; 2) release of tumor cells from the primary site; 3) invasion and migration through the barriers of epithelial basement membrane and surrounding ECM; 4) invasion into the vasculature; 5) adhesion to endothelial cells and extravasation; 6) formation of metastatic tumors at the new sites [4–6].

ECM remodeling is important for many development processes and contributes to tumor metastasis [3, 7]. ECM can be remodeled by several processes including synthesis, contraction and proteolytic degradation [3]. As a barrier to progressing tumor cells, their surrounding ECM must be degraded to facilitate the metastasis of invasive tumor [8]. The ECM can be degraded directly by proteases including MMPs, serine proteases (mainly the uPA system) and cysteine proteases, or indirectly in response to signals transduced by ECM receptors [7]. In metastatic tumors, the protease activity and those signals are often dysregulated.

Cells sense and respond to the changes in ECM via integrins. Integrins are a family of heterodimeric trans-membrane adhesion receptors comprising α and β subunits. In vertebrates, 18 α and 8 β subunits give rise to at least 24 different heterodimers recognizing distinct but often overlapping ligands (Fig. 1) [9–11]. As important adhesion molecules, integrins mediate cell-cell, cell-ECM, cell-pathogen interactions and bidirectional signaling across the plasma membrane and involve in various cell functions such as differentiation, migration and survival [11, 12]. Previous studies have demonstrated that integrins can promote metastasis by modulating the proteolytic enzymes [13, 14]. Thus, understanding the interplay between integrins and ECM remodeling proteases is one of the major challenges in cancer research. In this review, we will summarize the role of integrins on regulating the function of proteases and discuss the mechanism.

Fig. 1.

Integrin family. Integrins may be loosely grouped into two classes that bind to ECM ligands and cell surface cell adhesion molecules (CAMs). Integrins that recognize ECM ligands can be further classified into three groups as laminin receptors, collagen receptors and RGD receptors

Overview of Integrin Functions in Tumor Metastasis

Cells attach to the ECM via integrins [15]. Upon ligand binding, integrins transduce the extracellular cues from the ECM to intracellular cytoskeleton, a process called “outside-in signaling” [16]. Inversely, the binding of intracellular proteins such as talin and kindlin to the cytoplasmic tails of integrin triggers the conformational changes and activation of integrin, which is termed “inside-out signaling” [16]. The bidirectional signaling involves assembly and disassembly of numerous components that form around the cytoplasmic tail of integrins [17]. The adhesion complexes formed by integrin is known as “integrin adhesome”, which consists of at least 156 components interlinked by hundreds of interactions [18, 19]. Among the components of adhesome, talin, paxillin, filamin, integrin-linked kinase (ILK) and focal adhesion kinase (FAK) have prominent functions [16].

Extensive studies have revealed that alterations of integrin expression and function are frequently found in most human cancers [20–23]. In particular, integrins have been implicated in all steps of tumor metastasis [13, 24]. Angiogenesis, providing oxygen and nutrients to the rapidly proliferating tumor cells, has essential roles in tumor metastasis [25]. Several integrins are involved in angiogenesis, such as αVβ3, αVβ5 and α5β1 [26, 27]. Antagonists of these integrins can block tumor induced angiogenesis in multiple animal models and have clinical benefits in humans with solid tumors [26, 27]. Abnormal migration is one crucial step during the metastasis of malignant tumor cells [28]. Integrins play critical roles in regulating protrusion and adhesion in migrating cells [29]. For example, the integrin downstream FAK signaling is necessary for directional cell movement [30]. FAK functions as an integrin-regulated scaffold to recruit Src to focal adhesion, targeting several pathways to promote cell migration [30]. Rho GTPases mediate modifications of the actin cytoskeleton required for cell migration and promote the assembly of integrin based matrix adhesion complexes to generate traction forces at the front and in the body of the migratory cells [31].

To metastasize to a distant organ, tumor cells must invade the surrounding ECM barriers, which need to be degraded and remodeled by multiple proteases. Integrins have been shown to regulate the expression and activity of those proteases especially MMPs and uPA system, which will be elaborated in the following sections.

MMPs

Characteristics of MMPs

Efficient tumor invasion and metastasis require degradation of the ECM at the invasion front. As the main proteases involved in remodeling ECM, MMPs play a pivotal role in remodeling tumor microenvironment [32, 33].

MMPs are a large family of zinc-dependent endopeptidases, which include 25 members in vertebrate categorized into eight structure classes by their architectural features [32–34]. In general, three domains are common to almost all MMPs, the pro-peptide for enzyme latency, the catalytic domain, and the hemopexin-like C-terminal domain [33]. MMPs can be divided into two groups, the membrane-anchored type (MT-MMPs) and the secreted type [35]. MMPs are synthesized as zymogens and activated by proteinase cleavage to remove the auto-inhibitory domain [33]. And their activity can be down-regulated by endogenous inhibitors like tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs), α2-macroglobulin, and the membrane-bound inhibitor reversion-inducing cysteine-rich protein with kazal motifs (RECK) [36]. TIMPs are best-studied endogenous inhibitors of MMPs. In the ECM, TIMPs bind to the active site of the MMPs in a stoichiometric 1:1 molar ratio, thereby inhibiting the proteolytic activity of MMPs [37]. Four types of TIMPs (TIMP-1, -2, -3, and -4) are present in humans [37], and individual TIMPs differ in tissue-specific expression and ability to inhibit various MMPs [37].

