Abstract

Objective To determine the accuracy with which a single progesterone measurement in early pregnancy discriminates between viable and non-viable pregnancy.

Design Systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy studies.

Data sources Medline, Embase, CINAHL, Web of Science, ProQuest, Conference Proceedings Citation Index, and the Cochrane Library from inception until April 2012, plus reference lists of relevant studies.

Study selection Studies were selected on the basis of participants (women with spontaneous pregnancy of less than 14 weeks of gestation); test (single serum progesterone measurement); outcome (viable intrauterine pregnancy, miscarriage, or ectopic pregnancy) diagnosed on the basis of combinations of pregnancy test, ultrasound scan, laparoscopy, and histological examination; design (cohort studies of test accuracy); and sufficient data being reported.

Results 26 cohort studies, including 9436 pregnant women, were included, consisting of 7 studies in women with symptoms and inconclusive ultrasound assessment and 19 studies in women with symptoms alone. Among women with symptoms and inconclusive ultrasound assessments, the progesterone test (5 studies with 1998 participants and cut-off values from 3.2 to 6 ng/mL) predicted a non-viable pregnancy with pooled sensitivity of 74.6% (95% confidence interval 50.6% to 89.4%), specificity of 98.4% (90.9% to 99.7%), positive likelihood ratio of 45 (7.1 to 289), and negative likelihood ratio of 0.26 (0.12 to 0.57). The median prevalence of a non-viable pregnancy was 73.2%, and the probability of a non-viable pregnancy was raised to 99.2% if the progesterone was low. For women with symptoms alone, the progesterone test had a higher specificity when a threshold of 10 ng/mL was used (9 studies with 4689 participants) and predicted a non-viable pregnancy with pooled sensitivity of 66.5% (53.6% to 77.4%), specificity of 96.3% (91.1% to 98.5%), positive likelihood ratio of 18 (7.2 to 45), and negative likelihood ratio of 0.35 (0.24 to 0.50). The probability of a non-viable pregnancy was raised from 62.9% to 96.8%.

Conclusion A single progesterone measurement for women in early pregnancy presenting with bleeding or pain and inconclusive ultrasound assessments can rule out a viable pregnancy.

Introduction

Vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain are the most common causes of consultation in early pregnancy; 30% of women will experience pain or bleeding in their first trimester.1 These symptoms lead to anxiety and can be the first signs of a possible miscarriage or an ectopic pregnancy. Miscarriage occurs in 10-20% of all recognised pregnancies, and the prevalence of ectopic pregnancies in the United Kingdom is 1.6%, which is raised to 3% in women with symptoms.2 3 4 Most women seeking medical advice have a transvaginal ultrasound scan to confirm a viable pregnancy, a miscarriage, or an ectopic pregnancy. However, even with expert use of transvaginal ultrasound, confirming if a pregnancy is intrauterine or extrauterine may not be possible in 8-31% of cases at the first visit.5 An observational study of pregnancies with inconclusive ultrasound results has shown that 50% spontaneously resolve (decreasing concentrations of β human chorionic gonadotrophin (β-hCG)), 27% are subsequently diagnosed as viable, and 14% are diagnosed as ectopic pregnancies.6 The high incidence of miscarriages and ectopic pregnancies in women with inconclusive ultrasound results warrants further tests to reach a diagnosis. Measurement of serum β-hCG can be useful, but often more than one β-hCG measurements is needed to make a diagnosis.7

Serum progesterone has been proposed as a useful test to distinguish a viable pregnancy from a miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy.8 Low progesterone values are associated with miscarriages and ectopic pregnancies, both considered non-viable pregnancies, and high progesterone concentrations with viable pregnancies.8 Knowledge about the diagnostic accuracy of a single serum progesterone measurement to determine the viability of the pregnancy may accelerate diagnosis, avoiding further tests and unnecessary interventions, and improve outcomes. National recommendations refrain from defining how this test should be used in diagnostic algorithms.8 The reason for this is that clinical practice is informed by individual small studies with unstable inferences and conflicting results on the accuracy of a single serum progesterone measurement in determining the viability of the pregnancy.5 6 8 A meta-analysis in 1998 did not take into account the recent widespread use of transvaginal ultrasound, which may improve the accuracy of this test.9 The aim of our review was to evaluate the accuracy of a single progesterone measurement, by a meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy studies, to predict pregnancy outcome in women with pain or bleeding in early pregnancy with or without an inconclusive ultrasound diagnosis.

