Abstract

Purpose

Osteoporosis mainly involves cancellous bone, and the spine and hip, with their relatively high cancellous bone to cortical bone ratio, are severely affected. Studies of bone mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) from osteoporotic patients and animal models have revealed that osteoporosis is often associated with reduction of BMSCs’ proliferation and osteogenic differentiation. Our aim was to test whether polylactic acid-polyglycolic acid copolymer(PLGA)/collagen type I(CoI) microspheres combined with BMSCs could be used as injectable scaffolds to improve bone quality in osteoporotic female rats.

Methods

PLGA microspheres were coated with CoI. BMSCs of the third passage and were cultured with PLGA/CoI microspheres for seven days. Forty three-month-old female non-pregnant SD rats were ovariectomized to establish osteoporotic animal models. Three months after being ovariectomized, the osteoporotic rats were randomly divided into five groups: SHAM group, PBS group, cell group, microsphere (MS) group, and cell+MS group. Varying materials were injected into the intertrochanters of each group’s rats. Twenty rats were sacrificed at one month and three months post-op, respectively. The femora were harvested in order to measure the intertrochanteric bone mineral density (BMD) with DEXA and trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), percentage of trabecular area (%Tb.Ar), bone volume fraction (BV/TV) and trabecular spacing (Tb.Sp) with Micro CT. One-way ANOVA and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used.

Results

BMSCs seeded on PLGA/CoI microspheres had a nice adhesion and proliferation. At one month post-op, the BMD (0.33 ± 0.01 g/cm2), Tb.Th (459.65 ± 28.31 μm), %Tb.Ar (9.61 ± 0.29 %) and Tb.Sp (2645.81 ± 94.91 μm) of the cell+ MS group were better than those of the SHAM group and the cell group. At three months post-op, the BMD (0.32 ± 0.01 g/cm2), Tb.Th (372.81 ± 38.45 μm), %Tb.Ar (6.65 ± 0.25 %), BV/TV (6.62 ± 0.25 %) and Tb.Sp (1559.03 ± 57.06 μm) of the cell + MS group were also better than those of the SHAM group and the cell group.

Conclusion

The PLGA/CoI microspheres combined with BMSCs can repair bone defects more quickly. This means that PLGA/CoI microspheres combined with BMSCs can promote trabecular reconstruction and improve bone quality in osteoporotic rats. This scaffold can provide a promising minimally invasive surgical tool for enhancement of bone fracture healing or prevention of fracture occurrence which will in turn minimize complications endemic to patients with osteoporosis.

Introduction

Because osteoporosis mainly involves cancellous bone, the spine and hips are severely affected. Patients often appear with vertebral or hip fractures, etc. For patients with vertebral compression fractures, the most commonly used treatments are percutaneous vertebro-plasty (PVP) and percutaneous kyphoplasty (PKP), both of which provide rapid pain relief. However, polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), the most widely used material in these operations, is non-biodegradable and thus can impair bone remodelling, resulting in decreased mechanical strength of the vertebral body [1, 2]. For osteoporotic patients with no fractures, such operations are not suitable [3]. As the need for bone fracture repair is currently one of the major concerns in reconstructive surgery in elderly patients [4], we hope to find a biodegradable material which can promote bone remodelling and quality in the treatment and/or prevention of fractures in osteoporotic patients. Studies of bone mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) from osteoporotic patients and animal models have discovered that osteoporosis is often associated with a reduction of BMSCs’ proliferation and osteogenic differentiation [5, 6], and local injection of normal BMSCs may even improve the bone structure of osteoporotic sites [7]. In order to avoid cellular loss, it is advisable to inject BMSCs in combination with scaffolds [4]. In the area of bone tissue engineering, polylactic acid-polyglycolic acid copolymer (PLGA) is a biodegradable scaffold that has been widely used in vitro as a scaffold for seed cells amplification [8]. PLGA microspheres’ surface is generally hydrophobic and not suitable for cellular adhesion. However, PLGA coated with collagen type I(CoI), an important extracellular matrix of bone, is hydrophilic and can facilitate seeding and cell adhesion [9]. Some studies have even shown that collagen type I can promote BMSCs’ differentiation to osteoblasts [10, 11].

While scaffolds coated with stem cells have reportedly been employed in the treatment of bone defects [12, 13], they have as yet not been reported as a treatment or prevention of osteoporotic fractures. In this research, we established an osteoporotic rat model and injected PLGA/CoI microspheres combined with BMSCs into the rats’ intertrochanters, which contain mainly cancellous bone. Bone mineral density and bone micro-structure were tested to study the scaffold’s ability to improve bone quality of osteoporotic sites.

Materials and methods

Preparation of the osteoporotic animal model

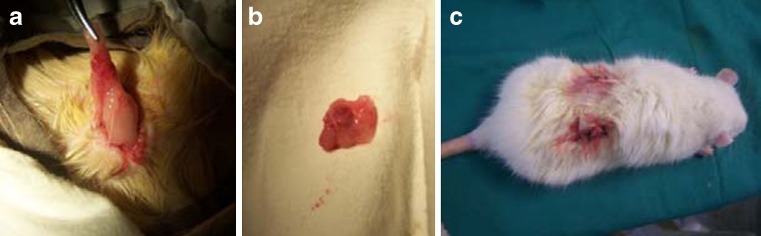

Forty three-month-old female non-pregnant Sprague–Dawley(SD) rats (clear animal) were obtained from the experimental animal center of Peking University First Hospital. The animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care Committee of Peking University. The rats were ovariectomized (Fig. 1). To create the osteoporotic animal model, the castrated rats were housed for three months in a completely clean environment at a room temperature of 23 °C, 56 % humidity, 12 h light to dark intervals, with regular ultraviolet disinfection and ventilation, and unlimited access to food and water.

