Abstract

Purpose: From independently conducted free-response receiver operating characteristic (FROC) and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) experiments, to study fixed-reader associations between three estimators: the area under the alternative FROC (AFROC) curve computed from FROC data, the area under the ROC curve computed from FROC highest rating data, and the area under the ROC curve computed from confidence-of-disease ratings.

Methods: Two hundred mammograms, 100 of which were abnormal, were processed by two image-processing algorithms and interpreted by four radiologists under the FROC paradigm. From the FROC data, inferred-ROC data were derived, using the highest rating assumption. Eighteen months afterwards, the images were interpreted by the same radiologists under the conventional ROC paradigm; conventional-ROC data (in contrast to inferred-ROC data) were obtained. FROC and ROC (inferred, conventional) data were analyzed using the nonparametric area-under-the-curve (AUC), (AFROC and ROC curve, respectively). Pearson correlation was used to quantify the degree of association between the modality-specific AUC indices and standard errors were computed using the bootstrap-after-bootstrap method. The magnitude of the correlations was assessed by comparison with computed Obuchowski-Rockette fixed reader correlations.

Results: Average Pearson correlations (with 95% confidence intervals in square brackets) were: Corr(FROC, inferred ROC) = 0.76[0.64, 0.84] > Corr(inferred ROC, conventional ROC) = 0.40[0.18, 0.58] > Corr (FROC, conventional ROC) = 0.32[0.16, 0.46].

Conclusions: Correlation between FROC and inferred-ROC data AUC estimates was high. Correlation between inferred- and conventional-ROC AUC was similar to the correlation between two modalities for a single reader using one estimation method, suggesting that the highest rating assumption might be questionable.

Keywords: AFROC, ROC, AUC estimates correlations

INTRODUCTION

Observer performance studies are widely used to assess medical imaging systems or modalities.1, 2 Radiologists’ interpretation data are acquired for a set of cases (patients) under a specific paradigm and each observer's performance in a modality is summarized in a figure of merit (FoM). Typically, all radiologists interpret a common set of images in all modalities, termed fully crossed multiple-reader multiple-case (MRMC) interpretations.

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) method is a commonly used paradigm to assess the performance of a diagnostic test. For radiology imaging studies, this method requires values of two variables for each case: a truth variable indicating the disease status (diseased/not diseased) for each patient and a decision variable indicating the reader's level of confidence of disease. For typical imaging studies, the observer assigns a single rating to each case representing the observer's subjective confidence that the case is abnormal. When the decision variable is determined in this manner, we refer to the resulting ROC data as conventional-ROC data and the corresponding ROC analysis method as the conventional-ROC method. If the rating exceeds a specified threshold rating, the assignment is classified as a false positive (FP) for a normal case and as a true positive (TP) for a diseased case. The total number of FPs with ratings above a threshold rating ζdivided by the number of normal cases is the false positive fraction FPFζ and TPFζ is defined similarly over abnormal cases. The ROC curve is the plot of TPFζ vs FPFζ as ζ is varied. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) is a widely used estimator in ROC analysis, but other performance measures have been suggested, for example, the partial area under the curve,3 defined as the area to the left of a specified FPF, or the area above a specified TPF.4

While several methods for analyzing MRMC-ROC data exist,5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 the Dorfman-Berbaum-Metz (DBM) method13 is most frequently used and software implementing it is readily available.14 The DBM method has been shown to be equivalent to the Obuchowski-Rockette (OR) method.15, 16 The DBM/OR method accounts for the between- and within-reader correlations that result from readers reading the same cases.13, 15, 16, 17

As noted above, in the conventional ROC method the radiologist provides an overall confidence level that the patient is diseased. The disease could be characterized by an overall change in appearance of an organ (e.g., lung texture) or a collection of localized changes within the organ (e.g., nodules in the lung). In the latter case, the experimenter can choose to collect location-specific ratings using the free-response ROC (FROC) (Refs. 18 and 19) paradigm, where the radiologist indicates the locations of regions (marks) that are suspicious for disease and provides the associated ratings. If a mark is sufficiently close to a true lesion it is classified as lesion-localization (LL) at the assigned rating and otherwise it is classified as nonlesion localization (NL). The total number of NLs with ratings above ζ divided by the total number of images is the nonlesion localization fraction NLFζ and the total number of LLs with ratings above ζdivided by the total number of lesions is the lesion localization fraction LLFζ.

The FROC curve is the plot of LLFζ vs NLFζ as ζ is varied. ROC data can also be derived from FROC data by discarding the location information, under the “highest-rating” assumption;20, 21, 22, 23 i.e., the decision variable for ROC analysis is defined as the rating of the highest rated mark on a case, which we refer to as the inferred-ROC rating. When the decision variable is determined in this manner, we will refer to the resulting ROC data as inferred-ROC data and the corresponding ROC analysis method as the inferred-ROC method. The only difference between the conventional- and inferred-ROC methods is the definition of the decision variable. Either method can be used to estimate an ROC curve and functions of it, such as the AUC.

Letting inferred-FPFζ denote the false positive fraction based on the inferred-ROC ratings, the alternative FROC (AFROC) curve is defined as the plot of LLFζ vs inferred-FPFζ. In the JAFROC (jackknife AFROC) method for analyzing MRMC-FROC data,24 the area under the AFROC curve is chosen as the estimator of performance. JAFROC has undergone extensive simulation validation19, 25, 26, 27 and it is currently the most widely used method for analyzing FROC data.28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45 In common with DBM-MRMC analysis of ROC data, JAFROC uses the DBM/OR analysis of variance method for significance testing.13, 15, 16, 17 Unless otherwise noted, in this paper by FROC analysis we mean JAFROC analysis. Also, it is assumed that each patient (case) provides one image; thus patient, case, and image are synonymous.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the association between the area-under-the-curve (AUC) indices computed using FROC, inferred-ROC and conventional-ROC data in a specific but typical human study. We conducted two separate studies (dual-analysis study) for the task of detecting microcalcifications in digital mammograms by expert radiologists: one study collected FROC data, while the other collected conventional-ROC data.

