Abstract

Context

The use of the Internet for peer-to-peer connection has been one of its most dramatic and transformational features. Yet this is a new field with no agreement on a theoretical and methodological basis. The scientific base underpinning this activity needs strengthening, especially given the explosion of web resources that feature experiences posted by patients themselves. This review informs a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) (UK) research program on the impact of online patients’ accounts of their experiences with health and health care, which includes the development and validation of a new e-health impact questionnaire.

Methods

We drew on realist review methods to conduct a conceptual review of literature in the social and health sciences. We developed a matrix to summarize the results, which we then distilled from a wide and diverse reading of the literature. We continued reading until we reached data saturation and then further refined the results after testing them with expert colleagues and a public user panel.

Findings

We identified seven domains through which online patients’ experiences could affect health. Each has the potential for positive and negative impacts. Five of the identified domains (finding information, feeling supported, maintaining relationships with others, affecting behavior, and experiencing health services) are relatively well rehearsed, while two (learning to tell the story and visualizing disease) are less acknowledged but important features of online resources.

Conclusions

The value of first-person accounts, the appeal and memorability of stories, and the need to make contact with peers all strongly suggest that reading and hearing others’ accounts of their own experiences of health and illnesss will remain a key feature of e-health. The act of participating in the creation of health information (e.g., through blogging and contributing to social networking on health topics) also influences patients’ experiences and has implications for our understanding of their role in their own health care management and information.

Keywords: e-health, review, theory, patients' experiences

The internet fundamentally shapes our experiences of the everyday, including our experiences of health and illness. All those involved in health care (doctors, nurses, patients, potential patients) are actively experimenting with using the web to exchange information. In a Milbank Quarterly article entitled “Doctors in a Wired World,” David Blumenthal (2002) challenged the skepticism and concern about the impact of the Internet on the profession of medicine. Eight years later, however, this skepticism had considerably abated:

The prospect of a wired health care world has become a kind of Rorschach test, distinguishing physician optimists from physician pessimists. Optimists anticipate an idealized world of health care perfection … pessimists foresee an endless struggle in their daily work in which patients drop sheaves of misleading Internet print-outs on their desks. (Blumenthal 2010, 8)

Online resources are now established as a primary route to health information and support. In the past, authoritative health information was based on scientific information, often presented as evidence-based “facts and figures,” rather than on patients’ experiences. When health problems are commonly experienced (such as winter colds and flu or headaches), people have their own embodied experience to draw on when deciding whether and how to act (self-management, decisions to consult, and so on) (Dingwall 2001; Leventhal, Brisette, and Leventhal 2003). However, people wondering whether a symptom is worth concern or attention, facing a new diagnosis or health-related decision, or living with a long-term condition and encountering new problems, often feel that they need to know how others comprehend what they are going through (Gabriel 2004). A study of parents of children with a genetic condition (Schaffer, Kuczynski, and Skinner 2008) found that the most trusted and valued source of information was not doctors but the other parents in the online communities, whose own extensive Internet searches were combined with a personal stake. As cancer patient Dave de Bronkert (Aka e-Patient Dave) put it, “Patients know what patients need to know” and are, therefore, the most under used resource in healthcare (see http://www.ted.com/conversations/4547/why_is_the_patient_the_most_u.html).

The 2010 Pew Internet national survey of 3,000 respondents in the United States reported the extent of peer-to-peer help among people living with chronic conditions as its “most striking” finding: One in four Internet users living with a chronic condition, such as high blood pressure, diabetes, heart or lung problems, or cancer, reported going online to find others with similar health concerns (Fox 2011).

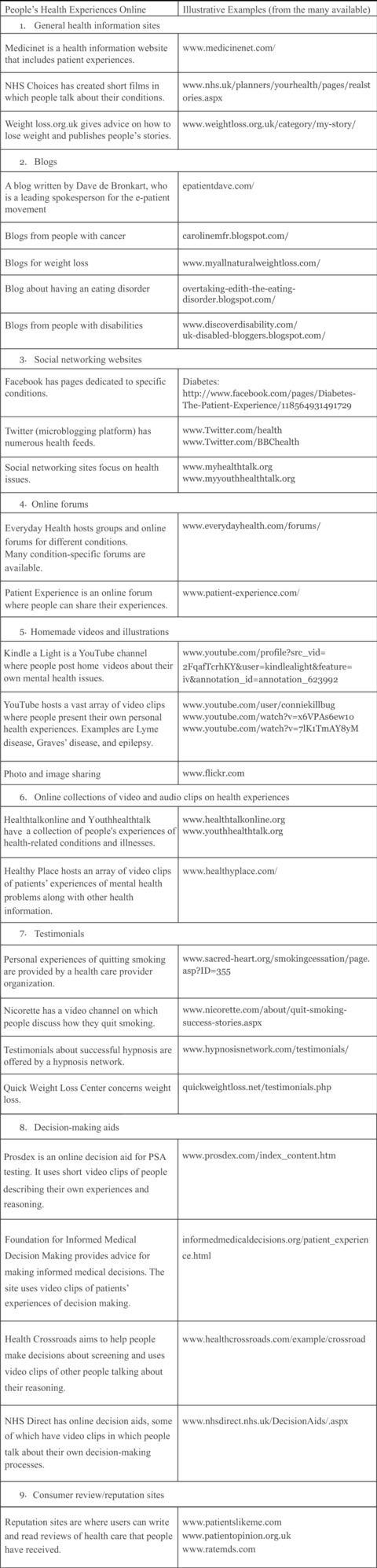

Hearing or reading about other patients’ experiences has the potential to affect decision making, one's sense of isolation or support, and adjustment to the illness or health condition. The peer-to-peer support group movement has been the trailblazer in addressing this need. Online communities and websites, available worldwide at any time, both supplement and (in some ways) surpass face-to-face groups. In 2011 many more people visited websites without themselves posting (an activity described somewhat pejoratively as “lurking”) than contributed (Fox 2011; Preece, Nonnecke, and Andrews 2004). But this may change through web 2.0 platforms, which provide a shared, user-driven environment and are making it even easier for users to collaborate in developing content, sharing information, uploading videos and photos, and sharing and commenting on personal experiences. The widespread use of social media transcends educational achievement, race and ethnicity, and level of health care access (Chou et al. 2009). Figure 1 outlines the main ways in which people's health experiences currently appear online.

FIGURE 1.

Examples of patients' experiences online.

Note: All sites accessed in September 2011.

Traditional off-line forms of contact and support are limited to certain hours of the day, week, or month; some face-to-face support groups meet less than once a month and may require considerable travel and effort. Even telephone help lines are likely to be available only during office hours. An indisputably transformational feature of the Internet is that contact and support are now available at any hour of the day or night and that those with a home computer can access an extraordinary range of resources for private and anonymous communications with others in real time (Buchanan and Coulson 2007).

