Summary

Tetrodotoxin (TTX)-sensitive sodium channels carry large transient currents during action potentials and also “persistent” sodium current, a non-inactivating TTX-sensitive current present at subthreshold voltages. We examined gating of subthreshold sodium current in dissociated cerebellar Purkinje neurons and hippocampal CA1 neurons, studied at 37 °C with near-physiological ionic conditions. Unexpectedly, in both cell types small voltage steps at subthreshold voltages activated a substantial component of transient sodium current as well as persistent current. Subthreshold EPSP-like waveforms also activated a large component of transient sodium current, but IPSP-like waveforms engaged primarily persistent sodium current with only a small additional transient component. Activation of transient as well as persistent sodium current at subthreshold voltages produces amplification of EPSPs that is sensitive to the rate of depolarization and can help account for the dependence of spike threshold on depolarization rate, as previously observed in vivo.

Keywords: CA1 pyramidal neuron, Purkinje neuron, persistent sodium current, IPSP, sodium channel

Introduction

Most neurons express a high density of tetrodotoxin (TTX)-sensitive voltage-gated sodium channels, whose main function is to generate action potentials by carrying a large rapidly-activating and rapidly-inactivating “transient” sodium current, activated when membrane voltage is depolarized above threshold (typically near −55 to −50 mV). In addition, however, many neurons also express a much smaller TTX-sensitive sodium current that flows at subthreshold voltages. This has generally been characterized as a current that is activated by depolarization but shows little or no inactivation, thus constituting a steady-state or “persistent” sodium current at subthreshold voltages. When recorded in cells in brain slice (reviewed by Crill, 1996), the persistent sodium current is typically first evident at voltages depolarized to about −70 mV and is steeply voltage-dependent.

Although subthreshold sodium current is very small compared to the transient sodium current during an action potential, it greatly influences the frequency and pattern of firing of many neurons by producing a regenerative depolarizing current in the voltage range between the resting potential and spike threshold, where other ionic currents are small. Subthreshold sodium current can drive pacemaking (e.g. Bevan and Wilson, 1999; Del Negro et al., 2002), promote bursting (Azouz et al., 1996; Williams and Stuart, 1999), generate and amplify subthreshold electrical resonance (Gutfreund et al., 1995; D’Angelo et al., 1998) and promote theta-frequency oscillations (White et al., 1998; Hu et al., 2002). In addition, subthreshold sodium current amplifies excitatory post-synaptic potentials (EPSPs) by activating in response to the depolarization of the EPSP (Deisz et al., 1991; Stuart and Sakmann, 1995; Schwindt and Crill, 1995) and can also amplify inhibitory post-synaptic potentials (IPSPs) (Stuart, 1999; Hardie and Pearce, 2006).

Subthreshold sodium current has generally been assumed to correspond exclusively to non-inactivating persistent sodium current. However, voltage-clamp characterization has typically been done using slow voltage ramp commands, which define the voltage-dependence of steady-state persistent current but do not give information about kinetics of activation and would not detect the presence of an inactivating transient component if one existed. Also, characterization of persistent sodium current has typically been done using altered ionic conditions to inhibit potassium and calcium currents. We set out to explore the kinetics and voltage-dependence of subthreshold sodium current with physiological ionic conditions and temperature using acutely dissociated central neurons, in which subthreshold persistent sodium current is present (e.g. French et al., 1990; Raman and Bean, 1997; Kay et al., 1998) and in which rapid, high-resolution voltage clamp is possible. We find that under physiological conditions subthreshold sodium current activates at surprisingly negative voltages, that activation and deactivation kinetics are rapid, and that small voltage steps or EPSP-like voltage changes can activate transient as well as steady-state sodium current. The properties of subthreshold sodium current suggest that it can influence the kinetics and amplitude of small EPSPs near typical resting potentials, a prediction that is confirmed using 2-photon glutamate uncaging to probe the contribution of sodium currents to single synapse responses.

Results

Steady-state and transient subthreshold sodium current

To examine the voltage dependence and gating kinetics of subthreshold sodium current with good voltage control and high time resolution, we used acutely dissociated neurons. To approximate physiological conditions as nearly as possible, we made recordings at 37 °C and used the same potassium methanesulfonate-based internal solution as in previous current clamp recordings from the neurons (Carter and Bean, 2009, 2011). Using these conditions to record from mouse cerebellar Purkinje neurons, depolarization by a slow (10 mV/s) ramp evoked TTX-sensitive current that was first evident near −80 mV and increased steeply with voltage to reach a maximum near −50 mV (black trace, Fig. 1A). The TTX-sensitive current evoked by this slow ramp was similar to steady-state “persistent” sodium current previously recorded in Purkinje neurons but activated at considerably more negative voltages than in recordings with less physiological conditions (Raman and Bean, 1997; Kay et al., 1998). In recordings from 26 cells, the TTX-sensitive steady-state current was −16 ± 2 pA at −80 mV, −81 ± 16 pA at −70 mV, −254 ± 23 pA at −60 mV, and reached a maximum of −393 ± 31 pA at −48 ± 1 mV. When converted to a conductance, the voltage-dependence of steady-state current could be fit well by a Boltzmann function (Figure 1C) with average midpoint of −62 ± 1 mV and an average slope factor of 4.9 ± 0.1 mV (n=26).

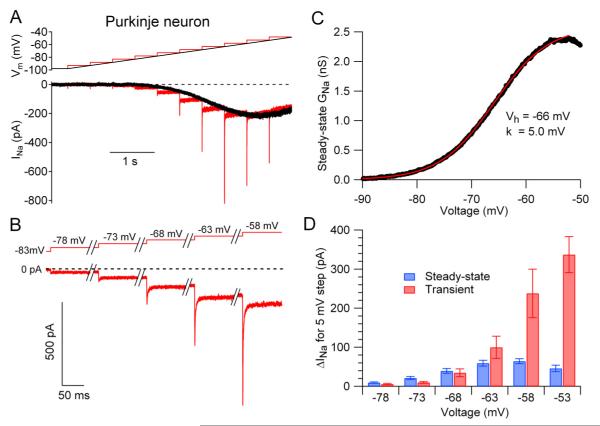

Figure 1. Transient and steady-state sodium current at subthreshold voltages in a Purkinje neuron.

(A) TTX-sensitive sodium current in a cerebellar Purkinje neuron evoked by a slow (10 mV/s) ramp from −98 to −48 mV (black trace) and by a staircase series of 500-msec 5-mV steps at the same overall rate of depolarization (red traces).

(B) Initial segments of staircase-evoked sodium currents shown on a faster time base, illustrating component of transient current.

(C) Voltage-dependence of steady-state sodium conductance calculated from the ramp current in A (black), fit with a Boltzmann function (red).

(D) Collected results, comparing the change in steady-state sodium current (blue) with the transient component of current (red) for 5-mV depolarizing steps to various voltages in the subthreshold range. Bars indicate mean ± SEM for measurements in 10 Purkinje neurons.

Slow ramps define the voltage dependence of the steady-state sodium current, but do not provide kinetic information about channel activation. Because activation kinetics are important for determining the timing with which sodium current can be engaged by transient synaptic potentials, we assayed kinetics by applying successive 5-mV step depolarizations at the same overall rate as the ramp depolarization (10 mV/s, Figure 1A, red traces). As expected, the current at the end of each voltage step reached steady-state and closely matched the ramp-evoked current at that voltage. Unexpectedly, however, there was also a prominent transient phase of sodium current for depolarizations positive to about −70 mV. For example, a step from −73 to −68 mV activated a component of transient current nearly as large as the change in steady-state current (Figure 1B). The relative magnitude of the transient current evoked by 5-mV steps increased at more depolarized voltages. For a step from −63 to −58 mV, transient current was on average more than three times the size of the change in steady current (−238 ± 62 pA versus −64 ± 6 pA, n=10).

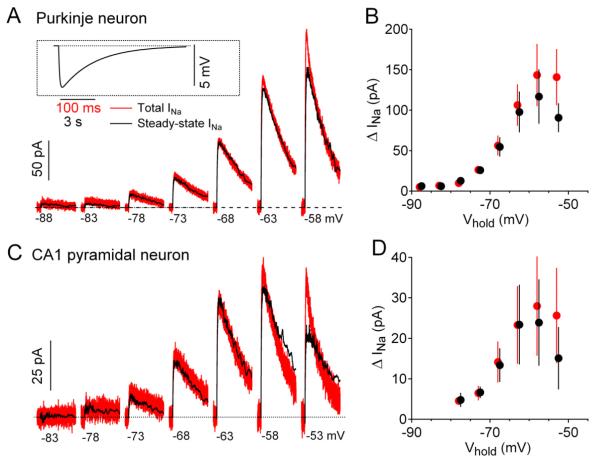

To test whether subthreshold transient sodium current is a unique property of Purkinje neurons, we performed similar experiments in acutely dissociated pyramidal neurons isolated from the hippocampal CA1 region. These experiments showed very similar subthreshold currents as in Purkinje neurons (Figure 2A,B). Both the steady-state sodium current and the transient component of subthreshold current had almost identical voltage-dependence and kinetics in CA1 neurons and in Purkinje neurons, differing mainly in being on average somewhat smaller in CA1 pyramidal neurons. The voltage-dependence of steady-state sodium conductance in CA1 neurons (e.g. Figure 2C) had a midpoint of activation of −62 ± 1 mV, and a slope factor of 4.4 ± 0.2 mV (n=15), almost the same as in Purkinje neurons. The average maximal steady-state sodium conductance in CA1 was 2.0 ± 0.5 nS (n=15) compared to 3.7 ± 0.3 nS (n=26) in isolated Purkinje neurons.

