Abstract

The small heat shock proteins (sHSPs) and the related α-crystallins (αCs) are virtually ubiquitous proteins that are strongly induced by a variety of stresses, but that also function constitutively in multiple cell types in many organisms. Extensive research demonstrates that a majority of sHSPs and αCs can act as ATP-independent molecular chaperones by binding denaturing proteins and thereby protecting cells from damage due to irreversible protein aggregation. Because of their diverse evolutionary history, their connection to inherited human diseases, and their novel protein dynamics, sHSPs and αCs are of significant interest to many areas of biology and biochemistry. However, it is increasingly clear that no single model is sufficient to describe the structure, function or mechanism of action of sHSPs and αCs. In this review, we discuss recent data that provide insight into of the variety of structures of these proteins, their dynamic behavior, how they recognize substrates, and their many possible cellular roles.

sHSPs and protein quality control

Protein aggregation resulting from stress, disease or mutation poses a major threat to all organisms [1]. At the cellular level, damage due to protein aggregation is limited and repaired by a “protein quality control” network consisting of molecular chaperones and proteases [2]. Molecular chaperones are structurally diverse proteins, including the well known Hsp90, Hsp70 and GroE proteins, which share the ability to recognize and bind other proteins in non-native states [2, 3]. Chaperones thereby facilitate a wide range of processes that promote efficient protein folding, as well as prevent or reverse protein aggregation. Proteins that cannot be repaired are subject to proteolysis, and chaperones can also participate in delivering substrates to cellular proteases. The widespread small heat shock proteins (sHSPs), first discovered due to their strong induction at high temperatures in many organisms, and the related α-crystallins (αCs) of the vertebrate eye lens were initially characterized as chaperones almost 20 years ago [4, 5]. Many sHSPs and αCs (hereafter collectively named sHSP/αCs) have subsequently been shown to act in an ATP-independent fashion to bind up to an equal weight of non-native protein to limit aggregation and to facilitate subsequent refolding by ATP-dependent chaperones [6, 7]. Thus, sHSP/αCs are considered important components of the protein quality control network. Subsequently, multiple inherited human diseases have been discovered to result from defects in sHSP/αCs, and these proteins accumulate in neurodegenerative disorders and other diseases linked to aberrant protein folding [8]. Here, we review recent advances in understanding the structure and chaperone activity of sHSP/αC proteins and point out that chaperone activity alone may not explain the function of all members in this diverse protein family [6, 7, 9].

The α-crystallin domain and sHSP/αC diversity

The defining feature of sHSP/αC proteins, whose monomers range in size from ~12 to 42 kDa, is a C-terminally located domain of ~90 amino acids, known as the α-crystallin domain (ACD; PROSITE profile PS01031). This signature ACD is flanked by an N-terminal arm of divergent sequence and variable length (average 55 amino acids) and a C-terminal extension (typically <20 residues) [10, 11]. Atomic structures (Table 1) reveal that the ACD comprises seven or eight anti-parallel β-strands that form a β-sandwich, consistent with earlier circular dichroism data showing predominance of β-structure. Despite low sequence identity, the ACD β-sandwich is the evolutionarily conserved hallmark of the sHSP/αC family [10, 11] (Fig. 1a). Sequence identities in the N-terminal arm are found only between closely related species, and conservation in the C-terminal extension is limited to an I/L-X-I/L motif. Thus, unlike other families of heat shock proteins such as the Hsp70 and Hsp90 chaperone families, sHSP/αCs show extensive sequence variation and evolutionary divergence.

Table 1.

Structural data for sHSP/αC proteins.

| High resolution data | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | Origin | aa | PDB | Residues in structure |

Resolution (Å) |

Subunits in oligomer a |

Ref. |

| Hsp16.5 | Methanocaldococcus jannaschii | 147 | 1SHS | 33–147 | 2.9 | 24 (24) | [17] |

| Hsp16.9 | Wheat (Triticum aestivum) | 151 | 1GME | 2 (43 b)–151 | 2.7 | 12 (12) | [18] |

| Tsp36 | Tapeworm (Taenia saginata) | 314 | 2BOL | 2–314 | 2.5 | 2 (2) | [32] |

| HspA | Xanthomonas citri pv. citri | 158 | 3GLA | 40–139 | 1.65 | 2 (12) | [85] |

| 3GT6 | 39/40–138/139 | 2.15 | 2 (12) | [86] | |||

| 3GUF | 37–139 | 2.28 | 2 (12) | [86] | |||

| Hsp14.0(I120F/I122F) | Sulfolobus tokodaii | 123 | 3AAB | 14–123 | 1.85 | 2 (24?) | [29] |

| HspB1(Hsp27) | Human | 205 | 3Q9P/3Q9Q | 90–171 | 2.0/2.2 | 6 (<24–32) c | [89] |

| HspB5 (αB-crystallin) | Human | 175 | 2WJ7 | 67–157 | 2.63 | 2 (<24–32) | [25] |

| 3L1G | 68–162 | 3.32 | 2 (<24–32) | [27] | |||

| 2KLR | 69–150 | 1.53 | 2 (<24–32) d | [21] | |||

| HspB5 (αB-crystallin) R120G/L137M | Human | 175 | 2Y1Z | 67–157 | 2.5 | 2(24–32) | [28] |

| HspB4 (αA-crystallin) with zinc | Bovine | 173 | 3L1E | 59–163 | 1.15 | 2 (24–32) | [27] |

| HspB4 (αA-crystallin) | Bovine | 173 | 3L1F | 62–163 | 1.53 | 2 (24–32) | [27] |

| HspB6(Hsp20) | Rat | 162 | 2WJ5 | 65–162 | 1.12 | 2 (2) | [25] |

| HspB4 (αA-crystallin) | Zebrafish | 173 | 3N3E | 61–166 | 1.75 | 2 (24–32) | [87] |

| EM data | |||||||

| Protein | Origin | aa | PDB | EM file |

Resolution (Å) |

Subunits in oligomer |

Ref. |

| ACR1 (Hsp16.3) | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 144 | 2BYU e | 1149 | 16.5 | 12 (12) | [88] |

| Hsp26 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 214 | 2H50 e | 1221 | 10.8 | 24 (24–32) | [31] |

| 2H53 e | 1126 | 11.5 | 24 (24–32) | [31] | |||

| HspB5 (αB-crystallin) | Human | 175 | n.a. | 1121 | 20 | 24 (24–32) | [23] |

The oligomeric state in the determined structure is listed first, with the native oligomeric state indicated in parentheses.

To be defined by author.

Crystal packing resulted in a hexamer that is non-native.

2KLR is a dimer that was determined in the context of the oligomer by solid state NMR; a model for a 24-mer is also presented in Ref. x [To be defined by author].

Coordinates in these files are for the wheat Hsp16.9 ACD domain fitted into the determined EM density.

Abbreviations: n.a., not available.

Figure 1.