MMPs have broad substrate specificities for a variety of ECM components, such as collagen, laminin and fibronectin [38]. Besides, they can also target cell surface molecules and other non-matrix proteins [38]. Thus, MMPs serve as the key molecular messengers between tumor and stroma. In addition to degrade physical ECM barriers, MMPs can interact with cell surface receptors such as integrins to affect multiple signaling pathways that modulate the biology of cells in both physiological and pathological processes [39]. For example, leukocyte migration is known to be dependent on MMPs and β2 integrin interaction, and the combined participation of MMPs and integrins is also required for tumor metastasis [39, 40]. Moreover, MMPs mediate a wide range of biological effects that contribute to tumor cell invasion and metastasis [33]. MMPs can affect growth signals by proteolytically activating TGF-β to selectively promote stroma-mediated tumor invasion and metastasis [41, 42]. They can also interfere with the induction of apoptosis in malignant cells by cleavage of the ligands/receptors that transduce pro-apoptotic signals [33, 43].

The activity of MMPs can be regulated at different levels including gene expression, localization, switch from zymogen to active form, and inactivation by specific inhibitors [33]. Notably, integrins play prominent roles in all of these regulation levels.

Up-Regulation of MMPs Expression by Integrins

The expression level of MMPs is always elevated in the circumstance of tumor [33]. MMP gene expression is regulated by numerous stimulatory and suppressive factors that influence multiple signaling pathways [38]. Integrin is one of the most important regulatory factors. Upon binding to ECM, integrins can activate MMP synthesis and then up-regulate the expression of MMPs. Some αV [44–48] and β1 [49–52] integrins have been shown to promote the expression of several MMPs. For example, integrin αVβ6 has been shown to promote the expression of MMPs in various cancers [44–47]. In oral squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), increased αVβ6 leads to the activation of MMP-3 and promote oral SCC cell proliferation and metastasis in vivo [44]. Upon bound to fibronectin, αVβ6 complexes with Fyn and leads to its activation. Subsequently, the activated Fyn recruits and activates FAK, which is necessary to activate Shc and couple αVβ6 signaling to the Raf-ERK/MAPK pathway, thus transcriptionally activates MMP-3 gene [44]. Besides, the high expression of αVβ6 integrin in ovarian cancer cells correlates with increased expression and secretion of pro-MMP-2, pro-MMP-9 and high molecular weight (HMW)-uPA for ECM degradation [45]. Another αV integrin, αVβ3, is found to up-regulate MMP-2 expression in invasive breast cancer cell once the integrin binds RGD peptide [48]. Two collagen receptors, integrin α1β1 and α2β1, have been reported to induce MMP-13 expression in a p38 MAPK dependent manner in human skin fibroblasts cultured in three dimensional collagen [49]. While in v-Src transformed fibroblast, the expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 are up-regulated through the β1 integrin-FAK-JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinase) signaling pathway [50]. As a cell adhesion receptor for laminin 5, integrin α3β1 has been shown to be required for MMP-9 secretion and potentiate TGF-β mediated induction of MMP-9 in immortalized keratinocytes [51, 52].

Regulation of MMPs Localization by Integrins

The physical location of MMPs dictates their biological functions and is fundamental to the physiological roles of these enzymes in tumor progression. The compartmentalization of MMPs to cell surface can be achieved by the expression of MT-MMPs which directly anchor to cell membrane [53–55] or binding to cell surface docking receptors such as integrins [40, 56, 57], CD147 [58] and CD44 [41, 59]. In the process of tumor invasion, degradation of ECM occurs at specific sites where invasive cells make contact with ECM through specialized cell membrane protrusions called invadopodia [60]. Invadopodial protrusions are enriched in integrins, MMPs, tyrosine kinase signaling machinery, actin, and actin-associated proteins [60]. Membrane type 1 metalloprotease (MT1-MMP, MMP14) is one key invadopodial protease that co-localizes with integrin αVβ3 [61]. The high local concentration of active MT1-MMP on cell membrane has been shown to promote tumor metastasis [62]. Localization to cell membrane through the interaction with integrins has been demonstrated for multiple MMPs, including binding of MMP-2 to αVβ3 [40], and MMP-9 to αVβ6 or α3β1 [56, 57]. Specifically, MMP-2 is recruited to cell surface via binding to αVβ3 through its C-terminus hemopexin domain, which results in the ECM degradation to promote invasion of tumor cells [40]. Another study on colon cancer metastasis to liver has shown that the MMP-9 expression is elevated and co-localized with integrin αVβ6 at the invading edge of the tumor [56]. As a matter of fact, the activity of MMPs is dependent on integrin expression and its ligand-binding ability since treatment of a malignant breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 with a function-blocking anti-α3 antibody results in a marked reduction in MMP-9 activity, leading to inhibited migration and invasion [57].

MMPs Activation Requires Integrin

MMPs are first synthesized as inactive zymogens called pro-MMPs [32, 33]. Conversion of the zymogen into an active protease is a key step in regulating MMP activity [32, 33]. MMP-2 is often constitutively expressed and is activated at cell surface through a unique multistep pathway [63]. First, TIMP-2 binds MT1-MMP at its amino terminus and pro-MMP-2 at its carboxyl terminus. Next, the bound pro-MMP-2 is cleaved by an adjacent TIMP-2-free MT1-MMP to the intermediate form, and another already activated MMP-2 is required to remove a residual portion of the MMP-2 pro-peptide which leads to conversion of pro-MMP2 to a fully active enzyme [63, 64]. Besides, there is another alternative TIMP-2-independent pathway for MMP-2 activation [65]. Studies on melanomas, gliomas, lung and breast cancer cells indicate that this multi-protein MMP activating complex also includes integrin αVβ3, an receptor for RGD-containing components of ECM, such as vitronectin, fibronectin and thrombospondin [63, 66–69]. MT1-MMP and integrin αVβ3 may jointly enforce efficient docking, activation, and maturation of MMP-2, and then strongly facilitate tumor cell migration [63, 69]. Integrin αVβ3 is found up-regulated in glioblastomas and malanomas [70, 71]. Evidence showed that αVβ3 can promote tumor invasion and metastasis through recruiting and activating MMP-2 and plasmin [72], whereas disruption of MMP-2-αVβ3 binding inhibits angiogenesis and tumor growth [73]. The active MMP-2 can cleave type IV collagen and lead to the exposure of a cryptic site for αVβ3 binding. As a result, the increased MMP2-αVβ3 binding will facilitate angiogenesis and tumor growth [74].