The following sections report the methods and analyses. A subset of data from a previously conducted free-response observer-performance study was analyzed using JAFROC. Inferred-rating ROC data were obtained from the FROC data and analyzed using DBM-MRMC software. Later the same images were assigned confidence-of-disease ratings by the same radiologists, and the resulting conventional-ROC data were analyzed using DBM-MRMC software. The results of the study and their implications are reported.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

FROC and ROC observer performance studies

The data were a subset of a larger study46 in which 200 cranio-caudal mammograms were processed with five clinical image processing algorithms (Agfa Musica 1, IMS Raffaello Mammo 1.2, Sectra Mamea AB Sigmoid, Siemens OpView v2, Siemens OpView v1). For each image processing, 100 hybrid abnormal images47, 48 were created by superposing 1–3 (average 1.4; 69 images had 1 lesion, 20 images had 2 lesions, and 11 had 3 lesions) simulated clusters of microcalcifications on the raw normal mammograms; the remaining 100 images were the true normal images. The 1000 images (200 × 5) were interpreted under the FROC method by four radiologists, three with more than 15 years’ experience and one resident in his last year. The radiologists marked and rated perceived microcalcifications using a five-point rating scale. Each mark was classified as LL if it was within the smallest rectangle containing the cluster and otherwise it was classified as NL. The figure of merit of interest was the trapezoidal area under the AFROC curve (AFROC AUC) as defined in Eq. (16.7) of Ref. 2; this FoM was computed for each reader and modality using JAFROC software.24 The area under the AFROC curve estimates the probability that a lesion is rated higher than any mark on a normal case. For the JAFROC analysis, the OpView v2 (labeled M1) and OpView v1 (labeled M2) modalities had the largest observed FoM difference.

Inferred-ROC data were obtained from the FROC data for modalities M1 and M2. The multiple mark-rating free-response data on each image were reduced to a single ROC rating by using the highest score of all ratings.19, 20 If the image has no mark the rating is zero; i.e., the case is considered high confidence normal. The figure of merit was the trapezoidal area under the ROC curve (inferred-ROC AUC); this was computed for each reader and modality using DBM-MRMC software.14

Eighteen months after the conclusion of the five-modality FROC study, the images from modalities M1 and M2 were interpreted by the same radiologists and assigned a confidence-of-disease rating using a six-point rating scale. Similar to the inferred-ROC analysis, the figure of merit was the trapezoidal area under the ROC curve (conventional-ROC AUC), which was computed for each reader and modality using DBM-MRMC software14 and is equivalent to the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon statistic. For the inferred- and conventional-ROC analyses, the area under the ROC curve estimates the probability that an abnormal case is rated higher than a normal case with respect to the inferred-ROC and confidence-of-disease rating scales, respectively.

SARA software49 was used to collect the rating information for both FROC and ROC studies. The average time per reader needed to interpret the 400 images (200 × 2 modalities) lasted about 5 h for the FROC study and about 3 h for the ROC study.

Bootstrap estimation of correlation

We used the bootstrap method to determine the nature of the association, across cases (readers were not bootstrapped) between the three AUC estimates. In the first stage of bootstrapping, we generated B = 500 bootstrap samples, each consisting of 100 normal and 100 abnormal mammograms, by separately sampling with replacement from the original 100 normal and 100 abnormal mammograms. The three AUC estimates were computed for each bootstrap sample. Inspection of scatter plots of the bootstrap-sample AUC estimates revealed approximately linear relationships for each of the three pairs of analysis methods, indicating that the Pearson correlation coefficient was appropriate for summarizing association.

For each of the three analysis-method pairs, the Pearson correlation between AUC estimators was computed from the 500 bootstrap pairs of estimates. Standard-error estimates for these three correlation estimates were computed using the bootstrap-after-bootstrap approach;50 specifically, a second stage of bootstrapping was performed that consisted of generating 500 additional bootstrap samples from each of the 500 first-stage bootstrap samples. For each set of 500 second-stage bootstrap samples, areas under the three curves (AFROC, inferred-ROC and conventional-ROC) were computed and the three Pearson correlation estimates were computed across the 500 values. This process yielded 500 Pearson correlation estimates for each method pair; Fisher's transform, discussed below, was applied to each value and an estimate of the standard error of the Fisher-transformed Pearson correlation was computed as the square root of the sample variance of these 500 transformed values.

To ensure that the correlation confidence intervals did not exceed the allowed range of a correlation coefficient (i.e., its magnitude must be less than or equal to unity), calculations were performed on the Fisher transform of the correlations. The Fisher transform and its inverse are defined by

and

respectively, where r is the correlation coefficient. The Fisher transformed correlation is also better approximated by a normal distribution than the untransformed correlation.51 Letting SE denote the estimated standard error of the Fisher-transformed correlation estimate, denoted by f(r), 95% confidence intervals were constructed using the formula f(r) ± 1.96 (SE). The final results were inverse-Fisher transformed to obtain the correlation confidence intervals.

To summarize results, reader-and-modality-specific correlations were averaged and standard errors and 95% confidence intervals were computed based on the average in the same manner as for the individual correlations.

Interpreting the correlations

The bootstrap correlations described in Sec. 2B estimate correlations between the three AUC methods for a fixed reader and specified modality. To interpret the magnitude of these estimates, for each AUC method we also computed the fixed-reader r1, r2, and r3 correlations defined by OR:11 r1 = correlation between different modalities and the same reader; r2 = correlation between different readers using the same modality; and r3 = correlation between different readers using different modalities. The OR correlations that we report for each AUC method are summary correlations outputted by the DBM and JAFROC software earlier described and they are computed, using jackknifing, under the assumption of a common correlation for the four readers. We emphasize that the correlations in Sec. 2B are between outcomes computed using two different AUC methods for a given modality and reader; in contrast, the OR correlations are between outcomes computed using the same AUC method.

Although between-reader variation does not affect either the OR correlations or the correlations described in Sec. 2B, within-reader variability—that describes how a reader interprets the same image on different occasions—does contribute to the variance of the AUC estimates. As a result, with one exception, all of the correlations are attenuated because the variance estimates used for computing them do include within-reader variation; i.e., the correlation would be higher if this source of variability was not present. Specifically, removing the within-reader variability would lower the variance of the AUCs but not affect their covariance, thus resulting in a higher correlation. We refer to the correlation that would have resulted if there had been no within-reader variability as the unattenuated correlation. The one exception is the FROC vs inferred ROC correlation; because inferred-ROC is a deterministic function of FROC data, it can be shown that this correlation is proportionately less attenuated than the other correlations (see the Appendix for details). Thus, we expect this estimated correlation to be less attenuated than for the other two correlations.

