Background: The Oscillatoria agardhii agglutinin homolog (OAAH) proteins constitute a novel lectin family.

Results: Three-dimensional structures, carbohydrate binding specificities, and antiviral activity data for several members were determined.

Conclusion: All members display potent anti-HIV activity.

Significance: Our results uncovered the structural basis of protein-carbohydrate recognition in this novel lectin family and provide insights into the molecular basis of their HIV inactivation properties.

Keywords: Carbohydrate-binding Protein, HIV, NMR, Protein Complexes, X-ray Crystallography, Cyanovirin-N, MBHA, OAA, Oscillatoria agardhii, PFA

Abstract

Oscillatoria agardhii agglutinin homolog (OAAH) proteins belong to a recently discovered lectin family. All members contain a sequence repeat of ∼66 amino acids, with the number of repeats varying among different family members. Apart from data for the founding member OAA, neither three-dimensional structures, information about carbohydrate binding specificities, nor antiviral activity data have been available up to now for any other members of the OAAH family. To elucidate the structural basis for the antiviral mechanism of OAAHs, we determined the crystal structures of Pseudomonas fluorescens and Myxococcus xanthus lectins. Both proteins exhibit the same fold, resembling the founding family member, OAA, with minor differences in loop conformations. Carbohydrate binding studies by NMR and x-ray structures of glycan-lectin complexes reveal that the number of sugar binding sites corresponds to the number of sequence repeats in each protein. As for OAA, tight and specific binding to α3,α6-mannopentaose was observed. All the OAAH proteins described here exhibit potent anti-HIV activity at comparable levels. Altogether, our results provide structural details of the protein-carbohydrate interaction for this novel lectin family and insights into the molecular basis of their HIV inactivation properties.

Introduction

The development of carbohydrate-binding proteins (lectins) as microbicidal drugs represents a novel therapeutic approach in the fight against HIV transmission (1–3). This strategy is particularly useful for women in some regions of the world where social and psychological barriers are substantial and not easily overcome. For example, due to economic and societal pressures, diagnosis and treatment for HIV infections may not be readily available or are stigmatized. Therefore, using microbicides designed to significantly reduce transmission of sexually transmitted viral pathogens when applied topically to genital mucosal surfaces is potentially a powerful strategy given that application in cream form is discreet and can be completely controlled by women.

One of several lectins that were selected as a candidate for lectin-based microbicides is cyanovirin-N (CV-N)2 (4–6). It exhibits potent antiviral activity by blocking virus entry into the host target cells through specific and tight binding to Manα(1–2)Man-linked mannose substructures (7–12), in particular the D1 or D3 arms of the remarkably enriched high mannose N-linked glycans, present on the HIV envelope glycoprotein 120 (gp120), thereby compromising the required conformational changes in gp120/gp41 for fusion with the target cell membrane. Following the discovery of CV-N, there have been a growing number of lectins that are also known to bind to the high mannose glycans on gp120, such as DC-SIGN (13), a dendritic cell surface receptor that captures HIV-1 and facilitates infection of HIV-1 permissive cells in trans by endocytosis (14), as well as a variety of cyanobacteria- or actinomycetes-derived proteins like Scytovirin (15), Griffithsin (16), MVL (17), and Actinohivin (18). Notably, the target epitopes on Man-8/9 and binding modes for these different lectins are quite distinct (7, 10, 19–22). In an effort to characterize as many possible mannose-targeting lectins structurally, as well as with respect to their recognition epitopes, we recently investigated a novel antiviral lectin from the cyanobacterium Oscillatoria agardhii (named O. agardhii agglutinin; OAA) (23, 24). Surprisingly, the compact, β-barrel-like architecture of OAA is very different from previously characterized lectin structures and unique among all available protein structures in the Protein Data Bank. Most importantly, so far the OAA carbohydrate recognition of Man-9 is also unique when compared with all other anti-viral lectins. Although most of the known HIV-inactivating lectins recognize the reducing or nonreducing end mannoses of Man-8/9, OAA recognizes the branched core unit of Man-8/9.

Genes coding for OAA homologous proteins have recently been discovered in a number of other prokaryotic microorganisms, including cyanobacteria, proteobacteria, and chlorobacteria, as well as in an eukaryotic marine red alga (25). Similar to OAA, these proteins, termed OAAHs, contain a sequence repeat of ∼66 amino acids, with the number of repeats varying for different family members. For example, the 133-residue-containing Pseudomonas fluorescens and Herpetosiphon aurantiacus homologs contain two sequence repeats, like OAA, whereas Lyngbya sp., Burkholderia oklahomensis EO147, Stigmatella aurantiaca DW4/3-1, Myxococcus xanthus, and Eucheuma serra homologs contain four sequence repeats over lengths of 246–268 residues (25).

Apart from data for the founding member OAA, neither three-dimensional structures, information about carbohydrate binding specificities, nor antiviral activity have been available up to now for any other member of the OAAH family. To further characterize this important lectin family, we carried out structural analyses of two additional members of the OAAH family. We determined the structures of the P. fluorescens and the M. xanthus OAAHs that contain two and four sequence repeats, respectively. We delineated the conserved sequence and structure features in these proteins and determined their sugar binding specificities by NMR titrations and x-ray crystallography. In addition, HIV assays were carried out, and we observed that the antiviral potency for all OAAH family members investigated here is comparable and is not significantly enhanced when more binding sites are present. Altogether, our results provide the basis for expanding our knowledge with respect to protein-carbohydrate interaction in general and recognition of α3,α6-mannopentaose by this class of lectins in particular.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Expression, Purification, and Crystallization

PFA and MBHA were expressed and purified as described previously for OAA (23). Briefly, synthetic PFA and MBHA genes encoding residues 1–133 and 1–267 (25) were cloned into the pET-26b(+) expression vector (Novagen), using NdeI and XhoI restriction sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. Escherichia coli Rosetta2 (DE3) cells (Novagen) were transformed with the pET-26b(+)-PFA or the pET-26B(+)-MBHA vector for protein expression. Cells were initially grown at 37 °C, induced with 1 mm isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside, and grown for ∼18 h at 16 °C for protein expression.

The hybrid OAAH protein (OPA) was created by combining the OAA and PFA genes via a six-nucleotide linker encoding N-G residues, thus generating a 267-residue chimera. Individual DNA fragments encoding residues Met1 to Thr133 of OAA (PCR1) and residues Ser2 to Glu133 of OAA (PCR2) were amplified using the parent vectors as templates. PCR1 (amplification of OAA) utilized oligonucleotides 5′-GCGAAATTAATACGACT-CACTATAGGGG-3′ (T7 promoter) as forward and 5′-CCGCATATTTGCTACCGTTCGTCAGGGTACCTTTGAAGCCGATC-3′ (R1) as reverse primers. Note that the first 13 (italic), the ACCGTT (bolded), and the last 25 (underlined) nucleotides in the reverse primer (R1) are nucleotides that code for the first few N-terminal residues of PFA, the N-G linker residues, and the last few C-terminal residues of OAA. PCR2 (amplification of PFA) was performed with the oligonucleotides 5′-GGTACCCTGACGAACGGTAGCAAATATGCGGTGGCCAACCAGTG-3′ as forward (F2) and 5′-CAAAAAACCCCTCAAGACCCGTTTAGAG-3′ (T7 terminator) as reverse primers. For PCR2, the first 12 nucleotides (underlined), the ACCGTT (bolded), and the last 26 (italic) nucleotides in the forward primer (F2) are nucleotides that encode for the last few C-terminal residues of OAA, the N-G linker residues, and the first few N-terminal residues of PFA. PCR3, as the final step, was performed after mixing equal amounts of these two PCR products and amplifying with T7 promoter and T7 terminator primers, respectively. Once the complete DNA fragment encoding the full-length OPA was generated, the fragment was cloned into the pET-26b(+) expression vector (Novagen), using NdeI and XhoI restriction sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. E. coli Rosetta2 (DE3) cells (Novagen) were transformed with the pET-26b(+)-OPA vector for protein expression. As for PFA and MBHA, cells were initially grown at 37 °C, induced with 1 mm isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside, and grown for ∼18 h at 16 °C for protein expression.

Protein was prepared from the soluble fraction after rupturing the cells by sonication. The cell lysate was centrifuged to remove cell debris and, after centrifugation, the supernatant was dialyzed overnight against 20 mm Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.5) for OPA and against 20 mm sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0) for PFA and MBHA. The first purification step involved anion-exchange chromatography on a Q(HP) column (GE Healthcare) for OPA and an SP(HP) column (GE Healthcare) for PFA and MBHA, using a linear gradient of NaCl (0–1000 mm) for elution. Protein-containing fractions were concentrated and further purified by gel filtration on a Superdex 75 column (GE Healthcare) in 20 mm Tris-HCl buffer, 100 mm NaCl, 3 mm NaN3, (pH 8.0). The final purification involved another step of anion-exchange chromatography on a Q(HP) column (GE Healthcare) for OPA or an SP(HP) column (GE Healthcare) for PFA and MBHA. Fractions containing pure protein were collected and concentrated up to 40 mg/ml using Centriprep devices (Millipore). For crystallization and NMR, the buffer was exchanged to 20 mm Tris-HCl buffer, 100 mm NaCl, 3 mm NaN3, (pH 8.0) and to 20 mm sodium acetate, 3 mm NaN3, 90/10% H2O/D2O (pH 5.0), respectively.