Inhibition of MMPs Activity

The balanced MMPs activity is required to prevent excessive ECM degradation. The proteolytic activity of MMPs is down-regulated primarily by TIMPs [37]. Experimental evidences have shown that the inhibition of MMPs by TIMPs may reduce or even abolish tumor metastasis [75, 76]. However, the relationship between MMPs and TIMPs in tumor development is elusive since TIMPs is sometimes up-regulated with the over-expression of individual MMPs [77, 78]. In the serum of patients with lung carcinomas, both MMP-9 and TIMP-1 have been found elevated [78]. In addition to TIMPs, a naturally occurring form of the C-terminus hemopexin domain from MMP-2 can be detected in association with αVβ3 expression in tumors [79]. This hemopexin domain can compete with MMP-2 to bind integrin αVβ3, serving as a natural inhibitor of MMP-2 activity to prevent excessive angiogenesis [79].

uPA System

Introduction of uPA System

The uPA system represents a family of serine proteases that are involved in the degradation of ECM, which plays important roles in a variety of biologic processes, including fibrinolysis [80], inflammation [81], ECM remodeling during tumor invasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis [82–84].

The uPA system includes uPA, glycolipid-anchored uPA receptor (uPAR), and plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 and 2 (PAI-1 and PAI-2) [85, 87]. Binding of uPA zymogen (pro-uPA) to uPAR leads to uPA activation [85–87]. In the other hand, uPA activity is rapidly neutralized by its specific inhibitors, PAI-1 and PAI-2 [85–87]. Activated uPA initiates a proteolytic cascade that results in the conversion of a zymogen called plasminogen to protease plasmin, which can degrade a range of ECM components and activate other proteases such as MMPs [88, 89]. These proteolytic cascades degrade ECM to allow cells cross through the ECM barriers, and in addition, release various growth and differentiation factors, which contribute to the migratory and invasive phenotype characteristic of malignant tumor cells [90].

Recent findings suggest that uPA system is frequently involved at multiple steps in tumor progression, particularly in remodeling ECM, modulating cell adhesion and enhancing cell proliferation and migration [84, 87]. Consistent with its role in tumor progression, several groups have shown that over-expression of uPA or uPAR is a feature of malignancy and is correlated with tumor progression and metastasis [84, 85, 91, 92]. The uPA system has been suggested as a promising candidate for targeted cancer therapy [93].

Integrins are essential uPAR signaling co-receptors and a second uPAR ligand [86]. The uPA system is intimately connected to integrins in following aspects: 1) integrins regulate the expression of uPA system; 2) integrins regulate the localization of uPA system; 3) integrins promote the signaling mediated by uPA system and vice versa. The following sections will give a general review on the above aspects.

Regulation of uPA System Expression by Integrins

Evidence for physical and functional association between integrins and uPAR is also provided by observations that integrin-dependent signaling events regulate the expression of the components of uPA system [94]. Binding of an RGD-bearing ligand to integrin αVβ3 in metastatic murine mammary cancer cells transcriptionally up-regulates uPA expression through ILK-dependent AP-1 activation [95]. In another case, ligand-induced clustering of integrin α3β1 promotes uPAR-α3β1 interaction and enhances uPA expression in a Src-ERK-dependent pathway [96]. uPAR expression can also be up-regulated by integrins. It is reported that the ligation of either β1 or β2 integrins with T cell receptors results in robust up-regulation of uPAR expression in primary T lymphocytes [97].

Regulation of uPA/uPAR Localization by Integrins

To assure the spatial control over ECM degradation, uPAR is localized to the leading edge of migrating cells which focuses uPA activity in the direction of cell movement [98]. The mechanism that governs the spatial localization of uPAR on the cell surface appears to depend on the association of uPAR with uPA, integrins and the ECM protein vitronectin [83, 87]. Similar to MMPs, uPAR is often found clustered with integrins within invadopodia [99]. Evidence has shown that uPAR localizes to integrin-containing adhesion complexes, and interacts with integrins [86]. Up to now, uPAR has been found to physically and functionally associated with several β1 [96, 100], β2 [101, 102], and αV [103, 104] integrins, which can recruit uPA/uPAR to the cell surface [87, 105]. A good example is that uPA and uPAR are associated with integrin αVβ3, which recruits them to the leading edge of migrating tumor cells for ECM degradation [106].

Integrins Are uPAR Signaling Co-Receptors

In addition to regulating proteolysis, uPAR also serves as a signaling receptor to promote cell proliferation, survival, migration, and invasion [86]. Due to lacking transmembrane and intracellular domains, uPAR requires transmembrane co-receptors for signaling. Considerable evidences suggest that integrins are essential uPAR signaling co-receptors, and several integrins have been shown to work with uPAR [96, 101, 107–112]. αMβ2 is the first integrin found to interact with uPAR, which cooperates with uPAR to mediate leukocytes adhesion and recruitment during inflammatory responses in an uPA-independent signaling pathway [101, 107]. Recent studies suggest that uPAR signals through αVβ3 play important roles in cell migration and invasion. The uPAR-αVβ3 interaction can activate the Rho family GTPase, which stimulate actin polymerization and membrane protrusion, and promote cell migration and invasion [108, 109]. uPAR can also interact with integrin α3β1 and α5β1. These uPAR-β1 integrin interactions stimulate FAK-Src and lead to downstream activation of Ras-MAPK pathway, which promotes tumor cell proliferation and tumor invasion [96, 110, 111]. Either the disruption of uPAR-α5β1 interaction or down-regulation of uPAR can induce tumor growth arrest (dormancy) in vivo [112].