Amino acid sequence features and evolutionary relationships of sHSP/αCs. (a) Amino acid sequence alignment of sHSP/αCs for which structural data are available (Table 1). Residues comprising β-strands are in cyan background (note that the extent of B7 differs in different published structures). The ACD comprises β2 through β9 (red line). Note that the vertebrate proteins lack β6, but have an extended β7. The conserved I/L-X-I/L motif in the C-terminal extension is boxed. Phosphorylation sites in vertebrate proteins are highlighted in yellow. Sites of mutations in human HspB1 and HspB5 are indicated, and human HspB4 mutations are mapped on bovine HspB4 as follows: desmin or myofibrillar-related myopathy (olive), cataract (magenta), cardiomyopathy (red) and motor neuropathy or Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (green) [8, 58]. The first and last residues in the PDB atomic structure file for each protein are underlined and highlighted in gray (Table 1). Abbreviations for organism names: ZFish, zebrafish (Danio rerio); T.a., Triticum aestivum (wheat); S.c., Saccharomyces cerevisiae; X.a., Xanthomonas axonopodis; M.t., Mycobacterium tuberculosis; M.j., Methanocaldococcus janaschii; S.t., Solfolobus tokodaii. Alignment was generated using ClustalW, and then the C-terminal region was adjusted to align the I/L-X-I/L motif for some sequences. (b) Phylogenetic relationships of sHSP/αCs for which structural data are available, along with the complete set of human proteins and conserved land plant paralogs. Only the ACD and C-termianl extension were used for the phylogenetic analysis. Plant lineage is in green and includes multiple orthologous sequences from Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa for those branches (gene families) identified in bold and named by subcellular localization. Thickness of the branch end is indicative of typical numbers of genes in that family. Single named genes in the plant lineage have no identified orthologs to date. The vertebrate lineage with all 10 human proteins is shown in red, selected invertebrate sequences are in orange, and microorganisms in black. Sequences were aligned with Promals3D, a multiple alignment program that uses protein structure to guide amino acid alignments [82]. Alignments were trimmed with Bioedit. The alignment was opened in the program MEGA4 [83] and neighbor-joining trees were constructed using the JTT matrix. Accession numbers: Plant Cytosolic I – Os17.6A,NP_001041951; At17.4I,AF410266_1; Os16.93I, Q943E9; At17.6AI, NP_176195; At17.6BI, NP_180511; At17.6CI,NP_175759; At18.1I,NP_200780; At17.8I, NP_172220;Os16.9I, NP_001041954; Os16.91I, NP_001041953;Os16.92I, NP_001041955; Os17.4AI, NP_001049660;Os17.4BI. NP_001049662; Os17.4DI, NP_001049657; Os17.4CI, NP_001049661;Triticum aestivum, 1GME_A; Plant ER - At22ER, NP_192763; OS22.3ER, NP_001052899. Plant Cytosol IV-At15.IV, NP_193918, Os18.8IV, NP_001059788. Plant Cytosol III – At17.4III, NP_175807; Os17.6BIII, NP_001048317. Plant Cytosol II – At17.6II, NP_196763; At17.7II, NP_196764; Os17.8II, NP_001042231; Os17.6CII< NP_001046302. Plant Peroxisome - At15.7PX, NP_198583, Os17.6PX, NP_001057300. Plant Cytosol IV – At15.4IV, NP_193918, Os18.8IIV, NP_001059788. Plant Mitochondria 2 – At26.5, NP_001117476, Os21.2, B7EZJ7. Plant Chloroplast – At25.6Cp, NP_1944497, Os26.oCp, NP_0001049541, Plant Mitochondria 1 – At23.6MI, NP_194250; At23.5MI, NP_199957; Os22MI, NP_0001048175, Os22.4MI, NP_001057162. Other plant proteins without identified orthologs – Os18, NP_001052899; Os18.2, NP_001045766; Os16.9C, Q0DY72; At14.2, NP_199571. Microbial proteins – Methanocaldococcus jannaschii, NP_247258; Synechocystis sp. 6803, NP_440316.1; Xanthomonas axonopodis, 3GT6_A; E. coli IbpA, ZP_04001711; E. coli IbpB, YP_543196; Saccharomyces cerevisiae Hsp26, CAA85016.1. Invertebrate proteins – Caenorhabditis elegans Hsp16, AAA28066.1; Drosophila melanogaster Hsp26, ABX80642.1; Hsp22, NP_001027114; Hsp23, NP_523999; Hsp27, NP_524000; Vertebrate proteins – Homo sapiens HspB1, AAA62175; HspB2, Q16082.2; HspB3, Q12988.2; HspB4, P02489.2; HspB5, P02511; HspB6, )14558; HspB7, Q9UBY9; HspB8, NP_055180.1HspB9, Q9BQS6.1;HspB10, Q14990.2; Danio rerio, 3N3E_A.

Genome sequence data continue to expand our understanding of the heterogeneity of sHSPs/αCs [10–12]. The phylogram in Fig. 1b displays the evolutionary relationship of this protein family, emphasizing the independent evolution of sHSP/αCs in major groups of organisms. Humans have 10 paralogous (see Glossary) sHSPs, designated HspB1 to HspB10, where HspB4 is αA-crystallin and HspB5 is αB-crystallin [13, 14]. Orthologs of all ten human sHSPs can be identified in other mammals, but only distinct subsets are found in other vertebrates, and different vertebrates have unique paralogs. There are 11 sHSP families with orthologs throughout land plants, each with different numbers of paralogs depending on the plant species [12, 15]. Five plant families encode proteins targeted to the cytosol, whereas others localize to the nucleus, chloroplasts, mitochondria, ER and peroxisomes. Organelle-targeted sHSPs are unique to plants, with the exception of a mitochondrial-targeted sHSP in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster [16]. At least two of the cytosolic families and the chloroplast-targeted form have orthologs in mosses, indicating that these sHSPs arose over 400 million years ago. Specific plant species also have sHSPs outside of these 11 families, suggesting recent sHSP evolution in the plant kingdom, as is also apparent in metazoans. The absence of orthologous proteins among major groups of organisms, and the recent evolution of new forms indicate it is unlikely that a single model can explain sHSP/αC functions.

There are also considerable differences in the tissue localization and expression levels of sHSP/αCs. Although many are induced by heat stress, some sHSP/αCs are constitutive components of specific tissues in many different organisms. HspB4 and HspB5 make up over 50% of vertebrate lens protein, and HspB1, HspB2, HspB3, HspB5, HspB6, HspB7 and HspB8 are present at significant levels in many muscle tissues [8, 13]. Moreover, sHSP/αCs are developmentally regulated and found in reproductive and embryonic tissues in animals and plants [6]. In addition, they accumulate during stationary phase in many microorganisms and in dormant or quiescent states of numerous invertebrates. Overall, this family of chaperones participates in multiple processes in both normal and stressed cells.

Variations on a common structural theme produce different oligomeric architectures

Although sHSP/αC monomers are relatively small, the majority of these proteins exist as oligomers of between 12 to >48 subunits in their native state. The first solved structures of sHSP/αC oligomers were those of the 24-subunit Hsp16.5 from the archaeon Methanocaldococcus jannaschii (formerly classified within the genus Methanococcus) [17] and the eukaryotic dodecameric Hsp16.9 from Triticum aestivum (wheat) [18]. These structures defined the architecture of the ACD, identified a dimeric substructure, and clarified the contacts required for oligomerization. Recently, additional structures of primarily the ACD have been determined from bacteria and metazoans, including human HspB5 (Table 1). Obtaining high resolution data for oligomeric forms of the metazoan proteins has been challenging because of the well-documented polydispersity of the oligomers [19, 20]. However, models for human HspB5 have been developed by combining information from multiple structural techniques, providing a more complete picture of how these oligomers may be organized [21–24].