Fig. 1.

Ovariectomy of rats. a Location of the ovary. b The ovaries at removal. c The incisions

Preparation of PLGA/CoI microspheres combined with BMSCs

Preparation of PLGA/CoI microspheres

PLGA microspheres were prepared according to Chung’s method [14]. The microspheres were separated by means of standard sieves and those microspheres with a diameter of 150–250 μm were collected for the subsequent experiments. The microspheres were soaked in 0.5 % CoI (Santa Cruz, USA) solution overnight at 4 °C and then washed several times with distilled water. The microspheres were sterilized by 24 kGy doses’ γ-irradiation with 60Co as a radiation source at ambient temperature for eight hours.

Isolation and culture of rat BMSCs

Two female SD rats weighing 50 g were obtained from the experimental animal centre of Peking University First Hospital and sacrificed in accordance with the Ethics Committee at Peking University. BMSCs obtained from the bone marrow of the rats were isolated and expanded as previously described [15]. Cells were pooled together. Some cells were induced to differentiate into osteocyte, chondroctye and adipocyte to verify the stem cell property of BMSCs.

Seeded BMSCs on PLGA/CoI microspheres

BMSCs of the third passage were released from substratum with trypsin–EDTA. The cell concentration was changed to 1 × 107/ml by adjusting the amount of PBS. Added to this were 1 ml of DMEM (containing 10 % fetal bovine serum, 1 % penicillin-streptomycin solution), 1 ml of PLGA/CoI microspheres and 1 ml of cell suspension (1 × 107/ml) to each well of six-well plates, and then 4 ml of DMEM (containing 10 % fetal bovine serum and 1 % penicillin-streptomycin solution) was added to each well. One half of the culture medium was changed once a day. On the sixth day, the culture medium had changed into serum-free medium. The BMSCs were cultured with PLGA/CoI microspheres for seven days. On the seventh day, the medium was discarded enabling collection of the MS. Some MS were used for investigation by means of scanning electron microscopy (SEM, JSM-6700F, JEOL Company, Japan) and the remainder was for research in vivo.

Preparation of injectable materials for the in vivo experiment

According to the experimental design, four kinds of materials were prepared: 1.2 ml of PBS (PBS group), 1.2 ml of BMSCs suspension of the third passage (1 × 107/ml) (cell group), 1.2 ml of PLGA/CoI microspheres suspension (MS group) and 1.2 ml of the suspension of PLGA/CoI microspheres combined with BMSCs (cell+MS group).

Injection of different material into the intertrochanter region in vivo

Forty ovariectomized rats that had been castrated for three months were randomly divided into five groups: SHAM group, PBS group (injected with PBS), cell group (injected with BMSCs of the third passage), MS group (injected with PLGA/CoI microspheres) and cell+ MS group (injected with PLGA/CoI microspheres combined with BMSCs). After anaesthesia with intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg), the rat was placed in prone position on the operation panel. Under sterile conditions, a longitudinal incision was made on the surface of the greater trochanter of the femur. After exposing the bilateral femoral greater trochanters, an electric drill was used to create a 3-mm deep and 2.5-mm diameter bone defect in the direction from the greater trochanter to the lesser trochanter. A total of 30 μl of PBS, suspension of MSCs (1 × 107/ml), PLGA/CoI microspheres or PLGA/CoI microspheres combined with BMSCs were injected into the bone defects of the different groups. The periosteum was sutured in order to secure the material inside the bone defects. Muscle and skin were sutured. In the SHAM group, the incision, exposure and suture were made in the same manner. The injection was given once after the OVX surgery. The rats were sacrificed and the femora were removed at one month and three months, respectively, after injection. The soft tissues of the femora were stripped and prepared for further investigation.

Measurement of intertrochanteric bone density

The femora specimens were placed under the probe of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA, QDR-4500A, HOLOGIC, US) and scanned with small animal software to measure the intertrochanteric bone mineral density.

Evaluation of intertrochanteric trabecular structure

The qualitative and quantitative information of the micro-structure of the intertrochanteric trabecular was obtained by micro-computed tomography (Micro CT, Skyscan Company, Belgium). Scanning parameters were 80 kV voltage and 6.8 μm resolution. The femur was interrupted perpendicularly to the longitudinal axis, along the subtrochanteric edge. The proximal part was placed along the long axis into the sample container to measure the intertrochanteric bone morphometry parameters.

Parameters of bone morphology were as follows:

- Trabecular thickness (Tb.Th)

Used to describe the morphology of trabecular structure and explain the change in bone mass. In the case of a fixed number of trabeculars, the greater the Tb.Th, the greater the bone mass.

- Percentage of trabecular area (%Tb.Ar)

Mean trabecular area percentage of the total bone tissue area, reflecting the amount of bone.

- Bone volume fraction (BV/TV)

The ratio of bone structure voxels and the total voxels in the region; the smaller the BV/TV, the more porous the bone.

- Trabecular spacing (Tb.Sp)

The average distance between the trabeculars; the greater the Tb.Sp, the greater the distance between the trabeculars and the more porous is the bone.

