Abstract

Using mass spectrometry (MS), we examined the impact of endothelial lipase (EL) overexpression on the cellular phospholipid (PL) and triglyceride (TG) content of human aortic endothelial cells (HAEC) and of mouse plasma and liver tissue. In HAEC incubated with the major EL substrate, HDL, adenovirus (Ad)-mediated EL overexpression resulted in the generation of various lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) and lysophosphatidylethanolamine (LPE) species in cell culture supernatants. While the cellular phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) content remained unaltered, cellular phosphatidylcholine (PC)-, LPC- and TG-contents were significantly increased upon EL overexpression. Importantly, cellular lipid composition was not altered when EL was overexpressed in the absence of HDL. [14C]-LPC accumulated in EL overexpressing, but not LacZ-control cells, incubated with [14C]-PC labeled HDL, indicating EL-mediated LPC supply. Exogenously added [14C]-LPC accumulated in HAEC as well. Its conversion to [14C]-PC was sensitive to a lysophospholipid acyltransferase (LPLAT) inhibitor, thimerosal. Incorporation of [3H]-Choline into cellular PC was 56% lower in EL compared with LacZ cells, indicating decreased endogenous PC synthesis. In mice, adenovirus mediated EL overexpression decreased plasma PC, PE and LPC and increased liver LPC, LPE and TG content. Based on our results, we conclude that EL not only supplies cells with FFA as found previously, but also with HDL-derived LPC and LPE species resulting in increased cellular TG and PC content as well as decreased endogenous PC synthesis.

Abbreviations: EL, endothelial lipase; LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; 16:0 LPC, palmitoyl-lysophosphatidylcholine; 18:2 LPC, linoleoyl-LPC; 20:4 LPC, arachidonoyl-LPC; 18:1 LPC, oleoyl-LPC; HAEC, human aortic endothelial cells; AA, arachidonic acid; PL, phospholipids; LysoPL, lysophospholipids; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; ATGL, adipose triglyceride lipase; DGAT, diacylglycerol acyltransferase; CT, CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase; ET, CTP:phosphoethanolamine cytidylyltransferase; LPLATs, lysophospholipid acyltransferases; BSA, bovine serum albumin; FCS, fetal calf serum; MS, mass spectrometry

Keywords: Mass spectrometry, Endothelial cell, Lysophospholipid, HDL, Adenovirus

Highlights

► Endothelial lipase (EL) was overexpressed in human endothelial cells and in mice. ► EL generated various lysophosphatidyl-choline (LPC) and -ethanolamine (LPE) species. ► EL directly supplied cells with 14C-HDL-derived 14C-LPC. ► EL increased cellular LPC, phosphatidylcholine and triglyceride content. ►In mice, EL increased hepatic triglycerides, LPC and LPE.

1. Introduction

EL is a member of the triglyceride (TG) lipase gene family [1,2]. A distinct feature of EL, compared with other family members is its endothelial expression. EL is synthesized as a 55 kDa protein that is secreted as a 68 kDa protein upon maturation. After secretion, a portion of EL is cleaved and inactivated by members of the mammalian proprotein convertase family [3,4]. Uncleaved EL is bound to heparan-sulfate proteoglycans on the cell surface. Here, by its bridging function, EL facilitates HDL particle binding and uptake [5,6], as well as selective uptake of HDL cholesteryl esters [6].

By virtue of its pronounced sn-1 phospholipase activity, EL cleaves lipoprotein-associated phospholipids (PL), primarily HDL-phosphatidylethanolamine (HDL-PE) and -phosphatidylcholine (HDL-PC), generating mostly saturated free fatty acids (FFA) [7–9] and sn-1 lyso sn-2 acyl lysophospholipids (LysoPL) [7,9]. By its rather weak lysophospholipase activity, EL further hydrolyzes some of those EL-generated LPL, liberating unsaturated FFA [7].

EL expression is increased under inflammatory conditions as observed in cultured endothelial cells exposed to interleukin-1ß (IL-1ß) or tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) as well as in mice and humans upon LPS injection [10,11]. Furthermore, EL protein mass and activity have been found to be elevated in patients with subclinical inflammation as encountered in the metabolic syndrome and coronary atherosclerosis [12,13].

The capacity of EL to generate FFA and LysoPL [7] and to supply cells with those lipids [7,14], strongly argues for a role of EL in the modulation of cellular lipid content and composition.

Two endogenous biosynthetic pathways, the de novo (Kennedy Pathway) [15] and the remodeling pathway (Lands' Cycle) [16] are responsible for the maintenance of the physiological lipid balance of the cell [17]. Most abundant glycero(phospho)lipids, generated in the de novo pathway are derived from phosphatidic acid (PA)-derived diacylglycerol (DAG). TG is formed from DAG in a reaction catalyzed by diacylglycerol acyltransferase (DGAT) [18] and can be converted back to DAG and FFA by adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) [19]. PC and PE are formed in the CDP-choline and CDP-ethanolamine pathway, whereby the rate limiting steps are catalyzed by the enzymes CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase (CT) and CTP:phosphoethanolamine cytidylyltransferase (ET) [15,20]. The de novo generated PL in turn undergo remodeling (Lands' pathway) through the concerted actions of cellular phospholipases A2 (PLA2) and lysophospholipid acyltransferases (LPLAT), resulting in alteration of PL acyl composition primarily at the sn-2 position [16].

In the present study, we addressed the impact of EL overexpression on the content and composition of the endothelial TG- and PL-pools, both in vitro in EL-overexpressing HAEC as well as in vivo in mice overexpressing EL upon adenoviral infection.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture

Human primary aortic endothelial cells (HAEC) were obtained from Lonza (Cologne, Germany) and maintained in endothelial cell growth medium [EGM-MV Bullet Kit = EBM medium + growth supplements + FCS (Lonza)] supplemented with 50 IU/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells were cultured in gelatine-coated dishes at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere and were used for experiments from passages 5 to 10. Cells were seeded (75,000/well) in 12-well plates 48 h before exposure to HDL.

2.2. Isolation of human HDL

HDL (subclass 3, d = 1.125–1.21 g/ml) was prepared by sequential ultracentrifugation of plasma obtained from normolipidemic blood donors as described previously [6].

2.3. Adenovirus generation

Adenoviruses (Ad) encoding human EL (EL) and bacterial ß-galactosidase (LacZ) were prepared exactly as described previously [6].