Methods

Literature search

We did a comprehensive literature search to identify studies with a population of women with spontaneous pregnancy of less than 14 weeks of gestation, in which the single serum progesterone measurement was used to predict the outcome of pregnancy (viable intrauterine pregnancy, miscarriage, or ectopic pregnancy). The databases searched included Medline, Embase, CINAHL, and the Cochrane Library from inception to April 2012. We searched Medline, Embase and CINAHL by a combination of the keywords for the test (progestor*) and outcomes of interest (“ectopic pregnancy”, “tubal pregnancy”, “viab* pregnancy”, “failing pregnancy”, “miscarr*”, and “abort*”) with their associated medical subject and Emtree headings. We searched the Cochrane Library with the keywords “progesterone” and “pregnancy”. We placed no filters or language restrictions to ensure maximal sensitivity of the searches. We also checked the reference sections of all selected articles for relevant papers.

Study selection

We selected the studies in two rounds: firstly, on title and abstract, independently by two reviewers (IDG and MA); secondly, on full text, also independently by two reviewers (JV and NM), against pre-specified criteria. We selected studies that assessed diagnostic accuracy or derived prediction rules. We excluded case-control studies, narrative reviews, letters, editorials, comments, and case series. We used systematic reviews and meta-analyses only as a source of references. Studies needed to include women with spontaneous early pregnancy to be eligible for the review. We excluded studies including women who had conceived after treatment to induce ovulation, who had had progesterone supplementation or in vitro fertilisation, as well as studies that included women above a gestational age of 14 weeks. The index test was a single measurement of serum progesterone. We excluded studies that did not report a cut-off value for progesterone but reported results only by high or low progesterone.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two reviewers (JV and NM) extracted data, and a third reviewer (IDG) checked the data. From the relevant articles, we extracted information on study design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, population (asymptomatic women/women with symptoms, women with inconclusive transvaginal ultrasound results), details of progesterone test (assay, cut-off value), details of other tests (β-hCG, transvaginal ultrasound), details about pregnancy outcomes (description, diagnostic methods), flow of patients, and two by two tables for pregnancy outcomes according to progesterone test. One reviewer (JV) assessed included studies for methodological quality, and two reviewers (MA and NM) checked them. We assessed the quality of studies by using an outlined component approach for diagnostic accuracy studies (QUADAS).10 The reference standard for our included studies was the pregnancy outcome as defined during follow-up in the original studies. For this reason, we omitted one item on the time period from index test to reference standard, as the reference standard diagnosis is normally reached within hours or days virtually eliminating possible delayed verification bias from all studies. We grouped studies according to whether women presented with pain or bleeding and inconclusive ultrasound examination or with symptoms alone.

Data synthesis and analysis

We plotted individual studies’ estimates of sensitivities and specificities on summary receiver operating characteristics space and forest plots for visual examination of heterogeneity. We used the SAS statistical package to meta-analyse a pair of sensitivity and specificity from each included study by using the hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristics approach.11 12 This approach estimates the position and shape of the summary receiver operating characteristics curve and takes into account both within and between study variations. Many studies reported progesterone concentrations in ng/mL, so we converted those in nmol/L to ng/mL. To generate a summary receiver operating characteristics curve using all available studies for each meta-analysis, where more than one cut-off value was reported in a study we chose the two by two table for the lowest cut-off value because lower cut-offs were more widely reported in included studies. When all the parameters of the hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristics model could not be estimated owing to a limited number of studies, we simplified it by assuming a symmetrical shape for the curve. We considered methods that allow joint synthesis of sensitivities and specificities at multiple thresholds, but none was appropriate because most studies reported sensitivity and specificity at a single threshold.13 14 15 For meta-analysis of studies that used the same or similar cut-off values, we used parameter estimates from the models to derive summary operating points (that is, summary sensitivities and specificities), with 95% confidence regions, and summary likelihood ratios. We calculated post-test probabilities by using the summary likelihood ratios and the median prevalence values with their ranges as the pre-test probabilities.