Crystallization trials of apoPFA and apoMBHA were carried out by the sitting drop vapor diffusion at room temperature using drops consisting of 2 μl of protein and 2 μl of reservoir solutions at a protein concentration of 40 mg/ml. Well diffracting crystals were obtained in 1.0 m sodium citrate and 0.1 m imidazole (pH 8.0) for PFA and in 0.2 m ammonium sulfate, 0.1 m sodium cacodylate trihydrate (pH 6.5), and 30% polyethylene glycol 8000 for MBHA after ∼1 week. The crystals for the carbohydrate-bound MBHA were obtained by co-crystallization. Drops consisted of 2 μl of reservoir solution and 2 μl of premixed protein and α3,α6-mannopentaose at a molar ratio of 1:6, with the protein concentration at 30 mg/ml. Well diffracting crystals of α3,α6-mannopentaose-bound MBHA were obtained using 0.05 m monobasic potassium phosphate and 20% w/v polyethylene glycol 3350.

Diffraction Data Collection and Structure Determination of apoPFA, apoMBHA, and glycan-bound MBHA

X-ray diffraction data for apoPFA, apoMBHA, and glycan-bound MBHA crystals were collected up to 1.70, 1.60, and 1.76 Å resolution, respectively, on flash-cooled crystals (−180 °C) using a Rigaku FR-E generator with a Saturn 944 CCD detector or an R-AXIS IV image plate detector at a wavelength corresponding to the copper edge (1.54 Å). All diffraction data were processed, integrated, and scaled using d*TREK software (26), and eventually converted to mtz format using the CCP4 package (27). The unit cell dimensions of the C2 apoPFA crystal were a = 58.95 Å, b = 70.31 Å, and c = 62.29 Å (β = 111.73°) with an estimated solvent content of 42.52% (Vm = 2.14 Å3/Da), based on the Matthews Probability Calculator. The crystals contained two PFA molecules per asymmetric unit. The unit cell dimensions of the P31 apo and the P212121 α3,α6-mannopentaose-bound MBHA crystals were a = 76.10 Å, b = 76.10 Å, and c = 37.67 Å (γ = 120°) and a = 45.59 Å, b = 57.32 Å, and c = 105.97 Å (α, β, and γ = 90°) with an estimated solvent content of 45.48% (Vm = 2.26 Å3/Da) and 50.37% (Vm = 2.48 Å3/Da), respectively. Both crystals contained one polypeptide molecule per asymmetric unit.

Phases for both apoPFA and apoMBHA crystals were determined by molecular replacement using the previously determined structure of OAA (Protein Data Bank (PDB): 3S5V) (23, 24) as structural probe in PHASER (28). After generation of the initial model, the chain was rebuilt using the program Coot (29). Iterative refinement was carried out by alternating between manual rebuilding in Coot (29) and automated refinement in REFMAC (30). Similar procedures were adopted for the diffraction data collected from the complex MBHA crystal. In the latter case, the structure obtained from the apoMBHA protein was used as the structural probe for molecular replacement.

All final models exhibit clear electron density for all residues (2–133 and 2–267 for PFA and MBHA, respectively). Note that the first residue (Met1) was completely removed by the E. coli N-terminal methionine aminopeptidase during protein expression (verified by NMR and mass spectrometry). The final apoPFA structure is well defined to 1.70 Å resolution with an R-factor of 17.6% and a free R of 21.5%. 98.9 and 100% of all residues are located in the favored and allowed regions of the Ramachandran plot, respectively, and no residues are in the disallowed region as evaluated by MOLPROBITY (31). Similarly, the final apoMBHA structure was well defined to 1.60 Å resolution with an R-factor of 17.8% and a free R of 21.2%. 97.4 and 100% of all residues are located in the favored and allowed regions of the Ramachandran plot, respectively, and no residues are in the disallowed region as evaluated by MOLPROBITY (31). In the MBHA-α3,α6-mannopentaose complex crystals, additional electron density was present only in the two carbohydrate binding sites of the second barrel of MBHA. The extra density in both sites permitted fitting of an α3,α6-mannopentaose molecule into each binding site. The final complex structure is well refined with an R-factor of 18.6% and a free R of 22.4%. 98.5 and 100% of all residues lie in the favored and allowed regions of the Ramachandran plot, respectively. A summary of the data collection parameters, as well as pertinent structural statistics for all structures, is provided in Table 1. All structural figures were generated with Chimera (32) or PyMOL (33).

TABLE 1.

PFA and MBHA data collection, refinement, and Ramachandran statistics

| apoPFAa,b,c | apoMBHAa,b,c | MBHA complexa,c | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||

| Space group | C2 | P31 | P212121 |

| Cell dimensions | |||

| a, b, c (Å) | 58.95/70.31/62.29 | 76.10/76.10/37.67 | 45.59/57.32/105.97 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90/111.73/90 | 90/90/120 | 90/90/90 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.5418 | 1.5418 | 1.5418 |

| Resolution (Å) | 28.14-1.70 (1.76-1.70)d | 32.95-1.60 (1.66-1.60)d | 33.82-1.76 (1.82-1.76)d |

| Rmerge | 0.038 (0.294)d | 0.116 (0.430)d | 0.053 (0.206)d |

| Rmeas | 0.052 (0.403)d | 0.124 (0.491)d | 0.057 (0.253)d |

| I/σI | 12.6 (2.4)d | 10.6 (1.7)d | 22.1 (3.8)d |

| Completeness (%) | 93.8 (90.6)d | 97.0 (88.8)d | 96.8. (81.5)d |

| Redundancy | 1.91 (1.90)d | 6.49 (3.65)d | 6.63 (2.53)d |

| Refinement | |||

| Resolution (Å) | 28.14-1.70 (1.74-1.70)d | 32.95-1.60 (1.64-1.60)d | 33.82-1.76 (1.81-1.76)d |

| No. of reflections | 22,452 | 28,106 | 25,993 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.176/0.215 (0.276/0.327)d | 0.178/0.212 (0.240/0.287)d | 0.186/0.214 (0.224/0.315)d |

| No. of atoms | |||

| Protein | 1,970 | 1,990 | 1,998 |

| Ligand/ion | 128 | ||

| Water | 312 | 243 | 197 |

| B-factors | |||

| Protein | 37.61 | 28.96 | 23.30 |

| Ligand/ion | 28.45 | ||

| Water | 45.66 | 36.95 | 31.97 |

| r.m.s deviations | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.012 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.343 | 1.396 | 1.400 |

| Ramachandrane | |||

| Favored region | 98.9 | 97.4 | 98.5 |

| Allowed region | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

a Data were obtained from the best diffracting crystal according to crystallization condition (see “Experimental Procedures” for details).

b Crystallographic phases were obtained by molecular replacement using the previously determined structure of OAA in orthorhombic P212121 space group (PDB: 3S5V).

c Refinement was carried out using Refmac5.

d Values in parentheses are for highest resolution shell.

e Values are obtained by MolProbity (31).

Carbohydrate Binding Studies by NMR Spectroscopy

Three-dimensional NMR HNCACB and CBCA(CO)NH spectra (34) were recorded for complete backbone chemical shift assignment of apo and α3,α6-mannopentaose-bound PFA at 25 °C on a Bruker AVANCE 800 spectrometer, equipped with a 5-mm triple-resonance, z axis gradient cryoprobe. For apo and α3,α6-mannopentaose-bound MBHA, partial backbone chemical shift assignment were obtained using three-dimensional NMR TROSY-HNCACB and TROSY-CBCA(CO)NH spectra on a Bruker AVANCE 900 spectrometer, also equipped with a 5-mm triple-resonance, z axis gradient cryoprobe. All protein spectra were recorded on a 13C/15N-labeled sample in 20 mm sodium acetate, 20 mm NaCl, 3 mm NaN3, 90/10% H2O/D2O (pH 5.0). The protein concentration (∼1.0 mm) was similar in concentration to the one used for crystallization (∼40 mg/ml). All spectra were processed with NMRPipe (35) and analyzed using NMRView (36).

Binding of α3,α6-mannopentaose (Sigma-Aldrich) was investigated at 25 °C using 0.040 mm 15N-labeled PFA or MBHA or OPA in 20 mm sodium acetate, 20 mm NaCl, 3 mm NaN3, 90/10% H2O/D2O (pH 5.0) by 1H-15N HSQC spectroscopy on a Bruker AVANCE 600 or AVANCE 900 spectrometer. Two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra were recorded after each addition of carbohydrate with final molar ratios of PFA:α3,α6-mannopentaose of 1:0, 1:0.25, 1:0.5, 1:1, 1:1.5, 1:2, and 1:3 (equivalent to 1:0, 1:0.125, 1:0.25, 1:0.5, 1:0.75, 1:1, and 1:1.5 for an individual glycan binding site), final molar ratios of MBHA:α3,α6-mannopentaose of 1:0, 1:1, 1:2, 1:4, and 1:6 (equivalent to 1:0, 1:0.5, 1:1, and 1:1.5 for an individual glycan binding site), and final molar ratios of OPA:α3,α6-mannopentaose of 1:0, 1:1, 1:2, and 1:4 (equivalent to 1:0, 1:0.5, and 1:1 for an individual glycan binding site).