Although these developments are increasingly seen as encouraging, little is known about the effect on people's health outcomes of the 24/7 access (which can also be anywhere on any device) to other people's experiences online. The immediacy of contact with people all over the world could provide reassurance and support during unsocial hours; the anonymous environment may permit people to raise embarrassing questions that many would find hard to discuss face to face. But it could also provoke concerns and anxieties that may be difficult to deal with in the middle of the night. The implications are global: access is usually not limited to any model of health care delivery, although there clearly are differences in local policy and provision and likely consequences for health care demand.

Health policymakers have begun to recognize the potential of the Internet as a source of patients views’ and experiences. For example, the United Kingdom's NHS Future Forum Report on Information (2012) talks of “a new culture of transparency and public voice being fuelled by the digital revolution.” Patients’ experiences, gathered and disseminated on the Internet, are to be a central plank of this culture change. The NHS Operating Framework (NHS 2011) describes “each patient's experience” as “the final arbiter in everything the NHS does.” Individual patients have a particular vantage point on how the system is working (or not) while they are in it, and yet they may suspect that their experience is not typical (Ziebland, Evans, and Toynbee 2011) or be otherwise disinclined to comment, even if prompted by a survey questionnaire from the hospital. In comparison, web-based feedback sites, populated with comments from other patients, may describe comparable experiences and can be a highly efficient way to identify pressing concerns, such as for patient safety, as well as for longer-term quality improvement. Hearing the experiences of other people is thought to be particularly powerful in helping patients make choices, particularly between treatment options: online People's Experiences (PEx) would therefore be expected to support the continued British policy focus on “patient choices.”

Some online presentations of “patients’ experiences,” such as fabricated testimonials or comments on services, may combine a powerful and memorable delivery with an unbalanced, or misleading, message. Dillard and colleagues (2010, 45) noted, for example, that “perceptions of barriers could be reduced by providing individuals with an indirect, vicarious experience” so that they are manipulated to choose a particular option when making a health care decision. The features that make firsthand accounts compelling, and the mechanisms through which they operate, remain poorly understood. Among the more pressing questions are, How do people find and interpret online patients’ experiences and relate them to their own lives? What are the positive and negative consequences? How might this affect their health and well-being? How do we measure these effects? Do patients’ experiences have more value than facts and figures? How might experiential information be best presented to help people with different levels of health literacy?

The role of information based on online patients’ experience is a new field with no agreed-on theoretical and methodological basis. The scientific base and policy guidance underpinning this activity need strengthening, especially given the explosion of resources that now feature experiential information (see figure 1). In this article we draw on a wide literature in the social and health sciences to provide an overview, or conceptual map, of the potential health effects of online patients’ experience in health and health care. We describe seven key aspects of the terrain, discussing what mechanisms might be operating on which outcomes in each.

Methods

Our study had three stages: a literature review, a service user panel, and a final review and revision after we presented our initial findings at a specialists’ workshop.

Literature Review

Our approach to the overview was informed by realist review, a method for synthesizing research evidence regarding complex interventions (Pawson 2006; Pawson et al. 2005). It is based on a simple idea, that research should pass on collective wisdom about the successes and failures of previous initiatives in particular policy domains “before the leap into policy and practice” (Pawson 2006, 8). Its main purpose is to identify explanations through which complex social programs might operate so that policymakers can learn how to introduce or adapt programs based on a good understanding of why and how they might work. Realist review offers a useful framework for identifying and managing syntheses of existing research and has been applied in such fields as lean thinking in health care (Mazzocato et al. 2010), school feeding programs (Greenhalgh, Kristjansson, and Robinson 2007), Internet-based medical education (Wong, Greenhalgh, and Pawson 2010), social diffusion in health care (Greenhalgh et al. 2004), and social networks and social capital in the self-management of chronic illness (Vassilev et al. 2011).

This approach was suited to our task because just as in the literature on health care management and policy-level interventions for which realist review methods were developed, the science of the role of information based on online patients’ experience is epistemologically complex and methodologically diverse (Pawson et al. 2005). However, in our case, there was no set of theories or even defined social or health programs to identify and evaluate; the field is too new. We therefore adapted the approach to allow us to identify and describe the domains of the territory. Our approach was iterative and collaborative; both of us worked intensively face to face, through emails, and by telephone over six months in 2010. Box 1 summarizes the review's five overlapping steps.

Box 1

Summary of the Steps Taken to Develop a “Conceptual Map” of the Operation and Effects of Online Patients’ Experiences

Step 1: Clarification of Scope

We settled on the review question: “What is written in peer-reviewed journals and scholarly books about the health effects of access to and use of online patients’ experiences?”

We refined the purpose of our review: to provide “a conceptual map” of what is known about the health effects of access to and use of online patients’ experiences about health and illness.

We articulated the key ideas to be explored in a multidisciplinary project meeting in which we developed our initial matrix.

Step 2: Search for Evidence

Exploratory background reading gave us “a feel” for the literature based on our own and colleagues’ bibliographic databases (concurrent with step 1a and 1b).

A wide-ranging search (with assistance from a librarian at the Oxford Knowledge Centre) sought to identify any studies that had tested the effects of exposure to online patients’ experiences (PEx) or that described theories or ideas about the potential effects of exposure to online patients’ experiences.

Both of us scanned all resulting titles and abstracts and after discussion chose potentially promising papers that could inform our thinking.

We sought more papers and books by “snowballing” from reference lists as promising ideas emerged.

Our final search for additional studies came when we had nearly completed our review or when we came across them in the course of our professional lives, for example, through discussions and seminars.

Step 3: Appraise Studies and Extract Data

-

At least one of us read full papers. Although we used no formal quality appraisal tools, we considered papers in relation to their

Relevance: Does the research address the topic and enable us to add to, adapt, or amend the initial matrix developed in step 1c?

Rigor: Does the research support the conclusions drawn from it by the researchers or the reviewers?

Both of us identified papers containing important ideas, explained them, and discussed their relevance during a period of intensive working together.

We added categories and specific instances to the initial matrix, which became our main data extraction framework.

Step 4: Synthesize Evidence

We developed our initial “map” or overview in a tabular form, identifying potential effects of access to and use of personal experiences of health and illness on the Internet, the potential negatives relating to that, and potential mechanisms through which each effect might work.

A constant comparison between reading and the working table identified the point at which no new ideas were emerging and we were confident that we had achieved “saturation.”

We drew up a glossary of terms defining, recording, and explaining key concepts; our understanding of them; and their application in this overview.

Step 5: Disseminate and Evaluate

We presented and discussed the table and glossary at a full team meeting and made some modifications and clarifications regarding how the table should be presented.

We discussed the table in a workshop with 30 members of a health service user panel, who suggested the emphasis and importance of topics.

A final search and discussions at a conference identified the importance of visual as well as written and read presentations of experiences.

We identified and described seven domains.

Source: Adapted from Pawson et al. 2005.