The sHSP/αC structural data present a fascinating picture of how the conserved ACD is adapted to multiple architectures. In all sHSP/αC oligomers, a dimer is the basic building block, but two very different dimer interfaces are possible, dependent on the presence or absence of a loop that contains a β-strand known as β6 (Figs. 1a and 2a). Proteins containing the β6 loop (such as Methanocaldococcus Hsp16.5, wheat Hsp16.9, Xanthomonas HspA and Sulfolobus Hsp14.0) form dimers through strand swapping, in which β6 of one monomer is incorporated into the edge of a β-sheet comprising strands 2, 3, 9 and 8 of the other monomer. Dimers of this type are predicted for most bacterial, yeast and plant sHSP/αCs. In contrast, a very different dimer structure is apparent in the metazoan proteins HspB4, HspB5 and HspB6 (also known as Hsp20), as illustrated for human HspB5 in Fig. 2a. In the absence of β6, β7 is elongated and forms the dimer interface in antiparallel orientation with β7 of the other monomer (referred to as the AP interface), creating a continuous β-sheet of strands 4, 5 and 7 with strands 7, 5 and 4 [25, 26]. There are differences in the length of β7 in the reported metazoan structures and in how the AP interface forms with regard to registration of hydrogen bonding between the β7 strands [20, 26]. Whether these variations in the AP interface exist in solution or contribute to the polydispersity of metazoan sHSP/αCs is under debate [25, 27–29].

Figure 2.

Different sHSP/αCs have different dimer structures but share a conserved contact for oligomer formation. (a) Dimer structure of wheat Hsp16.9 (1GME; left) and human HspB5 (2KLR; right). Individual monomers are colored red or blue. Regions outside the ACD in wheat Hsp16.9 are in gray, including the N-terminal arm of one monomer and the C-termini of both monomers; note that the HspB5 structure comprises only the ACD without β2. Differences in the dimer structures are discussed in the text. 2KLR is an NMR structure and represents only one of several structures available for related vertebrate proteins (Table 1). Although all the vertebrate structures show the same dimerization mode mediated by β7, details of the different vertebrate structures vary [28]. The most highly conserved residues (Fig. 1a) show different positions in the two dimer forms as highlighted for the conserved arginine in β7 (green stick) and the conserved G-X-L (green cartoon). (b) The conserved C-terminal I/V-X-I/V motif connects dimers in sHSP/αC oligomers by interacting with a hydrophobic groove formed by β4 and β8 at one edge of the ACD β-sandwich of another monomer. The model shown is derived from the wheat Hsp16.9 structure, but the same contact is observed in the Methanocaldococcus structure [17] and is proposed from recent NMR and X-ray data for vertebrate sHSP/αCs [21, 27, 30].

Several features determine the assembly of sHSP/αC dimers into a variety of oligomeric structures. First, the C-terminal I/L-X-I/L motif, found in over 90% of sHSP/αC sequences [10], patches a hydrophobic groove formed by β4 and β8 on one edge of the ACD β-sandwich (Fig. 2b). This contact is well-defined in the Methanocaldococcus Hsp16.5 and wheat Hsp16.9 structures and is essential for integrity of the oligomer as shown by mutagenesis. Because the I/L-X-I/L motif is within the flexible C-terminal extension, dimers can be connected in different geometries, making possible the variety of structures observed for the monodisperse oligomers of Methanocaldococcus Hsp16.5, wheat Hsp16.9 and Mycobacterium Hsp16.3 as shown in Fig. 3. The same variation in connections between dimers has been observed in NMR and crystal structures of the 24-mer and higher order oligomers of the polydisperse human HspB5, which is comprised of β7 dimers [22, 24, 26, 27, 30]. However, under physiological conditions, some contacts distal to the I/L-X-I/L motif may be more important for assembly of these oligomers. The role of the C-terminus in dimer interactions remains poorly understood in the cryo-EM, 24-mer structure of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Hsp26 (Fig. 3) [31]. Perhaps the extended length of the N-terminal arm in this protein (Fig. 1a) allows other ways of oligomeric assembly.

Figure 3.

Diversity of sHSP oligomer architecture. sHSP oligomeric structures derived from X-ray and EM data (Table 1). Surface representations are shown in two orientations rotated by 90°. Ribbon diagrams of a single dimer structure are superimposed, although the wheat dimer (Hsp16.9) was used for the dimer structures of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and yeast. Bottom row shows geometric diagrams to illustrate the molecular symmetry of the molecules, with each solid line representing location of one dimer.

C-terminal contacts alone are not sufficient to define or to maintain the oligomer geometry of sHSP/αCs. For most sHSP/αCs, deletion of all or part of the N-terminal arm disrupts the oligomers, sometimes resulting in stable dimers, but often leading to aggregation. Amino acid changes in the N-terminal arm can also alter oligomer organization, frequently leading to high molecular weight aggregates. The structure and organization of the N-terminal arm, however, is not well defined. Of the available X-ray structures, only the wheat Hsp16.9 dodecamer structure includes density for the full length N-terminal arm, and only six of the 12 N-terminal arms were resolved (Fig. 2a). These N-terminal arms have three helical segments and form pairwise interactions between dimers, linking dimers that are different from those linked by the C-termini. The N-terminal arm also makes an intramolecular contact with hydrophobic residues on the β2-β7 edge of the ACD. The flexibility of the N-terminal arm is exemplified by the disorder of six N-terminal arms of wheat Hsp16.9, the disorder of all of the N-terminal arms of the Methanocaldococcus Hsp16.5, and the inability to obtain structural information from the N-termini of other sHSP/αCs. These disordered N-termini probably fill the apparent central cavity of sHSP/αC oligomers, although how they are positioned remains uncertain. Recent NMR data of HspB5 oligomers [22] have provided distance constraints on N-terminal residues, leading to a model with two α-helical segments and a β-strand preceding the ACD domain. The heterogeneity of the NMR signals, however, indicates that the structures are dynamic. Taken together, the structural data indicate that the N-terminal arm is a flexible and, possibly, intrinsically disordered domain that affects the organization and stability of the sHSP/αC oligomers.

Structural data are also available for an unusual member of the sHSP/αC family, Tsp36 from a parasitic flatworm (Table 1) [32], as well as for members of a structural superfamily that includes Hsp90 cochaperone p23 [33]. Tsp36 has two ACDs, and forms a dimer under reducing conditions and a tetramer under oxidizing conditions [32]. Neither the orientation of the two ACDs within a monomer nor between monomers involves interfaces similar to those observed for the wheat or metazoan sHSP/αCs; this indicates that there are further possibilities for assembling ACDs into higher order structures, dependent on variation of flanking domains. In addition, the Hsp90 co-chaperone p23, which is essentially a monomeric ACD with a flexible C-terminal extension [18], exhibits ATP-independent chaperone activity in binding denaturing proteins.

sHSP/αC proteins are highly dynamic

Defining sHSP structure and function is significant not only because these proteins are linked to protein quality control in normal and diseased cells, but also because they illustrate the importance of protein dynamics in protein function. The sHSP/αC proteins are dynamic at the secondary, tertiary and quaternary levels of protein organization. Dynamic exchange of subunits between α-crystallin oligomers (Fig. 4) was reported over 20 years ago [6] and has now been examined for several sHSP/αCs using FRET and, more recently, mass spectrometry approaches [6, 20, 30, 34, 35]. Rapid subunit exchange is not limited to the polydisperse metazoan proteins, but also occurs between the well-defined monodisperse oligomers, such as wheat Hsp16.9. For all sHSP/αCs that have been examined, the rate-limiting step in subunit exchange seems to be the dissociation of subunits from the oligomers. Subunit association is very rapid, such that significant populations of suboligomeric species are not detected, except at elevated temperatures in some cases. Reported rate constants for exchange range from 0.038 to 0.089 min−1 for different vertebrate sHSP/αCs, and are significantly faster for plant sHSP/αCs at 0.16 to 0.40 min−1 depending on temperature. This is notably faster than a majority of other proteins for which similar measurements have been made, including tetrameric transthyretin (4.5 X 10−4 min−1) [36] or hepatitis B capsid protein (>90 days) [37]. Not surprisingly, subunit exchange increases with temperature, and is highly sensitive to changes in ionic and other conditions, which could tune the exchange rate in vivo, making suboligomeric forms available for substrate binding.