Anti-HIV Assay

HIV viral activity assays were performed using TZM-bl (37) cells cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing fetal bovine serum (10%), penicillin, and streptomycin. Cells were seeded at 10,000/well in a 96-well plate in 100-μl volumes of media 16 h before inoculation. Wild type HIV-1 (1 ng of p24/well), produced by transfection of 293T cells with the R9 proviral clone, was used for infection. This dose of virus was selected to keep the infection below saturation, ensuring linearity in the assay. 16 h after of seeding of TZM-bl cells, the medium was aspirated, and 100 μl of medium containing virus and antiviral proteins was added to the cultures, supplemented with DEAE-dextran (20 μg/ml). All samples were carried out as duplicates. Cultures were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C, after which 100 μl of Steady-Glo luciferase substrate (Promega) was added to each well. Plates were incubated at room temperature for 5 min, and luminescence was quantified by TopCount NXTTM (Packard Bioscience). The readout is relative luminescence units, which is directly proportional to infectivity. Values are expressed relative to the control cultures lacking antiviral protein. Antiviral potency was determined as the concentration of the inhibitor required for 50% inhibition of infection (IC50) and was extracted manually based on the nonlinear regression algorithm produced in KaleidaGraph.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Structures of PFA and MBHA

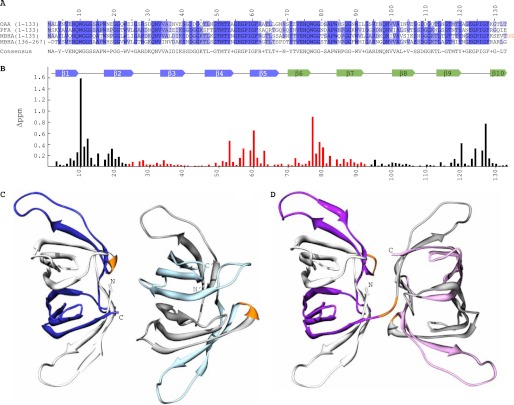

The amino acid sequences of the P. fluorescens and M. xanthus lectins, designated as PFA and MBHA throughout this study, possess extensive sequence similarity to OAA, with ∼62% identity for pairwise alignment (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, the majority of the amino acid conservation resides in the carbohydrate binding regions, delineated previously in OAA (Fig. 1B). This region encompasses the loops between β1-β2, β7-β8, and β9-β10 in the first binding site and between β6-β7, β2-β3, and β4-β5 in the second binding site. In addition, notable sequence conservation is seen throughout the secondary structure elements, with residues Tyr4 and Val6 in β1, Trp17, Gly20, Gly21, and Trp23 in β2, Val34 and Ala35 in β3, Gly49, Thr50, Met51, Thr52, and Tyr53 in β4, Ile59, Gly60, and Phe61 in β5, Tyr71, Val73, Glu74, Asn75, and Gln76 in β6, Trp84, Gly87, Gly88, and Trp90 in β7, Ala102 in β8, Leu114, Gly116, Thr117, Thr119, and Tyr120 in β9, and Phe128 in β10 being invariant in all three sequences (all numbering refers to OAA).

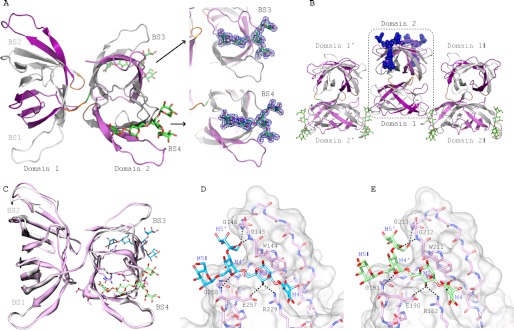

FIGURE 1.

Sequence, carbohydrate binding, and structures of OAAHs. A, amino acid sequence alignment of OAA, PFA, and MBHA. The four sequence repeats in MBHA are displayed as two separate two-sequence stretches. Conserved and similar residues are colored in blue and slate, respectively. The two-residue linker connecting the two domains of MBHA is colored in orange. B, secondary structure and chemical shift perturbation profile (combined amide chemical shift changes) of OAA at the final titration point (1:3 molar ratio of OAA to α3,α6-mannopentaose). Values were calculated using the equation: Δppm = ((Δppm (1HN))2 + (Δppm (15N)/5)2)1/2. C and D, ribbon representation of the backbone structures of PFA and MBHA, respectively. The five β-strands in the first and second sequence repeats in PFA are colored in white and blue and in gray and light blue for molecule one and two, respectively, in the asymmetric unit. For MBHA, the five β-strands in the first and second sequence repeats in the first and second domains are colored in white and purple and in gray and light magenta, respectively. The connecting residues between the repeats (between strands β5 and β6) in both proteins and between the first and second domains in MBHA are colored in orange.

PFA assembles into a single, compact, β-barrel-like domain as observed previously for OAA (Fig. 1C). Each sequence repeat folds up into five β-strands, denoted as β1 to β5 (colored in white) and β6 to β10 (colored in blue) for the first and second repeats of the first molecule in the asymmetric unit, respectively. For the second molecule in the asymmetric unit, the first and second five β-strands are colored in gray and light blue, respectively. A very short linker, comprising residues Gly67–Asn69, connects the two-sequence repeats (colored in orange) in both molecules. Note that the two individual PFA molecules in the asymmetric unit are essentially identical with root mean square deviation (r.m.s.d.) values for backbone and heavy atoms (residues Ser2 to Ile132) of 0.49 and 0.90 Å, respectively.

Unlike OAA or PFA, MBHA contains four sequence repeats, and in its crystal structure, each two-sequence repeat folds into a β-barrel, resulting in a tandem arrangement of two barrels (Fig. 1D). The first barrel is composed of the first 10 β-strands, colored in white and purple, and the second barrel is made up by the second 10 β-strands, colored in gray and light magenta, respectively. Three short linkers comprising residues Ser67–Asn69, Thr133–Gly135, and Ser201–Asp203 connect the first and second five β-strands, the first and second barrels, and the third and fourth five β-strands, respectively. The structures of the first (residues Ala2 to Val132) and second (residues Asp136 to Leu266) barrels of MBHA are alike, with a backbone atom r.m.s.d value of 0.63 Å. In comparing the relative orientations of the two molecules of PFA and the two tandem domains of MBHA, it should be noted that they are quite different (Fig. 1, C and D), with an almost 180° flip of the second molecule/domain (Fig. 1, C and D, right side) relative to the first one (Fig. 1, C and D, left side).

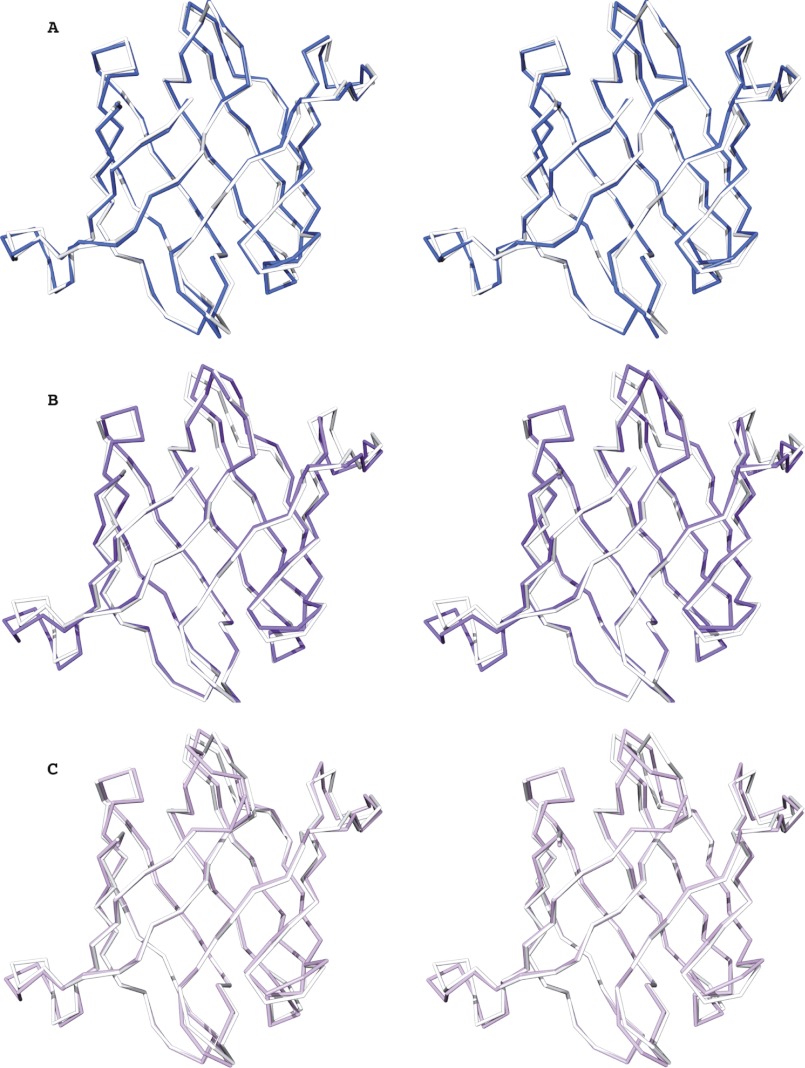

Comparison of the overall structures of these new family members with that of the founding member, OAA, also revealed a close resemblance. The overall r.m.s.d values for backbone atoms between OAA (residues Ala2 to Leu132) and PFA (residues Ser2 to Ile132) is 0.50 Å (Fig. 2A), between OAA (residues Ala2 to Leu132) and the first domain of MBHA (residues Ala2 to Val132) it is 0.79 Å (Fig. 2B), and between OAA (residues Ala2 to Leu132) and the second domain of MBHA (residues Asp136 to Leu266), it is 0.70 Å (Fig. 2C). Similarly, PFA is also similar to each of the MBHA domains with backbone atom r.m.s.d. values of 0.74 Å between PFA and the first domain (residues Ser2 to Ile132 of PFA and residues Ala2 to Val132 of MBHA) and 0.60 Å between PFA and the second domain of MBHA (residues Ser2 to Ile132 of PFA and residues Asp136 to Leu266 of MBHA). This extensive structural similarity parallels the significant degree of amino acid identity throughout the protein sequences (Fig. 1A). It is worth pointing out, however, that some conformational differences are observed in the loop regions connecting β1-β2, β5-β6, and β6-β7 for OAA and PFA, the loop regions connecting β1-β2, β4-β5, β5-β6, and β6-β7 for OAA and the first barrel of MBHA, and the loop regions connecting strands β1-β2, β2-β3, β4-β5, β5-β6, β6-β7 and β7-β8 for OAA and the second barrel of MBHA (Fig. 2). Given that the amino acids around these loops are highly conserved (Fig. 1A) and previous relaxation studies on OAA revealed that these regions are flexible, these minor conformational differences most likely arise from differences in crystal packing among these proteins.

