To the Editor:

We recently published a series of cases in which jejunal tube extensions via a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) resulted in delayed small-bowel perforations.1 At the time of publication, we concluded that the perforations occurred secondary to repetitive trauma as the distal tip was propelled by peristalsis against a relatively fixed portion of bowel. This notion was supported by reports of the flexible tubes changing consistency in the bowel lumen, becoming stiff, and allowing the distal tip to cause pressure necrosis.2-5 Additionally, we proposed that reduced bowel integrity in the critically ill and scoring of the mucosa by stiff guidewires may contribute to mucosal necrosis. We now write to highlight a remarkable intermediate finding we believe would have led to the same devastating small bowel perforation if undetected.

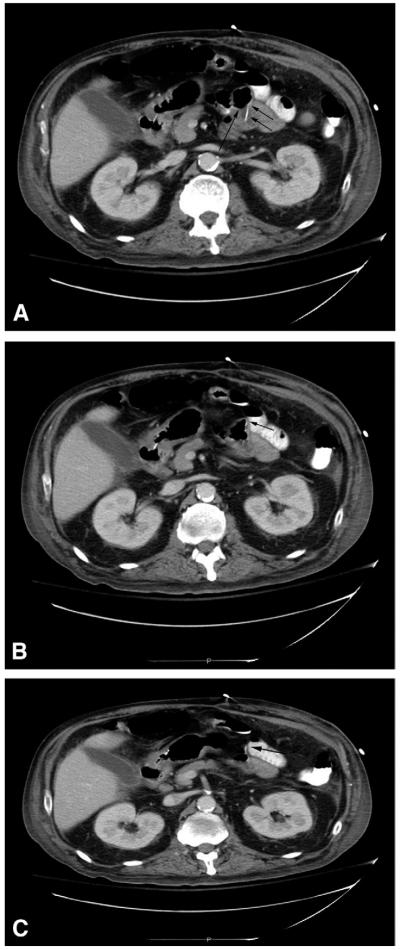

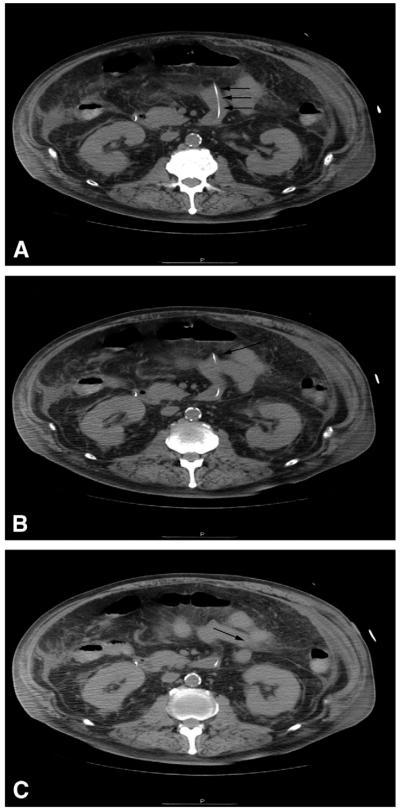

A 54-year-old man was admitted with complicated pancreatitis including numerous peripancreatic fluid collections and abscesses. Subsequent clinical deterioration required mechanical ventilation and supplemental nutrition. He underwent PEG placement and endoscopic jejunal tube extension. Six days thereafter, the patient underwent a CT scan to evaluate fevers and leukocytosis and to rule out new fluid collections. The CT scan revealed the tip of the jejunal tube producing significant tenting of the small bowel wall and an enlarged fluid collection (Fig. 1). Two days later, the patient underwent CT-guided drain placement, demonstrating an unchanged location of the jejunal tip (Fig. 2). The jejunal tube was withdrawn under fluoroscopic guidance to prevent pressure necrosis and perforation.

Figure 1.

Initial CT scan with jejunal tube extension in progressively distal small bowel. A, Jejunal tube (double arrows) traveling anteriorly with gas in the lumen (long arrow). B, Distal tip of the jejunal tube (arrow) tenting the bowel wall mucosa anteriorly. C, The bowel traverses to the patient’s left, the distal tip terminating at the turn (arrow), causing mucosal tenting.

Figure 2.

Subsequent CT scan with jejunal tube extension in progressively distal small bowel. A, Jejunal tube (arrows) traveling anteriorly in the small bowel. B. Distal tip of the jejunal tube (arrow) terminating at a bend of the small bowel, producing mucosal tenting. C, The bowel traverses toward the patient’s left (arrow) without the jejunal tube.

Our previously reported cases of jejunal tube extensions perforated at 11, 12, and 19 days after jejunal tube placement, reaffirming a semi-acute to chronic process rather than procedure-related trauma. This current case, although not a true perforation, had an obvious mechanism to result in perforation and would be the first to occur at our institution following endoscopic placement. Although previous speculation focused on wire damage during radiologic placement, we now recognize that any tube’s distal tip terminating in a relatively fixed region of the small bowel may result in pressure necrosis independent of peristalsis.

Contributor Information

Laura H. Rosenberger, Department of Surgery.

David M. Mauro, Department of Radiology.

Robert G. Sawyer, Department of Surgery University of Virginia Health System Charlottesville, Virginia, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rosenberger LH, Newhook T, Mauro DM, et al. Jejunal tube extensions via percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and delayed small-bowel perforations: a case series. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:683–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegle RL, Rabinowitz JG, Sarasohn C. Intestinal perforations secondary to nasojejunal feeding tubes. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1976;126:1229–32. doi: 10.2214/ajr.126.6.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chou TD, Ue ST, Lee CH, et al. Duodenal perforation as a complication of routine endoscopic nasoenteral feeding tube placement. Burns. 1999;25:86–7. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(98)00143-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tong Z, Li W, Wang X, et al. Duodenal perforation due to a kink in a nasojejunal feeding tube in a patient with severe acute pancreatitis: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2010;4:162. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-4-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flores JC, Lopez-Herce J, Sola I, et al. Duodenal perforation caused by a transpyloric tube in a critically ill infant. Nutrition. 2006;22:209–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2005.08.005. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2012.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]