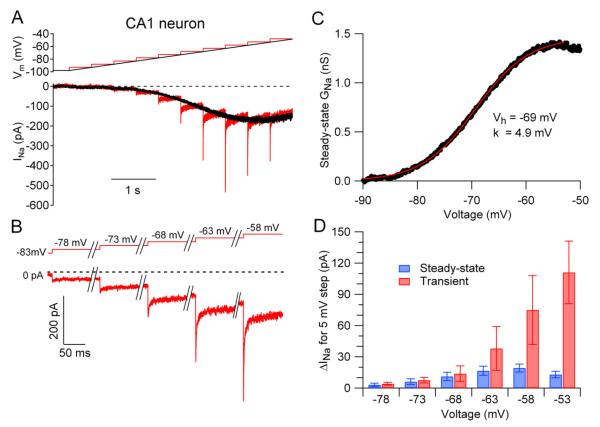

Figure 2. Transient and steady-state sodium current at subthreshold voltages in CA1 pyramidal neurons.

(A) TTX-sensitive sodium current in a CA1 pyramidal neuron evoked by a slow (10 mV/s) ramp from −98 to −48 mV (black trace) and by a staircase series of 500-msec 5-mV steps (red traces).

(B) Initial segments of staircase-evoked sodium currents showing transient current.

(C) Voltage-dependence of steady-state sodium conductance calculated from the ramp current in A (black), fit with a Boltzmann function (red).

(D) Collected results for CA1 pyramidal neurons, comparing the change in steady-state sodium current (blue) with the transient component of current (red) for 5-mV depolarizing steps to various voltages. Bars indicate mean ± SEM for measurements in 11 neurons.

CA1 neurons responded to subthreshold steps with transient activation of sodium current (Figure 2A,B; red traces) in a manner very similar to Purkinje neurons. For a step from −63 to −58 mV, transient current was on average more than three times the size of the change in steady-state current (−75 ± 33 pA versus −19 ± 4 pA, n=11).

Sodium channel activation during EPSP-like voltage changes

Voltage does not change instantaneously during the physiological behavior of a neuron. The degree of activation of transient sodium current during a subthreshold synaptic potential will depend on both voltage and its rate of change. To test whether EPSP-like voltage changes activate a component of transient current, we used EPSP-like waveforms as voltage commands. The EPSP-like waveform was constructed to match kinetics of experimentally recorded EPSP waveforms from Purkinje neurons, with a rising phase with a time constant of 2 msec followed by a falling phase with a time constant of 65 msec (Isope and Barbour, 2002; Mittmann and Hausser, 2007). When the EPSP waveform was applied to a Purkinje neuron from a holding voltage of −63 mV (where there was a steady TTX-sensitive current of about −160 pA), it activated additional TTX-sensitive sodium current, reaching a peak of about −368 pA (red trace). To test whether the current evoked by the waveform includes a transient component, we compared it to the current evoked by the same waveform but slowed by a factor of 50 (black trace), which, by changing voltage so slowly, should elicit only steady-state current without a transient component. This slow waveform evoked much less sodium current (increment of −128 pA) than the current evoked by the real-time EPSP (increment of −208 pA), showing that the real-time EPSP evokes transient as well as steady-state current. The component of transient sodium current was even more pronounced when the EPSP waveform was applied from a holding potential of −58 mV (Fig. 3A, right). Figure 3B shows the currents elicited by the real-time and slowed versions of the EPSP from a range of holding potentials. Substantial sodium current was activated by the 5-mV EPSP waveforms from holding potentials positive to −78 mV. At holding potentials negative to −68 mV, the current engaged by EPSP waveforms was primarily steady-state current, but at voltages positive to −68 mV, there was an additional component of transient sodium current. The behavior in this cell was typical of that in collected results from 8 Purkinje neurons (Figure 3C), with an increasingly prominent transient component evoked by the EPSP waveform as holding voltage became more depolarized. In collected results, real-time EPSP waveforms delivered from −58 mV evoked a peak change in sodium current of −202 ± 18 pA, substantially larger than the peak change in current of −81 ± 10 pA evoked by the slowed EPSP waveform (n=8).

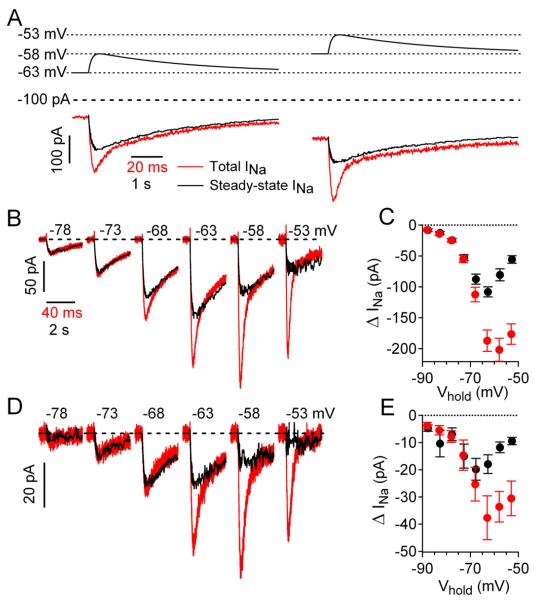

Figure 3. TTX-sensitive sodium current evoked by EPSP-like waveforms in Purkinje neurons and CA1 pyramidal neurons.

(A) TTX-sensitive sodium current in a Purkinje neuron elicited by a 5-mV EPSP-like voltage command (red traces) or by the same command slowed by a factor of 50 to evoke only steady-state current (black traces). EPSP waveforms were delivered from holding potentials of either −63 mV (left) or −58 mV (right).

(B) TTX-sensitive current in a Purkinje neuron evoked from various holding potentials by the real-time EPSP waveform (red traces) compared with steady-state sodium current (black traces). Each trace is plotted with an offset corresponding to the steady sodium current at the holding potential (before the EPSP waveform), so that steady sodium current at each holding potential is on the same horizontal line; steady sodium currents were −17 pA at −78 mV, −42 pA at −73 mV, −84 pA at −68 mV,-161 pA at −63 mV, −239 pA at −58 mV, and −280 pA at −53 mV.

(C) Summary of Purkinje neuron data for peak change in sodium current during EPSP-like waveforms evoked from different holding potentials. Red symbols are the mean ± SEM peak total evoked sodium current, black symbols are mean ± SEM steady-state sodium current (n=6-8).

(D) EPSP-like voltage changes elicit transient and steady-state components of sodium current in CA1 neurons. Steady sodium currents (offsets) were −1 pA at −78 mV, −3 pA at −73 mV, −10 pA at −68 mV,-23 pA at −63 mV, −29 pA at −58 mV, and −30 pA at −53 mV. (E) Summary of CA1 neuron data for peak change in sodium current during EPSP-like waveforms evoked from different holding potentials. Red symbols are the mean ± SEM peak total evoked sodium current, black symbols are mean ± SEM steady-state sodium current (n=8-14).

Recordings from CA1 pyramidal neurons using the same real-time and slowed EPSP-like voltage commands gave very similar results (Fig. 3D and 3E). Real-time EPSP waveforms delivered from −58 mV evoked a peak change in sodium current of −34 ± 6 pA compared to a peak change in current of −12 ± 2 pA evoked by the slowed EPSP waveform (n=13).

These results show that in both Purkinje neurons and CA1 pyramidal neurons, a transient component of subthreshold sodium current can be engaged by EPSP waveforms. At voltages negative to about −65 mV, the sodium current engaged by the EPSP is accounted for almost entirely by steady-state or persistent sodium current, while at voltages positive to −65 mV, there is an additional component corresponding to transient sodium current.

Kinetics of sodium channel gating at subthreshold voltages

We characterized the activation and deactivation kinetics of sodium current using 5-mV depolarizing and hyperpolarizing steps. Figure 4A shows an example of stairstep-evoked currents compared with ramp-evoked currents in a Purkinje neuron. The ramp-evoked current was nearly symmetric when a depolarizing ramp was followed by a hyperpolarizing ramp over the same voltage range. In contrast, the stairstep-evoked current was asymmetric. The depolarizing steps evoked large transient currents, while the hyperpolarizing steps evoked much smaller transient currents. Figure 4B shows this asymmetry more clearly. Holding at −63 mV, there was steady-state sodium current of −116 pA. Upon depolarization to −58 mV, there was rapid activation of sodium current that reached −362 pA, followed by inactivation to a new steady-state level of −147 pA. Hyperpolarization to −63 mV deactivated sodium channels rapidly and transiently to −55 pA, followed by recovery back to the steady-state level of −116 pA at −63 mV.