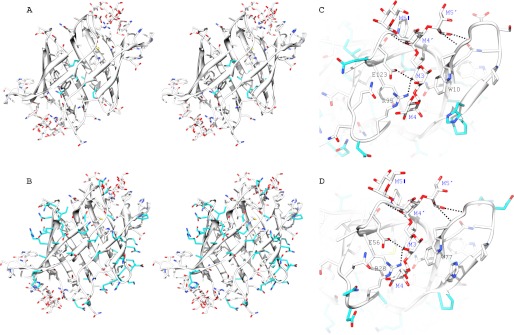

FIGURE 2.

Conservation of the OAAH fold. A–C, stereo views of best-fit Cα superpositions of OAA and PFA (A), OAA and the first domain of MBHA (B), and OAA and the second domain of MBHA (C), respectively. OAA, PFA, and the first and second domains of MBHA are colored in white, blue, purple, and light magenta, respectively.

PFA and MBHA Strongly and Specifically Bind to α3,α6-Mannopentaose in Solution

The OAA anti-HIV activity is associated with its binding to N-linked high mannose glycans on the viral envelope glycoprotein gp120 (23, 38). The epitope that is recognized by OAA on Man-8/9 is α3,α6-mannopentaose (Manα(1–3)[Manα(1–3)[Manα(1–6)]Manα(1–6)] Man), the branched core unit of the triantennary high mannose structures (24). Note that the binding affinity for each binding site in OAA for this ligand is very similar (∼<10 μm). To evaluate whether the same or different carbohydrate specificities are exhibited by the two new OAAH family members, we carried out titrations with α3,α6-mannopentaose and monitored the chemical shift perturbations by 1H-15N HSQC spectroscopy.

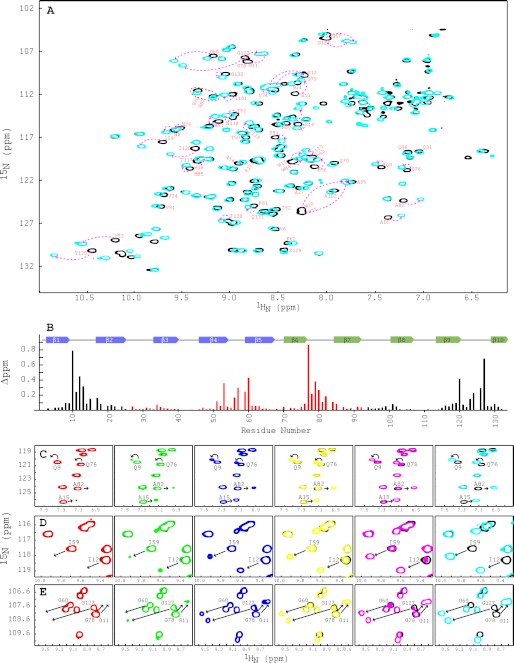

The two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra of apo and glycan-bound PFA exhibit well dispersed and narrow resonances, as expected for a well folded protein (Fig. 3A). All expected amide backbone resonances are observed, and complete backbone assignments for free and bound PFA were obtained from three-dimensional HNCACB and HN(CO)CACB spectra. Similar to OAA, α3,α6-mannopentaose binding to PFA is in slow exchange on the NMR chemical shift scale, suggesting a relatively tight interaction.

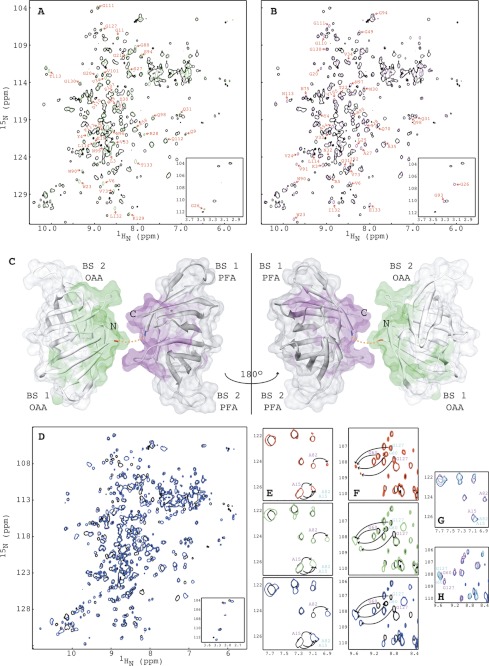

FIGURE 3.

NMR titrations of PFA with α3,α6-mannopentaose. A, superposition of the two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra of free (black) and α3,α6-mannopentaose-bound (cyan) PFA at 1:3 molar ratio of PFA to sugar. Selected resonances that exhibit large chemical shift changes are labeled by amino acid type and number. Note that the amide resonances of Gly26 and Gly93 are significantly upfield shifted in their proton frequencies and not within the current spectral boundaries. B, secondary structure and chemical shift perturbation profile of combined amide chemical shift changes for PFA at the final titration point (PFA:α3,α6-mannopentaose = 1:3). Values were calculated using the equation; Δppm = ((Δppm (1HN))2 + (Δppm (15N)/5)2)1/2. C–E, superposition of selected regions in the two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra of free (black) and α3,α6-mannopentaose bound PFA at 1:0.25 (red), 1:0.50 (green), 1:1 (blue), 1:1.5 (yellow), 1:2 (magenta), and 1:3 (cyan) molar ratios of PFA to sugar for residues Ala15/Ala82 and Gln9/Gln76 (C), residues Ile59/Ile126 (D), and residues Gly60/Gly127 and Gly11/Gly78 (E). All spectra are plotted at the same contour level, and all titrations were carried out using 0.040 mm PFA in 20 mm sodium acetate, 20 mm NaCl, 3 mm NaN3, 90/10% H2O/D2O (pH 5.0), 25 °C.

Chemical shift differences between free PFA and sugar-bound resonances at saturation (protein:sugar molar ratio of 1:3) are displayed along the polypeptide chain in Fig. 3B. As can be appreciated, the most strongly affected residues are located in the loops, connecting strands β1-β2 and β9-β10 (site 1, black bars) and between strands β4-β5 and β6-β7 (site 2, red bars), respectively. Smaller changes are seen for the loops connecting β7-β8 (site 1, black bars) and β2-β3 (site 2, red bars). Resonances with chemical shift differences of >0.08 ppm (approximately more than one times average value) include residues Asn8–Ser14, Trp17–His18, Ile101, Asn118–Tyr120, Glu123–Gly124, Ile126–Gly127, and Gly130 in the first binding site and residues Met51, Tyr53, Glu56–Gly57, Ile59–Gly60, Gln76–Ala82, and Trp84–His85 in the second binding site. These amino acids are equivalent to those in OAA that were perturbed by the addition of the same sugar (24). Therefore, the binding sites in both proteins are located in corresponding regions of the structures, consistent with the extensive sequence conservation in these sites.

Interestingly, our titration experiments revealed a clear difference in carbohydrate affinity between the two binding sites in PFA. As can be observed in the titration data, for increasing protein-α3,α6-mannopentaose molar ratios, starting with 1:0 (free protein, black), via 1:0.25 (red), 1:0.5 (green), 1:1 (blue), 1:1.5 (yellow), 1:2 (magenta), to 1:3 (cyan), the amide resonances of residues Gln9 and Ala15 (Fig. 3C), residue Ile126 (Fig. 3D), and residues Gly11 and Gly127 (Fig. 3E), which are all located in binding site 1, are perturbed earlier than the corresponding resonances of residues in binding site 2 (residues Gln76 and Ala82 (Fig. 3C), residue Ile59 (Fig. 3D), and residues Gly78 and Gly60 (Fig. 3E)). However, both binding sites are completely saturated at a protein-to-α3,α6-mannopentaose molar ratio of 1:3, suggesting that the affinity for binding site 1 is ∼1.5-fold tighter than that for binding site 2. This is different from our findings with OAA, where both binding sites exhibited essentially indistinguishable affinity (24). It may be tempting to speculate that the difference in affinity is related to the slight difference in conformation, in particular considering the loop regions connecting strands β1-β2 in site 1 and β6-β7 in site 2. However, given that these loop regions are flexible in the apo form in solution and influenced by crystal packing, we cannot with any certainty draw this conclusion. We believe that it is more likely that the amino acid differences between the two sites in PFA (24 differences in 65 amino acids) when compared with those in OAA (14 differences in 65 amino acids) play a role. Note that the sugar titrations for both proteins were carried out with identical protein concentrations (40 μm), using the same buffer conditions, the same stock of glycan solution, the same spectrometer, and performed on the same day. Therefore, even small differences can be reliably quantified.