Statistical analysis

The results were analysed with the SPSS 13.0 statistical software. All results were expressed with mean ± standard deviation. If the variance was homogeneous in the normality test (P value > 0.05), one-way ANOVA was used. In the ANOVA test, a P value <0.05 indicated that at least a pair of data had significant difference, and least squares difference (LSD) test was used to compare the data of any two groups. If the variance was heterogeneous (P value < 0.05), Kruskal-Wallis test was used. Mann–Whitney test was used to compare the data of any two groups. In nonparametric multiple comparisons, the pairwise comparison test level was adjusted to 0.05/10 = 0.005.

Results

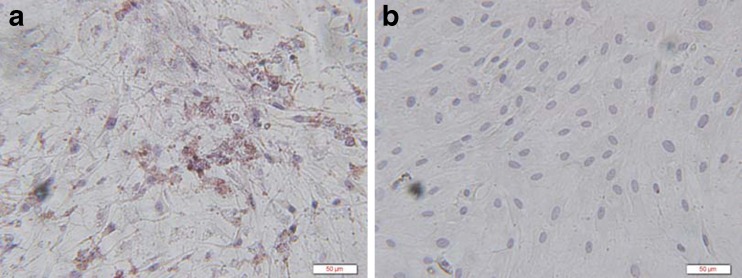

The stem cells we used had the stem cell property of multilineage differentiation such as osteogenic differentiation (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Bone mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) with osteogenic induction showed positive for collagen type I with brown cytoplasm (a), BMSCs without osteogenic induction showed negative (b) (immunohistochemistry staining × 400)

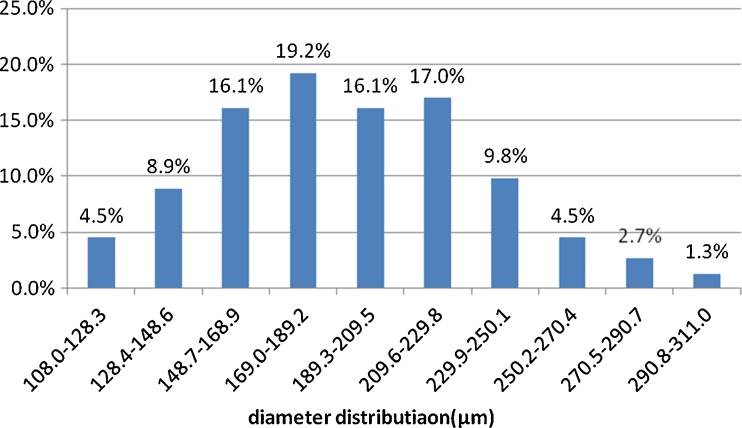

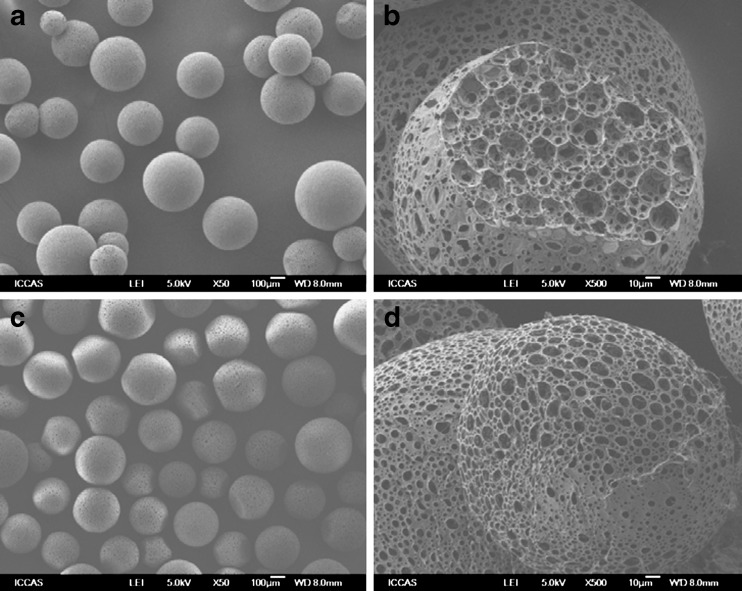

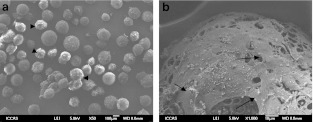

Microspheres with collagen coating were clearly visible under the SEM. After coculture with BMSCs for seven days, SEM showed that the diameter distribution of microspheres was uniform; the diameter of most of the microspheres was between 150 to 250 μm, and a large number of BMSCs adhered and proliferated on the PLGA/CoI microspheres (Graph 1, Figs. 3 and 4).

Graph 1.

The diameter distribution of 224 microspheres that we used in our research

Fig. 3.

Structure of PLGA microspheres (SEM). a, b Microspheres without CoI (magnification of a × 50, magnification of b × 500). c, d Microspheres coated by CoI (magnification of c × 50, magnification of d × 500); there was a lot of collagen coated on the surface of microspheres

Fig. 4.

Bone mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) cultured with CoI in vitro for 7 days (SEM): magnification of a × 50, magnification of b × 1000, a large number of BMSCs (black arrows) combined with polylactic acid-polyglycolic acid copolymer (PLGA) microspheres

All the rats survived the surgery without complications. At one and three months observation time points, no difference in weight was observed.