2.4. HDL labeling

Labeling of HDL with [14C]-PC (NEN) was performed as described [7]. Briefly, 2 μCi of 1-palmitoyl-2-[14C] arachidonyl-PC was dried under nitrogen, redissolved in 30 μl ethanol, and added to a solution containing HDL (3 mg protein) and lipoprotein-deficient serum (700 μl) in a final volume of 1.7 ml in PBS. Subsequently, this mixture was incubated under argon in a shaking water bath at 37 °C for 16 h. Thereafter, labeled HDL ([14C]-HDL) was reisolated by density gradient ultracentrifugation in a TLX120 bench-top ultracentrifuge in a TLA100.4 rotor (Beckman). The HDL band was aspirated and desalted by size-exclusion chromatography using 10DG columns (BioRad).

2.5. Adenoviral infection of HAEC and treatments with HDL and [14C]-HDL

HAEC (75000/well or 150000/well) were seeded in 12- or 6-well plates. Forty eight hours later, confluent cells were infected with EL-Ad or LacZ-Ad at multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 50 in endothelial basal medium (EBM) without fetal calf serum (FCS). Following a 2 h-infection period, cells were grown in complete EBM for additional 24 h. Thereafter, cells were washed with PBS and incubated with EBM medium without supplements and without serum (serum-free medium) for 3 h. Then, serum-free medium was removed and replaced with fresh serum-free medium supplemented with either: i) PBS or 300 μg/ml HDL in PBS for 5 h, followed by lipid extraction, HPLC and MS or ii) 100 μg/ml [14C]-HDL for up to 5 h, followed by thin layer chromatography (TLC).

2.6. Lipid extraction, HPLC and MS

Following materials: i) the cell layer of one 6-well, ii) 1.5 ml of cell culture supernatant, iii) 450 μg of HDL (protein) re-isolated from cell incubation media as described above in Section 2.4, iv) 100 μl of mouse plasma, and v) 200 mg of liver tissue, were extracted according to Bligh and Dyer [21] in the presence of an internal standard (PC 12:0/12:0) and dried under a stream of nitrogen. Dried lipid extracts were resuspended in 200 μl CHCl3/MeOH (1:1, v/v) containing 1 pmol/μl of each LPC 17:1, LPE 17:1, PE 12:0/13:0 and PC 12:0/13:0 respectively, serving as internal standards. Chromatographic separation of lipids was performed by an Accela HPLC (Thermo Scientific) on a Thermo Hypersil GOLD C18, 100 × 1 mm, 1.9 μm column. Solvent A was a water solution of 1% ammonia acetate (v/v) and 0.1% formic acid (v/v) and solvent B was acetonitrile/2-propanol (5:2, v/v) supplemented with 1% ammonia acetate (v/v) and 0.1% formic acid (v/v), respectively. The gradient was run from 35% to 70% B for 4 min, then to 100% B in additional 16 min with subsequent hold at 100% for 10 min. The flow rate was 250 μl/min. Phospholipid species were determined by a TSQ Quantum ultra (Thermo Scientific) triple quadrupole instrument in positive ESI mode. The spray voltage was set to 4500 V and capillary voltage to 35 V. The PC species were detected in a precursor ion scan on m/z 184 at 34 eV. Acquisition of triglyceride species was performed on a LTQ-FT in FT full scan mode at a resolution of 200,000. Phospholipid peak areas were calculated by QuanBrowser for all lipid species and the calculated peak areas for each species were expressed according to the amount of internal standard. TG was quantified by Lipid Data Analyzer [22].

2.7. Monitoring of [14C]-LPC in cells by TLC

Following incubation with [14C]-HDL for the indicated time periods, lacZ- and EL-Ad infected cells (12-well dishes) were extensively washed with PBS and extracted with hexane/isopropanol (3:2, v/v), extracts evaporated in the SpeedVac and redissolved in chloroform before TLC using a solvent system for the separation of phospholipids (propionic acid/chloroform/1-propanol/water (3:2:2:1; v/v)). The signals corresponding to [14C]-LPC were visualized upon exposure of the TLC plates to a tritium screen (GE Healthcare) on the STORM imager.

2.8. Conversion of [14C]-LPC to [14C]-PC in HAEC

HAEC were incubated with 1 μM [14C]-16:0 LPC (NEN) in full medium containing 5% FCS in the absence or presence of indicated concentrations of thimerosal (Sigma) for 30 min, followed by the analysis of [14C]-LPC and [14C]-PC by TLC as described above.

2.9. [3H]-Choline incorporation into cellular PC

Twenty-four hours after infection with LacZ- or EL-Ad (in 12-well dishes), HAEC were washed with PBS and incubated with serum-free medium for 3 h followed by incubation with serum-free medium supplemented with 300 μg/ml HDL and 1 μCi/ml [3H]-Choline (NEN) for 5 h. After the incubation, media were removed and cells were washed 3 times with PBS, followed by extraction and TLC as described above. The signals corresponding to PC were visualized by I2 and lipid spots were cut out of the TLC plate and measured by scintillation counting. The delipidated cell layers were lysed with 1 ml of 0.3 M NaOH/0.1% SDS and the protein content was determined according to [23].

2.10. Incorporation of [14C]-arachidonic acid into cellular TG

Eight hours after infection with LacZ- or EL-Ad, cells were washed and incubated with 1 μCi/ml [14C]-arachidonic acid in full medium containing 5% FCS for 18 h. After extensive washing with PBS, cells were extracted with hexane/isopropanol (3:2, v/v), evaporated in the SpeedVac and redissolved in chloroform before TLC using a solvent system for the separation of neutral lipids (hexane/diethyl ether/acetic acid, 70:29:1, vol/vol). The signals corresponding to [14C]-TG were visualized upon exposure of the TLC plates to a tritium screen (GE Healthcare) on the STORM imager. Quantification was performed by densitometric volume report analysis.

2.11. Western blot

HAEC infected with LacZ- or EL-Ad (MOI 50; 12-well dishes), were washed with PBS and collected in 200 μl/well of loading buffer [20% (w/v) glycerol, 5% (w/v) SDS, 0.15% (w/v) bromophenol blue, 63 mmol/I Tris–HCl, pH 6.8, and 5% (v/v) ß-mercaptoethanol] followed by boiling for 10 min. 40 μl of the lysate was applied to each lane and analyzed by SDS-PAGE (10% gel) and subsequent immunoblotting using an EL-specific antibody [6] and a HRP-labeled anti rabbit secondary antibody. Protein signals were detected by an enhanced chemiluminescent substrate of HRP (SuperSignal West Pico, Pierce).

2.12. Nile Red staining

LacZ- or EL-infected HAEC were incubated with 300 μg/ml HDL for 20 h and incubated with Nile Red (100 ng/ml) for 15 min. Lipid staining was evaluated by fluorescence microscopy (Zeiss).