In the Appendix, we show that the relationship between the attenuated and unattenuated correlations is given by

| (1) |

For example, if the within-reader correlation was 0.75, then multiplying the attenuated correlation estimates by 1/.75 = 1.33 would yield unattenuated correlation estimates. Hence estimating the unattenuated correlations for the FROC and inferred-ROC vs ROC data requires knowledge of the within-reader correlation, which necessitates repeated readings for its estimation, but this information was not available from our data. Furthermore, we were not able to find in the literature the within-reader correlation (or the needed information for computing it) from other mammography studies. Fortunately, the r1, r2, and r3 correlations similarly do not account for within-reader variability, and hence they are valid for providing perspective regarding the magnitude of the correlation between FROC, inferred-ROC and ROC AUC indices. Moreover, if we assume that the within-reader correlation is the same for all of the AUC methods for either of the two modalities, then from Eq. 1 it follows that the ranking of the unattenuated correlations is the same as for the attenuated correlations.

Descriptive statistics

Histograms of ratings for each reader and modality, for normal and abnormal cases, were plotted for FROC, inferred-ROC and conventional-ROC data. To investigate possible causes for the small correlation between inferred-ROC and conventional-ROC data, we compared the reader rating distributions for the two methods. The average percentage (across readers) of abnormal images in the FROC study where a nonlesion received a higher score than a lesion was also calculated for each modality.

RESULTS

Table 1 reports the calculated Pearson correlation values and corresponding 95% confidence intervals for each reader and modality under the three paradigm comparisons (FROC vs inferred-ROC, inferred-ROC vs conventional-ROC, and FROC vs conventional-ROC). Mean values (equal to the average over the four readers and both modalities) are also reported (in bold). For individual readers, the correlation was significantly different from zero for all three comparisons except for reader 4, for whom the inferred ROC-conventional-ROC comparison was not significant for either modality, while FROC-conventional ROC was not significant for modality 2. The ordering of the correlations was the same for each reader-modality combination (and therefore for the average values). Averaged across the four readers and two image-processing algorithms, the Pearson correlations between the AUC estimates (with 95% confidence intervals in brackets) and their ordering were: Corr(FROC, inferred-ROC) = 0.76 [0.64, 0.84] > Corr(inferred-ROC, conventional-ROC) = 0.40 [0.18, 0.58] > Corr(FROC, conventional-ROC) = 0.32 [0.16, 0.46].

Table 1.

Bootstrap calculated Pearson correlation coefficients r describing the association between the area-under-the-AFROC curve (FROC AUC), inferred-ROC AUC, and conventional-ROC AUC estimates. Results are reported for each reader (1–4) and modality (M1 and M2). The average correlation over all readers and modalities is also given (in bold). Ninety-five-percent confidence intervals of the correlation coefficient are reported within parentheses.

| FROC AUC vs | Inferred-ROC AUC vs | FROC AUC vs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modality | Reader | inferred-ROC AUC | conventional-ROC AUC | conventional-ROC AUC |

| M1 | 1 | 0.65 (0.49, 0.77) | 0.61 (0.34, 0.79) | 0.41 (0.23, 0.56) |

| 2 | 0.76 (0.64, 0.84) | 0.39 (0.16, 0.58) | 0.29 (0.12, 0.43) | |

| 3 | 0.78 (0.68, 0.85) | 0.57 (0.39, 0.71) | 0.38 (0.22, 0.51) | |

| 4 | 0.76 (0.62, 0.86) | 0.17 (−0.06, 0.38) | 0.26 (0.08, 0.40) | |

| M2 | 1 | 0.71 (0.58, 0.81) | 0.44 (0.19, 0.63) | 0.36 (0.19, 0.51) |

| 2 | 0.80 (0.71, 0.86) | 0.45 (0.27, 0.60) | 0.38 (0.24, 0.51) | |

| 3 | 0.82 (0.74, 0.88) | 0.40 (0.22, 0.56) | 0.35 (0.20, 0.51) | |

| 4 | 0.77 (0.65, 0.85) | 0.16 (−0.05, 0.36) | 0.12 (−0.04, 0.28) | |

| Average over readers | ||||

| and modalities (bootstrap) | 0.76 (0.64, 0.84) | 0.40 (0.18, 0.58) | 0.32 (0.16, 0.46) | |

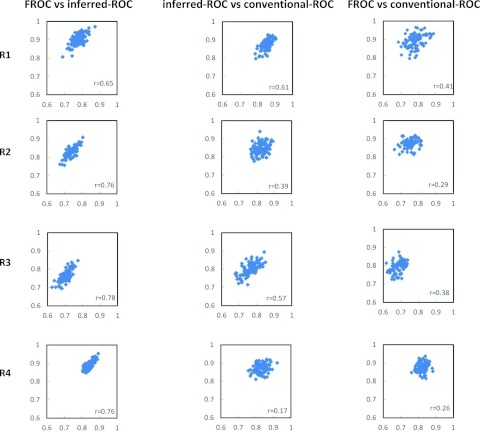

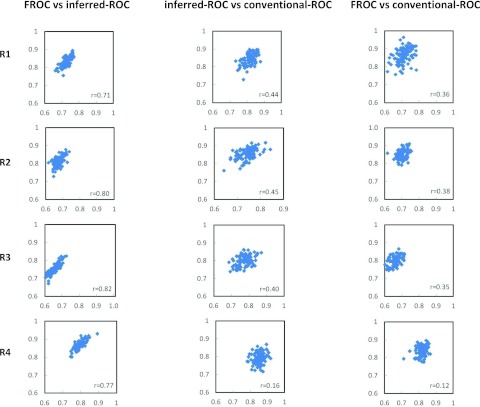

Figure 1 shows the scatter plots for 100 bootstrap data sets of the estimated AUCs for FROC vs inferred-ROC (left), inferred-ROC vs conventional-ROC (center), and of FROC vs conventional-ROC (right), for each reader and for modality 1. Figure 2 shows corresponding scatter plots for modality 2. In both figures the Pearson coefficient r from Table 1, computed from the 500 first-stage bootstraps, is also reported.

Figure 1.

Scatter plots of the area-under-the-curve estimates for AFROC vs inferred-ROC (left), inferred-ROC vs conventional-ROC (center), and AFROC vs conventional-ROC (right), for all four readers and modality 1 (M1). The correlation coefficient r calculated over the 500 bootstrap samples is also reported.

