Abstract

Purpose

Multimodal thromboprophylaxis includes preoperative thromboembolic risk stratification and autologous blood donation, surgery performed under regional anaesthesia, postoperative rapid mobilisation, use of pneumatic compression devices and chemoprophylaxis tailored to the patient’s individual risk. We determined the 90-day rate of venous thromboembolism (VTE), other complications and mortality in patients who underwent primary elective hip and knee replacement surgery with multimodal thromboprophylaxis.

Methods

A total of 1,568 consecutive patients undergoing hip and knee replacement surgery received multimodal thromboprophylaxis: 1,115 received aspirin, 426 received warfarin and 27 patients received low molecular weight heparin and warfarin with or without a vena cava filter.

Results

The rate of VTE, pulmonary embolism, proximal deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and distal DVT was 1.2, 0.36, 0.45 and 0.36 %, respectively, in patients who received aspirin. The rates in those who received warfarin were 1.4, 0.9, 0.47 and 0.47 %, respectively. The overall 90-day mortality rate was 0.2 %.

Conclusions

Multimodal thromboprophylaxis in which aspirin is administered to low-risk patients is safe and effective following primary total joint replacement.

Introduction

The rates of venous thromboembolism (VTE) following total joint replacement (TJR) have diminished over the last three decades [1]. However, routine thromboprophylaxis is mandated by regulatory bodies [2, 3]. The Center for Medicare Services has implemented pay for performance measures that restrict reimbursement to physicians and hospitals in the event that a patient develops hospital-acquired conditions including VTE [4]. The guidelines by the American Association of Chest Physicians (ACCP) [2] strongly recommend the routine use of potent anticoagulants (Grade 1B—moderate-quality evidence), while aspirin received a weak recommendation (Grade 2C—low- or very low-quality evidence). The preferential use of potent anticoagulation has been widely reinforced despite the concern of associated bleeding voiced by leaders of the orthopaedic community [1, 5, 6].

Multimodal thromboprophylaxis for patients undergoing hip arthroplasty has been perfected at our institution by Dr. Eduardo Salvati, Dr. Nigel Sharrock and coworkers over the last four decades and is supported by a large body of basic and clinical research [7–11]. The protocol aims at reducing the patient’s unnecessary exposure to potent anticoagulants and their associated risks. Multimodal thromboprophylaxis encompasses [7–11]: preoperative VTE risk stratification; discontinuation of procoagulant medications and autologous blood donation [12]; surgery performed under regional hypotensive anaesthesia; intravenous administration of heparin during surgery and before femoral preparation [in total hip arthroplasty (THA) recipients]; aspiration of intramedullary contents; pneumatic compression; knee-high elastic stockings; and early mobilisation and chemoprophylaxis for four to six weeks. The preferred postoperative adjuvant chemoprophylaxis in patients with a low VTE risk is aspirin. Warfarin is reserved for patients at a high VTE risk, those on warfarin for medical reasons preoperatively and patients with a contraindication to the use of aspirin [13].

The purpose of this study was to determine the rates and characteristics of VTE events, bleeding and wound complications, readmissions and mortality in patients who underwent primary elective hip and knee replacement surgery with multimodal thromboprophylaxis.

Patients and methods

We retrospectively reviewed 1,568 consecutive patients who underwent primary elective hip or knee arthroplasty by the senior author (AGDV) between January 2005 and October 2011 (Table 1). Some of the results of a selected cohort of 539 patients have been recently reported [14]. All patients were stratified for the VTE risk; they discontinued procoagulant medications and predonated autologous blood if not medically contraindicated.

Table 1.

Preoperative characteristics of patients

| Characteristic/variable | THA | TKA | UKA | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 887 | 645 | 36 | 1,568 |

| Age | 63 ± 13 (17–93) | 66 ± 10 (42–91) | 61 ± 10 (44–84) | 65 ± 12 (17–93) |

| Male gender | 342 (38.6 %) | 212 (30.3 %) | 15 (37.5 %) | 569 (36.3 %) |

| Height (m) | 1.66 ± 0.10 | 1.64 ± 0.11 | 1.65 ± 0.11 | 1.65 ± 0.10 |

| (1.33–2.06) | (1.12–1.93) | (1.47–1.95) | (1.12–2.06) | |

| Weight (kg) | 81 ± 20 (36–152) | 85 ± 19 (45–160) | 81 ± 16 (52–123) | 83 ± 20 (36–160) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29 ± 6.4 (15–58) | 32 ± 6.5 (18–64) | 30 ± 4.6 (18–39) | 30 ± 6.8 (15–64) |