Results

Literature identification and study quality

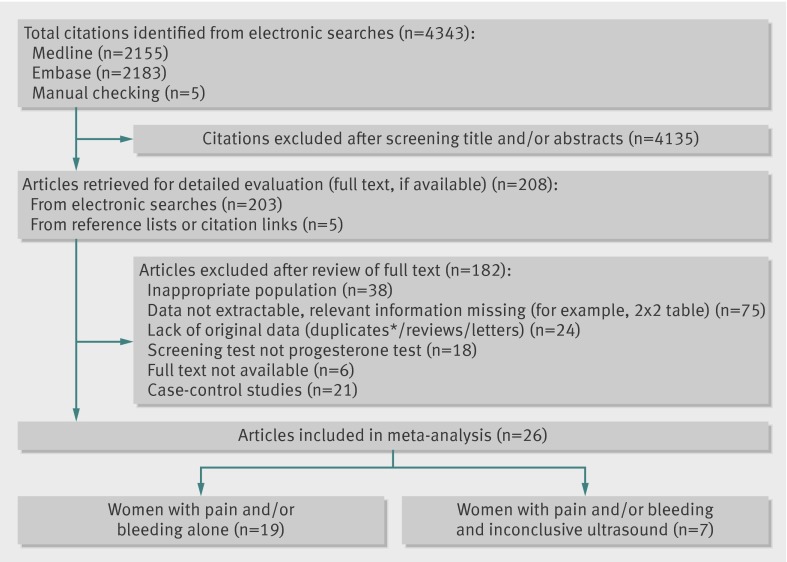

Figure 1 shows the literature search and study selection process. We identified 4338 citations; we obtained 203 articles for full text evaluation and identified another five studies through manual checking of reference lists. We contacted 20 authors of 25 different studies for additional data. Five authors replied to our emails, but only one of these authors could provide us with additional information. Overall, 26 studies were eligible for inclusion, with a total of 9436 participants. Nineteen studies included women with pain or bleeding alone,16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 and seven studies included women with pain or bleeding and inconclusive ultrasound diagnosis.34 35 36 37 38 39 40 The supplementary (web extra) table shows the characteristics of the included studies.

Fig 1 Flow chart of study selection. *Three studies by Stovall et al reported same patients as study by McCord et al. Study by McCord was included, because it reported on more participants

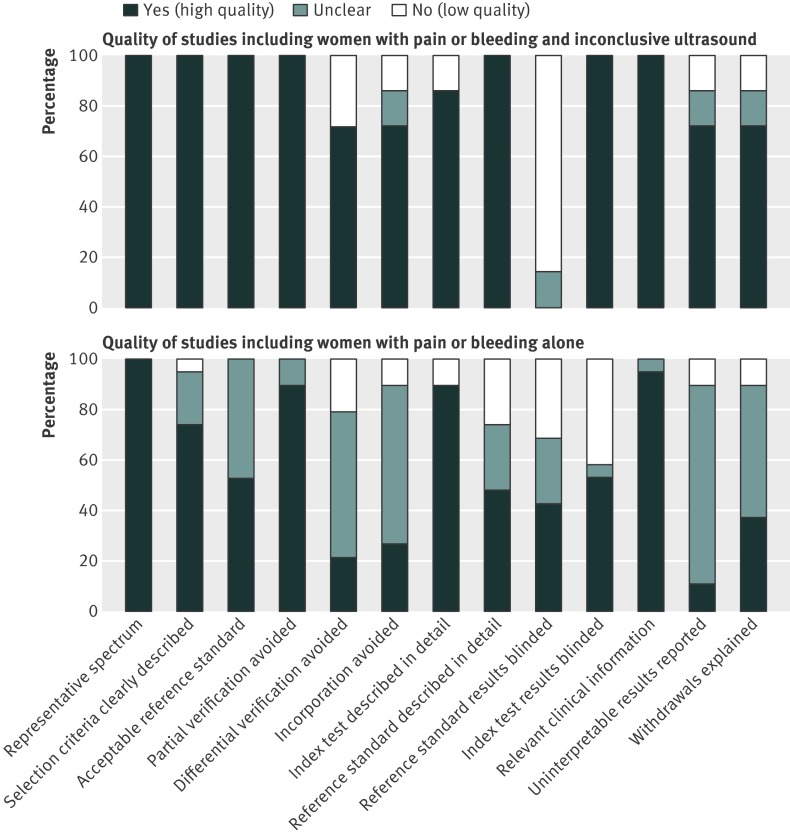

Figure 2 shows the results of the quality assessment. Most of the studies of women with pain or bleeding with inconclusive ultrasound examination were of high quality; all seven studies included participants representative of the population of interest and contained adequate details about the index and reference standard tests. For pregnancies that resolved spontaneously, two studies did not investigate further to differentiate between a miscarriage and an ectopic pregnancy.34 35 None of these seven studies adopted blinding for the reference standard results. The studies including women with pain or bleeding alone (without ultrasound scan) were of intermediate quality, and potential biases were difficult to exclude because of poor reporting of the primary studies. Progesterone assays used in the primary studies were found to be comparable and all were included. The insufficient reporting along with the limited number of studies prevented us from evaluating the effect of potential sources of heterogeneity.

Fig 2 Cumulative bar plot of methodological quality items across studies including women with pain or bleeding and inconclusive ultrasound (top) and women with pain or bleeding alone (bottom)