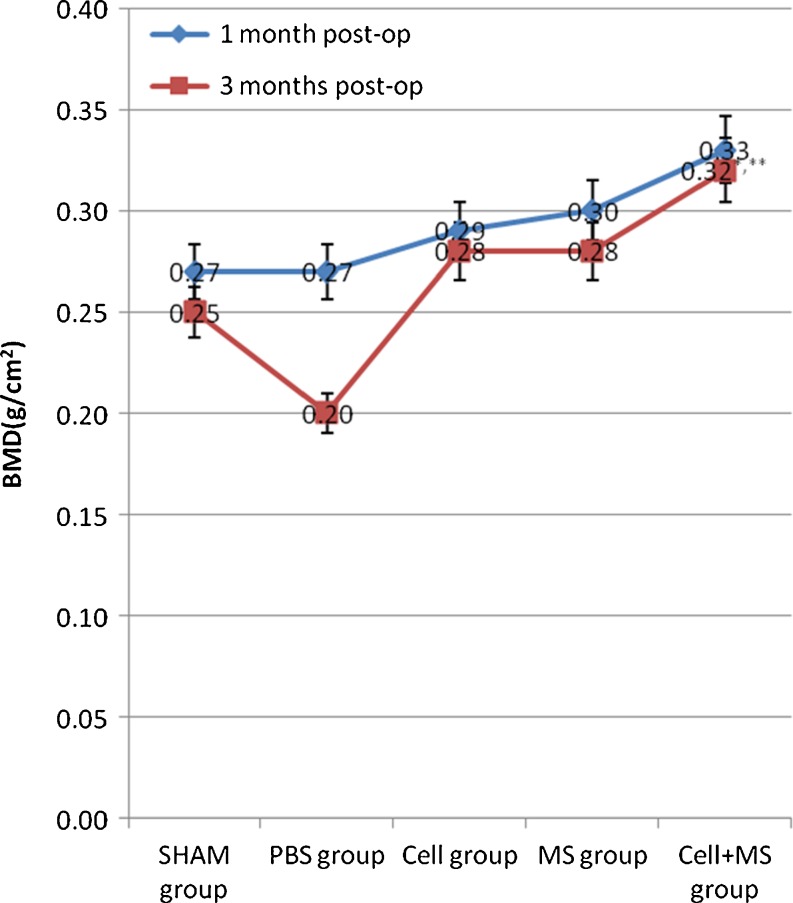

DEXA scanning results showed that the intertrochanteric bone mineral density (BMD) of each group had no significant difference (P value = 0.073) at one month post-op, but a tendency towards increased BMD was found in the cell + MS group (0.33 ± 0.01 g/cm2) compared with other groups (Graph 2). At three months post-op, a significant difference was found between the groups with the highest BMD in the cell + MS group (Graph 2).

Graph 2.

Intertrochanteric bone mineral density (BMD) in different groups at one month post-op and three months post-op. * Compared with SHAM group at 3 months post-op, P < 0.001. ** Compared with cell group at three months post-op, P = 0.008