2.13. Phospholipase activity assay

Twenty-four hours after infection (in 12-well dishes), LacZ- or EL-Ad cells were washed with PBS and incubated with 300 μl of serum-free media supplemented with 10 U/ml of heparin for 30 min. The heparin-release media were collected, frozen at − 80 °C and subsequently used for phospholipase activity assay. The assay was done as described previously [6]. Briefly, the PC substrate was made by mixing [14C]-dipalmitoyl-phosphatidylcholine (PC) (NEN, Boston, MA, U.S.A.), lecithin (1 mg/ml) and substrate buffer Tris/TCNB [100 mM Tris/HCL, pH 7.4, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 5 mM CaCl2, 200 mM NaCl, 0.1% (w/v) NEFA-free BSA] and subsequently dried under nitrogen. Substrate was dried under a stream of nitrogen and reconstituted in the substrate buffer. Aliquots (190 μl) of the heparin-release media were mixed with 10 μl of the substrate and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The reaction was terminated by addition of 1 ml of 0.2 M HCl and extraction with hexane/isopropanol (3:2, v/v, 0.1% HCl). Aliquots (500 μl) of the upper phase were dried in a speed vac and reconstituted in 100 μl of hexane/isopropanol (3:2, v/v). After separation by TLC (hexane/diethyl ether/acetic acid, 70:29:1, vol/vol), the liberated 14C-NEFA were quantitated in a scintillation counter (Beckman). The activity was expressed as cpm/mg cell protein.

2.14. Intravenous (i.v.) injection of adenovirus and perfusion

10–12 weeks old male C57Bl/6J mice (5 per group) were anesthetized with Isofluran (Pharmacia & Upjohn SA, Guyancourt, France) and injected with 3 × 109 particles of LacZ- or EL-Ad in 100 μl of 0.9% NaCl via tail vein injection. 24 h later, blood was collected from the retroorbital plexus into EDTA-containing tubes and spun. Plasma was stored at − 70 °C before lipid extraction. For the analysis of liver samples, anesthetized mice were perfused with PBS through the left ventricle before tissue sampling. Animal experiments were conducted in conformity with the Public Health Service Policy on Human Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Austrian Ministry of Science and Research according to the Regulations for Animal Experimentation.

2.15. Statistical analysis

Cell culture experiments were performed at least three times and values are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism 5 using the paired t test, for experiments comparing 2 groups; and two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni-correction for experiments comparing 3 or more groups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant (*).

3. Results

3.1. EL releases LPC- and LPE-species from HDL-PL

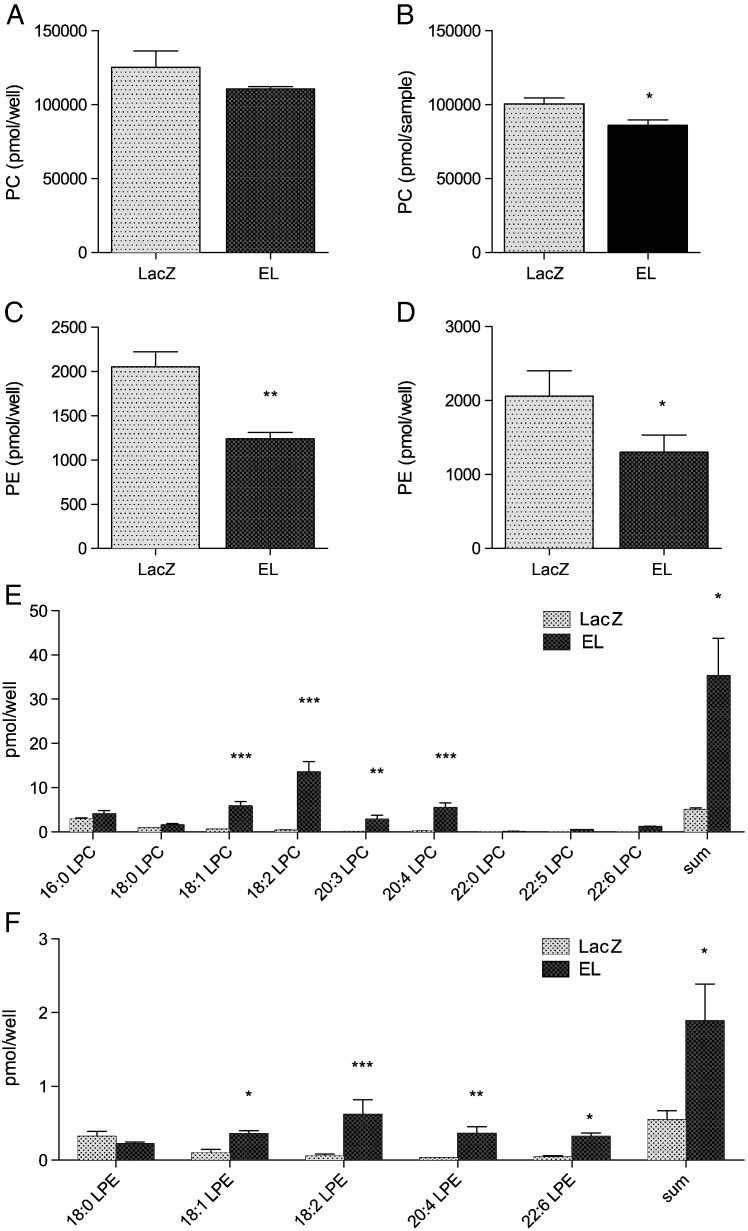

To examine the impact of EL on cellular PC, PE and TG, human EL was overexpressed in HAEC by adenoviral gene transfer (EL-Ad). The applied amount of EL-Ad (MOI 50) yielded a moderate EL overexpression: a 1.7-fold increase in the heparin-releasable phospholipase activity, compared with LacZ-Ad infected cells (Supplementary Fig. 1A) and EL signals of moderate intensity detected by Western blotting of EL-Ad cell lysates, compared with no signals in cell lysates of LacZ-Ad infected cells (Supplementary Fig. 1B). Following incubation of EL- and LacZ-Ad infected cells with HDL (in serum-free medium), we analyzed the phospholipid profile of the incubation media by MS. The analysis revealed a slight but not significant EL-mediated decrease in total PC content (Fig. 1A) as well as in the majority of distinct PC species (Supplementary Fig. 2A), when compared with LacZ-adenovirus infected control cell media. In contrast, the decrease in PC content was significant in HDL, re-isolated from incubation media of EL overexpressing cells compared with LacZ samples (Fig. 1B; Supplementary Fig. 2B). The total PE as well as all distinct PE species were significantly decreased in both incubation media (Fig. 1C; Supplementary Fig. 2C) as well as in re-isolated HDL (Fig. 1D; Supplementary Fig. 2D) of EL compared with LacZ incubations. The alterations in HDL-PC and -PE species were accompanied by profound increases in several LPC and LPE species (Fig. 1E and F, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Overexpression of EL in the presence of HDL increases LPC and LPE content in cell medium.