Service User Panel

To check our interpretation of the literature, we convened a user panel. The thirty lay participants were recruited through an invitation from Britain's Oxfordshire Primary Care Trust sent to a list of people who had previously agreed to help with our research. We selected the respondents by means of a questionnaire to ensure that the panel would be representative of a cross section of the community (gender, age, occupation, and ethnic group) and would be composed of those who had used the Internet for heath information in a variety of ways (websites, forums, blogs) and for a variety of health conditions (either for themselves or on behalf of family and friends). We first showed examples of health information with and without the inclusion of “personal experiences of health and illness.” The panel was divided into four groups, each with a rapporteur, and asked to think about how people might be positively and negatively affected by experiential information. The rapporteurs delivered the feedback to the whole group. In a final plenary session, we summarized the results of the conceptual review and discussed how they compared with the results of the group discussions. A final questionnaire asked participants what, in their view, were the most important ways in which experiences might affect people, both positively and negatively, from both the perspective of someone with a condition and that of a caregiver of someone with a condition. A report was circulated and feedback was sought.

Final Review and Revision

In our final search for relevant papers and discussions of the findings at a specialists’ workshop at a Health Informatics conference, we identified the importance of the visual presentations of online patients’ experience. We had not identified this topic in our previous reading but realizing its importance we now included it in our matrix. Finally, we agreed on the seven “domains” of our conceptual map of the potential health effects of online patients’ experience.

The Potential Health Effects of Seeing and Sharing Experiences Online

We discuss the role of online PEx with regard to the seven domains of (1) finding information, (2) feeling supported, (3) maintaining relationships with others, (4) experiencing health services, (5) learning to relate the story, (6) visualizing disease, and (7) affecting behavior. For each of these we considered the potential for both positive and negative effects.

Finding Information

Other people's experiences of illness can provide information that is valued in its own right (“forewarned is forearmed”). Such information can help allay fears, boost confidence (Lowe et al. 2009), and suggest or confirm one's own and doctors’ diagnoses by comparing symptoms and their effects with one's own experiences and knowledge (Armstrong and Powell 2009). Similarly, other people's accounts of a range of different treatments and outcomes can make information more relevant (Broemer 2004; Sillence et al. 2007), provide contextual information about causes and consequences, and help people understand what may happen (Lowe et al. 2009; Rothman and Kiviniemi 1999). Hearing about how others have coped may change one's orientation to the illness (Zufferey and Schulz 2009) and offer a framework for managing the uncertainties. Simple, practical tips on how to manage problems encountered in everyday life, coping strategies that others use, and advice based on what has worked for others are highly valued for their pragmatism (Sandaunet 2008; van Uden-Kraan et al. 2008) and because they are easy to understand (Steffen 1997).

In making decisions, people draw on many different sources of information and discuss using their own and others’ experiences as well as more traditional “factual” information for decisions (France et al. 2011), and they often say that they prefer not to base their health decisions solely on other people's experiences (Entwistle et al. 2011). However, hearing about other people's decisions can help them recognize that a decision must be made (e.g., about a treatment), define what the range of options might be, and clarify the alternatives (e.g., in relation to treatment, lifestyle, and attitude) (Bruce et al. 2005; Entwistle et al. 2011). Hearing about other people's experiences can help one to appraise options in light of the potential outcomes, so that decisions are tempered (Bruce et al. 2005) and might result in less regret because the content contains social and emotional information not usually available elsewhere (Lowe et al. 2009; Sharf 1997). Learning how other people reached their decisions, the consequences of those decisions, and their reflections on what happened as a result can help people evaluate their own past decisions as well as prepare for new ones (Entwistle et al. 2011; France et al. 2011).

Learning through other people's accounts of their experiences can be memorable because they are vivid (Etchegary et al. 2008; Taylor and Thompson 1982), but if the experiences presented are not typical (Entwistle et al. 2011), are inaccurate and biased, or are populated with the experiences of unusual people, or if the sites are sponsored by vested interests or open to commercial exploitation (Entwistle et al. 2011), the information may be distorted, perhaps leading to worse decisions if people are unaware (Leydon et al. 2000; Winterbottom et al. 2008). Our user group emphasized that the Internet's unregulated nature means that all sources of information might be seen as having equivalent status, regardless of their trustworthiness. Descriptions of negative or dramatic outcomes might mean that more numerous but unremarkable experiences remain unwritten or unnoticed. The difficulty of providing “balanced” information has been previously addressed (Entwistle 2007), but no clear solutions are yet available. Conflicting information from people with different experiences and “information overload” can cause confusion (including false reassurance) and anxiety, undermining otherwise good, instinctive decision making, although accessing information through the Internet may allow the information flow to be controlled (Lowe et al. 2009). People rarely present themselves as naive in their evaluations of any type of information, including those based on personal experience (Entwistle et al. 2011), but they do express concerns about others who may be more vulnerable to being misled. Questions remain about how much information one needs about an online peer in order to judge whether that person's experiences are trustworthy and likely to be applicable to oneself (Entwistle et al. 2011).

Feeling Supported

Illness very often brings a sense of isolation and of dislocation from the past (Williams 1984) and from the future (Bury 1982). Having an illness, facing a health issue, or being a family caregiver can challenge one's personal identity, and some people may feel embarrassed or even stigmatized by their condition. Knowing that others are tackling similar problems and learning how they deal with difficult issues can reduce these feelings of isolation, bringing a sense of belonging to a group and reassurance that one's experiences and reactions are “normal” (Harvey et al. 2007).

People who have joined an online peer-to-peer group may also benefit from feeling that they are connected by helping and supporting others (Adair et al. 2006; Gillett 2003). Online contacts can provide a safe environment for “emotional labor” (Bar-Lev 2008; Drentea and Moren-Cross 2005). Hearing about others’ experiences can induce feelings of compassion, so that one becomes less self-absorbed and gains a better perspective (Radley 1999). In their study of participation in online support groups, van Uden-Kraan and colleagues (2008) describe “emotional empowerment” as the process through which information is exchanged, emotional support is encountered, and recognition is gained through sharing experiences. Cohen (2004) calls this “emotional support” and suggests that it can make people simply feel better. Our user panel considered this process important, saying that it meant that you knew you “were not alone” because hearing about other people's experiences gave you a sense of “being supported.”

For people who have rare conditions, who are undergoing unusual treatments, or who are geographically isolated, the Internet may be their only source of this type of support and so be especially important (Armstrong and Powell 2009; Coulson, Buchanan, and Aubeeluck 2007). While it is common for people to describe being relieved to discover that there are others like them, dealing with similar issues, we wonder whether some may find this discovery an unwelcome challenge to a cherished view of themselves as special and unique.

Knowing that others have coped with illness can bring hope and reassurance concerning what may happen (Powell and Clarke 2006) and greater feelings of control and confidence that one can manage the situation (Adair et al. 2006), succeed (Buchanan and Coulson 2007), and cope with emotions through “emotion-focused coping” (Carlick and Biley 2004; Moos and Schaefer 1984).