| Diagnoses | ||||

| Osteoarthritis | 776 (87 %) | 559 (87 %) | 33 (92 %) | 1368 (87.2 %) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 4 (0.5 %) | 16 (2.5 %) | 0 | 20 (1.3 %) |

| Post-traumatic arthritis | 20 (2.3 %) | 17 (2.6 %) | 0 | 37 (2.4 %) |

| DDH | 20 (2.3 %) | NA | NA | 20 (2.3 %) |

| Avascular necrosis | 51 (5.7 %) | 6 (0.9 %) | 3 (8 %) | 60 (3.8 %) |

| Other | 16 (1.8 %) | 7 (1.1 %) | 0 | 23 (1.5 %) |

| History of VTE | ||||

| History of VTE | 46 (5.2 %) | 24 (3.7 %) | 0 | 70 (4.5 %) |

| History of PE | 9 (1 %) | 8 (1.2 %) | 0 | 17 (1.1 %) |

| History of DVT | 43 (4.8 %) | 20 (3.2 %) | 0 | 63 (4 %) |

| Bilateral single-stage procedure | 42 (4.7 %) | 55 (8.5 %) | 2 (5.6 %) | 99 (6.3 %) |

Mean ± SD (range) and n (%) are presented for continuous and discrete outcomes, respectively

THA total hip arthroplasty, TKA total knee arthroplasty, UKA unicompartmental knee arthroplasty, BMI body mass index, DDH developmental dysplasia of the hip, NA not applicable, VTE venous thromboembolism, PE pulmonary embolism, DVT deep vein thrombosis

Operations were performed under epidural anaesthesia (99 %), unless medically contraindicated. The surgical team followed a standardised protocol:

THA was performed through a posterolateral approach. Uncemented acetabular fixation was used in all but two patients. Patients received one bolus of unfractionated intravenous heparin (10–15 U/kg), one to two minutes before femoral canal preparation [10]. Cemented femoral fixation was used in the majority of patients (83 %).

Total and unicompartmental knee arthroplasties (TKA, UKA) were performed under tourniquet control and using a midline incision with a medial parapatellar arthrotomy. All implants were cemented.

Closed suction drainage was used in all patients. Intermittent pneumatic compression was implemented as soon as patients arrived to the recovery room. Furthermore, patients were encouraged to perform immediate active ankle flexion and extension exercises, and were mobilised on postoperative day one.

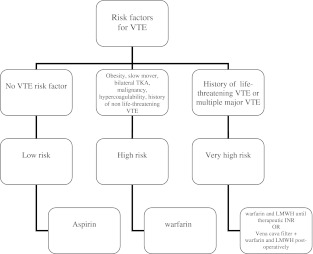

Patients received chemoprophylaxis for six weeks after surgery based on VTE risk stratification [9] (Fig. 1). Patients at a high risk of VTE included those with a history of obesity, malignancy, VTE, active or recent cancer, known hypercoagulable disorder, debilitated patients who were expected to mobilise slowly after surgery and those undergoing bilateral TKA [15] (Tables 2 and 3). Patients with a history of non-life-threatening VTE [proximal deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE)] were considered at very high risk and were treated with warfarin and low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) until the international normalised ratio (INR) was therapeutic. In addition, patients who were in Coumadin for medical reasons before surgery, received Coumadin after surgery regardless of their thromboembolic risk. Patients with a recent history of a life-threatening PE (within 12 months), multiple PE or multiple proximal DVT were treated with a vena cava filter (VCF) inserted preoperatively [1] and received warfarin and LMWH postoperatively (Table 2). Specifically, seven patients had had a permanent VCF at the time of their initial consultation, and three patients had a temporary VCF inserted on the day of surgery by a specialised interventional radiologist. Temporary VCF were removed three months after surgery.

Fig. 1.

Tree diagram illustrating VTE risk stratification process for the recommendation of chemoprophylaxis (all patients receive multimodal thromboprophylaxis)

Table 2.