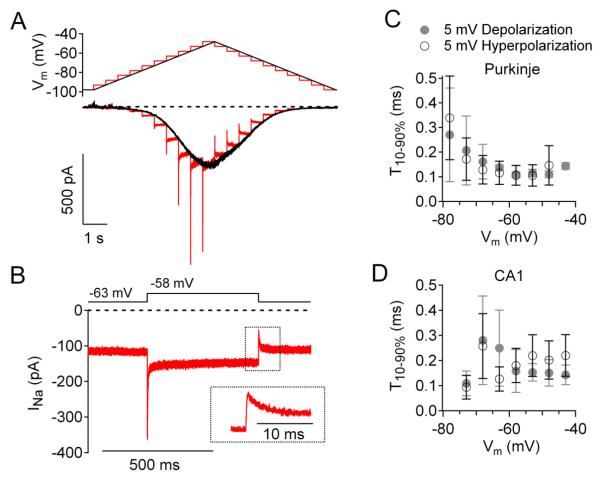

Figure 4. Kinetics of activation and deactivation of subthreshold sodium current.

(A) Currents evoked in a Purkinje neuron by upward followed by downward staircase protocols (red) and steady-state current evoked by a slow ramp (10 mV/s) in both directions.

(B) Sodium current evoked by a 500-ms step from −63 to −58 mV and back (same neuron as A). Inset: Current during step from −58 to −63 mV shown at faster time base, showing rapid deactivation followed by partial recovery from inactivation.

(C) Time required for 10-90% change in sodium current in response to 5-mV depolarizations (filled symbols) and hyperpolarizations (open symbols) in Purkinje neurons (mean ± SEM, n=3-6) for steps to the indicated voltage.

(D) Time required for 10-90% change in sodium current in response to 5-mV depolarizations (filled symbols) and hyperpolarizations (open symbols) in CA1 pyramidal neurons (mean ± SEM, n=3-7).

The transient component of sodium current during hyperpolarizing steps can most readily be interpreted as reflecting rapid deactivation of channels, producing an almost instantaneous decline in inward current, followed by slower (partial) recovery from inactivation that produces a secondary increase of inward current. This sequence is analogous to the rapid activation followed by slower (partial) inactivation produced by depolarizing steps, but with each component, activation and inactivation, relaxing in the opposite direction for hyperpolarizing steps. However, there is a pronounced asymmetry in the gating for depolarizing versus hyperpolarizing steps at any particular voltage range, with depolarizing steps evoking a much larger component of transient current than hyperpolarizing steps of the same size.

Activation and deactivation of subthreshold current were both very rapid, with typical 10-90% rise and fall times of 100-300 μs (Figure 4C, D). Activation and deactivation were rapid both at voltages negative to −70 mV, where the relaxation represents primarily activation and deactivation of persistent sodium current, and also at more depolarized voltages, where there was additional transient current. Thus, gating of steady-state persistent sodium current and subthreshold transient current are both very rapid.

Deactivation of sodium current during IPSP-like voltage changes

Like EPSPs, IPSPs can also be amplified by subthreshold persistent sodium current (Stuart, 1999; Hardie and Pearce, 2006). With IPSPs, the hyperpolarizing synaptic potential produces partial deactivation of a standing inward sodium current, producing additional hyperpolarization beyond that due to the IPSP itself. To evaluate the possible role of transient sodium current to the amplification of IPSPs, we examined the kinetics of the sodium current in response to IPSP-like voltage commands in voltage clamp (Figure 5). IPSP-like voltage changes with an amplitude of 5-mV led to substantial changes of TTX-sensitive current in both Purkinje and CA1 neurons. To evaluate the relative contributions of steady-state and transient components for current, we used the same strategy as with the EPSP-like commands, comparing the current evoked by real-time or 50-times slowed IPSP commands. In contrast to the results with EPSP waveforms, the current evoked by real-time IPSP waveforms (red) was only slightly different from that evoked by slowed commands (black) in either Purkinje neurons (Figure 5A, 5B) or CA1 neurons (Figure 5C, 5D). From the most depolarized holding potentials, there was an “extra” transient component of deactivation in response to the IPSP-like command, but this component was small compared with the overall current, which therefore reflects mainly gating of steady-state persistent sodium current.

Figure 5. TTX-sensitive sodium current evoked by IPSP-like waveforms in Purkinje neurons and CA1 pyramidal neurons.

(A) TTX-sensitive sodium current elicited in a Purkinje neuron by a 5-mV IPSP-like hyperpolarizing voltage command delivered from various holding potentials (red traces) or by the same command slowed by a factor of 50 to evoke only steady-state sodium current (black trace). Each trace is plotted with an offset corresponding to the steady sodium current at the holding potential (before the IPSP waveform), so that steady sodium current at each holding potential is on the same horizontal line; steady sodium currents were 0 pA at −88 mV, +1 at −83 mV,-25 pA at −78 mV, −58 pA at −73 mV, −129 pA at −68 mV,-264 pA at −63 mV, and −385 pA at −58 mV.

(B) Summary of Purkinje neuron data for peak change in sodium current during IPSP-like waveforms evoked from different holding potentials. Red symbols are the mean ± SEM peak total evoked sodium current, black symbols are mean ± SEM steady-state sodium current (n=4).

(C) IPSP-like voltage waveforms elicit transient and steady-state components of sodium current in CA1 neurons similar to those in Purkinje neurons. Steady sodium currents (offsets) were 0 at −83 mV, −4 pA at −78 mV, −18 pA at −73 mV, −47 pA at −68 mV,-89 pA at −63 mV, −126 pA at −58 mV, and −126 pA at −53 mV.

(D) Summary of CA1 neuron data for peak change in sodium current during IPSP-like waveforms evoked from different holding potentials. Red symbols are the mean ± SEM peak total evoked sodium current, black symbols are mean ± SEM steady-state sodium current (n=5).

Single spine stimulation by glutamate uncaging in CA1 dendritic spines

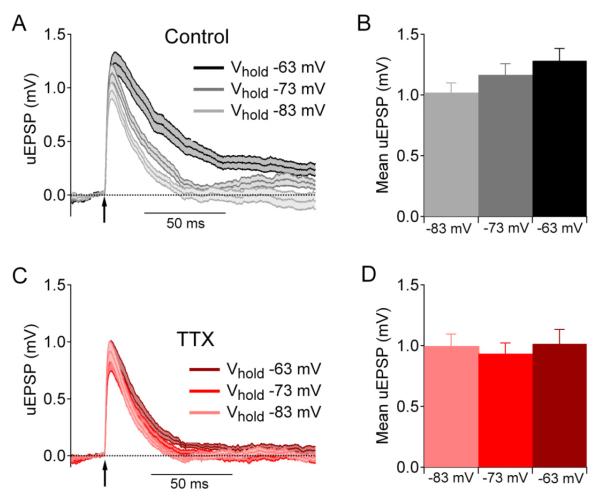

The acutely dissociated neuron preparation allows accurate voltage clamp and rapid solution exchange, which are essential to accurately measure transient sodium current. To examine sodium current involvement in amplifying EPSPs in a more intact setting, we did experiments on CA1 pyramidal neurons in hippocampal brain slices. To test whether sodium current can be evoked by the EPSPs produced by single synaptic inputs, we used 2-photon laser stimulation to uncage MNI-glutamate on single spines in acute hippocampal brain slice. This approach bypasses the presynaptic terminal and therefore allows examination of the effect of TTX on post-synaptic responses. EPSPs were evoked by 2-photon laser uncaging of MNI-glutamate on individual spines either in control solutions or in the presence of TTX to inhibit voltage-activated sodium current. The results with dissociated CA1 neurons predict minimal engagement of either persistent or transient components of sodium current at voltages negative to −80 mV and increasing engagement at more depolarized voltages in the range from −70 to −60 mV. To test the dependence of uncaging-evoked EPSPs (uEPSPs) on membrane potential in this range, the resting potential of the neuron was adjusted to different voltages in each experiment using direct current from the amplifier. Figure 6A shows the mean ± SEM of uEPSPs from spines recorded in control solutions from holding potentials of −83 mV (light grey), −73 mV (grey), and −63 mV (black). The peak voltage change of the uEPSP evoked by stimulation of a single spine was ~1 mV when the membrane potential was −83 mV, and the peak uEPSP increased progressively when the holding potential was depolarized to −73 mV or −63 mV, with a ~20% enhancement when elicited from −63 mV (Figure 6B). The enhancement at −63 mV compared to −83 mV was statistically significant (p=0.024, paired t-test, n=18). Consistent with originating by engagement of voltage-dependent sodium current, this effect was absent when the same experiment was performed in the presence of TTX (Figure 6C,D (p=0.91, n=21, paired t-test comparing −63 mV and −83 mV). As expected from this comparison, the size of the uEPSP was significantly smaller in TTX than control when elicited from −63 mV (p=0.04, unpaired t-test) but not when elicited from −83 mV (p=0.63, unpaired t-test). The effect of TTX to reduce EPSPs evoked in spines of CA1 neurons is similar to previous results seen with stimulation of spines in neocortical pyramidal neurons (Araya et al., 2007).