Figure 4.

A model for the chaperone mechanism of sHSP/αC proteins. (i) sHSP/αC oligomers (here wheat Hsp16.9, 1GME) are dynamic structures that continually release and reassociate with their constituent subunits, either dimers (shown here) or monomers. (ii) Damaged or denaturing proteins (here malate dehydrogenase, 1MLD) expose hydrophobic surfaces prone to aggregation. (iii) The unfolding substrate binds to the sHSP to form large sHSP-substrate complexes with variable stoichiometries. Note that the form of the sHSP responsible for capturing denaturing substrate remains undefined and may be either oligomeric or a smaller species (such as the dimer). (iv) sHSP-substrate complexes can be acted on by Hsp70, co-chaperones and ATP, resulting in refolded active substrate. (v) In the absence of sufficient sHSP to capture denaturing substrate, protein aggregates are formed that are difficult for the cell to remove. (vi) sHSP-substrate complexes may also be acted on by cellular proteases, although this pathway is less well investigated than the refolding pathway. The specificities of different sHSP/αCs for different substrate proteins, as well as how different sHSP/αCs function together in one cell, remain to be defined. This model for chaperone activity may not explain all the different cellular roles of the sHSP/αCs.

As determined by a combination of NMR and mass spectrometry [30], the rate of subunit exchange in HspB5 can be explained by the microscopic rate constant of detachment of the C-terminal extension. This motion occurs on the order of milliseconds, but two events must coincide to allow detachment of subunits, leading to the longer timescale of subunit exchange. “Microscopic” flexibility of contacts within the sHSP oligomer is also seen for the N-terminal arms as documented by hydrogen-deuterium exchange coupled with mass spectrometry [38]. This lack of stable secondary structure for the N-terminal arm in solution is consistent with the inability to resolve N-terminal arms in high-resolution structural studies. Linking these various dynamics to sHSP/αC function remains a challenge.

Chaperone activity of sHSP/αC proteins

In 1992, Horwitz demonstrated that α-crystallins can suppress protein aggregation in an ATP-independent fashion [4]. Since then, many sHSP/αC proteins have been shown to bind up to an equal weight of non-native protein, keeping it accessible to other ATP-dependent components of the protein quality control network for further processing [6, 7, 9]. This activity places them in the position of “first responders” to cell stress, capable of immediately binding unfolding proteins. Understanding in detail how sHSPs accomplish this feat is crucial to defining their roles in protection of cells from stress and disease. In contrast to our extensive knowledge of the structure and function of other chaperones such as Hsp100, Hsp70 and GroEL [39, 40], the mechanism of sHSP function has received much less attention.

The most common assays of sHSP/αC activity in substrate protection (Fig. 5) involve subjecting substrate proteins to denaturation by heat or reduction of disulfide bonds, and then measuring how sHSP/αCs prevent the formation of light-scattering aggregates (Fig. 5a) or maintain proteins in solution as determined by centrifugation (Fig. 5b). The ratio of substrate to sHSP/αC required for complete suppression of substrate aggregation is a measure of chaperone efficiency, and varies between substrates as well as for different sHSP/αCs. Typically, sHSP/αCs are less efficient with larger proteins, i.e. protection depends on the mass ratio, rather than the molar ratio, of sHSP/αC to substrate. This no doubt reflects the need for physical interaction of the sHSP/αC with the unfolding substrate and for exposure of sufficient charged or hydrophilic surface to maintain aggregates in solution. sHSP/αCs cannot rescue already aggregated proteins, nor do they interact with native substrate proteins. Rather, their action depends on capturing denaturing proteins before they form irreversible aggregates.

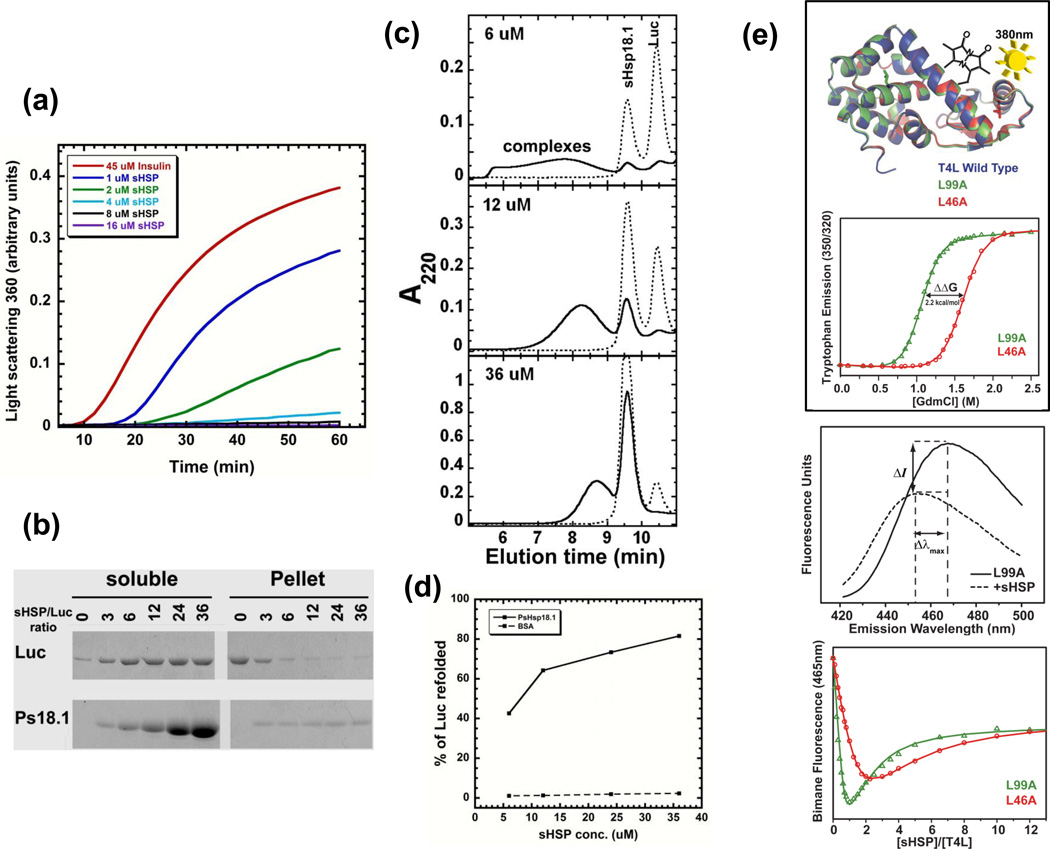

Figure 5.