Number of patients undergoing total joint replacement, stratified per VTE risk

| Procedure | Low risk | High risk | Very high risk | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| THA | 705 (79.5 %) | 172 (19.4 %) | 10 (1.1 %) | 887 |

| TKA | 418 (64.8 %) | 210 (32.6 %) | 17 (2.6 %) | 645 |

| UKA | 29 (80.6 %) | 7 (19.4 %) | 0 | 36 |

| Total | 1,152 | 389 | 27 | 1,568 |

THA total hip arthroplasty, TKA total knee arthroplasty, UKA unicompartmental knee arthroplasty

Table 3.

Indications for warfarin chemoprophylaxis (n = 1,568)

| Chemoprophylaxis | THA | TKA | UKA | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | 697 (79 %) | 389 (60.3 %) | 29 (80 %) | 1,115 (71.1 %) |

| Warfarin | 180 (20 %) | 239 (37 %) | 7 (20 %) | 426 (27.1 %) |

| Enoxaparin to warfarin | 6 (0.7 %) | 11 (1.7 %) | 0 | 17 (1 %) |

| VCF | 4 (0.5 %) | 6 (0.9 %) | 0 | 10 (0.6 %) |

| Indication for warfarin chemoprophylaxis | ||||

| Obesity | 44 (5 %) | 76 (11.8 %) | 0 | 120 (7.7 %) |

| Bilateral procedure | 2 (0.2 %) | 54 (8.4 %) | 3 (8.3 %)a | 59 (3.8 %) |

| Preexisting cardiac/CNS disorders | 18 (2 %) | 25 (3.9 %) | 2 (5.5 %) | 45 (2.9 %) |

| History of VTE or hypercoagulable disorder | 37 (4.2 %) | 25 (3.9 %) | 0 | 62 (4 %) |

| Aspirin allergy or intolerance | 12 (1.4 %) | 25 (3.9 %) | 0 | 37 (2.4 %) |

| Recent or current malignancy | 13 (1.5 %) | 11 (1.7 %) | 1 (2.8 %) | 25 (1.6 %) |

| Slow mobilisation | 47 (5.5 %) | 18 (2.8 %) | 0 | 65 (4.1 %) |

| Multifactorial | 6 (0.7 %) | 5 (0.8 %) | 1 (2.8 %) | 12 (0.8 %) |

| Patient request | 1 (0.1 %) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.06 %) |

THA total hip arthroplasty, TKA total knee arthroplasty, UKA unicompartmental knee arthroplasty, n number of patients, % percentage of patients, VCF vena cava filter, VTE venous thromboembolism

aA patient had a bilateral knee replacement consisting of a TKA and a contralateral UKA

For those patients receiving chemoprophylaxis with warfarin, a dose of 5 mg was started the night of surgery. Daily blood samples were analysed for INR values, and a standardised warfarin-dosing table [16] was used with a goal of maintaining an INR of 2. In selected patients, LMWH enoxaparin was administered at a dose of 40 mg subcutaneously once daily starting the night of surgery. Low-risk patients received aspirin starting on the night of surgery (325 mg orally twice a day). None of the patients included in this study had a high risk for bleeding; otherwise we would have contemplated the wisdom of no pharmacological thromboprophylaxis [2].

During the hospital stay, patients were examined daily. Wound drainage was defined as a complication if it delayed discharge. Thromboses were classified as proximal (pelvic, femoral, popliteal) or distal (calf). Symptomatic PEs were evaluated with ventilation-perfusion scans or computed tomography (CT), based on availability. At discharge, DVT screening was not routinely performed [2]. All patients were contacted and seen personally postoperatively by the authors, and their hospital and office records were reviewed 90 days after surgery. No patient was lost to follow-up.

Data are presented as mean (± standard deviation) and range for continuous outcomes. Frequency and percentage were calculated for discrete outcomes. Differences in the rates of VTE between patients who underwent THA, TKA and UKA were compared using Fisher’s exact test for low incidences.

Results

Ninety-day complications

A total of 121 patients (7.7 %) developed complications during the follow-up period. Of them, 35 had undergone a THA (3.9 %) and 86 a TKA (13.3 %) (Tables 4 and 5).

Table 4.