Figure 6. Somatic voltage changes evoked by 2-photon uncaging of glutamate at single spines of CA1 pyramidal neurons.

(A) uEPSPs recorded in control solutions using holding potentials of −83 mV (light gray), −73 mV (dark gray) or −63 mV (black). Traces plot mean ± SEM for recordings from 5-7 spines.

(B) Peak uEPSP voltage from the different holding potentials in control solutions (mean ± SEM).

(C,D) Same for uEPSPs recorded in the presence of 1 μM TTX (mean ± SEM).

A sodium channel model predicts steady-state and transient current

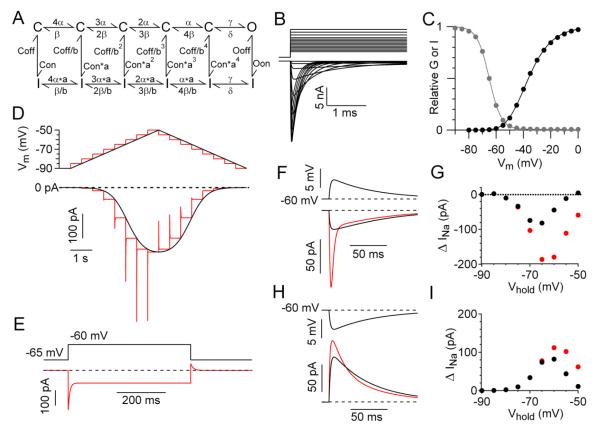

Do the components of subthreshold transient and steady-state sodium current come from the same channels that carry supra-threshold transient current? To explore whether this is likely in principle, we tested the prediction of kinetic models for sodium channel gating. Figure 7A shows a Markov model for sodium channel gating based on previous models formulated to match experimental measurements of supra-threshold transient sodium current (Kuo and Bean, 1992) or both persistent and transient current (Taddese and Bean, 2002; Milescu, 2010) in other types of central neurons. The rate constants were adjusted so that the predicted supra-threshold transient current (Figure 7B) matched the voltage-dependence and kinetics of current recorded in CA1 neurons under our experimental conditions. The model predicted a midpoint of activation of transient current of −36 mV and a midpoint of inactivation of −65 mV (Fig. 7C), corresponding to typical experimental values.

Figure 7. Characteristics of steady-state and transient subthreshold sodium current are predicted in an allosteric model of sodium channel gating.

(A) Model of sodium channel gating. Activation occurs with voltage-dependent transitions between multiple closed states (top row) with strongly voltage-dependent rate constants (α=250*exp(V/24) msec−1, β=12*exp(−V/24) msec−1), considered to correspond to movement of S4 gating regions, followed by a non-voltage-dependent opening transition (γ=250 msec−1, δ= 60 msec−1). Inactivation corresponds to vertical transitions. Inactivation is slow and weak when channels have not activated (Con=0.01 msec−1, Coff=2 msec−1) and becomes faster and more complete in a manner allosterically linked to the extent of activation. The allosteric relationship is expressed by the scaling constants a (2.51) and b (5.32). Inactivation from the open state is fast (Oon=8 msec−1 and with a slow off-rate (Ooff=0.05 msec−1) such that open state inactivation is ~99.4% complete. Microscopic reversibility is ensured by the reciprocal allosteric relationship between activation and inactivation rates for steps corresponding to movement of S4 regions.

(B) Predicted transient currents elicited by steps from a holding potential of −90 mV to a series of voltages from −60 to 0 mV. C) Voltage-dependence of activation (filled circles, relative peak conductance during a 30-msec step) and steady-state availability (open circles). Relative peak conductance was normalized to peak conductance for a step to +30 mV and is fit (black line) by a Boltzmann function raised to the 4th power, (1/(1+exp(−(V+54.1))/10.7)^4. Steady-state availability is fit (gray line) by a first-order Boltzmann function curve, (1/(1+exp(V+65)/4.3).

(D) Predictions of the model for 10 mV/s ramp (black trace) and 5-mV staircase (red trace) voltage protocols. (E) Predictions of the model for sodium current elicited by a 500 ms step from −65 mV to −60 mV and back to −65 mV. Dashed line corresponds to steady-state current at −65 mV (−121 pA). (F) Predictions of the model for activation by an EPSP waveform of transient plus steady-state sodium current (red trace) compared to steady-state current alone (black), calculated from the predicted steady-state current at each voltage. (G) Peak steady-state (black symbols) and total (red symbols) sodium current predicted by the model in response to 5-mV EPSP waveforms delivered from a range of holding potentials. (H) Predictions of the model for activation by an IPSP waveform of transient plus steady-state sodium current (red trace) compared to steady-state current alone (black). (I) Peak steady-state (black symbols) and total (red symbols) sodium current predicted by the model in response to IPSP waveforms delivered from a range of holding potentials.

We found that the model predicts both subthreshold steady-state and subthreshold transient current, with kinetics and voltage-dependence similar to the experimentally measured currents. The model predicts steady-state conductance with a midpoint of −63 mV and a slope factor of 3.8, similar to experimental values. The predicted maximal steady state current is about 1% of maximal suprathreshold transient current. Similar to the experimental results, a staircase of 5-mV depolarizations at subthreshold voltages elicits a component of transient current that is minimal at voltages below −70 mV but increasingly large at voltages between −70 and −50 mV (Fig. 7D). The current engaged by EPSP waveforms includes a prominent transient as well as steady-state component (Figure 7E), with the largest contribution of transient current at voltages depolarized to −70 mV (Figure 7F), as was seen experimentally. The model predicts the asymmetry in transient current evoked by activation versus deactivation (Figure 7G) and predicts that the sodium current engaged by IPSP waveforms is primarily from steady-state and not transient behavior of the channels (Figure 7H,I).

Discussion

These results show that voltage-dependent sodium channels in central neurons can activate to carry transient sodium current at voltages as negative as −70 mV, well below the typical spike threshold near −55 mV. The characteristics of subthreshold transient sodium current were very similar in GABAergic Purkinje neurons and glutamatergic CA1 pyramidal neurons, except that currents were on average larger in Purkinje neurons. In both cell types, the transient component of subthreshold sodium current can be engaged by EPSP waveforms, showing that both transient and steady-state components of sodium current are involved in the ability of TTX-sensitive sodium current to amplify EPSPs.

The results in CA1 neurons fit well with a previous observation of subthreshold transient sodium current made using intact CA1 neurons studied in brain slice (Axmacher and Miles, 2004). Despite the smaller membrane area of the dissociated cell body preparation we used, the subthreshold transient currents were much larger than in the slice recordings, and they were also evident at more negative voltages and much faster in both activation and inactivation. These differences are all likely to result from the faster voltage clamp possible in dissociated cells.

Voltage-dependence of persistent current

The results also show that subthreshold steady-state sodium current in central neurons can activate at more negative voltages than previously appreciated, with significant current evident at voltages between −80 and −75 mV, ~10 mV below the voltages where transient current was first evident. Thus, at voltages below −70 mV, sodium current engaged by EPSP waveforms is entirely due to steady-state “persistent” sodium current, while both transient and persistent components of current are engaged at more depolarized voltages.

The steady-state component of sodium current (determined by slow ramps of 10 mV/s) activated with typical midpoints between −65 and −60 mV and with steep voltage-dependence. Like the properties of subthreshold transient current, the voltage-dependence of steady-state current was very similar in Purkinje neurons (midpoint −62 ± 1 mV, slope factor 4.9 ± 0.1 mV) and CA1 neurons (midpoint −62 ± 1 mV, slope factor 4.4 ± 0.2 mV). The average midpoint of −62 mV for steady-state current in CA1 pyramidal neurons is substantially more negative than the midpoint near −50 mV found in a previous study of CA1 neurons (French et al. 1990), the data widely used for modeling functional roles of persistent sodium current in central neurons (e.g. Vervaeke et al., 2006; Hu et al., 2009). The difference is likely because of differences in recording solutions and conditions. Our recordings were made at 37 °C using a potassium methanesulfonate-based internal solution designed to mimic physiological ionic conditions, while the earlier measurements were at room temperature using a CsF-based internal solution that can facilitate seals but may alter the voltage-dependence of channels. Also, the earlier experiments used external solutions containing 2 mM Ca2+ and 0.3-1 mM Cd2+ (along with 2 mM Mg2+), while our external solution contained 1.5 mM Ca2+, 1 mM Mg2+ and no Cd2+, relying instead on TTX-subtraction to separate sodium current from calcium current. As shown by Yue et al. (2005), higher Ca2+ and added Cd2+ both shift the voltage-dependence of persistent sodium current in the depolarizing direction, likely as a result of surface charge screening (Hille, 2001). The smaller difference between the voltage-dependence we found and the midpoint of −56 mV reported by Yue et al. (2005) for persistent sodium current in dissociated CA1 neurons using an external solution containing 1.2 mM Ca2+ calcium and no added Cd2+ is likely due to the differences in internal solutions (potassium methanesulfonate versus CsF), temperature (37 °C versus room temperature), and voltage protocol used to define steady-state properties (ramps of 10 mV/s versus 50 mV/s).