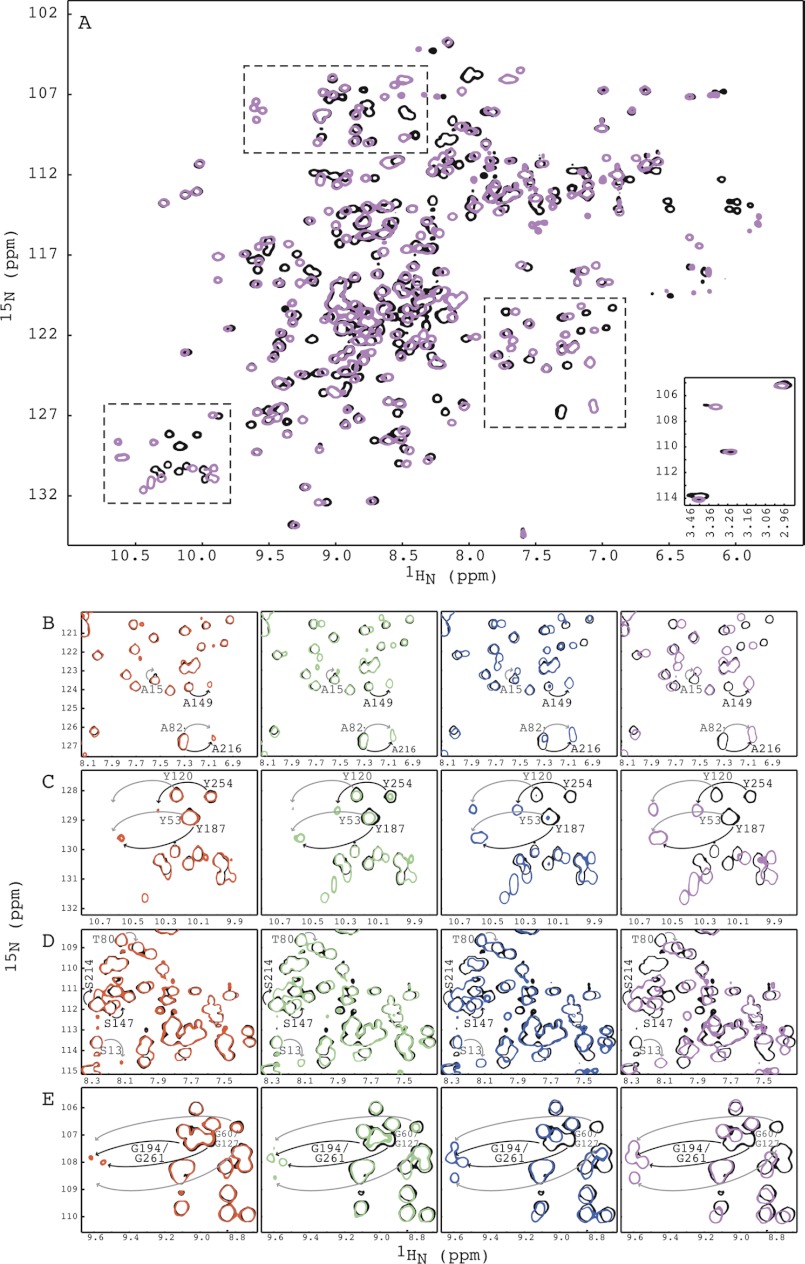

We also carried out carbohydrate binding studies by NMR titration experiments for MBHA. The two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra of apo (black) and α3,α6-mannopentaose-bound (magenta) MBHA are well dispersed, indicative of a well folded structure (Fig. 4A). Because MBHA contains twice the number of amino acids, i.e. double the number of resonances, overlap of backbone amide resonances and Cα and Cβ chemical shift degeneracy permitted only partial backbone assignment using three-dimensional TROSY-HNCACB and TROSY-HN(CO)CACB spectra. We were, however, successful in obtaining unambiguous assignments for the important loop regions because enough differences in sequences are present. For example, the stretch Ser13-Gln14-Ala15-Thr16 (repeat 1 in domain 1) corresponds to Thr80-Ser81-Ala82-Pro83 (repeat 2 in domain 1), Ser147-Ala148-Ala149-Pro150 (repeat 3 in domain 2), and Ser214-Thr215-Ala216-Pro217 (repeat 4 in domain 2). In addition, our previous experience with the carbohydrate binding of OAA and PFA also aided in the assignment process for this 28-kDa protein.

FIGURE 4.

NMR titrations of MBHA with α3,α6-mannopentaose. A, superposition of the two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra of free (black) and α3,α6-mannopentaose-bound MBHA at 1:6 molar ratio (magenta) of MBHA to α3,α6-mannopentaose. The four amide resonances of MBHA that correspond to Gly26 and Gly93 in OAA or PFA are displayed in the bottom inset. Three selected regions that are discussed under “Results” are indicated by dashed boxes. B–E, superposition of selected regions of the two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra of free (black) and α3,α6-mannopentaose bound MBHA at 1:1 (red), 1:2 (green), 1:4 (blue), and 1:6 (magenta) molar ratios of MBHA to sugar for residues Ala15/Ala82/Ala149/Ala216 (B), residues Tyr53/Tyr120/Tyr187/Tyr257 (C), residues Ser13/Thr80/Ser147/Ser214 (D), and residues Gly60/Gly127/Gly194/Gly261 (E). All spectra are plotted at the same contour level, and all titrations were carried out using 0.100 mm MBHA in 20 mm sodium acetate, 20 mm NaCl, 3 mm NaN3, 90/10% H2O/D2O (pH 5.0), 25 °C.

As for OAA and PFA, binding between MBHA and α3,α6-mannopentaose is in slow exchange on the NMR chemical shift scale, and complete saturation of all resonances of MBHA was obtained at a protein:sugar molar ratio of 1:6 (Fig. 4A), consistent with four sugar binding sites per polypeptide chain. Two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra of the protein with increasing amounts of α3,α6-mannopentaose at molar ratios of 1:0 (free protein, black), 1:1 (red), 1:2 (green), 1:4 (blue), and 1:6 (magenta) are displayed in Fig. 4.

Again, the titration experiments resulted in several interesting findings. First, as expected, MBHA contains four binding sites for α3,α6-mannopentaose, as evidenced by the chemical shift changes of the amide resonances of residues Ala15, Ala82, Ala149, and Ala216, which are located in sequence repeats 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively (Fig. 4, A and B). Second, among the four binding sites, two sites exhibit tighter binding than the other two because the Ala149 and Ala216 resonances are already perturbed at the first titration point (protein:sugar molar ratio of 1:1, red), whereas the Ala15 and Ala82 resonances are not yet affected (Fig. 4B). More importantly, at a molar ratio of 1:2 (green), where each binding site should be half-saturated if identical sugar affinities were present, higher intensity for bound resonances of residues Ala149 and Ala216 when compared with those of Ala15 and Ala82 are observed, clearly suggesting tighter affinities for sites 3 and 4. Third, both higher affinity sites are located in the second barrel of MBHA (Fig. 1D). Similar observations hold for the Tyr53, Tyr120, Tyr187, and Tyr254 (Fig. 4C), Ser13, Thr80, Ser147, and Ser214 (Fig. 4D), and Gly60, Gly127, Gly194, and Gly261 (Fig. 4E) resonances. Resonances of Tyr187/Tyr254/Gly194 and Ser147/Ser214/Gly261 that belong to amino acids in sequence repeats 3 and 4, respectively, were affected earlier in the titration than their counterparts in sequence repeats 1 and 2.

Therefore, our data show that of the four carbohydrate binding sites in MBHA, those in the second domain bind carbohydrate more tightly than those in the first domain. This was somewhat unexpected given the slight differences in affinity for the sites in a single barrel OAAH lectin. However, because at most a factor of 1.5–2 is observed, this variation in affinities most likely just reflects minor variations in amino acid sequence.

Structural Basis for Carbohydrate Specificity of PFA and MBHA

Given that both PFA and MBHA strongly and specifically bind to α3,α6-mannopentaose, we aimed to crystallize the PFA- and MBHA-α3,α6-mannopentaose complexes by soaking or co-crystallization. Our attempts to soak sugar into the apo crystals were unsuccessful, and even the addition of small amounts of glycan resulted in the immediate dissolution of the PFA or MBHA crystals. This can be explained by the tight packing of the proteins in the crystal lattice, occluding the sugar binding sites. We therefore pursued co-crystallization at protein:sugar molar ratios of 1:3 and 1:6, with protein concentrations of 40 and 30 mg/ml for PFA and MBHA, respectively, in 400 different conditions.

Crystals of α3,α6-mannopentaose-bound MBHA were obtained in 0.05 m KH2PO4 and 20% w/v polyethylene glycol 3350. The protein crystallized in space group P212121, with one protein molecule per asymmetric unit. The complex structure was solved by molecular replacement using the apo structure of MBHA, comprising residues 2–267 as the structural probe in PHASER (28). The final model was refined to 1.76 Å resolution with R = 18.6% and Rfree = 21.4%.

Interestingly, the structure of α3,α6-mannopentaose-bound MBHA revealed that only the two higher affinity sites, i.e. binding sites 3 and 4 that are both located in the second domain of MBHA, are occupied by the glycan (Fig. 5A). Clear electron density at two opposing ends of this second barrel allowed for an excellent fit of the atomic structures of two α3,α6-mannopentaose molecules, one per site. No equivalent density was observed in the other two binding sites in the first domain. Further inspection of the complex structure in the crystal revealed that the carbohydrate binding regions in the first barrel are close to the bound α3,α6-mannopentaose from two neighboring molecules (Fig. 5B). Indeed, one mannose unit at the end of the site 3-bound α3,α6-mannopentaose is in close contact to residues in binding site 2 of a neighboring protein molecule, whereas the bound sugar in site 4 reaches over to site 1 of another neighboring molecule. Therefore, adjacent protein molecules in the crystal are bridged by the glycans that simultaneously contact sites 3 and 4 and 1 and 2, respectively, facilitating crystal formation. In solution, on the other hand, we know from our NMR titration data that sites 1 and 2 can bind α3,α6-mannopentaose similar to binding sites 3 and 4 (Fig. 4), albeit with slightly reduced affinity.