Number of patients who developed 90-day complications

| Complication | THA | TKA | UKA | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VTE | 8 (0.9 %) | 11 (1.7 %) | 0 | 19 (1.2 %) |

| Tachycardia/arrhythmia | 4 (0.5 %) | 13 (2 %) | 0 | 17 (1.1 %) |

| Myocardial infarction/angina | 0 | 4 (0.6 %) | 0 | 4 (0.3 %) |

| CHF | 1 (0.1 %) | 2 (0.3 %) | 0 | 3 (0.2 %) |

| Endocarditis | 0 | 1 (0.2 %) | 0 | 1 (0.06 %) |

| Major organ/system bleeding | 5 (0.6 %) | 1 (0.2 %)a | 0 | 6 (0.4 %) |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 0 | 1 (0.2 %) | 0 | 1 (0.06 %) |

| Wound drainage requiring observation | 2 (0.2 %) | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.1 %) |

| Wound drainage requiring I&D | 3 (0.3 %) | 0 | 0 | 3 (0.2 %) |

| SWI | 6 (0.7) | 8 (1.2 %) | 0 | 14 (0.9 %) |

| DWI | 0 | 1 (0.2 %) | 0 | 1 (0.06 %) |

| Hypoxia/atelectasis | 1 (0.1 %) | 3 (0.5 %) | 0 | 4 (0.3 %) |

| Pneumonia | 1 (0.1 %) | 5 (0.8 %) | 0 | 6 (0.4 %) |

| Minor bleeding | 0 | 4 (0.6 %) | 0 | 4 (0.3 %) |

| Ileus | 3 (0.3 %) | 1 (0.2 %) | 0 | 4 (0.3 %) |

| Reoperations | 1 (0.1 %) | 1 (0.2 %) | 0 | 2 (0.1 %) |

| Periprosthetic fracture | 0 | 1 (0.2 %) | 0 | 1 (0.06 %) |

| Manipulations | NA | 29 (4.5 %) | 0 | 29 (4.3 %) |

| Total | 35 (3.9 %) | 86 (13.3 %) | 0 | 121 (7.7 %) |

THA total hip arthroplasty, TKA total knee arthroplasty, UKA unicompartmental knee arthroplasty, VTE venous thromboembolism, % percentage of patients, CHF congestive heart failure, INR international normalised ratio, I&D irrigation and debridement, SWI superficial wound infection, DWI deep wound infection, NA not applicable

aPatient who underwent bilateral TKA

Table 5.

Number of patients who developed 90-day complications, stratified by VTE risk

| Complication | Low risk | High risk | Very high risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| VTE | 13 (1.1 %) | 6 (1.5 %) | 0 |

| Tachycardia/arrhythmia | 4 (0.3 %) | 12 (3.1 %) | 1 (3.7 %) |

| Myocardial infarction/angina | 2 (0.2 %) | 2 (0.5 %) | 0 |

| CHF | 2 (0.2 %) | 1 (0.3 %) | 0 |

| Endocarditis | 1 (0.1 %) | 0 | 0 |

| Major organ/system bleeding | 3 (0.3 %) | 3 (0.8 %)a | 0 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 1 (0.1 %) | 0 | 0 |

| Wound drainage requiring observation | 0 | 2 (0.5 %) | 0 |

| Wound drainage requiring I&D | 1 (0.1 %) | 2 (0.5 %) | 0 |

| SWI | 3 (0.3 %) | 11 (2.8 %) | 0 |

| DWI | 0 | 1 (0.3 %) | 0 |

| Hypoxia/atelectasis | 2 (0.2 %) | 1 (0.3 %) | 1 (3.7 %) |

| Pneumonia | 3 (0.3 %) | 2 (0.5 %) | 1 (3.7 %) |

| Minor bleeding | 0 | 4 (1 %) | 0 |

| Ileus | 3 (0.3 %) | 1 (0.3 %) | 0 |

| Reoperations | 1 (0.1 %) | 1 (0.3 %) | 0 |

| Periprosthetic fracture | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.7 %) |

| Manipulations | 16 (3.8 %) | 13 (6.2 %) | 0 |

| Total | 55 (4.8 %) | 62 (15.9 %) | 4 (14.8 %) |

VTE venous thromboembolism, % percentage of patients, CHF congestive heart failure, INR international normalised ratio, I&D irrigation and debridement, SWI superficial wound infection, DWI deep wound infection, TKA total knee arthroplasty

