Abstract

A new multicolor fluorescence in situ hybridization (mFISH) probe set is presented, and its possible applications are highlighted in 25 clinical cases. The so-called heterochromatin-M-FISH (HCM-FISH) probe set enables a one-step characterization of the large heterochromatic regions within the human genome. HCM-FISH closes a gap in the now available mFISH probe sets, as those do not normally cover the acrocentric short arms; the large pericentric regions of chromosomes 1, 9, and 16; as well as the band Yq12. Still, these regions can be involved in different kinds of chromosomal rearrangements such as translocations, insertions, inversions, amplifications, and marker chromosome formations. Here, examples are given for all these kinds of chromosomal aberrations, detected as constitutional rearrangements in clinical cases. Application perspectives of the probe set in tumors as well as in evolutionary cytogenetic studies are given.

Keywords: multicolor fluorescence in situ hybridization (mFISH), heterochromatin-M-FISH (HCM-FISH) probe set, heteromorphism, small supernumerary marker chromosome (sSMC), insertion, translocation

A detailed characterization of chromosomal rearrangements detected in routine banding cytogenetics can nowadays be done easily by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and/or array-comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) (Manolakos et al. 2010; Weimer et al. 2011). While in aCGH, a higher resolution may be achieved, FISH still has several advantages over the array-based approaches (Manolakos et al. 2010). FISH allows, for example, the analysis of balanced rearrangements, of chromosomal aberrations present only in low mosaic levels, and of the large heterochromatic regions of the human genome. The acrocentric short arms; the centric and the large pericentric regions of chromosomes 1, 9, and 16; as well as the band Yq12 cannot be analyzed by aCGH.

A multitude of multicolor FISH (mFISH) probe sets have been developed in the last decades (Liehr 2012a). They were implemented for use in one experiment: 1) all 24 human whole chromosome painting probes (multiplex FISH = M-FISH [Speicher et al. 1996]; spectral karyotyping = SKY [Schröck et al. 1996]) or 2) all centromeric probes (centromere-specific M-FISH = cenM-FISH [Nietzel et al. 2001]). Also, 3) various FISH banding approaches (Liehr et al. 2002a) were introduced as well as 4) combinations of centromeric with locus-specific and/or partial chromosome painting probes (e.g., subcentromere-specific M-FISH = subcenM-FISH [Liehr et al. 2006]). These probe sets are highly suited to characterize simple and complex chromosomal aberrations (approaches 1 and 3) or small supernumerary marker chromosomes (sSMC) (Liehr et al. 2004, 2006) (approaches 2 and 4). Recently, even a probe set was introduced to substantiate indirectly epigenetic changes (parental origin determination FISH = POD-FISH [Weise et al. 2008]).

Here, we present a new mFISH probe set specifically directed against the large heterochromatic regions within the human genome. This so-called heterochromatin-M-FISH (HCM-FISH) set was successfully established and applied already in 30 cases, where its application saved sample material and time. We present 25 representative cases studied by HCM-FISH and discuss the possible applications of this new probe set.

Materials and Methods

HCM-FISH Probe Set

The HCM-FISH probe set (Fig. 1) is based on eight glass-needle microdissection (midi)–derived and one P1 artificial chromosome (PAC) probe (RP5–1174A5 = dj1174A5); the latter was kindly provided by Dr. M. Rocchi (Bari, Italy). The latter probe is specific for the nucleolus organizer region (NOR), which contains several tandem copies of ribosomal RNA genes and in humans is clustered on the short arms of chromosomes 13, 14, 15, 21, and 22; that is, the acrocentric chromosomes (Trifonov et al. 2003). Midi was done as previously reported (Liehr et al. 2002b). Midi probes for the regions 1q12, 9q12, 15p12~11.2 (i.e., a β-satellite–specific probe), 16q11.2, 19p12~19q12, and Yq12 were established for this probe set, while those probes for 9p12/9q13 (midi 36) (Starke et al. 2002) and for all acrocentric short arms (midi 54) were as previously reported (Mrasek et al. 2003).