In contrast, depending on their content, others’ experiences may arouse feelings of anxiety and confusion and can lead to unrealistic expectations, false hopes, or even despair, fear, guilt, anger, and inadequacy if others seem to be managing better. Patients’ feelings of despair at their own condition may become worse if they find out that peers have fared badly (Hinton, Kurinczuk, and Ziebland 2010). Internet-based support groups are sometimes dominated by a single viewpoint. Consequently, how one responds to other people's experiences depends greatly on one's mood at the time of the encounter and, if it goes badly, can reinforce one's vulnerability or feelings of inferiority.

Maintaining Relationships with Others

The Internet raises the possibility of having a distinct set of “online” and “off-line” relationships that can be particularly helpful when it is hard to maintain both an illness identity and an everyday identity. Online and off-line relationships need not, of course, be mutually exclusive, and many people keep in touch with friends via the Internet, and people who meet on the Internet can become real-life friends (proximity and willingness to eschew anonymity permitting) (e.g., see Chapple and Ziebland 2011). There are, however, big differences in the way that people communicate and establish relationships online. Apart from interactions in face-to-face support groups, finding out about the intimate health experiences of a new acquaintance is not a conventional route to getting to know someone in the off-line world. In an online forum, though, the usual requirement for conversational give-and-take need not apply: while a person may choose to write in extensive detail about his experiences, his audience can quickly browse through the account, break off at any point, or go back and review a section in more detail. Needless to say, such actions might be difficult to achieve in the real world without causing offense.

Learning about how others cope may help patients become socialized into a new role (e.g., as a patient or the spouse or parent of a patient) or forge a sense of identity in which a new diagnosis is integrated but may not be dominant. Finding that other people are facing similar problems may help one feel more “normal” and confident in managing one's health condition in other contexts, including family, work, relationships, and travel. Online support may even help sustain “real-world” relationships by providing another sounding board and emotional outlet for health concerns.

Paradoxically, isolation in the real world could be increased for people who feel that only those who have been through the same thing can understand them. Our user panel endorsed the idea that overreliance on “virtual support” can lead to wasted time browsing and posting on the web, preventing people from benefiting from social contact in their own locality. Hinton, Kurinczuk, and Ziebland (2010), writing about the use of online infertility support groups, drew attention to the possibility that web support could increase real-world isolation by reinforcing the notion that only those who have dealt with infertility themselves could possibly understand what it is like. A related idea, drawing on the work of Nicholas Negroponte (1995), is that by enabling people to refine and personalize all the information they receive (characterized as “The Daily Me”), they will rarely be exposed to any ideas that challenge their own. In this way the Internet could reinforce entrenched interests and misunderstandings. Learning how others deal with similar situations could shake confidence if people get the impression that their own ways of coping are less than optimal. Online accounts of people's anxieties and negative experiences could contribute to gloom and apprehension about what might happen. Without “upward comparisons” exemplified by others’ experiences of positive outcomes of a particular treatment or disease, people may feel increasingly distressed (Salzer et al. 2010). In addition, people who deal with things in other ways (e.g., those who have different values or have made different decisions) may question their own perspective or develop a sense of shame or stigma.

Experiencing Health Services

Finding out about other people's experiences of care can affect how people navigate health services. In market-oriented health systems or those that encourage patients to make choices about health care, feedback and commentary about other people's experiences of a care provider can often be found either on “reputation” sites designed to present public ratings or on patients’ chat rooms, forums, or social networking sites (see figure 1). Such information can contribute to decisions about which clinic to attend, which professionals to consult, or which treatment to request or avoid (Bruce et al. 2005; Sharf 1997).

Health consultations may be more efficient and patient centered if patients pick up useful ideas about the questions to ask, the best terms to use, and the symptoms or side effects to mention to their doctor (Caiata-Zufferey et al. 2010). Learning through other people's experiences may sometimes prevent unnecessary consultations; other people's descriptions of their own symptoms and consultations may reassure the “worried well” that they do not have the health problem they feared. People often look online to “follow up” on the advice given by health professionals or to seek validation for their own interpretations or feelings (Fredriksen, Moland, and Sundby 2008; Ziebland 2004;Ziebland et al. 2004). Responses may spur them to seek a second opinion or further clarification from their health care team (Pitts 2004).

Some patients contribute to improving services by posting their own comments and suggestions on feedback websites—which other patients, as well as managers and clinicians, use. This may help raise and address patients’ safety issues (Ricketts et al. 2010). At a macro level, by finding out how stigmatized conditions affect others or through restricted access to care and support, patients and the public may become more aware of inequalities and injustices or even become active in fostering changes in social attitudes or a more equitable provision of care (Dumit 2005). Online sharing of health (and health service) experiences can also stimulate advocacy and campaigns. In some cases it has been used to challenge not only the provision of services but the very parameters of what counts as an illness. This is particularly true for contested illnesses such as fibromyalgia and contested treatments such as vascular surgery for multiple sclerosis (Qiu 2010). Patients who compare what “counts” as an illness or a recognized treatment in different health systems will find ample examples of inconsistency, which they could use to fuel campaigns for either better evidence or more treatment options. While there are clearly several potential benefits for the way that people use health services and influence the development of care services (Wicks et al. 2010), clinical relationships may be strained if unrealistic expectations are raised or if alarming stories from other patients damage people's confidence in professionals and adherence to treatment. Those who take the time to provide feedback about their own experiences may feel frustrated and angry if this does not lead to improvements. Finding out about other people's experiences of poor care could be discouraging and increase people's anxiety about treatment in situations in which they have little choice or control. Conversely, they may learn that those who can pay, who have different health insurance, or who live in a country or state with another health system may seem to have benefited from different treatment options.

Another concern is that people could use the information they gain from others to manipulate the consultation, perhaps by exaggerating symptoms that they have learned will prompt clinicians to react in preferred ways. People could also become worried about their health by overidentifying with other people's experiences. This could lead to an overuse of health services, which our public panel referred to as “hypochondria heaven” for anxious patients.

Learning to Tell the Story

From childhood onward, stories provide a powerful, palatable, and memorable way of learning about the world (Bettelheim 1976). An engaging narrative can immerse the audience in the account and thereby transfer information in a particularly effective manner (de Wit, Das, and Vet 2008; Green and Brock 2000). When a story is well told and encountered at an opportune moment, it can reassure and ground the reader or listener. It can also help her make sense of her own situation by suggesting a practical and emotional frame for her response (Sandaunet 2008; Steffen 1997; van Uden-Kraan et al. 2008). We can see stories as a conduit for memorable and meaningful information and support.

Another relatively neglected aspect of stories, which we believe is important and distinct, concerns the very language, including the terms of reference and the figures of speech, that is used to construct an account. Hearing how others describe what has happened to them (as well as what has happened) adds to the richness of the vocabulary and can help construct our own account. While it is well understood that we learn through stories, the effect of hearing about other people's experiences on our ability to relate our own narrative is less well understood. The consequences of gaining an enriched and more powerful vocabulary, and this is distinct from the concept of health literacy (Nutbeam 2000), being able to tell their story well may help people develop an appropriate professional interest by giving a concise and relevant account in a clinical setting, help them explain salient points to professionals (Zufferey and Schulz 2009), and elicit understanding, support, and affirmation from friends, family, and wider audiences via the media and web blogs. We therefore see “learning to tell the story” as distinct from other aspects of the exchange of information and support because it focuses on the “how” rather than the “what” of the accounts that we are able to relate.