aOne patient underwent bilateral TKA

Thromboembolism rates and location

The rate of VTE was low (Table 6). PE was diagnosed using helical CT in five patients (62.5 %) and ventilation/perfusion scan in three patients (37.5 %). One patient developed bilateral PE: central, segmental and subsegmental on one side, and subsegmental on the contralateral side. Two patients suffered central PE, four had segmental PE and one a subsegmental PE. Two of eight PE patients (25 %) required readmission due to haemodynamic instability. One of these patients, receiving aspirin after a THA, suffered bilateral PEs on postoperative day 11. The other patient, who received warfarin after TKA, developed a central PE on postoperative day 90. None of the eight patients died. The diagnosis of DVT was made with Doppler ultrasonography in six of seven patients with a proximal thrombosis and in all six patients with distal DVT. The remaining patient had a proximal DVT diagnosed with helical CT while evaluating for the presence of a PE. Among seven proximal DVTs, none were intrapelvic, one was located in the femoral vein (14 %) and six in the popliteal vein (86 %). Six proximal DVTs were located on the same side of the operation, and one was located in the contralateral limb. Two (33 %) of the six distal DVTs were bilateral, and four were ipsilateral (67 %).

Table 6.

Number of patients with thromboembolism or mortality. Incidence is given between parentheses

| Group | n | VTE | Distal DVT | Proximal DVT | PE | Mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| THA | 887 | 8 (0.9 %)a | 1 (0.1 %) | 4 (0.5 %) | 4 (0.5 %) | 1 (0.1 %) |

| TKA | 645 | 11 (1.7 %)b | 5 (0.8 %) | 3 (0.5 %) | 4 (0.6 %) | 2 (0.3 %) |

| UKA | 36 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 1,568 | 19 (1.2 %) | 6 (0.4) | 7 (0.4 %) | 8 (0.5 %) | 3 (0.2 %) |

VTE venous thromboembolism, DVT deep vein thrombosis, PE pulmonary embolism, THA total hip arthroplasty, TKA total knee arthroplasty, UKA unicompartmental knee arthroplasty, n number of patients

aOne THA patient developed a PE and a proximal DVT

bOne TKA patient developed a proximal and a distal DVT

Chemoprophylaxis and timing of VTE

The rate of VTE, PE, proximal DVT and distal DVT in patients who received aspirin was 1.2, 0.36, 0.45 and 0.36 %, respectively. The rates in those who received warfarin were 1.4, 0.9, 0.47 and 0.47 %, respectively. No VTE was observed in the 17 patients who received LMWH and warfarin, and in patients who had a VCF inserted preoperatively. Given that no patient included in the study was at high risk of bleeding, all patients received chemoprophylaxis.

The diagnosis of VTE was made during the first week after surgery in seven of 19 patients (37 %). Of the five VTE events diagnosed within the first three postoperative days, there were two PEs in high-risk patients receiving warfarin, and two PEs and one proximal DVT in low-risk patients receiving aspirin.

Thromboembolism and type of joint replacement

The overall rate of VTE in patients who underwent THA, TKA and UKA was 0.9, 1.7 and 0 %, respectively (p = 0.36). There were 16 patients who suffered VTE following unilateral joint replacement (1.1 %) and three who developed VTE following bilateral joint replacements (3 %) (p = 0.11).

Bleeding complications

Ten patients (0.6 %) who underwent five THAs, four unilateral TKAs and a bilateral TKA developed bleeding complications during the first 90 days.

Minor bleeding was detected in four patients, all of whom had undergone unilateral TKA and had received warfarin: two developed a thigh haematoma, one haemorrhoid bleeding and one nose bleeding. All resolved with medical management.

Major bleeding was detected in five patients, all of whom had undergone unilateral THA surgery: three patients developed local bleeding and three patients organ bleeding. Among the three patients with local bleeding, two (one on warfarin and one on aspirin) developed a wound haematoma requiring irrigation and debridement (I&D). The remaining patient received aspirin and clopidogrel postoperatively due to a history of coronary artery disease. She developed a large, spontaneous intrapelvic bleed two weeks after surgery that resolved with medical management. Finally, among the two patients who developed major organ bleeding, one who had received aspirin developed a bleeding gastric ulcer two days after surgery that resolved with medical management. The other patient, who had received warfarin, developed spontaneous haematuria associated with an INR of 6.5. She required readmission, administration of vitamin K and transfusion of fresh frozen plasma. One patient who had undergone a bilateral TKA, and received warfarin chemoprophylaxis, developed thrombocytopaenia.

The rate of bleeding, minor bleeding and major bleeding was 0.3, 0 and 0.3 %, respectively, for patients who received aspirin, and 1.6, 0.9 and 0.7 %, respectively, for patients who received warfarin. There were no bleeding events in the 27 patients who received LMWH and Coumadin or a VCF. No complication was observed with the removal of the VCF.