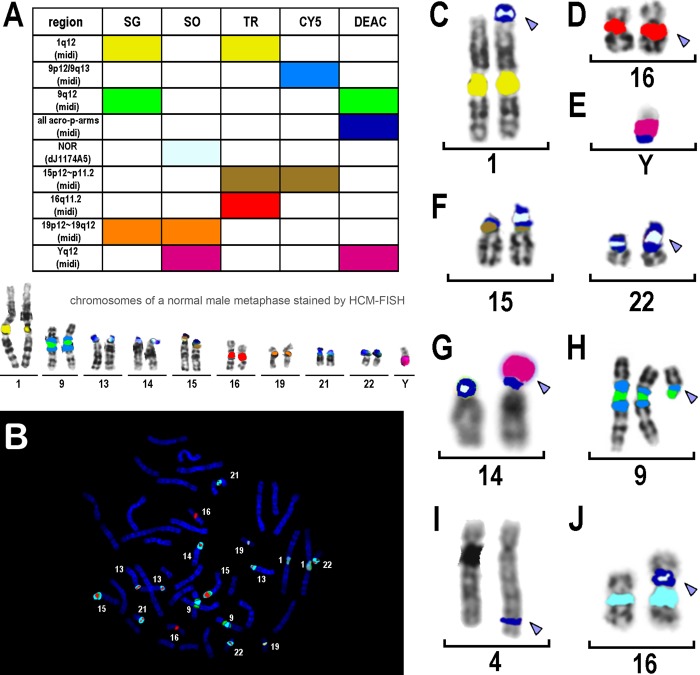

Figure 1.

(A) Label scheme used for the heterochromatin multicolor fluorescence in situ hybridization (HCM-FISH) probe set. The pseudocolors used for the corresponding region-specific DNA probes in C through J are used to indicate the fluorochromes applied to generate the HCM-FISH probe set. Also, the nine labeled chromosome pairs and the Y chromosome are shown in pseudocolor depiction below the scheme. Eight microdissection (midi)–derived and one cosmid probe (dj1174A5) were labeled by Spectrum Green (SG), Spectrum Orange (SO), Texas Red (TR), cyanine 5 (CY5), and diethylaminocoumarin (DEAC) as depicted. acro-p-arms, short arms of all acrocentric human chromosomes; NOR, nucleolus organizer region. (B) Real color depiction of a female metaphase after HCM-FISH. All labeled chromosomes are highlighted by the chromosome numbers. Chromosomes are counterstained in dark blue by 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), CY5 and SG are depicted in greenish colors, TR and SO are in reddish ones, and DEAC is in light blue. (C-J) Typical FISH results after application of the HCM-FISH probe set on a metaphase of a normal control (see Table 1). (C) HCM-FISH revealed in one hybridization step the nature of the derivative chromosome 1 (arrowhead) in case 2 (Table 1), that is, der(1)t(1;acro)(p36.33;p11.2). (D) In case 3 (Table 1), a suggested 16qh+ (arrowhead) could be confirmed. (E) der(Y)t(Y;acro)(q11.2;p12) was characterized in case 4 (Table 1). (F) In case 5 (Table 1), the short arms of both chromosomes 15 and one chromosome 22 looked abnormal. By HCM-FISH, the following could be defined: one chromosome 15 has an enlarged β-satellite–positive region (left chromosome 15), the second chromosome had double satellites (right chromosome 15), and the chromosome 22 in question had an enlarged midi-positive region plus double satellites (arrowhead). (G) In case 7 (Table 1), the extremely enlarged short arm of one chromosome 14 (arrowhead) derived from Yq12 and a final karyotype of 46,XX,der(14)t(Y;14)(q12;p13) was characterized. (H) A small supernumerary marker chromosome (sSMC) was present in case 9 (Table 1). It was initially suggested to be derived from an acrocentric chromosome; however, HCM-FISH characterized the sSMC as a derivative of the short arm of chromosome 9 (arrowhead): del(9)(q11.1~12). (I) The unknown material inserted in 4q34.2 of case 10 (Table 1) was characterized by HCM-FISH as derived from the short arm of an acrocentric chromosome (arrowhead). (J) In case 11 (Table 1), short arm material derived from an acrocentric chromosome was inserted in a derivative chromosome 16 in p11.2 (arrowhead).