Figure 2.

Scatter plots of the area-under-the-curve estimates for AFROC vs inferred-ROC (left), inferred-ROC vs conventional-ROC (center), and AFROC vs conventional-ROC (right), for all four readers and modality 2 (M2). The correlation coefficient r calculated over the 500 bootstrap samples is also reported.

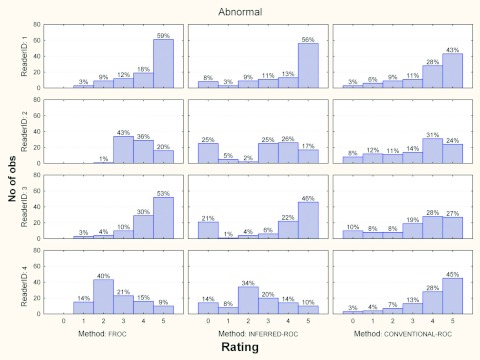

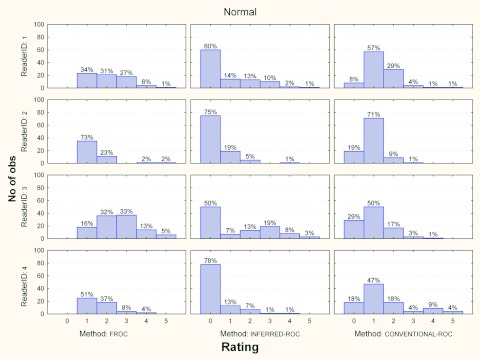

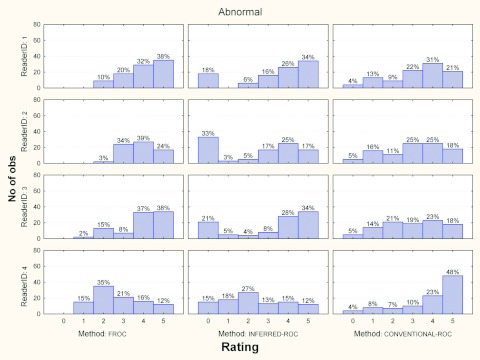

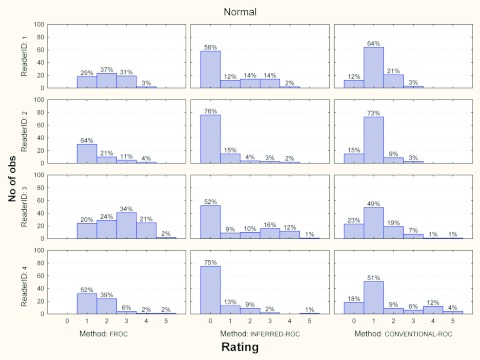

Figures 3456 show the histograms of ratings for each reader and for the three investigated paradigms, for normal and abnormal cases and for each modality, separately. Averaged across readers, the percentage of abnormal images in the FROC study where a nonlesion received a higher score than a lesion was 5% (range 2%–7%) and 10% (range 2%–13%) for modalities 1 and 2, respectively.

Figure 3.

Histograms of ratings for each reader and paradigms, for abnormal cases and modality 1. The percent of cases per rating is also reported.

Figure 4.

Histograms of ratings for each reader and paradigms, for normal cases and modality 1. The percent of cases per rating is also reported.

Figure 5.

Histograms of ratings for each reader and paradigms, for abnormal cases and modality 2. The percent of cases per rating is also reported.

Figure 6.

Histograms of ratings for each reader and paradigms, for normal cases and modality 2. The percent of cases per rating is also reported.

The estimated OR correlations, r1, r2, and r3, are presented in Table 2(a) for each AUC method. In order to compare these with the between-paradigm correlations reported in Table 1, the averages of the OR correlations from Table 2(a) for each pair of paradigms are reported in Table 2(b). Comparing Table 2(b) correlation averages with the summary correlations in the last row of Table 1, we make the following observations: (1) the FROC vs inferred ROC average correlation (0.76) is much higher than the corresponding r1 average (0.41); (2) the inferred-ROC vs conventional ROC correlation average (0.40) is midway between the corresponding r1 (0.45) and r2 (0.36) correlation averages; and (3) the FROC vs ROC correlation average (0.32) is equal to the corresponding r3 average (0.32).

Table 2.

Estimated Obuchowski-Rockette correlations with modality (M1 and M2 levels) being the test factor. r1 = correlation between AUCS for different modalities and the same reader; r2 = correlation between AUCs for different readers using the same modality; r3 = correlation between AUCs for different readers using different modalities. Correlations were estimated using jackknifing. (a) Single method Obuchowski-Rockette correlations and (b) pairwise averages of the Obuchowski-Rockette correlations.

| (a) Paradigm | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation | FROC | Inferred-ROC | ROC |

| r1 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.50 |

| r2 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.44 |

| r3 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.38 |

| (b) Pair average | |||

| Correlation | FROC and | Inferred-ROC | FROC |

| inferred ROC | and ROC | and ROC | |

| r1 | 0.41 | 0.45 | 0.46 |

| r2 | 0.31 | 0.36 | 0.39 |

| r3 | 0.27 | 0.32 | 0.32 |

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to report on independently conducted FROC and ROC data acquisitions for the purpose of studying fixed-reader correlations between three reader-performance estimates: the area under the alternative free-response receiver operating characteristic (AFROC) curve (FROC AUC), the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve computed from FROC highest rating data (inferred-ROC AUC), and the area under the ROC curve computed from independently acquired confidence-of-disease ratings (conventional-ROC AUC).

The bootstrap analysis, conducted to estimate the correlation between the area-under-the-curve estimators and corresponding confidence intervals, showed the strongest correlations between FROC and inferred-ROC (average r = 0.76), lower correlations between inferred-ROC and conventional-ROC (average r = 0.40), and the lowest correlations between FROC and conventional-ROC (average r = 0.32).

The relatively high coefficient correlation (r varied from 0.65 to 0.82, for all readers under both modalities) between the FROC and inferred-ROC AUCs [left column of Figs. 12] is easily explained by the deterministic relationship between FROC and inferred-ROC data and by the fact that we expect it to be less attenuated that the other correlations, as previously discussed. A perfect correlation between FROC and inferred-ROC AUC would occur if only one lesion per abnormal image was present and the lesion received the highest score for that image; for this situation the two measures would yield identical scores. In our study, across all readers and both modalities, 31% of the abnormal images had multiple lesions and for 7.5% of abnormal images a nonlesion received a higher score than a lesion, which to some degree explains why the FROC vs inferred-ROC correlation is not closer to one.