FIGURE 5.

Crystal structures of α3,α6-mannopentaose-bound MBHA. A, ribbon representation of α3,α6-mannopentaose-bound MBHA structure. The five β-strands from the first and second sequence repeat in the first and second domain of MBHA are colored in white and purple, and in gray and light magenta, respectively. The connecting amino acids between the sequence repeats (between strands β5 and β6 and strands β15 and β16) and between the first and second domain in MBHA are colored orange. The two bound α3,α6-mannopentaose molecules in binding sites 3 and 4, located in the second domain, are depicted in green stick representation, with oxygen atoms shown in red. The electron density contoured at 1.0σ enclosing the molecular model of α3,α6-mannopentaose (or Manα(1–3)[Manα(1–3)[Manα(1–6)]Manα(1–6)]Man pentasaccharide) in stick representation in binding sites 3 and 4 of MBHA is colored blue. B, arrangement of α3,α6-mannopentaose-bound MBHA depicting two neighboring molecules in the crystal. The color scheme and secondary structure depiction are similar to that in A. C, superposition of ligand-free and α3,α6-mannopentaose-bound MBHA structures in ribbon representation. The bound α3,α6-mannopentaose binding sites 3 and 4 are depicted in cyan and light green stick representation, with oxygen atoms shown in red. D and E, details of the interaction network between α3,α6-mannopentaose and MBHA in binding sites 3 and 4. The protein is depicted in both surface and stick representations, with the bound α3,α6-mannopentaose only in stick representation. Residues that are in direct contact with the carbohydrate are the following: Trp144, Gly145, Gly146, Arg229, Glu257, and Gly258 in binding site 3 (D) and Trp211, Gly212, Gly213, Arg162, Glu190, and Gly191 in binding site 4 (E). Intermolecular hydrogen bonds are indicated by black dashed lines. The same color scheme as in C is used for the carbohydrate. Protein residues are labeled by single-letter code, and the sugar rings of the carbohydrate are labeled according to standard nomenclature.

Not surprisingly, the structures of the apo- and α3,α6-mannopentaose-bound MBHA are very similar with backbone and heavy atom r.m.s.d. values of 0.57 and 0.93 Å, respectively (Fig. 5C), with only a minor difference in the binding site 2 loops. Therefore, within the error of the coordinates, no significant difference in the conformation of three of the four binding sites between the free and carbohydrate-bound MBHA structure can be seen.

The structure of the MBHA-α3,α6-manno-pentaose complex reveals specific contacts between MBHA side chains and the carbohydrate. As shown in Fig. 5, D and E, the aromatic side chain of Trp144 in site 3 and Trp211 in site 4 play critical roles, providing hydrophobic contacts for the pyranose ring of M3. In addition, several polar interactions are also observed. These include hydrogen bonds between the hydroxyl groups of the sugar and main chain amide groups, as well as several side chains. In binding site 3 (Fig. 5E), hydrogen bonds are formed between the backbone amide of Gly145 and the C5 hydroxyl group of M5′, the backbone amide of Gly146 and the C6 hydroxyl group of M5′, and the backbone amide of Gly258 and the C5 hydroxyl group of M4′. Side chain interactions in binding site 3 include hydrogen bonds between the C4 hydroxyl group of M3 and the side chain carboxyl group of Glu257 and between the C4 hydroxyl group of M3 and the terminal guanidinium group of Arg229. Equivalent hydrogen bonds are found in binding site 4 (Fig. 5E), such as hydrogen bonds between the backbone amide of Gly212 and the C5 hydroxyl group of M5′, the backbone amide of Gly213 and the C6 hydroxyl group of M5′, and the backbone amide of Gly191 and the C5 hydroxyl group of M4′, with side chain hydrogen bonding between the C4 hydroxyl group of M3 and the side chain carboxyl group of Glu190 and between the C4 hydroxyl group of M3 and the terminal guanidinium group of Arg162. Given the high sequence conservation in the carbohydrate binding regions between MBHA and OAA (Fig. 1A), it is not surprising that all specific contacts that are observed in the MBHA-α3,α6-mannopentaose complex are identical to those observed previously in the OAA-α3,α6-mannopentaose complex (24).

Unlike OAA and MBHA, we were not successful in obtaining crystals of the PFA-α3,α6-mannopentaose complex. Nevertheless, given the high amino acid conservation in the carbohydrate binding loops among PFA, OAA, and MBHA (Fig. 1A), the chemical shift perturbation profile of PFA upon α3,α6-mannopentaose titration (Figs. 1B and 3B), and the identical interactions observed in the complexes of MBHA-α3,α6-mannopentaose and OAA-α3,α6-mannopentaose (Fig. 5, D and E), we are confident that a reliable model for PFA-α3,α6-mannopentaose complex can be derived. This is provided in Fig. 6 and was obtained by exchanging OAA residues in the structure of the OAA-α3,α6-mannopentaose complex to the corresponding PFA amino acids. The residue variability in the hydrophobic core of both proteins is very minor, and only six residues are different, namely I25L, V38L, L47F, L92I, I103L, and M118N (Fig. 6A). The remaining nonidentical amino acids are located on the surface of the proteins, as illustrated in Fig. 6B. Interestingly, all residues that play major roles in contacting the carbohydrate in OAA and MBHA are completely conserved in PFA. These include residues Trp10–Gly12, Arg95, and Glu123–Gly124 in binding site 1 (Fig. 6C) and Trp77–Gly79, Arg28, and Glu56–Gly57 in binding site 2 (Fig. 6D). Between OAA and PFA, almost all residues in the carbohydrate binding sites 1 and 2, encompassing loop regions between strands β1-β2, β7-β8, and β9-β10 (site 1) and between strands β6-β7, β2-β3, and β4-β5 (site 2), are also conserved. Although the interaction model between PFA and α3,α6-mannopentaose could potentially be validated using a docking program, our manual model provides compelling evidence that the interaction between PFA and α3,α6-mannopentaose in all likelihood is the same as in the OAA-α3,α6-mannopentaose or the MBHA-α3,α6-mannopentaose complexes.

FIGURE 6.

Structural model of α3,α6-mannopentaose-bound PFA based on the OAA-α3,α6-mannopentaose complex. A and B, stereo views of the PFA carbohydrate binding sites 1 and 2, highlighting amino acid differences between OAA and PFA in the hydrophobic (A) and solvent-exposed regions (B). C and D, predicted intermolecular hydrogen bonds between PFA and α3,α6-mannopentaose (black dashed lines) in binding sites 1 (C) and 2 (D). Residues that are in direct contact with the carbohydrate are identical in PFA and OAA: Trp10, Gly11, Gly12, Arg95, Glu123, and Gly124 in binding site 1 (C) and Trp77, Gly78, Gly79, Arg28, Glu56, and Gly57 in binding site 2 (D). The protein is depicted in both ribbon and stick representation, with bound α3,α6-mannopentaose in stick representation only. All carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen atoms of the conserved residues in PFA and OAA and in the carbohydrates are shown in white, red, and blue, respectively. The carbon atoms of differing residues in PFA and OAA are colored in cyan. Amino acids are labeled by single-letter code, and the sugar rings of the carbohydrate are labeled according to standard nomenclature.

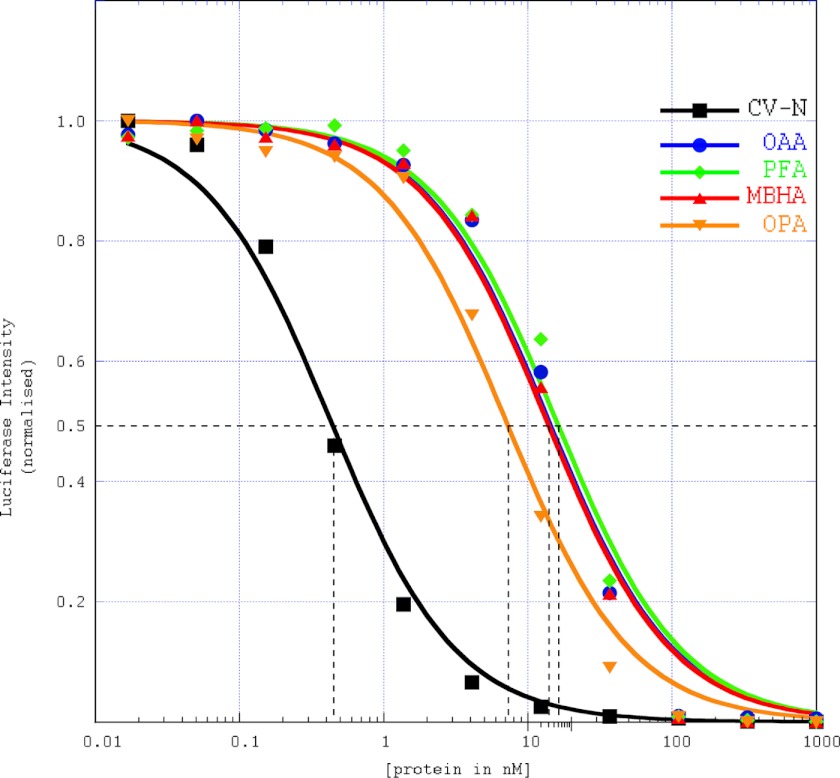

Anti-HIV Activities of PFA and MBHA

The OAA anti-HIV activity is mediated by the specific recognition of α3,α6-mannopentaose, the branched core unit of Man-8 and Man-9 (23, 38), major high mannose sugars on the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp120 (39). Here, we show that both PFA and MBHA also interact with this glycan structure, suggesting possible similar activities for these lectins. We therefore tested these molecules in HIV assays, using monomeric P51G CV-N and OAA as controls.