The DNA of the nine probes was amplified in vitro and labeled by degenerated oligonucleotide primer polymerase chain reaction (DOP-PCR) according to standard procedures (Telenius et al. 1992). The amplification procedure followed a published scheme (Fig. 2A in Liehr et al. 2002b). The used fluorochromes Spectrum Green (SG), Spectrum Orange (SO), Texas Red (TR), cyanine 5 (CY5), and diethylaminocoumarin (DEAC) were applied for the nine DNA probes as depicted in Figure 1A. Thus, each DNA probe obtained its unique fluorochrome combination, which could be transformed into pseudocolors (Fig. 1) using the software mentioned below.

Twenty metaphase spreads were analyzed, each using a fluorescence microscope (Axioplan 2 MOT; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with appropriate filter sets to discriminate between all five fluorochromes and the counterstain 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Image capturing and processing were carried out using an Isis mFISH imaging system (MetaSystems; Altlussheim, Germany).

Clinical Cases

Overall, 30 clinical cases were studied already by HCM-FISH (Table 1). The clinical indications were infertility, repeated abortions, dysmorphic features and/or mental retardation, or a prenatal cytogenetic study due to advanced maternal age (Table 1). In all studied cases, apart from cases 1 and 1a to 1d, which were normal controls, banding cytogenetics revealed an aberrant karyotype. M-FISH was not informative in cases 2, 4, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, and 14 (results not shown). In cases 3, 5, 12, 13, and 15, heteromorphisms were suggested after Giemsa stained chromsomes banding. In the additional redundant 11 cases (Table 1), similar observations were made. In case 9, HCM-FISH was applied directly, as an sSMC derived from an acrocentric chromosome was suggested.

Table 1.

Cases Solved by HCM-FISH

| Case No. | Clinical Indication | Final Cytogenetic Result |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | None: normal control | 46,XY |

| 2 | Infertility | 46,XX,der(1)t(1;acro)(p36.33;p11.2) |

| 3 | Prenatally detected; advanced maternal age | 46,XY,16qh+ |

| 4 | Infertility | 46,X,der(Y)t(Y;acro)(q11.2;p12) |

| 5 | Dysmorphic features | 46,XY,15βsat+,15pss,22pstk+pss |

| 6 | Infertility | 46,XY,der(13)t(Y;13)(q11.2;p12) |

| 7 | Prenatally detected; advanced maternal age | 46,XX,der(14)t(Y;14)(q12;p13) |

| 8 | Infertility | 46,XY,der(15)t(Y;15)(q12;p13) |

| 9 | Dysmorphic features, mentally retarded | 47,XX,+del(9)(q11.1~12) |

| 10 | Dysmorphic features, mentally retarded | 46,XX,der(4)ins(4;acro)(q34.2;p11.2p12) |

| 11 | Dysmorphic features, mentally retarded | 46,XX,inv(2)(q31q37.3),ins(16;acro)(p11.2;p11.2p12) |