Conclusions and Perspectives

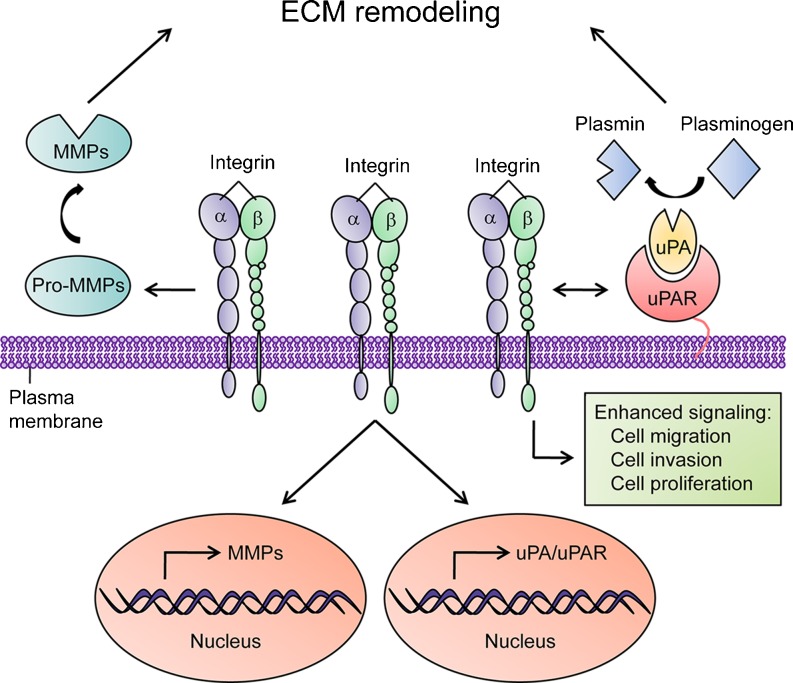

Degradation of ECM at the invasion front of tumor cells is critical for efficient tumor invasion and metastasis. Proteases such as MMPs and uPA system play pivotal roles in remodeling tumor microenvironment. Components from both MMPs and uPA system are found up-regulated or over-activated in various cancers, seen as a feature of malignancy and are correlated with tumor progression and metastasis. Integrins represent a major family of receptors that mediate cell adhesion to ECM, and also play critical roles in tumor progression by enhancing tumor cell invasion, metastasis, and survival. Integrins serve as the key regulators of MMPs and uPA system (Fig. 2). For MMPs, integrins can activate MMP synthesis at the transcriptional level, compartmentalize them to cell surface for the spatial ECM degradation, and promote the activation of pro-MMPs. For uPA system, integrins can enhance the expression of uPA/uPAR and govern the spatial localization of uPA/uPAR to the leading edge of migrating cells. Besides, as the co-receptor of uPAR signaling, integrin cooperates with uPAR to transduce multiple signals that contribute to tumor-related events. However, there are still a number of questions remain elusive. Is the integrin binding required by the maturation of all latent MMPs? Can MMPs transduce signals into cells via their binding to integrins? Do integrin affinity and avidity affect its interaction with MMPs and uPAR? It will be interesting to address these questions in the future.

Fig. 2.

The regulatory functions of integrins on MMPs and uPA system. MMPs: integrins can activate MMPs synthesis at the transcriptional level, compartmentalize them to cell surface for the spatial ECM degradation, and promote the activation of pro-MMPs. uPA system: integrins can enhance the expression of uPA/uPAR and govern the spatial localization of uPA/uPAR to the leading edge of migrating cells. Besides, integrins cooperate with uPAR to transduce multiple signals that contribute to tumor-related events including cell migration, invasion and proliferation

Over the past years, a lot of efforts have been made to design MMP inhibitors (MPIs), and synthetic MPIs were rapidly developed and applied in human clinical trials. However, the results of these clinical trials have been disappointing [113]. Based on the findings that integrins can promote functions of MMPs, more effective cancer therapeutics could be achieved by interfering with MMPs association with integrins. In the other hand, it is reported that individual components of the uPA system are distinctly expressed in tumor tissues compared with normal tissues, thus they present multiple opportunities for therapeutic targets. The anti-uPAR therapeutic agents are yet to enter clinical trials, which might be advantageous in cancer therapy [86, 114]. Besides, there would be attractive targets for new drugs to block tumor progression or metastasis considering the interactions between uPAR and integrins.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Basic Research Program of China (2010CB529703), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31190061, 30700119, 30970604), Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (11JC1414200) and the Shanghai Pujiang Program (08PJ1410600).

Disclosures

There are no financial disclosures or conflicts of interests regarding the preparation of this manuscript.