Progesterone test in women with pain or bleeding and inconclusive ultrasound

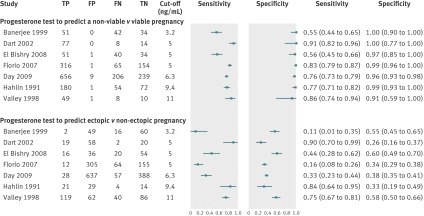

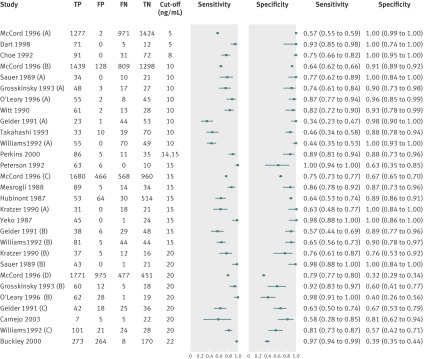

Seven prospective cohort studies, including 2379 women, in women with pain or bleeding and inconclusive ultrasound diagnosis evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of the single serum progesterone measurement to predict the possibility of a viable pregnancy, miscarriage, or ectopic pregnancy. The thresholds of progesterone used ranged from 3.2 to 11 ng/mL (10 to 35 nmol/L); the most commonly used threshold was 5 ng/mL (16 nmol/L), which was used in three studies.34 37 38 Figures 3 and 4 show the estimated sensitivities and specificities when using the single progesterone measurement test for differentiating between viable and non-viable pregnancies, which includes both miscarriages and ectopic pregnancies. After meta-analysis of five studies (1998 participants) with similar cut-off values (3.2 to 6 ng/mL),34 35 36 37 38 we found that a single progesterone measurement predicted a non-viable pregnancy with pooled sensitivity of 74.6% (95% confidence interval 50.6% to 89.4%), specificity of 98.4% (90.9% to 99.7%), positive likelihood ratio of 45 (7.1 to 289), and negative likelihood ratio of 0.26 (0.12 to 0.57). In the studies included in this meta-analysis, the median prevalence of a non-viable pregnancy was 73.2%. However, if progesterone was lower than the cut-off value (3.2 to 6 ng/mL), the probability of a non-viable pregnancy was 99.2% compared with 44.8% if progesterone was higher. The progesterone test had a very poor predictive accuracy for diagnosing ectopic pregnancy, for which a low progesterone concentration did not rule in or out an ectopic pregnancy (table).

Fig 3 Forest plot of study results of progesterone test in women with pain or bleeding and inconclusive ultrasound assessment grouped according to outcome. FN=false negative; FP=false positive; TN=true negative; TP=true positive

Fig 4 Summary receiver operating characteristics plot of progesterone test at cut-off values between 3.2 and 6.4 ng/mL used to identify non-viable pregnancies in women with pain or bleeding and inconclusive ultrasound assessment (black dot=summary sensitivity and specificity; dotted region around it=95% confidence region)

Summary estimates for each pregnancy outcome at different thresholds in women with pain and/or bleeding with inconclusive ultrasound diagnosis and for women with pain and/or bleeding alone

| Studies (No of participants) | Cut-off (ng/mL) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Positive likelihood ratio (95% CI) | Negative likelihood ratio (95% CI) | Pre-test and post-test probabilities (ranges)* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before test (%) | After test if positive (%) | After test if negative (%) | |||||||

| Women with pain and/or bleeding with inconclusive ultrasound diagnosis | |||||||||

| Progesterone test to predict ectopic v non-ectopic pregnancy: | |||||||||

| 5 studies (1998 women) | <3.2-6 | 36.5 (12 to 70.6) | 41.7 (16 to 72.9) | 0.63 (0.29 to 1.35) | 1.52 (0.99 to 2.36) | 14.2 (7.7-28.6) | 9.44 (5-20.2) | 20.1 (11.3-37.8) | |

| Progesterone test to predict non-viable v viable pregnancy: | |||||||||

| 5 studies (1998 women) | <3.2-6 | 74.6 (50.6 to 89.4) | 98.4 (90.9 to 99.7) | 45.4 (7.13 to 288.9) | 0.26 (0.12 to 0.57) | 73.2 (71.1-85.9) | 99.2 (99.1-99.6) | 44.8 (39-61.3) | |

| Women with pain and/or bleeding alone | |||||||||

| Progesterone test to predict non-viable v viable pregnancy: | |||||||||

| 9 studies (4689 women) | <10 | 66.5 (53.6 to 77.4) | 96.3 (91.1 to 98.5) | 18 (7.19 to 44.8) | 0.35 (0.24 to 0.50) | 62.9 (47.4-71.8) | 96.8 (94.2-97.9) | 37.2 (24-47.1) | |

| 9 studies (5128 women) | <15 | 83.3 (66.6 to 92.6) | 87.5 (78.5 to 93.1) | 6.66 (3.81 to 11.7) | 0.19 (0.09 to 0.40) | 70 (12.6-79.7) | 93.9 (49-96.3) | 30.7 (2.7-42.7) | |

| 8 studies (4348 women) | <20 | 85.7 (72.3 to 93.2) | 66.6 (47.0 to 81.8) | 2.56 (1.46 to 4.50) | 0.22 (0.10 to 0.47) | 61.2 (30.8-71.8) | 80.2 (53.3-86.7) | 25.8 (8.9-35.9) | |

*Pre-test probabilities are median prevalence values with corresponding ranges.