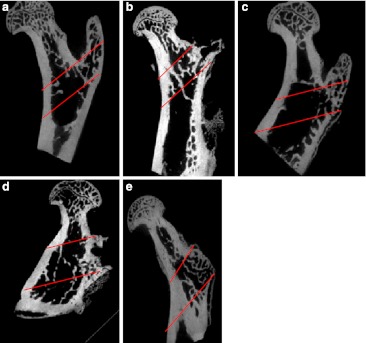

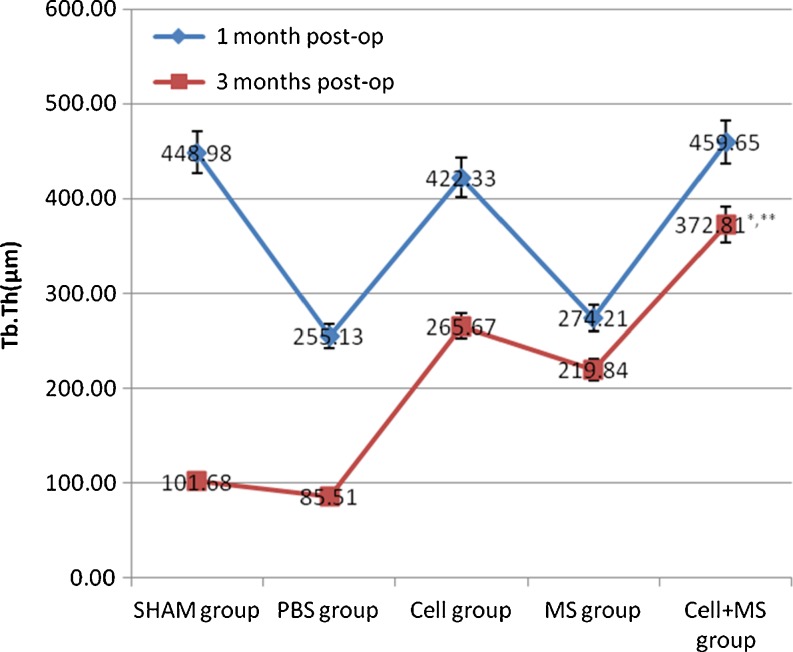

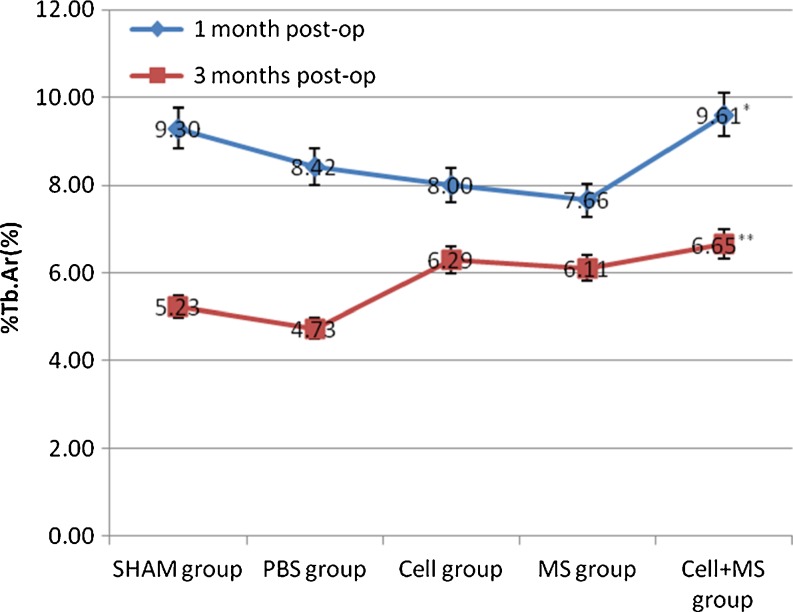

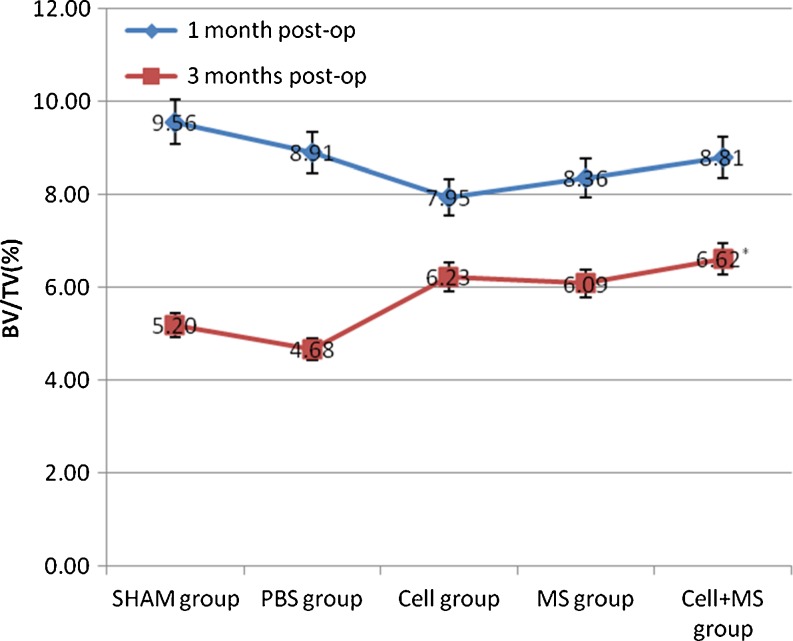

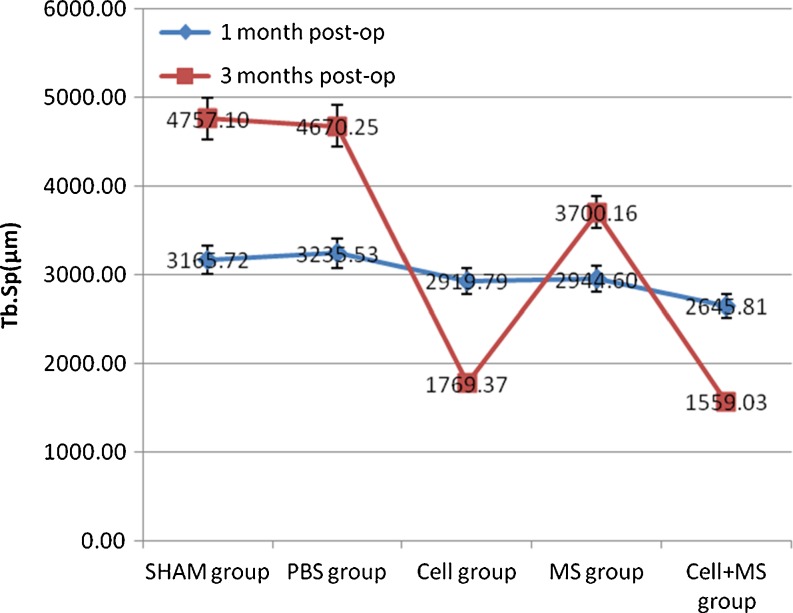

The Tb.Th, %Tb.Ar and Tb.Sp of each group had significant differences at one month and three months post-op, and the BV/TV of each group had significant differences at three months post-op (Fig. 5 and Graphs 3, 4, 5 and 6). At one month post-op, the Tb.Th of the cell + MS group was significantly greater than that of the PBS group (P value < 0.001) and the MS group (P value < 0.001), and had an increasing tendency (P value = 0.162) compared with that of the cell group, but had no significant difference compared with that of the SHAM group (P value = 0.680) (Graph 3). At three months post-op, the Tb.Th of the cell + MS group was significantly greater than that of the other groups (Graph 3). At one month post-op, %Tb.Ar of the cell + MS group was significantly greater than that of the cell group (P value = 0.029) and MS group (P value = 0.010), and had an increasing tendency (P value = 0.093) compared with that of the PBS group, but had no significant difference compared with that of the SHAM group (P value = 0.651) (Graph 4). At three months post-op, %Tb.Ar of the cell + MS group was significantly greater than that of the SHAM group (P value = 0.009) and the PBS group (P value = 0.01), but had no significant difference compared with that of the cell group (P value = 0.454) and the MS group (P value = 0.270) (Graph 4). At one month post-op, the BV/TV had no significant difference within groups (P value = 0.112) (Graph 5). At three months post-op, the BV/TV of the cell + MS group was significantly greater than that of the SHAM group (P value = 0.009) and the PBS group (P value = 0.001), but had no significant difference compared with that of the cell group (P value = 0.416) and the MS group (P value = 0.274) (Graph 5). When variance was heterogeneous, in nonparametric multiple comparisons, the pairwise comparison test level was adjusted to 0.05/10 = 0.005, so that at one month post-op, the Tb.Sp of the cell + MS group had no significant difference compared with that of the other groups but a decreasing tendency compared with that of the SHAM group (P value = 0.021), the PBS group (P value = 0.021) and the MS group (P value = 0.043) (Graph 6). At three months post-op, the Tb.Sp of the cell + MS group also had no significant difference but a decreasing tendency (P value = 0.021) compared with that of the other groups (Graph 6).