Though different from the previous voltage-clamp studies in CA1 neurons using CsF-based internal solutions, the voltage-dependence for persistent sodium current we observed fits well with previous reports made in current clamp under more physiological conditions. For example, in microelectrode recordings from CA1 neurons in slice, Hotson et al. (1979) observed a TTX-sensitive change in resistance attributable to persistent sodium current starting at −70 mV, almost 20 mV below the spike threshold of −53 mV.

Recently, Huang and Trussell (2008) showed the presence of persistent sodium current in the presynaptic terminal of the calyx of Held that activates detectably at voltages as negative as −85 mV, similar to the threshold for detection near −80 mV that we saw in Purkinje neurons. The current in the calyx of Held has a shallower voltage-dependence (slope factor of 9.8 mV) and more depolarized midpoint (−51 mV) than in Purkinje neurons and CA1 neurons (slope factors of 4.4-4.9 mV and midpoint of −62 mV). The shallow voltage-dependence in the calyx may represent the summation of different components with different midpoints, as suggested by Huang and Trussell. Purkinje neurons, CA1 neurons, and the calyx of Held all express Nav1.6 channels (Raman et al., 1997; Leão et al., 2005; Royeck et al., 2008; Lorinz and Nusser, 2008), which appear to produce an unusually large component of persistent sodium current compared to other sodium channels (Raman et al., 1997; Maurice et al., 2001; Enomoto et al., 2007; Royeck et al., 2008; Osorio et al., 2010). In both Purkinje neurons (Raman et al., 1997) and CA1 neurons (Royeck et al., 2008), the contribution to persistent current of other channel types, measured in Nav1.6-null animals, occurs with very similar voltage-dependence to the wild-type persistent current (i.e. including Nav1.6), suggesting that in these cells persistent current arises from both a Nav1.6-based major component and a second component with nearly identical steep voltage dependence. In the calyx of Held, the shallower voltage-dependence and more depolarized midpoint could reflect the contribution of second component with more depolarized voltage-dependence than is typical of current from Nav1.6 channels.

Rapid activation and deactivation of persistent sodium current

The analysis of gating kinetics in Figure 4 shows that the kinetics of activation and deactivation of both persistent sodium current and subthreshold transient sodium current are extremely rapid. For voltages near −80 mV, where there is only persistent current but no transient current, current activates and deactivates within ~250 μs. At more depolarized voltages, where there is activation of both persistent and transient components of current, kinetics are even faster, with 10-90% completion in ~ 100-150 μs. This is an upper limit of the time required for gating, because it is close to the resolution of between 80-150 μs for the speed with which voltage changes are imposed on the cell (estimated by changes in tail currents produced by sudden changes in driving force). The rapid activation of both persistent and transient components of subthreshold sodium current mean that both can be engaged essentially instantaneously by EPSP waveforms, even when these are very rapid.

Dependence of subthreshold sodium current on rate of depolarization

Previous work has shown that the magnitude of subthreshold persistent sodium current is larger with faster ramp speeds, typically tested in the range between 10 mV/s and 100 mV/s (Fleidervish and Gutnick, 1996; Magistretti and Alonso, 1999; Wu et al., 2005; Kuo et al., 2006). The interpretation given to this effect previously has been that persistent sodium current is subject to a process of slow inactivation that occurs with slower ramp speeds. Our results suggest a different interpretation, that current evoked by slower ramp speeds represents true steady-state persistent current and that faster ramp speeds additionally activate increasing amounts of transient sodium current. In support of this interpretation, the current evoked by a smooth 10 mV/s ramp closely matched the steady-state current at the end of each 500-msec 5-mV voltage step in the staircase protocol (Figure 1). Also supporting this interpretation, currents evoked by fast and slow ramps differ least for small depolarizations and most for large depolarizations, resulting in more depolarized midpoints for the current evoked by faster ramps (Fleidervish and Gutnick, 1996). This effect is expected from our results, because transient current is absent at the more hyperpolarized voltages but increasingly prominent at more depolarized (but still subthreshold) voltages, so that its activation would result in a depolarizing shift of the midpoint of ramp-evoked current with faster ramps. The contribution of transient current to the larger current evoked by faster ramps does not preclude an additional effect from slow inactivation of true persistent current, which clearly exists based on the ability of long prepulses to reduce current evoked by even slow ramps (Fleidervish and Gutnick, 1996; Magistretti and Alonso, 1999). In some cells, we saw such an effect manifested as smaller steady-state currents during the “down ramp” following an “up ramp”, both at 10 mV/s, although this effect was often very small (e.g. Fig. 4A).

Subthreshold transient and persistent current from standard sodium channels

The kinetic model for sodium channel gating in Figure 7 shows that subthreshold persistent and subthreshold transient current can both originate from the same channels that carry supra-threshold transient current. This argues that at least in CA1 pyramidal neurons - and in Purkinje neurons, in which subthreshold currents are similar - there is no need to invoke sodium channels with special properties to account for persistent sodium current or subthreshold transient current. Rather, these subthreshold currents may simply reflect gating behavior at subthreshold voltages of the “standard” sodium channels that produce the transient suprathreshold sodium current. This origin of subthreshold sodium current predicts that it should be present in all neurons, with a magnitude of persistent current corresponding to ~0.5-1% of maximal suprathreshold transient current (Fig 7; Taddese and Bean, 2001). In some neurons, such subthreshold current may be augmented by additional more specialized mechanisms of persistent current, such as special gating modes during which channels enter long-lived open states (Alzheimer et al., 1993), which seem most prominent in neurons with particularly large persistent current (Magistretti et al., 1999; Magistretti and Alonso, 2002).

The model in Figure 7 suggests that the distinction between components of sodium current termed “persistent” or “transient” is to some extent artificial, because according to the model, all components of sodium current simply reflect time-varying occupancy of the open state of a single type of channel in response to a given voltage change. Nevertheless, a distinction between “steady-state” or “persistent” and “transient” components of current can be made phenomenologically. Steady-state current corresponds to occupancy of the open state when equilibrium among the various closed, inactivated, and open states is reached at steady-state at any given voltage, and transient current corresponds to any extra current flowing during the approach to steady-state when the voltage change is too rapid for equilibrium to be reached at each voltage. In this terminology, “steady-state” current corresponds to what has traditionally been called “persistent” current, as defined by slow ramps, and we use the terms interchangeably.

Limitations of the model

We were somewhat surprised that a model of a single uniform population of sodium channels could give a good prediction of the experimentally observed currents, because CA1 pyramidal neurons (whose experimental data was used to tune the model) likely express current from multiple types of sodium channels. Subthreshold current in CA1 neurons is partly from Nav1.6 channels (Royeck et al., 2008), which are prominently expressed in many neuronal types with large persistent currents (e.g. Raman et al., 1997; Maurice et al., 2001; Enomoto et al., 2007; Osorio et al., 2010; Gittis et al., 2009; Kodama et al., 2012) but persistent sodium current in CA1 pyramidal neurons from Nav1.6-null mice is reduced by only ~40% (Royeck et al., 2008), suggesting substantial contributions from other channel types also. The persistent sodium current in the Nav1.6-null animals has almost identical voltage-dependence with that in wild-type animals (Royeck et al., 2008) suggesting that the voltage-dependence of non-Nav1.6 channels must be very similar to that from Nav1.6. This makes it plausible that a single model can account reasonably well for current from mixed sources.

The model does not account for resurgent sodium current, a component of sodium current expressed in Purkinje neurons (Raman and Bean, 1997) and some CA1 pyramidal neurons (Castelli et al., 2007; Royeck et al., 2008). Resurgent current requires depolarizations depolarized to −30 mV to be activated significantly (Raman and Bean, 2001; Aman and Raman, 2010), and should be minimally engaged by the protocols we used for exploring subthreshold current or by EPSP waveforms (Fig. 7D-I), where all voltages were below −40 mV.

The model also does not account for a process of slow inactivation, which affects both transient and persistent sodium current (Fleidervish and Gutnick, 1996; Mickus et al., 1999; Aman and Raman, 2007) and produces roughly parallel changes in the two components (Taddese and Bean, 2001; Do and Bean, 2003). Modeling slow inactivation accurately (e.g. Menon et al., 2009; Milescu et al., 2011) was not feasible as we did not use protocols designed to characterize it under our conditions. In many neurons slow inactivation was minimal with the protocols we used (e.g. Fig. 4A), so it is unlikely to be important for the essential relationship between persistent and transient current studied here.