Glossary

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- MMP

Matrix metalloproteinase

- uPA

Urokinase plasminogen activator

- CAM

Cell adhesion molecule

- ILK

Integrin-linked kinase

- FAK

Focal adhesion kinase

- MT-MMP

Membrane-anchored type matrix metalloproteinase

- TIMP

Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase

- RECK

Reversion-inducing cysteine-rich protein with kazal motifs

- SCC

Squamous cell carcinoma

- HMW

High molecular weight

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- uPAR

uPA receptor

- PAI

Plasminogen activator inhibitor

- MPI

MMP inhibitor

References

- 1.Jean C, Gravelle P, Fournie JJ, Laurent G. Influence of stress on extracellular matrix and integrin biology. Oncogene. 2011;30(24):2697–2706. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shin S, Wolgamott L, Yoon SO. Integrin trafficking and tumor progression. Int J Cell Biol. 2012;2012:516789. doi: 10.1155/2012/516789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larsen M, Artym VV, Green JA, Yamada KM. The matrix reorganized: extracellular matrix remodeling and integrin signaling. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18(5):463–471. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooks SA, Lomax-Browne HJ, Carter TM, Kinch CE, Hall DM. Molecular interactions in cancer cell metastasis. Acta Histochem. 2010;112(1):3–25. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2008.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chambers AF, Groom AC, MacDonald IC. Dissemination and growth of cancer cells in metastatic sites. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(8):563–572. doi: 10.1038/nrc865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fidler IJ. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: the ‘seed and soil’ hypothesis revisited. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(6):453–458. doi: 10.1038/nrc1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daley WP, Peters SB, Larsen M. Extracellular matrix dynamics in development and regenerative medicine. J Cell Sci. 2008;121(Pt 3):255–264. doi: 10.1242/jcs.006064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pupa SM, Menard S, Forti S, Tagliabue E. New insights into the role of extracellular matrix during tumor onset and progression. J Cell Physiol. 2002;192(3):259–267. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Humphries JD, Byron A, Humphries MJ. Integrin ligands at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2006;119(Pt 19):3901–3903. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Staunton DE, Lupher ML, Liddington R, Gallatin WM. Targeting integrin structure and function in disease. Adv Immunol. 2006;91:111–157. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)91003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110(6):673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luo BH, Carman CV, Springer TA. Structural basis of integrin regulation and signaling. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:619–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.White DE, Muller WJ. Multifaceted roles of integrins in breast cancer metastasis. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2007;12(2–3):135–142. doi: 10.1007/s10911-007-9045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hood JD, Cheresh DA. Role of integrins in cell invasion and migration. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(2):91–100. doi: 10.1038/nrc727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo BH, Springer TA. Integrin structures and conformational signaling. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18(5):579–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anthis NJ, Campbell ID. The tail of integrin activation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011;36(4):191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harburger DS, Calderwood DA. Integrin signalling at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2009;122(Pt 2):159–163. doi: 10.1242/jcs.018093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaidel-Bar R, Itzkovitz S, Ma’ayan A, Iyengar R, Geiger B. Functional atlas of the integrin adhesome. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(8):858–867. doi: 10.1038/ncb0807-858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Humphries JD, Byron A, Bass MD, Craig SE, Pinney JW, Knight D, Humphries MJ. Proteomic analysis of integrin-associated complexes identifies RCC2 as a dual regulator of Rac1 and Arf6. Sci Signal. 2009;2(87):ra51. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Folgiero V, Bachelder RE, Bon G, Sacchi A, Falcioni R, Mercurio AM. The alpha6beta4 integrin can regulate ErbB-3 expression: implications for alpha6beta4 signaling and function. Cancer Res. 2007;67(4):1645–1652. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kielosto M, Nummela P, Jarvinen K, Yin M, Holtta E. Identification of integrins alpha6 and beta7 as c-Jun- and transformation-relevant genes in highly invasive fibrosarcoma cells. Int J Cancer. 2009;125(5):1065–1073. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Desgrosellier JS, Barnes LA, Shields DJ, Huang M, Lau SK, Prevost N, Tarin D, Shattil SJ, Cheresh DA. An integrin alpha(v)beta(3)-c-Src oncogenic unit promotes anchorage-independence and tumor progression. Nat Med. 2009;15(10):1163–1169. doi: 10.1038/nm.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao R, Liu XQ, Wu XP, Liu YF, Zhang ZY, Yang GY, Guo S, Niu J, Wang JY, Xu KS. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) enhances gastric carcinoma invasiveness via integrin alpha(v)beta6. Cancer Lett. 2010;287(2):150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Felding-Habermann B, O’Toole TE, Smith JW, Fransvea E, Ruggeri ZM, Ginsberg MH, Hughes PE, Pampori N, Shattil SJ, Saven A, Mueller BM. Integrin activation controls metastasis in human breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(4):1853–1858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ribatti D. Novel angiogenesis inhibitors: addressing the issue of redundancy in the angiogenic signaling pathway. Cancer Treat Rev. 2011;37(5):344–352. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eliceiri BP, Cheresh DA. Adhesion events in angiogenesis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13(5):563–568. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00252-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hynes RO. A reevaluation of integrins as regulators of angiogenesis. Nat Med. 2002;8(9):918–921. doi: 10.1038/nm0902-918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palmer TD, Ashby WJ, Lewis JD, Zijlstra A. Targeting tumor cell motility to prevent metastasis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2011;63(8):568–581. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huttenlocher A, Horwitz AR. Integrins in cell migration. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3(9):a005074. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo M, Guan JL. Focal adhesion kinase: a prominent determinant in breast cancer initiation, progression and metastasis. Cancer Lett. 2010;289(2):127–139. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raftopoulou M, Hall A. Cell migration: Rho GTPases lead the way. Dev Biol. 2004;265(1):23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sternlicht MD, Werb Z. How matrix metalloproteinases regulate cell behavior. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:463–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kessenbrock K, Plaks V, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases: regulators of the tumor microenvironment. Cell. 2010;141(1):52–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Egeblad M, Werb Z. New functions for the matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(3):161–174. doi: 10.1038/nrc745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCawley LJ, Matrisian LM. Matrix metalloproteinases: multifunctional contributors to tumor progression. Mol Med Today. 2000;6(4):149–156. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(00)01686-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baker AH, Edwards DR, Murphy G. Metalloproteinase inhibitors: biological actions and therapeutic opportunities. J Cell Sci. 2002;115(Pt 19):3719–3727. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brew K, Nagase H. The tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs): an ancient family with structural and functional diversity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1803(1):55–71. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stamenkovic I. Matrix metalloproteinases in tumor invasion and metastasis. Semin Cancer Biol. 2000;10(6):415–433. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2000.0379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stefanidakis M, Koivunen E. Cell-surface association between matrix metalloproteinases and integrins: role of the complexes in leukocyte migration and cancer progression. Blood. 2006;108(5):1441–1450. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-005363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brooks PC, Stromblad S, Sanders LC, Schalscha TL, Aimes RT, Stetler-Stevenson WG, Quigley JP, Cheresh DA. Localization of matrix metalloproteinase MMP-2 to the surface of invasive cells by interaction with integrin alpha v beta 3. Cell. 1996;85(5):683–693. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81235-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu Q, Stamenkovic I. Cell surface-localized matrix metalloproteinase-9 proteolytically activates TGF-beta and promotes tumor invasion and angiogenesis. Genes Dev. 2000;14(2):163–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mu D, Cambier S, Fjellbirkeland L, Baron JL, Munger JS, Kawakatsu H, Sheppard D, Broaddus VC, Nishimura SL. The integrin alpha(v)beta8 mediates epithelial homeostasis through MT1-MMP-dependent activation of TGF-beta1. J Cell Biol. 2002;157(3):493–507. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200109100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mitsiades N, Yu WH, Poulaki V, Tsokos M, Stamenkovic I. Matrix metalloproteinase-7-mediated cleavage of Fas ligand protects tumor cells from chemotherapeutic drug cytotoxicity. Cancer Res. 2001;61(2):577–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li X, Yang Y, Hu Y, Dang D, Regezi J, Schmidt BL, Atakilit A, Chen B, Ellis D, Ramos DM. Alphavbeta6-Fyn signaling promotes oral cancer progression. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(43):41646–41653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306274200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ahmed N, Pansino F, Clyde R, Murthi P, Quinn MA, Rice GE, Agrez MV, Mok S, Baker MS. Overexpression of alpha(v)beta6 integrin in serous epithelial ovarian cancer regulates extracellular matrix degradation via the plasminogen activation cascade. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23(2):237–244. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thomas GJ, Lewis MP, Hart IR, Marshall JF, Speight PM. AlphaVbeta6 integrin promotes invasion of squamous carcinoma cells through up-regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-9. Int J Cancer. 2001;92(5):641–650. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20010601)92:5<641::aid-ijc1243>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gu X, Niu J, Dorahy DJ, Scott R, Agrez MV. Integrin alpha(v)beta6-associated ERK2 mediates MMP-9 secretion in colon cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2002;87(3):348–351. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baum O, Hlushchuk R, Forster A, Greiner R, Clezardin P, Zhao Y, Djonov V, Gruber G. Increased invasive potential and up-regulation of MMP-2 in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells expressing the beta3 integrin subunit. Int J Oncol. 2007;30(2):325–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ravanti L, Heino J, Lopez-Otin C, Kahari VM. Induction of collagenase-3 (MMP-13) expression in human skin fibroblasts by three-dimensional collagen is mediated by p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(4):2446–2455. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hauck CR, Hsia DA, Puente XS, Cheresh DA, Schlaepfer DD. FRNK blocks v-Src-stimulated invasion and experimental metastases without effects on cell motility or growth. EMBO J. 2002;21(23):6289–6302. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Iyer V, Pumiglia K, DiPersio CM. Alpha3beta1 integrin regulates MMP-9 mRNA stability in immortalized keratinocytes: a novel mechanism of integrin-mediated MMP gene expression. J Cell Sci. 2005;118(Pt 6):1185–1195. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lamar JM, Iyer V, DiPersio CM. Integrin alpha3beta1 potentiates TGFbeta-mediated induction of MMP-9 in immortalized keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128(3):575–586. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seiki M. Membrane-type matrix metalloproteinases. APMIS. 1999;107(1):137–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1999.tb01536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seiki M. Membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase: a key enzyme for tumor invasion. Cancer Lett. 2003;194(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00699-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Itoh Y, Seiki M. MT1-MMP: a potent modifier of pericellular microenvironment. J Cell Physiol. 2006;206(1):1–8. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang GY, Xu KS, Pan ZQ, Zhang ZY, Mi YT, Wang JS, Chen R, Niu J. Integrin alpha v beta 6 mediates the potential for colon cancer cells to colonize in and metastasize to the liver. Cancer Sci. 2008;99(5):879–887. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00762.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morini M, Mottolese M, Ferrari N, Ghiorzo F, Buglioni S, Mortarini R, Noonan DM, Natali PG, Albini A. The alpha 3 beta 1 integrin is associated with mammary carcinoma cell metastasis, invasion, and gelatinase B (MMP-9) activity. Int J Cancer. 2000;87(3):336–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guo H, Li R, Zucker S, Toole BP. EMMPRIN (CD147), an inducer of matrix metalloproteinase synthesis, also binds interstitial collagenase to the tumor cell surface. Cancer Res. 2000;60(4):888–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bourguignon LY, Gunja-Smith Z, Iida N, Zhu HB, Young LJ, Muller WJ, Cardiff RD. CD44v(3,8-10) is involved in cytoskeleton-mediated tumor cell migration and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP-9) association in metastatic breast cancer cells. J Cell Physiol. 1998;176(1):206–215. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199807)176:1<206::AID-JCP22>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ayala I, Baldassarre M, Caldieri G, Buccione R. Invadopodia: a guided tour. Eur J Cell Biol. 2006;85(3–4):159–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nakahara H, Howard L, Thompson EW, Sato H, Seiki M, Yeh Y, Chen WT. Transmembrane/cytoplasmic domain-mediated membrane type 1-matrix metalloprotease docking to invadopodia is required for cell invasion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(15):7959–7964. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.7959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Friedl P, Wolf K. Tube travel: the role of proteases in individual and collective cancer cell invasion. Cancer Res. 2008;68(18):7247–7249. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Deryugina EI, Ratnikov B, Monosov E, Postnova TI, DiScipio R, Smith JW, Strongin AY. MT1-MMP initiates activation of pro-MMP-2 and integrin alphavbeta3 promotes maturation of MMP-2 in breast carcinoma cells. Exp Cell Res. 2001;263(2):209–223. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Strongin AY, Collier I, Bannikov G, Marmer BL, Grant GA, Goldberg GI. Mechanism of cell surface activation of 72-kDa type IV collagenase. Isolation of the activated form of the membrane metalloprotease. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(10):5331–5338. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.10.5331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Morrison CJ, Butler GS, Bigg HF, Roberts CR, Soloway PD, Overall CM. Cellular activation of MMP-2 (gelatinase A) by MT2-MMP occurs via a TIMP-2-independent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(50):47402–47410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108643200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang Y, Dang D, Atakilit A, Schmidt B, Regezi J, Li X, Eisele D, Ellis D, Ramos DM. Specific alpha v integrin receptors modulate K1735 murine melanoma cell behavior. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;308(4):814–819. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01477-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baumann F, Leukel P, Doerfelt A, Beier CP, Dettmer K, Oefner PJ, Kastenberger M, Kreutz M, Nickl-Jockschat T, Bogdahn U, Bosserhoff AK, Hau P. Lactate promotes glioma migration by TGF-beta2-dependent regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-2. Neuro Oncol. 2009;11(4):368–380. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chetty C, Lakka SS, Bhoopathi P, Rao JS. MMP-2 alters VEGF expression via alphaVbeta3 integrin-mediated PI3K/AKT signaling in A549 lung cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(5):1081–1095. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Deryugina EI, Bourdon MA, Jungwirth K, Smith JW, Strongin AY. Functional activation of integrin alpha V beta 3 in tumor cells expressing membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase. Int J Cancer. 2000;86(1):15–23. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000401)86:1<15::aid-ijc3>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gladson CL, Cheresh DA. Glioblastoma expression of vitronectin and the alpha v beta 3 integrin. Adhesion mechanism for transformed glial cells. J Clin Invest. 1991;88(6):1924–1932. doi: 10.1172/JCI115516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Albelda SM, Mette SA, Elder DE, Stewart R, Damjanovich L, Herlyn M, Buck CA. Integrin distribution in malignant melanoma: association of the beta 3 subunit with tumor progression. Cancer Res. 1990;50(20):6757–6764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guo W, Giancotti FG. Integrin signalling during tumour progression. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5(10):816–826. doi: 10.1038/nrm1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Silletti S, Kessler T, Goldberg J, Boger DL, Cheresh DA. Disruption of matrix metalloproteinase 2 binding to integrin alpha vbeta 3 by an organic molecule inhibits angiogenesis and tumor growth in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(1):119–124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011343298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xu J, Rodriguez D, Petitclerc E, Kim JJ, Hangai M, Moon YS, Davis GE, Brooks PC. Proteolytic exposure of a cryptic site within collagen type IV is required for angiogenesis and tumor growth in vivo. J Cell Biol. 2001;154(5):1069–1079. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200103111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Celiker MY, Wang M, Atsidaftos E, Liu X, Liu YE, Jiang Y, Valderrama E, Goldberg ID, Shi YE. Inhibition of Wilms’ tumor growth by intramuscular administration of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-4 plasmid DNA. Oncogene. 2001;20(32):4337–4343. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brand K, Baker AH, Perez-Canto A, Possling A, Sacharjat M, Geheeb M, Arnold W. Treatment of colorectal liver metastases by adenoviral transfer of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2 into the liver tissue. Cancer Res. 2000;60(20):5723–5730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Deryugina EI, Quigley JP. Matrix metalloproteinases and tumor metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;25(1):9–34. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-7886-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jumper C, Cobos E, Lox C. Determination of the serum matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) in patients with either advanced small-cell lung cancer or non-small-cell lung cancer prior to treatment. Respir Med. 2004;98(2):173–177. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2003.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brooks PC, Silletti S, Schalscha TL, Friedlander M, Cheresh DA. Disruption of angiogenesis by PEX, a noncatalytic metalloproteinase fragment with integrin binding activity. Cell. 1998;92(3):391–400. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80931-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mondino A, Blasi F. uPA and uPAR in fibrinolysis, immunity and pathology. Trends Immunol. 2004;25(8):450–455. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rosso M, Margheri F, Serrati S, Chilla A, Laurenzana A, Fibbi G. The urokinase receptor system, a key regulator at the intersection between inflammation, immunity, and coagulation. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17(19):1924–1943. doi: 10.2174/138161211796718189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Blasi F, Sidenius N. The urokinase receptor: focused cell surface proteolysis, cell adhesion and signaling. FEBS Lett. 2010;584(9):1923–1930. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sidenius N, Blasi F. The urokinase plasminogen activator system in cancer: recent advances and implication for prognosis and therapy. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2003;22(2–3):205–222. doi: 10.1023/a:1023099415940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dass K, Ahmad A, Azmi AS, Sarkar SH, Sarkar FH. Evolving role of uPA/uPAR system in human cancers. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34(2):122–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mazar AP. Urokinase plasminogen activator receptor choreographs multiple ligand interactions: implications for tumor progression and therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(18):5649–5655. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Smith HW, Marshall CJ. Regulation of cell signalling by uPAR. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(1):23–36. doi: 10.1038/nrm2821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tang CH, Wei Y. The urokinase receptor and integrins in cancer progression. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65(12):1916–1932. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7573-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Testa JE, Quigley JP. The role of urokinase-type plasminogen activator in aggressive tumor cell behavior. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1990;9(4):353–367. doi: 10.1007/BF00049524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ellis V, Behrendt N, Dano K. Plasminogen activation by receptor-bound urokinase. A kinetic study with both cell-associated and isolated receptor. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(19):12752–12758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rabbani SA, Mazar AP. The role of the plasminogen activation system in angiogenesis and metastasis. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2001;10(2):393–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ellis V, Pyke C, Eriksen J, Solberg H, Dano K. The urokinase receptor: involvement in cell surface proteolysis and cancer invasion. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;667:13–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb51591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Duffy MJ. The urokinase plasminogen activator system: role in malignancy. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10(1):39–49. doi: 10.2174/1381612043453559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Choong PF, Nadesapillai AP (2003) Urokinase plasminogen activator system: a multifunctional role in tumor progression and metastasis. Clin Orthop Relat Res (415 Suppl):S46–58 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 94.Chapman HA. Plasminogen activators, integrins, and the coordinated regulation of cell adhesion and migration. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9(5):714–724. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mi Z, Guo H, Wai PY, Gao C, Kuo PC. Integrin-linked kinase regulates osteopontin-dependent MMP-2 and uPA expression to convey metastatic function in murine mammary epithelial cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(6):1134–1145. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ghosh S, Johnson JJ, Sen R, Mukhopadhyay S, Liu Y, Zhang F, Wei Y, Chapman HA, Stack MS. Functional relevance of urinary-type plasminogen activator receptor-alpha3beta1 integrin association in proteinase regulatory pathways. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(19):13021–13029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508526200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bianchi E, Ferrero E, Fazioli F, Mangili F, Wang J, Bender JR, Blasi F, Pardi R. Integrin-dependent induction of functional urokinase receptors in primary T lymphocytes. J Clin Invest. 1996;98(5):1133–1141. doi: 10.1172/JCI118896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Estreicher A, Muhlhauser J, Carpentier JL, Orci L, Vassalli JD. The receptor for urokinase type plasminogen activator polarizes expression of the protease to the leading edge of migrating monocytes and promotes degradation of enzyme inhibitor complexes. J Cell Biol. 1990;111(2):783–792. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.2.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mueller SC, Ghersi G, Akiyama SK, Sang QX, Howard L, Pineiro-Sanchez M, Nakahara H, Yeh Y, Chen WT. A novel protease-docking function of integrin at invadopodia. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(35):24947–24952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.35.24947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wei Y, Eble JA, Wang Z, Kreidberg JA, Chapman HA. Urokinase receptors promote beta1 integrin function through interactions with integrin alpha3beta1. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12(10):2975–2986. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.10.2975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bohuslav J, Horejsi V, Hansmann C, Stockl J, Weidle UH, Majdic O, Bartke I, Knapp W, Stockinger H. Urokinase plasminogen activator receptor, beta 2-integrins, and Src-kinases within a single receptor complex of human monocytes. J Exp Med. 1995;181(4):1381–1390. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.4.1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Simon DI, Wei Y, Zhang L, Rao NK, Xu H, Chen Z, Liu Q, Rosenberg S, Chapman HA. Identification of a urokinase receptor-integrin interaction site. Promiscuous regulator of integrin function. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(14):10228–10234. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.10228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Carriero MV, Vecchio S, Capozzoli M, Franco P, Fontana L, Zannetti A, Botti G, D’Aiuto G, Salvatore M, Stoppelli MP. Urokinase receptor interacts with alpha(v)beta5 vitronectin receptor, promoting urokinase-dependent cell migration in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1999;59(20):5307–5314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Thomas S, Chiriva-Internati M, Shah GV. Calcitonin receptor-stimulated migration of prostate cancer cells is mediated by urokinase receptor-integrin signaling. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2007;24(5):363–377. doi: 10.1007/s10585-007-9073-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chapman HA, Wei Y. Protease crosstalk with integrins: the urokinase receptor paradigm. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86(1):124–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Khatib AM, Nip J, Fallavollita L, Lehmann M, Jensen G, Brodt P. Regulation of urokinase plasminogen activator/plasmin-mediated invasion of melanoma cells by the integrin vitronectin receptor alphaVbeta3. Int J Cancer. 2001;91(3):300–308. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(200002)9999:9999<::aid-ijc1055>3.3.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.May AE, Kanse SM, Lund LR, Gisler RH, Imhof BA, Preissner KT. Urokinase receptor (CD87) regulates leukocyte recruitment via beta 2 integrins in vivo. J Exp Med. 1998;188(6):1029–1037. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.6.1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Smith HW, Marra P, Marshall CJ. uPAR promotes formation of the p130Cas-Crk complex to activate Rac through DOCK180. J Cell Biol. 2008;182(4):777–790. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wei C, Moller CC, Altintas MM, Li J, Schwarz K, Zacchigna S, Xie L, Henger A, Schmid H, Rastaldi MP, Cowan P, Kretzler M, Parrilla R, Bendayan M, Gupta V, Nikolic B, Kalluri R, Carmeliet P, Mundel P, Reiser J. Modification of kidney barrier function by the urokinase receptor. Nat Med. 2008;14(1):55–63. doi: 10.1038/nm1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tang CH, Hill ML, Brumwell AN, Chapman HA, Wei Y. Signaling through urokinase and urokinase receptor in lung cancer cells requires interactions with beta1 integrins. J Cell Sci. 2008;121(Pt 22):3747–3756. doi: 10.1242/jcs.029769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Aguirre-Ghiso JA, Liu D, Mignatti A, Kovalski K, Ossowski L. Urokinase receptor and fibronectin regulate the ERK(MAPK) to p38(MAPK) activity ratios that determine carcinoma cell proliferation or dormancy in vivo. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12(4):863–879. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.4.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Aguirre Ghiso JA, Kovalski K, Ossowski L. Tumor dormancy induced by downregulation of urokinase receptor in human carcinoma involves integrin and MAPK signaling. J Cell Biol. 1999;147(1):89–104. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.1.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Coussens LM, Fingleton B, Matrisian LM. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors and cancer: trials and tribulations. Science. 2002;295(5564):2387–2392. doi: 10.1126/science.1067100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Mazar AP. The urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) as a target for the diagnosis and therapy of cancer. Anticancer Drugs. 2001;12(5):387–400. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200106000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]