In vitro assays for the study of the ATP-independent chaperone activity of sHSP/αCs. (a) Light scattering assay of suppression of aggregation. Relative light scattering measured at 360 nm can be used to monitor the aggregation of substrate proteins during denaturation induced by heat or by reduction. Scattering is suppressed with increasing amounts of chaperone. This is a rapid and simple assay. As shown here for reduction of insulin, maximal scattering (aggregation) is observed in the absence of the sHSP/αC. With increasing amounts of chaperone (here pea Hsp18.1), scattering is suppressed. The sHSP prevents insulin aggregation very efficiently at the molar ratio of 4 uM sHSP monomer to 45 uM insulin monomer, equivalent to a weight to weight ratio of 1:1. (b) Protection of solubility. A heat sensitive substrate (e.g. firefly luciferase, or Luc) is heated in the presence of a sHSP/αC (here pea Hsp18.1, or Ps18.1), then cooled and centrifuged. Soluble and pellet fractions are separated by SDS-PAGE and stained for protein. The protection efficiency can be estimated by varying the ratio of sHSP and substrate. In the absence of sHSP, all of the luciferase is in the pellet fraction, whereas in the presence of 3–6 µM sHSP monomers all the luciferase is found in the soluble fraction, representing protection of approximately an equal mass of substrate. (c) Visualizing sHSP-substrate complexes. Samples of sHSP plus substrate as shown in (b) can be separated by size exclusion chromatography to visualize sHSP-substrate interaction. Before heating, the substrate protein (Luc) and the sHSP elute separately at the expected position for their native molecular weight (dotted line). After heating (solid line), free substrate is no longer present, and the soluble sHSP-substrate complexes elute earlier than the free sHSP or substrate in the form of larger, heterogeneous mixtures. The complex size distribution changes with increasing ratio of sHSP to substrate, as shown by the differences in timing of elution of the complex peak in the different panels. Assays in (a–c) are non-equilibrium, end-point assays due to the essentially irreversible nature of complex formation. (d) A substrate refolding assay is used to examine how effective an sHsp/αC is in maintaining an enzymatic substrate in a conformation that can be refolded by ATP-dependent chaperones (such as Hsp70). Soluble complexes as in (b) are diluted into reticulocyte lysate (a rich source of ATP-dependent chaperones) plus ATP, or into a mixture of purified Hsp70/DnaK, co-chaperones and ATP, and then monitored for restoration of enzyme activity. Here, the endpoint of luciferase reactivation after one hour was plotted for different sHSP-luciferase ratios. Although luciferase is protected from aggregation at all ratios as in (b), it is obvious that different complexes facilitate a different extent of reactivation as in (c), which is consistent with differences in the size or organization of these complexes that may alter accessibility of substrate to the refolding machinery. (e) Equilibrium assay for binding of substrate to sHSP. Here, the binding of sHSP to thermodynamically destabilized variants of T4 lysozyme (T4L) is shown. Top: Characteristics of destabilized T4L mutants used as substrates. Although the T4L mutations do not change the structure of the native state (as demonstrated by superposition of mutant and wild-type T4L structures), they increase the free energy of unfolding as monitored by determining the midpoint value of guanidine-HCl concentration required to unfold the mutants. Thus, at equilibrium, a higher fraction of some T4L variants (eg. L99A) is in the unfolded state compared to other variants (e.g. L46A or the wild type). Using a bimane fluorescence label introduced at residue 151 of T4L, it is possible to monitor the binding of T4L to a HSP (here HspB5). Middle: The intensity and/or change in maximum intensity wavelength of fluorescence is used to monitor formation of a stable complex between T4L and sHSP. Bottom: Titration with increasing sHSP concentrations yields binding isotherms that can be fit to obtain apparent binding affinities and number of binding sites [7].

sHSP-substrate complexes can be observed by size exclusion chromatography (Fig. 5c). They are large and heterogeneous, and their size distribution depends on the ratio of sHSP/αC to substrate as well as the rate of substrate aggregation, which is affected by concentration and temperature. Essentially, the denaturing substrate is prevented from aggregating with itself by instead binding the sHSP/αC, and the rate of the “competing reactions” of substrate self-aggregation vs binding to the sHSP (also described as “kinetic partitioning”) will determine the efficiency of substrate protection. Complexes get smaller as the ratio of sHSP/αC to substrate increases (Fig. 5c), which is consistent with the chaperone preventing more self-aggregation of substrate and affording better solubility [35]. A detailed analysis of complexes formed between pea Hsp18.1 and firefly luciferase by high resolution mass spectrometry, under conditions that maintain non-covalent complexes, have revealed a dramatic reorganization of the native dodecameric oligomer, with complexes comprising 14–36 sHSP monomers and an overlapping distribution of 1–3 luciferase molecules with increasing sHSP concentrations [35]. The accessibility of the sHSP-bound substrate is reflected in its susceptibility to proteolysis as well as the ability of the ATP-dependent chaperones Hsp70 or DnaK to release and restore the protein substrate to an enzymatically active state (Fig. 5d). Substrate reactivation is also affected by the sHSP-substrate ratio, with smaller sHSP-substrate complexes showing higher reactivation yield (Fig. 5d).

McHaourab and colleagues [7] have used a library of fluorescently labeled T4 lysozyme variants with differences in thermodynamic stability to make equilibrium measurements of sHSP-substrate interactions (Fig. 5e). They showed that more-destabilized T4 lysozyme mutants (those with lower folding equilibrium constants) bind sHSPs with higher affinity. This assay provides an excellent demonstration of the ability of sHSPs to capture unfolded states of proteins, even when these states are present for only a small fraction of the time, which may reflect the in vivo action of sHSPs/αCs that are present constitutively in many tissues. In essence, they are acting as “sensors” that detect unstable proteins even in the absence of stress.

Recognizing substrates

It is unclear how sHSP/αCs recognize non-native substrates and to what extent they may show substrate specificity. It is generally agreed that substrate binding is facilitated by an increase in available hydrophobic surface on the sHSP/αC, which seems to occur without significant loss of defined sHSP secondary and tertiary structure [6, 7, 9]. Exactly how this occurs, however, is a matter of debate. Some sHSPs dissociate to form stable dimers at the temperatures used for substrate denaturation, while others do not [41]. The proposal that a dimeric or other suboligomeric form binds substrate is appealing; the oligomeric form would act as a “storage form” that sequesters hydrophobic surfaces until needed. In addition, some sHSP/αCs, such as HspB6, purify as dimers and show high chaperone activity [42]. Oligomeric sHSP/αCs that do not dissociate to form stable suboligomeric forms could still expose surfaces during subunit exchange, with substrate interaction shifting the equilibrium to suboligomeric forms [7, 43]. There is no consensus, however, that subunit exchange rates correlate with chaperone activity [7, 30]. Defining the active substrate binding form is further complicated for vertebrate sHSP/αCs which are phosphorylated (Fig. 1) by specific kinase cascades. Phosphorylation alters their oligomeric state, and clearly plays an unresolved role in controlling activity [44, 45].