The HIV assay data (Fig. 7) clearly shows that PFA and MBHA possess anti-HIV activity. All three OAAHs display very similar IC50 values between 12 ± 1.0 nm (OAA and MBHA) and 15 ± 1.0 nm (PFA), values ∼30-fold higher than that obtained for CV-N at the same time (0.4 ± 0.1 nm).

FIGURE 7.

Anti-HIV activity assays for OAAHs. Single-cycle HIV-1 infectivity assays were performed using a luciferase reporter cell line to quantify the antiviral activity of the lectins. Experimental data points and the lines for CV-N (square), OAA (circle), PFA (diamond), MBHA (triangle), and OPA (inverted triangle) are colored in black, blue, green, red, and orange, respectively. Each data point was obtained from six duplicate measurements. The dashed black lines were used for extracting the IC50 concentration.

If solely avidity considerations were significant, one would expect MBHA to exhibit higher anti-HIV activity than OAA and PFA given that it possesses four sugar binding sites when compared with only two sites in the latter lectins. We interpret the comparable activity for all OAAH family members such that only one or two binding sites can engage the sugars on gp120 and that potentially a single interaction is important for anti-HIV activity.

Importantly, CV-N is more active (∼30-fold improved IC50 value) than any of the three OAAHs. Considering that CV-N, OAA, and PFA share the same number of binding sites for carbohydrate and the dissociation constants of these lectins for the individual sugar ligands are relatively similar (in the low micromolar range) (23, 40), one would expect comparable inhibition with similar IC50 values. This clearly is not the case. We therefore propose the following explanation. OAA, PFA, and MBHA recognize only a single epitope of Man-8/9, namely the branched core unit (24), whereas CV-N binds to Manα(1–2)Man units on the D1 or D3 arms (11, 12), i.e. interacts with two alternative epitopes on the glycan. Therefore, multisite and multiepitope recognition seems essential for the most potent HIV inactivation (a schematic model for HIV inactivation is provided (see Fig. 9)).

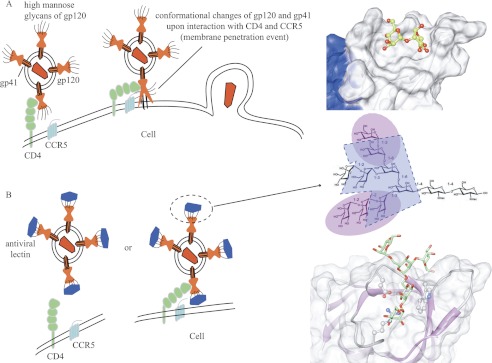

FIGURE 9.

Schematic depiction of HIV inactivation by Cyanovirin-N homolog (CVNH) and OAAH lectins. A, in the absence of antiviral lectins, the interaction between gp120 and CD4 introduces a conformational change that allows the fusion peptide of gp41 to penetrate the cell membrane, leading to viral-cell membrane fusion and HIV capsid deposition into the cell. B, in the presence of antiviral lectins, they bind to the high mannose glycans on gp120/41, preventing the required conformational change, thereby blocking infection. The glycan epitopes of Man-9 that are recognized by CV-N (highlighted in magenta) and OAA (highlighted in blue) as well as their detailed interactions at the atomic level are provided at the right-hand side.

In addition to the native three OAAH family members, we also created a hybrid protein from OAA and PFA (named OPA), in which the two parental proteins are connected by a two-residue N-G linker between the C terminus of OAA and the N terminus of PFA. As shown in Fig. 8, A and B, the two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of OPA exhibits all the characteristics of a well folded structure and is essentially identical to the sum of the 1H-15N HSQC spectra of OAA (Fig. 8A, green) and PFA (Fig. 8B, magenta) with only minor perturbations involving the last C-terminal residues of OAA and first N-terminal residues of PFA (Fig. 8C). Therefore, the overall structure of OPA is essentially a tandem, double barrel protein in which OAA and PFA are linked.

FIGURE 8.

Comparison of the structures and NMR titrations of OPA with α3,α6-mannopentaose by 1H-15N HSQC spectroscopy. A and B, superposition of the two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra of OPA (black) and OAA (green) (A) and of OPA (black) and PFA (magenta) (B). Residues of OAA and PFA that exhibit small chemical shift changes are labeled by amino acid type and number. The four amide resonances of the OPA glycines that correspond to Gly26 and Gly93 in OAA or PFA are shown in the bottom inset. C, structural mapping of OAA and PFA residues that exhibit chemical shift differences between the two proteins. The C-terminal residue of OAA and the N-terminal residue of PFA are colored in red and blue, respectively. The short two-residue linker connecting OAA and PFA is depicted by a dashed orange line. D, superposition of the two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra of free (black) and α3,α6-mannopentaose bound (blue) OPA at molar ratio of OPA to α3,α6-mannopentaose of 1:4. E and F, superposition of selected regions of the two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra of free (black) and α3,α6-mannopentaose bound OPA at 1:1 (red), 1:2 (green), and 1:4 (blue) molar ratios of OPA to sugar for residues Ala15/Ala82 (E; cyan) and residues Gly60/Gly127 (F; magenta). G and H, superposition of selected regions of the two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra of OAA (cyan), PFA (magenta) and OPA (blue) at the final titration point. All spectra are plotted at the same contour level, and all titrations were carried out using 0.100 mm OPA in 20 mm sodium acetate, 20 mm NaCl, 3 mm NaN3, 90/10% H2O/D2O (pH 5.0), 25 °C.

Interestingly, in the HIV assays, OPA inhibited HIV replication slightly better than OAA or PFA, displaying an IC50 of 7.5 ± 0.5 nm (Fig. 7). Although this difference is small, it was nevertheless surprising because only very minor conformational changes from the original OAA and PFA structures were expected in the hybrid OPA. We therefore tested whether, fortuitously, the apparent glycan affinity was altered.

The data in Fig. 8D show that OPA specifically interacts with α3,α6-mannopentaose and that binding is in slow exchange on the NMR chemical shift scale. The resonances of OPA were completely saturated at a protein:sugar molar ratio of 1:4 (Fig. 8D, colored in blue), indicating that the four binding sites in OPA are competent for sugar binding. For OAA, PFA, and MBHA, saturation was reached at a protein:sugar molar ratio of 1:3 (24), 1:3 (Fig. 3, C–E), and 1:6 (Fig. 4, B–E), respectively, suggesting that each binding site in OPA exhibits a slightly higher affinity for the sugar than observed in the parental OAA and PFA lectins or the double domain MBHA protein.

In addition to the delineation of the four binding sites in OPA (see the affected resonances of Ala15 and Ala82, Fig. 8E, and Gly60 and Gly127, Fig. 8F) derived from OAA and PFA, respectively (colored in cyan and magenta), each binding site in OPA exhibits essentially identical affinity toward α3,α6-mannopentaose, with resonances of all interacting residues equally perturbed at the 1:2 molar ratio, where each binding site should be half-saturated for identical sugar affinities (Fig. 8, E and F, green). This is different from PFA where slightly different affinities are observed for the two binding sites (Fig. 3, C–E). The equal affinity for each binding site in the hybrid protein may be the result of a minor structural change caused by the linker or a small positive avidity effect. This slightly tighter glycan binding may contribute to the somewhat higher apparent anti-HIV potency noted in the HIV assays. It is also worth pointing out that the α3,α6-mannopentaose-bound resonances for equivalent residues in OPA, OAA, and PFA exhibit identical frequencies (Fig. 8, G and H; OPA, OAA, and PFA are colored blue, cyan, and magenta, respectively), suggesting very similar conformations of OPA and its parental proteins in the bound state.

Conclusion

Crystal structures for two members of the OAAH lectin family, PFA and MBHA, were determined at resolutions of 1.70 and 1.60 Å, respectively, as well as for the α3,α6-mannopentaose-bound MBHA at 1.76 Å. Structural comparison between these two new members and OAA, the founding member of the OAAH lectin family, revealed a very similar overall fold, with only minor conformational differences in the loop regions, connecting strands β1-β2, β2-β3, β4-β5, β5-β6, β6-β7, and β7-β8, that are caused by different crystal packing in these proteins. These new members bind tightly and specifically to α3,α6-mannopentaose, exhibiting identical intermolecular interactions to those previously observed in the OAA-α3,α6-mannopentaose complex structure. HIV assays revealed that all OAAH proteins and the designer hybrid OAAH (OPA) display anti-HIV activity and all are slightly less potent than CV-N. Our results provide further details toward a structural understanding of the protein-carbohydrate interaction in this novel lectin family, as well as insights into the molecular basis of its HIV inactivation properties (Fig. 9). Such data can potentially be used in the development of lectins as antiviral reagents that target the gp120 glycans in the quest to combat HIV transmission.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. William Furey for helpful discussion and Mike Delk for NMR technical support. The following reagent was obtained through the National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, National Institutes of Health: TZM-bl from Dr. John C. Kappes, Dr. Xiaoyun Wu, and Tranzyme Inc.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM080642 (to A. M. G.).