Progesterone test in women with pain or bleeding alone

Nineteen cohort studies, including 7057 women, evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of the single serum progesterone measurement to predict pregnancy outcomes in women with pain or bleeding alone. The table shows the pooled diagnostic accuracy estimates for identifying women with non-viable pregnancies with the most commonly reported thresholds, and figure 5 shows the estimates separately for each study according to available cut-off values. For women with symptoms alone, the progesterone test had a higher specificity using a threshold of 10 ng/mL (nine studies with 4689 participants18 20 21 24 26 29 30 31 32), rather than higher thresholds at 15 and 20 ng/mL, and predicted a non-viable pregnancy with pooled sensitivity of 66.5% (53.6% to 77.4%), specificity of 96.3% (91.1% to 98.5%), positive likelihood ratio of 18 (7.2 to 45), and negative likelihood ratio of 0.35 (0.24 to 0.50). The median prevalence of a non-viable pregnancy in the studies included in this analysis was 62.9%; this was raised to 96.8% if the progesterone was lower than 10 ng/mL compared with a 37.2% probability if the progesterone was higher.

Fig 5 Forest plot of study results of progesterone test at various cut-off values used to identify non-viable pregnancies in women with pain or bleeding alone. Study names with suffixes A to D reported accuracy of progesterone at more than one cut-off. FN=false negative; FP=false positive; TN=true negative; TP=true positive

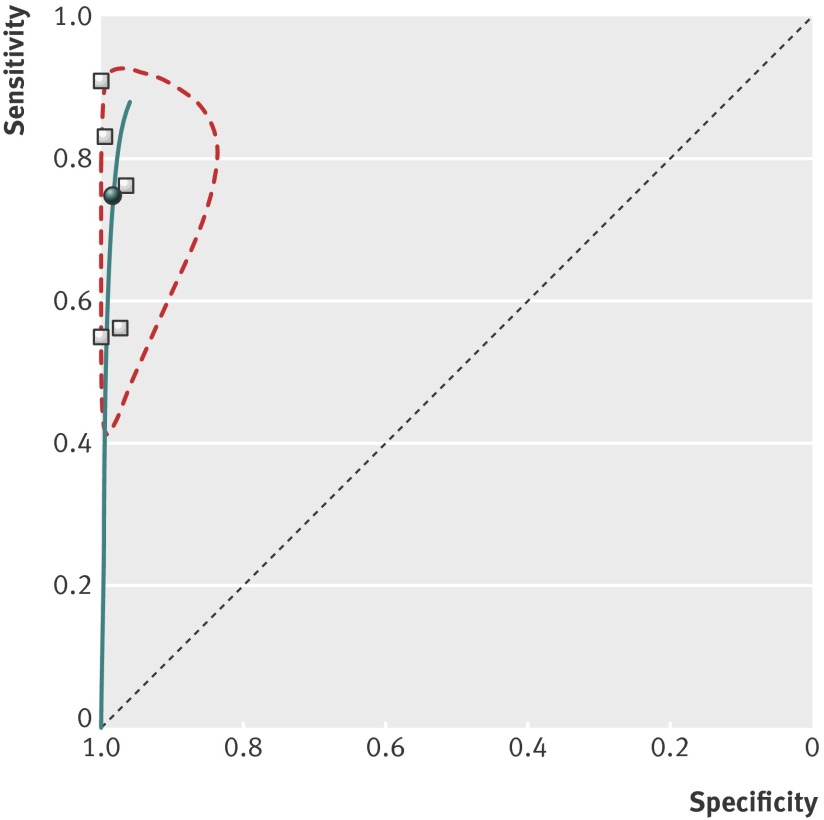

Figure 6 shows summary receiver operating characteristics curves for commonly reported cut-off values and a curve of all studies at a selected threshold for each study. This shows that for higher thresholds the specificity is lower with generally higher sensitivity. Specifically, with a threshold of 15 ng/mL (nine studies with 5128 participants20 22 23 24 25 27 28 31 32) this test predicted a non-viable pregnancy with pooled sensitivity of 83.3% (66.6% to 92.6%), specificity of 87.5% (78.5% to 93.1%), positive likelihood ratio of 6.7 (3.8 to 12), and negative likelihood ratio of 0.35 (0.09 to 0.5); with a threshold of 20 ng/mL (eight studies with 4348 participants17 20 21 23 24 26 29 31) it predicted a non-viable pregnancy with pooled sensitivity of 85.7% (72.3% to 93.2%), specificity of 66.6% (47% to 91.8%), positive likelihood ratio of 2.6 (1.5 to 4.5), and negative likelihood ratio of 0.22 (0.1 to 0.47).

Fig 6 Summary receiver operating characteristics plot of progesterone test at different cut-off values used to identify non-viable pregnancies in women with pain or bleeding alone

In the McCord 1996 study,24 2248 of 3674 participants had non-viable pregnancies. This constitutes 78% of the number of participants with non-viable pregnancies in the analyses at 10 and 15 ng/mL cut-off values and 84% of the non-viable pregnancies in the analysis at 20 ng/mL. In a sensitivity analysis, the effect of removal of the study on the summary estimates at each cut-off value was negligible.