LacZ and EL-overexpressing HAEC were incubated in serum-free medium supplemented with 300 μg/ml HDL for 5 h. Subsequently, A) PC- C) PE- E) LPC- and F) LPE-content/profile of cell culture supernatants as well as B) PC- and D) PE-content of re-isolated HDL (450 μg protein) were determined by MS. Results shown are mean ± SD of two experiments performed in triplicates.

3.2. EL alters the PC- and TG-profile of HAEC

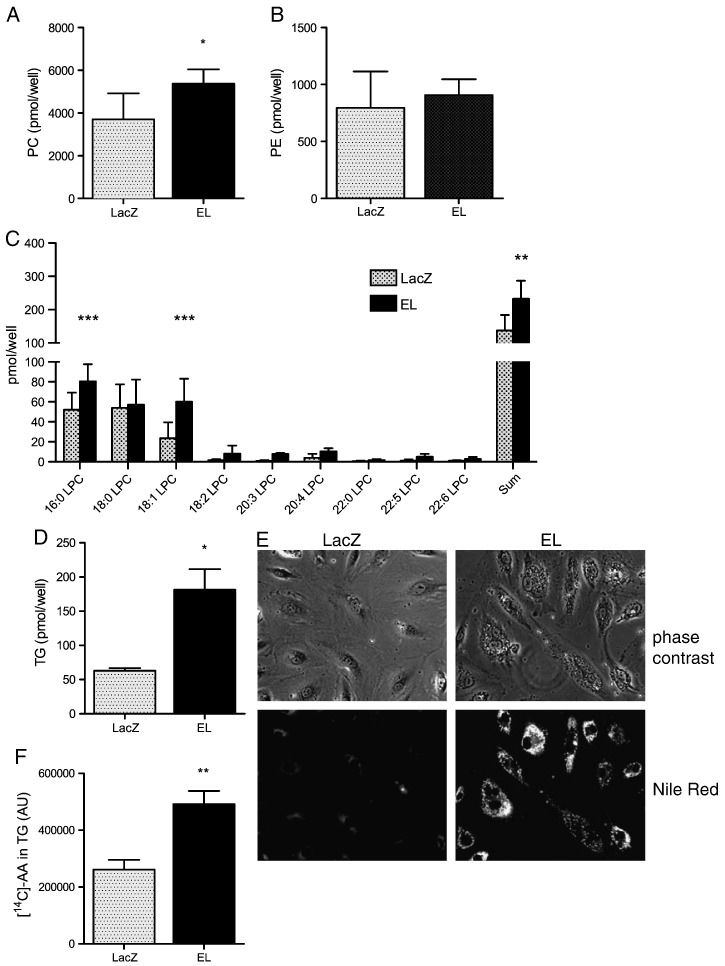

Next, we examined the impact of EL overexpression in the presence of HDL on the cellular PC, PE and TG profile of HAEC. Both the total PC content as well as various PC species were increased in EL-overexpressing cells compared with LacZ controls (Fig. 2A; Supplementary Fig. 3A). In contrast to PC, both total PE (Fig. 2B) as well as the majority of various PE species (Supplementary Fig. 3B) were unaltered in EL overexpressing HAEC compared with LacZ-infected control cells. The total LPC content as well as various LPC species were more abundant in EL overexpressing HAEC than in control cells (Fig. 2C). Unfortunately, LPE species were below the detection limit of the applied analytical approach. Importantly, cellular PC and PE were unaltered upon EL overexpression in the absence of HDL (Supplementary Fig. 4A,B,C,D). EL overexpression also markedly increased the cellular TG content, compared with LacZ-infected control cells (Fig. 2D, and Supplementary Table 1 for detailed species distribution). This increase in TG could also be demonstrated by staining of cells with the lipophilic dye Nile Red (Fig. 2E). Additionally, during incubation in full medium containing 5% FCS, EL overexpressing cells incorporated significantly more of exogenously added [14C]-arachidonic acid into TG, compared with LacZ-Ad control cells (Fig. 2F).

Fig. 2.

Overexpression of EL in the presence of HDL alters lipid composition of HAEC.

LacZ and EL-overexpressing HAEC were incubated in serum-free medium supplemented with 300 μg/ml HDL for 5 h. Subsequently, A) PC- B) PE- C) LPC- and D) TG-content/profile was determined in lipid extracts of cell layers using MS. Results represent the mean of triplicate determinations ± SD of a representative experiment performed six times. E) LacZ or EL-overexpressing HAEC were incubated in serum-free medium supplemented with 300 μg/ml HDL for 20 h. The lower panels show lipid accumulation determined by fluorescence microscopy of cells stained with Nile Red. In the upper panels, the same visual field is shown in phase contrast. F) LacZ and EL-overexpressing cells were incubated with 1 μCi/ml [14C]-arachidonic acid in full medium containing 5% FCS for 18 h. Following the separation of neutral lipids by TLC (hexane/diethyl ether/acetic acid, 70:29:1, vol/vol), the signals corresponding to [14C]-TG were quantified by densitometry. Results represent the mean of duplicate determinations ± SD of three experiments.

3.3. EL supplies cells with HDL-derived LPC

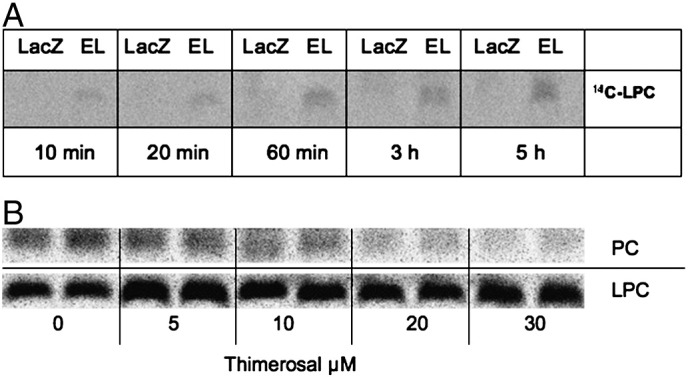

The accumulation of LPC species in EL overexpressing cells (Fig. 2C) suggested the EL-mediated supply with HDL-derived LPC. To directly demonstrate the ability of EL to supply cells with HDL-derived LPC, HAEC were incubated with HDL labeled within its phospholipid moiety with [14C]-PC. As shown in Fig. 3A, a time-dependent increase in cellular [14C]-LPC was observed in EL-overexpressing but not in LacZ-control cells.