| 12 | Repeated abortions | 46,XX,14pstkpstk,21pstk+ |

| 13 | Repeated abortions | 46,XX,22pstk+pss |

| 14 | Repeated abortions | 46,XX,inv(9)(var5) |

| 15 | Infertility | 46,XY,21pstkpstk |

| 15 Additional Redundant Cases | ||

| 1a | None: normal control | 46,XY |

| 1b–1d | None: normal control | 46,XX |

| 4a–4b | Infertility | 46,X,der(Y)t(Y;acro)(q11.2;p12) |

| 6a | Infertility | 46,XX,der(13)t(Y;13)(q11.2;p12) |

| 8a–8b | Infertility | 46,XY,der(15)t(Y;15)(q12;p13) |

| 8c–8d | Infertility | 46,XX,der(15)t(Y;15)(q12;p13) |

| 12a | Repeated abortions | 46,XY,14pstkpstk |

| 12b | Repeated abortions | 46,XY,21pstk+ |

| 13a–13b | Repeated abortions | 46,XX,22pstk+pss |

Results

In the present study, it could be demonstrated that HCM-FISH can be used to characterize within one single step chromosomal rearrangements with gross involvement of heterochromatic material. The HCM-FISH probe set was established first in five control cases (result shown for case 1 in Fig. 1A and for case 1b in Fig. 1B). The probe mix appeared to work reliably and stably and stained the foreseen chromosomal regions as expected. Afterwards, it was applied in the five groups of patients listed below (Table 1). All chromosomal aberrations in cases 2 to 14 were initially detected by GTG banding.

Heterochromatic material attached to the tip of a nonacrocentric chromosomal arm: In cases 2, 4, 4a, and 4b, the short arm of a acrocentric chromosome unable to be further characterized was attached to the short arm of a chromosome 1 (Fig. 1C) or the long arm of a Y chromosome (Fig. 1E).

Heterochromatic material attached to the end of an acrocentric chromosomal arm: In cases 5-8, 12, 13, and 15, the short arms of different acrocentric chromosomes were enlarged. Chromosome 15p–specific β-satellite DNA was amplified in one chromosome 15 of case 5 (Fig. 1F); additionally, double satellites (dss) were present on the second chromosome 15 and one chromosome 22 in case 5. Furthermore, chromosome 22 of case 5 with dss had a so-called increase in the length of the stalk of the short arm (pstk+) (Fig. 1F). Similar heteromorphisms were the reason for the enlargements of acrocentric p-arms in cases 12 (including cases 12a and 12b), 13 (including cases 13a and 13b), and 15: dss, pstk+, or double stalks (pstkpstk) were characterized (Table 1). In cases 6, 7, and 8 (including cases 6a and 8a–8d), heterochromatic material derived from Yq12 was added to the short arms of a chromosome 13, 14 (Fig. 1G), or 15.

Heterochromatic material inserted in an autosome: In cases 10 and 11, undefined additional material was inserted into a chromosome 4 and 16, respectively. By HCM-FISH, this material was defined to be derived from an acrocentric short arm (Fig. 1I and 1J).

Enlargement of heterochromatic blocks in autosomes: In cases 3 and 14, the heterochromatic blocks of one chromosome 16 and 9, respectively, were enlarged. In case 3, it was an enlargement of 16q11.2, describable as 16qh+ (Fig. 1D). In case 14, the enlargement resulted from an additional band derived from DNA homologous to midi 36 (specific for 9p12/9q13).

Potentially heterochromatic sSMC: Case 9 was studied by the HCM-FISH probe set, as a heterochromatic; it was most likely that acrocentric chromosome–derived sSMC was expected according to GTG banding. Surprisingly, this sSMC turned out to be del(9)(q11.1~12), also describable as der(9)(pter->q11.1~12:) (Fig. 1H).

Discussion

During the last decades, numerous mFISH approaches have been developed (Liehr 2012a): M-FISH/SKY is able to characterize the origin and/or composition of larger euchromatic-derivative chromosomes (Speicher et al. 1996; Schröck et al. 1996); cenM-FISH can identify the chromosomal origin of sSMC (Nietzel et al. 2001); FISH banding and the use of locus-specific probes enable a better breakpoint characterization than banding cytogenetics (Weise et al. 2002; Manvelyan et al. 2007); and POD-FISH is able to determine the parental origin of derivative chromosomes on a single cell level (Polityko et al. 2009). Even though there were already probe sets specific for some of the large heterochromatic human chromosomal regions, like pericentromere of chromosome 9 (Starke et al. 2002), or short arms of all acrocentric chromosomes (Trifonov et al. 2003), no probe set was available up to now that was directed against all of them. The HCM-FISH probe set closes this gap in mFISH approaches; within one single step, chromosomal rearrangements with gross involvement of heterochromatic material can be characterized, as shown for cases 2 to 15.