Fig. 5.

Rats’ intertrochanters at one month post-op (Micro CT) from the SHAM group (a), PBS group (b), cell group (c), MS group (d) and cell+ MS group (e). Standard ROI (region of interest) between the greater trochanter and the lesser trochanter was chosen (cancellous bone area between the two red parallel lines)

Graph 3.

Intertrochanteric Tb.Th(μm) in different groups at one month post-op and three months post-op. * Compared with SHAM group at three months post-op, P < 0.001. ** Compared with cell group at three months post-op, P = 0.003

Graph 4.

Intertrochanteric %Tb.Ar(%) in different groups at one month post-op and three months post-op. * Compared with cell group at 1 months post-op, P = 0.029. ** Compared with SHAM group at three months post-op, P = 0.009

Graph 5.

Intertrochanteric BV/TV(%) in different groups at one month post-op and three months post-op. * Compared with SHAM group at three months post-op, P = 0.009

Graph 6.

Intertrochanteric Tb.Sp(μm) in different groups at one month post-op and three months post-op

Discussion and conclusion

Osteoporosis is a disease manifested by drastic bone loss resulting in osteopenia and high fracture risk [16, 17]. Previous investigations have discovered that osteoporosis may lead to decrease in BMSCs’ organelles, reduction of BMSCs’ viability, differentiation of BMSCs into adipocytes and decreased proliferation of BMSCs in vitro [5, 18]. In senile osteoporosis, the molecule that maintains telomerase stability gradually diminishes, causing the telomerase to shorten, thus shortening the BMSCs and osteoblasts’ life cycle which results in osteoporosis [19]. Rats are the most commonly used osteoporosis model [20]. Osteoporotic fractures and bone loss sites in ovariectomized female rats display a marked similarity to human fractures and bone loss sites. Osteoporotic fractures occur mainly in cancellous bone, such as the metaphysis of long bones and vertebrae, which has a high turnover rate [21]. In this research, we used a well-established osteoporotic rat model; we selected the osteoporotic rats’ intertrochanter as the site of creating bone defect in order to study injectable PLGA/CoI microspheres scaffolds compared with different control groups. The continuous decrease of intertrochanteric BMD from one month post-op to three months post-op in the SHAM group confirmed the osteoporotic model. At one month post-op, we found that the intertrochanteric BMD of cell + MS group had an increasing tendency compared with those of the SHAM and cell groups. The %Tb.Ar of the cell + MS group was greater than that of the cell group. At three months post-op, we found that the intertrochanteric BMD and bone morphologic parameters, such as Tb.Th, %Tb.Ar and BV/TV, of the cell + MS group were greater than those of the SHAM group and the Tb.Sp of the cell + MS group had a decreasing tendency compared with that of the SHAM group. The BMD and Tb.Th of the cell + MS group were also greater than those of the cell group. The Tb.Sp of the cell + MS group had a decreasing tendency compared with that of the cell group.

Ocarino et al. [7] found that local injection of BMSCs could even improve bone structure of osteoporotic bone. In our research, we found that the bone mineral density and bone morphologic parameters of the cell group had no significant difference compared with those of the SHAM group at one month post-op, but the Tb.Th of cell group was greater than that of the PBS group and MS group. The BMD, Tb.Th, %Tb.Ar and BV/TV of the cell group were significantly greater than those of the SHAM group and the PBS group at three months post-op. This showed that injection of normal BMSCs into an osteoporotic site could improve local bone quality to a certain extent. However, if we inject the BMSCs only into bone defects, the cells with medium solution must be handled carefully in order to avoid cell dilution which could easily result in loss of cells, thereby making it difficult to achieve effective cell concentration in the local area. In this research, PLGA/CoI microspheres combined with BMSCs could secure the BMSCs at the injection site. PLGA has been widely used in the area of bone tissue engineering [8]. We produced microspheres with a diameter of 150–250 μm which could be used in minimally invasive surgical procedures. In the pre-experiment phase of this research, we found that coating CoI onto PLGA microspheres could increase the proportion of hydrophilic groups, making the microspheres hydrophilic and thus facilitating cell attachment; this could result in good BMSCs adhesion and proliferation on 3D material. Hesse et al. [10] reported that BMSCs cultured with collagen type I hydrogels could differentiate into osteoblasts. We also found that compared with BMSCs on untreated PLGA microspheres, the AKP activity was higher, osteocalcin level was higher and collagen type I mRNA expression had an increasing tendency in BMSCs on PLGA/CoI microspheres. This meant that PLGA/CoI microspheres had a certain ability to induce BMSCs’ osteogenic differentiation [22]. Reports from the area of bone tissue engineering indicate that the concentration of osteoblasts seeded on scaffolds should be about 106 ∼ 107/ml [23]. In this research, we cultured the third passage of BMSCs (1 × 107/ml) with PLGA/CoI microspheres in vitro for 7 days. Observation by means of SEM showed that a large number of cells adhered to and proliferated on the microspheres. Ben-David et al. [24] and Lyons et al. [25] reported that 2.5 × 105 or 5 × 105 BMSCs were seeded on the scaffolds and implanted in vivo to repair bone defects, so in our research, we injected 30-μl scaffold and/or BMSCs with initial concentration of 1 × 107/ml into the bone defect of the intertrochanter.