Frank (1995) and Pennebaker and Seagal (1999) suggested that even the very process of constructing a coherent story may help the healing process. Narrative construction (and reconstruction) may also help people make sense of what has happened to them and thus support their emotional recovery (Carlick and Biley 2004). The Internet allows those who want to share their stories with others to do so by adding a posting on a forum or chat room or perhaps setting up a site or blog of their own. Such sharing can feel empowering, especially if it attracts many followers or elicits approving commentary (Gillett 2003).

The question of verification cannot be ignored: how can we know whether accounts of people's health experiences are true? “Telling” or “spinning” stories is sometimes used as a synonym for telling lies, but Bury (2001) recommends our viewing people's accounts of their illness as “factions,” a meld of facts and fiction that weave interpretation and presentation into the account of what actually happened. As Entwistle and colleagues (2011) observed, people rarely present themselves as naive users of any information, yet we know relatively little about the effects (which could include incoherence and confusion) of exposure to numerous, and sometimes conflicting, accounts of health experiences on the web. Schwartz (2004) proposes that far from helping, a plethora of options may prevent one from being able to make (and live with) a choice. Those who post their own stories online may be harmed if their account is misappropriated, criticized, ridiculed, or even just corrected for facts. A mental health service user on our panel pointed out that a person posting a story when he or she is in the “wrong” frame of mind may cause regret. Internet posts can expose people to “flaming” criticism from others. Yet if no one comments on a heartfelt posting, the writer may feel even more isolated and ignored precisely because the potential audience was so vast. It may also be intimidating for some people to have very articulate people tell their story.

Visualizing Disease

The progress of a disease or of a recovery can be powerfully communicated through a series of static images or video recordings. Many health-related websites include images; even some that were originally intended to be based on text now link to video clips on sites such as YouTube. The incorporation of photographs and videos on health websites has been treated mainly as a design issue rather than considered in terms of the potential consequences for the way that people deal with their health problems. Williams and Cameron (2009) argued that images—in a variety of forms—are increasingly used in health care communication and can be powerful ways of communicating important messages. We suggest that the Internet is inherently visual and that the ability to post and access images of people dealing with health issues may be another important, albeit rarely explored, feature of health experiences and the Internet.

How do people use images of patients’ experiences online? Dermatological conditions are undeniably visual; photographs can help people compare and evaluate the effects of different treatments “with their own eyes.” Hardey (2011) reviewed video postings of eczema on YouTube and found more than one thousand clips, some of which had more than 2 million viewers. Some types of behavior change are documented online through repeated images. Weight loss blogs, for example, often include a visual chronicle (a series of before, during, and after shots) of a person's changing body shape. Sometimes these blogs feature a weekly picture of feet standing on a set of bathroom scales, adding evidence to the bloggers’ claims about their progress (Oostveen 2011). There also is evidence that adding imagery to text-based website information about the risk of cardiovascular disease can work better than text alone in increasing the perception of risk and motivating protective behavior (Lee et al. 2011).

Among the thousands of YouTube films of people with different health conditions, some capture a single moment; some record progress by following treatment; and some are undoubtedly positioned to promote a particular treatment (although the presentation may or may not make this explicit). Like stories, imagery can be powerful and memorable; like stories, this has both positive and negative consequences. Illness can dramatically change a person's appearance. People with serious progressive conditions, such as ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) or MND (motor neuron disease) may choose to avoid looking at images of other people whose appearance may grimly foreshadow their own future (Mazanderani, Powell, and Locock 2011).

Affecting Behavior

People's stories and experiences have become part of the standard content of the numerous websites that encourage changing health behavior. Indeed, advertising has long recognized the persuasive power of testimonials. The field of health education and health promotion was quick to see the potential of the Internet to deliver efficient, tailored advice (Cline and Haynes 2000) to help people lose weight, get more exercise, give up smoking, practice safe sex (Rothman et al. 1999), tackle depression, and control diabetes or high blood pressure. Some behavior change sites have evident commercial backing, and others are funded through government or health insurance and promoted in self-management programs. Testimonials and stories may be used to advertise a particular product, but they also may be intended as illustrations or for general encouragement and inspiration. One weight loss site put it as follows: “It is always inspiring to hear weight loss stories from other people as it makes you stop and think how you might change your life for the better by using some of their examples and applying them to your own life” (http://www.weightlosstips.co.uk/a-weight-loss-story-that-inspired-a-whole-family/#more-2026).

In her study of weight loss bloggers, Oostveen (2011) suggests that through public blogging, people may feel accountable to an audience, that by being aware that their progress is being watched, they may feel motivated to adhere to their program. Reflecting on what they have posted may make people feel proud and in control, or embarrassed and regretful.

For some health behaviors, such as cigarette smoking, people acknowledge that health professionals now are unlikely ever to have been smokers themselves, so advice from those who have “been there” may have greater weight (through empathy and resonance) with those trying to make changes. Hearing about how others deal with a problem or a concern can also build confidence and self-efficacy (Buchanan and Coulson 2007).

Narratives or stories hold people's attention by melding imagery and feeling. De Wit, Das, and Vet (2008) studied the effect of statistical and narrative evidence on the perceived threat of Hepatitis B infection among men who have sex with men. They found that the intention to be vaccinated was higher among those who were presented with a personal narrative, and they believe that this is because narratives are less susceptible to the defensive processing through which people distance themselves from health education messages. Evidence is increasing that hearing other patients’ stories can affect health behaviors. For example, a study of African Americans showed that the use of culturally appropriate DVDs of patients’ narratives of managing hypertension improved blood pressure control (Houston et al. 2011; Kimberley and Green 2011).

In their study in South Wales, Davison, Davey Smith, and Frankel (1991) noted that people use a “lay epidemiology” (e.g., the popular image of an elderly relative who lived into his nineties despite smoking and drinking) to resist acknowledging that health education messages apply to them. This tendency to distance oneself from an unwelcome message (e.g., about susceptibility to a smoking-related disease or a sexually transmitted infection) may be strongly challenged by a resonant account from someone else who had held the same (shown to be mistaken) belief that they would not be affected.

In some circumstances, hearing about other people's experiences may reinforce unhealthy behaviors. Some sites contain messages that contradict or challenge medical advice and suggest or reinforce unhealthy behaviors. Several studies have examined the content of online pro-anorexia support groups (Gavin, Rodham, and Poyer 2008); people with diabetes can learn from forums about nonprescribed ways to use (misuse) their insulin for weight loss. Some online forums promote unsafe sexual practices and even provide advice on how to most effectively contract HIV. At the extreme end of harm, those who are inclined toward suicide can even find forums that offer advice (and possibly encouragement) about how to end their life.