Of particular interest are the moderate-to-low (0.16 ⩽ r ⩽ 0.61) correlations between the inferred-ROC and conventional-ROC AUCs. The average of these correlations (0.40) was less than the r1 average (0.45) but more than the r2 average (0.36); i.e., the inferred ROC vs ROC correlation was somewhat less than the correlation of AUCS between different modalities for one reader using only one of the AUC methods. We also computed correlations comparing the AUC methods using jackknifing and obtain approximately the same correlation estimates (within 0.03) as from bootstrapping, and hence similar conclusions.

These results are of interest because several papers21, 22, 23 have made conclusions about the relative performance of FROC and conventional-ROC based upon comparisons between FROC and inferred-ROC. This correlation comparison suggests that the highest rate assumption may not be appropriate for predicting AUC for conventional-ROC data.

To investigate why the inferred-ROC vs ROC correlation was not higher, we compared the rating distributions for both modalities, presented in Figs. 35. From these figures we see that for abnormal cases, readers show a similar trend (the number of marks increases for higher ratings) for the conventional-ROC data, with readers having comparable levels of aggressiveness. For inferred-ROC data instead the trends are mixed: reader 1 takes advantage of the possibility of localizing the lesions by being more aggressive in scoring relative to his conventional-ROC ratings; in contrast, reader 4 is less aggressive when localization is involved, with a rating of 2 having the highest frequency for both modalities.

For normal cases (Figs. 46), again interreader variability seems very low for conventional-ROC data, with a rating of 1 assigned most often for each reader-and-modality combination. In contrast, for inferred-ROC reader behavior is mixed, though less than for the abnormal cases, with all readers assigning a 0 rating most often (this means that they became more certain regarding the healthy status of the examination as the images associated with rate of 0 are the ones left unmarked in the FROC study). These differences in rating distributions between ROC and FROC possibly contribute to lower the correlation between inferred-ROC and conventional-ROC AUCs.

Correlation was even lower when comparing FROC and conventional-ROC AUCs. These correlations varied between 0.12 and 0.41 for all readers and both modalities, with an average correlation r = 0.32 which was the same as the corresponding r3 average; i.e., the FROC vs ROC correlation was similar to the correlation between different modalities for different readers, both using the same AUC method. A comparison of ROC and FROC histograms shows trends similar to those for the ROC vs inferred-ROC comparison. Again, this could be one reason for the low correlation between these last two indices.

As previously noted, the correlations between conventional-ROC and the other methods are attenuated due to intrareader variability (synonymous with within-reader variability or simply reader inconsistency). This within-reader variability is due to the fact that the same case presented twice to an observer will not bring about the same response from the observer. For example, the reader may score a microcalcification cluster differently in repeated readings or may miss it while he/she had detected in the first study. This intrareader variability will cause the AUC correlation to decrease. This decrease would, therefore, not be due to differences in the data collection or analysis method, like discussed earlier; rather it would be related to perceptual variation in the observer's latent rating variable for the same case.

A literature search conducted to report on investigation that aimed at quantifying intrareader variation in ROC analysis methods in mammography did not reveal any studies that provided the necessary information (either the fixed-reader within-reader correlation or the proportion of the OR error variance attributable to within-reader variability) to account for the within-reader variability in the correlation estimates of FROC vs inferred-ROC. For example, Metz et al.52 investigated inter- and intrareader variation in the interpretation of medical images in order to predict gains in accuracy from replicated readings, but their results pertain to the underlying decision variable rather than to the AUC estimates.

Interesting to note is that in a previous study by Gur et al.,53 where they investigated agreement of AUCs under FROC and ROC paradigms, an average correlation for all readers of about 0.7 (0.27–0.8; 95% confidence interval, CI) was found. This value is much higher than what we found in our study (0.32; 0.16–0.46; 95% CI). The explanation for these differences is that they computed the Pearson correlation across nine pairs of AUC values, each pair corresponding to a different reader. That is, they measured correlation treating readers as random sampling units, whereas we estimated correlation for each reader, treating readers as fixed. The difference is that in their approach, the correlation is between deviations from a population mean across readers, whereas in our approach the correlation is between deviations from the true or latent reader value for each reader. Because their correlation is dependent on the range of the reader AUC values, choosing readers with a wide range of expertise levels will result in a stronger correlation; in our method instead the calculated correlations are independent of between-reader variability, as readers are treated as fixed. Although two of the three AUC-method fixed-reader correlations do depend on within-reader variability, which we cannot estimate for this study, comparing these correlations to the OR correlations is meaningful because the OR correlations depend on within-reader variability in a similar way.

Several investigations have reported results of FROC and inferred-ROC analyses, and in all instances both methods yielded the same modality ordering.21, 22, 45, 54, 55, 56 However, an experiment to explore this question rigorously, by comparing FROC and conventional-ROC, would require collecting independent FROC and ROC datasets for a moderate number of modalities; unfortunately, such an experiment would be prohibitively expensive to conduct.

The study has some limitations: (1) A limitation is that only two modalities and four readers are included and the correlation analyses treated modality and reader as fixed factors; thus conclusions strictly apply only to the two modalities and four readers used in this study. The correlations obtained measure the association between the summary measures across the population of cases, but not across readers or modalities. Conducting similar experiments using other modalities and readers would be useful for determining if our findings can be generalized to relevant populations of readers and modalities. (2) The abnormal images were simulated, and although the simulations had been validated against real lesions48 and there are many precedents for simulation studies using physical and mathematical phantoms to asses image quality in radiology,38, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62 a clinical study would be even more convincing. However that would require many more resources, mainly due to the difficulty of obtaining subtle abnormal cases: in mammography only three to five women per 1000 have breast cancer. (3) The images were read under laboratory conditions where the observers knew there would be no clinical consequence for incorrect decisions.63 This was not a real time study: conducting dual-paradigm dual-modality studies under clinical conditions is impossible since each real-time patient images are read in the clinical paradigm which is not under the experimenter's control.