BMD can directly reflect change in bone mass [26]. In our research, DEXA was used to measure rats’ BMD. The BMD of the cell + MS group had an increasing tendency compared with the other groups at one month post-op, indicating that one month after injection of PLGA/CoI microspheres combined with BMSCs, the BMD at the injection site at least met or even exceeded those of the SHAM and cell groups. At three months post-op, the cell + MS group’s intertrochanteric BMD was significantly greater than the other groups’. This indicated that PLGA/CoI microspheres combined with BMSCs could improve the BMD of osteoporotic sites.

However, BMD and bone strength are sometimes not entirely consistent. Ebbesen et al. [27] found that BMD could account for only 40–50 % of the effect on total bone strength; bone structure had a greater impact on bone strength. Thus, in the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis, bone structural change has great significance. Micro-CT is an accurate, 3D and non-invasive method of measuring bone microstructure, assessing bone quality and predicting bone strength [28, 29]. The 3D measurement and 3D imaging method can be directly used for bone morphogenetic parameters. The measured parameters are highly compatible with traditional morphometric parameters [30]. It was reported that because neogenetic trabecular bone was less and the connections were reduced, osteoporosis would affect fracture healing in rats [31, 32]. In this research, Tb.Th, %Tb.Ar and BV/TV of the cell + MS group at one month post-op had no significant difference compared with those of the SHAM group. The %Tb.Ar of the cell + MS group was greater than that of the cell group, and Tb.Th and BV/TV of the cell + MS group had increasing tendencies compared with those of the cell group, demonstrating that bone mass in the cell + MS group’s injection site approached that of the SHAM group and exceeded that of the Cell group. The Tb.Sp of the cell + MS group had no significant difference but a decreasing tendency compared with those of the SHAM, PBS and MS groups. This is probably attributable to the small sample size. In short, the results of Micro-CT at one month post-op discovered that bone structure at the cell + MS group’s injection site was close to that of the SHAM group and was to a certain degree better than that of other control groups, such as the cell group. The Tb.Th of the cell + MS group at three months post-op was significantly greater than that of other groups. The %Tb.Ar and BV/TV of the cell + MS group were significantly greater than those of the SHAM group and PBS group. These demonstrated that bone mass at the cell + MS group’s injection site was more than that in the SHAM and cell group. In brief, the results of Micro-CT at three months post-op revealed that bone structure at the injection site of the cell + MS group was better than that of the SHAM and cell groups. This indicated that PLGA/CoI microspheres combined with BMSCs promoted to a certain extent the reconstruction of trabecular bone in osteoporotic sites and improved bone quality.

We found that bone quality declined from one month post-op to three months post-op (Graphs 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6), meaning that osteoporosis progresses with time. However, the bone quality of the cell + MS group declined more slowly than that of the other groups, meaning that PLGA/CoI microspheres combined with BMSCs can delay the development of osteoporosis.

One limitation of this research is that the osteoporotic animal model we used is the rat which maintains an active bone modelling in life and bears the load in different ways compared with humans. The second limitation is that the injection site we selected in this research was the intertrochanter of the femur, which is irregularly shaped for biomechanical testing. The third limitation is that we only studied the BMD and static parameters of bone histomorphometry such as Tb.Th, %Tb.Ar, BV/TV and Tb.Sp. In the future, we can use the PLGA/CoI microspheres combined with BMSCs in the mammalian model of osteoporosis and use bone histomorphometry of bone biopsy to study the dynamic parameters of bone formation, deposition and absorption.

In conclusion, we produced PLGA/CoI microspheres (diameter 150–250 μm), and the BMSCs were successfully seeded on the microspheres in vitro. The scaffolds of PLGA/CoI microspheres combined with BMSCs were injected into osteoporotic sites of the animal model. At one month and three months post-op, we found that compared with other groups, such as the cell group, the PLGA/CoI microspheres combined with BMSCs could repair bone defect more quickly, promote trabecular reconstruction and improve bone quality in osteoporotic rats. This material can be useful for bone regeneration through minimally invasive surgical procedures in the treatment and prevention of osteoporotic fractures.