Although sHSP/αC-substrate interactions may involve exposure of hydrophobic surfaces, the identity of the specific interaction sites and the degree of substrate unfolding required for recognition are still active areas of investigation. Several lines of evidence indicate that substrates are recognized in an early unfolding state, well before loss of core structure [7, 38]. Limiting substrate unfolding would improve the efficiency of subsequent refolding by the ATP-dependent chaperones. Substrate-binding sites on sHSP/αC proteins have been probed by the analysis of deletion mutants as well as by more direct crosslinking methods or binding to peptide libraries [46, 47]. The emergent picture is that there is no single, specific substrate binding surface on sHSP/αCs. It rather appears that many sites contribute to substrate interactions, and binding is probably different for different substrates dependent on the conformation of surfaces exposed when a substrate unfolds. A recent study incorporated the amino acid analog benzoylphenylalanine at multiple sites in pea Hsp18.1 to test the efficiency of photocrosslinking of the sHSP to the substrate in heat-formed complexes with luciferase or malate dehydrogenase. The highest crosslinking efficiency was observed to N-terminal arm sites, implicating this flexible and evolutionarily variable region in substrate recognition [48]. This result is consistent with other experiments implicating the N-terminal arm as a major, though not exclusive, player in substrate recognition [7, 46]. Overall, it seems that sHSP/αCs have a very flexible mode of substrate recognition, which when understood may afford insights into how to limit damage due to protein misfolding.

It is, however, crucial to note that although many sHSP/αC proteins have been tested and found to function as chaperones in one or more of the assays described here, there are exceptions. The E. coli proteins IbpA and IbpB show different substrate protection abilities. IbpA alone has little activity, but it enhances the activity of IbpB [49]. In addition, not all mammalian sHSP/αCs show robust ability to prevent aggregation of other proteins, and different sHSP/αCs can have vastly different efficiencies with different substrates [41, 50].

Identification of major in vivo substrates of sHSP/αCs is an area of research that needs to be further pursued; the vast majority of studies have been performed using model substrates with well-characterized unfolding behavior. It is unclear whether sHSP/αCs have very specific substrates in vivo, or interact with the whole suite of denaturing proteins in any cell. Data from yeast and bacteria suggest a heterogeneous group of potential substrates [51, 52], whereas more specific interactions have been documented for mammalian cells [6, 13]. For example, HspB8 can interact with the Hsp70 co-chaperone Bag3 [53–55], but the essential role of HspB8 in this complex is unclear. Many studies suggest crucial interactions of sHSP/αC proteins with actin and other cytoskeletal components, although quantitative biochemical studies of these interactions are still needed [6, 56].

sHSPs in stress and disease

Several inherited diseases result from sHSP defects [57], and the locations of amino acid changes linked to different diseases are shown in Fig. 1a. HspB4 and HspB5 are required for lens clarity, with defects leading to cataract [58]. In muscle tissues, where sHSP/αCs are abundant, mutations cause cardiac and skeletal myopathies [56, 59–63]. Defects in sHSP/αCs are also linked to inherited neuropathies [64, 65]. Notably, disease-linked mutations result in amino acid changes in all three domains of the protein, the N-terminal arm, the ACD, and the C-terminal extension. The majority of mutations are dominant, with the exception of a few frame-shift and termination mutations. Dominant effects could readily be explained by disruption of sHSP/αC structure leading to aberrant interactions with damaged, or even with native, substrate proteins [65, 66]. Interestingly, one position in the ACD, corresponding to Arg120 in human HspB5, is altered in several disease-linked sHSP/αCs (Fig. 1a). The structure of an HspB5 dimer carrying this mutation suggests that the altered residue disrupts ionic interactions in several sHSP/αCs [28], which might lead to dominant interactions by blocking unidentified essential processes.

In addition, several cancers display a characteristically altered regulation of sHSP expression [67, 68], and sHSPs are associated with protein aggregates in common neurodegenerative disorders that are linked to protein misfolding, such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis [69–71]. Whether the presence of sHSP/αCs in neurodegenerative lesions contributes to the disease or could be manipulated to ameliorate defects is unknown. sHSPs can protect cultured cells from heat, oxidative stress, heavy metals, and ischemic injury [6], but their therapeutic potential has only recently begun to be explored [72, 73]. They have been suggested to have therapeutic potential for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and multiple sclerosis [74], and to positively affect longevity in model organisms [16]. Moreover, they are reported to protect transgenic mice from alcohol stress [75], to suppress aggregation of polyQ proteins [53, 76, 77], and to inhibit amyloid fibril formation [69, 78, 79]. Whether these diverse observations result from the proposed role of sHSP/αCs in the quality control network remains to be defined.

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

In this article, we have emphasized the common features of the sHSP/αC proteins, but at the same time we urge caution attempting to fit all these proteins into a single model of structure and mechanism of action. Clearly, many sHSP/αCs have physical properties that allow them to capture unfolding proteins, a property well worth understanding. In addition, defining how sHSP/αC dynamics control substrate recognition and release should provide new fundamental information about protein-protein interactions. Only with this information will it be possible to harness the aggregation-prevention properties of sHSP/αCs for controlling damage due to stress and disease [80].

Much more work is needed to clarify how sHSP/αCs function in vivo. Available data indicate that some sHSP/αCs recognize almost any unfolding protein, which suggests that they act on any labile or damaged cellular component. However, many sHSP interactions with specific cellular components have also been documented [81], and the existence of tissue-specific and apparently recently evolved proteins, such as mammalian HspB10 (Fig. 1b), suggest that not all sHSP/αCs are “generalists” in the quality control network. Furthermore, the multiplicity of distinct sHSP/αCs operating in the same cellular compartment argues for differentiated functions in either substrate recognition or partner protein interaction. In addition, most efforts have focused on the ability of sHSP/αCs to deliver substrates to the quality control folding machinery (Hsp70/DnaK and co-chaperones), leaving their potential involvement in facilitating substrate degradation by quality control proteases very much underexplored. In total, a picture is emerging that the signature ACD of the sHSP/αCs may be a scaffold on which to attach flexible arms that are capable of preventing irreversible protein aggregation, as well as potentially participating in a variety of other functions requiring protein interactions.

Acknowledgements

E.V. acknowledges the National Institutes of Health (RO1 GM42762), the US Department of Agriculture (2008-35318-04551) and the National Science Foundation (IBN-0213128; DBI - 0829947) for long term support of studies on sHSP biochemistry and function. We thank many collaborators and other lab members for their contributions to results discussed here. We particularly thank Dr. Garrett J. Lee for pioneering sHSP chaperone function in our laboratory. We further thank Dr. Elizabeth Waters and Bharath Bharadwi for preparing the phylogenetic tree in Figure 1b, and Dr. Hassane McHaourab and Sanjay Mishra for Figure 5e. We also thank multiple colleagues for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Glossary

- Bimane

A heterocyclic chemical compound (pyrazolo[1,2-a]pyrazole-1,7-dione) that forms the core of a class of fluorescent dyes known as bimane dyes, which can be covalently attached to proteins in order to monitor changes in protein structure.

- Binding isotherm

Measurement of the fraction of a ligand (the unfolding substrate) bound to a protein (the sHSP) versus the concentration of the ligand. This measurement allows calculation of properties of the binding interaction.

- Co-chaperone

Protein that binds to and assists chaperones in their function.