Here, HCM-FISH was applied for the characterization of five different kinds of chromosomal rearrangements and proved to be a helpful tool in clinical cytogenetic diagnostics. However, the HCM-FISH probe set could also be used to answer questions in other fields, such as tumor cytogenetics or evolutionary studies. Examples would be interstitial heterochromatin in tumor-associated derivative chromosomes (Doneda et al. 1989) or studies on evolutionarily conserved heterochromatin (Mrasek et al. 2003).

If heterochromatic material is attached to the tip of a nonacrocentric chromosomal arm, the carrier can be clinically normal and only detected due to infertility or clinically affected due to essential loss of subtelomeric material in the “receiving” chromosome. There are cases reported with attached heterochromatin derived from an acrocentric short arm, similar to the present cases 2 and 4 (Weise et al. 2002), or derived from Yq12 (de Ravel et al. 2004; Hiraki et al. 2006). Yet, there are no other terminal additions of heterochromatic material reported as inborn rearrangements. However, in tumor cytogenetics, terminal translocations with breakpoints in 16q11.2 (Tsuda et al. 1999) or the pericentric region of chromosome 19 (Nagel et al. 2009) are reported.

Heterochromatic material attached to the end of an acrocentric chromosomal arm can have various sources. In general, such derivative acrocentric chromosomes are considered to be heteromorphic variations without any clinical meaning. They can be found in infertility patients and in those with clinical problems. In rare cases, the clinical phenotype of a patient is due to euchromatin translocated to an acrocentric short arm (Trifonov et al. 2003). The cases included in this study had only heterochromatic variants, considered to have no clinical meaning. However, their influence on fertility is still a matter of discussion (Codina-Pascual et al. 2006). In cases 5, 12, 13, and 15, the enlargement of one or more acrocentric short arms was due to double satellite formation (dss), increase in the length of the stalk of the short arm (pstk+), or double stalks (pstkpstk). These are well-known length variations in heterochromatic segments described in the corresponding standard literature (Shaffer et al. 2009). In most of them, the NOR is involved; however, systematic studies aligning results from NOR silver staining (Goodpasture et al. 1976) and FISH studies using a NOR-specific or an rDNA probe are still lacking. In case 5 also, 15p-specific β-satellite DNA was amplified on one chromosome 15, a variant less frequently observed (Acar et al. 1999) and not yet included in Shaffer et al. (2009). Finally, the short arm of an acrocentric chromosome can be enlarged due to an unbalanced translocation of Yq12 material (cases 6–8). Most frequently observed are der(15)t(Y;15)(q12;p13) (Chen et al. 2007), while corresponding derivatives of chromosomes 13 (Morris et al. 1987), 14 (Buys et al. 1979), 21 (Ng et al. 2006), or 22 are rarely or have not been seen up to now.

Insertion of heterochromatic material into a chromosome arm of an autosome was present in cases 10 and 11 of this study. HCM-FISH showed in one step that this material was derived from an acrocentric short arm, once with and once without the NOR region. Similar reports are scarcely available in the literature (Watt et al. 1984; Reddy and Sulcova 1998; Guttenbach et al. 1998; Chen et al. 2004). However, even such an insertion in an X chromosome was seen once (Tamagaki et al. 2000). Also, heterochromatic material from the pericentric region of chromosome 9 may be inserted into euchromatic (own unpublished observation) of heterochromatic material of other chromosomes (Doneda et al. 1998). Furthermore, Yq12 (Ashton-Prolla et al. 1997) and 16q11.2 material (McKeever et al. 1996) were observed to be inserted in another chromosome. Moreover, heterochromatic insertions such as Yq12 have been observed in tumor cytogenetics (Sala et al. 2007).

Enlargement of heterochromatic blocks in autosomes, specifically in chromosomes 1, 9, and 16, is well known and described in Shaffer et al. (2009) and elsewhere (Starke et al. 2002). Variants such as qh+, ph+, and qh– can be easily characterized by HCM-FISH. Also, the variants of chromosome 9 reported in Starke et al. (2002) can be visualized, similar to here in case 14.