References

- 1.Chiu R, Smith KE, Ma GK, et al. Polymethylmethacrylate particles impair osteoprogenitor viability and expression of osteogenic transcription factors Runx2, osterix, and Dlx5. J Orthop Res. 2010;28(5):571–577. doi: 10.1002/jor.21035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiu R, Ma T, Smith RL, et al. Kinetics of polymethylmethacrylate particle-induced inhibition of osteoprogenitor differentiation and proliferation. J Orthop Res. 2007;25(4):450–457. doi: 10.1002/jor.20328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kallmes DF, Jensen ME. Percutaneous vertebroplasty. Radiology. 2003;229(1):27–36. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2291020222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Srouji S, Livne E. Bone marrow stem cells and biological scaffold for bone repair in aging and disease. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;126(2):281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodríguez JP, Garat S, Gajardo H, et al. Abnormal osteogenesis in osteoporotic patients is reflected by altered mesenchymal stem cells dynamics. J Cell Biochem. 1999;75(3):414–423. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(19991201)75:3<414::AID-JCB7>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pountos I, Georgouli T, Henshaw K, et al. The effect of bone morphogenetic protein-2, bone morphogenetic protein-7, parathyroid hormone, and platelet-derived growth factor on the proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells derived from osteoporotic bone. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24(9):552–556. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3181efa8fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ocarino Nde M, Boeloni JN, Jorgetti V, et al. Intra-bone marrow injection of mesenchymal stem cells improves the femur bone mass of osteoporotic female rats. Connect Tissue Res. 2010;51(6):426–433. doi: 10.3109/03008201003597049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park JS, Yang HN, Jeon SY, et al. Osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells using RGD-modified BMP-2 coated microspheres. Biomaterials. 2010;31(24):6239–6248. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen G, Okamura A, Sugiyama K, et al. Surface modification of porous scaffolds with nanothick collagen layer by centrifugation and freeze-drying. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2009;90(2):864–872. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hesse E, Hefferan TE, Tarara JE, et al. Collagen type I hydrogel allows migration, proliferation, and osteogenic differentiation of rat bone marrow stromal cells. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;94(2):442–449. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang XB, Bhatnagar RS, Li S, et al. Biomimetic collagen scaffolds for human bone cell growth and differentiation. Tissue Eng. 2004;10(7–8):1148–1159. doi: 10.1089/ten.2004.10.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ben-Ari A, Rivkin R, Frishman M, et al. Isolation and implantation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells with fibrin micro beads to repair a critical-size bone defect in mice. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15(9):2537–2546. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langenbach F, Naujoks C, Laser A, et al. Improvement of the cell-loading efficiency of biomaterials by inoculation with stem cell-based microspheres, in osteogenesis. J Biomater Appl. 2012;26(5):549–564. doi: 10.1177/0885328210377675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung HJ, Kim IK, Kim TG, et al. Highly open porous biodegradable microcarriers: in vitro cultivation of chondrocytes for injectable delivery. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14(5):607–615. doi: 10.1089/tea.2007.0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang Y, Jia X, Bai K, et al. Effect of fluid shear stress on cardiomyogenic differentiation of rat bone marrow mesenchymalstem cells. Arch Med Res. 2010;41(7):497–505. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turgeman G, Zilberman Y, Zhou S, et al. Systematically administered rhBMP-2 promotes MSC activity and reverses bone and cartilage loss in osteopenic mice. J Cell Biochem. 2002;86(3):461–474. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strømsøe K. Fracture fixation problems in osteoporosis. Injury. 2004;35(2):107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2003.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffith JF, Wang YX, Zhou H, et al. Reduced bone perfusion in osteoporosis: likely causes in an ovariectomy rat model. Radiology. 2010;254(3):739–746. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09090608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pignolo RJ, Suda RK, McMillan EA, et al. Defects in telomere maintenance molecules impair osteoblast differentiation and promote osteoporosis. Aging Cell. 2008;7(1):23–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00350.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kharode YP, Sharp MC, Bodine PV. Utility of the ovariectomized rat as a model for human osteoporosis in drug discovery. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;455:111–124. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-104-8_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chachra D, Lee JM, Kasra M, et al. Differential effects of ovariectomy on the mechanical properties of cortical and cancellous bones in rat femora and vertebrae. Biomed Sci Instrum. 2000;36:123–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu ZR, Li CD, Shi XD, et al. Influence of polylactic/poly glycolic acid microspheres modified by collagen type I on the adhesion and osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. J Clin Rehabil Tissue Eng Res. 2011;15(42):7868–7872. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hasegawa Y, Ohgushi H, Ishimura M, et al. Marrow cell culture on poly-L-lactic acid fabrics. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;358:235–243. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199901000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ben-David D, Kizhner TA, Kohler T, et al. Cell-scaffold transplant of hydrogel seeded with rat bone marrow progenitors for bone regeneration. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2011;39(5):364–371. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lyons FG, Al-Munajjed AA, Kieran SM, et al. The healing of bony defects by cell-free collagen-based scaffolds compared to stem cell-seeded tissue engineered constructs. Biomaterials. 2010;31(35):9232–9243. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ammann P, Rizzoli R, Slosman D, et al. Sequential and precise in vivo measurement of bone mineral density in rats using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry. J Bone Miner Res. 1992;7(3):311–316. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650070310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ebbesen EN, Thomsen JS, Mosekilde L. Nondestructive determination of iliac crest cancellous bone strength by pQCT. Bone. 1997;21(6):535–540. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(97)00196-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang Y, Zhao J, Liao EY, et al. Application of micro-CT assessment of 3-D bone micro-structure in preclinical and clinical studies. J Bone Miner Metab. 2005;23(Suppl):122–131. doi: 10.1007/BF03026336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang SY, Vashishth D. A non-invasive in vitro technique for the three-dimensional quantification of microdamage in trabecular bone. Bone. 2007;40(5):1259–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arlot ME, Jiang Y, Genant HK, et al. Histomorphometric and micro-CT analysis of bone biopsies from postmenopausal osteoporotic women treated with strontium ranelate. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23(2):215–222. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.071012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hao YJ, Zhang G, Wang YS, et al. Changes of micro-structure and mineralized tissue in the middle and late phase of osteoporotic fracture healing in rats. Bone. 2007;41(4):631–638. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Namkung-Matthai H, Appleyard R, Jansen J, et al. Osteoporosis influences the early period of fracture healing in a rat osteoporotic model. Bone. 2001;28(1):80–86. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(00)00414-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]