Discussion

The meta-analysis shows that a single progesterone measurement is useful in predicting non-viable pregnancies in women with pain or bleeding when an ultrasound investigation proves to be inconclusive. A low concentration of progesterone (less than 3.2 to 6 ng/mL) in these women ruled out a viable pregnancy in 99.2% of women. However, the test cannot distinguish women with an ectopic pregnancy from those with an early normal pregnancy or a miscarriage and should not be used for this purpose. For women with symptoms but without an ultrasound investigation, it may also be a useful test but is less accurate for ruling out women with a normal viable pregnancy.

Strengths and weaknesses of study

The strengths of our study are that we did an extensive systematic search of electronic databases without language restrictions, which would have captured all existing good quality studies. The high number of included studies in our meta-analyses strengthens the power of our conclusions and enabled us to explore the diagnostic accuracy of the progesterone test for multiple cut-off values. The methodological quality of the studies included in the review was satisfactory, but some limitations of doing pragmatic studies in this clinical setting were highlighted. The classification of women according to their pregnancy outcome, which was used as the reference standard, is a problem for miscarriages and ectopic pregnancies as in many cases a firm diagnosis cannot be made. Even though the studies did not adopt a blinded assessment of the reference standard, which in our case was the final diagnosis, this is unlikely to have introduced bias when it comes to distinguishing between viable and non-viable pregnancies, as viable pregnancies lead to a live birth and most of the studies had long enough follow-up to verify this outcome. The primary studies did not adjust for known confounding factors, such as the gestational age, but this could be explained by the high prevalence of non-viable pregnancies, in which changes in progesterone concentrations are poorly described compared with viable pregnancies.41 Assessment of quality was also hampered by unclear reporting in some studies. Poor reporting occurred in most of the studies in the description of the reference standard, reporting of uninterpretable results, and explanation of withdrawals from the study.

Many studies, especially for women with pain or bleeding who did not have an ultrasound assessment, had very different prevalences of pregnancy outcomes compared with more recent studies; this reflects the different clinical settings and populations that this test evaluated. Despite the heterogeneity, all studies reported good predictive ability of the progesterone test to differentiate viable pregnancies from miscarriages and ectopic pregnancies, especially in women with pain or bleeding with inconclusive ultrasound results, in whom the chance of miscarriages or ectopic pregnancies is high. The test, therefore, has generalisability and may be applicable in clinical practice in a variety of settings.

Strengths and weaknesses in relation to other studies

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists’ guideline for early pregnancy suggests that the single serum progesterone measurement is a useful test to predict pregnancy outcome.8 It states that a threshold for serum progesterone of 20 nmol/L (about 6.2 ng/mL) has a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 94% to predict a non-viable pregnancy in women with symptoms and inconclusive ultrasound but acknowledges that no discriminatory value for this test exists to confidently rule in or out a normal viable pregnancy. This conflicts with the findings in this meta-analysis, which is based also on the studies cited by this guideline.24 34 39 The existing evidence shows that specificity is higher (98.4%) and sensitivity lower (74.6%) using a cut-off value around 5 ng/mL. The findings of our study support those of a meta-analysis by Mol et al in 1998,9 which focused on a single progesterone measurement to predict ectopic pregnancy. The results of that study showed that a single progesterone measurement was useful for predicting the viability of a pregnancy but not for discriminating between an ectopic and a non-ectopic pregnancy, and this agrees with our results. The clinically most relevant question of accuracy of progesterone in women with inconclusive ultrasound investigations, however, is not covered by Mol et al.

Meaning of study: implications for clinicians

The outcome of a pregnancy in women with pain or bleeding in early pregnancy cannot be determined clinically alone after inconclusive ultrasound assessments. In such situations, a chance exists of a normal viable pregnancy that may be too early to be detected on ultrasound; our review estimates the median prevalence of this to be 26.8%. Most women, however, have a non-viable pregnancy in the form of a miscarriage or an ectopic pregnancy. Serial serum β-hCG measurements are needed to differentiate between these outcomes in most diagnostic algorithms.7 Suboptimal rise in β-hCG (<66%) after 48 hours indicates that miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy is a possibility. However, a rise in suboptimal β-hCG may occur even in viable pregnancies in up to 19% of cases.7 Therefore, the β-hCG test should be complemented by another test to increase its diagnostic accuracy. Serum progesterone measurement is a non-invasive test that can be done at the same time that blood is drawn for β-hCG measurements. It is already in use in many early pregnancy assessment units, although the accuracy of the progesterone test and the interpretation of the measured concentrations are uncertain. This test could be added to the existing algorithms for evaluation of early pregnancy, and its effect should be evaluated through a randomised trial comparing algorithms with and without serum progesterone.42 Our review suggests that a single serum progesterone measurement is more accurate when it follows an inconclusive ultrasound assessment; in women with pain or bleeding who did not have an ultrasound scan, the progesterone test was less accurate in predicting viability of a pregnancy.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis found that a single progesterone measurement for women in early pregnancy presenting with bleeding or pain and inconclusive ultrasound assessments can rule out a viable pregnancy.