CONCLUSIONS

To our knowledge, this is the first report on independently acquired FROC and ROC datasets to assess the fixed-reader association between FROC, inferred-ROC and conventional-ROC area-under-the-curve estimates. For the specific image processing algorithms investigated, bootstrap analysis demonstrated a strong correlation only between FROC and inferred-ROC. Importantly, correlation between inferred- and conventional-ROC was at best moderate and was similar (but somewhat less) than the correlation of AUCS between different modalities for one reader using only one of the AUC methods; these results suggest that the highest rating assumption may not be appropriate when one wants to compare net FROC and conventional ROC performance, using inferred-ROC data. Although correlations were attenuated due to within-reader variability, this attenuation does not affect comparisons of the FROC vs ROC and inferred-ROC vs ROC correlations with the Obuchowski-Rockette correlations because they are similarly attenuated. An important study limitation is that conclusions strictly apply only to the two modalities and four readers used in the study; thus it is important to conduct further similar studies to determine if these findings generalize to relevant populations of readers and modalities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

F.Z. was supported in part by the Mevic project. Mevic is an IBBT-project in cooperation with the following companies and organizations: Barco, Hologic, Philips, University Hospital Leuven, University of Gent MEDISIP/IPI, Free University of Brussels, and ETRO. The IBBT is an independent multidisciplinary research institute founded by the Flemish government to stimulate ICT innovation. F.Z. wants to thank Jurgen Jacobs for the support with the use of the SARA2v software. F.Z. would like to thank Professor Dev Chakraborty for his help and advice with the statistical analysis and the editing of the paper. S.L.H. was supported by the National Institutes of Health, R01-EB000863 and R01-EB013667. H.J.Y. was supported in part by grants from the Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, Grant Nos. R01-EB005243 and R01-EB008688.

APPENDIX: DERIVATION OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN ATTENUATED AND UNATTENUATED CORRELATIONS

Result: Suppose that the AUC outcomes follow the model proposed by Obuchowski and Rockette11 with constant within-reader correlation for the three AUC methods for each of the two modalities.

Except for the FROC vs inferred-ROC correlation, the relationship between corresponding attenuated and unattenuated correlations is given by ρ′ = ρ/ρWR, where ρ is the population attenuated correlation, ρ′ is the corresponding unattenuated correlation, and ρWR is the within-reader correlation. We define the unattenuated correlation ρ′ as the correlation that would result if there was no within-reader variability. Here, ρ can be any of the correlations discussed in Secs. II B and II C, except for the FROC vs inferred-ROC correlation; i.e., it can be the FROC vs ROC or inferred-ROC vs ROC correlation for one modality, or it can be any of the three OR correlations.

Under the assumption of positive correlation between the within-reader component of the FROC and inferred-ROC AUC measurement error, attenuation for the FROC vs inferred-ROC correlation will be proportionately less than that for the other correlations. That is, ρ′ < ρ/ρWR.

Proof:

(1) A natural model for the AUC estimate for method i, reader j, and replication k, denoted by , is that proposed by Obuchowski and Rockette.11 Treating readers as fixed, this model specifies that

where θijk is the latent fixed-reader AUC, and ɛijk is the fixed-reader measurement error term. Define . To account for correlation attributable to reading the same cases, they assume that the ɛijk are correlated and have the following four possible covariances:

We assume εijk = uij + wijk, where uij is the case-sample deviation and wijk is the within-reader deviation. We assume that the uij are identically distributed with variance . We assume that the wijk are independent and normally distributed with zero means and variance , and that they are independent of the uij. We allow the uij to be correlated. It follows that and the uij have the same covariance structure as the corresponding ɛijk; i.e.,

In summary, the variance of the measurement error term ɛijk is attributable to case variability and to within-reader variability that describes how a reader interprets the same image in different ways on different occasions. If a reader reads the same case sample twice, then uij remains the same (since the cases are the same) but the wijk deviations are each an independent realization from the within-reader error distribution. For now we assume that Cov1, Cov2, and Cov3 do not depend on the AUC method or modality.

Let denote the fixed-reader population correlation for AUC methods i and i′ (thus i ≠ i′) for a given reader. Then

Note in the preceding equation that because wijk and are independent of each other and of the uij.

The corresponding unattenuated correlation is defined the same as but with the within-reader variability set to zero, i.e., with . That is,

Noting that the within-reader correlation is given by

it follows that

Thus far the i subscript has been the indicator of AUC method for a given modality. We can obtain the above result for the OR correlations simply by redefining the i subscript to be the indicator of modality for a given AUC method. Also, we have assumed that Cov1, Cov2, and Cov3 do not depend on the AUC method; however, it is easy to show that this assumption is not necessary for the above result, as long as we still assume that the within-reader correlation for the three AUC methods is constant for each of the two modalities.

(2) Assume there is positive correlation between the within-reader component of the measurement error between FROC and inferred-ROC for a given reader. Letting the i subscript again denote AUC method, with i = 1 denoting FROC and i = 2 denoting inferred-ROC, this assumption implies cov(w1jk, w2jk) > 0. This assumption is reasonable because inferred-ROC AUC is a deterministic function of the FROC data (the reader does not read the images again), and hence the within-reader deviations for the two methods should be positively correlated. Under this assumption, we no longer have , as was the case for the preceding result. Rather, we have cov(u1j + w1j1, u2j + w2j1) = cov(u1j, u2j) + cov(w1j1, w2j1) = Cov1 + cov(w1j1, w2j1) > Cov1. Thus

and

i.e., .