Implications for EPSP-spike coupling and spike timing precision

TTX-sensitive sodium current has been shown to amplify EPSPs in many neuronal cell types, including cortical pyramidal neurons (Deisz et al., 1991; Stuart and Sakmann, 1995; Gonzáles-Burgos and Barrionuevo, 2001), hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons (Lipowski et al., 1996; Andreasen and Lambert, 1999; Fricker and Miles, 2000; Axmacher and Miles, 2004), and hippocampal interneurons (Fricker and Miles, 2000). Our experiments using 2-photon glutamate uncaging show that even the small depolarizations (~ 1 mV) resulting from stimulation of single spines can engage sodium current in CA1 neurons, and the dependence of this effect on membrane potential fit very well with the voltage-clamp results in dissociated neurons.

Because subthreshold transient current is more effectively engaged by faster depolarizations, our results predict that the amount of sodium current activated by an EPSP - and therefore the amount of sodium current-dependent amplification - will depend strongly on the rate of rise of the EPSP, with faster-rising EPSPs activating more transient current and being amplified more effectively. The dependence of amplification on the rate of depolarization of the EPSP is expected to be highly non-linear, because faster-rising EPSPs will evoke more transient sodium current which will in turn increase the rate of depolarization. Such non-linear positive feedback at subthreshold voltages is similar to the explosively positive feedback occurring with activation of suprathreshold sodium current during the action potential. In fact, the comparison suggests that under some conditions there may be no clear distinction between subthreshold and suprathreshold amplification of depolarization by sodium current. In recordings from cortical neurons studied in vivo with spiking evoked by sensory stimuli, there is a broad variation in apparent spike threshold caused by an inverse relation between spike threshold and the rate of preceding membrane depolarization by EPSPs (Azouz and Gray, 2000; Wilent and Contreras, 2005a), an effect also seen in recordings from neurons in slice stimulated using current injections (Wickens and Wilson, 1998; de Polavieja et al., 2005). The higher efficacy of fast-rising than slow-rising depolarizations to trigger action potentials enhances the precision of spike timing (Mainen and Sejnowski, 1995; Nowak et al., 1997; Axmacher and Miles, 2004) and, in vivo, can help synchronize the firing of cortical neurons (e.g. Wilent and Contreras, 2005b; Cardin et al., 2010). The activation of transient sodium current at subthreshold voltages likely contributes to this effect by producing sensitivity to the rate of membrane depolarization that would not be present with amplification by persistent sodium current alone.

In many neurons, EPSPs can be modified by voltage-dependent potassium currents that activate at subthreshold voltages, notably A-type potassium current (e.g. Ramakers and Storm, 2002) and M-current (e.g. Hu et al., 2007). The interaction of these potassium currents and subthreshold sodium current to modify EPSPs is likely to be complex and to depend on both the kinetics and relative degree of expression in dendrites, soma, and axon (e.g. Shah et al., 2011). In general, however, it can be expected that sodium current will be activated faster than either M-current or A-type potassium current. The fast activation of inward sodium current followed by slower activation of outward potassium current can produce extra enhancement of firing precision, as has been shown experimentally in CA1 neurons (Axmacher and Miles, 2004).

Selective amplification of EPSPs vs IPSPs

Subthreshold TTX-sensitive sodium currents can amplify the amplitude of IPSPs as well as EPSPs (Stuart, 1999; Hardie and Pearce, 2006). IPSP amplification arises by deactivation rather than inactivation of sodium current: steady-state sodium current present at the resting potential turns off during the hyperpolarization of the IPSP, resulting in a larger change in voltage than would otherwise occur. We found gating of sodium channels by IPSP waveforms delivered from holding potentials as negative as −75 mV, with increasing size of the gated sodium current from more depolarized starting potentials. However, although both EPSP and IPSP waveforms produced changes in TTX-sensitive sodium current, we found a pronounced asymmetry in the effectiveness of amplification, with greater engagement of sodium current by EPSPs. This effect is because EPSP waveforms engage large transient components of current (in addition to steady-state current) while IPSPs engage very little transient current. This asymmetry in depolarizing versus hyperpolarizing synaptic events, which is most pronounced at membrane potentials between −65 and −50 mV, where relative transient current is greatest, could sharpen the precision of spike timing by producing selective rapid boosting of fast EPSPs over IPSPs. This effect should be greater the faster the rise time of the EPSPs, which would occur under conditions where the membrane time constant is short as a consequence of on-going concurrent excitatory and inhibitory input resulting in high total synaptic conductance (Destexhe and Paré, 1999). This is often the situation during normal operation of the cortex (Destexhe et al., 2003; Shu et al., 2003; Haider et al., 2006, 2009).

Implications for epilepsy and its treatment

Amplification of EPSPs by subthreshold sodium current results in enhanced temporal summation that can lead to sustained spike discharge (Artinian et al., 2011), which may contribute to epileptic behavior. A number of sodium channel mutations associated with epilepsy produce enhanced persistent sodium current (reviewed by Stafstrom, 2007). Interestingly, chronic epileptic-like activity can lead to upregulation of persistent sodium current (e.g. Agrawal et al., 2003; Vreugdenhil et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2011), potentially constituting a positive feedback mechanism for triggering further seizures. If persistent sodium current, subthreshold transient current and suprathreshold transient current all arise from a single population of channels, as suggested by our gating model, any drug that blocks one component is likely to affect the others to at least some degree. However, by understanding how each of the components arises from particular gating-state transitions and how each helps control overall excitability, it may be possible to identify or design drugs that can bind to channels in a state-dependent manner to optimally disrupt pathological firing (e.g. that arising from enhanced subthreshold current) with minimal effect on normal spiking activity.

Experimental Procedures

Preparation of cells and voltage clamp recording

Cerebellar Purkinje neurons and hippocampal CA1 neurons were acutely isolated from the brains of Black Swiss and Swiss Webster mice (P14-20) as previously described (Carter and Bean, 2009). Whole-cell recordings were made with a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices) interfaced with a Digidata 1322 A/D converter using pClamp 9.0 software (Molecular Devices). Data were filtered at 10 kHz with a 4-pole Bessel filter (Warner Instruments) and sampled at 50-200 kHz. Electrodes (1.5-4.0 MΩ) were filled with an internal solution consisting of 140 mM potassium methanesulfonate, 10 mM NaCl, 1.8 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 10 mM HEPES, 14 mM creatine phosphate (Tris salt), 0.3 mM Tris-GTP, pH adjusted to 7.4 with KOH. Reported voltages are corrected for a −8 mV liquid junction potential between this solution and the Tyrode’s bath solution (155 mM NaCl, 3.5 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM glucose, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.5 mM CaCl2, pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH), measured using a flowing 3 M KCl reference electrode (Neher, 1992).

The standard external recording solution was Tyrode’s solution with 10 mM tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA) added to reduce potassium currents. Solutions were applied through quartz flow pipes (250 μm internal diameter, 350 μm external diameter) glued onto a temperature-regulated aluminum rod. Experiments were done at 37 ± 1 °C. Sodium current was isolated by subtraction of traces recorded in control solutions and then in the presence of 1 μM tetrodotoxin (TTX).

Analysis of ramp currents

Steady-state current was elicited by slow ramps from −98 to −38 mV delivered at 10 mV/s. Sodium conductance was calculated as GNa=INa/(V-VNa) with the reversal potential VNa = +63 mV measured using these internal and external solutions. The steady-state sodium conductance was fit with a Boltzmann function, GMax/(1+exp[−{V−Vh}/k]) where GMax is the maximal conductance, Vh is the voltage where the conductance is half maximal, and k is the slope factor.

EPSP-like waveform

EPSP-like voltage commands were created as the product of two exponentials, (1−exp[−t/τrise])*exp(−t/τdecay). τrise was 2 ms and τdecay was 65 ms, chosen to be similar to EPSP rise and decay times reported in the literature (Isope and Barbour, 2002; Mittmann and Hausser, 2007). The amplitude of the EPSP-like waveform was set to 5-mV (or −5-mV for IPSP-like waveforms). The steady-state sodium current in response to the EPSP-like voltage change was measured by using a command waveform slowed by a factor of 50, as in Figure 3A. In some experiments, the steady-state current was instead calculated by using the current evoked by slow voltage ramps to look up the current at each voltage. The two methods gave nearly identical results in cases where both were used. When the slowed command waveform was used, the resulting current was smoothed by averaging over time periods corresponding to changes in command voltage of 0.03 mV.

2-photon glutamate uncaging in acute hippocampal slice

Transverse hippocampal slices were prepared from postnatal day 15-18 C57/Blk6 mice as previously described (Giessel and Sabatini, 2010). Patch pipettes were filled with an internal solution consisting of 140 mM potassium methanesulfonate, 8 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 5 mM MgATP, 0.4 mM Na2GTP, pH adjusted to 7.3 with KOH, with 50 μM Alexa Fluor 594. Recordings were made using an Axoclamp 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments), filtered at 5 kHz and sampled at 10 kHz.