What is already known on this topic

Vaginal bleeding or pain occurs in 30% of women in early pregnancy; investigations are aimed at differentiating a viable intrauterine pregnancy from a non-viable one

A single progesterone measurement in early pregnancy has been suggested to be a useful test for discriminating between viable and non-viable pregnancies

However, clinical practice is informed by individual small studies with conflicting results on the test’s accuracy in determining the viability of a pregnancy

What this study adds

A single progesterone measurement can discriminate between a viable and a non-viable pregnancy

A single low progesterone measurement for women in early pregnancy presenting with bleeding or pain and inconclusive ultrasound results can rule out a viable pregnancy

Contributors: IDG and MA-A had the idea for the systematic review, did the literature search, and screened eligible abstracts and databases. JV and NM did the full manuscript evaluation and study selection. JV, IDG, NMvM, HH, and MA-A extracted the data. YT and JJD analysed the data. IDG, JV, NMvM, and YT interpreted the data. JV and NMvM assessed the quality of the studies. JV drafted the first version of the manuscript, and IDG drafted all the subsequent versions and the final manuscript. BWJM, JJD, and AC gave critical input. AC is the guarantor.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from institution for the submitted work; no relationships with any institution that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; and no non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not needed.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2012;345:e6077

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Characteristics of included studies

References

- 1.Everett C. Incidence and outcome of bleeding before the 20th week of pregnancy: prospective study from general practice. BMJ 1997;315:32-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alberman E. Spontaneous abortion: epidemiology. In: Stabile S, Grudzinskas JG, Chard T, eds. Spontaneous abortion: diagnosis and treatment. Springer-Verlag, 1992:9-20.

- 3.Hospital Episode Statistics. NHS Maternity Statistics, England 2009-10. Figure 1: Total deliveries, miscarriages and ectopic pregnancies per 100 deliveries, 1997-98 to 2009-10 (available at www.hesonline.nhs.uk/Ease/servlet/ContentServer?siteID=1937&categoryID=1804).

- 4.Shillito J, Walker JJ. Early pregnancy assessment units. Br J Hosp Med 1997;58:505-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Condous G, Okaro E, Bourne T. The conservative management of early pregnancy complications: a review of the literature. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2003;22:420-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banerjee S, Aslam N, Zosmer N, Woelfer B, Jurkovic D. The expectant management of women with early pregnancy of unknown location. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1999;14:231-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kadar N, Caldwell BV, Romero R. A method of screening for ectopic pregnancy and its indications. Obstet Gynecol 1981;58:162-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hinshaw K, Fayyad A, Munjuluri P. The management of early pregnancy loss. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2006. (Green-top guideline No 25.)