Wound-related complications

A total of 20 patients (1.3 %) developed wound complications: 14 (0.9 %) developed a superficial wound infection (SWI), one (0.06 %) a deep wound infection (DWI) and 5 (0.3 %) experienced persistent wound drainage.

Among 14 patients with a SWI (six THAs and eight TKAs), 11 were on warfarin and three on aspirin. Ten of these patients had an infection that resolved with oral antibiotics. The remaining four patients (one TKA and three THAs) were readmitted for severe cellulitis and were treated with intravenous antibiotics; and one required irrigation and drainage. All four patients were on warfarin chemoprophylaxis.

Persistent wound drainage was observed in five patients, all of which had had a THA. Three of these patients, two on warfarin and one on aspirin, required irrigation and drainage.

One patient (0.06 %), who had undergone bilateral TKA and received warfarin chemoprophylaxis, developed a right-sided DWI about six weeks after the procedure. The patient therefore underwent successful two-stage revision arthroplasty with an antibiotic spacer and subsequent reimplantation.

The rate of wound-related complications, SWI, DWI and wound drainage was 0.45, 0.27, 0 and 0.18 %, respectively, for patients who received aspirin, and 3.5, 2.6, 0.2 and 0.7 %, respectively, for patients who received warfarin.

Mortality

Three patients died during the follow-up period (mortality rate: 0.2 %) (Table 6). A 59-year-old woman with a body mass index (BMI) of 50 and history of hypertension died three months after staged bilateral TKAs performed two months apart. The patient was in the medical field and requested aspirin postoperatively. No autopsy was performed. A 78-year-old man with a BMI of 33 and a medical history of type 2 diabetes mellitus with severe vascular compromise, right bundle branch block and history of tobacco use underwent primary THA and received aspirin. The patient died 29 days after the procedure due to congestive heart failure. A 58-year-old man with a medical history of sleep apnoea and who was given aspirin after unilateral TKA died six weeks after surgery. An autopsy was performed and death was attributed to coronary artery disease.

Discussion

We have reported low rates of VTE, bleeding and mortality using multimodal prophylaxis following primary THA [13]. However, there is limited information regarding safety and efficacy of multimodal prophylaxis when used in all patients who receive an arthroplasty of the lower extremity. This information is important as TKA patients may be at an increased risk of VTE compared with their THA counterparts [17].

Our study has limitations. Firstly, it does not have a control group. Given the low incidence of VTE with multimodal prophylaxis, a comparative study aimed at detecting a significant difference in the already low VTE rate would require an extremely large number of patients. With our current low rate of VTE, a study aimed at detecting a reduction of total VTE by 20 % (from 1.2 to 0.96 %) with 80 % power would require 29,942 patients in each arm. If the study were conceived to detect a reduction in the incidence of PE by 20 % (from 0.5 to 0.4 %) with 80 % power, the number of patients in each arm would be 72,307. With the large number of patients required, such hypothetical studies may not be feasible. Secondly, only symptomatic VTE was recorded, underestimating the total prevalence of VTE [13]. Thirdly, the results of our study are representative of a specialised team working in an institution devoted to orthopaedic surgery and may not be generally applicable.

The overall rate of VTE was low (1.2 %). Despite the fact that no comparison can be made between patients on aspirin and warfarin as chemoprophylaxis was not randomly assigned, the VTE rate was not higher in patients receiving aspirin chemoprophylaxis (1.2 %) than in those receiving warfarin (1.4 %). In our most recent study [14] of patients undergoing elective, primary TKA using multimodal thromboprophylaxis, we compared two groups of patients: one group of 1,016 patients received preferentially aspirin chemoprophylaxis. Warfarin was given only to those at a high risk of VTE or who were on warfarin before surgery. The second group of 1,002 patients received routine warfarin chemoprophylaxis. There was no significant difference in rates of VTE, PE, bleeding, complications, readmission or 90-day mortality between the two groups. However, there was a significantly higher rate of wound-related complications in the control group (p = 0.03). Our study results compare favourably with our institutional historical control of THA patients receiving multimodal thromboprophylaxis and preferential aspirin for chemoprophylaxis. In that study of 1,947 patients operated upon in our institution between 1994 and 2003 [13], the rates of clinical VTE, distal DVT, proximal DVT and PE were 3.1, 0.7, 1.8 and 0.6 %. In addition, our rates of symptomatic PE and 90-day mortality were low (0.5 and 0.2 %, respectively), no higher than those reported by proponents of routine chemoprophylaxis with potent anticoagulants that range from 0.5 to 0.6 % for symptomatic PE and from 0.36 to 0.41 % for all-cause mortality [18]. Similarly, a study by Jameson et al. on over 108,000 patients undergoing TJR receiving either aspirin (21 %) or LMWH (79 %) reported similar PE rates in both groups (0.68 %) [19].