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 4FBO, 4FBR, and 4FBV) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

- CV-N

- cyanovirin-N

- OAA

- O. agardhii agglutinin

- OAAH

- OAA homolog

- PFA

- P. fluorescens agglutinin

- MBHA

- myxobacterium hemagglutinin

- OPA

- OAAH protein

- TROSY

- transverse relaxation optimized spectroscopy

- r.m.s.d.

- root mean square deviation

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single quantum correlation.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ziól̸kowska N. E., Wlodawer A. (2006) Structural studies of algal lectins with anti-HIV activity. Acta Biochim. Pol. 53, 617–626 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Botos I., Wlodawer A. (2005) Proteins that bind high mannose sugars of the HIV envelope. Prog. Biophys. Mol Biol. 88, 233–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Balzarini J. (2006) Inhibition of HIV entry by carbohydrate-binding proteins. Antiviral Res. 71, 237–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. O'Keefe B. R., Shenoy S. R., Xie D., Zhang W., Muschik J. M., Currens M. J., Chaiken I., Boyd M. R. (2000) Analysis of the interaction between the HIV-inactivating protein cyanovirin-N and soluble forms of the envelope glycoproteins gp120 and gp41. Mol. Pharmacol. 58, 982–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boyd M. R., Gustafson K. R., McMahon J. B., Shoemaker R. H., O'Keefe B. R., Mori T., Gulakowski R. J., Wu L., Rivera M. I., Laurencot C. M., Currens M. J., Cardellina J. H., 2nd, Buckheit R. W., Jr., Nara P. L., Pannell L. K., Sowder R. C., 2nd, Henderson L. E. (1997) Discovery of cyanovirin-N, a novel human immunodeficiency virus-inactivating protein that binds viral surface envelope glycoprotein gp120: potential applications to microbicide development. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 41, 1521–1530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barrientos L. G., Gronenborn A. M. (2005) The highly specific carbohydrate-binding protein cyanovirin-N: structure, anti-HIV/Ebola activity and possibilities for therapy. Mini. Rev. Med. Chem. 5, 21–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Botos I., O'Keefe B. R., Shenoy S. R., Cartner L. K., Ratner D. M., Seeberger P. H., Boyd M. R., Wlodawer A. (2002) Structures of the complexes of a potent anti-HIV protein cyanovirin-N and high mannose oligosaccharides. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 34336–34342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barrientos L. G., Gronenborn A. M. (2002) The domain-swapped dimer of cyanovirin-N contains two sets of oligosaccharide binding sites in solution. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 298, 598–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Barrientos L. G., Matei E., Lasala F., Delgado R., Gronenborn A. M. (2006) Dissecting carbohydrate-cyanovirin-N binding by structure-guided mutagenesis: functional implications for viral entry inhibition. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 19, 525–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bewley C. A. (2001) Solution structure of a cyanovirin-N:Manα1–2Manα complex: structural basis for high affinity carbohydrate-mediated binding to gp120. Structure 9, 931–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bewley C. A., Otero-Quintero S. (2001) The potent anti-HIV protein cyanovirin-N contains two novel carbohydrate binding sites that selectively bind to Man8 D1D3 and Man9 with nanomolar affinity: implications for binding to the HIV envelope protein gp120. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 3892–3902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shenoy S. R., Barrientos L. G., Ratner D. M., O'Keefe B. R., Seeberger P. H., Gronenborn A. M., Boyd M. R. (2002) Multisite and multivalent binding between cyanovirin-N and branched oligomannosides: calorimetric and NMR characterization. Chem. Biol. 9, 1109–1118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Geijtenbeek T. B., Kwon D. S., Torensma R., van Vliet S. J., van Duijnhoven G. C., Middel J., Cornelissen I. L., Nottet H. S., KewalRamani V. N., Littman D. R., Figdor C. G., van Kooyk Y. (2000) DC-SIGN, a dendritic cell-specific HIV-1-binding protein that enhances trans-infection of T cells. Cell 100, 587–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pöhlmann S., Baribaud F., Lee B., Leslie G. J., Sanchez M. D., Hiebenthal-Millow K., Münch J., Kirchhoff F., Doms R. W. (2001) DC-SIGN interactions with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and 2 and simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 75, 4664–4672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bokesch H. R., O'Keefe B. R., McKee T. C., Pannell L. K., Patterson G. M., Gardella R. S., Sowder R. C., 2nd, Turpin J., Watson K., Buckheit R. W., Jr., Boyd M. R. (2003) A potent novel anti-HIV protein from the cultured cyanobacterium Scytonema varium. Biochemistry 42, 2578–2584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mori T., O'Keefe B. R., Sowder R. C., 2nd, Bringans S., Gardella R., Berg S., Cochran P., Turpin J. A., Buckheit R. W., Jr., McMahon J. B., Boyd M. R. (2005) Isolation and characterization of griffithsin, a novel HIV-inactivating protein, from the red alga Griffithsia sp. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 9345–9353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yamaguchi M., Ogawa T., Muramoto K., Kamio Y., Jimbo M., Kamiya H. (1999) Isolation and characterization of a mannan-binding lectin from the freshwater cyanobacterium (blue-green algae) Microcystis viridis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 265, 703–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chiba H., Inokoshi J., Okamoto M., Asanuma S., Matsuzaki K. i., Iwama M., Mizumoto K., Tanaka H., Oheda M., Fujita K., Nakashima H., Shinose M., Takahashi Y., Omura S. (2001) Actinohivin, a novel anti-HIV protein from an actinomycete that inhibits syncytium formation: isolation, characterization, and biological activities. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 282, 595–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Feinberg H., Mitchell D. A., Drickamer K., Weis W. I. (2001) Structural basis for selective recognition of oligosaccharides by DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR. Science 294, 2163–2166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ziól̸kowska N. E., O'Keefe B. R., Mori T., Zhu C., Giomarelli B., Vojdani F., Palmer K. E., McMahon J. B., Wlodawer A. (2006) Domain-swapped structure of the potent antiviral protein Griffithsin and its mode of carbohydrate binding. Structure 14, 1127–1135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Williams D. C., Jr., Lee J. Y., Cai M., Bewley C. A., Clore G. M. (2005) Crystal structures of the HIV-1 inhibitory cyanobacterial protein MVL free and bound to Man3GlcNAc2: structural basis for specificity and high affinity binding to the core pentasaccharide from N-linked oligomannoside. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 29269–29276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tanaka H., Chiba H., Inokoshi J., Kuno A., Sugai T., Takahashi A., Ito Y., Tsunoda M., Suzuki K., Takénaka A., Sekiguchi T., Umeyama H., Hirabayashi J., Omura S. (2009) Mechanism by which the lectin Actinohivin blocks HIV infection of target cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 15633–15638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Koharudin L. M., Furey W., Gronenborn A. M. (2011) Novel fold and carbohydrate specificity of the potent anti-HIV cyanobacterial lectin from Oscillatoria agardhii. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 1588–1597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Koharudin L. M., Gronenborn A. M. (2011) Structural basis of the anti-HIV activity of the cyanobacterial Oscillatoria agardhii agglutinin. Structure 19, 1170–1181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sato T., Hori K. (2009) Cloning, expression, and characterization of a novel anti-HIV lectin from the cultured cyanobacterium, Oscillatoria agardhii. Fish Sci. 75, 743–753 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pflugrath J. W. (1999) The finer things in X-ray diffraction data collection. Acta Crystallogr D Biol. Crystallogr 55, 1718–1725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 (1994) The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol. Crystallogr 50, 760–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McCoy A. J. (2007) Solving structures of protein complexes by molecular replacement with Phaser. Acta Crystallogr D Biol. Crystallogr 63, 32–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol. Crystallogr 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol. Crystallogr 53, 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Davis I. W., Leaver-Fay A., Chen V. B., Block J. N., Kapral G. J., Wang X., Murray L. W., Arendall W. B., 3rd, Snoeyink J., Richardson J. S., Richardson D. C. (2007) MolProbity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W375–W383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pettersen E. F., Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Couch G. S., Greenblatt D. M., Meng E. C., Ferrin T. E. (2004) UCSF Chimera–a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. DeLano W. L. (2010) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.3r1, Schrödinger, LLC, New York [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bax A., Grzesiek S. (1993) Methodological advances in protein NMR. Acc. Chem. Res. 26, 131–138 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G. W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A. (1995) NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. Journal of Biomolecular NMR 6, 277–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Johnson B. A., Blevins R. A. (1994) NMRView: A computer program for the visualization and analysis of NMR data. J. Biomol. NMR 4, 603–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Derdeyn C. A., Decker J. M., Sfakianos J. N., Wu X., O'Brien W. A., Ratner L., Kappes J. C., Shaw G. M., Hunter E. (2000) Sensitivity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to the fusion inhibitor T-20 is modulated by coreceptor specificity defined by the V3 loop of gp120. J. Virol. 74, 8358–8367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sato Y., Okuyama S., Hori K. (2007) Primary structure and carbohydrate binding specificity of a potent anti-HIV lectin isolated from the filamentous cyanobacterium Oscillatoria agardhii. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 11021–11029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Doores K. J., Bonomelli C., Harvey D. J., Vasiljevic S., Dwek R. A., Burton D. R., Crispin M., Scanlan C. N. (2010) Envelope glycans of immunodeficiency virions are almost entirely oligomannose antigens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 13800–13805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Matei E., Furey W., Gronenborn A. M. (2008) Solution and crystal structures of a sugar binding site mutant of cyanovirin-N: no evidence of domain swapping. Structure 16, 1183–1194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]