Finally, HCM-FISH is suited to be used for the one-step characterization of potentially heterochromatic sSMC cases. In case 9, an acrocentric chromosome–derived sSMC was expected but turned out to be del(9)(q11.1~12). Thus, sSMC, being largely C banding-positive, are good candidates to be tested by HCM-FISH. sSMC derived from chromosomes 1, 9, 16, 19, or any acrocentric chromosome, can be determined or at least narrowed for their origin using this probe set, including such sSMC being Yq12 positive. Thus, over 55% of sSMC can be characterized with this simple probe set (Liehr 2012b).

In conclusion, we present a new mFISH probe set easily and effectively applicable in clinical cytogenetic routine diagnostics. It could be enlarged by additional probes, for example, an rDNA probe (Muravenko et al. 2001), midi probes of obviously heterochromatic sSMC of unclear origin within the human genome (Mackie Ogilvie et al. 2001), or regions of cytogenetically visible copy number variants (Manvelyan et al. 2011). The application of HCM-FISH will be helpful in tumor cytogenetics as well as in evolution research studies; for the latter, the addition of species-specific heterochromatic DNA probes would also be recommended.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported in part by Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung/Deutsche Luft-und Raumfahrtbehörder (BMBF/DLR) (BLR 08/004 and BRA 09/020), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (LI 820/19–1, LI 820/32–1), Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung (2011_A42), and Dr. Robert Pfleger Stiftung.

References

- Acar H, Cora T, Erkul I. 1999. Coexistence of inverted Y, chromosome 15p+ and abnormal phenotype. Genet Couns. 10:163–170 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton-Prolla P, Gershin IF, Babu A, Neu RL, Zinberg RE, Willner JP, Desnick RJ, Cotter PD. 1997. Prenatal diagnosis of a familial interchromosomal insertion of Y chromosome heterochromatin. Am J Med Genet. 73:470–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buys CH, Anders GJ, Borkent-Ypma JM, Blenkers-Platter JA, van der Hoek-van der Veen AY. 1979. Familial transmission of a translocation Y/14. Hum Genet. 53:125–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CP, Chern SR, Lee CC, Chen WL, Wang W. 2004. Prenatal diagnosis of interstitially satellited 6p. Prenat Diagn. 24: 430–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Chen G, Lian Y, Gao X, Huang J, Qiao J. 2007. A normal birth following preimplantation genetic diagnosis by FISH determination in the carriers of der(15)t(Y;15)(Yq12;15p11) translocations: two case reports. J Assist Reprod Genet. 24:483–488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codina-Pascual M, Navarro J, Oliver-Bonet M, Kraus J, Speicher MR, Arango O, Egozcue J, Benet J. 2006. Behaviour of human heterochromatic regions during the synapsis of homologous chromosomes. Hum Reprod. 21:1490–1497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Ravel TJ, Fryns JP, Van Driessche J, Vermeesch JR. 2004. Complex chromosome re-arrangement 45,X,t(Y;9) in a girl with sex reversal and mental retardation. Am J Med Genet A. 124A:259–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doneda L, Gandolfi P, Nocera G, Larizza L. 1998. A rare chromosome 5 heterochromatic variant derived from insertion of 9qh satellite 3 sequences. Chromosome Res. 6:411–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doneda L, Ginelli E, Agresti A, Larizza L. 1989. In situ hybridization analysis of interstitial C-heterochromatin in marker chromosomes of two human melanomas. Cancer Res. 49:433–438 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodpasture C, Bloom SE, Hsu TC, Arrighi FE. 1976. Human nucleolus organizers: the satellites or the stalks? Am J Hum Genet 28:559–566 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttenbach M, Nassar N, Feichtinger W, Steinlein C, Nanda I, Wanner G, Kerem B, Schmid M. 1998. An interstitial nucleolus organizer region in the long arm of human chromosome 7: cytogenetic characterization and familial segregation. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 80:104–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraki Y, Fujita H, Yamamori S, Ohashi H, Eguchi M, Harada N, Mizuguchi T, Matsumoto N. 2006. Mild craniosynostosis with 1p36.3 trisomy and 1p36.3 deletion syndrome caused by familial translocation t(Y;1). Am J Med Genet A. 140:1773–1777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liehr T. 2012a. Basics and literature on multicolor fluorescence in situ hybridization application. http://www.fish.uniklinikum-jena.de/mFISH.html Accessed September 12, 2012