Fig. 3.

EL supplies cells with HDL-derived LPC.

A) LacZ- and EL-Ad infected HAEC were incubated with [14C]-PC labeled HDL in serum-free medium for 5 h. Following extensive washing, lipids were extracted from cell layers and separated by TLC. The signals corresponding to [14C]-LPC were visualized upon exposure of the TLC plates to a tritium screen (GE Healthcare) on the STORM imager.

B) HAEC were incubated with 1 μM [14C]-LPC in full medium containing 5% FCS in the absence or presence of indicated concentrations of thimerosal for 30 min, followed by extraction and analysis of [14C]-LPC and [14C]-PC by TLC as described in A).

To further examine the fate of exogenously added LPC in cells, HAEC were incubated with [14C]-LPC in the absence or presence of thimerosal (a general LPCAT inhibitor). As indicated in Fig. 3B, exogenous [14C]-LPC rapidly accumulated in cells, and its conversion to [14C]-PC could be inhibited by thimerosal in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3B).

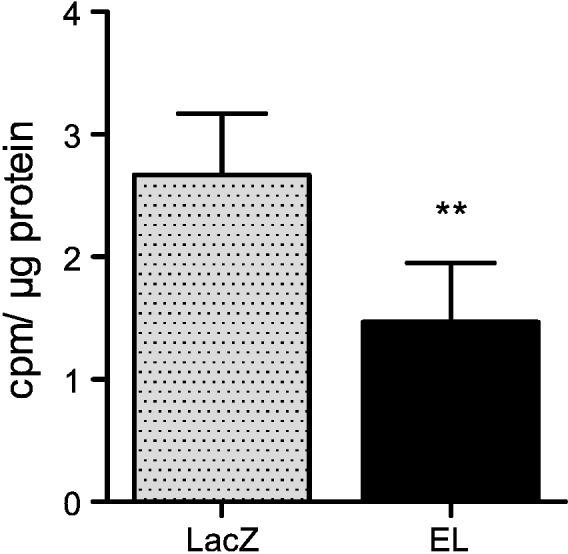

3.4. EL overexpression diminishes endogenous PC synthesis

To examine the impact of EL overexpression on the rate of endogenous PC synthesis, we measured [3H]-Choline incorporation into endogenous PC in EL- and LacZ-Ad infected cells in the presence of HDL. As shown in Fig. 4, EL overexpressing cells incorporated 56% less [3H]-Choline compared with LacZ-Ad infected control cells, indicating attenuation of endogenous PC synthesis by EL overexpression.

Fig. 4.

EL overexpression decreases endogenous PC synthesis.

Following incubation in serum-free medium for 3 h, LacZ- and EL-Ad infected HAEC (in 12-well dishes), were co-incubated in serum-free medium with 300 μg/ml HDL and 1 μCi/ml [3H]-Choline for 5 h. Following three washes of cell layers with PBS and extraction by hexane/isopropanol (3:2, v/v), the cell extracts were subjected to TLC (propionic acid/chloroform/1-propanol/water (3:2:2:1; v/v). The signals corresponding to PC were measured by scintillation counting. Results represent the mean of a triplicate experiment ± SD of three experiments.