References

- Kundel H., Berbaum K., Dorfman D., Gur D., Swensson R., and Metz C., “Receiver operating characteristic analysis in medical imaging,” J. ICRU 8(1), Report 79 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Samei E. and Krupinski E. A., The Handbook of Medical Image Perception and Techniques (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, New York, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- McClish D. K., “Analyzing a portion of the ROC curve,” Med. Decis Making 9, 190–195 (1989). 10.1177/0272989X8900900307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Metz C. E., and Nishikawa R. M., “A receiver operating characteristic partial area index for highly sensitive diagnostic tests,” Radiology 201, 745–750 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beiden S. V., Wagner R. F., and Campbell G., “Components-of-variance models and multiple-bootstrap experiments: An alternative method for random-effects, receiver operating characteristic analysis,” Acad. Radiol. 7, 341–349 (2000). 10.1016/S1076-6332(00)80008-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beiden S. V., Wagner R. F., Campbell G., and Chan H. P., “Analysis of uncertainties in estimates of components of variance in multivariate ROC analysis,” Acad. Radiol. 8, 616–622 (2001). 10.1016/S1076-6332(03)80686-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beiden S. V., Wagner R. F., Campbell G., Metz C. E., and Jiang Y., “Components-of-variance models for random-effects ROC analysis: The case of unequal variance structures across modalities,” Acad. Radiol. 8, 605–615 (2001). 10.1016/S1076-6332(03)80685-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorfman D. D., Berbaum K. S., Metz C. E., Lenth R. V., Hanley J. A., and Abu D. H., “Proper receiver operating characteristic analysis: The bigamma model,” Acad. Radiol. 4, 138–149 (1997). 10.1016/S1076-6332(97)80013-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorfman D. D., Berbaum K. S., Lenth R. V., Chen Y. F., and Donaghy B. A., “Monte Carlo validation of a multireader method for receiver operating characteristic discrete rating data: Factorial experimental design,” Acad. Radiol. 5, 591–602 (1998). 10.1016/S1076-6332(98)80294-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishwaran H. and Gatsonis A. C., “A general class of hierarchical ordinal regression models with applications to correlated ROC analysis,” Can. J. Stat. 28(4), 731–750 (2000). 10.2307/3315913 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Obuchowski N. A. and H. E.RocketteJr., “Hypothesis testing of the diagnostic accuracy for multiple diagnostic tests: An ANOVA approach with dependent observations,” Commun. Stat.-Simul. Comput. 24, 285–308 (1995). 10.1080/03610919508813243 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Obuchowski N. A., “Multireader, multimodality receiver operating characteristic curve studies: Hypothesis testing and sample size estimation using an analysis of variance approach with dependent observations,” Acad. Radiol. 2(Suppl. 1), S22–S29 (1995). 10.1016/S1076-6332(05)80441-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorfman D. D., Berbaum K. S., and Metz C. E., “Receiver operating characteristic rating analysis: Generalization to the population of readers and patients with the jackknife method,” Invest. Radiol. 27, 723–731 (1992). 10.1097/00004424-199209000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berbaum K. S., Schartz K. M., and Hillis S. L. (2012). OR/DBM MRMC (Version 2.4) [Computer software]. Iowa City, IA: The University of Iowa. Available from http://perception.radiology.uiowa.edu.

- Hillis S. L., Obuchowski N. A., Schartz K. M., and Berbaum K. S., “A comparison of the Dorfman-Berbaum-Metz and Obuchowski-Rockette methods for receiver operating characteristic (ROC) data,” Stat. Med. 24, 1579–1607 (2005). 10.1002/sim.2024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis S. L., “A comparison of denominator degrees of freedom methods for multiple observer ROC analysis,” Stat. Med. 26, 596–619 (2007). 10.1002/sim.2532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis S. L., Berbaum K. S., and Metz C. E., “Recent developments in the Dorfman-Berbaum-Metz procedure for multireader ROC study analysis,” Acad. Radiol. 15, 647–661 (2008). 10.1016/j.acra.2007.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunch P. C., Hamilton J. F., Sanderson G. K., and Simmons A. H., “A free-response approach to the measurement and characterization of radiographic-observer performance,” J. Appl. Photogr. Eng. 4, 166–171 (1978). 10.1117/12.955926 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty D. P. and Berbaum K. S., “Observer studies involving detection and localization: Modeling, analysis, and validation,” Med. Phys. 31, 2313–2330 (2004). 10.1118/1.1769352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swensson R. G., “Unified measurement of observer performance in detecting and localizing target objects on images,” Med. Phys. 23, 1709–1725 (1996). 10.1118/1.597758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paquerault S., Smelson F. W., Petrick N., and Myers K. J., “Comparing signal-based and case-based methodologies for CAD assessment in a detection task,” Proc. SPIE 6917, pp. 691708–691708-9 (2008). 10.1117/12.771498 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paquerault S., Samuelson F. W., Myers K. J., and Smith R. C., “Non-localization and localization ROC analyses using clinically based scoring,” Proc. SPIE 7263, 72630U (2009). 10.1117/12.813761 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson F. W. and Petrick N., “Comparing image detection algorithms using resampling,” in Proceedings of the International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging: From Nano to Micro, Arlington, VA (IEEE, 2006), pp. 1312–1315.

- Chakraborty D. P., jafroc software v3f, 2010. (available URL: www.devchakraborty.com).