- Liehr T. 2012b. Small supernumerary marker chromosomes. http://www.fish.uniklinikum-jena.de/sSMC.html Accessed September 12, 2012

- Liehr T, Claussen U, Starke H. 2004. Small supernumerary marker chromosomes (sSMC) in humans. Cytogenet Genome Res. 107:55–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liehr T, Heller A, Starke H, Claussen U. 2002a. FISH banding methods: applications in research and diagnostics. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2:217–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liehr T, Heller A, Starke H, Rubtsov N, Trifonov V, Mrasek K, Weise A, Kuechler A, Claussen U. 2002b. Microdissection based high resolution multicolor banding for all 24 human chromosomes. Int J Mol Med. 9:335–339 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liehr T, Mrasek K, Weise A, Dufke A, Rodríguez L, Martínez Guardia N, Sanchís A, Vermeesch JR, Ramel C, Polityko A, et al. 2006. Small supernumerary marker chromosomes: progress towards a genotype-phenotype correlation. Cytogenet Genome Res. 112:23–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie Ogilvie C, Harrison RH, Horsley SW, Hodgson SV, Kearney L. 2001. A mitotically stable marker chromosome negative for whole chromosome libraries, centromere probes and chromosome specific telomere regions: a novel class of supernumerary marker chromosome? Cytogenet Cell Genet. 92:69–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manolakos E, Vetro A, Kefalas K, Rapti S-M, Louizou E, Garas A, Kitsos G, Vasileiadis L, Tsoplou P, Eleftheriades M, et al. 2010. The use of array-CGH in a cohort of Greek children with developmental delay. Mol Cytogenet. 3:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manvelyan M, Cremer FW, Lancé J, Kläs R, Kelbova C, Ramel C, Reichenbach H, Schmidt C, Ewers E, Kreskowski K, et al. 2011. New cytogenetically visible copy number variant in region 8q21.2. Mol Cytogenet. 4:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manvelyan M, Schreyer I, Höls-Herpertz I, Köhler S, Niemann R, Hehr U, Belitz B, Bartels I, Götz J, Huhle D, et al. 2007. Forty-eight new cases with infertility due to balanced chromosomal rearrangements: detailed molecular cytogenetic analysis of the 90 involved breakpoints. Int J Mol Med. 19:855–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeever PE, Dennis TR, Burgess AC, Meltzer PS, Marchuk DA, Trent JM. 1996. Chromosome breakpoint at 17q11.2 and insertion of DNA from three different chromosomes in a glioblastoma with exceptional glial fibrillary acidic protein expression. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 87:41–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris MI, Hanson FW, Tennant FR. 1987. A novel Y/13 familial translocation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 157:857–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrasek K, Heller A, Rubtsov N, Trifonov V, Starke H, Claussen U, Liehr T. 2003. Detailed Hylobates lar karyotype defined by 25-color FISH and multicolor banding. Int J Mol Med. 12:139–146 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muravenko OV, Badaeva ED, Amosova AV, Shostak NG, Popov KV, Zelenin AV. 2001. [Localization of DNA probes for human ribosomal genes on barley chromosomes]. Genetika. 37:1721–1724 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel I, Akasaka T, Klapper W, Gesk S, Böttcher S, Ritgen M, Harder L, Kneba M, Dyer MJ, Siebert R. 2009. Identification of the gene encoding cyclin E1 (CCNE1) as a novel IGH translocation partner in t(14;19)(q32;q12) in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Haematologica. 94:1020–1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng LK, Kwok YK, Tang LY, Ng PP, Ghosh A, Lau ET, Tang MH. 2006. Prenatal detection of a de novo Yqh-acrocentric translocation. Clin Biochem. 39:219–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nietzel A, Rocchi M, Starke H, Heller A, Fiedler W, Wlodarska I, Loncarevic IF, Beensen V, Claussen U, Liehr T. 2001. A new multicolor-FISH approach for the characterization of marker chromosomes: centromere-specific multicolor-FISH (cenM-FISH). Hum Genet. 108:199–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polityko AD, Khurs OM, Kulpanovich AI, Mosse KA, Solntsava AV, Rumyantseva NV, Naumchik IV, Liehr T, Weise A, Mkrtchyan H. 2009. Paternally derived der(7)t(Y;7)(p11.1~11.2;p22.3)dn in a mosaic case with Turner syndrome. Eur J Med Genet. 52:207–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy KS, Sulcova V. 1998. The mobile nature of acrocentric elements illustrated by three unusual chromosome variants. Hum Genet. 102:653–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala E, Villa N, Crosti F, Miozzo M, Perego P, Cappellini A, Bonazzi C, Barisani D, Dalprà L. 2007. Endometrioid-like yolk sac and Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors in a carrier of a Y heterochromatin insertion into 1qh region: a causal association? Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 173:164–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröck E, du Manoir S, Veldman T, Schoell B, Wienberg J, Ferguson-Smith MA, Ning Y, Ledbetter DH, Bar-Am I, Soenksen D, et al. 1996. Multicolor spectral karyotyping of human chromosomes. Science. 273:494–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer LG, Slovak ML, Campbell LJ, eds. 2009. ISCN 2009: An International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature. Basel: S. Karger [Google Scholar]