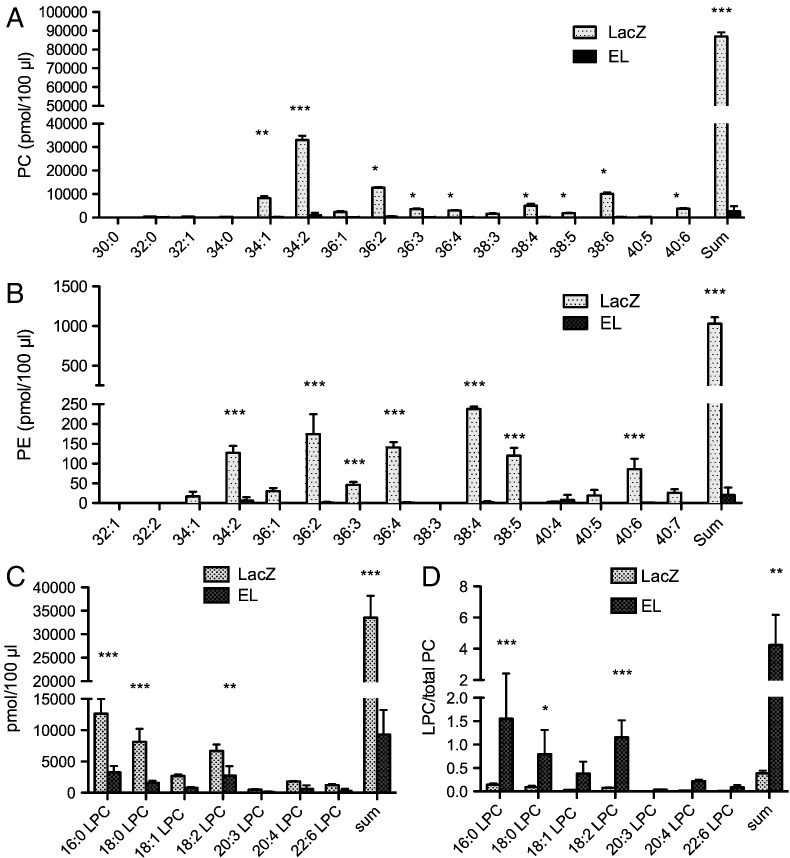

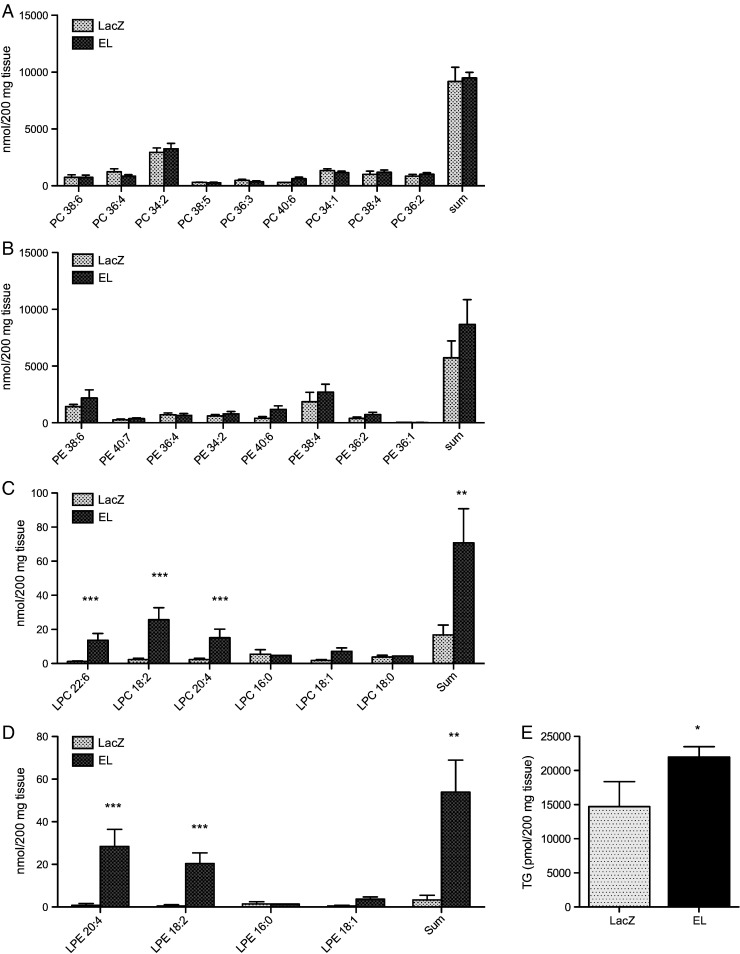

3.5. EL alters the lipid profile of mouse plasma and liver

To address the impact of EL on plasma and tissue lipid profile in vivo, EL was overexpressed in mice by i.v. EL-Ad injection. In plasma, both the PC and the PE content were strikingly decreased upon EL overexpression (Fig. 5A,B). While the plasma concentration of LPC was markedly decreased upon EL overexpression (Fig. 5C), the relative amounts of LPC, normalized to total plasma PC, were highly increased upon EL overexpression (Fig. 5D). Very low LPE plasma levels precluded their accurate quantification (not shown). In the liver, EL overexpression resulted in unaltered PC (Fig. 6A) and PE (Fig. 6B), increased LPC species 22:6, 18:2, and 20:4 (Fig. 6C) and LPE species 20:4 and 18:2 (Fig. 6D) as well as increased TG (Fig. 6E, Supplementary Table 2 for detailed list of species).

Fig. 5.

EL overexpression alters plasma PL in mice.

Blood was collected from fed, male C57Bl/6J mice, 24 h after i.v. injection of 3 × 109 virus particles of LacZ- or EL-Ad. The A) PC- B) PE- C) LPC-content/profile was determined in lipid extracts of 100 μl plasma. D) Shows the ratio of LPC normalized to total PC content. Results represent the mean ± SD of a representative experiment with 5 animals per group. Two additional experiments with 5 animals per group gave similar results.

Fig. 6.

EL overexpression promotes accumulation of TAG, LPC and LPE in mouse liver.

Perfused liver tissue was collected from fed, male C57Bl/6J mice, 24 h after i.v. injection of 3 × 109 virus particles of LacZ- or EL-Ad. The A) PC- B) PE- C) LPC- D) LPE- and E) TG-profile was determined in lipid extracts of 200 mg tissue. Results represent the mean ± SD of a representative experiment with 5 animals per group. Two additional experiments with 5 animals per group gave similar results.

4. Discussion

reviously, we demonstrated that EL by virtue of its sn-1 phospholipase and lysophospholipase activity cleaves HDL-PC, thereby generating saturated and unsaturated FFA [7], which are efficiently incorporated into TG and PL of EL overexpressing cells [7,14]. Due to its rather weak lysophospholipase activity, compared to its sn-1 phospholipase activity, ELs' action on HDL-PC also generates substantial amounts of various, mostly unsaturated sn-1-lyso, sn-2-acyl-lysoPL [7]. In the present study, we monitored the generation of LPC and LPE in EL overexpressing cells as well as in EL overexpressing mice and examined the impact of EL overexpression on cellular PL and TG content and composition by MS.

The action of EL on HDL yielded a variety of LPC and LPE species in medium. Due to an approximately 60-fold higher amount of PC than PE in HDL3 (Supplementary Fig. 5A,B), the amounts of EL-generated LPC exceeded that of LPE by approximately 30-fold (compare Fig. 1E and F). While the EL-mediated decrease in the PC content of the incubation media did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 1A), the PC content was significantly decreased in HDL re-isolated from EL incubations compared with LacZ (Fig. 1B). This more pronounced effect of EL on the reisolated HDL-PC content might be due to the presence of phospholipids not associated with HDL (soluble or bound to proteins secreted by HAEC), and accordingly less accessible for EL, in the incubation media. The more pronounced EL-mediated decrease in HDL-PE compared to -PC might be due to the fact that PE is a better substrate for EL than PC [9]. Due to endpoint measurements, our experimental approach excludes the possibility to monitor dynamic bidirectional flux of lipids between HDL and cells. However, it is likely that EL-modified HDL, depleted in PL, exhibits increased capacity to acquire lipids, including PL, from cells. Furthermore, in addition to hydrolysis of HDL-PC and -PE, the EL-mediated bridging of HDL to the cell surface [6], might further contribute to the exchange of lipids between HDL and cells.

In line with a profound EL-mediated provision of LPC, the total cellular PC content was increased (Fig. 2A), despite decreased endogenous PC synthesis (Fig. 4). Compromised de novo PC synthesis in EL overexpressing cells might be due to FFA provision by EL [7,24] with concomitantly increased TG synthesis and DAG depletion [18]. Indeed, both incorporation of exogenous FFA into TG (Fig. 2F) and the TG content (Fig. 2D,E; Supplementary Table 1) were markedly increased in EL overexpressing HAEC. In addition to supplying FFA, the EL-mediated HDL holoparticle uptake [6,25] might supply cells with HDL-TG, thus contributing to the expansion of the TG pool in EL overexpressing cells. Moreover, attenuation of CT activity by LPC [26] might, at least in part, contribute to the observed attenuation of the de novo PC synthesis in EL overexpressing cells.

Tracer experiments directly demonstrated the capacity of EL to supply cells with HDL-derived LPC (Fig. 3A). As found in HUVEC [27] reacylation of exogenous LPC is operative in HAEC as well (Fig. 3B). Considering the fact that in aqueous medium at neutral pH, acyl chains rapidly migrate from the sn-2 to the deacylated sn-1 position to give a more stable intermediate [28], we assume that EL-generated sn-2-acyl LPC are rapidly converted to sn-1-acyl isomers, followed by reacylation, as found for exogenously added [14C]-sn-1 acyl LPC.