Discussion

The profusion of patients’ experiences online has dramatically influenced the health information field. Health choices cannot be made without information (Ubel, Jepson, and Baron 2001), and the importance of Internet health information is not disputed. Yet our conceptual review demonstrates that the full gamut of effects (for both the “poster” and the “consumer”) of websites that cite patients’ experiences go far beyond the provision of “information” or “support,” at least as they are conventionally conceived. Our conceptual review shows that we are unlikely to identify the effects of exposure to online PEx simply by measuring outcomes such as knowledge acquisition, coping, or decisional quality alone.

The Internet changes constantly and defies conventional mapping. We focused on the potential health effects of exposure to other people's experiences on the Internet rather than describing the domains of the moving target itself. Future empirical work will no doubt help refine these domains, but because they are grounded in a diverse literature rich in theory, we trust that they will have some longevity.

We were careful to consider the potential for harm as well as benefit, trying to avoid the temptation to be either pessimists or optimists (Blumenthal 2002). Online PEx may help people make better health care choices and alert them to health issues, improve their health literacy and understanding of susceptibility to illness, compare their situation with others, improve their own illness narration, access more appropriate services, and develop better relationships. But we cannot assume that the effects of exposure to online PEx are always benign. They may raise anxiety. They may be disadvantageous if they feature only a small number of unrepresentative patients’ stories. A single story with strong emotional content can distort decisions (Leydon et al. 2000; Winterbottom et al. 2008). Overengagement with online communities can be detrimental to life “off-line.” The powerful and memorable delivery of a personal experience could be used for a deliberately misleading or exploitative message. The benefits and disadvantages are unlikely to be evenly distributed across socioeconomic, age, and gender groups, yet little is known about these patterns, and as the digital ground shifts again, new applications may encourage new types of use, and users.

Guided by realist review methods (Pawson et al. 2005), we considered the processes through which PEx may operate. The literature suggests that the processes may differ depending on, for example, whether people are reading about others’ experiences or writing about their own. Those who help create health content may be participating in a different way from those who consume rather than post their own contributions, yet the widespread use of social media and blogs is already blurring these boundaries. Some of the outcomes or consequences (e.g., the ability to make sense of what has happened and construct a coherent account) may be similar, whether one has learned from other people's stories or from constructing a coherent account of one's own.

Our review sheds some light on the features that make first hand accounts compelling and the processes through which they operate. While very little empirical work in this area exists to date, a British National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)–funded program (iPEx) is examining the role of online PEx. The iPEx program (which includes qualitative interviews, an online ethnography, Internet café experiments, and a randomized controlled trial) is designed to help us understand the role of online PEx and provide guidelines for websites and health interventions that incorporate patients’ experiences (for more information on the program, see ipexonline.org). As part of this program we are developing and piloting an outcome measure (the “e-health impact questionnaire”), which incorporates the domains identified in this review, to assess the impact of health websites, including those that feature patients’ experiences.

Health policymakers, clinicians, and the voluntary sector need evidence regarding the role and limitations of online PEx in the broad canvas of people's experiences of health and illness. The Internet is increasingly used as a vehicle for transparency, safety, and choice in health services. Some health systems (such as the NHS) recognize that patients and health professionals share their experiences online, commenting on their experiences with services, illnesses, and outcomes of treatment, and comparing their accounts with other people's as part of the vanguard in new, co-created approaches to quality improvement and cultural change in response to illness (NHS Future Forum report on Information 2012). The challenges could be more dramatic than policymakers anticipate: by gathering and comparing their experiences online, patients and their families may conclude that they need radically different services. The Internet is a fertile environment for advocacy and pressure groups and may, by its very nature, attract those who would be reluctant to join a conventional voluntary association. While this aspect of Internet use fell outside the scope of our review, we suggest that role of the Internet in supporting and encouraging public involvement and advocacy (and the consequences of any shift in focus) may be a fruitful area for further research.

The extent to which patients and members of the public have turned to other people's experiences on the Internet has provoked both surprise and, in some quarters, concern. The value of first-person accounts, the appeal and memorability of stories, and the need to make contact with peers all strongly suggest that reading and hearing others’ accounts of personal experiences of health and illnesss will remain a key feature of e-health. But the act of participating in the creation of health content (e.g., through blogging and social networking) is also affecting patients’ experiences and has implications for our understanding of patients’ role in health care management and information. This review presents a new focus for exploring health and illness in a connected world.

Acknowledgments

The iPEx program presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) in England under its Programme Grants for Applied Research funding scheme (RP-PG-0608-10147). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors, representing iPEx, and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health. The iPEx study group is composed of the University of Oxford (Sue Ziebland, Louise Locock, Andrew Farmer, Crispin Jenkinson, Rafael Perera, Ruth Sanders, Angela Martin, Laura Griffith, Susan Kirkpatrick, Nicolas Hughes, and Laura Kelly), the University of Warwick (John Powell and Fadhila Mazanderani), the University of Northumbria (Pamela Briggs, Elizabeth Sillence, and Claire Hardy), the University of Sheffield (Peter Harris), the University of Glasgow (Sally Wyke), the Department of Health (Robert Gann), the Oxfordshire Primary Care Trust (Sula Wiltshire), and the user adviser (Margaret Booth).

We are grateful to Susannah Fox, two anonymous reviewers, and the late Michael Hardey and Dr. Braden O’Neill for their suggestions; to our program manager Angela Martin, who has skillfully kept us on track; and to Nia Roberts at the Oxford Knowledge Centre and Abi Eccles for their help with the review and preparation of this article. We are also grateful to Robert Gann for his insights into Britain's health policy.

References

- Adair CE, Marcoux G, Williams A, Reimer M. The Internet as a Source of Data to Support the Development of a Quality-of-Life Measure for Eating Disorders. Qualitative Health Research. 2006;16(4):538–46. doi: 10.1177/1049732305285850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong N, Powell J. Patient Perspectives on Health Advice Posted on Internet Discussion Boards: A Qualitative Study. Health Expectations. 2009;12(3):313–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2009.00543.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Lev S. ‘‘We Are Here to Give You Emotional Support’’: Performing Emotions in an Online HIV/AIDS Support Group. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18(4):509–21. doi: 10.1177/1049732307311680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettelheim B. The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales. New York: Knopf; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal D. Doctors in a Wired World: Can Professionalism Survive Connectivity? The Milbank Quarterly. 2002;80(3):525–46. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal D. Expecting the Unexpected: Health Information Technology and Medical Professionalism. In: Rothman, Blumenthal, editors. Medical Professionalism in the New Information Age. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press; 2010. pp. 8–23. [Google Scholar]

- Broemer P. Ease of Imagination Moderates Reactions to Differently Framed Health Messages. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2004;34:103–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce B, Lorig K, Laurent D, Ritter P. The Impact of a Moderated E-mail Discussion Group on Use of Complementary and Alternative Therapies in Subjects with Recurrent Back Pain. Patient Education and Counseling. 2005;58:305–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan H, Coulson NS. Accessing Dental Anxiety Online Support Groups: An Exploratory Qualitative Study of Motives and Experiences. Patient Education and Counseling. 2007;66(3):263–69. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bury M. Chronic Illness as Biographical Disruption. Sociology of Health & Illness. 1982;4(2):167–82. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.ep11339939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bury M. Illness Narratives: Fact or Fiction? Sociology of Health & Illness. 2001;23(3):263–85. [Google Scholar]