Our study also showed that VTE including PE can occur despite anticoagulation with Coumadin with rates that are similar or higher than those of patients receiving aspirin in our group. Among eight patients who sustained a PE, three had a central thrombus, and of those, two developed haemodynamic instability and/or required a readmission. None of the patients with a segmental or subsegmental PE developed haemodynamic instability. This suggests that there may be a relationship between the location of the PE and the development of symptoms. Auer et al. [20] reported on the relationship between the location of PE and the clinical manifestations. Among 295 patients who developed a PE after cancer treatment, those with a central PE had a higher rate of tachycardia, hypoxia, readmission to the intensive care unit and cardiopulmonary arrest than those with segmental or subsegmental thrombi.

The likelihood of diagnosis of VTE was high during the first week of surgery (seven of 19 patients). And five of 19 VTE patients were diagnosed with a major VTE event within the first three postoperative days (four with a PE and one with a proximal DVT). This is relevant as five of 19 VTE patients required aggressive anticoagulation in close proximity to surgery when the risk of bleeding is the highest.

Despite the diagnosis of a PE, none of the eight patients died during the follow-up period. This suggests that prompt recognition and treatment of this life-threatening complication may not be associated with a high mortality rate. In our most recent meta-analysis on cause of death following almost 100,000 modern TJRs under different thromboprophylaxis regimens, PE was found to be responsible for about 25 % of deaths after surgery [21].

In our series, the rate of bleeding was four times lower for patients receiving aspirin (0.3 %) than for those receiving warfarin (1.6 %). Bleeding after surgery can be a cause of local complications, major organ or retroperitoneal bleed—which we observed in one of our patients—and death. In our previously mentioned meta-analysis, major bleeding was responsible for almost 9 % of deaths following modern TJR [21]. It can therefore be argued that if chemoprophylaxis with Coumadin, LMWH or other potent, expensive anticoagulants is avoided in patients with no predisposing factors for VTE, the overall bleeding rate should diminish.

Our data emphasise that life-threatening complications other than PE occur after surgery and that such complications may contribute to the overall mortality rate. Fourteen patients developed life-threatening complications other than PE during the first 90 days, including myocardial infarction in four, congestive heart failure in three, endocarditis in one and pneumonia in six. Though fatal PE cannot be ruled out as a cause of death in two of our patients, the third patient who died during the follow-up period had no evidence of PE during the autopsy.

The 2008 guidelines by the ACCP [22] recommended against the use of aspirin to prevent VTE after TJR surgery. Nonetheless, the 2012 guidelines give aspirin use a weak recommendation (Grade 2C) [2]. However, the results of our study suggest that a multimodal approach with preferential use of aspirin provides safe and efficacious thromboprophylaxis for elective primary joint replacement. Our low rates of DVT, bleeding and mortality question the superiority of protocols relying on the sole use of expensive, potent anticoagulants for prophylaxis.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially funded by the generous donations of Mr. Glenn Bergenfield, The Sidney Milton and Leoma Simon Foundation, and Dr. and Mrs. Alberto Foglia.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Freedman KB, Brookenthal KR, Fitzgerald RH, Jr, Williams S, Lonner JH. A meta-analysis of thromboembolic prophylaxis following elective total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg. 2000;82:929–938. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200007000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Falck-Ytter Y, Francis CW, Johanson NA, et al. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e278S–e325S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Treasure T, Chong LY, Sharpin C, Wonderling D, Head K, Hill J. Developing guidelines for venous thromboembolism for The National Institute for Clinical Excellence: involvement of the orthopaedic surgical panel. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(5):611–616. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B5.24448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.http://www.cms.hhs.gov/HospitalAcqCond/06_Hospital-Acquired_Conditions.asp