In vivo, in mice injected intravenously with EL-adenovirus, a marked decrease in plasma PC and PE suggests a profound generation of LPC and LPE. However, we observed decreased plasma concentrations of LPC and undetectable levels of LPE upon EL overexpression. This is conceivably a consequence of a rapid removal of LPC and LPE from plasma to tissues, exemplified by concomitantly increased LPC and LPE in the liver. Furthermore, the substrate availability (PC and PE) for EL and various other plasma phospholipases is markedly decreased by EL overexpression, resulting in markedly decreased steady-state LPC and LPE plasma levels despite their overproduction. Along these lines, the relative abundance of plasma LPC (normalized to total plasma PC), was markedly increased upon EL overexpression (Fig. 5D).

In contrast to EL overexpressing HAEC, the PC content was unaltered in mouse livers most probably due to the capability of hepatocytes to secret excess PC into bile and circulation, upon incorporation into lipoproteins.

Based on our results, it is tempting to speculate that by providing LPE and LPC for LPCAT-catalyzed reacylation reactions, EL helps to circumvent the energy-consuming de novo PL synthesis. Thus, by saving cellular energy and meeting the demand for PL, EL might support endothelial cell proliferation, migration and angiogenesis, physiological states with an increased demand for energy and PL [29]. Interestingly, EL expression has been found to be upregulated in HUVEC undergoing tube formation on matrigel, compared with growth-arrested HUVEC in monolayers [2].

We conclude that EL not only supplies cells with FFA as found previously [7,14], but also with HDL-derived LPC and LPE species. This EL mediated supply with HDL-derived lipids results in the accumulation of cellular TG, and PC, accompanied by decreased endogenous PC synthesis.

Grants

This work was supported in part by the Austrian Science Foundation (FWF; grant P19473-B05 to S.F.), the Jubilee Foundation of the Austrian National Bank (grant 12778 to S.F.) and the Lanyar Foundation (grant 328 to S.F.), which had no roles in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing report or submission of the article.

The following are the supplementary materials related to this article.

Phospholipase activity and expression levels of EL in EL- and LacZ-Ad infected HAEC.

HAEC were plated in 12-well dishes and infected with LacZ- or EL-Ad at MOI 50. 24 h after infection cells were washed with PBS and A) incubated with 300 μl of serum-free media supplemented with 10 U/ml of heparin for 30 min. The heparin-release media were tested for phospholipase activity. The activity was expressed as cpm/mg cell protein. Results shown are mean ± SD of two experiments performed in triplicates.

B) After washing with PBS, cells were collected in 200 μl/well of loading buffer [20% (w/v) glycerol, 5% (w/v) SDS, 0.15% (w/v) bromophenol blue, 63 mmol/I Tris–HCl, pH 6.8, and 5% (v/v) ß-mercaptoethanol] boiled for 10 min., followed by SDS-PAGE (10% gel) and subsequent immunoblotting using anti-EL antiserum.

Impact of EL overexpression on the content of HDL-PC and -PE species.

Following incubation in serum-free medium for 3 h, LacZ and EL-overexpressing HAEC were incubated in serum-free medium supplemented with 300 μg/ml HDL for 5 h. Subsequently, A) PC- and C) PE-content/profile of incubation media and B) PC- and D) PE-content/profile of re-isolated HDL were determined by MS. Results shown are mean ± SD of two representative experiments out of four performed in triplicates.

Impact of EL overexpression on the content of cellular PC and PE species.

Following incubation in serum-free medium for 3 h, LacZ and EL-overexpressing HAEC were incubated in serum-free medium supplemented with 300 μg/ml HDL for 5 h. Subsequently, A) PC- and B) PE-content/profile was determined in lipid extracts of cell layers using mass spectrometry. Results represent the mean of triplicate determinations ± SD of a representative experiment performed 6 times.

Impact of EL overexpression on the content of cellular PC and PE species in the absence of HDL.

LacZ and EL-overexpressing HAEC were incubated in serum-free medium for 8 h. Subsequently, the cellular contents of A) total PC, B) various PC species, C) total PE and D) various PE species were determined by MS. Results shown are the mean of triplicate determinations ± SD of two experiments.

PC- and PE-content/profile of HDL3.

A) PC- and B) PE-content/profile of HDL3 determined by MS.

Impact of EL overexpression on the TG profile in HAEC.

Impact of EL overexpression on the TG profile in mouse liver.

Acknowledgements

We thank Isabella Hindler for help with the care of the mice.