- Speicher MR, Gwyn Ballard S, Ward DC. 1996. Karyotyping human chromosomes by combinatorial multi-fluor FISH. Nat Genet.12:368–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starke H, Seidel J, Henn W, Reichardt S, Volleth M, Stumm M, Behrend C, Sandig KR, Kelbova C, Senger G, et al. 2002. Homologous sequences at human chromosome 9 bands p12 and q13–21.1 are involved in different patterns of pericentric rearrangements. Eur J Hum Genet. 10:790–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamagaki A, Shima M, Tomita R, Okumura M, Shibata M, Morichika S, Kurahashi H, Giddings JC, Yoshioka A, Yokobayashi Y. 2000. Segregation of a pure form of spastic paraplegia and NOR insertion into Xq11.2. Am J Med Genet. 94:5–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telenius H, Carter NP, Bebb CE, Nordenskjöld M, Ponder BA, Tunnacliffe A. 1992. Degenerate oligonucleotide-primed PCR: general amplification of target DNA by a single degenerate primer. Genomics. 13:718–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trifonov V, Seidel J, Starke H, Martina P, Beensen V, Ziegler M, Hartmann I, Heller A, Nietzel A, Claussen U, Liehr T. 2003. Enlarged chromosome 13 p-arm hiding a cryptic partial trisomy 6p22.2-pter. Prenat Diagn. 23:427–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda H, Takarabe T, Fukutomi T, Hirohashi S. 1999. der(16)t(1;16)/der(1;16) in breast cancer detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization is an indicator of better patient prognosis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 24:72–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt JL, Couzin DA, Lloyd DJ, Stephen GS, McKay E. 1984. A familial insertion involving an active nucleolar organiser within chromosome 12. J Med Genet. 21:379–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weimer J, Heidemann S, von Kaisenberg CS, Grote W, Arnold N, Bens S, Caliebe A. 2011. Isolated trisomy 7q21.2–31.31 resulting from a complex familial rearrangement involving chromosomes 7, 9 and 10. Mol Cytogenet. 4:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weise A, Gross M, Mrasek K, Mkrtchyan H, Horsthemke B, Jonsrud C, Von Eggeling F, Hinreiner S, Witthuhn V, Claussen U, Liehr T. 2008. Parental-origin-determination fluorescence in situ hybridization distinguishes homologous human chromosomes on a single-cell level. Int J Mol Med. 21:189–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weise A, Starke H, Heller A, Tönnies H, Volleth M, Stumm M, Gabriele S, Nietzel A, Claussen U, Liehr T. 2002. Chromosome 2 aberrations in clinical cases characterised by high resolution multicolour banding and region specific FISH probes. J Med Genet. 39:434–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]