A custom built 2-photon laser scanning microscope based on a BX51W1 microscope (Olympus) was used as described previously for imaging spines and producing localized uncaging of glutamate (Carter and Sabatini, 2004). Two Ti-Sapphire lasers (Mira/Verdi, Coherent) tuned to 840 and 725 nm were used for imaging and glutamate uncaging, respectively. Slices were bathed in ACSF containing 3.75 mM MNI-glutamate (Tocris Cookson) and 10 μM d-serine. The uncaging laser pulse duration was 0.5 ms and power delivered to each spine was adjusted to bleach ~30% of the red fluorescence in the spine head. After laser power was set, each spine was probed to find the uncaging spot that gave the largest somatic current response (in voltage clamp mode). The amplifier was then switched to current clamp and the holding potential was adjusted with steady current injection to each of three different potentials, with trials at each potential interleaved. Uncaging-evoked EPSPs from each neuron were sorted according to the holding potential and 5-7 responses at each holding voltage were averaged. Uncaging events that evoked a spike immediately were excluded from analysis.

Modeling

Sodium channel kinetics were modeled using a Markov model that incorporates an allosteric relationship between activation and inactivation, using the same structure as previous models for sodium current recorded in other cell types under different ionic conditions and temperature (Kuo and Bean, 1994; Taddese and Bean, 2002; Milescu et al., 2010). Activation is modeled as a series of strongly voltage-dependent steps considered to correspond to sequential movement of the four S4 regions in the channel (Catterall, 2000), followed by an final opening step (with no intrinsic voltage-dependence) that occurs after movement of all four S4 regions. Inactivation is envisioned as corresponded to binding of a particle (i.e. the IFM-containing loop between domains III and IV; Catterall, 2000) that binds weakly when no S4 regions have activated and progressively more tightly when one or more S4 regions have activated. With this model, inactivation is coupled in an allosteric manner to activation but it is not obligatory for channels to open for inactivation to occur (Armstrong, 2006). Parameters were adjusted by trial and error to match the voltage-dependence and kinetics of activation and inactivation and voltage-dependence of steady-state current, using the data from our experimental recordings of current from acutely dissociated hippocampal CA1 neurons at 37 °C.