- 5.Butt AJ, McCarthy T, Kelly IP, Glynn T, McCoy G. Sciatic nerve palsy secondary to postoperative haematoma in primary total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:1465–1467. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B11.16736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Callaghan JJ, Dorr LD, Engh GA, Hanssen AD, Healy WL, Lachiewicz PF, Lonner JH, Lotke PA, Ranawat CS, Ritter MA, Salvati EA, Sculco TP, Thornhill TS, American College of Chest Physicians American College of Chest Physicians. Prophylaxis for thromboembolic disease: recommendations from the American College of Chest Physicians–are they appropriate for orthopaedic surgery? J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:273–274. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salvati EA, Sharrock NE, Westrich G, Potter HG, Valle AG, Sculco TP. The 2007 ABJS Nicolas Andry Award: three decades of clinical, basic, and applied research on thromboembolic disease after THA: rationale and clinical results of a multimodal prophylaxis protocol. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;459:246–254. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e31805b7681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beksaç B, González Della Valle A, Anderson J, Sharrock NE, Sculco TP, Salvati EA. Symptomatic thromboembolism after one-stage bilateral THA with a multimodal prophylaxis protocol. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;463:114–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beksaç B, González Della Valle A, Salvati EA. Thromboembolic disease after total hip arthroplasty: who is at risk? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;453:211–224. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000238848.41670.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharrock NE, Go G, Harpel PC, Ranawat CS, Sculco TP, Salvati EA. The John Charnley Award. Thrombogenesis during total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;319:16–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Westrich GH, Farrell C, Bono JV, Ranawat CS, Salvati EA, Sculco TP. The incidence of venous thromboembolism after total hip arthroplasty: a specific hypotensive epidural anesthesia protocol. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14(4):456–463. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(99)90101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bae H, Westrich G, Sculco TP, Salvati EA, Reich LM. The effect of preoperative donation of autologous blood on deep-vein thrombosis after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(5):676–679. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.83B5.10560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.González Della Valle A, Serota A, Go G, Sorriaux G, Sculco TP, Sharrock NE, Salvati EA. Venous thromboembolism is rare with a multimodal prophylaxis protocol after total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;444:146–153. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000201157.29325.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gesell M, Gonzalez Della Valle A, Haas S, Salvati E (2011) Safety and efficacy of multimodal thromboprophylaxis following elective total knee arthroplasty. A comparative study with selective versus routine use of coumadin for chemoprophylaxis. American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons, 21st Annual Meeting, poster presentation

- 15.Memtsoudis SG, González Della Valle A, Besculides MC, Gaber L, Sculco TP. In-hospital complications and mortality of unilateral, bilateral, and revision TKA: based on an estimate of 4,159,661 discharges. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:2617–2627. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0402-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asnis PD, Gardner MJ, Ranawat A, Leitzes AH, Peterson MG, Bass AR. The effectiveness of warfarin dosing from a nomogram compared with house staff dosing. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(2):213–218. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parvizi J, Smith EB, Pulido L, Mamelak J, Morrison WB, Purtill JJ, Rothman RH. The rise in the incidence of pulmonary embolus after joint arthroplasty: is modern imaging to blame? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;463:107–113. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e318145af41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharrock NE, Gonzalez Della Valle A, Go G, Lyman S, Salvati EA. Potent anticoagulants are associated with a higher all-cause mortality rate after hip and knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(3):714–721. doi: 10.1007/s11999-007-0092-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jameson SS, Charman SC, Gregg PJ, Reed MR, Meulen JH. The effect of aspirin and low-molecular-weight heparin on venous thromboembolism after hip replacement: a non-randomised comparison from information in the National Joint Registry. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(11):1465–1470. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B11.27622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Auer RC, Schulman AR, Tuorto S, Gönen M, Gonsalves J, Schwartz L, Ginsberg MS, Fong Y. Use of helical CT is associated with an increased incidence of postoperative pulmonary emboli in cancer patients with no change in number of fatal pulmonary emboli. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208(5):871–878. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poultsides LA, Gonzalez Della Valle A, Memtsoudis SG, Ma Y, Roberts T, Sharrock N, Salvati E. Meta-analysis of cause of death following total joint replacement using different thromboprophylaxis regimens. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(1):113–121. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B1.27301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF, Heit JA, Samama CM, Lassen MR, Colwell CW, American College of Chest Physicians Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition) Chest. 2008;133(6 Suppl):381S–453S. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]