- Caiata-Zufferey M, Abraham A, Sommerhalder K, Schulz PJ. Online Health Information Seeking in the Context of the Medical Consultation in Switzerland. Qualitative Health Research. 2010;20(8):1050–61. doi: 10.1177/1049732310368404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlick A, Biley FC. Thoughts on the Therapeutic Use of Narrative in the Promotion of Coping in Cancer Care. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2004;13(4):308–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2004.00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapple A, Ziebland S. How the Internet Is Changing the Experience of Bereavement by Suicide: A Qualitative Study in the UK. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine. 2011;15(2):173–87. doi: 10.1177/1363459309360792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou W-YS, Hunt YM, Beckjord EB, Moser RP, Hesse BW. Social Media Use in the United States: Implications for Health Communication. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2009;11(4):e48. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline RJW, Haynes KM. Consumer Health Information Seeking on the Internet: The State of the Art. Health Education Research. 2000;16(6):671–92. doi: 10.1093/her/16.6.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. Social Relationships and Health. American Psychologist. 2004;59(8):676–84. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulson NS, Buchanan H, Aubeeluck A. Social Support in Cyberspace: A Content Analysis of Communication within a Huntington's Disease Online Support Group. Patient Education and Counseling. 2007;68(2):173–78. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison C, Smith G Davey, Frankel S. Lay Epidemiology and the Prevention Paradox: The Implications of Coronary Candidacy for Health Education. Sociology of Health & Illness. 1991;13:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- de Wit JBF, Das E, Vet R. What Works Best: Objective Statistics or a Personal Testimonial? An Assessment of the Persuasive Effects of Different Types of Message Evidence on Risk Perception. Health Psychology. 2008;27(1):110–15. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillard AJ, Fagerlin A, Cin SD, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Ubel PA. Narratives That Address Affective Forecasting Errors Reduce Perceived Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71(1):45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingwall R. Aspects of Illness. Farnham: Ashgate; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Drentea P, Moren-Cross JL. Social Capital and Social Support on the Web: The Case of an Internet Mother Site. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2005;27(7):920–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2005.00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumit J. Illnesses You Have to Fight to Get: Facts as Forces in Uncertain, Emergent Illnesses. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;62(3):577–90. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entwistle VA. Considering “Balance” in Information. Health Expectations. 2007;10(4):307–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2007.00469.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entwistle VA, France E, Wyke S, Jepson R, Hunt K, Ziebland S, Thompson A. How Information about Other People's Personal Experiences Can Help with Healthcare Decision Making: A Qualitative Study. Patient Education and Counseling. 2011;85(3):291–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.05.014. Available at http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0738399111002400 (accessed March 28, 2012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etchegary H, Potter B, Howley H, Cappelli M, Coyle D, Graham I, Walker M, Wilson B. The Influence of Experiential Knowledge on Prenatal Screening and Testing Decisions. Genetic Testing. 2008;12(1):115–24. doi: 10.1089/gte.2007.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox S. The Social Life of Health Information. Pew Internet and American Life. 2011 Available at http://www.pewInternet.org/Reports/2011/Social-Life-of-Health-Info/Summary-of-Findings.aspx (accessed March 28, 2012) [Google Scholar]

- France E, Wyke S, Ziebland S, Entwistle VA, Hunt K. How Personal Experiences Feature in Women's Accounts of Use of Information for Decisions about Antenatal Diagnostic Testing for Foetal Abnormality. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;72:755–62. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank AW. The Wounded Storyteller: Body, Illness, and Ethics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen EH, Moland KM, Sundby J. “Listen to Your Body”. A Qualitative Text Analysis of Internet Discussions Related to Pregnancy Health and Pelvic Girdle Pain in Pregnancy. Patient Education and Counseling. 2008;73(2):294–99. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel Y. The Voice of Experience and the Voice of the Expert—Can They Speak to Each Other? In: Hurwitz B, Greenhalgh T, Skultans V, editors. Narrative Research in Health and Illness. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2004. pp. 168–86. [Google Scholar]

- Gavin J, Rodham K, Poyer H. The Presentation of “Pro-Anorexia” in Online Group Interactions. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18(3):325–33. doi: 10.1177/1049732307311640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillett J. Media Activism and Internet Use by People with HIV/AIDS. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2003;25(6):608–24. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.00361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MC, Brock TC. The Role of Transportation in the Persuasiveness of Public Narratives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79(5):701–21. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.5.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T, Kristjansson E, Robinson V. Realist Review to Understand the Efficacy of School Feeding Programmes. BMJ. 2007;335:858–61. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39359.525174.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of Innovations in Service Organizations: Systematic Review and Recommendations. The Milbank Quarterly. 2004;82(4):581–629. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardey M. 2011. Personal communication.

- Harvey KJ, Brown B, Crawford P, Macfarlane A, MacPherson A. “Am I Normal?” Teenagers, Sexual Health and the Internet. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65(4):771–81. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton L, Kurinczuk JJ, Ziebland S. Infertility; Isolation and the Internet: A Qualitative Interview Study. Patient Education and Counseling. 2010;81(3):436–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston TK, Allison JJ, Sussman M, Horn W, Holt CL, Trobaugh J, Salas M, Pisu M, Cuffee YL, Larkin D, Person SD, Barton B, Kiefe CI, Hullett S. Culturally Appropriate Storytelling to Improve Blood Pressure: A Randomized Trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2011;154(2):77–84. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-2-201101180-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimberly RM, Green MJ. Storytelling A Novel Intervention for Hypertension. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2011;154(2):129–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-2-201101180-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TJ, Cameron LD, Wünsche B, Stevens C. A Randomized Trial of Computer-Based Communications Using Imagery and Text Information to Alter Representations of Heart Disease Risk and Motivate Protective Behaviour. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2011;16(1):72–91. doi: 10.1348/135910710X511709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal L, Brisette I, Leventhal H. The Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation of Health and Illness. In: Cameron L, Leventhal H, editors. The Self-Regulation of Health and Illness Behaviour. London: Routledge; 2003. pp. 42–65. [Google Scholar]

- Leydon GM, Moynihan C, Boulton M, Mossman J, Boudioni M, McPherson K. Cancer Patients’ Information Needs and Information Seeking Behaviour: In-Depth Interview Study. BMJ. 2000;320:909–13. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7239.909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe P, Powell J, Griffiths F, Thorogood M, Locock L. “Making It All Normal”: The Role of the Internet in Problematic Pregnancy. Qualitative Health Research. 2009;19(10):1476–84. doi: 10.1177/1049732309348368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazanderani F, Powell J, Locock L. 2011. Being Differently the Same in the Sharing of Health Experiences in Health Care. Paper presented at Online Patient Experience (PEx) and Its Role in e-Health, a workshop at the 25th Human Computer Interaction conference, Northumbria University, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, July 4–8.