Statistics

Data are summarized as mean ± standard error of the mean.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Zayd Khaliq for discussion and helpful suggestions. Supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01-NS036855 to BPB, R01-NS046579 to BLS, F31-NS064630 to BCC, and F31-NS065647 to AJG). AJG was also supported by a Quan Predoctoral Fellowship.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agrawal N, Alonso A, Ragsdale DS. Increased persistent sodium currents in rat entorhinal cortex layer V neurons in a post-status epilepticus model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2003;44:1601–1604. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2003.23103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer C, Schwindt PC, Crill WE. Modal gating of Na+ channels as a mechanism of persistent Na+ current in pyramidal neurons from rat and cat sensorimotor cortex. J Neurosci. 1993;13:660–673. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00660.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman TK, Raman IM. Subunit dependence of Na channel slow inactivation and open channel block in cerebellar neurons. Biophys J. 2007;92:1938–1951. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.093500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman TK, Raman IM. Inwardly permeating Na ions generate the voltage dependence of resurgent Na current in cerebellar Purkinje neurons. J Neurosci. 2010;30:5629–5634. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0376-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen M, Lambert JD. Somatic amplification of distally generated subthreshold EPSPs in rat hippocampal pyramidal neurones. J Physiol. 1999;519(Pt 1):85–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0085o.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araya R, Nikolenko V, Eisenthal KB, Yuste R. Sodium channels amplify spine potentials. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12347–12352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705282104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong CM. Na channel inactivation from open and closed states. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17991–17996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607603103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artinian J, Peret A, Marti G, Epsztein J, Crepel V. Synaptic kainate receptors in interplay with INaP shift the sparse firing of dentate granule cells to a sustained rhythmic mode in temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci. 31:10811–10818. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0388-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axmacher N, Miles R. Intrinsic cellular currents and the temporal precision of EPSP-action potential coupling in CA1 pyramidal cells. J Physiol. 2004;555:713–725. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.052225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azouz R, Gray CM. Dynamic spike threshold reveals a mechanism for synaptic coincidence detection in cortical neurons in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8110–8115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130200797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azouz R, Jensen MS, Yaari Y. Ionic basis of spike after-depolarization and burst generation in adult rat hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells. J Physiol. 1996;492(Pt 1):211–223. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan MD, Wilson CJ. Mechanisms underlying spontaneous oscillation and rhythmic firing in rat subthalamic neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7617–7628. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07617.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardin JA, Kumbhani RD, Contreras D, Palmer LA. Cellular mechanisms of temporal sensitivity in visual cortex neurons. J Neurosci. 2010;30:3652–3662. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5279-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AG, Sabatini BL. State-dependent calcium signaling in dendritic spines of striatal medium spiny neurons. Neuron. 2004;44:483–493. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter BC, Bean BP. Sodium entry during action potentials of mammalian neurons: incomplete inactivation and reduced metabolic efficiency in fast-spiking neurons. Neuron. 2009;64:898–909. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter BC, Bean BP. Incomplete inactivation and rapid recovery of voltage-dependent sodium channels during high-frequency firing in cerebellar Purkinje neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2011;105:860–871. doi: 10.1152/jn.01056.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelli L, Nigro MJ, Magistretti J. Analysis of resurgent sodium-current expression in rat parahippocampal cortices and hippocampal formation. Brain Res. 2007;1163:44–55. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA. From ionic currents to molecular mechanisms: the structure and function of voltage-gated sodium channels. Neuron. 2000;26:13–25. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Su H, Yue C, Remy S, Royeck M, Sochivko D, Opitz T, Beck H, Yaari Y. An increase in persistent sodium current contributes to intrinsic neuronal bursting after status epilepticus. J Neurophysiol. 2011;105:117–129. doi: 10.1152/jn.00184.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crill WE. Persistent sodium current in mammalian central neurons. Annu Rev Physiol. 1996;58:349–362. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.58.030196.002025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Angelo E, De Filippi G, Rossi P, Taglietti V. Ionic mechanism of electroresponsiveness in cerebellar granule cells implicates the action of a persistent sodium current. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:493–503. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.2.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Polavieja GG, Harsch A, Kleppe I, Robinson HP, Juusola M. Stimulus history reliably shapes action potential waveforms of cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5657–5665. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0242-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deisz RA, Fortin G, Zieglgansberger W. Voltage dependence of excitatory postsynaptic potentials of rat neocortical neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1991;65:371–382. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.65.2.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Negro CA, Koshiya N, Butera RJ, Jr., Smith JC. Persistent sodium current, membrane properties and bursting behavior of pre-botzinger complex inspiratory neurons in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:2242–2250. doi: 10.1152/jn.00081.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Destexhe A, Paré D. Impact of network activity on the integrative properties of neocortical pyramidal neurons in vivo. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:1531–1547. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.4.1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Destexhe A, Rudolph M, Paré D. The high-conductance state of neocortical neurons in vivo. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:739–751. doi: 10.1038/nrn1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do MT, Bean BP. Subthreshold sodium currents and pacemaking of subthalamic neurons: modulation by slow inactivation. Neuron. 2003;39:109–120. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00360-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enomoto A, Han JM, Hsiao CF, Chandler SH. Sodium currents in mesencephalic trigeminal neurons from Nav1.6 null mice. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98:710–719. doi: 10.1152/jn.00292.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleidervish IA, Gutnick MJ. Kinetics of slow inactivation of persistent sodium current in layer V neurons of mouse neocortical slices. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:2125–2130. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.3.2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French CR, Sah P, Buckett KJ, Gage PW. A voltage-dependent persistent sodium current in mammalian hippocampal neurons. J Gen Physiol. 1990;95:1139–1157. doi: 10.1085/jgp.95.6.1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricker D, Miles R. EPSP amplification and the precision of spike timing in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 2000;28:559–569. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giessel AJ, Sabatini BL. M1 muscarinic receptors boost synaptic potentials and calcium influx in dendritic spines by inhibiting postsynaptic SK channels. Neuron. 2010;68:936–947. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittis AH, Moghadam SH, du Lac S. Mechanisms of sustained high firing rates in two classes of vestibular nucleus neurons: differential contributions of resurgent Na, Kv3, and BK currents. J Neurophysiol. 104:1625–1634. doi: 10.1152/jn.00378.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Burgos G, Barrionuevo G. Voltage-gated sodium channels shape subthreshold EPSPs in layer 5 pyramidal neurons from rat prefrontal cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:1671–1684. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.4.1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutfreund Y, yarom Y, Segev I. Subthreshold oscillations and resonant frequency in guinea-pig cortical neurons: physiology and modelling. J Physiol. 1995;483(Pt 3):621–640. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider B, Duque A, Hasenstaub AR, McCormick DA. Neocortical network activity in vivo is generated through a dynamic balance of excitation and inhibition. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4535–4545. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5297-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider B, McCormick DA. Rapid neocortical dynamics: cellular and network mechanisms. Neuron. 2009;62:171–189. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie JB, Pearce RA. Active and passive membrane properties and intrinsic kinetics shape synaptic inhibition in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8559–8569. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0547-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Ion channels of excitable membranes. Sinauer; Sunderland, MA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hotson JR, Prince DA, Schwartzkroin PA. Anomalous inward rectification in hippocampal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1979;42:889–895. doi: 10.1152/jn.1979.42.3.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Vervaeke K, Graham LJ, Storm JF. Complementary theta resonance filtering by two spatially segregated mechanisms in CA1 hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:14472–14483. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0187-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Vervaeke K, Storm JF. Two forms of electrical resonance at theta frequencies, generated by M-current, h-current and persistent Na+ current in rat hippocampal pyramidal cells. J Physiol. 2002;545:783–805. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.029249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Vervaeke K, Storm JF. M-channels (Kv7/KCNQ channels) that regulate synaptic integration, excitability, and spike pattern of CA1 pyramidal cells are located in the perisomatic region. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1853–1867. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4463-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Trussell LO. Control of presynaptic function by a persistent Na(+) current. Neuron. 2008;60:975–979. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isope P, Barbour B. Properties of unitary granule cell-->Purkinje cell synapses in adult rat cerebellar slices. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9668–9678. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-22-09668.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay AR, Sugimori M, Llinas R. Kinetic and stochastic properties of a persistent sodium current in mature guinea pig cerebellar Purkinje cells. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:1167–1179. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.3.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama T, Guerrero S, Shin M, Moghadam S, Faulstich M, du Lac S. Neuronal Classification and Marker Gene Identification via Single-Cell Expression Profiling of Brainstem Vestibular Neurons Subserving Cerebellar Learning. J Neurosci. 32:7819–7831. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0543-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo CC, Bean BP. Na+ channels must deactivate to recover from inactivation. Neuron. 1994;12:819–829. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90335-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo JJ, Lee RH, Zhang L, Heckman CJ. Essential role of the persistent sodium current in spike initiation during slowly rising inputs in mouse spinal neurones. J Physiol. 2006;574:819–834. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.107094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leão RM, Kushmerick C, Pinaud R, Renden R, Li GL, Taschenberger H, Spirou G, Levinson SR, von Gersdorff H. Presynaptic Na+ channels: locus, development, and recovery from inactivation at a high-fidelity synapse. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3724–3738. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3983-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipowsky R, Gillessen T, Alzheimer C. Dendritic Na+ channels amplify EPSPs in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:2181–2191. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.4.2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorincz A, Nusser Z. Cell-type-dependent molecular composition of the axon initial segment. J Neurosci. 2008;28:14329–14340. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4833-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magistretti J, Alonso A. Biophysical properties and slow voltage-dependent inactivation of a sustained sodium current in entorhinal cortex layer-II principal neurons: a whole-cell and single-channel study. J Gen Physiol. 1999;114:491–509. doi: 10.1085/jgp.114.4.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magistretti J, Alonso A. Fine gating properties of channels responsible for persistent sodium current generation in entorhinal cortex neurons. J Gen Physiol. 2002;120:855–873. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magistretti J, Ragsdale DS, Alonso A. High conductance sustained single-channel activity responsible for the low-threshold persistent Na(+) current in entorhinal cortex neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7334–7341. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07334.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainen ZF, Sejnowski TJ. Reliability of spike timing in neocortical neurons. Science. 1995;268:1503–1506. doi: 10.1126/science.7770778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurice N, Tkatch T, Meisler M, Sprunger LK, Surmeier DJ. D1/D5 dopamine receptor activation differentially modulates rapidly inactivating and persistent sodium currents in prefrontal cortex pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2268–2277. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-07-02268.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon V, Spruston N, Kath WL. A state-mutating genetic algorithm to design ion-channel models. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16829–16834. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903766106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mickus T, Jung H, Spruston N. Properties of slow, cumulative sodium channel inactivation in rat hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Biophys J. 1999;76:846–860. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77248-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milescu LS, Yamanishi T, Ptak K, Smith JC. Kinetic properties and functional dynamics of sodium channels during repetitive spiking in a slow pacemaker neuron. J Neurosci. 2010;30:12113–12127. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0445-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittmann W, Hausser M. Linking synaptic plasticity and spike output at excitatory and inhibitory synapses onto cerebellar Purkinje cells. J Neurosci. 2007;27:5559–5570. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5117-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E. Correction for liquid junction potentials in patch clamp experiments. Methods Enzymol. 1992;207:123–131. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)07008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak LG, Sanchez-Vives MV, McCormick DA. Influence of low and high frequency inputs on spike timing in visual cortical neurons. Cereb Cortex. 1997;7:487–501. doi: 10.1093/cercor/7.6.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osorio N, Cathala L, Meisler MH, Crest M, Magistretti J, Delmas P. Persistent Nav1.6 current at axon initial segments tunes spike timing of cerebellar granule cells. J Physiol. 2010;588:651–670. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.183798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakers GM, Storm JF. A postsynaptic transient K(+) current modulated by arachidonic acid regulates synaptic integration and threshold for LTP induction in hippocampal pyramidal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10144–10149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152620399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman IM, Bean BP. Resurgent sodium current and action potential formation in dissociated cerebellar Purkinje neurons. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4517–4526. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-12-04517.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman IM, Bean BP. Inactivation and recovery of sodium currents in cerebellar Purkinje neurons: evidence for two mechanisms. Biophys J. 2001;80:729–737. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76052-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman IM, Sprunger LK, Meisler MH, Bean BP. Altered subthreshold sodium currents and disrupted firing patterns in Purkinje neurons of Scn8a mutant mice. Neuron. 1997;19:881–891. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80969-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royeck M, Horstmann MT, Remy S, Reitze M, Yaari Y, Beck H. Role of axonal NaV1.6 sodium channels in action potential initiation of CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:2361–2380. doi: 10.1152/jn.90332.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwindt PC, Crill WE. Amplification of synaptic current by persistent sodium conductance in apical dendrite of neocortical neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1995;74:2220–2224. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.5.2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah MM, Migliore M, Brown DA. Differential effects of Kv7 (M-) channels on synaptic integration in distinct subcellular compartments of rat hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J Physiol. 2011;589:6029–6038. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.220913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu Y, Hasenstaub A, Badoual M, Bal T, McCormick DA. Barrages of synaptic activity control the gain and sensitivity of cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10388–10401. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-32-10388.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafstrom CE. Persistent sodium current and its role in epilepsy. Epilepsy Curr. 2007;7:15–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1535-7511.2007.00156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart G. Voltage-activated sodium channels amplify inhibition in neocortical pyramidal neurons. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:144–150. doi: 10.1038/5698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart G, Sakmann B. Amplification of EPSPs by axosomatic sodium channels in neocortical pyramidal neurons. Neuron. 1995;15:1065–1076. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90095-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddese A, Bean BP. Subthreshold sodium current from rapidly inactivating sodium channels drives spontaneous firing of tuberomammillary neurons. Neuron. 2002;33:587–600. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00574-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vervaeke K, Hu H, Graham LJ, Storm JF. Contrasting effects of the persistent Na+ current on neuronal excitability and spike timing. Neuron. 2006;49:257–270. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vreugdenhil M, Hoogland G, van Veelen CW, Wadman WJ. Persistent sodium current in subicular neurons isolated from patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:2769–2778. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JA, Klink R, Alonso A, Kay AR. Noise from voltage-gated ion channels may influence neuronal dynamics in the entorhinal cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:262–269. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.1.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickens JR, Wilson CJ. Regulation of action-potential firing in spiny neurons of the rat neostriatum in vivo. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:2358–2364. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.5.2358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilent WB, Contreras D. Stimulus-dependent changes in spike threshold enhance feature selectivity in rat barrel cortex neurons. J Neurosci. 2005a;25:2983–2991. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4906-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilent WB, Contreras D. Dynamics of excitation and inhibition underlying stimulus selectivity in rat somatosensory cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2005b;8:1364–1370. doi: 10.1038/nn1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SR, Stuart GJ. Mechanisms and consequences of action potential burst firing in rat neocortical pyramidal neurons. J Physiol. 1999;521(Pt 2):467–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00467.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu N, Enomoto A, Tanaka S, Hsiao CF, Nykamp DQ, Izhikevich E, Chandler SH. Persistent sodium currents in mesencephalic v neurons participate in burst generation and control of membrane excitability. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93:2710–2722. doi: 10.1152/jn.00636.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue C, Remy S, Su H, Beck H, Yaari Y. Proximal persistent Na+ channels drive spike after depolarizations and associated bursting in adult CA1 pyramidal cells. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9704–9720. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1621-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]