- 9.Mol BW, Lijmer JG, Ankum WM, van der Veen F, Bossuyt PM. The accuracy of single serum progesterone measurement in the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Hum Reprod 1998;13:3220-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whiting P, Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, Bossuyt PM, Kleijnen J. The development of QUADAS: a tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2003;3:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macaskill P. Empirical Bayes estimates generated in a hierarchical summary ROC analysis agreed closely with those of a full Bayesian analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 2004;57:925-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rutter CM, Gatsonis CA. A hierarchical regression approach to meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy evaluations. Stat Med 2001;20:2865-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamza TH, Arends LR, van Houwelingen HC, Stijnen T. Multivariate random effects meta-analysis of diagnostic tests with multiple thresholds. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009;10:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kester AD, Buntinx F. Meta-analysis of ROC curves. Med Decis Making 2000;20:430-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dukic V, Gatsonis C. Meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy assessment studies with varying number of thresholds. Biometrics 2003;59:936-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buckley RG, King KJ, Disney JD, Riffenburgh RH, Gorman JD, Klausen JH. Serum progesterone testing to predict ectopic pregnancy in symptomatic first-trimester patients. Ann Emerg Med 2000;36:95-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Camejo MI, Proverbio F, Febres F, Casart YC. Bioactive to immunoreactive ratio of circulating human chorionic gonadotropin as possible evaluation for the prognosis of threatened abortion. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2003;109:181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choe JK, Check JH, Nowroozi K, Benveniste R, Barnea ER. Serum progesterone and 17-hydroxyprogesterone in the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancies and the value of progesterone replacement in intrauterine pregnancies when serum progesterone levels are low. Gynecol Obstet Invest 1992;34:133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dart R, Dart L, Segal M, Page C, Brancato J. The ability of a single serum progesterone value to identify abnormal pregnancies in patients with beta-human chorionic gonadotropin values less than 1,000 mIU/mL. Acad Emerg Med 1998;5:304-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gelder MS, Boots LR, Younger JB. Use of a single random serum progesterone value as a diagnostic aid for ectopic pregnancy. Fertil Steril 1991;55:497-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grosskinsky CM, Hage ML, Tyrey L, Christakos AC, Hughes CL. hCG, progesterone, alpha-fetoprotein, and estradiol in the identification of ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 1993;81:705-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hubinont CJ, Thomas C, Schwers JF. Luteal function in ectopic pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1987;156:669-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kratzer PG, Taylor RN. Corpus luteum function in early pregnancies is primarily determined by the rate of change of human chorionic gonadotropin levels. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1990;163:1497-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCord ML, Muram D, Buster JE, Arheart KL, Stovall TG, Carson SA. Single serum progesterone as a screen for ectopic pregnancy: exchanging specificity and sensitivity to obtain optimal test performance. Fertil Steril 1996;66:513-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mesrogli M, Degenhardt F, Maas DH, Klaus I, Busche M, Schneider J. [Tubal pregnancies: early pregnancy factor, progesterone, beta-HCG and vaginal sonography as differential diagnostic parameters] [German]. Z Geburtshilfe Perinatol 1988;192:130-2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Leary P, Nichols C, Feddema P, Lam T, Aitken M. Serum progesterone and human chorionic gonadotrophin measurements in the evaluation of ectopic pregnancy. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 1996;36:319-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perkins SL, Al-Ramahi M, Claman P. Comparison of serum progesterone as an indicator of pregnancy nonviability in spontaneously pregnant emergency room and infertility clinic patient populations. Fertil Steril 2000;73:499-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peterson CM, Kreger D, Delgado P, Hung TT. Laboratory and clinical comparison of a rapid versus a classic progesterone radioimmunoassay for use in determining abnormal and ectopic pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992;166:562-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sauer MV, Sinosich MJ, Yeko TR, Vermesh M, Buster JE, Simon JA. Predictive value of a single serum pregnancy associated plasma protein-A or progesterone in the diagnosis of abnormal pregnancy. Hum Reprod 1989;4:331-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takahashi K, Yamane Y, Kitao M. Prognostic value of serum CA 125 and serum progesterone in threatened abortion. J Obstet Gynaecol 1992;12:147-9. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams RS, Gaines IL, Fossum GT. Progesterone in diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. J Fla Med Assoc 1992;79:237-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Witt BR, Wolf GC, Wainwright CJ, Johnston PD, Thorneycroft IH. Relaxin, CA-125, progesterone, estradiol, Schwangerschaft protein, and human chorionic gonadotropin as predictors of outcome in threatened and nonthreatened pregnancies. Fertil Steril 1990;53:1029-36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yeko TR, Rodi IA, Gorrill MJ, Buster JE, Hughes LH, Sauer MV. Timely diagnosis of early ectopic pregnancy using a single blood progesterone measurement. Fertil Steril 1987;48:1048-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Banerjee S, Aslam N, Zosmer N, Woelfer B, Jurkovic D. The expectant management of women with early pregnancy of unknown location. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1999;14:231-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dart R, Ramanujam P, Dart L. Progesterone as a predictor of ectopic pregnancy when the ultrasound is indeterminate. Am J Emerg Med 2002;20:575-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Day A, Sawyer E, Mavrelos D, Tailor A, Helmy S, Jurkovic D. Use of serum progesterone measurements to reduce need for follow-up in women with pregnancies of unknown location. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2009;33:704-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.El Bishry G, Ganta S. The role of single serum progesterone measurement in conjunction with beta hCG in the management of suspected ectopic pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol 2008;28:413-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Florio P, Severi FM, Bocchi C, Luisi S, Mazzini M, Danero S, et al. Single serum activin a testing to predict ectopic pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:1748-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hahlin M, Sjoblom P, Lindblom B. Combined use of progesterone and human chorionic gonadotropin determinations for differential diagnosis of very early pregnancy. Fertil Steril 1991;55:492-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Valley VT, Mateer JR, Aiman EJ, Thoma ME, Phelan MB. Serum progesterone and endovaginal sonography by emergency physicians in the evaluation of ectopic pregnancy. Acad Emerg Med 1998;5:309-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mol BW, Hajenius PJ, Engelsbel S, Ankum WM, Hemrika DJ, Bossuyt PMM, et al. Are gestational age and endometrial thickness alternatives for serum hCG measurement in the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy? Fertil Steril. 1999;72:643-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bossuyt PM, Lijmer JG, Mol BW. Randomised comparisons of medical tests: sometimes invalid, not always efficient. Lancet 2000;356:1844-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Characteristics of included studies