- Mazzocato P, Savage C, Brommels M, Aronsson HK, Thor J. Lean Thinking in Healthcare: A Realist Review of the Literature. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2010;19:376–82. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.037986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Schaefer JA. The Crisis of Physical Illness: An Overview and Conceptual Approach. In: Moos RH, editor. Coping with Physical Illness: Volume 2. New York: Plenum Medical Books; 1984. pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Negroponte N. Being Digital. New York: Vintage Books; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- NHS (National Health Service) Operating Framework. 2011. Available at http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Managingyourorganisation/Financeandplanning/Planningframework/index.htm (accessed March 28, 2012)

- NHS (National Health Service) Future Forum Report on Information. 2012. Available at http://healthandcare.dh.gov.uk/forum-report/ (accessed March 28, 2012)

- Nutbeam D. Health Literacy as a Public Health Goal: A Challenge for Contemporary Health Education and Health Communication Strategies into the 21st Century. Health Promotion International. 2000;15(3):259–67. [Google Scholar]

- Oostveen A. 2011. The Internet as an Empowering Technology for Stigmatized Groups: A Case Study of Weight Loss Bloggers. Paper presented at the 25th BCS Conference on “Health, Wealth & Happiness.” Human Computer Interaction (HCI2011), Northumbria University, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, July 4–8.

- Pawson R. Evidence-Based Policy: A Realist Perspective. London: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, Walshe K. Realist Review: A New Method of Systematic Review Designed for Complex Policy Interventions. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy. 2005;10:21–34. doi: 10.1258/1355819054308530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Seagal JD. Forming a Story: The Health Benefits of Narratives. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1999;55(10):1243–54. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199910)55:10<1243::AID-JCLP6>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitts V. Illness and Internet Empowerment: Writing and Reading Breast Cancer in Cyberspace. Health. 2004;8(1):33–59. doi: 10.1177/1363459304038794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell J, Clarke A. Information in Mental Health: Qualitative Study of Mental Health Service Users. Health Expectations. 2006;9(4):359–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2006.00403.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preece J, Nonnecke B, Andrews D. The Top Five Reasons for Lurking: Improving Community Experiences for Everyone. Computers in Human Behavior. 2004;20(2):201–23. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J. Venous Abnormalities and Multiple Sclerosis: Another Breakthrough Claim? Lancet Neurology. 2010;9(5):464–65. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radley A. The Aesthetics of Illness: Narrative, Horror and the Sublime. Sociology of Health & Illness. 1999;21(6):778–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ricketts M, Shanteau J, McSpadden B, Fernandez-Medina KM. Using Stories to Battle Unintentional Injuries: Narratives in Safety and Health Communication. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70(9):1441–49. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman AJ, Kelly KM, Weinstein ND, O’Leary A. Increasing the Salience of Risky Sexual Behavior: Promoting HIV-Antibody Testing among Heterosexually Active Young Adults. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1999;29(3):531–51. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman AJ, Kiviniemi MT. Treating People with Information: An Analysis and Review of Approaches to Communicating Health Risk Information. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs. 1999;25:44–51. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzer MS, Palmer SC, Kaplan K, Brusilovskiy E, Ten Have T, Hampshire M, Metz J, Coyne JC. A Randomized, Controlled Study of Internet Peer-to-Peer Interactions among Women Newly Diagnosed with Breast Cancer. Psycho-oncology. 2010;19(4):441–46. doi: 10.1002/pon.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandaunet A. A Space for Suffering? Communicating Breast Cancer in an Online Self-Help Context. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18(12):1631–41. doi: 10.1177/1049732308327076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer R, Kuczynski K, Skinner D. Producing Genetic Knowledge and Citizenship through the Internet: Mothers, Pediatric Genetics, and Cybermedicine. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2008;30(1):145–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz B. The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less. New York: Ecco; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sharf BF. Communicating Breast Cancer Online: Support and Empowerment on the Internet. Women and Health. 1997;26(1):65–84. doi: 10.1300/J013v26n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillence E, Briggs P, Harris PR, Fishwick L. How Do Patients Evaluate and Make Use of Online Health Information? Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64:1853–62. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen V. Life Stories and Shared Experience. Social Science & Medicine. 1997;45(1):99–111. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00319-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Thompson SC. Stalking the Elusive “Vividness” Effect. Psychological Review. 1982;89:155–81. [Google Scholar]

- Ubel PA, Jepson C, Baron J. The Inclusion of Patient Testimonials in Decision Aids: Effects on Treatment Choices. Medical Decision Making. 2001;21(1):60–68. doi: 10.1177/0272989X0102100108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Uden-Kraan CF, Drossaert CHC, Taal E, Shaw BR, Seydel ER, van de Laar MAFJ. Empowering Processes and Outcomes of Participation in Online Support Groups for Patients with Breast Cancer, Arthritis, or Fibromyalgia. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18(3):405–17. doi: 10.1177/1049732307313429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassilev I, Rogers A, Sanders C, Kennedy A, Blickem C, Protheroe J, Bower P, Kirk S, Chew-Graham C, Morris R. Social Networks, Social Capital and Chronic Illness Self-Management: A Realist Review. Chronic Illness. 2011;7(1):60–86. doi: 10.1177/1742395310383338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicks P, Massagli M, Frost J, Brownstein C, Okun S, Vaughan T, Bradley R, Heywood J. Sharing Health Data for Better Outcomes on PatientsLikeMe. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2010;12(2):e19. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1549. Available at http://www.jmir.org/2010/2/e19/ (accessed March 28, 2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B, Cameron L. Images in Health Care: Potential and Problems. Journal of Health Services and Research Policy. 2009;14(4):251–54. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2009.008168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams G. The Genesis of Chronic Illness: Narrative Reconstruction. Sociology of Health & Illness. 1984;6(2):175–200. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.ep10778250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winterbottom A, Becker H, Conner M, Mooney A. Does Narrative Information Bias Individual's Decision Making? A Systematic Review. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67(12):2079–88. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Pawson R. Internet-Based Medical Education: A Realist Review of What Works, for Whom and in What Circumstances. BMC Medical Education. 2010;10(12) doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziebland S. The Importance of Being Expert: How Men and Women with Cancer Use the Internet. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;59:1783–93. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziebland S, Chapple A, Dumelow C, Evans J, Prinjha S, Rozmovits L. How the Internet Affects Patients’ Experience of Cancer: A Qualitative Study. BMJ. 2004;328:564–67. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7439.564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziebland S, Evans J, Toynbee P. Exceptionally Good? Positive Experiences of NHS Care and Treatment Surprises Lymphoma Patients: A Qualitative Interview Study. Health Expectations. 2011;14:21–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00609.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zufferey MC, Schulz PJ. Self-Management of Chronic Low Back Pain: An Exploration of the Impact of a Patient-Centered Website. Patient Education and Counseling. 2009;77(1):27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]