- Chakraborty D. P., “ROC curves predicted by a model of visual search,” Phys. Med. Biol. 51, 3463–3482 (2006). 10.1088/0031-9155/51/14/013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty D. P., “A search model and figure of merit for observer data acquired according to the free-response paradigm,” Phys. Med. Biol. 51, 3449–3462 (2006). 10.1088/0031-9155/51/14/012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty D. P. and Yoon H. J., “Operating characteristics predicted by models for diagnostic tasks involving lesion localization,” Med. Phys. 35, 435–445 (2008). 10.1118/1.2820902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan P. C. et al. , “The impact of acoustic noise found within clinical departments on radiology performance,” Acad. Radiol. 15, 472–476 (2008). 10.1016/j.acra.2007.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruegel M. et al. , “Diagnosis of hepatic metastasis: Comparison of respiration-triggered diffusion-weighted echo-planar MRI and five T2-weighted turbo spin-echo sequences,” Am. J. Roentgenol. 191, 1421–1429 (2008). 10.2214/AJR.07.3279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisichella V. A. et al. , “Computer-aided detection (CAD) as a second reader using perspective filet view at CT colonography: Effect on performance of inexperienced readers,” Clin. Radiol. 64, 972–982 (2009). 10.1016/j.crad.2009.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge J. et al. , “Computer-aided detection system for clustered microcalcifications: Comparison of performance on full-field digital mammograms and digitized screen-film mammograms,” Phys. Med. Biol. 52, 981–1000 (2007). 10.1088/0031-9155/52/4/008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goo J. M. et al. , “Is the computer-aided detection scheme for lung nodule also useful in detecting lung cancer?,” J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 32, 570–575 (2008). 10.1097/RCT.0b013e318146261c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good W. F. et al. , “Digital breast tomosynthesis: A pilot observer study,” Am. J. Roentgenol. 190, 865–869 (2008). 10.2214/AJR.07.2841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose T., Nitta N., Shiraishi J., Nagatani Y., Takahashi M., and Murata K., “Evaluation of computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) software for the detection of lung nodules on multidetector row computed tomography (MDCT): JAFROC study for the improvement in radiologists’ diagnostic accuracy,” Acad. Radiol. 15, 1505–1512 (2008). 10.1016/j.acra.2008.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nappi J. and Yoshida H., “Virtual tagging for laxative-free CT colonography: Pilot evaluation,” Med. Phys. 36, 1830–1838 (2009). 10.1118/1.3113893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penedo M. et al. , “Free-response receiver operating characteristic evaluation of lossy JPEG2000 and object-based set partitioning in hierarchical trees compression of digitized mammograms,” Radiology 237, 450–457 (2005). 10.1148/radiol.2372040996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pikus L. et al. , “Artificial multiple sclerosis lesions on simulated FLAIR brain MR images: Echo time and observer performance in detection,” Radiology 239, 238–245 (2006). 10.1148/radiol.2383050211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruschin M. et al. , “Dose dependence of mass and microcalcification detection in digital mammography: Free response human observer studies,” Med. Phys. 34, 400–407 (2007). 10.1118/1.2405324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiraishi J., Appelbaum D., Pu Y., Li Q., Pesce L., and Doi K., “Usefulness of temporal subtraction images for identification of interval changes in successive whole-body bone scans: JAFROC analysis of radiologists’ performance,” Acad. Radiol. 14, 959–966 (2007). 10.1016/j.acra.2007.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vikgren J. et al. , “Comparison of chest tomosynthesis and chest radiography for detection of pulmonary nodules: Human observer study of clinical cases,” Radiology 249, 1034–1041 (2008). 10.1148/radiol.2492080304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J. et al. , “Dual system approach to computer-aided detection of breast masses on mammograms,” Med. Phys. 33, 4157–4168 (2006). 10.1118/1.2357838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo J. H., Henry L. P., Krejza J., and Melhem E. R., “Detection of simulated multiple sclerosis lesions on T2-weighted and FLAIR images of the brain: Observer performance,” Radiology 241, 206–212 (2006). 10.1148/radiol.2411050792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagawa M. et al. , “Commercially available computer-aided detection system for pulmonary nodules on thin-section images using 64 detectors-row CT: Preliminary study of 48 cases,” Acad. Radiol. 16, 924–933 (2009). 10.1016/j.acra.2009.01.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachrisson S. et al. , “Effect of clinical experience of chest tomosynthesis on detection of pulmonary nodules,” Acta Radiol. 50, 884–891 (2009). 10.1080/02841850903085584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng B., Chakraborty D. P., Rockette H. E., Maitz G. S., and Gur D., “A comparison of two data analyses from two observer performance studies using Jackknife ROC and JAFROC,” Med. Phys. 32, 1031–1034 (2005). 10.1118/1.1884766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanca F. et al. , “Evaluation of clinical image processing algorithms used in digital in digital mammography,” Med. Phys. 36, 765–775 (2009). 10.1118/1.3077121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess A. and Chakraborty S., “Producing lesions for hybrid mammograms: Extracted tumors and simulated microcalcifications,” Proc. SPIE 3663, 316–322 (1999). 10.1117/12.349659 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zanca F. et al. , “An improved method for simulating microcalcifications in digital mammograms,” Med. Phys. 35, 4012–4018 (2008). 10.1118/1.2968334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs J., Zanca F., Marchal G., and Bosmans H., “Implementation of a novel software framework for increased efficiency in observer performance studies in digital radiology” in Proceedings of the Scientific Assembly and Annual Meeting of the RSNA, Chicago, IL, 2008.

- Efron B., “Jackknife-after-bootstrap standard errors and influence functions,” J. R. Statist. Soc. B 54, 83–127 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Hartly H. and Pearson E., Biometrika Tables for Statisticians, 3rd ed. (Cambridge University Press, New York, 1996), Vol. I. [Google Scholar]

- Metz C. E. and Shen J. H., “Gains in accuracy from replicated readings of diagnostic images: Prediction and assessment in terms of ROC analysis,” Med. Decis Making 12, 60–75 (1992). 10.1177/0272989X9201200110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur D. et al. , “Agreement of the order of overall performance levels under different reading paradigms,” Acad. Radiol. 15, 1567–1573 (2008). 10.1016/j.acra.2008.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppini G., Diciotti S., Falchini M., Villari N., and Valli G., “Neural networks for computer-aided diagnosis: Detection of lung nodules in chest radiograms,” IEEE Trans. Inf. Technol. Biomed. 7, 344–357 (2003). 10.1109/TITB.2003.821313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver A. et al. , “A review of automatic mass detection and segmentation in mammographic images,” Med. Image Anal. 14, 87–110 (2010). 10.1016/j.media.2009.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volokh L., Liu C., and Tsui B. M. W., “Exploring FROC paradigm: Initial experience with clinical applications,” Proc. SPIE 6146, 94–105 (2006). 10.1117/12.653247 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla A. S., Samei E., Saunders R. S., Lo J. Y., and Baker J. A., “A mathematical model platform for optimizing a multiprojection breast imaging system,” Med. Phys. 35, 1337–1345 (2008). 10.1118/1.2885367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranger N. T., Lo J. Y., and Samei E., “A technique optimization protocol and the potential for dose reduction in digital mammography,” Med. Phys. 37, 962–969 (2010). 10.1118/1.3276732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard S. and Samei E., “Quantitative imaging in breast tomosynthesis and CT: Comparison of detection and estimation task performance,” Med. Phys. 37, 2627–2637 (2010). 10.1118/1.3429025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samei E., R. S.SaundersJr., Baker J. A., and DeLong D. M., “Digital mammography: Effects of reduced radiation dose on diagnostic performance,” Radiology 243, 396–404 (2007). 10.1148/radiol.2432061065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders R., Samei E., Baker J., and Delong D., “Simulation of mammographic lesions,” Acad. Radiol. 13, 860–870 (2006). 10.1016/j.acra.2006.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer C. M., Samei E., and Lo J. Y., “The quantitative potential for breast tomosynthesis imaging,” Med. Phys. 37, 1004–1016 (2010). 10.1118/1.3285038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur D. et al. , “The “laboratory” effect: Comparing radiologists’ performance and variability during prospective clinical and laboratory mammography interpretations,” Radiology 249, 47–53 (2008). 10.1148/radiol.2491072025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]