References

- 1.Jaye M., Lynch K.J., Krawiec J., Marchadier D., Maugeais C., Doan K., South V., Amin D., Perrone M., Rader D.J. A novel endothelial-derived lipase that modulates HDL metabolism. Nat. Genet. 1999;21:424–428. doi: 10.1038/7766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirata K., Dichek H.L., Cioffi J.A., Choi S.Y., Leeper N.J., Quintana L., Kronmal G.S., Cooper A.D., Quertermous T. Cloning of a unique lipase from endothelial cells extends the lipase gene family. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:14170–14175. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.14170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gauster M., Hrzenjak A., Schick K., Frank S. Endothelial lipase is inactivated upon cleavage by the members of the proprotein convertase family. J. Lipid Res. 2005;46:977–987. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400500-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jin W., Fuki I.V., Seidah N.G., Benjannet S., Glick J.M., Rader D.J. Proprotein convertases [corrected] are responsible for proteolysis and inactivation of endothelial lipase. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:36551–36559. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502264200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuki I.V., Blanchard N., Jin W., Marchadier D.H., Millar J.S., Glick J.M., Rader D.J. Endogenously produced endothelial lipase enhances binding and cellular processing of plasma lipoproteins via heparan sulfate proteoglycan-mediated pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:34331–34338. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302181200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strauss J.G., Zimmermann R., Hrzenjak A., Zhou Y., Kratky D., Levak-Frank S., Kostner G.M., Zechner R., Frank S. Endothelial cell-derived lipase mediates uptake and binding of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) particles and the selective uptake of HDL-associated cholesterol esters independent of its enzymic activity. Biochem. J. 2002;368:69–79. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gauster M., Rechberger G., Sovic A., Horl G., Steyrer E., Sattler W., Frank S. Endothelial lipase releases saturated and unsaturated fatty acids of high density lipoprotein phosphatidylcholine. J. Lipid Res. 2005;46:1517–1525. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500054-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCoy M.G., Sun G.S., Marchadier D., Maugeais C., Glick J.M., Rader D.J. Characterization of the lipolytic activity of endothelial lipase. J. Lipid Res. 2002;43:921–929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen S., Subbaiah P.V. Phospholipid and fatty acid specificity of endothelial lipase: potential role of the enzyme in the delivery of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) to tissues. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1771:1319–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin W., Sun G.S., Marchadier D., Octtaviani E., Glick J.M., Rader D.J. Endothelial cells secrete triglyceride lipase and phospholipase activities in response to cytokines as a result of endothelial lipase. Circ. Res. 2003;92:644–650. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000064502.47539.6D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Badellino K.O., Wolfe M.L., Reilly M.P., Rader D.J. Endothelial lipase is increased in vivo by inflammation in humans. Circulation. 2008;117:678–685. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.707349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Badellino K.O., Wolfe M.L., Reilly M.P., Rader D.J. Endothelial lipase concentrations are increased in metabolic syndrome and associated with coronary atherosclerosis. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e22. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paradis M.E., Badellino K.O., Rader D.J., Deshaies Y., Couture P., Archer W.R., Bergeron N., Lamarche B. Endothelial lipase is associated with inflammation in humans. J. Lipid Res. 2006;47:2808–2813. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P600002-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strauss J.G., Hayn M., Zechner R., Levak-Frank S., Frank S. Fatty acids liberated from high-density lipoprotein phospholipids by endothelial-derived lipase are incorporated into lipids in HepG2 cells. Biochem. J. 2003;371:981–988. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kennedy E.P., Weiss S.B. The function of cytidine coenzymes in the biosynthesis of phospholipides. J. Biol. Chem. 1956;222:193–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lands W.E. Metabolism of glycerolipides; a comparison of lecithin and triglyceride synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1958;231:883–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shindou H., Shimizu T. Acyl-CoA:lysophospholipid acyltransferases. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:1–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800046200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yen C.L., Stone S.J., Koliwad S., Harris C., Farese R.V., Jr. Thematic review series: glycerolipids. DGAT enzymes and triacylglycerol biosynthesis. J. Lipid Res. 2008;49:2283–2301. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800018-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zimmermann R., Strauss J.G., Haemmerle G., Schoiswohl G., Birner-Gruenberger R., Riederer M., Lass A., Neuberger G., Eisenhaber F., Hermetter A., Zechner R. Fat mobilization in adipose tissue is promoted by adipose triglyceride lipase. Science. 2004;306:1383–1386. doi: 10.1126/science.1100747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pritchard P.H., Vance D.E. Choline metabolism and phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis in cultured rat hepatocytes. Biochem. J. 1981;196:261–267. doi: 10.1042/bj1960261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bligh E.G., Dyer W.J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartler J., Trotzmuller M., Chitraju C., Spener F., Kofeler H.C., Thallinger G.G. Lipid data analyzer: unattended identification and quantitation of lipids in LC–MS data. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:572–577. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lowry O.H., Rosebrough N.J., Farr A.L., Randall R.J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yasuda T., Ishida T., Rader D.J. Update on the role of endothelial lipase in high-density lipoprotein metabolism, reverse cholesterol transport, and atherosclerosis. Circ. J. 2010;74:2263–2270. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-0934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nijstad N., Wiersma H., Gautier T., van der Giet M., Maugeais C., Tietge U.J. Scavenger receptor BI-mediated selective uptake is required for the remodeling of high density lipoprotein by endothelial lipase. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:6093–6100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807683200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boggs K.P., Rock C.O., Jackowski S. Lysophosphatidylcholine and 1-O-octadecyl-2-O-methyl-rac-glycero-3-phosphocholine inhibit the CDP-choline pathway of phosphatidylcholine synthesis at the CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase step. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:7757–7764. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stoll L.L., Oskarsson H.J., Spector A.A. Interaction of lysophosphatidylcholine with aortic endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. 1992;262:H1853–1860. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.6.H1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pluckthun A., Dennis E.A. Acyl and phosphoryl migration in lysophospholipids: importance in phospholipid synthesis and phospholipase specificity. Biochemistry. 1982;21:1743–1750. doi: 10.1021/bi00537a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carter J.M., Demizieux L., Campenot R.B., Vance D.E., Vance J.E. Phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis via CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase 2 facilitates neurite outgrowth and branching. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:202–212. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706531200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Phospholipase activity and expression levels of EL in EL- and LacZ-Ad infected HAEC.

HAEC were plated in 12-well dishes and infected with LacZ- or EL-Ad at MOI 50. 24 h after infection cells were washed with PBS and A) incubated with 300 μl of serum-free media supplemented with 10 U/ml of heparin for 30 min. The heparin-release media were tested for phospholipase activity. The activity was expressed as cpm/mg cell protein. Results shown are mean ± SD of two experiments performed in triplicates.

B) After washing with PBS, cells were collected in 200 μl/well of loading buffer [20% (w/v) glycerol, 5% (w/v) SDS, 0.15% (w/v) bromophenol blue, 63 mmol/I Tris–HCl, pH 6.8, and 5% (v/v) ß-mercaptoethanol] boiled for 10 min., followed by SDS-PAGE (10% gel) and subsequent immunoblotting using anti-EL antiserum.

Impact of EL overexpression on the content of HDL-PC and -PE species.

Following incubation in serum-free medium for 3 h, LacZ and EL-overexpressing HAEC were incubated in serum-free medium supplemented with 300 μg/ml HDL for 5 h. Subsequently, A) PC- and C) PE-content/profile of incubation media and B) PC- and D) PE-content/profile of re-isolated HDL were determined by MS. Results shown are mean ± SD of two representative experiments out of four performed in triplicates.

Impact of EL overexpression on the content of cellular PC and PE species.

Following incubation in serum-free medium for 3 h, LacZ and EL-overexpressing HAEC were incubated in serum-free medium supplemented with 300 μg/ml HDL for 5 h. Subsequently, A) PC- and B) PE-content/profile was determined in lipid extracts of cell layers using mass spectrometry. Results represent the mean of triplicate determinations ± SD of a representative experiment performed 6 times.

Impact of EL overexpression on the content of cellular PC and PE species in the absence of HDL.

LacZ and EL-overexpressing HAEC were incubated in serum-free medium for 8 h. Subsequently, the cellular contents of A) total PC, B) various PC species, C) total PE and D) various PE species were determined by MS. Results shown are the mean of triplicate determinations ± SD of two experiments.

PC- and PE-content/profile of HDL3.

A) PC- and B) PE-content/profile of HDL3 determined by MS.

Impact of EL overexpression on the TG profile in HAEC.

Impact of EL overexpression on the TG profile in mouse liver.