- Orthologous

Orthologous genes are those for which homology is the result of speciation, such that the history of the gene follows the history of the species. Orthologous genes do not necessarily have identical function.

- Paralogous

Paralogous genes are genes for which homology results from a gene duplication such that the gene copies have evolved side-by-side during the history of the organism.

- Polydispersity

Proteins are considered polydisperse when more than one oligomeric state is present. This is as opposed to “monodisperse” proteins which are found always with the same number of subunits.

- PolyQ proteins

Proteins which contain long repeats of glutamine (Q). Abnormal lengths of polyglutamine repeats (polyQ) in several unrelated proteins are responsible for at least eight inherited neurodegenerative diseases, including Huntington's disease, due to the propensity of these proteins to aggregate.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gidalevitz T, et al. A cellular perspective on conformational disease: the role of genetic background and proteostasis networks. Curr. 0pin. Struct. Biol. 2010;20:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tyedmers J, et al. Cellular strategies for controlling protein aggregation. Nature Rev.Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;11:777–788. doi: 10.1038/nrm2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartl FU, et al. Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis. Nature. 2011;475:324–332. doi: 10.1038/nature10317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horwitz J. Alpha-crystallin can function as a molecular chaperone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:10449–10453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jakob U, et al. Small heat shock proteins are molecular chaperones. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:1517–1520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Montfort R, et al. Structure and function of the small heat shock protein/alpha-crystallin family of molecular chaperones. Adv. Prot. Chem. 2002;59:105–156. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(01)59004-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McHaourab HS, et al. Structure and mechanism of protein stability sensors: chaperone activity of small heat shock proteins. Biochemistry. 2009;48:3828–3837. doi: 10.1021/bi900212j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mymrikov EV, et al. Large potentials of small heat shock proteins. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:1123–1159. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00023.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haslbeck M, et al. Some like it hot: the structure and function of small heat-shock proteins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:842–846. doi: 10.1038/nsmb993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poulain P, et al. Detection and architecture of small heat shock protein monomers. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e9990. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kriehuber T, et al. Independent evolution of the core domain and its flanking sequences in small heat shock proteins. Faseb J. 2010;24:3633–3642. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-156992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waters ER, et al. Comparative analysis of the small heat shock proteins in three angiosperm genomes identifies new subfamilies and reveals diverse evolutionary patterns. Cell Stress Chap. 2008;13:127–142. doi: 10.1007/s12192-008-0023-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vos MJ, et al. Structural and functional diversities between members of the human HSPB, HSPH, HSPA, and DNAJ chaperone families. Biochemistry. 2008;47:7001–7011. doi: 10.1021/bi800639z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kampinga HH, et al. Guidelines for the nomenclature of the human heat shock proteins. Cell Stress Chap. 2009;14:105–111. doi: 10.1007/s12192-008-0068-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siddique M, et al. The plant sHSP superfamily: five new members in Arabidopsis thaliana with unexpected properties. Cell Stress Chap. 2008;13:183–197. doi: 10.1007/s12192-008-0032-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wadhwa R, et al. Proproliferative functions of Drosophila small mitochondrial heat shock protein 22 in human cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:3833–3839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.080424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim KK, et al. Crystal structure of a small heat-shock protein. Nature. 1998;394:595–599. doi: 10.1038/29106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Montfort RL, et al. Crystal structure and assembly of a eukaryotic small heat shock protein. Nature Struct. Biol. 2001;8:1025–1030. doi: 10.1038/nsb722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horwitz J. Alpha crystallin: the quest for a homogeneous quaternary structure. Exp. Eye Res. 2009;88:190–194. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baldwin AJ, et al. αB-Crystallin Polydispersity Is a Consequence of Unbiased Quaternary Dynamics. J. Mol. Biol. 2011;413:297–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jehle S, et al. Solid-state NMR and SAXS studies provide a structural basis for the activation of alphaB-crystallin oligomers. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:1037–1042. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jehle S, et al. N-terminal domain of αB-crystallin provides a conformational switch for multimerization and structural heterogeneity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:6409–6414. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014656108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peschek J, et al. The eye lens chaperone alpha-crystallin forms defined globular assemblies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:13272–13277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902651106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baldwin AJ, et al. The polydispersity of αB-crystallin is rationalised by an inter-converting polyhedral architecture. Structure. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.09.015. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bagneris C, et al. Crystal structures of alpha-crystallin domain dimers of alphaB-crystallin and Hsp20. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;392:1242–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.07.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jehle S, et al. alphaB-crystallin: a hybrid solid-state/solution-state NMR investigation reveals structural aspects of the heterogeneous oligomer. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;385:1481–1497. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laganowsky A, et al. Crystal structures of truncated alphaA and alphaB crystallins reveal structural mechanisms of polydispersity important for eye lens function. Protein Sci. 19:1031–1043. doi: 10.1002/pro.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clark AR, et al. Crystal Structure of R120G Disease mutant of human alphaB-crystallin domain dimer shows closure of a groove. J. Mol. Biol. 2011;408:118–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takeda K, et al. Dimer structure and conformational variability in the N-terminal region of an archaeal small heat shock protein, StHsp14.0. J. Struct. Biol. 2011;174:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baldwin AJ, et al. Quaternary dynamics of αB-crystallin as a direct consequence of localised tertiary fluctuations in the C-terminus. J. Mol. Biol. 2011;413:310–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.White HE, et al. Multiple distinct assemblies reveal conformational flexibility in the small heat shock protein Hsp26. Structure. 2006;14:1197–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stamler R, et al. Wrapping the [alpha]-Crystallin Domain Fold in a Chaperone Assembly. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;353:68–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marchler-Bauer A, et al. CDD: a Conserved Domain Database for the functional annotation of proteins. Nuc. Acids Res. 2011;39:D225–D229. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Painter AJ, et al. Real-time monitoring of protein complexes reveals their quaternary organization and dynamics. Chem. Biol. 2008;15:246–253. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stengel F, et al. Quaternary dynamics and plasticity underlie small heat shock protein chaperone function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:2007–2012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910126107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneider F, et al. Transthyretin slowly exchanges subunits under physiological conditions: A convenient chromatographic method to study subunit exchange in oligomeric proteins. Protein Sci. 2001;10:1606–1613. doi: 10.1110/ps.8901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uetrecht C, et al. Subunit exchange rates in Hepatitis B virus capsids are geometry- and temperature-dependent. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010;12:13368–13371. doi: 10.1039/c0cp00692k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheng G, et al. Insights into small heat shock protein and substrate structure during chaperone action derived from hydrogen/deuterium exchange and mass spectrometry. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:26634–26642. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802946200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doyle SM, Wickner S. Hsp104 and ClpB: protein disaggregating machines. Trends Biochem.Sci. 2009;34:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saibil HR. Chaperone machines in action. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2008;18:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Basha E, et al. Mechanistic differences between two conserved classes of small heat shock proteins found in the plant cytosol. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:11489–11497. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.074088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bukach OV, et al. Some properties of human small heat shock protein Hsp20 (HspB6) Eur. J. Biochem. 2004;271:291–302. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Franzmann TM, et al. Activation of the chaperone hsp26 is controlled by the rearrangement of its thermosensor domain. Mol. Cell. 2008;29:207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ecroyd H, et al. Mimicking phosphorylation of alphaB-crystallin affects its chaperone activity. Biochem.J. 2007;401:129–141. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shashidharamurthy R, et al. Mechanism of chaperone function in small heat shock proteins: dissociation of the HSP27 oligomer is required for recognition and binding of destabilized T4 lysozyme. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:5281–5289. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407236200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahrman E, et al. Chemical cross-linking of the chloroplast localized small heat-shock protein, Hsp21, and the model substrate citrate synthase. Protein Sci. 2007;16:1464–1478. doi: 10.1110/ps.072831607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ghosh JG, et al. Interactions between important regulatory proteins and human alphaB crystallin. Biochemistry. 2007;46:6308–6317. doi: 10.1021/bi700149h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jaya N, et al. Substrate binding site flexibility of the small heat shock protein molecular chaperones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:15604–15609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902177106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ratajczak E, et al. Distinct activities of Escherichia coli small heat shock proteins IbpA and IbpB promote efficient protein disaggregation. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;386:178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Basha E, et al. The N-terminal arm of small heat shock proteins is important for both chaperone activity and substrate specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:39943–39952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607677200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haslbeck M, et al. Hsp42 is the general small heat shock protein in the cytosol of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 2004;23:638–649. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Basha E, et al. The identity of proteins associated with a small heat shock protein during heat stress in vivo indicates that these chaperones protect a wide range of cellular functions. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:7566–7575. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310684200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carra S, et al. Identification of the Drosophila ortholog of HSPB8: implication of HSPB8 loss of function in protein folding diseases. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:37811–37822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.127498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carra S, et al. HspB8 participates in protein quality control by a non-chaperone-like mechanism that requires eIF2{alpha} phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:5523–5532. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807440200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carra S, et al. HspB8 and Bag3: a new chaperone complex targeting misfolded proteins to macroautophagy. Autophagy. 2008;4:237–239. doi: 10.4161/auto.5407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goldfarb LG, et al. Intermediate filament diseases: desminopathy. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2008;642:131–164. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-84847-1_11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Clark JI, Muchowski PJ. Small heat-shock proteins and their potential role in human disease. Curr. Opinion Struct. Biol. 2000;10:52–59. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(99)00048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Graw J. Genetics of crystallins: cataract and beyond. Exp. Eye Res. 2009;88:173–189. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rajasekaran NS, et al. Human alpha B-crystallin mutation causes oxido-reductive stress and protein aggregation cardiomyopathy in mice. Cell. 2007;130:427–439. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Goldfarb LG, Dalakas MC. Tragedy in a heartbeat: malfunctioning desmin causes skeletal and cardiac muscle disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:1806–1813. doi: 10.1172/JCI38027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Willis MS, et al. Build it up-Tear it down: protein quality control in the cardiac sarcomere. Cardiovasc. Res. 2009;81:439–448. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Simon S, et al. Myopathy-associated αB-crystallin mutants: Abnormal phosphorylation, intracellular location and interactions with other small heat shock proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:34276–34287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703267200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tannous P, et al. Autophagy is an adaptive response in desmin-related cardiomyopathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:9745–9750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706802105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dierick I, et al. Small heat shock proteins in inherited peripheral neuropathies. Ann. Med. 2005;37:413–422. doi: 10.1080/07853890500296410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sun X, et al. Abnormal interaction of motor neuropathy-associated mutant HspB8 (Hsp22) forms with the RNA helicase Ddx20 (gemin3) Cell Stress Chap. 2010;15:567–582. doi: 10.1007/s12192-010-0169-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xi JH, et al. Mechanism of small heat shock protein function in vivo: a knock-in mouse model demonstrates that the R49C mutation in alpha A-crystallin enhances protein insolubility and cell death. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:5801–5814. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708704200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kamada M, et al. Hsp27 knockdown using nucleotide-based therapies inhibit tumor growth and enhance chemotherapy in human bladder cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Therapeutics. 2007;6:299–308. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Deng M, et al. The small heat shock protein alphaA-crystallin is expressed in pancreas and acts as a negative regulator of carcinogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1802:621–631. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ecroyd H, Carver JA. Crystallin proteins and amyloid fibrils. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:62–81. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8327-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.van Noort JM, et al. Alphab-crystallin is a target for adaptive immune responses and a trigger of innate responses in preactive multiple sclerosis lesions. J. Neuropath. Exp. Neurol. 2010;69:694–703. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181e4939c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Laskowska E, et al. Small heat shock proteins and protein-misfolding diseases. Curr. Pharm. Biotech. 2010;11:146–157. doi: 10.2174/138920110790909669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kumarapeli AR, et al. Protein quality control in protection against systolic overload cardiomyopathy: the long term role of small heat shock proteins. Amer. J. Transl. Res. 2010;2:390–401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Morrow G, et al. Protection from aging by small chaperones: A trade-off with cancer? Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010;1197:67–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ousman SS, et al. Protective and therapeutic role for alphaB-crystallin in autoimmune demyelination. Nature. 2007;448:474–479. doi: 10.1038/nature05935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Toth ME, et al. Neuroprotective effect of small heat shock protein, Hsp27, after acute and chronic alcohol administration. Cell Stress Chap. 2010;15:807–817. doi: 10.1007/s12192-010-0188-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Robertson AL, et al. Small heat-shock proteins interact with a flanking domain to suppress polyglutamine aggregation. Proc. Natl.Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:10424–10429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914773107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vos MJ, et al. HSPB7 is the most potent polyQ aggregation suppressor within the HSPB family of molecular chaperones. Human Mol. Genet. 2010;19:4677–4693. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Waudby CA, et al. The interaction of alphaB-crystallin with mature alpha-synuclein amyloid fibrils inhibits their elongation. Biophysical J. 2010;98:843–851. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.10.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shammas SL, et al. Binding of the molecular chaperone alphaB-crystallin to Abeta amyloid fibrils inhibits fibril elongation. Biophysical J. 2011;101:1681–1689. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.07.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Balch WE, et al. Adapting proteostasis for disease intervention. Science. 2008;319:916–919. doi: 10.1126/science.1141448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mymrikov EV, et al. Heterooligomeric complexes of human small heat shock proteins. Cell Stress Chap. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s12192-011-0296-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pei J, et al. PROMALS3D: a tool for multiple protein sequence and structure alignments. Nucl. Acids Res. 2008;36:2295–2300. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tamura K, et al. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sobott F, et al. Subunit exchange of multimeric protein complexes. Real-time monitoring of subunit exchange between small heat shock proteins by using electrospray mass spectrometry. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:38921–38929. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206060200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hilario E, et al. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis of XAC1151, a small heat-shock protein from Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri belonging to the alpha-crystallin family. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2006;62:446–448. doi: 10.1107/S174430910601219X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hilario E, et al. Crystal structures of xanthomonas small heat shock protein provide a structural basis for an active molecular chaperone oligomer. J. Mol. Biol. 2011;408:74–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Laganowsky A, Eisenberg D. Non-3D domain swapped crystal structure of truncated zebrafish alphaA crystallin. Protein Sci. 2010;19:1978–1984. doi: 10.1002/pro.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kennaway CK, et al. Dodecameric structure of the small heat shock protein Acr1 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:33419–33425. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504263200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Baranova EV, et al. Three dimensional structure of á-crystallin domain dimers of human heat shock proteins HSPB1 and HSPB6. J. Mol. Biol. 2011;411:110–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]